ABSTRACT

Exploring how the information flow of social studies textbook spreads is negotiated in teacher-led interaction, the concern of this study is the conscious and critical use of teaching material in diverse student groups. The study involved a teacher and her Grade 6 students in a school with many migrant language learners. The data was gathered by observations, field notes, voice recordings, and the collection of teaching materials. Using social semiotic theory of visual design, the analysis of the textbook used in instruction shows that the layout perpetuated a Western-centric view of a divided world, along with an individualistic and anthropocentric view of environmental sustainability. The oral interaction, highlighting different text elements, largely reinforced the meaning perspectives promoted in the textbook. However, on occasion, the students were positioned to take a more analytical stance. Implications for using knowledge about information flow in textbooks to promote critical literacy practices in teaching are discussed.

Introduction

Navigating subject content curriculum involves the negotiation of discourses, or meaning perspectives, shaping the way knowledge is construed. Therefore, a critical awareness of these perspectives is crucial. This is necessary in the teaching and learning of social studies, which often entail learning about ways of participating in society as a citizen and ways of looking at the world (Miller-Lane et al., Citation2007). A critical orientation to the representation of knowledge is particularly important in the teaching of linguistically diverse students’ groups, in which the students draw on a heterogenous basis of knowledge and experiences which can clash with hegemonic perspectives (Janks, Citation2010).

This article, based on a classroom study of civics teaching in a Swedish Grade 6 class, is concerned with the opportunities for teachers and students to look critically at the curriculum material used in the teaching of social studies. Previous research has addressed the importance of supporting students to “explore education in a way which escapes colonized ways of thinking” (Hickling-Hudson, Citation2006). This includes the Western-centric perspective of a divided world where prosperous Western societies are contrasted with countries construed as homogeneously lacking and uneducated (e.g., Pashby & Andreotti, Citation2015) as well as stereotypical and antiquated views of life in other countries (Hannah, Citation2017).

In relation to the teaching of social studies in Nordic countries, textbook analyses have highlighted the transmission of Western-centric perspectives (Ajagán-Lester, Citation2000; Kamali, Citation2006; Mikander, Citation2015). Deficit perspectives on life in non-Western countries have also been noted in international research on social studies textbooks (e.g., Marmer et al., Citation2010; Odebiyi & Sunal, Citation2020). In analyses of civics textbook material relating to issues of climate change, Ideland (Citation2019) has shown that the perspective of environmental sustainability is shaped by neoliberalism, as a matter of exercising consumer power (see also Lloro-Bidart, Citation2017). As argued by Kopnina and Cherniak (Citation2016), foregrounding of economic considerations, such as fair allocation of resources, also conveys an anthropocentric view, limiting the concerns to humans only. A more general concern is the potential transmission of monocultural perspectives in content instruction involving migrant language learners (cf. Cummins, Citation2000). Although there is an increasing awareness of using migrant language learners’ previous knowledge and experiences as a resource in Sweden, the teaching may still be restricted by monocultural norms shaped by a history of relative ethno-cultural homogeneity (discussed in Cummins, Citation2017: García & Seltzer, Citation2016). A previous study (Walldén, Citation2021) showed how linguistically diverse Grade 6 students were uniformly positioned as privileged Swedish citizens in a curriculum area about living conditions.

I seek to contribute to the field by bringing the critical analysis of social studies textbooks closer to ongoing teaching practice. While previous research has used social semiotic perspectives to describe written genres and the oral negotiation of disciplinary language in different school subjects (e.g., Christie & Derewianka, Citation2010; Halliday & Martin, Citation1993; Macnaught et al., Citation2013; Walldén, Citation2019), less research has been devoted to analyses of visual characteristics of social studies textbooks. Moreover, studies incorporating multimodal analysis of textbooks tend to focus on the texts themselves, for example, how text elements serve to convey content knowledge (Martin & Rose, Citation2008; Selander & Danielsson, Citation2014) or values (e.g., Feng, Citation2019). A large textbook study by Bezemer and Kress (Citation2008, Citation2016) has highlighted the increasing importance of images and layout. The research gap filled by the present study is the analysis of visual properties of social studies textbooks in relation to how the texts are used and talked about in the discursive practice of teaching and learning.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to contribute knowledge of how the information flow of social studies textbook layout is negotiated in teacher-led interaction, focusing on the following questions:

How is the visual organization of textbook spreads negotiated when the teacher highlights different text elements in classroom interaction?

How does the classroom discourse on text elements relate to meaning perspectives in social studies?

In addition, these questions form a point of departure for discussing the pedagogic potential in using knowledge about the information flow in textbook material to promote critical text awareness.

Theoretical framework

In this section, I will present the theoretical underpinnings of the study, concerning participation in critical literacy practices and the social semiotic analysis of visual design.

Critical literacy in disciplinary learning

Ideological perspectives potentially shaping the meanings offered in social studies teaching, such as individualism, West-centrism and monoculturalism (see previous section) will be referred to in the present study as meaning perspectives (cf. Mezirow, Citation1990; Walldén, Citation2021). As such, they are frameworks for value judgements and belief systems that can either be assimilated uncritically or learned explicitly. Wilinsky (Citation1998, p. 3) has argued that the transmission of “colonially tainted understandings” form an enduring part of the Western educational project according to which students learn to divide the world, for example, into East and West. For a decolonizing curriculum, the promotion of critical thinking is key (e.g., Halagao, Citation2010). Critical perspectives on teaching material and other resources of learning can also be used to challenge the naturalization of other divisions, such as between humans and animals (e.g., Kopnina & Cherniak, Citation2016).

