ABSTRACT

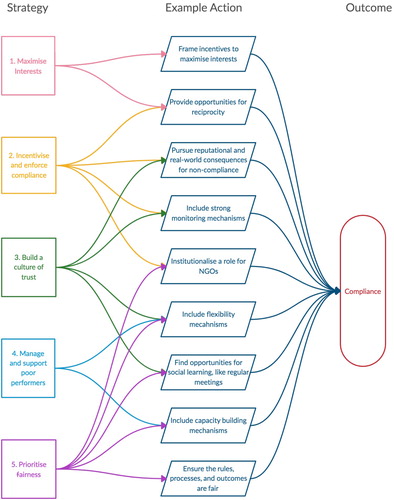

In 2015, 196 countries boldly committed to address global antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Now, five years later, progress reports suggest the implementation of AMR activities is vastly below what was initially promised. The challenge of overcoming the ‘commitment-compliance gap’ is not unique to AMR and is common in other areas of international politics. Global health policymakers can therefore learn from theories of international relations and experience in other sectors. We reviewed international relations scholarship to generate five hypotheses for why states might comply or not comply with their global commitments. We then conducted a public policy analysis of three past international agreements on biological diversity, climate change, and nuclear weapons to test these hypotheses and identify lessons for encouraging country compliance with global health agreements, with specific application to global AMR policies. To bridge the commitment-compliance gap, international leaders should: (1) frame incentives to maximise interests for action; (2) pursue enforcement mechanisms to induce state behaviour; (3) emphasise building a culture of trust by providing mutual assurance for action; (4) include mechanisms for managing poor performers; and (5) find opportunities for continual social learning. Agreements should be designed with flexibility, data sharing, and dispute settlement mechanisms and provide financial and technical assistance to states with less capacity to deliver.

Introduction

International agreements are instruments that states use to achieve common goals or collective purposes based on mutual dependence. For example, states might have a collective action problem to solve, or a shared condition, as is the case when establishing human rights treaties. When states make agreements in global health, moreover, they are essentially agreeing to enact a global population health intervention – that is, a coordinated response at the global level to improve and protect population health around the world. Agreements between states can take many forms. The strongest way that states can show their commitment is with legally binding treaties, but other forms of agreements include resolutions made in international plenary bodies and even diplomatic promises (Hoffman, Røttingen, et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b). One challenge is that states do not always comply with their commitments.

The gap between what states promise and what they actually deliver is a common governance challenge in international politics. Global health is not immune to this phenomenon. Take, for instance, the global response to antimicrobial resistance (AMR), known to be one of the greatest health challenges of our time (WHO, Citation2020). AMR occurs when microbes, like bacteria, become resistant to the antimicrobial substances we depend upon to stop their spread, such as antibiotics. AMR diminishes antimicrobial effectiveness – a limited open-access global common-pool resource – through evolutionary processes that are accelerated by the social overuse, misuse, and abuse of antimicrobial medicines in humans, animals, agriculture, and the environment (Rogers Van Katwyk, Giubilini, et al., Citation2020). To address the threat of AMR, a ‘tripartite’ of United Nations (UN) institutions – the World Health Organization (WHO), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) – strategically aligned their efforts in 2010 and created a Global Action Plan on AMR in 2015 to coordinate action at the global level (WHO et al., Citation2010; WHO, Citation2015). In response, all 196 WHO member states agreed to create bold multi-sectoral national action plans to address AMR (WHO et al., Citation2018). As recently as 2016, the world reaffirmed its commitment to address AMR at a special high-level meeting of the United Nations General Assembly.

Despite the threat posed by AMR and several international agreements to enact ambitious AMR policies, there is still much to be done to address AMR globally. The WHO, FAO, and OIE’s tool to monitor national-level progress on AMR – an annual self-assessment survey first conducted in 2018 – reveals limited progress on implementing much needed AMR policies, concentrated in specific sectors and regions of the world (WHO et al., Citation2018). This limited progress indicates that the current global response is inadequate (IACG, Citation2019). To address this shortcoming, the international community needs to focus its attention on deepening cooperation among states by supporting the concerted implementation of national AMR policies (Hoffman, Caleo, et al., Citation2015). The international community can improve the way that it supports collective action among states by designing better global governance mechanisms to help states fulfil their ambitious promises (Hoffman, Røttingen, et al., Citation2015a).

In light of the danger presented by many global health challenges including AMR, addressing this governance challenge is of urgent concern. The challenge now is identifying the strategies that the UN, its agencies, and leaders can use to encourage and support states to comply with what they have already committed to do. While international law can provide a powerful mechanism through which to achieve compliance on much needed AMR policies (Behdinan et al., Citation2015; Rogers Van Katwyk, Weldon, et al., Citation2020), and while an international treaty on AMR may be appropriate to strengthen the mechanisms by which the international community can hold states accountable (Hoffman, Røttingen, et al., Citation2015b; Rogers Van Katwyk, Giubilini, et al., Citation2020), neither a treaty nor other international legal mechanisms guarantee compliance in the context of the anarchical international system, which lacks an authoritative enforcement body. This means that regardless of its form, stewards of any ongoing and future AMR agreements – indeed all global health agreements – have to overcome the ‘commitment-compliance gap’ in global health politics between what states promise to do and what they actually deliver. Bridging this gap requires motivating states to fulfil their commitments and comply with their international agreements (von Stein, Citation2017). There is an urgent need to bridge this gap in global health because global population health interventions made in the form of international agreements will only be effective insofar as states actually comply with them.

