ABSTRACT

This study explored teacher leadership functions during and post-school disruption, due to COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were recruited from three primary government schools in Qatar, and included 12 teachers, three vice-principals (assistant principals) and three principals. A phenomenological research design was employed using semi-structured interviews for data collection. Findings suggest nine teacher leadership functions during school closure, two of which only were sustained post-school reopening. The study argues that the regression in teacher leadership functions relates to the failure in the internalization of teacher leadership cultural norms and values. The study offers recommendations for policy and practice.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic had an unprecedented impact on the various aspects of life, including education (Burgess & Sivertsen, Citation2020). The challenges that confronted schools were numerous, (Ghamrawi, Citation2022), and the pressure exerted on teachers was unparalleled (Pounder, Citation2022; Tourish, Citation2020; White, Citation2021). In this milieu, the pandemic paved the route for new roles for teachers, making them step into the front of the school cockpit, and taking the lead.

As such, one of the gains derived from the pandemic era was the proliferation of teacher leadership practices, functions, and roles (Aslan, Silvia, Nugroho, Ramli, & Rusiadi, Citation2020; Campbell, Citation2020; Chaaban, Sawalhi, & Du, Citation2022; DeMatthews, Knight, Reyes, Benedict, & Callahan, Citation2020; Ghamrawi & Tamim, Citation2022; Hill, Rosehart, St. Helene, & Sadhra, Citation2020; Hollweck & Doucet, Citation2020). In fact, COVID-19 gave rise to radical changes to the degree teachers led instruction and collaborated with their peers (DeMatthews et al., Citation2020), proving that critical initiatives are not always top-down (Ghamrawi, Citation2022). In this line, the conventional positional roles of middle and senior leadership teams were dismantled, ascribing more power and authority to teachers. In this paper, senior leadership entails roles carried out by principals, their vices (assistant principals are called academic vice principals in Qatar, or “vices” in short) and teams. Middle leadership relates to all positions that fall between senior leadership and classroom teachers. It includes subject leaders/coordinators, education supervisors, and similar positions.

In fact, during the pandemic, studies have reported new or enhanced roles for teachers, which comply with the international literature of teacher leadership (Aslan et al., Citation2020; DeMatthews et al., Citation2020; Hill et al., Citation2020; Hollweck & Doucet, Citation2020). Teachers were reported to be teaching in new modalities (Campbell, Citation2020), building the capacities of their colleagues in handling education technology (Aslan et al., Citation2020), continuously solving problems (Hollweck & Doucet, Citation2020), serving as curriculum specialists (Aslan et al., Citation2021), mentoring other teachers (Bush, Citation2021), and acting as catalysts for change (Harris, Citation2020).

A study conducted by Chaaban et al. (Citation2022) within the Qatari context, during the pandemic, assure that teacher leadership was exemplified through in-class and out-of-class initiatives. With their students, teachers were given a wider scope for making decisions and tailoring their instruction to the needs of their students. Likewise, those teachers played a more critical role with their peers, allowing them to act as content designers, change agents, professional development experts, and technology advocates.

However, crises are often expected after crisis management, meaning that after long endurance of a calamity, there are large chances that systems revert back to the norms they endorsed prior to the periods of disaster (Trump, Citation2012). In the same vein, Carrel (Citation2010) suggests that solid changes may not be realized, unless a culture is securely built during the crisis, then shaped, and sustained on the long term. Likewise, Boin and Hart (Citation2003) suggest that crises can potentially catalyze change, pushing problems into policy agendas; and the COVID-19 pandemic is no exception. However, not all of crises lead to reform, because “the outcome of the meaning-making process – the efforts to impose a dominant frame on a population – shapes the prospects of post crisis change” (p. 13).

As such, with the resumption of face-to-face schooling, it became important to explore the degree teachers in Qatar sustained teacher leadership functions and roles acquired during the pandemic. It was important to investigate whether teacher leadership has been further nourished, repressed, or somewhere in between. This study thus provides empirical evidence on the teacher leadership roles that have sustained in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Conceptualizing Teacher Leadership

Teacher Leadership has no clear-cut definition in the literature (Cosenza, Citation2015; Schott, Roekel, & Tummers, Citation2020). Some have restricted the term to formal leadership positions within the school system, such as Bolman and Deal (Citation1991) and Smylie and Brownlee-Conyers (Citation1992); others have associated it to functions centered on educational reform (Ghamrawi, Citation2010). Harrison and Killon (2007, cited in Ghamrawi, Citation2013b) suggest ten leadership roles for teacher leaders, including: “acting as resource providers, instructional specialists, curriculum specialists, classroom supporters, learning facilitators, mentors, school team leaders, and data coaches” (p. 149). This list seems to overlap partly or fully with many other studies, such as that of Lumpkin (Citation2016), Chen (Citation2022) and Bond (Citation2022).

Parallel to this, within the context of some Arab states, studies have shown that teacher leadership is not restricted to formal leadership positions. A large-scale study carried out in a P-12 setting by Ghamrawi (Citation2013b) within the Lebanese context suggested 15 teacher leadership roles. These included serving as a: (a) resource provider, (b) instructional specialist, (c) curriculum specialist, (d) classroom supporter, (e) learning facilitator, (f) mentor, (g) influencer, (h) data coach, (i) learner, (j) change agent, (k) student counselor, (l) community liaison, (m) cultural developer, (n) dexterous communicator, and (o) policy advocate.

Likewise, a study conducted by Chaaban et al. (Citation2022) within the P-12 Qatari educational context revealed teacher leadership roles that are not attributed to formal leadership positions. These were enacted through: (a) an engagement in extensive individual learning opportunities; (b) establishment of new routes for communication with various stakeholders; (c) an engagement in intensive peer learning opportunities; (d) the initiation of agentic teacher leadership roles; and (e) an engagement in self-reflective practice.

