ABSTRACT

Objectives

To investigate the impact of marriage on multiple myeloma (MM) survival, and the role of factors such as age, sex, and income in this relationship.

Material and Methods

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database was searched for eligible MM patients between 2007 and 2016. We compared overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) differences by the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank tests. The hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for OS and CSS were estimated by Cox regression models. A 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was used to minimize the covariates differences between married and unmarried group.

Results

This study identified 48,952 eligible patients diagnosed with MM, comprising 29,607 married patients, 5,147 divorced/separated patients, 6,851 single patients, and 7,347 widowed patients. Married MM patients were found to be an independent protective prognostic factor for OS and CSS (all P < 0.001). The survival advantage of marriage still remained in 1:1 matched-pair analysis. The stratified analysis further revealed that the OS and CSS was poorer in unmarried than married MM patients across different age of diagnosis, sex, income, race, and period of diagnosis subgroups (all P < 0.05). The beneficial effect of marriage on the survival of MM was particularly prominent in younger (<65 years) patients, males, higher income patients, non-Hispanic whites, and more recent years.

Conclusion

Married patients with MM tend to have better OS and CSS likely due to their higher income, education level, insurance and receipt of chemotherapy.

Background

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the malignant neoplasm of plasma cells that build up in bone marrow and form tumors in the bones. An estimated 30,770 new cases of MM occur in the USA in 2018, and the 5-year survival rate is 50.7% [Citation1]. New development in the advancement of drugs and therapies these past few decades have substantially improved the overall survival (OS) of patients with MM. These treatments include autologous stem cell transplantation, immunomodulatory agents such as thalidomide and lenalidomide, as well as proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib [Citation2–6]. Age, health status, race, and socio-economic status (SES) were found to be related to receiving treatment for MM in the United States [Citation7, Citation8]. Although the treatment of MM has improved, the incidence of MM in the United States has increased in recent years [Citation6,Citation9]. It is still necessary to further understand the factors that can affect the prognosis of MM.

Recently, multiple studies have found that being married is a favorable prognostic factor in the survival of various cancers, including that of the head and neck, stomach, and liver [Citation10–12]. Among the top 10 clinically significant malignancies in the United States, unmarried patients were more likely to develop metastatic cancer and die from their cancer [Citation13]. The available evidence suggests that the survival advantages of being married are related to early diagnosis of cancer, receiving recommended or aggressive therapy, a higher economic status, and better social support [Citation13–15]. Although the survival advantage of marriage in solid tumors has been extensively studied, the role of marriage in hematological malignancies is still controversial. Previous study reported that the marital status was associated with an increased risk of cancer-specific death in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [Citation16]. Since the relationship between marital status and MM has not been fully studied, we investigated the effect of marriage on OS and cancer-specific survival (CSS) of MM. In addition, we further investigated the role of factors such as age, sex, and income in the relationship between marital status and MM survival.

Material and Methods

Data source and study population

The SEER*Stat software (version 8.3.6) was used to obtain patient information from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) public database. This database contains information from 18 population-based cancer registries and covers about 27.8% of the American population (https://seer.cancer.gov/). MM patients were identified using the ICD-O-3 histological diagnostic code 9732/3 between 2007 and 2016. Information on year of diagnosis, age at diagnosis, sex, race, marital status, insurance, median household income, education level (% at least Bachelor’s degree), chemotherapy, survival time, vital status, and cause-specific death were extracted from the SEER database. We excluded cases that were diagnosed only on death certificates or autopsy, <18 years of age, or cases where some of the information was not available. We did not require approval from the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University because the public SEER database was free for researchers and no human subjects were used in our study.

