ABSTRACT

Elections are the main instrument through which voters can exercise influence over public policy. However, the relationship between electoral outcomes and government policy performance is under-researched. In particular, little is known about the effect that the perceived narrowness of electoral victories has on expectations about incumbents’ policy behaviour. Drawing on the literature on electoral mandates and framing theory, we examine how the way in which election results are portrayed by the media affects citizens’ confidence that winners will enact their policy programmes, using the 2015 UK election as a case study. Based on a survey experiment conducted after the race, we find that victories depicted as narrow increased scepticism about the incoming government’s ability to deliver on its promises, contradicting normative theories of electoral competition. Instead, and consistent with mandate interpretations, subjects – especially less political knowledgeable ones – became more likely to trust in the government’s ability to fulfil its campaign pledges when the Conservative victory was presented as decisive. Besides shedding light on the link between the framing of election results and expectations about government performance, our results have potentially relevant implications for understanding how such expectations may affect actual policy-making and the enforcement of accountability.

Introduction

Normative theories of democracy contend that competitive elections help translate citizens’ preferences into government action. Ferejohn (Citation1986), for instance, argues that incumbents have incentives to implement the policies preferred by the electorate because of their fear of being replaced in the next election. To the extent that close elections provide a signal about the competitiveness of future races and induce greater uncertainty about officeholders’ re-election prospects, narrow electoral victories should encourage incumbents to enact the policies that got them into office and by which they will be retrospectively rewarded or punished (Hobolt and Klemmensen Citation2008; Vowles, Katz, and Stevens Citation2017). The threat of removal becomes less credible following less competitive elections yielding larger majorities for the winner, who may feel relatively safe from electoral punishment and thus less pressured to enact the policies promised to the citizenry.

An alternative perspective on the relationship between election results and government policy-making is posited by the mandate theory of elections (Grossback, Peterson, and Stimson Citation2006). In this view, tight races without a clear winner undermine the in-party’s power to deliver on its campaign commitments, as policy-making may become subject to a complex post-electoral bargaining process among multiple parties that could end up diluting the government’s programme (Powell Citation2000). In contrast, decisive victories resulting in unified partisan control over policy-making render it easier for incumbents to fulfil their manifesto pledges without the need to make policy compromises.

Although the relationship between the decisiveness of incumbents’ electoral victory and governments’ ability to fulfil their policy promises has been the subject of much theoretical debate, empirical studies on this issue are relatively scarce, and their findings remain largely inconclusive (Hobolt and Klemmensen Citation2008; Pickup and Hobolt Citation2015). Even less academic attention has been paid to the influence that public perceptions about the magnitude of the in-party’s victory exert on expectations about the government’s policy performance, even when such expectations can be as important in conditioning the behaviour of political actors as the actual electoral outcomes (Mendelsohn Citation1988; Shamir, Shamir, and Sheafer Citation2008). This paper aspires to bridge this gap in the literature, examining how alternative media interpretations about the decisiveness of the electoral victory affect people’s beliefs about the policy performance of incoming governments. To this end, we draw on framing theory and research on electoral mandates to analyse the results of a survey experiment conducted in the aftermath of the 2015 UK general election.

The 2015 British election makes an excellent case study to test whether – and to what extent – the way in which electoral victories are perceived or portrayed influences citizens’ confidence that incumbents will enact their policy programme. The Conservative Party victory on 7 May 2015 could be interpreted as “decisive”, having produced a majority against all expectations, but also – and equally credibly – as “narrow”, as such a majority was relatively small in historical terms and arguably left the incoming administration little room for manoeuvre. Indeed, whereas some press reports described the Tory majority as “slender” (BBC, May 8, 2015) or “slim” (The Independent, May 26, 2015), others depicted the result as a “crushing victory” (The Daily Mail, May 8, 2015) for David Cameron, conveying a “strong endorsement from the electorate” (The Telegraph, May 8, 2015). Different interpretations of the electoral outcome were accompanied by different readings of the policy implications of the new political landscape. At the same time that The Telegraph readers learned that the Prime Minister’s party would “have a free hand” to craft policy (The Telegraph, May 8, 2015), The Economist (May 9, 2015) reported that Cameron would find little support to push a divisive government programme.

During our experiment, conducted three weeks after the election, we presented subjects with news articles portraying the Tory victory as either decisive or narrow and estimated the effects of exposure to these competing descriptions – moderated by individuals’ political and attitudinal characteristics – on expectations about the government’s ability to honour its policy commitments. Our results show that individuals were significantly more prone to believe that the in-party would be able to implement its policy programme when the Conservative electoral victory was portrayed as decisive. By contrast, victories depicted as narrow never boosted subjects’ confidence that incumbents would deliver on their campaign promises. Altogether, our findings indicate that the mandate – rather than the normative or responsiveness – view of elections prevailed in the “voter’s eye” (Powell Citation2000, 7). The predominance of the mandate interpretation was particularly marked among least politically knowledgeable individuals, who were especially sensitive to the framing of the electoral outcome.

Electoral mandates and expectations about government policy-making: previous research and hypotheses

Scholars have long established that the competitiveness of elections affects citizens’ political behaviours and attitudes. Closer races are associated with higher turnout levels (Vowles, Katz, and Stevens Citation2017), better informed voters (Altheas, Cizmar, and Gimpel Citation2009), heightened media attention (Banducci and Hanretty Citation2014) and higher (perceived) electoral legitimacy (Birch Citation2008).

