ABSTRACT

Children with special educational needs included in Austrian mainstream schools are provided with special educational support, which aim to create learning environments, that meet the children’s needs on an individual level. Little is known about what adjustments children with special educational needs in mainstream school classes require to promote participation in school occupations. This is the first study in Austria exploring the student-environment-fit from self-perceived children’s perspective and comparing this to teachers’ perspective by using the School Setting Interview. In this cross-sectional matched pairs study twenty-five children (mean age 12.5 ± 1.4) with special educational needs and twenty-one teachers from six Austrian secondary schools were interviewed. Participants’ ratings were analyzed descriptively and statistically with Wilcoxon-Sign Rank Test. Reported adjustments from the child and teacher perspectives were analyzed with qualitative content analysis and presented using the occupational, social and physical environmental dimensions from the Model of Human Occupation. Results indicate perceived student-environment-fit differs between school activities as well as between children and teachers. Three out of 16 school activities showed a statistically significant difference between children and teacher matched-pair analysis. Children perceive more unmet needs then teachers. Most adjustments are reported in the social environment dimension and inform practitioners what adjustments are perceived to be useful for children with Special Educational Needs and their teachers. Both children’s and teacher’s perspectives provide valuable information. Significantly, children in this study were able to identify required needs and describe adjustments. To increase participation in school occupations, children can and need to be actively included in the decision-making process.

Introduction

In Europe the development toward inclusive schooling for every child started with the Salamanca Statement (UNESCO, Citation1994). The ratification of the United Nation Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN-CRPD) in Austria in 2008 intended to include all people with intellectual, physical, mental, and sensory disabilities in every part of the society (United Nations, Citation2006). Concerning the school system, article 24 of the convention refers to a fully inclusive educational system in mainstream school classes (United Nations, Citation2006). Inclusion is defined as an ongoing process of systematic reforms comprising changes in teaching methods and content, respecting diversity, different needs, abilities, characteristics and learning expectations of all students (United Nations, Citation2016). Inclusion is different from Integration, which is “the process of placing students with disabilities in existing mainstream schools, as long as they can adjust to the standardized requirements” (United Nations, Citation2016, p. 4). The Austrian government issued a national action plan intending to implement the UN-CRPD (Federal Ministry of Labour Social Affairs and Consumer Protection, Citation2012). However, recent evaluations found most of the proposed goals concerning inclusion in the school system had not yet been achieved (Austrian Court of Audit, Citation2019). Austrian schools currently still practice integration rather than inclusion of children with disabilities into mainstream school classes by placing them in so called integration classes (Paleczek, Krammer, Ederer, & Gasteiger-Klicpera, Citation2014), which are defined as classes where children with Special Educational Needs (SEN) are taught together with typically developing peers (Paleczek et al., Citation2014). Integration classes have a bigger main classroom and an additional smaller classroom. Sometimes children with SEN are taught together with typically developing peers and sometimes they are taught in the separate smaller room. In addition, children with SEN are taught a different school curriculum in one or more subjects.

SEN refers to children with disabilities who are enrolled in the Austrian mainstream educational system, but require special educational support to participate in school (Federal Ministry of Education Science and Research, Citation2019). Special educational support aims to create a learning environment that meets the child’s needs on an individual level and thus should consider the child’s individual strengths and abilities to facilitate the greatest autonomy and achievement in regard to their learning competences (Federal Ministry of Education Science and Research, Citation2019). It is important to understand that to qualify for special educational support, a child must have a permanent physical, cognitive, mental or sensory disability which hinders participation in school (Federal Ministry of Education Science and Research, Citation2019).

Children participate in a variety of occupations in the school including classroom activities, schoolwork, school trips, sports, and engaging with peers and adults (Maciver et al., Citation2019). International studies highlight that children with disabilities experience more participation limitations in school occupations than their typical developed peers as reported by caregivers in the United States of America and Canada (Coster et al., Citation2013) and by interviewed children and observation in the school context in Sweden (Eriksson, Welander, & Granlund, Citation2007). Research has found a strong association between environment and participation (Anaby et al., Citation2014; Coster et al., Citation2013; Eriksson, Citation2005; Kramer, Olsen, Mermelstein, Balcells, & Liljenquist, Citation2012).

The environment in this paper is defined as “the spaces humans occupy, the objects they use, the people with whom they interact, and the possibilities and meanings for doing that exists in the human collective of which they are part” (Taylor & Kielhofner, Citation2017, p. 20). The environment has physical, social and occupational dimensions. In the context of schools, the physical environment includes spaces like the classrooms, gyms, or the hallways, objects such as assistive devices, writing utensils or desks and chairs, as well as qualities related to sensory stimuli, accessibility and safety. The social environment includes the availability of people (e.g. teachers, support staff), emerging relationships (e.g. peers) as well as attitudes and practices (e.g. understanding about the child’s needs). The occupational environment includes the qualities of occupations such as the timing, structure and flexibility (e.g. adaptation of activities) as well as the presence of occupations (e.g. opportunities for school exercises) that reflect on a child’s roles and interests and preferences (Taylor & Kielhofner, Citation2017, p. 96).

