ABSTRACT

Objective:

To analyze the number of HSCTs performed in 2019 vs. 2020 and report the status of transplant centers (TCs) during and a year after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

We performed a comprehensive cross-sectional nationwide study including active TCs interrogating HSCT activity from 2019 through September 2021. An electronic survey was sent to TCs and consisted of items regarding the number and characteristics of procedures performed and were compared yearly. Changes to their institutions’ transplant policies and practices during the COVID19 pandemic were also documented. Fifty centers were invited to participate, 33 responded.

Results:

Most TCs were part of the public health system (63.7%). Almost half are in the country’s capital, Mexico City (45.5%). Most centers performed <10 procedures per year. The number of HSCTs decreased from 835 in 2019–505 in 2020 (p < .001), representing a 40% reduction in transplant activity. The monthly transplant rate in 2021 increased to 58.3, compared to 42 in 2020 and close to 69.5 in 2019 (p < .001). All types of HSCTs decreased excluding haploidentical transplants. All institutions treated patients with COVID19, and over two-thirds experienced some form of hospital reconversion. Transplant activity stopped completely in 23 TCs (70%) during the pandemic with a median closure duration of 9.9 months (range, 1-21). In 2021, 9.1% of TCs remained closed, all of them in the public setting.

Conclusion(s):

The limited transplant activity in Mexico decreased significantly during the pandemic but is recovering and nearly in pre-pandemic levels.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is an effective treatment for many patients with hematopoietic disorders [Citation1]. HSCT is a complex and costly procedure that impacts health systems and patients’ socioeconomic well-being. It requires highly trained, qualified staff with access to the appropriate equipment and infrastructure [Citation2,Citation3]. Consequently, access to HSCT in low – and middle-income countries (LMICs) is limited and significantly reduced compared to high-income countries (HICs) where most HSCTs are performed, despite a lower disease burden [Citation3].

Because COVID-19 posed a significant risk to immunocompromised patients, such as those undergoing HSCT, it became a challenge to members of the HSCT community who must deal with the prevention of nosocomial transmission, the protection of staff, treatment of COVID-19 in HSCT recipients, as well as hospital staff repurposing and relocation [Citation4]. Some centers have shared their experiences regarding the impact of COVID19 on HSCT. Stem cell donor collections decreased in centers throughout the world, and decisions regarding performing HSCT were affected by the availability of blood products, access to financing, and bureaucratic difficulties due to the closure of government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and corporate social responsibility liaisons [Citation5,Citation6]. On the other hand, some centers in HICs never stopped performing HSCT and were able to overcome these barriers [Citation7]. There is a lack of data from LMICs that are currently limited to single-center experiences [Citation6,Citation8]. In Mexico, the impact of the COVID19 pandemic on HSCT has not been described as there is no active Mexican transplant registry. This study aims to analyze the number of HSCTs performed in 2019 vs. 2020 and report the status of transplant centers (TCs) during and a year after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional study was performed by members of the Mexican Transplantation and Cellular Therapy working group (TCTMX) that collaborate with both national transplant societies, Sociedad Mexicana de Terapia Celular y Trasplante de Médula Ósea and the Sociedad Mexicana de TCP en Pediatría y Terapia Celular. The study was approved by a central Institutional Review Board and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Centers that reported any transplant activity to the World Bone Marrow Donor Transplantation Registry in 2018 received an invitation to participate. Centers that did not report to WBMT but had transplant activity known by both adult and pediatric societies were also invited. Fifty centers were listed, and all were invited to report their data. Those who agreed received a single electronic survey with questions regarding transplantation activity from January 2019 through September 2021 (Supplemental appendix 1). This survey was sent from October 2021 through December 2021 with a 3-month window for completion and four electronic reminders.

The TCTMX working group members designed the survey, consisting of 65 items corresponding to TC data. It included the number of HSCTs done during 2019 (pre-pandemic), the number of HSCTs performed during the pandemic, and modifications in their transplant program. The number of transplants performed in 2019 were compared to later timeframes in reporting centers to reflect the impact of the COVID19 pandemic on our national activity, and it was our primary outcome. Secondary outcomes included modifications established at TCs due to the pandemic: number of centers that stopped HSCT activities and, the duration, and the motives that drove these modifications.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are summarized in measures of central tendency and dispersion, and qualitative variables in frequencies and percentages. The Mann – Whitney U test was used to compare quantitative variables. Associations in qualitative variables were tested using Pearson's chi-squared. Responses from all questionnaires were registered in a Microsoft Excel version 16.6 database and analyzed using the SPSS statistical package, version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk NY).

