?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

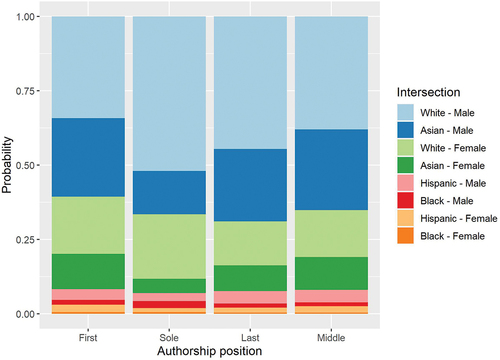

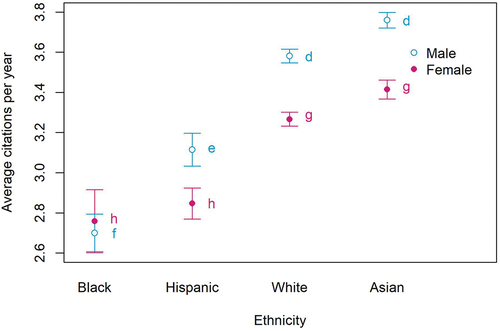

Female scientists and researchers with diverse cultural backgrounds, especially of the Global South, are underrepresented in scientific systems. This is also the case for land use science and even for research teams researching in Global South countries. To assess trends in gender parity, ethnic diversity and intersectionality in this field, we conducted a meta-analysis based on systematic literature review that included 316,390 peer-reviewed journal articles. We found that 27% of all authors between 2000–2021 represented women. Ethnicity representation was biased towards White researchers (62%) followed by Asian (30%), Hispanic (6%) and Black (2%) researchers. Intersection of inequalities further underrepresented Black and Hispanic women when author positions were considered, giving Black women 0.6% chance of becoming first authors in land use science in comparison to 19.3% chance of White women. Supportive actions to empower women are needed to reduce intersectional inequalities and to achieve the sustainable development goals.

Introduction

Land access, use, management and planning are key for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). While several SGDs such as zero hunger (SDG 2), affordable and clean energy (SDG 7), sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), climate action (SDG 13), life on land and below water (SDG 14 and 15), are directly linked to land and its use, others are indirectly influenced. In particular, land use research in the Global South is highly relevant, considering projections of doubling populations by 2050 (UN DESA, Citation2019), which would further accelerate existing challenges linked to food insecurity, biodiversity threats and land degradation (Leclère et al., Citation2020).

It has been argued that the puzzles to unlocking the SDGs accelerators lie in the complex interactions, causal relationships and feedback loops of the different SGD targets (Fu et al., Citation2019; Gao & Bryan, Citation2017). Consideration of diverse academic disciplines, perceptions, knowledge and approaches are crucial to understanding these complex interactions of land use systems and to solve challenges in their sustainable management. Studies have shown that, for example, interventions and decisions made by women are often more effective in conserving biodiversity (Cook et al., Citation2019) or reducing greenhouse gas emissions (Villamor et al., Citation2014).

Unfortunately, land use decisions made at household and community levels are often biased against women primarily due to land tenure rights that favor men, in particular, in many countries of the Global South (Fonjong et al., Citation2013; Villamor et al., Citation2014). Women, however, execute land-related decisions and have equally been placed at the heart of land matters including farming, conservation and management regardless of limited tenure (Fonjong et al., Citation2013). In the Global South, where land related issues are highly topical and relevant, unravelling and understanding the complexity of land use systems would highly benefit from diverse perspectives and decision making from women at all levels of management.

Similar to other sectors and parts of society, academic systems have been found to favor male scientists (Helmer et al., Citation2017; Van Arensbergen et al., Citation2012). Studies found for example, a general underrepresentation of female scientists in research (Abramo et al., Citation2009), academic tenure positions (Sheltzer & Smith, Citation2014) and scientific publications (Helmer et al., Citation2017; Larivière et al., Citation2013; Lerback & Hanson, Citation2017). Peer-reviewed publications in scientific journals are considered as an indicator for the experience and status of a researcher. Gender disparities in terms of publication outputs, academic positions, editorial boards and society memberships were found for example, in ecology (Maas et al., Citation2021), political science, economics psychology and social policy (Schucan Bird, Citation2011), soil science (Dawson et al., Citation2021; Vaughan et al., Citation2019) or archaeology (Tushingham et al., Citation2017).

At the same time, gender disparities in scientific systems and publications are also likely to be shaped by geographical and ethnic biases (Hopkins et al., Citation2013). Women’s participation and representation in science differ between countries. For example, Abramo et al. (Citation2021) found a larger gender gap in Italy than in Norway, which the authors attributed to stronger societal engagement of women in family and domestic responsibilities in Italy than in Norway. Tao et al. (Citation2017) found that women in the US published more than men in engineering and less in science while in China they found no differences between men and women in science publications but only in engineering, where women published more. These differences in China and the US were amplified by variables like family obligations (marriage and children). For example, a married female researcher in China on average has a better productivity compared to a single woman. They also found that in China, children negatively affect productivity, in contrast to the US where neither being married nor having children did affect productivity. Across sub-Sahara African countries, Fisher et al. (Citation2020) found that women (single and married) on average had about 26% less articles accepted for publication in journals in comparison to men in any given year. One of the attributed factors to the above trend was family obligations, where, if doctoral students got married during their studies, it reduced female students’ productivity but had an opposite effect on the male doctoral students. Besides the number of authorships of scientific publications, other indicators for academic performance, for example academic rank, have also been used to analyze disparities between different ethnic groups (Hopkins et al., Citation2013; Vaughan et al., Citation2019). While disparities have previously been observed for isolated factors, when these factors interact, intersect and overlap one another they result in an effect known as intersectionality, which amplifies the underrepresentation of women within certain societal groups (Crenshaw, Citationn.d.). For example, there is disproportionate bias against women when both geographical and ethnic factors are considered (Van Arensbergen et al., Citation2012; Vaughan et al., Citation2019). If more factors are taken into account such as different career stages, the underrepresentation of female scientists becomes even more striking (Hopkins et al., Citation2013; Vaughan et al., Citation2019). Hopkins et al. (Citation2013), for example, found that ‘Black’ and ‘Hispanic’ women are more marginalized and underrepresented when gender, race, geographical location, discipline and career variables are combined.

Different studies have found a consistent underrepresentation of female scientists in publications (Helmer et al., Citation2017). Scholarly productivity is, however, often also measured by other indicators including the number of citations, the h-index (h = high impact) and the position in the order of authors (Fisher et al., Citation2020; Hopkins et al., Citation2013; Huang et al., Citation2020; Wren et al., Citation2007). According to Huang et al. (Citation2020) and Andersen et al. (Citation2019), the disparity between men and women in scientific publications is further worsened when disaggregated by gender, age and author position. The position of an author often indicates different levels of scientific careers with the last position being commonly reserved for a senior author and the first position frequently being held by early career scientists (e.g. during doctoral studies). These mutually reinforcing disparities result in fewer publications authored by women, in particular, from specific ethnic groups and are often dominated by researchers from US and Europe.

