ABSTRACT

Interventions to minimise, reverse or prevent the progression of frailty in older adults represent a potentially viable route to improving quality of life and care needs in older adults. Intervention methods used across European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing collaborators were analysed, along with findings from literature reviews to determine ‘what works for whom in what circumstances’. A realist review of FOCUS study literature reviews, ‘real-world’ studies and grey literature was conducted according to RAMESES (Realist and Meta-narrative Evidence Synthesis: Evolving Standards), and used to populate a framework analysis of theories of why frailty interventions worked, and theories of why frailty interventions did not work. Factors were distilled into mechanisms deriving from theories of causes of frailty, management of frailty and those based on the intervention process. We found that studies based on resolution of a deficiency in an older adult were only successful when there was indeed a deficiency. Client-centred interventions worked well when they had a theoretical grounding in health psychology and offered choice over intervention elements. Healthcare organisational interventions were found to have an impact on success when they were sufficiently different from usual care. Compelling evidence for the reduction of frailty came from physical exercise, or multicomponent (exercise, cognitive, nutrition, social) interventions in group settings. The group context appears to improve participants’ commitment and adherence to the programme. Suggested mechanisms included commitment to co-participants, enjoyment and social interaction. In conclusion, initial frailty levels, presence or absence of specific deficits, and full person and organisational contexts should be included as components of intervention design. Strategies to enhance social and psychological aspects should be included even in physically focused interventions.

Frailty can be viewed as a dynamic clinical syndrome, transitioning from robustness through a ‘pre-frail’ condition to a ‘frail’ outcome (Ferrucci et al., Citation2004). It is associated with advancing age and characterised by decreased psychological and physiological resilience, and an increased risk of poor clinical outcomes such as disability, dementia and falls (Hazzard, Bierman, Blass, Ettinger, & Halter, Citation1999), hospitalisation, institutionalisation and mortality (Clegg, Young, Iliffe, Rikkert, & Rockwood, Citation2013). Estimates suggest that between 4% and 17% of the population aged over 65 years are affected (Collard, Boter, Schoevers, & Voshaar, Citation2012). Frail older adults are high users of informal and formal care and healthcare services (Young, Citation2003), and innovation in methods of managing functional decline and frailty are critical in balancing the needs of older adults with limited healthcare resources (Rechel et al., Citation2013).

Frailty is generally conceptualised using two main theoretical constructs, the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) phenotype, also known as Fried’s phenotype (Fried et al., Citation2001; Fried, Ferrucci, Darer, Williamson, & Anderson, Citation2004), and the Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CSHA) cumulative deficit model, known as Rockwood’s frailty index (Rockwood & Mitnitski, Citation2007). Fried’s phenotype (Fried et al., Citation2001, Citation2004) describes frailty as a biological syndrome resulting from deficits in five physiological domains: global weakness, overall slowness, exhaustion, low physical activity and unintentional weight loss. A ‘pre-frail’ state is indicated by two of these symptoms, with three or more indicating a ‘frail’ state. Rockwood’s index (Rockwood & Mitnitski, Citation2007) measures frailty as a risk state in terms of the number of health ‘deficits’ manifest in the individual. This model incorporates physical functioning but also polypharmacy, cognitive impairments, psychosocial risk factors and geriatric syndromes (e.g., falls, delirium and urinary incontinence). The cumulative deficit approach acknowledges that frailty is not solely a biological state, but is a multi-dimensional concept (Rodríguez-Mañas et al., Citation2013; Walston et al., Citation2006) encompassing co-morbidity and disability as well as cognitive, psychological and social elements (Langlois et al., Citation2012; Rodríguez-Mañas et al., Citation2013).

Although frailty is associated with ageing, it is not inevitable. Research suggests that when frailty is identified early, it can be reversed, managed and its progression prevented through intervention (Cameron et al., Citation2013; Gill et al., Citation2002; Ng et al., Citation2015; Theou et al., Citation2011). Although interventions may be most effective within a pre-frail ‘intervention window’ (Topinková, Citation2008), positive effects have also been noted in frail populations (Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2010). A heterogeneous range of interventions to minimise, reverse or prevent the progression of frailty have been reported, including components such as geriatric evaluation and management (GEM) and personalised care, as well as nutrition and exercise (Theou et al., Citation2011).

Throughout this paper, we use the term ‘frailty interventions’ and define that as any intervention designed to minimise, reverse or prevent the progression of pre-frailty or frailty in older adults. Such interventions might include, but are not limited to, physical activity, cognitive training, multi-factorial intervention, psychosocial intervention, health and social care provision, nutritional supplementation, or medication/medical maintenance adherence focused interventions. Critically, the primary outcome of interest should be frailty, indicated by a validated scale, measurement or index (for example, a frailty index or phenotype model); or a limited set of clinically important indicators, defined in advance and included as an operational definition by authors, such as impairment in activities of daily living (ADLs), low physical activity, low mobility with poor nutrition. This is in contrast with interventions for frail older people, where frailty is an inclusion criterion but not specifically addressed or measured post-intervention.

Interventions have been implemented in different countries, in a range of healthcare organisational contexts, and with participants with different health conditions and from different cultural and educational backgrounds. The difficulty, however, is that knowing that frailty interventions work in certain populations or settings may not be sufficient to ensure their success if they were to be more widely adopted.

To produce recommendations to support future intervention development, we performed a realist review. The review was based on findings from literature reviews and other studies conducted as part of a larger study on frailty, FOCUS (Frailty Management Optimisation through EIP-AHA Commitments and Utilisation of Stakeholders Input), funded by the European Union’s Health Programme (2014–2020). This EU funded multi-disciplinary research collaboration has the aim of reducing the burden of frailty in Europe by developing methods and tools to assist in the early diagnoses, screening and management of frailty. FOCUS studies providing the theoretical framework for this review include: a systematic review of the effectiveness of frailty interventions (Apóstolo et al., Citation2018); a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies on stakeholders’ views and experiences of frailty care and interventions (D’Avanzo et al., Citation2017); a qualitative analysis of stakeholders’ views on frailty (Shaw et al., Citation2017); and a survey of European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing (EIP-AHA) partners’ frailty interventions (Gwyther et al., Citation2017). The ultimate aim of this realist review was to contribute to the final FOCUS project guidelines to inform decision-making and implementation of best practices for frailty management.

EIP-AHA is a multi-stakeholder collaboration launched by the European Commission in order to identify and remove barriers to innovation for active and healthy ageing. In 2013, the EIP-AHA portfolio (European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing, Citation2013) identified 98 ‘good practices’ involved in research to reverse or prevent frailty, many of which have now published outcomes of their projects in a variety of formats, but most commonly in peer-reviewed journals.

Realist review was chosen as the most appropriate method for synthesising and comparing the range of literature and outputs from the FOCUS project with the intervention methods used in practice by EIP-AHA partners. In brief, the realist review process (Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey, & Walshe, Citation2005) is a qualitative systematic review method whose goal is to identify and explain how, whether and why an intervention works and in what context (Pawson, Citation2006); that is, to identify and explain the relationships between context (C), mechanism (M) and outcome (O). These patterns predict which aspects of the intervention make it effective, and which are required to replicate that success across a range of contexts. It has been characterised as a theory-driven, evidence building and interpretative approach (Pawson, Citation2006).

For our study, the realist review method has several advantages. It is effective when dealing with the problems of complexity and heterogeneity, for example, in study design, study setting and context (Pawson et al., Citation2005), and so suitable for the range of frailty studies we are examining. Realist review recognises that interventions are complex and can rarely be delivered consistently due to differences in contextual variables, the organisational, socio-economic and cultural environment that cannot be fully controlled (Wong, Greenhalgh, Westhorp, & Pawson, Citation2012). Further, it supports the use of different types and multiple forms of evidence (Pawson, Citation2002; Pawson et al., Citation2005), with value placed on both quantitative and qualitative studies (Pawson et al., Citation2005), and grey literature that might otherwise be excluded from a traditional systematic review. This ensures that underlying theories and approaches are evaluated rather than simply focusing on specific measured outcomes.

