ABSTRACT

Objectives

One of the treatment modalities that can be used for hyperleukocytosis is leukapheresis. However, the result of studies showing the benefit of early mortality through the use of leukapheresis versus no leukapheresis is still inconclusive. Hence, we aimed to conduct a systematic review with meta-analysis to determine the effect of leukapheresis on early mortality in AML patients with hyperleukocytosis.

Methods

We conducted a literature search on five databases (PubMed, EBSCOhost, Scopus, Clinicalkey, and JSTOR) up to October 2021 for studies comparing early mortality outcomes between hyperleukocytosis AML patients treated with leukapheresis versus no leukapheresis. Summary odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using random-effects models. Heterogeneity tests were presented in I2 value and publication bias was analyzed using a funnel plot.

Results

Eleven retrospective cohort studies were eligible based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Pooled analysis showed that there was no significant difference in early mortality between patients receiving leukapheresis and not receiving leukapheresis in studies using hyperleukocytosis cutoff of 95,000/mm3 or 100,000/mm3 (OR: 1.17; 95% CI: 0.74-1.86; p: 0.50; I2: 0%). Similarly, studies using hyperleukocytosis cutoff of 50,000/mm3 also showed no benefits of early mortality (OR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.43-1.05; p: 0.08; I2: 0%). Most of the studies used had a moderate risk of bias due to being observational studies. Funnel plot showed an indication of publication bias on studies using hyperleukocytosis cutoff of ≥50,000/mm3.

Conclusion

The use of leukapheresis does not provide early mortality benefit in adult AML patients with hyperleukocytosis.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a malignant hematological problem defined by malignant expansion of myeloid progenitor cells with differentiation arrest [Citation1–3]. In the US, AML has the second highest incidence among four subtypes of leukemia after chronic lymphoid leukemia (CLL) [Citation4]. Epidemiological study by Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program in 2016 reported that the incidence of AML after adjustment by age was 4.3 per 100,000 person-years [Citation5]. One of the issues in AML management is high early mortality, especially when hyperleukocytosis is present [Citation6,Citation7].

Hyperleukocytosis is defined as the white blood cell (WBC) count of >100,000/µL [Citation8,Citation9]. It is reported that hyperleukocytosis was found up to around 20% of adult patients with AML and thus, is one of the most common complication of AML [Citation6,Citation10–12]. The high mortality rate of up to 29% is caused due to blockage of blood vessels from leukemic blast cells with subsequent leukostasis and tissue ischemia [Citation8,Citation13]. The main pathophysiology of leukostasis is mainly due to leukemic blast cells lacking deformable property and having the tendency to adhere to endothelium through expression of surface adhesion molecules [Citation14–18]. Hyperleukocytosis, therefore, is a medical emergency that must be treated early to prevent mortality.

One of the available methods to reduce leukocyte count is leukapheresis, however, the role of leukapheresis for AML with hyperleukocytosis in reducing early mortality is still controversial and uncertain [Citation17,Citation19,Citation20]. From a pathophysiological viewpoint, AML is a disease of hematopoietic stem cells in bone marrow but leukapheresis only remove peripheral blast cells without affecting blast-generating hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow or tissue-infiltrating blast cells [Citation10]. Furthermore, there is an incapability of leukapheresis to remove cellular plugs or blockage that are already formed in vascular vessels by the blast cells and the rapid removal of blast cells may cause a reactive increase in the activity of blast production in bone marrow [Citation8,Citation10,Citation16,Citation17,Citation21]. Nevertheless, some studies have shown that leukapheresis has a beneficial effect in reducing early mortality outcome [Citation7,Citation8,Citation17,Citation22]. Another interesting fact is that many clinicians worldwide have a preference to use leukapheresis despite lack of solid evidence for leukapheresis [Citation19].

There are currently many cohorts that compare early mortality between AML patients receiving leukapheresis and not receiving leukapheresis, but with relatively a small adequate sample size and conflicting results [Citation22–28]. A recent well-written systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted by Bewersdorf et al.; however, the review included studies with pediatric patients which may impact the mortality outcome and the article had heterogeneity in the pooled analysis [Citation29]. Furthermore, a new study is now available to be incorporated for pooled analysis [Citation30]. Hence, we aim to produce a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the effect of leukapheresis on early mortality in adult AML patients with hyperleukocytosis.

