ABSTRACT

Eating behaviors have been investigated for many years. The current research sheds light on the relationship between external (EXT), restrained (RES), emotional (EMO), and attitude toward Turkish cuisine (At_TC) in terms of foreign residents. A survey was conducted on foreign residents living in Turkey, by examining the extent to which Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) constructs (EXT, RES, EMO) of At_TC can be predicted by utilizing a partial least square algorithm. Results show significant relationship between EMO, EXT and At-TC whereas RES is a non-significant predictor. Further, results of comparison of eating behaviors in two separate environments (home country and Turkey) indicate certain similarities and differences. Various suggestions for future research are also made and practical implications for business owners and administrators are recommended.

Introduction

Nutrition, a basic need of a human being, is the consumption and processing of food for growth, health, and survival. Satisfying this need in the most appropriate way reassures satisfying other essential needs (Ermiş et al., Citation2015; Gürman, Citation2000). Thus, one should prefer and consume the right type of food to maintain good nutrition and a healthy lifestyle. What a person prefers to eat is the result of a complex process which is affected by various genetic, psychological, economic, social, and cultural factors. However, a number of internal and external factors are likely to influence individuals’ food choices (Glanz et al., Citation1998; Torres & Nowson, Citation2007).

Exploring and experiencing a country’s culinary culture is among the goals of gastronomic tourism, both for visitors and locals (Germann, Citation2007). Given the features of strengthening interpersonal communication and giving pleasure to individuals, eating becomes one of the focal points for touristic activities of visitors (Henderson, Citation2009; Mak et al., Citation2013; Smith & Xiao, Citation2008). On the other hand, the previous studies on eating behaviors in Turkey generally have focused on students (Kargar Mohammadınazhad, Citation2011; Kurt, Citation2014), teenagers, athletes (Coşkun, Citation2011), and military personnel (Ulaş, Citation2008). Besides, the research on the consumption of Turkish food in recent years has generally focused on the tourists (Akgöl, Citation2012; Albayrak, Citation2013; e.g., Arslan, Citation2010), considering the fact that local foods are an important tool in destination marketing for the tourism industry (Cohen & Avieli, Citation2004; I. Lee & Arcodia, Citation2011). It is an appropriate approach because Turkey has become one of the destinations that attracts the most visitors in the world (WTTC, Citation2019).

Turkey has become a preferred destination where international tourists reside. For example, according to the latest data, 6,168 foreigners reside in Kuşadası, a resort destination, with various purposes (Işık, Citation2019). By leaving the place, for whatever reason, where people have lived, migrating in other words, creates multinational countries where people from different ethnic backgrounds live together (Berry, Citation2009). Naturally, relocation also concerns the food culture of these people. Migration and food are two separate phenomena, but interestingly can establish a multi-layered relationship. Food therefore plays a key role in the adaptation of the foreigners who migrate to a country (Usunier, Citation1999; Vuddamalay, Citation2018). However, the important attitudes toward a given cuisine in the context of foreign residents have not been fully investigated.

The present research therefore aims to fill this gap in the literature by examining eating behaviors of foreign residents living in Turkey through focusing on attitudes toward Turkish cuisine. Furthermore, it is attempted to reveal if the foreign residents exhibit different eating behaviors when they are in Turkey and when they are in their home countries. As an emerging market, Turkey has become as an important destination, and thereby it seems worth investigating the eating behaviors of foreign residents in order to meet their needs, expectations and desires. Therefore, this exploratory study examining the attitudes toward Turkish cuisine, along with eating behaviors of foreign residents, could yield useful information for business strategies. Furthermore, the research may provide insight to researchers working in the field of tourism and hospitality industry.

The contributions of the current research are twofold. First, unlike previous studies, this examination can be considered the first research in the field of tourism and hospitality literature, as it examines the attitude of foreign residents toward Turkish cuisine, and compares two separate groups (home country and immigrated country). Secondly, unlike past research, this study reveals some differences and similarities associated with eating behavior by comparing the behaviors in two separate environments – home country and Turkey. Hence, it can be argued that the findings could lead to a new research avenue for various disciplines such as nutrition and sociology.

Theoretical framework

Eating behaviors caused by the effects of psychological factors, food selection, and consumption are closely related. The effects of psychological factors are important in terms of causing differences between individuals in food selection and consumption, even if they have a similar socio-cultural or economic condition. Researchers have put forward various psychological theories to explain these differences in eating behavior. These theories include Psychosomatic theory (Bruch, Citation1973; Kaplan & Kaplan, Citation1957), Externality theory (Schachter,Citation1968; Schachter & Rodin, Citation1974), and Restrained theory (Herman & Mack, Citation1975) (Konttinen, Citation2012).

The Psychosomatic theory suggests that individuals with emotional eating behavior do not have enough awareness of their emotions and the ability to recognize affect (Ouwens et al., Citation2003). According to the theory, overeating behavior is associated with a false perception of hunger. Within the scope of this theory, individuals can neither understand their hunger nor satiety. They eat not in response to internal stimuli such as appetite or feelings of hunger and satiety, but in response to their emotions. Therefore, since these individuals do not have the correct internal programming impulse regarding hunger awareness, they need some external signals to understand when and how much they are supposed to eat (Canetti et al., Citation2002). Schachter (Citation1968) proposed the Externality theory to better explain and test the Psychosomatic theory.

Unlike the emphasis on emotional and internal factors in Psychosomatic theory, Schachter’s Externality theory considers external stimuli as the determinant of eating behavior. In this theory, just as in the psychosomatic theory, individuals are not sensitive to their own internal hunger and satiety. However, the most crucial difference that separates this theory from the Psychosomatic theory is related to the reason for eating behavior. According to the theory, the food perception of individuals with an external eating attitude exists only when they are in the same environment with the food. Individuals eat excessively because they are affected by the characteristics of food, such as smell or appearance. In other cases, a food-oriented perception is not dominant (Van Strien et al., Citation1995).

On the other hand, the difficulty of verifying the Externality theory, in some cases, played an important role in the emergence of the Restrained theory. The theory was introduced by Herman and Mack (Citation1975) and developed by Herman and Polivy (Citation1980). According to Herman and Mack (Citation1975), individuals tend to restrict eating behaviors in some way in order to achieve the ideal image determined by society. In contrast to the Externality and Psychosomatic theory, this theory focuses on diets. According to this theory, restricting food consumption in a conscious way triggers some physiological defenses in the body. Along with the thought of restricting food consumption, the desire to eat is also activated. For this reason, excessive and intense diet can also cause emotional eating behaviors (Herman & Polivy, Citation1980).

Overall, in this study, the eating behaviors (emotional, external and restrained) of foreign residents were examined in the light of the theories of the Psychosomatic, Externality, and Restrained. The nutrition is very important for all segments of society, and is of particular importance for immigrants who live in a different culture. While immigrants exhibit the eating habits they are accustomed to before immigrating to another country, they can also change their eating habits with the migration or they can adapt to the new culture.

Emotional eating behavior

An individual’s eating motivation can be affected by many variables, such as eating frequency, food amount, food choice, or physiological needs (Desmet & Schifferstein, Citation2008). Emotions, one of these variables, are suggested to have a strong effect on food choice and eating behavior (Levitan & Davis, Citation2010). There are different opinions on how emotions affect eating behaviors. For example, in a study examining to what extent negative moods are related to high food intake, it was found that sad mood triggers food intake more than happiness (Evers et al., Citation2013). In another study conducted on healthy individuals, it was determined that positive emotions are effective in triggering food intake (Racine et al., Citation2013). Positive mood is generally associated with the basic needs of the individual (security, love, social belonging). Effective emotional management deals with ability to recognize needs, desire to increase knowledge, openness to new experiences), and the ability to adapt to the environment (networking, positive attitudes, and behaviors). In the category of positive emotions are happiness, gratitude, joy, enthusiasm, pride, optimism, and a healthy life. Negative emotions include sadness, discouragement, disappointment, anger, unhappiness, depression, regret, despair, loneliness, guilt, pain, anger, shame, disgust, jealousy, fear, anxiety, worry, stress, and panic (Andrieş, Citation2011). So experiencing various moods and eating behaviors according to a particular emotion may cause less food consumption when one feels stronger emotions such as tension or fear compared to distress or gloom (Robbins & Fray, Citation1980). This suggests that food consumption declines when one is experiencing strong emotions and increases with milder emotions.