Occupational therapy literature highlights that the physical, social and occupational aspects of the environment could be a barrier, a facilitator or both, depending on the occupation the child is participating in (Hemmingsson & Jonsson, Citation2005; Taylor & Kielhofner, Citation2017). Furthermore, international studies point out that compared to parents of typically developing children, parents of children with disabilities are more likely to identify environmental aspects like occupational, physical and social components of schools as barriers for school participation (Coster et al., Citation2013). Moreover, a cross-sectional study suggests that environmental and occupational adjustments (e.g. providing assistive devices, reduce workload, giving choices) are more amenable to change than the child’s functional abilities and health (Anaby et al., Citation2014). To promote participation, adjustments in the school environment should be considered at the child’s individual level for the school environment to fit their specific characteristics and needs (Hemmingsson, Egilson, Hoffman, & Kielhofner, Citation2014; Maciver et al., Citation2019). A concept that considers children’s characteristics in relation to the school environment is the ‘student-environment-fit.’ The student-environment-fit is defined as the (mis)match between the individual characteristics of the child and the school environment, which could be an indicator of participation in school occupations (Hemmingsson et al., Citation2014). The student-environment-fit can be investigated through the School Setting Interview (SSI), a client-centered, semi-structured assessment, with the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) as its underpinning theoretical foundation (Hemmingsson et al., Citation2014). In the SSI adjustments are defined as “changes in the environment and/or in the student’s interaction with the environment in order to increase the fit” between the student and the environment (Hemmingsson et al., Citation2014, p. 5).

Aim of the Study

This study regarding adjustments in school environment for children with SEN aimed to clarify what children need in order to participate in school occupations. The results will support teachers and occupational therapists to understand where children’s adjustment needs are met and where children experience unmet needs in school occupations. Exploring the student-environment-fit of children with SEN has deepened the understanding of what adjustments are applied in a school context. This is especially relevant for school-based occupational therapy in countries such as Austria where currently few occupational therapists provide direct services in the school system (Rathauscher, Van Nes, Kramer-Roy, & Gantschnig, Citation2020) and school-based practices are an emerging field of practice (Ulbrich-Ford et al., Citation2019).

The research questions of the study were (1) What are the needs for environmental adjustments of children with special educational needs in Austrian mainstream schools? (2) Does the perspective on environmental adjustment needs differ between children with SEN and their teachers? (3) What adjustments are reported by children and teachers?

Method

Participants

A sample of 25 children with SEN aged 10–15 years and 21 teachers from six mainstream schools participated in this cross-sectional study. The participants of this study were matched pairs, namely children with SEN integrated in a secondary mainstream school and their teachers. In Austria secondary mainstream school grades 1 to 4 corresponds to 10 to 15 years of age, as some children repeat school grades. Convenience sampling used the following inclusion criteria: for participating children identified as having SEN, enrolled in a mainstream secondary school class, able to communicate in German and – as recommended by the used assessment – a level of cognitive understanding equivalent to at least 7 years based on caregivers’ and teachers’ estimation of cognitive function (Hemmingsson et al., Citation2014). Children with disabilities who are not identified as having SEN in the Austrian system, like children with minor school related difficulties, were excluded from the study. The participating teachers provided a match to the interviewed child and they were a main class teacher or special educational teacher.

Instrumentation

The School Setting Interview (SSI) is a client-centered, semi-structured interview originally designed to gain information about the student-environment-fit from the child’s perspective and potential needs for adjustments in the school environment (Hemmingsson et al., Citation2014). In this study, the SSI was used to collect data on children’s self-perceived perspectives and the observed perspectives of matched teachers (Hemmingsson et al., Citation2014; Kocher Stalder, Kottorp, Steinlin, & Hemmingsson, Citation2017). The face-to-face interview considered 16 items including different school occupations like writing, break time activities or taking a test (full item list in ). For each item, the following questions from the SSI were asked: How do you act/manage now in your class when you are going to (item)? Do you have any support or adjustments? If so, what type? Are you satisfied with the present situation? If not, what kind of change would help you most?

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics children participants and adjustments in the school curriculum.

Table 2. Teacher and class characteristics.

Table 3. Children-teacher paired comparison of SSI item scores.

These questions provided the interviewer with information about the child’s environmental demands regarding school activities as well as already made adjustments and the wish for future ones. Each item used a four step rating scale for how the participant perceived the need for adjustments (Hemmingsson et al., Citation2014). A perfect fit (score 4) indicated no adjustments were needed, good fit (score 3) indicated adjustments were made and no further adjustments were needed, partial fit (score 2) was obtained when adjustments were made but more adjustments were needed and unfit (score 1) expressed the student’s need for adjustments who had not received any adjustments yet (Hemmingsson et al., Citation2014). After discussing each item, the interviewee and the interviewer decided jointly to which extent the environment met the child’s needs. A high student-environment-fit was achieved when there was a match between the characteristics of the child and the environment, and no adjustments were needed or had already been made. Otherwise, a low student-environment-fit indicated a mismatch between the characteristics of the child and the school environment, and the child needed adjustments in one or more school activities. The interviewed child or teacher took the final decision whether they perceived the need for adjustments in the discussed item (Hemmingsson et al., Citation2014).

