ABSTRACT

Today, differences in popular music genres and practices can be attributed to different peoples and cultures of the world in much the same sense as the shared and varied degrees of personality cult traditions. In this respect, Nigeria ranks amongst others with a unique and demonstrable popular music and personality cult culture. Of the available literature, none addresses the relationship between popular music and personality cult in Nigeria. This article is the first to do so. Here, we go beyond a mere analysis of the attributes of an idolised persona in, say, Naira Marley to examining both the ideological and sociological determinants––of literacy, media representation, social class, musical taste, deviancy, and demographic differences––that broadly support Nigerian popular music and personality cult practices. Through synthesising various views of the concept of personality cult with quasi-ethnographic data from some devotees of the Marlian cult, this article provides a critical intervention into how such activities as listening, imitating, and idolising are constructed forms of hero-worship in the Nigerian pop music scene.

Introduction

On 18 June 2020, Gbenga Aruleba, who is a veteran Nigerian TV host and the chief news producer at Africa Independence Television (AIT), delivered a scathing rebuke of contemporary Nigerian Afrobashment artist Azeez Fashola (popularly known as Naira Marley):

He [Azeez Fashola] and his crew flew to Abuja; held an all-night concert at the Jabi mall car park. Azeez Fashola is not a relation of the hardworking, former governor of Lagos state [and] now minister of Works and Housing, Raji Fashola. No. This Azeez Fashola goes by the stage name … Naira Marley. Again, [he is] not related to the highly revered late reggae star, Bob Marley. He [Naira Marley] is known more for the very bad things: singing to propagate ‘yahoo-yahoo’ [internet fraud], Indian hemp, and other vices. He has been on the wrong side of the law severally [i.e. repeatedly]; charged to court by the EFCC [Economic and Financial Crimes Commission] for some misconducts. We really need to cage this boy whose ideology is already sending the youth in the wrong direction. His followers (mostly students) who identify themselves as ‘Marlians’ are deviants and do everything to disobey laid-down rules and regulations, including … practices of not wearing pants, belts, and bras! … How did he get a private jet to fly him and his crew from Lagos to Abuja and back when the airspace is supposedly closed to commercial flights [during this Covid-19 lockdown], and special flights can only take place on the express authorization of the minister of aviation? Who authorized Naira Marley’s flight … or do we have followers of Naira Marley in this government? I mean, are there Marlians in the Buhari government?Footnote1

The words ‘Are there Marlians in the Buhari government?’ are thought-provoking and have rightly informed the title of our article. Aruleba’s question invites a critique of many things, including the nature of and elements that drive the followership and idolisation of some Nigerian popular musicians. Postcolonial Nigeria has produced many exciting and influential popular music icons, from the legendary Fela Anikulapo-Kuti to TuFace. The cult of Fela, for instance, was palpable and pervasive, especially during Nigeria’s government clampdown that led to his detentions and subsequent disruptions of his music productions and career in the 1970s.Footnote2 Unlike the overt promotion of deviancy that is both reportedly and arguably associated with Naira Marley, Fela drew a global cult following as a fearless musician cum sociopolitical activist who pursued social justice, equity and rule of law. Like the devotees of Naira Marley, Fela’s aficionados of the famous Kalakuta Republic exhibited an inexplicable subcultural allegiance to the Afrobeat icon, which made him appear god-like.

That said, our choice of Naira Marley is deliberate, in part because no other contemporary and living Nigerian popular musician has attracted so much condemnation and devout followership for his on-/off-stage idiosyncrasies in recent memory. Naira Marley is a Nigerian-based Afrobashment musician (discussed later). Afrobashment is a pop music genre that originated among the Black British diaspora in the mid 2010s with influences from British rap, funk, dancehall and West African Afropop music (Hancox Citation2017, Adegoke Citation2018). The controversy surrounding Naira Marley’s music is the notion that it promotes internet fraud/scam, drug abuse and an immoral lifestyle among a teeming Nigerian youth population. Since his rise to stardom in 2017, Naira Marley has attracted an overwhelming number of (youthful) devotees who go by the label ‘Marlians’. The Marlian cult is essentially a network of local and diasporic fans of Naira Marley. Like the cult of Prince, Michael Jackson, Beyoncé, and Fela, ‘Marlianism’ is both a movement and an ideology that exemplifies a ‘common form of popular or implicit religion’ (Till Citation2010a, p. 7) where a huge number of followers idolise Naira Marley’s enigmatic persona and authority.

Some scholars have argued that cult formations in music generally exemplify connotations of ‘religious zealotry’ that are common to popular music fandom and communities (see Jenkins Citation2005). Contemporary popular music consumption patterns in the digital age broadly generate and support a context that is akin to religious practices wherein (young) people form and perform their identities, advance their worldviews, and create satisfying customs of communal engagement (Sylvan Citation2002). The creation of enabling principles and customs of such communal engagements often rely on and is reinforced by a central and deified figure from among the people. As such, popular music cults are ‘usually focused around one individual figure or a group of figures who are treated as being special or more important than anyone else and are often worshipped as though they were divine’ (Till Citation2010a, p. 7). Celebrity adulation thus emanates from constant ‘maintenance of a fan base, performed intimacy, authenticity and access, and construction of a consumable persona’ (Marwick and Boyd Citation2011, p. 140). It is also a postmodern popular culture phenomenon which straddles sports, film and popular music industries. In sports, for example, respective fans of such football icons as Christiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi have often demonstrated their unapologetic loyalty (i.e. emotivism) to each player as though they possess some supernatural prowess. Although pockets of celebrity following abound for some actors and actresses in Nigerian cinema, contemporary Nigerian popular music icons such as Naira Marley, Davido, and Wizkid arguably dominate and account for a higher and active number of personality cults. Consequently, studying a fan culture such as the Marlian cult allows us to understand key mechanisms through which Nigeria’s own cultural, political and social realities, and identities interact with what Gray et al. (Citation2007) refer to as ‘the mediated world’.

This article specifically explores the role of Naira Marley’s music and his ‘personality’ in relation to the Marlian cult. Our interest in this study is inspired by the notion that research on and around Nigeria’s pop-cultural fan practices is overdue, especially following a perceived tendency to keep the scholarship on the country’s pop music industries ‘measured’ by focusing rather disproportionately on (pre-)selected artists and their songs for thematic and content analysis only. In Reflections on Nigerian musical arts and culture, Sylvanus (Citation2020a) notes that Nigerian music ‘has its own culturally specific, non-categorical and linguistically marked geography’ and hence ‘possesses and dispenses cultural authority’ (p. 1). By extension, we contend that Nigerian celebrity and popular music fan cultures reify such remarks through the subcultural ideologies that give them their unique attributes. To be clear, we are not suggesting that Marlianism as a study requires or necessarily deserves canonisation; however, we intentionally address it as a manifestation of the sustained and fascinating instance of contemporary fan culture and hero-worship in Sub-Saharan Africa. The current study not only adds to existing insights about the structure and construction of fan bases and practices, not least, of such globally recognised icons as Michael Jackson, Lady Gaga, and Beyoncé, but also and more so informs how the cult of Naira Marley shapes and is in turn shaped by Nigerian popular culture and music industries. Here, we go beyond a mere analysis of the attributes of an idolised persona in Naira Marley to examining both the ideological and sociological determinants––of literacy, media representation, social class, musical taste, deviancy, and demographic differences––that broadly support Nigerian popular music and personality cult practices.