In other words, and in broader terms, teacher leadership extends the influence of teachers beyond the walls of their classrooms, allowing them to impact the wider school community at different scopes and levels. Despite the different terminologies, classification or categorization of functions for informal teacher leadership in the literature, they all describe teachers who contribute to school reform initiatives, without leaving their classrooms (Cherkowski, Citation2018; Harris, Citation2020; Harris & Jones, Citation2020).

This paper endorses the concept of teacher leadership as being a function and not a position. As such, teacher leadership is not considered to be associated with formal titles, positions, or authority (Warren, Citation2021; Youngs & Evans, Citation2021).

Benefits of Teacher Leadership

Despite the divergence of the literature in conceptualizing teacher leadership, studies converge on teacher leadership benefits, and the positive impact it leaves on schools, at the student and teacher levels (Friesen & Brown, Citation2022). In fact, many advantages have been reported for teacher leaders both inside (Warren, Citation2021) and outside (Cosenza, Citation2015) the boundaries of their classrooms.

Within their classrooms, teacher leaders are champions of students’ learning (Ghamrawi, 2013), supporting improved learning outcomes (Warren, Citation2021). In this context, teachers strategize learning opportunities for students and customize them based on their needs, by productively utilizing their assessment data, learning styles, and preferences (Walters, Citation2022). They tend to build student capacities, giving them a rationale for learning, and hence contribute to instill in them the desire to be lifelong learners (Ghamrawi, Citation2013b; Walters, Citation2022). Thus, through their leadership roles inside their classrooms, teacher leaders affect positively student learning outcomes (Ghamrawi, Citation2011; Lumpkin, Citation2016).

On the other hand, by offering services to colleagues within the school at many levels, and in so many ways, teacher leadership contributes to school improvement initiatives (Muijs & Harris, Citation2006; Murphy, Citation2005; Poekert, Citation2012; Shen et al., Citation2020). This is achieved through the role played by teacher leaders in the creation of positive school cultures (Harris, Citation2005), by acting as role models for other teachers (Muijs & Harris, Citation2006), serving as risk-takers (Ghamrawi, Citation2013b), and supporting school-based professional development initiatives (Shen et al., Citation2020).

Barriers to Teacher Leadership

According to Ghamrawi (Citation2011), trust is an essential element for the establishment of teacher leadership. It supports teachers in confronting the barriers that are often associated with its nourishment, as per the literature (Demir, Citation2015). Trust is considered as a key catalyst for teacher collaboration, promoting passion for professionalism, collegial dialogue, collective problem-solving, risk-taking, community building, and commitment to continuous improvement and growth (Ghamrawi, Citation2011). A quick comparison between these elements and the functions attributed to informal teacher leadership, discussed earlier, shows that teacher leadership is less likely to prevail in cultures where trust is missing.

On the other hand, teacher leadership would not cultivate in educational contexts where leadership is not distributed (Bush, Citation2015). With localized leadership models, where the authority is confined to a single person within the school system, teacher leadership is less likely to develop (Youngs & Evans, Citation2021). Distributed leadership and democratic leadership styles are pre-requisites for teacher leadership development (Ghamrawi, Citation2011; Bush, Citation2015).

Finally, negative or toxic school cultures constitute real threats on teacher leadership, in terms of both development and sustainability (Ghamrawi, Citation2011; Bush, Citation2015). Toxic school cultures are predominated by insecure feelings for teachers due to various reasons, such as ineffective leadership, favoritism, inequality, lack of justice, poor communication, embarrassing behaviors, and lack of appreciation (Carpenter, Citation2015; Deal & Peterson, Citation2010). Such cultures inhibit teacher creativity (Harris, Citation2005, Sawalhi & Sellami, Citation2021), decrease their willingness to act as risk-takers (Ghamrawi, Citation2011), and inhibit their participation and collaboration in school wide initiatives (Harris, Citation2005, Sawalhi & Sellami, Citation2021).

Fostering Teacher Leadership in Schools

Nguyen, Harris, and Ng (Citation2019) highlight five elements as essential for teacher leadership development including “school culture, school structure, principal leadership, peer relationships and person-specific factors” (p. 68). School culture has been highlighted in seminal reviews on teacher leadership as key for fostering teachers’ development and preparation for the teacher leader role (Wenner & Campbell, Citation2017; York-Barr & Duke, Citation2004). Hunzicker (Citation2017) and Pineda-Báez, Bauman, and Andrews (Citation2020) consider the school culture as a factor associated with early-career teachers’ professional learning. They suggest that such cultures are crafted by school principals and are strengthened by the positive professional relationships with peers.

In the same vein, according to the literature, cultures that support the provision of teacher leadership, facilitate teacher leaders’ involvement in school-wide focus on learning, inquiry, and reflective practice (Ghamrawi, Citation2011; Katzenmeyer & Moller, Citation2009; Sebastian, Huang, & Allensworth, Citation2017; Stein, Macaluso, & Stanulis, Citation2016; Szeto & Cheng, Citation2017). For example, Sinha and Hanuscin (Citation2017), explored the process via which three teachers developed into teacher leaders through their involvement in whole-school projects and inquiry. Throughout their involvement in the project implementation, those teachers were acknowledged by their school principals, and supported through their positive relationships with peers. Findings from Sinha and Hanuscin (Citation2017) seem to converge with Crowther, Ferguson, and Hann (Citation2009), Katzenmeyer and Moller (Citation2009), and Visone (Citation2018, Citation2022) who stress the importance of relationships among teachers, and the principals’ actions and leadership styles. However, they also suggest that the organizational structures of schools, as suggested by Nguyen et al. (Citation2019), could diminish or increase the chances of teacher leadership development. In fact, “a supportive, transparent, and flexible structure is an important condition that fosters teacher leadership and allows innovation to flourish and grow because teachers” contribution is recognized and valued’ (Nguyen et al., Citation2019, p. 17). This echoes with several other studies in the literature that stress the importance of flattening hierarchies, thus promoting collaborative cultures conducive for making initiatives, taking risks, and hence empower teachers to lead (Ghamrawi, Citation2010, Citation2011).

