Abstract

Purpose

Based on a 2022 Speech Pathology Australia National Conference keynote address, the author explores the concept of autonomy and how it can be reconceptualised for people with profound intellectual and multiple disability through supported decision-making.

Method

A collection of participatory action research studies with people with profound intellectual and multiple disability and their supporters are presented. Qualitative action research methodologies, including participatory observation, co-design workshops, and interviews, were used to explore supported decision-making for people with profound intellectual and multiple disability.

Result

The insights have been used to co-design (with supporters) a definition and practice framework to enhance the autonomy of people with profound intellectual and multiple disability.

Conclusion

Drawing on the construct of relational autonomy, readers are asked to reflect on their role as speech-language pathologists in enhancing autonomy of those they service, particularly people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. A definition of supported decision-making for people with profound intellectual and multiple disability along with a practice framework are offered. This body of work adds to a growing evidence base in supported decision-making, providing much needed practice guidance specifically relating to people with profound intellectual and multiple disability.

Background

Decision-making is central to our personhood. Most of us are faced with a seemingly ever expanding smorgasbord of daily options: What to wear? Where to live and with whom? What to watch on Netflix? Whether to pray and, if so, to whom? Although dampened by the global pandemic, most of us living in neoliberal societies are blessed with a magnitude of freedom and choice. Decision-making is crucial to the shaping of our identity, providing us with a vehicle with which to demonstrate and realise our hopes and dreams and, therefore, our personhood. The link between autonomy and personhood has been acknowledged since antiquity. It is enshrined in international law, including the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD; United Nations, Citation2006), as a universal human right and within this context is seen as fundamental to our legal personhood. Despite this legislative backdrop, people with profound intellectual and multiple disability (PIMD) are routinely denied their right to autonomy and therefore legal personhood. This is due to a perception that they lack the capacity to participate in decisions about their own lives.

People with profound intellectual and multiple disability

This article focuses on a group of people who are rarely heard, people who may be described as having a profound intellectual and multiple disability. People with PIMD can be described as having complex communication access needs (Dee-Price et al., Citation2021). They may communicate informally and unintentionally, using a range of communication systems such as facial expression, body language, eye contact, non-speech vocalisations, and sometimes behaviours that challenge others. The author aims to sharpen readers’ collective focus on this largely unheard group.

Throughout the article, the word profound is unapologetically used to describe this group of people. The Oxford English Dictionary describes the word profound as “containing great depths of meaning and import; (of meaning or significance) deep, important” (Oxford English Dictionary, Citation2022). PAMIS (Promoting a more inclusive society), a support organisation for people with PIMD in Scotland, provides an apt definition of PIMD.

People with PMLD [PIMD] are a group of individuals with learning disabilities in the profound range and have [several] complex healthcare needs. Their disabilities can present challenges for them and those providing care. However, ‘profound’ also means deep, intense, wise, and requiring great insight or knowledge. Although many people with PMLD have significant disabilities, they are also teachers, facilitators and can make a great contribution to our lives (PAMIS, Citation2022).

Forster (Citation2010), arguing the need for a consistent taxonomy for people with profound intellectual and multiple disability, wrote: “people with PIMD deserve the dignity of being named, counted and recognised for who they are, what they need, and how they might be a unique part of our community” (Forster, Citation2010, p.33).

The right to autonomy: A universal construct?

We live in a time and place where freedom and autonomy are valued above all else. Most humans, at least in the west, lead lives that bring with them an expanding smorgasbord of options: How to spend money? What clothes to wear? Where to live? Who to spend time with? Who to share a bed with? Who to vote for? Although perhaps dampened by the global pandemic, it would be fair to say that most of us living in neoliberal societies are enamoured with freedom, autonomy, and choice.

The 1970s saw these notions of autonomy, self-determination, freedom, and choice increasingly reflected in the lives of people with disability (Gibbs, Citation1998; Nerney, Citationn.d.; Scala & Nerney, Citation2000). This movement championed a philosophical shift within which these notions of freedom and autonomy became more explicit to the disability community. However, despite gains for those with physical and milder intellectual or cognitive disability, most people with more severe or profound cognitive disability were not, and still have not, been invited to the self-determination party (Watson, Citation2016b).