External eating behavior

External eating behavior refers to how an individual consumes food, without feeling hunger, by responding to food-related stimuli. This type of nutrition emerges as a result of the willingness for the features such as the appearance, presentation, smell, taste, or texture of a given food. In this type of eating behavior, some individuals are more sensitive to external food stimuli than others. They eat as a result of high sensitivity to the characteristics of the food in the environment, such as smell, appearance and taste, without feeling physiological hunger (Evers et al., Citation2011). A research conducted by Evers et al. (Citation2011) reveals that external eating behavior is beyond the individual personality and is associated with feeling hungry. Therefore, it can be said that the feeling of hunger is an important factor in external eating evaluations.

Environmental factors have a great impact on eating behaviors and habits. Individuals form their own eating attitudes influenced by the eating habits of the society. Nutrition refers to neurons and features such as presentation, smell, taste or texture can increase its impression. Therefore, the eating attitude includes these perceptions and the amount of food consumption is determined by being able to resist all these temptations (Burton et al., Citation2007).

Restrained eating behavior

Eating behavior refers to tendency of the individual to restrict the food they consume (Lowe & Butryn, Citation2007; Stunkard & Wadden, Citation1990). Cognitive factors and low self-esteem are among the factors affecting food intake of those with restrictive eating behavior (Heatherton et al., Citation1989). In addition to these factors, loss of control over the food consumption of the individual may also provide a basis for this kind of behavior (De Lauzon-Guillain et al., Citation2006). Foods that are prevented or restricted from consumption can confuse the individual over time and make these foods more attractive (Ogren, Citation2008). The individual who fails to restrict his/her diet may be affected negatively in this process (Polivy et al., Citation1988). Those who exhibit this behavior constantly complain that they eat too much and try to restrict their eating behaviors to avoid becoming fat. The restriction here is not about nutrients needed during eating, but about an effort to eat less than the desired amount of food. It has been suggested that the restrained behaviors of individuals with normal weight are aimed at maintaining, rather than losing, their body weight. However, restrained eating behavior that continues for a long time, can turn into overeating attacks, after a while, by causing the restriction to disappear (Braet et al., Citation2008).

Traditions, resources, and geographical features in a given society create a dietary culture and idiosyncrasies. Nevertheless, individuals during their early life stages acquire dietary habits – determined by socio-economic, cultural, and educational practices (Açık et al., Citation2003; Sürücüoğlu & Özçelik, Citation2003). Dietary habits include the number of meals in a day, the type and amount of food taken in during the meals, buying, preparing, cooking, and presenting food (Sürücüoğlu, Citation1999). A number of different factors shape both personal and societal dietary habits and choices. These factors are: urban or rural lifestyles, geographical features of the living environment, climate, agriculture, beliefs, traditions and customs, socio-economic conditions, and knowledge of nutrition (Gül, Citation2011). It is no doubt that a healthy lifestyle is linked to choosing and consuming the right type of food. Furthermore, an individual’s dietary choices may be affected by socio-cultural, psychological, genetic, and economic factors. Additionally, food and energy intake depends upon personal differences, positive or negative, preconceived opinions about certain types of food, sensory traits, such as taste and smell, accessibility, the steps of buying and preparing, and food safety (Glanz et al., Citation1998).

Attitude

Ajzen (Citation1991) defines attitude as “the degree to which a person has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation or appraisal of the behavior in question”. Attitude is a function of a person’s salient behavioral beliefs, which represent perceived consequences or attributes of the behavior. Attitudes are the overall evaluations of the behavior by the individual (Conner & Armitage, Citation1998). If an individual has a negative attitude toward an action, he/she may be less willing to do that behavior (Cheng et al., Citation2006). The important role of attitude as a predictor of behavioral intention is well explained in research. For instance, K. Lee and Gould (Citation2012) have found attitude has a significant positive effect on participation intention.

Individuals’ perceptions of their bodies can cause healthy or unhealthy behaviors and this can affect their eating attitudes (Arslan et al., Citation2003). In addition, individuals’ eating behaviors and habits can be affected by cultural characteristics (Andersen & Yager, Citation2005). Eating is not only an activity arising from physiological needs or habits but also a behavior that has psychological and social effects. Therefore, depending on the current situation and attitudes, it also affects the energy intake, the amount and types of foods taken, and where and when to eat (French et al., Citation2012; Özgen et al., Citation2012). In this context, immigrants’ attitudes and behaviors toward their new culture, their living standards and their adaptation to the new culture is important for understanding their eating behaviors.

Culture of Turkish cuisine and perspectives of foreigners

Cultural values, livelihoods, and influences of the globalizing world play a decisive role in societies’ lifestyles. It can be argued that these effects occur at every stage of the culinary culture, from food preparation, to consumption. The tradition of space, equipment, socio-cultural, economic, and psychological status all affect an individual’s eating history (Uzel, Citation2018).

Each nation has its own culinary culture shaped according to habits. The diversity of products offered by the Central Asian and Anatolian lands, the interaction with many different cultures throughout the historical process, and the flavors developed in the Seljuk and Ottoman palace kitchens are the basis of Turkish culinary culture (Durlu Özkaya & Cömert, Citation2017; Kızıldemir et al., Citation2014). Turkish cuisine differs in terms of food types and flavors, due to the nation being a nomadic society living with different civilizations, geographical location, importance given to nutrition, and religious traditions and customs (Güler, Citation2010). Giritlioğlu (Citation2008) indicates that the materials and cooking techniques used in the production of food keep Turkish cuisine a flavor rich kitchen for centuries. The use of meat and fermented dairy products by nomads living in Central Asia, cereals in Mesopotamia, spices in South Asia, and vegetables and fruits grown around the Mediterranean, are effective in the change and development of Turkish cuisine (Gezmen Karadağ et al., Citation2014).

Food and beverages are important social factors in the culture to which they belong (Lopez-Guzman & Sanchez-Canizares, Citation2012). Therefore, the culinary customs of a group are an important consideration for understanding that culture (Aslan et al., Citation2014). Factors that involve food selection contain considerations for health, natural content, easy accessibility, sensory attraction, mood, price, weight control, and food awareness. Ethical values are explained as important factors in identifying culinary cultures (Fotopoulos et al., Citation2009; Milosevic et al., Citation2012; Prescott et al., Citation2002; Steptoe et al., Citation1995). Furthermore, motivations such as health, sensory characteristics of the food, interpersonal interaction, excitement, and cultural experience are important in local food preferences (Kim & Eves, Citation2012).

Many factors are involved in an individual’s selection of foods. Sensory appeal (such as taste and texture), visual appeal, social appeal, and psychological needs are among these (Eertmans et al., Citation2005). The individual chooses the right foods, in order to survive in a healthy way. It can be said that factors such as socio-cultural, psychological, genetics, and economy are effective in these choices. In providing the nutrients and energy needed by the body: individual characteristics, positive or negative (healthy-unhealthy), prejudices about foods, sensory appeal (e.g., taste, smell), accessibility, purchasing, preparation stages, and food safety are influencing factors (Glanz et al., Citation1998). Nutritional behavior shaped by the effect of psychological factors and food selection is closely related. In fact, even socioeconomic status of individuals belonging to the same culture can lead to an individual’s food selection and, thus, feeding habits may vary (Kozan, Citation2013).

On the other hand, eating preferences of individuals who constantly visit another place may be restricted for some reason. There may be reluctance in the consumption of new foods or meals (Raudenbush & Capiola, Citation2012). The neophobic tendency may be the cause of this reluctance. The neophobic tendency toward food means that individuals may be hesitant to try new and unknown foods, and refuse to accept them (Choe & Cho, Citation2011; Fenko et al., Citation2015; Fischler, Citation1988; Pliner & Salvy, Citation2006). According to Murcott and Van Otterloo (Citation1992), there are significant differences between personality traits and cultures along with biological and cultural effects (Cohen & Avieli, Citation2004). Applying the neophobic tendencies scale, Ritchey et al. (Citation2003) found that cultural variables may play an important role in reactions to foods. In a study by Cohen and Avieli (Citation2004), it was found that foreigners were worried about foods, because of their unfamiliar contents and how these were prepared. According to Torres (Citation2002), in general, tourists prefer the foods they are used to, and they are hesitant to try local foods. Chang et al. (Citation2010) suggest that the food culture of foreigners is influenced by neophobic tendencies.

