ABSTRACT

Background

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is the standard of care in candidate patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. In Chile, its indication has been expanding as have centers dedicated to this type of therapy. Here, we present the results of the first 50 patients from a Chilean reference center.

Methods

This was a retrospective analytical study of 50 patients referred to the Arturo López Pérez Foundation to receive ASCT. Patients newly diagnosed or on subsequent lines of treatment were allowed. As primary objectives, the deepening of response with ASCT and subsequent results on overall survival and progression-free survival were analyzed.

Results

Among 50 patients with a median follow-up of 24 months, ASCT managed to deepen responses going from at least very good partial response of 57.4%–82.5% (p = .01); complete response increased from 27.6% to 52.5% (p = .02). In turn, a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 39 months was estimated and the median overall survival was not reached. The most important factor predicting PFS is measurable residual disease.

Conclusions

ASCT is an effective strategy for prolonged progression-free survival and deepening responses. Public–private collaboration is a crucial element in reducing the gaps in access to this type of complex but highly effective therapy.

Introduction

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is a widely used procedure in patients with multiple myeloma (MM) and is included in both international guidelines [Citation1–4] and national protocols [Citation5]. Its efficacy lies mainly in achieving a deeper response and being able to extend progression-free survival; extensive evidence supports its use [Citation6–10]. The incidence of MM in Chile has been estimated at around 3.3 per 100,000 inhabitants/year, but only 6.6% receive ASCT (18% of those considered candidates) [Citation11]. There are national reports [Citation12–14], however, suggesting no progression-free survival with current therapies or deepening of responses – these are the best outcomes and justify the use of this therapy.

The Arturo López Pérez Foundation (FALP) transplant program arose out of a need to provide coverage to our members and support the public system. In April 2019, we performed the first ASCT. To date, 82 transplants have been performed (including lymphomas). The objective of the present study is to present the results of the first 50 patients with MM.

Patients and methods

Study design and patient selection

This was an observational, retrospective, and descriptive study. Patients older than 18 years with a diagnosis of MM who underwent ASCT in FALP between April 2019 and December 2021 were included. Diagnoses were confirmed by bone marrow study records (medullary aspirate or biopsy). Patients with at least a partial response after induction as well as those with relapsed disease were accepted. The patients corresponded to those who were treated at our center, those from the public system, and institutional hospitals of the armed forces. The information was obtained before start induction therapy by reviewing the Electronic Clinical Record. The dates of death were obtained from the website of the Civil Registry (www.srcei.cl). The scientific ethics committee at our institution approved this study.

Procedures

Hematopoietic progenitors were mobilized with Filgrastim granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) 10 μg/kg/day. At four day of mobilization, a CD34 cell count was performed; apheresis was carried out on fifth day if the count was greater than 20 cells/µL. Plerifaxor was indicated if the CD34 cell count was less than 20 cells/µL (in patients < 80 kg fixed dose of 20 mg, those > 80 kg fixed dose of 24 mg). Apheresis was performed with the Terumo BCT Spectra Optia system. The collection product was stored in bags with ACD (citric acid, sodium citrate, and dextrose) in a Haier Biomedical, HYC-68ª refrigerator exclusively for stem cell collection. The minimum count to perform the procedure was set at 2 × 106 CD34 cells/kg. Conditioning for the transplant consisted of Melphalan 200 mg/m2 (the dose was reduced to 140 mg/m2 in patients with creatinine clearance less than 60 ml/min or age >70 years). Tandem transplants were not performed. G-CSF was started on fifth day after the hematopoietic progenitor infusion, and all patients received antimicrobial prophylaxis during the period of neutropenia according to local protocols. The use of post-transplant maintenance was left to the discretion of the treating physician; the recommendation was at least one year with Lenalidomide.

Objectives and variables

The main objective was to analyze the profile of patients with Multiple Myeloma undergoing ASCT and their results. Clinical, laboratory, and imaging variables were analyzed. Cytogenetic alterations were not analyzed because they are not performed routinely in Chile. A descriptive analysis of the autologous transplant process was performed. Responses before and after transplantation were analyzed according to the IMWG criteria [Citation15].