In line with the principles of Critical Discourse Analysis (Fairclough, Citation2015; Gee, Citation2014) and Critical Literacy (Janks, Citation2010; Macken-Horarik, Citation1998), I view the close examination of features of texts as crucial for developing a critical understanding of how reality is construed in curriculum material according to different meaning perspectives. As expressed by Freire and Macedo (Citation1987), reading the word is reading the world. Therefore, in the discursive practices of content teaching, it is important to promote opportunities for objectifying instructional texts (Langer, Citation2011) and discussing the ideas and value systems perpetuated therein (Luke & Freebody, Citation1999). Inquiries into critical literacy practices (cf. Janks, Citation2010; Walldén, Citation2020a) have shown that the diversity present in such groups can function as a resource for reading against the grain of the text and challenging the perspectives conveyed. It follows that the goal of education should not be to present a single message “truth” to the students, but to create opportunities for the students to reflect on their context (Andreotti, Citation2006).

A social semiotic perspective on visual design

As shown already by Street (Citation1984), participation in literacy practices not only involves verbal language; it entails making use of visual resources, such as headings and layout. From a social semiotic perspective, images and layout constitute distinct modes which, like speech and writing, carry different meaning potentials or affordances, for meaning making and learning (e.g., Bezemer & Kress, Citation2016; Kress, Citation2003). Crucially, the use of these affordances by sign-makers, such as producers of textbook material, is shaped by power relations (Bezemer & Kress, Citation2016, p. 31, see also previous section).

In the present article, my use of social semiotic theory focuses on layout (Kress, Citation2014; Kress & van Leuween, Citation1996/2006). Of particular interest are different information values which can be ascribed to text elements placed on the left and right in multimodal texts. The elements placed on the left are presumed to be already known to the reader as part of their culture—“a familiar and agreed-upon point of departure of the message” (Kress & van Leuween, pp. 180–181). Thus, this part of the message can be labelled as given. In contrast, the new part of the message, displayed on the right, is something to which the reader is expected to pay special attention, for example, something not yet agreed upon.

As is stressed by Kress and van Leuween (Citation1996/Citation2006), this information structure might not necessarily correspond to what the reader (or producer) of the layout actually perceives as given and new information; however, the message must still be read according to that information structure. In social studies textbooks, the given would likely be that which the producer assumes is naturalized or familiar to the student, while the new provides the essential and, until this point, unknown information to be learned. To a lesser extent, I will also highlight the information value of top and bottom of the textbook spreads. The top position presents the ideal, a generalized essence of the message, while the bottom is devoted to something real, conveying more detailed or specific information (Kress & van Leuween, Citation1996/2006, pp. 186–187).

Although many other aspects of visual design come into play in textbooks, such as color, salience, framing and the various characteristics of images (e.g., gaze, modality, and degree of contextualization), I predominantly focused on the layout, since this feature of the textbook spreads is particularly aligned with the teacher’s ambition to promote the students’ awareness of different text elements. As discussed in the previous section, an orientation towards the flow of information seems to be lacking in previous research on social studies text material.

In my analysis, I explored how the parts of messages presented as given and new in the textbook spreads were negotiated in oral interaction. My point of departure for the study was that teaching explicitly focused on creating awareness of different text elements in textbooks constitutes an interesting context for the exploration of how teaching material is used and interpreted in discursive practices of teaching, with particular emphasis on layout and information flow.

Method and material

In this section, I describe the participants, the collected material, and the analytical approach of the study.

Participants

The study involves a teacher and 40 Grade 6 students, divided into two groups. My reason for choosing this school was strategic (Thomas, Citation2011), as I had learned that the school emphasized creating opportunities for interaction based on disciplinary texts, thereby aligning with my general research interest. Another consideration was that the school had linguistically diverse students: according to the teacher, a third followed the curriculum for Swedish as a second language. While no specific information was collected about the students’ linguistic backgrounds, it can be generally stated that the linguistic diversity in Swedish classroom is connected to migration, not least the “European migrant crisis” emerging in 2014. Common migrant languages include Arabic, Serbo-Croatian, Polish, Kurdish languages and Persian. According to official statistics, 50% of the students at the school have a “foreign background,” referring to students either born in another country than Sweden or whose parents were both born outside Sweden. The participant teacher, certified in teaching Swedish, English and social studies, held a career position as “First Teacher” and had a special role in coordinating teamwork according to the teaching aims of the school.

Although the teacher had several years of teaching experience, she explained that her participation in the study marked the first time she approached social studies texts, and, more generally, text elements in factual texts in the way explored in the present study. In a scheduled meeting preceding the teaching focused on in the article, we talked broadly about the teaching she aimed to conduct, during which she explained her being inspired by Adrienne Gear’s (Citation2008/2015) reading strategies for factual texts (“non-fiction reading power”). Throughout the study, she specifically expected students to “zoom in” on different “text features,” Gear’s term denoting elements of factual texts other than main parts of verbal text. The teacher’s general aim was that the students learn to approach factual texts in more conscious and strategic ways.

It is worth mentioning that, although the Swedish subheading of Gear’s book translates as “Teaching Critical and Reflexive Reading,” the reading strategies advocated do not involve making connections between texts and power relations (cf. Janks, Citation2010). It follows that advancing such perspectives on texts may not have been a priority for the participant teacher. While the teaching was not conducted according to the social-semiotic and critical understanding of texts advocated in the present study, the explicit orientation to different text elements constitutes an interesting context for researching how the meanings conveyed by textbook layout are perpetuated, and, potentially, challenged in teaching. After the study, I shared some of the analyses with the participant teacher and some of her colleagues, highlighting the potentials for taking the attention to layout and text elements in a more critical and social-semiotically informed direction.

In connection with the observed lessons, I had occasional informal talks with the teacher about the teaching and text material. As the study progressed, I shared some thoughts with the teacher about the information flow between given and new as well as real and ideal in the textbook spread. In a scheduled follow-up meeting, the teacher expressed an appreciation for our talks, and their contributing to her awareness of the composition and layout of the texts. These talks generally followed rather than preceded the instances of interaction studied, so I do not believe that they had a direct impact on the teaching.

From an ethical standpoint, I sought and received written consent from all participants in the study, including written consent by the caregivers of the students. The study was conducted in accordance with principles advocated by the Swedish Research Council (Citation2017).

