Abstract

Residential demand response is increasingly recognized as a valuable tool to increase power-system flexibility and to improve integration of renewable energy sources in the sustainable energy transition. However, low customer participation and engagement is one of the barriers hindering widespread implementation of residential demand response. To improve understanding of the factors influencing customer engagement in residential demand-response programs, this article investigates associated customer experiences and attitudes. This study is based on a systematic review and thematic synthesis of findings from past demand response-pilot projects. By synthesizing findings from multiple sources, the article provides insights into the customer perspective to inform the development of customer-oriented demand-response services and products. The results indicate that customer engagement in demand-response programs is influenced by multiple factors, including motivation, interaction and communication, and feedback. Particularly highlighted is the value of social interaction and support as well as the importance of customer education and easily interpretable information. To promote customer engagement, the electric utility industry should place more focus on building customer relationships and integrating customer perspectives into the design of demand-response programs.

Introduction

As a part of the 2030 Climate Target Plan, the European Commission has proposed a European Union (EU)-wide goal to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions (GHG) by at least 55% below 1990 levels by 2030 (European Commission Citation2020). To reach these ambitious environmental goals, large amounts of renewable energy are going to have to be integrated into electrical grids (IPCC Citation2018). Indeed, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), renewable energy sources are expected to meet 99% of the globally forecast electricity-demand increase during 2020–2025 (IEA Citation2020). The combined installed capacity of wind and solar power is projected to double in the same period, surpassing both natural gas and coal by 2024 (IEA Citation2020). This transition toward a more renewable-based energy portfolio is going to create a greater need for flexibility (i.e., the capability to maintain the balance between generation and consumption) in power systems (Riesz and Milligan Citation2015).

Demand response (DR) is an environmentally friendly and cost-effective alternative to traditional supply-side measures to provide flexibility and improve the integration of renewable energy sources (Siano Citation2014). DR can be used as a balancing resource to replace fossil fuel-fired generation capacity. By adding stability to the system, DR can reduce the need to use coal and gas-fired generation reserves and lessen the need for local network investments (European Commission Citation2016; USDOE Citation2006). DR may also indirectly provide overall energy-conservation effects by increasing customer-energy awareness (USDOE Citation2006). DR offers an effective way to mitigate GHGs and, consequently, the European Commission expects DR to play an important role in fostering the development of sustainable power systems (European Commission Citation2013, Citation2021). DR delivers its benefits by providing customers with control signals or financial incentives to adjust their consumption at strategic times and can be divided into implicit and explicit strategies (European Commission Citation2016; SEDC Citation2017). In implicit DR, consumers react to dynamic market or network-pricing signals while in explicit DR consumers receive direct payments to change their energy consumption upon request. The European Commission considers DR as a subset of demand-side management (DSM) which, in addition to DR, encompasses other measures and strategies to change energy consumption, such as energy efficiency and conservation (European Commission Citation2017, Citation2021). Traditionally, only large industrial consumers have participated in DR but researchers have increasingly recognized residential and small commercial consumers as an important source of demand-side flexibility (Bartusch and Alvehag Citation2014; Kessels et al. Citation2016; Siano Citation2014; Torriti, Hassan, and Leach Citation2010).

In the last two decades, numerous smart grid pilot projects have investigated the concept of residential DR yet coordinated DR programs and policies have been slow to develop (Torriti, Hassan, and Leach Citation2010; USDOE Citation2013). There are multiple challenges hindering the development of commercially viable DR programs including regulatory, technological, and economic barriers. Among these challenges are also social and behavioral aspects associated with customer participation in DR. Previous initiatives have shown that persuading customers to enroll in DR programs and keeping them actively engaged can be difficult (European Commission Citation2011). As a result, voluntary customer participation in DR programs is often low (Hobman et al. Citation2016; Kim and Shcherbakova Citation2011; Nicolson, Fell, and Huebner Citation2018).

There are many reasons for low customer engagement in DR. There is a lack of effective promotion and education about DR programs and their benefits, and customers are unlikely to actively seek out this information (Dütschke and Paetz Citation2013). Moreover, the customer benefits of DR are often framed from the perspective of the rational consumer whose actions are predominantly driven by financial incentives (Nicolson, Fell, and Huebner Citation2018; Strengers Citation2014). However, when adopting new smart home technologies or energy services, customers assess more than just the economic factors. Considerations such as the potential impacts on lifestyle and comfort, data security, and privacy, as well as environmental values, play a role in customers’ decision-making processes (Gyamfi and Krumdieck Citation2011; Paetz, Dütschke, and Fichtner Citation2012; Stenner et al. Citation2017). If participation in DR is too inconvenient and disruptive to daily routines and habits, they are unlikely to sign up and actively participate (Heylen et al. Citation2020; Safdar, Hussain, and Lehtonen Citation2019). Moreover, due to distrust in utility companies and automation, customers are often reluctant to relinquish control of their electrical appliances (Balta-Ozkan et al. Citation2013; Karjalainen Citation2013; Lopes et al. Citation2016). Therefore, it is important that novel energy services and technologies are compatible with customers’ values and easily integrated into their daily lives (Juntunen Citation2014; Palm and Tengvard Citation2011).

Consequently, the focus of DR projects has been moving toward understanding customer engagement (European Commission Citation2011) and the subject has received increased attention in the academic literature in recent years. Previous studies have investigated the barriers and facilitators to customer engagement in DR and the use of related smart technologies (Ali et al. Citation2021; Li et al. Citation2021; Marikyan, Papagiannidis, and Alamanos Citation2019; Mela et al. Citation2018; Parrish et al. Citation2020), the social dimensions of customer engagement (Darby and McKenna Citation2012; Hafner et al. Citation2020; Moreno-Munoz et al. Citation2016), and customer segmentation (Gouveia, Seixas, and Long Citation2018; Sanguinetti, Karlin, and Ford Citation2018; Srivastava, Van Passel, and Laes Citation2018; Todd-Blick et al. Citation2020). However, understanding and incorporating customer perspectives in the design of DR programs has received less attention both in research and practice (Christensen et al. Citation2020; Strengers Citation2014). To promote growth in residential DR, the associated programs should be developed such that they correspond with customer preferences and values. To this end, information about how customers perceive different aspects of DR programs is of utmost importance. This article attempts to improve understanding of the underlying reasons affecting customer engagement by investigating customers’ experiences and attitudes toward participation in DR. The three research questions of this study are:

Which factors motivate customers to participate in DR programs?

How do social interactions and different communication channels influence customer engagement?

What is the role of feedback information in customer engagement?

This study is based on a systematic review and thematic synthesis of evidence from past DR programs. Thematic synthesis draws upon the techniques of thematic analysis to aggregate, compare, and integrate the findings of multiple studies. A synthesis of findings from multiple sources can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the subject than a single empirical study (Thomas and Harden Citation2008). Sorrell (Citation2007) and Warren (Citation2014) have proposed that the use of systematic reviews can improve the quality of evidence in the field of energy policy and practice and that qualitative research in particular can help explain why certain energy policies and programs succeed or fail. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to focus exclusively on customer experiences and attitudes toward DR. By conducting a systematic investigation of customer perspectives, we aim to support the development of customer-oriented DR and to provide insights for smart grid policy.

Method

The study was conducted by following the Enhancing Transparency of Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) framework (Tong et al. Citation2012).

Search strategy and selection criteria

We focused on the collection of grey literature, that is material produced and published by organizations outside traditional academic publishing and distribution channels. Grey literature can be an extensive and valuable source of information that includes various policy- and research-relevant documents, such as clinical practice guidelines, research reports, program-evaluation studies, and legislation (Godin et al. Citation2015). These materials can promote and support evidence-based practice and policy in many ways and they often contain findings that may not get published in academic literature. For instance, negative or null findings are less likely to be published in academic journals compared to positive or confirmatory findings (Decullier, Lhéritier, and Chapuis Citation2005; Dwan et al. Citation2008) and, as such, grey literature can act as a vehicle for disseminating findings that otherwise might never be publicly disclosed (Bellefontaine and Lee Citation2014). Furthermore, many practitioners might not be motivated to or have the means to publish their work in peer-reviewed journals (Haddaway and Bayliss Citation2015; Mahood, Van Eerd, and Irvin Citation2014). As a result, grey literature can promote a more comprehensive and balanced view of the available evidence (Paez Citation2017).