There are many other areas in international politics that deal with the same challenge of bridging the commitment-compliance gap. Indeed, there is a vast research literature analyzing those experiences. More specifically, international relations (IR) is a field of social inquiry devoted to studying the behaviour of states in the global political system and has a rich tradition of studying international agreements, cooperation, and global collective action (Paxton & Youde, Citation2019). By looking to international relations scholarship, we can translate its theories and identify practical recommendations for overcoming this global governance challenge in global health (Andresen & Hoffman, Citation2015). This study attempts to apply lessons learned from international relations theory and a select number of empirical cases in international relations to the commitment-compliance gap in global health, with specific application to AMR.

We used IR theory to analyze various explanations for why the commitment-compliance gap exists and how to overcome it, surrounding our discussion on the current international system characterised by sovereign states in a context of anarchy. We focused on three international relations theories – realism, liberalism, and constructivism – for their problem-solving focuses and their collective reflection of a familiar political science framework privileging the role of ideas (constructivism), interests (realism), and institutions (liberalism) in political decision-making. We then conducted a public policy analysis to test the various explanations for why states comply with their international agreements. We drew on three empirical case studies of international agreements that addressed problems similar to AMR, specifically the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, and the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. Within these case studies, we identify strategies that were employed to encourage and support state compliance with their international commitments.

Sovereignty and anarchy in international relations theory

When two parties enter into a domestic agreement, they can depend upon the state to enforce the contract and hold others accountable to their commitments. The state, in this situation, acts as an impartial judge and enforcer with the coercive ability to compel parties to act or punish parties for any transgressions. Unfortunately, no such entity exists at the international level. Instead, individual states represent the highest form of sovereign political authority. This means that all states, regardless of size, population, wealth, or military capability, exercise the right to wield authoritative power over a given political community within their defined territorial boundary. It further means that states have the sovereign right of non-interference in their domestic affairs and the responsibility, among other things, for promoting domestic security, the rule of law, a stable economy, and national health policies.

The right of sovereignty produces another important concept in international relations. Since every state retains the right of sovereignty, the international system of sovereign states exists in a condition of anarchy. That is, a situation wherein there exists no supreme authority higher than the state with the coercive ability to enforce a common rule of international law. Although there are many important international organisations and institutions that often influence states, the power of those institutions depends upon the voluntary agreement or association of sovereign states, who upon joining retain their sovereignty – as well as their sovereign right to disassociate with those institutions if they so desire.

The nature of the international system, characterised by the existence of sovereign states in a context of anarchy, poses one of the most challenging obstacles to global health governance and lies at the heart of the commitment-compliance challenge in global health (Schrijver, Citation2016). Considering the challenges that arise in this context, different international relations theories provide different perspectives on compliance based on their interpretation of the consequences that follow from the nature of the international system. We draw on realism, liberalism, and constructivism to generate five hypotheses for why sovereign states might comply with their agreements under a condition of international anarchy.

Realism

The first hypothesis (H1) is states will only cooperate and comply with agreements that address existential threats. This hypothesis comes from realism, one of the oldest ways to approach the issue of state behaviour under anarchy. Realists view states as unitary actors with their own self-defined interests, who act rationally in order to achieve their own desired ends. When states are seen as unitary actors, it is intuitively appealing to generate ideas about how they might act by considering them as individuals. The most famous thought experiment considering the question of how individuals might act under anarchy comes from Thomas Hobbes’s 1651 book Leviathan, which argues that without a supreme political body to enforce the rule of law, individuals exist in condition of generalised uncertainty where they can never be truly sure of their own safety and must take it upon themselves to ensure and protect their own survival. When translated to the international, this view focuses on the real-world constraints, abilities, and interests of states, who exist in a self-help anarchical system and are therefore preoccupied with matters related to their interests defined as power (Morgenthau, Citation1972).

Liberalism

Instead of arguing that anarchy reinforces a self-help international system, liberalism suggests that cooperation can ultimately overcome anarchy. Suggesting that states can cooperate sincerely, however, does not mean that they will automatically comply. Following this logic, a second hypothesis (H2) is that agreements should include mechanisms to induce state behaviour like arrangements for reciprocity, reputational consequences for good and bad behaviour, and a role for NGOs, which can help compel states by mobilising pressure within domestic civil societies. Liberals admit that states still: act to realise their own interests which may at times differ from the interests of others or the international community; will not willingly sacrifice more to the collective good than is required; and will avoid situations where collective agreements disproportionately disadvantage them (Chayes & Chayes, Citation1993). States can also face many incentives to not comply, necessitating the need for inducement measures. Certain ‘enforcement’ elements can be built into institutions to nudge states towards compliance (Keohane, Citation1992). Put differently, this view suggests that states can be compelled to comply when institutions raise cost of noncompliance (von Stein, Citation2017).