Variable definitions

Patients were divided into five groups based on age at diagnosis: 44 years or younger, 45–54 years, 55–64 years, 65–74 years, and ≥75 years. Patients were also classified into two groups according to the year of diagnosis (2007–2011 and 2012–2016) to adjust for the survival difference resulting from therapeutic developments for MM. Race was categorized into non-Hispanic white (White), non-Hispanic black (Black), Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander (Asian). Insurance status was defined as insured (private insurance), Medicaid, or uninsured. Marital status was divided into married and unmarried (single, divorced/separated, and widowed) status for subgroup analysis. Individual household income and education levels are not available in SEER and therefore data of each patient’s county from the American Community Survey were used. Income was approximated by median household income (in quartiles) and was divided into higher income (quartile 1–2), and lower income (quartile 3–4) due to similarities across quartiles in survival. Some factors such as disease stage, metastasis, complications, and treatment were not captured in SEER and therefore were not included in our study. The primary outcomes of this study were OS and CSS, which were calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death from any cause or death from MM, respectively. Patients who were still alive at the end of the follow-up or patients who died of causes other than MM were regarded as censored.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of MM patients with different marital status were compared using chi-square test. The Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank tests were used to compare OS and CSS differences based on marital status stratification. The hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for OS and CSS were estimated by Cox regression models. We then used multivariate Cox regression model with a backward stepwise selection to select variables correlated with the outcome, with a P value < 0.15 as the selection criterion. Forward selection was also performed to verify the predictors. The concordance index (C-index) using bootstrapping with 1,000 resamples and the area under the time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) were used to evaluate discrimination of the model [Citation17]. A C-index or AUC of 0.5 indicates no discrimination, while one of 1.0 indicates perfect discrimination. Calibration curves were plotted using a bootstrap approach with 1,000 resamples to compare the predicted survival probability with the observed survival probability [Citation18]. The 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was used to minimize the covariates differences between married and unmarried group and to verify the reliability of results. The propensity score without replacement was calculated with a binary logistic regression for each patient in the married and unmarried group. SPSS version 24.0 and the R software (version 3.4.3; http://www.r-project.org/) were used for statistical analysis. A two-sided probability value of P ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient baseline characteristics

From the year 2007 to 2016, 48,952 patients were diagnosed with MM. The mean age at diagnosis of MM patients was 68 years, and the median survival was 32 months. Patients with MM included 27,411 (56%) males and 21,541 (44%) females (). Among these patients, 29,607 (60.5%) were married, 5,147 (10.5%) were divorced/separated, 7,347 (15.0%) were widowed, and 6,851 (14.0%) were single. The mean age at diagnosis for married, divorced/separated, widowed, and single patients were 67.3, 65.5, 78.2, and 62.3 years, respectively. Married patients were more likely to be male and white, while those who were widowed were more likely to be female and elderly (age ≥75 years). In addition, married patients were more likely to obtain private insurance, have higher median household income (quartiles 1–2), have higher educational level (quartiles 1–2), and undergo chemotherapy than unmarried patients. The baseline characteristics such as age, sex, year of diagnosis, race, insurance status, median household income, education level, and chemotherapy among the four marital group were statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of multiple myeloma patients according to marital status.

