ABSTRACT

Default options have been successfully utilized in influencing behavior across multiple domains. Recent empirical evidence advocated the induction of transparency to default interventions as an effective tool for increasing policy compliance. However, the roles of the different transparency components in achieving the effect remain unexplored. In an experimental study, we measured the effects of three different transparency disclosures on default effectiveness. The default’s target behavior, the default’s purpose, and the way defaults work were disclosed in separate conditions. Our results show that transparency significantly increases compliance to the default nudge. In addition, we provide an insight as to which transparency components are most effective in boosting the default effect.

Influencing others has long been a central theme in social psychology (for reviews see Cialdini & Goldstein, Citation2004; Pratkanis, 2007; Van Der Pligt & Vliek, Citation2016). Over time, many influence and persuasion theories have been proposed (Crano & Prislin, Citation2008; Eagly & Chaiken, Citation1993; Vogel & Wänke, Citation2016) and numerous influence techniques have been researched and applied (Cialdini, Citation2016; Goldstein, Martin, & Cialdini, Citation2008). Recent years saw a new interest in the topic as well as a perspective shift when Thaler and Sunstein (Citation2008) propagated ‘nudging’ people by engineering the choice environment in a manner that presumably facilitates pro-social and self-beneficial behavior. While a precise operational definition of nudging is still lacking (Marteau, Ogilvie, Roland, Suhrcke, & Kelly, Citation2011), nudgers, also known as choice architects, have successfully implemented nudge-based interventions in institutional and private policies across multiple domains.

One of the most effective means of nudging is the use of default options. Typically, the decision makers are presented with an array of choice options, one of which is pre-selected. However, they retain the possibility to actively choose another alternative, i.e., to opt-out from the default. Generally, people tend to stick to the preselected option, thus making defaults an effective strategy for influencing the choice. Default-based interventions have been successful in promoting pro-social behavior in a wide range of settings, including organ donation decisions (Johnson & Goldstein, Citation2003), retirement savings (Thaler & Benartzi, Citation2004), and energy conservation (Allcott & Mullainathan, Citation2010). At first glance, defaults seem to capitalize on people’s inertia, which makes them stick to the pre-selected option, but as elaborated later, defaults also involve a social component (McKenzie, Liersch, & Finkelstein, Citation2006).

The implementation of defaults, however, has also raised concerns about the degree to which default-based interventions restrict peoples’ freedom of choice. As the target of a default intervention is unaware of the influence attempt and the way it brings about the desired behavioral change (Hansen & Jespersen, Citation2013), some researchers have argued that defaults limit people’s autonomy and their ability to exercise informed choice (Smith, Goldstein, & Johnson, Citation2013). In line with this notion, Jung and Mellers (Citation2016) demonstrated that defaults were viewed less favorably and were perceived as more autonomy threatening than other nudges. Thus, an ethical perspective calls for transparency in default interventions.

Yet, researchers have also expressed concerns that transparency might harm the effectiveness of default nudges. Meta-analytic evidence by Wood and Quinn (Citation2003) indicates that being forewarned about an upcoming attitude influence appeal makes people bolster their attitudes as a form of a defensive response. Consequently, such defensive position may prompt retaliation against a given choice architecture, provided that the invigorated attitudes go against it. Therefore, Krijnen, Tannenbaum, and Fox (Citation2017) speculated that once an influence attempt is disclosed, people can actively choose to oppose the promoted course of action. Bovens (Citation2009) also speculated that once people became aware that there is an attempt to influence their choice, they can counteract it by engaging in behaviors that are inconsistent with the purpose of the intervention and/or their initial decision. Hence, he argued that nontransparent nudges, such as defaults, work ‘better in the dark’ and should become largely ineffective as transparency is introduced. Although Bovens did not test his assumptions, reactance theory (Brehm, Citation1966) and people’s strife for self-determination (Deci, Citation1975; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000) would make similar, even stronger predictions, linking resistance to the mere presence of an influence attempt.