Since states are sovereign in the anarchical international system, though, they are the ones who ultimately pick the incentives and penalties for compliance. A third hypothesis (H3), therefore, is that when states do not trust others to fulfil their commitments, they will opt for stricter enforcement mechanisms, but when they do not trust themselves to meet their commitments, they will opt for less ambitious minimum targets and weaker enforcement mechanism (Raustiala, Citation2005). As states negotiate and adopt agreements holistically, they can choose not to enter into agreements when they perceive a high risk of incurring penalties for not meeting their commitments; therefore, if they do not trust themselves to live up to the requirements, they will not enter into the agreement in the first place, or they will attempt to reduce the strictness of the agreement. Conversely, when states have a strong interest in achieving the goal of the agreement and ensuring that others are meeting their commitments they will opt for stronger obligations and enforcement measures.

When institutions impose an obligation on states, though, many states are often required to enhance their capacity for action, which can require technical and administrative improvement at the domestic level (Slaughter & Alvarez, Citation2000). Therefore, a fourth hypothesis (H4) is that agreements should include flexibility and strong dispute mechanisms, be transparent, and provide financial and technical assistance to states that require assistance in improving their domestic capacity to enact required policies. For example, sometimes states do not comply with international agreements because of obstacles like technical or financial setbacks at the domestic level (von Stein, Citation2017). Indeed, many states have identified technical, administrative, and resource challenges to enact much needed AMR policies (WHO et al., Citation2018). These mechanisms, however, need to be transparent to avoid the potential for states to abuse them. Financial and technical assistance should also be met with flexibility mechanisms to allow the rules to bend without breaking (Koremenos et al., Citation2001). Flexibility mechanisms like the ability to trade, transfer, or borrow targets, permits states who may have fallen behind to still partake in the agreement, while addressing their obstacles with the assistance of technical or financial support in the meantime.

Constructivism

Constructivism places a central emphasis on norms and ideas in international politics and approaches anarchy differently than liberalism and realism. Paying attention to the role of norms, a fifth hypothesis (H5) is that states comply when they perceive the rules, processes, obligations, and governance of international agreements as fair. Mechanisms for continual social learning, such as regular meetings, data sharing, and open negotiations, can improve trust and provide assurance by creating institutions governed by principles of fairness and norms of good faith and genuine willingness for cooperation. The emphasis on social learning stems from the idea that states are not inherently or necessarily selfish or cooperative, but instead learn expectations of behaviour from each other and develop a tendency to either cooperate or act selfishly based on their experience with other states in ongoing processes of interaction. This idea comes from the view that there is nothing about anarchy that necessarily means states are in a situation of self-help. Instead, ‘anarchy is what states make of it’ (Wendt, Citation1992). Put differently, the norms of cooperation or self-help that govern politics under anarchy are constructed by the actions of states. In this view, factors like state identity and principles of international society like fairness and the rule of law drive states to comply (Bull, Citation1966). This view emphasises how legitimacy can improve compliance by heightening a sense of moral obligation or duty (Fisher, Citation1981).

Methods

To test whether or not these factors could encourage compliance in global health, we looked at three purposively selected empirical case studies of high compliance agreements that are similar to AMR. AMR is unique in its bio-social complexity (Rogers Van Katwyk, Giubilini, et al., Citation2020), but we can learn lessons from past collective action problems that share similar characteristics. Unlike other health issues such as infectious disease management, one of the most prominent characteristics of AMR is that it presents a global common-pool resource challenge. We identified biodiversity management, climate change, and the use of nuclear technology as sharing this essential characteristic with AMR and therefore similar enough such that we could draw lessons. We selected three agreements in these areas for our empirical cases based on their high levels of compliance, their high-profile nature, and their seminal role as watershed agreements in their respective domains.

Case selection

First, in the domain of biodiversity management, we selected the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) of 1993. As a treaty directed at managing an international common-pool resource, the CBD identifies key challenges that closely resemble the challenges posed by AMR. These include ensuring sustainable access while simultaneously conserving the existing resource, and sharing responsibilities for, and benefits from, innovation (Hoffman & Outterson, Citation2015; United Nations, Citation1993).

Second, in the domain of climate change, we selected to the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The global response to climate change, like AMR, is an attempt to protect a global common-pool resource by mitigating the anthropogenic contributions to a natural process. Like AMR, both climate change and biodiversity pose long term and distant threats typically viewed as low priorities compared to more salient security issues.

