Abstract

Using agency and stewardship theories, this article investigates conditions that affect the impact of performance management in the ministerial steering of agencies. Agency theory assumes that agencies act opportunistically, leading to low trust between the ministry and the agency. Conversely, stewardship theory assumes that agencies act trustworthily. Arguably, however, in the steering of agencies, the impact of performance management depends on performance management practices and the type of ministry–agency relation. The effect of performance contract design and a top-down or bottom-up approach to performance management on the impact of performance management is analyzed in the context of whether the ministry–agency relation tends toward the principal–agent or principal–steward type. The data were obtained from a survey of bureaucrats employed in government agencies in Norway and a systematic analysis of official policy documents. The results show that a bottom-up approach increases the impact of performance management in principal–steward relations but not in principal–agent relations. Performance contract design has no effect on the impact of performance management, irrespective of relationship characteristics.

Introduction

Performance management is a widespread practice in public sector reform and is well integrated with the steering of public organizations. Scholarly research has especially focused on how and why public organizations use performance management and performance information (e.g., Kroll, Citation2015; Moynihan & Pandey, Citation2006), whether performance management leads to better performance (e.g., Gerrish, Citation2016), or problematic effects of performance management (e.g., Birdsall, Citation2018; Moynihan, Citation2009). However, in the steering of public organizations, there is scarce knowledge about what conditions the impact of performance management. The impact of using performance management in the steering of agencies is, in this study, understood as bureaucrats’ perceptions of the relevance of performance management on their work. Understanding such conditions is important, as high-impact performance management might lead to more efficient control, which might improve organizational performance. Moreover, low-impact performance management might engender bureaucratic drift. This article aims to improve our understanding of how the impact of using performance management in the steering of agencies is affected by different performance management practices and ministry–agency relations.

Specifically, this article asks: In the steering of agencies, what conditions the impact of performance management? The article discusses agency and stewardship theories and investigates how different practices of performance management affect its impact and how the effects of different practices depend on mutual trust in the ministry–agency relation.

Agency theory postulates that executives (e.g., a government agency) may act opportunistically, which might undermine the preferences of political principals (e.g., a ministry). In such cases, political principals could use performance management to monitor and control the executive. Strict control is expected to increase the impact of performance management when holding opportunistic executives accountable. However, several authors have noted that trust and collaboration between political principals and executives might serve as alternative accountability mechanisms (Pierre & Peters, Citation2017; Van Slyke, Citation2006; Van Thiel & Yesilkagit, Citation2011). Agency theory often fails to describe the role of trust and cooperation, which scholars have argued is understood in stewardship theory (Davis et al., Citation1997; Schillemans, Citation2013; Schillemans & Bjurstrøm, Citation2019; Van Slyke, Citation2006). Stewardship theory suggests that in the presence of goal congruence, the trust might evolve and more relaxed, rather than strict, control might increase the impact of performance management.

This article examines the ministerial steering of government agencies in Norway. Data were obtained from a survey of bureaucrats employed in agencies, document studies of performance contracts between ministries and agencies, and register data. The combination of data from different sources provides a unique data set comprising about 700 bureaucrats from 30 government agencies. The results show that in the steering of agencies, bureaucrats perceive that performance management has a substantial impact. Furthermore, a bottom-up approach to performance management has a stronger effect on the impact of performance management in cases characterized by a high level of mutual trust in the ministry–agency relation. In cases of low trust, no such effect occurs. Interestingly, performance contract specification has no effect on the impact of performance management, regardless of the trust level.

This article first presents contrasting approaches from agency and stewardship theories as to how ministries can exercise performance management. Second, it describes the data and methods. Third, it presents the results, followed by a discussion in section four, and then a conclusion.

Controlling government agencies

Ministries delegating tasks to agencies face accountability problems and have to impose control structures, such as performance management, to ensure that agencies comply with their wishes. However, the impact of performance management might depend on the context in which it is exercised. In the ministerial steering of agencies, its impact arguably depends on the ministry–agency relation. To understand how relationship characteristics might alter the effects of performance management practices on the impact of performance management, this study uses agency and stewardship theories.

Research on accountability in the public sector has been heavily influenced by agency theory (Schillemans & Busuioc, Citation2015), a framework designed to study potential problems arising from principals delegating tasks to executives, that is, agents (Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Waterman & Meier, Citation1998). The theory assumes that actors are opportunistic utility maximizers. It has two main concerns: (1) that the interests of principals and agents diverge, and (2) how the principal might control what the agent is doing (Eisenhardt, Citation1989, p. 58). While the principal has formal authority, the agent usually possesses an information advantage regarding the costs of performing the delegated task (Maggetti & Papadopoulos, Citation2018, pp. 172–173). Agency theory assumes that agents might exploit this information asymmetry to shirk or drift from their obligations. When principals delegate decision-making to agents, shirking might cause implemented policies to deviate from the principals’ intentions, resulting in accountability-related problems (Maggetti & Papadopoulos, Citation2018; Schillemans & Busuioc, Citation2015). Agency theory argues that by regulating hierarchical relationships and delegating through ex-ante and ex-post control, principals might avoid (or at least limit) problems related to accountability and drift (Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Schillemans & Busuioc, Citation2015; Vosselman, Citation2016).

Despite the hegemony of agency theory, it has been criticized for its inability to fully explain bureaucratic behavior (Pierre & Peters, Citation2017; Schillemans & Busuioc, Citation2015). Scholars have argued that mutual trust between principals and executives might serve as an alternative or complementary form of control (Amirkhanyan et al., Citation2010; Brown et al., Citation2007; Lamothe & Lamothe, Citation2012; Majone, Citation2001; Van Slyke, Citation2006; Van Thiel & Yesilkagit, Citation2011). Davis et al. (Citation1997) argue that the assumption about executives acting as agents in many cases is questionable. Instead, they advance stewardship theory as an alternative to agency theory in studies of delegation. Stewardship theory assumes goal congruence and that relations between principals and executives are based on trust rather than strong hierarchical control.

