ABSTRACT

Observed climate changes in Pacific island countries (PICs) are causing detrimental effects on the health of communities. Increased frequency and intensity of cyclones, more extremely hot days, and changes in rainfall patterns can change the geographic distribution of vector-borne diseases, decrease food and water security and safety, and strain health service capacity. These impacts are projected to worsen with additional climate change in the absence of strong and effective mitigation and adaptation measures. Health vulnerability and adaptation assessments conducted in twelve PICs in 2014 highlighted significant knowledge gaps on the national health risks of climate change and on adaptation implementation and policy translation. We synthesize recent research to identify approaches to support evidence-based policymaking to increase resilience of health systems in the Pacific. Broad areas where further and substantial investment and support are needed include: (i) health workforce capacity development; (ii) enhanced surveillance and monitoring systems, and (iii) research to enhance understanding of risks and effective interventions and their subsequent translation into practice and policy. Finally, health facilities need urgent upgrades; many are old and located in coastal areas, and are heavy users of coal-fired electricity.

1. Introduction

Climate change has diverse adverse impacts on human systems (Pörtner et al., Citation2022), and is a core challenge to the global sustainable development agenda. Climate change is increasing the intensity of extreme weather and climate events and contributing to sea-level rise (Pachauri & Meyer, Citation2014), threatening lives and livelihoods and disrupting the delivery of health care services (Smith et al., Citation2014). Other key climate-related risks in the Pacific include the decline and loss of coral reef ecosystems; ocean acidification and warming sea temperatures cause coral bleaching threatening the food chain (80% of the protein source in the Pacific come from fish and other seafood) (Charlton et al., Citation2016; Johnson & Watson, Citation2021). Weather patterns like El Niño contribute to injuries and deaths, through increasing food and water insecurity. PICs, particularly those that are lower income, are among the most vulnerable countries to climate change, including its damaging impacts on human health. Those most affected by the health risks of climate change include the very old and very young, women, Indigenous peoples, and people living with disabilities. Most Pacific populations live in coastal areas that are vulnerable to sea level rise and coastal erosion.

In PICs, many health indicators are not advancing as rapidly as they are elsewhere, primarily due to challenges including inadequate human and financial resources and fragmented implementation (Matheson et al., Citation2017). Rates of NCDs and child mortality exceed global averages in the Pacific and the percentage of the population accessing improved water and sanitation facilities is lower than the global average; a worrying trend (Matheson et al., Citation2017).

Without significant and timely mitigation and proactive adaptation, climate change will increase health risks via direct, indirect, and tertiary pathways (Haines & Ebi, Citation2019; IPCC, Citation2022). Direct impacts include injury and death from extreme weather (storms, cyclones, floods, heat waves). Indirect effects that are ecologically mediated include an increased risk of infectious disease and malnutrition. Additionally, tertiary or diffuse health impacts are mediated through social systems and include loss of livelihoods, conflicts over resources, and migration (Schwerdtle et al., Citation2018; Weir & Virani, Citation2011). There is an emerging understanding of the mental health impacts arising from current and future climatic changes in the Pacific (McIver et al., Citation2016) and globally (Berry et al., Citation2018).

The vision of ‘Healthy Islands’ for the Pacific countries, endorsed a quarter of a century ago and reiterated in 2015 (World Health Organization, Citation2015c), recognizes that natural and human systems are closely linked and that enhancing healthy communities requires ecological balance. This vision acknowledges the intimate connections between economic development, environmental management, and human health, particularly in the ‘very fragile physical environment of the islands’ (Nutbeam, Citation1996). The WHO Western Pacific Framework for Action on Health (2017) notes ‘Environmental determinants of health are responsible for more than a quarter of the burden of disease in the Western Pacific Region’ (WHO, Citation2017). All Small Island Developing States (SIDS), which includes Pacific SIDS, need to ensure that the health effects of climate change are included in national development plans (Tukuitonga & Vivili, Citation2021).

We synthesized research on climate change and human health in the Pacific to address three research questions:

How do the health risks of climate change, and the associated policy responses, compare across PICs;

What are the knowledge gaps; and

What evidence-based approaches support policymaking to effectively manage current and emerging climate change and human health impacts in the region.

2. Methods

We conducted a narrative review (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Levac et al., Citation2010) focusing on the entire region, with particular attention to Papua New Guinea (PNG), Solomon Islands, Fiji, and Samoa (See ). These countries were chosen as they are priority countries for Australian aid and development funding. Four academic databases (Ovid Medline, PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus), Google Scholar, and the grey literature were searched using a modified PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) search strategy that included Population/Context (concept 1); Exposure (concept 2), Outcome (concept 3) (or PEO). Included articles needed to address all three concepts and had to be published between 2011 and 2022 (). Recent key WHO reports were also included.

Figure 1. Map of Pacific region. Copyright of the Pacific Community (SPC) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com].

![Figure 1. Map of Pacific region. Copyright of the Pacific Community (SPC) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com].](/cms/asset/0af73743-4d00-407d-be2f-7359ecce19fa/tcld_a_2185479_f0001_oc.jpg)

Table 1. Literature review search strategy (Across: AND. Down: OR).

The search strategy guided the selection of included articles (). Data that most closely answered the research questions were extracted from the selected articles and synthesized, with an emphasis on the four priority countries. When context-specific evidence was missing, evidence from other settings was substituted and identified as such.

One reviewer (PNS) scanned articles for the title and abstract and then full text for relevance to the research questions. We did not undertake a quality appraisal of selected articles; however, the article or report needed to include empirical data and be published in an academic journal (see : inclusion and exclusion criteria).

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.1. Grey literature

In addition to the four academic databases, evidence was sourced from the grey literature including WHO, FAO, The World Bank, IPCC AR5 and SR1.5, Secretariat of the Pacific Community, SPREP, and the DFAT website.

3. Findings

3.1. Pacific context: current situation, projections, and adaptation planning

From 2011 to 2013, WHO partnered with 12 PICs to undertake climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessments (V&As) and develop national climate change and health adaptation/action plans (NCCHAPs or similar). These documents, essentially precursors to the Health National Adaptation Plans (HNAPs), are now being updated. The HNAPs provide the overall strategic direction for strengthening health systems to protect health from climate change and assist the incorporation of health issues into the country-level NAPs. They include upstream drivers of health risks, taking into consideration the physical, social, and biological determinants of health. The following section gives a broad overview of the climate change and health situation in each country and outlines current and planned activities concerning climate change and health.

3.1.1. Fiji

Fiji is an upper-middle-income country in the South Pacific Ocean with a population of almost 900,000 people. Situated mostly on volcanic islands, Fiji is rich in natural resources and frequently experiences storm surges, cyclones, earthquakes landslides, and flooding (WHO, Citation2015/Citation2021). Although Fiji contributes minimally to greenhouse gas emissions globally, the islands are very vulnerable to climate change. Climate change-related impacts include coastal erosion, exacerbated water scarcity, sea-level rise, groundwater salination, fishery depletion, flooding, and an increase in vector-borne diseases. These impacts are likely to be amplified as climate change worsens (WHO, Citation2015/Citation2021).

The Fiji Ministry of Health (MoH) has an approved HNAP and undertook an integrated health V&A Assessment in 2015. At COP26 in 2021, Fiji committed to building climate-resilient and low carbon health systems and to achieve net zero by 2045. Accordingly, the Fijian MoH is integrating the health implications of climate change into its national strategy for climate change mitigation, increasing its capacity to assess and respond to climate sensitive diseases and developing technical capacities on climate change and health. Further action includes developing Early Warning Systems (EWS) for leptospirosis, typhoid and dengue, strengthening mosquito surveillance and enhancing climate finance mechanisms to support this work (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). Due to its involvement in the WHO/United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Global Pilot Project on Health Adaptation to Climate Change (2010–2015), Fiji has had a focus on strengthening surveillance systems of priority climate-sensitive diseases, developing climate-informed health EWS, V&A assessments, development of their HNAP and piloting climate-informed health interventions (WHO, Citation2015/Citation2021). Some 63 villages have been relocated from the coast due to sea level rise causing significant social disruption.