This phenomenon of intersectionality is leading to the disregard of diverse and valuable perspectives from researchers with different backgrounds and ideas. In particular, land use research, one of the biggest research priorities to solve sustainability challenges of the Global South, would highly benefit from diverse research teams (Maas et al., Citation2021; Whelan & Schimel, Citation2019).

Despite the general consensus on gender, ethnicity and intersection of inequalities in science, variations of gender representation are likely to appear in different scientific disciplines. For example, in fields like ecology only 11% account for top publishing authors and are majority from Global North (Maas et al., Citation2021), and in archaeology – a female rich discipline- had 32% female authors between 1974 and 2016 (Tushingham et al., Citation2017). However, until now, there exists no study that has focused on publications within the field of land use science encompassing different associated disciplines such as agriculture, environmental sciences and ecology, biodiversity, forestry, water resources and energy and fuels. Moreover, from the available studies, it is rather difficult to reconcile these variations across disciplines because of limited inference space, which is as a result of sampling limitations in previous studies considering gender disparity in general science or based on specific journals, countries or institutions.

Therefore, here we evaluate gender disparities in land use science by assessing the gender and ethnic diversity of authors within the field of land science and their scholarly productivity indicated by the annual citations and authorship positions. We look at intersectionality of gender, ethnicity and scholarly productivity focusing on an in-depth study that covers more than 20 years of scientific research in land use to show the progress towards gender parity and ethnic diversity in land use research. We hypothesize that (1) authorship position is associated with gender and ethnicity and (2) that there are differences in average citation rates between gender groups and among ethnicities.

Materials and methods

Collection of data

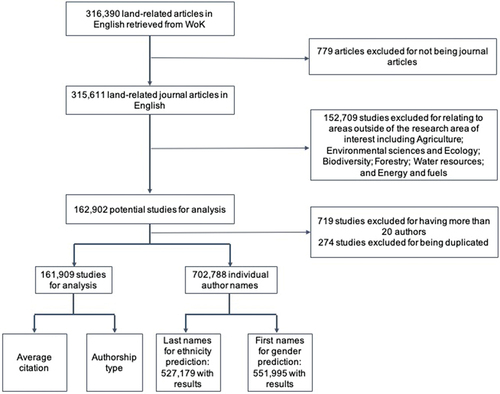

The Clarivate’s Web of Science (WoS) database was sourced for articles published from 2000 to 2021 using an all-inclusive search term for land-related publications on 25 May 2021. The search query was ‘topic = land, AND document type = Article, AND language = English, AND time span = 2000–2021’. We obtained a total of 316,390 articles.

A strict inclusion-exclusion screening scheme with four steps was applied in R (R Core Team, Citation2020), R-Studio (RStudio Team, Citation2019) and Excel (Microsoft-Corporation, Citationn.d.). In the first step, we maintained only journal articles and excluded all other forms of publications (e.g. book in series), resulting in 315,611 studies. In the second step, based on the research area variable classified by WoS and embedded in the extracted dataset, we kept only articles with research areas relevant to land use science such as Agriculture; Environmental sciences and Ecology; Biodiversity & Conservation; Forestry; Water resources; and Energy & Fuels leaving 162,902 studies in the sample.

The third and last step of the screening scheme were to exclude studies with more than 20 authors to facilitate the memory usage of R and the duplicated studies. As a result, 719 studies (0.4% of the original sample) with 21–515 authors were excluded. We removed further 274 duplicated studies, resulting in 161,909 studies for further analysis. From the 161,909 studies, we obtained 702,788 individual author names for analysis ().

Gender and ethnicity balance assessments

Gender and ethnic diversity assessments were performed using two R packages, namely, genderizeR (Wais, Citation2016) and predictrace (Kaplan, Citation2021). While the package genderizeR is used only for predicting the authors’ gender, the package predictrace has two separate functions to determine both gender and ethnicity of authors.

Both R packages genderizeR and predictrace predict the authors’ gender by matching their first names with the corresponding names in the data sources of each package. The package genderizeR is accessing the genderize.io database via its API. The database contains 114.5 million unique names from 242 countries (Genderize.io, Citation2021) and is constantly being updated from social network profiles since 2013 (Wais, Citation2016). The US Social Security Administration (SSA) database in package predictrace contains more than 92,600 unique names from annual Social Security card applications for births that occurred in the United States between 1880–2019 (Kaplan, Citation2021; Wais, Citation2016). Both approaches have been applied in previous literature (e.g. for SSA database: Larivière et al., Citation2013; West et al., Citation2013); for genderize.io API: (Dion, et al., Citation2018; Fortin, et al., Citation2021; Teele and Thelen, Citation2017) to obtain information about gender and ethnic diversity of large datasets.

The genderizeR package allows splitting the first names into single strings, which are matched with entries of the database by its API to return the most likely gender of the associated name along with a matching probability (i.e. the proportion of male and female profiles for each name). Meanwhile the predictrace package links the non-formatted names (i.e. without spaces and hyphens) with the SSA database for the corresponding gender and accuracy probability. Therefore, to optimize the prediction process, we split the first names with more than one string (i.e. ‘Marrie Anne’) into single strings (i.e. ‘Marrie’ and ‘Anne’). Then, they separately underwent the gender prediction process. First names that were initialized in the sample were not excluded; however, they would result in being undetermined in the gender assessment processes. If both databases predicted different gender to be most likely, the result with the highest probability was considered for further analysis.

Both packages are characterized by a number of limitations. Package genderizeR was reported to have an inherent error rate of 2–5% (Santamaría & Mihaljević, Citation2018; Teele & Thelen, Citation2017). For package predictrace, West et al. (Citation2013) reported that there might be a tendency of excluding or misrepresenting uncommon and androgynous names in the SSA database. By combining both databases in a complementary way, we minimized these limitations.

Using the package predictrace, authors’ ethnicity was determined based on last names. The package utilizes the SSA database with 167,000 stored last names and their equivalent most likely ethnicity (‘Asian’, ‘Black’, ‘Hispanic’, ‘White’, ‘American-Indian’, ‘Asian-Black’, ‘Black-White’ and ‘Two ethnicities’) (Kaplan, Citation2021). Similar to the gender prediction process, the last names were split into single strings to predict the most probable ethnicity of each author.

Determination of scholarly output

Scholarly output was determined by authorship position and average citations per year. Authorship position was classified by the sequence of the authors’ names in an author order as ‘Sole’, ‘First’, ‘Last’ or ‘Middle’ author. If an article had only two authors, we classified the first as ‘First’ and the latter as ‘Last’.

We used the average number of citations per year per article as another indicator for scholarly output calculated based on all citations in all databases within WoS products (including Web of Science Core Collection, KCI-Korean Journal Database, Russian Science Citation Index, SciELO Citation Index) up to May 2021, and the years since its publication.

