ABSTRACT

‘Healthy’ and ‘ethical’ food is one of the fastest-growing food trends around the world. Yet scholars in this journal have shown that what this means in many territories tends to be dominated by Western-centric concepts. They call for the need to decenter the dominant Euro-American and Anglo-centric food scholarship in order to throw light on these processes. To better understand food globalization, one must consider how regional history, culture, economics, and politics foster a complex dynamic of global-local and West-East flows. Aligning with these concerns, we analyze food packages from China marketed at a rapidly growing health and ethical food market. Using an in-depth qualitative method, Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis, we examine the discursive and material power of healthy and ethical food products as these are communicated through packaging designs, showing how these carry ideas, value, and identities. We explore how this might be understood in the context of where such designs target an emerging Chinese middle class, concerned about food integrity, but also who seek out distinction and modern cosmopolitanism. We ask how the ideas carried by the packages might shape and steer local understandings of healthy and ethical food.

Introduction

It has been argued that food has shaped human society, having a great impact on human health, culture diversity, economy, and politics (De St. Maurice Citation2013; Pilcher Citation2017). And given the global industry in food production, food trades, food products, and styles, it has been argued that food is to be understood through the lens of globalization and also that globalization is itself to be understood through the lens of food (Phillips Citation2006). The central importance of this matter for food studies was signaled in a special edition of this journal called “Transecting ‘healthy’ and ‘sustainable’ food in the Asia Pacific” (Montefrio and Wilk Citation2020). The special urged for more work to shift the Euro-American dominance of food scholarship. Of particular relevance for our present study was its interest in how notions of healthy and ethical foods have become increasingly globalized, where complex of flows between global-local, West-East, regional history, culture, economic, and politics, have contributed to creating unique local accents in what constitute the idea of healthy or ethical foods (Montefrio et al. Citation2020; Chera Citation2020; Ho Citation2020).

In this paper, we use a Multimodal Critical Discourse Analytical Approach (MCDA) (Ledin and Machin Citation2018) to look at a sample from a corpus of healthy and ethical food packaging collected in China, which comprises the world’s largest growing market for these kinds of branded products (IFOAM Citation2009; Zhou Citation2008). We are interested not so much in what is ‘healthy’ or ‘ethical,’ per se, but in how these ideas are communicated in a range of buzzwords, along with the iconographies and packaging styles, found typically, for example in Europe, the US, and Australia and now more commonly in China. While healthy and ethical food are parallel concepts, marketing very often merges the two. Those positioned as having some kind of health benefit often also combine ethical consumption ideas, such as ‘natural,’ ‘organic,’ ‘sustainable,’ ‘local,’ or ‘recyclable’ (Eriksson and Machin Citation2020). This merging and blurring is of interest to us in this paper.

It has been observed that in Western societies food marketing has colonized, shaped and distorted understandings of healthy and ethical eating, even distracting from the nature of these things (Johnston and Baumann Citation2010; Eriksson and Machin Citation2020). But what is the case in China? Following Montefrio and Wilk (Citation2020), we critically examine the discursive and material power of these healthy and ethical food products. In other words, how do these shape and steer how consumers may come to understand these issues? How are the buzzwords and iconography of this Western food marketing become deployed on products in China, but in ways that have local inflections. The methodology we use is a form of semiotics, which has been shown to be highly useful for this kind of closer analysis, allowing us to look in detail at how food marketers can load their products with ideas and values which speak to their market.

The attention to such interactions of notions based on complex configurations of culture, economics, and politics in the global context, has been identified as a neglected area of research in food studies (Montefrio and Wilk Citation2020). In this paper, we seek to contribute to this project in the case of China.

MCDA is a form of communications research. Communications scholars have sought to document how Western media and products impact local cultures (Lechner and Boli Citation2005; Dreher, Gaston, and Martens Citation2008), bringing new formats and styles as well as identities, ideas, and values. It has also been argued that globalization and localization exist embedded in all kinds of media and consumer culture around the planet (Aiello and Pauwels Citation2014). But here communication must be thought of not just in terms of texts, photographs, images, and video, but in the broader strategies deployed by global branding and localization. This could include attention to the design of coffee shops in the fashion of Starbucks’ through choices of furnishings (Aiello and Dickinson Citation2014) or to how typeface, color, and layout are progressively more systematically harnessed in media design (Chen and Machin Citation2014) all leading to a cross-national visual familiarity, yet with local accents (Pristed Nelson and Faber Citation2014). For Aiello and Pauwels (Citation2014) it was through attention to such details that we can provide a clearer empirically based understanding of communication taking place in concrete localized situations, rather than leaning on theoretical notions of ‘globalization and localization’ or ‘culture-scapes’ (Aiello and Pauwels Citation2014). In this paper MCDA allows us to take the step of looking closely at foods presented as ‘healthy and ethical’ in China to consider how marketers harness aspects of language and design to load their products with ideas and values. In so doing, ultimately following Montefrio and Wilk (Citation2020), we ask what power do the discourses they communicate have to shape the landscape of what healthy and ethical eating mean.

Marketing healthy and ethical food in Western societies

In Western societies there has been a growing focus on health, promoted in part by governments concerned with the economic costs of diet-related illnesses (Patterson and Johnston Citation2012). There has been corresponding increasing interest in eating healthily by the public, met by widely expanding products available in stores and restaurants (Olayanju Citation2019). Healthy and ethical food is one of the biggest global growth areas in food sales (Olayanju Citation2019; Montefrio and Wilk Citation2020), and in China, the focus of this paper, represents the highest dollar growth in food sales (IFOAM Citation2009; Zhou Citation2008).

Nutritional research shows that beyond eating a balanced diet and avoiding processed foods it is not possible to define specific ingredients and proportions of food items nor ingredients to eat healthily (De Ridder et al. Citation2017). The disagreements and uncertainties within nutrition research however ‘tend to be conceded from, or misrepresented to, the lay public’ (Scrinis Citation2013, 6). It is also known that ideas of healthy food can differ greatly across socio-economic groups (Johnston and Baumann Citation2010) and across different countries (Ferguson Citation2010). Current nutrition research, what the public, dietary advice, policy and food marketing refer their nutritional knowledge to, however, tends to be decontextualized and simplified, and therefore undermines other ways of knowing and engaging with food that reflect these differences (Scrinis Citation2013).