In addition to expanding the scope of available evidence, grey literature can also help to bridge the gap between research and practice. Grey literature is typically produced by practitioners to inform public policy and to translate knowledge for public use, and consequently these materials are heavily used and highly valued in policy and practice work (Lawrence et al. Citation2014). In the same vein, grey literature can provide information with high ecological validity to academic research that seeks to inform policy and practice. The materials can be of particular importance for syntheses exploring the effectiveness of certain interventions and initiatives, as such syntheses often require data that is practical and applied (Haddaway and Bayliss Citation2015). Therefore, reviews focused on grey literature can complement work focused on academic research (Piggott-McKellar et al. Citation2019), ultimately helping to form a holistic view of the subject. There is a scarcity of systematic reviews of grey literature regarding DR, which is why this review explores these kinds of materials pertaining to relevant customer perspectives.

The focus of the study is on projects included in the European Commission’s Joint Research Center (JRC) database of smart grid projects (European Commission Citation2017). We screened the JRC database for initiatives between 2000 and 2020 that incorporated DR. To be included, the project had to incorporate DR and report on customer perspectives toward DR (i.e., thoughts, feelings, experiences, attitudes, or preferences toward any aspect of DR programs or their implementation). Furthermore, project findings had to be available in English. No study-design restrictions were applied. After limiting the database-search results to include only projects that started between 2000 and 2020 and incorporated DSM (including DR and other DSM interventions), we conducted a search for the documentation of those projects.

Our search strategy was based on a protocol outlined by García-Holgado, Marcos-Pablos, and García-Peñalvo (Citation2020) for locating research-project documentation. First, we attempted to identify the official project websites and to locate published content on the website. In cases where the project website was unavailable, or where the documentation was not accessible on the website, we conducted additional searches using the Google and Google Scholar search engines. Search terms included the project acronym and full name as exact terms as well as keywords such as “smart grid,” “demand response,” and “tariff” when the results had to be narrowed down. The searches were restricted to include only portable-document format (PDF) files. After locating the project documentation, we excluded all materials and projects that did not incorporate DR, report on customer perspectives, or convey their findings in English.

Quality assessment and data extraction

We evaluated the quality of the project documents with a quality-assessment scale for use in systematic reviews in the field of energy policy. Warren (Citation2014) argues that due to the heterogeneity of methods and regional contexts, quality assessment of DSM interventions should focus more on the transparency of their implementation and evaluation. The quality-assessment scale contains six items: (1) implementation; (2) evaluation; (2) peer review; (4) copyright, regulatory compliance, and conflicts of interest; (5) publishing organization; and (6) data reporting. One researcher assessed the quality of each project. The projects were not weighted based on the quality assessment.

The following data were extracted from the project documents: project name, participating countries, project period, number of participants, project objectives as reported by the authors, type of DR studied, data-collection methods, and the project’s main findings. The data extracted for analysis included direct quotes from the participants, results of questionnaires and the authors’ conclusions, and interpretations of the results.

Data synthesis

We adopted a three-stage thematic synthesis as described by Thomas and Harden (Citation2008). No restrictions were set as to where data were extracted from the project documents. Following multiple readings of the materials, the project findings were manually extracted and coded line-by-line by one researcher to create descriptions of the data. We took a theory-driven approach to the coding, in that the objective was to identify features related to the study aims (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). The codes were then grouped into descriptive themes that captured something important about the data in relation to the research questions. Based on the descriptive themes, we developed the main analytical themes and their subthemes.

Results

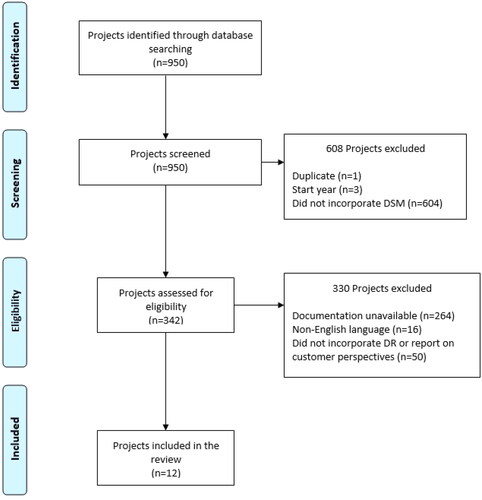

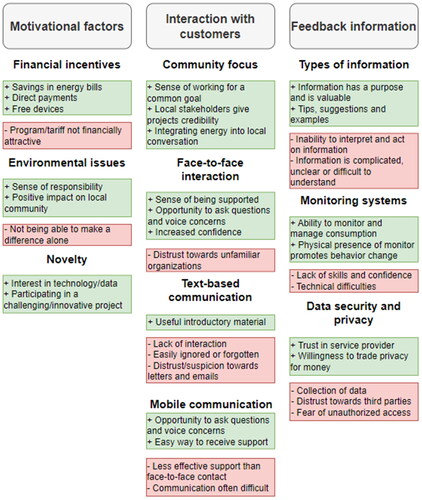

A flowchart of the search process and project selection is shown in . The JRC database included a total of 950 projects. Three projects were excluded due to their starting year and 604 projects were excluded for not incorporating DSM. After removing one duplicate, 342 projects remained. A search for the documentation of the remaining projects was then conducted. We excluded a total of 264 projects due to unavailability of documentation. Each title and abstract of all available documents (786 in total) of the remaining 78 projects were screened by one researcher. We excluded sixteen projects due to language and a further 50 were eliminated for not incorporating DR or reporting on customer perspectives toward DR. Of the initial 950 projects listed in the JRC database, 12 projects, comprising a total of 26 documents, were included in the analysis. Characteristics of all of these projects are reported in . Thematic synthesis resulted in three main analytical themes and 10 subthemes (). The main themes included: motivational factors, interaction with customers, and feedback information. illustrates each theme and subtheme by providing a selection of quotes from project participants and authors.

Figure 2. Thematic synthesis of positive (+) and negative (-) customer perceptions toward demand response.

Table 1. Characteristics of projects included in the review.

Table 2. Quotations from project participants and authors to illustrate each theme.

Motivational factors

Financial incentives

Financial incentives were the most frequently reported factor influencing customers’ decision-making regarding participation in DR projects. In 10 of the 12 projects, many participants cited this factor as either an explicit reason for engaging in the project (CLNR Citation2014; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2019a; UK Power Networks Citation2019a; WPD Citation2013; WPD&RSW Citation2017) or as an expected benefit of energy-saving behavior (CLNR Citation2014; E-balance Consortium Citation2017; NOBEL Citation2012; SSEN Citation2018a, Citation2018b; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018b; UK Power Networks Citation2019c; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017). While most customers expressed interest in receiving financial incentives in the form of savings on electricity bills or direct payments (CLNR Citation2014; E-balance Consortium Citation2017; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2019a; NOBEL Citation2012; SSEN Citation2018a; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018b; UK Power Networks Citation2019a; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017; WPD Citation2013; WPD&RSW Citation2017), some were willing to participate in DR projects in exchange for devices, such as smart meters, in-home energy displays or other appliances (CLNR Citation2013; Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; UK Power Networks Citation2019a). Although financial incentives were the most frequently cited reason for participation, there were many customers who valued other aspects to a greater degree: four projects reported that financial incentives were not always the main driver for customer participation (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018b; Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2018; WPD&RSW Citation2017). Most notably, money was the main motivator for only 28% of the German participants of the Flex4Grid project (Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018). Using money as the sole driver can limit customer participation, as those who are well off may not be prompted by the prospect of savings (SSEN Citation2019). Moreover, some daily household routines and habits, cooking in particular, are largely fixed and customers are unlikely to reschedule these activities in response to monetary incentives (SSEN Citation2019; CLNR Citation2014). However, even though financial incentives may not be enough to motivate all customers, the lack of monetary incentives will likely hinder participation. Two projects reported that the inability to offer sufficient financial incentives to customers made recruitment for the project difficult (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018a; WPD&RSW Citation2017).