Survival analysis

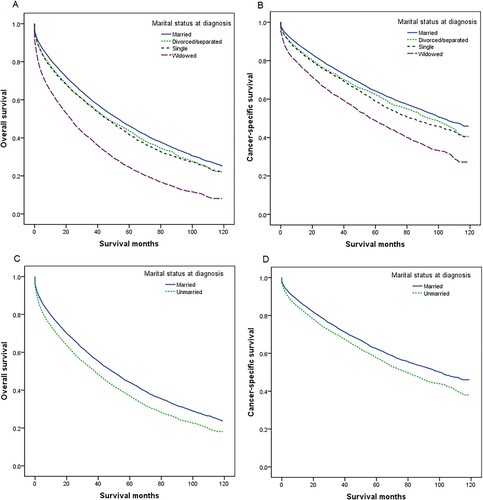

The 5-year OS rates for the married, divorced/separated, single, and widowed subgroups were 46.4%, 43.8%, 41.7%, and 24.6%, respectively, which were significantly different (Plog-rank < 0.001; (a)). After adjustment for age, sex, year of diagnosis, race, insurance status, median household income, education level, and chemotherapy, the multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that the divorced/separated (HR, 1.214; 95% CI, 1.163–1.268; P < 0.001), single (HR, 1.332; 95% CI, 1.280–1.386; P < 0.001), and widowed (HR, 1.364; 95% CI, 1.315–1.414; P < 0.001) patients had a higher risk of all-cause mortality relative to married patients (). The 5-year CSS rates for the married, divorced/separated, single, and widowed subgroups were 64.3%, 62.5%, 58.8%, and 48.9%, respectively, which showed that married patients also had better CSS than other patients (Plog-rank < 0.001; (b)). Multivariate analysis showed unmarried groups (divorced/separated: HR, 1.172; 95% CI, 1.107–1.241; single: HR, 1.312; 95% CI, 1.246–1.382; widowed: HR, 1.333; 95% CI, 1.269–1.401) also had a higher risk of MM-specific mortality than married group (all P < .001; ). In addition, both univariate and multivariate analysis showed that age, sex, year of diagnosis, race, insurance status, median household income, education level, and chemotherapy were identified as significant risk factors for OS (all P < 0.05; ). The elderly, uninsured, lower median household income, lower county-level education, no/unknown chemotherapy were independent unfavorable prognostic factors for OS, while female, Black and recent period of diagnosis were independent favorable prognostic factors (). For CSS of MM patients, these factors (except chemotherapy) also show similar trends ().

Figure 1. Survival curves for patients with multiple myeloma according to marital status. (a) Overall survival; (b) cancer-specific survival; (c) Overall survival after propensity score matching (PSM); and (d) cancer-specific survival after PSM.

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analyses of overall survival in multiple myeloma patients.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analyses of multiple myeloma cancer-specific survival.

The C-index of the multivariate Cox model was 0.660 for OS and 0.631 for CSS. The 3- and 5-year AUCs were 0.687 and 0.698 for OS, respectively, and 0.639 and 0.637 for CSS (Supplementary Figure 1). The above results demonstrated that the model for OS showed better discriminative ability than for CSS. The calibration plots for the 3- and 5-year OS and CSS showed good agreement between predicted and observed outcome probabilities (Supplementary Figure 1).

We then performed a PSM analysis to balance potential confounders. After the 1:1 PSM, we obtained 13964 matched pairs. All the baseline characteristics between married and unmarried group were well balanced (P > 0.05, ). The 5-year OS rates for the married and unmarried groups were 44.1% and 37.0%, respectively. The 5-year CSS rates for the married and unmarried groups were 62.4% and 57.7%, respectively. The log-rank test showed that OS and CSS of married patients were significantly better than that of unmarried patients (Plog-rank < 0.001, (a,d)). The univariate Cox regression analysis showed unmarried group still had higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 1.242; 95% CI, 1.201–1.283; P < 0.001) and MM-specific mortality (HR, 1.209; 95% CI, 1.157–1.263; P < 0.001) than the married group ().

Table 4. Baseline characteristics of multiple myeloma patients according to marital status after PSM.

Table 5. Univariate analysis of overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) for patients with multiple myeloma after propensity score matching (PSM).

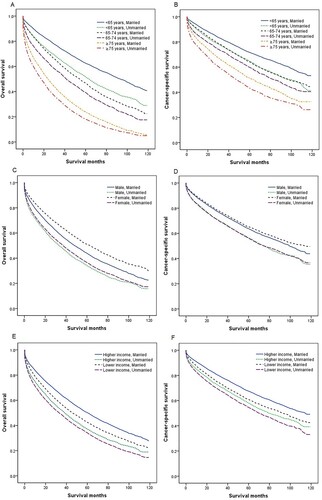

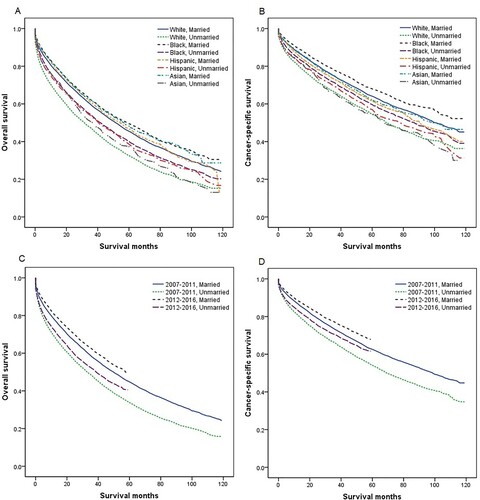

We further stratified the effect of marital status on MM survival by age, sex, income, and race. Multivariate analysis showed unmarried MM patients had worse OS and CSS than married patients in different age subgroups (all P < 0.001), although the adjusted HR of unmarried patients was the highest in patients <65 years compared with 65–74 years and ≥75 years ( and ). We also found that unmarried status was an unfavorable prognostic factor for the OS and CSS of MM across different subgroups of sex, income, and race (all P < 0.001), with the adjusted HR of unmarried patients greater in male than in female, in higher income than lower income, and in Whites than other races (, and ). Owing to new developments in drugs and therapies for the treatment of MM over time, we also conducted a subgroup analysis by period of diagnosis. Married MM patients had better OS and CSS in each period of diagnosis (all P < 0.001), and the adjusted HR of unmarried patients was higher in 2012–2016 than in 2007–2011 ( and ).

