Abstract

Purpose

To investigate Australian speech-language pathologists’ (SLPs’) knowledge of language and literacy constructs, skills in linguistic manipulation, and self-rated ability and confidence.

Method

Two hundred and thirty-one SLPs from across Australia completed an online knowledge and skill assessment survey.

Result

There was substantial individual variability regarding performance on items measuring the knowledge and skills of essential literacy constructs. SLPs were most likely to rate their confidence in providing intervention for phonological and phonemic awareness as "very good" or "expert". They reported lower confidence providing intervention for all other aspects of literacy. The majority of SLPs reported what they described as inadequate preservice training to practise in literacy. There was variability between respondents in their self-reported alignment with approaches and beliefs that are unsupported by current research evidence on reading instruction and support.

Conclusion

The level and consistency of SLPs’ literacy knowledge and skills requires improvement. The perception of inadequate preparation to practise in literacy may mean that SLPs are reluctant to engage in this area of practice. Minimum accreditation requirements specifically for literacy are recommended, together with assurance of ongoing professional learning opportunities spanning all components of literacy.

SLPs in literacy

The role of the child and adolescent speech-language pathologist (SLP) has expanded beyond oral language to include the provision of services targeting literacy, (reading, writing, and spelling), particularly since the turn of the century (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association [ASHA], Citation2016; New Zealand Speech Language Therapists’ Association, Citation2012; Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2021; Speech-Language & Audiology Canada, Citation2016). According to Australia’s national professional body, speech-language pathology practice in literacy includes: (a) providing assessment and intervention for literacy difficulties; (b) advocacy for clients and/or evidence-based curriculum and resources; and (c) collaborative practices such as consultation, education, and research (Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2021).

In order to provide robust intervention for students with literacy difficulties, the knowledge of the SLP is a pivotal factor. As outlined by Moats (Citation2020), critical features of effective instruction and support include intensive, explicit, systematic, and sequential introduction of linguistic concepts; suitable instructional examples and modelling; and response, feedback, and correction of student mistakes in ways that promote learning. Practitioners with higher levels of expertise in phonological awareness and the alphabetic principle demonstrate increased explicit instructional time around these skills (McCutchen, Abbott et al., Citation2002; McCutchen, Harry et al., Citation2002). It is plausible to infer that the higher the level of knowledge and proficiency for any linguistic subskill, the more explicitly and effectively one will provide remediation for identified difficulties. The pre-service training in language development and linguistics that SLPs undertake includes phonology, semantics, syntax, and morphology (Fallon & Katz, Citation2020) with content addressing both typical and atypical language development (Lanter & Waldron, Citation2011). Given such training, SLPs should be well equipped with the necessary skills and knowledge to also learn how to address literacy difficulties (Fallon & Katz, Citation2020).

It follows from the above that SLPs should have knowledge and skills deemed expert/specialist level with respect to assessing, diagnosing, and designing interventions for students with literacy difficulties. However, current evidence is limited on whether, despite their language and linguistics training, SLPs do have the requisite specialist literacy knowledge and skills to work effectively with students who struggle in these areas. Much of the data regarding SLPs’ beliefs, confidence, knowledge, and skill when working in the literacy domain arises from self-report studies. A limitation of studies reliant only on self-report and/or self-evaluation is the risk of bias and lack of opportunity to compare results to objective measurement.

Studies exploring the subjective knowledge, confidence, and perceptions of SLPs in literacy

The ASHA School Survey Report has repeatedly found that approximately only one-third of school-based SLPs report providing reading and writing interventions to students on their caseload (e.g. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Citation2020). These findings are supported by other studies dating from 2010 through to 2022. In 2010, a survey of 599 SLPs working in the USA found that more than half of the respondents perceived their preservice training regarding the assessment of and intervention for written language disorders was "limited" (Blood et al., Citation2010). When reflecting on their clinical knowledge about written language, for assessment/treatment (i.e. assessment tools and strategies, and intervention approaches) and spelling (i.e. decoding, orthography, the alphabetic principle, and the language bases of literacy disorders), approximately two-thirds of Blood et al.’s sample described their knowledge as "limited", "very limited" or else they were "unsure". When asked to rate their confidence to work clinically in the area of written language disorders, overall, they reported being "somewhat confident".

One year later, when surveying 645 school-based SLPs across 49 states of the USA, Fallon and Katz (Citation2011) reported that almost half of their respondents felt that they did not have sufficient knowledge and expertise to help students with written language difficulties. When asked whether respondents felt they had received adequate training about clinical practice in written language difficulties as students, only 26% indicated that they had. Fallon and Katz were not able to shed light on the adequacy or depth of such training. While the majority of respondents believed they possessed the knowledge necessary for providing intervention to children and adolescents for phonological awareness, phonics, and morphological analysis, they did not feel confident in their ability to address spelling difficulties. One-third of respondents reported providing no written language services to any students on their caseload. Three major factors increasing the likelihood of an SLP’s uptake of literacy intervention were identified: (a) having received training in written language as part of preservice programs; (b) personal belief in their own expertise in literacy intervention; and (c) expressing stronger agreement that written language is within the SLP’s scope of practice.

In a recent Australian study of 219 SLPs (Serry & Levickis, Citation2021), only 10% agreed that preservice training adequately prepared them to work in the literacy domain. Despite this, the majority of respondents agreed that SLPs had a role in working with children having difficulties with reading and related literacy skills. Two-thirds of the sample indicated confidence to work in some but not all areas of literacy. The vast majority (95%) were confident in providing intervention for phonological awareness, while 70% reported confidence in intervening for morphological awareness.

In the same year as the Serry & Levickis Citation2021 study, Heilmann and Bertone (Citation2021) reported on a survey of 145 SLPs in Wisconsin (USA) exploring areas relevant specifically to school-based SLP practice. When provided with open-ended questions about aspects of their training in relation to school-based practice, respondents rarely mentioned training related to possible work in literacy. Respondents were asked to order 13 areas by priority for preservice training and/or professional learning. Reading disorders were ranked as "unimportant" (11th of 13), and written language disorders as "very unimportant" (ranked last). When specifically asked to rank areas of need for SLPs’ professional development related to reading and writing, respondents were more interested in SLP scope of practice in literacy and integrating classroom instruction into therapy than on the technical aspects of reading (listed as "decoding, reading fluency etc") and writing (listed as "spelling, punctuation and handwriting").

