ABSTRACT

This systematic review investigated small-group Tier 2 interventions to improve oral language or reading outcomes for children during preschool and early primary school years. Literature published from 2008 was searched and 152 papers selected for full-text review; 55 studies were included. Three strength of evidence assessment tools identified a shortlist of six interventions with relatively strong evidence: (a) Early Reading Intervention; (b) Lonigan and Philips (2016) Unnamed needs-aligned intervention; (c) PHAB+WIST (PHAST)/PHAB+RAVE-O; (d) Read Well-Aligned intervention; (e) Ryder and colleagues’ (2008) Unnamed Phonological Awareness and Phonics intervention; and (f) Story Friends. Investigation of intervention componentry found common characteristics included 3–5 students, 4–5 sessions per week, minimum 11-week duration, content covering a combination of skills, modelling and explicit instruction, and trained personnel. Shortlisted interventions provide a useful foundation to guide further interventions and inform educators and policymakers seeking to implement effective evidence-based interventions in the early years of schooling.

Introduction

Importance of oral language and literacy skills in the preschool and primary school years

Relationship between oral language and literacy

The ability to use and understand oral language to communicate effectively is central to children’s learning and academic success (Snow, Citation2016). In the early years of school, oral language competence underpins the ability to learn to read and the emergence of literacy skills more broadly (Castles, Rastle, & Nation, Citation2018; Dickinson, Golinkoff, & Hirsh-Pasek, Citation2010). There is a distinction to be made between the terms reading and literacy. For the purposes of this paper, and in line with the Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer, Citation1986), reading refers to the ability to decode, recognise, and understand the printed word, and the associated higher-level skills of sentence and text comprehension (Buckingham, Wheldall, & Beaman-Wheldall, Citation2013). Literacy encapsulates a broader set of skills, including reading, writing, and spelling and the ability to produce and engage with a variety of text types across the curriculum at all year levels (Buckingham et al., Citation2013; Snowling & Hulme, Citation2012). A reciprocal relationship exists between oral language and literacy, with improvements in one helping to advance skills in the other (Muter, Hulme, Snowling, & Stevenson, Citation2004; Snow, Citation2016).

Long-term and broader impact of oral language and literacy difficulties

Oral language competence is also strongly linked to a broad range of outcomes including social and emotional well-being, success in making and retaining friendships, prosocial problem solving, school engagement, and subsequent mental health (Snow, Citation2020). It is well recognised that if children do not learn to understand and use spoken language, and to read and write to communicate their ideas, there can be significant consequences for their self-esteem, social development, and educational and employment opportunities (Conti-Ramsden & Botting, Citation2008; Eadie et al., Citation2018; Law, Rush, Schoon, & Parsons, Citation2009; Lyon, Citation2003). Longitudinal research shows that students who struggle in the early years of school also tend to have difficulties in later grades (Maughan et al., Citation2009; St Clair, Pickles, Durkin, & Conti-Ramsden, Citation2011) and face long-term academic challenges with the risk of early disengagement from school (Snow, Citation2020). There is also evidence that some students, particularly those whose literacy difficulties are comorbid with behaviour disturbances, enter the so-called “school-to-prison” pipeline early in their school years. These are students who exit school prematurely following histories of suspension and exclusion and enter the youth justice system via community-based or custodial orders (Snow, Citation2019).

Prevalence of oral language and literacy difficulties

Difficulties with oral language and literacy are among the most common developmental problems in the preschool and primary school population (Snow, Citation2020). The estimated prevalence of developmental language disorder in young children (aged 4–5 years) is 7.6% (Norbury et al., Citation2016). Similar prevalence levels are reported for reading disorder in the population (Bishop & Snowling, Citation2004), whereas reading difficulty rates during primary school have been reported as approximately 10–30% of the school-aged population (Adolf & Hogan, Citation2019; Hempenstall, Citation2013; Snow, Citation2020).Footnote1 However, it is important to note that language and reading difficulties are often undiagnosed or misdiagnosed in the school system (Adolf & Hogan, Citation2019; Hendricks, Adolf, Alonzo, Fox, & Hogan, Citation2019; Snow, Citation2020).

Social and economic cost of oral language and literacy difficulties

Difficulties with oral language and literacy have serious ramifications for both individual life trajectories and social and economic costs (Cronin, Reeve, McCabe, Viney, & Goodall, Citation2020; Heckman & Masterov, Citation2007; Le et al., Citation2020). The causal link between educational attainment and a range of health and social outcomes (Gakidou, Cowling, Lozano, & Murray, Citation2010; Rhodes, Cordie, & Wooten, Citation2019) suggests the educational and social impact of oral language and literacy difficulties must be viewed as a population-level cost to society (Lyon, Citation2003; Tomblin et al., Citation1997) incurred across the lifespan (Law et al., Citation2009). In a review of research on outcomes for students experiencing reading difficulties, Slavin, Lake, Davis, and Madden (Citation2011) noted that reading failure incurs significant costs to education systems, in terms of special education, remediation, grade repetition and dropout. Language and literacy difficulties and low educational achievement in childhood are also associated with indirect costs in the longer term through reduced workforce participation and productivity losses in adulthood (Cronin et al., Citation2020).

According to a report from the Industry Skills Council Australia (Citation2011) examining the challenge of low language, literacy, and numeracy skills, approximately 46% of Australian adults have difficulty with reading, and 13% are classified in the lowest literacy category. Such difficulties with literacy make secure engagement in the workplace impossible for some adults. Working to optimise students’ oral language and literacy development, and subsequent educational outcomes, should pay significant dividends for individual students and society more broadly.

Importance of early intervention in the preschool and primary school setting

Research suggests oral language and literacy difficulties emerge early in childhood and become increasingly difficult (and expensive) to treat over time (Hempenstall, Citation2013; Spira, Bracken, & Fischel, Citation2005). Prevention and early intervention are generally considered more efficacious and cost-effective than attempts to remediate entrenched difficulties (Hempenstall, Citation2013, Citation2016). Evidence from reviews and meta-analyses consistently demonstrates that oral language and literacy interventions targeting children in the early years of school are particularly effective (Ehri, Nunes, Stahl, & Willows, Citation2001; Ehri et al., Citation2001; Piasta & Wagner, Citation2010) and potentially cost-effective (Hollands et al., Citation2016). However, addressing well-established deficits in the upper grades is more challenging (Wanzek et al., Citation2013). It has been noted that it takes four times as many resources to address a literacy problem in Year 4 than it does in Year 1 (Pfeiffer et al., Citation2001); yet, in many cases, children progress through the primary school years carrying a widening reading deficit relative to more able peers and relative to the demands of the curriculum (Hempenstall, Citation2013, Citation2016). This has been referred to as the Matthew Effect (Stanovich, Citation1986) and reinforces the fact that “the importance of getting children off to a good start in reading cannot be overstated” (Slavin et al., Citation2011, p. 2). Crucially, research evidence suggests that exemplary teaching, and effective and timely intervention, can lead to high levels of oral language and literacy achievement for at-risk or vulnerable students (Buckingham et al., Citation2013). It is therefore imperative that practicable and effective early interventions supported by the strongest levels of evidence are identifiable and available to educators and policymakers.

Education policy context

Historically, education policy in the United States of America (USA) has been criticised for creating conditions in which students struggling with literacy have either not been identified or have not received formal support or appropriate intervention until officially diagnosed with specific learning disabilities, which does not usually occur until Grade 2 or 3 (Gersten et al., Citation2009). In Australia, it has been argued that an “unnecessary and avoidable” level of illiteracy in students is due to “poorly conceived government policies and university education faculties wedded to outdated and unproven teaching methods” (Buckingham et al., Citation2013, p. 28). In addition, longitudinal studies have demonstrated there can be substantial individual variability in oral language performance across different measures or time points. Some children experience early delays and catch up with their peers, whereas others will develop later language difficulties following an apparently positive start, both in the preschool years and after school-entry (McKean et al., Citation2017). This instability has major implications for the provision of educational support, and careful monitoring of at-risk students over time has been recommended (Eadie et al., Citation2014; McKean et al., Citation2017).