Figure 2. Overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) in patients with multiple myeloma by age at diagnosis, sex, and income. (a) Age at diagnosis and marital status, OS; (b) age at diagnosis and marital status, CSS; (c) sex and marital status, OS; (d) sex and marital status, CSS; (e) income and marital status, OS; and (f) income and marital status, CSS.

Figure 3. Overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) in patients with multiple myeloma by race and period of diagnosis. (a) Race and marital status, OS; (b) race and marital status, CSS; (c) period of diagnosis and marital status, OS; and (d) period of diagnosis and marital status, CSS.

Table 6. Multivariate adjusted HRs for overall survival (OS) and multiple myeloma cancer-specific survival (CSS) associated with marital status (unmarried vs married) stratified by age at diagnosis, sex, socio-economic status (SES), race, and period of diagnosis.

Discussion

In our study, we confirmed previous report that MM patients in recent years had improved survival rates compared with those diagnosed earlier, which may be related to the significant increase in MM treatment in recent years [Citation19,Citation20]. Our results also confirmed that age was a risk factor for MM survival [Citation20]. Older patients (≥75 years) had the worst survival likely due to existing comorbidities and receiving fewer novel treatment [Citation7,Citation21]. We noted that non-Hispanic blacks had better OS and CSS than non-Hispanic whites, which was similar to several reports [Citation22,Citation23]. However, recent studies found that the racial differences in the prognosis of MM seemed to be alleviated by obtaining appropriate treatment options [Citation24,Citation25]. The weak protective effect of chemotherapy on OS in MM patients should be viewed with caution, given that there are many possible confounding factors. Patients who did not receive chemotherapy may have received other forms of treatment. Owing to the lack of data on treatment variations in the SEER database, we were unable to get a clearer view of the impact that chemotherapy had on MM survival. This study confirmed prior findings that MM patients in higher socio-economic status had better survival [Citation26,Citation27]. Patients with lower income level tend to lack accessibility to systemic treatment, which ultimately leads to poorer prognosis [Citation7,Citation26].

Using a larger and updated SEER database (2007–2016), we discovered that marriage was an independent protective factor for OS and CSS in all MM adult patients, even after adjusting for confounding factors. Our results confirmed a previous study by Costa et al,[Citation27], which reported that married status was associated with better OS in MM patients <65 years using SEER data from 2007 to 2012. A recent article, using patient data from a tertiary care center, found that unmarried status had a negative effect on OS in a univariate analysis but not in a multivariate analysis that included known biological risk factors [Citation28]. Owing to the lack of data on disease characteristics of patients in the SEER database, future studies aimed at investigating the impact of marital status on the survival of MM patients in community practices after accounting for disease biology-related factors are required.

Our analysis showed that married patients had the best OS and CSS, followed by divorced/separated and single patients, and widowed patients had the worst survival. Marital disparities in MM survival may be due to the comprehensive effects of variables such as age, insurance, income, and education in different marital status. We further found married MM patients had better OS and CSS than unmarried patients across different age subgroup, and the survival difference was more significant in patients <65 years. We also observed that the survival advantage of married MM patients persisted across subgroups of sex, income, race, and period of diagnosis, with the effect of marriage on MM survival greater in males, higher income, Whites, and in more recent years. The above results suggest that younger, male, white, or higher economic status MM patients are more likely to benefit from marriage, which may be due to their higher marriage rate. It is worth noting that the effect of marriage on MM survival has become increasingly important in recent years. Physicians should therefore pay more attention to unmarried MM patients to maximize their survival improvement.