And finally, although they are not very similar on the surface, there are some key similarities between AMR and nuclear technology use that enable us to draw lessons. For example, both represent a human made common-pool resource; that is, one that is created by human technology, but whereby the use of that very technology potentially destroys the common pool. Both AMR and nuclear technology use also represent a ‘weakest-link’ characteristic since a nuclear accident anywhere poses severe threats everywhere, just as the emergence of a resistant pathogen somewhere has potential implications everywhere. Finally, while the NPT bans the proliferation of nuclear weapons, it highlights the right to the peaceful use of nuclear technology (United Nations Office for Disarmament, Citation1970). The NPT’s attempt to balance the need for expanding the appropriate use of nuclear technology while banning inappropriate use reflects the challenge in AMR to expand access to effective antimicrobials while simultaneously reducing the future risk of resistance.

Case analysis

Each individual case was analysed to assess whether certain factors contributed to the success of the agreement in achieving high levels of compliance. High compliance is defined as a situation where the actual behaviour of most, if not all states are in full or close to full conformity with the behaviour prescribed by the international agreement. The goal of the analysis was to see what variables identified by the theory section could explain compliance, looking at whether there were certain features predicted by the theory that helped achieve the high levels of compliance in the cases. We looked specifically for key factors related to interests, ideas, and institutional design elements of these international agreements that could encourage state compliance with global AMR efforts. Official treaty documents, official treaty reports, and secondary sources were used to describe the features of each international agreement. Policy and historical analyses of each case were used to determine whether certain elements led to the success of each agreement.

Results

Case 1: The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) 1993

CBD opened for signatures 5 June 1992 and entered into force 29 December 1993. There are currently 193 parties to the convention, however, the USA did not ratified the agreement because the regulations contained in the CBD posed difficult challenges for the competitive and fragmented US legal system and conflicted with prevailing domestic regulations and patterns of federal-state government relations (Raustiala, Citation1997).

CBD aims to address the conservation of biodiversity, a concern pushed by high-income countries (HICs); sustainable use, which was pushed by low- and lower-middle-income countries (LICs and LMICs) concerned about fair access to these resources for sustainable development; and a common concern for fair resource and benefit sharing from innovation in genetic technology (Harrop & Pritchard, Citation2011). By accommodating the concerns of HIC, LMICs, and LICs, the final convention was able to craft an incentive structure to manage competing interests. Additionally, its negotiation format identified fairness and inclusion as priorities (H5) by inviting a range of actors including NGOs and indigenous groups from an early stage (H2) (Boisvert & Vivien, Citation2012). The negotiations were conducive to finding opportunities for compromise and reciprocity (H2) by creating an inclusive intergovernmental working group, which met seven time prior to the adoption of the adoption of the agreement (H5) (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Citation2001).

States pledge their own nationally determined contributions, which allows each country to tailor its contribution to its own unique circumstances (United Nations, Citation1993). In hindsight, this method permitted states to make lacklustre and unambitious contributions. CBD was initially proposed with strong coercive powers to enforce its mandate, but these measures were softened during the negotiation and adoption of the convention because of a collective fear of facing severe punishment for poor performance (H3) (Harrop & Pritchard, Citation2011). As such, one of the only tools at the disposal of the secretariat is to identify and call out poor performing states which offers reputational sanctions through a process commonly called ‘naming and shaming’ (H2). Even with the legal requirement to present and report progress on implementation and these reputational consequences, the enforcement mechanisms in CBD are not as strong as they need to be to ensure that country level action effectively addresses the challenge of biodiversity.

Despite this shortcoming, the convention created several institutions that are able to mobilise activities to coalesce compliance (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Citation2014). These institutions include an annual conference of the parties (H5), a centralised secretariat, a scientific and technical body to review advancements in knowledge, and a separate compliance committee to review country pledges and activities (H2, H4) (United Nations, Citation1993). CBD also included a funding mechanism for the purpose of aiding developing countries in meeting their commitments (H4). The rules for how the fund is financed and allocated is set by the conference of the parties. This system permits the funding rules to continually reflect country status and capabilities while allowing for an ongoing review, evaluation, and revision of the funding system and its effectiveness (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Citation2001).

Case 2: The Kyoto Protocol to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change

Signed in 1997 and in effect as of 2005, the Kyoto Protocol intends to address climate change caused by human greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. 192 states ratified the agreement, which has high levels of compliance since nearly all member parties acted in accordance with the protocol and exceeded their emissions targets (Shishlov et al., Citation2016). It should be noted, however, that the USA did not implement the protocol and Canada withdrew from it in 2011 (Grubb, Citation2016; Oberthür & Lefeber, Citation2010). Some suggest that the USA did not ratify because of the agreement’s incompatibility with domestic institutions and interests, including concerns for its effects on the US economy (H1) (Hovi et al., Citation2012). As well, Former President George W. Bush suggested that the USA did not ratify the agreement because it was incomplete and unfair, supporting the notion that states prefer agreements they perceive as fair (H5). Interestingly, Bush pointed to the agreement’s flexibility mechanisms, which are identified by others as mechanisms that encourage compliance (H4). On the other hand, Canada admitted to withdrawing from the agreement in 2011 because it realised it could not meet its imposed targets and wanted to avoid a penalty for non-compliance. Canada’s behaviour strongly supports the claim that states can and will disassociate with agreements when there is a real chance that they might incur a penalty (H3) (van Zuydam, Citation2011). Both actions, however, were poorly received by the international community and both the USA and Canada’s reputations were perceived to suffer from their behaviour (H2).