Material

The material was collected by way of field notes, transcribed audio recordings (16 hours) and documentation of teaching material throughout 16 lessons spanning five weeks in early 2020. From an ethnographic perspective, I mostly took an observer role (cf. Fangen, Citation2005), seated at the back of the classroom taking notes and managing a digital audio recorder. However, I provided some linguistic support in peer discussions about unknown words—an activity not focused on in the present article.

In order to explore how the information flow of social studies textbook spreads is negotiated in teacher-led interaction, I particularly focus on five lessons, each lasting about 1 hour, devoted to application of the “zooming in” strategy on three spreads in the textbook used in instruction. This activity constituted the lion’s share of the selected lessons. It was often preceded by the teacher talking more generally about the importance of using reading strategies and followed up by students’ individual readings of the text, sometimes accompanied by instructed note-taking.

The textbook used in instruction, Puls Samhällskunskap (Stålnacke, Citation2012) is part of a high-profile series for the teaching of social studies from a large publisher of textbooks in Sweden. The teacher had not previously used it but found it suitable for her aims regarding content and possibilities for practicing reading strategies. It is worth mentioning that Sweden has a standard-based national curriculum which gives the teachers a high degree of autonomy when selecting and using teaching material.

Analytical approach

In the analysis, I employed classroom discourse analysis based on social-semiotic theory. The oral interaction was primarily analyzed in terms of how the content of the exchanges corresponded to the parts of messages presented as given and new on the civics textbook spreads focused on during the teaching. The emphasis on the given-new relation, rather than, for example, the top-bottom relation, is informed by the data through an abductive analytical process (e.g., Alvesson & Sköldberg, Citation2008, pp. 55–56). The different orientations to the information structure are described by the headings in the two major result sections. From an interpersonal standpoint, I was also interested in how the teacher engaged the students in dialogue about the texts studied. This involved how the teacher directed students’ attention to text features by asking questions and following up on their responses according to the triadic exchanges typical of classroom discourse (e.g., Mehan, Citation1979; Sinclair & Coulthard, Citation1975), alongside other interpersonal resources for engaging the students, such as the use of imperatives, exclamations, and evaluative resources of language (cf. Martin & Rose, Citation2007; Martin & White, Citation2005; Walldén, Citation2020b).

According to the principles of Critical Discourse Analysis (Fairclough, Citation2015), I see the interaction drawing on the teaching material as part of the discursive practices of teaching civics, in which texts are interpreted and used. This discursive practice will be considered in relation to the larger social order entailing the transmission—and possibly challenging—of dominant meaning perspectives.

Although my main analytical focus is on the oral exchanges about the text material, I have also highlighted properties of the text elements themselves. This was necessary to relate the interaction to the material it is based on, and, in part, to show possibilities for additional elaboration on the layout of the textbook spreads. Audio recordings have been transcribed by the author, who also translated relevant excerpts from Swedish to English. The transcripts were cross-referenced with field notes and teaching material in the analysis. The reliance on audio recordings can be seen as a limitation since video recordings would have enabled analysis of how the teacher pointed to different text elements and conveyed attitudes to the texts through non-verbally. However, video recordings would have been more intrusive from an ethical standpoint. I believe that the method and analytical approach used in the present study provide sufficient ground for contributing knowledge about how textbook spreads are negotiated in teacher-led interaction, especially in light of the lack of previous research.

Results

The results are organized according to two different themes in the studied teaching: environmental sustainability, the subject of one of the spreads, and human rights along with living conditions, the topic of two other spreads. The analysis will be presented in two stages: firstly, a description of how the oral interaction related to the information flow of the textbook spreads and conveyed knowledge about the visual organization of the textbook layout (Research Question 1), followed by an analysis of how the studied interaction, based on the textbooks, relates to meaning perspectives on the relevant content (Research Question 2).

Learning how to be an environmental hero

Before turning to the classroom interaction, it is necessary to describe some characteristics of the textbook spreads used in instruction. The first one () related to environmental sustainability.

Figure 1. Textbook spread from Puls Samhällskunskap about environmental sustainability (Stålnacke, Citation2012, pp. 116–117).

Under the heading “Our globe must be enough for everyone” (“Vårt jordklot måste räcka till alla,” see ) the reader is introduced to a letter written by two children about their concerns regarding the environment (given information) and different suggested ways of becoming an “environmental hero” (miljöräddare) (new information). The given information points to the new information in two major ways: the concluding phrase “Become an environmental hero, too!” and a speech bubble from the girl depicted with the text “Here you can see my and Malte’s tips on what we can do. Maybe you have some tips too?” Also, the girl is pointing towards the new information.

Before the whole-class discussion, the teacher had asked the students to analyze the text features in the spread. When the teacher asked what the text could be about, the students focused on what was presented as new on the spread: different pieces of advice on how to become an “environmental hero.”

Excerpt 1 Nelida: That we start sorting, or not start. We should sort our waste properly. Teacher: Mm. Which image tells us about that, do you think?Nelida: At the bottom.Teacher: Yes, right. The one at the bottom [pointing].

The teacher wrote suggestions from the students on the whiteboard, in the form of a thematic mind-map. As no one remarked on features on the page presented as given information, the teacher pointed out the heading: “Our globe must be enough for everyone.”

Excerpt 2 Teacher: What does this text feature say? The heading? I hope you read it because it’s almost the most important one of all eight. Of all the text features. / ... / Yes, Stefan, please read.Stefan: Our globe must be enough for everyone. Teacher: Yes, this says something a bit different from what you have said here. [pointing at midmap] Our globe must be enough for everyone.