The SSI was originally designed for children with physical disabilities (Hemmingsson & Borell, Citation1996). More recent studies have shown that the SSI can be used with children with a variety of disabilities like Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), emotional and behavioral difficulties (Egilson & Hemmingsson, Citation2009) and Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) (Kocher Stalder et al., Citation2017), as well as with children with SEN older than 15 years (Yngve, Munkholm, Lidström, Hemmingsson, & Ekbladh, Citation2018).

The psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the SSI demonstrated an acceptable content and construct validity (Hemmingsson & Borell, Citation1996) and acceptable inter-rater reliability (Hemmingsson & Borell, Citation1996; Hemmingsson, Kottorp, & Bernspang, Citation2004) when used with children with physical disabilities aged between 8 and 18 years. More recently, Rasch Analysis provided support for using the SSI for children with SEN (Yngve et al., Citation2018). For this study, the translated German manual of the SSI was used (Hemmingsson, Egilson, Hoffman, & Kielhofner, Citation2012).

Procedure

Recruitment of schools started with telephone contact with school principals of 16 secondary schools in the state of Carinthia, Austria who were provided with written information about the project. Principals were asked to talk to their teachers and evaluate their capacity to participate in the study. Teachers were offered more detailed information about the study through personal meetings at school. Furthermore, the recruited teachers were asked to provide information letters to caregivers whose children met the inclusion criteria.

Ethical approval was granted by the medical ethics board of Carinthia (A 41/19) and access to the school was granted by the local education authorities. Informed consent was obtained from caregivers and participating teachers. Children were first verbally informed, had the opportunitiy to ask questions and signed a simplified one-page assent form. Participation was voluntary and opting out of the study was possible at any time without any consequences for the children. The information shared by the participants was kept confidential and privacy legislations were followed.

Data was collected in six secondary schools in February and March 2020. The interviews with the teachers took between 40 and 75 minutes. The interviews with the children took between 40 to 60 minutes. Sixteen children were interviewed during school hours, while nine children were interviewed at home in the presence of caregivers. Caregivers were briefed to take a neutral stance and asked not to pressurize the child to participate in the study, nor to influence the child’s answers (Shaw, Brady, & Davey, Citation2011).

Strategies like creating a pleasant atmosphere through an informal chat in the beginning and avoiding formal seating helped to make the process enjoyable, acceptable and appropriate for participants. Interview locations offered reduced visual and auditory distractions in a separate room in participants’ homes or schools.

Data Analysis

This study used quantitative and qualitative data analysis methods. For quantitative methods the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 26, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used. First, characteristics of the two participant groups, school characteristics and assigned special educational support were calculated by frequencies and central tendencies which are presented in .

Descriptive statistics in frequencies and percentages were used to present the met and unmet needs for adjustments of participants for each item of the SSI for both participant groups. The perceived student-environment-fit was summarized with ratings 1 (unfit), 2 (partial fit) and 3 (good fit) in the SSI items. Rating 4 (perfect fit) gave an overview of SSI items that were not perceived to have adjustment needs. Furthermore, scores 1 and 2 are summarized to present current needs for adjustments indicating a low fit, which indicated perceived unmet or partly met needs for adjustments. The items were reorganized starting with the item the children had given the lowest score for student-environment-fit.

To investigate differences in SSI scores between children and teachers, non-parametric statistics were used due to the ordinal level of data, small sample size and a non-normal distributed sample, which was explored with Shapiro-Wilk-Test and a visual inspection of the histograms of the dependent variables (Norman & Steiner, Citation2008). The ranked Wilcoxon-Sign-Test was applied, which identifies differences between two mean ranks of scores in two related groups (Brace, Kemp, & Snelgar, Citation2016). In this study, differences between the teachers’ observations and the children’s self-rated perceptions were analyzed on item score level. The significance level was set at p < .05 for all statistical analyses. Effect size calculations were reported to give a second measurement for clinical interpretation of the results (Cohen, Citation1988). Frequently reported difficulties complement statistically significant differences in ranked Wilcoxon-Sign-Test results on an item level.

The analysis of similar and distinct adjustments reported by children and teachers was performed though a qualitative content analysis (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008; Sandelowski, Citation2000). First, information on adjustments was extracted from the audiotapes and written notes during the interviews. The first author listened to every interview several times to refine notes on reported adjustments. Second, initial coding was generated by the first and last author. Third, the codes were collapsed into level 2 categories (e.g. providing and exchanging information with caregivers), which were further sorted and merged into level 1 categories (e.g. knowledge provision). Fourth, emerged level 1 categories were deductively ordered into physical, social, and occupational dimensions of the MOHO. Similarities and differences as well as the range of how often adjustments are reported between children and teacher were presented in . Rather than transcribing all interviews in full, verbatim quotes from children and teacher were selectively transcribed by the first author to underline the descriptive content analysis, and presented in the results.