Schillemans (Citation2013) proposes stewardship theory, as an alternative theoretical framework to agency theory, in studies of accountability in ministry–agency relations. Contrary to agency theory, stewardship theory assumes that executives are “…motivated to act in the best interest of their principals” (Davis et al., Citation1997, p. 24). Executives act as stewards, put pro-organizational goals above their self-interest, and are largely intrinsically motivated (Davis et al., Citation1997; Schillemans, Citation2013; Van Slyke, Citation2006). When principals delegate tasks to stewards who put organizational goals above self-interest, problems related to bureaucratic drift remain minimal.

Agency theory assumes that agencies act as opportunistic agents, whereby the principal–agent relation has low goal congruence and runs the risk of becoming a low-trust relationship. Conversely, stewardship theory assumes that agencies act as trustworthy stewards, whereby the principal–steward relation has high goal congruence and is likely to be a high-trust relation. These contrasting views on agency behavior imply that control can be exercised in different ways. Davis et al. (Citation1997) argue that the impact of control depends on whether an executive is acting as an agent or steward. When principals exercise control, they should take their relationship with the executive into account to ensure that control is highly impactful. If the relationship resembles more of the principal–agent type, principals should impose strict control over the executive to ensure a high impact. Conversely, if the relationship resembles more of the principal–steward type, they should impose more relaxed control, again to ensure a high impact. The principal’s decision regarding how to exercise control over the executive might be described as a dilemma (Davis et al., Citation1997). If principals impose control mechanisms that fit the characteristics of the relationship, the impact of control will be high. In contrast, if principals impose control mechanisms that do not fit the characteristics of the relationship, the control will be suboptimal or insufficient and will have a low impact. Further, it is important to note that principal–agent and principal–steward relations are not dichotomous. They are ideal types of relationships on different ends of a continuum ranging from relationships with a low degree of goal congruence and mutual trust (the principal–agent relation) to relationships with a high degree of goal congruence and mutual trust (the principal–steward relation).

It could be assumed, rightly or wrongly, that the ministry–agency relation could tend toward either the principal–agent or principal–steward type. If ministries assume that their relationship with an agency tends toward the principal–agent type, tight control should be imposed to limit information asymmetry and agency autonomy. Agencies are expected to shirk and drift from their responsibilities, with the relationship characterized by low mutual trust. If the relationship resembles the principal–agent type, there will be a match between the control practices and type of relation, with ministerial control yielding a high impact. However, if the relationship resembles the principal–steward type, there will be a mismatch between control practices and relationship characteristics, with the resulting low impact of ministerial control. Agencies might feel “betrayed,” and their stewardship motivation might be “crowded out,” leading to gaming and other types of unwanted adaptations to control mechanisms (Davis et al., Citation1997, pp. 39–40).

In contrast, ministries might assume that the ministry–agency relation tends toward the principal–steward type, characterized by goal congruence and mutual trust. If so, ministries will be expected to apply more relaxed control, granting agencies greater autonomy. Trust and collaboration are the operating mechanisms for achieving accountability. If the relationship resembles the principal–steward type, there is a mutual fit between control practices and relationship characteristics, and the impact of control is expected to be high. Conversely, if the ministry–agency relation resembles the principal–agent type, the situation is similar to a “fox in the henhouse” (Davis et al., Citation1997, p. 40). Because of insufficient control, the impact of ministerial control might be low, and government agencies might act opportunistically and game the system.

In essence, the difference between principal–agent and principal–steward relationships lies is the degree of goal congruence. The former is characterized by low goal congruence and proneness to low trust, while the latter is characterized by high goal congruence and a propensity toward high trust. When ministries exercise control to hold government agencies accountable, the impact of control depends on the level of trust between the two entities. The principal must consider the relationship with the executive and not design control practices that are decoupled from the characteristics of that relationship.

Two types of control: Contractual control and process control

Contracts

Performance contracts constitute an essential part of practicing performance management. These are quasi-contractual arrangements used to address asymmetric information; they serve as instruments for setting goals, targets, and rewards linked to performance (Greve, Citation2000). The use of performance contracts in the steering of agencies is a way for ministries to exercise control.

The contracting literature distinguishes between complete and relational contracts (Amirkhanyan, Citation2011; Amirkhanyan et al., Citation2010; Brown et al., Citation2007). When ministries specify performance contracts, these contracts might be highly specified or less specified (Brown et al., Citation2007, p. 610). Contract specifications might, therefore, be regarded as a continuum of contract completeness, moving from soft or relational contracting with few steering demands to hard or complete contracting in which all (or as many as possible) contingencies are covered and highly specified (Amirkhanyan, Citation2011; Greve, Citation2000; Majone, Citation2001).

The principal–agent framework has featured prominently in the discussion on hard contracting (Greve, Citation2000, p. 155). Hard contracting implies strong ministerial control, which, in principal–agent relations, arguably has an influential impact. By specifying all demands in advance, more complete contracts might reduce an agency’s information advantage, goal ambiguity, and opportunistic behavior (Baker & Krawiec, Citation2006; Chun & Rainey, Citation2005; Verhoest, Citation2005). With clear objectives and targets set by the ministry, agencies can be held accountable for their performance and compliance with the ministry’s preferences. A performance contract is an effective tool for control but only if it leaves no room for shirking or drift. Agency theory assumes that in a principal–agent relation, performance management has a greater impact if ministries rely on complete contracting.

H1. If the ministry–agency relation tends toward the principal–agent type, performance management in the steering of agencies will have a stronger impact if ministries rely on complete contracting.

However, if ministries assume that the ministry–agency relation tends toward the principal–steward type, they might rely on relational contracting, subjecting agencies to less strict control. A principal–steward relationship is characterized by goal congruence and trust. Pierre and Peters (Citation2017) refer to trust as “the relative absence of performance control or measurement” (p. 163). Trust might act as a mode of control and accountability and serves as an alternative to a performance-based control system (Van Dooren et al., Citation2015, p. 213). As the trust between ministries and agencies increases, ministries are expected to “slim down” performance contracts toward the relational type. Rather than specifying all the terms in advance, relational contracts are more open. They are incomplete in the sense that they “do not determine all terms of the agreement in advance of the execution” (Amirkhanyan et al., Citation2010, p. 192). Ministries and agencies might not agree on “detailed plans of action, but on general principles” (Majone, Citation2001, p. 116).