Besides affecting citizens’ political engagement and views about the quality of democratic processes, the closeness of elections – and, more specifically, the decisiveness or narrowness of incumbents’ victory – can also influence public expectations about incoming governments’ policy performance and, in particular, people’s confidence that elected officials will fulfil their policy pledges. In principle, one would expect a strong overlap between the preferences of the electorate and the policies enacted by the government. According to Powell (Citation2000), this should be especially true following elections with clear winners and large margins of victory. Such elections may be seen as providing officeholders with a mandate, i.e. a strong and clear message from the citizenry endorsing the winner’s programme and giving the in-party the policy-making resources to enact it.Footnote1

However, the actual achievement of a government majority and a large size advantage are necessary but not sufficient conditions for a mandate. As noted by Grossback, Peterson, and Stimson (Citation2006), mandates are also a matter of social construction and post-election interpretation. The way in which electoral outcomes are framed and communicated to the public plays a key role in forging expectations about what the winner can or cannot do. Therefore, narratives – especially media-driven ones – that succeed in persuading the citizenry that the in-party’s victory was decisive will be more effective in convincing the public opinion that the new government has been given a mandate – and the political power – to carry out its programme (Mendelsohn Citation1998; Shamir, Shamir, and Sheafer Citation2008).

In the context of the 2015 UK election, these arguments lead to the first hypothesis (H1) to be tested in our empirical analysis: exposure to narratives describing the electoral result as a “decisive” (“narrow”) Tory victory should render individuals more (less) likely to believe that the elected authorities will be able to deliver on their election promises.

This first hypothesis considers only the average effect of the (perceived) decisiveness of the winning party’s victory on expectations about the government’s ability to carry out its policy programme. Nevertheless, a vast body of research on framing theory and experimental public opinion suggests that relevant individual characteristics are likely to moderate these effects.

Firstly, party identification, acting as a “perceptual screen” (Campbell et al. Citation1960, 133), has long been shown to condition the way in which people process and evaluate political information. Consistent with this, the growing literature on partisan motivated reasoning, drawing on general theories of motivated reasoning (Kunda Citation1990), has established that individuals affiliated with a political party respond to new information by making it fit their prior beliefs in order to rationalise arriving at specific conclusions aligned with their partisan identity. Individuals tend to accept information that is congruent with their political views irrespective of its objective accuracy, but discard or discount that which challenges their biases (Druckman, Peterson, and Slothuus Citation2013; Bolsen, Druckman, and Cook Citation2014). Closely related to the focus of our investigation, Sances and Stewart (Citation2015) and Kernell and Mullinix (Citation2018) find that partisanship can colour the interpretation of information about elections and perceptions of electoral outcomes.

Applied to the 2015 UK election, the logic underlying motivated reasoning would lead us to expect supporters of the two major parties – Conservative and Labour – to be more responsive to information aligned with the electoral interests or narrative of their favoured party, and to dismiss information inconsistent with these views. That is, Conservative (Labour) identifiers should be more likely to accept frames portraying the Tory victory as “decisive” (“narrow”), and to downplay the opposite interpretation. Independents, in turn, should respond to information about the election result as “rational Bayesian updaters” (Lebo and Cassino Citation2007, 738), adjusting their expectations about government performance according to the messages they were exposed to. Combining H1 with the moderating influence of partisanship on treatment effects, we state our second hypothesis (H2): the positive impact of “decisive victory” frames on expectations about the government’s ability to deliver on its promises should be strongest among Conservatives and weakest among Labour partisans, with the effect for independents falling between these two extremes. By contrast, “narrow victory” frames will have a larger negative effect among Labour supporters than among independents, and should be least effective in swaying the beliefs of Conservative identifiers.

Hypothesis H2 focuses on independents and subjects affiliated with the incumbent and main opposition parties, as it is difficult to draw expectations about the moderating influence of partisanship for supporters of each of the other contestants of the 2015 election (UKIP, the Scottish National Party, the Liberal Democrats, etc.). Nonetheless, another version of the motivated reasoning argument is that perceptions about electoral outcomes and post-election attitudes depend not only on partisan identification, but on whether individuals voted for the party that won or for one of the “electoral losers” (Anderson et al. Citation2005; Kernell and Mullinix2018).Footnote2 Following a logic similar to that behind H2, subjects who voted for the Tories in 2015 should be prone to take “decisive” frames – which highlight the in-party’s ability to implement the policies these subjects endorsed at the polling booth – at face value, and to ignore information portraying the Conservative victory as “narrow”. The opposite would hold for participants who voted for any of the other contenders. Hence, hypothesis H3 states that the effect of “decisive victory” frames in boosting confidence that the government will enact its policy programme should be stronger for subjects who voted for the Tories than for those who cast a ballot for any of the other parties. By contrast, exposure to “narrow victory” frames will have a larger negative effect on expectations among “electoral losers” than among “winners”. Footnote3

Besides individuals’ partisan affiliations and vote choices, we expect the effect of news about the magnitude of Conservatives’ electoral victory to depend on the credibility subjects assign to the source of this information. Individuals tend to believe in the accuracy of information coming from journalists and outlets they trust (Miller and Krosnick Citation2000), and thus, will be willing to accept their interpretation of the electoral outcome. By contrast, subjects should be less prone to base their political judgments on stories coming from sources they deem unreliable or on interpretations they perceive as biased. Consequently, hypothesis H4 states that subjects’ opinions will be (less) more responsive to information about the decisiveness or narrowness of the Tory victory when it comes from a source they (dis)trust. This hypothesis is also in accordance with Druckman (Citation2001) and Baum and Gussin (Citation2004), who find that the probability of accepting or rejecting a message – and thus, the effectiveness of a frame – can hinge on the (perceived) reputation of the source, rather than on its content.