To ensure trustworthiness, data was collected from children and teachers and the analytical process was supported by team discussions between the first and third author on coding, forming level 1 and 2 categories, and ordering them into the environmental dimensions. All three authors confirmed the emerged categories. Qualitative data was analyzed in German and translated into English at the very last step of analysis. This approach prevents out-of-context interpretation (van Nes, Abma, Jonsson, & Deeg, Citation2010).

Results

The results are presented starting with quantitative results followed by qualitative results.

Demographic characteristics of children included primary diagnoses listed in . Out of 25 children, 14 caregivers reported additional diagnoses, including three children with developmental learning disorder, four children with cognitive or development disability, one child with a visual disability, one child with auditory processing difficulties, two children with social-emotional problems and another child with attention deficit disorder.

The 25 participating children were equally distributed in the class grade level (1st grade 24%, 2nd grade 24%, 3rd grade 32% and 4th grade 20%). Over half of the children (52%) received support in all subjects, a fifth (20%) in the main subjects (German, English and Mathematics) and four or less minor subjects, another fifth (20%) in only the main subjects and two participants (8%) in only one main subject. Teacher and class characteristics are found in . In addition, teachers reported an average of two teachers per school lesson in the classroom, namely a regular subject teacher and a special educational needs teacher. Out of 25 children four were currently in occupational therapy outside school, whereas only one occupational therapist had contact with a teacher through a school visit.

Student-Environment-Fit of Children with Special Educational Needs

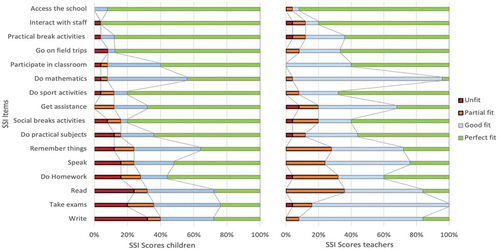

Identified needs of children with SEN reported by children and teachers, divided into unfit, partial fit, good fit and perfect fit scores in frequencies and percentages, are presented in and supplemental material A. While children reported more unmet needs for adjustments, matched teachers more often perceived needs as partially met and met. Furthermore, compared to teachers, matched children reported more activities with no need for adjustments.

Figure 1. School setting interview ratings children and teacher groups in percent.

Highest and Lowest Student-Environment-Fit

For children, the student-environment-fit was lowest (items with the highest number of partially and unmet needs) in the following items: write (40%), take exams (36%), read (32%) and do homework (28%). The student-environment-fit was highest (items that show a low number of adjustments needs) in interact with staff (96%), access to school (92%), practical break activities (88%) and field trip participation (87%). The items that teachers indicated least fitting were read (36%), do homework (32%), remember things (28%), and activities related to speaking (24%). Teachers reported the best student-environment-fit in access the school (92%), interact with staff (80%), sport activities (68%), go on field trips (66.7%) and practical break activities (64%).

Good Fit Scores

Items with a score 3 indicate activities that have been already adjusted successfully. Children indicated mathematics (48%), take exams (40%), remember things (40%), and read (40%) as most adopted to their needs. Teachers described the items mathematics (91,7%), take exams (84%), write (76%) and speak (52%) with adjustment are made and no further adjustments are needed.

Children-Teacher Pair Comparison on SSI Item Level

Central tendencies in means, standard deviation and statistically significance testing are displayed in . There was no statistical significance found in the overall difference of the SSI teachers and children’s sum scores (z = 1.38, N-Ties = 21, p = .17). Despite that, differences at item level showed statistical significance of p < .05 in three out of 16 items: write, get assistance and do mathematics.

Children-Teacher Pair Differences in “Write”

Children perceived statistically significantly more difficulties compared to matched teachers in the item write (z = 2.1, N-Ties = 18, p = .03). For instance, four children experienced not having enough time for writing activities and one child perceived the quantity of written work as difficult. In contrast, five teachers reported difficulties regarding the writing pace, four saw problems in illegible handwriting, and one mentioned pencil use as difficult for the child. Similar needs for adjustments for writing, such as distraction (e.g. from peers), were reported by three children and four teachers.

Children-Teacher Pair Differences in “Get Assistance”

Teachers identified statistically significantly lower student-environment-fit compared to the matched children’s perspective on get assistance (z = 2.05, N-Ties = 19, p = .04). Reported difficulties were disparate between the groups. Six teachers reported that children did not show that they needed help, and three teachers explained that the child needed help but did not accept the support. Three children expressed that teachers were too busy helping other children, two children did not ask for help, because they were afraid to ask, and another two children described that peers refused to help them. The only difficulty both groups mentioned was the absence of the SEN teacher in minor subjects.

