Abstract

Background

A public health approach to gambling has been accompanied by a wide understanding of gambling harms. This has led to the creation of conceptual frameworks to understand and itemize different gambling-related harms, dimensions of harms, and subjects of harms. The current paper presents a comparative review and synthesis of existing harm frameworks.

Method

Following the PRISMA guidelines, we conducted a systematic literature review on existing harm frameworks in five scientific databases across the years 2000–2021. We included studies that aimed at creating a conceptual framework or synthesis of different level gambling harms at a population level. The final sample consists of seven papers that present four different models.

Results

Gambling-related harms span health, psychological, relationship, financial, cultural, work, and crime-related issues. Harms accrue to individuals (heavy gamblers, non-problem gamblers and nongamblers), but also to families, communities, and societies. Harms form a spectrum in terms of severity and temporality. Risk factors or determinants of gambling are often similar to the harmful consequences of gambling.

Conclusions

The results are discussed in terms of gaps in current understanding of gambling harms, including increased communication between models, increased focus on severity levels and issues of causality, and a better incorporation of harms that stem from gambling provision rather than harmful gambling consumption. We conclude that framing harms as consequences of individual behavior remains predominant, and a shift of focus to the social and commercial determinants of gambling harms is needed. This also includes the development of societal level harm screening.

Keywords:

Introduction

Gambling is increasingly understood as a public health issue (e.g. Abbott Citation2020; Wardle et al. Citation2021). The public health approach to gambling is in line with a more general new public health movement that has been applied to individual and population health since the 1980s (Ashton and Seymour Citation1988). The public health framing is accompanied by an aim to reduce and prevent harms in the population. Based on the current understanding, this includes both behavioral and structural approaches to explaining health differences (Westbrook and Harvey Citation2022). Applying the public health approach to gambling requires clarity on what kind of harms are related to it, to whom they are accruing, and consequently, how harm minimization or harm prevention strategies should be targeted (cf. Gainsbury et al. Citation2014; McMahon et al. Citation2019; Sulkunen et al. Citation2019). The current paper focuses on mapping and comparing existing models on gambling harms. The aim is to draw a synthesis of the different types of harms related to gambling, the different dimensions that these harms take, and differing approaches taken to defining and understanding harms.

Early research investigating gambling harms adopted a definition of harm that was largely equated with problem gambling prevalence. Since the 1990s, the public health impacts and full risk spectrum of gambling have gained increasing importance (Korn and Shaffer Citation1999; Price et al. Citation2021). In a historical mapping study of public health research on gambling, Price et al. (Citation2021) noted that in the early 2000s, increased focus has been paid to gambling environments, gambling types, and gambler groups from a harm perspective. Since 2010, public health research on gambling has further expanded with focus also directed at conceptualizations, measurement, and empirical exploration. Harms that do not directly derive from excessive or addictive consumption, but also of non-problematic gambling or of gambling provision more generally have also been recently highlighted (Browne et al. Citation2017, Citation2021; Baxter et al. Citation2019; Sulkunen et al. Citation2019). However, differences in how harms are conceptualized continue to exist across disciplines but also between cultural contexts. For instance, Baxter et al. (Citation2019) found that Australian gambling research is more strongly characterized by discussion on exposure and gambling environments, whereas research in New Zealand focuses more strongly on gambling resources (harm reduction, treatment) as factors of harm or harm prevention. In Canada, psychological and biological factors have been emphasized.

A wider understanding of gambling-related harms has led to the need and creation of frameworks to classify and itemize different gambling harms. Endeavors for comprehensive frameworks have been taken in several research groups globally. These frameworks, drawing mainly from existing research literature, have focused with varying foci on types of harms, severity levels, subjects of these harms, as well as risk (or conversely protective) factors that impact the emergence of harms. This work has provided a strong conceptual basis on understanding the breadth and scope of what constitutes gambling-related harm. Similar approaches to creating conceptual frameworks of harm dimensions have also been taken in alcohol studies (Room et al. Citation2010) and drug research (Newcombe Citation1992)

To our knowledge, only one previous study (Price et al. Citation2021) has addressed the similarities and differences between some of the existing gambling harm frameworks (Langham et al. Citation2015; Abbott et al. Citation2018; Wardle et al. Citation2018). The study showed that these three frameworks share commonalities in that each adopt the public health framing, consider multiple levels and the wide spectrum of harms, as well as varying contributing factors. Each framework has also been influential within research, treatment, and policy. However, there has been no review available of existing gambling harm frameworks that would systematically compare their scope and content. The current paper aims to do this in addition to creating a synthesis of their main harm dimensions and discussing possible gaps.