Descriptive and statistical analysis

Trends of gender disparity are reflected via the proportion of male and female authors of the whole sample, each ethnic group, and each authorship position respectively. We analyzed and visualized all data in R Studio (Dowle and Srinivasan, Citation2021; Morales et al., Citation2020; R Core Team, Citation2020; Wickham, Citation2016, Wickham, Citation2021, Wickham, et al., Citation2019, Wickham, et al., Citation2021, Citation2007). The annual growth rate of each ethnicity group was calculated based on the difference in absolute numbers of authors between two consecutive years divided by the number of authors in the former year.

To analyze the impact of ethnicity and gender on scholarly output, we used authorship position as a nominal response variable with four levels (sole, first, last and middle), and gender (two levels male, female), and ethnicity (four levels ‘White’, ‘Asian’, ‘Hispanic’ and ‘Black’) as independent variables. In order to explore how the intersection of gender-ethnicity might affect the authorship position, we tested for their association by conducting Pearson’s chi-squared tests of independence (McHugh, Citation2013), where the null hypothesis implies that the variables of interest are independent (Franke et al., Citation2012). We also visualized data over time.

We tested whether scholarly output measured by average citations is affected by the first authors’ traits such as gender and ethnicity based on a subsample including only first and sole author names and omitting last and middle author names. This enabled each observation to reflect one unique article and its corresponding number of citations. First, we used the Anderson-Darling normality test to assess whether the average number of citations per year follows a normal distribution (Gross & Ligges, Citation2015; Nelson, Citation1998). Subsequently, we conducted non-parametric methods including the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test (or also known as Mann–Whitney U test or Wilcoxon rank sum test) to test for the differences in the average number of citations between gender groups and the Kruskal–Wallis test (Kassambara, Citation2021) for ethnicity groups. Both methods are useful in those cases where the normal distribution assumption of their parametric analogs (t-test and ANOVA) is violated, as they transform data from two or more independent samples to ranks before applying the usual parametric procedures (Conover & Iman, Citation1981). For the Kruskal–Wallis test, we found significant differences for at least one group. We conducted the Bonferroni method of post-hoc multiple pairwise comparisons to identify which samples differed significantly from each other (De Mendiburu, Citation2020). Using both Wilcoxon rank sum and Kruskal–Wallis tests, we also tested for significant differences in citation rate between different gender-ethnicity subsamples.

Results

Gender diversity in land use science publication

The gender prediction tools successfully determined 382,477 male and 166,745 female authors out of 702,788 authors in the sample (78.1%). However, the success rate varied among publication years in the study period. We noticed that many authors’ first names were only recorded as initials in WoS database for the years before 2007, which led to the relatively low success rate of these years (25.6% on average). For the successfully-determined cases, the mean accuracy probability of the gender outcomes was 95.6%. There were 2773 cases in the total sample where the name was considered as gender-neutral (probability of 50% for each gender).

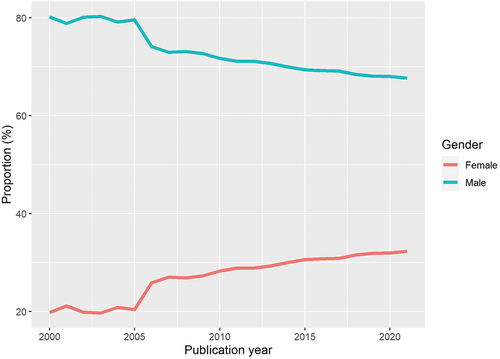

Trend analysis showed that the proportion of female authors in land use science has increased from 19.8% in 2000 to 32.3% of total authors in 2021 (). Although the gap between the number of female and male authors in land use science literature has slightly decreased at the average rate of 1.2% per year, the number of male authors remains twice as high as the number of female authors by 2021.

Ethnicity diversity in land use science publication

We were able to determine the most probable ethnicity from 75% of all authors in our sample. Besides the four main categories ‘Asian’, ‘Black’, ‘White’ and ‘Hispanic’, we subsumed 165 authors predicted as ‘American – Indian’, ‘Asian – Black’, ‘Black – White’ or ‘Two ethnicities’ as ‘Two ethnicities’.

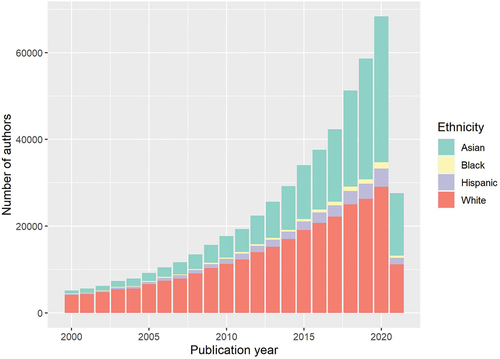

Trend analysis showed that the share of ‘Asian’ authors has gradually grown over the years to become the largest group in 2020, accounting for 49.1% of all authors in our sample (). During the same time, the share of ‘White’ authors has been halved and decreased from 80.2% in 2000 to 42.5% in 2020. The share of ‘Black’ and ‘Hispanic’ authors remained more or less stable over the years, accounting for on average 1.9% and 5.8% of all authors respectively. The share of the group with ‘Two ethnicities’ only accounted for 0.03% of all authors on average with no particular trend.

Figure 3. Total numbers of authors in land use science journal articles belonging to 5 ethnicity groups ‘Asian’, ‘Black’, ‘Hispanic’, ‘White’, and ‘Two ethnicities’ in 2000–2021. The ‘Two ethnicities’ group consists of ‘American-Indian’, ‘Asian-Black’, ‘Black-White’, or ‘Two ethnicities (without further specification)’. As this group only comprises an average of 0.03% of the total sample, it was not included in the graph. The last bar included publications within the first five months of 2021.

Annual growth rates of the total number of authors calculated for each ethnic group indicates that the ‘Asian’ ethnic group had by far the highest average annual growth rate of 21.6% over the period 2007–2020, followed by 15.4% and 14.5% of the ‘Black’ and ‘Hispanic’ groups, respectively. The ‘White’ group had the lowest average annual growth rate at 10.3%.

Intersection of gender and ethnicity

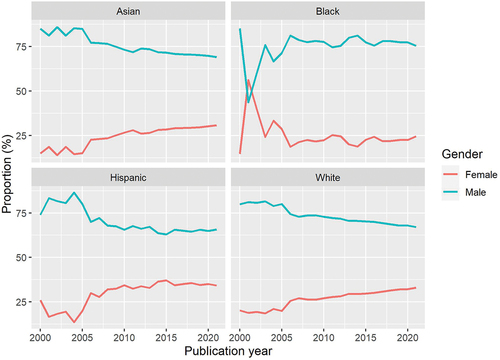

Looking at intersectionality, we analyzed gender gaps for each of the four main ethnic groups (). For each group, we found a similar trend to the gender overview, where the share of female authors annually rose at the average rate of 0.8%, 0.9%, 1.2% and 1.5%, of Black, Hispanic, White and Asian authors, respectively. Nevertheless, the gender gap in the ‘Black’ ethnic group had the lowest closing rate and remained almost unchanged over the years at 25% female vs. 75% male authors by 2021. In the year 2002, female ‘Black’ authors briefly accounted for a higher share than male ‘Black’ authors. Since the total number of ‘Black’ authors in the years 2000 to 2005 was overall relatively low (on average 144 authors accounting for only 2% of all authors), we would attribute this effect to the prediction error rate of the used algorithms rather than an actual brief closing of the gender gap, in particular since the gap widened afterwards immediately again.