Children-Teacher Pair in “Do Mathematics”

Compared to children, the paired teachers identified statistically significantly more difficulties in the item do mathematics (z = 2.0, N-Ties = 13, p = .05). Four teachers noted mathematics as difficult due to the complexity within the subject. In detail, five teachers described problems with the internalization of the mathematic structure when children had to write it down. Another two explained that children did not understand written instructions and two more mentioned that children had problems with mental mathematics. In addition, one teacher described the child had difficulties orientating themselves on the worksheet. Similarities were reported through problems related to basic mathematic operations (three children and four teachers) or the use of objects, like rulers, pencils, or a compass (one child and two teachers). Different to teachers, one child described writing numbers on the blackboard and another child described comparing themselves to peers’ capacities as challenging.

Adjustments Reported by Children and Teacher Groups

A variety of adjustments reported in both participant groups were found. A summary of all level one and level two categories is given in a nd a German version is available in supplemental material B. In total 88 level 2 categories of adjustments were found. From that, 34 in the teacher group and 26 in the children group were found to be distinct. Altogether 28 level 2 categories of adjustments were found in both participant groups. Overall, most level 2 categories of adjustments were reported under the social environmental dimensions (teacher 29, children 25), followed equally by the physical (teacher 17, children 14) and occupational (teacher 16, children 15) environmental dimensions.

Table 4. Reported adjustments by children and teacher comparison.

Adjustments Reported in Both Participant Groups

In every environmental dimension, similar adjustments were described by both participant groups. Supports through one-on-one help from teachers, caregivers or peers as well as adjustments related to time and amount elements in activities, such as giving additional time or reducing the number of school exercises, were the most commonly mentioned adjustments by teacher and children. Other than this, similar adjustments were reported in both groups, but children and teachers described different motives. Teachers, for instance, reported that they pull children with SEN out of their main classroom and teach them in a separate room for reasons related to individualizing teaching content for SEN children only. This adjustment was made especially when the teacher taught content in main subjects (math, German or English language). The teachers reported that children with SEN were not able to keep up with the regular teaching content of typically developing children.

She is taught in a smaller room with other SEN children together. Her educational curriculum is adapted because we are far behind the teaching content … we would disturb them (typically developing children and regular school teacher). Special educational teacher talking about a girl, age 13 with epilepsy

Children described this separation from typically developing children too but mentioned different reasons such as the reduction of noise or being able to learn better in a smaller group of children who they know very well.

I like to be in the other room because I can focus better in there … I like to do reading in the other (more silent) room. Boy, age 14 with developmental delay

In there (the separate room) I just have to read out loud in front of Mrs. R. (SEN teacher) and maybe three other children who I know very well, but not in front of the whole class. Boy, age 13 with conduct disorder and ccognitive disability

Distinct Adjustment Reported by Teacher

More distinct adjustments were found in the teacher group compared to the children group throughout all three environmental dimensions. Around 34 distinct level 2 categories of adjustments were only mentioned by the teacher participants. Some adjustments were just reported by one teacher such as adaptation of writing tools in the physical environmental dimension, others were reported by several teachers like the use of directed questions that facilitate cognitive processing in the social environmental dimension. Teacher reported adjustments in the occupational environmental dimension such as the creation of new activities because suitable activities for the child were not offered in the environment.

For the end of the year theater project a new role was created where she (the child) just needs to narrate and does not have to act out her part in the theater play. The goal was that she can participate in the project. Special educational teacher talking about a girl, 12 with attention disorder without hyperactivity

Other adjustments that teachers mentioned, described a child-centered involvement in respecting the child´s preferences, interests, values, and choices. This was seen as important when adjustments needed to be accepted by the child.

She always wants to write what the other children (typically developing children) have to write[and the teacher accepts then that she is making more mistakes] it is okay when the writing is not perfect … I (the teacher) stopped giving her different exercises because for her it is perceived as an insult as she has the capabilities to do the same as her peers … I just go to her seat and show her how much she needs to do. This is much easier for her to accept. Special educational teacher talking about a girl, 15 with developmental delay

For this girl less obvious adjustments worked better. The teacher respected the child’s values and made adjustments less visible to the child and peers.

Distinct Adjustment Reported by Children

In total 26 level 2 categories of adjustments were described by children. In the occupational environmental dimension children preferred a more flexible exam, like having a choice to give verbal answers to their written exam, or in the physical environmental dimension the need to remove objects that distract them. In the social environmental dimension four children described that sometimes adjustments were made by the SEN teacher but not implemented in other subjects or by other teachers.

I get similar things like the children for integration (SEN children) and I get more time. Mrs. M. (SEN teacher) is helping the other SEN child and is not here, then I get the same as everyone else. Girl, 12 with dyslexia with auditory processing disorder

Sometimes I have to read out loud in music … this is not easy for me … and in music education Mrs. S. (SEN teacher) is not with us … that’s why the music teacher does not know that I do not like that. Boy, 14 with cognitive disability

Another distinct adjustment in the social environmental dimension described role models who give the SEN child more orientation.