Food marketing has developed a range of products that carry an array of buzzwords to signify “healthiness,” including “low fat,” “low carb,” “healthy grains,” “organic,” “energy boosting,” “source of protein,” “superfoods,” “raw,” “plant based,” “low calorie,” “lactose free,” etc. These buzzwords can be highly contradictory and confusing for consumers (O’Neill and Silver Citation2017) and tend to be combined in different ways to form what has been called a “hodgepodge” of healthy associations where there is no logic to the combinations and no clear sense of what each actually does (Lewis Citation2008). In fact, research in nutrition studies shows that these buzzwords can be misleading in regard to the actual nutritional content of the product. For example, a product labeled as “no added sugar” can have high actual sugar content through added fruit concentrates (Siipi Citation2012). A product labeled “high protein” can contain high amounts of trans fat and sugar (Chen and Eriksson Citation2019). The buzzwords “multi-grains,” “high fiber” and “roughage” are promoted by the agri-food industry as beneficial, yet nutritionists show that there is no evidence for this (Polan Citation2008; Monastyrsky Citation2005). Such terms can create a “halo effect” (Fernan, Schuldt, and Niederdeppe Citation2017), which leads consumers to mistakenly assume that they are buying something healthy (Iles, Nan, and Verrill Citation2017). Such use of buzzwords reflect what Scrinis (Citation2013) calls ‘nutritionism’ and ‘nutritional reductionism,’ a reductive focus on the nutrient composition of food as the means for understanding the complexity of food to bodily health. This has serves as a powerful frameworks for transforming nutrients and nutritional knowledge into marketable food products and commodify food production and consumption (ibid).

The idea of healthy food also merges and fuses with notions of ethical eating, where we find buzzwords like: “sustainable,” “hand-made,” “Fairtrade,” “organic,” “local” (Johnston and Baumann Citation2010), also often forming part of the overall hodgepodge of qualities of foods carrying healthy buzzwords (Eriksson and Machin Citation2020). Yet such products often gloss over the complexities of things like food sourcing, transportation, manufacture, packaging processes, marketing, global trade structures, and waste disposal (Eriksson and Machin Citation2020). Shugart (Citation2014) argues that ethical buzzwords must, in part, be understood through how they address middle-class consumers who seek tasteful alternatives to anonymous corporate culture and mass production, related to ideas of “slowness,” “wholeness” and “authenticity.”

These products can also bring a sense of morality (Low, Davenport, and Carrigan Citation2005). They allow consumers to act in relation to their concerns for environmental and social injustices through what has been termed “political consumerism” – something available to those with spending power (Banet-Weisser Citation2012). One concern here is that marketing may ultimately colonize and shape our sense of health and acting ethically, simplifying complex issues, presenting market-friendly ‘solutions’ packaged in attractive ways (Forsyth and Young Citation2007, 29). Such packages make saving your body or the planet seem simple, chic, and tasteful (Ledin and Machin Citation2020a). Scholars have shown, the importance for food studies to learn more about how notions of commodified ethical food and political consumerism in Pacific Asia (Khalikova Citation2020; Lin Citation2020; Montefrio et al. Citation2020). Given such concerns, it is of interest to consider how such branded products take form in China.

Healthy and ethical food consumption in China

Economic and social reforms within China since the 1980s have resulted in significant changes in the food industry, food culture, and food consumption patterns (Riccioli et al. Citation2020; Veeck and Veeck Citation2000). This includes the increasing presence of international retail chains and availability of formerly scarce imported products such as processed, frozen, pre-prepared foods and dairy items, and has led to increases in fats, sugars, and grains in diets. It has been shown that the demand for Western-style and imported foods has mainly been by the newly emerged urban middle class who have the spending power (Grunert et al. Citation2011). This fits patterns observed for the Pacific Asia region in general where such consumption is a more elite activity (Khalikova Citation2020; Lin Citation2020; Montefrio et al. Citation2020).

Although not a monolithic group, scholars identify a number of typical patterns characterizing the Chinese middle class. They seek good education for their children, property investment, but also status and cultural capital, often realized in consumption (Guo Citation2017; Goodman Citation2013). This consumption culture has been linked to values of aspiration, empowerment, having “good taste,” and, importantly, being modern and cosmopolitan (Mao Citation2018; Goodman Citation2013). What is perceived as Western-style, and imported, products, such as clothing, cars, furniture, popular and high culture, as well as food, are part of this, bringing new possibilities for the expression of personal desires, moral autonomy, and leisure (Guo Citation2017; Xu Citation2007). It has been argued that these combine with broader Western ideas and values relating to individualism and a more self-centered morality (Yan Citation2009). These depart from more traditional local notions of social responsibility, knowing one’s position and restraint, which have a character rooted in Confucianism, Taoism, Maoism, and more recent interactions with international cultures (Lu Citation1998; Elfick Citation2011). Such ideas and values having been steered by more recent local political initiatives as part of stimulating the economy of which the new middle class are themselves a result (Zhang Citation2020; Tomba Citation2014; Goodman Citation2013).

The demand for imported products also relates to a series of high-profile food safety scares involving misleading labeling along with growing awareness of pollution (Riccioli et al. Citation2020; Tong et al. Citation2020). This has led to a surge in organic/green/eco/ethical food consumption among those who can afford high prices (Chen and Lobo Citation2012). The “Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability” (LOHAS) trend has been growing in popularity among middle-class consumers (Chen and Lobo Citation2012). The Chinese organic food market has grown faster than the world average (IFOAM Citation2009) and in 2008, China was the fourth largest organic market in the world (Zhou Citation2008).

This turn to eco foods and concern about polluted land has also been related to broader shifting attitudes to nature and the countryside. In the mid-2000s, rural areas were associated with “poverty, ignorance, insanitation, underdevelopment, backwardness, barbarism [and] stupidity” (Su Citation2010, 1439). But this is changing to where the middle classes engage in hiking, visiting rural areas, and take day trips to experience the flourishing organic farms appearing around the main cities (Brunner Citation2019). These farms and other rural tourism sites provide a romanticized and idealized version of countryside life (Martin, Lewis, and Sinclair Citation2013; Zou Citation2005).

The analysis, which follows allows us to begin to throw some light on how food companies exploit these historical shifts, using packaging designs to sell ideas of healthy and ethical food. It is here that we can think about what Montefrio and Wilk (Citation2020) call the discursive power embedded in these material objects. We can also think about what Halawa and Parasecoli (Citation2021) describe as an intense of designing and codification of foodscape, which allows the same shared repository elements to be assembled in very different combinations to create globally repeating forms of urban locality.While we may in part see such designs as being a way that market needs are met, we can, from a communications research perspective also ask what set of ideas they carry, naturalize, and legitimize, about how we take care of ourselves and the planet (Eriksson and Machin Citation2020) as well broader social and political issues (Montefrio and Wilk Citation2020).

