Abstract

This article presents a tool to disclose public values as emergent properties of needs on a systemic basis applied to a city district in Rotterdam. A tool which enables the public manager to identify public values in any territory based on how people think and feel about society. To accomplish this, it uses Group Model Building (GMB) principles to elicit the mental models that individuals use to make sense of their environment. The results show how the tool enhances a manager’s situational awareness and could assists him with information-driven service delivery.

Introduction

Research of public value and public values is a widespread phenomenon in public administration and management scholarship. Some even talk about Public Value Governance as the new paradigm (e.g. Bryson et al., Citation2014; O’Flynn, Citation2007). Although there is a large diversity in perspectives on what public value(s) is (Alford & O'Flynn, Citation2009; Benington & Moore, Citation2011; Fukumoto & Bozeman, Citation2019; Jørgensen & Bozeman, Citation2007; Mulgan, Citation2011) and what the role of the manager or politicians is or should be (Brown & Head, Citation2019; Dahl & Soss, Citation2014; Moore, Citation1995), there seems to be a consensus that citizens should play a role in public value(s) research (Bozeman, Citation2019; Nabatchi, Citation2012; Rutgers, Citation2015). “Public value creation is about impact on how people think and feel about society.” (Meynhardt, Citation2009, pp. 193) However, few studies have put an emphasis on the public in the public value(s) research (conf. Bozeman, Citation2019).

If the idea of citizens being at the core of public value(s) research is accepted, it might be called odd that hardly any research starts with citizens in their territorial context. Of course, it is difficult to get representative value definitions from citizens; owing to (1) citizens taking more extreme positions as participants, (2) participatory mechanisms not facilitating two-way communication, (3) involvement of usual suspects (i.e. participation bias) (Nabatchi, Citation2012). Within modern pluralistic and ever-changing societies, competing perspectives of individuals or groups about what they need complicate obtaining public value(s) to guide policy decisions. We have developed a tool to disclose public values on a systemic basis, making it possible to identify public values in any territory based on how people think and feel about society (conf. Meynhardt, Citation2009; Nabatchi, Citation2012).

The objectives of the current article are to:

develop a Public Values Disclosure tool (PVD-tool).

validate the PVD-tool in practice within the district Schiebroek-Zuid in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

provide empirical data of citizens’ wants and needs; i.e. what constitutes the public values in the aforementioned territory.

discuss the (possible) consequences of disclosed public values for decision-makers and public management.

In order to do so we will discuss the literature concerning public value(s) and complex systems in the next section. Complex systems theory can shed some light on how people ascribe meaning or value, and how the sum of all these evaluations can be related to each other. This will form the foundations for the PVD-tool. In Section “Public values disclosure tool” we present the research approach and how the PVD-tool will be applied to a community living in a city district of Rotterdam. The values that are elicited by interviewing respondents will be analyzed in Section “Results”. In Section “Discussion” we will discuss the added practical and theoretical value of the PVD-tool by comparing it to current municipal practices and existing public value literature.

Public value(s) theory

Public value(s) theory has had a remarkable growth since 2007 (Jørgensen & Rutgers, Citation2015). It has broadened the view on performance by public sector organizations: instead of focusing on predetermined performance targets, it tries to better understand the needs of individuals. This puts it in line with the new public governance paradigm, which “proposes the transition from formal government to a shared, informal and competence-based governance […] and shifts the attention from the obsessive research of internal efficiency to an external focus based on the effectiveness in meeting user-citizen’s needs.” (Fledderus et al., Citation2014; Polese et al., Citation2018, pp. 28) This is crucial given the constantly changing contexts leading to greater diversity of needs, rising expectations, declining deference to hierarchy and authority, and the emergence of the ‘critical consumer/citizen’ (Benington & Moore, Citation2011). Public values are then produced when public sector organizations meet citizen’s needs (Osborne, Citation2018; Spano, Citation2009).

There are three broad traditions (conf. Bryson et al., Citation2014): the first two converge on the “public spirited pursuit of collectively valued goals and these goals should be specified as measurable standards for evaluating performance” (Alford & O'Flynn, Citation2009), whereas the third is more concerned with measuring value impacts at a citizen level. The first tradition is based on Mark Moore’s (Citation1995) ‘Creating public value’, the second on Barry Bozeman’s (Citation2002, Citation2007) ‘Public Values’, and the third on the work of Timo Meynhardt (Citation2009) on psychological sources (Strathoff, Citation2016).

According to Moore public value is seen as “an appraisal of what is created and sustained by government on behalf of the public.” (Nabatchi, Citation2011: 4) The public managers are central in creating and sustaining public value: they make decisions that bind all people together. Public managers should seek partnerships with other actors and stakeholders to ensure good choices in the public interest and legitimate the subsequent implementation (Benington & Moore, Citation2011). To enable managers in this role Moore introduces the strategic triangle which describes three tests or spheres to which public sector strategy should adhere (Moore, Citation2000). The first is that of ‘value’: value implies that the actions of public managers should be aimed at creating something of substantive value. The second is the authorizing environment: the public manager should attract political support and resources that are needed to create value. The third checks if the existing operational capabilities are sufficient to achieve the ambitions (Alford & O'Flynn, Citation2009). The strategic triangle implies the necessity for a management control system where citizens and customers are placed at the center. Managers should help governments discover what can be done with their assets while ensuring responsive services to citizens (Benington & Moore, Citation2011).

According to Bozeman public values are derived from intersubjectively held principles that define a society’s normative consensus, which is based on the rights and benefits of citizens. Public values are both identified and measured in the citizenry, and form benchmarks for government performance (Dahl & Soss, Citation2014). As several value orientations can coexist in society at the same time, Bozeman speaks of public values (plural) in contrast to Moore’s public value (singular) (Bozeman, Citation2002; Nabatchi, Citation2011). In order to produce public values and prevent public values failure it is important to know how to identify and understand public values, and how to reconcile value conflicts (Nabatchi, Citation2012). That is why Bozeman (Citation2002) develops a public value failure model, which facilitates deliberation and diagnoses on value failures. Bozeman’s research effort has mainly been directed toward establishing public values on a higher aggregated level; i.e. core or prime public values. These values represent a preferred end-state and are rooted in the unwritten social covenants of society. In order to identify Public values Bozeman (Citation2019) develops a set of candidate values and lets citizens assess whether these values constitute public values. His effort contributes to scarce knowledge of citizen’s views about public values, but it doesn’t identify the values that citizens hold (Jørgensen & Rutgers, Citation2015).