The objective of our review was to (a) to identify and explain the mechanisms of success and failure of interventions designed to minimise, reverse or prevent the progression of frailty in various country, healthcare organisation or patient contexts, i.e., what works for whom and in what circumstances; and (b) to develop evidence-based recommendations to support future intervention design.

Method

This review followed guidelines outlined by the Realist and Meta-narrative Evidence Synthesis: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) project (Wong, Westhorp, Pawson, & Greenhalgh, Citation2013). In this review, we aim to extend and complement previous work done as part of the FOCUS project, to contribute to the final FOCUS project guidelines, and to assist with the development of best practices for frailty management. We begin by describing the process of evidence collection for this review and move on to our evidence synthesis and analytical strategies.

Evidence collection

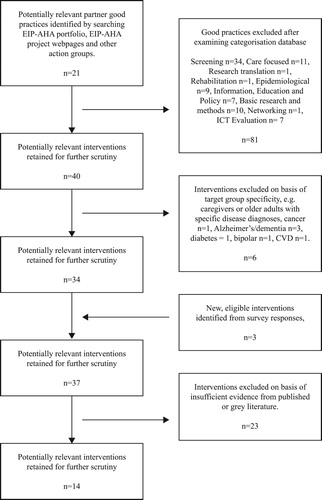

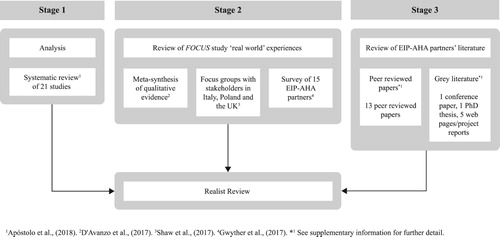

Evidence came from a range of sources, with a focus on previous work undertaken as part of the FOCUS project, and from a wider investigation of literature associated with the EIP-AHA partner good practices. The evidence collection process is detailed in .

Figure 1. An overview of the evidence collection stages of the realist review process for frailty screening and management interventions.

Stage 1: We analysed the 21 randomised controlled trials included in our FOCUS study systematic review (Apóstolo et al., Citation2018). The search and inclusion processes for this review have been previously described (Apóstolo et al., Citation2018) but a brief synopsis is included for completeness. The review examined interventions designed to prevent frailty progression where the primary outcome of interest was frailty (measured pre- and post-intervention). Secondary outcomes included but were not limited to cognition, quality of life, ADLs, self-perceived health and adverse outcomes. Participants were required to be 65 years and over, and explicitly identified as pre-frail or frail. Studies selecting for a specific illness or disease diagnosis were excluded. Quality control criteria were applied. Further details of these studies can be found in the supplementary information (Appendix 1).

Stage 2: We then examined the findings from ‘real-world’ experiences collected during our other FOCUS studies – the meta-synthesis (D’Avanzo et al., Citation2017); the qualitative analysis of stakeholders’ views on frailty (Shaw et al., Citation2017); and the survey of EIP-AHA partners (Gwyther et al., Citation2017). Evidence from these studies which supported or refuted findings from Stage 1 were noted.

Stage 3: Next, to strengthen the evidence base, we searched the literature for other outputs. Given the breadth and complexity of the subject area, we chose to limit the scope of the search to EIP-AHA partner good practices. This was in line with the aim of the FOCUS study to review EIP-AHA good practices and to extend the work done previously in the survey study. Although some partners had previously provided information in the form of survey responses (see Stage 2 and Gwyther et al., Citation2017), we hypothesised that additional evidence of causal patterns might be found in the literature associated with EIP-AHA good practices. Searching the literature also provided us with an opportunity to review all of the EIP-AHA good practice partners’ information rather than just that those who had responded to the survey. Given that many of the EIP-AHA projects were ongoing, and consequently unpublished in peer-reviewed journals, a range of sources of this evidence was considered. We were not restricted by methodological hierarchy (Wong et al., Citation2013).

Ninety-eight good practices were identified from the EIP-AHA portfolio (European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing, Citation2013) and 23 from a wider review of EIP-AHA good practices established after the publication of that portfolio. These good practices were reviewed for suitability based on eligibility. The main criterion was that studies should describe an intervention designed to reduce or prevent frailty, or one of its indicators. Suitable outcome measures included: primary measures of frailty status, i.e., frail/pre-frail/robust, or frailty index score; secondary outcomes of ADLs or reports of adverse personal outcomes such as transition of care and mortality; and indicators of frailty, for example, gait speed, weight loss, exhaustion, muscle/grip strength, low physical activity, physical performance, functional fitness, timed up and go (TUGT), bodily pain and self-reported health.

A first pass screening was undertaken based on the projects’ categorisation in the EIP-AHA portfolio. Non-intervention studies, for example, epidemiological studies, basic research or networking studies were excluded. Good practices were also excluded based on target group specificity, for example, they reported on projects only with caregivers, or for patients with specific, single disease diagnoses. Thirty-four potential good practices were retained. Next, the FOCUS survey responses were scrutinised and good practices which had not been listed in the original EIP-AHA portfolio were identified and included (N = 3).

At this stage, Google Scholar and Web of Science were searched for primary evidence related to the good practices, including peer-reviewed papers. Search terms included variations in the project name or published acronym, and where known the Principal Investigator’s name or primary contact as detailed in the EIP-AHA portfolio (European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing, Citation2013) or FOCUS survey response. ‘Grey literature’ were also interrogated using the Google search engine and the same search terms. We examined project-specific websites and reports, as well as unpublished theses. Given that many of the EIP-AHA projects were ongoing, preliminary results and results written for a lay audience, sometimes without statistical support, were deemed acceptable. Data was used if it was relevant, that is, it contributed usefully to an aspect of theory development, and, if the methods used to generate the data were sufficiently rigorous, that is they appeared reliable (Wong et al., Citation2013, p. 34). Studies (N = 23) were excluded where insufficient data could be gathered. shows the search and inclusion process for EIP-AHA partner good practice related evidence.

Evidence gathered during Stages 2 and 3, and details of the included studies can be found in the supplementary information (Appendix 2). Once the evidence from Stages 1, 2 and 3 had been collated, we moved on to the evidence synthesis phase.

Evidence synthesis and framework analysis

We collated information on study design, population, sample size, experimental and control interventions, outcomes, programmes theories and potential causal mechanisms. We specifically searched for the mechanisms proposed by the studies’ authors to explain the success or failure of the various programmes, and noted these findings to build the narrative. At all stages of the process, the literature was interrogated both for patterns and conflicting accounts.

We mapped demi-regularities or recurrent patterns of contexts and outcomes with their proposed causal mechanisms and constructed them as explanatory ‘context-mechanism-outcome’ (CMO) configurations. The context (C) of an intervention is critical in that it creates the conditions for the triggering of the mechanism (M) which leads to particular outcomes (O). The realist review model involves developing a CMO pattern which enables the reviewer to fully understand which aspects of the intervention make it effective or ineffective and which factors are required to replicate success across a range of contexts.

Mechanisms of success and failure were synthesised with key findings using an overarching thematic analysis (framework analysis) approach (Ritchie, Spencer, & O’Connor, Citation2003). We categorised theories into two groups: theories of why frailty interventions worked and theories of why frailty interventions did not work. Evidence gathered in Stages 1, 2 and 3 was categorised by context and effect, i.e., whether that factor led to the ‘success’ or ‘failure’ of an intervention and then further distilled into mechanisms deriving from theories of causes of frailty, theories on management of frailty and those based on the intervention process.

Development of recommendations to support future intervention design

To develop and present recommendations for future intervention design, theories were further analysed by context, in order to determine the role of country, healthcare context and participant demographics on efficacy and produce targeted recommendations.

Results

Framework analysis

Theories of why frailty interventions work

Successes in frailty interventions can be broadly attributed to three factors, ‘resolution’ of a theoretical cause of frailty in the individual; ‘resolution’ of an issue in the management of frailty; or success in the intervention process which leads to the desired outcome (often resolution of an issue) through, for example, greater commitment to the programme. The factors in intervention success are listed in by context, in order to assist with intervention design.