Results

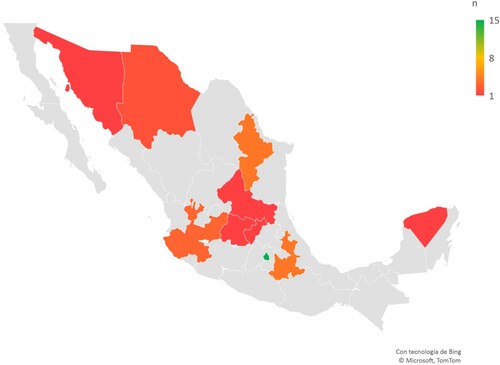

From the 50 TC invited, 33 completed the survey (66%). Most TCs that answered the survey were part of the public health system which is fully or partially government-funded (63.7%). Almost half were in the country's capital, Mexico City (45.5%) (, Supplemental Table 1). Almost half of the centers treat pediatric and adult populations, while the other half exclusively treat adult or pediatric populations. Most centers in the country performed <10 procedures per year, and only a handful performed >30 procedures a year ().

Figure 1. Heatmap of Mexico highlighting states with hematopoietic cell transplant centers active in 2019–2021

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 33 centers that perform autologous or allogeneic transplantation in Mexico from 2019 to 2021.

The number of HSCTs decreased from 835 in 2019–505 in 2020 (p < .001), representing a 40% reduction in transplant activity (). In 2019, only a single center performed no transplants. The number of centers without HSCTs increased to 9 in 2020 (27%) and again decreased to 5 in 2021 (15%). The monthly country-wide transplant rate in 2021 increased to 58.3, with 525 HSCTs performed compared to 42 in 2020 and close to 69.5 in 2019 (p < .001). All types of HSCTs decreased with the notable exception of haploidentical transplants after adjusting for the monthly transplant rate, and by 2021, they even surpassed the number of MSD grafts (Supplemental Figure 1 and Supplemental Figure 2). On the other hand, a total of 26 matched unrelated donor transplants (MUD) and four umbilical cord blood (UCB) grafts were performed during the entire 3-year period.

Table 2. Transplants performed in Mexico in the pre-pandemic and post-COVID19 (2019-2021) periods.

Changes during the COVID19 pandemic

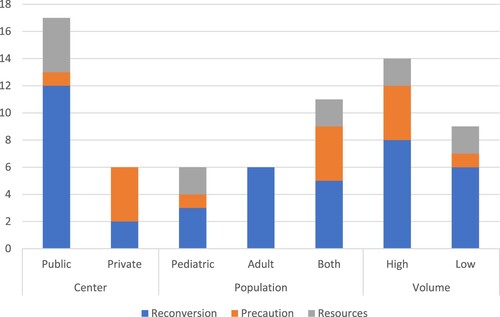

All institutions treated patients with COVID19, and over two-thirds experienced some form of hospital reconversion, with 1 in 4 TCs directly affected (). Hospitals with low-volume HSCTs had more frequent hospital reconversions than those with a higher (92.3 vs. 55%; p = .05), regardless of patient population treated and whether they were public or private centers. HSCT activity stopped completely in 23 TCs (70%) during the pandemic with a median closure duration of 9.9 months (range, 1-21). This finding was similar regarding pediatric and adult populations (Supplemental Table 2) but higher in public vs. private centers (median of 12.9 vs. 6 months; p = .01) and with a trend towards low vs. high volume centers (median of 15.5 vs. 6.1 months; p = .08) (Supplemental Table 3). In 2021, 9.1% of TCs remained closed, all of them from the public sector.

Table 3. Changes to transplant center practices in Mexico during the COVID19 pandemic.

The most frequent reason cited by TCs for closure was hospital reconversion, followed by precautionary measures, and a lack of resources (). Public centers cited hospital reconversion more frequently regardless of the population treated or center volume.