Finally, we expect subjects’ level of political knowledge or sophistication to intervene between the perceived decisiveness of the in-party’s victory and expectations about the government’s ability to fulfil its policy commitments. Krosnick and Kinder (Citation1990) note that higher levels of political knowledge reduce the novelty of new information and thus the impact this information has on the attitudes of more knowledgeable individuals. In our case, more sophisticated subjects were probably better informed about the outcome and implications of the 2015 election, so their opinions should be less malleable than those of less politically attentive individuals. Furthermore, drawing on Gomez and Wilson (Citation2001), “high sophisticates” should be better equipped to understand the complexity of the policy-making process and to recognise that, even if incumbents are willing to enact the policies they promised, their ability to do so may depend on other political and contextual factors besides the margins of victory. Therefore, holding the content of the message constant, we expect more politically sophisticated subjects to be less susceptible to framing effects than less knowledgeable individuals (H5).

It is worth noting that Miller and Krosnick (Citation2000), in contrast, argue that a relatively high degree of political expertise is required for individuals to be able to read beyond the explicit contents of a story, extract its fundamental implications, and incorporate them into their political judgments. Drawing on these authors, the opinions of more politically knowledgeable subjects should be more responsive to treatment than those of low sophisticates. We believe, however, that the association between the magnitude of the in-party’s victory and government policy performance is a quintessential example of what Gomez and Wilson (Citation2001, 900) denote as “proximal” or obvious causal attributions, which require relatively low cognitive skills. Hence, following Gomez and Wilson (Citation2001), H5 posits that low sophisticates are more likely to assume a direct link between the decisiveness of incumbents’ electoral victory and their policy actions than high sophisticates. That said, our empirical analysis allows assessing the relative validity of the two competing rationales in the aftermath of the 2015 UK election.Footnote4

Research design

To test these hypotheses, we conducted an experiment embedded in an online survey fielded by the market research firm Research Now between 28 May and 1 June 2015. The pool of respondents consisted of 1,830 British citizens.

The first part of the survey, common to all participants, gathered information about their partisan affiliation, electoral participation, vote choice, levels of political interest, trust in the press and the media, news consumption habits, and socio-demographic characteristics.Footnote5 Individuals were then randomly assigned to one of four treatments or to a control group.

Subjects in the first two treatment groups were exposed to abridged versions of news reports about the election published either by The Guardian or The Telegraph, two broadsheets with opposite ideological leanings that are among Britain’s most prominent and widely circulated newspapers (Cowley and Kavanagh Citation2016). The two articles consisted of text only, clearly identified the source of the information (the newspaper where each article appeared), and differed in their description of the electoral outcome and in their interpretation of the political consequences of this result. The Guardian piece emphasised the unexpected nature of the voting returns and highlighted that the “tumultuous” election had given the Conservative party only a few more seats than the number required for a majority in the House of Commons. The Telegraph article, on the other hand, underlined that the Tories had secured an “outright majority” allowing them to govern without the need to form a coalition (see Figures A1 and A2 in the Online Appendix). Additionally, while The Guardian compared the number of Conservative seats against the 326-seat benchmark required for an overall majority, The Telegraph used 323 seats as the baseline – which takes into consideration the Speaker’s abstention and the fact that Sinn Féin MPs have historically refused to take their places in Parliament. This might further boost the perceived decisiveness of the Tory win among subjects allocated to this second treatment, which we denote “Decisive victory with The Telegraph as source”, vis-à-vis those in the “Narrow victory with The Guardian as source” condition.

Because these first two treatments used real news stories, congruence between the source and tone of the stimuli was not manipulated: The Guardian consistently gave the relatively left-wing spin on the 2015 election, while The Telegraph systematically framed the results in ways that reinforced the Conservative Party’s narrative (Cowley and Kavanagh Citation2016). Using real news articles as stimuli is in line with prior work underscoring the influence of the (print) media on public interpretations of electoral outcomes (Mendelsohn Citation1998), and should help assuage concerns about “overly strong or atypical” treatments in survey experiments (Barabas and Jerit Citation2010, 227).

The limitation of this approach is that it does not allow disentangling the effect of the content of a message from that of the source and its trustworthiness. Hence, we also constructed two mock news articles that portrayed the Conservative victory as either narrow or decisive, but removed any element that would allow subjects to identify the source of the information. These fictitious article excerpts were created based on a content analysis of media reports about the electoral outcome (Banducci et al. Citation2018), and looked similar to real newspaper articles (Figures A3 and A4, Online Appendix). We refer to these two additional treatments as “Narrow victory with no source” and “Decisive victory with no source”, respectively.

To assess whether the news stories associated with each of the four treatments actually conveyed different information about the decisiveness of the Conservative victory, we ran a series of manipulation checks through the CrowdFlower crowdsourcing platform (www.crowdflower.com). As we show in the Online Appendix (Section A2), the Tory victory was perceived as significantly more decisive by CrowdFlower contributors randomly allocated to the “Decisive victory with The Telegraph as source” and the “Decisive victory with no source” treatments than by those who read the articles corresponding to the “Narrow victory with The Guardian as source” and “Narrow victory with no source” conditions. On the other hand, perceptions were statistically indistinguishable between contributors who read the two articles portraying the victory as decisive (with and without an identifiable source), as well as between those exposed to the two “narrow victory” frames. This pre-test also failed to uncover systematic differences in the effectiveness of the messages associated with the four treatments.

Finally, the control group received a “placebo” story concerning the recruitment of a new chief executive by Whitbread (a large UK leisure group) taken from The Times (see Figure A5 in the Online Appendix). Table A1 in the Online Appendix summarises the distribution of subjects across the five experimental – treatment and control – conditions.