Theory and methods

The analysis draws on tools and concepts from Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis (MCDA) (Machin and Mayr Citation2012; Ledin and Machin Citation2018) and Social Semiotics (Van Leeuwen Citation2005; Kress and Van Leeuwen Citation2006). MCDA is aligned with the field of critical discourse analysis (CDA). CDA is a form of qualitative critical linguistic analysis interested in how language can shape how events, processes, and persons are represented in ways that serve particular ideological aims (Fairclough Citation1992). The assumption is that language use is never neutral but loaded with specific ideological interests. Language is seen as a repertoire of possible choices, each of which has the “meaning potential” (Halliday Citation1978) to be deployed, to communicate specific kinds of meanings. The analysis looks carefully at these choices. For example, we may ask what kind of identity category is chosen from a range of possible choices to describe a person: their nationality, ethnicity, occupation, parental status, bodily shape, gender, etc. In CDA, these are thought of as choices, which direct how a person is represented and evaluated. Ultimately, CDA is interested in the role of language in the functioning of social and political life, (Flowerdew and Richardson Citation2017). Language choices communicate broader discourses (Foucault Citation1972) which lay out and evaluate how we understand processes, causalities, how we plan and organize.

In MCDA, it has been shown that it is possible to carry out this kind of close critical analysis not just of language, but all forms of choices in communication, which may combine language, images, sounds, textures, video, etc, (Machin and Mayr Citation2012). In MCDA, we also approach choices in design in terms of their meaning potentials and how they come to shape representations of things, persons, and processes (Ledin and Machin Citation2018). We can attend to choices in the weight or height of fonts, the saturation or dilution of colors, the roughness or smoothness of surfaces, the roundness or angularity of forms. In MCDA scholars have presented inventories of choices (Van Leeuwen Citation2005; Kress Citation2010; Ledin and Machin Citation2020b). These have already been productively used to carry out critical analyses of packing (Wagner Citation2015; Chen and Eriksson Citation2019; Ledin and Machin Citation2020a; Machin and Cobley Citation2020; Andersson Citation2020). Importantly, such choices, which compose the material forms of packaging have significant discursive power as they form material objects, which become incorporated into everyday lives, found in our shops, kitchens, or sat on our office desk.

Practically MCDA presents a closer analysis of a smaller number of examples, usually taken from a larger corpus (Machin and Mayr Citation2012). Its value lies in the closer detail and thoroughness of analysis. In this case, our sample of 100 food products was collected following Pink’s visual ethnography (Pink Citation2013). We purchased items that we had seen consumed by professional, higher income, people who would fit the socioeconomic classification for the new middle classes (Goodman Citation2013; Mao Citation2018). These were bought in stores in 3 major cities: Shanghai, Beijing, and Hangzhou. The products included snacks, dairy, protein supplements, bread, cereals, and drinks.

The analysis is comprised of two steps. The first stage was carried out using Van Dijk’s (Citation2009) semantic macro-analysis to look for the main themes in the data. We used open coding and axial coding to look for major categories and to understand the relationships between the subcategories (Charmaz Citation2006). In this paper, we present four of these themes. 1. The presence of buzzwords and iconography common to health and ethical foods in many Western societies; 2. A highly romanticized view of nature, which scholars have argued marks a shift in China; 3. There is an almost ‘overdetermined’ sense of order and regulation in these designs. 4. We find representations of a very specific kind of Chinese middle-class nuclear family. The second stage is what we present below where we carry out the closer analysis to show how these themes are realized on a sample of packages, showing how more local accents blend with those which are more Western.

The iconography of healthy and ethical food

The packages in our corpus carry the buzzwords and iconography found in Western-style healthy and ethical food marketing. These are either newer to the Chinese market or more established things, such as nuts and fruit, presented in newly commodified ways. What becomes highly relevant, we show in the following sections, is how these are represented and integrated into the designs, which allow the communication of specific ideas, values, and identities.

On the daily nuts package () we find ingredients such as “cranberries,” “blueberries,” “walnuts,” “almonds,” etc. These are presented in language, in both Mandarin Chinese and English, the latter helping to communicate “international” and “modern” (Hsu Citation2008).

On the cereal package () we find reference to other typical Western buzzwords and iconography. On the front, we see “5 grains,” ingredients still rarer in China, and introducing the idea of “fiber” and “roughage” as healthy. On the side panel, there is a reference to fruit and nuts, which the consumer can themselves add, bringing connotations that this product aligns with a healthy diet. On the cereal box, we also find the highly ambiguous concept of “nutritious” above the fruit on the side of the cereal box.

Nutritional researchers (cf. Siipi Citation2012) have observed that this array of buzzwords and buzz ingredients, can be entirely unrelated to actually eat healthily, or acting in ways that address complex environmental or ethical issues (Low, Davenport, and Carrigan Citation2005). But, of course, these are not just buzzwords and buzz things but represent tools and concepts for managing lives, for dealing with more abstract matters to which they give form and shape – particularly in the codified and commodified form they take in these designs. This is the discursive power that they carry. They lay out ways of acting and being. They present a kind of tick-list for taking care of our bodies and acting in moral ways. Most importantly, as Banet-Weiser (Citation2012) argues, this appears as simple, efficient, easy.

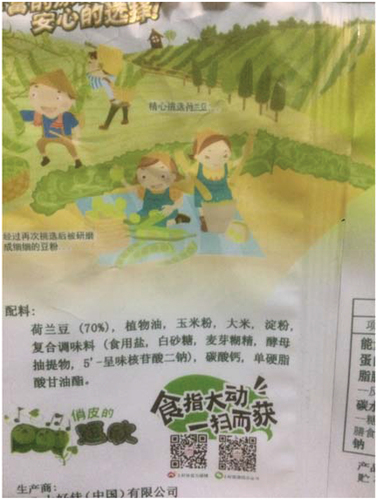

We see other buzzwords and buzz ingredients in other examples. The pea snack () is a typical healthy and ethical style product that can be found in Western stores. Here, ingredients like pulses, wholes grains, and peas have changed from being low-status foods to connoting simplicity, stripped-back, unrefined, and natural par excellence, even when they sit in snacks high in sugar, salt, and fats (Eriksson and Machin Citation2020). On this package, we find other buzzwords: “14% protein,” “7% rich in fiber,” “baked not fried,” and “0 g Trans fat,” the combination of which comprises the kind of “hodgepodge” described by nutritionists.

These products also carry a range of icons and stamps typical of such Western products, which suggest quality, but also, again a sense of “ticking off” health and ethics. At the bottom of the cereal package, we find three circles. These carry icons: a beehive and droplet of honey, a heart icon, and different grains, rendered as simple, easy to grasp, and represent. The hive naturalizes the sugar content of the product. The grain icon idealizes ‘grains’ as simple. The heart icon symbolizes “health.” What such icons mean is never specified.

We begin to see how these products have been loaded with ideas about healthy and ethical diets, which have been highly criticized by nutritionists in Western societies (Eriksson and Machin Citation2020). There is one aspect of this iconography that deserves specific attention regarding the new forms of representation of nature in China, which we now address.