Method

Study registration

The protocol was registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) with an ID number of CRD42021224945.

Ethical approval

This study was a systematic review with meta-analysis using studies and the grey literatures published on medical databases. Hence, no ethical approval was necessary for this study.

Data sources and searches

Electronic databases were searched from January 2021 to October 2021 on the following: (1) PubMed, (2) EBSCOhost, (3) Scopus, (4) JSTOR, (5) Clinicalkey, and (6) grey literatures. The combination of keywords ‘Leukapheresis’, ‘acute myeloid leukemia’, ‘hyperleukocytosis’, and ‘mortality’ together with their synonyms were entered to search relevant articles. Search strategy included Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and Boolean operators. Manual searching was also conducted.

Study selection

Inclusion criteria used in this systematic review and meta-analysis were as follows: (1) observational studies or clinical trials that involved adult AML patients with hyperleukocytosis, (2) studies that have an intervention of leukapheresis and comparator of no leukapheresis, and (3) studies with outcome of early mortality. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) not published in English language, (2) single-arm studies, (3) studies with a sample size of ≤5 patients, (4) AML patients without hyperleukocytosis, (5) include patients aged <18 years, (6) review article, and (7) basic research article.

Two researchers independently conducted literature searches and identified the literature. All studies selected were pooled and examined to determine its eligibility according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria or met the exclusion criteria would not be included research analysis. Any disagreement or discrepancy by the authors were solved through discussion by all authors.

Data extraction

Data extracted from the literature include name of first author, country of the study, year of publication, study design, intervention/comparator of the study, sample size, median age, median hemoglobin, median leukocyte, median blast, median platelet, hyperleukocytosis cutoff used by the studies, percentage of patients having leukostasis, and outcomes of the studies. Data extraction was conducted by two authors (IR and KW). Any differences in opinions were resolved by consensus.

Main outcome of interest was early mortality comparison of AML patients with hyperleukocytosis receiving leukapheresis versus those not receiving leukapheresis. Early mortality was defined as a 7-day mortality up to a 30-day mortality. When there are studies with multiple early mortality outcomes, we used the longest early mortality outcome for pooled analysis.

Risk of bias assessment

The assessment of the validity of the literature was carried out using Cochrane’s ‘Tool to Assess Risk of Bias in Cohort Studies’. Risk of bias assessment was conducted by two authors and any disagreement was solved through consensus from all authors. Bias of the studies were classified into low bias, unclear bias, and high bias.

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis will be conducted according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration. The final effect result of this study is odds ratios (OR) which is reported with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical analysis was performed using the Revman application version 5.4 (The Nordic Cochrane Center, Copenhagen). The heterogeneity of the literatures used for pooled analysis was evaluated using the Cochrane standard χ² test and statistical I². A χ² value <0.05 was interpreted as statistically significant. Random-effects model was used for the pooled analysis. Bias in publications was analyzed with the funnel plot.

Result

Study selection

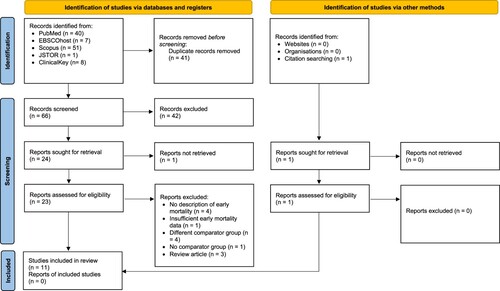

Initial search from medical databases yielded 107 articles (). Total articles without duplicates were 66 articles which was then screened by titles and abstracts, resulting in a total of 25 articles to be screened from the full text. Of these, the full text from one article was not able to be retrieved. Subsequently, the other 24 articles were assessed for eligibility through full-text reading. From full-text reading, 4 articles had no description of early mortality [Citation31–34], 1 article had insufficient early mortality data [Citation7], 4 articles had different comparator group with our PICO [Citation35–38], 1 article had no comparator group [Citation39], and 3 articles were either review articles or book chapter [Citation40–42]. Thus, 11 articles from identification through databases were included in this review ().