What is autonomy? A deconstruction of the word reveals its meaning explicitly. Auto, meaning self, and nomy, meaning governance. It is about human preferences directing one’s own life’s path. It has been discussed since antiquity. Philosophers like Aristotle, Socrates, and Plato saw autonomy as the very essence of a rational human and defining characteristic of personhood (Gracia, Citation2012). Autonomy shapes a person’s identity, providing a vehicle with which to demonstrate and realise hopes and dreams. It is enshrined in international law as a universal human right. Notions of freedom, autonomy, and self-determination underscore the main tenets of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR; United Nations, Citation1948), a declaration Eleanor Roosevelt (Citation1948) as humanity's Manga Carta. Perhaps the strongest catalyst for the UDHR was the massive and systematic human rights abuses committed during World War II by the Nazis including against the Jews, the Roma, and a group whose abuses are rarely highlighted in discussions of the holocaust, people with disability, particularly those with intellectual disability (Johannes, Citation2019).

Autonomy is enshrined in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD; United Nations, Citation2006), the first international legal mechanism that specifically focused on the needs of people with disability. It came into force in 2008. Article 12(2) CRPD requires that, “State Parties shall recognize that persons with disabilities enjoy legal capacity on an equal basis with others in all aspects of life” (UNCRPD, Citation2006). Through General Comment No. 1, the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD Committee) distinguishes between “legal capacity” and “mental capacity”. According to the CRPD, the right to legal capacity is universal and means that everyone’s will and preferences must be given effect and respected within the context of the law, on an equal basis with others. Often referred to as the right to legal personhood, the right to legal capacity means that everyone has a right to be seen as a person before the law. Where someone is denied legal capacity, they are no longer a legal person. Importantly, this means they are not entitled to the same rights and responsibilities as other citizens, including a legal right to live an autonomous life. Often confused with legal capacity, mental capacity refers to a person’s decision-making ability, which may vary within and between individuals. The committee emphasises that difficulties with decision-making (mental capacity) should not be used to justify the denial of legal capacity or legal personhood (Arstein-Kerslake & Flynn, Citation2016).

Should cognition be the human trait that defines personhood?

Despite the well established universal human right to autonomy, we continue to stumble across an embarrassing feature of modern ethics. This feature privileges cognition as the human trait that defines a person’s ability to realise their autonomy and, therefore, their personhood. This feature is increasingly coined “cognitive ableism”, a concept based on the perception that personhood is dependent on cognitive capacity, and therefore, where someone lacks cognition, their personhood is questionable (Carlson, Citation2001; Sandberg et al., Citation2021). A review of guardianship decisions within Victoria, Australlia revealed that the key factor relating to whether someone is perceived to have decision-making capacity (and therefore, an ability to exercise their autonomy and be granted legal personhood) is overwhelmingly cognition (Watson et al., Citation2022). In Practical Ethics (Citation1979), Singer promotes the idea that the value of a life should be based on the cognitive traits of rationality, autonomy, sense of justice, and self-consciousness. He wrote, “Defective infants lack these characteristics. Killing them, therefore, cannot be equated with killing normal human beings, or any other self-conscious beings” (Singer, Citation1979, p.131). In his most recent edition of Practical Ethics (Citation2011), Singer has arguably softened his position, claiming he has listened to his critiques and writing, “many beings are sentient and capable of experiencing pleasure and pain, but they are not rational and self-conscious and, therefore, are not persons” (Singer, Citation2011, p.85). Further on Singer writes, “the fact that a being is a human being, in the sense of a member of the species Homo sapiens, is not relevant to the wrongness of killing it; instead, characteristics like rationality, autonomy and self-awareness make a difference” (Singer, Citation2011, p.160). Singer continues, “killing a disabled infant is not morally equivalent to killing a person. Very often it is not wrong at all” (Singer, Citation2011, p.167). Despite his slight change of tone in more recent years, Singer’s ideas continue to ache in the disability world, like a wound that won’t heal. At the core of Singer’s arguments both historically and now beats a single assertion: that people with the most profound intellectual disability do not have moral personhood and, therefore, are not equal to other members of society.