From the results of this study, it shows that married MM patients are more likely to have insurance, higher income, higher education level, and receive chemotherapy, which may be the reasons for their better prognosis. Patient with insurance are more likely to present with early-stage diseases and receive appropriate treatment including chemotherapy [Citation7, Citation29]. The higher income of married patients makes them more accessible to novel therapies which were expensive [Citation7]. Moreover, married patients were mostly diagnosed at an earlier age than unmarried patients, making them more likely to be eligible for the autologous stem cell transplantation [Citation30]. Since the age at diagnosis was lower in married patients and the SEER database did not differ between smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM) and MM diagnosis, lead time bias might also be an explanation for better survival in married patients.

Physiologically, the social and emotional support afforded by the spouse may help married patients suffer less depression and distress, which may improve the overall treatment trajectory resulting in improve prognosis [Citation31–33]. Married patients may have better adherence with definitive therapies due to encouragement from their spouses [Citation34]. The role of caregiving provided by the spouse may also contributed to decreasing overall disease burden by sharing workloads (e.g. housework) and treatment adjuncts (e.g. injections) [Citation35]. In addition, unmarried patients tend to have a higher rate of major depression, which may suppress immune function, leading to tumor progression and death [Citation36–38]. The limited types of data collected from the SEER database prevent us from having a more comprehensive view of married patients and the factors that contribute to their better survival. Factors such as social and psychological support, coping mechanism, and treatment compliance could be further explored in future studies.

Based on the largest population data to date, our study investigated the relationship between marital status and prognosis of MM in greater depth; however, it was still subject to some limitations. First, since only marital status at diagnosis was recorded, we could not explain the changes in marital status after the diagnosis. Second, the SEER database lacked information on disease biology-related factors that might influence survival, such as cytogenetics, disease staging, and other clinicopathological features. Third, other important information about the specific kind of treatments was lacked, and which could not be adjusted for survival. Fourth, the present study had a retrospective design, and so psychological tests could not be used to confirm the relationship between psychosocial factors and the survival of unmarried MM patients. Focused group interviews or patient level data and contact may be needed to understand the real mechanisms for why married MM patients do better, which could help find another way of improving outcomes for all MM patients.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding the above-mentioned limitations, our study is the first to focus on marital status and MM survival. Unmarried MM patients had lower OS and CSS than married MM across subgroups of age, sex, income, race, and year of diagnosis. The lower OS and CSS of unmarried patients may be due to their absence of insurance, lower economic conditions, lower education level, and less access to appropriate treatment, which leads to delays in diagnosis and insufficient treatment. Although novel treatments can improve the survival of MM patients, it ultimately do not reach majority of patients. The management of patient’s with MM needs to be multi-dimensional. Studies investigating the effect of marriage on MM survival may yield previously unexplored factors. Our article emphasizes the need to take additional measures to eliminate outcome disparities based on marital status in MM. Interventions that provide more social support, disease education, and access to treatment for unmarried patients may help improve their survival.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30.

- Al Hamed R, Bazarbachi AH, Malard F, et al. Current status of autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2019;9:44.

- Attal M, Harousseau JL, Leyvraz S, et al. Maintenance therapy with thalidomide improves survival in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:3289–3294.

- Richardson PG, Blood E, Mitsiades CS, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of lenalidomide therapy for patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:3458–3464.

- Kumar S, Flinn I, Richardson PG, et al. Randomized, multicenter, phase 2 study (EVOLUTION) of combinations of bortezomib, dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, and lenalidomide in previously untreated multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;119:4375–4382.

- Costa LJ, Brill IK, Omel J, et al. Recent trends in multiple myeloma incidence and survival by age, race, and ethnicity in the United States. Blood Adv. 2017;1:282–287.

- Fakhri B, Fiala MA, Tuchman SA, et al. Undertreatment of older patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma in the era of novel therapies. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18:219–224.

- Fiala MA, Wildes TM, Vij R. Racial disparities in the utilization of novel agents for frontline treatment of multiple myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20:647–651.

- Turesson I, Bjorkholm M, Blimark CH, et al. Rapidly changing myeloma epidemiology in the general population: increased incidence, older patients, and longer survival. Eur J Haematol. 2018;101:237–244.

- Osazuwa-Peters N, Christopher KM, Cass LM, et al. What's love Got to do with it? marital status and survival of head and neck cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2019;28:e13022.