Based on stewardship theory, detailed performance control might have a lesser impact and might even be counterproductive. In a principal–steward relation, agencies might distance themselves from organizational goals if they are subjected to strong, detailed control (Davis et al., Citation1997), reducing the impact of performance management. Stewards need substantial responsibility and autonomy (Van Slyke, Citation2006, p. 167). In the steering of agencies, performance management might have a stronger impact when agencies are subjected to relational contracting (compared to complete contracting), given the principal–steward relation.

H2. If the ministry–agency relation tends toward the principal–steward type, performance management in the steering of agencies will have a stronger impact if ministries rely on relational contracting.

Process

Performance management is more than just performance contracting. It is also a process where goals and targets are defined, tasks are monitored, and performance information is evaluated (Van Dooren et al., Citation2015, pp. 62–85). Monitoring and involvement are a type of control that ministries might practice differently. Ministries might view the performance management process as either top-down or bottom-up, which resembles different types of control.

Given a relationship tending toward the principal–agent type, ministries are expected to take a top-down approach to performance management, which implies strong ministerial control. The ministry alone develops goals and performance targets, and performance management is more about control than learning and autonomy. Sufficient oversight is needed to avoid shirking. Agency discretion is a control problem that should be limited (Thomann et al., Citation2018).

H3. If the ministry–agency relation tends toward the principal–agent type, performance management in the steering of agencies will have a greater impact if it is exercised top-down.

Alternatively, in relationships tending more toward the principal–stewardship type, ministries might take a bottom-up approach rather than a top-down strategy. A bottom-up approach suggests looser ministerial control, where agencies are allowed greater autonomy. Goals and performance targets are largely jointly developed, and performance information is used for learning rather than control. The ministry–agency relation is more of the trust- or collaboration-oriented type, where agencies are more involved in the performance management process. Stewardship theory suggests that low institutional power distances are maintained through a personal style of power rather than through hierarchy (Davis et al., Citation1997). Low power distances, a personal style of management, collaboration, and dialogue between the principal and executive “will prevent stewards distancing themselves from their principals and foster bonds of loyalty and respect that decrease the need for control and oversight” (Schillemans, Citation2013, p. 545). Agencies’ involvement in the performance management process might lead to a deeper commitment to the performance management system (Bouckaert, Citation1993, pp. 37-38). Thus, in principal–steward relations, performance management is expected to have a stronger impact if ministries take a bottom-up approach.

H4. If the ministry–agency relation tends toward the principal–steward type, performance management in the steering of agencies will have a greater impact if it is exercised bottom-up.

Data and methods

Dependent variable: Impact of performance management

To measure the impact of performance management, this study relies on bureaucrats’ perceptions of the impact of performance management on their work. According to the Thomas theorem, people make decisions based on their perceptions of reality, regardless of whether their perceptions are right or wrong (Thomas, Citation1928). One can reasonably assume that bureaucrats act on their perceptions of the impact of performance management rather than based on some objective measure. As agencies consist of individual bureaucrats, the overall impact of performance management is likely to depend on the bureaucrats’ perceptions of the control structures, that is, the performance management system. If agency bureaucrats perceive that performance management has a greater or smaller impact on their work, performance management in the steering of agencies will have a greater or smaller impact.

Data on bureaucrats’ perceptions of performance management were gathered from a large-scale survey of the state administration (Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Citation2016). It comprised two parts: responses from (1) ministry-employed bureaucrats and (2) agency-employed bureaucrats. Only the data on the agency-employed bureaucrats were used in this study. Bureaucrats at the lowest hierarchical level or who had been employed for less than a year were excluded from the sample. Bureaucrats’ perceptions of the impact of performance management were operationalized using three questions from the survey. The respondents were asked to answer the following questions [author’s English translation] on a five-point scale (1 = not important, 5 = very important): “Numerous reforms and measures have been proposed as part of the government’s pursuit of administrative modernization and renewal. How important are the following reforms/initiatives for your field of work? 1) Specification of goals. 2) Letter of appropriation. 3) Evaluation, measuring results.”

Explanatory variable: Performance contract design

The state’s financial regulations stipulate that ministries must define their goals and performance targets for subordinate agencies (Ministry of Finance, Citation2019). Goals and performance targets must be communicated to agencies through a letter of appropriation (tildelingsbrev) as part of the annual budgetary process. This letter can be regarded as a performance contract between ministries and agencies and can contain activity demands that government agencies must fulfill.

The degree of contract completeness was operationalized as the number of steering demands in the performance contracts. To map the number of performance demands, the total number of goals and performance targets were coded, including direct instructions, such as “what-to-do” demands, from the ministries. To ensure validity and reliability, two researchers coded the letters of appropriation. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or consulting a third researcher. The data were initially established by Askim (Citation2015) and Askim et al. (Citation2018, Citation2019).

The database contains data from policy documents from 70 government agencies with different levels of ministry affiliation in 2015. Of these 70 agencies, 30 were covered in the survey of the state administration. All the agencies in the sample are central government agencies directly subordinated to a ministry. They can be classed under Type 1 agencies according to Van Thiel (Citation2012) classification. As the survey was conducted in 2016, this study used data from policy documents from 2015. Thus, the independent variable was lagged by one year.

Explanatory variable: Top-down versus bottom-up approach to performance management

The survey respondents were asked five questions on a five-point scale (see Supplementary Appendix A.1) on their perceptions regarding how the performance management system was expressed in the letters of appropriation and the steering dialogue between the ministries and agencies. A factor analysis was performed to identify dimensions that might capture a top-down or bottom-up approach to performance management. The factor analysis indicated that three of the items could be combined into an index (although with a low Cronbach’s alpha of 0.65). The questions constituting the index measured: (1) the degree to which goals and performance targets are formulated in cooperation between ministries and government agencies; (2) the degree to which performance management allows flexibility and autonomy to government agencies; and (3) the extent to which performance management promotes learning and improvement. The index consisted of the mean scores on the three items, ranging from 1 (top-down approach) to 5 (bottom-up approach).