After reading the articles, participants were asked the following question: “To what extent do you agree/disagree that the Conservative government will be able to fulfil all of its campaign promises?” Responses were coded on a 5-point ascending scale, ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (5). We estimated the differences in the probability of agreeing/strongly agreeing with this statement between respondents allocated to each of the four treatments and those in the control group, and assessed the moderating influence of partisanship, vote choice, trust in the press/media and political sophistication on the treatment effects.

Before discussing our results, it is important to comment on the external validity of our study. As noted by Barabas and Jerit (Citation2010), the implausibility of effects and lack of realism are common criticisms levelled against survey experiments. However, the authors argue that concerns about generalisability should be mitigated when studying public opinion reactions to information about events that received substantial media attention, as was certainly the case of the 2015 UK general election. Although the fact that the electoral outcome was quite unexpected (Hill Citation2015) could in principle have rendered subjects more susceptible to treatment manipulations (Kernell and Mullinix Citation2018), the experiment was conducted at least three weeks after the results were known. Coupled with the ample media coverage of the election, this meant that participants had considerable time to update their opinions about the new political landscape. On the other hand, these considerations point to possible “pre-treatment effects” (Druckman and Leeper Citation2012, 875) in our study. As we discuss in the conclusions, this would, if anything, bias the data against our hypotheses.

Empirical analysis

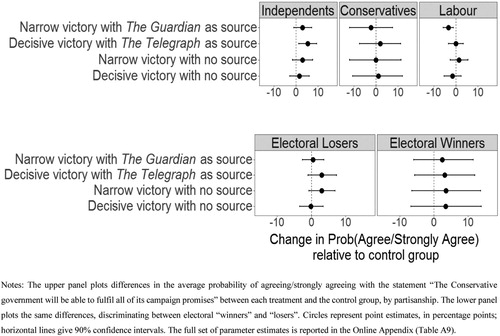

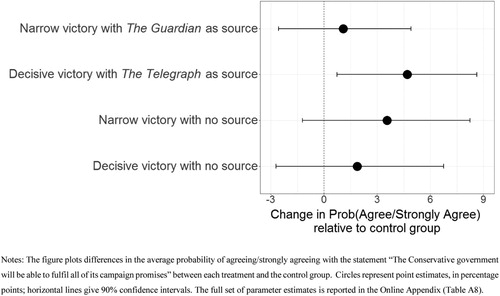

We start by examining hypothesis H1. plots differences in the average probability of agreeing/strongly agreeing with the statement “the Conservative government will be able to fulfil all of its campaign promises” under each treatment vis-à-vis the control condition, based on the estimates from an (unconditional) ordered logit model.Footnote6

Figure 1. Effect of the perceived decisiveness of the Tory victory on expectations about the government’s ability to fulfil its campaign promises.

Exposure to the “Decisive victory with The Telegraph as source” treatment increased the average probability of agreeing or strongly agreeing with the above statement by more than 4.5 percentage points, from 25.5% for participants who read the “placebo” story to 30.1% for subjects allocated to this condition. None of the other treatment effects was significantly different from zero.

The evidence in provides some support for H1 and, more generally, for the mandate theory of elections. In line with the mandate interpretation, subjects who read that the Conservatives had achieved a decisive victory were systematically more likely to believe that the incoming government would be able to implement the policies it promised, vis-à-vis those who read the “placebo” story. However, this happened only when the article underscoring the decisiveness of the result appeared in The Telegraph. The effect of exposure to an “anonymous” but otherwise similar message was statistically indistinguishable from zero. Our expectation that “narrow” frames would render subjects less likely to believe in the government’s ability to fulfil its manifesto pledges was not borne out by the data either, regardless of whether participants received an article published in The Guardian or in an unidentifiable news outlet.

To test hypothesis H2, we extended our baseline model to include interactions between treatments and indicators for Conservative and Labour identifiers, with independents – i.e. participants who stated they were not close to any political party – as the reference category.Footnote7 The upper panel of displays the estimates from this ordered logit model, broken down by partisanship.Footnote8

Labour identifiers who read the article from The Guardian were 3.4 percentage points less likely to agree/strongly agree that the Tories would be able to deliver on their promises than those in the control group. However, among Conservatives and independents, the “Narrow victory with The Guardian as source” treatment did not significantly affect expectations about government vis-à-vis the control condition. Although these results are broadly aligned with our second hypothesis, the moderating influence of partisanship on treatment effects was quite limited overall. Contrary to H2, the effect of the “Narrow victory with no source” treatment was not significantly stronger for Labour supporters than for Conservatives or independents. Additionally, neither of the two “decisive frames” was more effective in boosting confidence that the government would deliver on its promises among Conservatives than among independents or Labour partisans. In fact, accounts of a “decisive” electoral outcome only had a statistically significant effect among independents, and only when the article was published in The Telegraph. The “Decisive victory with The Telegraph as source” treatment raised non-partisans’ probability of agreeing/strongly agreeing that the government would be able to fulfil its campaign promises by 5 percentage points relative to the placebo story.

We must note that partisan biases did shape subjects’ expectations about elected officials. In each of the five experimental conditions, Conservatives were systematically (and around 50 percentage points) more likely to believe that the government would be able to implement its manifesto pledges than Labour identifiers, with independents always occupying the middle ground between the two partisan groups (Figure A9, Online Appendix). Nonetheless, there is little support for the hypothesis that partisan attachments systematically conditioned subjects’ propensity to accept information congruent with their preferred party’s narrative or to discard disconfirming messages. Instead, our results suggest that partisanship pre-determined subjects’ opinions about the government’s ability to fulfil its promises in such a way that additional information about the size of the Conservative victory had little impact on their judgments.