Table 1. Factors that enhance the efficacy of frailty interventions.

‘Resolution’ of a theoretical cause of frailty in the individual

Many interventions were based on the theory that frailty is caused by ‘deficiencies’ in the older adult, either physical, perhaps an age-related functional decline including changes in muscle quality or mass (Bonnefoy et al., Citation2012); nutritional (e.g., Bonnefoy et al., Citation2012; Kim et al., Citation2015; Ng et al., Citation2015); hormonal (Muller, van den Beld, van der Schouw, Grobbee, & Lamberts, Citation2006); educational (Behm et al., Citation2016; Gustafsson et al., Citation2012); cognitive (Apóstolo, Cardoso, Rosa, & Paúl, Citation2014) or a combination of those. These theories hypothesise that by resolving or offsetting the deficit, for example, by ensuring proper nutritional intake, by replenishing hormones, or by improving physical function through exercise, then the body is brought back to an optimum state of health which in turn reduces or postpones the progression of frailty and improves functional capacity.

Resolution of nutritional deficiency

Five studies examined nutritional outcomes in participants (Bonnefoy et al., Citation2012; Chan et al., Citation2012; Kim et al., Citation2015; Kim & Lee, Citation2013; Ng et al., Citation2015), three of which were in combination with exercise (Bonnefoy et al., Citation2012; Kim et al., Citation2015; Ng et al., Citation2015).

Two of these studies cited an increase in food intake as one of the potential mechanism of success in their intervention (Kim & Lee, Citation2013; Ng et al., Citation2015), and another cited the same mechanism but only in good compliers (Bonnefoy et al., Citation2012).

The intervention that was conducted in already well-nourished participants (Bonnefoy et al., Citation2012) was not successful in improving nutritional or frailty status, although the authors did demonstrate that protein supplementation stabilised walking speed, walking time and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). However, where participants were frail (measured using Fried’s phenotype) and undernourished at baseline, in for example, micronutrients such as Vitamin D (Chan et al., Citation2012) or overall dietary intake in participants with low socio-economic status (Kim & Lee, Citation2013), supplementation had a significant effect on frailty progression.

In combination with exercise, nutritional supplementation in undernourished populations appears to have positive effects over and above those found by nutritional interventions alone (Kim et al., Citation2015; Ng et al., Citation2015). The mechanisms here are unclear but it may be that nutritional interventions are more effective in conjunction with physical activity due to increased appetite and changes in anabolic processes that occur when physical activity takes place. The findings suggest that nutritional interventions and supplements work best in the context of participant deficiency, that is, when they require the additional energy or nutrients. However, in order to control for the effects of nutritional deficiencies on exercise interventions, and the synergistic effect in nutrient depleted individuals, researchers should consider correcting nutritional status before exercise interventions begin.

Offsetting the major physical parameters of frailty (e.g., decreased mobility, reduced balance, relative inactivity)

All exercise or multicomponent interventions were built around the theory that the major physical parameters of frailty could be offset or improved through exercise.

Three interventions (Cadore et al., Citation2014; Clegg, Barber, Young, Iliffe, & Forster, Citation2014; Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2010) were based on the theory that specific training for tasks in everyday activities would improve functional outcomes. While Clegg et al. (Citation2014) demonstrated a non-significant trend towards improved mobility (in the timed up and go test) in the intervention group, Cadore et al. (Citation2014) and Giné-Garriga et al. (Citation2010) were both effective in preventing the progression of frailty in some markers of frailty. Two interventions (Hars et al., Citation2014; Wolf et al., Citation1996) used established exercise forms, tai chi and eurhythmics, respectively, as the basis of their interventions. These activities have a strong balance component and the theory was that this would improve physical function and body awareness in older adults. Both studies were successful in terms of balance improvements and long-term commitment to exercise in some participants. Four interventions were based on theories of physical inactivity exacerbating markers of frailty in older adults (Bonnefoy et al., Citation2012; Carrapatoso, Citation2015; Palummeri, Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Wanderley, Mota, & Carvalho, Citation2010), and to varying extents stabilised or improved functional fitness in participants.

Finally, four were founded in the belief that training for strength and functional ability, including mobility and balance, would improve aspects of physical frailty (Carvalho, Marques, Soares, & Mota, Citation2010; Chan et al., Citation2012; Kim et al., Citation2015; Ng et al., Citation2015). These interventions were all successful with two authors (Chan et al., Citation2012; Kim et al., Citation2015) reporting a transition between frailty states, i.e., frail to pre-frail, or pre-frail to non-frail. These multicomponent interventions share contexts including participants with a frail or pre-frail diagnosis according to Fried’s criteria, as well as an Asian background.

Interventions based on group exercise (Cadore et al., Citation2014; Carrapatoso, Citation2015; Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2010; Hars et al., Citation2014; Ng et al., Citation2015; Palummeri, Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Wolf et al., Citation1996) were effective in preventing the progression of frailty and pre-frailty, at least in some of the frailty indicators, e.g., sum of indicators, weakness (Cadore et al., Citation2014; Wolf et al., Citation1996), slowness (Carrapatoso, Citation2015; Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2010; Hars et al., Citation2014; Ng et al., Citation2015; Wanderley et al., Citation2010), balance (Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2010) and ADL (Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2010). These effects were found irrespective of exercise type (Cadore et al., Citation2014; Carrapatoso, Citation2015; Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2010; Hars et al., Citation2014; Ng et al., Citation2015; Palummeri, Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Wanderley et al., Citation2010; Wolf et al., Citation1996).

Offsetting cognitive challenges

Of the studies that examined cognition, most were developed around the theory that age-related decline in cognitive function, specifically memory, attention, executive function and information-processing skills could be improved through targeted training. One review study (Ng et al., Citation2015) and six partner good practices, i.e., Long Lasting Memories (LLM: Bamidis, Citation2012), Memory training (Palummeri, Citation2012c), Cognitive stimulation and brain fitness (Apóstolo et al., Citation2013, Citation2014; Apóstolo, Cardoso, Marta, & Amaral, Citation2011; Apóstolo, Cardoso, Paúl, Rodrigues, & Macedo, Citation2016), Psychological Support Program for the Elderly (PAPI: Sousa & Costa, Citation2013), Old Town New Elders (European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing, Citation2013, p. 27) and Promoting Active Healthy Ageing (from survey results, see Gwyther et al., Citation2017) examined cognitive skills in interventions.

The cognitive interventions had mixed results. Interventions in pre-frail participants who were relatively well had limited or no effects on frailty. Weekly cognitive training targeting memory and recall (Ng et al., Citation2015) in primarily pre-frail participants reduced frailty (measured using Fried’s criteria) through improved lower limb strength at 12 months, and reduced weakness at 6 and 12 months. Although these effects were slight, a clear mechanism is not proposed, and may have been related to chance. More profound effects on frailty scores were associated with a multicomponent (physical, cognitive, nutritional) intervention examined in the same study.

EIP-AHA partner cognitive training interventions, Memory Training (Palummeri, Citation2012c) and PAPI (Sousa & Costa, Citation2013) found improvements in cognitive performance and depression scores. Both of these trials were group-based interventions but there was insufficient evidence to further explore the mechanisms of action.

‘Resolution’ of an issue in the organisational context or management of frailty

Rather than offsetting ‘deficiencies’ in the older adult, other interventions suggest resolving issues in organisational factors, such as the healthcare system and services in order to improve the treatment of frailty. These theories hypothesise that innovative changes in healthcare delivery will result in a more patient-centred approach, a reduction in the fragmentation of services and an improvement in care for older adults, which ultimately result in improvements in health. Interventions directed at the organisational level tended to examine a more comprehensive range of outcomes, as compared with individual interventions which tended to examine frailty based on physical indicators. Themes related to theories of why these interventions worked included: improving communication improves response to health needs, personalised healthcare strategies delivered via multi-disciplinary teams improve outcomes for older adults and interventions grounded in health psychology positively affect health behaviours.