One item (whether performance management is primarily a tool for ministerial control) did not have a sufficient factor loading on the index and was excluded. However, the question largely addressed a top-down versus a bottom-up approach, but robustness tests showed that the item’s inclusion or exclusion did not affect the results.

Mediating variable: Type of relationship between ministries and government agencies

It is difficult to accurately measure the extent to which a ministry–agency relation tends toward the principal–agent or principal–steward type. In essence, the differences between the two relationship types relate to what degree the executives are acting opportunistically or as loyal servants. Thus, it is a matter of whether agencies can be trusted. Ministries are less likely to trust agencies acting opportunistically. The level of trust may be viewed as a proxy for the relationship type between ministries and agencies. Low mutual trust is more likely in relations resembling the principal–agent type, and high mutual trust is more likely in relationships resembling the principal–steward type.

In the survey, the bureaucrats were asked to rank, on a five-point scale, their perceived level of trust between their agency and its parent ministry. Low perceptions of mutual trust imply ministry–agency relations close to the principal–agent type, while high perceptions of mutual trust imply ministry–agency relations close to the principal–steward type. Ideally, the survey should also have included the ministries’ perceptions of trust between ministries and specific agencies. However, these data are not available, a clear limitation.

Perceived levels of mutual trust in ministry–agency relations do not only reflect the level of trust; it might also reflect how the respondents feel or believe that the ministry treats them. This is an important aspect of mutual trust, as bureaucrats who perceive that their agency is trusted are more likely to believe that the level of mutual trust is high and vice versa.

Control variables

Control variables were added at both the agency and respondent levels to avoid spurious effects. Agency size might be viewed as a proxy for several organizational characteristics, for example, complexity, number of tasks, and budget size. Earlier research indicates that agency size might affect formal control, accountability mechanisms (Askim, Citation2015; Laegreid et al., Citation2006; Pollitt, Citation2006), and performance contracts (Askim et al., Citation2019). Agency size was measured as the number of full-time equivalents (FTEs) one year before the contract term (see Supplementary Appendices A.2 and A.3 for descriptive statistics). Data were obtained from state administration databases provided by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (Citation2016).

At the individual respondent level, two control variables were added. From a structural instrumental perspective on organizations, formal structures are expected to affect organizational outcomes and characteristics (Egeberg, Citation2012). Therefore, the first control variable was the respondent’s hierarchical position (see the frequencies in Supplementary Appendix A.4). Organizations might be regarded as rational systems, where the top management in government agencies transfers the ministries’ preferences downward in the organization. Thus, bureaucrats with higher positions in the hierarchy are expected to find that performance management has a higher impact compared with bureaucrats at lower levels. Four hierarchical levels were identified in the survey and used in this study.

The second respondent-level control variable comprised the characteristics of the tasks handled by the respondent. Different tasks might variously affect bureaucrats’ perceptions of the impact of performance management. For example, bureaucrats handling more mission-related tasks (tasks related to an agency’s core mission), such as single-case decision-making and supervision, might be more affected by performance demands compared with bureaucrats handling less mission-related tasks (such as coordination and in-house tasks). The respondents were asked to categorize the majority of their work into one of ten types of tasks, which were classified into four categories: mission-related tasks (e.g., single-case decision-making, supervision, control, and auditing), coordination and budgeting, reporting on results, and other/in-house tasks (such as human resource management). The frequencies are reported in Supplementary Appendix A.5.

Data structure

Regressions were estimated with multilevel modeling, accounting for the hierarchical structure in the data (bureaucrats nested in agencies). Multilevel modeling is suitable for these kinds of data, as the effects of the variables at each level were estimated separately (Hox, Citation2010). The effects of the agency and individual-respondent levels are estimated from the number of agencies (n = 30) and respondents (n ∼ 700), respectively.

The use of perceptual measures from survey data raises common source bias concerns, as the dependent and independent variables are collected from the same survey (Jakobsen & Jensen, Citation2015; Podsakoff & Organ, Citation1986). Common source bias involves situations in which the estimated effect of one variable on another is biased due to “systematic variance shared among the variables” (Jakobsen & Jensen, Citation2015, p. 3).

The dependent variable is self-reported, but the explanatory variable, contract design, is not; common source bias is, therefore, absent. Two of the individual-level variables, tasks, and position in the hierarchy, are self-reported and collected from the same survey as the dependent variable. The questions measuring tasks and positions in the hierarchy are forthright and did not demand the respondent’s evaluation. The probability of biased effects from these variables on the respondents’ perception of the impact of performance management is, therefore, low. However, the effect of the perceived ministry–agency relation type (mutual trust) and the perception of performance management processes (top-down vs. bottom-up) on the perceived impact of performance management should be interpreted with caution, as these effects might be influenced by common source bias.

Results

Descriptive statistics

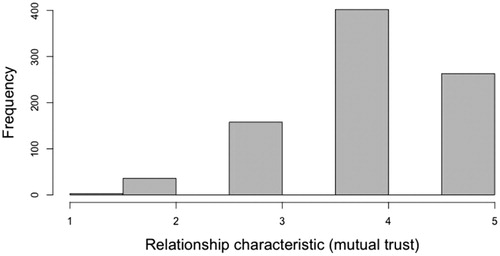

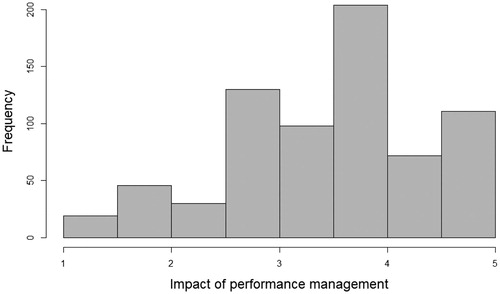

presents a histogram of the bureaucrats’ perceptions of the impact of performance management. The histogram indicates that, in the steering of agencies, performance management has a substantial impact. On a scale of 1 to 5, the average is 3.6 and the median 3.7 (1 = low impact, 5 = high impact). The intraclass correlation in the impact of performance management is three percent; thus, the agency employing the bureaucrat accounts for three percent of the variation in the bureaucrat’s perceptions of the impact of performance management.