Broadly, the extant and burgeoning literature on contemporary Nigerian popular music covers many aspects from context (Oyeleye and Gbadegesin Citation2020, Sylvanus Citation2020b) to artist careers (Veal Citation2000, Adegoju Citation2009, Forchu Citation2015), multimedia and copyright (Onyeji Citation2005, Sylvanus Citation2018, Onanuga Citation2020, Onyekwelu Citation2020), conflict and protest (Titus Citation2017, Akingbe and Onanuga Citation2020), women and sexism (Oikelome Citation2013, Onogu and Damian Citation2015, Eze Citation2020, Onanuga and Onanuga Citation2020, Popoola Citation2020), language (Adedeji Citation2014, Forchu Citation2020), genre and styles (Sylvanus Citation2013, Onwuegbuna Citation2016, Emielu and Donkor Citation2019, Adeniyi Citation2020), identity issues (Gbogi Citation2016), politics and race relations (Shonekan Citation2011), and performance (Osiebe Citation2020). The current article is, however, the first to discuss personality cult formation, dissemination, and sustenance in contemporary Nigerian popular music culture. Specifically, much of local mainstream media depiction is that Marlians exude a lot of emotivism (i.e. uncritical loyalty) towards Naira Marley. This notion follows from perceived mimetic efforts by Marlians to seek and appropriate Naira Marley’s messages and image. While this kind of disparaging media portrayal is not new and unique to Nigerian pop music fans (see for example, Hills Citation2007), our study reveals that Marlians possess and demonstrate some capacity for self-identity and the dynamics of emotivism. The need for Marlians to be different reflects aspects of fan cultures and ideologies because without a sense of distinction between them and other types of fans within and beyond Nigeria, they become more or less what John Fiske describes as ‘normal popular audiences’ (Fiske Citation1992).

For this reason, an understanding of Marlianism as object, ideology, and narrative opens up the space to balance criticisms of Marlians as stereotype fans. And so, the question ‘Are there Marlians in the Buhari government?’ is only rhetorical because our point is that Marlianism is neither wholly positive nor negative. Within the current article, the conversation affords us an opportunity to negotiate this embedded polysemy that encourages Naira Marley fans to celebrate their idol and moments, while simultaneously remaining open to stereotyped and derogatory readings/remarks from both the local press and non-Marlians. In other words, this article examines the subcultural ideology that supports Marlians as they work to generate what Mark Jancovich describes elsewhere as ‘a sense of identity through their supposed difference from the mainstream’ (Jancovich Citation2002, p. 1).

In terms of the methodology, we have relied on a combination of approaches, including in-depth textual analyses with synthesis of data sourced from song-texts, audiovisual and multimedia messages/domains, the review of related literature, as well as close observations and readings of the behavioural patterns that Naira Marley fans exude. Specifically, about twenty persons who identified as Marlians were interviewed (both in-person and remotely) in parts of Ajegunle, Lagos and Nsukka, Enugu state, Nigeria. During the fieldwork, one of the authors wore a hairstyle similar to Naira Marley’s while the other dressed up in the singer’s branded T-shirts. Our appearance particularly made the effort to blend in with and elicit favourable and honest responses from Marlians seamless. Responses from the interviewees offered both a personalised and first-hand understanding of the socio-political, cultural, and economic underpinnings that strengthen the cult of Naira Marley in Nigeria. Broadly, the respondents were asked to describe who and what Naira Marley is to them, as well as say why they love his music and try to emulate his controversial lifestyle. Before examining the manner in which the image of Naira Marley itself has been constructed, portrayed to and, ultimately, promoted by his devotees, it is necessary to foreground thoughts on personality cult.

Some thoughts on personality cult

Across various disciplines, scholars have explored and discussed the concept of personality cult from several hypothetical and research perspectives, including the historical (e.g. Dogan Citation2007, Adebanwi Citation2008), political religion (Pinto and Larsen Citation2006), spiritual ideology (Stout Citation2003, Partridge Citation2005, Lynch Citation2006), and mass media (Speier Citation1977, Lu and Soboleva Citation2014). Accordingly, definitions of personality cult vary subtly from scholar to scholar and from one discipline to another. Whereas art historian Anita Pisch posits that the ‘production of propaganda for the masses is a defining component’ of personality cult phenomenon (Citation2016, p. 50), political scientist Pao-min Chang (cited in Taylor Citation2006, p. 96) suggests that personality cult refers to ‘the artificial elevation of the status and authority of one man [or woman] … through the deliberate creation, projection and propagation of a godlike image’ (our emphasis). As secularised forms of religious rituals, historian Arpad von Klimo maintains that personality cult is the ‘sum of symbolic actions [or inactions] and texts which express and ritualize the particular meanings ascribed to a particular person in order to incorporate an imagined community’ (Citation2004, p. 47, our emphasis).

Over the years, personality cults have manifested in nearly all forms of public and popular cultures and fields of human endeavour (Hollander Citation2010). Our understanding is that the term ‘cult’ derives from faith-based traditions and other quasi-religious proprietary artefacts or ways of idolisation that may be found in Africa and around the world. Although the nature and leadership of personality cults have shifted from political and religious figures and broadened out to include film and music stars, the attributes of devotees and how they participate in such cults have, notwithstanding, remained largely the same. Within the Nigerian music industries, participation in ritualised behaviours and interactions such as mode of dressing, language of communication, rules of engagement, and worldview, as well as the generation and acceptance of hype around an idolised persona like Naira Marley, conveys ‘faith’ in the objectives of the cult, as well as loyalty to the ‘personality’.

Exploring the features of personality cults almost always leads to a notion of political religion in which ‘secular ideology becomes a matter of faith and the citizenry a community of believers’ (Pisch Citation2016, p. 50). Thus, in establishing the cult of Naira Marley, the notion and production of propaganda using music, song text, video, and social media messaging for consumption by the masses and his fans in particular is broadly reflective of personality cult processes. Contemporary personality cults are thus conceivable and doable following the capacity to disseminate portrayals of the idolised persona (Pisch Citation2016), or ‘cult-head’ and cult products in a way that guarantees widespread acceptance (Lu and Soboleva Citation2014). The promotion of certain ideologies that elicit public interest, indignation, and controversy has sustained the iconic status of some popular musicians. Stars like America’s Prince relied on a mix of sexuality and religious (cross)references to guarantee controversy and larger media coverage (Till Citation2010b). Similarly, Naira Marley’s personality subsists in notions of sexuality and escapism, deviancy and other perceived antisocial activities and advocacies that focus on Nigeria: its cultures, norms, values, youth disenfranchisement, politics and economy.