Characteristics of the included studies

Summary of the selected studies can be seen in . All studies used for review and pooled analysis were of retrospective cohort design since no prospective cohort and clinical trials were found during the systematic literature search. All 11 eligible studies had early mortality as an outcome but there was variation in the definition of early mortality with range from 14 days to 30 days. The year of publication for the studies ranges from 2007 to 2021. Seven studies reported the percentages of patients with leukostasis symptoms [Citation13,Citation22,Citation23,Citation26,Citation28,Citation30,Citation43].

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

Early mortality

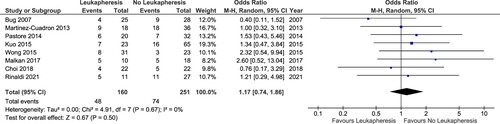

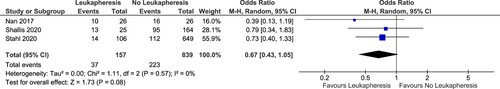

Eleven studies were selected for pooled analysis with an outcome of early mortality. Total of patients available for analysis was 1407 patients consisting of 1090 patients not receiving leukapheresis and 317 patients receiving leukapheresis. We divided the analysis based on the definition of hyperleukocytosis used by the studies. Eight studies had definition of hyperleukocytosis as ≥ 95,000/mm3 or 100,000/mm3. Meanwhile, the studies by Nan et al., Shallis et al., and Stahl et al. used a cutoff of 50,000 WBC as the definition of hyperleukocytosis [Citation13,Citation22,Citation28].

Result of the pooled analysis showed that the pooled OR for early mortality of studies using hyperleukocytosis cutoff of 95,000/mm3 or 100,000/mm3 was 1.17 (95% CI: 0.74–1.86; p: 0.50; I2: 0%) (). Studies using hyperleukocytosis cutoff of 50,000/mm3 also showed no benefit of leukapheresis in reducing early mortality (OR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.43–1.05; p value: 0.08; I2: 0%) (). Both pooled analyses had no heterogeneity.

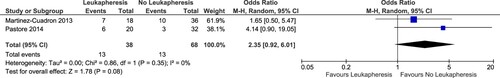

Seven-day mortality

Only two cohorts were available that measured 7-day mortality as outcomes [Citation26,Citation27]. Similarly, there was also no statistically significant difference on the pooled analysis for 7-day mortality (OR: 2.35; 95% CI: 0.92–6.01; p value: 0.08; I2: 0%) ().

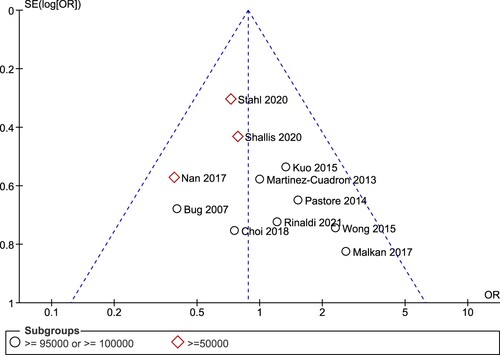

Funnel plot

For the overall 11 studies, no qualitative evidence of publication bias was observed in the funnel plot for the association between leukapheresis and early mortality when studies using different cutoffs of hyperleukocytosis were combined (). However, if analyzed separately, the studies using hyperleukocytosis cutoff of ≥50,000/mm3 have a tendency to be located on the left side of the funnel plot only which may indicate a publication bias.