Improving communication improves response to health needs

One intervention which demonstrated significant changes in frailty status (Favela et al., Citation2013), measured by Fried’s phenotype (Fried et al., Citation2001), was conducted in Mexico on a sample of 133 ‘young’ older adults with slow gait, low educational attainment, in poor health, and who were at risk of, or experiencing malnutrition. This intervention was based on the theory that improved communication between participants and clinical staff (nurses) would improve efficiency in responding to health needs in older adults. Intervention participants received weekly visits from a nurse over nine months and an alert button to contact the nurse when required. Authors suggested that the alert button provided patients with a ‘sense of security’ (Favela et al., Citation2013, p. 93) and ‘was of great support in the processes of communication and decision-making between the nurse and the patient’ (Favela et al., Citation2013, p. 93). The alert button may also have been a motivating factor for nurses in that they were monitored and required to resolve patients’ telephone calls. Other potential mechanisms not explicitly described by the authors but deriving from the real-world FOCUS findings (e.g., D’Avanzo et al., Citation2017) include the older adults’ ability to actively engage in relationships with care providers, i.e., the empowerment of the patient through the communication device, as well as goal setting and reinforcement of specific targets. The social interaction and benevolent attention of receiving a regular visit may also be important, although if that was the case, the second intervention group (with nurse home visits but without an alert button) would have also demonstrated effects. The authors suggest that this variation in findings might be due to lack of standardisation in the content, type and quality of interaction between nurse and patient, or heterogeneity in nurses and their training profiles, although it may also be due to a lack of professional monitoring, highlighting the important issue of fidelity to protocol in any intervention.

Personalised healthcare strategies delivered via multi-disciplinary teams improve outcomes for older adults

Several interventions (Cohen et al., Citation2002; Eklund, Wilhelmson, Gustafsson, Landahl, & Dahlin-Ivanoff, Citation2013; Fairhall et al., Citation2015; Li, Chen, Li, Wang, & Wu, Citation2010) were based on the theory that geriatric screening and evaluation would lead to more effective management of clinical conditions through the provision of personalised strategies and services to older adults via multi-disciplinary, skilled teams of professionals. The context of intervention delivery (inpatient, outpatient, primary care) was explored to determine whether any mechanisms could be found.

Fairhall et al. (Citation2015) demonstrated a reduction in frailty status (defined using Fried’s phenotype) in frail, community-dwelling participants who had been discharged from a rehabilitation and care service. The multi-factorial intervention targeting GEM components was delivered by an interdisciplinary team. We hypothesise that likely mechanisms include effective care planning and social contact. However, it may also be that participants were simply recovering after illness/injury and that some of the frailty reversal is a result of natural recovery.

Li et al. (Citation2010) also demonstrated a favourable but not significant trend towards frailty transition in pre-frail and frail Taiwanese older adults. Personalised comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) screening and interventions tended to improve frailty status and Barthel Index (measures of daily functioning) scores at the six-month follow-up. The authors suggested that potential mechanisms included easy access for patient referrals, as well as the participation of skilled and trained professionals.

Team interventions with outpatients (Cohen et al., Citation2002; Eklund et al., Citation2013) and community-dwelling older adults (Li et al., Citation2010) according to individual needs had no effect on the prevalence of frailty (Cohen et al., Citation2002; Eklund et al., Citation2013; Li et al., Citation2010). Similarly, the CARTS (O’Caoimh et al., Citation2015) programme based on CGA also failed to demonstrate changes in frailty status, although promising but not statistically significant effects were seen on adverse outcomes in a small pilot sample of Irish participants.

Although little evidence could be found for frailty transitions, changes in secondary outcomes were noted, specifically in ADLs. Interventions that can prevent or reduce ADL disability can have a positive impact on older adults and societal healthcare costs. Two studies demonstrated an effect on ADLs (Cohen et al., Citation2002; Eklund et al., Citation2013). Cohen et al. (Citation2002) determined that GEM care in veteran hospitals in the United States positively affected basic ADL scores in a large (N = 1388), predominantly male (98%) sample of adults, mean age 74 years. The potential mechanism here included an unusually long stay as an inpatient, which may have advantages in terms of decision-making and improved communication with healthcare professionals, as demonstrated by the higher mean numbers of medical and surgical consultations (Cohen et al., Citation2002).

In Sweden, Eklund et al. (Citation2013) examined continuum care, which was planned in the participants’ homes by a multi-professional team (including a geriatric nurse and case manager). They found that this improved independence in ADLs (measured using an extended hierarchical ‘ADL staircase assessment’; Jakobsson, Citation2008), for up to 12 months over usual care, and postponed dependence for up to 6 months, in a group aged over 80 years who were dependent in at least one ADL. Transitions were also noted between frailty levels (measured using a frailty index which included cognitive impairment) in both groups in positive and negative directions, although these were not significant. The authors suggest that this is due to the high quality of usual care as well as the fact that participants were initially very frail and so results may be limited. They suggest that an outcome measure based on wider psychosocial markers may increase sensitivity. Certainly, the evidence from this review suggests that the frailty paradigm chosen to measure outcomes in intervention studies does matter. It may be that a full cumulative model which includes functional and psychosocial variables would have better demonstrated changes in frailty status. The authors also cite integration of care, early identification of needs, patient planning based on geriatric assessment at home and regular follow-ups as key mechanisms to their success.

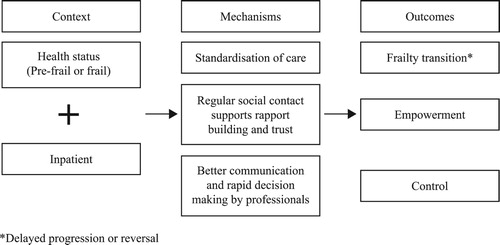

Person-centred, inpatient care in GEM units by multi-disciplinary teams was more successful and improved frailty status in frail older adults (Fairhall et al., Citation2015), and positively affected basic ADL scores (Cohen et al., Citation2002). We suggest that the structured procedures and health monitoring (by nurses, researchers, clinical care teams) of inpatients ensure that effective relationships are built between participants and health professionals which facilitates effective communication and rapid decision-making processes. There may also be a level of trust and rapport which develops during regular social contact between visiting professionals and participants which enables patients to feel supported and valued by practitioners. The importance of these mechanisms was also emphasised within the FOCUS real-world studies where it was suggested that improved communication leads to feelings of empowerment and control for older adults. This is illustrated in the CMO proposal in .

Interventions grounded in health psychology positively affect health behaviours

Since frailty is a dynamic process, it would naturally be expected to progress over time, and so reversal or transition out of frailty may not be the only beneficial outcome. Instead, halting the progression of frailty or maintaining a status quo might also be advantageous. This was noted in one study which used a health psychology approach: Gustafsson et al. (Citation2012) attempted to delay deterioration of frailty in independent older adults, median age 85–86 years, through a health promotion intervention. Two intervention arms with a participatory and client-centred approach (i.e., discussions centred on client needs) were conducted; one included health promotion within group meetings and the other a single preventative home visit. Both interventions delayed deterioration in self-related health, and the group meeting intervention postponed dependency in ADLs, but no change was seen in frailty scores.

De Vriendt, Peersman, Florus, Verbeke, and Van De Velde (Citation2016) delivered a client-centred, individually tailored activity oriented programme to a mainly female group (79.76%). They used motivational interviewing, goal setting and therapy plan (problem-solving) negotiations to determine the actual intervention with the aim of delivering functional improvements. The intervention group experienced greater improvements in basic ADL (p = .013) than control group participants. Trends toward improved physical functioning and vitality were also noted. The authors suggest that the success of the intervention was due to goal facilitation and personal tailoring to the participants’ needs. The authors raised the need to focus on a multi-dimensional concept of frailty and the participation of the stakeholders in the design of their own intervention.