3.1.2. Papua New Guinea (PNG)

PNG is the largest country in the Pacific region occupying the eastern half of the island of New Guinea. PNG is a lower to a middle-income country with over 8 million culturally diverse and geographically dispersed people, and some of the most adverse health statistics in the Pacific. PNG is highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, including rising sea levels and warming trends and a heavy existing burden of vector-borne disease that will likely worsen if current climate projections eventuate (Imai et al., Citation2016).

In 2017, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) conducted a Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment in PNG, which did not comprehensively include health considerations of climate change (Asian Development Bank, Citation2017). There is no submitted NAP or HNAP on the UNFCCC NAPAs register (UNFCCC, Citation2022). PNG produced a National Climate Change and Health Action Plan (NCCHAP) between 2010 and 2012. The plan seeks to minimize the impact of climate change on health in PNG, considering mitigation through raising awareness of the impact of climate change on health, strengthening partnerships with other agencies, promoting and supporting knowledge production, and strengthening health systems to cope with health threats (WHO, Citation2015a).

3.1.3. Samoa

Samoa is a middle-income country, home to 195,000 people. Samoa consists of two main islands, Savaii and Upolu, plus several smaller, uninhabited islets. As a result of climate change, it is expected that Samoa will experience more extreme weather events, rising temperatures, ocean acidification, coral bleaching, and rising sea levels (WHO, Citation2015/Citation2021). Direct and indirect health effects of climate change in Samoa include water security and safety (including waterborne diseases), food security and safety (including malnutrition and foodborne disease), and vector-borne diseases. These burdens are expected to add pressure on the health system, in particular public health surveillance and response (WHO, Citation2015/Citation2021).

Samoa has a National Adaptation Plan for Action (NAPA) from 2005 that incorporates health to some degree, albeit this plan is very dated (UNDP, Citation2005). Samoa’s NAPA identified nine main areas, four of which are not sufficiently addressed by existing initiatives; health; agriculture and food security; ecosystem management; and early warning systems. The Integrated Climate Change Adaptation in Samoa (ICCAS) project received preliminary endorsement from the Global Environment Facility (GEF). This US$2 million project aims to implement health sector actions identified in Samoa’s NAPA, along with actions for early warning, agriculture, and ecosystem management (ICAS, Citation2019). In addition, Samoa has a Climate Change Adaptation Strategy for Health (2013–2014) that summarized priorities in terms of climate change health risks in Samoa. The strategy prioritizes mainstreaming climate change considerations into all Health Sector activities: strengthening community health education and health promotion programmes on food and WaSH; healthcare and hazardous waste management, vector control, breastfeeding and nutrition, and psychosocial support. The strategy seeks to strengthen communicable/non-communicable (NCD) disease surveillance and control, and to conduct research linking health and climate information (Grasso et al., Citation2014).

3.1.4. Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is a lower-middle-income country made up of 6 main islands and over 900 small islands located in the earthquake belt of the Pacific. The islands are home to 600,000 people, 80% of whom reside in low-lying coastal areas. Solomon Islands are vulnerable to cyclones, coastal erosion, groundwater salination, drought, and flooding that are often followed by water and food shortages. Earthquakes and tsunamis also threaten infrastructure, public health, and ecosystems. Climate change will bring temperature rise, sea level rise, ocean acidification and coral bleaching to the islands. The key climate change and health risks are NCDs, psychosocial disorders, respiratory illness, zoonosis, vector-borne disease, and food and water safety and quality issues leading to waterborne and foodborne disease and malnutrition (WHO, Citation2015/Citation2021).

Solomon Islands has a NAP from 2008 that includes a chapter on human health. This NAP determined, through a broad national consultative process, that agriculture, human settlements, water and sanitation, and human health are priority vulnerable sectors requiring urgent support to enhance resilience against the projected impacts of climate change (UNDP, Citation2008). The Solomon Islands NCCHAP identified their health risks as respiratory and vector-borne disease, water-borne diseases, malnutrition/food security, food-borne diseases, non-communicable diseases, and traumatic injuries and deaths (MoH Solomon Islands, WHO, Citation2011).

3.2. Health impacts

The findings are presented in a narrative synthesis focussing on key health impacts of climate change for the region and the four focus countries: extreme weather and climate events, heat-related illnesses, water security and safety, food and nutrition security and safety, vector-borne diseases, non-communicable diseases, mental health, and migration. We present case studies to illustrate in more depth the pathways between climate change and health in a particular setting.

3.2.1. Extreme weather events

Extreme weather events are expected to increase in severity and frequency in the Pacific region. Regionally, extremes of rainfall are correlated with the incidence of water-borne diseases (such as diarrhoeal disease, cholera, and typhoid fever) (McIver et al., Citation2016). Extreme events often damage or destroy health facilities, disrupting essential health services when they are needed most urgently (Kim et al., Citation2015).

In Fiji, associations were quantified between cyclones/floods & leptospirosis outbreaks (Lau et al., Citation2016). A strong relationship was demonstrated between extreme weather events, diarrhoeal disease, and dengue fever outbreaks (McIver et al., Citation2012). Flood risk is significant in Fiji with an extra 2000 people at risk due to climate change by 2030. Floods are a health hazard leading to drowning, injuries, food and water insecurity, infectious diseases (vector and water-borne), as well as displacement and mental ill health (WHO W, Citation2016).

In PNG, extreme climate events have occasionally led to the collapse of normal subsistence food production systems causing large-scale food shortages that threaten human health and survival. The Standardised Precipitation Index (SPI) have provided a useful warning for recent El Niño droughts and to a lesser extent, La Niña floods (Cobon et al., Citation2016). The short- and long-term effects of climate change on PNG’s agricultural sector impact population groups differently due to differing levels of vulnerability and resilience requiring location-specific responses (Gwatirisa et al., Citation2017).

Samoa is highly exposed to a range of natural hazards, the majority of which are climate-related and likely to increase in frequency and/or intensity with climate change, including floods, tropical cyclones, and storm surges. These events are associated with increased rates of mortality and injury, as well as increased rates of water and vector-borne diseases (Hashim & Hashim, Citation2016).

Solomon Islands are highly vulnerable to both hydrometeorological and geophysical hazards that include cyclones, floods, droughts, earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides, and volcanoes. The vulnerability may increase because of climate change. In the next 50 years, estimates show that the islands have a 50% chance of losing more than $240 million to natural hazard events and suffering more than 1600 casualties (GFDRR, Citation2017). From a health perspective, there is evidence that overcrowded evacuation centres during flooding events in Solomon Islands has increased the risk of transmission of vector-borne diseases (Shortus et al., Citation2016).

Case Study – Extreme Weather: El Nino and human health in the Pacific

El Nino-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a periodic variation in sea surface temperature and winds over the eastern Pacific Ocean that influences the tropic and sub-tropic climate. Occurring at 2–7 year intervals, ENSO is associated with droughts and floods in some geographical locations (Luo & Lau, Citation2020). While the relationships between ENSO and (extreme) weather are complex, strong links have been established between ENSO and extreme heat in the Pacific (Luo & Lau, Citation2020).

Accordingly, where and when ENSO-related weather patterns overlap with poor disease control, the risk of infectious disease transmission is elevated. This can occur with malaria, leptospirosis and other rodent-borne and vector-borne diseases associated with extreme weather events (Kovats, Citation2000).