Authorship position in land use science publication

The average size of the author teams considered in this analysis was 5.8 authors, with a standard deviation of 3.2. For the whole sample, we recorded 11,120 ‘Sole’ authorships from the same number of individually authored studies (6.9% of total article sample and 1.6% of total author sample), and 150,783 ‘First’ and ‘Last’ authorships each from the same number of jointly-authored studies (21.5% of total author sample each). Furthermore, we classified 390,102 authorships under the ‘Middle’ authors category (55.5% of total author sample).

We found persisting but closing gender gaps for all four categories of authorship positions (). This trend was however most pronounced for first (1.8% per year) and much less pronounced for last authorship positions (0.8% per year), both middle and sole authorship observed the average closing rate of 1.1% per year. The difference between the share of male and female authorships was around 60% for all four groups at the beginning of the study period and decreased to 25.4% for the first, 35.7% for the middle, 36.7% for the sole and 44.5% for the last author group. Since in academia author positions can be linked to the status and experience of an author, we would argue that this indicates a closing gender gap in the early stages of academic careers, but a largely persistent gender gap in the later stages such as professorships and senior academic positions.

Figure 5. Proportion of female and male authors by authorship position in land use science literature in 2000–2021. These proportions represent 150,783 first, 390,102 middle, 150,783 last, and 11,120 sole authorships.

Pearson’s chi-squared tests indicated that authorship position was significantly associated with both gender (, p < 0.05) and ethnicity (

, p < 0.05). ‘Black – Female’ and ‘Black – Male’ authors had the lowest probability to become first authors with 0.6% and 1.6% respectively (). These two pairs of intersectionality are also least likely to be either sole, last or middle authors, followed by ‘Hispanic’ females and ‘Hispanic’ males. ‘White’ men are found to dominate all four groups of authorship positions with a probability of 34.2% to become first author or of 44.6% to become last author.

Figure 6. Probability of an author from a certain ethnicity and gender being in either of the four authorship positions. The probability ranges from 0 to 1, and is measured by the proportion of each pair of intersectionality within one group of authorship positions. This figure represents 87,377 first, 23,4620 middle, 87,569 last, and 5,804 sole authorships in the study period. The number of observations of each group is smaller than the original number due to missing information on either gender or ethnicity.

Average citation rates in land use science publication

Based on a sample of 93,181 observations containing 87,377 first and 5,804 sole authors and excluding all observations without information on gender and ethnicity, the average citation rate per paper has a mean of 3.5 times per year and a standard deviation of 5.6. The Anderson–Darling normality test resulted in a goodness-of-fit statistic of 9,702 (p < 0.05) indicating that the average citation rate does not follow a normal distribution. Results from Wilcoxon rank sum tests indicate that the average citation rates of articles firstly authored by males were significantly higher than those by female authors (p < 0.05, ). We also observed significant differences in citation rates between male and female first authors belonging to White and Asian groups, while the differences between male and female first authors in Black and Hispanic groups are not significant. The Kruskal-Wallis tests and post-hoc multiple pairwise comparisons of data ranks reveal significantly different citation rates amongst the four ethnic groups (p < 0.0001), with ‘Asian’ authors being cited more frequently (Xasi = 3.7) followed by ‘White’ (Xwhi = 3.5), ‘Hispanic’ (Xhis = 3.0) and ‘Black’ authors (Xbla = 2.7) (). The difference in citation rates between ‘Asian’ and ‘White’ authors however are not significant.

Table 1. Statistical results from Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction

Table 2. The summary results from Kruskal-Wallis tests and the post-hoc multiple pairwise-comparison of three models. Models’ a-c show the association between average citation and ethnicity of first and sole authors as a whole (a), first and sole male authors (b), first and sole female authors (c). These models stand for 93,181 articles which were firstly-authored by 51,020 ‘White’, 34,518 ‘Asian’, 5,508 ‘Hispanic’ and 2,135 ‘Black’ authors, respectively. In pairwise comparisons, groups sharing the same letter are not significantly different by data ranks at the alpha level of 0.05

Trends for the average citation rates are similar to the trend of total first and sole authorships even when we broke them down to separate male and female subsets () and ). Regardless of their gender, the ‘White’ and ‘Asian’ authors are significantly more likely to be cited than ‘Hispanic’ and ‘Black’ authors. While there is a significant difference between male- ‘Hispanic’ and male- ‘Black’, the citation rates between female- ‘Hispanic’ and female- ‘Black’ are similar.

Figure 7. Mean of average annual citations rates by gender and ethnicity intersection of first and sole authors. The whiskers represent mean ±1 standard error, with NA values removed. The letter designations represent the significant difference resulting from post-hoc multiple pairwise comparisons by data ranks. This figure reflects the average citation rate of 91,181 articles authored by 1,591 ‘Black’ males, 544 ‘Black’ females, 3,304 ‘Hispanic’ males, 2,204 ‘Hispanic’ females, 32,898 ‘White’ males, 18,122 ‘White’ females, 23,910 ‘Asian’ males and 10,608 ‘Asian’ females as first or sole authors.

Discussion

Gender disparity

Our findings support earlier studies indicating an ongoing underrepresentation of women in science and as publishing authors. While no previous study has been done specifically on women representation in land use science, these results are in line with findings from other science disciplines like ecology (Maas et al., Citation2021), soil science (Vaughan et al., Citation2019) and archaeology (Tushingham et al., Citation2017). Similar trends were also observed in the British ecology journals (Schucan Bird, Citation2011), and in journals listed in Nature Index (Bendels et al., Citation2018) and JSTOR corpus (West et al., Citation2013). Despite a persistent gender gap in terms of journal articles published by men and women, our findings show that the gender gap is closing at a very slow rate of 1.2% annually. This relatively slow increase was also noted for top publishing ecologists by Maas et al. (Citation2021), who found that the number of women had increased from 3% (1945 to 1959) to 13% (1990 to 2004) and 18% (2005 to 2019). There is a knowledge gap when comparing the total female population in academia to the total female publishing population within academia. While that is the case, studies like Fuchs et al. (Citation1998) show us that the total female population in academia is increasing over the years. However, the increase found by other researchers and in this study pales in comparison to the global share of the female population (~47% in 2020) (UN DESA, Citation2019). From the results of this study, we cannot determine any causal relationship, why women are underrepresented among land use scientists. However, the low publication share by women could be attributed to the fact that women submit fewer papers than men (Fisher et al., Citation2020) or that men have a double chance of being invited by journals to submit papers (Holman et al., Citation2018). In contrast, Lerback and Hanson (Citation2017) observed that journals of American Geophysical Union accepted papers with women as first authors at a higher rate than their counterparts and a similar observation was made when disaggregated by age of the first author.