The bottom panel of , in turn, allows testing hypothesis H3. This lower panel summarises the estimates from an ordered logit model interacting the treatment indicators with a dummy for individuals who voted for the winning party, with respondents who cast a ballot for any other party grouped in the reference category.Footnote9 Subjects who voted either for the Conservatives or for any of the “electoral losers” were essentially impervious to information about the decisiveness of the Tory victory, contradicting H3. As we show in the Online Appendix (Figure A10), “electoral winners” were much more likely to believe/strongly believe in incumbents’ ability to enact their proposed policies than other voters, regardless of the particular message they were exposed to. The probability that a subject who voted for the Tories was confident that the government would deliver on its manifesto pledges exceeded 0.5 under every experimental condition. The corresponding probability dropped to 0.12–0.15 among “electoral losers”. Hence, the opinions of “winners” and “losers” were not significantly altered either by messages that reinforced their biases or by information challenging their prior beliefs. Instead, their electoral preferences trumped any information about the decisiveness or narrowness of the in-party’s win. Altogether, the evidence in reveals that, while party identification and vote choice strongly influenced expectations about the policy actions of the government, these factors played a limited role in conditioning subjects’ receptiveness to alternative descriptions of the size of the Conservative victory.

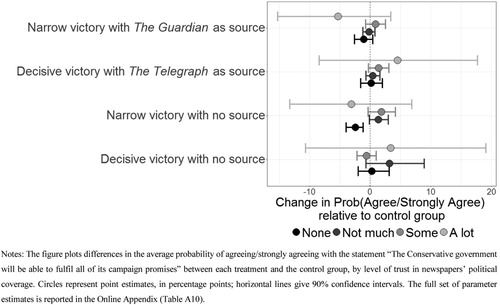

The finding that the “decisive victory” message had a significant effect when published by The Telegraph – a reputable and widely-circulated newspaper – but not in an unknown outlet suggests that media trust might have exerted a relevant role intervening between treatment exposure and expectations about government’s policy-making performance, as posited by hypothesis H4.Footnote10 A strong conditioning impact of trust in the press may also explain why the “Narrow victory with The Guardian as source” treatment significantly undermined Labour identifiers’ confidence that the government would honour its policy commitments in , while the “Narrow victory with no source” condition did not.

These claims find limited confirmation in the data, though. This is illustrated in , which displays average treatment effects by levels of trust in the accuracy and fairness of newspapers’ political coverage.Footnote11

For participants with no confidence in the press, the “Narrow victory with no source” treatment significantly lowered expectations about the Tories’ ability to fulfil their electoral promises vis-à-vis the control condition. A similar message published in The Guardian had no impact on these subjects’ judgments. This suggests that individuals who distrusted the press assigned lower credibility to an article published by a well-known broadsheet than to the same story appearing in an unidentifiable outlet. Nonetheless, the opinions of these subjects were equally unresponsive to the two “decisive victory” frames regardless of the source. Among subjects more inclined to believe in the accuracy of newspapers’ political coverage, the articles published in The Telegraph and The Guardian did not have a significantly stronger effect on expectations than their “anonymous” counterparts.

Like partisanship and vote choice, trust in the press had a sizable “direct” or unconditional influence on subjects’ beliefs. The average probability of agreeing/strongly agreeing with the statement “the Conservative government will be able to fulfil all of its campaign promises” was 7–15 percentage points lower for individuals with no confidence in newspapers than for those with higher trust levels in all experimental conditions (Figure A11, Online Appendix). However, shows that trust in newspapers did not affect subjects’ receptivity to information about the decisiveness of the Tory victory. The same conclusion holds when considering the conditioning impact of trust in the mass media – newspapers, TV and radio – more generally (Figure A12, Online Appendix).

While – drawing on Miller and Krosnick (Citation2000) – the above results focus on the moderating influence of generalised trust in the press and the media, we also assessed whether frequent readers of The Telegraph and The Guardian were more susceptible to messages published in their favourite broadsheet and/or less sensitive to information printed in the other paper. Although our survey does not measure trust in these specific newspapers, it is reasonable to assume that readers should have more confidence in the electoral interpretation proposed by their preferred news source than by that put forward by a paper known to have the opposite editorial line. However, there are no consistent variations in treatment effects between readers of The Telegraph and The Guardian, or between these and other subjects (Table A10, Online Appendix).

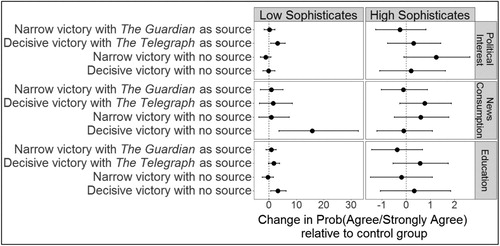

By contrast, the relevance of political sophistication as a treatment effect moderator is decidedly backed by the empirical analysis. This is apparent from , which reports estimates from ordinary logistic models testing hypothesis H5. Following Kernell and Mullinix (Citation2018), these models include interactions between treatment indicators and three well-known correlates of sophistication: political interest, news consumption, and education.Footnote12

None of the treatments swayed politically knowledgeable subjects’ beliefs about the ability of incumbents to keep their campaign promises vis-à-vis the control condition. Compared to the placebo story, though, news articles portraying the Tory victory as “decisive” significantly boosted less sophisticated participants’ confidence that the government would enact its policy programme. The upper-left panel of shows that, among subjects with little interest in politics, those allocated to the “Decisive victory with The Telegraph as source” treatment were 3.2 percentage points more likely to agree/strongly agree that the Tories would be able to fulfil their policy commitments than those assigned to the control group. Similarly, the “Decisive victory with no source” treatment raised the likelihood of agreeing/strongly agreeing with the above statement by more than 15 percentage points among subjects who rarely followed political news (middle-left panel), and by more than 3 points among participants without college education (bottom-left panel).Footnote13

In the same direction, Figure A13 in the Online Appendix shows that, compared to “high sophisticates”, less politically knowledgeable participants were significantly more prone to believe (doubt) that the Tories would honour their commitments when exposed to “decisive” (“narrow”) victory frames. The magnitudes of these differences were quite sizable. For instance, among subjects assigned to the “Narrow victory with no source” treatment, those who usually paid little or no attention to politics were half as likely to believe that the government would deliver on its promises as more politically interested participants. At the other extreme, subjects in the “Decisive victory with no source” condition who did not regularly follow the news were three times more likely to believe that the Conservatives would implement their policy programme than sophisticated subjects who received the same message. We do not observe differences in opinions by levels of political sophistication in the control group.