Staff relocation was very common, with nurses being the healthcare professionals more frequently assigned to COVID19 patient care, particularly in low-volume centers (100% vs. 65%). They were followed by fellows (more frequently in public institutions), administrative staff, including social workers, and attending physicians ().

Follow-up outpatient visits were totally or partially suspended in 9.1% and 36.4% of TCs, respectively. They were modified in 63.6%, most frequently by telemedicine using video calls in public and private institutions and low and high-volume centers (). Reported modifications in conditioning regimens, immunosuppression, or maintenance strategies specifically due to the pandemic were infrequent (9.1%, 12.1%, and 9.1%, respectively). Most centers continued to treat COVID19 patients at the time of the survey (86.7%).

Discussion

Access to HSCT in LMICs around the world has been limited due to a range of barriers which include patient-centered factors, such as demographics, socioeconomic status, insurance and healthcare coverage, and health system-related factors such as transplant team density, donor availability, funding, costs, infrastructure, training, and education [Citation1,Citation9]. Mexico is a Latin-American country considered an upper-middle-income economy with low numbers of HSCTs compared to other similar countries, such as Argentina and Brazil [Citation10]. Over half of Mexican states do not have a TC. Most TCs have low transplant rates, with 64% of centers performing less than 10 procedures a year and only 36% performing >10 allogeneic grafts; a finding considered the minimum for FACT-JACIE accreditation [Citation11]. This fragile system was greatly challenged by the COVID19 pandemic, as Mexico became one of the countries with the highest incidence and SARS-CoV-2-related deaths worldwide [Citation12]. Our data showed that almost 70% of TCs had to stop all new transplant activity during 2020 (69.7%) for a median of 10 months. Almost 70% of hospitals with a transplant team experienced some form of reconversion to a COVID19 treatment facility, particularly in low-volume centers (), with 1 in 4 HSCT units being retrofitted to care for COVID19 patients. This situation was particularly worse for government-funded institutions that carried most of the pandemic burden (), leading to a country-wide decrease in transplant rates and a drop of 40% compared to the prior year, likely resulting in harm to patients in need of HSCT.

Figure 2. Reasons for transplant activity suspension in Mexico across transplant center types during the COVID19 pandemic.

According to a recent EBMT survey, transplant rates constantly increased from the 1990s until 2020, when, for the first time in 31 years, a 6.1% drop was reported. This finding is considerably less compared to our experience [Citation13]. A single-center study in the United States reported that the decrease in transplantation resulted from a precautionary measure and not hospital reconversion, with HSCTs still available for high-risk patients, mirroring private care facilities in Mexico, where this was also the case [Citation14]. In contrast, in a single center in India, access to HSCT was compromised by a shortage of resources, including funding and financial support. They relied on governmental and non-governmental organizations and access to blood products due to a decrease in volunteer donors [Citation15]. These broad differences can be explained by the varying impact of the pandemic on healthcare delivery across global regions and healthcare systems, the fact that most EBMT and North American centers are in HICs with established HSCT infrastructure, and that the COVID19 response was able to adapt to the rising limitations [Citation13].

