ABSTRACT

Adolescent young carers (AYCs) are a sub-group of young carers who carry out significant or substantial caring tasks and assume a level of responsibility which would usually be associated with an adult. They are a potentially vulnerable group of minors because of the risk factors associated with their caring role. AYCs face a critical transition phase from adolescence to adulthood often with a lack of tailored support from service providers. The recently completed European funded ‘ME-WE’ project, which forms the focus of this paper, aimed to change the ‘status quo’ by advancing the situation of AYCs in Europe, via responsive research and knowledge translation actions. This paper outlines the participatory, co-creation approach employed in the project to optimise AYC’s involvement. It describes the ethical framework adopted by the project consortium to ensure the wellbeing of AYCs within all project activities. Ethical issues that arose in the field study work in all six countries are presented, followed by a discussion of the level of success or otherwise of the consortium to address these issues. The paper concludes with lessons learned regarding ethically responsible research with and for AYCs that are likely transferable to other vulnerable research groups and pan-European projects.

Introduction

Young carers are children who carry out, often on a regular basis, significant or substantial caring tasks and assume a level of responsibility which would usually be associated with an adult (Becker Citation2000). Young carers are a potentially vulnerable group of minors because of the risk factors associated with their caring role of a family member or significant other. More intense amounts of caring over a prolonged time has been shown to have a negative impact on young carers’ mental and physical health and impact on their school performance and attendance, which in turn can affect their future employment opportunities and life chances (Becker and Sempik Citation2018).

The study of young carers has developed in the last two decades, especially in the United Kingdom (UK) and is now an expanding field in several countries across geographical regions, especially Europe, namely Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Austria, Italy, Slovenia, Germany, France, and Norway (Leu and Becker Citation2017; Leu et al. Citation2022). Despite the strides made in understanding the experiences of European young carers through scholarly research, young carers remain a marginalised group of children and young people. Much of their marginalised status can be attributed to the vulnerability of their young age without full legal or societal recognition as carers in most European countries. Furthermore, their association with individuals also possessing a marginalised position in society, i.e. older and/or disabled people, people living with mental illness, and/or substance abuse, increases the likelihood that young carers experience similar stigma and discrimination. LGBTQ + young carers, disabled young carers, refugee and immigrant young carers, Black and minority ethnic young carers have identities that are further disenfranchised (Jones, Jeyasingham, and Rajasooriya Citation2002; Children’s Society Citation2013; Traynor Citation2016). Thus, some children may not wish to be labelled as a young carer because of the stigma related to illness, disability, and addiction. Youths who do not identify with the ‘young carer’ label may be overlooked in young carer specific study recruitment efforts or be disengaged with formal services (Children’s Commissioner for England Citation2016). As a result of the stigma and discrimination affecting young carers and their care recipients, many school staff, health and social care professionals, decision makers and policy makers remain unaware of their situation (Aldridge Citation2018).

Few research studies have solely focused on the ethics of conducting research with young carers and young adult carers; although research has acknowledged that young carers are ‘hidden’, ‘hard to reach’, and ‘vulnerable’, and that research with this population of young people can be ‘challenging’ (Kennan, Fives, and Canavan Citation2012; Robson Citation2001). One study in England recognised that young carers are a hidden population and therefore representative sampling would be difficult to obtain (Gowen et al. Citation2021). Lewis (Citation2018), in her qualitative work with young adult carers in the UK and US, found that because the research was conducted in a country with low young carer awareness, i.e. the US, the research recruitment process acted as a method of identifying young carers for the first time. Lewis (Citation2018) described an ethical dilemma that was manifested by identifying young adult carers for the first time and the question of whether the researcher had an ethical responsibility to connect the research participant to formal support services because of their ‘newly discovered’ caring role. Other research has focused on the agency of young carers as both active participants in their family life and the research process, rather than passive subjects (Smyth and Michail Citation2010). Such a view recognises that young people with caring responsibilities are experts in their own lives and can express opinions about matters that affect them. As a continuation of active participation in research, co-production has emerged as a way for young carers and young adult carers to have meaningful involvement in the research process (Newman, Carey, and Kinney Citation2022). However, co-production with vulnerable young people is not without its own set of ethical challenges, such as the risk of over-burdening already time-poor participants and the balance of risk reduction strategies and protection versus engagement (Amman and Sleigh Citation2021; Liabo, Ingold, and Roberts Citation2017). Nonetheless, the value of co-production as a research method with young carers has gained ground by recognising the citizenship of young carers (Wihstutz Citation2017).

The primary target group for the recently completed ME-WE research and innovation project (Hanson et al. Citation2022), funded by the European Union and which forms the focus of this paper, is adolescent young carers (AYCs) aged 15–17 years of age. AYCs face a critical transition phase from adolescence to adulthood, whilst balancing caring commitments and manoeuvring the challenges of school/college work, applying for university and getting a job, with relatively little if any tailored support from service providers (Hanson et al. Citation2022). The ME-WE project,Footnote1 ‘Psychosocial support for promoting the mental health and wellbeing among adolescent young carers in Europe’ aimed to improve the situation of young carers in Europe via its three main objectives which can be summarised as follows:

To systematise knowledge on AYCs by (a) identifying their profiles, needs and preferences; (b) analysing national policy, legal and service frameworks operating in the partner countries of Sweden, the Netherlands, Italy, Slovenia, Switzerland and the UK and (c) reviewing existing good practices, social innovations and evidence;

To co-design, develop and test, together with AYCs and other stakeholders, a framework of effective and multicomponent psychosocial interventions for primary prevention focused on improving AYCs’ mental health and wellbeing to be tailored to each country context;

To carry out wide knowledge translation actions for dissemination, awareness promotion and advocacy by sharing results among relevant stakeholders at national, European and international levels.

The aims of this paper are to: (1) describe the ethical governance framework that was adopted by the project consortium to ensure the integrity and wellbeing of AYCs at all times within the project, in compliance with national and European regulations and guidelines and mirroring the current ‘state of the art’ concerning research with potentially vulnerable minors; (2) present the core ethical issues that arose in the field study work involving AYCs in all six partner countries; (3) discuss the level of success or otherwise of the project consortium to address the main ethical issues, with reference to ethical principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice where appropriate; (4) conclude with major lessons learned in relation to ethically responsible research with and for AYCs that may be transferable to other vulnerable research groups and pan-European projects.

Materials and methods

The over-arching design centred on a participatory, co-creation approach in order to achieve the core aims of the project. At a project consortium level, the six partner countries mainly each consisted of a research organisation/university and a carers organisation (or equivalent) working together, in addition to the European NGO, Eurocarers.Footnote2 In fact, all project partners were members of Eurocarers, which meant that researchers and members of carers organisations were accustomed to working together and shared common interests and concerns to advance the situation of informal carers across Europe, by more evidence-based policy making and advocacy work. In the context of the ME-WE project, the project consortium endorsed a social justice ethical perspective with regards to the situation of young carers, recognising the importance of raising awareness of the situation of young carers more broadly, and AYCs in particular, in Europe. The project sought to bring about changes in policy and practice based on the project outcomes that would ultimately enable AYCs to thrive and pursue their life goals with equal opportunities to those adolescents without caring responsibilities (Hanson et al. Citation2022).