The romanticization of nature as part of healthy and ethical eating

Visual communication scholars have long observed how marketers in Western markets have used idealized representations of nature to communicate a range of associations to sell food products (Hansen Citation2002; Dragoescu Urlica Citation2021; Stano Citation2021). Mountains can suggest purity and freshness, and cute farmyards connote family-based production (Luetchford Citation2015). Such representations are central to communicating ideas of authenticity, slowness, wholeness, simplicity (Shugart Citation2014). And such representations differ across cultures in relation to real or idealized notions of landscape (Andersson Citation2020). Running through our corpus of packages we find evidence of marketers speaking to, what Chinese scholars have described, as the middle class’ new re-imagining of the natural and nature, shifting from earlier associations with the rural as backward, insular, and low status (Brunner Citation2019).

We see these idealized representations of nature in the whimsical icons of leaves, the ears of wheat, and the sunrise scene on the front of the cereal package (). On the side panel, we find items of fruit and nuts produced in a delicate Chinese water-color style. Here nature is simple, innocent, and tasteful.

The drawing on the back of the pea snack in depicts the stages of the production processes of the product. To the left we see two men, wearing Chinese peasant-style hats, one smiling, labeled as “Meticulously selecting peas.” To the right are two women sitting on the ground, labeled “Ground to a fine pea powder after second careful selection,” where they handle grapefruit-sized peas. This connotes a non-industrial process. It is personalized. There is an emphasis on care, even stressing “after second careful selection.” As Polan (Citation2008) points out, in such representations of romanticized production processes, there is a sense of honesty, skill, and pleasure in basic manual labor, providing contrast to the idea of a cynical, corporatized food industry. Absent are the processes involved in the package design and manufacturing, the stages of product development, branding, marketing, transport, and the disposal of multi-layer wrappers.

The form of the representation of this rural scene is important too. This is a highly idealized scene, not simply in terms of how it is depicted, but in terms of how it communicates innocence and artlessness through the use of the drawings in the fashion of a children’s storybook. The representation here appears to have a more local accent than the kinds of nature documented in Western food marketing such as in the US, UK, and Sweden (Andersson Citation2020). Here the cuteness of the characters and of the scene can be placed in the context of Kawaii culture often found in Chinese marketing (Chen and Machin Citation2014; Iwabuchi Citation2002), aligning with the representations of the happy pea characters seen on the front of the package (). On the package in , we see another idealized rural scene, depicting rice fields, taking a style resembling local scenery, and those found in more modern Chinese landscape art. Here eating healthily and communing with nature fuses with both romantic and idealized ideas of nature and labor and with cosmopolitan associations of Japanese pop culture.

What we see here is that symbolic localness is realized through, ethnic peasants, scenery, and art forms, configured in what Stano (Citation2021) found commonly used to communicate organic food: a wild, rustic, ethnic, and local nature. Such combinations can be recognizable as authentic in localized contexts (Halawa and Parasecoli Citation2021).

Order, rationality, and chic style

It has been argued that ideas and values relating to health (Wagner Citation2015; Ledin and Machin Citation2018) and ethics (Machin and Cobley Citation2020) are coded into such products, not only in words and images but at the level of design in the packages. It is this that helps to give such material objects their discursive power. Work has already been done using these ideas to look at how such choices in food packing can communicate meanings such as “natural” (Wagner Citation2015) “national identities” (Andersson Citation2020), “purity” (O’Hagan Citation2020), “social justice” (Ledin and Machin Citation2020a) and “gender” (Bouvier and Chen Citation2021). We look at textures, fonts, and colors in turn and then consider the nature of the designs they form together.

Textures

The daily nuts (), pea snack (), and Arla milk () packages have slightly uneven, or roughened, textured. In social semiotics (Djonov and Van Leeuwen Citation2011; Aiello and Dickinson Citation2014) it has been argued that such textures can be used to suggest something less polished, less processed, more natural. So, naturalness can be built into a highly processed product at this level. In other packaging, in our sample, for newly appearing, wheat-based bread products, organic pasta, rice, and flour, and low-fat yogurt, we find this kind of attention to texture, also with the use of rougher brown paper bags, wood, and sacking-type cloth.

Forms

Ledin and Machin (Citation2020b) note how manufacturers have developed new forms of packaging such as the pouches we see in . These can be printed with different textures, but also can communicate something both more tidy and modern. We can compare the daily nuts package to a more traditional transparent peanuts plastic package. Machin and Cobley (Citation2020) have noted that in Western societies, such designs have played an important role in shifting associations of natural, organic, and plant-based products away from more ‘Hippie’ associations to align with values of urban modern chic – found used for organic and Fairtrade coffee, nuts, cereals, etc. This same meaning appears relevant for the Chinese middle-class consumers seeking these products with these meanings as part of creating distinctions. Practically such designs are important as part of product differentiation where consumers will be paying significantly higher prices for products already available cheaply in stores nearby.

Fonts

Chen and Machin (Citation2014) documented the adoption of Western patterns in graphic design in China from the early 2000s. One observation was the greater attention given to font qualities to communicate product associations and values, specifically in Chinese characters. We find such use of fonts in this food packaging. On the daily nuts package, we find slim, slightly angular fonts for the ingredients, such as walnuts. On the cereal () and pea snack () packages we see very slender and taller fonts used for the buzzwords, “LOHAS five grain” and the delicate writing used to explain adding fruits, and “baked not fried” and “0 g Trans fat.” It has been argued that slimmer, in contrast to heavier and bolder, fonts can metaphorically suggest something lighter, “delicate,” “subtle,” “healthier” or “low calories,” rather than a heavier font, which might suggest “substantial,” “filling,” “overbearing” (Van Leeuwen Citation2005). Taller fonts can also be associated with values such as “aspirational” and more angular fonts, as technical and rational (Van Leeuwen Citation2005). In these examples, there is a sense of such font qualities being used to bring a sense of tidiness, order, and modernity to the Chinese writing, as well as to communicate, lightness, and simplicity. These can be contrasted to products that carry more traditional forms of Chinese characters where there is less attention to such semiotic meaning potentials.

Color

In MCDA, researchers have looked at the meaning potential of color. This is not only about hue, which is known to have important cultural variations, but also qualities such as levels of saturation, brightness, and purity (Kress and Van Leeuwen Citation2002). It is clear that on the products in our sample we find earthy colors, such as greens and browns and also bright yellows, seen in sunrises, seen on the cereal box, the pea snack, and the landscape in . Such meanings appear to travel well from Western culture. It has been observed that in Chinese culture green aligns with the meanings found in Western cultures, relating to nature and growth (Gage Citation1999). And yellow, while an optimistic color in the West, is associated in China with prosperity.