Other studies have found that the lower representation of women among authors might be a consequence of women being more likely to leave academic careers due to persistent traditional gender roles (Abramo et al., Citation2021; Holman et al., Citation2018; Ledin et al., Citation2007; Shamseer et al., Citation2021; Van Arensbergen et al., Citation2012), in particular, in many African societies or since women are more likely to get caught up in intermediate employment levels like administrative and or teaching commitments (Sheltzer & Smith, Citation2014). However, this effect is also noticeable in other parts of the world including Europe and the US, where women are more likely to reduce time devoted for research under increasingly challenging situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Squazzoni et al., Citation2020; Viglione, Citation2020; Vincent-Lamarre et al., Citation2020).

Authorship position relates to seniority and establishment of the author (Wren et al., Citation2007). Although the gap between male and female first authorships is closing, the rate is very slow with only 1.8% per year. This gap is even bigger for the last authorship position or those publications with single author. This implies that the share of female graduates, PhD students, postdocs and early career scientists in land use science, who in many instances make up the first authors, is increasing with time. However, the low number of women as last authors also indicates a leaky pipeline in the female’s progressive science career. The same was also observed by Larivière et al. (Citation2013) and West et al. (Citation2013) where the number of women as last authors even decreased over time. Women likely abandon academia upon completion of graduate or postdoctoral training which is likely related to biological constraints when it comes to childbearing at a higher age and a tendency of women to take over a bigger share of care-taking tasks (Fisher et al., Citation2020). Of the 6.9% of the single-authored articles that we found, the share of men as authors was higher than that of women. This gap between men and women single authors is closing, however, its presently still wide. We argue that women publishing comparatively less than their male counterparts could signify (1) their inability to take up responsibilities for leadership roles in science and (2) it could indicate that they are challenging the dominant styles and pressures of publishing single-authored articles by preferring collaborative science as evidenced by the high numbers of articles authored by two or more (93.1%) authors (Schucan Bird, Citation2011). However, Fox (Citation2001) found that women were likely not to collaborate in author teams because they feel uncomfortable contributing and speaking in group meetings and within departments, they are less likely to be respected or taken seriously than men. Notwithstanding, Wren et al. (Citation2007) observed an increasing trend of the number of authors per journal article in 2006 in comparison to a conservatively more single-authored era from 1966 to 1996, which could explain the high number of women as middle authors as well as the average number of authors per study. The increasing numbers of women as middle authors but not as last authors might also indicate women’s reluctance to take on senior positions and a tendency to execute rather supporting roles in science (Vaughan et al., Citation2019). Moreover, it could signify the existing structural bottlenecks, e.g. conscious and unconscious discrimination of women. Whatever the reasons might be, we are convinced that the low number of women as last and sole authors indicates their underrepresentation especially in leadership positions (Maas et al., Citation2021).

Similarly, the average citation of journal articles that are authored by women either as first or as sole authors is significantly lower than that of men. Similar results in sole authored papers were observed by Larivière et al. (Citation2013), where the average relative citation of female authors was <1. Furthermore, average citations of papers with female authors as first or last authors disaggregated by collaboration level (national or international) were also cited less than those with male authors (Bendels et al., Citation2018; Larivière et al., Citation2013). These results might indicate that women shy away from self-promotion of their work unlike men, a general lower level of acceptance of studies authored by women or their preference for other forms of publications like in grey literature (Tushingham et al., Citation2017). We would argue that this might also be a result of a lower share of publications in high-ranking journals. Bendels et al. (Citation2018) found that out of 54 journals only 5 had equal chances for women being able to secure authorships while men had higher odds to be last authors in all journals. Furthermore, a presence of old-boy networks and subsequent citation behavior could explain the underrepresentation of women (Massen et al., Citation2017).

Ethnic disparity

Our findings show that the share of ‘Asian’ authors is increasing more significantly over time compared to other ethnic groups, while the share of contributions from ‘White’ authors is decreasing. From our data, we cannot derive reasons for this phenomenon. We would however, argue that population increase coupled with increasing investments in education, research and development in many Asian countries could be potential drivers of the seen trend. For instance, according to UNESCO data on research and development (UNESCO, Citation2021), there is a general increase in expenditure on research and development in (in descending order) North America, Asia (Eastern), Oceania and Europe, with all of them being above 1.5% gross expenditure of their GDP. The share of ‘White’ authors is observed to decline (), which we attribute to the increasing numbers of other ethnicities, in particular, ‘Asian’ authors. Based on a survey of the publishing authors, Hopkins et al. (Citation2013) found that ‘White’ authors represented 81%, ‘Asian’ 10%, ‘Hispanic’ 5% and ‘Black’ <1%. Our results indicate that ‘White’ authors dominated land use science up to 2018 and since then, the share of ‘Asian’ authors started increasing with a proportion of 47.3% versus 44.9% of ‘White’ authors in 2019. Regardless of the change in proportion of ‘White’ authors, they are still more likely to head research teams and are likely to be cited more than other ethnic groups. Hofstra et al. (Citation2020) working in US found that contribution from minority groups (majorly non-white) despite being novel and innovative, was less likely to be acknowledged. Shares of ‘Hispanic’ and ‘Black’ authors have consistently remained very low regardless of increasing population in continents where these ethnic groups represent the population majority. For example, the population in Africa reached 1.3 billion in 2019 and is projected to increase up to 1.6 billion by 2030, a growth rate of almost 30% (UN DESA, Citation2019). Despite their significant share in the world population of 16.9% in 2019 (UN DESA, Citation2019), in particular, ‘Black’ authors continue to be underrepresented in scientific studies focusing on land use. Although we might underestimate the share of authorships of ‘Hispanic’ and ‘Black’ scientists by excluding journal articles published in languages like Spanish and French, which are predominantly spoken in several countries of the Global South, we are convinced that their viewpoints are often underrepresented in author teams.

The increasing population size in many countries in Latin America, Africa and Asia coupled with accelerating pressures from global change and increasing resource demands from countries of the global North will continue to amplify existing land use pressures and conflicts. At the same time, research and development expenditure in the Global South continues to remain below 1% of the GDP for gross expenditures on research and development in Latin America, Africa and Asia (Central). This, under allocation of budgetary resources, increases dependency on research funding through projects sponsored by scientists from the global north, which in most cases turns into a ‘helicopter research’ (Minasny & Fiantis, Citation2018; Pettorelli et al., Citation2021). Published outputs of such funded projects are done by scientists of the global north either taking first, last or both author positions (Hazlett et al., Citation2020; Nuñez et al., Citation2019). Subsequently, complains from global south scientists show that their involvement in the research activities are reduced to logistical roles and where their input is considered in the journal articles, they do not take the first positions (Minasny & Fiantis, Citation2018). Such opportunistic collaboration can foster mistrust, resentment, inadequate research approaches leading to misinterpretation of research outputs (Pettorelli et al., Citation2021) and compromising management of land, land use and systems in places that would benefit the most. Whilst the investing in research in the global south by the global north scientists is not necessarily problematic per se (Hulme, Citation2011; Mammides et al., Citation2016; Nuñez et al., Citation2019), there is an urgent need to increase the ethnic diversity in land use science not only a matter of political correctness but also as a way to integrate different viewpoints, norms and values, which might not be as well captured by researchers from the Global North but highly relevant for the development of sustainable land use practices.