Referring to the studies in Turkey, similar results emerged. For example, Özdemir and Kınay (Citation2004) found that foreign guests perceive some Turkish cuisine as oily, tomato pasted, and spicy, but a vast majority of the participants evaluated viewed Turkish cuisine as tasty, hygienic, attractive, easy to digest, suitable for the palate, and satisfying. Bezirgan (Citation2017), on the other hand, found out that neophobic tendencies had a significant effect on the attitudes of Japanese tourists toward Turkish cuisine. Similarly, Akyüz (Citation2017) found that local food consumption motivations are related to the tendency of neophobia and that it affects decisions to visit a place to consume local food.

Hypotheses development

Turkey, due to its crossroads location, is in a region highly affected by immigration raids. Turkey’s irregular migration since 1980, is the result of international resettling. Immigrants to Turkey, generally from Asia, Africa and Eastern Europe, come for four main reasons: those who come to work, transit migrants, asylum seekers, and regular immigrants. Migrants in these groups can change their status according to the rules and possible opportunities set by the Turkish Government (Migrant Workers Survey, Citation2015). According to the data of the Turkish Institute of Statistics, the number of people abroad who migrated to Turkey in 2018 is 577.457 (International Migration Statistics, Citation2018b). On the other hand, the migration of foreign residents falls outside the aforementioned classifications and has a close pattern with the tourism industry. Indeed, the number of foreign visitors who are settling in Turkey, as of year 2020, is rising rapidly. In fact, the years 2013–2018 showed rapid increase in the number of foreign residents, from various countries, who settled in Turkey and that number has reached nearly 1 million two hundred thousand (TUİK, Citation2018a). Although there are some studies on foreign residents, these examinations mostly addressed the profiles of the participants, their arrival goals, and some other issues. For example, Özgürel and Avcıkurt (Citation2018) focused on the impacts of foreign residents on the Turkish tourism industry, Yirik et al. (Citation2015) investigated socio-cultural perceptions by their demographic characteristics. A recent study by Yıldız and Sertoğlu (Citation2019) has attempted to examine the perceptions of Turkish language. However, to date, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is no study addressing the attitudes of foreign residents toward Turkish food.

Given that moods affect eating behaviors, previous exposure to the foods of a culture has much to do with attitude toward a cuisine (Dallman et al., Citation2003; Oliver et al., Citation2000; Robbins & Fray, Citation1980). This suggests that food choice may also be linked to experience with a foreign culture. Indeed, people immigrated to Turkey for various reasons, in a particular period of the year or throughout the year. Hence, emotions should be considered in their attitudes toward Turkish cuisine. Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that:

H1 – Emotional eating behavior will have a significant impact on attitude toward Turkish cuisine.

The restrained eating behavior, which is expressed as a tendency to restrict food consumed for kilos control refers to controlling food consumption (Stunkard & Wadden, Citation1990). Given the daily routine of foreign residents, when they are experiencing a different culture, it can be argued that they are likely to consume much food during an emotional period filled with the difficulties of adaptation to a different culture (e.g., language, education of kids, work environment). The reason for over consuming could be the result of a lack of stress relief not offered by the presence of sport facilities in the area. This may likely be related to difficulty in food consumption control. Therefore, it should not be assumed that foreign residents consume too much because they like Turkish cuisine. Thus, the second hypothesis to be tested in the present study is:

H2 – Restrained eating behavior will have a significant impact on attitude toward Turkish cuisine.

The external eating behavior is viewed only when individuals are in an environment with food. Being in the same environment with something to eat triggers reactions to foods. Otherwise, a food-oriented perception is rarely seen (Van Strien et al., Citation1995). External eating behavior is thus seen when an individual cannot resist external stimuli (Burton et al., Citation2007; Elfhag & Morey, Citation2008). Evers et al. (Citation2011) suggest that this increases the influence when an individual is feeling hungry. Furthermore, this is evident in availability of street foods (Karsavuran, Citation2018). Therefore, considering the characteristics of Turkish foods, which have enormous sensory appeal (Birdir & Akgöl, Citation2015), it is reasonable to guess that external stimuli may be a predictor of attitude toward Turkish cuisine. It is thus hypothesized that:

H3 – External eating behavior will have a significant impact on attıtude toward Turkish cuisine.

Methodology

Survey instrument

Data conducted in 2017 on foreign residents living in Turkey were collected through a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire is comprised of three sections. The first section includes thirty-three questions, adopted from DEBQ (Van Strien et al., Citation1986) under the three sub-dimensions within the context of eating behaviors: emotional, external and restrained. A five-point Likert-type measurement gauged responses ranging from (1) never to (5) very often. The second section includes sixteen questions to clarify the possible differences in association with the eating behaviors of the participants when they were in their home country and in when they were in Turkey. The last section consists of the section on demographic characteristics of the participants.

A total of seventy questions were prepared in Turkish for those foreign residents who live in Kuşadası, and Antalya, and in English for those who do not know Turkish well. A pilot study was applied to fifteen foreign residents. Furthermore, feedback of the three tourism experts whose studies were mostly on F&B, as well as that from a nutrition and dietetic expert, was obtained. Several changes were made through the feedback from foreign residents and experts to clarify the questions and expressions that could not be understood well. Revisions in the order of the questions, the wording, and a couple of English questions simplification. The Cronbach Alpha internal consistency coefficient of the original DEBQ was reported as 0.95 (emotional), 0.81 (external), and 0.95 (restrained). In this study, the items in each dimension demonstrated adequate internal consistency; 0.86, 0.74, and 0.87, respectively.

Sampling

A self-completion survey instrument is used to collect data from foreign residents residing in Kuşadası and Antalya. Furthermore, over the years, Turkey has become an attractive country for those who intend to have long residence and a work permit. Indeed, the number of retirees who have come to live in Kuşadası and nearby regions has been increasing. Recent data, provided by the Turkish Ministry of Interior, Directorate General of Migration Administration (2019) show that with specific regard to 55 years of age and older retired foreigners, about 5,968 migrated to Aydin province. Additionally, other categories such as employee, housewife, and unemployed are 3,316 people in total.

The current study involved a nonrandom sample method – snowball sampling, due to lack of existing data and difficulty of obtaining permission from government agencies. Snowball sampling was adopted to source the foreign residents who were residing in Kuşadası. To do that, initially, several screening indicators (district, neighborhood, gated communities, the offices where they work) were identified through a draft list, obtained from the Aydin Directorate of Provincial Migration Office. Then, one of the researchers of the study visited condos and houses where foreign residents lived. The researcher requested each potential participant to refer them to another foreign resident. A total of forty-four questionnaires were collected in this step. Although the database obtained from government administrations might seem useful, the number of questionnaires remained insufficient despite all efforts. For this reason, foreigners who reside in Antalya, a resort destination in Turkey intensely preferred by immigrants, were considered as being another target population to collect further data. The questionnaires were distributed with the help of non-governmental organizations (e.g., Animal Friends Association, Antalya Animal Volunteers Society). Participants were given fifteen days to complete the questionnaires. At the end of this period, the questionnaires were collected and the answers were checked. Thirty-six questionnaires with incomplete information were excluded from the analysis. In total, the researchers collected a nonrandom sample of two hundred and fourteen foreign residents who had migrated to Turkey (Kuşadası and Antalya). Data were collected during the spring in 2017.

Given the demographic and residency characteristics of the foreign residents (), 57.5% of the participants were female and 42.5% were male. Age profile indicated that the vast majority of them were aged over 30 (72.8%). Marital status was distributed almost equally. The largest proportion belonged to the group with upper college degrees. Of the 214 foreign residents, the Germans were the majority (18.2%), followed by the Russians (19.2%), Ukrainians (13.1%), and the British (7.5%), while 42% of the participants are from other nations: (American, Australian, Austrian, Azerbaijani, Belarussian, Belgian, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Canadian, Chinese, Cypriots, Danish, French, Ghanaian, Greek, Hungarian, Iranian, Japan, Kenyan, Libyan, Moldovan, Polish, Romanian, Scottish, Serbian, Slovak, South African, Spanish, Swiss, Syrian, Uzbek). Finally, in terms of levels of income in Turkey, the frequencies included both countries, country of origin and Turkey, and figures indicated that they became included in the relatively high-income groups after starting to live in Turkey.