But it is the color qualities that are particularly important in these designs. Kress and Van Leeuwen (Citation2002) argued that muted colors are associated with more reserved moods, whereas more saturated rich, full, colors relate to more exuberant moods and fun. Such products, in the West, use muted colors to suggest moderate, simple and thoughtful, gentle, attitudes, for example, as compared to children’s products, which tend to carry rich saturated colors. We find this idea of health and ethics coded in our sample through this idea of reserved moods. As in the West, healthy and ethical foods can align with a kind of gentle, well-being. But this is also, as Shugart (Citation2014) notes, part of how they signify distance from the busy and anonymous corporate world. And the use of such muted colors has been observed as a traditional feature of Chinese art related to spirituality and more poetical meanings (Zheng Citation2016).

We also find limited color palettes. Kress and Van Leeuwen (Citation2002) suggest that whereas wide color palettes are associated with energy, liveliness, or garishness, limited palettes suggest restraint, measure, and pensive moods (Kress and Van Leeuwen Citation2002). On the daily nuts and the pea snack package, we find such limited palettes and pastel colors. These products, as on the pea snack, tend to carry a main color, such as green, but then carry small, tasteful touches of other more exciting colors. On the sea snack, we find red for one of the circles at the bottom; on the cherry held by one of the pea characters; a blue musical note, associated with long life in Chinese color symbolism (Gage Citation1999). Again this helps to position such products, with their hodgepodges of buzzwords and expensive packages, as something related to measuring and stillness.

Importantly, across the sample, we find large amounts of white space and empty panels of color. Kress and Van Leeuwen (Citation2002) associate such empty panels, as we see on daily nuts, as about order, cleanliness, rationality, and modernism. We see a striking example in the yogurt package in , which also uses slender fonts and a restricted palette. As Chen and Machin (Citation2014) observe in their comparison of graphic design over the past two decades in China, there is a shift away from elements being crowding and competing to greater use of space and order. As Kress and Van Leeuwen (Citation2002) note, such panels can be connected to the meanings of color in modern art, for example, in the work of Mondrian. This, suggests a modern, ordered form of food, uncontaminated. For these Chinese consumers, there are the associations of health simplicity as well as the cultural capital of modernist or abstract art. We see a striking example in the yogurt package in , which also uses slender fonts and a restricted palette.

Graphic qualities and classifications

While these products may carry a hodgepodge of health and ethical qualities and meanings such as “urban,” “cosmopolitan,” “chic,” at the same time as “natural,” “still,” “simple,” they nevertheless work as coherent carriers of meaning. Ledin and Machin (Citation2018) have been particularly interested in how such designs create coherence and how language and design features can be used to do so. They have explored the use of size, shape, and color of elements in reference to how this can classify them as being of the same or different order. Elements realized in the same size, or forms, of typeface, can be classified as being of a related order. Hue, or other color qualities, can play the same role.

On the top panel of the daily nuts package, the words for the ingredients are represented in the same slim fonts, symbolizing they are of the same order. Their visual realization, through the simplified sketch style, plays a similar role. This is one way by which buzzwords and buzz ingredients become integrated as coherent wholes, as healthy and ethical products.

On the lower panel of this package, we find a different representation of the ingredients. The seven types of dried fruit and nuts are arranged in a tidy line with equal distances between them. Here, they are all classified as the same through sharing saturated colors and heightened tones, what Kress and Van Leeuwen (Citation2006) would call, ‘sensory modality’ or ‘more than real.’

The white of the bottom panel then links with the color of the fonts and sketches in the top panel.

On the one hand, the arrangement of the ingredients and the linking of color between the two panels symbolizes, order, lack of clutter, rationality, as well as design chic. The drive for care, regulation, and order appear salient in communicating natural and healthy to the Chinese consumer. But on the other hand, what is important to take into account in such analysis (Ledin and Machin Citation2020b) is that the manner by which such things are different or alike is not accounted for clearly and transparently in written text. Rather, it is symbolized. Different types of buzzwords and elements can be represented as of the same order, connected, or part of the same domain. Positioning in relation to each other and framing can also symbolize types of relationships between elements (Van Leeuwen Citation2005).

Across our corpus, we find this use of order and integration in designs. On the cereal package, color and style on the side panel link the product, the fruit, milk, and the couple. On the pea snack, the green and white are used in a limited color palette to link the elements together along with a few other colors which rhyme in terms of color quality. On the protein bar () we find again a restricted color palette, the use of space and order, where the color and fonts create integration.

The use of the stamp and icon features seen at the bottom of the cereal package and the back of the protein bar package is also important for symbolization of order and rational management of health and ethics, even where the actual logic of classifications and links is concealed. In these icons, the forms and style of drawings seen in them: the hive, grains, and heart on the cereal box; the knife and fork and images of people engaged in activities on the protein bar, represent these things as being of the same order, as part of being healthy and ethical lifestyle. On the protein bar, eating processed snacks, working, travel, and fitness are unproblematically placed together as an ordered way of managing a person’s life. The links or causality between the elements is not explicit, rather symbolized through the way the form of coding presents them as being of the same order.

Visualizing the new middle classes

Researchers have shown how advertisements display desirable identities, idealized relationships, and life situations (Frith Citation1997; McCracken Citation1989). Advertising in China has introduced newer kinds of identities, specifically those more aligned with consumer individualism and lifestyle (Martin, Lewis, and Sinclair Citation2013). Across our corpus, we find representations of new types of family structures and what it means to be middle class (Fowler, Gao, and Carlson Citation2010; Feng, Poston, and Wang Citation2014).

On the cereal package in we see a couple without children, and not living with parents, having a Western-style breakfast. They have time for each other in an esthetically organized and chic scene. Such representations align with what is seen as more modern ideas of domestic life, shifting away from notions of family ties and responsibility. This involves new kinds of routines, which these products can help to be correctly managed. A healthy diet and the natural are here integrated with these lifestyle shifts.

This modern lifestyle is realized through an art form infused with locality. The scene is represented in the style of Chinese watercolor painting. This typically uses subtle diffused tones with luminosity and transparency, created in part by the kinds of pigments and canvas used. This style is influenced by the techniques of Chinese calligraphy and used to represent more elegant poetical meanings about the human condition and the yin and yang of the universe, drawing on Taoism and Confucianism, found as an influence in modern Chinese art (Zheng Citation2016).

On the Arla milk carton (), we see a family in a park. This is a slightly overexposed photograph suffused with bright light, idealizing the scene with a sense of positivity. Important here is the representation of them outdoors in nature, having fun as a nuclear family. We find no representations of three-generational families in our corpus.

We get more insights into the nature of the new routines and new managed lifestyle through the row of icons found on the back of the protein bar in . We find ‘breakfast’ – symbolized by a knife and fork, not chopsticks, and ‘exercise’ shown as a gym activity. We also find both ‘work’ and ‘business travel.’ The product here is one component of the lifestyle of the modern, successful urban identity. There are no icons for ‘caring for family,’ ‘cleaning the house,’ or ‘community work.’