Seasonal climate forecasts, predicting the likelihood of weather patterns several months in advance, can be used to provide early indicators of epidemic risk, particularly for malaria. A good example of this is the vector-borne disease control program, which, in partnership with Solomon Islands Meteorological Service developed a malaria monitoring and early warning system based on rainfall (the best predictor of malaria epidemics), temperature, and other environmental data. More of these types of interdisciplinary research and cooperation activities are required to reduce vulnerability to climate-sensitive vector-borne diseases in different PIC settings (COSPAC, Citation2014), due to the need to work with sectors outside of health (e.g. meteorological services, urban planning, water services).

3.2.2. Heat-related illness

Heatwaves are projcted to further increase in intensity and duration in the Pacific region. Heatwaves increase the risk of heat-related injuries, dehydration, and other fluid, electrolyte, and acid–base balance disorders particularly affecting people with underlying NCDs, including mental and behavioural disorders, nervous and circulatory system diseases, respiratory diseases, neoplasm, and renal diseases (Hashim & Hashim, Citation2016). NCDs already account for around 70–75% of all deaths in the Pacific Islands, so the effect of extreme heat on NCDs is particularly concerning. Diabetes is a particularly prevalent NCD in PICs and increased temperatures are likely to complicate pre-existing type 2 diabetes (Kjellstrom et al., Citation2010).

While Fiji does not experience heat waves like those experienced in many temperate countries, hotter days are expected to create conditions where people engage in less physical activity, which is associated with a rise in obesity; a risk factor for many NCDs (WHO MoH Fiji, Citation2013). In PNG, the average air temperature in Port Moresby is projected to increase by 0.7°C (under all greenhouse gas emissions scenarios) by the year 2030 (Lang et al., Citation2015). We did not identify any articles specifically examining extreme heat and health in Samoa or Solomon islands.

3.2.3. Water security and safety and climate change in the Pacific

The risk of water-borne disease in PICs generally increases with increases in temperature, rainfall extremes (drought and flood), and other natural hazards (World Health Organisation, Citation2015a). The atoll countries – Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Tuvalu, and Tokelau – are particularly susceptible to water insecurity from climate change because of their dependence on rainwater (World Health Organisation, Citation2015a). Further, there is a heavy burden of diarrheal disease in the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), particularly in children under five, and strong evidence linking diarrheal illness to weather and climate factors such as temperature, rainfall, ENSO cycles, and hydro-meteorological disasters in the Pacific region (McIver et al., Citation2016).

In Suva, Fiji, the relationship between monthly precipitation and childhood diarrhea is a typical ‘U-shape relationship’ whereby cases increase at extremes (very dry and very wet) (McIver et al., Citation2012). Anthropogenic alteration in land cover and hydrology influences typhoid transmission in Fiji (Jenkins et al., Citation2016). In PNG, extreme rainfall and flooding has been shown to affect infectious diseases. Diarrhoeal diseases, such as cholera and Shigella, increase after flooding events, which will likely occur in the coastal and estuary regions of PNG (Lang et al., Citation2015).

Water security in Samoa is extremely sensitive to climatic patterns. Issues with poor quality, scant availability, and difficult accessibility increase the risk of water-borne disease. Severe water shortages due to below-average rainfall are worsened by the sea-level rise that increases the risk of seawater intrusion into underground water aquifers as already experienced by many coastal communities (Grasso et al., Citation2014). In 2014, floods in Solomon Islands were associated with a nationwide epidemic of rotavirus diarrhea that spread to regions unaffected by flooding and caused >6000 cases and 27 deaths (Jones et al., Citation2016).

Case Study Water Security and Safety: Integrated Water Resource Management & WaSH in Health Care Facilities

PICs face unique challenges of increasing rainfall variability leading to drought and flooding, increasing temperatures, and likely higher than average sea-level rise, all of which negatively affect freshwater security. Adding to the challenge of WaSH provision are geographic and economic isolation and limited human and physical resources. PICs have some of the lowest water and sanitation coverage globally, with some countries showing stagnating or even declining access (in the case of piped water) to improved water and sanitation, compounding their vulnerability to climate change (WHO W, Citation2016). In PICs, there is a stronger case than ever for adopting a holistic system-based understanding – as promoted by Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) frameworks – to WaSH interventions so that they incorporate past and current challenges as well as future scenarios (Hadwen et al., Citation2015). IWRM is a process promoting the coordinated development and management of water, land, and related resources, to optimize economic and social welfare outcomes equitably, without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems. In the Western Pacific Region, less than 50% of healthcare facilities in rural or remote areas have access to basic WaSH services (WHO W, Citation2016). These challenges will likely be exacerbated with more drought and flooding. This compromises basic routine services such as maternal health, child delivery, and the prevention and control of infection (WHO, Citation2017).

3.2.3. Food and nutrition security and safety

In the Western Pacific Region, a combination of rising temperatures and variable rainfall patterns is expected to reduce crop yields, compromising food security and worsening undernutrition (Connell, Citation2015b). Agricultural production will also be adversely affected by the increased frequency and severity of cyclones, heat stress, and drought. The Pacific Community (SPC) projects a reduction in agricultural yield by 50% by 2059 (Georgeou et al., Citation2022). Malnutrition in all its forms, including obesity, undernutrition, and other dietary risks, is the leading cause of poor health globally (including in PICs). This phenomenon has been described as a global syndemic that will be amplified by climate change (Swinburn et al., Citation2019). Food security in the Pacific, especially in Micronesia, worsened in the past half-century in urban and rural communities and climate change will further hamper local food production (Campbell, Citation2015; Connell, Citation2015b). Agriculture, fishing, and local food production have declined, especially in peri-urban environments. Diets have incorporated more processed and imported foods, because of prestige, accessibility, cost, and convenience. This dietary transition has come at a financial, social, environmental, and nutritional cost to countries and households with increasing rates of NCDs (Connell, Citation2015a).

After Cyclone Pam (2015), up to 80% of local food production was lost in Vanuatu. Food security impacts in PICs are compounded by demographic change, geographical isolation, limited land area, poverty and a very high dependence on subsistence fishing and agriculture for livelihoods (Bell & Taylor, Citation2015).

In Fiji, the general trend of total rainfall shows that the islands are getting drier. Seasonality in child malnutrition (underweight, growth faltering, severe malnutrition, and anemia) results in higher rates in the wet/hot summer season. Extreme weather events (especially flooding) caused by La Nina can lead to shortages of fruits and vegetables, increasing food prices and exacerbating the prevalence of malnutrition (Cavuilati, Citation2018).

Samoa is vulnerable to food insecurity heightened by climate change due to declining smallholder participation in agriculture, a greater reliance on food imports, and wider dietary-based population health concerns such as obesity and diabetes (Underhill et al., Citation2017). In PNG, ciguatera fish poisoning is likely to increase with increasing sea surface temperature and reef disturbance, resulting in changes to diet and reduced protein intake with associated health problems (World Health Organisation, Citation2015a).

In Solomon Islands, population growth, declining agriculture, and fisheries productivity (influenced by climate and global environmental change), and global food trade contribute to a greater reliance on imported foods and contribute to malnutrition (Albert et al., Citation2020). Risks can be mitigated by improving nutrition-sensitive agriculture and fisheries to produce and distribute diverse, productive and nutrient-rich foods. National and regional policies can reduce the consumption of imported, energy-rich nutrient-poor foods (Albert et al., Citation2020).

Case Study Food and Nutrition Security: Vanuatu and Fiji

Climate change, NCDs, and malnutrition are three of the most significant health challenges facing PICs, and they share underlying drivers. In Vanuatu, promising groundwork has been laid for tackling the effects of climate change on food and nutrition security in policy and governance, coastal management, agriculture, and nutrition.

It is estimated that three-quarters of people in the Pacific live in rural areas and rely on agriculture and fisheries as livelihoods and to meet their immediate dietary needs (Medina Hidalgo et al., Citation2020). In Fiji, climate hazards and livelihood transitions have contributed to households becoming less reliant on local fisheries and agriculture for their dietary needs. Dietary diversity is low with most households routinely consuming only locally sourced food items from four food groups and diets are shifting towards energy-dense, nutrient-poor imported processed foods. There is an urgent need to increase the availability of locally produced fruits and vegetables and to diversify sustainable sources of animal protein. In addition, climate change adaptation strategies need to connect with changes to diets and food systems, to sustain livelihoods and improve the quality of life of rural communities (Medina Hidalgo et al., Citation2020).