Meynhardt is interested in the meaning of the terms public and value (Strathoff, Citation2016). Value is the quality of the relationship between an evaluating subject and an evaluated object. The evaluation process is driven by psychological constructs like needs, motivations and attitudes. The satisfaction of needs creates value for the subject. The formation of public value can only be understood through a “psychological inquiry into antecedents and states of subjects (individual, group, nations) […] in the ‘eye of the beholder’.” (Meynhardt, Citation2009, pp. 199) Value evolves in a process over time as subjects evaluate and reevaluate objects. When similar evaluations are shared amongst individuals the value becomes ‘objective’, but arguably they are still bound to subjects making them vulnerable to change (Meynhardt, Citation2015). This means that public value centers on how people think and feel about society (Meynhardt, Citation2009, Citation2015). Public value is created by having a positive impact on the relationship between the subject which can be a group or an individual and the object in the form of a social entity. That is why Meynhardt’s approach is non-normative and emphasizes the actual impact of public and private institutions at an individual level (Strathoff, Citation2016, pp. 28).

All these approaches have their virtues and entertain the idea that citizens play a central role. According to (Nabatchi, Citation2012) the overarching problem is that these approaches have difficulties placing citizens at the center and to understand their needs, and that they are unlikely to help create public value. Moore leaves it to the judgment of public managers without discussing their institutional frame of reference (Rhodes & Wanna, Citation2007). Bozeman concurs with Moore that public managers are driven by creating their view of the common good (Strathoff, Citation2016). Bozeman confronts citizens with a preselected set of ‘core’ values at the backend of his research effort, which is troubling given that government generally defines public space differently than citizens do. Meynhardt (Citation2015) uses more open-ended Public Value Scorecards but still only looks at how people and organizations rate some initiative, service, product, or the like, along five dimensions, which is hardly truly open-ended. In general, conventional Public value approaches are often based on networks and co-creation, where they jointly produce value toward common goals (Fledderus et al., Citation2014; Polese et al., Citation2018). Co-production through networked governance runs the risk of excluding those without access to those networks. Connectedness in itself is a form of power not necessarily open nor nonhierarchical. In fact, governance networks can easily subvert network governance, making them limited as a governance/coordinating device (Davies, Citation2011).

The PVD-tool has features to overcome these shortcomings but is closely connected to Meynhardt’s (Citation2009) rich theoretical underpinnings by looking at the relationship between an evaluating subject and an evaluated object. A process that is driven by psychological constructs, most importantly needs. Everything a citizen values is taken as a truth in itself. Where the satisfaction of those needs leads to the creation of value and where values are shared, they become objective.

Identifying public values: a systemic and group model building perspective

Determining what people value is complicated and current research gives public managers little guidance on how to do so (Spano, Citation2009). Citizen’s actions toward the satisfaction of needs and thus the creation of values are never taken based on full knowledge, because society is extremely complex and it is impossible for an individual to oversee all the consequences of their actions. Individuals use data to actively construct reality; they build mental models of their environment which form the basis for their behavior (Gerrits, Citation2012; Vennix, Citation1996). Those mental models are highly subjective and influenced by many factors such as, culture, upbringing and schooling. This means that actions toward the fulfillment of needs – and the creation of values – are based on meaning. Citizens have their own unique and conflicting value sets. This is complex because something is made publicly valuable when the public as a collective values it (Benington & Moore, Citation2011). Hence it is extremely useful to consider the public as a complex social system with interacting parts or citizens. A product of that system is public value. Complex social systems are difficult to understand because their parts working in unison show properties that they do not possess when studied separately (Checkland, Citation1983), i.e. disclosing what citizens value and adding the results is not enough to determine public values. Complex systems can only be understood by looking at the whole (Churchman, Citation1974).

Reconstructing the whole starts with the realization that information on a complex social system is embedded within the people that experience the interactions firsthand; i.e., its citizens. According to Wagenaar (Citation2007) citizens living in (disadvantaged) neighborhoods can tell detailed stories in which problems and causes associated with unfulfilled needs are integrated into a meaningful whole. Although these detailed accounts do not directly point to the underlying causal relations of the issues in a neighborhood, these relations are certainly implied. In fact, the issues are not seen as separate from each other but as part of the neighborhood as a whole: a coherent social entity with intensively interacting parts. Communicating mental models is essential, because it increases the flow of experiential knowledge through the system enabling the actors in the system to produce, appreciate, and select productive intervention strategies toward the production of public values (Parsons, Citation2002; Wagenaar, Citation2007).

According to Sterman (Citation2000) all outcomes a system produces are a logical consequence of its circumstances. The system or “public” is the coherent social entity within an (urban) area, and the interacting parts are its citizens, agencies and institutions. The (inter)actions are based on the (conflicting) needs and values they hold. The circumstances can produce outcomes that are unintended or unwanted for all concerned, but are logical nonetheless. What the citizens collectively regard as being valuable can be disclosed by using a method derived from Group Model Building (Vennix, Citation1996). Group Model Building (GMB) has been successfully employed for years in different fields to develop understanding on complex topics using the combined insight from multiple stakeholders to build informative qualitative diagrams and quantitative simulations (Walters & Litchfield, Citation2015). The GMB process requires stakeholder involvement which helps to create shared meaning and ownership of the model. It also increases understanding of a situation under review and it builds confidence in decisions made (McCardle-Keurentjes et al., Citation2018, Scott et al., Citation2016). Shared meaning is especially relevant as Rhodes and Wanna (Citation2007) consider public value to be about shared meaning that emerges through dialogue and reconfirmation in society. Creating shared meaning also helps to reconcile value conflicts which Dahl and Soss (Citation2014) consider to be requisites.

The multiple stakeholders we are interested in here are the citizens of a community. Involving an entire community in a model build process is undoable, so the method must be tweaked in order to fit the purpose of disclosing public values, while maintaining the model’s strengths. According to Vennix (Citation1996) there are ways to build preliminary models from interviews and documents. Cause maps representing respondents’ views of the system can be constructed from or during interviews, and as such capture respondents’ mental images or mental model providing an understanding of a given situation in a way written language cannot. Building cause maps during interviews also has the advantage that it forces people to express their worldviews more accurately. Sometimes respondents employ tacit assumptions about a situation, which do not hold when constructing a mental model (Vennix, Citation1996).

The community’s preliminary public values model will mainly be based on interviews of a representative part of the community. This requires a low threshold to participate, i.e. interviews that are conducted at the convenience of respondents, whereas the initiative lies with researchers to engage respondents. By aggregating the individual mental models, patterns in certain causal relations can be identified by the researchers and synthesized into a preliminary model representing the system/community. The actual group model build session primarily serves as validation technique at the backend of this effort, but there is still room for participants to modify the model. This is especially effective when the GMB-model is used as a boundary object. A boundary object is a tangible representation of dependencies across disciplinary, organizational, social or cultural lines that all participants can modify, it can create and sustain collaborative discussion (Black & Andersen, Citation2012).