The teacher often referred to headings as particularly important text features. In the above exchange, she appeared to point out that the students’ contributions, noted on the teacher’s mind-map, had not covered the message presented as given information in the textbook spread: “this says something a bit different.” While the students readily reconstructed the presented advice on “saving” the environment, they had some difficulty in explaining the meaning of the heading. Illustrative examples of suggestions from students were “Everyone is worth the same” and “everyone should get as much as we get.” The teacher followed up the suggestions like this:

Excerpt 3 Teacher: Exactly. Just wait a bit. I need to write this. Everyone is worth the same. [writing] Everyone should get the same. I think this is a great sentence. It isn’t just us rich people in Sweden who should get what the earth has to offer. Everyone should get it all around the globe. But if all the people around the globe use as much of the earth’s resources as we do in Sweden, then we would barely have any globe left.

After a positive evaluation of the answers, the teacher elaborated on the meaning of the heading, setting a privileged “us” in Sweden in relation to “everyone around the globe.” She also pointed out the excess use of resources in Sweden “we would barely have any globe left.” The heading relies on a metaphorical use of globe (in Swedish jordklot, a compound translating literally as earth globe). While the letter—not to be read by the students at this point—provides a clarification of what was presented as given information, the metaphor is unexplained, underscoring its status as a taken-for-granted part of the given. In summary, the analysis of how the visual organization of the textbook was negotiated in the interaction shows that the students quite easily identified the new, showing familiarity of “environmental-saving” consumer behavior, but needed support with the given.

In one of the two observed sessions regarding this spread, the teacher asked the students about why the cartoon children depicted as part of the given information were part of the text. The following exchange is depicted below.

Excerpt 4 Teacher: Now, I will give you a tricky question. Let’s see if you are up for it. This is, like, us analyzing the text. / ... / Why do you think that the ones who have written this text have chosen to do a letter with two children? / ... / Instead of an ordinary text? / ... / They must have something in mind with this. / ... /Student 1: Maybe because the children have so many things about the environment. Because it affects their future more than grown ups’.Teacher: Yes, it could be. / ... /Student 2: Maybe so we’d understand the importance already as children, to think about what we do with the environment.Teacher: Right. Great. That could also be it. / ... /Student 3: Perhaps mostly because children will read this book and then they have children to show that all children can do the same thing.Teacher: Yes, right. Wow, you were much better at this than I imagined. Alexander?Alexander: Every child can change something.Teacher: Yes. What did you want to say Amila?Amila: Eh maybe they are going to send this letter to politicians.

The teacher foreshadowed that it would be a “tricky question” geared at analyzing the text. This marked the only time when the teacher explicitly pointed to the authors’ intention with design choices. The teacher affirmed students’ answers concerning children being particularly affected by the environment and more suited to propose suggestions to other children about “saving” the environment (“do the same thing”). In a later elaboration, the teacher offered that the choice of text type, a letter instead of a “traditional text,” could better engage the reader. Thus, the communication drew attention to how these “text features,” as part of the message’s given, could serve to construct a relationship with the intended reader conducive to learning about taking care of the environment. Concluding the exchange, Amila offered a different interpretation by suggesting that the letter constituted a political action. This is further discussed below.

Negotiating meaning perspectives on environmental sustainability

The analysis will now turn to how classroom discourse on text elements related to meaning perspectives conveyed by the textbook spread (Research Question 2).

The teacher found it necessary to clarify the meaning of the heading on the page presented as given, “Our globe must be enough for everyone,” indicating that the metaphorical use of “globe” was difficult to grasp. In doing so, she specified it as “the earth’s resources” and pointed out the necessity of reducing the use of resources in Sweden (Excerpt 3). As for the meaning perspectives on the instructional content presented as given by the spread and perpetuated in the teacher’s elaboration, they appear to be shaped by an anthropocentric view, focusing on the environment’s impact on “people around the globe.” The “environment-saving” measures presented as new information were quickly recognized by the children and convey the perspective of environmental sustainability as a matter of individual choice. This individualistic perspective, indicated by the two children presenting their concern for the environment (given) and children’s heroic activities as the solution (new), was not particularly reinforced by the teacher. Instead, she stressed the collective responsibility of “we ... in Sweden,” implicitly indicating a divide between rich Western countries and other countries.

However, in the discussion about the role of the depicted children on the spread, several student replies aligned with children’s individual responsibility, such as “Every child can change something,” “all children can do the same thing,” and “understand the importance already as children ... what we do with the environment” (Excerpt 4). Consequently, the interaction perpetuated the meaning perspective of individualism conveyed by the spread. Interestingly, the possibility of another perspective, not privileged in the spread, was offered by Amila in the comment: “maybe they are going to send this letter to politicians.” Having no basis in the letter itself (being targeted at other children, that is the students), the student likely used knowledge about young people’s environmental activism holding politicians, rather than individual consumers, responsible for issues of environmental sustainability. Apart from this, the teacher’s and the students’ negotiation of the information flow perpetuated an individualistic and anthropocentric views of environmental sustainability. In addition, the teacher’s clarification of the information presented as given also served to perpetuate a meaning perspective of a divided world.

Learning about living conditions in a divided world

The rest of the teaching observed was largely concerned with living conditions and human rights. In the three coming subsections. I show how the visual organization of textbook spreads was negotiated when the teacher highlighted different text elements on the relevant textbook spreads (Research Question 1). In the concluding subsection, I relate the interaction to meaning perspectives conveyed in the teaching (Research Question 2).

The teacher and the students pointing out tensions between the given and the new

In contrast to the spread about saving the environment, the first spread relating to living conditions is clearly structured around sections of written texts (). In whole-class interaction, the teacher particularly pointed out the headings in the spread, listing them on the whiteboard.

Figure 2. Textbook spread from Puls Samhällskunskap about people moving between countries (Stålnacke, Citation2012, pp. 118–119).

Having asked whether any of the headings seemed more important than others, the teacher gave a clue as to what the students could expect from the spread.

Excerpt 5 Teacher: Maybe it’s like this, these days, that we are much closer than we were 50 years ago or 100 years ago. When it wasn’t that easy to travel and we didn’t have the internet and so on. We’ll see. / ... / And then you read and look at those slightly smaller headings. Then you might see that maybe it’s not / ... / pleasure trips they talk [about]. It could be another kind of trip or contact with the world you can read about in this text. Maybe.