Environmental issues

Nine of the 12 projects identified environmental reasons as an important factor influencing the decision to adopt energy-saving behaviors (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018b; E-balance Consortium Citation2017; Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2018, Citation2019a; NOBEL Citation2012; SSEN Citation2018b, Citation2019; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018b, Citation2018d; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017; WPD Citation2013). Many customers felt a sense of responsibility toward the environment and expressed that everyone should do their part in environmental protection (E-balance Consortium Citation2017; Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2018, Citation2019a; NOBEL Citation2012; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018d). By contrast, feeling responsible for such big and complex issues can lead to a feeling of disempowerment and cause disengagement (SSEN Citation2019). In addition to this sense of personal responsibility, there was a sentiment among participants that environmental issues are a collective responsibility. In four projects, customers emphasized the importance of collective action and the project’s impact on their local community (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018b; E-balance Consortium Citation2017; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2018, Citation2019a; SSEN Citation2018b, Citation2019). There was some evidence suggesting that interest in environmental issues may be a stronger driver of active participation and behavior change compared to financial incentives. In the Italian demonstration of the FLEXICIENCY project, it was found that compared to passive participants, active participants were more likely to cite environmental issues as the reason for their engagement (FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2019a).

Novelty

Seven projects reported novelty (i.e., the desire of customers to learn or experience something new as a motivator for participation) (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018a; Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2018; UK Power Networks Citation2019a; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017; WPD Citation2013; WPD&RSW Citation2017). In many cases, customers were interested in technology and data related to the project. For example, four projects identified customers’ desire to learn more about their energy consumption as one of the main motivating factors for their participation (Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2018; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017; WPD Citation2013). Furthermore, the novel technologies associated with DR were attractive to some customers: two projects identified customers’ interest in new technologies as an important reason for their participation (Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2018). Participants in these demonstrations were predominantly male (Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2018), which may explain the high interest in technology, as it has been shown that males tend to have more favorable attitudes toward technology use than females (Cai, Fan, and Du Citation2017; Whitley Citation1997). Some customers did not expect to receive any benefits from DR and chose to participate in the project for its own sake. These individuals participated to challenge themselves or simply to be involved in something innovative (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018a; UK Power Networks Citation2019a; WPD&RSW Citation2017).

Interaction with customers

Community focus

Eight projects reported experiences of focusing on community engagement (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018a; NOBEL Citation2012; SSEN Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2019; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018a, Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017; WPD Citation2013; WPD&RSW Citation2016, Citation2017). Community-engagement efforts included emphasizing the local impacts of the project and involving local stakeholders in its implementation. Designing DR programs so that they fit the local agenda and benefit the community as a whole can help promote them and foster active customer participation by building a sense of working together toward a common goal. Many customers liked the idea of engaging with their community (NOBEL Citation2012) and framing DR as a local effort made the project more appealing to customers (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018a; SSEN Citation2019; WPD Citation2013). Involving communities in the design of DR programs and inviting community members to take part in field trials engaged customers and demonstrated that the program was a collaborative effort between the community and the service provider (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018a; SSEN Citation2019). Social events and community gatherings facilitated conversations around energy issues and promoted communities to develop and share their own ideas and solutions to address these issues (SSEN Citation2019; WPD Citation2013). This kind of bottom-up approach where the DR program was designed together with the local community ensured that customers did not perceive DR as something that was imposed on them (SSEN Citation2019). Approaching the topics of energy use and DR from the perspective of their relevance to the local community, instead of treating them as a separate issue, made customers more open and willing to discuss such topics (SSEN Citation2019; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018a). Consequently, focusing DR programs on close-knit communities can significantly improve customer engagement, as such communities show enthusiasm toward initiatives affecting their well-being (SSEN Citation2019; WPD Citation2013). The involvement of local stakeholders in the recruitment and support of customers gave a DR program credibility in the eyes of customers and improved customer engagement. Customers tend to trust local stakeholders, such as regional authorities, community members, businesses, and local media. Such stakeholders can act as an intermediary between customers and the service provider (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018a; UK Power Networks Citation2019a; WPD Citation2013; WPD&RSW Citation2016).

Face-to-face contact

Six projects examined customers’ perception of face-to-face contact with the service providers (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; SSEN Citation2018a; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018a, Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a, Citation2019b; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017; WPD Citation2013). Face-to-face contact included interaction with the customers both individually and in groups. Overall, customers’ attitudes toward face-to-face contact were positive and this form of interaction proved to be a valuable tool for recruiting and supporting customers, and ultimately in building the customer-service provider relationship. Door-to-door recruitment was commonly used in the initial recruitment of participants (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018a; UK Power Networks Citation2019a; WPD Citation2013). This approach was effective in helping customers understand the nature of the DR project, as it allowed them to ask questions and to voice their concerns before committing to the project (UK Power Networks Citation2019a; WPD Citation2013). However, customers’ reservations toward unfamiliar organizations may be a barrier to the use of this approach: customers might not be receptive to door-to-door recruitment if it is undertaken by parties not previously known to them (SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018a). By contrast, when carried out by an organization the customers are already familiar with, door-to-door recruitment can be highly successful (SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018a; UK Power Networks Citation2019a).

Maintaining contact with customers serves an important role in ensuring that they stay engaged with the program. For example, some customers prefer to receive technical support related to the use of DR technologies on a face-to-face basis rather than by telephone or online (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c). Furthermore, face-to-face interaction can instill a sense of being supported and it can help reassure customers that they have not been abandoned (SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c). Supporting the customers and providing them with an opportunity to share their experiences can make them more confident in managing their energy consumption (SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017) and may reduce dropout rates (UK Power Networks Citation2019a). Professional support can be combined with peer support in social events such as workshops, customer panels, and other informational events (SSEN Citation2018a; UK Power Networks Citation2019a; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017). These occasions allow customers to give feedback and to discuss the project in a more social environment. Events themed around household activities, such as cooking, can be an effective way to discuss how everyday habits and practices relate to energy consumption (SSEN Citation2018a).

Text-based communication

Six projects reported on customers’ views on text-based communication such as letters and e-mails (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; CLNR Citation2013; SSEN Citation2018b; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a; WPD Citation2013). The use of text-based communication was met with mixed responses from customers. While some customers saw value in letters and e-mails as a source of information and education, unidirectional messaging does not allow for interaction between customers and the service provider and is unlikely to lead to true customer engagement when used alone.

Customers tended to regard text-based materials such as newsletters and informational letters as useful introductory material that helped to familiarize them with the project’s aims and the technology (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a; WPD Citation2013). Written information was found to work best when combined with face-to-face interaction (SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; WPD Citation2013). When used alone, letters and e-mails can be easily ignored or forgotten. When asked about such messages, many customers could not recall the contents of the messages, or even remember receiving the communications (SSEN Citation2018b; UK Power Networks Citation2019a). Moreover, messaging that is too frequent or overly repetitive may be detrimental to customer engagement. For instance, in the SAVE project, some customers noted that repeatedly receiving similar information made the communications of the service provider feel annoying and redundant (SSEN Citation2018b). Letters or e-mails can also be misidentified and some customers may be suspicious of these communication media. In the Energywise project, some customers mistakenly thought the recruitment letter was about switching energy providers and discarded it (UK Power Networks Citation2019a). The CLNR project was unable to enlist any customers via a recruitment email, likely because customers thought that these messages were fraudulent (CLNR Citation2013).