Most recently, Loveall et al.'s (Citation2022) survey of 271 US SLPs revealed support for the view that clinical assessment, identification, and prevention of—and intervention for—reading disabilities are within the scope of practice of SLPs. Despite this, just over half of the sample believed that responsibility for preventing, assessing, and identifying and diagnosing students with reading disabilities lay more with teachers. Additionally, almost half considered that teachers bore the primary responsibility for intervention. In terms of their own practices, over half of the respondents reported "never" administering reading assessments and a further 30% only administering reading assessments "a few times a year". Further, 44% of the sample reported providing intervention for reading difficulties "never" or "a few times a year". Preservice clinical training in the area of reading difficulties was considered adequate by just over one-third of respondents only. Despite this, respondents reported general confidence (on a seven-point scale) in their ability to provide assessment and intervention for a variety of individual subskills of reading difficulties. The greatest confidence was expressed in the oral language-based domains—language comprehension and phonological awareness. The lowest confidence was observed for areas involving printed text—print and orthographic knowledge. In what appears to be a contradiction with the reported general confidence for subskills, less than half of the respondents indicated that they knew what assessment to offer if required to assess reading difficulties, and only half agreed they would know what intervention to offer (Loveall et al., Citation2022).

Studies exploring the objective knowledge and skills of SLPs as these relate to literacy

The studies described above relied on self-report and/or self-evaluation with limited reports of objective measures of SLPs’ knowledge, skills, or practices in relation to working with children and adolescents in the literacy domain. Studies objectively measuring SLPs’ knowledge of constructs essential to literacy assessment and intervention are restricted to single domains: phonological/phonemic awareness (e.g. Carroll et al., Citation2012; Spencer et al., Citation2008) and orthographic knowledge (Krimm & Schuele, Citation2022).

Phonological and phonemic awareness

Studies examining the phonological and/or phonemic awareness knowledge and skills of SLPs often compared SLPs to other educators. Spencer et al. (Citation2008) assessed the phonemic awareness skills (segmentation, identification, and isolation) of SLPs, and found that whilst they had expertise beyond that of other educators they examined, SLPs did not reach the ceiling on the tasks administered. They described the group performance as lacking proficiency and failing to demonstrate expert level skills in phonemic awareness. Administering the same tasks, Spencer et al. (Citation2011) found that SLP students who had completed coursework in phonetics outperformed peers who had not by a notable margin and scored only slightly lower than the qualified SLPs in Spencer et al.’s earlier (Citation2008) study. Using a verbal assessment of phonological awareness, the 34 SLPs in Carroll et al.’s (Citation2012) study achieved close to the ceiling (98% accuracy). Finally, in a study including both subjective (self-assessment) and objective data examining phonological and phonemic awareness of SLPs and teachers of the deaf (TOD), Messier and Jackson (Citation2014) found that whilst SLPs significantly outperformed the TOD, they demonstrated gaps in their knowledge. The SLP participants in this study self-rated their knowledge and confidence to teach phonological awareness as "moderate".

As a group, SLPs did not achieve ceiling scores in any of the above studies. Spencer et al. (Citation2008) suggested that SLP respondents failed to achieve expert level skill or demonstrate proficient performance, however, neither a definition of expert skill nor proficiency was established. Rather, Spencer et al. based this assessment on comparison to the level of phonemic awareness likely to be required to segment sounds in the words contained in basal readers and spelling books.

Orthographic knowledge

Krimm and Schuele (Citation2022) conducted the only known study examining the orthographic knowledge of 48 SLPs, carried out across two states in the USA. An example of tasks included identifying words that contained vowel teams from a list of nine options and identifying words that follow the "drop the silent e" rule. No participant reached ceiling and the mean of the group (65%) was well below what might be expected for those responsible for providing intervention for orthographic difficulties.

The current study

Researchers are yet to explore the knowledge, skills, beliefs, and confidence of SLPs from both a subjective and objective perspective in relation to working with children and adolescents in the literacy domain. We, therefore, sought to address this gap by studying a sample of Australian SLPs who intervene with school-aged students on language and literacy difficulties. The combination of objective and subjective data will deepen the understanding of the knowledge, skill, and expertise SLPs possess when working with children experiencing low progress in literacy. Furthermore, with the exception of Serry and Levickis (Citation2021) and Carroll et al. (Citation2012) the research outlined above has been contained to the USA, and its applicability to the Australian context is unknown. Our aims were:

To determine SLPs’ confidence, beliefs, and self-rated abilities for key language and literacy constructs considered critical to assessment and intervention in clinical practice.

To measure SLPs’ knowledge and skills regarding key language and literacy constructs critical to clinical assessment and intervention.

To explore associations between SLPs’ clinical caseload in literacy and their confidence and self-rated ability to work in the literacy domain.

To explore associations between SLPs’ clinical caseload in literacy and their knowledge and skills concerning literacy constructs essential for clinical practice.

To explore associations between SLPs’ skills and knowledge of language and literacy constructs with their confidence and their self-rated ability to work in the literacy domain.

To compare SLPs’ knowledge versus skill regarding key language and literacy constructs critical to clinical assessment and intervention.

Method

Participants and recruitment

To be eligible to participate in the study, respondents needed to (a) have obtained their SLP qualification in Australia, (b) be practicing in Australia at the time of participating in the survey, (c) be eligible for Speech Pathology Australia membership, and (d) work with school-aged children. Convenience sampling was used to recruit respondents. The survey was advertised via two Australian-based Special Interest Groups, Speech Pathology Australia’s eNews, the Developmental Disorders of Language and Literacy network, the three Twitter handles of the authors (all of whom work in Australia), and 11 closed, professional, Australian-based reading science and/or SLP clinical practice Facebook groups. SLPs wishing to participate clicked an electronic link that took them to an anonymous online survey hosted on the QualtricsXM platform. Reminders were posted on Twitter two and four weeks after the original tweeted advertisement. Approval for the study was granted by the La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee (HEC20378). The survey was open for a period of six weeks across October and November 2020. After reading an online participant information and consent form, participants entered the survey by clicking "I consent to participation in the survey".

Two hundred and sixty-two respondents answered at least one question. Incomplete surveys (n = 31) were not analysed. The median time to complete the survey was 16.7 minutes. The analysis is based on full responses of 231 SLPs. They represented all six states and one of the two territories of Australia, although the states of Victoria and Queensland accounted for 80% of the sample. Seventy percent had gained their SLP qualification in the last ten years. The majority (n = 170; 74%) reported that clients with literacy-based needs made up more than 20% of their clinical caseload. describes participants’ professional profiles and their demographic characteristics.

Table I. Respondent characteristics.