The final model assists those not involved in the building process, in explaining the system structure and in justifying decisions. Confidence in decisions is important because it affects the process of implementation. In a study conducted by McCardle-Keurentjes et al. (Citation2018) it was found that confidence in decisions can be higher when the model is received by stakeholders or decision-makers compared to when they are involved in constructing the model themselves. Even so the study also found the importance of involving stakeholders in the modeling effort as most insights are gained during the building process. We utilize GMB’ strengths of eliciting mental models with their causal mechanisms and its added value of communicating the results.

Public values disclosure tool

The PVD-tool is based on Meynhardt’s (Citation2009: 199) proposition that “Value expresses subjectivity and is bound to relationships. […] Objectivity refers to shared values, still bound to subjects. “People (implicitly) value the fulfillment of their needs. As such “a value then would be an experience based on evaluation of any object against basic needs.” (Meynhardt, Citation2009, pp. 202) Osborne (Citation2018) also states that value is created by how citizens use a public service offering and how it interacts with their life experiences or how they integrate it with their needs. The PVD-tool captures ascribed values and their underlying needs.

The PVD-tool applies an open interviewing technique and GMB to elicit the different mental models that individuals use to make sense of their environment (conf. Vennix, Citation1996). By attempting an integration of these different and partial visions on reality of the people involved, it is possible to create a shared view of the whole. The mental models of interest here concern the values citizens view as the most urgent and the underlying needs they use to ascribe those values. To disclose the individual public values in-depth interviews with individuals are conducted. The way to safeguard for biased interview data is to be a neutral interviewer; i.e. without an interviewers frame of reference, which “provides a way of assessing the perspectives of the respondent, their individual understanding, values, beliefs, experiences, and perceptions, and allowing those nuanced accounts to become the primary source of knowledge to explore in greater depth and breadth” (Scanlan, Citation2020). As such the LSD-technique of interviewing is applied: i.e. actively Listening and neutrally Summarizing what the respondent has said, probing them by Digging deeper in what the underlying causes, feelings, wishes and ultimately values are (Harrell & Selten, Citation2009). This specific LSD-interview technique will be discussed in Section “Methodology: applying the PVD-tool” in more detail.

A mental model contains the individual’s assumptions about the structure and interactions that produce certain meaning (Thiering, Citation2014). The specific meaning we are looking for is that of value. The mental model can be represented by a Causal Loop Diagram (CLD), which serves as the visual map of the mental model of an individual. The CLD shows what an individual thinks are the relevant parts of the structure and the causal relations between those parts responsible for creating a certain meaning (Doyle & Ford, Citation1999). However, meaning is formed by many interacting and often conflicting factors operating at the same time making it hard to tell which actions produce which results. In these cases a systems approach provides a better sense of the circular and nonlinear relations, also known as feedback-loops, that are at play (Barlas, Citation2007). Feedback-loops occur when an element is connected to itself through relations with one or more other elements (Vaandrager et al., Citation2015). In this case the actions taken by citizens or institutions change the environment for other citizens and institutions in turn can trigger a change in their behaviors. In effect each citizen finds himself in an environment that is produced by his interactions with other stakeholders (Wagenaar, Citation2007).

Although individual accounts contain precious information on the systems structure, individuals can only give partial accounts (Gigerenzer & Selten, Citation2002). The focus when talking about public values should be on the community as a whole. It is a question of lifting the data from individual accounts to the level of the social or community system. As mentioned before, owing to the vast amount of citizens in a community the researchers build a preliminary Causal Loop Diagram of the community based on individual accounts. This model will be discussed, modified and validated during a GMB-session by a sample of citizens from the community. The model is not a goal in itself, but a means to generate a better understanding of the system including its structure and resulting behavior (Vennix, Citation1996). This understanding can in turn lead to the identification of leverage points for sustainable interventions.

All in all, public value emerges through the fulfillment of shared needs. Simply taking inventory of peoples’ ascribed values and their underlying needs would not create much of an understanding into the circumstances that fulfill needs and produce values at a community level. The PVD-tool creates a deeper understanding of the whole by deconstructing individually ascribed values into underlying needs, and the mechanisms that either fulfill them or not. It reconciles those underlying needs into shared needs that form the building blocks for public values.

Methodology: applying the PVD-tool

Several propositions on how to involve citizens for the purpose of disclosing public value made by Nabatchi (Citation2012) are incorporated into the research design of the PVD-tool. The PVD-tool is tested in the Southern Schiebroek district of Rotterdam, the Netherlands, but it could have been any other coherent social entity. This district classifies as a depressed district based on municipal indicators regarding educational level, unemployment rate, housing quality and social cohesion. The district contains 5346 ‘residential objects’ which are mostly made up of addresses

Public selection – i.e. participation open to all residents of a geographic community – is more likely to identify and understand public values than stakeholder selection (Nabatchi, Citation2012, pp. 704). Hence the district was split into 11 smaller areas. We randomly visited residential objects by going door to door and interviewed their occupants till 5% of the residential objects within the smaller areas had delivered a mental model. No preselection of citizens was made except for the district itself. All citizens were eligible for participation: although citizens could exclude themselves by declining an interview. To further control for spread and participation bias (Nabatchi, Citation2012, pp. 705) we interviewed at least one resident from every housing block. Not all residential objects turned out to be addresses: some were storage lockers, others were abandoned for demolition. Also, no permission was granted to interview residents from nursing homes. As such certain areas have a lower amount of interviews. All in all, 220 ‘households’ were interviewed from June until October 2016, which represents 5% of the remaining households in Schiebroek-Zuid. The 5% was judged sufficient for a representative result considering time and budget constraints. Indeed, thematic saturation: the point during a series of interviews where few or no new ideas, themes, or codes appear, was reached long before the 5% mark (Weller et al., Citation2018).

The interviews concerned improvements or annoyances regarding the livability within the district. With every issue citizens named the goal was to uncover why they ascribed a certain value to it, how it could come about or what blocked it from coming about. In case of blockage, it was also discussed what the consequences for the livability were. The focus during the interviews was on assisting people to reflect on their values, and not on changing those values through the LSD-interview format (conf. Nabatchi’s (Citation2012, pp. 701) interest-based proposition). To elicit causal endogenous argumentations, the why question was central during the interviews (Vennix, Citation1996). On the basis of these argumentations the mental model in the form of a CLD was formed. These CLD’s consist of causal relations between neutrally termed variables, but small quotes were included to represent the variables as abstracting quotes into variables can cause a loss of information. This richness of information helps in understanding the underlying causes and consequences of existing values. The interview data is put into an excel file, containing data on the causes and consequences relating to value, but also containing information on gender, postal code of residential object, an age estimate. By processing the most mentioned ascribed values, causes and consequences a model representing the larger complex whole of values within the district could be constructed. This model functioned as preliminary model for the GMB session on January 27th, 2017.

