ABSTRACT

Political polarization in the United States has spilled over into issues that were not previously aligned on partisan sides, especially with regard to scientific expertise. People take cues from elites and as a result, alter their preferences based on those elite cues. In particular, self-identified Republicans and conservatives are more suspicious of scientists and academics, and more likely to dismiss or disbelieve scientific findings. We apply these findings in the context of attitudes about concussion-related injuries in sports. We theorize that groups predisposed against academics and scientists will be less likely to believe in connections between head injuries and organized sports. Using a nationally representative survey conducted in 2016, we find strong support for our theory. There is widespread of acceptance that concussions and head injuries are a problem in sports with 65% saying they are a major problem and 29% saying minor problem. Attitudes about the dangers of traumatic brain injuries and acceptance of new scientific findings are divided by party identification, especially among those with the highest levels of political knowledge. Further, attitudes about new science on concussions are related to attitudes about climate change. These findings have broad implications for how scientific issues are politicized in the United States in the contemporary era.

Introduction

The level of polarisation in American politics has grown substantially in the last half-century. Some scholars claim that we now occupy a space where objective facts are ceasing to exist (Hochschild and Einstein Citation2015). Democrats and Republicans do not merely disagree on politics, but on the basic facts underlying those politics. The source of this is motivated reasoning, where biased information gatherers evaluate new pieces of information with extreme prejudice in order to support preconceived attitudes. The result can be so powerful that repetition of negative information can have positive effects (e.g. Redlawsk Citation2002, Druckman et al. Citation2013, Berinsky Citation2017). That is, as information that demonstrates scientific findings makes its way into the information environment, this can, in some instances, strengthen anti-scientific arguments (Nyhan et al. Citation2014).

Motivated reasoning is thought to exist because of the way that cognitively miserly citizens construct their political attitudes. The central actors in this model are political elites who signal the ‘correct’ attitudes to the mass public through position-taking and information dissemination through the media (e.g. Popkin Citation1991, Lupia Citation1994). Political sophistication is seen as vital to the ability of members of the mass public to follow elite cue-giving (Zaller Citation1992, Layman and Carsey Citation2002); this explains, to a degree, why there is considerably more evidence of elite polarisation than mass polarisation (Hetherington Citation2001, Levendusky Citation2010, but see Campbell Citation2016).

In this paper, we argue that continued dismissals of science and academia among Republican elites should lead to spillover effects; that is, polarised attitudes on the general believability of the scientific and academic community can lead to differential levels of scepticism on issues that are apolitical. In the past decade, emerging research on brain injuries has focused on Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), the study of the deteriorative effects of repeated trauma to the brain (e.g. Omalu et al. Citation2005, McKee et al. Citation2009). That the study of CTE involved sports athletes landed it on the front page of newspapers in the United States. The interest of sports journalists in this topic only intensified as connections were made between CTE and the high-profile suicides of athletes from the National Football League, National Hockey League, World Wrestling Entertainment, and others (Gerson Citation2017). While media coverage of brain injuries and concussions has certainly intensified, these issues have not created any kind of stir among political elites; that is, there is no evidence that Democratic or Republican elites have fixed, opposite positions on the role of CTE in sports. However, we theorise that in the absence of cues about policy views from political elites, individuals are likely to use previously developed political predispositions on science more generally; these predispositions should be activated among the most politically aware respondents. Using an original dataset of 1000 American adults, we find strong support for this theory. Attitudes about the dangers of brain injuries and acceptance of newly reported scientific findings by the media are divided by party identification, political ideology and personal values. Additionally, party identification differences are the greatest among those with the highest levels of political awareness.

The implications of the spillover of motivated reasoning and its affect in the formation of public opinion is important to understanding how scientific information as it emerges and enters the public can be understood and consumed, and under what circumstances it might be resisted. The science on CTE is still very new and as we learn more in the next decade, the dissemination of that information will face the challenge of managing any efforts at countermobilisation of information. As of right now, even in what we would term to be a one-sided media information environment in the United States, latent scepticism about science related to other policy attitudes is being activated in the consideration of understanding new information.

Motivated reasoning, facts, and anti-science attitudes

There are gaps between what scientists believe based on an understanding of the preponderance of scientific evidence and what the public believes on those same issues. The gaps are evident on issues like climate change, evolution, embryonic stem-cell research, and the effectiveness of sex education. For a time, many in the scientific community believed that these differences were due to an education or information gap; scientists held different perspectives than the general public because they knew more about the scientific findings. Presumably, this means that greater education about science and scientific consensus would bring public understandings into alignment with the perspectives of the scientific community.