The substantive requirement of the Kyoto Protocol is based on the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities. This means that all states have an obligation to address climate change, but not all states have the responsibility to act in an equal manner. The principle is based on the recognition that HICs have historically contributed more to climate change and currently are in a different position than LICs and LMICs to mitigate climate change. Common but different responsibilities is regarded as a contributing factor to the success of the agreement (H4), despite USA’s grievance that this division of responsibilities was unfair (H5) (Brunnée & Streck, Citation2013).

A country’s failure to meet their substantive requirement triggers the Kyoto’s comprehensive compliance mechanism. Specifically, the Kyoto protocol has two ways that it can encouraging compliance: an enforcement branch and a facilitative branch. The enforcement branch is responsible for deciding whether certain penalties are imposed for non-compliance, but, like CBD, relies mostly on naming and shaming to sanction non-compliant states (H2). The facilitative branch is responsible for providing assistance and advice to parties who may be struggling with implementation. Both branches consider individual country circumstance, flexibility arrangements, and common but differentiated responsibilities when considering how best to respond to non-compliance (H4) (Nentjes & Klaassen, Citation2004; United Nations, Citation2020).

The Kyoto protocol includes a funding mechanism aimed at supporting developing countries in reaching their targets. The funding mechanism is set by the conference of the parties, which allows a continual review of funding rules. The inclusion of flexibility mechanisms, like non-binding provisions for LMICs and a market based emissions trading system (H4), and the incorporation of NGOs in negotiations and compliance procedures, which permits them to submit reports and information during compliance hearings (H2), are also used to explain the high levels of compliance observed (Gulbrandsen & Andresen, Citation2004; Shishlov et al., Citation2016).

Case 3: Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) was signed in 1968 and has been in force since 1970. 190 states are parties to the NPT, which has three pillars relating to the control of nuclear technology: (1) non-proliferation of nuclear weapons; (2) disarmament; and (3) the sovereign right to peacefully use nuclear technology.

The NPT has experienced high compliance without centralised institutional mechanisms (Mallard, Citation2014; Popp, Citation2017). The authority of the NPT is decentralised and various responsibilities are spread amongst the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the United Nations Security Council. A key component in the NPT was its trust building verification mechanisms. The NPT’s verification mechanism requires all parties that use nuclear technology to accept continual monitoring and evaluation of their activities, as well as onsite inspections and ad hoc visits from IAEA delegations to ensure that they are not violating the terms of peaceful nuclear technology use (International Atomic Energy Aagency, Citation2019). The strong verification mechanisms of the NPT are possible due to the ability of the NPT to mobilise a strong desire to ensure that states are complaint (H1, H3) (Gottemoeller, Citation2015; Lutsch, Citation2017).

The verification mechanism, carried out by the IAEA, makes NPT a unique case where states are willing to sacrifice important aspects of their sovereignty due to the extraordinary nature of the challenge of nuclear technology. I.e. the mandate that IAEA must have access to domestic facilities means that states cannot exercise the right to deny inspections from the international community. In return, the strict verification measures provide states an added level of assurance that others are complaint, thereby improving the overall confidence in the NPT. The NPT has additionally been successful in acting as a forum that has addressed emerging issues related to nuclear weapons in international affairs for over 50 years (H5) (Müller, Citation2017; Popp, Citation2017).

Discussion

Principal findings

All hypotheses were confirmed in one way or another in the cases, which each case corroborating several of the hypotheses. Hypothesis 1 was noted in the NPT where states were able to mobilise strong support for strict monitoring and verification mechanisms. The suggestion that states are ambivalent toward non-existential issues would explain why AMR did not crystalise as an issue on many global agendas until it was recognised as a threat to security (Chandler, Citation2019). States may be required to sacrifice aspects of their sovereignty and relinquish some control of activities and flow of information over their domestic AMR activities. The challenge is that achieving this level of commitment would require a general consensus that AMR is a pressing enough security threat for these strict measures.