In line with Nabatchi (Citation2012, pp. 704) a small table format was used to facilitate deliberation: the joint GMB session was attended by six citizens and one representative from a welfare organization run by the government (note, interviewees showing willingness to invest more time were asked to participate). Deliberation assists in identifying values as it requires the attendees to listen to each other, that all participants have an opportunity to speak and mutual respect (conf. Nabatchi, Citation2012, pp. 702). The session was hosted by two facilitators (Nabatchi, Citation2012, pp. 704) that created the circumstances in which the deliberative communication could thrive. The risk of the group not feeling committed, was reduced by loosely discussing the district without presenting the model at first and to invite participants to discuss anything they saw as relevant. When the preliminary model was presented the themes of the earlier discussion were recognizable and it further helped to speed up the model-building process, reduced time investment and made initiating group discussions easier. It is useful to provide informational materials in participatory processes as it helps participants to identify value (Nabatchi, Citation2012, pp. 704). The session was used to triangulate, validate, update or correct the findings, as iteration and recurrence are important tools in disclosing values (Nabatchi, Citation2012, pp. 705).

Results

Interviews

The reactions to the request of an interview ranged from negative often due to past frustrating experiences with the municipal authority to very positive and grateful that someone was prepared to listen to their grievances. Some interviews were over quickly, especially when people thought the district was doing fine or if they lacked the interest to discuss the problems. If the respondent drew a blank at the mention of for instance livability, it could help to offer some clarification in the form of examples like: housing, safety, overall cleanliness, unemployment and services. However, most interviews reached a point of rapport enabling the extraction of a systemic mental model. Respondents were able to gather their thoughts on the matter by letting them say whatever came to mind without interrupting; i.e. actively listening. By summarizing the initial monologue some points are readdressed and expanded upon; i.e. digging deeper into the causal linkages.

Examples of data

Many respondents mentioned a wide variety of issues and the interviewing technique was crucial in helping respondents to substantiate their claims by formulating what according to them were the causal causes and effects. This simultaneously helps the respondents to reflect on their neighborhood and their opinions: are their assumptions correct? In general respondents managed to describe their neighborhood in one go, as if most were aware of what was happening and didn’t need any reflection on what was obvious to them. Still there were several interviews that managed to uncover contradictions and changes of heart after some due deliberation. E.g. two quotes from the same interview: “It is fine to live here.” “The quality of the house is awful, it is poorly insulated leading to a high gas bill, the kitchen is poorly equipped, the house is damp, and the resulting fungus creates health problems for our children. Next to that people living here are ill-mannered.” The first impression is completely different from the second. This is established by giving people time to think and asking for examples and reasons. Another example is that of a Syrian family that had just fled the violence in their country, that initially stated that: It is OK to live here. However, after further questioning another picture emerged. “The children are being teased and beaten at school. At first we tried to address the behavior through their parents, but now we have become the subject of bullying by the neighborhood. It doesn’t help we do not speak the language.” Asking people to substantiate their claims is crucial to understand meaning, as the following example illustrates: “Those new people coming in are a nuisance: they get everything and native Dutch people can wait up to five years for a home […] those people don’t actually bother me.” The respondent refers to a problem that actually isn’t a problem for him. Substantiating their claims clarifies the meaning respondents give to certain situations, as in many instances opinions may seem similar but they can actually have diverse meanings.

For instance, according to the municipal authority social participation means participation on the job market or in school. According to most respondents, it means something different. Firstly, an important reason for problems with societal participation is a high concentration of a ‘certain kind of people’. There are significant differences toward what kind of people they are referring: the elderly, people with mental issues, the unemployed, foreigners, and people with low-income levels. This points to different kinds of people but also to different causes for low participation and different consequences. Causes for an elderly person living in isolation can range from low mobility to loss of friends and family, while for people with mental ailments it is due to their lacking social skills. When referring to consequences citizens point to anti-social behavior, aggression or littering, which in turn leads to dirty streets and a tense atmosphere. The decline of generally accepted social conventions leads to people withdrawing from public space. It cases a need for the establishment of social conventions. Again, meaning plays a big role: different cultures and ages living in proximity of each other have different perspectives on what is a sensible set of social conventions. Some believe that kids hanging on the streets could cause them to join a gangs, others see it as something that helps in the development of social skills.

Aggregation of the data

Aggregating the data is essential to see how different individual quotes refer to the same mechanisms of the systems structure. In the next sections we will construct the CLD-model in stepwise fashion. The first important step in unifying quotes is through identifying meaning. “It is difficult to communicate our needs toward the municipal authority.” & “Out of pure frustration we quit contacting the municipal authority all together.”

Clearly these respondents have difficulties communicating their desires. Although desires can differ, 64 out of 220 respondents made similar statements. Identifying the underlying mechanism is relevant to understand why the respondents experience problems in communicating their desires. “I don’t feel the municipal authority has a clue on what is going on in the neighborhood, they should live here.” &” Instead of being referred to a phone number I would rather have a face to face conversation. This also makes it easier to explain my concerns”. These quotes, and many like them, refer to the distance respondents experience in communicating with the municipal authority owing to the lacking municipal presence in the district. This lacking presence complicates the mutual flow of information. Related variables and relationships can be named as well, as these quotes illustrate: “There should be more communication than just a local leaflet.” & “Another disappointment is the lack of communication surrounding the plans for introducing ‘container homes’, not all the households have been informed.”

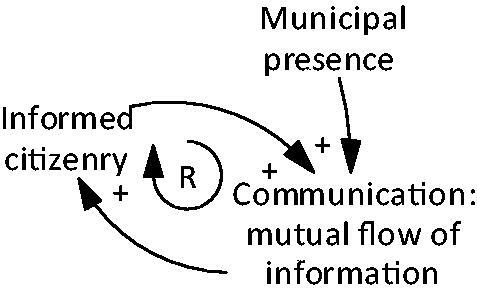

So next to the lacking presence, respondents also refer to the lack of information being provided by the municipal authority on different subject matters ().

Respondents are inclined to interact more if they are made aware of what is going on in their neighborhood. As such, informing citizens strengthens the mutual flow of information, creating a reinforcing loop.

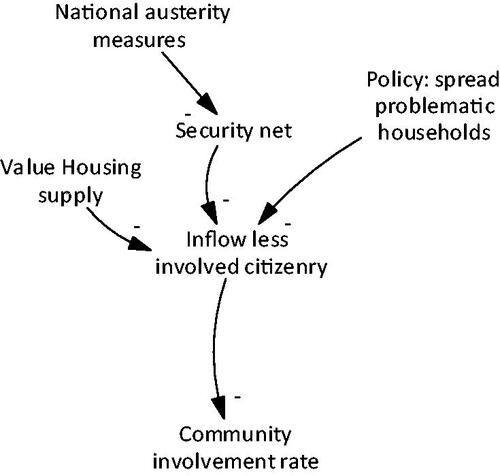

Other mechanisms can be derived likewise: respondents point to a couple of problems with differing subject matters but describe similar underlying and complementary mechanisms. “The flats attract a certain kind of people.” &” The influx of people with little or no perspective is too high, the neighborhood has changed dramatically because of it and it is getting progressively worse.” The influx of people with many different nationalities complicates communication. Besides low-cost housing, municipal policies further increase the influx: “A lot of people were forced from their homes with the planned demolition, due to the economic downturn it never happened. Those who stayed are now suffering for it.” & “In every stairwell one home is designated for people with a past: psychiatric patients, junkies, criminals, people with a trauma.”