Given the extent of followership of, media hype, and public opinion about Naira Marley and his music, we ask: how does Naira Marley maintain his cult following? What are the observable characteristics associated with members of the Marlian cult? Are there sociopolitical and economic factors that encourage the unrepentant devotion to and appreciation of Naira Marley’s music? Answers to these and other related queries are necessary for our understanding of what is more or less a living culture that is propagated through such constructed forms of hero-worship as community and cliquing, uncritical defence of the cult and its leader, collecting, listening to and memorising Naira Marley’s songs/song-texts, imitating his dance steps and dressing, as well as acting at his behest. In what follows, we present an exploration of Naira Marley as an agency of self and otherworldliness, the thematic preoccupations of his music and videos, the locale and attributes of his fans and fanbase, and the ideology of Marlianism within a socioeconomic, political, and cultural framework. We argue that Marlianism represents contemporary articulations of personality cult formation, signalling, and an authenticity previously unaccounted for in the literature of contemporary Nigerian popular music.

Naira Marley and his music

Naira Marley was born Azeez Fashola on 9 May 1994 in Agege, Lagos, Nigeria (). He is a singer and songwriter who is widely celebrated as the leader of the Marlian cult. As a teenager, Naira Marley relocated from Lagos, southwest Nigeria to Peckham, southeast London where his formative years in the music industries was nurtured. At age 20, his music career was given a boost with the release of the song Marry Juana (2014), which basically promotes the smoking of marijuana. He became popular among Nigerians in the homeland and diaspora following his collaboration with Olamide and Lil Kesh (both Nigerian Afropop artists) in the song Issa Goal (Citation2017). As a hit track, Issa Goal was fortuitously appropriated as the soundtrack of Nigeria’s football team and its supporters during the 2018 FIFA World Cup in Russia. Naira Marley’s popularity surged in 2019 following the hit single Am I A Yahoo Boy? This song stirred and divided public opinions about the merits and demerits of internet fraud activities in present-day Nigeria wherein many (educated) young citizens are painfully under/unemployed.

Figure 1. Screenshot of Naira Marley taken from the music video Tesumole (Citation2019).

Some writers have described Naira Marley as both an enigma and a controversial figure who has received extensive condemnation for his music’s supposed immoral contents (Akande Citation2019). Others suggest that Naira Marley is a phenomenal singer whose musical journey from Peckham in London to cult figure in Nigeria has made him just as iconic as the legendary Fela Kuti and Bob Marley (Njoku Citation2020). Naira Marley is venerated by his obsessive online and offline fans. As confirmation of his strong cult-like influence, here is a quote from a Nigerian pop music fan (cited in Osiebe Citation2019):

Naira Marley is not a Tuface, he is not a Wizkid, or a Burna Boy, or a Davido … But I admire how Naira Marley has been able to gather followers … I admire the influence and power. Take a look at Olamide who threatened Don Jazzy not to come to [Lagos] mainland; what happened? Olamide does not have access to the caliber of followers Naira Marley has. If Naira Marley should tell you not to come to Agege, you should be afraid of Agege.

In 2019, Naira Marley launched his own record label called Marlian Records, and was recognised by YouTube as Nigeria’s most viewed artist. Since 2017, he has released the following singles: Issa Goal (Citation2017), Japa (2018), Am I A Yahoo Boy? (Citation2019), Opotoyi (2019), Soapy (2019), Puta (Citation2019), Mafo (Citation2019), Tesumole (Citation2019), ‘Aye’ (2020) and As E Dey Go (2020). Of this list, three songs have been purposively selected and analysed to demonstrate those controversial themes that apparently regularly underpin and promote activities within the Marlian cult in Nigeria. The selected songs are: Mafo, Puta, and Am I A Yahoo Boy? These songs have enjoyed and continue to enjoy widespread airplay and popularity in the streets and on both traditional and digital platforms such as radio, TV, YouTube, Udux, Spotify, Audiomax, and Boomplay.

Themes of deviancy, drug abuse and sexualisation of women in Marley’s songs/song texts

Deviancy

Deviancy is a way of living that reflects contrasting attitudes and values to those accepted norms of a particular social system (discussed further in Bryant and Craig Citation2012). Naira Marley’s song titled ‘Am I A Yahoo Boy?’ is broadly condemned by some portion of the Nigerian public because it contains perceived deviant comments that arguably promote internet scam. In Nigeria, the term ‘Yahoo Boy’ refers to a young person (often a man) who engages in internet scam, advance fee fraud and/or credit card scam for their livelihood. ‘Yahoo-Yahoo’ is thus a term for the business of internet and internet related racketeering in Nigeria. Whereas the Nigerian government and some elite citizens openly disapprove of Naira Marley’s apparent support for internet fraud in this song, some scholars argue that internet fraud is a consequence of the endemic and systemic corruption inherent in Nigeria (Odugbemi Citation2019). In the below lyric excerpts, Naira Marley ‘prays’ to God to protect internet fraudsters in their daily hustle to make ends meet (original lyric is in Yoruba while our translation is in standard English).

Following the release of the song, Nigeria’s Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) levelled an eleven-count charge on Naira Marley, and the court ordered that he be detained for thirty-five days over alleged cybercrimes.

Drug abuse

The encouragement of substance abuse in Marley’s song Mafo (Citation2019) is largely considered a deviant act by many purists in Nigeria. In Mafo (lit. ‘Do not panic’), Naira Marley arguably endorses the abuse of tramadol. As a pain-relief drug that produces a psychoactive effect when overdosed on, many young Nigerians and drug addicts rely on tramadol to feel ‘high’. To curb the widespread abuse of tramadol, the Nigerian government banned its over-the-counter purchase. In a typical oppositional approach, Naira Marley would seemingly promote the abuse of Tramadol in the lyrics of Mafo (see a few excerpts and their direct English language translations below).

Mafo generated a lot of controversies as well as admiration from many, including those frustrated young citizens across the country. Here, we infer that their reactions were and are derived more from the intertextual than the direct meanings of the lyric. This echoes Toynbee’s (Citation2000, p. x) assumption that ‘musicians are exemplary agents who make a difference, in the shape of different songs, sounds and styles.’ Their music thus ‘carries the promise of transcendence of the ordinary’ and helps to create and sustain the cult-like following of devotees with shared aspirations and cultural identity. To both the idol and fan, meaning (whether implied or received) is a matter of critical negotiation, which, according to Roy Shuker (Citation2012, p. 318) emanates from the interface between artistic resourcefulness and a devotee’s response:

Stardom in popular music, as in other forms of popular culture, is as much about illusion and appeal to the fantasies of the audience, as it is about talent and creativity. Stars function as mythic constructs, playing a key role in their fans ability to construct meaning out of everyday life.