These results lend credence to the claim that “low sophisticates” were more sensitive to framing effects than politically knowledgeable subjects, as stated in H5.Footnote14 Moreover, while H1 was only partially corroborated for the full sample of participants, the relationship between the perceived decisiveness of the Tory victory and expectations about the government’s policy behaviour postulated in that first hypothesis clearly holds at the lowest levels of sophistication. The finding that the mandate theory prevailed among less politically knowledgeable subjects is particularly relevant in view of the argument that public perceptions of an electoral mandate embolden incumbents to exercise a mandate in practice (Grossback, Peterson, and Stimson Citation2006; Shamir, Shamir, and Sheafer Citation2008). To the extent that “low sophisticates” comprise the vast majority of the public (Krosnick and Kinder Citation1990), the estimates in and A13 suggest that alternative accounts of the decisiveness of incumbents’ victory may affect not only expectations about governments’ policy actions, but also the policies actually enacted. The framing of an electoral outcome in a given way may thus be, as Mendelsohn (Citation1998, 242) puts it, a “self-fulling prophecy”.

Concluding remarks

While a few studies have investigated the relationship between narrowness of the incoming party victory and government policy-making, virtually no work has examined how perceptions of the decisiveness of incumbents’ electoral victory shape public confidence in officeholders’ ability to fulfil their policy promises. This paper provides a first step in this direction, focusing on the 2015 UK general election.

The results of our survey experiment indicate that, when the in-party’s victory was portrayed as decisive, subjects – especially less politically sophisticated ones – became more likely to believe that the government would implement its policy programme. Although partisanship and media trust also affected expectations about government policy behaviour, these factors pre-disposed participants to either believe or doubt that the government would deliver on its campaign promises, outweighing any information about the decisiveness of the electoral victory rather than conditioning how such information was interpreted. In no case do we find evidence that portraying the Tory win as narrow enhanced participants’ confidence that incumbents would honour their policy commitments. Our results thus favour the mandate – over the normative – view of elections, at least with respect to how the (perceived) decisiveness of the incumbent party’s victory influences voters’ expectations about government policy-making.

These findings also have potentially relevant implications for electoral accountability. Healy and Malhotra (Citation2013) outline a necessary four-step loop in maintaining accountability: voters (1) observe real world policy outcomes, (2) attribute responsibility for these outcomes to political actors, (3) evaluate the performance of responsible officeholders with respect to the outcomes, and (4) feed these assessments into their vote choices in subsequent elections, thereby influencing the formation of policy. Importantly, accountability in this model is maintained through successive elections, while our focus was on exploring how citizens develop expectations about government’s ability to deliver policy outcomes depending on how incumbents’ electoral victory is portrayed. Nonetheless, voters may not blame incumbents for policy failures if they only managed to achieve a slim majority (step 2), whereas large victories may heighten expectations about the in-party’s performance (step 3). Given that accountability is maintained over successive elections, these baseline expectations about responsibility and performance may alter overall performance evaluations and attributions of responsibility at the next election.

We end by discussing some caveats to our findings. First, our treated subjects were exposed to a single message regarding the outcome of the 2015 UK election: they were told that the Tory win had been either decisive or narrow. Chong and Druckman (Citation2007) note that, in competitive democracies like Britain, individuals have access to alternative arguments representing opposing positions and portraying the same events in different – even antithetic – ways. They argue that competition between frames prompts more conscious information processing and integration of opposing viewpoints, moderating individuals’ opinions vis-à-vis situations in which they are only exposed to one-sided communications. Similarly, Barabas and Jerit (Citation2010) maintain that pristine experimental designs that ignore the competing messages individuals are exposed to in “real-life” may exaggerate the power of the stimuli. However, none of these authors maintains that exposure to conflicting perspectives precludes framing effects. Rather, as Barabas and Jerit (Citation2010) point out, survey experiments provide an approximation to what treatment effects might look like in the real world. This approximation works better, they claim, for events that received a substantial amount of coverage in multiple outlets and over an extended period of time.

Because our survey was administered three weeks after the high-profile 2015 election, most of the participants were probably exposed to ample news coverage and – in all likelihood – competing messages about the result. More than a third of our subjects reported they had been following the TV political coverage every day in the weeks before the experiment, and almost 90% of them had done so at least once a week. Since television news in Britain is constrained by fair coverage rules (Banducci et al. Citation2018), it is reasonable to assume that the majority of these individuals were exposed to alternative interpretations of the electoral outcome. This should mitigate concerns that subjects were “confined to a single perspective” (Chong and Druckman Citation2007, 637), even if our experimental design did not include a manipulation in which they were exposed to competing frames. Furthermore, 28% of the participants allocated to the “narrow victory” treatments regularly read conservative newspapers like The Telegraph, The Sun or The Daily Mail, while 12% of those assigned to the “decisive victory” conditions were frequent readers of left-leaning papers like The Guardian and The Mirror. Hence, at least these subjects – comprising 15% of our sample – were certainly exposed to conflicting descriptions about the decisiveness of the Tory victory.