Materials and methods

We conducted a systematic literature search to map existing frameworks of gambling harms. We used the scoping review methodology as the aim was to identify the key conceptualizations of gambling harms in previous syntheses, but also to identify possible gaps. We followed the methodological framework for conducting a scoping study as put forward by Arksey and O'Malley (Citation2005). We also incorporated the meta-synthesis methodology (Sandelowski et al. Citation1997) to construct a synthesis of the main dimensions of gambling harm. The research question informing the analysis process was how gambling-related harm is conceptualized in previous conceptual frameworks.

To identify relevant studies on the frameworks of gambling harms, we conducted a literature search in five scientific databases: Scopus, Ebscohost, ProQuest, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The search focused on scientifically developed and comprehensive harm frameworks that would take into consideration not only individual-level harms but also social and societal harms. To this end, the keywords used to conduct searches were gambling AND harm AND framework/model/synthesis AND societ*. The text types included were academic articles, proceedings, books, dissertations, and reports. We excluded newspaper reporting. Articles in English, French, and German were included. The search covered the years 2000–2021. The year 2000 was used as a cutoff point because public health literature has begun to shift focus from behavioral to social and structural determinants of health around the turn of the millennium (cf. Westbrook and Harvey Citation2022). We acknowledge that some earlier work on itemizing gambling harms also exists (notably Korn and Shaffer Citation1999), but these were not included in the review to highlight the more recent work.

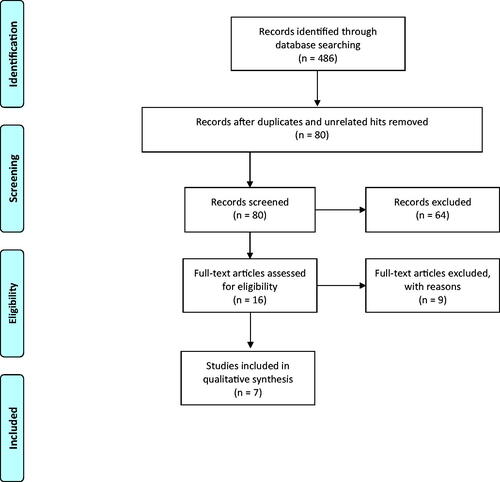

We then moved on to study selection. is adapted from the PRISMA guidelines of the inclusion process (Moher et al. Citation2009; Page et al. Citation2021). Our search yielded a total of 482 records. We further scanned the reference lists of included studies for more possible references. This put the total number of references included at 486. We first removed the duplicates (N = 93) and unrelated hits (N = 313) that mainly consisted of studies unrelated to gambling or gambling harms. We then screened the remaining 80 records for their relevance based on their abstracts, resulting in the exclusion of a further 64 papers.

The inclusion criteria at the abstract screening stage were: (1) the main aim of the work is to create or develop a framework of different level gambling harms; (2) the work is conceptual and aims at a synthesis; (3) the work concerns the full population and not only a population group such as youth; (4) the work is based on an empirical method and is not an opinion or discussion piece. These criteria excluded cost-benefit studies that focus on monetary costs of gambling, risk models for individual gambling products, individual-level bio-psychological models that do not address the role of societal harms (such as the Reno model, cf. Blaszczynski et al. Citation2004), or burden of harm studies that aim at quantifying or creating measurement methods for specific harms (e.g. Delfabbro and King Citation2019; Browne et al. Citation2020a).

The remaining sample consisted of 16 articles that were carefully read. At this stage, we excluded a further nine papers based on four exclusion criteria: (1) papers that did not develop their own framework but adopted an existing one (N = 2); (2) non-empirical discussion papers (N = 2); (3) the main aim was not to produce a framework of gambling harms (N = 4); after a closer reading the work was found to concern only a sub-group of population (N = 1). The final sample consisted of seven papers of which four concerned the development of the same framework. The number of different frameworks analyzed was therefore four. The included studies are described in . Due to the similarity of their names, we refer to the frameworks by their authors in the analysis.