Intersection of gender and ethnicity

In our study, we found a gap between the proportion of female publishing authors in all ethnicities. This is an indication of an enduring worldwide underrepresentation of female scientists, irrespective of their ethnic groups. However, while the gap is slowly closing in ‘Hispanic’, ‘White’ and ‘Asian’ ethnicities, there seems to be no change in gender equality among ‘Black’ authors (). These results are in line with findings by Nelson and Rogers (Citation2003) on diversity in doctoral studies of science and engineering, who found a gap between female and male students in all classified ethnicities, which was more pronounced for ‘Black’ authors and doctoral students. In terms of author positions, first, last and sole authorship positions are also more likely to be taken by ‘White’ female authors, followed by ‘Asian’ female authors. ‘Black’ women’s representation in either position is low and slightly higher in sole authorship positions relative to other positions.

These results show that in particular ‘Black’ women are underrepresented in the scientific land use community. One reason might be that they are consciously choosing other fields or altogether other career paths (Archer et al., Citation2015; Riegle-Crumb et al., Citation2019). Riegle-Crumb et al. (Citation2019) showed that the rate of black students switching or leaving STEM field was 19% higher than for white students, instigated by social classes, persistent stereotypes of presumption of inferiority in STEM majors and possibly their alignment of success to giving back to community in which they consider non-STEM majors like business and humanities to be more compatible with. Coming back to land use science, ‘black’ women are likely to be engaged in roles that give them more satisfaction in the posit of value for community/society. These roles may range from supervision and mentoring of students to field data collection.

When gender and ethnicity intersect, our findings reveal severe underrepresentation by share of female authors, position of the author and citation of ‘Hispanic’ and ‘Black’ women in land science. The underrepresentation continues to persist in the 21st century. Hofstra et al. (Citation2020) working with longitudinal data of 38 years found that science produced by gender and ethnic minority groups is highly likely to be devalued and consequently accrue lower citations, which might explain the low share of female senior authorship positions. In addition, Archer et al. (Citation2015) found that the aspirations of ‘Black’ women in science are shaped by the intersection of these inequalities and when social class is included their science aspirations are further lessened.

Furthermore, the intersection of these inequalities limits the diversity not only of leadership but of innovations that are necessary in addressing the SDGs. These inequalities elicit concerns in the context of an increasing population, accelerating land use pressures from domestic and non-domestic land use needs, the eminent risk for biodiversity rich areas in the Global South (Leclère et al., Citation2020). Inclusion of gender and ethnic minorities would highly benefit land use systems and the importance of a diverse research community could not be any greater at this point.

Limitations

The conclusions of this study are limited in different ways. One bias might be due to the potential of the used gender and ethnicity assessment tools of introducing biases (see Methods), which might lead to an over- or under-representation of certain groups. However, as error margins are relatively low (between 2%-5% according to Santamaría & Mihaljević, Citation2018; Teele and Thelen, Citation2017), we would argue that the results are still valid and robust.

Another bias of our study might be the result of including English articles exclusively. While other languages are certainly the exception rather than the rule and even most articles written in other languages provide English abstracts, this limitation has the potential to cause a certain bias. In particular in Latin America, many authors publish in Spanish journals, which we did not consider in this study. At the same time, this might also be the case for a certain share of articles being published in Chinese, French or German journals and we would argue that this bias is likely to be more or less consistent across all ethnic groups. We also only included journal articles and excluded all other forms of publications such as book chapters, reports, conference proceedings among others. While we do not want to deprive these publications of their scientific merit, we chose to focus on peer-reviewed journal articles to assure a certain scientific standard and since a comprehensive inclusion of other publication formats would have required the coverage of other databases such as Google Scholar, which has a much better coverage of grey literature and other formats, but was outside of the scope of this study.

For academic hierarchy and application of research grants, scholarly productivity in terms of peer reviewed journal articles and its attributes plays a key role. While we are aware of other metrics like the use of new format curriculum vitae inspired by the San Francisco Declaration of Research Assessment (DORA) (Hatch & Curry, Citation2020), we focused on authorship positions and citations as attributes of scholarly productivity. Academic careers are driven by a more diverse set of activities than publishing. In such, women may not be as productive in terms of publications as their male counterparts, as evidenced by the results, yet contribute significantly to the scientific debate e.g. through public outreach or supervision of students. In addition, the found gender imbalance in authorship positions may be influenced by some publications following the approach of some studies listing authors in alphabetical order instead of their contributions.

Conclusions and implications

Our analysis indicates that women are underrepresented in land use science as other authors have found for different scientific disciplines. While we found a positive trend in terms of a closing gender gap over time, we argue that it comes at a very slow pace. Ethnicity, similar to gender, plays a key role in land use science, and ‘Black’ and ‘Hispanic’ authors remain marginalized in this discipline. Intersection of gender and ethnicity marginalizes, in particular, ‘Hispanic’ and ‘Black’ women as publishing authors, as senior authors and in terms of citation rates. ‘White’ men continue to dominate land use science. Disregarding diverse viewpoints from women of all ethnicities in land use science will diminish our chances to reach the SDGs and to manage land sustainably in the future.

So, what can be done to level the playfield? Supportive actions to empower women are needed to further reduce the gap between men and women as well as between different ethnic groups in scholarly output. Such actions might include an active encouragement and support of scientists from minority groups to write and submit papers to journals. To encourage more submissions, journals should also have favorable terms, for example, Mammides et al. (Citation2016) found a general significant lower rate of acceptance of manuscripts of authors from non-high income countries in comparison to authors of higher income countries in both high and low impact factor conservation journals. Most importantly, efforts should target the sealing of the leaks in the pipeline of academic careers through provisioning of better working conditions for women. The establishment of women’s quota in senior academic positions, the financial and organizational support of male and female researchers during parental leave, mentoring programs for young female researchers or equal opportunities for grants are just a few examples of measures that would support women to continue their career in academic research. Moreover, a long-term solution would be to develop stronger institutional capacity for researchers in the global south to ultimately bridge the gap. Furthermore, stricter ethical considerations should be outlaid and adhered to especially where research collaboration between researchers of global south and north is happening to devoid it of parachute research while also increasing the visibility of global south researchers. Furthermore, it is necessary to support careers of female researchers from the Global South to reduce systemic stereotypes and discrimination of ‘Black’ and ‘Hispanic’ female scientists. Predominantly patriarchal societies are more pronounced in many countries of the Global South, but can also still be found in the Global North. Overcoming patterns of systemic discrimination will be much more likely if there is an active process of creating and supporting role models and future female land use research champions for future generations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Hannah Kamau and Uyen Tran share first authorship.