In other words, Shuker suggests that the fascination with popular music idols is not simply an issue of politics and economics, but also and even more so the daily complex interactions of cultural values, myths, space, and fan practices that coalesce to produce the artist’s idolised persona. So, when Naira Marley says ‘omo iyami, mo wa pelu e, mafo’, he is actually addressing that individual fan or Marlian who looks up to him for approval of such indulgence as drug use/abuse. Here, tramadol becomes only a symbolic reference to a conversation on and around substance use and abuse. The phrase ‘mo wa pelu e’ (lit. ‘I am with you’) is not only uplifting to the devotee, but also and more so mythically indicative of authority and empowerment – the kind that flows from a deified leader to loyal followers. It is almost as if Naira Marley is physically with the devotee and encouraging the act when he says ‘Ko si enyan be, jowo mafo’ (lit. ‘There’s nobody there [with you], please do not panic). This is an instance of Naira Marley’s cult-like persona and influence, which the devotees’ emotivism and ritual of adoration and obeisance guarantees.

Sexualisation of Women

Naira Marley’s sexualisation of women is evident in parts of the lyrics of Isheyen (2019) where he declares: mo fe ma je ishe yen, which intertextually translates as ‘I want to eat that butt’. Similarly, Marley sexualises the video vixens in the song Opotoyi (2019) where many of the women appear almost naked with emphasis on their butts. Sex sells; and music producers and marketers within the Nigerian entertainment industries concede that obscene images help to sell records (Endong Citation2016). Consequently, artists attract audiences and profit off of a peoples’ ‘sustained interest in the depiction of sexually explicit images’ (Endong Citation2016, p. 33). In the music video of Puta (Citation2019), Naira Marley presents women’s bodies as commodities for the sexual gratification of men (). The objectification of women in music videos is not new. Indeed, many global pop music icons such as Rihanna, Katy Perry, Miley Cyrus, Britney Spears, Lady Gaga, Drake, and Lil Wayne have employed it to effectively garner and grow their fanbases (discussed further in Level Citation2019).

Figure 2. Screenshot depicting the objectification of women from Puta (Citation2019).

‘Puta’ itself is the Spanish word for ‘whore’. In the chorus section, Naira Marley codeswitches as he says ‘Filia la puta’ (lit. ‘my friend, you are a whore’), and ‘Baby girl, you are puta’. In the song, Naira Marley is heard trying to absolve himself of any sexual misconduct and responsibility when he says ‘Se oti mu igbo yo ni; ol’osho, se ma l’oyun fun mi, what can fa?’ (lit. ‘Have you smoked marijuana? Why would a prostitute be pregnant for me? What is that?’). He says this while ripping apart the laboratory test results, which seemingly confirm that the girls are pregnant (). This statement and behaviour have layered meanings for his fans – one of which is to never accept responsibility for unwanted pregnancies. This notion apparently endorses sexual misconduct in a society where the perpetrators are ‘people who believe that sexual promiscuity is the new zeitgeist; the road to salvation’ (Cheeka Citation2020, p. 1).

As other scholars have noted, music videos are the core texts for promoting artists and their music (see for example, Goodwin Citation1992, and Frith Citation1996). Doing this usually requires an alignment of the music video’s imagery with the artist’s own brand and worldview. Popular music icons thus employ diverse multimedia techniques in their videos, clothing, fan clubs, and concerts, ‘weaving myth and fantasy into a hyper-real legend using press releases and media manipulation (Till Citation2010b, p. 70). In essence, music idols consciously articulate ways of sustaining their self-image using the power of music and multimedia. This is evident in the music of Michael Jackson (Hollander Citation2010) and Lady Gaga (Ferencz Citation2011, Shuker Citation2016). Taken together, themes of drug abuse, internet fraud and sexism in Naira Marley’s music have worked to attract audiences and devotees to Marlianism as well as sustain membership of the cult.

Naira Marley, Marlians, and Marlianism

The cult of Naira Marley, his followers (i.e. Marlians), and its ideology (i.e. Marlianism) is created and maintained primarily through contents of Naira Marley’s music videos and visual albums, concerts, performances and public appearances, as well as his social media accounts and website. Marlianism herein refers to both the active and inactive processes of creating a movement and the cult itself. Marlianism possesses its own ‘geography’, which is culturally specific, non-categorical and yet linguistically marked. Marlianism has both real and imagined people and characters, a past, present and a future, as well as a position thought on governance, politics, money, sex and gender, education, and civics – all of which aligns with Naira Marley’s outward public declarations, socioeconomic commitments to his fans, as well as his past and present musical career.

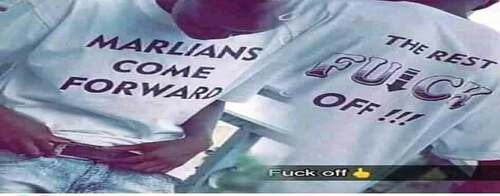

Naira Marley’s informal interaction with Marlians on social media platforms alters the conventional artist–fan relationship, and positions him as a fan of his fans. This implies that many devotees may never meet Naira Marley or have a close personal relationship with him. Nonetheless, what appears as a personal and even intimate relationship between Naira Marley and his devotees reinforces the notion that ‘present-day personality cults often develop without any personal contact between the devotee and the person venerated’ (Etnofoor Citation1999, p. 4). To facilitate that relationship, Marlians talk about Naira Marley and his live and recorded concerts, music videos and performances using terms like ‘mafo’ (‘do not panic’), ‘control’, ‘legwork’, and ‘weed’. These are metaphors that imply a complex affiliation between Naira Marley and his fans. At the beginning of the song Puta (Citation2019), Naira Marley declares: ‘Hey, control the crowd, control the crowd. Marlians come forward, the rest fuck off!’ Accordingly, the security guard is seen permitting Marlians (who appeared in the approved Marlian paraphernalia) to access the music icon while simultaneously turning back supposedly non-Marlians.

In terms of commodification, local textile companies have keyed into Marlianism as a franchise to produce Marlian T-shirts, bags, and other accessories with inscriptions using some of the cult’s own unique phrases (). The economics of these interactions confer a certain authenticity on Naira Marley, Marlians, and Marlianism. As a concept, authenticity, limpidity and intimacy remain widely discussed in celebrity studies. While discussing Beyoncé’s Instagram account, for example, Melissa Avdeeff (Citation2016, p. 109), argues that ‘it is widely accepted that those who engage with celebrities through social media expect a certain degree of authenticity in the form of transparency between the celebrity and their posts’. In relation to Naira Marley, this expectation extends to his music videos; and Marlians spontaneously search for the authentic or ‘truth’ in his image and what his music videos and lyrics project. In other words, they search for a connection between the ‘real’ Naira Marley, his lifestyle and ‘real’ feelings and worldview. This is what Dyer (Citation1986, p. 2) argues binds the whole notion of an idolised persona and their appeal: what they ‘really are’, their inner private self beyond their performances.