Numerical variables were described with median values. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square test and continuous variables using T-student or Mann–Whitney as appropriate. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences were estimated using the log-rank or Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon method as appropriate. A value p < .05 was considered significant. The analysis used GraphPadPrism 9 software.

Results

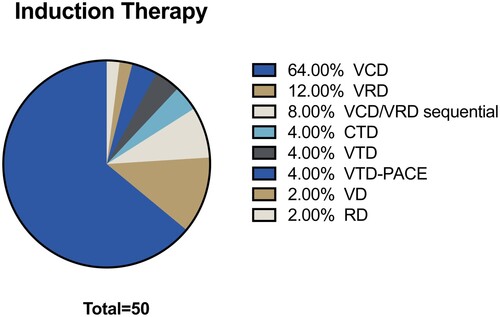

The median age was 58 years and 66% were male (). The main clinical manifestations were bone compromise and anemia. The induction scheme prior to transplantation was bortezomib-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone (VCD) () followed by bortezomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone (VRD). The median of cycles was 4–6. Eight percent of the patient received VRD immediately after VCD to deepen response, since they obtained only stable disease. Twelve percent patients are admitted as rescue therapy after relapse, with a median of two years of progression-free survival, they had previously received chemotherapy with VCD and VTD schemes, in similar proportion. The median time from induction to transplantation was six months.

Figure 1. Schemes of chemoimmunotherapy prior to autologous transplant. V = Bortezomib. R = Lenalidomide. T = Thalidomide. D = Dexamethasone. PACE = Cisplatin/doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide/etoposide.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT).

In all patients, mobilization was performed with Filgrastim 600 µg subcutaneously per day. Patients with a count of less than 20/µl corresponded to 64.9% (plerixafor was administered to them 10 h prior to apheresis). Apheresis was performed in a protected isolation unit in the medical-surgical service of our institution. In 94.3% of the cases, there was a unique apheresis session. The remaining cases required two sessions. The mean collection was 4.49 × 106 cells/kg. Here, 96% of the product obtained in the apheresis was kept fresh, and only 4% was sent to cryopreservation. The conditioning regimen consisted of Melphalan 200 mg/m2 for most; 18% of the patients had their dose reduced to 140 mg/m2 either due to age over 70 years or chronic kidney disease. The average hospital stay was 18.5 days (range 15–39). The period of aplasia lasted 8.8 days (range 7–33 days), and 84% required platelet transfusion and 12% required red blood cell transfusion. There was no early mortality related to ASCT.

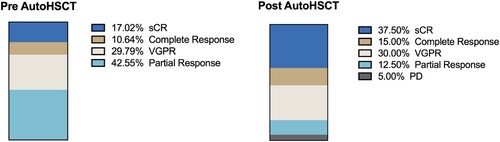

Regarding effectiveness, 63% were admitted with at least a very good partial response (VGPR) or better (). In this scenario, the transplant proceeded to deepen these responses with statistically significant differences for patients with at least complete response improving from 27.6% to 52.5% (p = .02), and at least VGPR from 57.4% to 82.5% (p = .01). The benefit in patients with complete response (CR) is to deepen by 40% to stringent CR. Measurable residual disease (MRD) was measured in 60% of patients, of whom 63% were negative. In addition, 5% of patients had early progression before three months after transplantation.