Moreover, the development of teacher leadership has been linked by Nguyen et al. (Citation2019) to person-specific factors, which are categorized into teacher leaders’ content and procedural knowledge (Firestone & Martinez, 2007, cited in Nguyen et al., Citation2019), as well as motivation (Margolis & Deuel, 2009, cited in Nguyen et al., Citation2019). In fact, even when a positive school culture is secured, with weak content and procedural knowledge, teachers may not develop into teacher leaders. This is because they lack the skills and competencies that would allow them to take part in projects, and hence collaborate with peers. Likewise, unmotivated teachers may decline from joining professional communities that are supported by cultures that are conducive for teacher leadership development.

On the other Ghamrawi (Citation2010, Citation2013a) suggests that subject leaders (subject coordinators) play an essential role in developing and nurturing teacher leadership in schools. She suggests that “subject leaders” role is far more critical than that of school principals in inaugurating and cultivating teacher leadership’ (Ghamrawi, Citation2013a, p. 148). This was attributed to the fact that middle leaders in general, and subject leaders in particular were carrying out tasks that are traditionally attributed to senior leaders (Bush, Citation2008; Ghamrawi, Citation2010). Ghamrawi (Citation2010) suggests three spheres of influence through which subject leaders contribute to teacher leadership development including (a) the development of sub-cultures of professional collaboration and distributed leadership; (b) establishing bartered leadership structures; and (c) walking the talk of a shared system of monitoring and evaluation. So the same way school principals craft school cultures, subject leaders shape departmental sub-cultures which reinforce or oppose the overall school culture. Moreover, they are the ones who create the opportunities for teachers to lead, by giving the chance for all teachers to exchange positions and roles they overtake when collaborating on projects. Finally, when it comes to teacher appraisal, subject leaders can either take teacher leadership to a new level, or destruct it completely. In fact, “subject leaders who succeed in creating non-threatening systems of monitoring and evaluation that ensure teacher empowerment sustain their efforts in building teacher leadership capacity” (Ghamrawi, 210, p. 319).

Context of the Study

Schools in Qatar are of two types: public (governmental) and private. Public schools are funded by the government, and strictly follow the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MOEHE) in all details (Nasser, Citation2017). However, private schools are self-funded and enjoy more freedom in making decisions pertaining the education they offer to their students. They are obliged to offer three subjects as literally prescribed by the MOEHE and these are Arabic language (for Arabic speaking children), Islamic studies (for Muslim children), and History of Qatar for all children enrolled in school. This study is focused on public schools. The opportunities for teacher leadership in private schools vary from those made available for public school teachers.

When schools in Qatar were disrupted in March 2020 in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, as was the case with almost all schools across the globe, the MOEHE took quick steps to shift schooling into online learning modes. Several initiatives were made so as to ensure continuity of learning. These included the development of video-recorded lessons, targeting students from all grade levels and in all subjects; as well the launching of an online learning platform allowing for synchronous and asynchronous digital learning (Chaaban et al., Citation2022).

While the role of MOEHE in the public school system is extensive, its role is only regulatory in the case of private schools (Sawalhi & Sellami, Citation2021). In fact, the MOEHE regulates almost everything in public schools, and school principals’ role is devoted to fulfillment of decrees and circulars that the MOEHE shares with them. Being more autonomous, some private schools took the lead in constructing learning opportunities for their students, with greater autonomy; however, adhering to rules and decisions set by the MOEHE (Chaaban et al., Citation2022).

As stated earlier, a study conducted during the pandemic by Chaaban et al. (Citation2022) in primary Qatari schools suggested that teachers were assuming teacher leadership roles. Findings from public schools differed significantly from private schools. There was a disparity in teacher leadership practice amongst private schools: some of those schools supported and nourished teacher leadership prior to school disruption; whereas others did not. This is because private schools in Qatar enjoyed a larger margin of freedom than their public counterparts, which were under rigorous mandate of the MOEHE. The key teacher leadership roles confirmed through Chaaban et al.’s (Citation2022) study were centered on engagement in personal and peer learning around digital content.

With the resumption of face-to-face schooling, the researchers were interested in investigating the degree teachers sustained the teacher leadership roles they assumed during school closure, due to the pandemic.

Research Methodology

Research Design

The current study investigated the perspectives of teachers pertaining the sustained teacher leadership roles assumed during school closure. The decision was made to focus on public schools which all fell under the direct leadership of MOEHE, and school leadership in all of these schools followed the same contextual and structural factors.

The researchers adopted qualitative phenomenology as an approach for gaining insight into the lived experiences of teachers in schools as recommended by Vagle (Citation2018). The researchers adopted a reflective and inductive methodology that involved garnering insight into participants’ lived experiences, during and post school closure, as they recollected them.

Gaining Access

The researchers gained initially the permission of the Qatari Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MOEHE) by submitting an application for conducting the study, clarifying its purpose, how data would be used and stored, and assurances of anonymity of participants. A copy of the research instrument was attached to the application. After the consent of the MOEHE, the researchers gained the approval of the ethics committee at the University they were affiliated with, after which they addressed schools.

Participants

Purposeful sampling was employed to recruit participant schools in this study. According to Palinkas et al. (Citation2015), “purposeful sampling is used for the identification and selection of information-rich cases related to the phenomenon of interest” (p. 1). In this study, the selection was made purposefully from public schools only, bearing same features in terms of type and size (primary and almost of the same size). Primary schools were chosen because earlier studies on such schools exist, confirming the nourishment of teacher leadership during COVID-19. E-Mails were sent to 12 primary public schools whose student size ranged between 500–650, and the intention was to select the first three to respond. Consequently, three schools were recruited to take part in the study, as they were the only schools interested in taking part. General information about the three schools is presented in .

Table 1. General information about participant schools.