Sometimes I do not find the physical education gym hall, but my peers know the way so that works. Boy, 11 with Attention disorder without hyperactivity

When we do that (book presentation) I am very nervous. We do that in groups of children, and I got to present with children who are better than me. This helps. Boy, 12 with ADHD

Adjustments Used in Combination and Implemented for a Group of Children

Some adjustments were used on their own as a single adjustment, such as directed questions and instructions or verbal cues and reminders, but especially teachers reported using several adjustments in combination.

… usually, he has to write less, or he gets more time, but I also copy the exercises we did, and we glue it into his workbooks together … SEN teacher about a Boy, 12 with attention deficit disorder without hyperactivity

Furthermore, several teachers described that adjustments are not just made for one individual child, but rather for a group of children with SEN. This was reported in several level 2 categories such as providing easier exercises and content, or adjustments that facilitate predictability through known test content. Other adjustments were made for groups of children with SEN to reduce cognitive processing efforts.

He has problems concentrating when he is reading … it helps when he can read it again in silence, or another child or I read it out loud to him. This is something I do with all SEN children. SEN teacher about a Boy, 13 with development delay and conduct disorder

Other adjustments were implemented for the whole class. In the physical environmental dimension adjustments related to visual supports like displaying the timetable, using memory aids, reducing visual distractors and adjustments related to technology, such as the use of apps on the cell phone to communicate and inform caregivers to reduce the amount of information. In the occupational environmental dimension adjustments made for the whole class were for instance allowing more breaks, giving additional time to finish exercises, giving two choices for activities (like in physical education, or arts and craft) or to break exercises into smaller chunks of work.

Discussion

The level of low and high student-environment-fit depends on the school activity and differs between children and teachers. The main results of our study are that three out of 16 items show a statistically significant disagreement between children and teachers and that children report a larger number of unmet needs than their teachers.

Importantly, we found that children were able to identify needs and articulate adjustments. This indicates the importance of children’s perspectives when considering their school participation. Whiteneck and Dijkers (Citation2009) suggest, individuals with disabilities may become more aware of barriers, because they are more likely to encounter them directly. Children have different experiences than their teachers who only observe needs. Other studies found that teachers might have limited understanding on how disability influences a child’s participation in school activities (Gantschnig, Hemmingsson, & la Cour, Citation2011; Mundhenke, Hermansson, & Nätterlund, Citation2010). So, as children are able to express needs, they should also be involved in decision making regarding adjustments, because only then specific needs will be targeted (Egilson & Hemmingsson, Citation2009). Interestingly, a meta-synthesis on the children’s perspective of the impact of environment on participation emphasizes that children desire to make direct decisions regarding adjustments and that their preferences, needs and strengths to facilitate participation must be acknowledged (Kramer et al., Citation2012). In other words, adjustments made by teachers, caregivers or therapists only might be less effective (Egilson & Hemmingsson, Citation2009).

Children’s participation in decision making is especially crucial regarding the statistically significant disagreements in the items do mathematics, get assistance and write. Concerning get assistance, contrasting needs were reported. For example, teachers report that the children do not signal the need for support while the children state they do not ask for help because the teacher is too busy helping other children. Egilson and Traustadottir (Citation2009) identified the need for clarification when and where assistance is needed. Our study additionally highlights the importance of constant adjustments throughout all subjects and the school day. Adjustments should not depend on one person who is introducing those adjustments.

Write indicates the highest number of children with a low student-environment-fit as well as a statistically significant disagreement between children and teachers. Similar to Egilson and Hemmingsson’s (Citation2009) results, children with physical and psycho-social disabilities identify the item write with most unmet needs. Our study adds that writing might be perceived as most troubling for all children irrespective of diagnosis. Fine-motor problems are reported within several diagnoses, including ADHD, developmental delays and Development Coordination Disorder (Blank et al., Citation2019; Kerstjens et al., Citation2011; Lavasani & Stagnitti, Citation2011). In addition, writing is a school activity that is ever-present in most subjects. Teacher report ways to increase the student-environment-fit through adjustments such as printing a text and gluing it into the workbook or reducing unnecessary writing activities by using Apps to provide information to caregivers.

Results on do mathematics were different to previous studies in two ways. First, there was statistically significant disagreement between children and teachers (Kocher Stalder et al., Citation2017). Second, it was the most adjusted item compared to other items (Egilson & Hemmingsson, Citation2009; Kocher Stalder et al., Citation2017; Yngve, Lidström, Ekbladh, & Hemmingsson, Citation2019). It appears that needs in mathematics might be already adjusted to a great extent for children with SEN, but children and teacher still disagree on the right adjustments. Our study enhances the understanding of where children with SEN encounter needs for adjustments in mathematics, such as mental arithmetic, internalization of the mathematic structure, understanding written instructions or the use of basic mathematical operations.