This model, commonly termed the deficit model, has recently been replaced by insights from political communication scholars, who argue that individuals respond to information about scientific discovery using motivated reasoning (Hart and Nisbet Citation2012). The key to understanding how motivated reasoning works is knowing that most individuals use affect to develop opinions on political matters (Redlawsk Citation2002). That is, an individual processes new information through existing filters, rejecting new pieces of information that are inconsistent with their priors. Information is only persuasive insofar as an individual receives that piece of information, accepts it, and then accesses that piece of information through a stochastic process through which recent considerations are given greater weight (Zaller Citation1992, Zaller and Feldman Citation1992).

Partisan identity, elite cues and political sophistication play a large role in this process. Individuals use their party identification, a self-identification cue that is normally acquired early in life and stays quite stable over the life-cycle (Green et al. Citation2002) to filter information. By so doing, they rely on political elites to communicate information that tells them which positions support their political identity. Individuals with higher levels of political awareness, therefore, are more in tune with elite cues and tend to have better organised cognitive maps. While they consume the most information, they also are most adept at filtering and sorting that information to reinforce their pre-existing positions (Zaller Citation1992). Partisan rejection of information that challenges predispositions is so strong, that many scholars report a sort of ‘boomerang’ effect, where inconsistent information hardens and deepens polarisation (Hart and Nisbet Citation2012). This can happen on single issues (Hart and Nisbet Citation2012) or it can happen by extending polarisation across a series of issues, some of which individuals were previously ambivalent about (Layman and Carsey Citation2002).

One area where elite position-taking has rapidly increased in the past decade is on the issue of climate change. Climate change belongs to a set of issues including stem-cell research and evolution where scientific consensus is met by partisan politics. The division on these issues is not about which policy is best but rather about (1) whether there is any scientific consensus, and (2) if scientists are to be trusted (Nisbet and Mooney Citation2007). Much of this disbelief in scientific consensus is fuelled by traditional elite framing, where elites supply information through increasingly narrow and partisan media outlets (Prior Citation2007). But on climate change (as well as evolution and stem cell research), the scientific community is aligned with Democrats and opposed by Republicans.

In the motivated reasoning literature, it is thought that elites move first. That is, in the attitude space that precedes elite cueing, we would not necessarily expect a partisan dimension to apolitical issues, and we also would not expect informational differences. That motivated reasoning extends to scientific discovery shows the special power of the human mind to draw conclusions that support existing predispositions. Especially emblematic in this debate are attitudes on the issue of climate change. On issues that conflict with religious values like stem-cell research and sex education, perhaps we should not be so surprised to find motivated reasoning guiding policy considerations and negating the findings of scientific research. This is because attitude change on these issues would conflict with core values and/or religiosity. But what core value is at stake in the debate on the existence or lack of a scientific consensus on climate change? The politicised reaction to scientific consensus has not simply been about climate change, but has been part of a pushback to colleges, universities and the liberal slant in academia (Gross Citation2013). As it turns out, college faculty are considerably more likely to identify as Democrats than the public, a fact which has led to an imbalance in trust in what scientists say (see Grossmann and Hopkins Citation2016, p. 146).

Arguments against science and universities have clearly made their way into the information environment as part of a concerted effort from conservative elites (Grossmann and Hopkins Citation2016, Ch. 4). If the frame that is used to justify beliefs against climate change are because scientists are biased, it stands to reason that on other apolitical issues, even without prompts from political elites, highly aware partisans would use the same framework to evaluate a new piece of information. Therefore, the effects of the politicisation of issues like climate change may extend beyond the bounds of issues that are actually in the information environment. We would expect it to include issues of science that media elites have yet to polarise on.

There is little evidence of elite partisan signalling on the connections between professional contact sports like American football and head injuries. While it is difficult to definitively prove a negative, many of the empirical measures that indicate elite preference signalling on other issues are absent in the case of the links between organised sports and head injuries. At the national level, neither the Democratic nor Republican party platforms mentioned the terms concussion, head injury, or American football in 2016, 2012, or 2008. This is also true in the states, which govern both public university systems and athletic leagues.Footnote1 Policies that limit contact sports by age or require public institutions to embrace scientifically-based concussion protocol have been adopted by large bipartisan coalitions in all 50 states (Lowrey Citation2015). BrainPAC, the political action committee organised by the American Association of Neurology to lobby for these policies, endorses and contributes to both Republicans and Democrats (Albin et al. Citation2016). This combination of factors should create an environment where partisan identification does not predict preferences on the links between organised sports and head injuries.

Head injuries, CTE, and the sports news media

While concussions have clearly not received much attention from political elites and political media, there has been widespread coverage by the sports media of the link between playing sports, especially American football, and long-term complications associated with repeated head injuries. In 2005, Dr. Bennet Omalu, a neuropathologist, discovered evidence of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Mike Webster of the Pittsburgh Steelers (Omalu et al. Citation2005). Editors and reporters from ESPN and The New York Times began to cover the story extensively; in fact, in a five-year period, The New York Times sports reporter Alan Schwarz wrote 120 articles on the concussion issue.