Mobile communication

Four projects reported experiences of engaging with customers via telephone calls or mobile instant messaging (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; CLNR Citation2013; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a). This means of communication offers some of the same benefits as face-to-face contact in that it allows delivery of in-depth explanations and provides customers with an opportunity to ask questions and raise concerns (SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a). Telephone calls can also allow the service provider to easily follow-up on customers and make sure they are able to participate effectively in the project (UK Power Networks Citation2019a). Furthermore, customer support via a mobile instant messaging application was positively received by customers as it allowed for asynchronous communication with an identifiable person (SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c). However, many customers perceived telephone advice to be less effective than face-to-face consultation, and tended to choose face-to-face contact over telephone calls when in need of support (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a). For instance, elderly customers and those with disabilities may require more extensive support (SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a). Moreover, reaching customers and effectively communicating about the project by telephone often proved to be difficult (CLNR Citation2013; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a). As such, it is important that the service provider offers various modes of support and engagement.

Feedback information

Types of information

Eleven projects reported customers’ views on the feedback information generated by the service providers. In ten projects, customers were provided with information of their past and current total energy consumption (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; CLNR Citation2014; E-balance Consortium Citation2017; Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2019b; NOBEL Citation2011; SSEN Citation2018b; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017). Additional information provided to the customers included information about energy consumption of specific devices in six projects (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; CLNR Citation2014; E-balance Consortium Citation2017; Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2019b; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c) and current electricity prices in three projects (CLNR Citation2014; NOBEL Citation2011; UK Power Networks Citation2019a). Due to technical difficulties, one project was unable to deliver any feedback information (WPD&RSW Citation2017).

In the projects reviewed here, feedback information provided to customers focused almost exclusively on energy-consumption data. However, data without context can be meaningless: in addition to information on energy consumption, customers also need guidance on how to interpret and act on it. They understand the purpose of energy-consumption feedback, but often struggle to make use of it simply due to not knowing how to save energy (CLNR Citation2014; E-balance Consortium Citation2017; Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; SSEN Citation2018b). Many customers found energy-consumption information to be too complicated, unclear, or difficult to understand (CLNR Citation2014; Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2019a; SSEN Citation2018b; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017). Moreover, some customers expressed the need for more practical information such as tips, suggestions, and examples of concrete measures to reduce energy consumption (SSEN Citation2018b; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017; WPD&RSW Citation2017). Making energy-consumption information easy to interpret can enhance active participation. For instance, the CLNR project found positive customer reactions to the use of a simple “traffic light” feature where current energy-consumption level or price was indicated by color. This feature was found to be intuitive to use and was the most relied upon feature of the feedback system (CLNR Citation2014).

Monitoring systems

Nine projects investigated customers’ attitudes and experiences toward the use of different monitoring systems for delivering feedback information. These systems included in-home displays (IHDs) and digital platforms (i.e., mobile applications and websites). Monitoring systems can play a valuable role in allowing customers to participate in DR, but their potential may be undermined by the lack of education offered by service providers.

Five projects reported customers’ responses to the use of IHDs (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; CLNR Citation2014; E-balance Consortium Citation2017; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a). Generally speaking, customers positively perceived IHDs and both regarded them as useful and understood the value they can provide (CLNR Citation2014; E-balance Consortium Citation2017; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a). Perceived benefits of IHDs are mostly related to being able to monitor and manage energy consumption (CLNR Citation2014; E-balance Consortium Citation2017; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a). The physical presence of the display has an important role in promoting behavior change and receiving continuous feedback can help customers associate their energy behavior with outcomes (CLNR Citation2014; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a). Furthermore, simply having the device in a visible place can serve to remind customers to pay attention to their energy usage (CLNR Citation2014; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a). Although most customers were able to use and benefit from IHDs (CLNR Citation2014; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a), there were some who struggled to use this technology because they might not have had the necessary skills or confidence (SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UK Power Networks Citation2019a).

Eight projects reported customer responses to receiving consumption feedback via digital platforms (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; E-balance Consortium Citation2017; Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2018, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; NOBEL Citation2012; SSEN Citation2018b; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017). From the customer’s point of view, digital platforms can fill a role similar to IHDs in that they allow for monitoring and management of energy consumption (E-balance Consortium Citation2017; Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2018, Citation2019a). However, five of the eight projects where digital platforms were used for energy-consumption feedback reported fairly low usage of these services (FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2019b; NOBEL Citation2012; SSEN Citation2018b; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017). For example, the Spanish demonstration of the UPGRID project reported that only 7.8% and 1.3% of customers, respectively, reported tracking their electricity consumption using the website and the mobile application (UPGRID Consortium Citation2017). Moreover, in the SMART-UP project the proportion of customers monitoring their consumption via a mobile application declined from 40% to 5% in the span of three months (SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c). The low usage of digital platforms may have been due to customers’ generally low regard for the quality and value of consumption information (UPGRID Consortium Citation2017), as well as due to complications related to the use of these platforms (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2019b; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017). Indeed, many customers reported experiencing technical problems or difficulties in understanding how to use the digital platforms (Flex4Grid Consortium Citation2018; FLEXICIENCY Consortium Citation2019b; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017). Moreover, some customers had difficulties in accessing the platform (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017), and others were not even aware that such a platform existed (SSEN Citation2018b).

Data security and privacy

Seven projects investigated customers’ attitudes toward data security and privacy issues (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; CLNR Citation2014; E-balance Consortium Citation2017; NOBEL Citation2012; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c, Citation2018d; UK Power Networks Citation2019b; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017). Data security and privacy appear to be issues that many customers may not be aware or conscious of, but are nonetheless seen as important when specifically asked about. In open interviews, customers rarely mentioned data security and privacy issues (CLNR Citation2014; E-balance Consortium Citation2017; UK Power Networks Citation2019b). However, in surveys, they expressed concerns along these lines and generally considered them to be important considerations (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; E-balance Consortium Citation2017; NOBEL Citation2012; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017). The collection of too much and too detailed data was seen as a potential threat to privacy (E-balance Consortium Citation2017; NOBEL Citation2012; SMART-UP Consortium Citation2018c; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017). For example, some customers had concerns regarding information that may reveal their behavioral patterns (E-balance Consortium Citation2017; NOBEL Citation2012) or socioeconomic status (UK Power Networks Citation2019a). Moreover, there were issues regarding disclosure of personal information to third parties and the possibility of unauthorized access (E-balance Consortium Citation2017; UPGRID Consortium Citation2017). Nevertheless, many customers felt that their privacy was adequately protected during the project (AnyPLACE Consortium Citation2018c; NOBEL Citation2012) and some expressed indifference toward the subject (E-balance Consortium Citation2017).

There was evidence to suggest that some customers may be willing to trade some of their privacy for monetary benefits. In the NOBEL project, around 60% of customers were willing to share more detailed information with their service provider in exchange for financial compensation (NOBEL Citation2012). The e-balance project found that when asked to rank attributes of an energy-management system in order of importance, customers valued tangible attributes such as monetary benefits and innovative features more than data security (E-balance Consortium Citation2017).

Discussion

This systematic review has investigated residential customers’ experiences and attitudes toward DR programs. Three main themes emerged from the thematic synthesis: motivational factors, interaction with customers, and feedback information. The results show that customers’ uptake of and engagement in DR depends on their intrinsic and extrinsic motivations; their knowledge, skills and confidence; social interactions; and the specific technology.