On the other hand, social psychological perspectives challenge the considerations regarding ethicality and transparency. In most social interactions, a communicator’s choice of message type conveys information about her/his attitudes toward a given choice option to the other party (Sher & McKenzie, Citation2006). If one is to construe the default setting as a form of a social interaction between the default setter and the targeted population, then one can assume that setting the default in itself can communicate information about the default setters’ preferences and intentions. In fact, McKenzie et al. (Citation2006) demonstrated that when defaulted, the targeted individuals were able to recognize that a particular choice option is made easier to adopt, and that the default-setters wanted them to choose that option. Therefore, the authors concluded that the default setting per se was perceived as a form of an implicit recommendation, which was sufficient to trigger a desirable response. Moreover, insights from persuasion research (Persuasion Knowledge Model; Friestad & Wright, Citation1994; Kirmani & Campbell, Citation2009) show that people are not only capable of recognizing the influence agent’s intent, but can also construe beliefs about her or his strategies and tactics, synthesizing those in a form of unique persuasion knowledge. In this sense, it is not entirely prudent to think of defaults as completely nontransparent and unethical. Even when no additional information is conveyed, people seem to recognize the default as an influence attempt and extrapolate the default’s setter’s attitudes and intentions, thus (at least partially) retaining their ability to make an informed choice.

Adopting such a perspective, one would predict that a disclosure of the default strategy may not harm the effectiveness of a default as Bovens (Citation2009) predicted, but might even boost its impact. Since people are capable of recognizing defaults as implicit influence attempts, a transparent communicator – one who proactively discloses the default setting – can transform the implicit recommendation into an explicit one, and can thus give the default a further boost: Explicit recommendations are known to have a strong effect on informing people’s behavior (e.g., Ansari, Essegaier, & Kohli, Citation2000; Kinney, Richards, Vernon, & Vogel, Citation1998; O’Keefe, Citation1997). Moreover, an explication may not only foster the addressee`s confidence in which behavior is desired, but could also trigger positive inferences about the communicator. Specifically, transparent disclosures can foster the perception that the communicator is fair (Steffel, Williams, & Pogacar, Citation2016) and sincere (Paunov, Wänke, & Vogel, Citation2018), which is an integral part of the communicator’s credibility (Eisend, Citation2006). A plethora of findings from communication and persuasion research show that source credibility has a strong persuasive impact (e.g., Hovland & Weiss, Citation1951; Hovland, Janis, & Kelley, Citation1953; for a meta-analysis see Wilson & Sherrell, Citation1993). Therefore, one might even expect an increased rather than reduced compliance when the default setter is transparent about the influence attempt.

The empirical evidence on transparency is mixed, but so far the respective research has found no evidence of a negative impact on default effectiveness (Bruns, Kantorowicz-Reznichenko, Klement, Jonsson, & Rahali, Citation2018; Loewenstein, Bryce, Hagmann, & Rajpal, Citation2015; Steffel et al., Citation2016). Instead, a recent experiment by Paunov et al. (Citation2018) demonstrated that transparency can actually increase the effectiveness of several default nudges. Building on the theoretical insights of McKenzie et al. (Citation2006) and Hansen and Jespersen (Citation2013), Paunov and colleagues took an eclectic approach to conceptualizing transparency. They defined it as an objective intervention characteristic, whereby the endorser fully discloses the default’s presence, its purpose, and its general effect. The authors’ main reasoning was that by proactively installing transparency, the policy makers would communicate that they do not intend to trick people into the desired behavior, but to help them make an informed choice instead. Across three experimental studies, the endorser´s proactive disclosure of the default’s presence, purpose, and general effect significantly increased compliance in comparison to free choice and a traditional default condition. However, while this transparency induction proved successful in eliciting the desired choice, the individual role of each transparency component remains unclear. Does one really need to disclose all three components, or is a single one sufficient to increase compliance? Is one component more effective than another in bringing the desired behavioral change? The present research provides a more systematic test of different transparency disclosures, namely the what, the why and the how. More specifically, we vary whether people are explicitly informed (a) what the default is intended to achieve (disclosure of target behavior), (b) why the endorser wants people to choose the defaulted option (disclosure of purpose), and (c) how defaults affect behavior in general (disclosure of general effect).