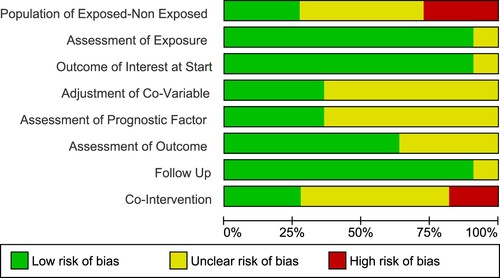

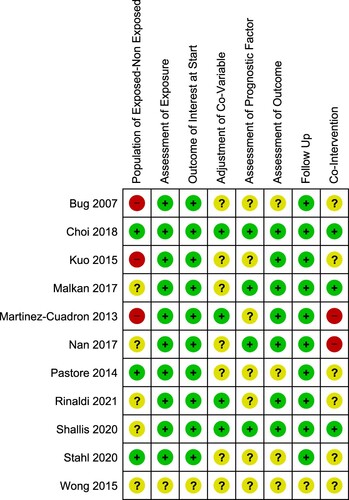

Risk of bias

The studies selected had a low risk of bias in exposure assessment, presence of outcome at the start of the studies, and follow-up duration (). Most of the studies had a moderate risk of bias overall ().

Discussion

Acute myeloid leukemia is a hematological malignancy caused by differentiation block and unregulated proliferation of myeloid progenitors due to mutations [Citation2]. Left untreated, the disease can be fatal in few weeks or months after diagnosis [Citation2]. The incidence rate of AML adjusted with age is 3.6/100,000 population [Citation45]. One of the main cause of death in AML is hyperleukocytosis, defined as WBC of ≥ 100,000/mm3 [Citation10,Citation17]. AML patients with WBC above this cutoff have high risk of complications occurring such as leukostasis [Citation46]. However, leukostasis may also occur with WBC <100,000/mm3 [Citation10,Citation46].

Hyperleukocytosis can be managed by cytoreduction using leukapheresis with or without chemotherapy. In our systematic review and meta-analysis, no statistically significant early mortality benefit from the use of leukapheresis on studies with hyperleukocytosis cutoff of ≥ 95,000/mm3 or 1,00,000/mm3. It is theorized that leukapheresis only remove circulating blast cells and not tissue-infiltrating blast cells or blast-producing stem cells [Citation10]. Also, blast cells which had aggregated in micro-vessels and form cellular plug are not removed by leukapheresis unlike in chemotherapy which may explain the lack of difference in early mortality between two groups [Citation21]. Tumor lysis syndrome which can be circumvented using leukapheresis also did not result in better mortality for leukapheresis group. We believe that the benefit in reducing tumor lysis syndrome risk through using leukapheresis is minimal since patients are already often given allopurinol and adequate hydration to prevent tumor lysis syndrome [Citation15].

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the pooled analysis for early mortality showed no benefit in reducing early mortality. By separating the analysis based on different hyperleukocytosis cutoffs, the heterogeneity was eliminated, which deliver higher quality of evidence. Nevertheless, further studies into the role of leukapheresis in patients with lower leukocyte counts should be conducted as there are still few studies currently available.

We also believe that more studies comparing prophylactic leukapheresis versus therapeutic leukapheresis should be conducted. We initially also attempted to search and conduct pooled analysis on studies evaluating prophylactic versus therapeutic leukapheresis. However, we did not find adequate number of studies for pooled analysis and the studies were heterogenous in methodology. One of the study assessing the role of prophylactic leukapheresis was a study by Göçer et al. [Citation47]. The study showed that the prophylactic leukapheresis group which was performed when no symptoms of leukostasis were present could actually increase overall survival when compared with the symptomatic leukapheresis group [Citation47]. Meanwhile, for early mortality outcome, the prophylactic leukapheresis group appeared to have lower early mortality, however, it did not achieve statistical significance, possibly due to the relatively low number of patients used for the study [Citation47]. In contrast, a study by Berber et al. did not observe statistically significant higher overall survival for the prophylactic leukapheresis group [Citation35]. Indeed, further studies should be conducted to confirm whether prophylactic leukapheresis truly offers benefit or not. Theoretically, it is possible that in patients with leukocytes >100,000/mm3 or in patients with leukostasis, there may already be pronounced tissue ischemia which may mitigate the benefit of leukapheresis. Hence, no mortality benefit is seen when the leukocyte level is very high.