Figure 2. Response criteria for patients with multiple myeloma before and after autologous transplant. VGPR: very good partial response. sCR: strict complete response. PD: disease progression. AutoHSCT: autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

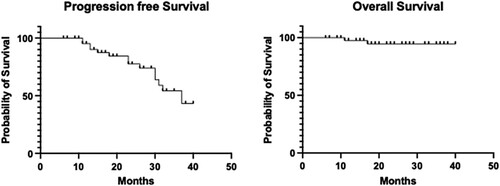

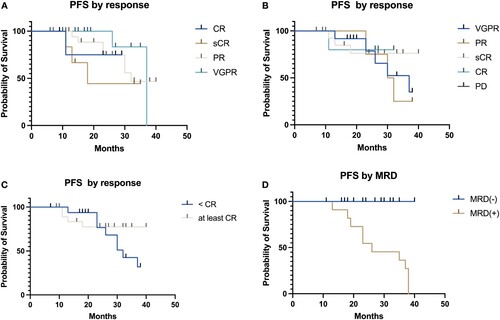

The median overall survival was not reached at a median follow-up of 24 months (). The median progression-free survival (PFS) was estimated to be 39 months. No significant differences in survival were found regarding post-transplant response (), but patients with a complete response had longer PFS (median not reached versus 32 months p = .2). Interestingly, pre-transplant responses were also not statistically significant with respect to progression-free survival (p = .39), thus justifying the inclusion of patients in partial response. The most important factor that predicts PFS is MRD ((D), p < .01), patients with a positive MRD have a median PFS of 26 months compared to patients with a negative MRD, with median PFS don’t reach, and without progressions.

Figure 3. Progression-free survival and overall survival in patients with multiple myeloma undergoing autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Figure 4. Progression-free survival in patients with multiple myeloma undergoing autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant according to pre-transplant (A), post-transplant response criteria (B–C) and measurable residual disease post-transplant (D).

Regarding adverse events (), acute diarrhea was the most frequent adverse event but was mostly mild (grade 1–2). Febrile neutropenia was the second most common adverse event and was seen mostly without microbiological documentation. The incidence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection was very low (2%). Events related to the graft were rare. With one case of delayed engraftment (at day 42 from stem cell infusion, as contributing factors, the infusion of 2.3 × 106 CD34 cells/kg and febrile neutropenia with prolonged antibiotic requirements are described) and one case of engraftment syndrome. There was an adequate response to corticosteroid therapy.

Table 2. Adverse events reported in patients undergoing autologous transplant.

Discussion

ASCT is an effective procedure that deepens responses and prolongs progression-free survival. It is the standard of care even in the era of targeted therapies. The results seen here in terms of depth of response and progression-free survival are comparable to immunomodulator and/or proteasome inhibitor studies. The IFM2005-1 study [Citation16] with the bortezomib-dexamethasone scheme and consolidation with ASCT showed an increase in response of at least VGPR from 37.7% to 54.3% with a median progression-free survival of 36 months. These results were replicated by the French group with a median progression-free survival of 30 months [Citation8].

However, a comparison of regimens including a triplet with immunomodulator and proteasome inhibitors shows that the median progression-free survival fluctuates around 50 months, which is higher than our results. The IFM2009 study [Citation6] shows that the VRD scheme for three cycles of ASCT: The complete response rate was 59% and VGPR 29% with median progression-free survival of 50 months. The PETHEMA/GEM study [Citation17] used a VTD scheme and autologous transplant. The results showed an increase in the rate of complete responses from 35 to 57% with a median progression-free survival of 56 months.

In this scenario, and considering the availability of biosimilar drugs, the possibility arises of using immunomodulators during induction. The French group showed that the VTD scheme is superior to VCD in terms of depth of response prior to transplantation [Citation18]; however, its follow-up has not yet been reported to assess differences in post-transplant response or survival. The CIBMTR registry [Citation19] compared the results of 914 patients with induction of VRD versus 221 patients with VCD: There were no significant differences in response after induction (VGPR or better: 82% versus 79%, respectively). Significant differences in progression-free survival were recorded with medians of 44 versus 34 months (VRD and VCD, respectively); OS medians were not reached. However, the populations analyzed were different: Patients with VCD had a higher prevalence of renal failure and less use of maintenance interventions. When performing multivariate analysis, induction with VCD and VRD did not show significant differences, but maintenance and cytogenetic risk did (and were probably the confounding factors of the multivariate analysis). Similar results were recently replicated by MD Anderson [Citation20]. In a retrospective analysis, 322 patients with VCD versus VRD scheme were evaluated as an induction to ASCT. No differences in progression-free survival or overall survival were noted despite a higher rate of complete responses post-ASCT with VRD scheme. In this scenario, rather than changing the induction scheme, an adequate risk stratification should be optimized at diagnosis via FISH. Maintenance should be optimized with combined therapy in those at high risk and ideally continue until progression.