Figure 1. Histogram of bureaucrats’ perceptions of the impact of performance management (1 = low, 5 = high).

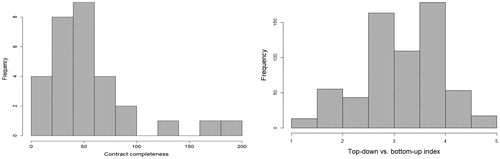

shows the degree of contract completeness and whether performance management is practiced top-down (1) or bottom-up (5). The average number of steering demands is 58 (median = 50), but with many variations. The histogram on the left shows that steering intensity in the performance contracts is highly skewed toward the left. The one on the right illustrates that bureaucrats perceive performance management as slightly more bottom-up than top-down. On a five-point scale, the average is 3.2, and the median is 3.

Figure 2. Histogram of contract completeness, measured as the number of steering demands in the performance contracts (left), and histogram of bureaucrats’ perceptions of performance management approach (1 = top-down, 5 = bottom-up) (right).

shows the bureaucrats’ perceptions of ministry–agency relations. The bureaucrats perceive mutual trust as quite high, with both the average and median scoring 4 on a scale of 1 (low mutual trust) to 5 (high mutual trust). The histogram indicates that the bureaucrats generally perceive that the ministry–agency relations tend more toward a principal–steward relation than a principal–agent relation.

Regressions

displays the regression results. Because of the skewed distribution of contract completeness and agency size, both variables are log-transformed. There is reason to believe that the relationships between contract completeness and government agency size and between contract completeness and the impact of performance management are nonlinear. The log transformation should account for this nonlinearity. Holding all other covariates constant, the coefficients from the log-transformed variables should be interpreted as one unit of change on the log scale of the predictor returns bk change in the dependent variable (impact of performance management). Thus, a 1% change in the predictor implies a bk × log(1.01) increase in the dependent variable.

Table 1. Multilevel regression analysis results.

Model 1 () shows the bivariate relationship between performance contract completeness and the impact of performance management. The effect is close to zero, that is, not significant, so the model does not support the expectation that, in the steering of agencies, the contract design would affect the impact of performance management. Model 2 shows the effect of a top-down versus a bottom-up approach to performance management. It shows that to increase the impact of performance management, a bottom-up approach is preferable to a top-down approach

Models 3 and 4 show the effects of performance contract design and a top-down versus a bottom-up approach to performance management on the impact of performance management, conditional on whether the ministry–agency relation tends toward the principal–agent or principal–steward type. The ministry–agency relation type does not significantly influence the effect of contract design (which is still insignificant). However, the effect of a top-down or bottom-up approach to performance management on the impact of performance management is heavily influenced by whether the bureaucrats perceive the ministry–agency relation to be more of a principal–agent or principal–steward type. A bottom-up approach decreases the impact of performance management when bureaucrats perceive the relationship as a principal–agent type. The impact increases when bureaucrats perceive the relationship as a principal–steward type.

Model 5 shows the effects of the control variables. The regression shows that higher-ranking bureaucrats find that, in the steering of agencies, performance management is significantly more impactful than did lower-ranking bureaucrats. The model also includes the type of ministry–agency relation (the level of mutual trust). Increased mutual trust seems to enforce the impact of performance management. This might seem counterintuitive, but as Model 4 shows, the effect of how ministries exercise their control is heavily influenced by relationship type.

Models 6 and 7 are complete. They estimate effects at both the agency and individual-respondent levels. Model 6 confirms that in the steering of agencies, contract design has no effect on the impact of performance management, regardless of whether the contract is relational or complete or whether the ministry–agency relation tends toward the principal–agent or principal–steward type.

The significant differences among bureaucrats at different hierarchical levels in Model 5 are not present in Models 6 and 7. It seems that the differences in the perceptions of the impact of performance management between the highest- and lowest-level bureaucrats results from differences in perceptions about whether the ministry takes a top-down or bottom-up approach to performance management.

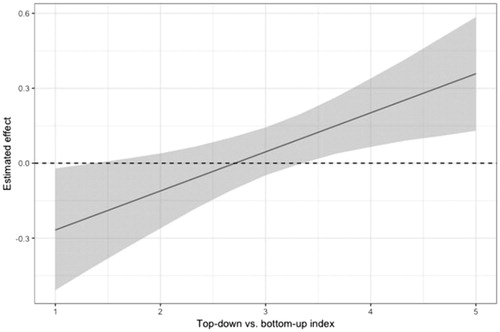

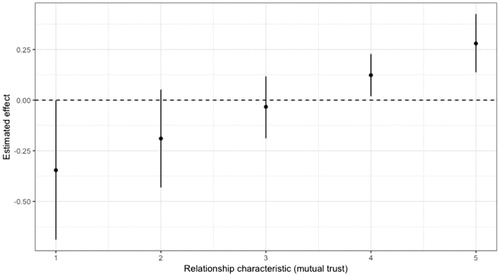

To ease the interpretation of the interaction between relationship characteristics and a top-down or bottom-up approach to performance management in Model 7, shows the effect of an increased bottom-up approach for different levels of mutual trust, which implies moving from a principal–agent relation toward a principal–steward relation. The figure shows that a bottom-up approach to performance management in the steering of agencies increases the impact of performance management only if bureaucrats perceive a high level of trust between ministries and agencies (indicating a principal–steward relation). Instances in which mutual trust is perceived as low, indicating a ministry–agency relation of the principal–agent type, the result seems contradictory. In low-trust relations, a top-down approach leads to higher performance management impact than a bottom-up approach. However, there is too much uncertainty, likely caused by the fact that only a few respondents perceived the level of trust as minimal for the effect to be significant.