In principle, each category has the potential to deliver a positive effect on its own. First, one can assume that clarifying the default target behavior may trigger an increase in compliance simply because it makes the respective behavior more obvious and salient. Generally, people react positively to the presence of exact behavioral information and express more support for nudges, which provide it (Felsen, Castelo, & Reiner, Citation2013).

Second, disclosing the reason why the default should be chosen can provide people with a valid justification for complying. Compliance and willingness to cooperate increase significantly when a request (Bohm & Hendricks, Citation1997; Langer, Blank, & Chanowitz, Citation1978) or an influence attempt (Becker, Citation1978) is accompanied by higher levels of justification. In addition, disclosing the reason behind the default can be especially beneficial, if it represents a strong argument in favor of complying: A number of findings from persuasion research reveal a positive link between the strength of the arguments, which constitute a given influence attempt, and its persuasiveness (Chaiken & Trope, Citation1999; Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1979). Therefore, disclosing the default’s purpose can not only help people justify complying, but can also contribute to the persuasiveness of the disclosure, provided that it presents a strong argument in favor of the pre-selection.

Lastly, a proactive disclosure of the default’s influence on people’s decision-making may also have a positive effect on compliance via creating the perception that the endorser approaches the targeted population in a sincere way (Paunov et al., Citation2018; Steffel et al., Citation2016). Put together, either transparency component may be the sole cause of an increase in compliance.

However, there is also the possibility that in isolation, certain transparency components may fail to produce a positive effect or could even be detrimental to the default’s effectiveness. Prominent psychological theorizing asserts that people strive for self-determination (Deci, Citation1975; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000) and resent limitations to their freedom of choice (Brehm, Citation1966). Presumably, an explicit disclosure of the default’s general effect is most likely to trigger opposition. Informing people that they generally tend to stay with a defaulted option, once such is set, can render it especially salient that their choice is not entirely autonomous.

In sum, despite the recent evidence that an eclectic disclosure of all transparency components can increase the effectiveness of a default nudge (Paunov et al., Citation2018), little is known about the robustness of the effect and the exact impact of the separate transparency components. The present research aims to fill these gaps. First, we intend to replicate the positive effect of transparency on default compliance, introducing a more challenging social dilemma setting, where choosing the default option goes against the strict self-interest of the participants. Second, we aim to disentangle the effects of the different transparency constituents via setting up separate experimental conditions for the respective disclosures.

The present research

An online experiment was conducted, which explored the effects of transparency on default nudge compliance in the context of devoting time (personal cost) to promote participation in scientific research. Compliance rates across five experimental conditions were compared between participants. A free-choice condition obtained a baseline. In a second condition, a conventional default was set. Three further conditions each realized one type of disclosure as described previously: a target behavior disclosure condition (‘what’), a disclosure of purpose condition (‘why’), and a general effect disclosure condition (‘how’). The effectiveness of the default intervention was isolated by comparing the free-choice condition against the four default conditions, where we predicted a positive effect of defaulting on willingness to participate in scientific research. The main effect of transparency was derived from contrasting the conventional default condition against the three transparent default conditions. In congruence with Paunov et al. (Citation2018), we predicted a positive effect of transparency on default effectiveness.

As discussed previously, each type of disclosure has the potential to bring about the desired behavioral change either in isolation, or in a combination with other disclosures. Based on our theoretical reasoning, we assume that disclosing the defaults purpose or providing information about the expected participant behavior will increase compliance with the default. Given the argument that disclosing the default’s general effect can trigger resistance (Bovens, Citation2009; Brehm, Citation1966), we expect that such disclosure is less likely to produce a positive effect, and can even hinder the default’s effectiveness.Lastly, in an explorative manner, we assessed the participants’ scores on two variables: disclosure argument strength and perceived endorser deceptiveness. As theorized previously, differences between the strength of the arguments in the respective disclosures can provide an indication as to how justifiable compliance is, or how persuasive the disclosures are. Perceived endorser deceptiveness, on the other hand, has been previously associated with compliance in Paunov et al. (Citation2018) experiments, and may help explain the main transparency effect on compliance.