Although this search for the authentic Naira Marley is more or less utopian, as the living personification of the cult, he must continuously work to make himself appear genuine in a variety of ways, including weighing in on industry, socioeconomic, cultural and political issues often via social media platforms such as Twitter. This is vital, not least because ‘stars must also be seen as economic entities … effectively brands who mobilize audiences and promote the products of the music industry’ (Shuker Citation2012, p. 319). Consequently, the more intimate, personal and connected both Naira Marley and his devotees are, the more authentic Marlianism becomes. We are aware that ‘authenticity’ is a widely debated term in academia. However, it remains relevant to discussions of personality cults in popular music because of how the concept is actively constructed and employed by pop icons and their fans. This is so because ‘fandom, and the construction of stars and celebrities, has always involved the “search” for the “authentic” person that lies behind the manufactured mask of fame’ (Holmes and Redmond Citation2006, p. 4).

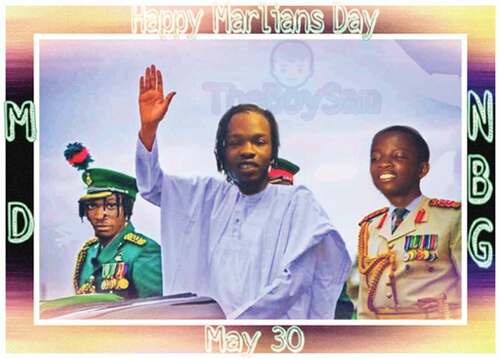

Thus, Naira Marley continuously works to make himself appear genuine by demonstrating his love and authenticity through some occasional cash and gifts ‘giveaways’ to his followers. In doing so, he convinces Marlians that he is not aloof of the socioeconomic frustrations brought on by a seemingly corrupt and uncaring national government. He essentially ‘feeds’ his flock. On 26 March 2020, Naira Marley tweeted: ‘The only thing that can make Nigerians happy is giveaways.’ The tweet received 11,000 ‘likes’ within a few minutes. That response is indicative of how Marlians appreciate their ‘president’ for his kindness – many of whom took to his twitter handle on 30 May 2020 to show solidarity for the Marlian Day celebrations. The adulation of music icons is a common practice in global hip hop/rap music subcultures where star artists are revered and addressed as queens and kings, including, for example, Nicki Minaj and Drake who are idolised as the ‘Queen’ and ‘King’ of rap, respectively. With reference to Naira Marley, one of the images from a twitter user <@theboysam> affirms that Marlians actually idolise him as their ‘President’ (). The picture, among other things, bears the acronyms MD (meaning ‘Marlian Dance’) and NBG (meaning ‘No Belt Gang’).

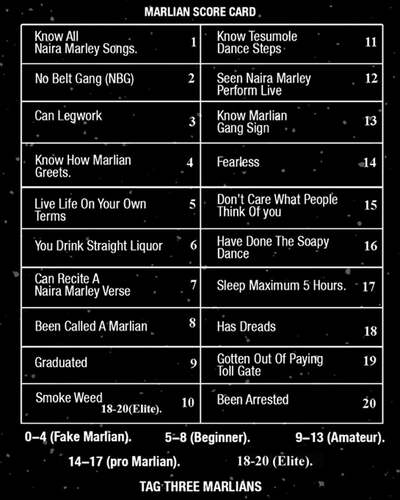

At the time of writing this article, there were 1.4 million followers of Naira Marley on Twitter, 3.4 million followers on Instagram, 365,000 subscribers on YouTube, and over 220,000 followers on his Facebook page. Whereas these figures are impressive for the consumption of content, they do not in themselves reveal who is actually a Marlian. To make that distinction, Naira Marley has recently categorised Marlians according to certain codes, features, and behavioural patterns. He calls this categorisation the ‘Marlian Score Card (MSC)’ ().

The MSC outlines five categories of Marlians, including ‘Fake’, ‘Beginner’, ‘Amateur’, ‘Pro’ and ‘Elite’ Marlians. The MSC itself reveals the microstructure of the Marlian cult and school of thought. As shown in the card, Fake Marlians (levels 1–4) are those who know all Naira Marley’s songs and greeting signs, wear no belts (No Belt Gang), and can ‘Legwork’. The legwork is a dance style that relies predominantly on the legs. It was popularised by another Afropop artist called Zlatan in his single titled Legwork (2019). Moving on, a Beginner Marlian (levels 5–8) is one who can do all things listed in the preceding levels and more, including reciting a verse from Naira Marley’s songs, the consumption of alcohol, live life on their own terms (i.e. be deviant), and is proud to be called a Marlian. These categorisations and labels are emblematic of esoteric cult practices wherein confirmed members validate (and are validated following) the stipulated principles. As an obligation, reciting any verse of Naira Marley’s songs, for example, affirms acceptance into the ‘community’ and confirms the devotee’s ‘Beginner’ status. This attribute is not only akin to stages of initiation and indoctrination into faith-based religious institutions, but also helps young adults develop alternative spiritual ideologies and identities (Partridge Citation2005, Lynch Citation2006).

In the ‘Amateur’ category (i.e. levels 9–13), the fans are university educated individuals who smoke marijuana (weed), do the Tesumole dance, attend Naira Marley’s live events, and understand the Marlian gang signs. Contrary to the notion that Marlians are mostly school drop-outs, this category clearly reveals Naira Marley’s acute awareness of the presence of college and university degree holders at his concerts. Finally, the ‘Pro’ and ‘Elite’ categories (i.e. levels 14–17 and 18–20, respectively) suggest an upper hierarchy of fearless, non-conformist devotees who, in addition to all other attributes of the preceding levels, do the Soapy dance, sleep for only five hours a day, wear dreadlocks like Naira Marley, defiantly evade federal and local taxes, and can show that they have been arrested by law enforcement agents at some point in their lives.

The MSC arguably underscores a praxis that subsists in constructed forms of hero-worship, which we admit is not coercive. As an affirmation of this Marlian praxis, one of the interviewees in Lagos said:

I like Naira Marley because he is a music star who understands our problems, and protests the failure of Nigerian government just like Fela did. His music is rhythmic, danceable and good to me. I love his music because unlike many other Nigerian hip hop stars, he has come out openly like Fela to say ‘govment na barawo’ [lit. the federal government steals from us]. And that is why they arrested him and they continue to drag him to court. I copy his lifestyle because he is real and it is the trending thing at the time, and we all must join him in disagreeing with the government to see if they can fix the economy for the common man. (personal communication, 20 July 2020)

This comment echoes thoughts that personal identification with popular music stars are significant aspects of iconic consumption and reception wherein consumers interpret the music ‘by looking for connections between the music and details of the personal lives of the individual artist and themselves’ (Loy et al. Citation2018, p. 7). Reactions from other respondents support the notion that Naira Marley is a music activist, and whose lifestyle should be imitated. They maintained that the issue of internet fraud, which inadvertently boosted Naira Marley’s popularity in Nigeria is not new. Indeed, such hit songs as Yahooze (Citation2007) by Olu Maintain, and Kelly Handsome’s Maga Don Pay (Citation2008) promoted the narrative of advance fee fraud before Naira Marley’s works. Enter a respondent in Nsukka who queried the government’s relentless witch-hunt of Naira Marley:

Why is the government after Naira Marley when many government officials keep on siphoning public funds in Nigeria? You see, Naira Marley is not Nigeria’s problem and the more the media raise [an] awareness to condemn Naira Marley’s music, the more the youth want to find out the details of the music. In that way, the media and the government are indirectly helping young people to appreciate Naira Marley more. I choose to dress like him every day so that I can belong. (personal communication, 22 July 2020)

By having his devotees reference his song texts, imitate his way of dressing, hairstyle, lifestyle, and use of language, Naira Marley establishes a hierarchy of expectations that guarantees the afterlife of the cult. In essence, Naira Marley and his production team endeavour to remain genuine, intimate, subjective, extemporaneous, and relevant while actively collating and organising tangible and intangible materials for the propagation and sustenance of Marlianism. This behaviour reifies Simon Frith’s (Citation1996) assertion regarding the various levels of characterisation and thematic preoccupation of pop songs, videos and performances:

There is, first of all, the character presented as the protagonist of the song, its singer and narrator, the implied person controlling the plot, with an attitude and tone of voice; but there may also be a ‘quoted’ character, the person whom the song is about … On top of this there is the character of the singer as star, what we know about them, or are led to believe about them through their packaging and publicity, and then, further, an understanding of the singer as a person, what we like to imagine they are really like, what is revealed, in the end, by their voice. (198–199, emphasis in original)

Naira Marley’s intentionality of order and relevance provokes interest in how the cult exploits the power of his music and media to re-articulate the lifestyle of a teeming population of Marley adherents who are daily beleaguered by poverty, hunger, unemployment and disease. As a solution, Naira Marley ostensibly offers his devotees the option of a counter-narrative: of deviancy and escapism, which subsists in drug abuse, sexism, fraud and so on. We should note that Marley’s counter-narrative is not unique to Nigeria alone. Indeed, we argue that these are a part of global hip hop and rap music subcultures which, as outlets, encourage both marginal and marginalised youth cultures to express their discontentment often through deviant lifestyles (see for example, Kotarba and Vannini Citation2009). Our exploration of Marlianism thus shows that both religion and the secular operate within and across very blurry and porous lines (Lynch Citation2006, Cohen Citation2016, Marsh and Vaughan Citation2017). In discussing the cult of Naira Marley, it would appear that the secular has borrowed much from the sacred:

Notwithstanding their secular content, personality cults are religious phenomena in the sense that they aim at rendering the world a meaningful place. What sets them apart is the stress on individuation. Just as a local saint, a hermit in a nearby cave, a spiritual leader or exemplary nun - who is ‘one of us’, and whose personal biography is known and recounted time and again - helps to endow abstract religious values with local or even personal significance, the activities, fantasies and emotions that constitute personality cults around secular figures may be read as attempts to bridge the experiential world of the individual devotee with some larger system of meaning. (Etnofoor Citation1999, p. 3)

Indeed, the devotee’s desire to individually (and perhaps collectively) identify with their popular music idol is a major aspect of the processes of personality cult formation, propagation, consumption, and approval. In the Marlian context, this process is fundamentally facilitated by the music and fan’s own derived interpretations, which the lyrics and groove of a genre like afrobashement provides. In other words, Marlians look for nexuses between the music and aspects of the personal lives of Naira Marley and themselves. In so doing, both the implied and received meanings combine to reinforce the perceived connection between the fan and their venerated idol. In Naira Marley’s music, for example, both meaning and personality essentially reside in the life of the artist. This notion and other overlapping aspects of human and material agency blur the boundaries of and distinction between what might arguably constitute fandoms and the cult of personality. What is special, however, about contemporary Nigerian popular music culture and the cult of personality subsists mainly in a unique socioeconomic, political, historical, lingual, aesthetical, and cultural location, which the devotees of the country’s music icons rely on to express their practical affirmation of an inevitable difference.

Given all of the above statements, we contend that Naira Marley is a significant subject for this study, not least for his influence, as well as commercial and artistic achievements. His capacity to build and sustain an idolised persona is a testament of talent, which is defined as ‘an innate predisposition to competence’ (McLeod and Herndon Citation1980, p. 188). At the outset, we stated that Marlianism represents contemporary articulations of personality cult formation, signalling, and an authenticity previously unaccounted for in the literature of contemporary Nigerian popular music. Like other contemporary Nigerian popular music icons, Naira Marley constructs an ‘authentic’ idolised image through sharing intimate details of his life via social media, Reality TV shows, radio and TV interviews, blogs, and music videos with his fans. Together with his devotees, their construction of Marlianism is extensive, widespread, complex, layered, controlled and consistent, and thus requires further scrutiny.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Emaeyak Peter Sylvanus

Emaeyak Peter Sylvanus is a senior lecturer at the Department of Music, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. He holds a PhD in music from City, University of London. His research focuses primarily on music in Nigerian cinema. As the pioneering scholar on Nollywood film music studies, Dr. Sylvanus has contributed several articles to mainstream journals in the arts, humanities and social sciences. He has three forthcoming chapters on music and comedy films, Nigerian pop music industries and memory, as well as women as composers in Nollywood with Palgrave Macmillan, Oxford University Press, and Lexington Books, respectively. Other projects include an extensive study of the interplay of popular music and personality cult, payday, and the liturgy in Nigeria.

Samson Uchenna Eze

Samson Uchenna Eze is a lecturer at the Department of Music, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. His research focuses on the connection between music and society, popular music, music performance and ethnomusicology. In a recent study with Professor Paul Basu of SOAS, University of London, he explored some of Northcote W. Thomas’s ethnographic folksongs recorded in southern Nigeria, 1910–1911. He has published on sexism and power play, as well as glocalization trends in contemporary Nigerian hip hop music and culture. He is currently exploring aspects of popular music and the question of morality in Nigeria.

Notes

1. Listen to it here, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1XvjlP2anNM&app=desktop.

2. Although many publications exist on the music and life of Fela, none addresses the notion of personality cult. See for example, Grass (Citation1986), Diala-Ogamba (Citation2007), Dosunmu (Citation2011), Adebayo (Citation2019), Osiebe (Citation2020).

References

- Adebanwi, W., 2008. The cult of Awo: the political life of a dead leader. The journal of modern African studies, 46 (3), 335–360. doi:10.1017/S0022278X08003339

- Adebayo, S., 2019. This uprising will bring out the beast in us: the cultural (after)life of ‘beasts of no nations’. Journal of African cultural studies. doi:10.1080/13696815.2019.1664284

- Adedeji, W., 2014. Negotiating globalization through hybridization: hip hop, language use and the creation of crossover culture in Nigerian popular music. Language in India, 14 (6), 497–515.