If anything, these arguments suggest that the opinions of a considerable fraction of our subjects may have already been moulded, solidified or swayed by the plethora of political information available before receiving the treatments. To paraphrase Barabas and Jerit (Citation2010, 238), these subjects had already been – repeatedly – “treated” before being exposed to our experimental manipulations, and it is doubtful that one additional exposure would substantively alter their opinions. The likely consequence of this “pretreatment contamination” (Druckman and Leeper Citation2012, 875) is that the estimated effects of our manipulations understate the “true” size of framing effects. The fact that these effects are significant – and, in some cases, quite large – despite their downward bias bolsters our confidence in the robustness of our findings and in the external validity of our main conclusions.

Online_Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (1.1 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Ekaterina Kolpinskaya is Lecturer in Comparative Politics at Swansea University. Her research interests include political participation and representation of under-represented groups such as women, ethnic and religious minorities in Western democracies, as well as the effects from identity-based predictors on political attitudes and behaviours. Her research has been published in the Journal of Common Market Studies, The Journal of Legislative Studies, and Parliamentary Affairs, among other outlets.

Gabriel Katz is Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Exeter. His work focuses on comparative political behaviour, political economy and research methods. His research has been published in the American Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Studies, the Economic Journal, Political Behavior and Political Science Research and Methods, among other economics and political science outlets.

Susan Banducci is Professor of Politics at the University of Exeter. Her research interests are in the areas of comparative political behaviour, media and political communication. Banducci is the director of the Exeter Q-Step Centre, working toward advancing quantitative methods in the social sciences. Her research has been published in the British Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Studies, Acta Politica and Electoral Studies, among other journals.

Daniel Stevens is Professor of Politics at the University of Exeter. His main interests are in mass political behaviour in the United States and Britain, studying the major influences on political attitudes and behaviour, such as the economy, political advertising, and the news media. Dan’s current projects include ongoing research into perceptions of political advertising, patterns and effects of different forms of mobilization in elections, and the role of leaders in British elections. His research has been published in the American Journal of Political Science, British Journal of Political Science, and European Journal of Political Research, among other outlets.

Travis Coan is a Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Exeter. His work has appeared in International Studies Quarterly, International Interactions and Political Psychology, among other journals.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The assumption here is that incumbents are committed to implementing their policy programme. Bara (Citation2005) finds that this holds true for the overwhelming majority of policies pledged by UK governments.

2 More generally, prior research shows that electoral “winners” and “losers” differ with respect to a number of politically relevant attitudes such as satisfaction with democracy, evaluations of leaders and policies, and in the way in which their process political information (Dahlberg and Linde Citation2016; Kernell and Mullinix Citation2018).

3 Note that, while H3 is a variant of H2, the fact that one of these hypotheses is/is not supported by the data does not imply that the other will hold as well/not hold either. About 10% of the Tory voters in our sample did not self-identify as Conservatives, and almost 60% of the “electoral losers” were not Labour identifiers.

4 Miller and Krosnick (Citation2000) further contend that political knowledge and media trust simultaneously moderate the effect of news exposure. Specifically, they argue that media effects are greatest among citizens who are both highly knowledgeable and highly trusting of the media. We also test this claim in our empirical analysis.

5 The definition and coding for these variables can be found in the Online Appendix (Section A1).

6 The results remain similar if we dichotomise participants’ responses and fit a binary logit, as well as if we treat the dependent variable as continuous and estimate treatment effects by ordinary least squares (Table A8 and Figure A8, Online Appendix).

7 Subjects affiliated with other parties were excluded from this analysis.

8 Kam and Trussler (Citation2017) show that, when assessing how non-randomly assigned variables like partisanship condition treatment effects, it is important to account for the potential confounding influence of other background characteristics. Following these authors, this specification controls for participants’ age, education, gender, ethnicity, marital status, union membership, political interest, news consumption habits, trust in newspapers, and turnout (Table A9, Online Appendix). Hence, these estimates (and all those presented below) represent average treatment effects conditional on covariates.

9 The sample is restricted to subjects who voted in 2015. This model incorporates the same controls as the one in the upper panel.

10 The Telegraph was in fact perceived as the most credible source in our pre-test (Table A7, Online Appendix).

11 This model includes the same controls as previous specifications (Table A10, Online Appendix).

12 These specifications also incorporate socio-demographic, political and attitudinal controls (Table A11, Online Appendix).

13 For ease of exposition, the proxies for political sophistication were dichotomised in . The conclusions are robust to alternative operationalisations of these variables (see the Online Appendix).

14 We also examined the joint moderating impact of political sophistication and media trust. Contrary to Miller and Krosnick (Citation2000), we find no evidence of stronger treatment effects among subjects who were both highly trusting and politically knowledgeable (Figures A14 and A15, Online Appendix).

References

- Altheas, Scott, Anne Cizmar, and James Gimpel. 2009. “Media Supply, Audience Demand, and the Geography of News Consumption in the United States.” Political Communication 26 (3): 249–277. doi: 10.1080/10584600903053361

- Anderson, Christopher, André Blais, Shaun Bowler, Todd Donovan, and Ola Listhaug. 2005. Losers’ Consent: Elections and Democratic Legitimacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Banducci, Susan, Iulia Cioroianu, Travis Coan, Gabriel Katz, and Daniel Stevens. 2018. “Intermedia Agenda Setting in Personalized Campaigns: How News Media Influence the Importance of Leaders.” Electoral Studies 54: 281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2018.04.011

- Banducci, Susan, and Chris Hanretty. 2014. “Comparative Determinants of Horse-race Coverage.” European Political Science Review 6 (4): 621–640. doi: 10.1017/S1755773913000271

- Bara, Judith. 2005. “A Question of Trust: Implementing Party Manifestos.” Parliamentary Affairs 58 (3): 585–599. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsi053

- Barabas, Jason, and Jennifer Jerit. 2010. “Are Survey Experiments Externally Valid?” American Political Science Review 104 (2): 226–242. doi: 10.1017/S0003055410000092

- Baum, Matthew, and Phil Gussin. 2004. “In the Eye of the Beholder: An Experimental Investigation Into the Foundations of the Hostile Media Phenomenon.” Working Paper, Harvard University.