Each school was requested to nominate up to four teachers to take part in this study alongside the principal and/or the assistant principal (called academic vice principal in Qatar, or just “vice” in short). In fact, school principals were asked to nominate four of the teachers in their schools that remarkably supported other teachers during the pandemic, through exchange of information and advice on various aspects of learning and teaching under the “new norm” of schooling. As such, the sample was comprised of 12 primary school teachers, three vice principals, and three school principal (N = 18). presents the participants from each school.

Table 2. Participants per schools taking part on the study.

The data from the school principals and vice principals were used to validate the findings and provide a deeper understanding of the provision of teacher leadership.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data was collected through focus group interviews. An interview schedule was developed for teachers and another for principals and their vices. In each of the researched schools, a focus group interview was carried out with four teachers, and another one was conducted with the principal and his/her vice, for validation purposes. Thus, data for this study was collected through three focus group interviews with teachers, and three focus groups with principals and their vices.

Teachers’ focus group interview invited them to describe their lived experiences during and post COVID-19 closure in six areas, as presented in .

Table 3. Focus group interview schedule.

The choice of the above six areas was made on the basis of an earlier study carried out by Chaaban et al. (Citation2022) within the same context. Their study suggested that the above six areas witnessed teacher leadership nourishment during COVID-19 pandemic.

Parallel to the above areas addressed through focus group interviews, the teachers’ lived experiences were also investigated through the lens of school principals and their vices to validate data.

Each focus group interview with teachers took approximately 45 minutes, while that of principals and their vices consumed 20 minutes, on the average. All interviews were recorded after gaining acceptance from the concerned interviewees (Coe, Waring, Hedges, & Ashley, Citation2021). One of the researchers carried out all interviews, respecting social relations underpinning qualitative interviews, allowing individuals to expand on their responses to questions with no interference (Döringer, Citation2021; Jones, Citation2020).

Interview data was then transcribed word-by-word by the other researcher to avoid missing any of the ideas suggested by interviewees (Deterding & Waters, Citation2021). Transcriptions were then analyzed using thematic analysis using (1) open coding, (2) axial coding, and (3) selective coding allowing for the construction of meaning using the themes embedded in the collected data (Williams & Moser, Citation2019).

Findings

Thematic analysis of teacher interview data reflected several themes, and are presented in . Themes are presented per the six investigated areas of the interview schedule. They are discussed in more details below.

Table 4. Themes derived from thematic analysis of interview data with teachers and principals and their vices.

Services Offered to Students

According to participants, they were playing three key functions in relation to student services during school closure: curriculum enrichment, creativity and innovation, and making initiatives. In fact, the urge to broaden learning opportunities for students pushed teachers to work on enriching the curriculum. This enrichment took many shapes including designing reinforcement activities, developing remedial tasks, and creating learning opportunities that respond to the new learning context (learning from home).

The need to develop learning resources was urgent and sudden and was inspired by the need to attract students sitting at their homes behind screens. (T3, School A).

Parents’ support was limited during the pandemic and to ensure that each student was on board, we had to develop remedial programs (T1, School C).

One of the things I personally learned during the pandemic how to make students use local material that was available for them at their homes and their surroundings (T4, School B).

It was a totally new landscape for me and other teachers. We were learning ourselves in order to support the learning of our students (T4, School A).

Moreover, teachers believed that their level of creativity and innovation hit a record during the pandemic. They found themselves creating videos, which they believed they would have never thought of producing. The assignments they gave to students were themselves innovative and were responsive to the new context.

Well suddenly, I became a movie producer, where I found myself releasing my creativity and pitching up my skills to a new level. (T1, School A).

The assignments I developed were very creative and unlike the traditional ones that I used to use in class. (T3, School B).

Finally, teachers believed that they exhibited initiative during closure. They thought they were doing what needed to be done, as opposed to what they were supposed to do.

School closure made me feel for the first time that I was on mission to respond to student needs in practice and not in theory (T2, School A).

However, these functions do not seem to be sustained upon schools’ re-opening. All teachers said that they had to “follow exact directions again.”

When back in face-to-face mode of schooling, we are back to the same rules and the same directions we always had to follow prior to pandemic (T1, School B).

When we returned to school, we are back to the routine we always abided by. There is a curriculum that needs to be covered. (T2, School B).

Interestingly, principals and their vices were aware that the newly acquired teacher functions exhibited by teachers during school closure have been regressed. In fact, they found this to be normal simply because the “school re-opened.” However, they believed that teachers’ innovation in the classroom continues to prevail, without describing how that would be happening.

The teacher is a leader for her classroom, and there is no limit for innovation in methods of teaching. However, we are strictly audited by the ministry and the mode of work is back to normal and all of us in school need to respectful of that (Pr, School A).

While teachers need to strictly follow the curriculum, innovation continues (PR, School B).

Teachers did a good job during the pandemic, especially during its beginning and proved to be very devoted to their careers. However, once back to normal, they had to revert back into what is expected from them as per the governing rules and regulations (Pr, School C).

Use of Technology

All participant teachers believed that they were continually learning around technology the moment school closure was announced, and continued to do so thereafter. This supported them in becoming proficient in using technology to the level where they became able to support other teachers.

If you tell me before COVID-19 that I will be developing videos and PowerPoint Slides using technology efficiently, I would not have believed you (T1, School A).

My main gain out of the pandemic is definitely technology literacy (T4, School B).

I think I supported many of my colleagues in using technology during the pandemic (T2, School C).

The digital skills acquired by teachers during school closure are believed to be sustained after schools’ re-opening, as per both teachers and senior leadership.

I continue to use technology post the pandemic because I believe it is no more something I fear, but rather a way of making my work easier (T3, School B).

Technology is a gain for all teachers and we emphasize keeping it used by them (VP, School A).

We all got our technological skills enhanced during the pandemic, and I ensure that all of us in this school continue to use it diligently (PR, School C).

Professional Growth

Teachers suggested that they grew professionally during the closure by virtue of coaching teachers or being coached by other teachers. Besides, they believed that they were responding to unprecedented contextual changes that affected their careers. As a result, they believed that they were supporting change in the way the curriculum was being delivered. This had a great impact on their growth professionally, as they were learning by doing. At the same time, their self-efficacy was leveraged consequently.