The decision of customers to adopt energy-saving behaviors is influenced by a variety of values and motivational factors. In addition to the potential financial benefits of DR, customers are interested in the possibility of contributing to environmental protection, the opportunity to use smart technologies, and the chance to participate in something innovative. Residential DR programs have typically attempted to encourage customer participation with financial incentives, but as the results of this review show, we should not overlook the role of intrinsic motivation. Indeed, it has been shown that customers’ readiness and intention to adopt smart and sustainable technologies is influenced by their interest in technology and environmental awareness (Ali et al. Citation2020; Choi and Johnson Citation2019; Marikyan, Papagiannidis, and Alamanos Citation2019; Tu et al. Citation2021). The results here indicate that these factors can motivate customers to participate in DR programs, sometimes even in the absence of financial incentives. Therefore, branding and marketing of DR should focus not only on its financial benefits, but also on its environmental impact and technological innovativeness. Furthermore, we found that the effectiveness of financial incentives is likely hindered by the fact that many customers are apt to value time and convenience over the financial benefits offered by DR. This finding is in line with studies drawing from social practice theory demonstrating that the notion that energy-consumption behavior is driven predominantly by economic rationality is flawed (Christensen et al. Citation2020; Strengers Citation2014; Verkade and Höffken Citation2017). For instance, Nicholls and Strengers (Citation2015) found that in households with children, energy-consumption patterns are largely dictated by daily routines and that these households are unlikely to change their consumption habits in response to dynamic pricing. In order to facilitate the participation of these customers in DR, it is important to allow them to do so in ways that are not too disruptive to their lifestyles and habits. Therefore, it is important that DR programs strive to implement flexible and versatile incentive structures. Moreover, when financial incentives are used, they should be sufficient to both attract extrinsically motivated customers and to prevent the crowding-out effect, that is, where the introduction of small monetary incentives may decrease intrinsic motivation (Bolle and Otto Citation2010; Frey and Jegen Citation2001). Previous research has shown that non-monetary incentives tend to promote greater and longer lasting energy-conservation efforts than monetary incentives (Handgraaf, Van Lidth de Jeude, and Appelt Citation2013; Mi et al. Citation2021). One reason for this outcome may be that customers become disillusioned and discouraged after learning that the actual financial benefits of such conservation efforts are relatively small (Bolderdijk et al. Citation2013). Nevertheless, as was found in this and other studies (Li et al. Citation2021; Parrish et al. Citation2020), financial incentives do strongly influence customer decisions to participate in DR programs. One potential explanation for this apparent discrepancy is that the role of financial incentives in DR is mainly to create an initial interest after which customer engagement is mostly driven by non-monetary incentives.

For customers to take a more active role in managing their energy use, more than incentives and marketing will be required: an interactive relationship between service providers and customers must be established. The findings of this review underline the importance of social interaction when introducing new energy services and products to customers. Customer engagement in DR programs requires reframing the perception of electricity as a passive purchase, and customers need support in doing so. Personal interaction with customers, face-to-face interaction in particular, can play an invaluable role in promoting customer engagement. By providing support to customers, answering their questions, and addressing any concerns they may have, service providers can begin to establish a trusting relationship with their customers and help to ensure that the customers are able to effectively participate in DR. The profound influence of trust was demonstrated particularly well in the Energywise project, where participants in the DR trial were recruited from a group of customers that had previously participated in an energy-saving trial and were already familiar with the organization. The participation rate in the Energyise DR trial was as high as 86%.

Building the customer service-provider relationship slowly and gradually can decrease customers’ perception of risk and increase their willingness to trial energy products and services that they otherwise might not be willing to try (VaasaETT Citation2012). Furthermore, many customers have a desire to interact with their local communities regarding energy issues. These customers expressed that energy issues should be integrated into the local agenda and be solved together for the benefit of everyone. Local, community-based energy projects can promote pro-environmental behaviors by facilitating collective action toward shared goals, aspirations, and benefits (Berka and Creamer Citation2018; Braunholtz-Speight et al. Citation2021; Williams, Charney, and Smith Citation2015). Furthermore, support from peers can play an important role in achieving and sustaining behavior change. A study by Rajaee, Hoseini, and Malekmohammadi (Citation2019) found that social influence had a significant effect on the perceived ease of using green building technologies. There is an opportunity for service providers to work together with local communities to develop a trusting and mutually beneficial relationship with customers by fostering an environment that provides both professional and peer support. As shown in this and other studies (Broska Citation2021; Savelli and Morstyn Citation2021), enabling communities to participate in the design and implementation of local energy initiatives can make such projects more relevant and meaningful to customers and consequently improve customer engagement. Implementing DR with this type of bottom-up approach gives customers more agency and responsibility while emphasizing the importance of a partnership between customers and service providers. Currently, utility companies tend to see their relationships with their customers as something driven by necessity rather than as a partnership (Honebein, Cammarano, and Boice Citation2011) and some express negative attitudes toward customer-engagement opportunities (Stephens et al. Citation2017).

The provision of feedback is essential for customers to understand and change their own energy behaviors. The findings here indicate that customers understand the purpose and value of this information, but often struggle to take advantage of it. Many customers who enrolled in DR programs lacked the necessary knowledge, skills, or confidence to use and benefit from the technology and information associated with energy-consumption monitoring. These customers may be unable to participate in DR despite wanting to do so. Previous research has shown that self-efficacy and perceived behavioral control are associated with energy-saving behaviors (Xu, Hwang, and Lu Citation2021) and the intention to adopt smart grid technologies (Billanes and Enevoldsen Citation2021; Perri, Giglio, and Corvello Citation2020; Yun and Lee Citation2015). Consequently, feedback consisting solely of energy-consumption data is unlikely to provide customers with the tools they need for active engagement in DR. This mirrors criticism raised by Strengers (2011, 2014) and others (Darby Citation2008; Verkade and Höffken Citation2017) about information that is designed first and foremost for the “Resource Man,” the hypothetical ideal consumer who is technologically savvy and who makes rational decisions based on the latest and best available evidence. However, to rely solely on consumption data is to ignore the social and cultural factors associated with energy use (Gram-Hanssen Citation2009; Shove Citation2010). The findings of this review suggest that for customers to have control over their energy use, they need to know not only what to do, but also how to do it: energy-consumption data should be made easily interpretable and be combined with practical guidance and concrete examples. Our results indicate that most effective types of feedback are those that allow customers to understand how their own routines and habits relate to their energy consumption. Examples of such feedback could include, for instance, simple visual cues indicating when energy consumption is higher than usual, as well as tips and suggestions to help customers consider how DR activities may be incorporated into their daily lives. To this end, customers may benefit more from monitoring systems with a physical presence, such as IHDs, which can serve to make energy consumption more immediately visible. Digital monitoring platforms require more active effort on the part of customers, and as such, are more suited for monitoring energy consumption retroactively. Retroactive monitoring may be less effective in facilitating energy-conscious behaviors since real-time monitoring tends to be more effective in improving energy awareness (de Moura, Cavalli, and da Rocha Citation2019).