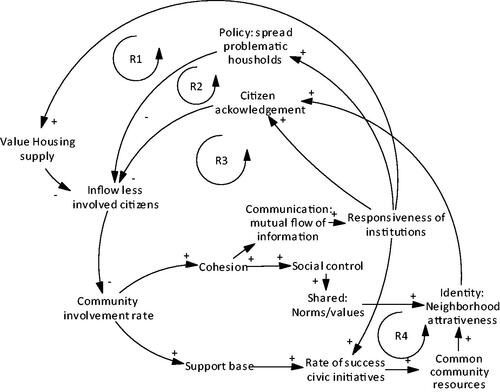

The cheap housing supply and municipal policies have created an inflow of people less willing or able to become involved in the existing community. The result is an overall decrease in the community involvement rate ().

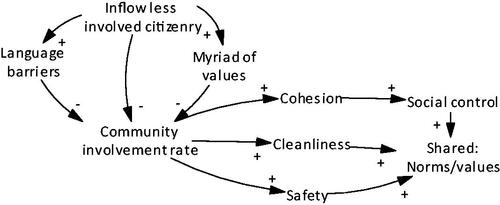

According to a lot of respondents the influx of less involved people has come at the cost of cohesion. The new citizens have some difficulties in adapting or upholding established rules, resulting in a fragmented community with different segregated groups and some even become isolated: “There are different groups living here that can’t stand each other, it doesn’t create a nice atmosphere, you don’t dare to say anything about it.” & “There is far less connection with the district, it would be a good thing to open a neighborhood center.”

Citizens refer to a variety of barriers as causes for the difficulties these groups encounter to become active community members.

Language barriers: “I don’t speak the language well and that complicates communication.”, “Many children are not good at speaking Dutch, they are raised in poverty and lack access to a computer, they are not a member of any social club.”

Mental barriers: “Many people are at the edge of functioning normally, they’re at home all day drinking beer.”, “It is not nice to come across those people, it gives an unsafe feeling.”

Cultural/norms barriers: “It is becoming more difficult to address each other’s behavior, People are ignoring the rules. For example with double Parking.”, “A Rotterdammer cleans his street, foreigners clean their streets to a lesser extent, but young Dutch folk don’t either.”, “My life choices (being a homosexual) aren’t accepted by barbarians, and that is mainly because of the Islam.”, “I feel discriminated against in my own country, for example with regards to Sinterklaas.”. These remarks were made by native Dutch people, but by other groups as well. The remark about Sinterklaas was made by someone from the Dutch Indies and the remark of the barbarians from the Islam was made by someone from Surinam. This underscores the many different perspectives describing the same mechanism.

starts with the community involvement rate variable from . The decline of community involvement, due to the influx of less involved citizens, causes lack of cohesion, and declining public cleanliness and safety. There is no longer a shared norm, and people are afraid to correct each other.

Many respondents describe this mechanism and the shock it caused to their community system. Some respondents are aware that dealing with this shock and demonstrating community resilience lies in its capacity to organize its civil society. Respondents show this awareness and intend to become more engaged in civil society. “It would be nice to have something in the district where residents can come together with food, and where they can discuss their problems. Young and old, and students can help as waiters.” & “There is definitely a need for common activities. Social cohesion can provide a way to get people involved in the community again.”

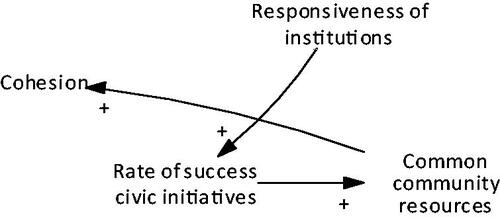

The respondents point to several barriers that block civil society from organizing to reestablish ‘cohesion’. The infrastructure where people can meet is missing; e.g. civil initiatives are insufficiently supported by the municipal authority. The fragmented composition of the populace, partly caused by municipal policies, further complicates creating those shared places. In short, the municipal authority (institutions) is seen as a cause of the existing situation; it is not fully prepared to lend support nor give funds to civic initiatives. “We are not being helped in trying to start something. I wanted to start a club for teenagers in order to educate kids, but the municipal authority won’t finance it. They would rather keep the money.” & “A possible solution would be to facilitate more initiatives that emerge from the community. Right now, the subsidy for the Castagnet (a neighborhood center) is probably going to stop. Without these subsidies these initiatives won’t last” ().

This feedback-loop creates a situation that leads to the district becoming increasingly less attractive. The lack of institutional responsiveness and the lacking opportunities for the community to organize, create a feeling that the citizens and their problems aren’t being acknowledged by institutions. Institutions fail to detect communal signals and fail to engage citizens in decision-making processes, while holding citizens to certain standards. The frustration that follows nudges ever more people to disengage from their community. Even those who were once involved are finding it harder to keep initiatives going. “The municipal authority expects things from you, while they do nothing.” & “Especially those that were active members within the community are fleeing the district, the community used to have a lot of ambulatory volunteers, in recent times that number has halved” (.

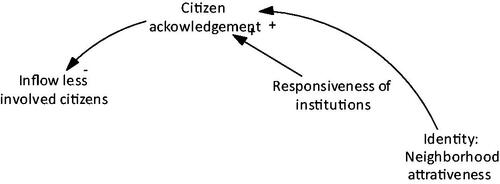

Lack of responsiveness from institutions is an important factor for creating and sustaining the situation in the community. This self-sustaining loops is shown in .

R1: Lack of responsiveness creates low quality housing supply that works as an attractor for the inflow of less committed citizens, lowering community involvement rate, complicating communication flows, and decreasing responsiveness.

R2: Lack of responsiveness shows by housing problematic households within the community which is in part responsible for the inflow of less committed citizens, lowering community involvement rate, complicating communication flows, and decreasing responsiveness.

R3: Lack of responsiveness leads to a lack of citizen acknowledgment, causing them to disengage from the public sphere, increasing the amount of less involved citizens, lowering community involvement rate, complicating communication flows, and decreasing responsiveness.

R4: Lack of responsiveness decreases the rate of successful civic initiatives, reducing community resources, making the neighborhood less attractive and less resilient, further decreasing the sense of citizen acknowledgement, increasing the amount of less involved citizens, which has an adverse effect on the support base for civic initiatives negatively impacting their rate of success, but also again the lowered community involvement rate complicates communication flows, and decreases responsiveness.