I supported many of my colleagues professionally and helped them solve many problems confronting them and this made me feel so proud about myself (T4, School A).

There is no professional growth more powerful than the one you get when you learn by doing, and when you experiment while you need the result to build on it (T3, School C).

However, this approach for professional growth did not seem to endure upon school re-opening, as per both teachers and senior leaders. They thought that the reason was the lack of time for teachers to practice service toward other teachers, or to grow professionally through working on delivering the curriculum in original ways. Despite that, teachers still felt positive about their experience during school closure.

When back in school my role in supporting other teachers was stopped, because there are ways how things happen and we are back to it (T4, School C).

My role as a coach and mentor to other teachers especially the ones who were not so good in using technology has stopped when we returned to school (T1, School B).

Teachers in schools work differently than they were doing during the pandemic. The context and conditions have changed. They are now soaked with obligations and cannot afford supporting other teachers. We have supervisors to help teacher and they come from the ministry (PR, School A).

Teachers who love to support other teachers may continue to do so. However, the burden would be massive. That is why it was way diminished when back in school (VP, School C).

Teachers always work together but they are limited with time when teaching is administered at school. With online learning, they had more time to work together from distance (PR, School C).

Collaboration

Collaboration was one of the many functions teachers were carrying out during school closure, which took many forms, including working in teams, exhibiting collective inquiry around issues of common interest, and belonging to communities of practice. Teachers believed that working in teams was never as essential and integral as was the case during school closure. They spontaneously found themselves inquiring collectively around how best they could offer learning opportunities for their students. In doing so, teachers belonged to virtual learning communities.

It is the first time I got to experience real collaboration with my colleagues. We were truly dividing tasks, experimenting and then making discussions around that (T1, School A).

As members of one department, we collaborated on lesson plans, videos and games to respond to students’ needs (T3, School B).

Yet, this collaboration has been regressed after schools re-opened as per teachers, attributing this to the lack of common time.

When back in school, our beautiful meetings stopped because we no more have time to do so (T2, School C).

Face-to-face back in school teaching forced us to give up on the collaboration around lesson planning and material development because the school day does not allow for accommodating this (T2, School A).

However, school principals thought that their teachers were collaborating always, irrespective of school closure or opening. They did not seem to be speaking the same language about collaboration, that the teacher used. In fact, to them collaboration meant meeting together during coordination sessions or in school assemblies. Contrarily, teachers viewed collaboration in terms of three aforementioned functions.

Teaching is all about collaboration. Our teachers collaborate in all cases online and face-to-face (VP, School A).

Our teacher continue to work together, maybe a bit less because of their tight schedules, but they do collaborate (PR, School B).

Delegation by School Leadership

According to teachers, school closure gave them a margin for contributing to decision making around instruction. They thought that school leadership were more flexible around ministerial directives, which were less restrictive than usual.

School closure gave us a bigger say in decisions around our delivery (T3, School B).

I think all people at the ‘top’ were more flexible during the pandemic. This allowed us to make initiatives better (T4, School C).

However, this flexibility was reported to have regressed after school re-opening by teachers. Principals, on the other hand, used a very poetic “cliché” language that teachers continue to serve as masters for their classes.

We do have tighter directives again, when back in school; but this does not mean they are cannot innovate and create (VP, School C).

Teachers manage and lead their classrooms. When their door is closed, they can still innovate (PR, School A).

Parental Engagement

Parental involvement and strengthened communication are among the sustained gains of school closure through the lens of both teachers and senior leadership. In fact, schools devised new routes for reaching parents during closure, primarily based on technology.

We have numerous number of ways to reach parents now with the help of technology. There are parents whom we got to know only during the pandemic by virtue of these technologies. (T1, School B).

I am happy that technology has taught us and the parents that there are ways to collaborate even if they are too busy. This collaboration using these technologies has never stopped after the pandemic (T1, School A).

Thanks to the pandemic, which taught parents how to be more involved in their kids’ learning. I guess they are now keeping that habit (PR, School C).

Discussion

Many studies addressed teacher leadership development during the pandemic, however, to the knowledge of the researchers, very few assessed the sustained teacher gains post school resumption. This study explored the status quo of teacher leadership after school resumption of face-to-face learning. Teachers were described at the beginning of this paper to be seated at the cockpit, during COVID-19, trying to maintain a safe journey by utilizing their skills and competencies that have long been partially used, misused, or not used at all for a variety of reasons. Unfortunately, this study closes by suggesting that teachers were back in the passengers’ seats with no influence on where their planes were heading.

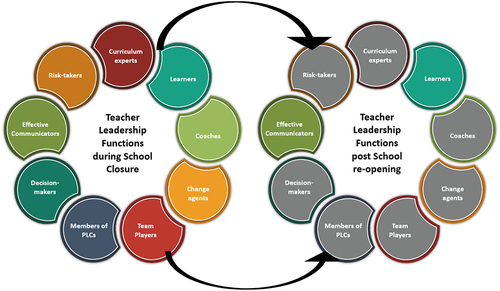

Findings from this study converge with that of Chaaban et al. (Citation2022), suggesting that during school closure teachers in Qatar were assuming teacher leadership roles. In fact, teachers were carrying out roles that closely simulated the roles attributed to teacher leaders in the international literature. Teachers were serving as: (a) curriculum experts (Bush, Citation2020; Lumpkin, Citation2016); (b) continuous learners (Friesen & Brown, Citation2022) of technology; (c) coaches for other teachers (DeMatthews et al., Citation2020); (d) change agents (Chen, Citation2022; Cosenza, Citation2015); (e) effective team players (Ghamrawi, Citation2013b); (f) members of professional learning communities (Bush, Citation2021); (g) participants in decision-making (Ghamrawi, Citation2013a); (h) effective communicators (Aslan et al., Citation2020); and (i) risk-takers (Ghamrawi, Citation2013b).