Even with the USA absent in CBD and USA and Canada absent in Kyoto, several important lessons emerged. The CBD and Kyoto Protocol’s ability to craft incentive structures that offered opportunities for reciprocity and compromise between HIC, LICs, and LMICs, and their institutionalised inclusion of NGO’s and other civil society voices corroborated hypothesis 2. Evidence of hypothesis 3 also emerged in all three cases. For instance, CBD was stripped of its strong enforcement mechanisms during implementation and states have been rather unambitious with their biodiversity targets; in Kyoto, Canada withdrew from the agreement to avoid receiving a penalty for failing to meet its target. Hypothesis 4 also received strong support from Kyoto and CBD. Both treaties established several focused bodies with clearly delineated responsibility including compliance monitoring and dispute settlement mechanisms. Additionally, both CBD and Kyoto’s financing and flexibilities mechanisms were instrumental in the successful levels of compliance in both agreements. Finally, with respect to hypothesis 5, all three cases included some form of a regular meeting such as a conference of the parties which permitted regular data sharing, opportunities to update rules and targets, and permitted an ongoing dialogue amongst relevant actors.

In many ways, the factors identified by the different theories seemed to complement each other, and the cases were able to mobilise compliance by including a combination of the factors identified by the theories. The inclusion of flexibility and financing mechanisms, while instrumental in achieving compliance also reinforced notions of fairness, and crafting venues for negotiating reciprocity and institutions for compliance monitoring reinforced a culture of trust. Additionally, the inclusion of inducements like penalties for non-compliance may help align incentives for states to comply, but without the availability of support can be counterproductive especially for health challenges like AMR that display a weakest link characteristic. The relationship between these last two features suggest that both must be present in any well-crafted global health agreement ().

Table 1. Summary of findings.

Implications for improving global health policy

International agreements in the realm of global health can be thought of as global population health interventions. Any policy made and adopted at the international level will only be effective insofar as states are willing to implement their recommendations. To help support states in complying with their global health commitments and implementing their national AMR policies, stewards of any ongoing or future agreement should consider the following five lessons emerging out of the above analysis.

First, incentives for action should be framed to maximise their resonance with state interests. States have various interests ranging from selfishly defined military and economic security to altruism, which can be exploited by framing AMR to align with different interests (Mendelson et al., Citation2017). Second, institutions should be crafted to raise the cost of non-compliance and decrease the cost of compliance. Prioritising effectiveness; including reputational and real-world consequences for good and bad behaviour; institutionalising a role for NGOs; and addressing domestic and international obstacles for compliance can help achieve this goal. Third, agreements should emphasise a culture of trust by providing mutual assurance for action. Fourth, agreements should provide technical and financial assistance to poor-performing states fairly and judiciously with strong dispute settling and flexibility mechanisms. It is likely that in global health cases like AMR, states do not trust themselves to meet hard targets and will therefore resist strong monitoring, ambitious targets, and penalties for non-compliance. The challenge of most global health issues including AMR, however, is such that monitoring is essential to the response. An agreement will therefore need to motivate enough support to include strong monitoring and verification mechanisms which will require striking a balance between enforcement elements (i.e. penalties and inducements) and management elements (i.e. financial and technical support, transparency, and flexibility). Finally, agreements should include processes for social learning like regular meetings of relevant parties. Data sharing and transparency mechanisms, and including NGOs in negotiation and compliance procedures can also promote trust and build culture of sincere cooperation ().

Strengths and limitations

This study has four main strengths. First, this study used cases that have been widely studied, providing an abundance of literature to nuance the findings. Drawing upon highly studies cases allowed us to benefit from an enormously rich literature that has, throughout time, developed sophisticated understandings and applications of concepts related to the issue of compliance. Second, the variety of theories permitted the inclusion of vast literatures and the diversity of cases allowed us to triangulate our findings across a wide range of domains. Third, the expansive literature transcended several disciplinary boundaries, which permitted us to draw interdisciplinary insights from several unique political experiences across different issue areas in international relations. Fourth, the study was able to distil the findings into pragmatic and actionable lessons for those wishing to enhance collective action on international agreements, including ongoing and future AMR agreements.

This study has three main limitations. First, having only analysed agreements that were successful, the study could have missed cases where the factors herein argued to encourage compliance are present with low levels of compliance. Second, if states are more likely to agree to activities that they are willing to comply with in the first place, this could mean there are instances where compliance is present without the presence of the factors identified by this study (Downs & Rocke, Citation1995). Third and finally, there could also be factors that explain compliance which are unobservable to the study design. Despite these potential limitations, however, the lessons identified are still valuable as a means to consider additional action that could supplement and enhance the global response to AMR.

Future research directions

This study provided some insight to political challenges within global health by applying theories, concepts, and lessons from empirical case studies in international relations. In so doing, this study provides further evidence of the deep potential for interdisciplinary learning between global health and international relations. It revealed that, although there are many political obstacles that can prevent cooperation and compliance – even when problems are imminent – certain strategies can help spur collective action. Since these problems are pervasive, we can use theory and case studies to enhance our critical understanding to address these present issues, which can help ongoing efforts to solve today’s greatest challenges.