Survey instrument

Our survey was based on a tool employed by Stark et al. (Citation2016; previously used to assess teacher knowledge). However, some changes were made as adaptations for an SLP audience and to ensure question accuracy. The survey comprised 32 items across four areas: beliefs about reading disabilities; self-rated confidence in areas related to speech-language pathology literacy-based practice; skills and knowledge related to basic language constructs; and participants’ background characteristics (see Supplementary Materials 1). Nine items explored participants’ demographic characteristics including their geographic location, employment sector, time since qualification, and years of clinical experience working with school-aged clients. One question asked SLPs to identify sources of training that had prepared them to work with students with literacy difficulties. Using a four-point scale, SLPs were asked to rate their confidence ("minimal", "moderate", "very good", "expert") across 17 areas related to literacy intervention. These included: using assessments to inform intervention; working with students who have learning difficulties; and intervention for spelling, phonics, and written language. A measurement of SLPs’ views and beliefs associated with reading disabilities was also adapted from Stark et al.’s work. SLPs were asked to respond to ten statements by indicating their beliefs about reading and reading intervention on a four-point scale, ("strongly disagree", "somewhat disagree", "somewhat agree", "strongly agree"). For example, (a) "Children with reading difficulties have problems in decoding and spelling but not in listening comprehension", and (b) "Children with reading difficulties need a particular type of remedial instruction which is different from that given to typically developing readers". One item from Stark et al.’s survey was removed as it explored teacher training, which was not relevant to this study. This was replaced by the question, "Most speech pathologists receive adequate training at university to work with children with reading difficulties". We added two items to capture beliefs about auditory processing and "brain training" programs.

Eighteen items were concerned with content knowledge of basic language constructs. These were adopted from the survey items used in Stark et al.'s (Citation2016) study and we included an option for respondents to provide comments. To promote the ease with which respondents could be open about disclosing possible knowledge gaps, the term "don’t know" used by Stark et al. was changed to "not sure". Three items had alternative options provided to those in Stark et al.’s survey. When asking participants to determine the number of phonemes in a word, the item box was replaced by exit due to our perceived overuse of spelling examples with word-final X (e.g. box, wax, mix) in SLP training and professional development workshops. Two items were adjusted due to perceived errors in the options provided in previous survey iterations. In, "Which of the following words contains a diphthong?", the original survey had two correct options, coat and boy. Therefore, the option coat was replaced with cart, whilst the option boy was retained. For, "A voiced consonant digraph is present in the word…", again, two options offered were judged by us as correct in Stark et al.'s (Citation2016) survey, the and whip. Therefore, the option the was replaced by Chicago, (the voiced "th" was considered too familiar to SLPs given their work in speech sound disorders). The word whip was replaced with write due to the possibility that the onset of whip could be pronounced either /w/ or /hw/, the latter no longer representing a voiced consonant digraph. One item had 7 components (speech sounds) and one item had 14 components (syllables and morphemes).

Stark et al. (Citation2016) categorised each item in their survey tool as addressing an aspect and a domain. We adhered to Stark et al.’s definition of aspect as including phonemic awareness, phonological awareness, phonics, and morphology. We deviated from Stark et al.’s categorisation by classing etymology as a single aspect rather than other". As with Stark et al.’s survey tool, items measuring phonemic awareness related to the perception and manipulation of single sounds within words. Items assessing phonological awareness related to perception and manipulation of syllabic units. Phonics items measured knowledge of letter-sound correspondences and spelling rules/generalisations. Items measuring morphology focused on the use of lexical and sublexical units of meaning to support decoding or comprehension.

The domains measured were knowledge and skill. Consistent with Stark et al. (Citation2016), knowledge items measured explicit knowledge such as definitions. For example, selecting the correct response to question 6, "A phoneme refers to…" was classed as knowledge. Skill items measured an implicit ability to complete tasks (and were independent of one’s ability to identify the definitions of specific terms). For example, "How many speech sounds are there in the following word: ship" (question 10) was classed as skill. Upon completing the knowledge and skill items, SLPs were asked to reflect on their experience completing this section of the survey. They were specifically asked to rate their confidence responding to the language and literacy items using a five-point scale (i.e. "not at all", "somewhat", "neutral", "very", "extremely").

Data analysis

Data were checked and cleaned prior to analysis. Due to the availability of the option for open-text statements, some respondents included their own wording for definitions in the knowledge-based questions of the survey. Other respondents used the open-text feature to provide commentary on the perceived accuracy or integrity of survey items. Open-text statements were reviewed and then coded as correct or incorrect for all knowledge/skill items. For example, when defining a phoneme, rather than selecting the option, "a single speech sound", three participants provided a comment. The comment "single sound unit" was marked as incorrect as it did not capture the speech aspect of phoneme, whereas the comment "the smallest unit of speech sound" was credited as correct. For the item, "A combination of two or three consonants pronounced so that each letter keeps its own identity is called", the comments "a consonant cluster" and "adjacent consonants" by 18 respondents were credited as correct, whereas "digraph or trigraph" was not. For the item, "What type of task would the following be ‘say the word ‘cat’, now say the word ‘cat’ without the/k/sound" the correct option was "deletion". Where respondents selected "comment (other)" and typed "elision" this was credited. However, for respondents who commented "phoneme manipulation" credit was not given as deletion is a specific phoneme manipulation task separate from other phoneme manipulation tasks (i.e. phoneme insertion or phoneme substitution). If a participant selected "none of the above" and then provided a comment indicating clear understanding aligned with the target response, credit was provided. One such example was, "None of the above, not language I would use, I assume you mean answer x". Each item had only one correct option. Where respondents selected multiple responses, this was coded as incorrect. This decision was made in order to not over-credit those hedging their bets and because respondents were encouraged to select "not sure" where appropriate. When respondents selected "not sure" this was marked as incorrect. Ten respondents noted that the question, "If you say the word, and then reverse the order of the sounds, ‘enough’ would be…" depended on an individual’s pronunciation of the first syllable. Some stated the options provided did not reflect how they pronounce the word. This indicated that the participants could recognise the target answer. The Macquarie dictionary provides two Australian pronunciations for enough. It was expected that Australian SLPs would be familiar with the three differences in the Australian accent (broad, general, and cultivated). Therefore, those participants indicating "none of the above" based only on their personal pronunciation did not receive credit. Those who stated "none of the above" but then acknowledged that funny would be the answer for another accent, but not their own, received credit. For the question, "For each of the words below, determine the number of morphemes" we recognise that strictly speaking, disassemble and observer both contain three morphemes. However, after consultation with two senior academic linguists at La Trobe University, the response of two morphemes was coded as correct. This was based on the understanding that whilst etymologically there are three morphemes, they do not pass tests for being productive morphemes in modern English. Productive morphemes are defined for our purposes as those that are functionally relevant at an intervention level, rather than accurate at a specialised linguistic level. After checking and cleaning the data, descriptive statistics for accuracy of each of the 37 questions were calculated. Correlations using Spearman’s rho were calculated for: (a) years since gaining SLP qualification and performance (i.e. total score on knowledge and skill); (b) confidence and performance; (c) years since gaining SLP qualification and confidence; (d) percentage of caseload involving literacy and performance; (e) performance and professional practice specifically in primary or secondary settings; and (f) percentage of caseload involving literacy and confidence.