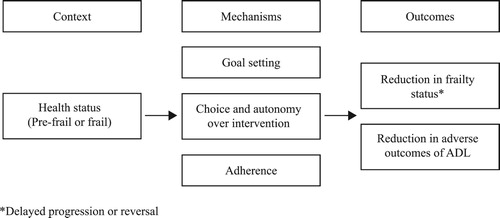

Three other studies (Clegg et al., Citation2014; Favela et al., Citation2013; Gustafsson et al., Citation2012) also utilised health psychology components within their interventions, e.g., goal setting and motivational interviewing. The use of these components appears to improve adherence. For example, there was only a 13% drop out rate in Favela et al.’s (Citation2013), Mexican study with quite frail older people: half of these were due to mortality, with only two refusals. We hypothesise that the use of health psychology components ensures that interventions are client centred, that participants are stimulated and motivated to improve their personal circumstances through goal setting and reinforcement and that goals are specific, realistic and targeted. In these instances, it may be that the success of the intervention (in terms of adherence) is due to properly targeting older adults’ activity needs and requirements, i.e., what they actually want to do, rather than what professionals think that they want/ought to do. This in turn empowers them to take control and make lifestyle changes. The proposed CMO is shown in .

Success in the intervention process

Success in the intervention process can often be credited to factors which help to overcome barriers to participation and motivation. Across the interventions, we noted four factors, which appeared to enhance success but were not always documented prior to the intervention. These included: the influence of social interaction; generating positive affect; having realistic expectations of participants; and creating an appropriate intervention environment for participants.

The influence of social interaction

Conducting interventions within a group context appears particularly effective for improving participant adherence and commitment to the programme, perhaps through the mechanism of an enhanced motivation to attend. Generating social interaction might also be considered a method of addressing a social ‘deficit’ in older adults.

Social interaction was noted as a mechanism of success, either explicitly or implicitly, in nine studies (Apóstolo et al., Citation2014; Old Town New Elders and Phytfrail, see Carrapatoso, Citation2015; Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2010; Gwyther et al., Citation2017; Hars et al., Citation2014; Kim et al., Citation2015; Ng et al., Citation2015; Palummeri, Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Wanderley et al., Citation2010; Wolf et al., Citation1996).

The social (group) intervention Cognitive Stimulation and Brain Fitness (Apóstolo et al., Citation2011; Apóstolo et al., Citation2013; Apóstolo et al., Citation2014; Apóstolo et al., Citation2016) found improvements in IADL and depressive symptoms but not cognition. These effects were more apparent in participants with fewer than five years’ education.

A social dynamic was important in the ‘Portuguese National Walking and Running Programme’ (PNWRP: Carrapatoso, Citation2015) which determined significant improvements in functional fitness in participants after 10 months walking training, as well as positive effects on psychological distress, capability and mood. One mechanism cited here was a feeling of commitment to other group members and the teacher.

Phytfrail (European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing, Citation2013, p. 246) reported a reduction in adverse outcomes that of unplanned hospital admissions. This Italian intervention with frail and pre-frail patients consisted of physical activity, rehabilitation and diet. One of the cited mechanisms for success here was that participants had the opportunity to socialise which is likely to have improved adherence. However, further details were unavailable to enable full comparison.

Certainly, a social aspect appears to provide a mechanism for improving adherence and/or compliance in short-term, group-based exercise interventions (Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2010; Kim et al., Citation2015; Ng et al., Citation2015; Wolf et al., Citation1996). Here compliance ranged from 80% (Wolf et al., Citation1996) to 90% (Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2010), which was generally higher than that in self-directed and home-based interventions (e.g., 48%: Bonnefoy et al., Citation2012). In two interventions with strong social components, some participants chose to continue with their training after the end of the intervention (Hars et al., Citation2014; Wolf et al., Citation1996). This suggests that the social context of being in a group is critical in generating the commitment mechanism, which in turn delivers outcomes.

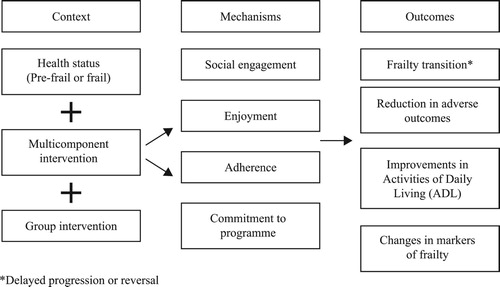

Differences between outcomes in intervention studies may also be explained by affective mechanisms within the social nature of the intervention; perhaps interventions are more fun in a group (Bamidis, Citation2012; Carrapatoso, Citation2015; Hars et al., Citation2014), or perhaps there is an expectation and level of support among group members (Carrapatoso, Citation2015), which builds commitment to exercise and each other. Further, participants may experience feelings of belonging and safety (Carrapatoso, Citation2015) when exercising in a group, which may encourage them to exercise. We hypothesise that, as well as providing social engagement, group activity improves self-efficacy through seeing others perform better (or worse) than yourself and having the reassurance of the instructor, although this mechanism was not explicitly described. However, the secondary role of the reduction of social isolation, a risk factor for frailty itself, should not be under-estimated.

Generating positive affect

The influence of enjoyment and positive affect was seen across nutritional, cognitive and exercise interventions. A gastrological intervention by an EIP-AHA partner (Van Damme, Buijck, Goossens, & Beeckman, Citation2015) demonstrated that nursing home residents ate more and reduced their risk of malnutrition (p = .03) when they enjoyed the food (p = .021), although the authors did not translate these findings into changes in frailty parameters.

EIP-AHA partner multicomponent (exercise and cognitive) interventions, LLM (Bamidis, Citation2012) and Promoting Active Healthy Ageing (see Gwyther et al., Citation2017) noted cognitive improvements in episodic and working memory as well as improvements in symptoms of depression (LLM; Bamidis, Citation2012) and adverse outcomes including lower rates of institutionalisation and rates of falls and fractures compared to the control group. A proposed mechanism for the LLM intervention was that participants described feelings of positive affect towards the programme; they described it as ‘fun’, stated that they liked the programme and that they felt cheerful afterwards, as well as believing that it was beneficial and enabling them to feel more in control of their health.

Likewise, the mechanisms described in the ‘PNWRP’ (Carrapatoso, Citation2015) included having fun, one participant said that they ‘laugh and occupy the time’ (Carrapatoso, Citation2015, p. 52), enjoyment of the exercise, the scenery and exploration of new areas, and feeling safe while walking. Other exercise interventions (Hars et al., Citation2014, p. 402) described the ‘enjoyability’ of the programme and the authors theorised about the use of music as a mechanism to increase enjoyment and improve adherence in older adults to exercise interventions.

A hypothesised CMO for both social interaction and enjoyment is described in . In this instance, it would appear that in the context of multicomponent group interventions, mechanisms of enjoyment, where the participants describe positive affective feelings about the programme, result in improved outcomes.

Having realistic expectations of participants

Another potential mechanism of success is that of having an intervention design with realistic and reasonable expectations of participants, particularly in terms of their ability to commit to a programme. Two authors suggested that minimising participant burden and ensuring a low intensity (in terms of frequency) and realistic (weekly) schedule for exercise (Hars et al., Citation2014) or other activities (De Vriendt et al., Citation2016) were critical as a mechanism of intervention success. Another author (APA: Palummeri, Citation2012a; Palummeri, Citation2012b) suggested that a fortnightly training schedule was appropriate and noted positive changes in tests of mobility and balance, as well as reductions in prescribed medications.

Two slightly more demanding, twice-weekly exercise interventions (Cadore et al., Citation2014; Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2010) in nursing home residents and community older adults, respectively, noted improvements in functional outcomes in physically frail older adults including ADLs and chair rise tests.

Conversely, in an intensive 12-week home-based, pilot exercise programme (Clegg et al., Citation2014), the authors suggested that the intensity of the exercise programme (15 minutes, three times per day on five days each week) may have been a contributing factor in low compliance rates for frail participants. This intervention was presented in an exercise manual and delivered by community-based physiotherapists. Participants were stratified according to their level of frailty and total mean adherence was 46%. The similarly unsupervised, daily (20 minutes) exercise session delivered or supported by home helpers in France (Bonnefoy et al., Citation2012) also resulted in low compliance (48%) albeit with a positive outcome in that it stabilised maximum walking time.