Method

Participants and design

The required sample size for a planned power of 80% (1-ß = 0.8, two-tailed, α = .05), was calculated with G*Power (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, and Lang, Citation2009) using odds ratios (ORs). The expected effect size was extrapolated based on the results of Paunov et al. (Citation2018). An odds ratio of 2.132 and a probability of opting out under transparency Pr(Y = 1 |X = 1) H0 = .46 rendered a required sample of 228 participants. Conservatively, 311 English-speaking participants were recruited via an online respondent panel (198 females (64, 3%), 109 males (35,4%), 1 unspecified (0,3%), mean age 33.5 years (SD =11,3)), and were randomly assigned to the five experimental conditions. Each participant was paid £ 0.45 for participating in the study.

Materials and procedure

Respondents who decided to take part in our research were informed that there were several studies they could choose from, and that the studies differed in content and duration. Only the duration was provided for each study without any content description. The following five choice options were listed: ‘<3 min’, ‘3 to 5 min’; ‘5 to 7 min’; ‘7 to 9 min’; and ‘more than 9 min’. Across all five conditions and simultaneously with the presentation of the choice options, the participants had been informed that they would be paid for doing a 5-min study, independent of the duration of the study they chose. Therefore, choosing the first option provided the opportunity to spend less than 5 min (thus maximizing the participant’s profit), while the second allowed for spending a maximum of 5 min in order to break even without violating the contract. Because we wanted to default an option that was not attractive a priori, in all four default conditions, the ‘5 to 7 min’ study duration category was pre-selected. A choice of this option meant that the participants accepted higher personal costs than necessary, for the sake of supporting scientific research. In the three transparent default conditions, the pre-selection was accompanied by a disclosure, which clarified either the expected participant behavior (target behavior disclosure), the purpose of the default (default purpose disclosure), or the way in which defaults affect behavior (general effect disclosure). In the nontransparent default condition, the ‘5 to 7 min’ option was pre-selected, unaccompanied by transparency information. In the free choice condition, none of the choice options was pre-selected. The respective conditions and disclosures are presented in . The exact wording of our general instruction is provided in part 1 of the Supplementary Online Material (SOM).

Table 1. Overview of the experimental conditions and disclosures.

After indicating their choice, the participants filled in an exploratory post-questionnaire, which measured scores on two constructs: disclosure argument strength and perceived endorser deceptiveness. Disclosure argument strength was assessed across the transparent default conditions to test which disclosure(s) represented a stronger argument in favor of the pre-selection. The perceived endorser deceptiveness measure was administered across all conditions to probe for a possible explanation of the positive transparency effect. After that, the participants responded to several multiple-choice questions, designed to capture the extent to which they had read and understood the stimulus information. Upon providing some demographic information, the participants were redirected to an unrelated task, which took approximately 3 min to complete. Finally, all respondents were thoroughly debriefed about the purpose of the experiment, re-affirmed their agreement to submit data, and received a code to redeem their endowment.

Measures

The main dependent variable was choice of the target option, coded 0 for not choosing it/opting out, and 1 for choosing it/staying with the default. After making their choice, the participants were presented with the exploratory post-choice questionnaire, where six items (α = .89) captured the degree to which the participants felt deceived by the endorser (e.g., ‘When I consider how the choice of categories was presented to me, I think that the experimenters tried to manipulate me.’). In the transparency conditions, seven additional items (α = .91) measured how strong the arguments for setting up the default in the respective disclosures were (e.g., ‘The argument, which the experimenters made for pre-selecting a category for me, was compelling.’). Agreement with all statements was indicated on a seven-point rating scale (1 = ‘not at all’; 7 = ‘most definitely’). For all items, see part 2 of the SOM.

Lastly, we presented the participants with several multiple-choice questions designed to capture the extent, to which they had paid attention to the stimulus information. A full list of the respective questions per condition is available in part 3 of the SOM. In accordance with the procedure employed by Paunov et al. (Citation2018), only participants who had answered all control questions correctly were included in the analysis.