Table 1. Frameworks on gambling harms included in the review.

Due to the small number of results, the analysis is theory driven. The types of harms and harm dimensions addressed in the included models were charted using five analytical categories: (1) definitions of harms; (2) subjects of harms; (3) dimensions of harms; (4) types of harms associated with gambling; (5) types of risk factors for harmful gambling. For the analysis, the first three analytical categories were combined in the interest of creating a synthesis of the understanding of harms. Three of the four included models focused on the types of harms caused by gambling (Langham et al. Citation2015; Wardle et al. Citation2018; Latvala et al. Citation2019). One of the frameworks focused on the types of risk factors for harmful gambling (Abbott et al. Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2018; Hilbrecht et al. Citation2020). In the subsequent analysis we refer to the most recent report (Abbott et al. Citation2018). Ethics approval was not required for the study as it based on existent and publicly available frameworks.

Results

Definitions and dimensions of harms

Three of the four frameworks included a functional definition of harm (Langham et al. Citation2015; Abbott et al. Citation2018; Wardle et al. Citation2018). Each of these highlighted the multidimensional relationship between gambling and its adverse consequences. The same three models also acknowledged that harms can be directly caused by gambling, but gambling can also aggravate existing harms and inequalities in societies.

The main definitions and dimensions of harms in the four models are summarized in .

Table 2. Definitions and dimensions of harms in existing frameworks.

The subjects of harms are understood in a wide sense in each framework. In addition to individual-level harms, harm to others, communities and societies are highlighted. However, the causes of gambling-related harms are mainly seen to stem from individual engagement in gambling. This is understandable as the frameworks have been drafted based on existing literature where the role of individual problem gambling remains a strong factor of harm at all levels. Only the model by Latvala et al. (Citation2019) explicitly acknowledges that some harms may also stem from so-called general impacts in addition to the impacts of problem gambling. These include for example harms stemming from the gambling industry, such as residential area degeneration or impact on other industries. However, Langham et al. (Citation2015) and Wardle et al. (Citation2018) conceptualize the cause of gambling harms as ‘engagement with gambling’ which may also be interpreted in a wider sense.

Two frameworks also distinguish between different severity-levels of harms (Langham et al. Citation2015; Abbott et al. Citation2018). Harms are understood to span from inconsequential and general harms to significant, crisis-level harms. Each one of the compared frameworks also includes a temporal understanding of harms. Abbott et al. (Citation2018) and Latvala et al. (Citation2019) note that harm can be episodic or long-term. Wardle et al. (Citation2018) and Langham et al., (Citation2015) further note that harm can also have enduring life-course impacts. Langham et al. (Citation2015) further note that harms can span beyond the individual experience and be intergenerational. The temporal aspects of harms in the Langham et al. (Citation2015) model have also been developed in terms of communities and societies.

Types of harms associated with gambling

Three of the frameworks focused on harms as mainly the consequences of gambling (Langham et al. Citation2015; Latvala et al. Citation2019; Wardle et al. Citation2018). Each framework includes a hierarchical organization of harm categories and individual harm elements that have been classified under these. The number of top-level categories varied between seven (Langham et al. Citation2015) and three (Latvala et al. Citation2019; Wardle et al., Citation2019). Each of the tree models included financial harms and health harms as top-level categories. Relationship harms as well as work (and study) related harms were mentioned in two of the frameworks. Emotional and psychological harms, cultural harms, and crime were separate categories only in the model by Langham et al. (Citation2015).

Despite differences in organization, the frameworks included very similar harm elements. Work-related harms were included under financial harms in the model by Wardle et al. (Citation2019), whereas both the models by Wardle et al., (Citation2018) and Latvala et al. (Citation2019) categorized emotional and psychological harms under health harms. Crime-related items were divided between work (and study) related harms and health harms in the Latvala et al. (Citation2019) framework but under financial harms in the Wardle et al. (Citation2018) framework. This indicates a general difficulty in not only creating categories of harms but also in placing identified harm items under these categories. Part of the differences in categorization may also stem from contextual differences. Notably, the Latvala et al. (Citation2019) framework, developed within the Nordic context, sees financial harms from the perspective of public economy or individual finances whereas financial issues impacting industries, corporations, and businesses are categorized separately under work and study related harms. This categorization differs from the Anglo-American understanding of financial harms in the models by Wardle et al. (Citation2018) and Langham et al. (Citation2015), which understand business-related financial harms such as productivity losses or business closures as primarily financial harms.

presents a synthesis of the different harm categories and harm elements in the three models. The categorization is adopted from Langham et al. (Citation2015) as this was the most complete. The harms have been divided between individual and family level harms and community and society level harms.