More intensive intervention designs were employed in three community exercise intervention programmes focused on mobility, strength and balance training (Chan et al., Citation2012; Kim et al., Citation2015; Ng et al., Citation2015). Attendance for the thrice-weekly exercise intervention (Chan et al., Citation2012) was lower than that for the twice-weekly sessions (Kim et al., Citation2015; Ng et al., Citation2015) but all noted a reduction in frailty.

In the exercise interventions, most studies (Cadore et al., Citation2014; Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2010; Hars et al., Citation2014; Kim et al., Citation2015; Ng et al., Citation2015; Wolf et al., Citation1996) described that sessions were supervised by instructors who had realistic expectations about their participants and could make necessary adjustments to the duration and intensity of exercise programmes. The real-world findings from a study of stakeholders (Shaw et al., Citation2017) confirmed this mechanism. Stakeholders relayed that it was critical to ensure that exercises were suitable for frail older adults, and, for some groups, that appropriate supervision was available.

Creating an appropriate intervention environment for participants

The final theme relates to the creation of an appropriate intervention environment for older adults, this includes mechanisms relating to ensuring appropriate access arrangements, providing participants with choice and autonomy over their intervention components and consideration of any financial commitments.

Chan et al. (Citation2012) noted that difficulties in accessing the intervention site led to reduced levels of participant compliance, which resulted in poor adherence and devalued outcomes. Whereas, in Kim et al.’s (Citation2015) study, participants had a choice of four exercise sessions per day, in their local area and adherence was high, with positive changes in frailty. Similarly, in the APA intervention (Palummeri, Citation2012a, Citation2012b) participants were also given choice and autonomy over their activities, which the authors suggested enhanced their interest and motivation and led to positive changes in mobility and prescribed medication usage.

The financial cost of programmes to participants is also critical. Hars et al. (Citation2014) charged participants to attend after the end of the original free trial period and were successful in maintaining longer term adherence to their eurhythmics programme, although some people cited the cost of the programme as a barrier to their ongoing participation. The EIP-AHA good practice group interventions, APA (Palummeri, Citation2012b, Citation2012c) and Exercise and Health for Older Adults (EHOA; Carvalho et al., Citation2010) were self-financed but relatively low cost, which suggests that participants were invested and committed. Both studies noted improvements in physical markers of frailty, for example, weakness (APA and EHOA), as well as reductions in medication (APA only).

Theories of why frailty interventions do not work

Common reasons for failure of interventions include the theory that there was a lack of need in the participants, i.e., that they were ‘too well’, that the programme was not implemented properly and that there were issues with the intervention design, e.g., the timeframe was too short to demonstrate effects or there were too few participants (i.e., compliance and/or adherence was low). Some of the barriers and challenges to intervention success are listed in .

Table 2. Barriers and challenges to intervention success.

Correcting an issue that does not exist

The problem with basing an intervention on correcting a ‘deficiency’ is that if there is no deficit, i.e., physical, nutritional and cognitive parameters are within normal bounds, then the intervention may not work.

Participants are not frail

The critical deficit to be addressed within a frailty intervention is that of frailty itself. Eleven studies within the systematic review (Behm et al., Citation2016; Cadore et al., Citation2014; Chan et al., Citation2012; Fairhall et al., Citation2015; Favela et al., Citation2013; Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2010; Gustafsson et al., Citation2012; Hars et al., Citation2014; Kim et al., Citation2015; Li et al., Citation2010; Ng et al., Citation2015) measured frailty according to Fried’s phenotype (Fried et al., Citation2001). Of these, four (Cadore et al., Citation2014; Fairhall et al., Citation2015; Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2010; Kim et al., Citation2015) were based on an entirely frail sample. All four of these interventions demonstrated positive effects in terms of frailty transitions (Fairhall et al., Citation2015), reversal of components of frailty (Cadore et al., Citation2014; Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2010; Kim et al., Citation2015) and adverse outcomes including falls (Cadore et al., Citation2014). The rest of the interventions ranged from having no frail participants (Hars et al., Citation2014) to 45% frail participants (Favela et al., Citation2013). Despite having no frail participants at baseline (37% were robust and 63% were pre-frail), Hars et al.’s (Citation2014) long-term, music-based exercise intervention demonstrated significant improvement in components of frailty including gait and balance when compared with controls, over a period of four years. In fact, this intervention demonstrates that frailty prevention is achievable. That is, specific frailty interventions seem to work across the range of initial frailty levels in terms of both influencing and preventing frailty.

Participants are not ‘deficient’ in the requisite aspect

Other studies also attempted to address ‘deficiencies’ in participants. One study, Muller et al. (Citation2006) examined the effects of hormone replacement therapy in men. The authors’ proposed that age-related declines in androgens affect frailty status and that hormone replacement improves the course of frailty by increasing lean body mass and muscle strength, and reducing fat mass. The intervention had no influence on frailty status. The authors speculated that the mechanism of failure was that baseline serum testosterone levels were within normal levels. Other authors suggested that their population were ‘too well’ (Hars et al., Citation2014; Monteserin et al., Citation2010; Ng et al., Citation2015; van Hout et al., Citation2010) to demonstrate an effect.

Participants are already well educated

Gustafsson et al. (Citation2012) and Behm et al. (Citation2016) attempted to delay deterioration of frailty through health promotion interventions, and compared preventative home visits with multi-professional group meetings and a control group. These separate studies report findings from the same dataset. Although for the former, results were favourable, with delays in deterioration of self-rated health, no change was seen in frailty scores, as measured using a six-item phenotype (weakness, fatigue, weight loss, low physical activity, poor balance and gait speed). The authors suggested that the timeframe (three months) was too short. However, the authors also suggested that the participants’ level of education might also be a barrier to success. Similarly, for the latter, no difference was noted between groups in terms of frailty status, measured using an extended eight-item phenotype (incorporating visual impairment and cognitive ability, measured using the MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, Citation1975). However, these authors noted a postponement in the progression of subjective frailty, for up to one year using a subjective measure of frailty, the Mob-T Scale (Schultz-Larsen & Avlund, Citation2007) to determine tiredness in daily activities.

Limited or no difference from usual care

In the main, healthcare interventions that did not result in changes in frailty status (Behm et al., Citation2016; Cohen et al., Citation2002; Eklund et al., Citation2013; Gustafsson et al., Citation2012; Li et al., Citation2010) were located in relatively financially secure countries with established healthcare systems. There are various theories as to the reasons for the lack of effects. In the instances where a change in adverse outcome or ADL was noted but not a change in frailty status in comparison to a control group receiving standard care, it may be that intervention care and standard care are not sufficiently different (e.g., Cohen et al., Citation2002; Eklund et al., Citation2013). In countries such as Belgium, Sweden and USA, particularly frail and disabled older adults can expect a high standard of care. However, it may be that participants from less developed countries and/or with lower socio-economic backgrounds, such as those seen in the studies from Mexico (Favela et al., Citation2013) and South Korea (Kim & Lee, Citation2013), benefit more and thus are more likely to demonstrate changes in frailty status and functional decline in comparison to a control group. Further, in a population of particularly frail older adults, it may be that small but significant functional improvements in ADL measures would not be reflected in global physical frailty phenotype scores. This theory supports the ‘intervention window’ theory in that transitions out of physical frailty can only occur in the relatively well (or rather not disabled) frail older adults. However, transitions out of frailty may still be evident in frailer adults where broader, bio-psychosocial frailty index measures are taken into account. That is, a more holistic concept of frailty which includes non-physical components such as social isolation or cognition, or perhaps even personal resilience and coping strategies, would both give a better view of the impact of interventions but also guide the full design of future interventions.

Improper implementation of the intervention

Other theories for the lack of effects in health services interventions include the programme not being implemented properly (Li et al., Citation2010), usually through low compliance on the part of the participants (Clegg et al., Citation2014; Li et al., Citation2010) or a failure to go beyond ‘usual’ care (Li et al., Citation2010) and/or a lack of standardisation in professionals’ services (Favela et al., Citation2013; Li et al., Citation2010), leading to variation in the content and quality of the interaction between the professional and the patient.