Coverage began to snowball. While The New York Times focused on scientific findings emerging regarding CTE, Mark Fainaru-Wada and Steve Fainaru of ESPN were at the centre of writing on the response to new evidence by sports organisations, especially the NFL.Footnote2 Roger Goodell and NFL officials continued to deny that there were any long-term issues related to repeated concussions (Nowinski Citation2006). Fainaru-Wada and Fainaru's reporting eventually led to the publication of League of Denial (Citation2013) and a subsequent documentary of the same name by PBS. In 2015, Hollywood joined the fray with a movie starring Will Smith chronicling Omalu’s discovery of CTE, and the subsequent and aggressive pushback by NFL lawyers and physicians. By 2015, the NFL was changing its tune, admitting that there was a link between on-field concussions and CTE, and settling a lawsuit to the tune of one billion dollars with former players.

Interestingly, while the science regarding concussions, CTE, and their link has received a great deal of attention from the media, we would not say, for instance, that concussions and CTE has advanced to the same level of scientific acceptance as an issue like climate change. For instance, in 2016, a group of scientists released the ‘Consensus statement on concussion in sport – the 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016’ (McCroy et al. Citation2017). While in the report they make a number of best practice recommendations on treating concussions in sports, they ultimately conclude that,

The literature on neurobehavioral sequelae and long-term consequences of exposure to recurrent head trauma is inconsistent. Clinicians need to be mindful of the potential for long-term problems such as cognitive impairment, depression, etc. in the management of all athletes. However, there is much more to learn about the potential cause-and-effect relationships of repetitive head-impact exposure and concussions. The potential for developing chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) must be a consideration, as this condition appears to represent a distinct tauopathy with an unknown incidence in athletic populations. A cause-and-effect relationship has not yet been demonstrated between CTE and SRCs [sports-related concussions] or exposure to contact sports. As such, the notion that repeated concussion or sub-concussive impacts cause CTE remains unknown. (p. 844)

In essence, the scientific consensus on the link between concussions and CTE is that there is not yet a scientific consensus, but rather a suggestive link – what the Consensus Report calls ‘a distinct tauopathy with an unknown incidence in athletic populations.’ To give a sense of how this field is evolving, some recent research has in fact suggested that CTE is caused by repeated hits to the head and not necessarily concussions (Tagge et al. Citation2018).

But while we might characterise this scientific field as new and evolving, it does not alter our prediction. Given that the media mechanism that has publicised scientific findings on CTE and concussions has been one-sided, members of the public who are exposed to this information through the sports pages of newspapers, documentaries, ESPN specials, or through watching a feature film starring Will Smith are provided relatively static information about emerging scientific evidence that they can either choose to believe or not believe. Ultimately, our question is whether partisan-motivated reasoning and belief about climate change affect the acceptance of that information.Footnote3

Modelling attitudes about head injuries in sports

Data

So, how exactly has the public reacted to reports that football related concussions can lead to CTE? We collected a nationally representative original dataset of 1000 American adultsFootnote4 in May of 2016 to examine American attitudes towards concussions, CTE, and American football. We found a surprisingly high level of awareness about CTE and high levels of concern about the safety of playing sports; frequency distributions are presented in . For instance, 65 percent of respondents viewed concussions or head injuries in sports as a ‘major problem’, 29 percent said a ‘minor problem’ and only 6 percent said ‘not much of a problem’ or ‘not a problem at all’. Similarly, 87 percent of respondents noted that CTE is a public health issue. A large majority also said that it was either ‘certainly true’ (31%) or ‘probably true’ (54%) that ‘playing [American] football can cause a progressive degenerative brain disease called Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy or “CTE”.Footnote5 Only 37 percent said that it was either ‘certainly true’ (6%) or ‘probably true’ (31%) that tackle football is a safe activity for children before they reach high school, and only a slim majority (52%) said that it is certainly true (7%) or probably true (45%) that tackle football is a safe activity for children during high school. Finally, when asked about the NFL’s response, only 22% said the league had made appropriate changes, 43% said they had not done enough, 4% said they had done too much, and 31% were uncertain. On the specific issue of whether there was a ‘settled science’ that playing American football causes CTE, a large majority (85%) said that it was either probably true (54%) or certainly true (31%).

Table 1. Frequency distributions of various measures of attitudes about concussions and sports.

Analytical strategy

While there is clear evidence, then, of widespread concern about head injuries in American football, and clear willingness to accept emerging science about this issue, we are most interested in the underlying variation that explains willingness to accept science. From our theory, we can test the hypothesis that motivated reasoning can be present on apparently apolitical issues because anti-science attitudes are already prevalent in the public discourse. We test this hypothesis in two ways. First, we can examine the interactive effect of party identification and political awareness on attitudes on 6 concussion-related issues:

1. Attitudes about how much of a problem concussions are in sports

2. Belief that CTE is a public health issue

3. Belief that playing American football can cause CTE

4. Approval of children playing American football

5. Belief that American football is an appropriate activity for children before high school

6. Belief that American football is an appropriate activity for children during high school

In addition, our survey also includes an item about climate change where respondents were asked one of two questions about their certainty that climate change is caused by human activity.Footnote6 We can therefore incorporate this variable into a second set of models to see if attitudes about belief in the science surrounding climate change impact attitudes about belief in the science surrounding CTE.