- Birch, Sarah. 2008. “Electoral Institutions and Popular Confidence in Electoral Processes: A Cross-national Analysis.” Electoral Studies 27 (2): 305–320. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2008.01.005

- Bolsen, Toby, James Druckman, and Fay Cook. 2014. “The Influence of Partisan Motivated Reasoning on Public Opinion.” Political Behavior 36 (2): 235–262. doi: 10.1007/s11109-013-9238-0

- Campbell, Angus, Phillip Converse, Warren Miller, and Donald Stokes. 1960. The American Voter. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Chong, Dennis, and James Druckman. 2007. “Framing Public Opinion in Competitive Democracies.” American Political Science Review 101 (4): 637–655. doi: 10.1017/S0003055407070554

- Cowley, Philip, and Dennis Kavanagh. 2016. The British General Election of 2015. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dahlberg, Stefan, and Jonas Linde. 2016. “Losing Happily? The Mitigating Effect of Democracy and Quality of Government on the Winner-Loser Gap in Political Support.” International Journal of Public Administration 39 (9): 652–664. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2016.1177831

- Druckman, James. 2001. “On the Limits of Framing Effects. Who Can Frame?” The Journal of Politics 63 (4): 1041–1066. doi: 10.1111/0022-3816.00100

- Druckman, James, and Thomas Leeper. 2012. “Learning More from Political Communication Experiments: Pretreatment and Its Effects.” American Journal of Political Science 56 (4): 875–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2012.00582.x

- Druckman, James, Erik Peterson, and Rune Slothuus. 2013. “How Elite Partisan Polarization Affects Public Opinion Formation.” American Political Science Review 107 (1): 57–79. doi: 10.1017/S0003055412000500

- Ferejohn, John. 1986. “Incumbent Performance and Electoral Control.” Public Choice 50 (1): 5–25. doi: 10.1007/BF00124924

- Gomez, Brad, and Matthew Wilson. 2001. “Political Sophistication and Economic Voting in the American Electorate: A Theory of Heterogeneous Attribution.” American Journal of Political Science 45 (4): 899–914. doi: 10.2307/2669331

- Grossback, Lawrence, David Peterson, and James Stimson. 2006. Mandate Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Healy, Andrew, and Neil Malhotra. 2013. “Retrospective Voting Reconsidered.” Annual Review of Political Science 16: 285–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-032211-212920

- Hill, Timothy. 2015. “Forecast Error: The UK General Election.” Significance 12: 10–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-9713.2015.00823.x

- Hobolt, Sara, and Robert Klemmensen. 2008. “Government Responsiveness and Political Competition in Comparative Perspective.” Comparative Political Studies 41 (3): 309–337. doi: 10.1177/0010414006297169

- Kam, Cindy, and Marc Trussler. 2017. “At the Nexus of Observational and Experimental Research: Theory, Specification, and Analysis of Experiments with Heterogeneous Treatment Effects.” Political Behavior 39 (4): 789–815. doi: 10.1007/s11109-016-9379-z

- Kernell, Georgia, and Kevin Mullinix. 2018. “Winners, Losers, and Perceptions of Vote (Mis)Counting.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 24 (1): 1–24. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edx021

- Krosnick, Jon, and Donald Kinder. 1990. “Altering the Foundations of Support for the President Through Priming.” The American Political Science Review 84 (2): 497–512. doi: 10.2307/1963531

- Kunda, Ziva. 1990. “The Case for Motivated Reasoning.” Psychological Bulletin 108 (3): 480–498. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480

- Lebo, Matthew, and Daniel Cassino. 2007. “The Aggregated Consequences of Motivated Reasoning and the Dynamics of Partisan Presidential Approval.” Political Psychology 28 (6): 719–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2007.00601.x

- Mendelsohn, Matthew. 1998. “The Construction of Electoral Mandates: Media Coverage of Election Results in Canada.” Political Communication 15 (2): 239–253. doi: 10.1080/10584609809342368

- Miller, Joanne, and Jon Krosnick. 2000. “News Media Impact on the Ingredients of Presidential Evaluations: Politically Knowledgeable Citizens are Guided by a Trusted Source.” American Journal of Political Science 44 (2): 301–315. doi: 10.2307/2669312

- Pickup, Mark, and Sara B. Hobolt. 2015. “The Conditionality of the Trade-off between Government Responsiveness and Effectiveness: The Impact of Minority Status and Polls in the Canadian House of Commons.” Electoral Studies 40: 517–530.

- Powell, G. Bingham. 2000. Elections as Instruments of Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Sances, Michael, and Charles Stewart. 2015. “Partisanship and Confidence in the Vote Count: Evidence from U.S. National Elections Since 2000.” Electoral Studies 40: 176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2015.08.004

- Shamir, Michal, Jacob Shamir, and Tamir Sheafer. 2008. “The Political Communication of Mandate Elections.” Political Communication 25 (1): 47–66. doi: 10.1080/10584600701807869

- Vowles, Jack, Gabriel Katz, and Daniel Stevens. 2017. “Electoral Competitiveness and Turnout in British Elections, 1964-2010.” Political Science Research and Methods 5 (4): 775–794. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2015.67