Table 3. Categories of harms associated with gambling, adapted from Langham et al. (Citation2015).

Harms or risk factors

Only one of the identified frameworks (Abbott et al. Citation2018) focused primarily on risk factors or determinants of harms. The model discusses gambling-specific factors (e.g. gambling environment, exposure, types, and resources) as well as general factors (such as cultural availability, social, psychological, and biological).

Whilst the model has mainly set out to examine antecedents to gambling and/or the development of gambling harms, the determinants of harms identified coincide to an important degree with the identified harm dimensions described in . Notably, relationship-related harms coincide partly with social factors, emotional and psychological harms with psychological factors, while cultural harms also coincide with many cultural but also gambling exposure related factors. Crime-related harms also relate to many social factors but also partly to gambling environments. Financial as well as work and study related harms also coincide with many social factors suggested by Abbott et al. (Citation2018). Furthermore, and similarly to the harms identified, these determinants of harms also occur on the individual, familial, community, and societal levels (cf. Wardle et al. Citation2018).

The interlinkages between the determinants of harm and the actual harm elements would suggest that instead of treating these two separately, they should rather be viewed as complementary. The causal relationships between harms and gambling are often difficult to pinpoint, and sometimes the harms eventually exacerbated by gambling also precede gambling behavior as risk factors or determinants of harm.

Discussion

The current study has mapped existing gambling harm frameworks, compared their scope and content, and attempted to create a synthesis of their main harm dimensions. Based on the collective expertise presented in the frameworks, we define gambling-related harms as follows: Gambling-related harms span a range of health, psychological, relationship, financial, cultural, work, and crime related issues. Some harms precede gambling but are aggravated by it; others arise because of gambling. Harms accrue to individuals (both heavy gamblers but also nonproblem and inactive gamblers), but also to families, communities, and societies. The experience of harm can range from relatively mild to crisis level and continue long after gambling behavior stops or span generations.

Based on this review, we have also identified four issues or gaps regarding the existing efforts to create frameworks of gambling-related harms. These are not to discredit the existing and extensive work conducted to draft these models but rather thought on how to move forward to develop an even more comprehensive understanding of the multidimensionality of gambling-related harms and how to move from conceptualization to the measurement of harms.

First, there appears to be a lack of communication between the models, resulting in differing approaches to categorizing harms and partly overlapping literature reviews, but also contextually differing definition of different harm items. Perhaps due to this lack of communication, none of the models seems to have taken a leading position in the field of gambling studies, although the models of Langham et al. (Citation2015), Wardle et al. (Citation2018) and Abbott et al. (Citation2018) have been applied in empirical studies (e.g. Browne et al. Citation2017; Wardle et al. Citation2019; Raybould et al. Citation2021). Differences in categorizations are not surprising as each category stems from their own cultural, as well as disciplinary or theoretical frames. These leave their marks on the final harm framework developed. There also needs to be a certain degree of flexibility in the models to make them adaptable to differing contexts. However, despite differing starting points the frameworks have also yielded very similar harm elements. This suggests that overall, harms are quite similarly understood despite different categorizations and outlooks.

Second, none of the models includes a hierarchical structure of the types of harms and their severity for individuals, families, communities, or societies. All identified harms (or determinants of harm) are treated as somewhat equal. It has been suggested that the impact on health and wellbeing is the main category of harm (Browne et al. Citation2021) and the prevention paradox does not apply to all harms similarly (Browne et al. Citation2020b). Similarly, financial harms can be seen to precede or even cause many of the other harms, including criminal acts or emotional suffering. For these reasons, financial harms have also been argued to be the most prevalent form of harms (Browne and Rockloff Citation2018; Muggleton et al. Citation2021). In future efforts to categorize and understand gambling harms, a measure of severity and prevalence would be needed.