In the USA, the No Child Left Behind Act of 2002 and Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004 have been instrumental in the wide-scale implementation of early oral language and literacy interventions and interest in Response to Intervention (RTI) approaches particularly (Gersten et al., Citation2009; Gersten, Newman-Gonchar, Haymond, & Dimino, Citation2017; Slavin et al., Citation2011). Following a shift in education reform to a more preventive approach to addressing learning difficulties, RTI (Fuchs & Fuchs, Citation2006) and the broader Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS; Eadie et al., Citation2018; Hall, Citation2018) frameworks have been introduced and are gaining momentum in research and school communities (Gilbert et al., Citation2013). RTI is a proactive, systematic improvement framework that is used to provide targeted support to struggling students, supporting academic growth and achievement (Fuchs & Fuchs, Citation2006). MTSS is more comprehensive and includes RTI but also supports many other areas such as social and emotional needs, and may include whole-of-school policies, professional development, and collaboration with parents (Eadie et al., Citation2018; Hall, Citation2018; Sugai, Horner, & Gresham, Citation2002). Within RTI frameworks, tiers of support increase in intensity from one level to the next and interventions are typically categorised into three levels of support (Fuchs, Fuchs, & Vaughn, Citation2008; Gersten et al., Citation2009). Tier 1 represents whole-class, high-quality, evidence-based classroom instruction that will result in most students benefiting from satisfactory rates of progress. Tier 2 supports involve additional instruction for small groups of students who do not make adequate progress with whole-class instruction alone, or who fail to meet benchmarks on screening measures. Tier 2 interventions are typically delivered to small groups of students in 20–40-min sessions, 3–5 times per week, for at least 5 weeks and are generally not offered for more than 25–30 weeks (Gersten et al., Citation2009; Wanzek et al., Citation2016). Tier 3 interventions are further intensified efforts to provide students with more intensive one-to-one support when they continue to struggle despite provision of Tier 1 and Tier 2 support after a reasonable amount of time. It is important to note that the interventions offered at Tiers 2 and 3 typically build directly on Tier 1 approaches, but with greater intensity, duration, and frequency (Fuchs & Fuchs, Citation2006).

The RTI framework presents a comprehensive, promising, and pragmatic approach to addressing difficulties with oral language and reading once children have commenced formal schooling. Indeed, it has been estimated that the incidence of reading difficulties can be dramatically reduced following effective Tier 1 classroom instruction, and further reduced following effective Tier 2 intervention, so that the number of students requiring more intensive and costly Tier 3 support can be minimised (Coyne et al., Citation2013; Gilbert et al., Citation2013; Lovett et al., Citation2017; Scanlon, Gelzheiser, Vellutino, Schatschneider, & Sweeney, Citation2008). According to some estimates, 80% of students respond satisfactorily to general instruction, and 15% are adequately served by small-group intervention, leaving 5% requiring more intensive Tier 3 support (Spencer, Petersen, & Adams, Citation2015). It has been argued that a tiered approach to intervention should decrease the number of students inappropriately referred to more intensive and costly individualised intervention (Tier 3), or special education (Fuchs, Compton, Fuchs, Bryant, & Davis, Citation2008). For many students, some small-group interventions can be as effective as more expensive one-to-one interventions (Elbaum, Vaughn, Tejero Hughes, & Watson Moody, Citation2000; Gilbert et al., Citation2013; Vaughn et al., Citation2003).

Overview of Tier 2 oral language and reading intervention

As briefly described above, Tier 2 intervention involves additional intensive student support that is compatible with, and builds upon, the core instruction provided at the universal level (Gersten et al., Citation2009). Tier 2 intervention should involve regular collection of student achievement data in order to (a) identify student needs regarding specific skill components, (b) choose appropriate interventions, and (c) monitor the impact of intervention on student progress so as to determine whether they are able to return to a lower level of support (i.e. Tier 1 classroom instruction only) or whether increased intensity of support is needed (i.e. Tier 3) (Gersten et al., Citation2009; Mellard, McKnight, & Jordan, Citation2010).

Tier 2 reading intervention content typically involves systematic and explicit instruction in the core skill components of reading instruction such as phonemic awareness (identifying, segmenting, and blending sounds orally), phonics and print knowledge (e.g. letter name and sound correspondence, including consonant clusters and digraphs), fluency (accuracy, speed, and expression), vocabulary development, and reading comprehension (Gersten et al., Citation2009; Hempenstall, Citation2016). Tier 2 intervention to support oral language tends to take a broad approach, typically focusing on areas such as vocabulary acquisition, attention and listening, sentence building and syntax rules (e.g. plurals, past tense, prepositions), and listening comprehension (e.g. following multi-step directions) and narrative (Sedgwick & Sothard, Citation2019).

Research on oral language and reading interventions in the preschool and primary school setting

There is growing research interest in Tier 2 oral language and reading interventions, and several recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have included an examination of small-group interventions (e.g. Gersten, Haymond, Newman-Gonchar, Dimino, & Jayanthi, Citation2020; Gersten et al., Citation2017; Sedgwick & Sothard, Citation2019; Slavin et al., Citation2011; Wanzek et al., Citation2016). For the most part, a broad approach has been taken, incorporating interventions beyond the parameters of small-group Tier 2 intervention.

Early childhood context

In early childhood contexts, there is some evidence that small-group interventions can have significant impacts on early language and literacy skills of preschool children at risk of academic difficulties (e.g. Lonigan, Schatschneider, & Westberg, Citation2008; Marulis & Neuman, Citation2010; Shepley & Grisham-Brown, Citation2019). Notably, however, the focus is on interventions across the tiers, rather than on Tier 2 explicitly. For example, the National Early Literacy Panel (National Early Literacy Panel, Citation2008) reported on meta-analyses of intervention studies aimed at the development of early literacy skills. Findings indicated moderate to large effects on outcomes related to language and literacy (e.g. phonological awareness and early reading skills), although the review included interventions conducted at the individual level as well as small-group interventions (Lonigan et al., Citation2008). Marulis and Neuman (Citation2010) conducted a meta-analysis examining the effects of vocabulary interventions on language development with children in preschool and the early years of primary school. Although results indicated a strong effect size overall (g = 0.88), the meta-analysis was not focused on a specified group size or support tier, thus included individualised and large-group interventions as well as those delivered to small groups. Also looking across the tiers, Shepley and Grisham-Brown (Citation2019) examined the available literature on MTSS (or a specific tier within it). Interventions for preschool children (ages 3–5 years) targeting a range of developmental/content domains, including literacy and language, were reviewed. Mean effect sizes indicated that clinically significant findings were evident for language and literacy outcomes; however, when considering only the studies with the most rigorous research designs, the effects typically lessened or were less frequently detected (Shepley & Grisham-Brown, Citation2019).

Primary school context

In the primary school context, Sedgwick and Sothard (Citation2019) and Slavin et al. (Citation2011) both conducted reviews of oral language and reading interventions across the RTI tiers (including small-group interventions) and positive effects of small-group interventions were demonstrated. Specifically, Sedgwick and Sothard (Citation2019) conducted a recent review of mainstream school-based oral language interventions for children with speech, language, and communication needs in the early years of school in the United Kingdom. Five studies comparing the effects of intensified small-group instruction with a usual-practice or other control group were identified, and they all reported positive effects (although information regarding comparison groups or results for each of the studies were not reported in detail in the review). Similarly, Slavin et al.’s (Citation2011) systematic review of 97 studies evaluating a range of reading interventions for struggling readers identified 20 small-group studies and the overall mean effect size for these interventions was 0.3. However, Slavin et al. (Citation2011) did not include a separate analysis of small-group interventions specifically targeting children in the early years of school in their review.