3.2.4. Vector-borne diseases and climate change in the Pacific

The key climate-sensitive vector-borne diseases in PICs are malaria, dengue fever, leptospirosis, lymphatic filariasis, and rarer arboviruses such as Chikungunya and Zika (McIver et al., Citation2016; Spickett et al., Citation2013). Increased Zika spread (contributed to by climate variability) has been accompanied world-wide by a rise in cases of microcephaly and Guillain-Barre syndrome. An El Nino year could increase the number of favourable breeding sites for the mosquito that transmits Zika in PICs (Asad & Carpenter, Citation2018).

In Fiji, weather variables including rainfall, temperature, and humidity showed significant effects on variations of dengue cases, establishing the foundation for developing a climate-based early warning system for dengue. A more efficient disease surveillance system can be developed by combining the effects of weather variations on the number of dengue cases and routine surveillance (Tong, Citation2017).

PNG will likely see a higher incidence of dengue, chikungunya, filariasis and malaria, which may be the most sensitive to climate change as mosquitoes spread farther and to higher altitudes (Lang et al., Citation2015). PNG already has the highest rates of malaria in the Asia-Pacific Region. Local weather factors influence the incidence of vector-borne disease but effects vary depending on context, so disease control depends on location-specific responses (Imai et al., Citation2016).

In Solomon Islands, research supports the hypothesis that changes in seasonal rainfall (often associated with the ENSO) increase malaria transmission in subsequent malaria seasons. However, some flooding events have not been associated with malaria outbreaks in Solomon Islands (Alcayna et al., Citation2022; Natuzzi et al., Citation2016). Local epidemiology is the basis of a malaria early-warning system (EWS) implemented by Solomon Island Bureau of Meteorology and partners (Smith et al., Citation2017). The largest dengue outbreak recorded in Solomon Islands (2016–2017) led to research highlighting health systems issues and the limitations of a syndromic surveillance system that has not integrated climate data (Craig et al., Citation2018).

3.2.5. Mental health and climate change in the Pacific

Impacts on mental health and well-being are most likely in atoll communities affected by sea-level rise and those whose livelihoods are threatened by extreme weather and flooding (WHO, Citation2018). In Kiribati, climate change poses a threat to livelihoods, country sovereignty, and the national identity of inhabitants. This is further exacerbated because little is known about general mental health status in Kiribati, which makes it more difficult to understand the magnitude and nature of the impacts of climate change on mental health and wellbeing (McIver et al., Citation2014).

In Solomon Islands, rising sea levels are causing community disharmony, demonstrating that climate change can impact both individuals and communities by damaging social relationships and there is concern that relocation can increase the risk of ethnic conflict (Asugeni et al., Citation2015). A qualitative study describes high levels of fear and worry at the personal and community level (Asugeni et al., Citation2015).

Case Study: Mental Health

Climate change is anticipated to have significant negative effects on mental health, especially within populations simultaneously economically and ecologically vulnerable (Gibson et al., Citation2020). Early work identified three psychological syndromes associated with climate change: eco-anxiety, eco-paralysis, and solastalgia (Albrecht, Citation2011). A recent systematic review examined the mental health impacts of three types of climate-related events relevant to the Pacific: (1) acute events (i.e. hurricanes); (2) subacute or long-term changes (i.e. heat stress); and (3) the existential threat of long-lasting changes (i.e. sea level rise, permanently altered environments). The impacts represent direct (i.e. injury from storm surge) and indirect (i.e. forced migration, collective violence, economic loss) consequences of climate change (Palinkas & Wong, Citation2020). Of the limited literature on mental health impacts of climate change in the Pacific, most focus on impacts (rather than responses/adaptation) and call for more research (Asugeni et al., Citation2015). Few case studies present effective measures to prevent, mitigate, and manage the mental health impacts of climate change. The mental health impacts of climate-related migration have been recognised along with the importance of preserving socio-cultural and ecological ties, favouring community-led approaches and durable solutions, and revitalising traditional solidarity measures (Nayna Schwerdtle et al., Citation2020). A recent study in Tuvalu reinforces the call for decision-makers to consider mental health risks when considering climate-related risks and conceptualizing the costs of inaction (Gibson et al., Citation2020).

3.2.6. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) – beyond nutrition-related issues – and climate change in the Pacific

Given the high existing burden of NCDs in the Pacific, the exacerbating effects of climate change on NCDs are of particular concern (Savage & McIver, Citation2020; World Health Organisation, Citation2015a). A high prevalence of hypertension in PICs means that the salination of potable water through sea-level rise has significant health implications, by both increasing the risk of new cases of hypertension and exacerbating existing hypertension. This is a particular concern for maternal health (Khan et al., Citation2011); furthermore, ambient temperature could have a significant impact on hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases (Park et al., Citation2020).

In PNG, there is some indication that NCDs are on the rise (Lang et al., Citation2015); however, NCD prevalence and associated risk factors have not been well investigated in PNG (Lang et al., Citation2015). In Samoa, chronic disease risks are likely to increase with climate change and related increases in malnutrition, air pollution, and extreme weather events. There are negative impacts of climate change on cardiovascular and kidney diseases (NCDs), which are prevalent in Samoa (Kjellstrom et al., Citation2010) where hypertension is poorly controlled (Zhang et al., Citation2020), increasing the risks of complications. Climate change and poor blood pressure control increase the risk of mortality from NCDs. No recent, context-specific research on climate change and NCDs in the Solomon Islands was identified.

3.2.7. Migration, conflict, and climate change in the Pacific

Climate change influences existing drivers of migration; economic, social, demographic, and environmental, and will increasingly affect patterns of migration (Black et al., Citation2017; Pörtner et al., Citation2022; Watts et al., Citation2015). Climate change sharpens social and cultural issues of equity reflecting disparities in location, income, education, gender, health, and age. These inequities are made even more acute by increased levels of voluntary or forced migration within and beyond PIC boundaries (Weir et al., Citation2017).

Managed retreat in the South Pacific has disruptive health, economic and socio-cultural impacts on the communities that relocate including mental health, social networks, food security, water supply, sanitation, infectious diseases, injury, and health care access. Relocating may bring some positive changes such as improved living conditions as well as some challenges, such as impairment of subsistence livelihoods (Dannenberg et al., Citation2019; McMichael et al., Citation2019). In Fiji, the relocation and resettlement of communities to avoid slow-onset hazards is a challenge for communities and policymakers. Planned community relocation is most effective when they prioritize community participation and consultation (Lund, Citation2021).

Although climate-related migration can be adaptive (and reduce climate-related health risks), population displacement secondary to climate change (especially drought or flood) can mean people move into areas of increased or different climate and health risks (McMichael et al., Citation2003). In PNG, more people are congregating in a high-risk zone for storms and floods, but are less protected from them. Without adaptation responses (such as managed retreat and sea wall construction), people are not enabled to adapt in situ to mounting pressures, resulting in both ad hoc and planned out-migration responses (Luetz, Citation2018). In Samoa, 70% of the population and infrastructure are located in low-lying coastal areas. Population movements are influenced by a combination of economic, social, and environmental factors making it challenging to disentangle climate change from other drivers of migration (Flores-Palacios, Citation2015). In the Solomon Islands, rising sea levels are causing community disharmony with studies describing high levels of fear and worry at the personal and community level (Asugeni et al., Citation2015).