Third, the observation that similar items are characterized as both determinants of harmful gambling (Abbott et al. Citation2018) and as gambling harms (Langham et al. Citation2015; Wardle et al. Citation2018; Latvala et al. Citation2019) highlight the problem of causality related to gambling harms. Browne and Rockloff (Citation2018) have previously noted that in literature on gambling harms, problem gambling has been seen as both a risk factor and (at least a partly) a consequence. This differentiates gambling from other public health issues in which the risk factors are clearly different from the diagnosable harms (e.g. smoking and lung cancer). This tautology, alongside complicated comorbidities (also Lorains et al. Citation2011; Sulkunen et al. Citation2019) would suggest that it might be better to treat harms as continuous impacts on the quality of life rather than as separate issues. The issue of causality or temporality may be more of a conceptual problem. From the perspective of measuring harms, it may be more important that certain factors of harm are connected to gambling regardless of the direction of causality.

Fourth, and most importantly, despite an encompassing definition of harms that concerns not only individuals and their families, but also communities and societies, most harms within the frameworks stem from individual (problem) gambling. Yet, as Browne et al. (Citation2017) have shown, at a population level aggregate harms of nonproblem gamblers exceed those accruing to problem gamblers by 4:1. Gambling, and not only problem gambling, can therefore cause harms at even a low or zero level of active participation (also Abbott et al. Citation2013; Langham et al. Citation2015). Furthermore, the existence of gambling within societies can cause harms irrespective of individual participation, including corruption, economic substitution, match fixing, environmental damage related to tourism, or animal suffering (e.g. Sulkunen et al. Citation2019; Marionneau and Nikkinen Citation2020; Marionneau et al. Citation2021). Despite this evidence, the role of societal harms remains relatively marginal and largely overshadowed by individual-level harms. The exception to this are the commercial determinants of harm related to gambling environments, exposure, and types included in the Abbott et al. (Citation2018) model.

If gambling is to be understood as a public health issue, the minimization of harms should target societal levels alongside individual and community levels (cf. Wardle et al., Citation2018). A shift of perspective may be needed where even harms experienced by individuals would be considered primarily social harms with societal consequences. Individuals are largely products of the societal circumstances. It could be argued that gambling causes the harm to the community and societal level, which results in harm to the individual.

The main aims of categorizing gambling-related harms are to minimize and to measure them. From a public health perspective, the minimization of harms should also target risk characteristics at societal as well as individual and community levels (Wardle et al. Citation2018). Yet, the measurement of harms currently focuses mainly on problem gambling prevalence or cost-benefit studies and socio-economic impact analyses. The former run the risk of having a tautological definition of harm and confusing problem gambling with gambling harm. Screens are also mainly administered to those who gamble or are closely connected to gamblers, not the general population. The latter are difficult to implement and run the risk of downplaying non-quantifiable or non-monetary harms, and particularly societal harms. A recent review of gambling-related harm measurement (Browne et al. Citation2021) found that while a substantial proportion of exiting work employs problem gambling indexes (CPGI, PGSI; SOGS) to measure harms, more recent approaches have employed wider definitions of harms. However, there remains an inconsistency across studies regarding instruments employed. A bibliometric study of gambling harms (Baxter et al. Citation2019) similarly found that psychological harms were overrepresented in literature, but harms related to resources have also become increasingly important.

Although models are available for population-level screen of gambling harms from a public health perspective (Browne, Greer et al. Citation2017; Browne, Rawat et al. Citation2017), there is currently no harms screen that would be administered to communities or societies rather than individuals. Such a screen would be necessary, as the benefits of gambling are usually calculated in terms of financial inputs community or jurisdiction. A societal level screen could focus for instance on the damaged relations and impaired societal systems rather than individuals that are harmed by gambling. Such a shift in perspective would allow focusing on the societal factors and processes that are function as determinants of harm but are also harmed by gambling. The development of a societal-level screen would be an important step in further studies. In addition, further research would be needed on how the harm frameworks could be operationalized to minimize the negative public health consequences of gambling and harmful gambling.