However, teacher leadership functions and roles did not seem to be fully sustained post school re-opening. presents teacher leadership functions and attributes assumed during school closures, highlighting the ones that were sustained post school re-opening. In this figure, which translates into a visual representation, the 17 functions has been downsized into 9 by labeling common functions with a generic title, in order to ease discussion. For example, the title “coaches” encompasses two functions, which are “supporting other teachers in technology use” and “coaching other teachers.”

As displays, most of the teacher leadership functions assumed during school closure were regressed. Only two of the teacher leadership functions were sustained, mainly teachers’ roles as continuous learners, particularly in technology, as well as their roles in communicating with parents via the applications developed for that purpose during school closure. Teachers involved in this study suggested that amongst other roles they acquired during the pandemic, those were the only two key functions they continued to hold. In other words, teacher leadership functions that sustained post reopening of schools were technology-related. The regression in teacher leadership post school reopening comes parallel to Trump’s (Citation2012), Carrel (Citation2010), and Boin and t’Hart (Citation2022) findings, who suggest that crisis management is not enough to sustain initiatives launched during those crises. If a system fails to establish a culture that safeguards the gains during a crisis, then this system is more prone to losing those gains. This comes parallel to many studies in the literature that underscore the integral role played by school cultures in promoting and sustaining teacher leadership such as Katzenmeyer and Moller (Citation2009), Ghamrawi (Citation2011), Stein et al. (Citation2016), Szeto and Cheng (Citation2017), and Sebastian et al. (Citation2017).

That is to say, teacher leadership functions regressed once face-to-face schooling resumed, because those functions were not internalized via a culture, nor institutionalized through ministerial policies and decrees. Teacher leadership functions nourished based on a contextual need, and ceased to exist with resumption of the regular mode of schooling. No actions were taken in order to contain, maintain, and sustain these functions. Perhaps, the fact that the MOEHE supported a bigger margin of school autonomy during the pandemic, contributed to the development of teacher leadership. Yet, with the resumption of in-person schooling, it seems that the MOEHE resumed its regular role in full, obliterating that limited margin of freedom, it once made available for teachers, during the pandemic.

Moreover, as per the revised literature, teacher leadership nourishment requires the establishment of structures that safeguard teacher leadership (Ghamrawi, Citation2010, Citation2011; Nguyen et al., Citation2019). In the absence of flexible and transparent structures that encourage risk-taking, teacher leadership is less likely to nourish (Ghamrawi, Citation2010, Citation2011; Nguyen et al., Citation2019). Parallel to this literature, it may be argued that schools participating in this study did not create the structures that are conducive for teacher leadership sustenance. This eventually led to the regression of teacher leadership functions once the pandemic was over. This is because such functions lacked any robust foundation, and flourished just because of a margin of freedom emanated from the MOEHE who decided to retrieve once the pandemic was over.

In the same vein, the only sustained teacher leadership functions were technology-related, including digital tools for learning, and others for communication with parents. This can be justified in terms of the investment in technology made at the level of the ministry, coming along with policies that urge schools to continue utilizing them. Such policies developed by the MOEHE seemed to have supported the creation of the culture conducive for the survival of these functions.

To put back teachers in the cockpits, autocratic/authoritarian top-down leadership needs to be addressed in schools. More democratic forms of leadership needs to prevail, promoting trusting relations and positive school cultures that are conducive for teacher leadership nourishment again. However, this may not happen unless schools and school principals are offered margins of freedom by education authorities. At the end, no school can give what it does not have.

Conclusion

While crisis are often regarded precarious, perilous, and foster deviations from order, they also offer opportunities, by creating new schemes or roles. In fact, crisis can potentially escort to rapid problem solving and innovation, leading to new levels of cooperation, allowing individuals with the right skill sets and talent to lead, even if they were never identified as leaders prior to the crisis.

However, systematic change cannot modify or replace long-held norms and beliefs, unless it is supported by bold and extraordinary policy moves, which in essence support the internalization of a culture that reinforces and maintains the new set of norms and beliefs. This study displays typically an example of how the failure to internalize a culture leads to reversing a paradigmatic reform backwards, bringing it to where it was prior to the crisis. The adoption of key teacher leadership functions was not safeguarded by policies that lead to the aforementioned cultural internalization. As such, the acquired teacher leadership functions were dropped and rebuffed as soon as the crisis was over.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

This study was limited by the small sample size deployed for the purpose of the study. Being qualitative in nature, the rigor of the study was secured by the thick descriptions offered to readers pertaining all its steps. The study would have benefited from quantitative surveying prior to qualitative interviewing, as it would have brought to the reader the needed breadth for the study (Coates, Citation2021). Thus, the researchers recommend surveying a larger sample in future research endeavors.

Moreover, addressing different school levels within the Qatari educational context would be a benefit. Data from middle and secondary schools would support deeper findings and conclusive verdicts. As such, the researchers recommend carrying out phenomenological studies involving middle and secondary school teachers.

Recommendations for Policy and Practice

The milestones accomplished during school closure in Qatar in terms of teacher leadership development and nourishment were quite promising, as this study suggests. However, this achievement was not sustained upon school reopening, leading to regression in teacher leadership roles and functions. One potential reason was that teacher leadership development was not intentional, but rather spontaneous and responsive to contextual needs. Thus, it was an unplanned happening, and hence lacked the needed scaffolding to maintain it after schools’ reopening.

Given that teacher leadership is considered as a key stone for any educational reform (Ofsted, Citation2000, cited in Ghamrawi, Citation2013b), and the fact that the MOEHE is proactively looking for opportunities to reforming education in Qatar, the researchers recommend the development of policies by MOEHE that nurture teacher leadership in governmental schools. Such policies should allow teachers to have common time for collaboration and collective inquiry with each other. They should also contribute to the establishment of positive cultures where teachers would feel trusted and hence safe to take risks. This means reinforcing distributed forms of leadership in schools, and increasing the margins of freedom for teacher in and out of their classrooms.