International alternative donor transplantation was limited since the borders closed in European countries [Citation16]. A study aiming to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on allo-HSCT activity in Italy showed an overall reduction of 2.4% from 2019 to 2020, a 3.7% increase in MSD, and a decrease of 0.9% and 8.6% in MUD and haplos, respectively, with no change in UCB [Citation17]. In our context, experience with alternative donor transplantation is very limited, with 26 MUD transplants in the entire 3-year period, only 4 UCB performed in 2019, and none in the following years. This ongoing issue is due to the lack of a large publicly-funded Mexican donor registry, high costs, administrative challenges, and a lack of reimbursement of international donations. Remarkably, although small, the rate of MUD transplantation increased despite the pandemic by more than 300%, which may be a reflection of an established extension of the US National Marrow Donor Program, Be the Match®, in our country. A program that has recruited thousands of Mexican donors since 2017 and provides stipends for patients to partially cover the costs of donor procurement [Citation18]. A notable exception in the reduction of alternative donors was haploidentical grafts, which increased despite the pandemic, more than tripling MSD grafts in 2021 and doubling the 2019 haploidentical transplant-per-month rate (Supplementary Figure 2). This phenomenon goes in parallel with the overall trend observed in other Latin-American countries and LMICs [Citation10], where post-transplant cyclophosphamide has had a disruptive impact, allowing transplants despite the lack of available MSD and limited access to MUDs.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused great changes to transplant programs and patients undergoing HSCT. Ensuring high-quality care became a challenge. TCs had to adapt to protect patients and staff from infection and deal with a shortage of beds and personnel [Citation19]. This situation also occurred in Mexico, where staff relocation was a necessary adjustment for 100% of TCs. More frequently, nurses were relocated with a higher impact to low-volume centers (Supplemental Table 3). Fellows and attendings were also redistributed to provide aid, contrasting with a similar study reported in Italy, where only 23.1% TCs were required to relocate healthcare providers [Citation16]. Fellow redistribution was significantly higher in public than private centers (66.7% vs. 25% respectively; p = .032), placing physicians in training, especially from public centers, at a disadvantage, hindering their learning. COVID-19 impacted residents’ and fellows’ training worldwide, and hematology and HSCT fields are not exceptions [Citation20].

As TCs had to devise new ways to deliver care, video calls were implemented in 21 centers (63.6%). Although this alternative was used by all TCs that treat adults, it was less frequently seen in TCs that treat children or both populations (p = .01). The reason for this difference is not clear. The use of videoconferencing and telephone-based services in hematology patients has been well received by both adult and pediatric patients providing care similar to face-to-face consults [Citation21].

Transplant rates improved in 2021 and were near pre-pandemic levels, although at the time of the survey, 33% of low-volume centers had yet to be reactivated. Moving forward, we should develop strategies that focus on the continuation of care that could be deployed in a public health emergency that includes all stakeholders. Preserving and protecting transplant programs during future emergencies preparation is key. FACT-JACIE recommends the quality management plan in each center include an emergency action plan, evaluation of risks with annual audits, besides providing controlled access to facilities and necessary equipment and materials [Citation23]. International transplant societies have provided their own recommendations, and ideally, we should employ strategies adapted to our reality that include advocacy efforts with the institutional, local and national authorities for the preservation of resources to allow for continued care delivery [Citation4, Citation22]. Furthermore, outpatient transplantation is a strategy developed in Mexico successfully by two of the high-volume centers, one of which reported an increase in transplantation rate in 2020, including autologous and allogeneic grafts [Citation8].

Limitations of this study include its cross-sectional nature and lack of detailed patient-level data, including outcomes that were omitted to improve our survey reporting rate. More research needs to be done to quantify further the effect of the pandemic on patients that needed HSCT and the impact on their outcomes and treatment alternatives. Furthermore, drug shortages and lack of resources have occurred nationally since 2020 and are ongoing, encompassing the study period. This fact may have affected the TCs’ capacity to deliver care at the same time as the pandemic [Citation24]. Strengths include a comprehensive search and center contact strategy, a successful reporting rate surpassing WBMT historical data of 17 centers in 2018 and becoming de facto the largest study ever performed in HSCT centers in Mexican history.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic severely limited transplant activity in Mexico compared to what has been reported in high-income countries, but it is recovering and is nearly at pre-pandemic levels. Most TCs were affected with a higher impact on government-funded and low-volume centers, reflecting the fragility of our transplant infrastructure and the healthcare system overall.