Case Study Migration: Managed Retreat

Managed retreat (planned relocation) is a proactive response sometimes considered in contexts where climate changes will render some communities uninhabitable. A managed retreat can have disruptive health, economic, social, and cultural impacts on relocated communities. Health impacts include mental health, food and water security, social capital, injury, infectious diseases, injury, and access to health care access. A recent review identified public health impacts and barriers to relocation and included Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, and the Solomon Islands. Most affected communities include Indigenous peoples who rely on agriculture and subsistence fishing. An evidence gap is research that directly addresses public health issues associated with relocation. While there were some positive outcomes reported, barriers to successful relocation include place attachment, inadequate funding, potential loss of livelihoods, a lack of suitable land identified, government processes, and community consensus. The review recommended further research on the health impacts of managed retreat to maintain community resilience (Dannenberg et al., Citation2019).

3.3. Potential responses to health impacts of climate change in the Pacific

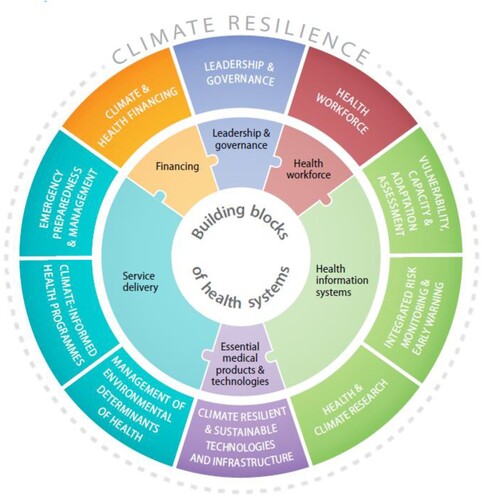

The ‘WHO Operational Framework for Climate Resilient Health Systems’ () is a tool that can be used by decision-makers to focus investments in climate-resilient health systems (World Health Organisation, Citation2015b). This framework adopts the building of health systems – leadership and governance, health workforce, health information systems, blocks essential medical products and technologies, service delivery and financing – and relates them to climate and health responses. By implementing the ten key components, health organizations, authorities, and programmes will be better able to anticipate, prevent, prepare for and manage climate-related health risks (World Health Organisation, Citation2015b). Health systems in the Pacific already undertake a multitude of activities to respond to health outcomes that are climate-sensitive; the issue here is to ensure that these systems can respond to the pressures that climate change will bring. Other strategic frameworks useful for health system strengthening include ‘The Western Pacific Framework for action on health and the environment’; the ‘Healthy Islands Vision’, including its specific application concerning climate change (McIver et al., Citation2017); and ‘The SIDS Initiative’ (Small Island Development States) that aims to provide national health authorities in SIDS with the political, technical and financial support to better understand and address the effects of climate change on health. It is important to note that SIDS is inclusive of PICs but will necessarily require close consultation with stakeholders to ensure their validity, complementarity with current/planned activities, contextual relevance, and specificity.

Figure 2. Ten components comprising the WHO Operational Framework for building climate-resilient health systems and the main connections to the building blocks of health systems (Source: WHO, Citation2015b).

The evidence-based intervention options presented – many of which align with the main regional/international frameworks – should support country-level planning processes.

The following section links the components of the framework with potential responses in the Pacific region.

Leadership and Governance:

Empower and support health leadership in PICs to engage nationally and internationally in climate and health (WHO W, Citation2018). For example, by supporting MoH staff members to participate in the UNFCCC delegation.

Support evidence generation and translation to build the business case for investment (WHO, Citation2018) and make scientific evidence easily accessible to the public through communications, advocacy, and social mobilization (WHO, Citation2017). For example, support the development of a resource repository or community of practice for climate change and health specifically for PICs.

Health workforce:

Build surge capacity in health facilities to cope with increasing demands related to climate change and demographic change. This may require a review of the number and type of health workers and their skill mix, followed by investment in recruitment, training, and continuing professional development. Out-migration of Health Care Workers (HCWs) is a global challenge, and in the Pacific this is aggravated by the low numbers being trained locally, especially in Melanesia.

Foster emerging, newly trained health professionals in the region to be climate and health champions.

VCA Assessment:

Support countries in their development of community-led HNAPs and identify relevant climate-resilient development pathways. Technical assistance may be required to conduct these HNAPs, however, they must remain country led. A variety of skill sets are required to conduct a VCA, which could be prioritized for country support. The skillset includes basic research skills such as literature reviews, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation, interviewing key stakeholders, triangulating different types of knowledge, developing policy recommendations, and stakeholder engagement.

Support PICs to implement VCAs (or H-NAPs). For example, by ensuring sufficient financial and human resources. Determine the enablers and barriers to VCA implementation (a research gap) and assist countries to follow through.

Support WHO efforts to develop climate change and health profiles, which are a practical tool for climate and health projects in PICs. Encourage the involvement of local stakeholders in the profile development and provision of local information (i.e. health data, meteorological data).

Integrated Risk Monitoring and Early Warning:

Consider qualitative, quantitative, interdisciplinary (epidemiology, meteorology), multi-sectorial (agriculture, WaSH), and traditional knowledge when developing integrated risk monitoring and early warning systems. Look for opportunities to learn from systems successfully applied elsewhere (Semenza et al., Citation2017). Consider emerging and re-emerging diseases and climate-sensitive diseases that pose future risks in a changing climate, such as Chikungunya and Zika.

Potentially large health gains in PICs will be achieved by basic health systems strengthening, including investments in weather/climate early warning systems (including health management information systems), capacity development of the health workforce, and WaSH programmes within health care facilities (WHO W, Citation2016).

Health and Climate research:

Develop a regional research agenda using a collaborative approach (government, NGO, research Institutions, community stakeholders) and coordinate across countries for maximum results. Refer to examples such as efforts to develop collective research agendas for cities and climate (Solecki et al., Citation2021) and climate change and conflict in Oceania (Boege, Citation2018).

Acknowledging precise research needs will vary by country and may require a national research agenda first. Consider research gaps particular to climate change and health in PICs such as the role of indoor/outdoor pollution on respiratory disease and the impact of climate change on mental health.

Involve policymakers in the development and review of research agendas and develop mechanisms for researchers to inform planning, policy, and stakeholder groups.

Evaluate the effectiveness of interventions to address the health impacts of climate change.

Climate Resilient and Sustainable Technologies and Infrastructure:

Conduct risk assessments of all healthcare facilities in terms of their vulnerability to climate change. The WHO Guidance for Climate Resilient and Environmentally Sustainable Health Care Facilities (WHO, Citation2020) provides support. Link health facilities with architects and organizations that have experience in risk reduction, retrofitting, and relocation.

Support healthcare facilities to reduce their climate impact. Ensure health facilities have access to safe water and sanitation.

Identify and support climate champions in health organizations and ensure facilities have environmental management plans and sustainability officers.

Establish networks to scale-up green healthcare facilities. A good example is the Clean and Green Hospitals Initiative, Thailand (Intraruangsri, Citation2018) and through new NGOs like The Climate Action Accelerator that have a health facilities pillar and aim to transition health facilities to be climate-resilient and environmentally sustainable at scale (The Climate Action Accelerator [Internet], Citation2022).

Stewardship of the environmental determinants of health:

Extend health-related policymaking beyond the health sector to agriculture, transport, housing, and energy ensuring Health in All Policies (HiAP). For example, include land-use planning, building, housing, water, and transport sectors in Disaster Risk Reduction activities.

Support the health sector to play a role at both policy and programme levels in providing evidence and raising awareness about the environmental determinants of health that are often beyond the control of the health sector.

Support government agencies to build capacity at national and community levels concerning water safety, food safety, and vector control.

Climate informed health programmes:

Support countries to develop processes to integrate policies and programmes within adaptation, DRR, and WaSH components. Beyond WaSH, consider investing in Integrated Water Resource Management.

Perform seasonal nutritional screening in vulnerable communities and scale up integrated food security, nutrition, and health programming in high-risk areas recognizing the gaps in knowledge about the relationship between climate and nutrition particularly in PNG, Samoa, and Solomon Islands.