In her comment, the teacher, referring to the different headings, foreshadowed how the spread offered different perspectives on the theme of the main heading “Near to the world” (“Nära världen”). More implicitly, she drew attention to the tension between what is presented as given and new on the spread: “another kind of trip or contact with the world.”

After this introductory exchange, the teacher asked the students to discuss in pairs what the different headings might refer to. In the whole-class follow-up, the students were more clearly positioned to consider the information flow between the given and the new. While discussing the spread, the teacher was pointing at the page presented as given. It showed images of a laughing, blond child reading a travel brochure and another child, accompanied by an adult, swimming alongside a fish while scuba diving.

Excerpt 6Teacher: Look at these pictures on this page. What are they like? [pointing] / ... / Is it refugees on these two pictures? / ... /Behram: No.Teacher: No, what kind of children are these? What do you think they are doing?Behram: They are out travelling.Teacher: Yes, I also think they are on a vacation trip. And then, I don’t know. Then you might think they are not refugees. / ... / But if you look at the next page. Here, it says that it’s going to be about refugees. And it says, “A boy from Somalia.” What do you think you’ll read about there? / ... /Markus: He’s fled from another country.

Using wordings which refer deictically to the spread, such as “this page,” “these,” “the next page,” the teacher pointed to a tension between the heading “Refugees” (“Flyktingar”)—belonging to what is construed as new—and the vacation-oriented images of children on the page presented as given. This was reinforced when the teacher, later in the discussion, commented further on the images.

Excerpt 7 Anders: I think they are children in a refugee shelter.Teacher: Yes. Why do you think that? Anders: Because in the background it looks like many people are living in tents. And they wear, like, blankets and stuff. Teacher: Yes. Exactly. If you compare with these children on this page, then I get. It’s an entirely different atmosphere in this picture, isn’t it? / ... / They don’t exactly look happy. But it doesn’t look very fun behind them.

One of the students, Anders, referred to the image shown beside the section about refugees. The teacher followed up by asking the students to note the different “atmosphere” in this picture in comparison with the images of vacationing children presented as given. In doing this, she used evaluative resources of language (“don’t exactly look happy,” “entirely different,” “doesn’t look very fun,” cf. Martin & White, Citation2005). In this way, the students were positioned to consider the different parts of the message presented as given and new on the spread.

In the above exchanges (Excerpt 6–7), the attention to the information flow was mostly sustained by the teacher. In the other group, some of the students pointed out the tension between the given and the new. In an initial whole-class exchange about what can be gleaned from the different heading, Joel stated succinctly:

Excerpt 8 Joel: For example, some do well here, and some are worse off. [moving his hand from on page to the other]

The contribution distilled the meaning offered by the information flow of the spread: some children “do well” and some are “worse off.” Joel further emphasized this by placing his hand, first on the page providing the given information, before moving it to the one providing the new. In the discussion of the images, the teacher asked about the images of the vacationing people.

Excerpt 9 Teacher: Is it a kind of trip they’d like to do? Or do you think they are forced to? How do they seem? Happy or?Michael: No, like, they want to. / ... /Amila: If I look at these pictures, and in the headings, I think it’s like those below the girl are going to a country and have the possibility to go and see everything there. See traditions. Could be impressions. While the refugees have to go.

Based on the teacher’s question about the images and the nature of the journey, Amila related the child reading the travel brochure (“the girl”) to the heading “New impressions and old traditions” (“Nya intryck och gamla traditioner”). In doing so, she contrasted people who “have the possibility to go and see everything” with “refugees hav[ing] to go.” In this way, she reconstructed the tension between what is presented as given and new on the textbook spread.

Negotiating general knowledge as part of the ideal and examples as part of the real

In one of the groups, the teacher explicitly highlighted the relationship between the ideal and the real on the page presenting the new (see , right side).

Excerpt 10 Teacher: A boy from Somalia, what do you think you get to read there? / ... / If you compare with what you can read here? [pointing at the top of the page]Student 1: Eh then you know exactly where the person comes from.Teacher: Yes exactly. Student 2: I think they, like, tell us about his journey.Teacher: Yes, precisely. Exactly. And what can we call it?Student 3: A recount. Teacher: Yes, a bit like a recount. Kind of like an example. Here there are facts and here you get a small example [pointing]. Maybe so we’ll get into the text and find it more interesting.

In this exchange, the teacher pointed to the ideal (top of the page), constituting general information about seeking asylum as a refugee, and the real (bottom of the page), a specific example of a boy fleeing from Somalia. Further highlighting the information flow, the teacher and students used metalanguage to compare the text elements: “recount,” “facts,” “a small example.” The teacher also pointed out a function of the real: engaging the reader in learning about the new. As in the exchange about the children depicted on the previous spread, this marked a further step towards looking more analytically on the text.

The right to schooling: Reinforcing the given

The next spread negotiated in instruction, “Children in the world” (“Barn i världen”), is comprised almost entirely of what the teacher, drawing inspiration from Gear (Citation2008/Citation2015), considered to be text features ().

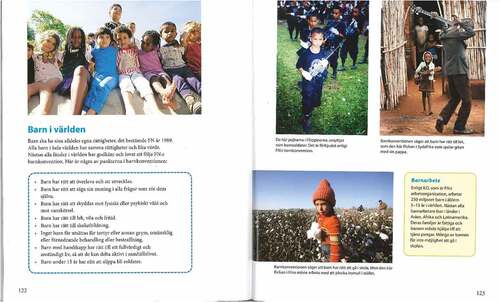

Figure 3. Textbook spread from Puls Samhällskunskap about rights and living conditions of children in different parts of the world (Stålnacke, Citation2012, pp. 118–119).

The given part of the message consists of an image of children of different skin colors sitting together, the heading being followed by a short text introducing the Convention on the Rights of the Child (“Barnkonventionen”) and a text box listing different rights. The new part of the message consists of three images with short captions: children carrying rifles, a laughing girl playing the guitar between bamboo structures while looking at an adult brandishing a guitar, and a girl in a cotton field. In addition, there is a fact box describing child labor (“Barnarbete”).