- Jin JJ, Wang W, Dai FX, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with gastric cancer. Cancer Med. 2016;5:1821–1829.

- Wu W, Fang D, Shi D, et al. Effects of marital status on survival of hepatocellular carcinoma by race/ethnicity and gender. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:23–32.

- Aizer AA, Chen MH, McCarthy EP, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3869–3876.

- Goodwin JS, Hunt WC, Key CR, et al. The effect of marital status on stage, treatment, and survival of cancer patients. JAMA. 1987;258:3125–3130.

- Uchino BN. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med. 2006;29:377–387.

- Zhao J, Su L, Zhong J. Risk factors for cancer-specific mortality and cardiovascular mortality in patients With diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20:e858–ee63.

- Uno H, Cai T, Pencina MJ, et al. On the C-statistics for evaluating overall adequacy of risk prediction procedures with censored survival data. Stat Med. 2011;30:1105–1117.

- Crowson CS, Atkinson EJ, Therneau TM. Assessing calibration of prognostic risk scores. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016;25:1692–1706.

- Ailawadhi S, Frank RD, Sharma M, et al. Trends in multiple myeloma presentation, management, cost of care, and outcomes in the medicare population: A comprehensive look at racial disparities. Cancer. 2018;124:1710–1721.

- Ailawadhi S, Aldoss IT, Yang D, et al. Outcome disparities in multiple myeloma: a SEER-based comparative analysis of ethnic subgroups. Br J Haematol. 2012;158:91–98.

- Costa LJ, Zhang MJ, Zhong X, et al. Trends in utilization and outcomes of autologous transplantation as early therapy for multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1615–1624.

- Waxman AJ, Mink PJ, Devesa SS, et al. Racial disparities in incidence and outcome in multiple myeloma: a population-based study. Blood. 2010;116:5501–5506.

- Ailawadhi S, Parikh K, Abouzaid S, et al. Racial disparities in treatment patterns and outcomes among patients with multiple myeloma: a SEER-medicare analysis. Blood Adv. 2019;3:2986–2994.

- Ailawadhi S, Jacobus S, Sexton R, et al. Disease and outcome disparities in multiple myeloma: exploring the role of race/ethnicity in the cooperative group clinical trials. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8:67.

- Fiala MA, Wildes TM. Racial disparities in treatment use for multiple myeloma. Cancer. 2017;123:1590–1596.

- Fiala MA, Finney JD, Liu J, et al. Socioeconomic status is independently associated with overall survival in patients with multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:2643–2649.

- Costa LJ, Brill IK, Brown EE. Impact of marital status, insurance status, income, and race/ethnicity on the survival of younger patients diagnosed with multiple myeloma in the United States. Cancer. 2016;122:3183–3190.

- Evans LA, Go R, Warsame R, et al. The impact of socioeconomic risk factors on the survival outcomes of patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: A cross-analysis of a population-based registry and a tertiary care center. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21:451–460.

- Woods LM, Rachet B, Coleman MP. Origins of socio-economic inequalities in cancer survival: a review. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:5–19.

- Rajkumar SV. Treatment of multiple myeloma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:479–491.

- Cairney J, Boyle M, Offord DR, et al. Stress, social support and depression in single and married mothers. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:442–449.

- Goldzweig G, Andritsch E, Hubert A, et al. Psychological distress among male patients and male spouses: what do oncologists need to know? Ann Oncol. 2010;21:877–883.

- Zimmaro LA, Sephton SE, Siwik CJ, et al. Depressive symptoms predict head and neck cancer survival: examining plausible behavioral and biological pathways. Cancer. 2018;124:1053–1060.

- Aizer AA, Paly JJ, Zietman AL, et al. Multidisciplinary care and pursuit of active surveillance in low-risk prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3071–3076.

- Molassiotis A, Wilson B, Blair S, et al. Living with multiple myeloma: experiences of patients and their informal caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:101–111.

- Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA. 1996;276:293–299.

- Sklar LS, Anisman H. Stress and coping factors influence tumor growth. Science. 1979;205:513–515.

- Antoni MH, Dhabhar FS. The impact of psychosocial stress and stress management on immune responses in patients with cancer. Cancer. 2019;125:1417–1431.