Results and discussion

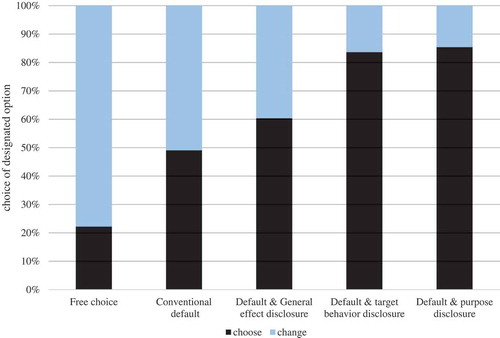

Forty-six participants were excluded for providing wrong answers to one or more items of the stimulus attention check, leaving a sample of N = 265 valid cases. Running all following analyses with all participants included yields the same conclusions. The main descriptive results are reported in . Across the transparent conditions, an average of 76.3% of the participants chose to stay with the default (vs. 23.7% who opted out), while in the conventional default condition, only 49.1% chose this option, but 50.9% opted out. For comparison, the crucial option was selected by only 22.2% of the respondents in the free-choice condition.

Table 2. Proportion of participants choosing the target option per condition.

For a test of significance, choices (coded 1 = stay/choose target option; 0 = opt out/choose other option) were predicted from two Helmert contrasts in a binomial logistic regression. The contrasts indicated whether there was a default or not (free choice = – 0.50, transparent default conditions and conventional default condition = 0.125), and whether the default was transparent or not (transparent defaults = 0.167, free choice = 0, conventional default = – 0.50). A summary of the regression is available in .

Table 3. Summary of logistic regression analysis for the effects of default and transparency on choice of target option.

The first contrast was significant, b = 3.39 (SE = 0.58), Wald-χ2(1) = 34.12, p < .001, showing that the default systematically increased choices of the target option over a free-choice format. Pertinent to our research question, transparency significantly increased the proportion of participants choosing the defaulted option as compared to the conventional default condition: b = 1.81 (SE = 0.49), Wald-χ2(1) = 13.41, p < .001. Therefore, even in cases when the desired behavior comes with the possibility of a personal loss, making a default explicitly transparent increased its effectiveness. Notably, the respective choice option was not favored a priori, as evident from the free choice condition. The default setting doubled the choices for that option, and making the default explicitly transparent more than tripled itFootnote1.

Next, in an exploratory manner, we compared the effect of each transparency component against the conventional default condition. When faced with a mere default, 49.1% of the participants stayed with the pre-selected option. As illustrated in , compliance rates were higher in the general effect disclosure condition (60,4%, Х2(1, N= 108) = 1.39, p = .239), the target behavior disclosure condition (83.6%, Х2(1, N= 110) = 14.70, p < .001), and the default purpose disclosure condition (85.4%, Х2(1, N= 103) = 15.07, p < .001), but only the latter two conditions were significantly different from the conventional default group. Therefore, disclosing the way in which defaults affect behavior in general was not detrimental to default effectiveness as could be assumed based on self-determination and reactance theories. Yet, it had no significant positive effect either. In congruence with our predictions, disclosing the purpose of the default or the expected target behavior was sufficient to bring about a positive effect on default effectiveness.

Next, we assessed whether compliance behavior was related to participants’ perceptions of endorser deceptiveness. While higher perceived deceptiveness was negatively correlated with choosing the default option (r = −.144, n = 265, p = .019), the deceptiveness scores did not differ significantly between conditions (F(4, 260) = .917, p= .455), suggesting that perceived deceptiveness was not responsible for the transparency effect.

Moreover, across the transparency conditions, we assessed the strength of the argument for setting up the default. Perceived argument strength was positively correlated with compliance (r = .208, n = 180, p = .005) so that stronger arguments were associated with higher compliance rates. Participant scores were highest in the default purpose condition (M = 5.14, SD = 1.18), followed by the general effect (M = 4.69, SD = .94) and goal behavior (M = 4.07, SD = 1.5) disclosure conditions (F(2, 153) = 10.582, p =.001). In sum, people’s compliance to a transparent default nudge was positively related to the strength of the arguments provided for setting up the intervention, and disclosing the defaults’ purpose was considered the strongest argument.