Delivering feedback information involves the collection of customer data, which inevitably leads to security and privacy concerns. The findings here are in line with previous research in that customers’ security and privacy concerns may pose a barrier to the adoption of smart services and technologies (Braun et al. Citation2018; Ehrenhard, Kijl, and Nieuwenhuis Citation2014; Li et al. Citation2021; Tu et al. Citation2021). A review paper by Vigurs et al. (Citation2021) highlights guiding principles for addressing customer-privacy concerns relating to energy use-data sharing in smart energy systems. The authors emphasize the importance of principles such as transparency and communication and customer autonomy, as well as the involvement of customers in the planning and development of data-sharing processes. Making data policies accessible and providing customers with control over their data can enhance trust and effectively mitigate potential feelings of betrayal (Martin, Borah, and Palmatier Citation2017). Conversely, when levels of transparency and customer control are low, trust deteriorates and customer reactions become more negative (Martin, Borah, and Palmatier Citation2017). However, our results indicate that customers may not consider or be aware of security and privacy issues related to DR unless the concerns are brought to their attention. Therefore, to ensure that customers do not end up feeling deceived, it is important to inform them of the privacy and data-security aspects of DR during recruitment.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to focus exclusively on customer experiences and attitudes toward DR. Previous research has identified and described potential barriers and facilitators to customer participation in DR programs and to the use of related technologies (Balta-Ozkan et al. Citation2013; Darby and McKenna Citation2012; Ellabban and Abu-Rub Citation2016; Kim and Shcherbakova Citation2011; Li et al. Citation2021; Mela et al. Citation2018; Moreno-Munoz et al. Citation2016; Parrish et al. Citation2020). A review by Kessels et al. (Citation2016) evaluated the effectiveness of dynamic tariffs on encouraging customer engagement in DR. Similar to our study, the findings of Kessels et al. (Citation2016) underline the importance of customer-oriented approaches to DR, including customer education and support, ensuring compatibility of DR with customers’ lifestyles and habits, and tailoring incentives to suit the customers. Furthermore, as we have done, Kessels and colleagues focused their search on databases containing European smart grid projects. However, in contrast to our work, they focused on the effects and effectiveness of dynamic tariffs. Although our study discusses financial incentives, the different foci of the two reviews are reflected in the encompassed projects: only one project was included in both our and Kessel et al.’s (2016) reviews. By broadening the focus to include customer perspectives toward various motivational factors, social interactions, and feedback information, we submit that our work complements the findings of this prior investigation and offers new insights into customer perspectives.

The current study contributes to research and practice by synthesizing results from 12 European DR research projects and providing a comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence customers’ acceptance of and engagement in DR programs. However, our review has some limitations. First, we were limited to European DR projects and, as such, our results may not be generalizable to other global regions. Second, documentation of many projects indexed in the JRC database were unavailable and some relevant projects may not have been indexed in this source. Therefore, it is possible that we did not include certain important initiatives in this review. Third, there was significant heterogeneity in the methodology of these research projects as well as in their participant demographics and regional contexts. There were also differences in their goals. It is possible that these factors may have affected the prevalence of the themes. Finally, this systematic review focused on evidence from European DR projects, and our thematic synthesis drew particularly on evidence from UK projects. This was due to the greater focus on customer perspectives in the UK projects, which may be due to the relatively advanced DR markets in the UK compared to most other European countries (European Commission Citation2016). This is noteworthy given that there are some concerns about the generalizability of qualitative data and that associated modes of synthesis may detach findings from their original context (Britten et al. Citation2002). Notwithstanding these limitations, this review provides new insights for the development of customer-oriented DR and other smart grid services.

Conclusion

This systematic review and thematic synthesis of customers’ experiences and attitudes toward DR identified three main themes and 10 subthemes related to the uptake of and participation in DR programs. The results highlight the value of social interaction and support as well as the importance of customer education and easily interpretable information. These findings have some potentially important implications for the development and implementation of DR programs. For customers to become active participants within their networks, the electric utility industry must re-evaluate the traditional idea of customer relationships. A relationship based on purely top-down management strategies and unidirectional communication is unlikely to foster customer engagement and promote meaningful behavior change. Instead, more focus should be placed on building a partnership-like relationship and integrating customer perspectives into DR. Ultimately, it is the actions of the customers that will determine the success of DR and focusing on factors that enable their participation will therefore help to create a successful program and allow for greater co-creation of value. To this end, it is up the service providers to equip customers with the necessary knowledge, skills, and technologies to participate in DR, as well as to incentivize them to do so.

The results of our review offer insights into how these needs may be met, but the findings reported here are by no means exhaustive, nor are they necessarily generalizable to all contexts. Therefore, more research investigating customer attitudes toward DR in various cultural and socioeconomic contexts is needed. It is particularly important to identify and understand the needs and challenges of low-income households and those at the greatest risk of energy poverty, as these households may face disproportionate barriers and challenges preventing them from accessing and benefitting from DR.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Peter Jones and the anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ali, F., M. Ashfaq, S. Begum, and A. Ali. 2020. “How ‘Green’ Thinking and Altruism Translate into Purchasing Intentions for Electronics Products: The Intrinsic-extrinsic Motivation Mechanism.” Sustainable Production and Consumption 24: 281–291. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2020.07.013.

- Ali, M., K. Prakash, M. Hossain, and H. Pota. 2021. “Intelligent Energy Management: Evolving Developments, Current Challenges, and Research Directions for Sustainable Future.” Journal of Cleaner Production 314: 127904. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127904.

- AnyPLACE Consortium 2018a. Environmental and Societal Impacts Assessment: Deliverable 2.2. Brussels: European Union Publications Office. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/646580/results.

- AnyPLACE Consortium 2018b. Field Trial: Deliverable 8.2. Brussels: European Union Publications Office. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/646580/results.

- AnyPLACE Consortium 2018c. Policy and Regulatory Recommendations: Deliverable 1.2. Brussels: European Union Publications Office. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/646580/results.

- Balta-Ozkan, N., R. Davidson, M. Bicket, and L. Whitmarsh. 2013. “Social Barriers to the Adoption of Smart Homes.” Energy Policy 63: 363–374. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.08.043.

- Bartusch, C., and K. Alvehag. 2014. “Further Exploring the Potential of Residential Demand Response Programs in Electricity Distribution.” Applied Energy 125: 39–59. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.03.054.

- Bellefontaine, S., and C. Lee. 2014. “Between Black and White: Examining Grey Literature in Meta-analyses of Psychological Research.” Journal of Child and Family Studies 23 (8): 1378–1388. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9795-1.

- Berka, A., and E. Creamer. 2018. “Taking Stock of the Local Impacts of Community Owned Renewable Energy: A Review and Research Agenda.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 82: 3400–3419. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.10.050.

- Billanes, J., and P. Enevoldsen. 2021. “A Critical Analysis of Ten Influential Factors to Energy Technology Acceptance and Adoption.” Energy Reports 7: 6899–6907. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2021.09.118.

- Bolderdijk, J., L. Steg, E. Geller, P. Lehman, and T. Postmes. 2013. “Comparing the Effectiveness of Monetary Versus Moral Motives in Environmental Campaigning.” Nature Climate Change 3 (4): 413–416. doi:10.1038/nclimate1767.

- Bolle, F., and P. Otto. 2010. “A Price Is a Signal: On Intrinsic Motivation, Crowding-out, and Crowding-in.” Kyklos 63 (1): 9–22. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6435.2010.00458.x.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, T., B. Fung, F. Iqbal, and B. Shah. 2018. “Security and Privacy Challenges in Smart Cities.” Sustainable Cities and Society 39: 499–507. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2018.02.039.

- Braunholtz-Speight, T., C. McLachlan, S. Mander, M. Hannon, J. Hardy, I. Cairns, M. Sharmina, and E. Manderson. 2021. “The Long Term Future for Community Energy in Great Britain: A Co-created Vision of a Thriving Sector and Steps Towards Realising It.” Energy Research & Social Science 78: 102044. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2021.102044.

- Britten, N., R. Campbell, C. Pope, J. Donovan, M. Morgan, and R. Pill. 2002. “Using Meta Ethnography to Synthesise Qualitative Research: A Worked Example.” Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 7 (4): 209–215. doi:10.1258/135581902320432732.

- Broska, L. 2021. “It’s All About Community: On the Interplay of Social Capital, Social Needs, and Environmental Concern in Sustainable Community Action.” Energy Research & Social Science 79: 102165. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2021.102165.

- Cai, Z., X. Fan, and J. Du. 2017. “Gender and Attitudes Toward Technology Use: A Meta-analysis.” Computers & Education 105: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2016.11.003.

- Choi, D., and K. Johnson. 2019. “Influences of Environmental and Hedonic Motivations on Intention to Purchase Green Products: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior.” Sustainable Production and Consumption 18: 145–155. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2019.02.001.