Table 1. Sample profile (n:214)

Data analysis

SPSS 22.0 was used for analyzing descriptive and difference statistics, and the SmartPLS v.3.2.6 package was used to examine the outer and inner models (Christian M. Ringle et al., Citation2015) based on partial least squares (PLS). Recently, it is seen that the PLS-SEM approach has become widely preferred in many disciplines (C.M. Ringle et al., Citation2018). There are several reasons why the PLS algorithm is preferred in this study. First, the research attempted testing eating behavior of foreign residents from a solely prediction perspective. Second, the research data did not meet the normal distribution assumptions sufficiently. Third, the data were collected from a small population (Hair, Risher et al., Citation2019) through non-probabilistic sampling – snowball. However, the normality of the data was checked before analysis. Skewness and kurtosis of the dataset were ranged from −0.229 to 0.926 and −0.994 to 0.713, respectively. No data exceeded the cutoff value of 3 as suggested by Kline (Citation2015). Considering the reasons for using PLS (Hair, Sarstedt et al., Citation2019), it can be said that these factors may make sense.

Questionnaires in which data are collected from a single source may lead to a common method bias (CMB) (Ali, Citation2016). Harman single factor test (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003) was used to determine whether there was such a bias in the dataset. Given the total variance, the largest variance explained by third factor was 14.767% in the dataset. It is less than suggested cutoff value by 50%. Therefore, it can be argued that CMB is not a problem for this study. Furthermore, missing data were examined through replacing with series mean.

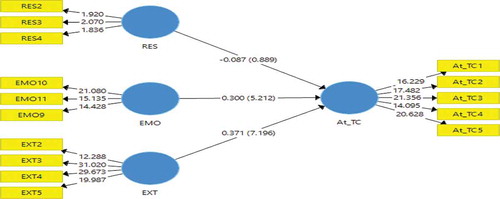

Outer model assessment (measurement model)

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to identify four constructs (emotional, external, restrained, and attitude to Turkish cuisine) in the structural model. The constructs related to DEBQ can be defined as reflective since “the relationship progresses from construct to indicators, suggesting that indicators are correlated” (Do Valle & Assaker, Citation2016).

The outer model was examined to assess the convergent validity through item loadings, Average Variance Extracted (AVE), heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT), Composite Reliability (CR), pA, and Cronbach’s alpha (Hair et al., Citation2019b). Item loadings exceeded the cutoff value of 0.708, ranged from 0.725 to 0.920. The items with low values have been excluded from the model. Cronbach’s alpha (above of 0.70), AVE (greater than 0.50), pA (passed the cutoff value of 0.70), and composite reliability values (not below of 0.70, ranged from 0.865 to 0.889) were examined to assess internal consistency. Therefore, the results were considered satisfactory for the outer model (Hair, Sarstedt et al., Citation2019) ().

Table 2. Results of convergent validity

Given the discriminant validity, “which is the extent to which a construct is empirically distinct from other constructs in the structural model” (Hair et al., Citation2019a), HTMT analysis, which has recently introduced (Henseler et al., Citation2015), was used. Hair et al. (Citation2019a) suggest that HTMT is more suitable for discriminant validity assessment. The results show that all constructs in the model were below the .90 threshold as suggested by Henseler et al. (Citation2015). shows the HTMT results.

Table 3. Results of discriminant validity (HTMT)

Inner model assessment (structural model)

Hair et al. (Citation2019b) suggest that the coefficient of determination (R2), the blindfolding-based cross validated redundancy measure Q2, and the statistical significance and relevance of the path coefficients need to be examined when assessing the inner model. To do that the bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 subsamples was used.

Hair et al. (Citation2019b) emphasis that “before assessing the structural relationships, collinearity must be examined to make sure it does not bias the regression results”. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), recommended threshold is 3 and lower (J. F. Hair et al., Citation2017) was used to assess this issue. The result indicates that () both VIF values (inner and outer) were in the range of 3–5.

Table 4. VIF results

Hair et al. (Citation2019a) suggest that after assessing the collinearity issue, the R2 value of the endogenous construct(s) can be examined. The R values of 0.75, 0.50 and 0.25 can be considered substantial, moderate and weak (Henseler et al., Citation2009). The three exogenous constructs (emotional, external and restrained) in the inner model explained the variance in attitude toward Turkish cuisine with the R2 value of 0.18. Therefore, it can be argued that it is a weak model. However, this value may be regarded as sufficient since there has yet been no consensus on cutoff points in the field of tourism and hospitality. R2 values are content-based, and in some disciplines, this value as low as 0.10 can be considered sufficient (Raithel et al., Citation2012).

The assessment of the effect size in the structural model was made using f2 value as suggested by Hair et al. (Citation2019b). The effect size (f2) calculates the effect of predictors on endogenous construct’s R2 value when there is removal of a given predictor construct in the model (Hair et al., Citation2019b). Effect ranges of f2 values were classified as small (0.02), medium (0.15), and high (0.35) (J. Cohen, Citation1988). In this study, it was found that the external has a medium effect size, and the other two constructs (emotional and restrained) have a small effect. Furthermore, the blindfolding procedure by means of Stone–Geisser’s Q2 was used to assess the PLS path model’s predictive accuracy. The Q2 replaces the single points, earlier removed, with the mean in the matrix and, thereby, estimates the model parameters (Sarstedt et al., Citation2017). If the Q2 value be higher than zero, it indicates predictive accuracy of the model, but as a guideline, in a given PLS-path model; zero, 0.25 and 0.50 show small, medium and large predictive relevance (Hair et al., Citation2019b). The path model’s predictive accuracy analysis yielded a satisfactory result, exceeding minimum value of zero (Q2 = 0.091); thus, the structural model can be considered have had a sufficient predictive relevance. PLS Predict (out-of-sample prediction) was also used to assess the predictive power of the model. The root mean squared error (RMSE), and the mean absolute error (MAE) were utilized to make comparisons to linear regression model (LM) (k: 10; number of repetitions: 10) as suggested by Hair et al. (Citation2019b). depicts that the Q2Predict values were positive and all indicators of the endogenous in the PLS-SEM analysis yielded higher prediction errors compared to the naïve LM benchmark construct. So it can be said that the model had medium predictive power.

Table 5. PLS predict results

Given the assessment of model fit, the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) value was used (Henseler, Citation2017). The SRMR value (0.087) was at the limit of the threshold value (0.08). Though it should be below the given cutoff value, it may be tolerated, considering other measurements and structural procedures fit recommended values.

Finally, the statistical significance and relevance of the path coefficients in the structural model were used to assess the structural paths between exogenous and endogenous variables ().

Table 6. Structural model results

Out of three exogenous variables, two variables (emotional and external) had a positive significant influence on attitude toward Turkish cuisine, thereby hypothesis 1 and 2 supported, whereas restrained was a non-significant predictor of endogenous variable; thus, H3 was not supported ().

Comparisons of eating behavior characteristics in home country and Turkey

In another phase of the study, it was also attempted to compare two separate eating characteristics by their home country and while in Turkey (see ).

Table 7. Comparison of foreign residents’ eating behaviors in their home country and Turkey

As can be seen in , the participants eat out less often. They go shopping for food and cook at home more often in Turkey, compared to their shopping and cooking habits in their home country. There also appears an increase in the number of meals they eat when they are in Turkey. On the other hand, it is seen that the types of dishes and ingredients (grains, meat, seafood, plants, etc.) change slightly. Besides, it is deduced that participants try to preserve their culinary habits and cooking styles, and tend to eat as they are used to doing in their country of origin. Finally, the participants, who stick to their diets and exercise programs, due to the risk of excessive calorie intake, are observed to consume fewer snacks in Turkey.

This study also examines the influence of religious beliefs and deduces that beliefs affect the eating behaviors of foreign residents in Turkey. Hatipoğlu (Citation2010) conducted a study on this subject and found that tourists were well aware of visiting a country where Islam is practiced by the majority of the population, so they did not demand pork or pork-based products in Turkey. This finding suggests that foreign residents may specify their eating behaviors according to the culinary traditions of the country they are visiting. This is consistent with the results of a study undertaken by Bekar and Kılıç (Citation2014). They have found that 37.7% of the tourists in Turkey prefer particular restaurants, where food is prepared and served in compliance with their religious practices.