Figure 4. The effect of an increased bottom-up approach, conditional on the level of mutual trust in the ministry–agency relation (95% confidence intervals).

shows the effect of increased mutual trust, a more principal–steward-oriented relationship conditional on whether performance management is practiced as top-down or bottom-up. The effect of mutual trust is significantly positive for bottom-up performance management and significantly negative for top-down performance management. Increased mutual trust, in combination with bottom-up involvement, increases performance management impact; however, in combination with top-down control, it decreases performance management impact. If ministries practice top-down control in ministry–agency relations resembling the principal–steward type, reductions in performance management impact follow. However, if ministries take a bottom-up approach to performance management in the steering, the result is increased performance management impact.

Discussion

This study shows that overall performance management in the steering of agencies has a substantial impact. However, the analysis indicates that whether ministries rely on relational or complete contracting is inconsequential for bureaucrats’ perceptions of the impact of performance management. The effect of contract design on the impact of performance management is also unaffected by whether the ministry–agency relation tends toward the principal–agent or principal–steward type. Thus hypotheses 1 and 2 regarding performance contract design are not confirmed.

The results support Davis et al. (Citation1997) in describing the principal’s choice of control as a dilemma. When ministries decide on a top-down or bottom-up approach to performance management, the results show that they should consider whether the ministry–agency relation balancing toward a principal–agent or principal–steward type. Compared to a bottom-up approach, a top-down approach leads to greater performance management impact only in principal–agent-like ministry–agency relations. If bureaucrats perceive an absence of mutual trust, a bottom-up approach might be counterproductive. This fits recommendations from agency theory, that is, in a principal–agent relationship, principals must impose a sufficient amount of control to prevent shirking and drift (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). A bottom-up approach in a principal–agent relation might resemble a “fox in the henhouse” (Davis et al., Citation1997, p. 39), where the exercise of control is decoupled from the type of relationship. Hypotheses 3 and 4 regarding the performance management process are corroborated.

Conversely, for high-trust ministry–agency relations increased top-down control reduces the impact of performance management. Bureaucrats who perceive high levels of mutual trust between their agency and ministry, indicating a ministry–agency relation balancing toward the principal–steward type, also perceive top-down control as leading to performance management being less impactful. This supports the claim that stewardship motivation might be crowded out if principals impose strict control in principal–steward relations. As such, increased bottom-up performance management in the steering of agencies increases the impact of performance management impact only when bureaucrats perceive a high-trust ministry–agency relation, implying a principal–steward relation. There is a mutual fit between principals’ choice of control and the relationship characteristics. In principal–steward relations, stewardship theory recommends a low power distance between principal and stewards, which prevents stewards from distancing themselves from the principal (Schillemans, Citation2013, p. 545). Two important aspects of a low power distance are involvement and collaboration, with goal alignment and mutual trust as outcomes (Van Slyke, Citation2006). A low power distance fits a bottom-up approach, where ministries and agencies might jointly develop and use performance information.

This study shows that when the bureaucrats perceive their ministry–agency relation as resembling the principal–steward type (with high mutual trust), they also perceive that a bottom-up approach increases the relevance of performance management in their work, more so than bureaucrats perceiving that they are in a principal–agency relation. These findings imply that ministries should take a bottom-up approach when steering a government agency where bureaucrats generally perceive high mutual trust. This will ensure a mutual fit between control structures and the type of relationship between the ministry and the agency and will increase the impact of performance management. A higher performance management impact might lead to more effective control, which might improve organizational performance.

A limitation of this study is the use of cross-sectional data as longitudinal data were not available. Future research should focus on obtaining longitudinal data to allow for stronger claims about inferences between control practices and ministry–agency relations and the impact of performance management.

The data show that in the steering of agencies, performance contract design does not affect the impact of performance management, regardless of the ministry–agency relationship characteristics. Why does contractual design not matter? First, a possible explanation could be the research method. The dependent variable in this study is based on closed questions (commonly used in surveys). Closed questions might be more reliable than open questions, but they face concerns related to validity; for example, it is difficult to know whether respondents report on the impact of performance management for their specific daily tasks or their field of tasks in general. Nevertheless, as this study investigated the impact of using performance management in the steering of agencies more in general and not on individual bureaucrats, the distinction is not overly problematic. Both interpretations of the question provide valuable information on the impact of using performance management in the steering of agencies. If the respondents believe that performance management in the steering of agencies has a high impact on their work, then using performance management has a high impact in the steering of the agency where they are employed. Or, if the respondents believe that performance management has a high impact on their field of tasks more broadly, then it has a high impact.

Second, in a bureaucratic hierarchy, tasks are delegated vertically to protect individual bureaucrats from information overload caused by limited resources and bounded rationality. The number of steering demands in a performance contract does not necessarily affect bureaucrats’ perceptions of the impact of performance management because bureaucrats lower down the hierarchy are only exposed to the goals and targets related to their range of work. A large increase in the number of steering demands imposed on an agency does not necessarily imply that bureaucrats in that agency would face an equally large increase in steering demands. However, performance management might have a stronger impact on top management, which sets priorities and allocates organizational resources. Goals, targets, and instructions in performance contracts are primarily aimed at top management, who would have to transfer these objectives downward in the organization. It might be the case that the bureaucrats in the survey do not evaluate the impact of the performance contracts received from the ministry when they evaluate the impact of performance management, instead, evaluate an internal performance management system.

Third, this study only covers performance contracts for 30 agencies, all with the same formal affiliation to ministries. More variation among the sample, for example, adding agencies with a higher degree of formal autonomy, might help reveal the effects of contract design on the impact of performance management. However, these data are not available. Moreover, it might be beneficial to have a higher number of respondents from each agency to allow for greater within-agency variation.

Fourth, research has shown that agencies do not necessarily consider control as something negative. They appear to appreciate the attention (Van Thiel & Yesilkagit, Citation2011). If bureaucrats view the number of steering demands in performance contracts as an expression of the ministry’s interest in the agency, it is easy to understand why the design of performance contracts might not matter for performance management impact.