References

- Abramo, G., Aksnes, D.W., & D’Angelo, C.A., et al. (2021). Gender differences in research performance within and between countries: Italy vs Norway. Journal of Informetrics, 15(2), 101144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2021.101144

- Abramo, G., Andrea D’angelo, C., & Caprasecca, A., et al. (2009). Gender differences in research productivity: A bibliometric analysis of the Italian academic system. Scientometrics,79(3), 517–539 .https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-007-2046-8

- Andersen, J.P., Schneider, J.W., Jagsi, R., & Nielsen, M.W., et al. (2019). Gender variations in citation distributions in medicine are very small and due to self- citation and journal prestige. ELife, 8, e45374 . https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.45374

- Archer, L., Dewitt, J., & Osborne, J., et al. (2015). Is science for us? black students’ and parents’ views of science and science careers. Science Education, 99(2), 199–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21146

- Bendels, M.H.K., Müller, R., Brueggmann, D., & Groneberg, D.A., et al. (2018). Gender disparities in high-quality research revealed by nature index journals. PLOS ONE, 13(1), e0189136. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189136

- Conover, W.J., & Iman, R.L. (1981). Rank transformations as a bridge between parametric and nonparametric statistics The American Statistician. 35(3), 124–129. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2683975

- Cook, N.J., Grillos, T., & Andersson, K.P., et al. (2019). Gender quotas increase the equality and effectiveness of climate policy interventions. Nature Climate Change, 9(4), 330–334. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0438-4

- Crenshaw, K.W. (n.d.). Demarginalising the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of anti-discrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and anti-racist politics University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315582924-10

- Dawson, L., Brevik, E.C., & Reyes-Sánchez, L.B., et al. (2021). International gender equity in soil science. European Journal of Soil Science, 72(5), 1929–1939. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.13118

- de Mendiburu, F. (2020). agricolae: statistical procedures for agricultural research CRAN Repository. https://cran.r-project.org/package=agricolae

- Dion, M.L., Sumner, J.L., & Mitchell, S.M., et al. (2018). Gendered citation patterns across political science and social science methodology fields. Political Analysis, 26(3), 312–327https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.12

- Dowle, M., & Srinivasan, A. (2021). data.table: extension of `data.frame`. CRAN Repository. https://cran.r-project.org/package=data.table

- Fisher, M., Nyabaro, V., Mendum, R., & Osiru, M., et al. (2020). Making it to the PhD: gender and student performance in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE, 15(12 December), e0241915. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241915

- Fonjong, L., Fombe, L., & Sama-Lang, I., et al. (2013). The paradox of gender discrimination in land ownership and women’s contribution to poverty reduction in anglophone cameroon. GeoJournal, 78(3), 575–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-012-9452-z

- Fortin, J., Bartlett, B., Kantar, M., Tseng, M., & Mehrabi, Z., et al. (2021). Digital technology helps remove gender bias in academia. Scientometrics, 126(5), 4073–4081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-03911-4

- Fox, M.F. (2001). Women, science, and academia: graduate education and careers. Gender and Society, 15(5), 654–666. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3081968. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124301015005002

- Franke, T.M., Ho, T., & Christie, C.A., et al. (2012). The chi-Square test. American Journal of Evaluation, 33(3), 448–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214011426594

- Fu, B., Wang, S., Zhang, J., Hou, Z., & Li, J., et al. (2019). Unravelling the complexity in achieving the 17 sustainable-development goals. National Science Review, 6(3), 386–388. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwz038

- Fuchs, S., Brewka, M., Allmendinger, J., & Ludwig, W., et al. (1998). Gender Disparities in Higher Education and Academic Careers in Germany and the United States. In Policy Papers (Vol. 7)Washignton, D.C.: American Institute for Contemporary German Studies.

- Gao, L., & Bryan, B.A. (2017). Finding pathways to national-scale land-sector sustainability. Nature, 544(7649), 217–222. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21694

- Genderize.io. (2021). Our data. https://genderize.io/our-data

- Gross, J., & Ligges, U. (2015). nortest: tests for normality. CRAN Repository. https://cran.r-project.org/package=nortest

- Hatch, A., & Curry, S. (2020). Changing how we evaluate research is difficult, but not impossible. ELife, 9(e58654), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.58654

- Hazlett, M.A., Henderson, K.M., Zeitzer, I.F., & Drew, J.A., et al. (2020). The geography of publishing in the anthropocene. Conservation Science and Practice, 2(10), e270. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.270

- Helmer, M., Schottdorf, M., Neef, A., & Battaglia, D., et al. (2017). . In eLife, 6, e21718. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.21718 .

- Hofstra, B., Kulkarni, V.V., Galvez, S.M.N., He, B., Jurafsky, D., & McFarland, D.A., et al. (2020). The diversity–innovation paradox in science Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(17), 9284–9291. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1915378117.

- Holman, L., Stuart-Fox, D., & Hauser, C.E., et al. (2018). The gender gap in science: how long until women are equally represented? PLOS Biology, 16(4), e2004956. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2004956

- Hopkins, A.L., Jawitz, J.W., McCarty, C., Goldman, A., & Basu, N.B., et al. (2013). Disparities in publication patterns by gender, race and ethnicity based on a survey of a random sample of authors. Scientometrics, 96(2), 515–534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0893-4

- Huang, J., Gates, A.J., Sinatra, R., & Barabási, A.L., et al. (2020). Historical comparison of gender inequality in scientific careers across countries and disciplines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(9), 4609–4616. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1914221117 .

- Hulme, P.E. (2011). Practitioner’s perspectives: Introducing a different voice in applied ecology. Journal of Applied Ecology, 48(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01938.x

- Kaplan, J. (2021). predictrace: predict the race and gender of a given name using census and Social security administration data. Github Repository. https://github.com/jacobkap/predictrace

- Kassambara, A. (2021). rstatix: pipe-Friendly framework for basic statistical tests. CRAN Repository. https://cran.r-project.org/package=rstatix

- Larivière, V., Ni, C., Gingras, Y., Cronin, B., & Sugimoto, C.R., et al. (2013). Bibliometrics: global gender disparities in science. Nature, 504(7479), 211–213. https://doi.org/10.1038/504211a

- Leclère, D., Obersteiner, M., Barrett, M., Butchart, S.H.M., Chaudhary, A., De Palma, A., DeClerck, F.A.J., Di Marco, M., Doelman, J.C., Dürauer, M., Freeman, R., Harfoot, M., Hasegawa, T., Hellweg, S., Hilbers, J.P., Hill, S.L.L., Humpenöder, F., Jennings, N., Krisztin, T., & Young, L., et al. (2020). Bending the curve of terrestrial biodiversity needs an integrated strategy. Nature, 585(7826), 551–556. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2705-y

- Ledin, A., Bornmann, L., Gannon, F., & Wallon, G., et al. (2007). A persistent problem. Traditional gender roles hold back female scientists. EMBO Reports, 8(11), 982–987. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7401109

- Lerback, J., & Hanson, B. (2017). Journals invite too few women to referee. Nature, 541(7638), 455–457. Nature Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1038/541455a

- Maas, B., Pakeman, R.J., Godet, L., Smith, L., Devictor, V., & Primack, R., et al. (2021). Women and global south strikingly underrepresented among top-publishing ecologists. Conservation Letters, 14(4) , e12797. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12797