Such arguments have resurfaced within the context of the COVID pandemic. We have witnessed both individuals and institutions shrug as COVID more heavily affects people with disability. The reporting of the deaths of people with high and complex needs as linked with their underlying conditions diminishes their passing in many ways. It is fine if a disabled person dies of this disease, they suggest. Somehow, their lives are worth less. Quite how, or why, or when, cognitive ability became the alleged touchstone of what it means to be a person is debateable. It was not always so.

Quinn and colleagues suggest that this privileging of intellect or cognition put forward by ethicists like Peter Singer is a social construct that began following the Enlightenment (Quinn et al., Citation2018). A hierarchy of humankind developed, which linked cognition to one’s personhood, leading to the birth of cognitive ableism, resulting in the valuing of certain people over others based purely on their cognitive capacity and their perceived ability to interact consciously with their environment (Quinn et al., Citation2018).

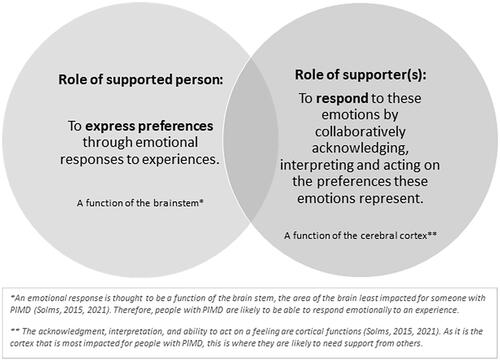

A deep dive into emerging theories of neuroscience and the source of consciousness has led to a comparison of the respective functioning of the cerebral cortex and the brain stem. The cerebral cortex is historically assumed to be the seat of conscious action and intelligence, while the brain stem is responsible for performing automatic/unconscious functions. Solms, however, argue that consciousness arises not in the cortex, but in the more primitive brain stem, where basic emotions begin. As it is the cortex that is typically damaged for people with profound intellectual and multiple disability, there is a long held hypothesis that people with PIMD lack the ability to engage in conscious action and thought. It is this hypothesis that neuroscientists such as Solms and colleagues are challenging (Solms, Citation2015, Citation2022; Solms & Panksepp, Citation2012; Solms & Turnbull, Citation2018).

Drawing from studies with children with hydranencephaly, in which the cerebral cortex is destroyed in utero, Solms have found that despite an absence of the cortex, these children demonstrate discriminative awareness, evidenced through conscious actions such as: social interaction; spatial orientation; showing musical, taste, sound, and tactile preference; and affective responses to experiences (Solms, Citation2022). The role of the cortex is to make sense of this emotional consciousness by responding to feelings generated in the brain stem, learning from them, and using them to inform decisions as to whether an activity is worth doing again or not. Such studies have led to the growing hypothesis that the seat of consciousness is not in the cortex, but rather a function of the brain stem. In other words, they claim that consciousness is subcortical, not cortical, and therefore, people with cortical damage, such as people with PIMD, possess emotional consciousness and can, therefore, express preference. With support from people who know them well, these expressions of preference can be built into choices and decisions, and by so doing realise their autonomy and, therefore, their personhood (Solms, Citation2015, Citation2022; Solms & Panksepp, Citation2012; Solms & Turnbull, Citation2018).