Ethical Approval

The manuscript received ethical approval of Qatar University Institutional Review Board (QU-IRB). The approval number is QU-IRB 1751-EA/22.

Acknowledgments

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aslan, A., Silvia, S., Nugroho, B. S., Ramli, M., & Rusiadi, R. (2020). Teacher’s leadership teaching strategy supporting student learning during the COVID-19 disruption. Nidhomul Haq: Jurnal Manajemen Pendidikan Islam, 5(3), 321–333.

- Boin, A., & Hart, P. T. (2003). Public leadership in times of crisis: Mission impossible? Public Administration Review, 63(5), 544–553.

- Boin, A., & t’Hart, P. (2022). From crisis to reform? Exploring three post-COVID pathways. Policy and Society, 41(1), 13–24.

- Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (1991). Leadership and management effectiveness: A multi-frame, multi-sector analysis. Human Resource Management, 30(4), 509–534.

- Bond, N., (Ed.). (2022). The power of teacher leaders: Their roles, influence, and impact. UK: Routledge.

- Burgess, S., & Sivertsen, H. (2020). Schools, skills, and learning: The impact of COVID-19 on education. Retrieved from https://voxeu.org/article/impact-covid-19-education

- Bush, T. (2008). Leadership and management development in education. Leadership and Management Development in Education, 1, 1–184.

- Bush, T. (2015). Teacher leadership: Construct and practice. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 43(5), 671–672. doi:10.1177/1741143215592333

- Bush, T. (2020). Theories of educational leadership and management. Theories of Educational Leadership and Management, 1–208.

- Bush, T. (2021). Leading through COVID-19: Managing a crisis. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 49(3), 373–374. doi:10.1177/1741143221997267

- Campbell, P. (2020). Rethinking professional collaboration and agency in a post-pandemic era. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 5(3/4), 337–341. doi:10.1108/JPCC-06-2020-0033

- Carpenter, D. (2015). School culture and leadership of professional learning communities. International Journal of Educational Management, 29(5), 682–694.

- Carrel, P. (2010). The handbook of risk management: Implementing a post-crisis corporate culture. UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Chaaban, Y., Sawalhi, R., & Du, X. (2022). Exploring teacher leadership for professional learning in response to educational disruption in Qatar. Professional Development in Education 48(3), 426–443.

- Chen, J. (2022). Understanding teacher leaders’ behaviours: Development and validation of the teacher leadership inventory. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 50(4), 630–648.

- Cherkowski, S. (2018). Positive teacher leadership: Building mindsets and capacities to grow wellbeing. International Journal of Teacher Leadership, 9(1), 63–78.

- Coates, A. (2021). The prevalence of philosophical assumptions described in mixed methods research in education. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 15(2), 171–189. doi:10.1177/1558689820958210

- Coe, R., Waring, M., Hedges, L. V., & Ashley, L. D., (Eds.). (2021). Research methods and methodologies in education. London: Sage.

- Cosenza, M. N. (2015). Defining teacher leadership: Affirming the teacher leader model standards. Issues in Teacher Education, 24(2), 79–99.

- Crowther, F., Ferguson, M., & Hann, L. (2009). Developing teacher leaders: How teacher leadership enhances school success . USA: Corwin Press.

- Deal, T. E., & Peterson, K. D. (2010). Shaping school culture: Pitfalls, paradoxes, and promises. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- DeMatthews, D., Knight, D., Reyes, P., Benedict, A., & Callahan, R. (2020). From the field: Education research during a pandemic. Educational Researcher, 49(6), 398–402. doi:10.3102/0013189X20938761

- Demir, K. (2015). The effect of organizational trust on the culture of teacher leadership in primary schools. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 15(3), 621–634.

- Deterding, N. M., & Waters, M. C. (2021). Flexible coding of in-depth interviews: A twenty-first-century approach. Sociological Methods & Research, 50(2), 708–739. doi:10.1177/0049124118799377

- Döringer, S. (2021). ‘The problem-centred expert interview.’ Combining qualitative interviewing approaches for investigating implicit expert knowledge. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 24(3), 265–278. doi:10.1080/13645579.2020.1766777

- Friesen, S., & Brown, B. (2022). Teacher leaders: Developing collective responsibility through design-based professional learning. Teaching Education, 33(3), 254–271.

- Ghamrawi, N. (2010). No teacher left behind: Subject leadership that promotes teacher leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 38(3), 304–320. doi:10.1177/1741143209359713

- Ghamrawi, N. (2011). Trust me: Your school can be better—A message from teachers to principals. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 39(3), 333–348. doi:10.1177/1741143210393997

- Ghamrawi, N. (2013a). In Principle, It Is Not Only the Principal! Teacher Leadership Architecture in Schools. International Education Studies, 6(2), 148–159. doi:10.5539/ies.v6n2p148

- Ghamrawi, N. (2013b). Teachers helping teachers: A professional development model that promotes teacher leadership. International Education Studies, 6(4), 171–182.

- Ghamrawi, N. (2022). Teachers’ virtual communities of practice: A strong response in times of crisis or just another Fad? Education and Information Technologies, 27(5), 5889–5915.

- Ghamrawi, N., & M Tamim, R. (2022). A typology for digital leadership in higher education: The case of a large-scale mobile technology initiative (using tablets). Education and Information Technologies, 1–22.

- Harris, A. (2005). Teacher leadership: More than just a feel-good factor? Leadership and Policy in Schools, 4(3), 201–219.

- Harris, A. (2020). COVID-19–school leadership in crisis? Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 5(3/4), 321–326. doi:10.1108/JPCC-06-2020-0045

- Harris, A., & Jones, M. (2020). COVID 19–school leadership in disruptive times. School Leadership & Management, 40(4), 243–247. doi:10.1080/13632434.2020.1811479

- Hill, C., Rosehart, P., St. Helene, J., & Sadhra, S. (2020). What kind of educator does the world need today? Reimagining teacher education in post-pandemic Canada. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(4), 565–575. doi:10.1080/02607476.2020.1797439

- Hollweck, T., & Doucet, A. (2020). Pracademics in the pandemic: Pedagogies and professionalism. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 5(3/4), 295–305. doi:10.1108/JPCC-06-2020-0038

- Hunzicker, J. (2017). From teacher to teacher leader: A conceptual model. International Journal of Teacher Leadership, 8(2), 1–27.