Future research in global health would do well to continue looking to concepts, theories, and cases from international relations for relevant insights on improving global health policymaking. For instance, the commitment-compliance gap that this study investigated is not the only governance shortfall apparent in global health. Future research could identify other governance challenges in global health and look to other sources in international relations to better understand these problems and how to solve them. Four of the many governance challenges that remain to be addressed in global health include: first, a surveillance challenge, which requires enhancing global monitoring activities and harmonising data reporting while respecting state sovereignty and human rights; second, a sectoral challenge, which requires coordinating and distributing responsibilities for global health action amongst human health, animal health, agriculture, and environmental sectors; third, an actors challenge, which requires addressing the relationship amongst industry, NGOs, private citizens, states, publics, and international organisations in global health politics; and finally a scalar challenge, which requires analyzing the links and patterns of convergence and divergence among individual, community, national, international, global, and planetary scales in global health (Frenk & Moon, Citation2013). Finally, we still need to know the specific challenges impeding the implementation of national AMR policies so that responses can be specifically tailored to each unique circumstance.

Acknowledgements

We thank Justin Parkhurst and Susan Rogers Van Katwyk for feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript. We also thank the anonymous reviewers of the journal for their helpful and constructive comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andresen, S., & Hoffman, S. J. (2015). Much can be learned about addressing antibiotic resistance from multilateral environmental agreements. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 43(Supplement 3), 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlme.12274

- Behdinan, A., Hoffman, S. J., & Pearcey, M. (2015). Some global policies for antibiotic resistance depend on legally binding and enforceable commitments. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 43(Supplement 3), 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlme.12277

- Boisvert, V., & Vivien, F.-D. (2012). Towards a political economy approach to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 36(5), 1163–1179. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bes047

- Brunnée, J., & Streck, C. (2013). The UNFCCC as a negotiation forum: Towards common but more differentiated responsibilities. Climate Policy, 13(5), 589–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2013.822661

- Bull, H. (1966). International theory: The case for a classical approach. World Politics, 18(3), 361–377. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/2009761

- Chandler, C. I. R. (2019). Current accounts of antimicrobial resistance: Stabilisation, individualisation and antibiotics as infrastructure. Palgrave Communications, 5(53). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0263-4

- Chayes, A., & Chayes, A. H. (1993). On compliance. International Organization, 47(02), 175–205. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300027910

- Downs, G. W., & Rocke, D. M. (1995). Optimal imperfection?: Domestic uncertainty and institutions in international relations. Princeton University Press.

- Fisher, R. (1981). Improving compliance with international law. University Press of Virginia.

- Frenk, J., & Moon, S. (2013). Governance challenges in global health. New England Journal of Medicine, 368(10), 936–942. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1109339

- Gottemoeller, R. (2015). The nuclear non-proliferation treaty at 45. New Zealand International Review, 40(5), 6–8. https://doi.org/10.2307/48551800

- Grubb, M. (2016). Full legal compliance with the Kyoto Protocol’s first commitment period – some lessons. Climate Policy, 16(6), 673–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2016.1194005

- Gulbrandsen, L. H., & Andresen, S. (2004). NGO influence in the implementation of the Kyoto Protocol: Compliance, flexibility mechanisms, and sinks. Global Environmental Politics, 4(4), 54–75. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2004.4.4.54

- Harrop, S. R., & Pritchard, D. J. (2011). A hard instrument goes soft: The implications of the Convention on Biological Diversity’s current trajectory. Global Environmental Change, 21(2), 474–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.014

- Hoffman, S. J., Caleo, G. M., Daulaire, N., Elbe, S., Matsoso, P., Mossialos, E., Rizvi, Z., & Røttingen, J.-A. (2015). Strategies for achieving global collective action on antimicrobial resistance. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 93(12), 867–876. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.15.153171

- Hoffman, S. J., & Outterson, K. (2015). What will it take to address the global threat of antibiotic resistance? The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 43(2), 363–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlme.12253

- Hoffman, S. J., Røttingen, J.-A., & Frenk, J. (2015a). International law has a role to play in addressing antibiotic resistance. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 43(Supplement 3), 65–67. https://doi:10.1111/jlme.12276

- Hoffman, S. J., Røttingen, J.-A., & Frenk, J. (2015b). Assessing proposals for new global health treaties: An analytic framework. American Journal of Public Health, 105(8), 1523–1530. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302726

- Hovi, J., Sprinz, D. F., & Bang, G. (2012). Why the United States did not become a party to the Kyoto Protocol: German, Norwegian, and US perspectives. European Journal of International Relations, 18(1), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066110380964

- IACG. (2019). No time to wait: Securing the future from drug-resistant infections. The Interagency Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance. https://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/interagency-coordination-group/IACG_final_report_EN.pdf?ua=1

- International Atomic Energy Agency. (2019). IAEA safeguards overview: Comprehensive safeguards agreements and additional protocols. https://www.iaea.org/publications/factsheets/iaea-safeguards-overview

- Keohane, R. (1992). Compliance with international commitments: Politics within a framework of law. Proceedings of the ASIL Annual Meeting, 86, 176–180. https://doi:10.1017/S0272503700094593

- Koremenos, B., Lipson, C., & Snidal, D. (2001). The rational design of international institutions. International Organization, 55(4), 761–799. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081801317193592

- Lutsch, A. (2017). In favor of “effective” and “non-discriminatory” non-dissemination policy: The FRG and the NPT negotiation process (1962-1966). In R. Popp, L. Horovitz, & A. Wenger (Eds.), Negotiating the nuclear non-proliferation treaty: Origins of the nuclear order (pp. 36–58). Routledge.