General discussion

The results confirmed that introducing transparency to a conventional default nudge can increase its effectiveness. Replicating the findings of Paunov et al. (Citation2018) not only substantiates a previously isolated finding in the literature, but also supports a proactive approach to transparency in nudging, re-affirming that (within limitations) a transparent nudge can be more effective than a conventional one. After all, transparency is one of the guiding principles of the nudging paradigm (Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2008), enabling people to scrutinize the implemented forms of choice architecture (Sunstein, Citation2015).

In addition, we demonstrated that the role of transparency in defaults is more complex than expected from previous (null) findings (Loewenstein et al., Citation2015; Steffel et al., Citation2016). Going beyond the data available so far, we demonstrated which transparency disclosures can bring about the effect. In line with our predictions, disclosing the purpose of the default had a positive effect on compliance. This finding is in line with previous research on request justification (Langer et al., Citation1978), and provides a possible link to the persuasiveness of the disclosure, which was judged to contain the strongest argument in favor of the pre-selection.

We also showed that disclosing which target behavior is desired increased compliance in comparison to a classic default nudge. While previous research links the provision of exact behavioral information to increased theoretical support for similar nudges (Felsen et al., Citation2013), as to our knowledge, our findings are the first to relate the disclosure of target behavior to an increase in actual compliance with defaults.

Further, informing the participants of the defaults’ general effect was neither detrimental nor beneficial for compliance. Possibly, two effects canceled each other out, resulting in a null-effect: while, on the one hand, participants in this condition perceived the endorser as relatively fair, they rated the argument strength of the disclosure as lowest from all conditions. A similar combination of positive and negative effects of transparency may help explaining why previous research on transparent defaults (Bruns et al., Citation2018; Steffel et al., Citation2016) did not find an increase in compliance or in manifestations of psychological reactance upon disclosure.

Our results also lend support to the generalizability and robustness of the effect. First, we demonstrated that the positive impact of transparency persists even in cases, when the pre-selected option implies a possible personal loss (namely spending more time working than one is paid for). Second, instead of the research volunteer sample used by Paunov et al. (Citation2018), we employed the services of a commercial panel. Research shows that the majority of panel workers are motivated by money (Paolacci, Chandler, & Ipeirotis, Citation2010), and the quantity of their participation is usually a function of payment (Litman, Robinson, & Rosenzweig, Citation2015). Nevertheless, the participants in our experiment chose to stay with the default at their own expense, especially so when the default’s purpose or target behavior was disclosed.

While our findings advocate transparency as a tool to increase default effectiveness, there are several limitations to their generalizability. First, a disclosure of the default’s purpose may not always benefit default participation. For instance, if the default purpose is perceived to be at odds with strong behavioral guides, such as social norms or moral mandates (Seiler, Citation2015), its disclosure can fail to produce the desired effect.

Second, if the purpose of a given default is interpreted as serving the default-setters´ vested self-interests instead of being benevolent (Steffel et al., Citation2016), no positive effects are expected.

Likewise, transparency may not increase compliance if the default contribution comes with inacceptable costs. As Bruns et al. (Citation2018) demonstrated, default effects on donation rates did not benefit from transparency, when the contribution was set to a very costly option. It seems that transparency affects the willingness to comply, but only within a given acceptance threshold. Whether that is indeed the case remains an open empirical question.

Another possible direction for future research is related to the mechanisms behind the individual disclosure contributions to compliance. Here, we provided some preliminary insight regarding the roles of endorser deceptiveness and disclosure argument strength. However, since these measures were not the main focus of our research, the evidence is exploratory and correlational. Therefore, further and more systematic investigation is pending, where, for instance, the variables are manipulated experimentally.