The Chinese text on the front of the protein bar package, after “hello bar,” reads “you are great” which foregrounds “success” and connects what you eat to a form of self-care, self-management, and fulfillment. This aligns with observations that the Chinese middle classes are increasingly taking on neoliberal forms of identities (Guo Citation2017; Elfick Citation2011). These food products carry a sense of managing all parts of life, where the tick lists of buzz ingredients are provided, allowing the consumer to be goal-driven. This also carries the morality of the self-managing, productive citizen.

Conclusion

The demand for healthy and ethical food is on the rise around the world, especially among the emerging middle class in the Asia Pacific who seek healthier, safer, and more environmental-friendly food options (Montefrio and Wilk Citation2020). Scholars have shown that, in parts, this is influenced by mass and social media (Tarulevicz Citation2020; Montefrio et al. Citation2020). Here, we show this takes place not only through more obvious media forms such as in TVs and advertisements but through the visual more broadly, in the nature of visual design, the forms taken by products, which embed such consumer culture into every life. We also show the value of looking more closely at smaller scale choices in communication carried by product packaging, through which globalized concepts of healthy and ethical food are infused with local accents, while commodified and embedded in the global neoliberal capitalist system.

Bauman (Citation2007) has argued that consumerism increasingly pushes itself into the spaces where we live, but also those that exist between people. So, we come to know the world, each other, and even our own bodies, through the terms and visual worlds presented to us by marketing. As Eriksson and Machin (Citation2020) observe such definitions of things become built into our everyday material worlds through things like food packaging, the setting up of organic farms, the way gyms define activities, the look of a new vegan restaurant or organic coffee shop. And all these can shape what we do and why we do it.

In the paper, we show that, on the surface, these products reflect that the Chinese middle classes are, like many people around the world, concerned with nutrition and environmental issues. The solutions here are presented as easily graspable, though at the same time, only ever symbolized, remaining abstracted. At a deeper level, food, and food marketers, become agents that shape broader identities of modern Chinese middle class – someone that appreciates nature and peasant labor, embraces individuality, practices self-care and conducts themselves as a productive go-getting citizen. These identities are communicated through chic design that weave symbolic localness into the same Western discourses through, a loosely codified set of buzzwords, iconography, and material objects (Halawa and Parasecoli Citation2021).

Scrinis (Citation2013) argues that the ideology of nutritionism has shaped the public to see and engage with food as a set of standardized nutritional concepts and categories, which has undermined other ways of seeing and encountering food. In this paper, we have seen, with the global extension of nutritionism, it is not merely how we see and engage with food that has been simplified and standardized, it is also, through food, who we are, and what we do, is placed within a common frame that creates a single scale of “global” value and structure (Wilk Citation1995, Citation2006) that reflects homogeneous priorities and values and is communicated through similar design approaches that reap commercial benefits.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

David Machin

David Machin is professor of Linguistics at Zhejiang University China. He has published widely in the field of Critical Discourse Studies and Multimodality, and has recently been running a longer term, cross national project on food and communication. His books include How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis (2012), Doing Visual Analysis (2018) and Introduction to Multimodal Analysis (2020). He is co-editor of the journal Social Semiotics. Department of English, School of International Studies, Zhejiang University

Ariel Chen

Ariel Chen is a researcher at Örebro University. She is a member of the research project: Communication of “good” foods and healthy lifestyles. Using Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis, she examines the way the discourse of “good” foods and healthy lifestyles becomes colonized and shaped by commercial interests. Her recent articles can be seen in Critical Discourse Studies; Discourse, Context and Media; and Food, Culture and Society. School of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences, Örebro University [email protected] (Corresponding author)

References

- Aiello, G., and G. Dickinson. 2014. “Beyond Authenticity: A Visual Material Analysis of Locality in the Global Redesign of Starbucks Stores.” Visual Communication 13 (3): 303–321. doi:10.1177/1470357214530054.

- Aiello, G., and L. Pauwels. 2014. “Special Issue: Difference and Globalization.” Visual Communication 13 (3): 275–285. doi:10.1177/1470357214533448.

- Andersson, H. 2020. “Nature, Nationalism and Neoliberalism on Food Packaging: The Case of Sweden.” Discourse, Context & Media 34: 100329. doi:10.1016/j.dcm.2019.100329.

- Banet-Weiser, S. 2012. Authentic TMs: Politics and Ambivalence in a Brand Culture. New York: New York University Press.

- Bauman, Z. 2007. “Collateral Casualties of Consumerism.” Journal of Consumer Culture 1: 25–56. doi:10.1177/1469540507073507.

- Bouvier, G., and A. Chen. 2021. “The Gendering of Healthy Diets: A Multimodal Discourse Study of Food Packages Marketed at Men and Women.” Gender & Language 15 (3).

- Brunner, E. 2019. “Chinese Urban Elites Return to Nature: Translating and Commodifying Rural Voices, Places, and Practices.” China Media Research 15 (2): 29–38.

- Charmaz, K. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage.

- Chen, A., and G. Eriksson. 2019. “The Mythologization of Protein: A Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis of Snacks Packaging.” Food, Culture and Society 22 (4): 423–445. doi:10.1080/15528014.2019.1620586.

- Chen, A., and D. Machin. 2014. “The Local and the Global in the Visual Design of A Chinese Women’s Lifestyle Magazine: A Multimodal Critical Discourse Approach.” Visual Communication 13 (3): 287–301. doi:10.1177/1470357214530059.

- Chen, J., and A. Lobo. 2012. “Organic Food Products in China: Determinants of Consumers’ Purchase Intentions.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 22 (3): 293–314. doi:10.1080/09593969.2012.682596.

- Chera, M. 2020. “Country Chicken and Multiple Knowledges: Foucauldian Resistance in Young Tamil Women’s Cultural Critique of Globalized Food.” Food, Culture & Society 23 (2): 209–228. doi:10.1080/15528014.2019.1682900.

- De Ridder, D., F. Kroese, C. Evers, M. Adriaanse, and M. Gillebaart. 2017. “Healthy Diet: Health Impact, Prevalence, Correlates, and Interventions.” Psychology and Health 32 (8): 907–941. doi:10.1080/08870446.2017.1316849.

- De St. Maurice, G. 2013. “The Movement to Reinvigorate Local Food Culture in Kyoto, Japan.” In Food Activism: Agency,Democracy and Economy, edited by C. Counihan and V. Siniscalchi, 77–94. London: Berg.

- Djonov, E., and T. Van Leeuwen. 2011. “The Semiotics of Texture: From Haptic to Visual.” Visual Communication 10 (4): 541–564. doi:10.1177/1470357211415786.