Issues with intervention design

One final theory is that of flaws in the intervention design. Four authors (Clegg et al., Citation2014; Gustafsson et al., Citation2012; Muller et al., Citation2006; van Hout et al., Citation2010) suggested that the length of the study was too short to demonstrate an effect. Findings from the FOCUS real-world studies describe that a ‘rhythm’ (D’Avanzo et al., Citation2017, p.13) of activity needs to be established in order for participants to engage and for efforts to become habitual. It may be that the duration of interventions was insufficient for participants to develop this rhythm. Finally, one author (Gustafsson et al., Citation2012) suggested that the chosen measures were not sensitive enough to show an effect. Certainly, where a change in frailty status is the desired outcome and measures of frailty are based on a categorical variable, as opposed to a continuous variable, there is less chance to show evidence of improvement. For example, within a very frail group – there may be significant improvements that have an important effect on outcomes for individuals but which may not take them over the boundary of a frail classification.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to examine what works for whom and in what circumstances in terms of interventions and care in the context of age-related frailty. Key mechanisms, contextual factors and possible social processes have been examined. Although there were few frailty interventions that decisively changed frailty status of older adults across the boundaries of frail, pre-frail and robust, the most compelling evidence was for physical exercise in a group setting, and for multicomponent interventions. These types of interventions often had additional positive impacts on independence, functioning, psychological wellbeing and perceptions of health. Effects on social isolation were also apparent.

Before concluding with recommendations for the design of frailty interventions, we first highlight some general issues with the available studies that should be overcome. There were missed opportunities in the studies reviewed to demonstrate a change in frailty status, as often researchers or healthcare practitioners screened for frailty but then did not re-test using the same indices after the intervention. Indeed, frailty screening was often done to define participants as suitable for the intervention, rather than seen as something that may change. This seemed to perhaps be related to an underlying lag in understanding that frailty is dynamic and that transition in a positive direction is possible.

Further, there were inconsistencies in the methods used for screening and measuring frailty that make direct comparisons between studies difficult. While screening tools and evaluation methods may need to vary depending on context, this highlights the need for a standardised set of instruments (see Apóstolo et al., Citation2017 for a review) to determine the best intervention methods. Although significant positive changes were apparent at different levels of frailty, and also in samples that were robust or pre-frail, the effect of initial level of frailty on the effectiveness of interventions was not systematically analysed. There is an urgent need for this factor to be systematically included in future research, specifically in terms of understanding and delivering the most appropriate intervention at specific time points in the progression of frailty.

Another design issue is the choice of outcome measurement and the way in which that affects whether an intervention is viewed as effective or not (i.e., the frailty transition). There is a noticeable effect in this review where frailty is defined and measured using interval scales as opposed to Fried et al.’s (Citation2001) categorical phenotype. It may be that a full cumulative model, a continuous variable, which includes functional and psychosocial variables, would have better demonstrated changes in frailty status, and would also provide an opportunity to monitor changes within frailty states. Certainly, the evidence from this review suggests that the frailty paradigm chosen to measure outcomes in intervention studies does matter.

Nevertheless, frailty interventions reduced frailty in frail populations. Exercise and exercise-nutrition-social-cognitive multicomponent interventions seemed positive for a range of levels of frailty and ages, including studies with very old groups (over 85 years). While some authors (e.g., Eklund et al., Citation2013; Gustafsson et al., Citation2012) perceived there to be an ‘intervention window’ (Topinková, Citation2008) for physical transitions in older adults, there was little evidence of this here, although it was not systematically studied. However, physical interventions based on a perception of deficit clearly only worked well when participants were indeed compromised – this was particularly the case for dietary supplementation, but also the one hormonal intervention included. Although nutritional interventions are widely purported to be an important component of frailty management, other studies (Fiatarone et al., Citation1994; Milne, Avenell, & Potter, Citation2006; Payette, Boutier, Coulombe, & Gray-Donald, Citation2002) failed to demonstrate convincing effects and perhaps this finding provides an explanation. Further research could evaluate baseline thresholds of nutritional and hormonal status to determine the point at which single interventions would benefit older adults.

Care management interventions had more mixed success: GEM interventions appeared to be most successful in moderate (but not disabled) levels of frailty, and specifically after a traumatic event, e.g., a fall. Certainly, this is in accordance with the literature which has demonstrated the positive impact of GEM interventions on functional decline and the need for institutionalisation after one year in acutely ill older adults (Van Craen et al., Citation2010). In terms of context, outpatient and primary care settings appear to be equally as effective in terms of GEM interventions, but inpatient clinical settings were more effective than both in this type of care management intervention. The proposed mechanism is important here. GEM- and CGA-based interventions are based on the premise that geriatric screening and evaluation lead to improved care because personalised care strategies and services are better managed through multi-disciplinary teams. However, the actual mechanisms highlighted in the successful inpatient GEM-based study were rapid decision-making and improved communication, particularly between healthcare professionals.

Nevertheless, even though frailty status was not changed in these studies, there were still clear improvements in ADL independence. This is critical as increased ADL dependence is associated with increased risk of mortality (Jakobsson & Karlsson, Citation2011), while maintaining independence can improve quality of life (Netuveli & Blane, Citation2008) as well as reducing societal healthcare costs (Hay et al., Citation2002). This finding highlights that, even when no effect on frailty is shown, these interventions can improve functioning and coping, perhaps in the context of background frailty. That is, interventions to improve frailty scores can have influential secondary effects that should be examined alongside actual frailty levels to ensure benefit is clear even in the absence of an effect on frailty itself.

The importance of context was further highlighted in the contrast between different kinds of interventions. Exercise interventions appear to be more successful when delivered in a group setting, whereas positive outcomes were noted in both group settings and for personal home visits for person-centred, health planning and promotion interventions. The most successful GEM-based intervention in terms of frailty status was in the context of hospitalisation and recovery from trauma, but outpatient multi-disciplinary team interventions with very frail older people still showed impacts on functions. This may suggest an optimal context or time for different types and purposes of interventions. Further, we accept that new interventions in complex contexts take time to develop and mature effectively; thus, the short timescales of many of the interventions examined may mean that they have not achieved their full potential.

Psychosocial aspects to studies were not necessarily primary study variables, but where they were incorporated, for example, in the context of a physical intervention, greater impact in the physical indices was observed. This underlines that social and psychological aspects of an intervention are as important as the physical aspects, in particular to encourage adherence and promote wellbeing and self-efficacy. Inclusion of secondary impacts on mood, improving social networks and reducing loneliness, or interventions to improve aspects of cognition all seemed to add to the impact on frailty, and specifically address these further risk factors for frailty progression.

The importance of including the psychological dimension to ageing and frailty was a key finding coming from the FOCUS real-world studies (D’Avanzo et al., Citation2017; Shaw et al., Citation2017) with healthcare practitioners highlighting this as something they felt untrained to deal with, but stakeholders from all categories commenting on the link between physical and psychological frailty. Few interventions reviewed addressed this, but given the clear differentiating role of personal psychological resilience even in the context of physical frailty highlighted in discussions with healthcare practitioners (Shaw et al., Citation2017), the role of psychologists could be extended in terms of offering psychological support, and support to enable adaptive coping behaviours, such as selective optimisation and compensation strategies. Few interventions were grounded in health psychology theory, in terms of best practice methods for lifestyle changes, patient empowerment or person-centred care. Those studies that were designed using such components appear to demonstrate positive findings and also improve adherence in the full sample. Findings indicated the importance not just of individually focused ‘person-centred’ care, but also the importance of a person’s full, family, social and environmental contexts, suggesting that lifeworld-led care (Todres, Galvin, & Dahlberg, Citation2006) may improve the success of intervention and care efforts (Shaw et al., Citation2017). Issues such as access to an intervention location were cited as reasons for the poor success of an intervention, and so attention to transport needs and mobility issues would be expected to have an impact. The need to actively involve the older adult, in order to design an intervention that fits their goals, concerns and needs, was highlighted in several successful tailored interventions. Interventions that address person-specific issues and aims rather than generic older adult ‘problems’ and ensure that functional requirements (as defined by the individual themselves) are specifically targeted were shown as successful. Recommendations based on these findings are summarised in . These recommendations ultimately contributed to the final FOCUS project guidelines designed to inform decision-making and implementation of best practices for frailty management.