Moreover, previously the same CIBMTR registry [Citation21] showed that more than the choice of induction therapy (doublet or triplet), the most relevant choice in the clinical outcomes of patients who undergo ASCT is maintenance therapy. The STAMINA study showed that those who discontinued lenalidomide maintenance at 38 months had lower progression-free survival than those who continued [Citation22,Citation23]. Therefore, this is probably the crucial element to be able to improve and consolidate the results of the ASCT. The recent DETERMINATION study [Citation24] with a VRD scheme and consolidation with ASCT and maintenance lenalidomide until progression demonstrated a median PFS of 67.5 months. Thus, this is now the standard of care pending the inclusion of quadruplets in the first line once they are consolidated with greater follow-up of the results of the pivotal studies (e.g. GRIFFIN, CASSIOPIEA) [Citation9,Citation10].

The incidence of secondary neoplasms during maintenance has been a subject of high controversy. In patients with ASCT and maintenance with lenalidomide, a global incidence of around 5.8% of secondary neoplasms is reported at three years [Citation25] of which practically a third (35%) corresponds to non-invasive skin neoplasms. The associated mortality to emerging neoplasms is very low (1%) [Citation26]. Its use in systemic reviews and pivotal studies shows not only an improvement in progression-free survival, but also an improvement in overall survival [Citation27–30].

One of the features highlighted by our series is that achieving a complete post-transplant response would be the element with the greatest prognostic value versus pre-transplant response. This coincides with what was reported by the Spanish group [Citation31] where the pre-transplant response did not achieve statistical significance, but a complete post-transplant response was achieved. When analyzing the survival data, a difference is seen with greater follow-up than that in our series. This fact is important because the public system in Chile limits the indication for transplantation to those patients with VGPR or complete response and excludes patients with a partial response who could similarly benefit. The prognostic importance of MRD should be highlighted, becoming the main marker of post-ASCT progression, in accordance with what has been reported in other groups [Citation32]

The weaknesses of our study are mainly framed in that being a reference center, short follow up, and we have a significant percentage of patients who receive induction in other centers and who continue their post-transplant controls in their reference centers. In addition, 12% of patients are transplanted in relapsed disease, which makes comparison with other studies difficult. In addition, the registration of maintenance and its duration is ongoing. No formal comparison was made between VCD and VRD induction because patients are referred to HSCT thus achieving at least a partial response; thus, the comparison would not really consider the degree of response to induction (excludes patients with stable or progressive disease).

Conclusions

ASCT is an effective strategy for prolonged progression-free survival with deeper responses. It is necessary for achieving cytogenetic stratification at the time of diagnosis. It can optimize maintenance therapy, which is a key element to consolidate the benefits of transplantation. It is also necessary to include candidate patients with partial response within the national protocols. Public–private collaboration is a crucial element in reducing the gaps in access to this type of complex but highly effective therapy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

María Carolina Guerra

María Carolina Guerra, MD. Medicine graduate from the University of Chile. Specialist in Internal Medicine and Hematology from the University of Chile. She currently works as a Chief of Bone Marrow Transplant Department at the Arturo López Pérez Foundation.

Joaquín Jerez

Joaquín Jerez, MD. Medicine graduate from the Catholic University of Chile. Specialist in Internal Medicine from the Catholic University of Chile. He currently works as a Hematology resident at the Universidad de Los Andes/Arturo López Pérez Foundation. With special interest in acute leukemia and myeloma, cell therapies and genetic studies.

Giselle Godoy

Giselle Godoy, RN. Specialist in adult oncology nursing from Andrés Bello university, diplomate in epidemiology and health research, member of the Chilean society of oncological nursing, works as a nurse of the hematopoietic progenitor transplant program Arturo López Pérez Foundation.