In the studied lesson focusing on this spread, the teacher chose to model the benefit of “zooming in” on different text features.

Excerpt 11Teacher: If I glance at this image, I see these children. All of them look completely different. There is a girl, I think, who’s blond. Then, there is a really dark boy. Then, there is a girl looking like she might be from Africa. Then, there are some who are a bit lighter, someone a bit half-light. I think this picture looks like this so you’ll understand it’s about children in the whole world. In all the countries. / ... / Then, I move on to look at this image. And, hey, what’s up with that? Look, there are actually a child with a weapon in hand.

As shown above, she started by commenting on the different skin colors of the children presented as given, and then, more dramatically, commenting on the images presented as new. She continued the monologue by remarking on the depicted rifle-wearing children being of the same age as the students “or even younger,” and the depicted children having to work as child soldiers instead of going to school. She also asked the students to relate the images to their own experience: “What if you were 11 and already had shot another person dead?” The teacher used exclamations, “Hey,” imperatives, “Look,” and questions which positioned them to imagine being in the same situation (cf. Martin & Rose, Citation2007). This clearly pointed to the potentially unexpected and problematic nature of parts of messages presented as new.

In the whole-class interaction following the students’ own reading of the text features, the teacher asked several questions about the girl picking cotton, similarly oriented to her previous comments on the child soldiers:

Excerpt 12 Teacher: How do you think it would be to pick cotton and work with that? Anders? Anders: Boring.Teacher: Why?Anders: Do the same thing over and over.Teacher: The same thing over and over. Yes, so that would be boring. What else?Ala: They don’t get any education.

Once again, the teacher positioned the students to imagine being in the same situation, the students using evaluative wordings such as “boring” and “do the same thing over and over.” A student, Ala, pointed out the likely lack of schooling. As the conversation unfolded, the teacher gave much emphasis to the question of schooling. In the exchange below, they were discussing the rights listed as part of the given on the spread.

Excerpt 13Fadi: All children have the right to education in schools.Teacher: Exactly. / ... /I know you think you are obliged to go to school and you must go to school, and it’s something you just have to [making disgusted sounds]. But, looking at it from the other side, you actually have the right to go to school. It is your right. I have told you before that I have worked in schools where the children never wanted school to end. [telling the students about teaching experience in another country] / ... / They said please just another hour. Because they have a completely different reality than you.

Using evaluative resources of language (“obliged,” “right,” “please just another hour”) the teacher repeatedly expressed the presumption that the students would themselves not view it as part of their rights to go to school. Instead of taking the given part of the message as an agreed-upon point of departure, the teacher underscored the right to schooling and put it in contrast to the students’ presumed attitudes.

Concluding the discussion, the teacher asked the students what they could say about the spread if they “slammed it all together.” Now, as shown in the excerpt below, both parts of the message were touched upon.

Excerpt 14Stefan: Children’s rights.Teacher: Children’s rights. Yes. Something more?Student: The Convention of the Right of the Child. / ... /Teacher: Right. And then, we get some information too about children struggling in the world. Right? Because it’s like / ... / They are soldiers. They work in the world. Working instead of going to school and so on.

In this exchange, the rights described in the convention, presented as given but reinforced by the teacher, are implicitly contrasted with the actual living conditions of children in different parts of the world, presented as new.

Negotiating meaning perspectives relating to living conditions

Both spreads negotiated in this section concern living conditions: different reasons for people travelling between countries and different living conditions for children. As the analysis has shown, the organization of the multimodal message in terms of given and new is important in conveying these differences. Furthermore, and in contrast to the spread “Our globe must be enough for everyone,” the communication around these spreads clearly pointed to the tension between given and new parts of the message.

On the spread “Near to the world,” a privileged life providing opportunities for pleasure trips and “new impressions” is contrasted with refugees moving between countries out of necessity. As has previously been pointed out, this was reconstructed by both the teacher’s foreshadowing of what to expect and later remarks on the images. Also, the information flow was highlighted by a summarizing contribution by a student (Excerpt 9). In the interaction based on this spread, the teacher and students were clearly oriented towards comparing the meanings offered on the pages of the spread. While both the students and the teacher localized the children presented on images as part of the new (“refugee camp ... a boy from Somalia,” Excerpt 10), this was not the case with the vacationing children presented as given. This can possibly be attributed to its status as part of the given: not needing any elaboration, showing life as the students are expected to know it.

Aside from pointing out different skin colors, the teacher sparsely commented on the image of the children in the spread “Children in the world” constituting given information as well as the ideal representation of the real rights described thereunder (). The harmonious diversity represented by this latter image—showing the children holding each other’s shoulders—marks a contrast to the starker images of child labor and child soldiers, which, unlike the picture presented as given, have captions localizing the depicted children in the Philippines and China respectively. These images were extensively elaborated on by the teacher, unlike the more positive representation of an African girl playing guitar which could have been used to nuance the discussion of children’s living conditions around the world.

As with the spread entitled “Near to the world,” the images on the spread “Children in the world” play an important part in conveying a tension between given and new information. The lack of geographic information related to the given images on both spreads make them all the more likely to be interpreted as depicting felicitous living conditions in Sweden, in comparison to a less privileged life in other countries. Therefore, the layout on both spreads reinforces the Western-centric view of a divided world.

Instead of elaborating on the page presented as given in the spread “Children in the world,” the teacher referred to how the students’ presumed attitudes to schooling differ from those of children in other countries. When the teacher ascribed the students a shared set of experiences (“a completely different reality”) and a certain outlook on school (“you think you are obliged”), she set up a clear role for the students as privileged Swedish citizens (Excerpt 13). In this presumption of homogeneity, the opportunity was untapped to challenge a dominant meaning perspective by inviting the linguistically diverse students’ various beliefs and experiences.