Through these loops, “responsiveness of institutions” ties the other factors and models together ().

Group model building session: validating the PVD-tool

In this GMB-session we aimed to establish and understand the situation in the district and the mechanisms causing it next to validating the PVD-tool.

After everybody introduced themselves we made sure everybody acknowledged the fact they were in a confidential setting and could speak freely.

After setting up the rules, the importance of getting to know the district through the eyes of its citizens was made clear. We asked the participants to name issues that according to them were the most important for the district’s livability.

The emerging discussion was facilitated in such a way that once respondents started mentioning details, we made them go back to the dialogue with the other participants. This created a more aggregated and abstract view of the district and the mechanisms at work. The discussion generated some variables, with their causes and consequences, that confirmed the preliminary model that we constructed.

Hence the model was presented to the group. The participants recognized the causal mechanisms in the model. Furthermore, it shed some light on why some stakeholders had taken their respective positions within the district and helped in finding the common ground.

During the session participants stressed the existence of fragmented networks in their community. This was underdeveloped in the preliminary model and included in the ultimate model.

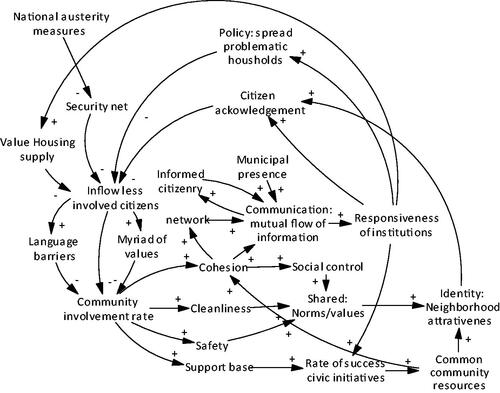

The final causal loop diagram represents the shared public values for Schiebroek-Zuid ().

Final causal loop diagram showing the disclosed public values

The final model incorporates all the ascribed public values and the structure of causal mechanisms that produce or fail to produce them. An important addition from the GMB-session is the ‘network’ variable, which is a result of ‘cohesion’ and positively impacts ‘communication: mutual flow of information’. The recognition and confirmation of the mechanisms in the preliminary model served as validation for the PVD-tool.

The aggregate picture confirms the theory that although citizens might have different perspectives they describe the same complex social system of which they are a part. An aggregate picture that exposes mechanisms that the municipal authority missed and in fact perpetuated (conf. Rouwette et al., Citation2011). Although the exposed themes or values themselves might not seem surprising describing amongst others a lack of: cohesion, a sense of safety, cleanliness in public space and above all a non-responsive local authority, the mechanisms or feedback-loops that produce them are. Without an insight into those mechanisms there will be little understanding into why values emerge and in the case of Rotterdam led to failed policies for the district. The PVD-tool is thus much more than just a stock taking tool of public values. It directs municipal attention toward the buttons it should push to create value. The discussion will show how the PVD-tool forms the basis for effective policies.

Discussion

Arguably, the biggest issue with existing Public Value approaches is placing citizens, especially those hard to reach, at the center stage. The PVD-tool is different because it does not rely on passively waiting for active citizens to make their concerns heard, on exclusive networks or panels, on the discretion of public managers, or even on secondary sources to determine what public value is. Instead, it is a proactive random non-normative exploration of needs that form a foundation for citizens to ascribe values in their community. It also adds to the debate about PV. The current state of affairs is that there is little (perhaps no) agreement about how PVs should be defined, which values are “public” and why, and how PVs should be classified and measured (Van der Wal et al., Citation2015). In practice there is no one set way to establish PV either. Some assume the situation should be leading in the type of approach to use: an optimal configuration that fits a given policy (Huijbregts et al., Citation2021). The PV-tool takes another approach as it simply considers public value to be what citizens consider to be publicly valuable and it is thus logical to extract values at that level.

The PVD-tool elicits mental models that guide the process of how individuals ascribe value. In other words, it tries to understand value creation in terms of individuals. Although some existing methods use deliberation which would be the second-best thing, incorporating deliberative procedures does not automatically make an approach democratic and might even legitimize a managed democracy from above (Dahl & Soss, Citation2014). In contrast the PVD-tool engages a random representative part of a community including those that have disengaged from society and makes them feel their opinions matter. To do justice to these personal accounts it introduces a way to take stock of those mental models in an unbiased manner with a LSD-technique. This deals with what Fukumoto and Bozeman (Citation2019) consider the major unresolved issues with PV: it helps with identification as it is not dependent on facilitating participation and it somewhat negates the problem of a high dependence on benevolent motives as it offers a guideline for value free extraction.

Once the mental models have been established the PVD-tool offers a way to harmonize widely differing perspectives. The key element here is treating different perspectives not as conflicting desired end-states, but as partly obscured views of the same system. Citizens in a particular neighborhood or district are all part of the same social system. Once asked about their daily experiences with that system they all describe the same system, they witness similar causal mechanisms. The PVD-tool creates a deeper understanding of the whole by deconstructing individually ascribed values into underlying needs, and the mechanisms that either fulfill them or not. It reconciles those underlying needs into shared needs that form the building blocks for public values and it looks at the mechanisms that create or destroy values. This is in line with Rhodes and Wanna (Citation2007) who consider the way forward in PV to be: first to recognize public value is about shared meaning that emerges through dialogue and reconfirmation in society. Second no one actor is in a position to impose a definition of public value. Third governments cannot command public value, they should monitor and oversee the process of public dialogue. It also offers managers skills not only to identify the relevant public values and understand those values, but skills to reconcile value conflicts which Dahl and Soss (Citation2014) consider to be requisites. Public values in this sense also center on the emergent properties of individual valuations as Meynhardt (Citation2015) considers them to be. The sum of which produces something that is more and different than the simple addition of the parts.

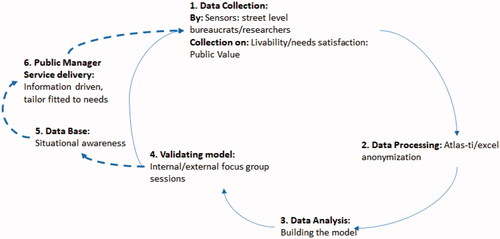

So what does this imply for public managers and how can it be implemented by public institutions? The PVD-tool can be viewed as the starting point of a data-cycle, a cycle that is meant to improve public service delivery based on high-quality analysis through the so-called OODA-loop; i.e. observation, orientation, decision-making and acting (Brehmer, Citation2005). This helps public managers develop their situational awareness and situational understanding: the perception of relevant elements in the environment and what influences them. This structural knowledge helps to improve the opportunity for responsive policies (Koliba et al., Citation2018). Using the PVD-tool is especially useful when institutions start to notice a lack of understanding in their environmental outcomes, with symptoms like the ineffectiveness of methods, the lacking acceptance of policies and unexpected impacts. Important conditions for the PVD-tool are personnel trained or skilled in random unbiased contact engagement (conf LSD-interviewing), personnel trained or skilled in data analysis and an organizational culture conducive of information driven processes.