Key ethical principles that underpinned the ethical governance framework and guided the co-creation with young carers and other project work centred on (i) respect for persons, (ii) autonomy, (iii) beneficence and non-maleficence and (iv) justice. Respect for persons involved treating young carer participants in ways that promoted their personhood and dignity at all times. In essence, this centred on the classic deontological tenet of treating others in the way/s in which we ourselves would like to be treated. In communications with young carers, this involved actively listening to their views and experiences throughout the project and continually recognising their inputs to the project activities (Phelps Citation2017). This is evidenced in the participatory, co-creation approach adopted in the project (see details below). Aldridge (Citation2020) specifically names co-production as a research approach that possesses the creativity and inclusion necessary to conduct research with young carers. As well, an operationalisation of the principle of respect for persons in our research were the procedures of ensuring that AYCs (and their parents) did not feel forced to reveal any personal information (of the young carer and/or care recipient) if they preferred not to share. For example, AYCs could skip questions in the survey but also in the Blended Learning Network (BLN) sessions (see details below). Second, autonomy related to the project consortium and professional stakeholders seeing and valuing young carers as individuals with the capacity to develop and express their own opinions and make decisions regarding their lives in general, in keeping with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations Citation1989), and, with regards to their caring situation in particular (Boyle Citation2020). This is especially seen in the framework of the BLNs and in the ME-WE intervention and the DNA-V philosophy (see below). Third, beneficence and non-maleficence involved project partners and professional stakeholders, striving at all times to ‘do good’ by promoting the wellbeing of AYCs and to prevent causing them any harm during the course of the project activities, and especially with regards to the clinical trial study (see ‘Results’ section). Kettell (Citation2018) also argued that that the principles of beneficence exact a duty on researchers, professionals, and practitioners working with young carers. In our project we also valued that AYCs could benefit themselves from participation, for example, by acknowledging their participation with certificates (see ‘Discussion’ section). Finally, justice in the context of the project involved the project partners and professional stakeholders striving to promote fair and equitable treatment of all AYC participants, as seen in the running of the ME-WE groups within the clinical trial study and the management of the compassionate cases (see ‘Results’ section).

The main aim of the participatory, co-creation approach adopted in the project was to hear the voices of young carers, given their marginalised situation in many countries. To help actualise this goal, a variety of methods were employed to facilitate the involvement of young carers in all the core project objectives. Blended Learning Networks were set up in all six partner countries and sessions took place every six to ten weeks throughout the duration of the 41 months project (Hanson et al. Citation2022). In addition, user groups and workshops were held with AYCs for the co-design of the dedicated ME-WE app that formed part of the intervention. Further, young carers and young adult carers (18–25 years oldFootnote3) were consulted about project activities and the intervention at sessions of the Eurocarers Young Carers Working Group. Young adult carers also actively participated in the project’s International Advisory and Ethics Board (see ‘Results’ section below) and in the planning and implementation of the project’s Final Conference which was merged with the 3rd International Young Carers Conference.Footnote4 In this way, the end users within the project as a whole consisted more broadly of young carers, and where appropriate, adult young carers. Whereas, the primary target group for the co-design, implementation and evaluation of the ME-WE support intervention consisted of a sub-group of young carers, namely AYCs.

In addition, the project consortium also deemed it important to hear the voices of key stakeholders who work with, meet and/or have a responsibility for the wellbeing of young carers in the six partner countries: namely, school staff, health and social care practitioners and decision makers (health and social care managers, school headteachers) and representatives from civil society.

See below for an overview of the methods employed by the project and the specific participatory research methods used to genuinely engage with young carers and stakeholder groups in all project phases.

Table 1. Overview of research methods employed in the ME-WE project.

For the purposes of this paper, we draw primarily, but not exclusively, on the work conducted in four Work Packages (WPs) (namely Project Management; Implementation; Evaluation and Impact; Knowledge Translation, Dissemination and Communication) and accompanying deliverables (Hanson et al. Citation2021; Boccaletti et al. Citation2019; Hlebec et al. Citation2021; Centola et al. Citation2021), that are subsequently presented in the ‘Results’ section below.

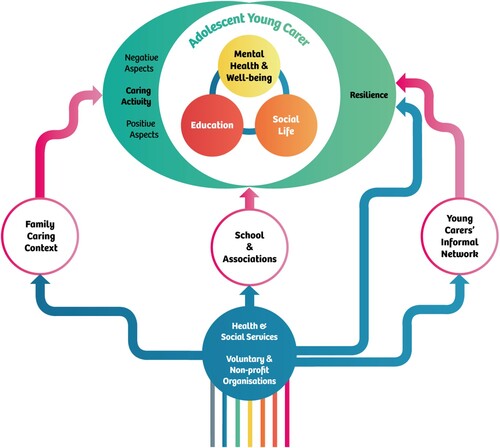

The focal point is the ethical issues arising from the field study in all six countries, involving the implementation and testing of the co-designed ME-WE psychosocial intervention with AYCs. below illustrates the conceptual framework of the ME-WE intervention The conceptual framework reflects the life balance that AYCs have, which depending on schools and associations, health and social care services and civil society, together with informal support and the family caring context and caring activity, produces positive/negative impacts on the AYC’s mental health and wellbeing, as well as their education and social life. The intervention was targeted as a primary prevention in order to mitigate the risk factor of being an AYC, by empowering the young with improved resilience and enhanced social supports. The original evaluation design comprised of a randomised control study ( above), adapted to an online-based intervention after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (more details in the paragraph below).

Figure 1. The conceptual framework of the ME-WE primary prevention psychosocial support intervention (Hanson et al. Citation2022).

The ME-WE intervention model was adapted from the Discoverer, Noticer, Advisor and Values (DNA-V) model (Hayes and Ciarrochi Citation2015), which builds on the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) approach (Hayes, Strosahl, and Wilson Citation1999) to promote well-being of adolescents. The main goal of the intervention was to provide an educational journey supporting the recognition, acceptance and sharing of emotions linked to the caring experience. This would support the development of new ways and coping strategies about the caring role, as well as better self-awareness and exploration of new identities and opportunities (Hall and Sikes Citation2020). The psychosocial support intervention was provided to AYCs in seven weekly group sessions (either face-to-face or online), including home exercises in between, and a follow-up session (three months after the end of the intervention). Group moderators were two trained facilitators. Among the intervention materials, a dedicated mobile app was developed with AYCs and tested as a tool in the intervention in three countries (Sweden, Netherlands, Switzerland) with the aim of offering an additional communication and support channel among peers (other enrolled AYCs) and facilitators. The app is now publicly available in the main mobile stores.Footnote5 Additional details on the intervention are provided in below (see also Hanson et al. Citation2022).

Table 2. Overview of intervention objectives and the ME-WE young carerś mobile app.

Results

Project management: ethical governance framework

The overall ethical governance framework was put forward by the project coordinator, taking into account the requirements of the EU’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme. It was subsequently taken up and discussed and agreed on by all the partners at the development stage of the project proposal and written up in the proposal itself in the Project Management WP. This subsequently, on the approval of the project by the EU, formed part of the legally binding Grant Agreement and Consortium Agreement. The framework was subsequently implemented at the outset of the project and the accompanying documentation was developed by the consortium with feedback and inputs from an external International Advisory and Ethics Board (IAEB) accordingly to provide guidance for the project consortium.