- Christensen, T., F. Friis, S. Bettin, W. Throndsen, M. Ornetzeder, T. Skjølsvold, and M. Ryghaug. 2020. “The Role of Competences, Engagement, and Devices in Configuring the Impact of Prices in Energy Demand Response: Findings from Three Smart Energy Pilots with Households.” Energy Policy 137: 111142. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111142.

- Customer-Led Network Revolution (CLNR). 2013. Project Lessons Learned from Trial Recruitment: Customer Led Network Revolution Trials. Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: CLNR. http://www.networkrevolution.co.uk/resources/project-library.

- Customer-Led Network Revolution (CLNR). 2014. Durham University Social Science Research: March 2014 Report. Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: CLNR. http://www.networkrevolution.co.uk/resources/project-library.

- Darby, S. 2008. “Energy Feedback in Buildings: Improving the Infrastructure for Demand Reduction.” Building Research & Information 36 (5): 499–508. doi:10.1080/09613210802028428.

- Darby, S., and E. McKenna. 2012. “Social Implications of Residential Demand Response in Cool Temperate Climates.” Energy Policy 49: 759–769. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2012.07.026.

- Decullier, E., V. Lhéritier, and F. Chapuis. 2005. “Fate of Biomedical Research Protocols and Publication Bias in France: Retrospective Cohort Study.” The BMJ 331 (7507): 19–22. doi:10.1136/bmj.38488.385995.8F.

- de Moura, P., C. Cavalli, and C. da Rocha. 2019. “Interface Design for In-home Displays.” Sustainable Production and Consumption 18: 130–144. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2018.11.003.

- Dütschke, E., and A. Paetz. 2013. “Dynamic Electricity Pricing: Which Programs Do Consumers Prefer?” Energy Policy 59: 226–234. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.03.025.

- Dwan, K., D. Altman, J. Arnaiz, J. Bloom, A.-W. Chan, E. Cronin, E. Decullier, et al. 2008. “Systematic Review of the Empirical Evidence of Study Publication Bias and Outcome Reporting Bias.” PLoS One 3 (8): e3081. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003081.

- E-balance Consortium. 2017. Validation of the Proposed Use Cases and Business Models: Deliverable 2.5. Frankfurt: E-balance Consortium. http://ebalance-project.eu/deliverables.

- Ehrenhard, M., B. Kijl, and L. Nieuwenhuis. 2014. “Market Adoption Barriers of Multi-stakeholder Technology: Smart Homes for the Aging Population.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 89: 306–315. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2014.08.002.

- Ellabban, O., and H. Abu-Rub. 2016. “Smart Grid Customers’ Acceptance and Engagement: An Overview.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 65: 1285–1298. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.06.021.

- European Commission 2011. Smart Grid Projects in Europe: Lessons Learned and Current Developments. Brussels: European Commission. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC65215.

- European Commission 2013. Communication from the Commission: Delivering the Internal Electricity Market and Making the Most of Public Intervention. Brussels: European Commission. https://energy.ec.europa.eu/delivering-internal-electricity-market-and-making-most-public-intervention-com2013-7243-0_en.

- European Commission 2016. Demand Response Status in EU Member States. Brussels: European Commission. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC101191.

- European Commission 2017. Smart Grid Projects Outlook. Brussels: European Commission. https://ses.jrc.ec.europa.eu/smart-grids-observatory.

- European Commission 2020. 2030 Climate Target Plan. Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/eu-climate-action/2030_ctp_en.

- European Commission 2021. Annex to the Commission Recommendation on Energy Efficiency First: From Principles to Practice – Guidelines and Examples for Its Implementation in Decision-making in the Energy Sector and Beyond. Brussels: European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reco/2021/1749/oj.

- Flex4Grid Consortium 2018. Validation of Second Pilot: Deliverable 6.6. Brussels: European Union Publications Office. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/646428/results.

- FLEXICIENCY Consortium 2018. Results Achieved in the Swedish Demonstration: Deliverable 8.2. Brussels: European Union Publications Office. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/646482/results.

- FLEXICIENCY Consortium 2019a. Cross-case Analysis of the Results from the Demonstrations: Deliverable 3.2. Brussels: European Union Publications Office. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/646482/results.

- FLEXICIENCY Consortium 2019b. Report on the Results Achieved in the Italian Demonstrations: Deliverable 5.2. Brussels: European Union Publications Office. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/646482/results.

- Frey, B., and R. Jegen. 2001. “Motivation Crowding Theory.” Journal of Economic Surveys 15 (5): 589–611. doi:10.1111/1467-6419.00150.

- García-Holgado, A., S. Marcos-Pablos, and F. García-Peñalvo. 2020. “Guidelines for Performing Systematic Research Projects Reviews.” International Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelligence 6 (2): 9–144. doi:10.9781/ijimai.2020.05.005.

- Godin, K., J. Stapleton, S. Kirkpatrick, R. Hanning, and S. Leatherdale. 2015. “Applying Systematic Review Search Methods to the Grey Literature: A Case Study Examining Guidelines for School-based Breakfast Programs in Canada.” Systematic Reviews 4 (1): 138. doi:10.1186/s13643-015-0125-0.

- Gouveia, J., J. Seixas, and G. Long. 2018. “Mining Households’ Energy Data to Disclose Fuel Poverty: Lessons for Southern Europe.” Journal of Cleaner Production 178: 534–550. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.021.

- Gram-Hanssen, K. 2009. “Standby Consumption in Households Analyzed with a Practice Theory Approach.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 14 (1): 150–165. doi:10.1111/j.1530-9290.2009.00194.x.

- Gyamfi, S., and S. Krumdieck. 2011. “Price, Environment and Security: Exploring Multi-modal Motivation in Voluntary Residential Peak Demand Response.” Energy Policy 39 (5): 2993–3004. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2011.03.012.

- Haddaway, N., and H. Bayliss. 2015. “Shades of Grey: Two Forms of Grey Literature Important for Reviews in Conservation.” Biological Conservation 191: 827–829. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2015.08.018.

- Hafner, R., S. Pahl, R. Jones, and A. Fuertes. 2020. “Energy Use in Social Housing Residents in the UK and Recommendations for Developing Energy Behaviour Change Interventions.” Journal of Cleaner Production 251: 119643. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119643.

- Handgraaf, M., M. Van Lidth de Jeude, and K. Appelt. 2013. “Public Praise vs. Private Pay: Effects of Rewards on Energy Conservation in the Workplace.” Ecological Economics 86: 86–92. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.11.008.

- Heylen, E., D. Papadaskalopoulos, I. Konstantelos, and G. Strbac. 2020. “Dynamic Modelling of Consumers’ Inconvenience Associated with Demand Flexibility Potentials.” Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 21: 100298. doi:10.1016/j.segan.2019.100298.

- Hobman, E., E. Frederiks, K. Stenner, and S. Meikle. 2016. “Uptake and Usage of Cost-reflective Electricity Pricing: Insights from Psychology and Behavioural Economics.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 57: 455–467. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.12.144.

- Honebein, P., R. Cammarano, and C. Boice. 2011. “Building a Social Roadmap for the Smart Grid.” The Electricity Journal 24 (4): 78–85. doi:10.1016/j.tej.2011.03.015.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). 2020. Renewables 2020. Paris: IEA. https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2020.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2018. Global Warming of 1.5 °C: Summary for Policymakers. Geneva: IPCC. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm.

- Juntunen, J. 2014. “Domestication Pathways of Small-scale Renewable Energy Technologies.” Sustainability: Science, Practice, and Policy 10 (2): 4–18. doi:10.1080/15487733.2014.11908130.

- Karjalainen, S. 2013. “Should It Be Automatic or Manual: The Occupant’s Perspective on the Design of Domestic Control Systems.” Energy and Buildings 65: 119–126. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2013.05.043.

- Kessels, K., C. Kraan, L. Karg, S. Maggiore, P. Valkering, and E. Laes. 2016. “Fostering Residential Demand Response Through Dynamic Pricing Schemes: A Behavioural Review of Smart Grid Pilots in Europe.” Sustainability 8 (9): 929. doi:10.3390/su8090929.