We measure political awareness by constructing a scale that ranges from 0 to 5 based on answers to 5 factual questions about general politics. The questions included ability to recognise the job title of Paul Ryan (the Speaker of the US House of Representatives), David Cameron (the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom), and John Roberts (the Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court), as well as the ability to correctly identify which political party had the majority of seats in the US House of Representatives (Republicans) and Senate (Republicans).Footnote7 A five-question scale like this has been used in numerous studies in political science (Luskin Citation1987; Zaller Citation1992). Importantly, the questions scale quite well. The modal outcome is a score of 0 (26% of the sample). Another 14% get 1 correct answer, 17% get 2 correct, 13% get 3 correct, 12% get 4 correct, and 18% get all 5 correct. The standardised Cronbach’s alpha among the five items is .816. A principal components factor analysis on the five items returns a single eigenvalue greater than 1 at 2.88 with unrotated factor loadings for the 5-items ranging between .73 and .78. All of this indicates, consistent with the literature, that the items are highly scalable and that this scale is highly reliable as a measure of political awareness/sophistication.

In consideration of plausible rival theories, it is plausible that while cues are not coming from political parties or opinion leaders that any differences in acceptance of CTE may be due to a variety of cultural factors that relate to social/cultural values and American football or sports more generally. American football, especially high school and college football, varies in its importance as a social institution throughout the United States. This identity and the values associated with ‘Friday Night Lights’ is especially prevalent in the South and in many communities (often small towns) throughout the Midwest that we would associate with conservativism (Riesman and Denney Citation1951, Rooney Citation1969, Nisbett and Cohen Citation1996). It is also possible attitudes towards CTE and concussions will reflect the underlying conservatism of sports fandom. Under this scenario, we would expect that conservatives might be reluctant to offer sympathetic views towards athletes injured in the course of playing American football because of their conservative ideological views about individualism, self-reliance, and labour market protections. Much of these views may also be tied to views on race (Hartmann Citation2007).

In an effort to control for these ideological and cultural factors, we include measures of political ideology, and include a set of fixed effects for the 9 US regions defined by the US Census. We are also able to control expressly for personal values using the Schwartz value scale (Schwartz Citation1992).Footnote8 The model therefore includes four items, each scaled from zero to one of the four main Schwartz value components: self-transcendence, openness to change, self-enhancement, and conservation. Goren et al. (Citation2016) have argued that two central personal values – self-enhancement (which includes universalism and benevolence) and conservation (which includes tradition, conformity and security) – predict most policy attitudes. The questions used in the creation of the Schwartz value scale are available in the Appendix. Including measures of political ideology, and personal values, allows for greater confidence in any observed effects of the party ID/awareness interaction.

There are also several individual factors that might predict belief in scientific findings about head injuries and concussions. These include gender, age and its square, race/ethnicity, level of education, and family income. In addition, we are able to control for the extent to which an individual is a sports fan (measured by frequency of watching on TV) and the extent to which American football is the sport they are most likely to watch. We also control for whether the respondent knows anyone who has suffered from post-concussion syndrome.

We report on specifics on measurement and coding of all the independent variables included in our models in .

Table 2. Measurement and Descriptive Statistics of Independent Variables Used in Models.

Our six dependent variables fit into two natural groupings. The first set of questions asks directly about individual attitudes about concussions, head injuries, and/or CTE in sports, while the second set of questions asks about approval and safety of American football for children. Our theory would suggest the greatest difference between knowledgeable partisans and/or those who are sceptical that climate change is caused by human activity. However, to the extent that head injuries, concussions, and safety play into attitudes about whether children should participate in sports, we would also expect a divergence in attitudes among informed partisans. To be sure, the distance between theory and measures is further apart on this second set of variables. All of the dependent variables that we use to test attitudes about CTE, concussions in sports, and attitudes about the safety of youth American football were measured using 3 or 4-point Likert scales. Therefore, we estimate ordered logit models for each dependent variable with an adjustment for the survey weights calculated in each estimated model.

Results

The results of the three models, estimated to gauge opinions on (1) concussions and sports, (2) CTE as a public health issues, and (3) whether there is a settled science that playing American football can lead to brain injuries/CTE, are presented in . Perhaps the most interesting finding is that the only variables that are consistently significant in predicting variation in attitudes about concussions in sports are the interaction effects of party X knowledge and personal experience with a concussion (6% of the sample). There is no consistent effect for differences by gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, or income. Even for political ideology, which is significant in model 2, but not models 1 or 3, the effect of party identification and knowledge appear to crowd out any independent effect. In addition, personal values are not predictive of variation in attitudes about head injuries.