Tier 2 interventions

To date, there have been only three systematic reviews with an explicit focus on Tier 2 interventions (rather than across the tiers) for children with reading difficulties in the early years of school (Gersten et al., Citation2020, Citation2017; Wanzek et al., Citation2016). Wanzek and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 72 predominantly experimental and quasi-experimental studies that focused on children in Grades K-3 and were published between 1995 and 2013. Interestingly, however, the authors defined Tier 2 reading interventions in terms of session quantity (specifically 15–99 sessions), and thereby included interventions delivered in a one-on-one instructor-to-student format. Wanzek and colleagues reported positive effects of intervention for foundational reading skills measured with standardised (Hedges’ g = 0.49) and non-standardised (g = 0.61) tests, as well as standardised (g = 0.38) and non-standardised (g = 1.03) measures of language or reading comprehension. Effect sizes across all measures appeared higher for interventions delivered to student pairs/trios, compared to groups of 4–5 students. These findings show that, on average, Tier 2 interventions targeting struggling readers have demonstrated positive effects on foundational reading skills and on measures of language or reading comprehension.

A more recent review (Gersten et al., Citation2017) and meta-analysis (Gersten et al., Citation2020) of US-based reading interventions also provide evidence of positive effects. Gersten et al. (Citation2017) focused on 20 interventions trialled in studies meeting What Works Clearinghouse standards published between 2002 and 2014, then conducted a meta-analysis of 33 studies including those published up to 2017 (Gersten et al., Citation2020). As in the Wanzek et al. (Citation2016) meta-analysis, Gersten and colleagues’ reviews included interventions with a one-to-one format in their definition of Tier 2. Interestingly, however, they acknowledged that in usual RTI practice, schools almost always implement small-group (3–5 students) interventions at Tier 2. Of the 20 included Tier 2 interventions, the 2017 review identified only nine small-group interventions. Positive effects (defined in the review as the treatment group performing better than the comparison group by a statistically significant margin in at least one area of reading in at least one study) were reported for eight of these nine interventions. Similarly, of the 33 included studies in the Gersten et al. (Citation2020) meta-analysis, 21 were of interventions conducted one-to-one. Significant positive effects on a range of reading outcomes were reported, with a mean effect size of .39 (Hedges’ g).

Rationale for this review

Although the findings from the Wanzek et al. (Citation2016) meta-analysis and the Gersten et al. (Citation2020); (Citation2017) reviews are encouraging, further research is needed for a number of reasons. For pragmatic purposes, schools need to know (a) whether small-group Tier 2 oral language and reading interventions are generally effective, and (b) what components effective Tier 2 interventions have in common. Such components may be the active ingredients and indicative of programs that schools could reasonably expect to be effective. If schools are unable to implement programs with a strong evidence base, then they can at least identify programs that share the most common characteristics to those programs that do have a strong evidence base. Moreover, educators need to know which interventions are most likely to be effective when implemented within a particular educational context or with particular groups of students, and which are feasible to deliver with high levels of fidelity. Fidelity of implementation is typically difficult to evaluate because it is not consistently operationally defined and measured (Gersten et al., Citation2020). Further research is also needed to identify interventions trialled in recent years and not included in previous reviews.

Information about the features that characterise the most effective interventions with a robust evidence base may also prove instructive. However, to date, there has been no systematic review of the componentry associated with the strongest Tier 2 language or reading interventions for children in preschool and the early years of primary school. Although Wanzek et al. (Citation2016) and Gersten et al. (Citation2020) investigated several intervention features as potential moderators, the analyses were not specific to small-group interventions and were underpowered in many cases.

Aims

In this restricted systematic review (Pluddermann, Aaronson, Onakpoya, Heneghan, & Mahtani, Citation2018), we sought to identify effective small-group Tier 2 interventions that schools could implement to improve oral language or reading outcomes for children. The review focuses on interventions that have been tested with children in the preschool and early primary school years, and was guided by the following research questions:

Which small-group Tier 2 interventions for preschool to Grade 2 children improve oral language or reading outcomes?

Which of these interventions are supported by relatively strong levels of evidence?

What components do the most effective Tier 2 oral language and reading interventions have in common?

In this review, we have chosen to focus on literacy skills broadly defined and have also included studies with a narrower focus on reading, which in turn has implications for the acquisition of broader literacy skills.

Method

A detailed study protocol covering review questions, search strategy, selection criteria, coding procedures, risk of bias assessment, and data synthesis, was developed and prospectively registered with the international register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42019126121). A restricted systematic review approach was utilised. Restricted systematic reviews use similar methods to full systematic reviews but make concessions to the depth and breadth of the process for the purpose of providing critical information and rigorous assessment relatively quickly. Methodological decisions were guided by existing recommendations for best practice in such reviews (Ganann, Ciliska, & Thomas, Citation2010; Kelly, Moher, & Clifford, Citation2016; Pluddermann et al., Citation2018). This review adhered to the guidelines in the PRISMA statement (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Citation2009).

Search procedures

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across several academic databases (Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Education Research Complete (ERC), Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO and SCOPUS), reputable program registers (Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development; Promising Practices Network on Children Families and Communities; and the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare), and language and literacy-specific databases (What Works Clearinghouse; Speechbite repository; Communication Trust What Works). The Cochrane and Campbell databases were also searched for relevant systematic reviews. Reference lists of included papers were also searched.

Database searches were developed in consultation with an experienced librarian and applied a PICO-based framework (Schardt, Adams, Owens, Keitz, & Fontelo, Citation2007). Each had the general form: (preschool to primary school age terms) AND (language or reading difficulty terms) AND (general intervention or Tier 2 specific terms) AND (study design terms) AND (language or literacy outcome terms). Search keywords and example syntax are listed in Table S1 (online only). Initial searches were restricted to publications from 1990 to the date of search (October 2018). A substantive body of potentially relevant literature was identified; therefore, in accordance with the registered study protocol (PROSPERO; CRD42019126121), the search range was further restricted to journal articles published from 2008 onward (i.e. to strengthen applicability of findings to the current educational context, while also balancing resource and time constraints with review scope).

Selection criteria

Studies were considered potentially relevant if the title or abstract indicated that the study included (a) children in the preschool to Grade 2 range (or ages 4–9 years as children usually receive formal reading instruction over this period, with some variation across different education settings and systemsFootnote2), (b) targeted supplemental instruction in literacy or oral language skills, and (c) a treatment and comparison group. Studies were excluded if information explicitly contraindicated full-text inclusion criteria.

At full-text screening, studies were selected if they also met the following inclusion criteria: (a) children attended a mainstream education setting (i.e. not segregated special education settings); (b) children were identified as at-risk of or experiencing oral language or reading difficulties, on the basis of screening tests, formal diagnoses, or teacher or parent concern; (c) intervention specifically targeted students with emerging or established language or reading problems; (d) intervention was implemented in a small-group format of supplementary instruction (i.e. not universal classroom practices or one-to-one tutoring); (e) intervention occurred on-site at school during regular school terms and hours; and (f) intervention was implemented by regular school staff, community members, allied health professionals, or researchers.Footnote3 In addition, studies had to (g) compare a randomly or non-randomly assigned Tier 2 intervention group with a usual practice, alternative treatment, or waitlist control group, (h) on at least one oral language (e.g. expressive language, receptive language, vocabulary) or reading skill (e.g. phonics knowledge, word recognition, reading fluency, passage comprehension) and (i) analyse group mean difference scores following intervention. Finally, studies had to (j) be published from 2008 in an English language journal article.

Studies were excluded if they did not meet all of the above criteria or met any of the following exclusion criteria: intervention (a) exclusively targeted second-language learners, (b) was designed for children with severe and specific diagnoses not primarily defined by difficulty with oral language or literacy (e.g. autism, ADHD, Down syndrome), (c) included systematic provision of one-to-one support to a portion of students (d) was delivered in low-/middle-income countries or with education systems considered substantially different from North America, the United Kingdom, Australia, or New Zealand. Studies were also excluded if analysis was limited to (a) comparison with a historical control group only, (b) a proportion of “responders”, or (c) a redundant data set (i.e. analysis of the same outcomes, at the same timepoints, with an overlapping sample of students).Footnote4 See Table S2 (online only) for the rationale behind each of the selection criteria.

As per the registered study protocol (PROSPERO; CRD42019126121), at both the abstract and full-text screening phases, 10% of papers were randomly selected for double-coding by a second independent reviewer. Inter-rater agreement for inclusion/exclusion was high (90% abstracts, 100% full-text), and examination of discrepancies showed no instances where prevention of relevant papers progressing to full-text screening would occur erroneously. Coders discussed differences and reached 100% consensus.