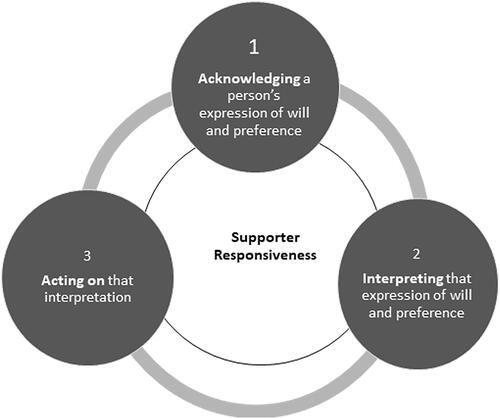

Where does this new way of thinking about the human cortex fit into the notion of a person with PIMD’s ability to realise their autonomy and therefore personhood? If we accept that emotional consciousness is not seated in the cortex, but in the brainstem, people with cortical damage, such as people with PIMD, are likely to possess emotional consciousness and can therefore express preference. Where they are likely to need support is with cortical activities, such as acknowledging, interpreting, and acting on these expressions of preference, and by so doing realising their autonomy and promoting the likelihood they will be seen as a legal person before the law. incorporates this notion of support with cortical functioning into Watson’s model of supported decision-making for people with PIMD (Watson, Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Watson et al., Citation2017).

Figure 1. A supported decision-making framework: A tool for supporting people who communicate informally to live lives they prefer (Watson et al., Citation2017, p. 4).

The denial of legal capacity (legal personhood) through cognitive assessment

Human rights scholars are increasingly raising concerns about state sanctioned removal of personhood through denials of legal capacity based on the results of isolated assessments of an individual’s cognitive or cortical performance (Flynn & Arstein-Kerslake, Citation2014). These tools, routinely used by tribunal guardianship board members in determinations of legal capacity, are structured around the premise that decision-making capability is characterised by a set of individual cognitive/cortical abilities that are prerequisites for decision-making capability. These tools are commonly used to generate various types of specialist psychology reports (usually neuropsychology), which form a central component of the evidence guardianship tribunals consider when deciding whether someone can make a decision and, therefore, should be seen as a person before the law.

These reports have obvious value in communicating to a guardianship tribunal a person’s cognitive capacity and, therefore, their ability to independently make decisions. However, they are not based on an evaluation of a person’s decision-making capacity within the context of how humans generally make decisions, that is, with the support of people in their lives who know them well.

The Victorian Law Reform Commission in their 2012 review of Guardianship in Victoria found that decision-making skills are predominantly assessed independent of environmental factors such as support from family, friends, and support staff (Victorian Law Reform Commission, Citation2012). Due to the arguably narrow nature of these assessments, people with PIMD who come before a guardianship tribunal are regularly assessed as having no or very limited mental or decision-making capability. In most jurisdictions, the legal response to this assessment is to deny legal capacity, and permit a third party (e.g. a legal guardian) to make decisions on behalf of the concerned person, taking away that person’s right to be seen as a person before the law.

An interdependent rather than a cognitive view of human decision-making

There is growing evidence from a range of disciplines that optimal human decision-making is not individual, but relational in nature (Gómez-Vírseda et al., Citation2019; Zielinski et al., Citation2020). This view challenges the belief that personal autonomy can only be realised independently. Bach and Kerzner promote, “a positive liberty view of autonomy [whereby] we do not exercise our self-determination as isolated, individual selves, but rather relationally, interdependently and intersubjectively with others” (Bach & Kerzner, Citation2010, p. 40). The concerns expressed by proponents of universal legal capacity claim that individual cognitive assessments widely used as evidence to deny legal capacity fail to account for the substantial role of environmental support in human decision-making. Beamer and Brookes (Citation2001) articulate this view in their reference to supported decision-making, stating that:

The starting point is not a test of capacity, but the presumption that every human being is communicating all the time and that this communication will include preferences. Preferences can be built up into expressions of choice and these into formal decisions. From this perspective, where someone lands on a continuum of capacity is not half as important as the amount and type of support they get to build preferences into choices (Beamer & Brookes, Citation2001, p. 4).