Table 3. Recommendations for intervention success and development.

Successful interventions are largely measured in terms of their success in transitioning people between frailty states, that is, from frail to pre-frail, or pre-frail to robust. However, there is also scope within interventions to improve wellbeing and quality of life by promoting change within a frailty state, for example, by reducing the deficit index score. Even a small change in score could result in improvements in wellbeing and quality of life for an individual, and reduction in outcome negative consequences of frailty.

Strengths and limitations of the review

To our knowledge, this is the first realist review of frailty interventions, and the first to enrich a systematically built theoretical framework with findings from ‘real-world’ studies and grey literature. Despite the heterogeneity of the interventions examined, and the lack of directly comparable interventions, we were able to demonstrate a range of CMO relationships. However, our study comes with limitations. One of the limitations is that the stringent quality-related inclusion criteria for FOCUS review studies may have reduced the quantity of interventions examined. Conversely, the rigorous appraisal process applied is a strength in that it demonstrates a consistent and systematic method of data extraction.

Conclusions and recommendations

The objective of our review was to build a theoretical framework, to explain the mechanisms of successful frailty interventions in different contexts, i.e., what works for whom and in what circumstances. Based on our findings, we make recommendations to support future intervention design (). We also strongly suggest that a sensitive, validated and reliable measure of frailty is taken pre- and post-intervention, and that initial frailty levels, presence or absence of specific deficits, and full person contexts are included as components of intervention design. Strategies to enhance the social and psychological aspects of interventions should be included even in physically focused interventions, in order to improve adherence and intervention success.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (299.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (483.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of other members of the FOCUS project: A. Nobili (IRCCS Istituto Di Ricerche Farmacologiche ‘Mario Negri’, Italy), A.González Segura (EVERIS Spain S.L.U, Spain), A. M. Martinez-Arroyo (ESAM Tecnología S.L., Spain), B. D’Avanzo (IRCCS Istituto Di Ricerche Farmacologiche ‘Mario Negri’, Italy), D. Kurpas (Family Medicine Department, Wroclaw Medical University, Poland), F. Germini (Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, 1280 Main St. W., Hamilton, ON L8S 4K1, Canada, previously IRCCS Ca’Granda Maggiore Policlinico Hospital Foundation, Milan, Italy), L. van Velsen (Roessingh Research and Development, Netherlands), M. Bujnowska-Fedak (Family Medicine Department, Wroclaw Medical University, Poland), R. Shaw (Psychology, Aston University, UK), R. Cooke (Psychology, Aston University, UK) and S. Santana (University of Aveiro, Portugal) who were co-responsible for the design and delivery of the FOCUS work package on which this realist review is based.

Statement of Ethical Approval: Ethical approval was provided by Aston University Research Ethics Committee, #844.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Holly Gwyther http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2867-4184

Elzbieta Bobrowicz-Campos http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5889-5642

João Apóstolo http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3050-4264

Maura Marcucci http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8468-7991

Carol Holland http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7109-6554

Additional information

Funding

References

- Apóstolo, J., Cardoso, D., Marta, L., & Amaral, T. (2011). Efeito da estimulação cognitiva em Idosos. Revista de Enfermagem Referência, 3(5), 193–201. doi: 10.12707/RIII11104

- Apóstolo, J., Cardoso, D., Paúl, C., Rodrigues, M., & Macedo, M. (2016). Efectos de la estimulación cognitiva sobre las personas mayores en el ámbito comunitario. Enfermería Clínica, 26(2), 111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.enfcli.2015.07.008

- Apóstolo, J., Cardoso, D., Rosa, A., & Paúl, C. (2014). The effect of cognitive stimulation on nursing home elders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 46(3), 157–166. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12072

- Apóstolo, J., Carvalho, A., Tavares, C., Cardoso, D., Carvalho, M., & Baptista, T. (2013). The effect of cognitive stimulation on depressive symptomatology and quality of life of elderly people. Journal of Aging and Innovation, 2(3), 82–91.

- Apóstolo, J., Cooke, R., Bobrowicz-Campos, E., Santana, S., Marcucci, M., Cano, A., … Holland, C. (2017). Predicting risk and outcomes for frail older adults: An umbrella review of frailty screening tools. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 15(4), 1154–1208. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003018

- Apóstolo, J., Cooke, R., Bobrowicz-Campos, E., Santana, S., Marcucci, M., Cano, A., … Holland, C. (2018). Effectiveness of interventions to prevent pre-frailty and frailty progression in older adults: A systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 16(1), 140–232. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003382

- Bamidis, P. D. (2012). Long lasting memories: Mind and body fitness for life. Retrieved from http://www.longlastingmemories.eu/sites/default/files/LLM_D1.4_final_report_public_v2.2doc.pdf

- Behm, L., Eklund, K., Wilhelmson, K., Zidén, L., Gustafsson, S., Falk, K., & Dahlin-Ivanoff, S. (2016). Health promotion can postpone frailty: Results from the RCT elderly persons in the risk zone. Public Health Nursing, 33(4), 303–315. doi: 10.1111/phn.12240

- Bonnefoy, M., Boutitie, F., Mercier, C., Gueyffier, F., Carre, C., Guetemme, G., … Cornu, C. (2012). Efficacy of a home-based intervention programme on the physical activity level and functional ability of older people using domestic services: A randomised study. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 16(4), 370–377. doi: 10.1007/s12603-011-0352-6

- Cadore, E. L., Casas-Herrero, A., Zambom-Ferraresi, F., Idoate, F., Millor, N., Gómez, M., … Izquierdo, M. (2014). Multicomponent exercises including muscle power training enhance muscle mass, power output, and functional outcomes in institutionalized frail nonagenarians. Age, 36(2), 773–785. doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9586-z

- Cameron, I. D., Fairhall, N., Langron, C., Lockwood, K., Monaghan, N., Aggar, C., & Kurrle, S. E. (2013). A multifactorial interdisciplinary intervention reduces frailty in older people: Randomized trial. BMC Medicine, 11(1), 1–10. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-1

- Carrapatoso, S. M. G. (2015). Relationships of walking at individual, interpersonal and environmental levels among seniors (Doctoral dissertation). University of Porto, Portugal. Retrieved from https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/bitstream/10216/83109/2/122321.pdf

- Carvalho, J., Marques, E., Soares, J. M., & Mota, J. (2010). Isokinetic strength benefits after 24 weeks of multicomponent exercise training and a combined exercise training in older adults. Ageing Clinical and Experimental Research, 22(1), 63–69. doi: 10.1007/BF03324817

- Chan, D.-C. D., Tsou, H.-H., Yang, R.-S., Tsauo, J.-Y., Chen, C.-Y., Hsiung, C. A., & Kuo, K. N. (2012). A pilot randomized controlled trial to improve geriatric frailty. BMC Geriatrics, 12(58), 1–12.

- Clegg, A., Barber, S., Young, J., Iliffe, S., & Forster, A. (2014). The Home-based Older People’s Exercise (HOPE) trial: A pilot randomised controlled trial of a home-based exercise intervention for older people with frailty. Age and Ageing, 43(5), 687–695. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu033

- Clegg, A., Young, J., Iliffe, S., Rikkert, M. O., & Rockwood, K. (2013). Frailty in elderly people. The Lancet, 381(9868), 752–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9

- Cohen, H. J., Feussner, J. R., Weinberger, M., Carnes, M., Hamdy, R. C., Hsieh, F., … Lavori, P. (2002). A controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. New England Journal of Medicine, 346(12), 905–912. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa010285

- Collard, R. M., Boter, H., Schoevers, R. A., & Voshaar, R. C. O. (2012). Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: A systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(8), 1487–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x