- Dragoescu Urlica, A. 2021. “Restoring the Meaning of Food: Biosemiotic Remedies for the Nature/Culture Divide.” In Food and Medicine: A Biosemiotic Perspective, edited by Y. H. Hendlin and J. Hope. Springer, 97–114.

- Dreher, A., N. Gaston, and P. Martens. 2008. Measuring Globalization: Gauging Its Consequences. New York: Springer.

- Elfick, J. 2011. “Class Formation and Consumption among Middle-Class Professionals in Shenzhen.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 40 (1): 187–211. doi:10.1177/186810261104000107.

- Eriksson, G., and D. Machin. 2020. “Discourse of ‘Good Food’: The Commercialization of Healthy and Ethical Eating.” Discourse, Context and Media 33: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.dcm.2019.100365.

- Fairclough, N. 1992. Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Feng, X., D. Poston, and X. Wang. 2014. “China’s One-Child Policy and the Changing Family.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 45 (1): 17–29. doi:10.3138/jcfs.45.1.17.

- Ferguson, P. 2010. “Culinary Nationalism.” Gastronomica 10 (1): 102–109. doi:10.1525/gfc.2010.10.1.102.

- Fernan, C., J. Schuldt, and J. Niederdeppe. 2017. “Health Halo Effects from Product Titles and Nutrient Content Claims in the Context of ‘Protein’ Bars.” Health Communication 33 (12): 1425–1433. doi:10.1080/10410236.2017.1358240.

- Flowerdew, J., and J. Richardson. 2017. The Routledge Handbook of Critical Discourse Studies. Oxon: Routledge.

- Forsyth, T., and Z. Young. 2007. “Climate Change CO2lonialism.” Mute 2 (5): 28–35.

- Foucault, M. 1972. Archaeology of Knowledge. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Fowler, A., J. Gao, and L. Carlson. 2010. “Public Policy and the Changing Chinese Family in Contemporary China: The past and Present as Prologue for the Future.” Journal of Macromarketing 30 (4): 342–353. doi:10.1177/0276146710377095.

- Frith, K. 1997. “Undressing the Ad: Reading Culture in Advertising.” In Undressing the Ad: Reading Culture in Advertising, edited by K. Frith, 1–17. New York: Peter Lang.

- Gage, J. 1999. Color and Culture: Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Goodman, D. 2013. “Middle Class China: Dreams and Aspirations.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 19: 49–67. doi:10.1007/s11366-013-9275-x.

- Grunert, K., T. Peres, Y. Zhou, G. Huang, B. Sorensen, and K. Athanasios. 2011. “Is Food-Related Lifestyle Able to Reveal Food Consumption Patterns in Non-Western Cultural Environments? Its Adaption and Application in Urban China.” Appetite 56: 357–367. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2010.12.020.

- Guo, S. 2017. “Acting through the Camera Lens: The Global Imaginary and Middle Class Aspiration in Chinese Urban Cinema.” Journal of Contemporary China 26 (104): 311–324. doi:10.1080/10670564.2016.1223099.

- Halawa, M., and F. Parasecoli. 2021. “Global Brooklyn: How Instagram and Postindustrial Design are Shaping How We Eat.” In Global Brooklyn: Designing Food Experience in World Cities, edited by F. Parasecoli and M. Halawa, 3–36. London/New York: Bloomsbury.

- Halliday, M. 1978. Language as Social Semiotic: The Social Interpretation of Language. London: Edward Arnold.

- Hansen, A. 2002. “Discourses of Nature in Advertising.” Communications 27 (4): 499–511. doi:10.1515/comm.2002.005.

- Ho, H. 2020. “Cosmopolitan Locavorism: Global Local-Food Movements in Postcolonial Hong Kong.” Food, Culture & Society 23 (2): 137–154. doi:10.1080/15528014.2019.1682886.

- Hsu, J. 2008. “Glocalization and English Mixing in Advertising in TaiwanIts Discourse Domains, Linguistic Patterns, Cultural Constraints, Localized Creativity, and Sociopsychological Effects.” Journal of Creative Communications 3 (2): 155–183. doi:10.1177/097325860800300203.

- IFOAM. 2009. One Earth, Many Minds – 2009 Annual Report. Hamburg, Germany: International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements.

- Iles, I., X. Nan, and L. Verrill. 2017. “Nutrient Content Claims: How They Impact Perceived Healthfulness of Fortified Snack Foods and the Moderating Effects of Nutrition Facts Labels.” Health Communication 18: 1–9.

- Iwabuchi, K. 2002. Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Johnston, J., and S. Baumann. 2010. Foodies: Democracy and Distinction in the Gourmet Foodscape. New York: Routledge.

- Khalikova, V. R. 2020. “A Local Genie in an Imported Bottle: Ayurvedic Commodities and Healthy Eating in North India.” Food, Culture & Society 23 (2): 173–192. doi:10.1080/15528014.2020.1713429.

- Kress, G. 2010. Multimodality: A Social Semitic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London: Routledge.

- Kress, G., and T. Van Leeuwen. 2002. “Color as a Semiotic Mode: Notes from a Grammar of Color.” Visual Communication 1 (3): 343–368. doi:10.1177/147035720200100306.

- Kress, G., and T. Van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

- Lechner, F., and J. Boli. 2005. World Culture: Origins and Consequences. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Ledin, P., and D. Machin. 2018. Doing Visual Analysis. London: Sage.

- Ledin, P., and D. Machin. 2020a. “Replacing Actual Political Activism with Ethical Shopping: The Case of Oatly.” Discourse, Context & Media 34: 100344. doi:10.1016/j.dcm.2019.100344.

- Ledin, P., and D. Machin. 2020b. Introduction to Multimodal Analysis. London: Bloomsbury.

- Lewis, T. 2008. Smart Living: Lifestyle Media and Popular Expertise. New York: Peter Lang.

- Lin, Y. 2020. “Sustainable Food, Ethical Consumption and Responsible Innovation: Insights from the Slow Food and “Low Carbon Food” Movements in Taiwan.” Food, Culture & Society 23 (2): 155–172. doi:10.1080/15528014.2019.1682885.

- Low, W., E. Davenport, and M. Carrigan. 2005. “Has the Medium (Roast) Become the Message?: The Ethics of Marketing Fair Trade in the Mainstream.” International Marketing Review 22 (5): 494–511. doi:10.1108/02651330510624354.

- Lu, X. 1998. “An Interface between Individualistic and Collectivistic Orientations in Chinese Cultural Values and Social Relations.” Howard Journal of Communications 9 (2): 91–107. doi:10.1080/106461798247032.