Develop emergency preparedness plans for mental health patients (for example, community watch programmes during extreme weather conditions) and address the mental health needs of disaster and trauma-exposed populations.

Emergency Preparedness and Management:

Adopt a best-practice approach to building climate-resilient health facilities, including retrofitting existing facilities and building new facilities to withstand extreme weather events (and other natural disasters such as tsunamis, to which some PICs are particularly prone), according to the latest guidelines from WHO (WHO, Citation2020).

Acknowledge and mobilize community-based action to protect health during emergencies including community knowledge of local risks and vulnerable groups.

Utilize the WHO Emergency and Disaster Risk Management for Health (EDRH-H) Policy Framework for their recommendations for the effective management of risks to programmes and activities.

Climate and health financing:

Regular dissemination of potential financial resources and grant information and the creation of financing mechanisms to enable climate and health research, evidence translation, and community initiatives.

For consistency across national-level climate change policies in each PIC, evaluate whether investments are aligned with each PIC’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) concerning health.

4. Discussion

Understanding of the health impacts of climate change on PICs has increased substantially in the last decade. This review focused on the whole Pacific region, however there is still a need for further research, particularly within Micronesia. With the potential of additional financial support to strengthen the health sector’s resilience to climate change, it is important to clearly articulate the gaps and strengths of health system responses to date. There are many opportunities to build on the foundational work that countries have progressed while at the same time developing capacity and responding to contextual differences. This review has illustrated the many possible pathways for addressing health impacts, using the lens of the WHO Operational Framework for building climate-resilient health systems (World Health Organisation, Citation2015b). However, any responses developed require a full and respectful engagement process with each country and so the responses presented purely provide a snapshot of possible options.

Three broad areas where further and significant investment and support are needed are; (i) capacity development; (ii) surveillance and monitoring systems, and (iii) conduct research to address priorities and their translation into practice and policy.

First, concerning capacity development, there is a need to invest in the health workforce to ensure they are equipped with the competencies, tools and knowledge to develop environmentally sustainable and climate-resilient health systems. This includes integrating climate change and health learning objectives into all levels of health workforce curricula. It is important that health workers understand climate change and health risks and the strategies used to reduce those risks. Education and health ministries are vital to lead this work and share lessons learned. Training and awareness-raising are required in ministries of health and educational institutions at all levels and in community groups and the media (WHO, Citation2018).

Second, there is a need to significantly invest in and strengthen integrated surveillance systems that are connected to early warning responses in SIDs. This work overlaps with the strengthening of health information systems that are rarely computerized and often incomplete in SIDs, making it difficult to establish baselines and to understand health trends and impacts.

Third, there are nine areas for immediate research focus identified by this review. We have not attempted to rank these in terms of importance: that is for countries in the region to determine. But all these areas relate to both immediate and longer-term needs, and in each case, important work can be done with local resources, though comprehensive research programmes may require assistance from external sources.

Baseline mental health data. How climate change changes NCD prevalence, morbidity, and mortality patterns.

Synthesized evidence on the effectiveness of interventions to reduce heat-related mortality and morbidity.

Synthesized evidence of the effectiveness of interventions to improve food and nutrition security and food safety.

Climate-change and NCD pathways in PICs – other than the effect of extreme heat on existing NCDs

The economic cost of not addressing climate change, with reference to the health sector.

The relationship between malaria and other vector-borne disease and climate change specific to the Pacific.

The impact of climate change on vulnerable groups especially indigenous people, women and girls, people who have been displaced, and people living with disabilities. While much indigenous evidence is related to Australia and New Zealand, GESI is not captured well in the climate change and health literature in PICs.

Generally, a stronger research focus on gender, equity, and social inclusion in PICs is required

Climate-related movement of populations in PICs and effects on health.

The importance of implementation research to bridge the knowledge-action gap is widely acknowledged in global health (Theobald et al., Citation2018). This relates to strategic action 3 in the Western Pacific Framework for Action on Health and Environment on a changing planet: ‘evidence and communication; make scientific evidence easily accessible and available to the public through communication, advocacy, and social mobilization’. This covers the need to build support and create platforms for communication between scientists, the community, and governments to generate understanding and demand for environmental health initiatives (WHO, Citation2017). Despite the acknowledged importance of research translation, there is a lack of research funding and collaborative processes to support this.

Finally, the financing and governance of these potential responses are important to highlight. Health systems do not have the resources to make all the necessary adjustments to increase resilience to climate change (Ebi et al., Citation2016) so new financing is required in addition to the main funding mechanisms: Global Environment Facility, Kyoto Protocol Adaptation Fund, and UNFCCC Green Climate Fund. Financing health protection from climate change shouldn’t be considered a ‘niche’ or separate facility because at its core building the climate resilience of health care systems starts with first building on fundamental investments in the health sector, such as an adequate and trained health workforce and basic health infrastructure (Ebi & Otmani del Barrio, Citation2017).

On governance, strategic action 1 in the ‘Western Pacific Framework for Action on Health and Environment on a Changing Planet’ (WHO, Citation2017), has as the first of four strategic actions: ‘Enhancing governance and leadership for stronger environmental health capacity’. This action seeks to acknowledge the wide variance in institutional arrangements from country to country and makes a case to embolden national and local programmes to reach out beyond the traditional silos of environmental health (especially cities and municipal jurisdictions). PICs are at varying degrees of progress concerning their climate change and health actions, and it would be constructive to support collaborations across the region to share experiences and learning.

5. Conclusion

This research indicates that there is a small but growing knowledge base on the links between climate change and human health in the Pacific. This understanding, combined with the fundamental respect and acknowledgment of the intricate and intertwined links between human health and the natural environment in the Pacific, summed up by the concept of ‘Healthy Islands’ provides an important impetus for swift and collaborative action to progress climate-resilient development in PICs. There are synergies between climate change adaptation, health systems strengthening, and broader development issues within this frame of climate-resilient development, and it highlights the importance of viewing climate change and human health as an multisectoral issue. Short-term gains can be made by the development of HNAPs for each country, which can then direct support for country-led priorities. Despite the existence of many evidence gaps, the potential of multi-country and multi-donor partnerships to leverage this knowledge, funding, and learning exchanges across the region is an opportunity for PICs to seize. For example, currently, there are financing mechanisms available via the Global Environment Facility and the Green Climate Fund that could fund many of these areas identified for further support, although there is a need for technical support to progress proposals to these complicated financial mechanisms. PICs are showing incredible leadership on climate action and advocacy and have set ambitious targets (Gratzer Citation2019). A similarly rapid and strong global commitment to meet the diverse health challenges posed by climate change in the region is necessary for countries to reach their vision of ‘Healthy Islands’.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by Australia's Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) using Official Development Assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kathryn J. Bowen

Kathryn J. Bowen, a leading, internationally-recognised expert on the science and policy of sustainability (particularly climate change) and global health issues, with 20 years experience in original public health research, science assessment, capacity development and policy advice. I thrive on interdisciplinary, energetic and stimulating work environments where the emphasis is on implementing policy relevant and evidence-based sustainability programs. I am regularly commissioned by international bilateral and multilateral agencies (e.g. WHO, UNEP, UNDP, ADB, GIZ, DFAT) to co-design solutions for sustainable futures. I work to empower colleagues and decision makers and collaborate with diverse stakeholders to drive positive outcomes. My career highlight to date has been my nomination by the Australian Government to be a Lead Author on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Health Chapter. I have worked part-time since 2010 while balancing family responsibilities.