International advisory and ethics board

The IAEB was established at the outset of the project with a monitoring role, evaluating intermediate and final project results with a focus on legal and ethical issues. The Board was comprised of eight multidisciplinary experts in the field. To ensure the voices of young carers were heard at a strategic level, in keeping with the project’s participatory, collaborative approach, there were equal numbers of young adult carers on the Board as other expert stakeholders. In total there were four young adult carers/former young carer members from Germany, Belgium, Norway and Australia respectively. Their prior lived experiences of being an AYC was recognised, together with their first-hand experiences of co-creating and running peer support services for and with young carers or engaging in research/art projects with young carers in their respective countries. Other expert stakeholders included two policy experts (EU level: Eurochild and Flemish Ministry of Health) and two world leading researchers in the field from USA (a gender specialist) and Australia (a child protection specialist). In total there were six female and two male board members. The Board met twice a year in digital meetings with the project coordinator (8 online meetings in total). Their key feedback was given to the project team at their monthly Implementation Group (IG) meetings by the PI. Board members also provided additional advice and input to the PI on an ‘as need’ basis in between meetings. The IAEB carried out a yearly ethics, gender and data management assessment and provided recommendations for the consortium (compiled into an Ethics Report by the PI that was submitted to the European Commission), which helped to assure the best quality and ethics compliance for the ongoing research. A sample of the Board’s final assessments and recommendations are highlighted in below.

Table 3. Final recommendations and feedback by the IAEB.

Ethics, gender and data manager

An overall Ethics, Gender and Data Manager (EGDM), appointed from within the coordinating partner team, was responsible for rigorous data protection at project level and to ensure that all partners involved in the R&D work were fully versed in the protocols for ethics requirements, especially with regards to all ethical matters relating to research with minors and AYCs. This took place at monthly IG meetings with all project partners and with partner country Clinical Trial Managers (CTM) at their regular CTM monitoring meetings and at a strategic level with the project’s Steering Committee. The EGDM also ensured that the consortium followed the gender management strategy. The EGDM together with the PI was responsible for co-producing the overall Ethics, Gender and Data Management Framework (EGDMF) deliverable (Hanson et al. Citation2021), with inputs from the partners, which was developed in three iterations, in order to be sufficiently responsive to the research carried out in each phase of the project (see details below).

Clinical trial managers and meetings

A Clinical Trial Manager (CTM) was designated in each of the six countries, responsible for planning and progress in the national clinical trial study and ethical application, and for leading and monitoring country data collection procedures. Online CTM meetings, co-chaired by the PI and EGDM, were held fortnightly during the set-up period and on a 4–6 weekly basis for the duration of the implementation phase of the clinical trial study, to closely monitor data collection procedures, progress at country level and to discuss compassionate cases and any other relevant matters arising.

Ethics, gender and data management framework

The goal of the EGDMF deliverable was to identify and assess the relevant ethical, legal, gender and data management aspects to be considered to ensure compliance with ethical principles, data protection legislation and gender mainstreaming issues operating at national level and at the overall project level. The EU H2020’s Ethics Requirements Checklist acted as a guide for the structure and content of the Framework (see below). The main ethics requirements were outlined, and a summary provided of how they were to be accomplished and the extent to which they had been achieved. In keeping with the project’s co-creation approach, the Framework was further developed and refined in iterations during the project with inputs and reviews by project partners and members of the IAEB as appropriate. The primary focus was on the informed consent process with potential participant AYCs for the clinical trial studies and data management procedures.

Table 4. The EU H2020 programme Ethics Requirements Checklist (2016 version) and overview of how ME-WE addressed ethics issues.

Full copies of country partners’ ethics applications and formal approvals/detailed opinions for each of the research studies/activities involving AYCs were included as appendices in the EGDMF. For example, the online survey of adolescent young carers’ needs and situation (see Leu et al. Citation2022), the original RCT study protocol for the ME-WE support intervention targeted at AYCs (see Casu et al. Citation2021) and the COVID-19 pandemic adaption of the clinical trial study (see Hanson et al. Citation2022).

The EGDMF also included a gender strategy and a data management plan that were co-produced in three iterations. The Data Management Plan (DMP) provided guidance to the partners on how to handle, organise, structure and store research data throughout the project’s research process and post-project. For the updated versions of the Framework which focused on the clinical trial study, the EU’s H2020 FAIR (Making research data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable) Data Management GuidelinesFootnote6 provided the structure for the document and all FAIR questions were discussed by the CTMs, agreed on and summarised in the DMP.

A Gender Strategy was developed to encourage partners to systematically bring equality into the ‘mainstream’ of their activities. Gender issues were considered in relation to the consortium, the whole project and specific WPs. It served as a plan of action for striving towards gender equality throughout the project. Attention was given to gendered aspects of young caring as historically research with young carers across countries has found that girls perform a higher level of caring activities and care more frequently than boys, although boys have been found to provide significant amounts of care (Boyle, Constantinou, and Garcia Citation2022). A cultural expectation that girls should perform caring roles may also work to shield and further stigmatise boys with caring roles (Akkan Citation2020). As a practical example, in creating recruitment material (such as visuals) for participation in the ME-WE clinical trial study, efforts were made so that not only pictures of girls providing care were included in the promotion materials.

In line with the Ethics in Social Science and Humanities Research of the European Commission (European Commission Citation2018), a ME-WE Clinical Trial Study Incidental Findings Policy was co-produced in two iterations by the PI, EGDM and CTMs and included in the Framework to delineate the procedures at both project and national level to safeguard the health and wellbeing of AYCs enrolled in the study and actions to be taken if team members detected that a participant AYC was deemed to be at significant (high) risk of harm. In particular, to respond to signals of participant AYCs in the ME-WE intervention experiencing problems that required professional support beyond the ME-WE intervention itself. This is referred to by the EC as ‘unintended/unexpected incidental findings’, which they define as indications of criminal activity, human trafficking, abuse, domestic violence or bullying. Signs of such situations that required extra professional attention were recognised by ME-WE facilitators during the intervention sessions and during data collection. The procedures reflected the current health and social care legislation operating in all the six countries which were clearly outlined in the Policy. However, it was noted and discussed at a CTM meeting, and subsequently outlined in the Policy that this could potentially present a dilemma for the research team on how to act, as both rules on confidentiality of any disclosed information on participants in the study applied, but at the same time the severity of the situation may have required the researchers to follow standard procedures in cases of for example, child abuse or criminal activity, by informing relevant authorities or services.

Having provided an overview of the ethical governance structure and relevant documentation that helped to guide the consortium in their research work with and for AYCs, the next section summarises the main ethical issues that arose during the project with a focus on the implementation of the co-designed ME-WE intervention with AYCs.

Implementation, evaluation and knowledge transfer: ethical considerations and issues encountered in the field study

To provide the reader with insights into the range of ethical considerations and issues encountered in field work involving AYCs, illustrative examples (that are by no means exhaustive) are summarised in and presented in turn below with reference, where appropriate, to the project’s implementation and evaluation data. It can be seen that some of the presented examples relate to more general ethical considerations when engaging in research involving minors. Nevertheless, the main focus of this paper is on those issues that are of particular relevance for the project target group of AYCs.

Table 5. Examples of ethical considerations and actions taken in the ME-WE field study work.