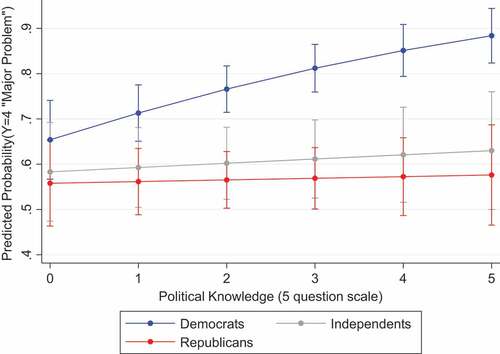

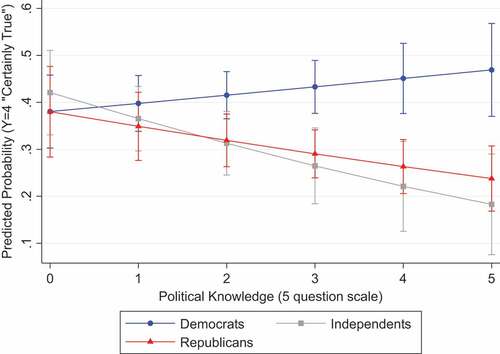

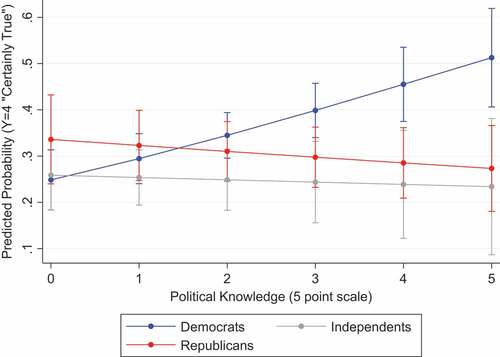

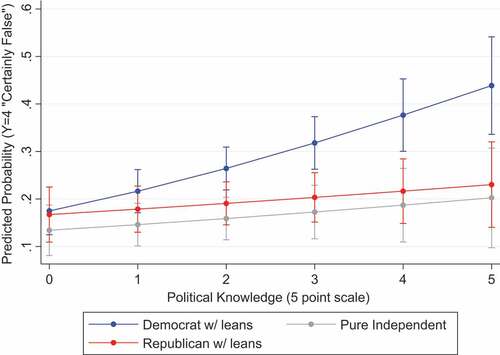

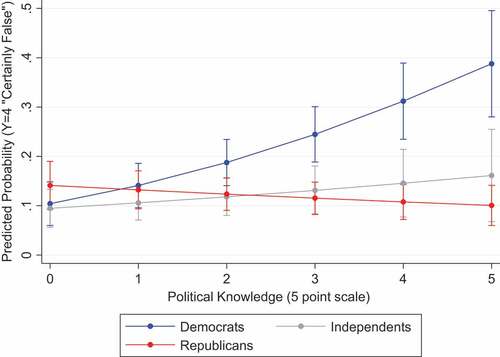

The substantive differences of the party/knowledge interaction are presented in –. These are calculated as changes in predicted probabilities, holding all other values constant at their mean values. Each of the 3 figures follows a similar pattern. The predicted probability for Democrats and Republicans is not statistically different at low levels of political knowledge, but they begin to diverge as you move across the scale. On the question of whether concussions are a problem in sports, the predicted probability of saying ‘major problem’ for highly knowledgeable Democrats is 88 percent, while the probability for highly knowledgeable Republicans is 58 percent, a 30-percentage point difference. The predicted probability that highly informed Democrats respond that it is ‘certainly true’ that CTE is a public health issue is 48 percent, compared to only 25 percent of Republicans who give the same response, a 23-percentage point difference. Similarly, the model predicts a 51 percent probability that Democrats respond that it is ‘certainly true’ that there is a settled science that American football causes brain injuries/CTE compared to only 27 percent for Republicans, a 24-percentage point difference.

Figure 1. Party ID X knowledge interaction, ‘Concussions are a major problem’.

Figure 2. Party ID X knowledge interaction, ‘CTE is a public health issue’.

Figure 3. Party ID X knowledge interaction, ‘Settled science’.