- Jones, C. (2020). Qualitative interviewing. Handbook for research students in the social sciences. UK: Routledge.

- Katzenmeyer, M., & Moller, G. (2009). Awakening the sleeping giant: Helping teachers develop as leaders. USA: Corwin Press.

- Lumpkin, A. (2016). Key characteristics of teacher leaders in schools. Administrative Issues Journal: Connecting Education, Practice, and Research, 4(2), 14.

- Muijs, D., & Harris, A. (2006). Teacher led school improvement: Teacher leadership in the UK. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(8), 961–972. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.010

- Murphy, J. (Ed.). (2005). Connecting teacher leadership and school improvement. USA: Corwin Press.

- Nasser, R. (2017). Qatar’s educational reform past and future: Challenges in teacher development. Open Review of Educational Research, 4(1), 1–19.

- Nguyen, D., Harris, A., & Ng, D. (2019). A review of the empirical research on teacher leadership (2003–2017): Evidence, patterns and implications. Journal of Educational Administration, 58(1), 60–80. doi:10.1108/JEA-02-2018-0023

- Ofsted. (2000). Improving City Schools: Strategies to Promote Educational Inclusion. London: Ofsted.

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533–544. doi:10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

- Pineda-Báez, C., Bauman, C., & Andrews, D. (2020). Empowering teacher leadership: A cross-country study. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 23(4), 388–414.

- Poekert, P. E. (2012). Teacher leadership and professional development: Examining links between two concepts central to school improvement. Professional Development in Education, 38(2), 169–188. doi:10.1080/19415257.2012.657824

- Pounder, P. (2022). Leadership and information dissemination: Challenges and opportunities in COVID-19. International Journal of Public Leadership, 18(2), 151–172. doi:10.1108/IJPL-05-2021-0030

- Sawalhi, R. (2019). Teacher leadership in government schools in Qatar : Opportunities and challenges . University of Warwick. Retrieved from http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/138040/1/WRAP_Theses_Sawalhi_2019.pdf

- Sawalhi, R., & Sellami, A. (2021). Factors influencing teacher leadership: Voices of public school teachers in Qatar. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 3, 1–18. doi:10.1080/13603124.2021.1913238

- Schott, C., Roekel, H. V., & Tummers, L. (2020). Teacher leadership : A systematic review, methodological quality assessment and conceptual framework. Educational Research Review, 31, 100352. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100352

- Sebastian, J., Huang, H., & Allensworth, E. (2017). Examining integrated leadership systems in high schools: Connecting principal and teacher leadership to organizational processes and student outcomes. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 28(3), 463–488. doi:10.1080/09243453.2017.1319392

- Shen, J., Wu, H., Reeves, P., Zheng, Y., Ryan, L., & Anderson, D. (2020). The association between teacher leadership and student achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 31, 100357. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100357

- Sinha, S., & Hanuscin, D. L. (2017). Development of teacher leadership identity: A multiple case study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 63, 356–371. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.01.004

- Smylie, M. A., & Brownlee-Conyers, J. (1992). Teacher leaders and their principals: Exploring the development of new working relationships. Educational Administration Quarterly, 28(2), 150–184. doi:10.1177/0013161X92028002002

- Stein, K. C., Macaluso, M., & Stanulis, R. N. (2016). The interplay between principal leadership and teacher leader efficacy. Journal of School Leadership, 26(6), 1002–1032. doi:10.1177/105268461602600605

- Szeto, E., & Cheng, A. Y. (2017). Developing early career teachers’ leadership through teacher learning. International Studies in Educational Administration (Commonwealth Council for Educational Administration & Management (CCEAM)), 45(3), 45–64.

- Tourish, D. (2020). Introduction to the special issue: Why the coronavirus crisis is also a crisis of leadership. Leadership, 16(3), 261–272. doi:10.1177/1742715020929242

- Trump, K. S. (2012). The post-crisis crisis: Managing parent and media communications. School Administrator, 69(4), 39–42.

- Vagle, M. D. (2018). Crafting phenomenological research. Routledge.

- Visone, J. D. (2018). Empowerment through a teacher leadership academy. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 11(2), 192–206. doi:10.1108/JRIT-08-2018-0019

- Visone, J. D. (2022). Empowering teacher leadership: Strategies and systems to realize your school’s potential. USA: Routledge.

- Walters, V. R. (2022). Elementary Principals’ Experiences Building Capacity for Teachers’ Critical-Thinking Pedagogy: A Qualitative Study (Doctoral dissertation, Capella University).

- Warren, L. L. (2021). The importance of teacher leadership skills in the classroom. Education Journal, 10(1), 8–15. doi:10.11648/j.edu.20211001.12

- Wenner, J. A., & Campbell, T. (2017). The theoretical and empirical basis of teacher leadership: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 87(1), 134–171. doi:10.3102/0034654316653478

- White, R. S. (2021). What’s in a first name?: America’s K-12 public school district superintendent gender gap. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 1–17. doi:10.1080/15700763.2021.1965169

- Williams, M., & Moser, T. (2019). The art of coding and thematic exploration in qualitative research. International Management Review, 15(1), 45–55.

- York-Barr, J., & Duke, K. (2004). What do we know about teacher leadership? Findings from two decades of scholarship. Review of Educational Research, 74(3), 255–316. doi:10.3102/00346543074003255

- Youngs, H., & Evans, L. (2021). Distributed leadership. In S. Courtney, H. Gunter, R. Niesche, & T. Trujilla (Eds.), Understanding educational leadership: Critical perspectives and approaches (pp. 203–219). Bloomsbury Publishing PLC.