The public manager aggregates and analyses the data gathered by the sensors of the team. The overarching goal is an information management system enabling the public manager to optimize public service delivery toward the satisfaction of needs (van Ooijen et al., Citation2019). The manager builds a preliminary model based on the data, which he validates by organizing focus groups in the field (conf. GMB). The manager can also discuss the model in focus groups with other managers from different disciplines within the organization. It is important that the data is shared throughout the organization and not be confined to certain silos. Once validated the data is fed into a centralized database enabling institutional memory, which is crucial for shared situational awareness and understanding. It helps to paint a common operational picture. Although this last step remains theoretical for now, the other steps (1–4) have been validated in this experiment (). Ultimately it is the organization that maintains the helicopter view over differing values. From that position the public organization and its managers can act on the combined interests of civil society synthesizing needs. Once services have been delivered a new data-cycle can start, where the impacts of services can be measured against the fulfillment of needs. Needs can thus function as the basic measures for effectiveness.

However, without an organizational culture that understands the value of information and its necessity for responsive policies such analyses are often blocked (Vaandrager, Citation2020). It needs support from leadership to guarantee a culture that dares to share information, with managers that dare to take responsibility for value creation (Aras, Citation2017). This culture shifts its focus in organizational goals, from the internal efficiency (fit objectives/results) to an external focus based on the effectiveness in meeting user-citizens’ needs. As such the organizational goals can be aligned with citizens needs to increase responsiveness, trust and legitimacy (van Ooijen et al., Citation2019). This outward orientation leads to the introduction of a process logic that aims at ensuring outcome effectiveness rather than output realization (Polese et al., Citation2018). The reliance on such a culture is still a major limitation of the PVD-tool. The same goes for the municipal authority of Rotterdam. Although results were enthusiastically received and they directed their attention toward unexpected mechanisms, even being sent to higher-ups for review, actual policy interventions are still to be taken.

Conclusions

At the very least this case study was able to elicit views from a representative sample and to synthesize the results into a preliminary common model which was validated by a small unrepresentative group to reach shared understandings about the dynamics and interrelationship between different individual needs. As the interviews and the causal mechanisms were taken from a representative group, we believe the model is validated. The PVD-tool applied GMB as this offered an ability to elicit and harmonize the value constructs of citizens, including those of the hard to reach. It has shown that situations might seem contradictory but as people experience the same system, they can describe similar mechanisms that are synthesized into what can be considered the common ground. The PVD-tool has the potential to increase situational awareness of institutions and through it offers them ways to increase confidence and effectiveness in decision making processes. Managers and professionals are well advised to take a (small) step back from the existing institutional frame and open-up to create values and avoid perpetuating values failures as was the case in Rotterdam. Thinking in standardized hierarchical institutional processes runs the risk of missing the underlying needs completely. Institutional considerations are important, but they can dilute public values disclosure. In other words, it could be very useful to ask what is needed based on objective, empiricist knowledge of the world first followed by what means are available to achieve it (Wagenaar, Citation2007). This is a form of value-based management (Hansson et al., Citation2014) that helps public management in two ways, first: the raison d’être for any public institution is to create public value for its citizens, second: when an organization knows what kind of values it is producing can it understand its true performance. Performance measurement is something that needs to be explored further; unfulfilled needs can act as such measures of effectiveness. The improvement or fulfillment of those needs could form policy targets which can be achieved by concentrating policy efforts on the causal mechanisms that block them from coming about. These systemic measures are preferable to consistent measures, because consistent measures are unable to capture changes in citizens perceptions (Faulkner & Kaufman, Citation2018). Once needs are satisfied and publicly shared value has been created, policies can be considered effective.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

David Vaandrager

David Vaandrager is a P HD-student at the Erasmus University of Rotterdam. He studied Human Geography at the University of Utrecht and Public Administration at the University of Rotterdam. His research centers on institutions and their ability to accommodate change stemming from their environment.

Peter Marks

Dr. Peter Marks is an associate professor at the Department of Public Administration at Erasmus University Rotterdam. Peter Marks is a member of the research group Governance of Complex Systems at the Erasmus University Rotterdam. His theoretical focus is on the development and application of complexity sciences in researching public decision making processes, e.g. the (global) decisionmaking processes of the Joint Strike Fighter since the nineties.

References

- Alford, J., & O'Flynn, J. (2009). Making sense of public value: Concepts, critiques and emergent meanings. International Journal of Public Administration, 32(3–4), 171–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01900690902732731.

- Aras, D. (2017). The conduct of intelligence in UN peacekeeping missions: A view from the field. Unpublished UN-report.

- Barlas, Y. (2007). System dynamics: Systemic feedback modeling for policy analysis. System, 1(59), 1-68.

- Benington, J., & Moore, M. H. (2011). Public value: Theory and practice. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Black, L. J., & Andersen, D. F. (2012). Using visual representations as boundary objects to resolve conflict in collaborative model-building approaches. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 29(2), 194–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2106

- Bozeman, B. (2002). Public‐value failure: When efficient markets may not do. Public Administration Review, 62(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00165.

- Bozeman, B. (2007). Public values and public interest: Counterbalancing economic individualism. Georgetown University Press.

- Bozeman, B. (2019). Public values: Citizens’ perspective. Public Management Review, 21(6), 817–838. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2018.1529878.

- Brehmer, B. (2005). The dynamic OODA loop: Amalgamating Boyd’s OODA loop and the cybernetic approach to command and control. Proceedings of the 10th International Command and Control Research Technology Symposium (pp. 365–368).

- Brown, P. R., & Head, B. W. (2019). Navigating tensions in co‐production: A missing link in leadership for public value. Public Administration, 97(2), 250–263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12394.

- Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Bloomberg, L. (2014). Public Value Governance: Moving Beyond Traditional Public Administration and the New Public Management. Public Administration Review, 74(4), 445–456. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12238.

- Checkland, P. (1983). O.R. and the systems movement: Mappings and conflicts. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 34(8), 661–675. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.1983.160.

- Churchman, C. W. (1974). Philosophical speculations on systems design. Omega, 2(4), 451–465. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-0483(74)90062-0.

- Dahl, A., & Soss, J. (2014). Neoliberalism for the common good? Public value governance and the downsizing of democracy. Public Administration Review, 74(4), 496–504. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12191.

- Davies, J. S. (2011). Challenging governance theory: From networks to hegemony. Policy Press.