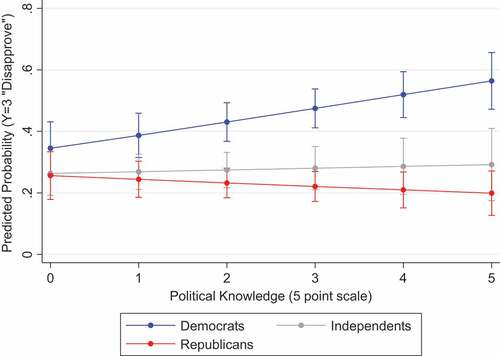

We present the results of 3 additional ordered logit models in ; the dependent variables in these models are three measures of attitudes about children participating in American football activities. Model 4 estimates citizen approval of children playing tackle American football, and Models 5 and 6 consider whether individuals view American football as a safe activity before high school and during high school, respectively. Again, we see an unremarkable effect for most of the individual level controls in the model, except for gender. In all three models, women are more likely than men to disapprove of children playing American football, and also more likely to say that it is ‘certainly false’ that American football is a safe activity for children before or during high school. This is interesting as we do not see a general gender effect across all the models about attitudes towards sport, but rather in the models that specifically address the role of children in sport. However, in each case we see a significant interaction effect between party identification and political knowledge with magnitudes similar to those presented in the previous models. These substantive effects are presented in –. In all 6 cases, then, we see a significant difference in attitudes towards the safety of American football and belief in the science surrounding head injuries and CTE for informed Republicans and Democrats.

Figure 4. Party ID X knowledge interaction, ‘Disapprove of children playing tackle football’.

Figure 5. Party ID X knowledge interaction, ‘Tackle football is safe before high school’.

Figure 6. Party ID X knowledge interaction, ‘American tackle football is safe during high school’.

While this effect is consistent with the theory presented, that apolitical attitudes are polarised because of the rhetoric surrounding polarisation, belief in science, and academia, it also does not provide a direct test of the theory. To address this concern, we present additional models in and that amend the previous 6 models by adding an item about belief in climate change. In each and every instance, the variable for belief in climate change is significantly related to belief in CTE and concern about head injuries in tackle American football. We summarise the substance of these effects in . For instance, in the first panel of , we show that the probability of viewing concussions as a major problem are .75 for those who belief that climate change is certainly caused by humans and .50 for those who believe that climate change is certainly not caused by humans, a difference of 25 percentage points. The probability change is similar for the view that CTE is a public health issues (22 percentage point change) and the view that there is a settled science that playing American football causes CTE (15 percentage point change). Smaller, but significant effects of 10 points are larger also exist for the questions about children playing American football.

Figure 7. Effect of climate change attitudes on concussion/CTE attitudes.

To be sure, we lack a definitive causal test of the theory, but the empirical models presented provide consistent and clear evidence that attitudes about CTE, concussions, and the safety of American football are interconnected with party identification and political knowledge in a manner that mirrors findings on motivated reasoning. Additionally, these apolitical attitudes are also clearly linked to other attitudes about science, notably those that have to do with belief that climate change is or is not caused by humans.

Conclusion

Motivated partisan reasoning is a well-established reality of modern polarised American society. Policy attitudes revealed as preferences by members of the public are often quite shallow, if rooted at all. Because of this, partisan cues play a particularly large role in the development of policy attitudes, and can also explain rapid change on an issue when elites position-take or switch sides. Less explored is what effect partisan polarisation and the arguments surrounding the acquisition of facts and knowledge through science have on attitudes towards scientific findings that have not been polarised by political elites. We find that on one such issue, belief about the science surrounding chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, elite position-taking is absent in the information environment and yet policy attitudes are polarised in a manner consistent with motivated reasoning.

Informed partisans have statistically different views on the existence of CTE, the relationship of CTE to public health and American football, and the overall safety of America’s most popular sport. These attitudes also appear to be directly linked to attitudes about climate change. What does it mean for an apolitical issue to be polarised? We are limited to the set of issues surrounding CTE and therefore cannot generalise widely. However, what the findings presented herein suggest is that the content of policy debates, particularly those that draw upon alternative facts and seek to discredit the scientific community and academia in a specific area, like climate change, may have reverberating effects on individuals’ propensities to accept other scientific findings. Perhaps the most surprising finding here is how widespread the acceptance the link between sport concussions and CTE is in the mass public. Although, given the widespread media coverage on the issue, declining rates of youth tackle American football participation, and movements by lawmakers to ban American football for children under 14 in some states, perhaps this should not come as too much of a surprise.

One of the obvious questions for future research to grapple with is if we have identified a US only phenomenon. Some recent research has suggested that partisan motivated reasoning, particularly the act of expressive partisanship, is common in European democracies: The United Kingdom, Netherlands, Sweden, and Italy (Huddy et al. Citation2018). So, under the circumstances that issues of sport and/or science (and their intersection) are politicised, we think the findings here may have broader impact than just in the United States. Furthermore, the United States has also seen the most aggressive media reporting of CTE and concussions in sport; so much so, that this reporting has forced the National Football League to admit a link between concussions and CTE before there is an established scientific consensus. This is an interesting development given other international sports leagues and organisations have yet to follow suit. The line between scientific findings and evidence is not a straight one. The media and the political dynamics of the underlying society, therefore, will set the bounds for any debates about policy changes about sport policy related to concussions and CTE, because ultimately, these are the channels that will influence public opinion on the issue.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Frank Talty and Morgan Marietta for their help and feedback on this project, and the Offices of the FAHSS Dean and Provost at University of Massachusetts Lowell. Full replication data for this study can be accessed at the Odum Institute for Research in Social Science, https://doi.org/10.15139/S3/JPCERV