Result

Beliefs and views

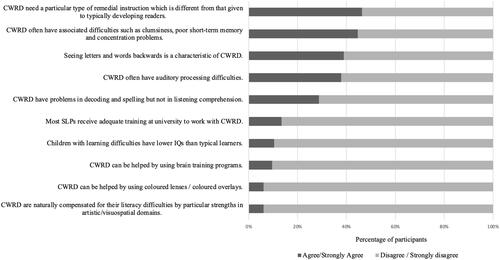

Descriptive data concerning respondents’ agreement with a series of ten belief-related statements about children struggling with literacy are presented in . There was strong consensus in response to “Reading difficulties can be helped by using coloured lenses/coloured overlays” with 93% disagreeing with the statement. Similarly, the majority of respondents (90%) “disagreed” or “strongly disagreed” with the statement “Children with learning difficulties have lower IQs than typical learners”. Regarding SLP preparation, only 13% of respondents “agreed” or "strongly agreed" while 87% “strongly disagreed” or “disagreed” with the statement, “Most speech pathologists receive adequate training at university to work with children with reading difficulties”.

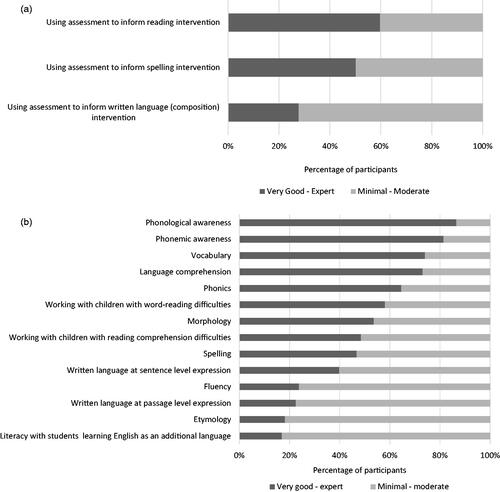

Figure 1. Respondents’ level of agreement with belief-related statements. Note. CRWD = children with reading difficulties.

Thirty-nine percent “somewhat” or “strongly” agreed with the statement, “Seeing letters and words backwards is a characteristic of children with reading difficulties”. Over half (54%) of the sample agreed that “Children with reading difficulties need a particular type of remedial instruction which is different from that given to typically developing readers”. Just over one-third (38%) of respondents agreed with the statement “Children with reading difficulties often have auditory processing difficulties”. Twenty-nine percent of respondents believed that reading difficulties were contained to spelling and decoding, and did not include receptive language difficulties. A limited number of respondents (9.5%) indicated agreement that “Children with reading difficulties can be helped by brain training programs”.

Sources of training and professional development

Fifty-four percent of respondents indicated that some training was provided as "part of their SLP program". Regarding professional learning, 93% had accessed further training "through self-teaching activities such as reading journal articles, blogs, books and other materials related to literacy", and 94% through "continuing education activities such as workshops or conferences". Collaboration with interdisciplinary colleagues was also identified as a source of professional development by 46% of the respondents, and 37% sought the guidance of a mentor.

Confidence

Self-rated confidence regarding responses to items measuring knowledge and skill

In relation to overall confidence responding to survey knowledge and skill items, 40% indicated they reported feeling "very" or "extremely" confident, whilst 29% indicated they felt "somewhat" confident and 2.6% were "not at all" confident. Sixty percent of respondents attributed the source of "most of their knowledge" in their responses to the survey items to "professional development"; and 15.6% to "experience in the clinic". Only 8.7% attributed their confidence to their university-based SLP training.

Self-rated confidence in areas of practice

Descriptive data for each area where respondents self-rated their confidence are presented in . When reporting their confidence in using assessment to inform intervention, the area with the strongest reported confidence was using assessment to inform reading intervention. The lowest confidence was for using assessment to inform written language intervention. For intervention, respondents reported the strongest confidence to work in the areas of phonological and phonemic awareness. Lower confidence was reported for the areas of fluency, passage-level written language, etymology, and working with students who are learning English as an additional language.

Skill/knowledge

Respondents’ scores on the skill/knowledge items of the survey ranged from 22 to 37 out of 37 with a median of 34 (median accuracy = 92%). Twenty-six respondents (11.3%) received a perfect score. The median score for knowledge was 10 (83%) from a possible 12. The median score for skill was 24 (96%) of a possible 25. shows the median score for survey items according to their classification under domains (knowledge and skill) and aspects (phonological, phonemic, phonics, morphological, and etymology). For total score (combining knowledge and skill), participants achieved the highest median accuracy for phonological awareness (100%) and the lowest median accuracy for phonics (75%). In the aspects of morphology and phonics, the range observed for both knowledge and skill was 0%−100%.

Table II. Median scores on survey items by aspect and domain.

Phonemic awareness

Respondents’ performance across all tasks reliant on phonemic awareness knowledge ranged from 20% to 100% (median = 80%). For tasks measuring phonemic awareness skill, the respondents’ performance ranged from 50% to 100% (median = 100%). When stating the number of phonemes in words, the group was weakest for exit with 81% of the sample correctly selecting five phonemesFootnote1, and strongest for ship with 100% percent of the sample selecting three. See Supplementary Materials 2for a full breakdown of group accuracy scores for survey items measuring phonemic awareness knowledge and skill.

Phonological awareness

Knowledge. When asked to select the correct definition for phonological awareness, 75% of respondents were able to do so. Seventeen (7%) misidentified phonological awareness as, "the ability to use letter-sound correspondence to decode" (a definition of phonics) and 29 (12.5%) indicated that none of the options provided was a suitable definition. Skill. Despite difficulties defining phonological awareness, in the only task measuring skill (syllable identification) respondents’ performance across all seven items ranged from 71% to 100% (median = 100%). Respondents’ ability to correctly identify the number of syllables in individually presented words ranged from 97% of the sample being correct (for disassemble) to 100% of the sample being correct (for heaven, observer, teacher). See Supplementary Materials 3 for a breakdown of respondents’ performance on the syllable counting tasks.

Phonics

Knowledge. Three items assessed phonics-specific knowledge. Ninety-two percent of respondents selected the correct definition "a consonant blend"; 78% of the sample correctly identified the word that contained a "soft ‘c’ sound", whilst only 56% correctly identified the word with a voiced consonant diagraph. Skill. On the only skill-related task for phonics, 98% of respondents identified a word that contained the same vowel sound as the non-word tife.