Informed consent process with AYCs

All country partners gained formal ethics approval from their relevant ethics committee (outlined above) for their informed consent process with AYCs both prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. A key consideration in this regard was that the legal age of consent varied across the partner countries which led to variations in the process. In Italy, parental consent is a legal requirement for young people aged 15–17 years of age and in the Netherlands and Slovenia it is a legal requirement for 15-year-olds. In the UK, parental consent is mandated as good ethical practice and likewise in the Netherlands and Slovenia for young people aged 16–17 years. Therefore, prior to COVID-19, in Italy, Netherlands and Slovenia, the parent/s and/or legal guardian of the AYC received an information sheet on the study and were given an opportunity to ask questions about their child’s participation in the study and overall ME-WE project. After reviewing the information sheet, the parent/s and/or legal guardian of the AYC were asked to sign a consent form for their child to take part in the study. In this way, only those young people whose parent/legal guardian conferred consent were allowed to participate in the study. Parental consent was collected in written form, either by mail or email.

The process varied in Sweden and Switzerland respectively where parental consent is not a legal requirement for young people aged 15–17 years. In Switzerland, participants were asked before the first session if they wished to receive an information letter for their parents/ guardians via email. Similarly, in Sweden potential participants were sent a separate email with an information letter for their parents which they were asked to forward to their parents/guardians. Where compassionate cases existed and participants were 14 years old, parental consent was sought and obtained from parents in Sweden via postal mail or email, and Switzerland via postal mail, phone or email.

Due to mobility constraints imposed by the COVID-19, consent was collected verbally in the UK through a video-call between parents/guardians and a member of the research team, which was video-recorded and archived.

In addition to more standard ethical considerations that relate to conducting research with minors, such as ensuring the information letter and consent form are child-friendly (that the language used is sufficiently easy to understand and there is appropriate use of visual images) there were also issues arising that related more specifically to the project’s target group of AYCs.

The focus group interview findings with ME-WE facilitators and field practitioners (that formed part of the project’s process evaluation data) revealed that parental consent was not always a straightforward process. For example, there were instances where an AYC wanted to participate in the study but did not wish to tell their parents and give them an informed consent form, or alternatively for their parents to be told of the study because the parent was the one for whom they were caring. This was most likely to occur in the event of a parent experiencing a mental illness or substance abuse- particularly, where the parent was not always fully aware of the problem. Second, there were situations where an AYC had approached their parents and either one or both had said no- the facilitators/field staff recognised that the AYCs concerned were those who were potentially most in need of the intervention. However, in contrast, there were occasions when the parents themselves wanted the AYCs to join the study and encouraged them to participate, whilst the AYC themselves did not always want to do so for various reasons.

In cases where both consent of AYCs and parents was required, and if there was disagreement on consent, then participants could not join the intervention and study. The procedure to obtain informed consent was designed to provide both parents and AYCs with clear and concise information on the aim of the study and type of intervention. Moreover, procedures were in place to ask any questions and address any concerns of parents or those of AYCs before making the decision to participate in the study. For example, in the Netherlands parents and AYCs could have meetings with a mentor. Procedures were carefully designed to avoid parents or AYCs feeling that they needed to disclose any information that they did not want to reveal or feeling any pressure to participate in the study. It was emphasised that participation was voluntary and could be ended at any time without the need to disclose a reason to withdraw from the study.

Recruitment of AYCs to the clinical trial study

A key challenge in the clinical trial study, which also had ethical implications, was the recruitment of AYCs to the clinical trial study (Barbabella et al. Citation2023). This is linked to the arguments made earlier in the ‘Introduction’ section which highlighted that many young carers do not tend to self-identify as carers for a variety of reasons. As a result, privacy and confidentiality issues in relation to their recruitment to the study was of paramount concern. A range of recruitment methods were adopted in the six countries. For example, AYCs were invited to participate by health and social care professionals and/or by carers organisations in several countries. Hence, the staff that contacted them were already aware of their caring situation and AYCs were more likely to be aware of being called a young carer. This was the case in Northern Italy where AYCs were signposted to the project by health and social care professionals who were already aware of their role as carers. This minimised the risk for third parties to become informed about the caring situation of the young person. Potentially eligible participants were invited to have a confidential face-to-face or telephone conversation with a psychologist who was a member of the research team member, who screened them for inclusion criteria and explained the nature of the trial. AYCs who met the inclusion criteria and were interested in participating had the opportunity to meet the psychologists in charge of the ME-WE group delivery, prior to confirming their participation. Moreover, meeting locations of the ME-WE intervention groups were chosen so as not to be labelled as settings for interventions aimed at specific groups of young people (e.g. non-medical, community-based settings), while providing maximum privacy.

In addition, recruitment channels were also employed to find ‘potential’ AYCs among general groups of young people. This was the case in Central Italy(where the awareness level is lower than in the Northern regions), the Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland who recruited AYCs in schools. In school classes, both already (self) identified AYCs and non-identified AYCs carers could be present. The latter meaning that the young person themself was not aware that the activities they performed were considered to be caring activities and that they could be labelled as young carers. Both teachers and other school staff, but also their peers could be unaware until the moment of recruitment of that young person having ill and/or disabled relatives or friends. In this situation, there is a risk of stigmatising the caring situation or to reveal more personal information than a pupil would like to share with their teachers and peers in their class. As an example of endeavouring to protect the anonymity of AYCs in school classes, in the Netherlands a three- step procedure was applied to the recruitment process: the research team began with a general ‘kick-off meeting’ to introduce the topic of young carers to all pupils in a school class and inform all pupils on the aim of the study. Next, all pupils were invited to fill in a short online survey in which not only questions on performing caring tasks to identify young carers were included, but also more general questions on whether they were familiar with the concept of caregiving in society and how they rated the information meeting. In this way, pupils could not infer from the activity of writing or typing by their peers whether their classmates were potential AYCs. In this way, the risk of exposing AYCs to potential feelings of stigmatisation and shame were mitigated. Based on the survey results, potential eligible participants were invited by their own teacher or mentor for an individual meeting in which they were informed of the study and were invited to participate. In Central Italy, the recruitment was introduced and preceded by an information campaign in five large high schools, where the researchers presented the national results of the online survey to AYCs that was carried out during the first year of the ME-WE study and left brochures and posters with contact details to be contacted by young carers privately to preserve their privacy.

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, additional recruitment strategies were put into place. Social media campaigns were conducted in several countries so that more potential AYCs could be reached. In Sweden, advertisements containing short, animated films were launched on Snapchat, Instagram and Facebook. In Switzerland, a dedicated account on Instagram linked to other social media (e.g. Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook, blogs), newsletters and a new young carers webpage were used. In the UK, a local area based social media campaign was conducted by the Carers Trust Network Partners involved in the ME-WE clinical trial study.

Sensitive management of compassionate cases

It can be argued that sensitive management of compassionate cases is pertinent to all research involving minors. In the ME-WE project, compassionate cases were defined as youths who did not meet the clinical trial’s inclusion criteria – often because they were 14 or 18 years old – but their caring situation warranted their receipt of the project intervention programme out of ‘compassion’. It was deemed to be of particular importance within the ME-WE project as in several countries where there was generally a low level of awareness of young carers, it was not uncommon for there to be no other local support available for those young carers who were interested to participate in the study, but who did not meet the inclusion criteria for participating in the ME-WE support intervention. Furthermore, even in countries where services for AYCs are more developed (e.g. UK), some compassionate cases were identified and involved for ethical reasons. In fact, during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, support services for AYCs and their ill/disabled family members either stopped completely, or went online, depriving AYCs of services/interventions that they had become accustomed to receiving pre-pandemic. Ethically, therefore, many of these cases were included as compassionate cases (considering also the psychosocial implications of the pandemic and related restrictions for the young people).