Conclusions and discussion

This study aimed to examine three eating behaviors (external, restrained and emotional) of the foreign residents by focusing on attitudes toward Turkish cuisine in the light of the Psychosomatic theory, the Externality theory and the Restrained theory. Besides, it was attempted to reveal whether or not the foreign residents exhibit different eating behaviors when they are in Turkey and in their home countries.

The study presents four main conclusions. First, the strongest predictor of attitude toward Turkish cuisine was external eating behavior (H3). This may be explained by the Externality theory. Theoretically, individuals are not sensitive to their own internal hunger and satiety. Individuals overeat because they are affected by the characteristics of food such as smell or appearance, and in other situations a food-oriented perception is not dominant (Van Strien et al., Citation1995). In another words, regardless of how hungry people are, they are inclined to respond to external stimuli, such as smell, taste and appearance. A number of different factors can affect the participants’ food preferences. For example, individual might want to explore new dishes when they enter a new culture (Çakıroğlu & Sargın, Citation2004; Ting et al., Citation2016). Zağralı and Akbaba (Citation2015) suggest that tourists, rather than being mere observers and relying solely on their sense of sight, partake in traveling experiences, while using more than one sense. Gastronomy tourism thus helps tourists to learn about a particular culinary heritage, to reflect cultural identities, and to present local dishes to a wider audience (Çalışkan, Citation2013; E. Cohen, Citation2004; Richards, Citation2001). As a result, in this study, the foreign residents are exposed to socially shaped eating habits; hence, it can be argued that these may influence their external eating behaviors.

Secondly, the participants exhibit emotional eating behaviors to a certain degree (H1). This result could be because of the moods affect eating behaviors, and it can be explained as exposure to a culture’s food has a lot to do with an attitude toward a new cuisine (Dallman et al., Citation2003; Oliver et al., Citation2000). In this study, emotions, as the second strongest predictor of attitude, are suggested to have a strong effect on food choice and eating behavior (Levitan & Davis, Citation2010). According to the Psychosomatic theory, those with emotional eating behavior cannot understand their emotions adequately and do not have the ability to recognize affect (Ouwens et al., Citation2003). So, positive and negative emotions play an important role in this complex process (Evers et al., Citation2013; Racine et al., Citation2013; Robbins & Fray, Citation1980). For example, Nawijn and Veenhoven (Citation2011) investigate, in a study conducted in Germany, the relationship between happiness and leisure time activities (e.g., going on a vacation). The study reveals that taking a vacation increases happiness. This conclusion suggests that emotional overeating behaviors are restricted by happiness, pleasure, and other positive emotions. Moreover, emotional eating behaviors may be observed more frequently under the influence of negative emotions (Yirik et al., Citation2015), as in the foreign residents in this study. Indeed, they might feel alienated, find their environment odd, have adaptation difficulties, or feel homesick. So, it can be argued that the participants may exhibit eating behaviors due to the partial influence of the culture they contact.

Third, the study concludes that the restrained eating behavior cannot predict the attitude toward Turkish cuisine (H2). The participants seemed not to tend to suppress their food intake to control their body weight. According to the Restrained theory, individuals tend to somewhat restrict their eating behavior to achieve the ideal image emphasized by the beauty norms set by society. The tendency to restrain food consumption, with the aim of body weight control, is seen to be the most common (Herman & Mack, Citation1975; Polivy & Herman, Citation1987; Stunkard & Wadden, Citation1990). However, the desire to eat takes action with the thought of restricting food consumption. For this reason, excessive and intense nutrition ingestion can also cause emotional eating behavior (Herman & Polivy, Citation1980). Therefore, the reason why the participants in this study tended toward emotional eating behavior rather than restrained eating behavior can be explained by this theory.

Fourth, the foreign residents exhibit slightly different eating behaviors when they are in Turkey. Therefore, it can be argued that the results of living in different cultures may cause the participants to feel the need to partially preserve their food culture (Raudenbush & Capiola, Citation2012). Despite some similarity of eating behaviors, it can be said that the aforementioned differences are due to neophobic tendency (Chang et al., Citation2010; Cohen & Avieli, Citation2004; Ritchey et al., Citation2003). Although eating behaviors are not adequately addressed in the literature in terms of resident foreigners, this result is consistent with some previous studies (Akyüz, Citation2017; Bezirgan, Citation2017).

Conceptual contribution

In several ways this study contributes to literature about eating behaviors. First, the research gives insight to understand the behaviors of foreign residents. In previous studies, eating attitude was generally associated with health, eating disorders, family environment, and obesity (Aikman et al., Citation2006; Çulhacık & Durat, Citation2017; Tunç, Citation2019). In this study, three eating behaviors, emerged from the theories of the Psychosomatics, Externality and Restrained, were examined in the context of the foreign residents’ attitudes toward a culinary culture. As a matter of fact, along with the factors such as language (Kulikova et al., Citation2017; Peltokorpi, Citation2010; Suutari, Citation1998; Suutari & Brewster, Citation1998), adaptation barriers (Au & Fukuda, Citation2002; Suutari & Brewster, Citation1998) and new cultural codes or intercultural barriers (Farças & Gonçalves, Citation2017; Kim, Citation2018; Lai & Yang, Citation2017), some changes may occur in the eating behavior of individuals who migrate to a new country. However, individuals may need to adapt their eating habits to the new culture, social networks, lifestyle and various eating rules. In this context, the attitudes and behaviors toward the new culture that immigrants have entered are a matter that should be considered in terms of their own living standards and adaptation to the new culture. But, research on foreign residents or expats have generally focused on marital status, job performance, age, length of stay, education, and status, considering the intercultural adaptation and adaptation process (Groves & O’Connor, Citation2018; Haak Saheem et al., Citation2019; Hincks, Citation2018; Nunes et al., Citation2017; Takeuchi et al., Citation2019; Vijayakumar & Cunninham, Citation2019). Therefore, this study, unlike previous studies, has been able to fill a gap in the literature by examining the eating behaviors of foreign residents in general, and specifically understanding the attitudes toward Turkish cuisine in particular.

Second, although examining eating behaviors has been conducted on students (Barr et al., Citation2020; Kabir et al., Citation2018; Kelly & Stephan, Citation2016; Murphy et al., Citation2019), athletes (Fortes et al., Citation2013; Gorrell et al., Citation2019; Haase, Citation2011), and patients (Becker et al., Citation2018; Kelly et al., Citation2005), this study contributes to the various fields of research (e.g., nutrition, migration sociology, social psychology) aside from tourism and hospitality. Therefore, researchers will be able to undertake cross-cultural studies in the context of foreign residents by considering the findings of this study associated with eating behavior comparisons between their home countries and Turkey.

Practical implications

Given the fact that foreign residents have an impact on the food and beverage industry in a particular country, the results of the present study can provide several managerial implications for owners and administrators in food and beverage industry. First, consumers are likely to develop a positive attitude toward a business when they are provided with nutritious, healthy food, and nutritional information on the menus (DiPietro et al., Citation2004; Eves et al., Citation1996). As foreign residents are stimulated by external stimulants, food and beverage businesses can therefore highlight the visual and olfactory appeal of the dishes, and offer healthy food for potential consumers. Further, hotels can provide restrained eaters with nutritional values and recipes of the dishes served in open buffets. The regions where the research is conducted (Kuşadası and Antalya) are the destinations where the touristic facilities operate intensively. Therefore, in the light of the results obtained from this research, hotels or restaurants in these destinations may make changes or adaptations in their menus by taking into consideration the eating attitudes of the foreign residents.

Second, this study found that there are several similarities and differences in terms of eating behaviors of participants who have been to Turkey. Therefore, considering particular differences can be helpful for local producers and grocery owners. For example, grocery stores and supermarkets may appeal to the special needs of foreign residents. In case the visitors need special food according to their age, religious beliefs, or dietary requirements, employees at food and beverage businesses, as well as grocery stores, can use appropriate communication strategies for foreign guests and customers. Since tourism appeal and revisit intentions of tourists are vital for the long-term development of tourism destinations, efforts to make visitors feel comfortable with their choices must be paramount (Bayrakçı & Akdağ, Citation2016). Furthermore, any improvements in the food and beverage industry that encourage word of mouth marketing, would be able to make long-term contributions to tourism in Turkey.