The intraclass correlation in the bureaucrats’ views on performance management impact was rather low. The government agency level only accounts for three percent of the variation in bureaucrats’ perceptions of the impact of performance management. Estimating models 6 and 7 using OLS regression yielded 4 and 5.5% in the explained variance, respectively. It is surprising that performance contract design—ministries’ approach to performance management, trust, tasks, hierarchical positions, and agency size—could not explain more variance in performance management impact in the ministerial steering of government agencies. This might raise the concern that omitted variables might have yielded an increase in explained variance. The low intraclass correlation indicates that bureaucrats’ perceptions of the impact of performance management only to a relatively low degree are explained by their agency of employment. Of the total variance in bureaucrats’ perceptions of the impact of performance management, 97% is at the individual level. It is unlikely that adding agency-level variables to the model would substantially increase explained variance. However, some variables at the respondent level might further increase the explained variance. Nevertheless, this study does not aim to maximize the explained variance but to test the effects of a ministry’s choice of control structures in interaction with ministry–agency relationship characteristics.

Agency and stewardship theories receive mixed support in the sense that neither can independently explain the findings. Both theories describe what kind of control might have the strongest impact under a single different condition, whether subordinates are opportunistic or loyal, which might lead to low-trust or high-trust relations. Agency theory aids in understanding the use of control in the first type of relation, while stewardship theory aids in understanding the latter. The research on ministry–agency relationships (Schillemans, Citation2013; Schillemans & Bjurstrøm, Citation2019), government contracting with third-sector organizations (Dicke, Citation2002; Lambright, Citation2008; Marvel & Marvel, Citation2008; Van Slyke, Citation2006), and corporate governance (Anderson et al., Citation2007; Roberts et al., Citation2005) indicates that agency and stewardship theories are better combined. Rather than confirming the superiority of one over the other, the findings have been mixed. To fully capture the dynamics in the ministerial steering of agencies, the theories should be used complementarily, as in this study.

A final point is that bureaucrats generally perceive high levels of trust and collaboration between ministries and agencies in Norwegian bureaucracies. This might be explained by the fact that Norway has a long tradition of delegating tasks and responsibilities from ministries to government agencies (see Laegreid et al., Citation2012, for more a thorough description of ministry–agency relations in Norway). High mutual trust was also reflected in the study data. When only a small minority of the respondents perceived low levels of mutual trust, the uncertainty around the effects of different types of performance management practices and contract specifications in low-trust relationships increased. This study provides valuable insights into the impact of performance management in a high trust context. Thus, the results might differ if this study is replicated in low trust contexts.

Conclusions

This article examined what conditions the impact of performance management. In particular, it studied the effects of performance contract design and a top-down or bottom-up approach to performance management on the impact of performance management, conditional on the level of mutual trust in the ministry–agency relation.

How a principal exercises control should take into account the nature of the relationship between the principal and the executive to increase the impact of the imposed control. If control structures are decoupled from the type of relationship, then they will be suboptimal and less impactful in the steering. When ministries delegate power and decision-making autonomy to agencies, they might face agency loss and drift resulting from information asymmetry. Agency theory suggests strict hierarchical control with complete contracts and a top-down approach. Conversely, stewardship theory highlights that mutual trust between ministries and agencies might act as an alternative to formal control. It proposes a ministerial reliance on relational contracting and bottom-up involvement.

In conclusion, what conditions the impact of performance management? Overall, while, performance management in the steering of agencies has a substantial impact, this article shows no effect of performance contract design on the impact of performance management, regardless of the type of ministry-agency relation. Whether a government agency is subjected to performance contracts with a high or low degree of completeness does not affect bureaucrats’ perceptions of the impact of performance management. However, ministries’ reliance on a top-down or bottom-up approach to performance management does affect performance management impact. To improve the impact of performance management, ministries should take the level of mutual trust into account. If the degree of trust is low, they should apply a top-down approach, as suggested by agency theory. If the level of trust is high, they should employ a bottom-up approach, as recommended by stewardship theory. There is no “one size fits all” approach to performance management.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (38.5 KB)Acknowledgments

The author thanks three anonymous reviewers and Jostein Askim, Tobias Bach, Thomas Schillemans, and Sandra van Thiel for their valuable comments on earlier drafts of this article. The author is also grateful to the participants at various research seminars and to the participants of the Study Group on Performance and Accountability in the Public Sector at the EGPA’s Annual Conference in Milan, August 30 to September 1, 2017.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Karl Hagen Bjurstrøm

Karl Hagen Bjurstrøm is a doctoral research fellow in the Department of Political Science, University of Oslo. His research focuses on ministry-agency relations and performance management practices. [email protected]

References

- Amirkhanyan, A. A. (2011). What is the effect of performance measurement on perceived accountability effectiveness in state and local government contracts? Public Performance & Management Review, 35(2), 303–339. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576350204

- Amirkhanyan, A. A., Kim, H. J., & Lambright, K. T. (2010). Do relationships matter? Assessing the association between relationship design and contractor performance. Public Performance & Management Review, 34(2), 189–220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576340203

- Anderson, D. W., Melanson, S. J., & Maly, J. (2007). The evolution of corporate governance: Power redistribution brings boards to life. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15(5), 780–797. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2007.00608.x

- Askim, J. (2015). The role of performance management in the steering of executive agencies: Layered, imbedded, or disjointed? Public Performance & Management Review, 38(3), 365–394. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2015.1006463

- Askim, J., Bjurstrøm, K., & Kjaervik, J. (2018). Styring gjennom tildelingsbrev [Data set]. DataverseNO, V2. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18710/E3W52Q

- Askim, J., Bjurstrøm, K., & Kjaervik, J. (2019). Quasi-contractual ministerial steering of state agencies: Its intensity, modes, and how agency characteristics matter. International Public Management Journal, 22(3), 470–498. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2018.1547339

- Baker, S., & Krawiec, K. D. (2006). Incomplete contracts in a complete contract world. Florida State University Law Review, 33(3), 725–755.