In accordance with the project’s Incidental Findings Policy, each country compassionate case was cleared on a case-by-case basis by the overall Project CTM. In the event of a more complex case, the case was taken up at a CTM meeting, assessed and agreement was reached within the group. Compassionate cases were able to participate in the intervention itself but were not formally part of the cross-country clinical trial study so that they were not included in the cross-country data analysis. The total number of compassionate cases in the intervention group across all six countries () comprised 16.7% of the total sample of enrolled AYCs who participated in the intervention (N = 312).

Table 6. ME-WE clinical trial study compassionate cases per country.

below provides an overview of the numbers of compassionate cases per country.

Promoting the wellbeing of AYCs during the ME-WE intervention

The planned intervention for AYCs was conducted in six European countries, with some adaptations to the study protocol done in due course in order to cope with the recruitment challenges explained above and the COVID-19 surge since 2020. All adaptations were submitted to and approved by competent ethics committees, where necessary.

Clearly, promoting the wellbeing of participants is of paramount concern when carrying out research in general with minors. Nevertheless, it was especially important regarding the project’s target group of AYCs given the potentially vulnerable nature of their situation as outlined earlier in the Introduction. As a result, a range of safeguards were implemented within the project. Group facilitators engaged in the delivery of the ME-WE intervention were from different professional and/or practice backgrounds (such as psychologists, counsellors, youth workers, social workers, nurses), and they had experience of working with groups and young people. In principle, each facilitator followed the ethical code of conduct of the profession to which they belonged (e.g. psychologist, social workers, nurses). Nevertheless, some common requirements were that facilitators had undergone the ME-WE training programme and that they knew how to react in the event that a participant/s became upset during a group session/s. As well, to be aware, according to national regulations outlined in the Incidental Findings Policy (see above), when they might have been requested to breach the principle of confidentiality to sign-post participants to further support as appropriate. Further, being knowledgeable about ways of actively protecting enrolled AYCs to ensure that no harm was being done and being able to actively pick up on if/when a particular ME-WE group activity could be deemed to be particularly stressful or hurtful for a participant and adapt it accordingly. In this regard, a detailed Intervention Manual that was co-produced by the project partners included practical suggestions for facilitators on how best to deliver the sessions to prevent distressing situations for AYCs (Boccaletti et al. Citation2019).

The presence of two facilitators was deemed to be particularly important in the event that participants expressed, verbally and/or non-verbally, that they were in distress. In Italy the facilitators took turns to lead a session or an exercise, while the other had an observer role to notice signs of distress in AYCs and was available to deal individually with the distressed participant in a confidential space while the rest of the group could continue the activity with the other facilitator. In Sweden, two facilitators assisted each other to provide additional support to a participant AYC who was in a particularly distressing caring situation. In this case, support was provided in between and after the ME-WE sessions and mainly consisted of listening to the AYC. In agreement with the AYC, one of the facilitators was also in contact with the AYC’s contact person at social services. Similarly, in the Netherlands, facilitators commented in a focus group session that having good contact with AYCs between the sessions was valued. Whilst the sessions were ‘face to face’ the Dutch facilitators also welcomed participants by offering lunch which they found helped participants in the beginning to get to know each other ‘We made it a sort of party through sandwiches, hot snacks, drinks and so on’ … … .

In addition, in order to offer supplemental supervisory support as needed, besides ensuring intervention fidelity, in several countries, facilitators were offered monthly supervision from expert peers (i.e. from a mental health professional trained in the theoretical and clinical model at the core of the ME-WE intervention or from a similar background but with longer experience in applying the psychoeducational model on which the ME-WE intervention was based in their work with youth/AYCs).

Ethics of a waitlist control group

The original RCT study protocol was based on a parallel-group design with random allocation of enrolled AYCs to either the ME-WE intervention or a waitlist control (Casu et al. Citation2021). After a 3 months follow-up assessment, the waitlist control group was offered to participate in the same programme as the intervention group. The ethical advantages of a waitlist design are that it guarantees the provision of the intervention to participants who are seeking help, whilst allowing for a non-intervention evaluation in which the effects of time and expectancy of improvement are controlled for (Hart, Fann, and Novack Citation2008). In the case of the project’s specific target group, this was deemed by the consortium to be particularly pertinent, given that in many of the partner countries, there were very few if any available support services for AYCs. It must nonetheless be acknowledged that waitlist control designs can result in delayed interventions, thus their use has been discouraged for studies with long-term follow-ups (Hart, Fann, and Novack Citation2008). For this reason, and to comply with the timeframe of the EU funded ME-WE project period, the clinical trial study was a relatively brief trial, with a short-term, 3-months follow-up. Noteworthy, no-intervention control groups are considered ethically acceptable when the experimental intervention addresses problems that are non-severe or for which there is no effective treatment indicated and available (Mohr et al. Citation2009). Therefore, such a design was considered feasible to test the ME-WE primary prevention psychoeducational model aimed to prevent maladjustment and promote wellbeing and healthy development among AYCs. A total of 107 AYCs who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate were randomized/allocated to the waitlist control group (18 in Italy, 8 in the Netherlands, 49 in Slovenia, 1 in Switzerland, 23 in the United Kingdom and 8 in Sweden). Relatively few of the AYCs belonging to the waitlist control group commenced the ME-WE intervention after the 3-months follow-up, mainly due to lack of interest or competing demands on their time. Nevertheless, a number of AYCs in several countries declined to take part in the intervention but agreed to complete the evaluation questionnaires.

Potential burden related to completion of the evaluation questionnaires

The baseline assessment (evaluation) questionnaire and evaluation questionnaire delivered immediately following completion of the ME-WE groups and subsequently three months later consisted of a number of validated instruments designed to target the primary and secondary outcomes, control variables and process evaluation outcomes of the ME-WE intervention (for a detailed description of study evaluation methodology and tools, see Hanson et al. Citation2022). The assessment questionnaires underwent a small pilot study with several AYCs in Italy and the UK to evaluate the comprehensibility, acceptability and completion time (see Casu et al. Citation2021). The mean questionnaire completion time was 20 min. In several countries, assistance was provided by youth workers, university students or psychologists and other stakeholders linked to the study to AYCs who experienced difficulties in completing the questionnaire for various reasons, including learning and/or reading difficulties, such as dyslexia. A question was added to the AYC process evaluation section asking them for their overall views of the survey. Both positive and negative aspects were raised by many participants. The questions were described as helping further reflection on their situation, and giving a feeling of being understood, or being helped. Negative aspects included the questions triggering fears about the future and/or challenging thoughts about their parent’s illness. Further, AYCs from nearly all countries commented on the survey as being excessively lengthy and sometimes rather boring, with several questions appearing to be repetitive or having double negative answers leading to ambiguity. It is important to note that as the specific EU Horizon 2020 research and innovation funding call was classed as a clinical trial study, the use of questionnaires as a core method for data collection for the clinical trial study within the ME-WE project was viewed as standard practice by the research team. In this way, there was not any built-in flexibility, within the remit of the call, for AYCs themselves to influence the choice of research design or main research method employed for the clinical trial study itself.