Third, consideration for people who tend to restrict their diets with concern for weight control, the presentation of foods involving organic, natural, and healthy products may reduce the negative effects of restrictive behavior on Turkish cuisine. The addition of more common or familiar spices or condiments, instead of those less known to visitors, may also facilitate the choice of these new dishes. It is also important to note that food and beverage establishments should implement new, creative and different presentation techniques that can attract more individuals, especially those who tend to restrict themselves.

Fourth, it would also be useful for food and beverage management to provide detailed information on the contents of local food in their menus for people who tend to have emotional and restrained eating behavior. In addition, it is important for those who pay attention to their diets to design clear menus with calorie calculations.

Limitations and future studies

As with any research, the current study has some limitations. First, the sample could not be selected using probabilistic sampling methods. That is the reason why snowball sampling as non-probabilistic method was used. Due to reasons mentioned earlier, it was not possible to use sufficient, reliable and up-to-date databases related to foreign residents living in Turkey. Although supports were received from NGO administrators, and one of the authors of the research attempted to collect data by participating with some of these organizations, attention should be paid to generalizing the results. Hence, future research can use randomized samples should a more updated and applicable randomized database be obtained. Second, only the attitude toward Turkish cuisine was attempted to be predicted using the DEBQ constructs. Although the attitude is known as strong predictor in terms of its actual behavior, the results should still be considered cautiously. Therefore, undertaking mixed research method designs to reveal actual eating behavior of foreign residents would likely yield more valid outcomes. Third, the proposed model is limited to measuring the relationship of external, restrained, emotional, attitude influences toward Turkish cuisine, and thus can be regarded as fairly plain model. It could be therefore attempted to predict attitude in the context of eating behavior in different cultures through adding various latent variables or constructs – e.g., risk perception, cultural differences into the model. Fourth, the foreign residents have different cultural backgrounds; thus, their eating behaviors might differ across their unique cultures. Hence, this research does not suggest that the results adequately represent the cultures of the participants. The findings of this study could lead, however, to further intercultural comparative studies. Lastly, the survey instrument was prepared solely in English and Turkish to appeal to the speakers of these two languages. The form could be translated into various languages for a wider participant range.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Note: This study is adapted from the master thesis “Eating Behaviors of Tourists and Foreign Residents in Turkey” Aydin Adnan Menderes University.

References

- Açık, Y., Çelik, G., Ozan, A. T., Oğuzöncül, A. F., Deveci, S. E., & Gülbayrak, C. (2003). Üniversite öğrencilerinin beslenme alışkanlıkları. Saglik Ve Toplum, 13(4), 74–80. https://app.trdizin.gov.tr/makale/TWpFNU16WTI/universite-ogrencilerinin-beslenme-aliskanliklari

- Aikman, S. N., Min, K. E., & Graham, D. (2006). Food attitudes, eating behavior, and the information underlying food attitudes. Appetite, 47(1), 111–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2006.02.004

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Akgöl, Y. 2012. Gastronomi turizmi ve türkiye’yi ziyaret eden yabanci turistlerin gastronomi deneyimlerinin değerlendirilmesi. Yayımlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Mersin Üniversitesi.

- Akyüz, B. G. (2017). Culinary tourism: Factors that influence local food consumption motivation and their effects on travel intentions. Yayınlanmamış Doktora Tezi, Bahçeşehir Üniversitesi.

- Albayrak, A. (2013). Farklı milletlerden turistlerin Türk mutfağına ilişkin görüşlerinin saptanması üzerine bir çalışma. Journal of Yasar University, 30(8), 5049–5506. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/179396

- Ali, F. (2016). Hotel website quality, perceived flow, customer satisfaction and purchase intention. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 7(2), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-02-2016-0010

- Andersen, A. E., & Yager, J. (2005). Eating disorders. In B. Sadock & V. Sadock(Eds.), Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. Vol. 8.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, s. 2005-2021

- Andrieş, A. M. (2011). Positive and negative emotions within the organizational context. Global Journal of Human-Social Science Research, 11(9), 15–32. https://globaljournals.org/GJHSS_Volume11/4-Positive-And-Negative-Emotions-Within-The-Organizational-Context.pdf

- Arslan, Ö. 2010. Yabancı turistlerin yiyecek içecek işletmeleri, personel ve türk mutfağına ilişkin görüşlerinin değerlendirilmesi: Alanya örneği. Yayımlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi. Eğitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Gazi Üniversitesi.

- Arslan, D., Gürtan, E., Hacım, A., Karaca, N., Şenol, E., & Yıldırım, E. (2003). Ankara’da Eryaman sağlık ocağı bölgesinde bir lisenin ikinci sınıfında okuyan kız öğrencilerin beslenme durumlarının ve bazı antropometrik ölçümlerinin değerlendirmeleri. CÜ Tip Fakültesi Dergisi, 25(2), 55–62. https://app.trdizin.gov.tr/publication/paper/detail/TWpBMU1ESXk

- Aslan, Z., Güneren, E., & Çoban, G. (2014). Destinasyon markalaşma sürecinde yöresel mutfağın rolü: Nevşehir örneği. Journal of Tourism and Gastronomy Studies, 2(4), 3–13. https://www.jotags.org/Articles/2014_vol2_issue4/2014_vol2_issue4_article1.pdf

- Au, K. Y., & Fukuda, J. (2002). Boundary spanning behaviors of expatriates. Journal of World Business, 37(4), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-9516(02)00095-0

- Barr, A., Hanson, A., & Kattelmann, K. (2020). Effect of cooking classes on healthy eating behavior among college students. Topics in Clinical Nutrition, 35(1), 62–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/TIN.0000000000000197

- Bayrakçı, S., & Akdağ, G. (2016). Yerel yemek tüketim motivasyonlarının turistlerin tekrar ziyaret eğilimlerine etkisi: Gaziantep’i ziyaret eden yerli turistler üzerine bir araştırma. Anatolia: Turizm Arastirmalari Dergisi, 27(1), 96–110.

- Becker, K. R., Fischer, S., Crosby, R. D., Engel, S. G., & Wonderlich, S. A. (2018). Dimensional analysis of emotion trajectories before and after disordered eating behaviors in a sample of women with bulimia nervosa. Psychiatry Research, 268, 490–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.008

- Bekar, A., & Kılıç, B. (2014). Turistlerin gelir düzeylerine göre destinasyondaki gastronomi turizmi etkinliklerine katılımları. Uluslararasi Sosyal Ve Ekonomik Bilimler Dergisi, 4(1), 19–26. http://www.ijses.org/index.php/ijses/article/view/124/132

- Berry, J. W. (2009). Living together in culturally-plural societies: Understanding and managing acculturation and multiculturalism. In S. Bekman & A. A. Koç (Eds.), Perspectives on Human Development, Family, and Culture (pp. 227–240). Cambridge University Press.

- Bezirgan, M. (2017). Mediation effect of food attitude between food neobhobia and destination attachment: A survey on Japanese tourist who visited Turkey. In R. Efe, R. Penkova, J. A. Wendt, K. T. Saparov, & J. G. Berdenov (Eds.), Developments in social sciences (pp. 583–593). St. Kliment Ohridski University Press.

- Birdir, K., & Akgöl, Y. (2015). Gastronomi turizmi ve türkiye’yi ziyaret eden yabancı turistlerin gastronomi deneyimlerinin değerlendirilmesi. Isletme Ve Iktisat Çalismalari Dergisi, 3(2), 57–68. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/355402

- Braet, C., Claus, L., Goossens, L., Moens, E., Van Vlierberghe, L., & Soetens, B. (2008). Differences in eating style between overweight and normal-weight youngsters. Journal of Health Psychology, 13(6), 733–743. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105308093850

- Bruch, H. (1973). Eating Disorders. Basic Books.

- Burton, P., Smit, H. J., & Lightowler, H. J. (2007). The influence of restrained and external eating patterns on overeating. Appetite, 49(1), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2007.01.007

- Çakıroğlu, P., & Sargın, Y. (2004). Küreselleşmenin gıda tüketimine etkisi (pp. 510). Standard.