Coding procedures

Studies that met inclusion criteria were coded by an experienced reviewer with the following data extracted: research design (e.g. randomised or quasi-experimental study; type of comparison group/s), participant information (e.g. mean age and grade range, selection criteria, school context, country, socio-economic status), intervention componentry (e.g. specific oral language and literacy skills targeted, general pedagogical strategies, group size, intensity and duration, type of provider), outcomes assessed (e.g. standardised and treatment-aligned measurements, time of assessment), results (e.g. statistical significance of group mean differences and effect size), intervention feasibility (e.g. cost, implementation fidelity, social validity), and overall relevance (e.g. percent of sample in preschool to Grade 2 years). A 10% sample of papers was randomly selected and double-coded by a second independent reviewer. Inter-rater agreement for data extraction was high (94%) and differences were resolved through discussion.

Study quality and intervention-level evidence assessment

As part of the process for identifying interventions with the strongest levels of evidence, risk of bias was evaluated for each study. Specifically, study quality was evaluated using an 11-itemFootnote5 checklist adapted from recent meta-analyses in education research (e.g. Graham et al., Citation2018) to assess both education-specific risks and critical design features recognised across many scientific fields (see Table S3; online only). Appropriate education-specific items were identified in a recent meta-analysis of literacy interventions (Graham et al., Citation2018) and general items from established quality and bias checklists (e.g. NICE, Citation2012). Items covered the following quality criteria: experimental design, sample size and pre-test equivalence, attrition (overall and differential), measurement, condition descriptions, blinded assessment, and statistical analysis. Items were coded 1 if fully satisfied, 0.5 if partially satisfied, and 0 if inadequately addressed. A total score was calculated, and the following cut-points applied to categorise study quality as low (<50%), moderate (50–74%), and high (75+%), consistent with other systematic reviews (e.g. Bond, Wood, Humphrey, Symes, & Green, Citation2013; Sedgwick & Sothard, Citation2019).

An evidence rating system was also conducted for each intervention. For pragmatic purposes,Footnote6 three distinctive evidence ranking systems were used to shortlist interventions supported by the strongest evidence: (a) a customised strength of evidence evaluation, and two established frameworks; (b) the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse (CEBC, Citation2016) Scientific Rating Scale; and (c) the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Body of Evidence matrix (Hiller et al., Citation2011).

The customised evidence rating system was adapted from established frameworks (e.g. CEBC Scientific Rating Scale; Institute of Education Sciences levels of evidence for practice guidelines; What Works Clearinghouse evidence standards; Promising Practices Network on Children Families and Communities evaluation criteria; Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development evidence standards) and considered several factors (i.e. study design, risk of bias, sample size, direction and magnitude of effect, convergence of evidence across studies – see ). Interventions rated as having Very Strong evidence according to the customised evidence rating were shortlisted, as were interventions receiving a Supported or Well Supported ranking on the CEBC or meeting Level A or Level B criteria using the NHMRC assessment.Footnote7

Table 1. Customised evidence rating system.

Data synthesis

As the primary purpose of the review was to identify effective school-based Tier 2 oral language and literacy interventions supported by the strongest levels of evidence, and their key components, a narrative synthesis of the findings is presented.

Results

Study selection

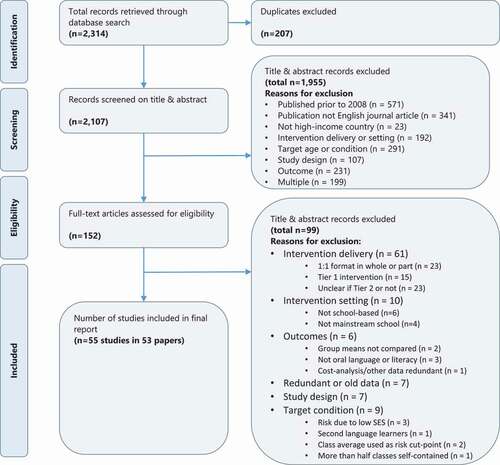

provides an overview of the search and selection process. After screening 2107 abstracts, 152 articles were selected for full-text review. Ninety-nine articles were excluded (listed in Table S4 [online only] with reasons), leaving 53 articles describing 55 included studies (two publications each described two separate studies). See for an overview of included studies.Footnote8 For further demographic information (e.g. age, gender, SES, language, race) see Table S5 (online only). From the 55 included studies, 47 separate interventions were identified.

Table 2. List of included studies.

Table 3. Characteristics of the included studies.

Study findings

Overall, most studies reported at least one statistically significant positive effect of the Tier 2 oral language or literacy intervention relative to a usual practice comparison condition (whether Tier 1 whole-of-class instruction or multi-tiered usual practices). In some cases, Tier 2 interventions performed similarly to Tier 3 interventions where students received one-to-one sessions (Gilbert et al., Citation2013; Schwartz, Schmitt, & Lose, Citation2012). Effect sizes ranged from very small (i.e. < 0.20) to quite large (e.g. 2.17). As shown in , effect sizes were not obviously related to study quality (i.e. large effects were observed in both low- and high-quality studies, as were small effects). As a group, the 55 studies indicate that school-based oral language and literacy interventions for children in the preschool and early primary school grades can have a significant effect on short-term intended outcomes, though the magnitude of effects varies considerably (and the largest effects tend to emerge in studies with very small samples or on treatment-aligned, researcher-designed measures). Nevertheless, educationally meaningful effects (some considered moderate-to-large by conventional standards) were also observed in high-quality studies and on summarised measures. For example, flexible delivery of the Early Reading Intervention (Coyne et al., Citation2013; Little et al., Citation2012; Simmons et al., Citation2011, Citation2014) demonstrated positive effects on the WRMT subscales ranging from 0.54 to 0.76 at immediate post-test and 0.39 to 0.64 at 1-year follow-up; and the Responsive Reading Intervention (Denton et al., Citation2010) demonstrated positive effects ranging from 0.44 on the TOWRE, to 0.63 on some WJIII subscales. As might be expected, a general shift in intervention focus was observed such that preschool interventions predominantly involved oral language with particular emphasis on vocabulary, whereas primary school interventions were more focused on reading, with most emphasis on decoding.

Intervention-level evidence

The strength of evidence assessments for the 47 interventions in the included studies is summarised in . The three evidence rating systems identified a different, but overlapping, shortlist of interventions (i.e. those with the strongest evidence). The customised evidence rating system identified three interventions with Very Strong evidence. These are Early Reading Intervention (ERI; Coyne et al., Citation2013; Little et al., Citation2012; Simmons et al., Citation2011, Citation2014), PHAST/PHAB+RAVE-O (Morris et al., Citation2012) and Read Well-Aligned (Wonder-mcdowell, Reutzel, & Smith, Citation2011). Using the CEBC Scientific Rating Scale, three interventions received high (Well Supported or Supported) evidence ratings. These are the Early Reading Intervention (ERI), PHAST/PHAB+RAVE-O (Morris et al., Citation2012) and Ryder, Tunmer, and Greaney (Citation2008) Unnamed Phonological Awareness and Phonics intervention. Using the NHMRC evidence matrix, no interventions met the highest level of evidence, but three aligned with the second-highest category. These are Early Reading Intervention (ERI; (Coyne et al., Citation2013; Little et al., Citation2012; Simmons et al., Citation2011)), Story Friends (Goldstein et al., Citation2016), and Lonigan and Phillips (Citation2016) Unnamed needs-aligned intervention. As shown in , the evidence assessments show six interventions were shortlisted, only two of which were identified by two or more of the three evidence rating systems (Early Reading Intervention and PHAST/PHAB+RAVE-O).

Table 4. Strength of evidence assessments for each intervention.