Conclusion

The present research re-affirms the positive effect of transparency on the effectiveness of default nudges. Our findings also provide an insight as to which transparency components are worth disclosing in a default setting. Importantly, we show that an ethical and theory-driven interpretation of the classic default nudge can increase compliance even in cases, where the desired behavior comes at a personal cost.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (238.3 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Moritz Ingendahl for his assistance in the online implementation of the research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Y.P.], upon reasonable request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In addition to the analysis on binary compliance decisions, we also ran an ordinary least squared regression with time spent as the criterion variable. For this purpose, the time categories were transformed to a continuous timescale ('<3 min' = 2, ‘3 to 5 min’ = 4; ‘5 to 7 min’ = 6; ‘7 to 9 min’ = 8; and ‘more than 9 min’ = 10), and regressed on the two Helmert contrasts. Besides the significant intercept, b = 5.00, SE = .11, t = 44.52, p < .001, the first coefficient was significant, b = 2.07, SE = .45, t = 4.64, p < .001, indicating that people in the default condition were willing to spend more time on research than people in the free-choice condition. The second coefficient, b = .92, SE = .43, t = 2.13, p = .034, was significant, too. Thus, participants accepted to spent more time when the default was made transparent than when it was not. Further pairwise comparisons revealed that disclosing the default’s general effect, M = 4.75, SD = 1.93, yielded similar donations as the mere default, M = 4.80, SD = 2.09, t(106) = .12, p = .91. However, clarifying the target behavior, M = 5.56, SD = 1.42), t(108) = 2.24, p = .027, and disclosing the default’s purpose, M = 5.95, SD = 1.27), t(101) = 3.33, p = .001, both significantly increased the amount of time spent on research as compared to the mere-default condition. Overall, the findings from the continuous regression model complement the main analysis, showing that transparency does not only increase default compliance, but also increases donation quantity. However, this interpretation has to be met with certain caution, since the transformation of a categorical dependent measure to a continuous one assumes equidistance of the categories.

References

- Allcott, H., & Mullainathan, S. (2010). Behavior and energy policy. Science, 327(5970), 1204–1205.

- Ansari, A., Essegaier, S., & Kohli, R. (2000). Internet recommendation systems. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(3), 363–375.

- Becker, L. (1978). Joint effect of feedback and goal setting on performance: A field study of residential energy conservation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63(4), 428–433.

- Bohm, J., & Hendricks, B. (1997). Effects of interpersonal touch, degree of justification, and sex of participant on compliance with a request. The Journal of Social Psychology, 137(4), 460–469.

- Bovens, L. (2009). The Ethics of Nudge. In T. Grüne-Yanoff. & S. O. Hansson (Eds.), Preference Change (pp. 207–219). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Brehm, W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. Oxford: Academic Press.

- Bruns, H., Kantorowicz-Reznichenko, E., Klement, K., Jonsson, M. L., & Rahali, B. (2018). Can nudges be transparent and yet effective? Journal of Economic Psychology, 65, 41–59.

- Chaiken, S., & Trope, Y. (Eds.). (1999). Dual-process theories in social psychology. New York: Guilford Press.

- Cialdini, R. (2016). Pre-suasion: A revolutionary way to influence and persuade. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Cialdini, R., & Goldstein, N. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology., 55, 591–621.

- Crano, W., & Prislin, R. (Eds.). (2008). Frontiers of social psychology. Attitudes and attitude change. New York: Psychology Press.

- Deci, E. (1975). Intrinsic motivation. New York: Plenum.

- Eagly, A., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

- Eisend, M. (2006). Source credibility dimensions in marketing communication–A generalized solution. Journal of Empirical Generalisations in Marketing Science, 10(2), 2–34.

- Faul, F, Erdfelder, E, Buchner, A, & Lang, A. (2009). Statistical power analyses using g*power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149-1160. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Felsen, G., Castelo, N., & Reiner, P. (2013). Decisional enhancement and autonomy: Public attitudes to-wards overt and covert nudges. Judgment and Decision Making, 8, 202–213.

- Friestad, M, & Wright, P. (1994). The persuasion knowledge model: how people cope with persuasion attempts. Journal Of Consumer Research, 21(1), 1-31. doi:10.1086/jcr.1994.21.issue-1

- Goldstein, N., Martin, S., & Cialdini, R. (2008). Yes!: 50 scientifically proven ways to be persuasive. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Hansen, P., & Jespersen, A. (2013). Nudge and the manipulation of choice: A framework for the responsible use of the nudge approach to behavior change in public policy. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 4(1), 3–28.

- Hovland, C., Janis, I., & Kelley, H. (1953). Communication and persuasion. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Hovland, C., & Weiss, W. (1951). The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opinion Quarterly, 15(4), 635–650.