Author contributions

AGL and LGF wrote the manuscript and analysed the data. AGL, PCP, CB, CVS, MACM, AOV, MPG, XGL, MAHR, MSG designed the research. SLR, ACRZ, ASA, GJRA, and DGA provided feedback and wrote the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (32.5 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank the investigators of the Mexican Transplantation and Cellular Therapy working group for completing the survey in the largest collaborative study in our country’s history: Severiano Baltazar-Arellano, Guadalupe González-Villarreal (Unidad Médica de Alta Especialidad No. 25 Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social [IMSS], Monterrey) Luis Valero-Saldaña (Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, Mexico City), Maria M. Contreras-Serratos (Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI, IMSS, Mexico City), Iván Castorena-Villa (Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez, Mexico City), Lourdes Vega-Vega (Hospital Infantil Teletón Oncología, Querétaro), Marta Alvarado-Ibarra (Centro Médico Nacional 20 de Noviembre, Mexico City), Uendy Pérez-Lozano (Centro Médico Nacional Manuel Ávila Camacho, Puebla), Angel García-Soto (Centro Médico Nacional La Raza IMSS, Puebla), Adrian Morales-Maravilla (Hospital Ángeles, Puebla), Gabriela Cardoso-Yah (Hospital Central Militar, Mexico City), Lauro Fabian Amador-Medina (Hospital Regional de Alta Especialidad del Bajío, León), Sergio Inclán-Alarcón (Centro Médico ABC Observatorio, Mexico City), Diego Cruz-Contreras (Doctors Hospital, Monterrey), Carlos Chavez-Trillo (Hospital Ángeles Chihuahua, Hospital Central Universitario, Chihuahua), Juan Antonio Flores-Jiménez (Hospital Puerta de Hierro Sur, Guadalajara), Cynthia S. Cruz-Medina (Hospital para el Niño Poblano, Puebla), Roberto Ovilla-Martínez (Hospital Ángeles Lomas, Mexico City), Enrique Gómez-Morales (Centro Médico Naval, Mexico City), JA Badell-Luzardo (Centro Médico del Noroeste, Hermosillo), Gilberto I. Barranco-Lampón (Hospital Ángeles Acoxpa, Mexico City), Regina M. Navarro-Martin del Campo, Oscar González-Ramella (Hospital Civil de Guadalajara Dr. Juan I. Menchaca, Guadalajara), María de L. Gutiérrez-Rivera (Hospital de Pediatría Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI, Mexico City), Adrian Ceballos-López (Clínica de Mérida, Mérida), A Milán-Salvatierra (Hospital Juárez de México, Mexico City).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Financial disclosure statement

AGL received honoraria from AbbVie, BMS and serves on Advisory board for AbbVie, BMS. DGA received honoraria from Janssen, Roche and serves on Advisory board for Janssen, Roche, TEVA, BMS, Pfizer, Amgen, Takeda, Novartis, Abbvie, Aztra Zeneca. AOV serves on Advisory board for Takeda, AMGEN, MSD.

Data availability

All data generated during this study are included in this article and its supplementary files.

References

- Leon Rodriguez E, Rivera Franco MM. Outcomes of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation at a limited-resource center in Mexico Are comparable to those in developed countries. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(11):1998–2003. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.07.010.

- Saito AM, Cutler C, Zahrieh D, et al. Costs of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with high-dose regimens. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(2):197–207. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.10.010.

- Barr RD. The importance of lowering the costs of stem cell transplantation in developing countries. Int J Hematol 2002;76(1):365–367. doi:10.1007/BF03165286

- Mahmoudjafari Z, Alexander M, Roddy J, et al. American society for transplantation and cellular therapy pharmacy special interest group position statement on pharmacy practice management and clinical management for COVID-19 in hematopoietic cell transplantation and cellular therapy patients in the United States. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26(6):1043–1049. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.04.005.

- Radhakrishnan VS, Nair R, Goel G, et al. COVID-19 and haematology services in a cancer centre from a middle-income country: adapting service delivery, balancing the known and unknown during the pandemic. Ecancermedicalscience. 2020;14:1110. doi:10.3332/ecancer.2020.1110.

- Mengling T, Rall G, Bernas SN, et al. Stem cell donor registry activities during the COVID-19 pandemic: a field report by DKMS. Bone Marrow Transplant 2021;56(4):798–806. doi:10.1038/s41409-020-01138-0.

- Del Campo L, Ramírez López P, de la Cruz Benito A, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation during COVID-19 pandemic: experience from a tertiary hospital in Madrid. Expert Rev Hematol. 2021;14(1):1–5.

- Colunga-Pedraza PR, Colunga-Pedraza JE, Meléndez-Flores JD, et al. Outpatient transplantation in the COVID-19 era: a single-center latin American experience. Bone Marrow Transplant 2021: 1–4. doi:10.1038/s41409-021-01360-4.