Morphology

Knowledge. Ninety-seven percent of respondents were able to identify the correct definition of a morpheme, compared to 91% who could identify the correct definition of morphemic analysis. Skill. One task with seven items measured skill (morpheme identification). Respondents’ accuracy across all seven items ranged from 0% to 100% (median = 86%). The percentage of all respondents correctly identifying the number of morphemes for individual items ranged from 73% (for disassemble) to 92% (for heaven). See Supplementary Materials 4 for a full breakdown of respondents’ ability to count morphemes for all seven items presented.

Correlational analysis

A weak statistically significant positive correlation was found between overall performance on the skill/knowledge items of the survey and self-rated confidence (r = 0.350, p = <0.001), however, it is noted that this accounts for only 12.25% of shared variance (r2) between the variables. No significant association was found between self-rated confidence and the percentage of literacy caseload. No significant associations were found between overall performance and years of experience, percentage of literacy caseload, and professional practice specifically in primary or secondary settings (p. <0.001 in all cases).

Discussion

Our study provides novel insights into both subjective and objective data about the perceptions, beliefs, knowledge, and skill regarding language and literacy constructs of a sample of Australian SLPs who, as a result of working with school-aged children, may be required to provide services to children with literacy difficulties. Results regarding respondents’ capabilities across linguistic constructs essential for literacy intervention and assessment were largely skewed towards higher levels. However, individual variation was significant. Eleven percent of the sample scored 100%, however, it is not possible to compare this finding with previous studies, as the level of achievement of individuals in samples was often not reported.

Overall, the sample performed slightly better on skill-based tasks (median accuracy = 96%; range = 64%−100%) compared to knowledge-based tasks (median accuracy = 83%; range = 33%−100%). The median skill score for phonemic awareness, phonological awareness, and phonics was 100%. Morphology skill was an area of relative weakness (median score = 85%; range = 0–100%). The performance on counting morphemes was particularly concerning when looking at specific examples. Morphological development (e.g. Brown, Citation1973) is an inherent component of typical and atypical language development and, as such, would be an assumed component in speech-language pathology programs. In our sample, 10% of respondents were unable to identify the number of morphemes in teacher and 13% the number of morphemes in frogs (an item containing the fourth of Brown’s morphemes, the regular plural marker "-s"). Furthermore, both the regular plural maker, "-s", and the derivational morpheme, "-er", are used as assessment items in standardised language assessment tools commonly used with school-aged students in Australia (e.g. Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals Australian and New Zealand, Fifth Edition; Wiig et al., Citation2017). In addition, other assessments SLPs are trained to administer rely on a robust knowledge of morphology in order to be correctly administered and scored. For example, the mean length of utterance (MLU; Miller, Citation1981) is a measure of grammatical complexity, the accuracy of which is dependent on the assessor’s knowledge of morphology and its development.

In this type of research study, phonological awareness/phonemic awareness items are not delivered orally. This may have influenced respondents’ accuracy due to orthographic intrusion. Given their extensive training in the phonological structure of language, qualified SLPs should be able to suppress orthography when required for sound-based analysis. The median accuracy for phonemic awareness skill was 100%, however, the range was 50%−100%. This demonstrates a somewhat concerning degree of variability between SLPs and has implications for the consistency of phonemic awareness assessment and intervention provided between SLPs. Some individuals in our sample may struggle to complete tasks that might routinely be asked of a client in either assessment or therapy (e.g. identifying the number of sounds in words, identifying two words that share a sound when the spelling is different). The number of items in the survey assessing knowledge was lower than for skill. There were five knowledge items for phonemic awareness (median = 80%; range 20-100%). The lower median accuracy and the greater variability between respondents is even more concerning than that observed for skill. Understanding the theoretical constructs behind the specific subskills of literacy is critical to informing decision-making regarding what to assess and include in intervention.

The results obtained for phonological awareness skills should be interpreted with caution as the survey did not examine this area in full. Regarding phonological awareness knowledge, it is concerning that 25% of the sample was unable to select the correct definition for phonological awareness. If this result is not explained by possible confusion arising from the provision of multiple-choice options, it raises questions concerning what some SLPs assess and give for intervention when they believe they are targeting phonological awareness. Given that one-quarter of the sample did not select the correct definition of phonological awareness, the level of confidence indicated by the sample for providing intervention for phonological awareness may need to be interpreted with caution. It may be that 25% of the sample have indicated a level of confidence regarding a different concept.

Overall, the results indicate that as a group, the knowledge and skill of core linguistic constructs that are central to the provision of evidence-based assessment and intervention in literacy has a favourably skewed distribution towards higher levels of knowledge and skill. However, the range observed between the highest and lowest-performing individuals indicates that in specific areas, significant variability exists. This raises concerns regarding the consistency and integrity of literacy assessment and intervention services offered between SLPs.

The multiple-choice format of the survey may have assisted SLPs to narrow down options via a process of elimination, increasing the likelihood of correct responses. Whilst the same process was adopted in iterations of the survey used for teacher populations, we suggest that due to the format of the survey, the results regarding knowledge and skill should be interpreted with some caution. The reality of working in real time with students is that clinicians do not have a prompt or a scaffold to support their knowledge or in the moment thinking. We know that standardised assessments provide answers. However, the absence of strong knowledge and skill, in conjunction with limitations in test scoring and interpretation, may compromise assessment and diagnosis. A suggestion for augmenting the validity of the results obtained in this study is to conduct a research study where possible answers are not provided. This would serve to determine the unprompted level of knowledge respondents possess.

As a group, the sample expressed a high degree of confidence in their ability to provide intervention for phonological awareness, phonemic awareness, and vocabulary. There was a notable contrast in confidence between language in the oral and written domains. Whilst 74% expressed "very good" to "expert" level confidence in supporting both vocabulary and language comprehension difficulties, only 49% felt equally confident to address reading comprehension difficulties. This appears to indicate a disconnect in SLPs’ understanding of the oral language to literacy nexus. Reading comprehension is built upon language comprehension (e.g. Nation, Citation2019). The data suggest that SLPs have not fully embraced the connection between the skills they perceive they have in addressing language comprehension and vocabulary as the very skills that will bootstrap reading comprehension. Additionally, language and vocabulary are also key tools for constructing written sentences and passages (Snow, Citation2020b). Despite the strong confidence expressed for language and vocabulary, only 40% of the sample expressed confidence to address sentence-level writing and even less, 22%, were confident to provide intervention for passage-level writing. Despite the median accuracy in total morphology score of 88%, only just over half of the sample expressed confidence to provide intervention for morphology. While the group demonstrated a substantial skill set in morphology, the confidence did not follow. This contrasted with the finding of Serry and Levickis (Citation2021) where 73% of their sample reported confidence in their capability and confidence to work on morphological awareness.