Synthesis: shortlist of interventions

Componentry (procedural and content) for the six interventions shortlisted by the strength of evidence assessments is summarised in . See Table S6 (online only) for a detailed description of componentry for all programs, and Table S7 (online only) for a simplified visual representation of componentry for all programs together with evidence ratings for each intervention. shows that the number of students in the small-group interventions were approximately 3–5 students for four of the six interventions (the remaining two had a range of 2– 4 or 2–6 students). Intervention dosage schedule was approximately 4–5 times per week for four of the interventions (sessions were 20–40 min for three of these, and 60 min for the other). For another intervention, however, dose was much lower (sessions were 9–12 min, 3 times per week), and for the final intervention, dose was 30 min per session and offered 2–5 times per week depending on the schedule for each treatment group. There was also variation regarding the duration of the shortlisted interventions with the number of implementation weeks ranging from 11 to 26. As can be seen in , intervention durations were mostly reported as an approximation, a range, or shown to vary according to the intervention session schedule.

Table 5. Componentry of shortlisted interventions.

For the most part, the content of the shortlisted interventions focused on multiple language and reading components. Four of the interventions included instruction and activities focused on a combination of phonological awareness (e.g. rhyming, identifying syllables, isolating sounds for first and last letters, and blending and segmenting sounds), phonics (e.g. letter-sound correspondence), reading fluency, listening comprehension (e.g. following multi-step instructions and re-telling stories), vocabulary (e.g. targeting semantic categories and concepts in a story), syntax rules and uses, and morphological components. The other two each had a narrower focus, with one centred on instruction in phonological awareness and phonics, and the other focusing on narrative development with lessons incorporating vocabulary instruction (in unfamiliar words that occur frequently in spoken and written language), and language comprehension (using inferential questions about story predictions and character emotions and actions).

Of the pedagogical strategies included in the shortlisted interventions, use of modelling, explicit instruction, and interactive programmingFootnote9 were reported most frequently (each reported for five interventions), followed by scaffolding and mastery (reported for three interventions). Use of self-monitoring, provision of corrective feedback, and meta-cognitive strategies were less commonly reported, featuring in one intervention each. Detailed, sequenced lessons and instructional scripts were utilised by four of the shortlisted interventions, and materials, objects, and props (e.g. letter tiles, picture cards, individual white boards) were used in three interventions to make abstract concepts more concrete. Most shortlisted interventions were implemented either by teachers or reading specialists or by teams that included teachers in addition to teaching assistants. It is difficult to identify common characteristics regarding provider qualifications, previous experience, and training as this was not well-reported. However, it appears that in most cases, the interventions were implemented by personnel with relevant tertiary-level qualifications (e.g. teachers, teaching assistants, reading specialists, paraprofessionals, or tutors). Five of the six shortlisted interventions involved formal pre-intervention training; however, the duration of training varied greatly, ranging from approximately 7 to 70 h. As these interventions were being delivered, support for implementers was characterised by some form of coaching (e.g. modelling, individualised feedback, regular meetings), and three of the interventions also included formalised peer support (e.g. regular small-group meetings, group email list/forum). However, the intensity of the implementation support was not described in detail. There was one intervention that did not involve training and support as this was an automated storybook supervised by an educator or researcher (Story Friends) and was specifically designed to minimise the need for extensive training or implementation support.

For pragmatic purposes, it is important to know not only which interventions have a strong evidence-base, but whether they are well-received by stakeholders (such as teachers, parents, and students) and are affordable. A quantitative evaluation of social validity was presented by only seven of all included studies, and only two of the shortlisted interventions (Early Reading Intervention and Story Friends). Both these interventions were rated positively by teachers, but parent and student perceptions were not assessed. Detailed information about intervention costs was available for only two interventions (Boyle, McCartney, O’Hare, & Forbes, Citation2009; Madden & Slavin, Citation2017), neither of which was shortlisted.

Discussion

In this review, we aimed to identify which primary school- and preschool-based small-group Tier 2 interventions are shown to improve oral language or reading outcomes for children, supported by the strongest levels of evidence. Information regarding the intervention focus, frequency, duration, implementer, and group size is needed to inform implementation decisions. There are important implications for who (and how many) students are ultimately referred to more intensive interventions and special education services (Wanzek et al., Citation2016).

Summary of evidence

Of the 55 studies included in the review, 44 (79%) reported some statistically significant positive mean differences on relevant outcomes. However, only six interventions were identified as having the strongest levels of evidence using one of the three strength of evidence assessment tools (CEBC Scientific Evidence Rating, NHMRC Recommendation Grade, and the Customised Evidence Rating) and shortlisted in this review: (a) Early Reading Intervention; (b) Lonigan and Phillips (Citation2016) Unnamed needs-aligned intervention; (c) PHAB+WIST (PHAST)/PHAB+RAVE-O; (d) Read Well-Aligned intervention; (e) Ryder et al. (Citation2008) Unnamed Phonological Awareness and Phonics intervention; and (f) Story Friends. (See –5 for study overviews, strength of evidence assessments, and core componentry.)

When considering the componentry of the six shortlisted interventions, there is some consistency regarding their content focus, structure, and implementation. This information about the componentry associated with the strongest Tier 2 language and reading interventions for children in the early years of school is useful given there has been no systematic review addressing this to date. The interventions shortlisted in this review typically included content relating to phonological awareness, phonics, and vocabulary instruction (in the context of language or literacy), and there was consistency regarding the type of pedagogical strategies used (e.g. most interventions were considered “interactive”, involving modelling, explicit instruction and scaffolding). Further, shortlisted interventions are typically characterised by the following procedural components: group size of approximately 3–5 students, meeting at least four times per week for sessions lasting approximately 30 min, with an overall duration of around 3–6 months. Intervention implementation was conducted/supervised by personnel with relevant qualifications and experience, but the duration of training provided to implementers varied greatly, and the training details were not well reported overall. Information regarding support for implementers as the intervention is delivered was also not always well reported. It is important to know detailed information about training and the intensity of implementation support required to deliver interventions that improve oral language and reading because of the substantial cost implications (Hollands et al., Citation2016).

There are some important distinctions between the scope and methodology employed in this review compared to the three notable previous reviews (Gersten et al., Citation2020, Citation2017; Wanzek et al., Citation2016). The authors of the Wanzek et al., review searched just two databases (ERIC and PsychINFO) between 1995 and 2013 and included 72 studies from 69 papers. In contrast, in this review, we (a) focused on more recent research (i.e. 2008 to 2018); (b) covered more databases; (c) used more search terms; (d) encompassed a slightly different age range (i.e. included preschool studies, but not Grade 3s); (e) did not restrict selection of interventions to those with 15–99 sessions; (f) defined Tier 2 interventions in terms of group size, specifically small-group interventions, with explicit exclusion of one-to-one interventions; and critically (g) took into account study quality/risk of bias. Although information about level of confidence in causality was collected by Wanzek et al., this information does not appear to have been used for the purpose of weighting studies in the meta-analysis or in the interpretation of results.

The Gersten et al. (Citation2017) review and meta-analysis (Gersten et al., Citation2020) included only studies meeting What Works Clearinghouse evidence standards (and included one-to-one interventions). Of the studies originally reviewed by Gersten et al. (Citation2017) and Gersten et al. (Citation2020) almost all were reported to have positive or potentially positive effects. In the Gersten et al. (Citation2017) review, most of these interventions were implemented for 30–45 min per day, 4–5 times a week, for 12–35 weeks. The Gersten et al. (Citation2020) meta-analysis provided less detail about intervention dosage, with hours per week described as ranging from less than 1 h to 4 h and intervention duration not reported. Although the set of interventions identified in the Gersten et al. reviews are different to those shortlisted by this review, the finding concerning intervention dosage is broadly consistent. Interestingly, the Gersten et al. reviews did not identify any interventions with positive effects on vocabulary, whereas this review identified several – including some with strong evidence.

Strengths and limitations

This review followed core steps and minimum requirements for restricted systematic reviews (Pluddermann et al., Citation2018). Moreover, additional steps recommended for reducing risk of bias (Pluddermann et al., Citation2018) were taken, including verification of study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias assessments by a second reviewer (for a random sample of papers).