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joshua J. Dyck

Joshua J. Dyck is an Associate Professor of Political Science and Co-Director of the Center for Public Opinion at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. He studies American politics, with a focus on public opinion, voting behavior, elections, parties, political communication, and state politics. He is the author of Initiatives without Engagement: A Realistic Appraisal of Direct Democracy’s Secondary Effects (2019, University of Michigan Press) with Edward L. Lascher, Jr. In 2017, partnering with the Washington Post, Dyck directed the largest survey of American attitudes about sports conducted in more than a decade.

John Cluverius

John Cluverius is an Assistant Professor in the Political Science Department at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. His research and teaching focus is on applying survey methodologies to relevant political and social questions, particularly those about how political actors respond to information problems in the age of the internet. His most recent projects include examinations of new ideological labels in American politics.

Jeffrey N. Gerson

Jeffrey N. Gerson is an Associate Professor in the Political Science Department at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. He teaches several sports related courses, including Introduction to Politics and Sports, Politics of College Sports & Business of Sports. His most recent research projects examine the struggle for gender equity in US women’s soccer and ice hockey.

Notes

1. To be sure, federal laws have been applied to professional sports leagues, often as an application of national labour or antitrust laws (e.g. MLB protection from anti-trust laws, and contestations of national labor law as it relates to the NFL, as in the case of ‘deflate-gate.’) .

2. A thorough history of media coverage of concussions and CTE is provided by Gerson (Citation2017), http://www.brainshark.com/uml/A_Finest_Moment_Long_Version.

3. We hasten to note that we are not making a claim here whether the public should or should not accept this information. Rather, we are making a prediction about who will and will not accept the information based a on theory of partisan-motivated reasoning and attitudes about science. One possible limitation of this study is that we are not able to control for how people consume their information about concussions and CTE. Therefore, it is possible that acceptance or rejection of this information has to do with their trust of the media source. We believe this concern is mitigated given that much of this information was disseminated through sports media, who are less likely to be burdened by the same concerns of partisanship/ideology that pervade general media sources. However, we note this limitation and suggest it as an avenue which future studies might explore further.

4. Data was collected online by YouGov. YouGov interviewed 1152 respondents who were then matched down to a sample of 1000 to produce the final dataset. The respondents were matched to a sampling frame on gender, age, race, education, party identification, ideology, and political interest. The frame was constructed by stratified sampling from the full 2010 American Community Survey (ACS) sample with selection within strata by weighted sampling with replacements (using the person weights on the public use file). The matched cases and the frame were combined and a logistic regression was estimated for inclusion in the frame. The propensity score function included age, gender, race/ethnicity, years of education, and ideology. The propensity scores were grouped into deciles of the estimated propensity score in the frame and post-stratified according to these deciles. The sample is representative of the US population with a credibility interval of ± 4.24% when adjusted for weighting.

5. We offered an experimental treatment to half of respondents who were given the statement ‘There is a settled science that playing football causes brain injuries.’ The treatment did not produce any statistically significant differences in attitudes.

6. Respondents were asked one of two questions on the survey. Respondents were asked if statements were certainly true, probably true, probably false or certainly false. The two climate change statements, each asked to a random selection of respondents were ‘The Earth is warming due to human activity,’ and ‘The Earth may or may not be warming but not due to human activity.’ Responses were coded such that answers rejecting climate change were coded at higher levels.

7. Note that these questions refer to political realities at the time the survey was conducted in May of 2016.

8. Here we use the 10-question or ‘short’ Schwartz value survey, which was validated by Lindeman and Verkasalo (Citation2005).

References

- Albin, R.L., et al., 2016. Blowing the whistle on sports concussions: will the risk of dementia change the game? Neurology, 86 (20), 1929–1930. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000484015.90990.ab

- Berinsky, A.J., 2017. Measuring public opinion with surveys. Annual review of political science, 20, 309–329. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-101513-113724

- Campbell, J.E., 2016. Polarized: making sense of a divided america. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Druckman, J.N., Peterson, E., and Slothuus, R., 2013. How elite partisan polarization affects public opinion formation. American political science review, 107 (1), 57–79. doi:10.1017/S0003055412000500

- Fainaru-Wada, M. and Fainaru, S., 2013. League of denial: the nfl, concussions, and the battle for truth. Pittsburgh, PA: Three Rivers Press.