Many of the studies used here had low number of patients. For example, the retrospective cohort study by Malkan et al. evaluated the impact of leukapheresis on 15-day mortality rate in 28 de novo acute myeloid leukemia patients with hyperleukocytosis [Citation43]. The patients were divided into 10 patients receiving leukapheresis and 18 patients not receiving leukapheresis. However, the study did not describe whether the comparator group was given chemotherapy or not. The results of the study by Malkan et al. showed no significant difference in early mortality between leukapheresis group and non-leukapheresis group [Citation43]. Another study by Pastore et al. had 52 newly diagnosed AML patients divided into 20 patients receiving both chemotherapy and leukapheresis, and 32 patients receiving chemotherapy only [Citation27]. This study also showed no benefit of mortality reduction from the use of leukapheresis.

There are two studies by Shallis et al. and Stahl et al. [Citation13,Citation28] with large sample size used for the pooled analysis. The study by Shallis et al. used 219 patients consisting of 187 patients without leukapheresis and 32 patients receiving leukapheresis. However, only a total of 189 patients were available for early mortality analysis. A total of 72.9% of the patients used hydroxyurea as non-intensive cytoreductive therapy and none of the patients received intensive chemotherapy [Citation13]. The results of the study by Shallis et al. showed that there was no statistically significant difference in a 30-day mortality from the use of leukapheresis [Citation13]. The study by Stahl et al. is the largest study used in the pooled analysis of this systematic review and meta-analysis [Citation28]. Both unmatched and matched multivariable analysis from the study showed no benefit from leukapheresis.

There were insufficient studies that compare the reduction of WBC count between leukapheresis and no leukapheresis. Nevertheless, even if using leukapheresis provides better rapid reduction of WBC, this does not seem to be followed by mortality reduction as shown by the pooled analysis. There were also insufficient studies that compare the use of prophylactic versus therapeutic leukapheresis.

This review has several limitations. The first is that all studies were of retrospective cohort designs which is not the best design for experimental treatment. Studies with design of randomized clinical trials are needed to elucidate the association between the use of leukapheresis with early mortality. The second limitation is the small sample size in majority of the studies which may make some of the studies underpowered in finding statistical association. Only two studies which were conducted by Shallis et al. and Stahl et al. had relatively large sample size [Citation13,Citation28].

Conclusion

The use of leukapheresis does not provide early mortality benefit in adult AML patients with hyperleukocytosis. Additional studies with designs of prospective cohort or clinical trials are needed to confirm the result of this study.

Author’s contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that was in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the manuscript; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- De Kouchkovsky I, Abdul-Hay M. Acute myeloid leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2016 update. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6:e441–e441. [cited 2021 Mar 14]. https://www.nature.com/articles/bcj201650.

- Saultz JN, Garzon R. Acute myeloid leukemia: A concise review. J Clin Med. 2016;5, 33. [cited 2020 Dec 11]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4810104/.

- Pelcovits A, Niroula R. Acute myeloid leukemia: A review. R I Med J. 2020;103:38–40.

- Kamath GR, Tremblay D, Coltoff A, et al. Comparing the epidemiology, clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of acute myeloid leukemia with and without acute promyelocytic leukemia. Carcinogenesis. 2019;40:651–660.

- Acute Myeloid Leukemia. - Cancer Stat Facts [Internet]. SEER. 2021 [cited 2021 Mar 14]. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/amyl.html.

- Marbello L, Ricci F, Nosari AM, et al. Outcome of hyperleukocytic adult acute myeloid leukaemia: a single-center retrospective study and review of literature. Leuk Res. 2008;32:1221–1227.

- Ventura GJ, Hester JP, Smith TL, et al. Acute myeloblastic leukemia with hyperleukocytosis: risk factors for early mortality in induction. Am J Hematol. 1988;27:34–37.

- Korkmaz S. The management of hyperleukocytosis in 2017: Do we still need leukapheresis? Transfus Apher Sci Off J World Apher Assoc Off J Eur Soc Haemapheresis. 2018;57:4–7.

- Zhang D, Zhu Y, Jin Y, et al. Leukapheresis and hyperleukocytosis, Past and future. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:3457–3467.

- Röllig C, Ehninger G. How I treat hyperleukocytosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2015;125:3246–3252. [cited 2021 Feb 21]. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-10-551507.