- Luetchford, P. 2015. ““The Hands that Pick Fair Trade Coffee: Beyond the Charms of the Family Farm.” In Hidden Hands in the Market: Ethonogrphies of Fair Trade, Ethical Consumption and Corporate Social Responsibility, edited by D. N. Geert, P. Luetchford, J. Pratt, and D. Wood, 143–169. Bingley: Emerald.

- Machin, D., and P. Cobley. 2020. “Ethical Food Packaging and Designed Encounters with Distant and Exotic Others.” Semiotica 232: 251–271. doi:10.1515/sem-2019-0035.

- Machin, D., and A. Mayr. 2012. How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis. London: Sage.

- Mao, P. 2018. “The Cultural Imaginary of Middle Society in Early Republican Shanghai.” Modern China 44 (6): 620–651. doi:10.1177/0097700418766827.

- Martin, F., T. Lewis, and J. Sinclair. 2013. “Lifestyle Media and Social Transformation in Asia.” Media International Australia 147 (1): 51–56. doi:10.1177/1329878X1314700107.

- McCracken, G. 1989. “Who Is the Celebrity Endorser? Cultural Foundations of the Endorsement Process.” Journal of Consumer Research 16 (3): 310–321. doi:10.1086/209217.

- Monastyrsky, K. 2005. Fiber Menace. USA: Ageless Press.

- Montefrio, M. J., J. C. De Chavez, A. P. Contreras, and D. S. Erasga. 2020. “Hybridities and Awkward Constructions in Philippine Locavorism: Reframing Global-Local Dynamics through Assemblage Thinking.” Food, Culture & Society 23 (2): 117–136. doi:10.1080/15528014.2020.1713428.

- Montefrio, M. J., and R. Wilk. 2020. “Transecting ‘Healthy’ and ‘Sustainable’ Food in the Asia Pacific.” Food, Culture & Society 23 (2): 102–116. doi:10.1080/15528014.2020.1713431.

- O’Hagan, A. 2020. “Pure in Body, Pure in Mind? A Sociohistorical Perspective on the Marketisation of Pure Foods in Great Britain.” Discourse, Context & Media 34: 100325. doi:10.1016/j.dcm.2019.100325.

- O’Neill, K., and D. Silver. 2017. “From Hungry to Healthy.” Food, Culture and Society 20 (1): 101–132. doi:10.1080/15528014.2016.1243765.

- Olayanju, J. 2019. “Top Trends Driving Change in the Food Industry [Online]”. Forbes. accessed 19 June 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/juliabolayanju/2019/02/16/top-trends-driving-change-in-the-food-industry/

- Patterson, M., and J. Johnston. 2012. “Theorizing the Obesity Epidemic: Health Crisis, Moral Panic and Emerging Hybrids.” Social Theory and Health 10 (3): 265–291. doi:10.1057/sth.2012.4.

- Phillips, L. 2006. “Food and Globalization.” Annual Review of Anthropology 35: 37–57. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123214.

- Pilcher, J. 2017. Food in World History. London: Routledge.

- Pink, S. 2013. Doing Visual Ethnography. London: Sage.

- Polan, M. 2008. In Defence of Food: The Myth of Nutrition and the Pleasures of Eating. New York: Penguin.

- Pristed Nelson, H., and S. T. Faber. 2014. “A Strange Familiarity? Place Perceptions among the Globally Mobile.” Visual Communication 13 (3): 373–388. doi:10.1177/1470357214530053.

- Riccioli, F., R. Moruzzo, Z. Zhang, J. Zhao, Y. Tang, L. Tanacci, F. Boncinelli, et al. 2020. “Willingness to Pay in Main Cities of Zhejiang Province (China) for Quality and Safety in Food Market”. Food Control 108: 106831. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.106831.

- Scrinis, G. 2013. Nutritionism: The Science and Politics of Dietary Advice. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Shugart, H. A. 2014. “Food Fixations.” Food Culture and Society 17 (2): 261–281. doi:10.2752/175174414X13871910531665.

- Siipi, H. 2012. “Is Natural Food Healthy?” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 26: 797–812. doi:10.1007/s10806-012-9406-y.

- Stano, S. 2021. “Food, Health and the Body: A Biosemiotic Approach to Contemporary Eating Habits.” In Food and Medicine: A Biosemiotic Perspective, edited by Y. H. Hendlin and J. Hope, 43–60. Springer.

- Su, B. 2010. “Rural Tourism in China.” Tourism Management 32: 1438–1441. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2010.12.005.

- Tarulevicz, N. 2020. “Discursively Globalized: Singapore and Food Safety.” Food, Culture & Society 23 (2): 193–208. doi:10.1080/15528014.2019.1682890.

- Tomba, L. 2014. The Government Next Door: Neighborhood Politics in Urban China. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Tong, Q., S. Anders, J. Zhang, and L. Zhang. 2020. “The Role of Pollution Concerns and Environmental Knowledge in Making Green Food Choices: Evidence from Chines Consumers.” Food Research International 130: 108881. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108881.

- Van Dijk, T. 2009. “Critical Discourse Studies: A Sociocognitive Approach.” Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis 2 (1): 62–86.

- Van Leeuwen, T. 2005. Introducing Social Semiotics. London: Routledge.

- Veeck, A., and G. Veeck. 2000. “Consumer Segmentation and Changing Food Purchase Patterns in Nanjing, PRC.” World Development 28 (3): 457–471. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00135-7.

- Wagner, K. 2015. “Reading Packages: Social Semiotics on the Shelf.” Visual Communication 14 (2): 193–220. doi:10.1177/1470357214564281.

- Wilk, R. 1995. “Learning to Be Local in Belize: Global Systems of Common Difference.” In Worlds Apart: Modernity through the Prism of the Local, edited by D. Miller, 110–133. New York: Routledge.

- Wilk, R. 2006. Home Cooking in the Global Village: Caribbean Food from Buccaneers to Ecotourists. New York, NY: Berg.

- Xu, J. 2007. “Brand-New Lifestyle: Consumer-Oriented Programs on Chinese Television.” Media Culture and Society 29 (3): 363–376. doi:10.1177/0163443707076180.

- Yan, Y. 2009. The Individualization of Chinese Society. Oxford: Berg.

- Zhang, W. 2020. “Consumption, Taste, and the Economic Tradition in Modern China.” Consumption Markets & Culture 23 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1080/10253866.2018.1467316.

- Zheng, J. 2016. The Modernization of Chinese Art: The Shanghai Art College, 1913–1937. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

- Zhou, Z. 2008. “The Development of Organic Sector in China.” Paper read at Workshop of guaranteeing integrity of organic products from China, February 21, in Nuremberg, Germany

- Zou, T. 2005. “The Rural Tourism Model: The Comparison and Countermeasures Analysis on Chengdu’s Happy in Farmer’s Family and Beijing’s Folk-Custom Tourism.” Chinese Tourism Research Annual 2006: 142–146.