- Rocha V, Fatobene G, Niederwieser D. & Increasing access to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant: an international perspective, Increasing access to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant: an international perspective. Hematology. 2021;2021:264–274. doi:10.1182/hematology.2021000258.

- Correa C, Gonzalez-Ramella O, Baldomero H, et al. Increasing access to hematopoietic cell transplantation in Latin America: results of the 2018 LABMT activity survey and trends since 2012 (2022). Bone Marrow transplant. 2018 LABMT activity survey and trends since 2012. Bone Marrow Transplant. Advance online publication. doi:10.1038/s41409-022-01630-9

- European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. (2021). FACT-JACIE International Standards for Hematopoietic Cellular Therapy Product Collection, Processing, and Administration. Eight edition 8.1. https://www.ebmt.org/8th-edition-fact-jacie-standards.

- Ibarra-Nava I, la Garza C-d, Ruiz-Lozano JA, et al. Mexico and the COVID-19 response. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020;14(4):e17–e18. doi:10.1017/dmp.2020.260.

- Passweg JR, Baldomero H, Chabannon C, et al. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on hematopoietic cell transplantation and cellular therapies in Europe 2020: a report from the EBMT activity survey (2022). Bone Marrow transplant.−57 pandemic on hematopoietic cell transplantation and cellular therapies in Europe 2020: a report from the EBMT activity survey. Bone Marrow Transplant; 57(5):742–752. doi:10.1038/s41409-022-01604-x.

- Maurer K, Saucier A, Kim HT, et al. COVID-19 and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immune effector cell therapy: a US cancer center experience. Blood Advances. 2021;5(3):861–871. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003883.

- Radhakrishnan VS, Nair R, Goel G, et al. COVID-19 and haematology services in a cancer centre from a middle-income country: adapting service delivery, balancing the known and unknown during the pandemic. Ecancermedicalscience. 2020;14:1110. doi:10.3332/ecancer.2020.1110.

- Doná D, Torres Canizales J, Benetti E, ERN TransplantChild et al. Pediatric transplantation in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic: early impact on activity and healthcare. Clin Transplant. 2020;34(10):e14063. doi:10.1111/ctr.14063.

- Russo D, Polverelli N, Malagola M, GITMO Centers et al. Changes in stem cell transplant activity and procedures during SARS-CoV2 pandemic in Italy: an Italian bone marrow transplant group (GITMO) nationwide analysis (TransCOVID-19 survey). Bone Marrow Transplant 2021;56(9):2272–2275. doi:10.1038/s41409-021-01287-w.

- Be the Match Mexico. https://bethematch.org.mx. Accessed: May 03, 2022.

- Vasquez L, Sampor C, Villanueva G, et al. Early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on paediatric cancer care in Latin America. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):753–755. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30280-1.

- Enujioke SC, McBrayer K, Soe KC, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on post graduate medical education and training. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):580. doi:10.1186/s12909-021-03019-6.

- Shah AC, O'Dwyer LC, Badawy SM. Telemedicine in malignant and nonmalignant hematology: systematic review of pediatric and adult studies. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021 Jul;9(7):e29619. doi:10.2196/29619. PMID: 34255706; PMCID: PMC8299344.

- Ljungman P, Mikulska M, de la Camara R, et al. The challenge of COVID-19 and hematopoietic cell transplantation; EBMT recommendations for management of hematopoietic cell transplant recipients, their donors, and patients undergoing CAR T-cell therapy. Bone Marrow transplant.−55 and hematopoietic cell transplantation; EBMT recommendations for management of hematopoietic cell transplant recipients, their donors, and patients undergoing CAR T-cell therapy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55(11):2071–2076. doi:10.1038/s41409-020-0919-0.

- FOUNDATION FOR THE ACCREDITATION OF CELLULAR THERAPY, JOINT ACCREDITATION COMMITTEE ISCT and EBMT (JACIE). FACT-JACIE International Standards for HEMATOPOIETIC CELLULAR THERAPY Product Collection, Processing, and Administration [Internet]. 2021 dic. Available at: https://www.ebmt.org/8th-edition-fact-jacie-standards

- Das M. Shortage of cancer drugs in Mexico. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(9):1216), doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00452-6.