- Dutcher JP, Schiffer CA, Wiernik PH. Hyperleukocytosis in adult acute nonlymphocytic leukemia: impact on remission rate and duration, and survival. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1987;5:1364–1372.

- Burnett AK, Russell NH, Hills RK, et al. A randomized comparison of daunorubicin 90 mg/m2 vs 60 mg/m2 in AML induction: results from the UK NCRI AML17 trial in 1206 patients. Blood. 2015;125:3878–3885.

- Shallis RM, Stahl M, Wei W, et al. Patterns of care and clinical outcomes of patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia presenting with hyperleukocytosis who do not receive intensive chemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61:1220–1225.

- Bewersdorf JP, Zeidan AM. Hyperleukocytosis and leukostasis in acute myeloid leukemia: Can a better understanding of the underlying molecular pathophysiology lead to novel treatments? Cells. 2020;9, 2310. [cited 2021 Mar 22]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7603052/.

- Ali AM, Mirrakhimov AE, Abboud CN, et al. Leukostasis in adult acute hyperleukocytic leukemia: a clinician’s digest. Hematol Oncol. 2016;34:69–78. [cited 2021 Feb 21]. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/hon.2292.

- Porcu P, Cripe LD, Ng EW, et al. Hyperleukocytic leukemias and leukostasis: a review of pathophysiology, clinical presentation and management. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;39:1–18.

- Ganzel C, Becker J, Mintz PD, et al. Hyperleukocytosis, leukostasis and leukapheresis: practice management. Blood Rev. 2012;26:117–122.

- Stucki A, Rivier A-S, Gikic M, et al. Endothelial cell activation by myeloblasts: molecular mechanisms of leukostasis and leukemic cell dissemination. Blood. 2001;97:2121–2129. [cited 2021 Feb 21]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006497120558217.

- Stahl M, Pine A, Hendrickson JE, et al. Beliefs and practice patterns in hyperleukocytosis management in acute myeloid leukemia: a large U.S. web-based survey. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59:2723–2726.

- Shallis RM, Stahl M, Bewersdorf JP, et al. Leukocytapheresis for patients with acute myeloid leukemia presenting with hyperleukocytosis and leukostasis: a contemporary appraisal of outcomes and benefits. Expert Rev Hematol. 2020;13:489–499.

- Ronald H, Benz EJ, Silberstein LE, Heslop H, Weitz JE, Anastasi J, Salama ME, Abutalib SE. Hematology Basic Principles and Practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017. p. 924–953.

- Nan X, Qin Q, Gentille C, et al. Leukapheresis reduces 4-week mortality in acute myeloid leukemia patients with hyperleukocytosis - a retrospective study from a tertiary center. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:1–11.

- Bug G, Anargyrou K, Tonn T, et al. Impact of leukapheresis on early death rate in adult acute myeloid leukemia presenting with hyperleukocytosis. Transfusion (Paris). 2007;47:1843–1850. [cited 2021 Mar 14]. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01406.x.

- Choi MH, Choe YH, Park Y, et al. The effect of therapeutic leukapheresis on early complications and outcomes in patients with acute leukemia and hyperleukocytosis: a propensity score-matched study. Transfusion (Paris). 2018;58:208–216.

- Kuo KHM, Callum JL, Panzarella T, et al. A retrospective observational study of leucoreductive strategies to manage patients with acute myeloid leukaemia presenting with hyperleucocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:384–394. [cited 2021 Feb 27]. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/bjh.13146.

- Martínez-Cuadrón D, Montesinos P, Moscardo F, et al. Treatment With leukapheresis In patients diagnosed With hyperleukocytic acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;122:5046–5046. [cited 2021 Apr 8]. https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/122/21/5046/15346/Treatment-With-Leukapheresis-In-Patients-Diagnosed.

- Pastore F, Pastore A, Wittmann G, et al. The role of therapeutic leukapheresis in hyperleukocytotic AML. PloS One. 2014;9:e95062.

- Stahl M, Shallis RM, Wei W, et al. Management of hyperleukocytosis and impact of leukapheresis among patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) on short- and long-term clinical outcomes: a large, retrospective, multicenter, international study. Leukemia. 2020;34:3149–3160.