A relational view of decision-making, autonomy, and personhood

If the perceived bond between personhood and cognition is to be broken, personhood needs to be understood through other human traits such as a capacity for sociability, a capacity for emotional connectedness, and a capacity for human relations. These traits can be characterised under the collective umbrella of relationality, a trait that is in the grasp of all human beings, including those with limited cortical functioning, such as people with PIMD. An early discussion of relational autonomy was put forward by Nedelsky (Citation1989). She described the traditional notion of autonomy as involving self-sufficient independence as unhelpful. Nedelsky suggests that autonomy should be reframed around the idea that autonomy is best realised not as an individualised construct, but within a social context (Nedelsky, Citation1989).

Supported decision-making for people with PIMD

The CRPD (Article 12; United Nations, Citation2006) promotes supported decision-making as a mechanism for enhancing a person’s mental (decision-making) capacity. Supported decision-making requires supporters to move away from an individualised understanding of autonomy, to one that is relational. In the last decade, there has been considerable empirical focus on supported decision-making frameworks throughout the world. A range of models and practice frameworks have been developed. These evidence-based frameworks provide much needed guidance for people with mild to moderate intellectual disability (Bigby et al., Citation2021; Browning et al., Citation2021; Douglas & Bigby, Citation2020; Shogren et al., Citation2017). However, they lack a focus on specific strategies to increase supporters’ responsiveness, particularly to expressions of preference of people with PIMD. Watson’s (Citation2016a) evidence-based definition and framework of supported decision-making, specifically for people with PIMD, goes someway to fill this knowledge and practice gap.

Listening to people rarely heard: Supported decision-making with people with PIMD

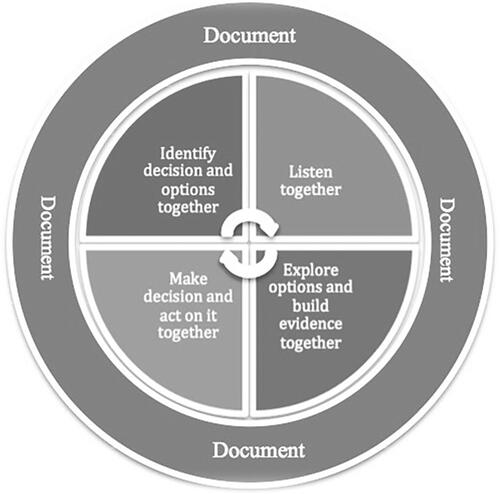

Watson (Citation2016a) implemented a supported decision-making framework and training package with five people with PIMD and their support networks. The first iteration of the intervention’s content and structure was based on a rich pool of research literature and practice knowledge, predominately around complex communication needs, self-determination, and intellectual disability (Brown & Brown, Citation2009; Bunning et al., Citation2013; Goldbart et al., Citation2014; Horton et al., Citation2004). Using a co-design process, both the framework and the training package in which it is embedded was implemented, analysed, and refined over a period of three years (Watson, Citation2016b; Watson & Joseph, Citation2015). Such a cyclic approach is designed to continuously improve the quality and functionality of a design, system, or framework by facilitating evolution and improvement, as successive versions or iterations of a design are implemented. The framework is, “designed to gather a consensus view on what a person with severe or profound intellectual disabilities may be communicating and/or what may be in their best interests and from there make a decision” (Watson, Citation2012, p. 43). The supported decision-making process that emerged from this longitudinal study is depicted in .

Through the implementation of this practice framework, Watson and colleagues have developed a definition and have further characterised what supported decision-making can look like for people with PIMD.

Supported decision-making for people with severe to profound intellectual disability is an interdependent and complex process carried out between supporters and supported. Within this dynamic, both parties contribute differently. The person facing the decision contributes by expressing their will and preference, using a range of informal communication methods such as body language, facial expression, gesture, and physiological reactions (e.g., changed breathing patterns). Supporters contribute to the process by responding to these expressions of will and preference, through acknowledging (as opposed to ignoring), interpreting and acting on this expression (Watson, Citation2016b, p. 4).

This definition is further represented in .

Figure 2. Characterisation of supported decision-making for people who communicate informally in relation to two distinct but interrelated roles. Figure adapted from Watson et al. (Citation2017, p. 6).