Kristie L. Ebi

Kristie L. Ebi, Ph.D., MPH is a Professor in the Center for Health and the Global Environment in the School of Public Health, University of Washington. She has been conducting research on the health risks of climate variability and change for more than 25 years. Her research focuses on estimating the current and future health risks of climate change; designing adaptation programs to reduce those risks; and quantifying the health co-benefits of mitigation policies. She has provided technical support to multiple countries and was a lead author for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 6th assessment cycle, including the special report on warming of 1.5°C and the human health chapter for Working Group II. Her scientific training includes an M.S. in toxicology and a Ph.D. and a Master of Public Health in epidemiology, and two years of postgraduate research at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. She edited fours books on aspects of climate change and has more than 250 peer-reviewed publications.

Alistair Woodward

Alistair Woodward is a public health doctor and epidemiologist and Professor in the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences at the University of Auckland. He is interested in preventable environmental causes of disease and injury, and has worked in Pacific island settings on climate hazards, water- and food-borne infections and respiratory illnesses. He has been a Lead and Coordinating Lead Author on many reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Lachlan McIver

Dr Lachlan McIver is a rural generalist and public health physician based in Switzerland, where he is the Tropical Diseases & Planetary Health Advisor at the Geneva headquarters of Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders). Lachlan is an adjunct Associate Professor at James Cook University in Australia and the founding director of the international non-profit organisation Rocketship Pacific Ltd, which is dedicated to improving health in Pacific island countries through stronger primary care. Among Lachlan's principal research interests is the health impacts of climate change, which was the topic of his PhD and has been the focus of his consultancy work for the World Health Organization across twenty countries over the last decade.

Collin Tukuitonga

Sir Collin Fonotau Tukuitonga KNZM is a Niuean-born New Zealand doctor, public health academic, public policy expert, and advocate for reducing health inequalities of Māori and Pasifika people. He has held several positions in public health and government in New Zealand and internationally. Collin is currently the Associate Dean Pacific at the University of Auckland in the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences.

Patricia Nayna Schwerdtle

Patricia Nayna Schwerdtle is a global public health academic specializing in climate change and health at the Heidelberg Institute of Global Health, Heidelberg University, Her research focusses on the nexus between climate change, migration, and health, education for sustainable health care, climate change and health in humanitarian settings, and climate change adaptation in health systems. She is on the steering committee of the 'CliMigHealth' international thematic network and an adjunct academic at Monash Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Science at Monash University.

References

- Albert, J., Bogard, J., Siota, F., McCarter, J., Diatalau, S., Maelaua, J., Brewer, T., & Andrew, N. (2020). Malnutrition in rural Solomon Islands: An analysis of the problem and its drivers. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 16(2), e12921. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12921.

- Albrecht, G. (2011). Chronic environmental change: Emerging ‘psychoterratic’ syndromes. In I. Weissbecker (eds.), Climate change and human well-being (pp. 43–56). Springer.

- Alcayna, T., Fletcher, I., Gibb, R., Tremblay, L., Funk, S., Rao, B., & Lowe, R. (2022). Climate-sensitive disease outbreaks in the aftermath of extreme climatic events: A scoping review. One Earth, 5(4), 336–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2022.03.011.

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Asad, H., & Carpenter, D. O. (2018). Effects of climate change on the spread of Zika virus: A public health threat. Reviews on Environmental Health, 33(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1515/reveh-2017-0042

- Asian Development Bank. (2017). Papua New Guinea: Building resilience to climate change in Papua New Guinea [Internet]. Retrieved November 16, 2021, from https://www.adb.org/projects/46495-002/main

- Asugeni, J., MacLaren, D., Massey, P. D., & Speare, R. (2015). Mental health issues from rising sea level in a remote coastal region of the Solomon Islands: Current and future. Australasian Psychiatry, 23(6_suppl), 22–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856215609767

- Bell, J., & Taylor, M. (2015). Building climate-resilient food systems for Pacific Islands. WorldFish.

- Berry, H. L., Waite, T. D., Dear, K. B., Capon, A. G., & Murray, V. (2018). The case for systems thinking about climate change and mental health. Nature Climate Change, 8(4), 282–290. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0102-4

- Black, R., Adger, N., Arnel, N., Dercon, S., Geddes, A., & Thomas, D. (2017). Foresight: Migration and global environmental change, final project report.

- Boege, V. (2018). Climate change and conflict in Oceania. Toda Peace Institute. Policy Brief, 17, 1–17.

- Campbell, J. R. (2015). Development, global change and traditional food security in Pacific Island countries. Regional Environmental Change, 15(7), 1313–1324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-014-0697-6

- Cavuilati, V. (2018). Climate change and human health: An ecological study on climate variability and malnutrition in Fiji.

- Charlton, K. E., Russell, J., Gorman, E., Hanich, Q., Delisle, A., Campbell, B., & Bell, J. (2016). Fish, food security and health in Pacific Island countries and territories: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2953-9

- Cobon, D. H., Ewai, M., Inape, K., & Bourke, R. M. (2016). Food shortages are associated with droughts, floods, frosts and ENSO in Papua New Guinea. Agricultural Systems, 145, 150–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2016.02.012

- Connell, J. (2015a). Food security in the island Pacific: Is Micronesia as far away as ever? Regional Environmental Change, 15(7), 1299–1311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-014-0696-7

- Connell, J. (2015b). Vulnerable islands: Climate change, tectonic change, and changing livelihoods in the Western Pacific. The Contemporary Pacific, 27(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1353/cp.2015.0014

- COSPAC. (2014). Malaria early warning system [Internet]. http://cosppac.bom.gov.au/products-and-services/malaria-early-warning-system/

- Craig, A. T., Joshua, C. A., Sio, A. R., Teobasi, B., Dofai, A., Dalipanda, T., Hardie, K., Kaldor, J., & Kolbe, A. (2018). Enhanced surveillance during a public health emergency in a resource-limited setting: experience from a large dengue outbreak in Solomon Islands, 2016-17. PloS one, 13(6), e0198487. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198487

- Dannenberg, A. L., Frumkin, H., Hess, J. J., & Ebi, K. L. (2019). Managed retreat as a strategy for climate change adaptation in small communities: Public health implications. Climatic Change, 153(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02382-0

- Ebi, K. L., & Otmani del Barrio, M. (2017). Lessons learned on health adaptation to climate variability and change: Experiences across Low- and middle-income countries. Environmental Health Perspectives, 125(6), 065001. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP405

- Ebi, K. L., Semenza, J. C., & Rocklöv, J. (2016). Misled about lead: An assessment of online public health education material from Australia’s lead mining and smelting towns. Environmental Health, 15(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-015-0085-9

- Flores-Palacios, X. (2015). Samoa: Local knowledge, climate change and population movements. Forced Migration Review, 49, 59. https://www.fmreview.org/climatechange-disasters/florespalacios

- Georgeou, N., Hawksley, C., Wali, N., Lountain, S., Rowe, E., West, C., & Barratt, L. (2022). Food security and small holder farming in Pacific Island countries and territories: A scoping review. PLOS Sustainability and Transformation, 1(4), e0000009. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pstr.0000009.

- GFDRR. (2017). The Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery: Annual Report [Internet]. https://www.gfdrr.org/en/ar2017

- Gibson, K., Barnett, J., Haslam, N., & Kaplan, I. (2020). The mental health impacts of climate change: Findings from a Pacific Island atoll nation. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 73, 102237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102237

- Grasso, M., Moneo, M., & Arena, M. (2014). Assessing social vulnerability to climate change in Samoa. Regional Environmental Change, 14(4), 1329–1341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-013-0570-z

- Gratzer, J. (2019). Saving the Pacific islands from extinction. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31722-2

- Gwatirisa, P. R., Pamphilon, B., & Mikhailovich, K. (2017). Coping with drought in rural Papua New Guinea: A western highlands case study. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 56(5), 393–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2017.1352504

- Hadwen, W. L., Powell, B., MacDonald, M. C., Elliott, M., Chan, T., Gernjak, W., & Aalbersberg, W. G. L. (2015). Putting WASH in the water cycle: Climate change, water resources and the future of water, sanitation and hygiene challenges in Pacific Island Countries. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 5(2), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2015.133.