Three evidence rating systems were incorporated into this review, including a customised strength of evidence assessment in order to provide a more nuanced picture of the literature. Although the CEBC and NHMRC scales each identified several interventions with high evidence ratings, the bulk of studies align to a single category (38 of 47 interventions are rated Promising for the CEBC, and 35 are rated level C – the body of evidence provides some support for the NHMRC assessment). In contrast, within the intermediate levels of evidence, the customised rating system identified 9 interventions as promising and 17 with preliminary evidence. This is a useful distinction to make when there is a need to identify interventions that have demonstrated positive effects with specific populations or on specific outcomes, and the top-rated interventions do not fit these specifications. The customised assessment is also more sensitive to interventions with weak evidence (it identifies 13 interventions as such, compared with 6–8 interventions for the CEBC and NHMRC scales, respectively).

Potential limitations should also be acknowledged. First, the search range for the review was restricted to journal articles published from 2008 onwards. It is important to note that (a) there was sufficient relevant literature published in this period to address the review aims and questions, and (b) the recency of included literature increases the applicability of findings to contemporary education systems. Second, the review focused on experimental and quasi-experimental studies only. Although it is possible that effective interventions other than those identified in this review exist, their effectiveness cannot reliably be determined without rigorous evaluation design (demonstrating that effects are indeed attributable to the intervention and not to other factors). Along a similar line, the review included several studies that explicitly investigated the combined effects of Tier 1 and Tier 2 instruction (e.g. Chambers et al., Citation2011; Scanlon et al., Citation2008; Smith et al., Citation2016; Wonder-mcdowell et al., Citation2011). In these studies, the intervention involved manipulation of both Tier 1 and Tier 2 instruction, rather than Tier 2 only. In such cases conclusions about the small-group intervention cannot be made independently from the core instruction. However, this does not necessarily negate the utility of the approach, nor school interest in the adoption of multi-tiered interventions. Finally, the analysis of componentry focused on the best supported interventions rather than a comparison of the more and less effective interventions. This approach is consistent with best-evidence synthesis approaches used by other researchers in this field (e.g. Gersten et al., Citation2017; Slavin et al., Citation2011). As Slavin and colleagues previously noted, this type of approach is appropriate when the goal is to provide educators and policymakers with a fair comparison of interventions.

Future directions

This review lays a good foundation for investigating the overall magnitude of small-group Tier 2 oral language and reading interventions in the early primary school years. Meta-analytic procedures could be used in future research to explore the magnitude of effects for different populations (what works for who), different outcomes, and critically, different componentry (e.g. implementer, dose and duration, content). The extent to which study quality is related to effect sizes should also be considered in future meta-analytic investigations of Tier 2 interventions.

Another avenue for future research will be to explore the extent to which Tier 2 interventions close oral language and literacy achievement gaps, and the proportion of students for whom they do so. To allow comparison between interventions, this review focused on examining differences in mean scores (i.e. students in the intervention groups had on average better results). This does not go to the key questions of interventions for language and reading difficulties. Future research may consider which interventions lead to improved student scores and sustained impacts for those children no longer requiring Tier 2 intervention. Analyses of this sort are not well-reported in the literature. Indeed, of the studies included in this review, approximately only one-third reported either gap-relevant data (e.g. comparison to a typically developing peer group or mean scores in percentiles) or ideographic data (e.g. proportion of students meeting benchmark at intervention completion). Further research is also needed to determine the long-term maintenance of effects for most interventions (i.e. delayed follow-up testing beyond 12 months post-intervention). Finally, there is a need for continued updating of the review as new studies are published and evidence increases for some programs (e.g. the Enhanced Core Reading Intervention; Fien et al., Citation2020).

Conclusion and implications

Overall, the standard of research investigating Tier 2 oral language and reading interventions is limited and of variable quality. Only 14 of 55 studies met high-quality standards. Clearly, there is a need for more rigorous evaluation of small-group Tier 2 oral language and early reading classroom interventions for preschool to Grade 2 students. Nevertheless, our analysis of the extant literature did identify several interventions for which the evidence base can be considered strong. This information should be valuable to researchers and intervention developers interested in identifying the core components of effective intervention, to educators seeking to implement effective evidence-based interventions in their schools, and policymakers responsible for guiding, and in some cases mandating, particular resource-allocation decisions.

Supplemental_table_S7_visual_representation_of_componentry.docx

Download MS Word (48.5 KB)Supplemental_table_S6_detailed_componentry_by_study.docx

Download MS Word (33.6 KB)Supplemental_table_S5_detailed_demographics_per_study.docx

Download MS Word (44.8 KB)Supplemental_table_S4_Excluded_studies.docx

Download MS Word (43.2 KB)Supplemental_table_S3_items_for_study_quality.docx

Download MS Word (16.4 KB)Supplemental_table_S2_Rationale_for_selection_criteria.docx

Download MS Word (24.2 KB)Supplemental_table_S1__Search_strategy.docx

Download MS Word (16.9 KB)Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the North East Victoria Region, Schools and Regional Services, Department of Education and Training, Victoria; Melbourne Archdiocese Catholic Schools; Catholic Education Sandhurst Ltd; Diocese of Sale Catholic Education Ltd; and Diocese of Ballarat Catholic Education Limited. Research at the MCRI is supported by the Victorian Government's Operational Infrastructure Support Program. SG is supported by a NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship (GNT1155290). We acknowledge the contribution of Catherine Lloyd-Johnsen to double-coding and data extraction.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. There is an important distinction between disorder and difficulty. Disorder is a categorical definition based on a diagnosis whereby an individual experiences lifelong, pervasive difficulties and does not respond quickly or significantly to intensive intervention. In contrast, an individual with a language or reading difficulty is more likely respond readily to intensive intervention (Australian Disability Clearinghouse on Education and Training, Citationn.d.).

2. We included both preschool and school settings as the age at which children start school varies both within and across different national contexts (Krieg & Whitehead, Citation2015). Research shows children who start school at a younger age relative to their peers tend to be more developmentally vulnerable (Hanly et al., Citation2019), and we therefore expect that such children may benefit from interventions tested with preschool children.

3. This criterion is not strictly consistent with the registered study protocol which stated that the intervention must be delivered by regular school staff, and interventions delivered by allied health professionals will be considered on a case-by-case basis. In practice, this review also included researcher-delivered interventions as these were also considered to be feasible for implementation by school staff.

4. We retained studies of the same samples if comparisons were different (e.g. intervention versus usual practice in one publication, and intervention versus alternative program or variation on same program in another publication).

5. A 15-item checklist was originally devised but four items were dropped as they were not applicable to all included study designs or required complex judgments (e.g. risk of contamination taking into account multiple factors such as design, implementer, and type of intervention).

6. It was originally anticipated that established frameworks might be somewhat insensitive to the relative strength of evidence for the bulk of identified interventions (because these frameworks require either long term follow-up evaluation or low risk of bias together with cross-study consistency in findings for high ratings). Including three systems in the evidence assessment allowed for an assessment of sensitivity, consistency across rating systems, and comparison of results when different criteria are emphasised.

7. Within the CEBC ranking system, an intervention may be rated Supported if: “At least one rigorous RCT in a usual care or practice setting has found the practice to be superior to an appropriate comparison practice, and in that RCT, the practice has shown to have a sustained effect of at least six months beyond the end of treatment, when compared to a control group” (see www.cebc4cw.org/ratings/scientific-rating-scale). In the NHMRC ranking system Level B evidence requires one or two RCTs with low risk of bias or multiple pseudo-randomised controlled studies with low risk of bias demonstrating substantial clinical impact and consistent results across most studies.

8. The term “studies” is not synonymous with “samples/trials”. Some studies present different outcomes for the same trial (e.g. maintenance effects), or different comparisons for the same sample (e.g. intervention vs. usual practice in one study, and intra-intervention comparisons within another study).

9. “Interactive programming” refers to intervention involving students interacting with content/materials in some way, for example, manipulating letter tiles, flexible exploring of computer program, etc.

References

- *Bailet, L. L., Repper, K., Piasta, S. B., & Murphy, S. P. (2009). Emergent literacy intervention for prekindergarteners at risk for reading failure. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(4), 336–355.