- Mallard, G. (2014). Crafting the nuclear regime complex (1950–1975): Dynamics of harmonization of opaque treaty rules. European Journal of International Law, 25(2), 445–472. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chu028

- Mendelson, M., Balasegaram, M., Jinks, T., Pulcini, C., & Sharland, M. (2017). Antibiotic resistance has a language problem. Nature, 545(7652), 23–25. https://doi.org/10.1038/545023a

- Morgenthau, H. J. (1972). Politics among nations; The struggle for power and peace (5th ed.). Knopf.

- Müller, H. (2017). The nuclear non-proliferation treaty in Jeopardy? Internal divisions and the impact of world politics. The International Spectator, 52(1), 12–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2017.1270088

- Nentjes, A., & Klaassen, G. (2004). On the quality of compliance mechanisms in the Kyoto Protocol. Energy Policy, 32(4), 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4215(03)00154-X

- Oberthür, S., & Lefeber, R. (2010). Holding countries to account: The Kyoto Protocol’s compliance system revisited after four years of experience. Climate Law, 1(1), 133–158. https://doi.org/10.1163/CL-2010-006

- Paxton, N., & Youde, J. (2019). Engagement or dismissiveness? Intersecting international theory and global health. Global Public Health, 14(4), 503–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2018.1500621

- Popp, R. (2017). The long road to the NPT: From superpower collusion to global compromise. In R. Popp, L. Horovitz, & A. Wenger (Eds.), Negotiating the nuclear non-proliferation treaty: Origins of the nuclear order (pp. 9–36). Routledge.

- Raustiala, K. (1997). Domestic institutions and international regulatory cooperation: Comparative responses to the Convention on Biological Diversity. World Politics, 49(4), 482–509. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887100008029

- Raustiala, K. (2005). Form and substance in international agreements. The American Journal of International Law, 99(3), 581–614. https://doi.org/10.2307/1602292

- Rogers Van Katwyk, S., Giubilini, A., Kirchhelle, C., Weldon, I., Harrison, M., McLean, A., Savulescu, J., & Hoffman, S. J. (2020). Exploring models for an international legal agreement on the global antimicrobial commons: Lessons from climate agreements. Health Care Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-019-00389-3

- Rogers Van Katwyk, S., Weldon, I., Giubilini, A., Kirchhelle, C., Harrison, M., McLean, A., Savulescu, J., & Hoffman, S. J. (2020). Making use of existing international legal mechanisms to manage the global antimicrobial commons, identifying legal hooks and institutional mandates. Health Care Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-019-00389-3

- Schrijver, N. (2016). Managing the global commons: Common good or common sink? Third World Quarterly, 37(7), 1252–1267. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1154441

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. (2001). Handbook of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Earthscan Publications.

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. (2014). Global Biodiversity Outlook 4. https://www.cbd.int/gbo/gbo4/publication/gbo4-en-hr.pdf

- Shishlov, I., Morel, R., & Bellassen, V. (2016). Compliance of the parties to the Kyoto Protocol in the first commitment period. Climate Policy, 16(6), 768–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2016.1164658

- Slaughter, A.-M., & Alvarez, J. E. (2000). A liberal theory of international law. Proceedings of the ASIL Annual Meeting, 94, 240–249. doi: 10.1017/S0272503700055919

- United Nations. (1993). Convention on Biological Diversity. https://www.cbd.int/doc/legal/cbd-en.pdf

- United Nations. (2020). An introduction to the Kyoto Protocol compliance mechanism. United Nations Climate Change.

- United Nations Office for Disarmament. (1970). Treaty on the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. United Nations. https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/infcircs/1970/infcirc140.pdf

- van Zuydam, S. (2011). Canada pulls out of Kyoto Protocol. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/canada-pulls-out-of-kyoto-protocol-1.999072

- von Stein, J. (2017). Compliance with international law. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.81

- Wendt, A. (1992). Anarchy is what states make of it: The social construction of power politics. International Organization, 46(2), 391–425. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300027764

- WHO. (2015). Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/193736/9789241509763_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- WHO. (2020). Urgent health challenges for the next decade. https://www.who.int/news-room/photo-story/photo-story-detail/urgent-health-challenges-for-the-next-decade

- WHO, FAO, & OIE. (2010). The FAO-OIE-WHO collaboration.

- WHO, FAO, & OIE. (2018). Monitoring global progress on addressing antimicrobial resistance: Analysis report of the second round of results of AMR country self-assessment survey 2018.