- Çalışkan, O. (2013). Gastronomic identity in terms of destination competitiveness and travel motivation. Journal of Tourism and Gastronomy Studies, 1(2), 39–51. https://www.jotags.org/Articles/2013_vol1_issue2/2013_vol1_issue2_article4.pdf

- Canetti, L., Bachar, E., & Berry, E. M. (2002). Food and emotion. Behavioural Processes, 60(2), 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0376-6357(02)00082-7

- Chang, R. C. Y., Kivela, J., & Mak, A. H. N. (2010). Food preferences of Chinese tourists. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(4), 989e1011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.03.007

- Cheng, S., Lam, T., & Hsu, C. H. (2006). Negative word-of-mouth communication intention: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 30(1), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348005284269

- Choe, J. Y., & Cho, M. S. (2011). Food neophobia and willingness to try non – Traditional foods for Koreans. Food Quality and Preference, 22(7), 671–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2011.05.002

- Cohen, E. (2004). Tourism and gastronomy. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 731–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2003.12.014

- Cohen, E., & Avieli, N. (2004). Food in tourism: Attraction and impediment. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(4), 755–778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.02.003

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Conner, M., & Armitage, C. J. (1998). Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(15), 1429–1464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01685.x

- Coşkun, M. N. (2011). Vücut geliştirme sporu ile ilgilenen erkek yetişkin bireylerde beden algısının yeme davranışı ve besin tüketimi ile ilişkisi. Yayımlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Başkent Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü.

- Çulhacık, G. D., & Durat, G. (2017). Correlation of orthorexic tendencies with eating attitude and obsessive compulsive symptoms. Journal of Human Sciences, 14(4), 3571–3579. https://doi.org/10.14687/jhs.v14i4.4729

- Dallman, M. F., Pecoraro, N., Akana, S. F., La Fleur, S. E., Gomez, F., Houshyar, H., Bell, M. E., Bhatnagar, S., Laugero, K. D., & Manalo, S. (2003). Chronic stress and obesity: A new view of “Comfort Food”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(20), 11696–11701. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1934666100

- De Lauzon-Guillain, B., Basdevant, A., Romon, M., Karlsson, J., Borys, J. M., & Charles, M. A., & The Fleurbaix Laventie Ville Sante FLVS Study Group. (2006). Is restrained eating a risk factor for weight gain in a general population? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 83(1), 132–138. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/83.1.132

- Desmet, P., & Schifferstein, H. (2008). Sources of positive and negative emotions in food experience. Appetite, 50(2–3), 290–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2007.08.003

- DiPietro, R. B., Roseman, M., & Ashley, R. (2004). A study of consumers’ response to quick service restaurants’ healthy menu items: Attitudes versus behaviors. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 7(4), 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1300/J369v07n04_03

- Do Valle, P., & Assaker, G. (2016). Using partial least squares structural equation modeling in tourism research: A review of past research and recommendations for future applications. Journal of Travel Research, 55(6), 695–708. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515569779

- Durlu Özkaya, F., & Cömert, M. (2017). Türk mutfağında yolculuk. Detay Yayıncılık.

- Eertmans, A., Victoir, A., Vansant, G., & Bergh, Ö. V. (2005). Food-related personality traits, food choice motives and food intake: Mediator and moderator relationships. Food Quality and Preference, 16(8), 714–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2005.04.007

- Elfhag, K., & Morey, L. C. (2008). Personality traits and eating behavior in the obese: Poor self-control in emotional and external eating but personality assets in restrained eating. Eating Behaviors, 9(3), 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.10.003

- Ermiş, E., Doğan, E., Erilli, N. A., & Satıcı, A. (2015). Üniversite öğrencilerinin beslenme alışkanlıklarının incelenmesi: Ondokuz mayis üniversitesi örneği. Spor Ve Performans Arastirmalari Dergisi, 6(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.17155/spd.67561

- Evers, C., Adriaanse, M., de Ridder, D. T., & de Witt Huberts, J. C. (2013). Good mood food. Positive emotion as a neglected trigger for food intake. Appetite, 68, 1(7). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.04.007

- Evers, C., Stock, F. M., & Danner, U. N. (2011). The shaping role of hunger on self-reported external eating status. Appetite, 57(2), 318–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.05.311

- Eves, A., Corney, M., Kipps, M., Noble, C., Lumbers, M., & Price, M. (1996). The nutritional implications of food choices from catering outlets. Nutrition and Food Science, 5, 26–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/00346659610129314

- Farças, D., & Gonçalves, M. (2017). Motivations and cross-cultural adaptation of self-initiated expatriates, assigned expatriates, and immigrant workers: The case of Portuguese migrant workers in the United Kingdom. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 48(7), 1028–1105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117717031

- Fenko, A., Leufkens, J. M., & Hoof, J. J. (2015). New product, familiar taste: Effects of slogans on cognitive and affective responses to an unknown food product among food neophobics and neophilics. Food Quality and Preference, 39, 268–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.07.021

- Fischler, C. (1988). Food, self and identity. Social Science Information, 27(2), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901888027002005

- Fortes, L. S., Neves, C. M., Filgueiras, J. F., Almeida, S. S., & Ferreira, M. E. C. (2013). Body dissatisfaction, psychological commitment to exercise and eating behavior in young athletes from aesthetic sports. Brazilian Journal of Kinanthropometry and Human Performance, 15(6), 695–704. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbcdh/v15n6/a07v15n6.pdf

- Fotopoulos, C., Krystallis, A., Vassallo, M., & Pagiaslis, A. (2009). Food choice questionnaire (FCQ) revisited. Suggestions for the development of an enhanced general food motivation model. Appetite, 52(1), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2008.09.014

- French, S. A., Epstein, L. H., Jeffery, R. W., Blundell, J. E., & Wardle, J. (2012). Eating behavior dimensions. Associations with energy intake and body weight. A review. Appetite, 59(2), 541–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.07.001

- Germann, M. J. (2007). Eating difference: The cosmopolitan mobilities of culinary tourism. Space and Culture, 10(1), 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331206296383

- Gezmen Karadağ, M., Çelebi, F., Ertaş, Y., & Şanlıer, N. (2014). Geleneksel Türk mutfağindan seçmeler: Besin öğeleri açisindan değerlendirilmesi. Detay Yayıncılık.

- Giritlioğlu, İ. (2008). Türk mutfağında zeytinyağı ve zeytinyağının kullanımı. I.Ulusal Zeytin Öğrenci Kongresi. 17-18 Mayıs.

- Glanz, K., Basil, M., Maibach, E., Goldberg, J., & Snyder, D. (1998). Why Americans eat what they do: Taste, nutrition, cost, convenience, and weight control concerns as influences on food consumption. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 98(10), 1118–1126. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00260-0

- Gorrell, S., Nagata, J. M., Hill, K. B., Carlson, J. L., Shain, A. F., Wilson, J., Alix Timko, C., Hardy, K. K., Lock, J., & Peebles, R. (2019). Eating behavior and reasons for exercise among competitive collegiate male athletes. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00819-0

- Groves, J. M., & O’Connor, P. (2018). Negotiating global citizenship, protecting privilege: Western expatriates choosing local schools in Hong Kong. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 39(3), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2017.1351866

- Gül, T., (2011). Sağlıklı beslenme kavramı ve üniversite öğrencilerinin beslenme alışkanlıklarına yönelik tutum ve davranışları: çukurova örneği. Yayımlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Çukurova Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

- Güler, S. (2010). Türk mutfak kültürü ve yeme içme alışkanlıkları. Dumlupinar Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 26, 24–30. https://www.acarindex.com/dosyalar/makale/acarindex-1423876631.pdf

- Gürman, Ü. (2000). Yemek pişirme teknikleri ve uygulaması (1. baskı ed.). ABC Matbaacılık.

- Haak Saheem, W., Brewster, C., & Lauring, J. (2019). Low-status expatriates. Journal of Global Mobility, 7(4), 321–324. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-12-2019-074

- Haase, A. M. (2011). Weight perception in female athletes: Associations with disordered eating correlates and behavior. Eating Behaviors, 12(1), 64–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.09.004

- Hair, J., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019b). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hair, J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. (2019a). Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. European Journal of Marketing, 53(4), 566–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2018-0665

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed. ed.). Sage.