Further results indicate a vast range of reported adjustments in all three environmental dimensions. Both participant groups reported most adjustments in the social environmental dimension, followed equally by the physical and occupational environmental dimensions. A survey on school-based occupational therapy provision in Austria found that occupational therapy interventions targeted needs linked to the social environment with a bigger focus, followed by occupation-based interventions and least interventions targeting the physical environment (Rathauscher et al., Citation2020). It therefore appears that interventions from occupational therapists most often target changing attitudes and viewpoints through consultation of parents and teachers (Rathauscher et al., Citation2020). The results of our study inform occupational therapist where adjustments in the social environmental dimensions are made and informs school-based occupational therapy practices what further adjustments need to be considered.

Limitation and Future Research

First, the study includes a small number of participants and a heterogeneous group of children with a variety of disabilities. The Austrian legislation of including children into mainstream education refers to a variety of disabilities including physical, mental, cognitive and sensory disabilities (Federal Ministry of Education Science and Research, Citation2019). The current sample did not include children with physical disabilities or sensory function.

Methodological limitations include that the cross-sectional design of the study just provides a snapshot of the population at a single point. The aim of the study was to describe and investigate the differences and similarities between children´s and teacher´s perspectives of the student-environment-fit. This study did not examine how successfully the adjustments were implemented.

Despite this, incorporating different perspectives of children and teachers as well as the supplementation of statistical results with described adjustments are considered as a strength and provide a clear picture of what children with SEN need in order to participate in the school activities.

Future research should include observations in the classroom and school context to give an additional objective outcome on the influence of environment on participation. Prospective research could also address which adjustments are effective under what conditions.

Conclusion and Implications for Practice

This is the first study investigating the student-environment-fit in Austrian mainstream school classes. The results of this study give teachers and therapists insights into where children in Austrian mainstream school classes experience difficulties that need to be addressed to support participation. Depending on different school occupations, the student-environment-fit differs from children’s self-perceptions and teachers’ observed perspectives. Children in this study were able to formulate adjustments, indicating a valued perspective that should be considered when participation in school occupations is the aim. Since teachers already provide a variety of adjustments to school occupations, their perspective needs to be respected as well to facilitate interprofessional collaboration. The SSI in its client-centered nature allows investigations into the children’s perspectives and the influence of the environment on their participation. This can be used not only in detecting needs but also in child-centered intervention planning and intervention, leading to better suited adjustments in the school context.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (27.3 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors cordially thank: all the children and teachers participating in this study.

This research was carried out in partial fulfilment of the requirements of obtaining the degree of the European Master of Science in Occupational Therapy.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anaby, D., Law, M., Coster, W., Bedell, G., Khetani, M., Avery, L., & Teplicky, R. (2014). The mediating role of the environment in explaining participation of children and youth with and without disabilities across home, school, and community. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 95(5), 908–917. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2014.01.005

- Austrian Court of Audit. (2019). Austrian Court of Audit on Inclusive Education: What does Austria’s school system offer? [Bericht des Rechnungshofes Inklusiver Unterricht: Was leistet Österreichs Schulsystem?]. http://www.rechnungshof.gv.at/fileadmin/downloads/2012/berichte/teilberichte/bund/Bund_2012_11/Bund_2012_11_4.pdf%5Cnhttp://www.rechnungshof.gv.at/fileadmin/downloads/2011/berichte/teilberichte/bund/bund_2011_11/Bund_2011_11_3.pdf%5Cnhttp://www.rechnungsh

- Blank, R., Barnett, A. L., Cairney, J., Green, D., Kirby, A., Polatajko, H., … Vinçon, S. (2019). International clinical practice recommendations on the definition, diagnosis, assessment, intervention, and psychosocial aspects of developmental coordination disorder. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 61(3), 242–285. doi:10.1111/dmcn.14132

- Brace, N., Kemp, R., & Snelgar, R. (2016). SPSS for Psychologists (and everybody else) (6th ed.). Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan Education.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral science. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

- Coster, W., Law, M., Bedell, G., Liljenquist, K., Kao, Y. C., Khetani, M., & Teplicky, R. (2013). School participation, supports and barriers of students with and without disabilities. Child: Care, Health and Development, 39(4), 535–543. doi:10.1111/cch.12046

- Egilson, S., & Hemmingsson, H. (2009). School participation of pupils with physical and psychosocial limitations: A comparison. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(4), 144–152. doi:10.1177/030802260907200402

- Egilson, S., & Traustadottir, R. (2009). Assistance to pupils with physical disabilities in regular schools: Promoting inclusion or creating dependency? European Journal of Special Needs Education, 24(1), 21–36. doi:10.1080/08856250802596766

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Eriksson, L., Welander, J., & Granlund, M. (2007). Participation in everyday school activities for children with and without disabilities. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 19(5), 485–502. doi:10.1007/s10882-007-9065-5

- Eriksson, L. (2005). The relationship between school environment and participation for students with disabilities. Pediatric Rehabilitation, 8(2), 130–139. doi:10.1080/13638490400029977

- Federal Ministry of Education Science and Research. (2019). Richtlinien zur Organisation und Umsetzung der sonderpädagogischen Förderung [Guidelines for the organization and implementation of special educational needs]. https://www.bmbwf.gv.at/Themen/schule/schulrecht/rs/2019_07.html

- Federal Ministry of Labour Social Affairs and Consumer Protection. (2012). National action plan on disability 2012-2020. Strategy of the Austrian Federal Government for the implementation of the UN disability rights convention (pp. 1–112). Vienna: Austrian Federal Government.