The current study has been limited to studying established and comprehensive frameworks of gambling harms. The review process found only four such frameworks which limits the possibilities of drawing conclusions. The frameworks have also had different foci which has complicated comparison. In addition to further developing the operationalization and measurement of harm frameworks, further research could also expand the current study by comparing harm frameworks to cost-benefit models, socio-economic impact models, or burden of health approaches. More research is also needed on the societal harms of gambling, and particularly of harms that do not stem from problematic gambling behavior but rather from the provision of gambling.

Concluding remarks

A public health approach to gambling requires a wide understanding of harms. This includes not only individual behavior and first-hand experience of problem gambling, but a wide range of harmful factors that also accrue to families, communities, and societies. The current study has created a synthesis of the main harm elements that have been identified in existing frameworks. We have found that while existing conceptualizations include a wide definition of harms, most harm items are still seen to stem from individual engagement with gambling. Further incorporation of social and societal harms is still needed to conceptualize and operationalize gambling as a public health issue. This includes the development of societal-level harm measurement and harm minimization. The current comparative review and synthesis provides a platform for further work to identify structural factors that contribute to and experience harms from gambling, and to build societal-level harms screening that would shift focus from individual responsibility and blame to the social and commercial determinants that contribute to gambling harms.

Disclosure of interests

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbott MW. 2020. Gambling and gambling-related harm: recent World Health Organization initiatives. Public Health. 184:56–59.

- Abbott MW, Binde P, Clark L, Hodgins DC, Johnson MR, Manitowabi D, Quilty L, Spånberg J, Volberg R, Walker D, et al. 2018. Conceptual framework of harmful gambling: an international collaboration. 3rd ed. Guelph (Canada): Gambling Research Exchange Ontario (GREO).

- Abbott MW, Binde P, Clark L, Hodgins DC, Korn D, Pereira A, Quilty L, Thomas A, Volberg R, Walker D, et al. 2015. Conceptual framework of harmful gambling: an international collaboration revised September 2015. Guelph (Canada): Gambling Research Exchange Ontario (GREO).

- Abbott MW, Binde P, Hodgins D, Korn D, Pereira A, Volberg R, Williams R. 2013. Conceptual framework of harmful gambling: an international collaboration. Guelph (Canada): Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre (OPGRC).

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. 2005. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method. 8(1):19–32.

- Ashton J, Seymour H. 1988. The new public health. Vol. 1. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Baxter DG, Hilbrecht M, Wheaton CTJ. 2019. A mapping review of research on gambling harm in three regulatory environments. Harm Reduct J. 16(1):12–19.

- Blaszczynski A, Ladouceur R, Shaffer HJ. 2004. A science-based framework for responsible gambling: the Reno model. J Gambl Stud. 20(3):301–317.

- Browne M, Bellringer M, Greer N, Kolandai-Matchett K, Rawat V, Langham E, Rockloff M, Palmer Du Preez K, Abbott M. 2017. Measuring the burden of gambling harm in New Zealand. Auckland (New Zealand): Central Queensland University and Auckland University of Technology.

- Browne M, Greer N, Rawat V, Rockloff M. 2017. A population-level metric for gambling-related harm. Int Gambl Stud. 17(2):163–175.

- Browne M, Rawat V, Greer N, Langham E, Rockloff M, Hanley C. 2017. What is the harm? Applying a public health methodology to measure the impact of gambling problems and harm on quality of life. J Gambl Issues. 36:28–50.

- Browne M, Rockloff M. 2018. Prevalence of gambling-related harm provides evidence for the prevention paradox. J Behav Addict. 7(2):410–422.

- Browne M, Rawat V, Newall P, Begg S, Rockloff M, Hing N. 2020a. A framework for indirect elicitation of the public health impact of gambling problems. BMC Public Health. 20(1):1–14.

- Browne M, Volberg R, Rockloff M, Salonen A. 2020b. The prevention paradox applies to some but not all gambling harms: Results from a Finnish population-representative survey. J Behav Addict. 9(2):371–382.

- Browne M, Rawat V, Tulloch C, Murray-Boyle C, Rockloff M. 2021. The evolution of gambling-related harm measurement: lessons from the last decade. IJERPH. 18(9):4395.