- Johnson, E., & Goldstein, D. (2003). Do defaults save lives? Science, 302, 1338–1339.

- Jung, Y., & Mellers, A. (2016). American attitudes toward nudges. Judgment and Decision Making, 11(1), 62–74.

- Kinney, A., Richards, C., Vernon, S., & Vogel, V. (1998). The effect of physician recommendation on enrollment in the breast cancer chemoprevention trial. Preventive Medicine, 27(5), 713–719.

- Kirmani, A., & Campbell, M. (2009). Taking the target’s perspective: The persuasion knowledge model. In M. Wänke (Ed.), Social psychology of consumer behavior (pp. 297–316). New York: Psychology Press.

- Krijnen, J, Tannenbaum, D, & Fox, C. (2017). Choice architecture 2.0: behavioral policy as an implicit social interaction. Behavioral Science & Policy, 3(2), i-18. doi:10.1353/bsp.2017.0010

- Langer, E., Blank, A., & Chanowitz, B. (1978). The mindlessness of ostensibly thoughtful action: The role of” placebic” information in interpersonal interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(6), 635–642.

- Litman, L., Robinson, J., & Rosenzweig, C. (2015). The relationship between motivation, monetary compensation, and data quality among US-and India-based workers on mechanical turk. Behavior Research Methods, 47(2), 519–528.

- Loewenstein, G., Bryce, C., Hagmann, D., & Rajpal, S. (2015). Warning: You are about to be nudged. Behavioral Science & Policy, 1(1), 35–42.

- Marteau, M., Ogilvie, D., Roland, M., Suhrcke, M., & Kelly, M. (2011). Judging nudging: Can nudging improve population health? BMJ, 342, d228.

- McKenzie, C., Liersch, M., & Finkelstein, S. (2006). Recommendations implicit in policy defaults. Psychological Science, 17(5), 414–420.

- O’Keefe, D. (1997). Standpoint explicitness and persuasive effect: A meta-analytic review of the effects of varying conclusion articulation in persuasive messages. Argumentation and Advocacy, 34(1), 1–12.

- Paolacci, G., Chandler, J., & Ipeirotis, G. (2010). Running experiments on amazon mechanical turk. Judgment and Decision Making, 5(5), 411–419.

- Paunov, Y., Wänke, M., & Vogel, T. (2018). Transparency effects on policy compliance: Disclosing how defaults work can enhance their effectiveness. Behavioural Public Policy, 1–22.

- Petty, E., & Cacioppo, T. (1979). Issue involvement can increase or decrease persuasion by enhancing message-relevant cognitive responses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(10), 1915–1926.

- Ryan, M., & Deci, E. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

- Seiler, M. (2015). The role of informational uncertainty in the decision to strategically default. Journal of Housing Economics, 27(3), 49–59.

- Sher, S., & McKenzie, C. (2006). Information leakage from logically equivalent frames. Cognition, 101(3), 467–494.

- Smith, C., Goldstein, D., & Johnson, E. (2013). Choice without awareness: Ethical and policy implications of defaults. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 32(2), 159–172.

- Steffel, M., Williams, F., & Pogacar, R. (2016). Ethically deployed defaults: Transparency and consumer protection through disclosure and preference articulation. Journal of Marketing Research, 53(5), 865–880.

- Sunstein, C. (2015). The ethics of nudging. Yale Journal on Regulation, 32(2), 413–450.

- Thaler, R., & Benartzi, S. (2004). Save more tomorrow™: Using behavioral economics to increase employee saving. Journal of Political Economy, 112(1), 164–S187.

- Thaler, R., & Sunstein, C. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Van Der Pligt, J., & Vliek, M. (2016). The psychology of influence: Theory, research and practice. London: Routledge.

- Vogel, T., & Wänke, M. (2016). Attitudes and attitude change. London: Psychology Press.

- Wilson, E. J., & Sherrell, D. L. (1993). Source effects in communication and persuasion research: A meta-analysis of effect size. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 21(2), 101–112.

- Wood, W., & Quinn, J. (2003). Forewarned and forearmed? Two meta-analysis syntheses of forewarnings of influence appeals. Psychological Bulletin, 129(1), 119.