- Gerson, J. 2017. A finest moment: media coverage of concussions in sports since 2005. Available from: https://www.brainshark.com/uml/A_Finest_Moment_Long_Version?&fb=1&r3f1=

- Goren, P., et al., 2016. A unified theory of value-based reasoning and us public opinion. Political behavior, 38 (4), 977–997. doi:10.1007/s11109-016-9344-x

- Green, D., Palmquist, B., and Schickler, E., 2002. Partisan hearts and minds: political parties and the social identities of voters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Gross, N., 2013. Why are professors liberal and why do conservatives care? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Grossmann, M. and Hopkins, D.A., 2016. Asymmetric politics: ideological republicans and group interest democrats. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hart, P.S. and Nisbet, E.C., 2012. Boomerang effects in science communication: how motivated reasoning and identity cues amplify opinion polarization about climate mitigation policies. Communication research, 39 (6), 701–723. doi:10.1177/0093650211416646

- Hartmann, D., 2007. Rush Limbaugh, Donovan McNabb, and “A little social concern”: reflections on the problems of whiteness in contemporary american sport. Journal of sport and social issues, 31 (1), 45–60.

- Hetherington, M.J., 2001. Resurgent mass partisanship: the role of elite polarization. American political science review, 95 (3), 619–631. doi:10.1017/S0003055401003045

- Hochschild, J.L. and Einstein, K.L., 2015. Do facts matter? information and misinformation in american politics. Political science quarterly, 130 (4), 585–624. doi:10.1002/polq.12398

- Huddy, L., Bankert, A., and Davies, C., 2018. Expressive versus instrumental partisanship in multiparty european systems. Advances in political psychology, 39 (1), 173-199.

- Layman, G.C. and Carsey, T.M., 2002. Party polarization and ‘conflict extension’ in the american electorate. American journal of political science, 46 (4), 786–802. doi:10.2307/3088434

- Levendusky, M.S., 2010. Clearer cues, more consistent voters: A benefit of elite polarization. Political behavior, 32 (1), 111–131. doi:10.1007/s11109-009-9094-0

- Lindeman, M. and Verkasalo, M., 2005. Measuring values with the short schwartz’s value survey. Journal of personality assessment, 85 (2), 170–178. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa8502_09

- Lowrey, K.M., 2015. State laws addressing youth sports-related traumatic brain injury and the future of concussion law and policy. Journal of business & technology law, 10, 61.

- Lupia, A., 1994. Shortcuts versus encyclopedias: information and voting behavior in california insurance reform elections. The american political science review, 88 (1), 63–76. doi:10.2307/2944882

- Luskin, R.C. 1987. Measuring political sophistication. American journal of political science, 31 (4), 856-899.

- McCroy, P., et al. 2017. “Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016.” British journal of sports medicine; 51:838–847.

- McKee, A.C., et al., 2009. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. Journal of neuropathology & experimental neurology, 68 (7), 709–735. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a9d503

- Nisbet, M.C. and Mooney, C., 2007. Thanks for the facts. now sell them. Washington, DC: Washington post, B3.

- Nisbett, R.E. and Cohen, D., 1996. Culture of honor: the psychology of violence in the south. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Nowinski, C., 2006. Head games: football’s concussion crisis from the nfl to youth leagues. East Bridgewater, MA: The Drummond Publishing Group.

- Nyhan, B., et al., 2014. Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomized trial. Pediatrics, 133 (4), e835–e842. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2112

- Omalu, B.I., et al., 2005. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in a national football league player. Neurosurgery, 57 (1), 128–134. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000163407.92769.ED

- Popkin, S.L., 1991. The reasoning voter: communication and persuasion in presidential campaigns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Prior, M., 2007. Post-broadcast democracy: how media choice increases inequality in political involvement and polarizes elections. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Redlawsk, D.P., 2002. Hot cognition or cool consideration? testing the effects of motivated reasoning on political decision making. Journal of politics, 64 (4), 1021–1044. doi:10.1111/1468-2508.00161

- Riesman, D. and Denney, R., 1951. Football in america: A study in culture diffusion. American quarterly, 3 (4), 309–325. doi:10.2307/3031463

- Rooney Jr, J.F., 1969. Up from the mines and out from the prairies: some geographical implications of football in the united states. Geographical review, 471–492. doi:10.2307/213858

- Schwartz, S.H., 1992. Universals in the content and structure of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in experimental social psychology, 25, 1–65.

- Tagge, C.A., et al. 2018. Concussion, microvascular injury, and early tauopathy in young athletes after impact head injury and an impact concussion mouse model. Brain, 141, 422-458.

- Zaller, J. and Feldman, S., 1992. A simple theory of the survey response: answering questions and revealing preferences. American journal of political science, 36, 579–616. doi:10.2307/2111583

- Zaller, J.R., 1992. The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Appendix

Table A1. Modelling attitudes towards concussions and head injuries in sports.

Appendix

Table A2. Model concern about children participating in American football.

Appendix

Table A3. Modelling attitudes towards concussions/head injuries (climate change added).

Appendix

Table A4. Model concern about children participating in American football (climate change added).