- Browne M, Volberg R, Rockloff M, Salonen AH. 2020a. The prevention paradox applies to some but not all gambling harms: results from a Finnish population-representative survey. J Behav Addict. 9(2):371–382.

- Delfabbro P, King DL. 2019. Challenges in the conceptualisation and measurement of gambling-related harm. J Gambl Stud. 35(3):743–755.

- Gainsbury SM, Blankers M, Wilkinson C, Schelleman-Offermans K, Cousijn J. 2014. Recommendations for international gambling harm-minimisation guidelines: comparison with effective public health policy. J Gambl Stud. 30(4):771–788.

- Hilbrecht M, Baxter D, Abbott M, Binde P, Clark L, Hodgins DC, Manitowabi D, Quilty L, SpÅngberg J, Volberg R, et al. 2020. The conceptual framework of harmful gambling: a revised framework for understanding gambling harm. J Behav Addict. 9(2):190–205.

- Korn D, Shaffer H. 1999. Gambling and the health of the public: adopting a public health perspective. J Gambl Stud. 15(4):289–365.

- Langham E, Thorne H, Browne M, Donaldson P, Rose J, Rockloff M. 2015. Understanding gambling related harm: A proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms. BMC Public Health. 16(1):1–23.

- Latvala T, Lintonen T, Konu A. 2019. Public health effects of gambling–debate on a conceptual model. BMC Public Health. 19(1):1–16.

- Lorains FK, Cowlishaw S, Thomas SA. 2011. Prevalence of comorbid disorders in problem and pathological gambling: systematic review and meta‐analysis of population surveys. Addiction. 106(3):490–498.

- Marionneau V, Egerer M, Nikkinen J. 2021. How do state gambling monopolies affect levels of gambling harm? Curr Addict Rep. 8(2):225–234.

- Marionneau V, Nikkinen J. 2020. Does gambling harm or benefit other industries? A systematic review. J Gambl Iss. 44:4–44.

- McMahon N, Thomson K, Kaner E, Bambra C. 2019. Effects of prevention and harm reduction interventions on gambling behaviours and gambling related harm: an umbrella review. Addict Behav. 90:380–388.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, the PRISMA Group. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 6(7):e1000097.

- Muggleton N, Parpart P, Newall P, Leake D, Gathergood J, Stewart N. 2021. The association between gambling and financial, social and health outcomes in big financial data. Nat Hum Behav. 5(3):319–326.

- Newcombe R. 1992. The reduction of drug-related harm: a conceptual framework for theory, practice, and research. O’Hare PA, Newcombe R, Matthews A, Buning EC, Drucker E, editors. The reduction of drug-related harm. London: Routledge.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 88:105906.

- Price A, Hilbrecht M, Billi R. 2021. Charting a path towards a public health approach for gambling harm prevention. Z Gesundh Wiss. 29(1):37–53.

- Raybould JN, Larkin M, Tunney RJ. 2021. Is there a health inequality in gambling related harms? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 21(1):1–17.

- Room R, Ferris J, Laslett AM, Livingston M, Mugavin J, Wilkinson C. 2010. The drinker’s effect on the social environment: a conceptual framework for studying alcohol’s harm to others. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 7(4):1855–1871.

- Sandelowski M, Docherty S, Emden C. 1997. Qualitative metasynthesis: issues and techniques. Res Nurs Health. 20(4):365–371.

- Sulkunen P, Babor TF, Cisneros Örnberg J, Egerer M, Hellman M, Livingstone C, Marionneau V, Nikkinen J, Orford J, Rossow I. 2019. Setting limits: Gambling, science, and public policy. Oxford: University Press.

- Wardle H, Reith G, Best D, McDaid D, Platt S. 2018. Measuring gambling-related harms: a framework for action. Gambling Commission: Birmingham, UK.

- Wardle H, Reith G, Langham E, Rogers RD. 2019. Gambling and public health: we need policy action to prevent harm. BMJ. 365:l1807.

- Wardle H, Degenhardt L, Ceschia A, Saxena S. 2021. The Lancet public health commission on gambling. Lancet Public Health. 6(1):e2–e3.

- Westbrook M, Harvey M. 2022. Framing health, behavior, and society: a critical content analysis of public health social and behavioral science textbooks. Critical Public Health, p. 1–12. [AQ]