- Adegoju, A., 2009. The musician as archivist: an example of Nigeria’s Lagbaja. Itupanle: Online Journal of African Studies, 1, 1–23.

- Adegoke, Y. 2018. Grime, afro-bashment, drill … how Black British music became more fertile than ever. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2018/jun/01/grime-afro-bashment-drill-how-black-british-music-became-more-fertile-than-ever [Accessed 7 June 2020].

- Adeniyi, E., 2020. Nigerian afrobeats and religious stereotypes: pushing the boundaries of a music genre beyond the locus of libertinism. Contemporary music review, 39 (1), 59–90. doi:10.1080/07494467.2020.1753475

- Akande, S. 2019. Naira Marley might know exactly what he’s doing. Available from: https://www.zikoko.com/pop/naira-marley-ijo-soapy-menace/ [Accessed 13 June 2020].

- Akingbe, N. and Onanuga, P.A., 2020. Voicing protest’: performing cross-cultural revolt in Gambino’s ‘This is America’ and Falz’s ‘This is Nigeria. Contemporary music review, 39 (1), 6–36. doi:10.1080/07494467.2020.1753473

- Avdeeff, M., 2016. Beyoncé and social media: authenticity and the presentation of self. In: A. Trier-Bieniek, ed. The Beyoncé effect: essays on sexuality, race and feminism. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 109–123.

- Bryant, C.D. and Craig, F.J., 2012. The complexity of deviant lifestyles. Deviant behavior, 33 (7), 525–549. doi:10.1080/01639625.2011.636694

- Cheeka, D. 2020. Naira Marley: zeitgeist or poltergeist? Available from: http://www.lagosfilmsociety.org/2020/01/28/naira-marley-zeitgeist-or-poltergeist/ [Accessed 5 June 2020].

- Cohen, D.J., 2016. Rock as religion. Intermountain West journal of religious studies, 7 (1–3), 45–49.

- Diala-Ogamba, B., 2007. Music as social poetry: a critical evaluation of Fela Anikulapo Kuti’s afrobeat lyrics. The Langston Hughes review, 21, 30–38.

- Dogan, M., 2007. Comparing two charismatic leaders: Ataturk and de Gaulle. Comparative sociology, 6, 75–84. doi:10.1163/156913307X187405

- Dosunmu, O. 2011. Afrobeat, Fela and beyond: scenes, style and ideology. PhD diss. University of Pittsburgh.

- Dyer, R., 1986. Heavenly bodies: film stars and society. London: Macmillan Education.

- Emielu, A. and Donkor, G.T., 2019. Highlife music without alcohol? Interrogating the concept of gospel highlife in Ghana and Nigeria. Journal of the musical arts in Africa, 16 (1–2), 29–44. doi:10.2989/18121004.2019.1690205

- Endong, F.P.C., 2016. Illicit content in the Nigerian hip-hop: a probe into the credibility of music censorship in Nigeria. International journal of journalism and communication, 1 (2), 29–35.

- Etnofoor, S., 1999. Editorial: personality cults. Etnofoor, 12 (2), 3–5.

- Eze, U.S., 2020. Sexism and powerplay in the Nigerian contemporary hip hop culture: the music of Wizkid. Contemporary music review, 39 (1), 167–185. doi:10.1080/07494467.2020.1753479

- Ferencz, K. 2011. ‘I’m your biggest fan, I’ll follow you … ’ Lady Gaga, little monsters and the religious dimension of fandom in pop music. Unpublished Master’s diss. Brock University, St. Catharine’s, ON.

- Fiske, J., 1992. The cultural economy of fandom. In: L.A. Lewis, ed. The adoring audience: fan culture and popular media. London: Routledge, 30–49.

- Forchu, I.I., 2015. Nigerian hip hop musicians: professionals maligning the wing of the bird. Journal of the association of Nigerian musicologists, 9, 107–112.

- Forchu, I.I., 2020. Rhythmic idioms in Igbo hip hop music: the exemplar that is Phyno. Journal of the musical arts in Africa, 17 (1–2), 19–40. doi:10.2989/18121004.2020.1851458

- Frith, S., 1996. Performing rites: on the value of popular music. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Gbogi, M.T., 2016. Language, identity, and urban youth subculture: Nigerian hip hop music as an exemplar. Pragmatics, 26 (2), 171–195. doi:10.1075/prag.26.2.01tos

- Goodwin, A., 1992. Dancing in the distraction factory: music television and popular culture. Minnesota, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Grass, R., 1986. Fela Anikulapo-Kuti: the art of an afrobeat rebel. The drama review, 30 (1), 131–148. doi:10.2307/1145717

- Gray, J., Cornel, S., and Harrington, C.L., 2007. Fandom: identities and communities in a mediated world. New York: New York University Press.

- Hancox, D. 2017. London’s new cool: how UK afrobeats could take over the world. Available from: https://www.thenational.ae/arts-culture/london-s-new-cool-how-uk-afrobeats-could-take-over-the-world-1.69520 [Accessed 7 June 2020].

- Hills, M., 2007. Michael Jackson fans on trial? ‘Documenting’ emotivism and fandom in. Wacko about Jacko. Social semiotics, 17 (4), 459–477. doi:10.1080/10350330701637056

- Hollander, P., 2010. Michael Jackson, the celebrity cult, and popular culture. Culture and society, 47, 147–152.

- Holmes, S. and Redmond, S., 2006. Framing celebrity: new directions in celebrity culture. London: Routledge.

- Jancovich, M., 2002. Cult fictions: cult movies, subcultural capital and the production of cultural distinctions. Cultural Studies, 16 (2), 306–322. doi:10.1080/09502380110107607

- Jenkins, H., 2005. Textual poachers: television fans and participatory culture. New and London: Routledge.

- Klimo, A., et al., 2004. ‘A very modest man’: Béla Illés, or how to make a career through the leader cult. In: B. Apor, ed. The leader cult in communist dictatorships: Stalin and the Eastern Bloc. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 47–62.

- Kotarba, J.A. and Vannini, P., 2009. Understanding society through popular music. New York: Routledge.

- Level, R. 2019. Sex sells: how to get more girls, views and fans. Available from: https://www.smartrapper.com/sex-sells/ [Accessed 20 July 2020].

- Loy, S., et al., 2018. Popular music, stars and stardom: definitions, discourses and interpretations. In: S. Loy, ed. Popular music, stars and stardom. Acton, Australia: Australian National University Press, 1–20.

- Lu, X. and Soboleva, E. 2014. Personality cults in modern politics: cases from Russia and China. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin, Center for Global Politics, CGP Working Paper Series, 01/2014. Available from: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-441460 [Accessed 13 May 2020].