Supporter responsiveness: The focus of supported decision-making intervention

The key for practice to Watson’s framework is that supporter/communication partner(s) responsiveness is the task that is most amenable to change and, therefore, should be the focus of intervention. This task of responsiveness includes acknowledging, interpreting, and acting on the expression of will and preference of those they support (). Watson, Wilson, and Hagiliassis (2017) found that effective responsiveness to the expression of preference of people with PIMD involves supporters firstly acknowledging or noticing, as opposed to ignoring, expressions of preference. Secondly, effective responders collaboratively interpreted these expressions of preference, assigning meaning to them, and thirdly they acted on this meaning.

Factors underlying supporter responsiveness

Watson (2016) found a range of factors underlying supporter responsiveness. Although a thorough discussion of these factors is beyond the scope of this paper, they have been explored elsewhere (Arstein-Kerslake et al., Citation2017, Citation2021; Watson et al., Citation2019).

Conclusion

Article 12 ; United Nations, Citation2006 is seen as the catalyst for change in achieving the human right to autonomy (legal personhood) for everyone, regardless of their level of cognition. Speech-language pathologists have a crucial role to play in supporting people with cognitive disability to realise their autonomy through supported decision-making. This is because a central component of supported decision-making is communication (Watson, Citation2019). Article 12 promotes practice that recognises the different ways in which people make decisions, communicate, and their different levels of cognitive ability, and its proponents maintain that these characteristics should not be used to assess or deny legal capacity/legal personhood. Despite this legislative backdrop, people with PIMD are routinely denied their right to autonomy, and therefore legal personhood.

This article has explored how the concepts of autonomy and decision-making capacity can be reconceptualised for people with PIMD by drawing on emerging developments in neuroscience, consciousness, and relational autonomy. The cerebral cortex has historically assumed to be the seat of conscious action, while the brain stem has been seen to be responsible for performing automatic/unconscious functions. As it is the cortex that is typically damaged for people with PIMD, based on these assumptions there is a long-held hypothesis that these people lack the ability to engage in conscious action, thought, and expressions of feelings and preferences. However, emerging developments in neuroscience that provide evidence that emotional consciousness and therefore a person’s emotional reactions to an experience are in the brainstem rather than the cerebral cortex refute this hypothesis, suggesting that people with PIMD can emotionally respond to experiences and therefore express preference. Where a person with PIMD needs support is in the cortical functions of making sense of these feelings and expressions of preference, by acknowledging them, interpreting, and then acting upon them. This is where the crucial role of the decision-making supporter comes to the fore.

Speech-language pathologists are asked to reflect on their role of enhancing autonomy, and therefore personhood, of those they service especially people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. A framework for guiding practice in supported decision-making, specifically for people with PIMD and their circles of support, has been presented. This evidence-based framework provides much needed guidance for speech-language pathologists and other practitioners to facilitate best practice in supported decision-making for people with PIMD. The author has not explored specific practice strategies and mechanisms drawn from this framework. Readers are guided to a body of previous and forthcoming practice-based research, which will provide further evidence-based guidance to enhance their practice in supported decision-making for people with PIMD (Voss et al., Citation2022; Watson, Citation2016b; Watson et al., Citation2017, Citation2019).

Ethical approval

All research reported in this paper was assessed by the Deakin University ethical review body and found to be in full compliance with the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research (2018) and the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007, updated 2018).

Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Arstein-Kerslake, A., & Flynn, E. (2016). The general comment on article 12 of the convention on the rights of persons with disabilities: A roadmap for equality before the law. International Journal of Human Rights, 20(4), 471–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2015.1107052

- Arstein-Kerslake, A., O’Donnell, E., Kayess, R., & Watson, J. (2021). Relational personhood: A conception of legal personhood with insights from disability rights and environmental law. Griffith Law Review, 30(3), 530–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/10383441.2021.2003744

- Arstein-Kerslake, A., Watson, J., Browning, M., Martinis, J., & Blanck, P. (2017). Future directions in supported decision-making. Disability Studies Quarterly, 1, 37.