As clinicians, SLPs have a range of standardised published assessment tools available to them to assess and measure the language and literacy skills of students. Concerningly, only 60% of the sample expressed "very good" to "exper"’ level confidence in "Using assessment to inform reading intervention". It was alarming to note that only half of the sample felt confident to assess spelling and just 27% reported "very good" to "expert" level confidence in assessing written language. This finding mirrors the low levels of confidence in the assessment of written language and spelling observed in Blood et al.'s (Citation2010) study, and both low assessment rates and low knowledge of what assessments to conduct reported by Loveall et al. (Citation2022). Speech-language pathology training involves extensive tuition on the administration and delivery of both standardised and dynamic assessments. With such training, as new assessment tools are published, an SLP should be competent to read manuals, administer the assessment, and calculate results with fidelity. It should give the profession pause for thought that a significant proportion of practising SLPs lack confidence in the first step of clinical practice, assessment. Future research should explore the barriers and reasons for such low levels of confidence. It may be that SLPs are unaware of the breadth of assessment tools available, work in settings with limited access to assessments, or have reduced confidence in their ability to interpret test results that would then inform intervention.

The relationship between overall performance and self-rated confidence reported here suggests that SLPs are able to somewhat align their knowledge, skills, and confidence. Although in some areas, it may be that SLPs’ level of confidence is lower than the level of knowledge and skill that they possess. For example, this was suggested by the results indicating a discrepancy between performance on the morphology items and perceived confidence in providing intervention for morphology. However, whilst overall performance on the skill/knowledge items of the survey and self-rated confidence were significantly correlated, their association accounts for only a little over 12% of the shared variance. A notable finding was the lack of correlation between performance and (a) years of experience, (b) professional practice specifically in literacy, and (c) professional practice specifically in primary or secondary settings. One may hypothesise that more years of experience, a large caseload of literacy, or substantial practice experience in schools would drive an accumulation of literacy specific professional learning. It is reasonable to expect that such professional learning would lead to a level of literacy expertise superior to that of colleagues with either less experience or less professional interest in literacy. In our sample, this hypothesis is unsupported.

Speech-language pathology is not immune to its practitioners subscribing to the same myths that are believed by many teachers (Stark et al., Citation2016). As such, there is a risk that these myths may influence the beliefs and views of practicing SLPs. Over half of the sample believed that, "Children with reading difficulties need a particular type of remedial instruction which is different from that given to typically developing readers". It is unclear how this question was interpreted by respondents. For SLPs working with students who are taught in balanced literacy classrooms, it would be reasonable to agree that low-progress readers need something different because of the lack of explicit instruction in decoding in a balanced literacy pedagogy (Snow, Citation2020a). For respondents who interpreted this question according to the principles of response to intervention where what changes for struggling students is the intensity, not the type of instruction (Fuchs et al., Citation2003), disagreement would have been expressed.

In light of the abundance of evidence indicating that reading difficulties are underpinned by language processes (Adlof & Hogan, Citation2019; Snowling & Hulme, Citation2021), it was problematic that 39% of respondents "somewhat" or "strongly" agreed with the statement "Seeing letters and words backwards is a characteristic of children with reading difficulties". Regarding the controversy about the existence (or lack thereof) of auditory processing difficulties as a robust differential diagnosis (Bowen & Snow, Citation2017), it was concerning to note that over one-third (38%) of respondents agreed with the statement, "Children with reading difficulties often have auditory processing difficulties". Reviews of the evidence-base for auditory processing disorder suggest an absence of definitive diagnostic and treatment procedures (Richard, Citation2011), and that perceived listening difficulties are more adequately explained by cognitive, linguistic, and attentional deficits rather than deficits in auditory processing (de Wit et al., Citation2016).

Twenty-nine percent of respondents believed that reading difficulties were contained to spelling and decoding, and did not include receptive language difficulties. This suggests an oversight of the importance of the pivotal role of oral language for proficient reading comprehension. It may be that our sample had a narrow focus on code-based skills and overlooked the end-point of reading as text comprehension. However, given the reported confidence of the sample for addressing language comprehension and vocabulary (74% "very good" to "expert"), it appears more likely that nearly 30% of our sample are insufficiently familiar with models such as Gough and Tunmer’s (Citation1986) simple view of reading in which language comprehension is a critical and non-negotiable part of the reading process. Practising SLPs need to be aware of such a model of reading given it was first posited almost 40 years ago, has been empirically validated (Hoover & Gough, Citation1990), is referenced widely in the literature (Castles et al., Citation2018), and was recently updated (Tunmer & Hoover, Citation2019).

A small but notable proportion of respondents (9.5%), indicated agreement that, "Children with reading difficulties can be helped by brain training programs". It is troubling that nearly one in ten respondents endorsed so-called brain training programs. Although there are a number of programs that capitalise on the premise of training neuropsychological processes such as attention, working memory, or "thinking skills" (e.g. Cogmed, Brain Gym, the DORE program, Neurofeedback), they all share a lack of empirical evidence (Bowen & Snow, Citation2017).

It appears that university preservice content on integrating evidence into practice, fundamentals of research, and evidence-based practice are yet to fully buffer SLPs from the myths that continue to permeate the language, literacy, and learning space (Bowen & Snow, Citation2017). As such, there is much work to be done to ensure that SLPs leave their preservice training able to update their beliefs in line with new (or established) evidence and to adhere to Speech Pathology Australia’s (Citation2020) code of ethics (i.e. 1.2 Professional Conduct and 3.2 Evidence-Based Practice).