José Luis Briones

José Luis Briones, MD. Medicine graduate from Universidad de Chile. Specialist in Internal Medicine from the Universidad de Chile. Sub-specialty of Hematology of the University of Chile. He currently works as head of the transfusion medicine unit of the Arturo López Pérez Foundation. With special interest in integrated hematology diagnosis, cellular therapy and apheresis.

Carlos Torres

Carlos Torres, MD. Medicine graduate from the University of Vapparaiso. Specialist in Internal Medicine from University of Valparaiso and Hematology from the University of Chile. He currently works as Hematologist Staff with special interest in lymphomas and myeloma.

Sebastián Hidalgo

Sebastián Hidalgo, MD. Medicine graduate from Universidad de Chile. Specialist in Internal Medicine from the Universidad de Chile. Sub-specialty of Hematology of the University of Chile. He currently works as Hematologist Staff of the Arturo López Pérez Foundation. With special interest in lymphomas and myeloma.

Valentina Goldschmidt

Valentina Goldschmidt, MD. Medicine graduate from Universidad de Chile. Specialist in Internal Medicine at the Universidad del Desarrollo. Sub-specialty of Hematology at El Salvador Hospital. He currently works as Hematologist Staff at Fundación Arturo López Pérez and Hospital Padre Hurtado. With special interest in acute leukemia and myeloma.

Raimundo Gazitúa

Raimundo Gazitúa, MD. Medicine graduate from Universidad de Chile. Specialist in Internal Medicine from the Universidad de Chile. Sub-specialty of Hematology of the Universidad de Chile. He currently serves as head of the Hematology department at the Fundación Arturo López Pérez and head of the Hematology training program at Universidad de los Andes. With special interest in lymphomas and myeloma, and teaching.

References

- Goel U, Usmani S, Kumar S. Current approaches to management of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Am J Hematol. 2022;97(Suppl 1):S3–S25.

- Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2020 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(5):548–567.

- Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Terpos E, et al. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(3):309–322.

- Mikhael JR, Dingli D, Roy V, et al. Management of newly diagnosed symptomatic multiple myeloma: updated mayo stratification of myeloma and risk-adapted therapy (mSMART) consensus guidelines 2013. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(4):360–376.

- Guía prácticas clínicas para diagnóstico y tratamiento del Mieloma Múltiple. Sociedad Chilena de Hematología año; 2019.

- Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Hulin C, et al. Lenalidomide, Bortezomib, and dexamethasone with transplantation for myeloma. NEJM. 2017;376(14):1311–1320.

- Rosiñol L, Oriol A, Teruel AI, et al. Superiority of bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (VTD) as induction pretransplantation therapy in multiple myeloma: a randomized phase 3 PETHEMA/GEM study. Blood. 2012;120(8):1589–1596.

- Moreau P, Avet-Loiseau H, Facon T, et al. Bortezomib plus dexamethasone versus reduced-dose bortezomib, thalidomide plus dexamethasone as induction treatment before autologous stem cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2011;118(22):5752–5758.

- Moreau P, Attal M, Hulin C, et al. Bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without daratumumab before and after autologous stem-cell transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (CASSIOPEIA): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):29–38.

- Voorhees PM, Kaufman JL, Laubach J, et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for transplant-eligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: the GRIFFIN trial. Blood. 2020;136(8):936–945.

- Peña C, Rojas C, Rojas H, et al. Mieloma múltiple en Chile: pasado, presente y futuro del programa nacional de drogas antineoplásicas (PANDA). Rev Med Chile. 2018;146(7):869–875.

- Sarmiento M, Lira P, Ocqueteau M, et al. Experiencia de 22 años de trasplante autólogo de células hematopoyéticas en pacientes con mieloma múltiple o amiloidosis sistémica. 1992- 2014. Rev Med Chile. 2014;142:1497–1501.