- Bach, M., & Kerzner, L. (2010). A new paradigm for protecting autonomy and the right to legal capacity. Prepared for the Law Commission of Ontario, October 2010. Retrieved from http://www.lco-cdo.org/en/disabilities-call-for-papers-bach-kerzner

- Beamer, S., & Brookes, M. (2001). Making decisions: Best practice and new ideas for supporting people with high support needs to make decisions. London: Values into Action.

- Bigby, C., Douglas, J., Smith, E., Carney, T., Then, S.-N., & Wiesel, I. (2021). I used to call him a non-decision-maker - I never do that anymore: Parental reflections about training to support decision-making of their adult offspring with intellectual disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 2, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1964623

- Brown, I., & Brown, R. (2009). Choice as an aspect of quality of life for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Policy & Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 6, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2008.00198.x

- Browning, M., Bigby, C., & Douglas, J. (2021). A process of decision-making support: Exploring supported decision-making practice in Canada. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 46(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2020.1789269

- Bunning, K., Smith, C., Kennedy, P., & Greenham, C. (2013). Examination of the communication interface between students with severe to profound and multiple intellectual disability and educational staff during structured teaching sessions. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 57(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01513.x

- Carlson, L. (2001). Cognitive ableism and disability studies: Feminist reflections on the history of mental retardation. Hypatia, 16(4), 124–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2001.tb00756.x

- Dee-Price, B.-J. M., Hallahan, L., Nelson Bryen, D., & Watson, J. M. (2021). Every voice counts: exploring communication accessible research methods. Disability & Society, 6(2), 240–264. doi:10.1080/09687599.2020.1715924

- Douglas, J., & Bigby, C. (2020). Development of an evidence-based practice framework to guide decision making support for people with cognitive impairment due to acquired brain injury or intellectual disability. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(3), 434–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1498546

- Eleanor Roosevelt. (1948). ‘Speech Introducing the UDHR to the General Assembly of the United Nations’. https://www2.gwu.edu/∼erpapers/maps/UDHRspeech.htm

- Flynn, E., & Arstein-Kerslake, A. (2014). Legislating personhood: Realising the right to support in exercising legal capacity. International Journal of Law in Context, 10(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744552313000384

- Forster, S. (2010). Unnamed in silence: People with intellectual and multiple disabilities are becoming an invisible population. Link Disability Magazine, 19, 32–33.

- Gibbs, J. P. (1998). Civil rights. Social Policy, 28(3), 10–13.

- Goldbart, J., Chadwick, D., & Buell, S. (2014). Speech and language therapists’ approaches to communication intervention with children and adults with profound and multiple learning disability. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 49(6), 687–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12098

- Gómez-Vírseda, C., de Maeseneer, Y., & Gastmans, C. (2019). Relational autonomy: What does it mean and how is it used in end-of-life care? A systematic review of argument-based ethics literature. BMC Medical Ethics, 20(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-019-0417-3

- Gracia, D. (2012). The many faces of autonomy. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics, 33(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-012-9208-2

- Horton, S., Byng, S., Bunning, K., & Pring, T. (2004). Teaching and learning speech and language therapy skills: The effectiveness of classroom as clinic in speech and language therapy student education. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 39(3), 365–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/13682820410001662019

- Johannes, M. (2019). The universal declaration of human rights and the holocaust: An endangered connection. Georgetown University Press.

- Nedelsky, J. (1989). Reconceiving autonomy: Sources, thoughts and possibilities. Yale Journal of Law and Feminism, 1, 7–36.