- Kim, J., and A. Shcherbakova. 2011. “Common Failures of Demand Response.” Energy 36 (2): 873–880. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2010.12.027.

- Lawrence, A., J. Houghton, J. Thomas, and P. Weldon. 2014. Where Is the Evidence: Realising the Value of Grey Literature for Public Policy and Practice. Swinburne: Swinburne Institute for Social Research. doi:10.4225/50/5580b1e02daf9.

- Li, W., T. Yigitcanlar, I. Erol, and A. Liu. 2021. “Motivations, Barriers and Risks of Smart Home Adoption: From Systematic Literature Review to Conceptual Framework.” Energy Research & Social Science 80: 102211. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2021.102211.

- Lopes, M., C. Henggeler Antunes, K. Janda, P. Peixoto, and N. Martins. 2016. “The Potential of Energy Behaviours in a Smart(er) Grid: Policy Implications from a Portuguese Exploratory Study.” Energy Policy 90: 233–245. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2015.12.014.

- Mahood, Q., D. Van Eerd, and E. Irvin. 2014. “Searching for Grey Literature for Systematic Reviews: Challenges and Benefits.” Research Synthesis Methods 5 (3): 221–234. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1106.

- Marikyan, D., S. Papagiannidis, and E. Alamanos. 2019. “A Systematic Review of the Smart Home Literature: A User Perspective.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 138: 139–154. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2018.08.015.

- Martin, K., A. Borah, and R. Palmatier. 2017. “Data Privacy: Effects on Customer and Firm Performance.” Journal of Marketing 81 (1): 36–58. doi:10.1509/jm.15.0497.

- Mela, H., J. Peltomaa, M. Salo, K. Mäkinen, and M. Hildén. 2018. “Framing Smart Meter Feedback in Relation to Practice Theory.” Sustainability 10 (10): 3553. doi:10.3390/su10103553.

- Mi, L., X. Gan, Y. Sun, T. Lv, L. Qiao, and T. Xu. 2021. “Effects of Monetary and Nonmonetary Interventions on Energy Conservation: A Meta-analysis of Experimental Studies.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 149: 111342. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.111342.

- Moreno-Munoz, A., F. Bellido-Outeirino, P. Siano, and M. Gomez-Nieto. 2016. “Mobile Social Media for Smart Grids Customer Engagement: Emerging Trends and Challenges.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 53: 1611A–1616A. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.09.077.

- Nicholls, L., and Y. Strengers. 2015. “Peak Demand and the ‘Family Peak’ Period in Australia: Understanding Practice (In)Flexibility in Households with Children.” Energy Research & Social Science 9: 116–124. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2015.08.018.

- Nicolson, M., M. Fell, and G. Huebner. 2018. “Consumer Demand for Time of Use Electricity Tariffs: A Systematized Review of the Empirical Evidence.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 97: 276–289. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2018.08.040.

- Neighbourhood Oriented Brokerage ELectricity and monitoring system (NOBEL). 2011. Evaluation Plan: Deliverable 7.1. Brussels: European Union Publications Office. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/247926/reporting.

- Neighbourhood Oriented Brokerage ELectricity and monitoring system (NOBEL). 2012. Evaluation and Assessment: Deliverable 7.3. Brussels: European Union Publications Office. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/247926/reporting.

- Paetz, A., E. Dütschke, and W. Fichtner. 2012. “Smart Homes as a Means to Sustainable Energy Consumption: A Study of Consumer Perceptions.” Journal of Consumer Policy 35 (1): 23–41. doi:10.1007/s10603-011-9177-2.

- Paez, A. 2017. “Gray Literature: An Important Resource in Systematic Reviews.” Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine 10 (3): 233–240. doi:10.1111/jebm.12266.

- Palm, J., and M. Tengvard. 2011. “Motives for and Barriers to Household Adoption of Small-scale Production of Electricity: Examples from Sweden.” Sustainability: Science, Practice, and Policy 7 (1): 6–15. doi:10.1080/15487733.2011.11908061.

- Parrish, B., P. Heptonstall, R. Gross, and B. Sovacool. 2020. “A Systematic Review of Motivations, Enablers and Barriers for Consumer Engagement with Residential Demand Response.” Energy Policy 138: 111221. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111221.

- Perri, C., C. Giglio, and V. Corvello. 2020. “Smart Users for Smart Technologies: Investigating the Intention to Adopt Smart Energy Consumption Behaviors.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 155: 119991. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119991.

- Piggott-McKellar, A., K. McNamara, P. Nunn, and J. Watson. 2019. “What Are the Barriers to Successful Community-based Climate Change Adaptation? A Review of Grey Literature.” Local Environment 24 (4): 374–390. doi:10.1080/13549839.2019.1580688.

- Rajaee, M., S. Hoseini, and I. Malekmohammadi. 2019. “Proposing a Socio-Psychological Model for Adopting Green Building Technologies: A Case Study from Iran.” Sustainable Cities and Society 45: 657–668. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2018.12.007.

- Riesz, J., and M. Milligan. 2015. “Designing Electricity Markets for a High Penetration of Variable Renewables.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Energy and Environment 4 (3): 279–289. doi:10.1002/wene.137.

- Safdar, M., G. Hussain, and M. Lehtonen. 2019. “Costs of Demand Response from Residential Customers’ Perspective.” Energies 12 (9): 1617. doi:10.3390/en12091617.

- Sanguinetti, A., B. Karlin, and R. Ford. 2018. “Understanding the Path to Smart Home Adoption: Segmenting and Describing Consumers Across the Innovation-decision Process.” Energy Research & Social Science 46: 274–283. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2018.08.002.

- Savelli, I., and T. Morstyn. 2021. “Better Together: Harnessing Social Relationships in Smart Energy Communities.” Energy Research & Social Science 78: 102125. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2021.102125.

- Scottish and Southern Electricity Networks (SSEN). 2018a. Solent Achieving Value from Efficiency (SAVE): PPR June 2018. Perth: SSEN. https://save-project.co.uk/reports-and-presentations/.

- Scottish and Southern Electricity Networks (SSEN). 2018b. Solent Achieving Value from Efficiency (SAVE): SDRC 3.2 Improve Customer Engagement. Perth: SSEN. https://save-project.co.uk/reports-and-presentations/.

- Scottish and Southern Electricity Networks (SSEN). 2019. Solent Achieving Value from Efficiency (SAVE): SDRC 8.8 Community Coaching Trial Report. Perth: SSEN. https://save-project.co.uk/reports-and-presentations/.

- Smart Energy Demand Coalition (SEDC) 2017. Explicit Demand Response in Europe: Mapping the Markets 2017. Brussels: SEDC. https://smarten.eu/explicit-demand-response-in-europe-mapping-the-markets-2017.

- Shove, E. 2010. “Beyond the ABC: Climate Change Policy and Theories of Social Change.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 42 (6): 1273–1285. doi:10.1068/a42282.

- Siano, P. 2014. “Demand Response and Smart Grids: A Survey.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 30: 461–478. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2013.10.022.

- SMART-UP Consortium 2018a. Final Report WP6: Deliverable 6.4. Brussels: European Union Publications Office. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/649669/results.

- SMART-UP Consortium 2018b. Final Status of Pilot Activities: Deliverable 5.4. Brussels: European Union Publications Office. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/649669/results.

- SMART-UP Consortium 2018c. Impact Report: Deliverable 7.8. Brussels: European Union Publications Office. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/649669/results.

- SMART-UP Consortium 2018d. Report on the Support to Households: Deliverable 5.3. Brussels: European Union Publications Office. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/649669/results.

- Sorrell, S. 2007. “Improving the Evidence Base for Energy Policy: The Role of Systematic Reviews.” Energy Policy 35 (3): 1858–1871. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2006.06.008.