Ethical issues relating to the clinical trial study due to the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on the implementation of the ME-WE intervention as in several countries the ME-WE groups had recently commenced, whilst in others ‘face to face’ groups were well underway and were unable to continue in the research settings (for example, carers centres, schools, non-governmental organisation sponsored youth peer support group meetings, and youth after-school programmes) due to the lockdown measures operating in the countries concerned.

Whilst the situation itself could be classed as a ‘force majeure’ as defined in the project’s Grant Agreement, and as a result reasonable grounds could be made for halting the clinical trial study, the project consortium concluded that for a variety of ethical and pragmatic reasons it was important to continue with the clinical trial study. This decision was unanimously supported by all members of the IAEB who expressed that it was important on ethical grounds for participant AYCs to continue to receive the support intervention, especially given that many if not all existing support services for young carers/carers were unavailable during the pandemic.

As a result, the consortium worked together to develop a fully online intervention. Specifically, this entailed that the fully face-to-face delivery (planned for Italy, Slovenia and United Kingdom) was replaced by online sessions using videoconferencing instruments allowing for visual presentations of participants and session materials (e.g. Microsoft Teams and ZOOM). On the other hand, the blended delivery approach (planned for Sweden, Switzerland and the Netherlands) was replaced solely by online meetings using the ME-WE mobile app and supported with the ZOOM video-conferencing system for all intervention sessions. In both delivery approaches, no changes were introduced in the intervention contents. Some activities and exercises were slightly adapted to fit the online delivery model. Training and supervision of facilitators were delivered fully online using videoconferencing platforms.

In terms of protection, security and anonymity issues, there were both positive and negative aspects in relation to the use of an online approach. On the one hand, it meant that much larger numbers of AYCs could potentially take part because the groups were not restricted to a particular research setting. This was seen as an advantage for example in Sweden in rural areas and with large geographical distances which often lead to difficulties with equal access to services. On the other hand, it most likely closed doors for the potentially most disadvantaged groups of AYCs who did not have access to a computer, smart phone or internet. In some instances, in the UK the virtual approach unintentionally revealed existing inequities in technological access amongst both AYCs in carers support centres and their staff. For example, some facilitators in the UK required their carers support centre to supply them with laptops and high-speed internet hotspots, as well as the AYCs.

In addition, taking part online was not always optimal for those AYCs who did not have a private room to use to connect to the ME-WE group sessions, or if they did, they were fearful that other family members could hear them which potentially limited their participation. However, in such situations, passive or silent participation was enabled which meant that AYCs could still participate via the written chat function. Nevertheless, online participation also led to the risk of potentially breaching the privacy/revealing identities of others in the home. In addition, the online approach made it more challenging for the facilitators to control for that screenshots, photos or recordings were not taken during/of the online sessions. As a result, in all the countries online safety was discussed with participant AYCs during the first ME-WE intervention session. Both AYCs and facilitators, thereafter, agreed to follow specific ground rules for everyone to feel safe.

Overall, the evaluation data highlighted that particularly in countries where the ME-WE clinical trial study provided support in the absence of other supportive programmes for AYCs, continuation of the group sessions online were acknowledged as being highly supportive by participant AYCs and stakeholders.

Support post intervention

After completing the ME-WE intervention, group facilitators and other ME-WE stakeholders (school staff, health and social care professionals, youth workers, carer support workers) evaluated the process and content of the intervention. Facilitators reported both positive and negative aspects of the intervention. One of the negative aspects expressed was the perceived lack of follow-up and continuation plan for supporting AYCs after the end of the study (Hlebec et al. Citation2021). Several AYCs perceived the intervention as being too short in duration and would have liked the sessions to have continued. This was perceived to be especially relevant in countries where there is a dearth of existing targeted support services for AYCs or young carers.

To this end, all partner countries in several of their Blended Learning Network sessions (see above), co-created a ‘Country Sustainability Plan’ to facilitate the implementation of the project results, including the ME-WE support intervention, incorporating the mobile app, in practice and policy as appropriate, following the completion of the project (Centola et al. Citation2021). From the minutes of the approximately four monthly post- ME-WE project ‘check in’ online meetings with consortium partners, it can be noted that several concrete initiatives are currently ongoing post- project. For example, in Sweden additional funding was secured from the National Board of Health and Welfare Sweden (NBHWS) so that the Swedish Family Care Competence Centre (Nka) can offer the ME-WE facilitator education to those interested municipalities, regions and organisations from across the country who are interested to implement the ME-WE intervention with young carers. 12 municipalities and 6 NGOs have completed the education and are implementing/planning to implement the ME-WE intervention. In addition, the Centre facilitates regular online network meetings to enable the sharing of experiences and peer learning among ME-WE model users from across the country. Several AYCs who completed the ME-WE intervention now form part of a Young Carer User Board that acts as an advisory board to the NBHWS and Nka in its work in the area of young carers. In Slovenia, the ME-WE intervention is supported by the NGO Soncek- the Slovenian Cerebral Palsy Association who deliver it annually in a camp format to young carers. In the Netherlands, a ME-WE partner, Vilans offers interested parties the opportunity to participate in ME-WE ‘train the trainer’ sessions. Two care support centres have completed the sessions and they began facilitating the ME-WE group sessions for young carers during the summer 2022.

Discussion

Having presented the ethical governance framework that was implemented in the project, followed by a range of ethical issues and considerations that arose in the field study work in the six partner countries, we now turn to discuss the level of success or otherwise of our project consortium to address these main matters, with reference to ethical principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice where appropriate.

Role and utility of the ethical governance framework

We begin with weighing up the role and utility of the detailed project ethical governance framework itself. On the one hand, it could be argued to weigh the project team down in that it was time consuming, and it required enough qualified and experienced members of the project consortium to work on the framework in all the six countries. This was partly due to the consortium often going beyond the formal requirements of national ethics committees, as in the case of the incidental findings policy. In Sweden, the national incidental findings policy was not fully ready in written form prior to the start of the intervention, although it had been discussed and agreed on within the team. As the framework mirrored the current EU research programme guidelines and requirements, it was also rather bureaucratic and lacking in flexibility. For example, with regards to unforeseen circumstances, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. This was addressed by the consortium co-producing iterative versions of the Ethics, Gender and Project Management Framework which enabled partners, with inputs from the IAEB, to be responsive to changing circumstances and further develop and adapt the framework accordingly. Indeed, three versions of the framework were co-produced during the project.

Overall, the ethical governance framework provided the project consortium with a clearly delineated structure on which to base their work. To be able to write and complete the documentation, it required the project consortium to have time to carefully deliberate on and reach agreement on the main procedures and issues that could arise in the field. This was highly relevant in the context of our pan-European project as the core project consortium consisted of approximately 30 people from a variety of backgrounds, beyond academia, and several team members in the partner countries were either new to their post or in a junior role. In this way, the framework stimulated learning among and between the country teams and led to shared understandings on the main ethical considerations within the project. Further, as it was a pan-European project it was not appropriate to assume that one WP leader’s way of doing things in one country was necessarily legally or practically feasible in another country. Thus, ensuring that an overall or over-arching plan also included specific country mitigation measures which reflected specific national relevant legislation and practice guidelines was important, as in the case of the project’s Incidental Findings Policy.