- Bewersdorf JP, Giri S, Tallman MS, et al. Leukapheresis for the management of hyperleukocytosis in acute myeloid leukemia—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transfusion (Paris). 2020;60:2360–2369. [cited 2021 Feb 21]. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/trf.15994.

- Rinaldi I, Sari RM, Tedhy VU, et al. Leukapheresis does Not improve early survival outcome of acute myeloid leukemia with leukostasis patients - A dual-center Retrospective Cohort study. J Blood Med. 2021;12:623–633.

- Kasner MT, Laury A, Kasner SE, et al. Increased cerebral blood flow after leukapheresis for acute myelogenous leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:1110–1112.

- Nguyen TH, Bach KQ, Vu HQ, et al. Pre-chemotherapy white blood cell depletion by therapeutic leukocytapheresis in leukemia patients: A single-institution experience. J Clin Apheresis. 2020;35:117–124.

- Van de Louw A, Schneider CW, Desai RJ, et al. Initial respiratory status in hyperleukocytic acute myeloid leukemia: prognostic significance and effect of leukapheresis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57:1319–1326.

- Villgran V, Agha M, Raptis A, et al. Leukapheresis in patients newly diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia. Transfus Apher Sci Off J World Apher Assoc Off J Eur Soc Haemapheresis. 2016;55:216–220.

- Berber I, Kuku I, Erkurt MA, et al. Leukapheresis in acute myeloid leukemia patients with hyperleukocytosis: A single center experience. Transfus Apher Sci Off J World Apher Assoc Off J Eur Soc Haemapheresis. 2015;53:185–190.

- De Santis GC, de Oliveira LCO, Romano LGM, et al. Therapeutic leukapheresis in patients with leukostasis secondary to acute myelogenous leukemia. J Clin Apheresis. 2011;26:181–185.

- Lee H, Park S, Yoon J-H, et al. The factors influencing clinical outcomes after leukapheresis in acute leukaemia. Sci Rep. 2021;11:6426. [cited 2021 Dec 12]. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-85918-8.

- Tan D, Hwang W, Goh YT. Therapeutic leukapheresis in hyperleukocytic leukaemias–the experience of a tertiary institution in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005;34:229–234.

- Thiébaut A, Thomas X, Belhabri A, et al. Impact of pre-induction therapy leukapheresis on treatment outcome in adult acute myelogenous leukemia presenting with hyperleukocytosis. Ann Hematol. 2000;79:501–506.

- Aqui N, O’Doherty U. Leukocytapheresis for the treatment of hyperleukocytosis secondary to acute leukemia. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2014;2014:457–460.

- Hölig K, Moog R. Leukocyte depletion by therapeutic Leukocytapheresis in patients with leukemia. Transfus Med Hemotherapy. 2012;39:241–245. [cited 2021 May 23]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3434324.

- Shaz BH, et al. Chapter 71 - therapeutic leukapheresis. In: Hillyer CD, Shaz BH, Zimring JC, editor. Transfus Med hemost. San Diego: Academic Press; 2009. p. 405–406. [cited 2021 Dec 12]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123744326000713.

- Malkan UY, Ozcebe OI. Leukapheresis do not improve early death rates in acute myeloid leukemia patients with hyperleukocytosis. Transfus Apher Sci Off J World Apher Assoc Off J Eur Soc Haemapheresis. 2017;56:880–882.

- Wong GC. Hyperleukocytosis in acute myeloid leukemia patients is associated with high 30-day mortality which is not improved with leukapheresis. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:2067–2068.

- Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. [cited 2021 Mar 28]. https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.3322/caac.21208.

- Zuckerman T, Ganzel C, Tallman MS, et al. How I treat hematologic emergencies in adults with acute leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:1993–2002. [cited 2021 Mar 28]. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-04-424440.

- Göçer M, Kurtoğlu E. Effect of prophylactic leukapheresis on early mortality and overall survival in acute leukemia patients with hyperleukocytosis. Ther Apher Dial. [cited 2021 May 30]. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1744-9987.13645.