- Lynch, G., 2006. The role of popular music in the construction of alternative spiritual identities and ideologies. Journal for the scientific study of religion, 45 (4), 481–488. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2006.00322.x

- Marsh, C. and Vaughan, S.R., 2017. Religion and western popular music: reach out and touch faith? Modern believing, 58 (1), 17–27. doi:10.3828/mb.2017.3

- Marwick, A. and Boyd, D., 2011. To see and be seen: celebrity practice on twitter. Convergence: the international journal of research into new media technologies, 17 (2), 139–158. doi:10.1177/1354856510394539

- McLeod, N. and Herndon, M., 1980. Conclusion. In: N. McLeod and M. Herndon, eds. The ethnography of musical performance. Norwood, PA: Norwood Editions, 176–199.

- Njoku, B., 2020. Nigeria: Naira Marley soaring amidst controversies. Available from: https://www.vanguardngr.com/2020/02/naira-marley-soaring-amidst-controversies/ [Accessed 14 June 2020].

- Odugbemi, G., 2019. Naira Marley versus economic and financial crimes commission: the extent of freedom of expression in Nigeria, and the EFCC’s inefficiencies–a legal opinion. Available from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3389976 [Accessed 4 March 2020].

- Oikelome, O.A., 2013. Are real women just bad porn? Women in Nigerian hip-hop culture. Journal of Pan African Studies, 5 (9), 83–98.

- Onanuga, A.P., 2020. When hip-hop meets CMC: digital discourse in Nigerian hip-hop. Continuum, 34 (4), 590–600. doi:10.1080/10304312.2020.1757038

- Onanuga, A.P. and Onanuga, O.A., 2020. Violence, sexuality and youth linguistic behavior: an exploration of contemporary Nigerian youth music. Contemporary music review, 39 (1), 137–166. doi:10.1080/07494467.2020.1753478

- Onogu, W. and Damian, A., 2015. Contemporary music and dance in Nigeria: morality question. Research on humanities and social sciences, 5 (20), 82–90.

- Onwuegbuna, E.I., 2016. Operational arrangement of rhythm in Nigerian reggae songs. Nsukka Journal of the Humanities, 24 (2), 106–120.

- Onyeji, C., 2005. The impact of multimedia on popular music in Nigeria. Muziki, 2 (1), 21–25. doi:10.1080/18125980508538770

- Onyekwelu, C. 2020. Nigerian music, copyright and distribution in the internet era. Unpublished Master’s diss. University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

- Osiebe, G., 2019. The audacity of the Naira. The Naked Convos. Available from: https://thenakedconvos.com/the-audacity-of-the-naira [Accessed 15 July 2020].

- Osiebe, G., 2020. Methods in performing Fela in contemporary afrobeats, 2009–2019. African studies, 79 (1), 88–109. doi:10.1080/00020184.2020.1750349

- Oyeleye, L.A. and Gbadegesin, O.V., 2020. Multimodal construction of stardom in music reality shows: MTN project fame West Africa in perspective. Contemporary music review, 39 (1), 91–116. doi:10.1080/07494467.2020.1753476

- Partridge, C., 2005. The re-enchantment of the West Vol. 2: alternative spiritualities, sacralization, popular culture and occulture. London: Continuum.

- Pinto, C.A. and Larsen, U.S., 2006. Conclusion: fascism, dictators and charisma. Politics, religion and ideology, 7 (2), 251–257.

- Pisch, A., 2016. The phenomenon of the personality cult: a historical perspective. In: A. Pisch, ed.The personality cult of Stalin in Soviet posters, 1929–1953: archetypes, inventions, and fabrications. Acton, Australia: ANU Press, 49–86.

- Popoola, O.R., 2020. ‘I thought she was ordinary, I only saw her body’: sex and celebrity advocacy in Nigerian popular culture. Journal of African cultural studies, 1–15. doi:10.1080/13696815.2020.1762169

- Shonekan, S., 2011. Sharing hip-hop cultures: the case of Nigerians and African Americans. American behavioural scientist, 55 (1), 9–23. doi:10.1177/0002764210381726

- Shuker, R., 2012. Popular music culture: the key concepts. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Shuker, R., 2016. Understanding popular music culture. London: Routledge.

- Speier, H., 1977. The truth in hell: Maurice Jolly on modern despotism. Polity, 10 (1), 18–32. doi:10.2307/3234235

- Stout, A.D., 2003. Robyn Sylvan: traces of the spirit: the religious dimensions of popular music.’. Journal of media and religion, 2 (1), 65–67. doi:10.1207/S15328415JMR0201_5

- Sylvan, R., 2002. Traces of the spirit: the religious dimensions of popular music. New York: New York University Press.

- Sylvanus, P.E., 2013. Performing locale in Nigerian rap music: the forces of intertextuality and appropriation. Ikenga: international journal of the institute of African studies, 15 (1), 1–17.

- Sylvanus, P.E., 2018. Popular music and genre in mainstream Nollywood: introduction. Journal of popular music studies, 30 (3), 99–114. doi:10.1525/jpms.2018.200005

- Sylvanus, P.E., 2020a. Reflections on Nigerian musical arts and culture. Journal of the musicals arts in Africa, 17 (1–2), viii–x. doi:10.2989/18121004.2020.1851126

- Sylvanus, P.E., 2020b. The relevance of music to African commuting practices: the Nigerian experience. Contemporary music review, 39 (1), 37–58. doi:10.1080/07494467.2020.1753474

- Taylor, J., 2006. The production of the Chiang Kai-shek personality cult, 1929–1975. The China quarterly, 185, 96–110. doi:10.1017/S0305741006000063

- Till, R., 2010a. Pop cult: religion and popular music. New York: Continuum.

- Till, R., 2010b. Pop stars and idolatry: an investigation of the worship of popular music icons, and the music and cult of Prince. Journal of beliefs & values: studies in religion & education, 31 (1), 69–80. doi:10.1080/13617671003666761

- Titus, S.O., 2017. From social media space to sound space: protest songs during occupy Nigeria fuel subsidy removal. Muziki, 17 (2), 109–128. doi:10.1080/18125980.2016.1249163

- Toynbee, J., 2000. Making popular music: musicians, creativity and institutions. London: Oxford University Press.

- Veal, M., 2000. Fela: the life and times of an African musical icon. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.Tracks

- Am I A Yahoo Boy. 2019. Naira Marley ft. Zlatan. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vvBZk4a871I [Accessed 2 July 2020].

- Issa Goal. 2017. Naira Marley ft. Olamide & Lil Kesh. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3d_q-fxwbCg [Accessed 24 July 2020].

- Mafo. 2019. Naira Marley ft. Young John. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3nhO6b1XD2s [Accessed 5 June 2020].

- Maga Don Pay. 2008. Kelly handsome. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z0N_eFUUslM [Accessed 20 July 2020].

- Puta. 2019. Naira Marley. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gmdVFsUVPfk [Accessed 10 June 2020].

- Tesumole. 2019. Naira Marley. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8-f24T4gfr8 [Accessed 24 July 2020].

- Yahooze. 2007. Olu Maintain. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0MW7kcZnaiA [Accessed 20 July 2020].