A distinct lack of endorsement for the adequacy of preservice training was expressed, with only 13% of respondents agreeing with the statement "Most speech pathologists receive adequate training at university to work with children with reading difficulties". This is consistent with Serry and Levickis’ (Citation2021) finding for a different sample of Australian SLPs and mirrors the generally low perception expressed by SLPs from the USA (Blood et al., Citation2010; Fallon & Katz, Citation2011; Loveall et al., Citation2022). However, despite the perceived inadequacy of university coursework, studies have repeatedly demonstrated that SLPs outperform their teaching colleagues with regard to knowledge and skill of literacy constructs. This raises questions as to the reasons for such low appraisal of SLP preservice training. It is possible that SLPs are underappreciating the depth of their theoretical and clinical training. As noted earlier, the preservice training that SLPs undertake includes phonology, semantics, syntax, and morphology (Fallon & Katz, Citation2020). SLPs may be overlooking the contribution this has implicitly made to their knowledge, skills, and confidence with respect to literacy service provision. Our correlational analysis demonstrated no significant relationship advantaging SLPs who work regularly in literacy, nor those with more years of experience. These SLPs do not appear to possess knowledge and skills superior to that of their counterparts who have not actively pursued a literacy-based caseload. This suggests that SLPs’ perception of their knowledge as not being a result of preservice training might be incorrect, or at least not fully correct. However, such a perception cannot be ignored. As the end users of the qualification obtained, it is critical that reasons why SLP training in literacy is held in such low esteem are explored. It may be that university courses have failed to make the clinical relevance of coursework explicitly evident to preservice students. Clinical practicums may have been lacking in length of placement, breadth of placement focus, or even equitable availability of a literacy-centred placement to all students. As such, graduates may lack confidence in their ability to apply theoretical knowledge to the assessment and intervention sphere. It may be that leaving university with theoretical knowledge that is immediately contradicted by the ideologies that permeate classrooms leaves new graduates confused, unsure of their position, and lacking confidence in their training. Finally, whilst surveys have measured knowledge, skill, and confidence, this has always been removed from the real-world practice of the SLP. It is possible that SLPs possess textbook knowledge and skills that can be performed using implicit knowledge, but lack the ability to impart this to clients. The lack of satisfaction with coursework may reflect confidence in clinical competence, which has not been possible to measure or capture in survey studies. The provision of explicit accreditation requirements specifically for literacy may serve to ensure consistency amongst SLPs and also to make transparent to SLPs the level and depth of their training.

An area not covered in the survey was interprofessional communication. Practitioners such as teachers, SLPs, and educational psychologists overlap in their scope of practice with students’ literacy growth. There is a risk that variations in discipline-specific terminology may occur when discussing a single concept/construct. Respondents in our survey appeared to take issue with some terms used in the survey, such as "consonant blend" and "soft c". Whilst not a focus of the survey, concerns expressed regarding survey terminology (e.g. "We use the term ‘adjacent consonants/consonant cluster") may speak to a mindset privileging linguistic jargon. Holding such a position may not be facilitative of interdisciplinary collaborations. It was clear in these questions that participants understood the item despite the terminology used, as in addition to offering a comment, they selected the correct target. An ability to use language flexibly, respect lexical variation between professions, and to understand synonymous linguistic terms used by colleagues is likely to be beneficial to interprofessional collaboration.

It must be acknowledged that we used a slightly modified version of a survey tool previously administered to a sample of Australian teachers (Stark et al., Citation2016). Whilst direct comparisons were not a central aim, the SLP sample performed more strongly in all aspects of the survey. The strongest overlap in performance was observed between teachers and SLPs for the area of phonics and syllable counting. SLPs demonstrated significant strengths relative to Stark et al.’s teacher sample in the domains of phonemic awareness and morphological awareness. Interdisciplinary teams should seek to capitalise on the increased depth of knowledge and skill that SLPs can provide regarding linguistic constructs essential to literacy instruction beyond that of just oral language. Blevins (Citation2017) encourages the use of the SLP as both classroom support and a resource for providing professional development for teachers.

At this time there is no established definition of what constitutes expert level knowledge in SLP literacy practice, nor is there a defined level of proficiency expected of interventionists. Given the enormous number of resources (energy, time, financial, and, on the part of clients and families, emotional) invested in intervention systems, we arguably need to quantify our expectations of the level of expertise displayed by those responsible for providing intervention for students experiencing literacy difficulties. While in multiple studies (Carroll et al., Citation2012; Messier & Jackson, Citation2014; Spencer et al., Citation2008) SLPs outperform classroom and specialist teachers (reading specialists and teachers of the deaf), clearly defined levels of proficiency expected of interventionists are needed to ensure minimum expectations and consistency in the levels of knowledge between practicing interventionists.

Given that studies repeatedly demonstrate higher theoretical knowledge in SLPs, we suggest that a greater degree of interprofessional collaboration between the teaching and speech-language pathology professions is in the best interests of all students. With greater collaboration (e.g. co-planning, and the two-way sharing of knowledge between SLPs and teachers), teachers can capitalise on their expertise in teaching large numbers of students simultaneously and make the most of the high level of direct contact time they have with students—contact time that SLPs do not have.

Limitations

This study represents an initial investigation into Australian SLPs’ knowledge and confidence regarding essential constructs for literacy assessment and intervention with school-aged children. There are a number of limitations that need to be acknowledged. Firstly, SLPs from Queensland and Victoria may be overrepresented relative to the population. Although this survey has not been field-tested on SLPs, previous iterations with established reliability and validity have been used in multiple studies of teachers. While our sample qualified in Australia, this does not mean respondents do not have a first language other than English. There is a risk, therefore, that respondents’ own accents influenced decisions on some items. Another limitation lies in the tool, which was designed to measure theoretical skill and self-reported knowledge. We did not directly measure practical or clinical competence when working with clients. As such, findings should be viewed as only a proxy indicator of clinical competence. Finally, it is difficult to know whether there is a systematic bias in the respondent sample (e.g. towards SLPs who have experience working in literacy). The respondents were primarily SLPs with a significant proportion of their caseload including literacy. As such, it seems they have self-selected for the study.

Future research

To calibrate SLPs' perceptions of their knowledge and skills against reality and to identify gaps that need redress, an area that warrants investigation is the content of SLP training programs. An in-depth qualitative exploration of SLPs' perspectives and experiences in the literacy domain would enhance and augment the understanding and findings of previous research, all of which has been survey based. To further augment our understanding beyond purely theoretical knowledge and skill, a suggestion for future research is to explore clinical competence in practising SLPs (including assessment, intervention, and caseload management).

Conclusion

At a group level, SLPs demonstrated generally strong scores on knowledge and skills in language and literacy constructs. However, our findings raise concerns regarding the variability between individual SLPs across literacy-related beliefs, knowledge, and skills central to their work in the literacy domain. In order to ensure the integrity of the clinical services offered to clients, improving the consistency of the beliefs, knowledge, and skills within and between SLPs is required. Despite the variability between individuals, at a group level, performance was strong and superior to that observed in teacher populations from previous studies. As such, we argue that an ongoing place for the SLP in education literacy teams is warranted. Unfortunately, our results mirror earlier research suggesting low satisfaction with preservice training. Further research is needed to identify the reasons and remedies for this.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.6 KB)Declaration of interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2023.2202839.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available as participants did not consent to the sharing of their data in this way.

Notes

1 The number of phonemes in exit is five in both accepted pronunciations: /egzət eksət/.

References

- Adlof, S. M., & Hogan, T. P. (2019). If we don’t look, we won’t see: Measuring language development to inform literacy instruction. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 6(2), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732219839075

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association . (2016).. Scope of practice in speech-language pathology. [Scope of Practice]. https://www.asha.org/policy/sp2016-00343/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2020). 2020 schools survey: SLP caseload and workload characteristics. Rockville, MD. https://www.asha.org/siteassets/surveys/2020-schools-survey-slp-caseload.pdf

- Blevins, W. (2017). A fresh look at phonics, grades K-2: Common causes of failure and 7 ingredients for success. Corwin Literacy.