- Puga B, Molina J, Andrade A, et al. Primeros diez trasplantes autólogos de progenitores hematopoyéticos en adultos, en el servicio público de salud en Chile. Rev Med Chile. 2012;140(9):1207–1212.

- Peña C, Rojas-Vallejos J, Espinoza M, et al. Mieloma múltiple en Chile: Respuesta a tratamiento en pacientes con mieloma múltiple elegibles para trasplante autólogo de progenitores hematopoyéticos. Rev Med Chile. 2019 Dec;147(12):1561–1568.

- Kumar S, Paiva B, Anderson KC, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):e328–e346.

- Harousseau JL, Attal M, Avet-Loiseau H, et al. Bortezomib plus dexamethasone is superior to vincristine plus doxorubicin plus dexamethasone as induction treatment prior to autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of the IFM 2005-01 phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(30):4621–4629.

- Rosiñol L, Oriol A, Teruel AI, et al. Superiority of bortezomib, thalido- mide, and dexamethasone (VTD) as induction pretransplantation therapy in multiple myeloma: a randomized phase 3 PETHEMA/GEM study. Blood. 2012;120(8):1589–1596.

- Moreau P, Hulin C, Macro M, et al. VTD is superior to VCD prior to intensive therapy in multiple myeloma: results of the prospective IFM2013-04 trial. Blood. 2016;127(21):2569–2574.

- Sidana S, Kumar S, Fraser R, et al. Impact of induction therapy with VRD versus VCD on outcomes in patients with multiple myeloma in partial response or better undergoing upfront autologous stem cell transplantation. Transplant Cell Ther. 2022;28(2):83.e1–83.e9.

- Afrough A, Pasvolsky O, Ma J, et al. Impact of induction with VCD versus VRD on the outcome of patients with multiple myeloma after an autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transplant Cell Ther. 2022;28(6):307.e1–307.e8.

- Cornell RF, D'Souza A, Kassim AA, et al. Maintenance versus induction therapy choice on outcomes after autologous transplantation for multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(2):269–277.

- Stadtmauer EA, Pasquini MC, Blackwell B, et al. Autologous transplantation, consolidation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(7):589–597.

- Hari P, Pasquini MC, Stadtmauer EA, et al. Long-term follow-up of BMT CTN 0702 (STaMINA) of postautologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (autoHCT) strategies in the upfront treatment of multiple myeloma (MM). Oral abstract #8506. 2020 ASCO Annual Meeting; May 29–31, 2020.

- Richardson PG, Jacobus SJ, Weller EA, et al. Triplet therapy, transplantation, and maintenance until progression in myeloma. NEJM. 2022;387(2):132–147.

- Jones JR, Cairns DA, Gregory WM, et al. Second malignancies in the context of lenalidomide treatment: an analysis of 2732 myeloma patients enrolled to the Myeloma XI trial. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6(12):e506.

- Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Kumar SK, et al. Second primary malignancies with lenalidomide therapy for newly diagnosed myeloma: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(3):333–342.

- McCarthy PL, Holstein SA, Petrucci MT, et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(29):3279–3289.

- Palumbo A, Hajek R, Delforge M, et al. Continuous lenalidomide treatment for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. New Engl J Med. 2012;366:1759–1769.

- Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Marit G, et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. NEJM. 2012;366:1782–1791.

- McCarthy PL, Owzar K, Hofmeister CC, et al. Lenalidomide after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. NEJM. 2012;366:1770–1781.

- Lahuerta JJ, Mateos MV, Martínez-López J, et al. Influence of pre- and post-transplantation responses on outcome of patients with multiple myeloma: sequential improvement of response and achievement of complete response are associated with longer survival. J ClinOncol. 2008;26(35):5775–5782.

- Lahuerta JJ, Paiva B, Vidriales MB, et al. San-Miguel JF; GEM (Grupo Español de Mieloma)/PETHEMA (Programa para el Estudio de la Terapéutica en Hemopatías Malignas) cooperative study group. Depth of response in multiple myeloma: a pooled analysis of three PETHEMA/GEM clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(25):2900–2910.