- Hatipoğlu, A. (2010). İnançlarin gastronomi üzerindeki etkileri: Bodrum’daki beş yildizli otellerin mutfak yöneticilerinin görüşlerinin belirlenmesine yönelik bir araştırma. Yayımlanmamış Yüksek LisansTezi. Sakarya Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

- Heatherton, T. F., Polivy, J., & Herman, C. P. (1989). Restraint and internal responsiveness: Effects of placebo manipulations of hunger state on eating. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 98(1), 89–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.98.1.89

- Henderson, J. C. (2009). Food tourism reviewed. British Food Journal, 111/4, 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700910951470

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In R. R. Sinkovics & P. N. Ghauri (Eds.), Advances in International Marketing (pp. 277–320). Emerald.

- Henseler, J. (2017). Bridging design and behavioral research with variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of Advertising, 46(1), 178–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2017.1281780

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Herman, C. P., & Polivy, J. (1980). Restrained Eating. In A. Stunkard (Ed.), Obesity (pp. 208–225). Saunders.

- Herman, C. P., & Mack, D. (1975). Restrained and unrestrained eating. Journal of Personality, 43(4), 647–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1975.tb00727.x

- Hincks, R. (2018). Expatriates in higher education: Paths to teaching in the local language. Exploring Language Education Conference, Exploring Language Education. urn: nbn:se:kth:diva-263809.

- Işık, C. (2019). Bir hedef pazar seçeneği olarak yerleşik yabancilarin dental turizm kapsamindaki potansiyeli: Kuşadaı IDC örneği. Yayımlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Aydın Adnan Menderes Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

- Kabir, A., Miah, S., & Islam, A. (2018). Factors influencing eating behavior and dietary intake among resident students in a public university in Bangladesh: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE, 13(6), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198801

- Kaplan, H. L., & Kaplan, H. S. (1957). The psychosomatic concept of obesity. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 125(2), 181–201. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-195704000-00004

- Kargar Mohammadınazhad, A. (2011). Üniversite öğrencilerinde farklı beslenme indeksleri ile yeme davranışının değerlendirilmesi. Yayımlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Hacettepe Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü.

- Karsavuran, Z. (2018). Sokak yemekleri: Farklı disiplinlerin yaklaşımı ve gastronomi turizmi alanında sokak yemeklerinin değerlendirilmesi. Journal of Tourism and Gastronomy Studies, 6(1), 246–265. https://doi.org/10.21325/jotags.2018.185

- Kelly, A. C., & Stephan, E. (2016). A daily diary study of self-compassion, body image, and eating behavior in female college students. Body Image, 17, 152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.03.006

- Kelly, S. D., Howe, C. J., Hendler, J. P., & Lipman, T. H. (2005). Disordered eating behaviors in youth with type 1 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator, 34(4), 572–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721705279049

- Kim, K. O. (2018). A case study on cross-cultural adaptation and transformative learning of expatriates. The Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 50(1), 249–277.

- Kim, Y. G., & Eves, A. (2012). Construction and validation of a scale to measure tourist motivation to consume local food. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1458–1467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.01.015

- Kızıldemir, Ö., Öztürk, E., & Sarıışık, M. (2014). Türk mutfak kültürünün tarihsel gelişiminde yaşanan değişimler. Aibü Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 14(3), 191–210. https://app.trdizin.gov.tr/publication/paper/detail/TWpBeE5UVXhNUT09

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications.

- Konttinen, H. (2012). Dietary habits and obesity: The role of emotional and cognitive factors. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Helsinki.

- Kozan, D. (2013). Tokat’ta spor merkezlerine devam eden kadınların, beslenme alışkanlıkları, zayıflamaya yönelik uygulamaları ve beslenme bilgi düzeylerinin belirlenmesi. Yayınlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Selçuk Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

- Kulikova, E., Alimova, M., Ovtcharenko, A., & Kunovski, M. (2017). Specifics of linguistic-cultural adaptation of foreign students and expatriates in the Russian-speaking environment (as exemplified by non-philology students and French expatriates). Man in India, 97(5), 1–12. https://serialsjournals.com/abstract/63686_1.pdf

- Kurt, E. (2014). Okul öncesi ve okul dönemi çocuklarda yemek yeme davranışının değerlendirilmesi. Turgut Özal Üniversitesi Tıp Fakültesi Çocuk Sağlığı ve Hastalıkları Uzmanlık Tezi.

- Lai, W., & Yang, C. (2017). Barriers expatriates encounter during cross-cultural interactions. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 25(3), 239–261. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218495817500091

- Lee, I., & Arcodia, C. (2011). The role of regional food festivals for destination branding. International Journal of Tourism Research, 13(4), 355–367. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.852

- Lee, K., & Gould, R. (2012). Predicting congregate meal program participation: Applying the extended theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3), 828–836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.09.019

- Levitan, R. D., & Davis, C. (2010). Emotions and eating behavior: Implications for the current obesity epidemic. University of Toronto Quarterly, 79(2), 783–799. https://doi.org/10.3138/utq.79.2.783

- Lopez-Guzman, T., & Sanchez-Canizares, S. (2012). Gastronomy, tourism and destination differentiation: A case study in Spain. Review of Economics & Finance, 1, 63–72. http://www.bapress.ca/Journal-6/Gastronomy,%20Tourism%20and%20Destination%20Differentiation--A%20Case%20Study%20in%20Spain.pdf

- Lowe, M. R., & Butryn, M. L. (2007). Hedonic hunger: A new dimension of appetite? Physiology & Behavior, 91(4), 432–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.006

- Mak, A. H. N., Lumbers, M., Eves, A., & Chang, R. C. Y. (2013). An application of the repertory grid method and generalized Procrustes analysis to investigate the motivational factors of tourist food consumption. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 35, 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.07.007

- Mennell, S., Murcott, A., Van Otterloo, A. H. (1992). The sociology of food : eating, diet and culture. London: Sage Publications.

- Milosevic, J., Zezelj, I., Gorton, M., & Barjolle, D. (2012). Understanding the motives for food choice in western Balkan countries. Appetite, 58(1), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.09.012

- Murphy, C., Takahashi, S., Bovaird, J., & Koehler, K. (2019). Relation of aerobic fitness, eating behavior and physical activity to body composition in college-age women: A path analysis. Journal of American College Health, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2019.1647210

- Nawijn, J., & Veenhoven, R. (2011). The effect of leisure activities on life satisfaction: The importance of holiday trips. In I. Bardar (Ed.), The Human Pursuit of Well-Being: A Cultural Approach (pp. 39–53). Springer Science.

- Nunes, I. M., Felix, B., & Prates, L. A. (2017). Cultural intelligence, cross-cultural adaptation and expatriate performance: A study with expatriates living in Brazil. Revista De Administração, 52(3), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rausp.2017.05.010

- Ogren, J. (2008). The many meanings of food and their impact on eating behaviour. In J. Buckroyd. & S. Rother (Eds.), Psychological responses to eating disorders and obesity: Recent and innovative work (pp. 17–35). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Oliver, G., Wardle, J., & Gibson, E. L. (2000). Stress and food choice: A laboratory study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62(6), 853–865. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200011000-00016

- Ouwens, M. A., Van Strien, T., & Van der Staak, C. P. (2003). Tendency toward overeating and restraint as predictors of food consumption. Appetite, 40(3), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-6663(03)00006-0

- Özdemir, B., & Kınay, F. (2004). Yabancı ziyaretçilerin Türk mutfağına ilişkin görüşleri: Antalya’yı ziyaret eden Alman ve Rus turistler üzerine bir araştırma. Gazi Üniversitesi Ticaret Ve Turizm Egitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 0(2), 5–28. http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:sR9iEhgR9uoJ:gazi.edu.tr/posts/download%3Fid%3D152269+&cd=1&hl=tr&ct=clnk&gl=tr

- Özgen, L., Kınacı, B., & Arlı, M. (2012). Ergenlerin yeme tutum ve davranışları. Ankara Üniversitesi Egitim Bilimleri Fakültesi Dergisi, 45(1), 229–248. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/508769

- Özgürel, G., & Avcıkurt, C. (2018). Yerleşik yabancıların Türkiye turizmine etkileri: Marmaris ilçesi örneği. Journal of Travel and Hospitality Management, 15(1), 195–225. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/457990