- Nerney, T. (n.d.). Challenging incompetence: The meaning of self-determination. The Center for Self-Determination. http://www.eoutcome.org/Uploads/PATashUploads/PdfUpload/Tom%20Nerney-Challenging%20Incompetence.pdf

- Oxford English Dictionary. (2022). Profound, adj. and n. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/152131?rskey=TsconH&result=1&isAdvanced=false

- PAMIS. (2022). Promoting a more inclusive society. Retrieved from https://pamis.org.uk/

- Quinn, G., Gur, A., & Watson, J. (2018). Ageism, moral agency and autonomy: Getting beyond guardianship in the 21st century. In I. Doron & N. Georgantzi (Eds.), Ageing, ageism & the law: European perspectives on the rights of older persons. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Sandberg, L. J., Rosqvist, H. B., & Grigorovich, A. (2021). Regulating, fostering and preserving: The production of sexual normates through cognitive ableism and cognitive othering. Culture Health & Sexuality, 23(10), 1421–1434. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2020.1787519

- Scala, M. A., & Nerney, T. (2000). People first: The consumers in consumer direction. Generations, 24(3), 55–59.

- Shogren, K. A., Wehmeyer, M. L., Lassmann, H., & Forber-Pratt, A. J. (2017). Supported decision making: A synthesis of the literature across intellectual disability, mental health, and aging. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 52(2), 144–157.

- Singer, P. (1979). Practical ethics. Cambridge University Press.

- Singer, P. (2011). Practical ethics. Cambridge University Press.

- Solms, M. (2015). The feeling brain: Selected papers on neuropsychoanalysis. Routledge.

- Solms, M. (2022). The hidden spring: A journey to the source of consciousness. Profile Books.

- Solms, M., & Panksepp, J. (2012). The “id” knows more than the “ego” admits: Neuropsychoanalytic and primal consciousness perspectives on the interface between affective and cognitive neuroscience. Brain Sciences, 2(2), 147–175. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci2020147

- Solms, M., & Turnbull, O. (2018). The brain and the inner world: An introduction to the neuroscience of subjective experience. Routledge.

- United Nations. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-humanrights

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-withdisabilities.html

- Victorian Law Reform Commission. (2012). Guardianship: Final report 24.

- Voss, H., Watson, J., & Bloomer, M. J. (2022). End-of-life issues and support needs of people with profound intellectual and multiple disability. In R. J. Stancliffe, M. Y. Wiese, P. McCallion, & M. McCarron (Eds.), End of life and people with intellectual and developmental disability: contemporary issues, challenges, experiences and practice (pp. 353–377). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98697-1_13

- Watson, J. (2012). Supported decision making for people with severe or profound intellectual disability: ‘We’re all in this together, aren’t we? 6th Roundtable on Intellectual Disability Policy ‘Services and Families Working Together’, Bundoora, Australia.

- Watson, J. (2016a). Assumptions of decision-making capacity: The role supporter attitudes play in the realisation of article 12 for people with severe or profound intellectual disability. Laws, 5(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws5010006

- Watson, J. (2016b). The right to supported decision-making for people rarely heard. Melbourne: Deakin University.

- Watson, J. (2019). The role of speech-language pathology in supporting legal capacity. Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech Language Pathology, 21(1), 25–28.

- Watson, J., Anderson, J., Wilson, E., & Anderson, K. L. (2022). The impact of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) on Victorian guardianship practice. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(12), 2806–2814. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1836680

- Watson, J., & Joseph, R. (2015). People with severe or profound intellectual disabilities leading lives they prefer through supported decision-making: Listening to those rarely heard. A guide for supporters. A training package. Melbourne, Australia, Scope Australia.

- Watson, J., Voss, H., & Bloomer, M. J. (2019). Placing the Preferences of People with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities at the Center of End-of-Life Decision Making through Storytelling. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 44(4), 267–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540796919879701

- Watson, J., Wilson, E., & Hagiliassis, N. (2017). Supporting end of life decision making: Case studies of relational closeness in supported decision making for people with severe or profound intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities: JARID, 30(6), 1022–1034. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12393

- Zielinski, R. E., Roosevelt, L., Nelson, K., Vargas, B., & Thomas, J. W. (2020). Relational decision-making in the context of life-limiting fetal anomalies: Two cases of anencephaly diagnosis. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 65(6), 813–817. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.13161