Discussion and implications

The result shows that the layout of textbook spreads, and the way in which they are negotiated in interaction, can play a role in perpetuating dominant meaning perspectives as part of the existing social order. In this study, the information flow between given and new in the spreads was conducive to the representation of a divided world, conforming to the Western-centric views pointed out in previous research. Also, the issue of environmental change was framed anthropocentrically and as a matter of consumer responsibility, in accordance with neoliberalist discourse. Suggestions of ways of becoming an “environmental hero” invokes the construction of the “eco-certified child” noted by Ideland (Citation2019).

The studied interaction, in which different text elements in the spread were highlighted, shows how these meaning perspectives were perpetuated in the discursive practice of teaching, as the teacher and the students emphasized and reinforced what was presented as given and new on the textbook spreads. This included viewing the world as divided and learning about saving the environment according to individualistic and anthropocentric meaning perspectives. While earlier research shown Western-centrism in teaching material (Ajagán-Lester, Citation2000; Kamali, Citation2006; Marmer et al., Citation2010; Mikander, Citation2015; Odebiyi & Sunal, Citation2020; Wilinsky, Citation1998) and highlighted teacher-candidates’ Western-centric beliefs (Hannah, Citation2017), the present study has shown how such meaning perspectives are perpetuated in on-going teaching practice. The teacher’s way of asking questions (Mehan, Citation1979; Sinclair & Coulthard, Citation1975) and using evaluative resources of language (Martin & White, Citation2005; Walldén, Citation2020b) was key in pointing out and reinforcing these meaning perspectives.

However, the approach taken in this study to the analysis of multimodal readings of textbook spreads also shows potentials for challenging dominant meaning perspectives. Positioning the students to consider tensions between the meanings offered as given and new—achieved by the participant teacher in the present study by drawing attention to different text elements—could be a first step towards critical literacy practices, in which the presentation of given and new information can be challenged or transformed (cf. Andreotti, Citation2006; Janks, Citation2010). Although particularly foregrounded by the participant teacher in this study, drawing students’ attention to text elements such as headings, images and captions on textbooks spread are likely quite common teaching strategies which could be used more consciously and critically with knowledge about typical information structure on textbook spreads. As such, the present study contributes to the field by highlighting a possible pedagogical application of social semiotic perspectives on textbooks, in particular layout, to probe the “sense of difference” infusing social studies textbooks (cf. Wilinsky, Citation1998, p. 154).

Based on this limited study, I cannot conclude that it would always prove fruitful to pay attention to the information flow between given and new in textbooks. However, I believe that knowledge about how multimodal texts tend to place something assumed to be known in relation to something new can be a valuable tool for objectifying texts in social studies to show how the information flow work in naturalizing ways. The principle of information flow in layouts is likely easier to grasp than many of the other complex considerations which, from a social semiotic perspective, come into play in verbal and visual communication. The results also indicate that attention to that which is presumed to be given and new can also be a way to avoid the uncritical transmission of monocultural perspectives in diverse student groups (cf. Cummins, Citation2017; García & Seltzer, Citation2016; Walldén, Citation2021). While it is not necessary to see all instances of Western-centrism apparent in the textbook and perpetuated in teaching as problematic, presumptions of student perspectives and prior experience can be particularly important to question.

An important way to promote additional meaning perspectives would be to encourage the students to contribute more of their previous knowledge and experiences, something not evident in the studied teaching. The diversity present in student groups with migrant language learners is an important resource for expanding ways of viewing the world for both teachers and students, as part of jointly created and negotiated critical literacy practices. By highlighting the transmission and possible resistance of dominant, colonial meaning perspectives in light of textbook information flow, I have shown possible pathways to enacting such practices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Robert Walldén

Robert Walldén is an Associate Professor at Malmö University, Sweden. His research interests include disciplinary literacies and knowledge-building interaction in L2 education. An important aim is to shed light on possibilities for promoting students’ awareness of texts and language to move between content-area discourses and looking at them critically.

References

- Ajagán-Lester, L. (2000). “De Andra”: Afrikaner i svenska pedagogiska texter (1768-1965) [“The Others”: Africans in Swedish pedagogical texts (1768–1965)]. Stockholms Universitet.

- Alvesson, M., & Sköldberg, K. (2008). Tolkning och reflektion: Vetenskapsfilosofi och kvalitativ metod [Interpretation and reflection: Philosophy of science and qualitative methods] (2nd ed.). Studentlitteratur.

- Andreotti, V. (2006). Soft versus critical global citizenship education. Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, 3(3), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137324665_2

- Bezemer, J., & Kress, G. (2008). Writing in multimodal texts: A social semiotic account of designs for learning. Written Communication, 25(2), 166–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088307313177

- Bezemer, J., & Kress, G. (2016). Multimodality, learning and communication: A social semiotic frame. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315687537

- Christie, F., & Derewianka, B. (2010). School discourse: Learning to write across the years of schooling. Continuum.

- Cummins, J. (2000). Language, power, and pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. Multilingual Matters.

- Cummins, J. (2017). Flerspråkiga elever: Effektiv undervisning i en utmanande tid [Multilingual students: Effective teaching in a challenging era]. Natur & Kultur.

- Fairclough, N. (2015). Language and power (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Fangen, K. (2005). Deltagande observation [Participant observation]. Liber AB.

- Feng, W. D. (2019). Infusing moral education into English language teaching: An ontogenetic analysis of social values in EFL textbooks in Hong Kong. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 40(4), 458–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2017.1356806

- Freire, P., & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy: Reading the word and the world. Routledge.

- García, O., & Seltzer, K. (2016). The translanguaging current in language education. In B. Kindenberg (Ed.), Flerspråkighet som resurs. Symposium 2015 [Multilingualism as a resource. Symposium 2015] (pp. 19–30). Liber.

- Gear, A. (2008/2015). Att läsa faktatexter: Undervisning i kritisk och reflekterande läsning [Reading factual texts: Teaching critical and reflective reading]. Natur & Kultur.