- Doyle, J. K., & Ford, D. N. (1999). Mental models concepts revisited: Some clarifications and a reply to Lane. System Dynamics Review, 14(4), 411–415.

- Faulkner, N., & Kaufman, S. (2018). Avoiding theoretical stagnation: A systematic review and framework for measuring public value. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 77(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12251

- Fledderus, J., Brandsen, T., & Honingh, M. (2014). Restoring trust through the co-production of public services: A theoretical elaboration. Public Management Review, 16(3), 424–443. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.848920.

- Fukumoto, E., & Bozeman, B. (2019). Public values theory: What is missing? The American Review of Public Administration, 49(6), 635–648. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074018814244.

- Gerrits, L. (2012). Punching clouds: An introduction ot the complexity of public decision-making. Emergent Publications.

- Gigerenzer, G., & Selten, R. (2002). Bounded rationality: The adaptive toolbox. MIT Press.

- Hansson, E., Spencer, B., Kent, J., Clawson, J., Meerkatt, H., & Larsson, S. (2014). The Value-Based Hospital. A transformation agenda for health care providers (Value based hospitals, pp. 1–28). The Boston Consulting Group.

- Harrell, M. C., & Selten, R. (2009). Data collection methods: Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Rand National Defense Research Institute.

- Huijbregts, R., George, B., & Bekkers, V. (2021). Public values assessment as a practice: Integration of evidence and research agenda. Public Management Review, 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1867227

- Jørgensen, T. B., & Bozeman, B. (2007). Public values: An inventory. Administration & Society, 39(3), 354–381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399707300703.

- Jørgensen, T. B., & Rutgers, M. R. (2015). Public values: Core or confusion? Introduction to the centrality and puzzlement of public values research. The American Review of Public Administration, 45(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074014545781.

- Koliba, C. J., Meek, J. W., Zia, A., & Mills, R. W. (2018). Governance networks in public administration and public policy. Routledge.

- McCardle-Keurentjes, M. H., Rouwette, E. A., Vennix, J. A., & Jacobs, E. (2018). Potential benefits of model use in group model building: Insights from an experimental investigation. System Dynamics Review, 34(1–2), 354–384. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/sdr.1603

- Meynhardt, T. (2009). Public value inside: What is public value creation? International Journal of Public Administration, 32(3–4), 192–219. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01900690902732632.

- Meynhardt, T. (2015). Public Value: Turning a conceptual framework into a scorecard. In J. M. Bryson, B. Crosby & L. Bloomberg (Eds.), Public value and public administration (pp. 147–169). Georgetown University Press.

- Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating public value: Strategic management in government. Harvard university press.

- Moore, M. H. (2000). Managing for value: Organizational strategy in for-profit, nonprofit, and governmental organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29(1_suppl), 183–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764000291S009.

- Mulgan, G. (2011). Effective supply and demand and the measurement of public and social value. (pp. 212–224). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nabatchi, T. (2011). Exploring the public values universe: Understanding values in public administration. Public Management Research Conference Maxwell School.

- Nabatchi, T. (2012). Putting the “public” back in public values research: designing participation to identify and respond to values. Public Administration Review, 72(5), 699–708. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02544.x.

- O’Flynn, J. (2007). From new public management to public value: Paradigmatic change and managerial implications. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 66(3), 353–366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.2007.00545.x.

- Osborne, S. P. (2018). From public service-dominant logic to public service logic: Are public service organizations capable of co-production and value co-creation? Public Management Review, 20(2), 225–231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1350461

- Parsons, W. (2002). From muddling through to muddling up—evidence based policy making and the modernisation of British government. Public Policy and Administration, 17(3), 43–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/095207670201700304/

- Polese, F., Troisi, O., Carrubbo, L., & Grimaldi, M. (2018). An integrated framework toward public system governance: Insights from viable systems approach. In A. B. Savignon, L. Gnan, A. Hinna, & F. Monteduro (Eds.), Cross-sectoral relations in the delivery of public services (Vol. 6, pp. 23–51). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Rhodes, R. A. W., & Wanna, J. (2007). The limits to public value, or rescuing responsible government from the platonic guardians. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 66(4), 406–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.2007.00553.x.

- Rouwette, E. A., Korzilius, H., Vennix, J. A., & Jacobs, E. (2011). Modeling as persuasion: The impact of group model building on attitudes and behavior. System Dynamics Review, 27(1), 1–21.

- Rutgers, M. R. (2015). As good as it gets? On the meaning of public value in the study of policy and management. The American Review of Public Administration, 45(1), 29–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074014525833.

- Scanlan, C. L. (2020). Preparing for the unanticipated: Challenges in conducting semi-structured, in-depth interviews. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Scott, R. J., Cavana, R. Y., & Cameron, D. (2016). Mechanisms for understanding mental model change in group model building. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 33(1), 100–118.

- Spano, A. (2009). Public value creation and management control systems. International Journal of Public Administration, 32(3–4), 328–348. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01900690902732848.

- Sterman, J. D. (2000). Business dynamics-systems thinking and modelling for a complex world. McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

- Strathoff, T. P. (2016). Strategic perspectives on public value. Difo-Druck GmbH.

- Thiering, M. (2014). Spatial semiotics and spatial mental models: Figure-ground asymmetries in language (Vol. 27). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

- Vaandrager, D. (2020). A systems approach to exploring institutional absorptive capacity and adaptability. Emergence Complexity and Organization (accepted).

- Vaandrager, D., Gerrits, L., & Bressers, N. (2015). Reconstructing the blue connection: A systemic inquiry into the improbable project of building a new river through a (sub)urban area: reconstructing the blue connection. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 32(6), 689–706. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2297.

- Van der Wal, Z., Nabatchi, T., & de Graaf, G. (2015). From galaxies to universe: A cross-disciplinary review and analysis of public values publications from 1969 to 2012. The American Review of Public Administration, 45(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074013488822.

- van Ooijen, C., Ubaldi, B., & Welby, B. (2019). A data-driven public sector: Enabling the strategic use of data for productive, inclusive and trustworthy governance. OECD Working Papers on Public Governance No. 33.

- Vennix, J. A. M. (1996). Group model building: Facilitating team learning using system dynamics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Wagenaar, H. (2007). Governance, complexity, and democratic participation: How citizens and public officials harness the complexities of neighborhood decline. The American Review of Public Administration, 37(1), 17–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074006296208.

- Walters, J. P. & Litchfield, K. (2015). Investigating the benefits of group model building using system dynamics for engineers without borders students. 2015 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition (pp. 26–1039). American Society for Engineering Education.

- Weller, S. C., Vickers, B., Bernard, H. R., Blackburn, A. M., Borgatti, S., Gravlee, C. C., & Johnson, J. C. (2018). Open-ended interview questions and saturation. PLoS One, 13(6), e0198606. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198606