- Haines, A., & Ebi, K. (2019). The imperative for climate action to protect health. New England Journal of Medicine, 380(3), 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1807873

- Hashim, J. H., & Hashim, Z. (2016). Climate change, extreme weather events, and human health implications in the Asia Pacific region. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 28(2_suppl), 8S–14S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539515599030

- ICAS. (2019). Integrated climate change adaptation Samoa [Internet]. Retrieved November 16, 2021, from http://www.adaptationlearning.net/project/integrated-climate-change-adaptation-samoa-iccas

- Imai, C., Cheong, H. K., Kim, H., Honda, Y., Eum, J. H., Kim, C. T., Kim, J. S., Kim, Y., Behera, S. K., Hassan, M. N., Nealon, J., Chung, H., & Hashizume, M. (2016). Associations between malaria and local and global climate variability in five regions in Papua New Guinea. Tropical Medicine and Health, 44(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-016-0021-x.

- Intraruangsri, J. (2018). The evolution of Green Hospital concept for Thailand’s Hospital.

- IPCC. (2022). Summary for policymakers. In Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Jenkins, A. P., Jupiter, S., Mueller, U., Jenney, A., Vosaki, G., Rosa, V., Naucukidi, A., Mulholland, K., Strugnell, R., Kama, M., & Horwitz, P. (2016). Health at the sub-catchment scale: Typhoid and its environmental determinants in Central Division, Fiji. EcoHealth, 13(4), 633–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-016-1152-6.

- Johnson, S. M., & Watson, J. R. (2021). Novel environmental conditions due to climate change in the world’s largest marine protected areas. One Earth, 4(11), 1625–1634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.10.016

- Jones, F. K., Ko, A. I., Becha, C., Joshua, C., Musto, J., Thomas, S., Ronsse, A., Kirkwood, C. D., Sio, A., Aumua, A., & Nilles, E. J. (2016). Increased rotavirus prevalence in diarrheal outbreak precipitated by localized flooding, Solomon Islands, 2014. Emerging Infectious Diseases., 22(5), 875–879. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2205.151743.

- Khan, A. E., Ireson, A., Kovats, S., Mojumder, S. K., Khusru, A., Rahman, A., & Vineis, P. (2011). Drinking water salinity and maternal health in coastal Bangladesh: implications of climate change. Environmental Health Perspectives, 119(9), 1328–1332. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1002804

- Kim, R., Costello, A., & Campbell-Lendrum, D. (2015). Climate change and health in Pacific Island states.

- Kjellstrom, T., Butler, A. J., Lucas, R. M., & Bonita, R. (2010). Public health impact of global heating due to climate change: Potential effects on chronic non-communicable diseases. International Journal of Public Health, 55(2), 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-0090-2

- Kovats, R. S. (2000). El Niño and human health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 78, 1127–1135.

- Lang, A. L., Omena, M., Abdad, M. Y., & Ford, R. L. (2015). Climate change in Papua New Guinea: Impact on disease dynamics.

- Lau, C. L., Watson, C. H., Lowry, J. H., David, M. C., Craig, S. B., Wynwood, S. J., Kama, M., & Nilles, E. J. 2016. Human leptospirosis infection in Fiji: An eco-epidemiological approach to identifying risk factors and environmental drivers for transmission. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004405

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Luetz, J. (2018). “We’re not refugees, we’ll stay here until we die!”—climate change adaptation and migration experiences gathered from the Tulun and Nissan Atolls of bougainville, Papua New Guinea. In Climate Change impacts and adaptation strategies for coastal communities (pp. 3–29). Springer.

- Lund, D. (2021). Navigating slow-onset risks through foresight and flexibility in Fiji: Emerging recommendations for the planned relocation of climate-vulnerable communities. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 50, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.12.004

- Luo, M., & Lau, N. C. (2020). Summer heat extremes in northern continents linked to developing ENSO events. Environmental Research Letters, 15(7), 074042. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab7d07

- Matheson, D., Park, K., & Soakai, T. S. (2017). Pacific island health inequities forecast to grow unless profound changes are made to health systems in the region. Australian Health Review, 41(5), 590–598. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH16065

- McIver, L., Bowen, K., Hanna, E., & Iddings, S. (2017). A ‘Healthy Islands’ framework for climate change in the Pacific. Health Promotion International, 32(3), 549–557. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dav094

- McIver, L., Kim, R., Woodward, A., Hales, S., Spickett, J., Katscherian, D., Hashizume, M., Honda, Y., Kim, H., Iddings, S., Naicker, J., Bambrick, H., McMichael, A. J., & Ebi, K. L. (2016). Health impacts of climate change in Pacific Island countries: A regional assessment of vulnerabilities and adaptation priorities. Environmental Health Perspectives, 124(11), 1707–1714. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1509756.

- McIver, L., Naicker, J., Hales, S., Singh, S., & Dawainavesi, A. (2012). Climate change and health in Fiji: Environmental epidemiology of infectious diseases and potential for climate-based early warning systems. Fiji Journal of Public Health, 1, 7–13.

- McIver, L., Woodward, A., Davies, S., Tibwe, T., & Iddings, S. (2014). Assessment of the health impacts of climate change in Kiribati. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(5), 5224–5240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110505224

- McMichael, A. J., Campbell-Lendrum, D. H., Corvalán, C. F., Ebi, K. L., Githeko, A. K., Scheraga, J. D., & Woodward, A. (2003). Climate change and human health: Risks and responses. World Health Organization.

- McMichael, C., Katonivualiku, M., & Powell, T. (2019). Planned relocation and everyday agency in low-lying coastal villages in Fiji. The Geographical Journal, 185(3), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12312

- Medina Hidalgo, D., Witten, I., Nunn, P. D., Burkhart, S., Bogard, J. R., Beazley, H., & Herrero, M. (2020). Sustaining healthy diets in times of change: Linking climate hazards, food systems and nutrition security in rural communities of the Fiji Islands. Regional Environmental Change, 20(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01653-2.

- MoH Solomon Islands, WHO. (2011). Health Impacts of Climate Change in the Solomon Islands: An assessment and adaptation action plan.

- Natuzzi, E. S., Joshua, C., Shortus, M., Reubin, R., Dalipanda, T., Ferran, K., Dalipanda, T., Reubin, R., Shortus, M., & Brodine, S. (2016). Defining population health vulnerability following an extreme weather event in an urban pacific island environment: Honiara, Solomon Islands. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 95(2), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.16-0177.

- Nayna Schwerdtle, P., Stockemer, J., Bowen, K. J., Sauerborn, R., McMichael, C., & Danquah, I. (2020). A meta-synthesis of policy recommendations regarding human mobility in the context of climate change. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249342

- Nutbeam, D. (1996). Healthy Islands—a truly ecological model of health promotion.

- Pachauri, R. K., & Meyer, L. A. (2014). IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC (p. 151). Retrieved April 16, 2022, from https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

- Palinkas, L. A., & Wong, M. (2020). Global climate change and mental health. Current Opinion in Psychology, 32, 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.023

- Park, S., Kario, K., Chia, Y., Turana, Y., Chen, C., Buranakitjaroen, P., Nailes, J., Hoshide, S., Siddique, S., Sison, J., Soenarta, A. A., Sogunuru, G. P., Tay, J. C., Teo, B. W., Zhang, Y., Shin, J., Minh, H., Tomitani, N., Kabutoya, T., … Wang, J. (2020). The influence of the ambient temperature on blood pressure and how it will affect the epidemiology of hypertension in Asia. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 22(3), 438–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.13762.

- Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D. C., Poloczanska, E. S., Mintenbeck, K., Tignor, M., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., & Okem, A. (2022). Summary for policymakers. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Internet]. Cambridge University Press: IPCC. Retrieved April 16, 2022, from https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-ii/