Respecting AYCs in the spirit of co-creation

A major benefit of the extensive ethical consideration process was that it allowed the consortium to hold the safety and well-being of AYCs at utmost priority, understanding that the rapidly changing lives of the AYCs due to the pandemic meant that, wherever appropriate, they needed to be consulted repeatedly to share their views on feasible means of participating in the study without undue burden. This helped to achieve our project aim of co-creation with AYCs, whilst also recognising the potential vulnerabilities exacerbated because of the pandemic. Yet, even with the best laid plans and procedures, there can still be unanticipated events that take place in the field so that the skills and values of the project team and facilitators were important. Several team members and group facilitators had professional backgrounds as healthcare workers, social workers, or mental health counsellors, as well as lived experience as young carers. Nearly all the UK facilitators were young carers in their childhood, similarly to students who assisted with the recruitment of AYCs to the clinical trial study in the Netherlands. Such backgrounds were invaluable in the wider pan-European project team for approaching the circumstances facing the AYCs with understanding, empathy, and compassion. Their professional and lived experiences also allowed them to mitigate unanticipated events and strategize solutions alongside the AYCs, capitalising on co-creation. A prime example of this being the summer camp format for delivery of the ME-WE intervention that was agreed on by the NGO Soncek in collaboration with AYCs and other members of the Slovenian BLN and project team.

Recruitment of AYCs to the clinical trial study was a challenge but in keeping with ethical principles and respect for persons, the project teams had to respect that AYCs led extremely busy lives- juggling their schoolwork and trying to find time to ‘hang out’ with friends whilst carrying out caring activities which meant they had very little time left over to participate in the study. Respecting AYCs’ situation was of paramount concern to the entire consortium so that none of the country teams wished to implicitly coerce AYCs to participate in the study. In Switzerland for example, potential participants sometimes declined or withdrew from participating in the intervention because they deemed it to be too time consuming. As a mitigation measure, the Swiss team were able to offer them other options to meet with less time engagement, in so-called ‘Get-Togethers for young carers’ sessions.Footnote7 In this way, the aim of the study, namely, to support and improve AYCs’ wellbeing and mental health was at least partly met.

As outlined in the ‘Results’ section, an inclusive approach, in keeping with our social justice ethical approach, was adopted with regards to compassionate cases. In this way, the ME-WE intervention was offered to young carers aged 14 and 18 years of age who were otherwise unable to access any other available young carer support services. Thus, we recognise the need for further testing of the intervention with larger numbers of AYCs aged 15–17 years to more fully assess the degree to which the intervention specifically reflects young carers aged 15–17.

Positive and negative impacts of the pandemic

As highlighted in the ‘Results’ section above, the COVID-19 pandemic brought with it both positive and negative aspects that had important ethical considerations for the clinical trial study. In relation to the principle of justice and, more specifically, fair and equitable treatment of AYCs, it raised the issue of the accessibility of the intervention for AYCs. It indeed made for greater geographical access of the intervention for interested AYCs. Conversely, it also served to exacerbate existing technological and financial inequities, thus most likely restricting its use among the most disadvantaged groups of AYCs in some countries. Nevertheless, in keeping with the final recommendations of the IAEB, it showed the flexibility of the teams and the participants to make the best out of a difficult situation – at least there was an option to meet online (Eurocarers /IRCCS-INRCA Citation2021). Further, it showed that several AYCs preferred these opportunities to having no support at all. Therefore, it can be argued that the project consortium was innovative in creating opportunities for AYCs. In Slovenia for example, during the pandemic school lessons were carried out online and in order to ensure equity of access to the sessions, schoolteachers provided tablets/computers and secure Internet access for those pupils who needed them. In this way, potential AYCs who wished to participate in the ME-WE groups online were able to do so. In addition, post project- although unanticipated- the virtual approach to the ME-WE intervention also allows for greater ease in replication across other countries on a large scale, such as the United States of America. Also, more broadly from a justice perspective, being present in the lives of AYCs with the intervention, especially as it had a peer-participatory approach and because the consortium and stakeholders listened to the voices and ideas of AYCs was highly pertinent during the pandemic.

Values and responsibilities of the project consortium

The participatory, co-creation approach (see ‘Methods’ section) and empowerment of AYCs – as evidenced in the country BLNs, IAEB – does nevertheless raise ethical questions regarding the responsibilities of researchers about how to best guide and acknowledge the influence of action/participative research on the lives of youth participants themselves. For example, developing new skills, making changes in their lives, being advocates of young carers – such as participating in national information campaigns, giving presentations in schools and creating the themes for, presenting and moderating at the 3rd International Young Carers Conference (May 2021). AYCs were given certificates for their participation which could then be used for their CVs. The coordinator and country leaders also wrote recommendation letters that AYCs/young adult carers used in their applications for job applications and/or university studies. In the UK, a BLN workshop session was dedicated to the testimony of the project itself and AYCs’ engagement in it. AYCs themselves suggested and designed a pin enamel badge with the ME-WE logo and colours on it that was then given to all the AYCs who had participated in the project.

It is important to note that the consortium itself had worked together on the project proposal for at least one year prior to the submission of the first stage proposal. All partners were Eurocarers members (see Methods above), thus they shared similar values with regards to the wellbeing of AYCs and a common goal to improve their situation. This shared philosophy, coined the ‘ME-WE spirit’ in the project, helped to create and sustain a vibrant teamwork approach in which the ‘WE’ feeling – for the good of the whole – prevailed. This is evidenced by the consortium’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, as explained above.

Conclusions

We now conclude with the major lessons learned from the ME-WE project in relation to ethically responsible research with and for AYCs and in the context of a pan-European project that may be applicable to other vulnerable research groups, cross-national research and include messages for research policy makers and fund holders.

On reflection the ethical governance framework was deemed to be more of a help than a hindrance for project members and stakeholders involved. In addition, as with all research involving humans, and especially field research with vulnerable minors, the skills and mindsets of the researchers and related stakeholders remained of the utmost importance in ensuring the wellbeing of participant AYCs and in driving the work forward. Further, the differing yet complementary skills and experiences of the consortium members led to creative problem solving as issues arose in the field. Here the role of the BLNs was valuable, and we recommend such heterogeneous learning networks for researchers engaging in pan-European research with a variety of partners and with vulnerable target groups. The inclusion of partners from outside academia was made possible by full funding and with no requirements for co-financing- this was deemed a major benefit of the EU Horizon 2020 research funding stream. In this way, it made it feasible for civil society organisations to be on board as equal partners within the entire research and innovation process of the ME-WE project, in keeping with core principles of user involvement and ethical principle of respect for persons. The involvement of NGOs and carers’ organisations active at local level in several countries, made it possible to cover the (possible) gap between academia and civil society so that theoretical and methodological rigour was complemented by practical experience, creating cooperation with the targeted AYCs. In terms of the effectiveness of the participatory, co-creation approach with young carers, on the one hand we recognise the potential constraints imposed by the EU’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, specifically in terms of the overall required project structure and core project elements, including for example, the specific call stipulation for a clinical trial study for the evaluation of the primary prevention intervention. In practical terms, this restricted the opportunities for discussion and agreement with young carers themselves on the actual intervention study design itself for example. Nevertheless, as outlined above, the project consortium included national and European-level carers organisations as full partners who represented and advocated on behalf of young carers already at the outset, thereby ensuring the voices of young carers as a collective were heard at the initial ideas phase of the project proposal and onwards. Also, within the EU H2020 framework and the specific call requirements, emphasis was clearly placed on the importance of the involvement of end users throughout the research process. This helped to confirm the significance and relevance of the project consortium’s participatory co-creation approach. We consider that the composition of the project consortium itself (as outlined above), combined with the role of the project’s IAEB (with equal numbers of adult young carers experts compared to professional, research and policy experts) together with the BLN’s (with young carers as members alongside other stakeholders) represent three concrete ways of working towards genuine involvement of young carers in the project and, in so doing, together with the Framework itself, acted as useful methods for guiding good ethical practice in the project and in future projects with and for vulnerable groups.