- *Boyle, J. M., McCartney, E., O’Hare, A., & Forbes, J. (2009). Direct versus indirect and individual versus group modes of language therapy for children with primary language impairment: Principal outcomes from a randomized controlled trial and economic evaluation. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 44(6), 826–846.

- *Buckingham, J., Wheldall, K., & Beaman, R. (2012). A randomised control trial of a Tier-2 small-group intervention (“Minilit”) for young struggling readers. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 17(2), 79–99.

- *Case, L., Speece, D., Silverman, R., Ritchey, K., Schatschneider, C., Cooper, D. H., … Jacobs, D. (2010). Validation of a supplemental reading intervention for first-grade children. Journal of Learning Difficulties, 43(5), 402–417.

- *Case, L., Speece, D., Silverman, R., Schatschneider, C., Montanaro, E., & Ritchey, K. (2014). Immediate and long-term effects of Tier 2 reading instruction for first-grade students with a high probability of reading failure. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 7(1), 28–53.

- *Chambers, B., Slavin, R. E., Madden, N. A., Abrami, P., Logan, M. K., & Gifford, R. (2011). Small-group, computer-assisted tutoring to improve reading outcomes for struggling first and second graders. Elementary School Journal, 111(4), 625–640.

- *Coyne, M. D., Simmons, D. C., Hagan-Burke, S., Simmons, L. E., Kwok, O., Kim, M., … Rawlinson, D. M. (2013). Adjusting beginning reading intervention based on student performance: An experimental evaluation. Exceptional Children, 80(1), 25–44.

- *Denton, C. A., Cirino, P. T., Barth, A. E., Romain, M., Vaughn, S., Wexler, J., Francis, D.J., & Fletcher, J. M. (2011). An experimental study of scheduling and duration of ”Tier 2” first-grade reading intervention. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 4(3), 208–230. doi:10.1080/19345747.2010.530127

- *Denton, C. A., Fletcher, J. M., Taylor, W. P., Barth, A. E., & Vaughn, S. (2014). An experimental evaluation of Guided Reading and explicit interventions for primary-grade students at-risk for reading difficulties. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 7(3), 268–293.

- *Denton, C. A., Kethley, C., Nimon, K., Kurz, T. B., Mathes, P., Minyi, S., & Swanson, E. A. (2010). Effectiveness of a supplemental early reading intervention scaled up in multiple schools. Exceptional Children, 76(4), 394–416.

- *Foorman, B. R., Herrera, S., & Dombek, J. (2018). The relative impact of aligning Tier 2 intervention materials with classroom core reading materials in Grades K–2. Elementary School Journal, 118(3), 477–504.

- *Gallagher, A. L., & Chiat, S. (2009). Evaluation of speech and language therapy interventions for pre-school children with specific language impairment: A comparison of outcomes following specialist intensive, nursery-based and no intervention. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 44(5), 616–638.

- *Gilbert, J. K., Compton, D. L., Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., Bouton, B., Barquero, L. A., & Cho, E. (2013). Efficacy of a first-grade Responsiveness-to-Intervention prevention model for struggling readers. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(2), 135–154.

- *Goldstein, H., Kelley, E., Greenwood, C., McCune, L., Carta, J., Atwater, J., … Spencer, T. (2016). Embedded instruction improves vocabulary learning during automated storybook reading among high-risk preschoolers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 59(3), 484–500.

- *Haley, A., Hulme, C., Bowyer-Crane, C., Snowling, M. J., & Fricke, S. (2017). Oral language skills intervention in pre-school-a cautionary tale. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 52(1), 71–79.

- *Helf, S., Cooke, N. L., & Flowers, C. P. (2009). Effects of two grouping conditions on students who are at risk for reading failure. Preventing School Failure, 53(2), 113–128.

- *Helf, S., Cooke, N., & Konrad, M. (2014). Advantages of providing structured supplemental reading instruction to kindergarteners at risk for failure in reading. Preventing School Failure, 58(4), 214–222.

- *Horne, J. K. (2017). Reading comprehension: A computerized intervention with primary-age poor readers. Dyslexia: An International Journal of Research and Practice, 23(2), 119–140.

- *Hudson, R. F., Isakson, C., Richman, T., Lane, H. B., & Arriaza-Allen, S. (2011). An examination of a small-group decoding intervention for struggling readers: Comparing accuracy and automaticity criteria. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 26(1), 15–27.

- *Hund-Reid, C., & Schneider, P. (2013). Effectiveness of phonological awareness intervention for kindergarten children with language impairment. Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, 37(1), 6–25.

- *Kamps, D., Abbott, M., Greenwood, C., Wills, H., Veerkamp, M., & Kaufman, J. (2008). Effects of small-group reading instruction and curriculum differences for students most at risk in kindergartenL: Two-year results for secondary- and tertiary-level interventions. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41(2), 101–114.

- *Kelley, E. S., Goldstein, H., Spencer, T. D., & Sherman, A. (2015). Effects of automated Tier 2 storybook intervention on vocabulary and comprehension learning in preschool children with limited oral language skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 31, 47–61.

- *Kerins, M. R., Trotter, D., & Schoenbrodt, L. (2010). Effects of a Tier 2 intervention on literacy measures: Lessons learned. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 26(3), 287–302.

- *Lee, W., & Pring, T. (2016). Supporting language in schools: Evaluating an intervention for children with delayed language in the early school years. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 32(2), 135–146.

- *Little, M. E., Rawlinson, D., Simmons, D. C., Kim, M., Kwok, O., Hagan-Burke, S., … Coyne, M. D. (2012). A comparison of responsive interventions on kindergarteners’ early reading achievement. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 27(4), 189–202.

- *Lonigan, C. J., & Phillips, B. M. (2016). Response to instruction in preschool: Results of two randomized studies with children at significant risk of reading difficulties. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(1), 114–129.

- *Lovett, M. W., Frijters, J. C., Wolf, M., Steinbach, K. A., Sevcik, R. A., & Morris, R. D. (2017). Early intervention for children at risk for reading disabilities: The impact of grade at intervention and individual differences on intervention outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(7), 889–914.

- *Madden, N. A., & Slavin, R. E. (2017). Evaluations of technology-assisted small-group tutoring for struggling readers. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 33(4), 327–334.

- *Morris, R. D., Lovett, M. W., Wolf, M., Sevcik, R. A., Steinbach, K. A., Frijters, J. C., & Shapiro, M. B. (2012). Multiple-component remediation for developmental reading disabilities: IQ, socioeconomic status, and race as factors in remedial outcome. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45(2), 99–127.

- *Nielsen, D., & Friesen, L. D. (2012). A study of the effectiveness of a small-group intervention on the vocabulary and narrative development of at-risk kindergarten children. Reading Psychology, 33(3), 269–299.

- *Oostdam, R., Blok, H., & Boendermaker, C. (2015). Effects of individualised and small-group guided oral reading interventions on reading skills and reading attitude of poor readers in grades 2–4. Research Papers in Education, 30(4), 427–450.

- *Phillips, B. M., Tabulda, G., Ingrole, S. A., Burris, P., Sedgwick, T., & Chen, S. (2016). Literate language intervention with high-need prekindergarten children: A randomized trial. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 59(6), 1409–1420.

- *Pollard-Durodola, S. D., Gonzalez, J. E., Simmons, D. C., Kwok, O., Taylor, A. B., Davis, M. J., … Simmons, L. (2011). The effects of an intensive shared book-reading intervention for preschool children at risk for vocabulary delay. Exceptional Children, 77(2), 161–183.

- *Puhalla, E. M. (2011). Enhancing the vocabulary knowledge of first-grade children with supplemental booster instruction. Remedial and Special Education, 32(6), 471–481.

- *Pullen, P. C., & Lane, H. B. (2014). Teacher-directed decoding practice with manipulative letters and word reading skill development of struggling first grade students. Exceptionality, 22(1), 1–16.

- *Pullen, P. C., Tuckwiller, E. D., Konold, T. R., Maynard, K. L., & Coyne, M. D. (2010). A tiered intervention model for early vocabulary instruction: The effects of tiered instruction for young students at risk for reading disability. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 25(3), 110–123.