- Gee, J. P. (2014). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Halagao, P. E. (2010). Liberating Filipino Americans through decolonizing curriculum. Race Ethnicity and Education, 13(4), 495–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2010.492132

- Halliday, M. A. K., & Martin, J. R. (1993). Writing science: Literacy and discursive power. Routledge.

- Hannah, K. (2017). Images of Africa: A case study of pre-service candidates’ perceptions of teaching Africa. Journal of International Social Studies, 7(1), 34–54. https://www.iajiss.org/index.php/iajiss/article/view/285/255

- Hickling-Hudson, A. (2006). Cultural complexity, postcolonial perspectives, and educational change: Challenges for comparative education. Review of Education, 52, 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-005-5592-4

- Ideland, M. (2019). The eco-certified child: Citizenship and education for sustainability and environment. Palgrave Pivot.

- Janks, H. (2010). Literacy and power. Routledge.

- Kamali, M. (2006). Skolböcker och kognitiv andrafiering [Textbooks and cognitive othering]. In L. Sawyer & M. Kamali (Eds.), Utbildningens dilemma: Demokratiska ideal och andrafierande praxis [The dilemma of education: Democratic ideals and othering practices]. SOU 2006:40 (Vol. 40, pp. 47–102). Fritzes.

- Kopnina, H., & Cherniak, B. (2016). Neoliberalism and justice in education for sustainable development: A call for inclusive pluralism. Environmental Education Research, 22(6), 827–841. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1149550

- Kress, G. (2003). Literacy in the new media age. Routledge.

- Kress, G. (2014). What is mode? In C. Jewitt (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis (2nd ed., pp. 60–75). Routledge.

- Kress, G., & van Leuween, T. (1996/2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. Routledge.

- Langer, J. A. (2011). Envisioning knowledge: Building literacy in the academic disciplines. Teachers College Press.

- Lloro-Bidart, T. (2017). Neoliberal and disciplinary environmentality and ‘sustainable seafood’ consumption: Storying environmentally responsible action. Environmental Education Research, 23(8), 1182–1199. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2015.1105198

- Luke, A., & Freebody, P. (1999). Further notes on the four resources model. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a916/0ce3d5e75744de3d0ddacfaf6861fe928b9e.pdf

- Macken-Horarik, M. (1998). Exploring the requirements of critical school literacy: A view from two classrooms. In F. Christie & R. Misson (Eds.), Literacy and schooling (pp. 74–103). Routledge.

- Macnaught, L., Maton, K., Martin, J. R., & Matruglio, E. (2013). Jointly constructing semantic waves: Implications for teacher training. Linguistics and Education, 24(1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2012.11.008

- Marmer, E., Marmer, D., Hitomi, L., & Sow, P. (2010). Racism and the image of Africa in German schools and textbooks. The International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities and Nations, 10(5), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9532/CGP/v10i05/38927

- Martin, J. R., & Rose, D. (2007). Working with discourse: Meaning beyond the clause. Continuum.

- Martin, J. R., & Rose, D. (2008). Genre relations: Mapping culture. Equinox.

- Martin, J. R., & White, P. R. R. (2005). The language of evaluation: Appraisal in English. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mehan, H. (1979). Learning lessons. Harvard University Press.

- Mezirow, J. (1990). How critical reflections triggers transformative learning. In J. Mezirow (Ed.), Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: A guide to transformative and emancipatory learning (pp. 1–20). Jossey-Bass.

- Mikander, P. (2015). Colonialist “discoveries” in Finnish school textbooks. Nordidactica: Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, 4, 48–65. https://journals.lub.lu.se/nordidactica/article/view/19014/17207

- Miller-Lane, J., Howard, T. C., & Halagao, P. E. (2007). Civic multicultural competence: Searching for common ground in democratic education. Theory and Research in Social Education, 35(4), 551–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2007.10473350

- Odebiyi, O. M., & Sunal, C. S. (2020). A global perspective? Framing analysis of U.S. textbooks’ discussion of Nigeria. The Journal of Social Studies Research, 44(2), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssr.2020.01.002

- Pashby, K., & Andreotti, V. D. O. (2015). Critical global citizenship in theory and practice: Rationales and approaches for an emerging agenda. In J. Harshman, T. Augustine, & M. Merryfield (Eds.), Research in global citizenship education (pp. 9–13). Information Age Publishing.

- Selander, S., & Danielsson, K. (2014). Se texten! Multimodala texter i ämnesdidaktiskt arbete [See the text! Multimodal texts in working with pedagogical content knowledge]. Gleerups Utbildning.

- Sinclair, J., & Coulthard, M. (Eds.). (1975). Towards an analysis of discourse. Oxford University Press.

- Stålnacke, A.-L. (2012). Puls samhällskunskap grundbok [Pulse civics main textbook]. Natur & Kultur.

- Street, B. (1984). Literacy in theory and practice (Vol. 9). Cambridge University Press.

- Swedish Research Council. (2017) . God forskningssed [Responsible conduct in research]. Vetenskapsrådet.

- Thomas, G. (2011). A typology for the case study in social science following a review of definition, discourse, and structure. Qualitative Inquiry, 17(6), 511–521. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800411409884

- Walldén, R. (2019). Scaffolding or side-tracking? The role of knowledge about language in content instruction. Linguistics and Education, 54, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2019.100760

- Walldén, R. (2020a). Interconnected literacy practices: Exploring work with literature in adult second language education. European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults, 11(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.3384/rela.2000-7426.rela9202

- Walldén, R. (2020b). Communicating metaknowledge to L2 learners: A fragile scaffold for participation in subject-related discourse? L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 20, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.17239/L1ESLL-2020.20.01.16

- Walldén, R. (2021). “You know, the world is pretty unfair” – Meaning perspectives in teaching social studies to migrant language learners. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 66(1), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1869073

- Wilinsky, J. (1998). Learning to divide the world: Education at empire’s end. University of Minnesota Press.