With hindsight, the inclusion of different forms of remuneration to enable and facilitate AYCs’ participation, for example in the BLNs and clinical trial study should have ideally been clearly stipulated and budgeted for already at the project proposal stage and subsequent grant agreement. Financial remuneration of vulnerable minors is recognised as a contested issue (Bagley, Reynolds, and Nelson Citation2007; Hartman Citation2006; Schelbe et al. Citation2015)- it can be argued to be respectful and a way to recognise and value young people’s participation. Conversely, it can lead to possible exploitation and coercion if the remuneration is deemed excessive. Similarly, it can be seen as tokenistic to principles of user involvement if the remuneration is deemed to be too low. The project consortium strived to overcome these challenges via the strategies outlined above. Also, at the outset of the project, at the first consortium meeting, possible alternatives to monetary remunerations were discussed, such as internet data supplements, cinema tickets and other cultural tokens. Nevertheless, we consider more could have been done in this area.

Further attention is needed to the issue of possible burden in competing the evaluation questionnaires by participant AYCs, not only in terms of their length but also their readability and general accessibility so that they are more ‘young people friendly’. Despite the questionnaires having been piloted with several AYCs in two countries, and achieving clearance by ethics committees, additional work in the form of further consultation work with AYCs for example, reflective of the project’s philosophy of participatory, co-creation, would most likely have proved to be beneficial. A practical limitation however was the tight project timeframe as well as extra questions required because of the pandemic. We also recognise the importance of having suitable help readily available for assisting youth participants, especially students with learning and/or reading difficulties, who may require extra help with completing the questionnaire.

As outlined above, the ME-WE project was granted funding within a specific call of the EU H2020 funding programme that specified a clinical trial study. Issues of scientific rigour need to be weighed against the feasibility of such a stringent design when conducting research in the field with vulnerable minors. We consider that a mixed-methods approach would have been more conducive to attracting larger numbers of AYCs to participate in the study. At the same time, we recognise that there is a need for RCTs within social research to test the efficacy of a psychosocial intervention. If this is not carried out then it is not feasible to determine whether a support intervention has an effect or not, or worse still it could make things worse (Solomon and Cavanaugh Citation2015). In this way, we argue that researchers do need RCTs together with a range of other research and evaluation tools in social research (Barbabella et al. Citation2023).

More broadly speaking, in the ever-changing landscape of the ongoing pandemic era, we have come to understand that young carers are a group of young people that tend to be adversely affected by widespread disease, environmental disasters, and economic recessions – an unfortunate result of their already vulnerable position in society. The overwhelmingly positive response from AYCs with regards to the benefits of the ME-WE intervention indicate that timely and well-placed interventions, such as ME-WE, can help serve a critical role in mitigating societal challenges facing young carers. However, the ME-WE project demonstrated that the precarity caused from failed austerity programmes in several European countries – in our case, the UK, Slovenia and Italy in particular – has been experienced by the AYCs served in social care support programmes and also by their support staff (Vizard, Obolenskaya, and Burchardt Citation2019). For example, the disparities revealed amongst both UK charity sector staff and AYCs in implementing virtual programmes must prompt recognition and warrant solutions in addressing technological access.

Achievements obtained in dissemination, advocacy and lobby work at national and European level helped raising the attention and increasing the rights of AYCs. As seen for example, in Eurocarers’ contributions to EU policy and Nka’s contribution to the Swedish national action plan for the EU Child Guarantee (summarised in ). We argue that engaging in ethically responsible research should also incorporate actions to raise rights of more disadvantaged people and produce real impact on society.

The challenges of reaching AYCs were wholly acknowledged by the ME-WE project and recognises that research with even younger groups of young carers (<15 years) and those children who often have no awareness about their role remains difficult. Frontline workers across sectors are often ideally placed to identify and interact with AYCs. Thus, a better partnership of researchers, practitioners (social workers, healthcare workers, school staff) and NGOs should be envisioned, reflective of the ME-WE project consortium. The ethical considerations for working with a potentially vulnerable population of youth, such as AYCs, requires thoughtful care and attention at all stages of engagement. By adhering to the lessons of participatory methods with young carers, as demonstrated by the ME-WE project, the protection of their rights can remain prioritised.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the young carers involved in the study, as well as all researchers, professionals and organisations who contributed to the ME-WE project and the present study. In particular, authors thank the partner organisations of the ME-WE project (www.me-we.eu), namely: Linnaeus University (Sweden), coordinator; Eurocarers (Belgium); University of Sussex (United Kingdom); Carers Trust (United Kingdom); Kalaidos University of Applied Sciences (Switzerland); Netherlands Institute for Social Research (Netherlands); Vilans (Netherlands); National Institute of Health and Science on Ageing (IRCCS INRCA) (Italy); Anziani e Non Solo (Italy); University of Ljubljana (Slovenia). The authors would also like to acknowledge the contributions to the ME-WE project of the project’s external International Advisory and Ethics Board members: Elisabeth Lied, expert adult YC, Norway; Anna-Maria Spittel, expert adult YC, Germany; Madeleine Buchner, expert adult YC, director of Little Dreamers (dedicated YCs support service), Australia; Monique Jacques, expert former YC, Brussels; Mieke Schuurman, Senior Policy and Advocacy Coordinator, Children’s Rights and Child Participation, Eurochild, Brussels; Betsy Olson, Professor, geographer, ME-WE project Gender Specialist, University of North Carolina, Department of Geography, USA; Tim Moore, Associate Professor, Deputy Director, Australian Centre for Child Protection, UNISA Justice and Society, University of South Australia, Australia; Joost Bronselaer, Scientific Researcher, Flemish Ministry of Welfare, Public Health and Family, Belgium. Finally, authors acknowledge that the ME-WE model is based on the DNA-V model developed by Louise Hayes and Joseph Ciarrochi (2015) who generously shared their expertise with us.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Elizabeth Hanson

Elizabeth Hanson is a professor at the Linnaeus University (LNU), Dept. Health and Caring Sciences, Sweden and Research Director at the Swedish Family Care Competence Centre (Nka), a national centre of excellence in informal care. She heads up the ‘Informal Carers, Care and Caring’ research group at LNU which acts as Nka’s research arm. Elizabeth is a board member and prior President of Eurocarers, the European association working for informal carers. She established the Eurocarers Research Working Group, comprising of researcher and carer members, whose aim is to feed into the definition of evidence-based policy making on the role and added value of informal carers. She acts as expert advisor on carer issues to the National Board of Health & Welfare Sweden. Elizabeth was principal investigator and coordinator of the EU funded ‘ME-WE’ adolescent young carers project. She has a long- standing interest in carer issues and over the last twenty- five years Elizabeth has led national and EU projects in partnership with informal carers, service users, practitioners, decision makers and civil societies to enhance and/or stimulate innovative service provision. The ultimate goal being to enable those carers who wish to care to thrive and to fulfil their life goals.

Feylyn Lewis