- *Ritter, M. J., Park, J., Saxon, T. F., & Colson, K. A. (2013). A phonologically based intervention for school-age children with language impairment: Implications for reading achievement. Journal of Literacy Research, 45(4), 356–385.

- *Roskos, K., & Burstein, K. (2011). Assessment of the design efficacy of a preschool vocabulary instruction technique. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 25(3), 268–287.

- *Ryder, J. F., Tunmer, W. E., & Greaney, K. T. (2008). Explicit instruction in phonemic awareness and phonemically based decoding skills as an intervention strategy for struggling readers in whole language classrooms. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 21(4), 349–369.

- *Schuele, C. M., Justice, L. M., Cabell, S. Q., Knighton, K., Kingery, B., & Lee, M. W. (2008). Field-based evaluation of two-tiered instruction for enhancing kindergarten phonological awareness. Early Education and Development, 19(5), 726–752.

- *Schwartz, R. M., Schmitt, M. C., & Lose, M. K. (2012). Effects of teacher-student ratio in Response to Intervention approaches. Elementary School Journal, 112(4), 547–567.

- *Senechal, M., Ouellette, G., Pagan, S., & Lever, R. (2012). The role of invented spelling on learning to read in low-phoneme awareness kindergartners: A randomized-control-trial study. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 25(4), 917–934.

- *Simmons, D. C., Coyne, M. D., Hagan-Burke, S., Kwok, O., Simmons, L., Johnson, C., … Crevecoeur, Y. C. (2011). Effects of supplemental reading interventions in authentic contexts: A comparison of kindergarteners’ response. Exceptional Children, 77(2), 207–228.

- *Simmons, D. C., Taylor, A. B., Oslund, E., Simmons, L. E., Coyne, M. D., Little, M. E., … Kim, M. (2014). Predictors of at-risk kindergarteners’ later reading difficulty: Examining learner-by-intervention interactions. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 27(3), 451–479.

- *Smith, J. L. M., Nelson, N. J., Smolkowski, K., Baker, S. K., Fien, H., & Kosty, D. (2016). Examining the efficacy of a multitiered intervention for at-risk readers in Grade 1. The Elementary School Journal, 116(4), 549–573.

- *Spencer, T. D., Petersen, D. B., & Adams, J. L. (2015). Tier 2 language intervention for diverse preschoolers: An early-stage randomized control group study following an analysis of Response to Intervention. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24(4), 619–636.

- *Torgesen, J. K., Wagner, R. K., Rashotte, C. A., Herron, J., & Lindamood, P. (2010). Computer-assisted instruction to prevent early reading difficulties in students at risk for dyslexia: Outcomes from two instructional approaches. Annals of Dyslexia, 60(1), 40–56.

- *Vadasy, P. F., & Sanders, E. A. (2008a). Code-oriented instruction for kindergarten students at risk for reading difficulties: A replication and comparison of instructional groupings. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 21(9), 929–963.

- *Vadasy, P. F., & Sanders, E. A. (2008b). Repeated reading intervention: Outcomes and interactions with readers’ skills and classroom instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 272–290.

- *Westerveld, M. F., & Gillon, G. T. (2008). Oral narrative intervention for children with mixed reading disability. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 24(1), 31–54.

- *Wonder-mcdowell, C., Reutzel, D. R., & Smith, J. A. (2011). Does instructional alignment matter?: Effects on struggling second graders’ reading achievement. Elementary School Journal, 112(2), 259–279.

- *Zucker, T. A., Solari, E. J., Landry, S. H., & Swank, P. R. (2013). Effects of a brief tiered language intervention for prekindergartners at risk. Early Education and Development, 24(3), 366–392.

- Adolf, S. M., & Hogan, T. P. (2019). If we don’t look, we won’t see: Measuring language development to inform literacy instruction. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 6(2), 210–217.

- Australian Disability Clearinghouse on Education and Training. (n.d.). Learning difficulty versus learning disability. Retrieved August 24, 2020, from https://www.adcet.edu.au/disability-practitioner/reasonable-adjustments/disability-specific-adjustments/specific-learning-disability/learning-difficulty-versus-learning-disability/

- Bishop, D. V. M., & Snowling, M. J. (2004). Developmental dyslexia and specific language impairment: Same or different? Psychological Bulletin, 130(6), 858886.

- Bond, C., Wood, K., Humphrey, N., Symes, W., & Green, L. (2013). Practitioner review: The effectiveness of solution focused brief therapy with children and families: A systematic and critical evaluation of the literature from 1990-2010. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(7), 707–723.

- Buckingham, J. K. W., Wheldall, K., & Beaman-Wheldall, R. (2013). Why Jaydon can’t read: The triumph of ideology over evidence in teaching reading. Policy: A Journal of Public Policy and Ideas, 29(3), 21. Retrieved August 24, 2020, from https://www.cis.org.au/app/uploads/2015/04/images/stories/policy-magazine/2013-spring/29-3-13-jennifer-buckingham.pdf

- Castles, A., Rastle, K., & Nation, K. (2018). Ending the reading wars: Reading acquisition from novice to expert. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 19(1), 5–51.

- CEBC. (2016). The California evidence-based clearinghouse scientific rating scale. Retrieved August 24, 2020, from https://www.cebc4cw.org/files/OverviewOfTheCEBCScientificRatingScale.pdf

- Conti-Ramsden, G., & Botting, N. (2008). Emotional health in adolescents with and without a history of specific language impairment (SLI). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(5), 516–525.

- Cronin, P., Reeve, R., McCabe, P., Viney, R., & Goodall, S. (2020). Academic achievement and productivity losses associated with speech, language and communication needs. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 55(5), 734–750.

- Dickinson, D. K., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2010). Speaking out for language: Why language is central to reading development. Educational Researcher, 39(4), 305–310.

- Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, L. M. (1997). Peabody picture vocabulary test–third edition. Bloomington, MN: Pearson Assessments.

- Eadie, P., Conway, L., Hallenstein, B., Mensah, F., McKean, C., & Reilly, S. (2018). Quality of life in children with developmental language disorder. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 53(4), 799–810.

- Eadie, P., Nguyen, C., Carlin, J., Bavin, E., Bretherton, L., & Reilly, S. (2014). Stability of language performance at 4 and 5 years: Measurement and participant variability. International Journal of Speech Language Pathology, 49(2), 215–227.

- Ehri, L., Nunes, S., Stahl, S., & Willows, D. (2001). Systematic phonics instruction helps students learn to read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel’s meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 71(3), 393–447.

- Ehri, L., Nunes, S., Willows, D., Schuster, B., Yaghoub-Zadeh, Z., & Shanahan, T. (2001). Phonemic awareness instruction helps children learn to read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel’s meta-analysis. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(3), 250–287.

- Elbaum, B., Vaughn, S., Tejero Hughes, M., & Watson Moody, S. (2000). How effective are one-to-one tutoring programs in reading for elementary students at risk for reading failure? A meta-analysis of the intervention research. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(4), 605–619.

- Fien, H., Nelson, N. J., Smolkowski, K., Kosty, D., Pilger, M., Baker, S. K., & Smith, J. L. M. (2020). A conceptual replication study of the enhanced core reading instruction MTSS-reading model. Exceptional Children, 87(3), 265–288.

- Fuchs, D., Compton, D. L., Fuchs, L. S., Bryant, J., & Davis, G. N. (2008). Making “secondary intervention” work in a three-tier responsiveness-to-intervention model: Findings from the first-grade longitudinal reading study of the national research center on learning disabilities. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 21(4), 413–436.

- Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., & Vaughn, S. (2008). Response to intervention. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

- Fuchs, D., & Fuchs, L. S. (2006). Introduction to Response to Intervention: What, why, and how valid is it? Reading Research Quarterly, 41(1), 93–99.

- Gakidou, E., Cowling, K., Lozano, R., & Murray, C. J. L. (2010). Increased educational attainment and its effects on child mortality in 175 countries between 1970 and 2009: A systematic analysis. The Lancet, 376(9745), 959–974.

- Ganann, R., Ciliska, D., & Thomas, H. (2010). Expediating systematic reviews: Methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implementation Science, 5(1), 56.