- Birdsall, C. (2018). Performance management in public higher education: Unintended consequences and the implications of organizational diversity. Public Performance & Management Review, 41(4), 669–695. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2018.1481116

- Bouckaert, G. (1993). Measurement and meaningful management. Public Productivity & Management Review, 17(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3381047

- Brown, T. L., Potoski, M., & Van Slyke, D. M. (2007). Trust and contract completeness in the public sector. Local Government Studies, 33(4), 607–623. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930701417650

- Chun, Y. H., & Rainey, H. G. (2005). Goal ambiguity and organizational performance in U.S. federal agencies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 10(1), 529–557. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mui030

- Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. The Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 20–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/259223

- Dicke, L. A. (2002). Ensuring accountability in human services contracting: Can stewardship theory fill the bill? The American Review of Public Administration, 32(4), 455–470. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/027507402237870

- Egeberg, M. (2012). How bureaucratic structure matters: An organizational perspective. In B. G. Peters & J. Pierre (Eds.), The Sage handbook of public administration (pp. 77–87). Sage.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4279003

- Gerrish, E. (2016). The impact of performance management on performance in public organizations: A meta-analysis. Public Administration Review, 76(1), 48–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12433

- Greve, C. (2000). Exploring contracts as reinvented institutions in the Danish public sector. Public Administration, 78(1), 153–164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00197

- Hox, J. J. (2010). Multilevel analysis. Techniques and applications. Routledge.

- Jakobsen, M., & Jensen, R. (2015). Common method bias in public management studies. International Public Management Journal, 18(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2014.997906

- Kroll, A. (2015). Drivers of performance information use: Systematic literature review and directions for future research. Public Performance & Management Review, 38(3), 459–486. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2015.1006469

- Laegreid, P., Roness, P. G., & Rubecksen, K. (2006). Performance management in practice: The Norwegian way. Financial Accountability and Management, 22(3), 251–270. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0267-4424.2006.00402.x

- Laegreid, P., Roness, P. G., & Rubecksen, K. (2012). Norway. In. K. Verhoest, S. van Thiel, G. Bouckaert, & P. Laegreid (Eds.), Government agencies: Practices and lessons from 30 countries. (pp. 234–244). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lambright, K. T. (2008). Agency theory and beyond: Contracted providers’ motivations to properly use service monitoring tools. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 19(2), 207–227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mun009

- Lamothe, M., & Lamothe, S. (2012). To trust or not to trust? What matters in local government–vendor relationships? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(4), 867–892. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mur063

- Maggetti, M., & Papadopoulos, Y. (2018). The principal–agent framework and independent regulatory agencies. Political Studies Review, 16(3), 172–183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929916664359

- Majone, G. (2001). Two logics of delegation: Agency and fiduciary relations in EU governance. European Union Politics, 2(1), 103–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116501002001005

- Marvel, M. K., & Marvel, H. P. (2008). Government-to-government contracting: Stewardship, agency, and substitution. International Public Management Journal, 11(2), 171–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10967490802095870

- Ministry of Finance. (2019). Reglement for økonomistyring i staten. Bestemmelser om økonomistyring i staten [Rules for financial management in the state. Provisions on financial management in the state]. The Norwegian Ministry of Finance. https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/fin/vedlegg/okstyring/reglement_for_okonomistyring_i_staten.pdf

- Moynihan, D. P. (2009). Through a glass, darkly. Public Performance & Management Review, 32(4), 592–603. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576320409

- Moynihan, D. P., & Pandey, S. K. (2006). Creating desirable organizational characteristics. Public Management Review, 8(1), 119–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030500518899

- Norwegian Centre for Research Data. (2016). The Norwegian state administration database [Database]. NSD: Data on the political system. http://www.nsd.uib.no/polsys/en/civilservice/

- Pierre, J., & Peters, B. G. (2017). The shirking bureaucrat: A theory in search of evidence? Policy & Politics, 45(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1332/030557317X14845830916703

- Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408

- Pollitt, C. (2006). Performance management in practice: A comparative study of executive agencies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 16(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mui045

- Roberts, J., McNulty, T., & Stiles, P. (2005). Beyond agency conceptions of the work of the non-executive director: Creating accountability in the boardroom. British Journal of Management, 16(s1), S5–S26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2005.00444.x

- Schillemans, T. (2013). Moving beyond the clash of interests: On stewardship theory and the relationships between central government departments and public agencies. Public Management Review, 15(4), 541–562. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2012.691008

- Schillemans, T., & Bjurstrøm, K. H. (2019). Trust and verification: Balancing agency and stewardship theory in the governance of agencies. International Public Management Journal, 0(0), 1–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2018.1553807

- Schillemans, T., & Busuioc, M. (2015). Predicting public sector accountability: From agency drift to forum drift. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25(1), 191–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muu024

- Thomann, E., van Engen, N., & Tummers, L. (2018). The necessity of discretion: A behavioral evaluation of bottom-up implementation theory. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 28(4), 583–601. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muy024

- Thomas, W. I. (1928). The child in America: Behavior problems and programs. Knopf.

- Van Dooren, W., Bouckaert, G., & Halligan, J. (2015). Performance management in the public sector (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Van Slyke, D. M. (2006). Agents or stewards: Using theory to understand the government–nonprofit social service contracting relationship. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 17(2), 157–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mul012

- Van Thiel, S. (2012). Comparing agencies across countries. In K. Verhoest, S. van Thiel, G. Bouckaert, & P. Laegreid (Eds.), Government agencies: Practices and lessons from 30 countries. (pp. 18–28). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Van Thiel, S., & Yesilkagit, K. (2011). Good neighbours or distant friends? Trust between Dutch ministries and their executive agencies. Public Management Review, 13(6), 783–802. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2010.539111

- Verhoest, K. (2005). Effects of autonomy, performance contracting, and competition on the performance of a public agency: A case study. Policy Studies Journal, 33(2), 235–258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2005.00104.x

- Vosselman, E. (2016). Accounting, accountability, and ethics in public sector organizations: Toward a duality between instrumental accountability and relational response-ability. Administration & Society, 48(5), 602–627. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399713514844

- Waterman, R. W., & Meier, K. J. (1998). Principal–agent models: An expansion? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 8(2), 173–202. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024377