- Mammides, C., Goodale, U.M., Corlett, R.T., Chen, J., Bawa, K.S., Hariya, H., Jarrad, F., Primack, R.B., Ewing, H., Xia, X., & Goodale, E., et al. (2016). Increasing geographic diversity in the international conservation literature: A stalled process?. Biological Conservation, 198,78–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.03.030

- Massen, J.J.M., Bauer, L., Spurny, B., Bugnyar, T., & Kret, M.E., et al. (2017). Sharing of science is most likely among male scientists. Scientific Reports 2017 7:1, 7(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13491-0

- McHugh, M.L. (2013). The chi-square test of independence. Biochemia Medica, 23(2), 143–149 . https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2013.018

- Microsoft-Corporation. (n.d.). Microsoft Excel (18.2104.12721.0). https://office.microsoft.com/excel

- Minasny, B., & Fiantis, D. (2018). “Helicopter research”: Who benefits from international studies in Indonesia?. The Conversation. Accessed26 10 2021. https://theconversation.com/helicopter-research-who-benefits-from-international-studies-in-Indonesia-102165

- Morales, M., & Murdoch, D. (2020). sciplot: scientific graphing functions for factorial designs CRAN Repository . https://cran.r-project.org/package=sciplot

- Nelson, D.J., & Rogers, D.C. (2003). A national analysis of diversity in science and engineering faculties at research universities. Washington, DC: National Organization for Women.

- Nelson, L.S. (1998). The Anderson-Darling test for normality. Journal of Quality Technology, 30(3), 298–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224065.1998.11979858

- Nuñez, M.A., Barlow, J., Cadotte, M., Lucas, K., Newton, E., Pettorelli, N., & Stephens, P.A., et al. (2019). Assessing the uneven global distribution of readership, submissions and publications in applied ecology: obvious problems without obvious solutions. Journal of Applied Ecology, 56(1), 4–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13319

- Pettorelli, N., Barlow, J., Nuñez, M.A., Rader, R., Stephens, P.A., Pinfield, T., & Newton, E., et al. (2021). How international journals can support ecology from the Global South. Journal of Applied Ecology, 58(1), 4–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13815

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org/

- Riegle-Crumb, C., King, B., & Irizarry, Y., et al. (2019). Does STEM stand out? examining racial/ethnic gaps in persistence across postsecondary fields. Educational Researcher, 48(3), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19831006.

- RStudio Team. (2019). RStudio: integrated development environment for R (1.2.5033). RStudio, Inc. http://www.rstudio.com/

- Santamaría, L., & Mihaljević, H. (2018). Comparison and benchmark of name-to- gender inference services. PeerJ Computer Science, 2018(7), e156. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.156

- Schucan Bird, K. (2011). Do women publish fewer journal articles than men? sex differences in publication productivity in the social sciences. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 32(6), 921–937. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2011.596387

- Shamseer, L., Bourgeault, I., Grunfeld, E., Moore, A., Peer, N., Straus, S.E., & Tricco, A.C., et al. (2021). Will COVID-19 result in a giant step backwards for women in academic science? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.004

- Sheltzer, J.M., & Smith, J.C. (2014). Elite male faculty in the life sciences employ fewer women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(28), 10107–10112. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1403334111

- Squazzoni, F., Bravo, G., Grimaldo, F., Garcıa-Costa, D., Farjam, M., & Mehmani, B., et al. (2020). Only second-class tickets for women in the COVID-19 race. A study on manuscript submissions and reviews in 2329 Elsevier journals. PLoS ONE, 16(10), e0257919 . https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3712813

- Tao, Y., Hong, W., & Ma, Y., et al. (2017). Gender differences in publication productivity among academic scientists and engineers in the U.S. and China: similarities and differences. Minerva, 55(4), 459–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-017-9320-6

- Teele, D.L., & Thelen, K. (2017). Gender in the journals: publication patterns in political science. PS: Political Science & Politics, 50(2), 433–447. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096516002985

- Tushingham, S., Fulkerson, T., & Hill, K., et al. (2017). The peer review gap: A longitudinal case study of gendered publishing and occupational patterns in a female-rich discipline, Western North America (1974–2016). PLoS ONE, 12(11), e0188403. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188403

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2021). United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. United Nations.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2019). World Population Prospects 2019. Data Booklet(ST/ESA/SER.A/424).United Nations.

- van Arensbergen, P., van der Weijden, I., & van Den Besselaar, P., et al. (2012). Gender differences in scientific productivity: A persisting phenomenon? Scientometrics, 93(3), 857–868. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0712-y

- Vaughan, K., Van Miegroet, H., Pennino, A., Pressler, Y., Duball, C., Brevik, E.C., Berhe, A.A., & Olson, C., et al. (2019). Women in soil science: growing participation, emerging gaps, and the opportunities for advancement in the USA. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 83(5), 1278–1289. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2019.03.0085

- Viglione, G. (2020). Are women publishing less during the pandemic? here’s what the data say. Nature, 581(7809), 365–366. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01294-9

- Villamor, G.B., Desrianti, F., Akiefnawati, R., Amaruzaman, S., & van Noordwijk, M., et al. (2014). Gender influences decisions to change land use practices in the tropical forest margins of Jambi, Indonesia. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 19(6), 733–755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-013-9478-7

- Vincent-Lamarre, P., Sugimoto, C.R., & Larivière, V., et al. (2020). Monitoring women’s scholarly production during the COVID-19 pandemic. Github Repository .https://github.com/lamvin/manuscripts-tracker

- Wais, K. (2016). Gender prediction methods based on first names with genderizeR. R Journal, 8(1), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.32614/rj-2016-002

- West, J.D., Jacquet, J., King, M.M., Correll, S.J., & Bergstrom, C.T., et al. (2013). The role of gender in scholarly authorship. PLoS ONE, 8(7), e66212. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066212

- Whelan, A.M., & Schimel, D.S. (2019). Authorship and gender in ESA journals. The Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America, 100(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/bes2.1567

- Wickham, H. (2016). ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag NewYork.978-3-319-24277-4. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org

- Wickham, H. (2021). tidyr: tidy messy data R package version 1.1.4. CRAN Repository. https://cran.r-project.org/package=tidyr

- Wickham, H., Averick, M., Bryan, J., Chang, W., McGowan, L.D., Francois, R., Grolemund, G., Hayes, A., Henry, L., Hester, J., Kuhn, M., Pedersen, T.L., Miller, E., Bache, S.M., Mueller, K., Ooms, J., Robinson, D., Seidel, D.P., Spinu, V., & Yutani, H., et al. (2019). Welcome to the tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software, 4(43), 1686. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01686

- Wickham, H., Francois, R., Henry, L., & Mueller, K., et al. (2021). dplyr: A grammar of data manipulation R package version 1.0.7. CRAN Repository. https://cran.r-project.org/package=dplyr

- Wickham, H. (2007). Reshaping data with the reshape package. Journal of Statistical Software, 21(12),1–20. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v021.i12

- Wren, J.D., Kozak, K.Z., Johnson, K.R., Deakyne, S.J., Schilling, L.M., & Dellavalle, R.P., et al. (2007). The write position. A survey of perceived contributions to papers based on byline position and number of authors. EMBO Reports, 8(11), 988–991. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7401095