- Blood, G. W., Mamett, C., Gordon, R., & Blood, I. M. (2010). Written language disorders: Speech-language pathologists’ training, knowledge, and confidence. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 41(4), 416–428. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2009/09-0032)

- Bowen, C., & Snow, P. (2017). Making sense of interventions for children with developmental disorders: A guide for parents and professionals. J&R Press Ltd.

- Brown, R. (1973). A first language: The early stages. Harvard University Press.

- Castles, A., Rastle, K., & Nation, K. (2018). Ending the reading wars: Reading acquisition from novice to expert. Psychological Science in the Public Interest : A Journal of the American Psychological Society, 19(1), 5–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100618772271

- Carroll, J., Gillon, G., & McNeill, B. (2012). Explicit phonological knowledge of educational professionals. Asia Pacific Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing, 15(4), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1179/136132812804731820

- de Wit, E., Visser-Bochane, M. I., Steenbergen, B., van Dijk, P., van der Schans, C. P., & Luinge, M. R. (2016). Characteristics of auditory processing disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 59(2), 384–413. https://doi.org/10.1044/2015_JSLHR-H-15-0118

- Fuchs, D., Mock, D., Morgan, P. L., & Young, C. L. (2003). Responsiveness-to-intervention: Definitions, evidence, and implications for the learning disabilities construct. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 18(3), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5826.00072

- Fallon, K. A., & Katz, L. A. (2011). Providing written language services in the schools: The time is now. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 42(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2010/09-0068)

- Fallon, K. A., & Katz, L. A. (2020). Structured literacy intervention for students with dyslexia: Focus on growing morphological skills. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 51(2), 336–344. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_LSHSS-19-00019

- Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193258600700104

- Heilmann, J., & Bertone, A. (2021). Identification of gaps in training, research, and school-based practice: A survey of school-based speech-language pathologists. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 52(4), 1061–1079. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_LSHSS-20-00151

- Hoover, W. A., & Gough, P. B. (1990). The simple view of reading. Reading and Writing, 2(2), 127–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00401799

- Krimm, H., & Schuele, C. M. (2022). Speech-language pathologists’ orthographic knowledge. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 43(3), 206–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/15257401211046877

- Lanter, E., & Waldron, C. (2011). Preservice efforts to promote school-based SLPs’ roles in written language development. Perspectives on School-Based Issues, 12(4), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1044/sbi12.4.121

- Loveall, S. J., Pitt, A. R., Rolfe, K. G., & Mann, J. (2022). Speech-language pathologist reading survey: Scope of practice, training, caseloads, and confidence. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 53(3), 837–859. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_LSHSS-21-00135

- McCutchen, D., Abbott, R. D., Green, L. B., Beretvas, S. N., Cox, S., Potter, N. S., Quiroga, T., & Gray, A. L. (2002). Beginning literacy: Links among teacher knowledge, teacher practice, and student learning. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 35(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/002221940203500106

- McCutchen, D., Harry, D. R., Cox, S., Sidman, S., Covill, A. E., & Cunningham, A. E. (2002). Reading teachers’ knowledge of children’s literature and English phonology. Annals of Dyslexia, 52(1), 205–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-002-0013-x

- Messier, J., & Jackson, C. W. (2014). A comparison of phonemic and phonological awareness in educators working with children who are d/deaf or hard of hearing. American Annals of the Deaf, 158(5), 522–538. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2014.0004

- Miller, J. F. (1981). Assessing language production in children: Experimental procedures. Allyn & Bacon.

- Moats, L. C. (2020). Teaching reading is rocket science, 2020: What expert teachers of reading should know and be able to do. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/moats.pdf

- Nation, K. (2019). Children’s reading difficulties, language, and reflections on the simple view of reading. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 24(1), 47–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404158.2019.1609272

- New Zealand Speech Language Therapists’ Association. (2012). Scope of practice. http://www.speechtherapy.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/NZSTA-Scope-of-Practice-2012.pdf

- Richard, G. J. (2011). The role of the speech-language pathologist in identifying and treating children with auditory processing disorder. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 42(3), 297–302. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2011/10-0080)

- Serry, T., & Levickis, P. (2021). Are Australian speech-language therapists working in the literacy domain with children and adolescents? If not, why not? Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 37(3), 234–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265659020967711

- Snow, P. (2020a). Balanced literacy or systematic reading instruction? Perspectives on Language and Writing, 46(1), 35–39.

- Snow, P. C. (2020b). SOLAR: The science of language and reading. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 37(3), 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265659020947817

- Snowling, M. J., & Hulme, C. (2021). Annual research review: Reading disorders revisited – the critical importance of oral language. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 62(5), 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13324

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2020). Speech Pathology Australia code of ethics 2020. https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/Members/Ethics/Code_of_Ethics_2020/SPAweb/Members/Ethics/HTML/Code_of_Ethics_2020.aspx?hkey=a9b5df85-282d-4ba9-981a-61345c399688

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2021). Practice guidelines for speech pathologists working in childhood and adolescent literacy: Revised [Clinical Guideline]. https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au

- Speech-Language and Audiology Canada. (2016). Scope of practice for speech-language pathology. Ottawa: Speech-Language and Audiology Canada. https://www.sac-oac.ca/sites/default/files/resources/scope_of_practice_speech-language_pathology_en.pdf

- Spencer, E. J., Schuele, C. M., Guillot, K. M., & Lee, M. W. (2008). Phonemic awareness skill of speech-language pathologists and other educators. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 39(4), 512–520. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2008/07-0080)

- Spencer, E. J., Schuele, C. M., Guillot, K. M., & Lee, M. W. (2011). Phonemic awareness skill of undergraduate and graduate students relative to speech-language pathologists and other educators. Contemporary Issues in Communication Science and Disorders, 38(Fall), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1044/cicsd_38_F_109

- Stark, H. L., Snow, P. C., Eadie, P. A., & Goldfeld, S. R. (2016). Language and reading instruction in early years’ classrooms: The knowledge and self-rated ability of Australian teachers. Annals of Dyslexia, 66(1), 28–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-015-0112-0

- Tunmer, W. E., & Hoover, W. A. (2019). The cognitive foundations of learning to read: A framework for preventing and remediating reading difficulties. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 24(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404158.2019.1614081

- Wiig, E. H., Semel, E., & Secord, W. A. (2017). CELF-5 Clinical evaluation of language fundamentals (Australian & New Zealand.). Pearson.