- Gantschnig, B., Hemmingsson, H., & la Cour, K. (2011). Feeling and being involved? Participation experienced by children with disabilities at regular schools in Austria. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, and Early Intervention, 4(3–4), 260–275. doi:10.1080/19411243.2011.633424

- Hemmingsson, H., & Borell, L. (1996). The development of an assessment of adjustment needs in the school setting for use with physically disabled students. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 3(4), 156–162. doi:10.1080/11038128.1996.11933202

- Hemmingsson, H., Egilson, S., Hoffman, O., & Kielhofner, G. (2012). Das school setting interview (SSI) version 3.0. Idstein: Schulz-Kirchner Verlag GmbH.

- Hemmingsson, H., Egilson, S., Hoffman, O., & Kielhofner, G. (2014). The school setting interview (SSI) version 3.1. Nacka: Swedish Association of Occupational Therapists.

- Hemmingsson, H., & Jonsson, H. (2005). An occupational perspective on the concept of participation in the international classification of functioning, disability and health - some critical remarks. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 59(5), 569–576. doi:10.5014/ajot.59.5.569

- Hemmingsson, H., Kottorp, A., & Bernspang, B. (2004). Validity of the school setting interview: An assessment of the student-environment fit. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 11(4), 171–178. doi:10.1080/11038120410020683

- Kerstjens, J. M., De Winter, A. F., Bocca-Tjeertes, I. F., Ten Vergert, E. M. J., Reijneveld, S. A., & Bos, A. F. (2011). Developmental delay in moderately preterm-born children at school entry. Journal of Pediatrics, 159(1), 92–98. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.12.041

- Kocher Stalder, C., Kottorp, A., Steinlin, M., & Hemmingsson, H. (2017). Children’s and teachers’ perspectives on adjustments needed in school settings after acquired brain injury. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 25(4), 233–242. doi:10.1080/11038128.2017.1325932

- Kramer, J. M., Olsen, S., Mermelstein, M., Balcells, A., & Liljenquist, K. (2012). Youth with disabilities’ perspectives of the environment and participation: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38(6), 763–777. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2012.01365.x

- Lavasani, N. M., & Stagnitti, K. (2011). A study on fine motor skills of Iranian children withattention deficit/hyper activity disorder aged from 6to 11 years. Occupational Therapy International, 18(2), 106–114. doi:10.1002/oti.306

- Maciver, D., Rutherford, M., Arakelyan, S., Kramer, J. M., Richmond, J., Todorova, L., … Forsyth, K. (2019). Participation of children with disabilities in school: A realist systematic review of psychosocial and environmental factors. PLoS ONE, 14(1), e0210511. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0210511

- Mundhenke, L., Hermansson, L., & Nätterlund, B. S. (2010). Experiences of Swedish children with disabilities: Activities and social support in daily life. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 12(2), 130–139. doi:10.3109/11038120903114386

- Norman, G., & Steiner, D. (2008). Biostatistics: The bare essentials (3rd ed.). Hamilton, Ont: B.C. Decker.

- Paleczek, L., Krammer, M., Ederer, E., & Gasteiger-Klicpera, B. (2014). Inclusion of children identified as having special educational needs (SEN) within the Austrian compulsory educational system. Da Investigação Às Práticas, 5(2), 20–43. doi:10.1080/08856257.2014.933550

- Rathauscher, U., Van Nes, F., Kramer-Roy, D., & Gantschnig, B. (2020). Eine Umfrage über die ergotherapeutische Zusammenarbeit mit Schulen [Occupational therapy and collaboration with schools : Results from an online survey in Austria]. 15(3), 107–115. 10.2443/skv-s-2020-54020200303

- Sandelowski, M. (2000). Focus on research methods: Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. doi:10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g

- Shaw, C., Brady, L.-M., & Davey, C. (2011). Guidelines for research with children and young people. London: NCB Research Centre. http://www.nfer.ac.uk/nfer/schools/developing-young-researchers/NCBguidelines.pdf

- Taylor, R. R., & Kielhofner, G. (2017). Kielhofner’s model of human occupation: Theory and application (Fifth ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer.

- Ulbrich-Ford, S., Morgenthaler, T., Rathauscher, U., Kastner, H., Eberle, M., & Schöhnthaler, E. (2019). Positionspapier zur schul- und kindergartenbasierten Ergotherapie: Die Rolle und das Aufgabengebiet von Ergotherapeut*innen in österreichischen Bildungseinrichtungen [Position paper school-based occupational therapy in Austrain schools]. Ergotherapie Austria. https://www.ergotherapie.at/sites/default/files/schul-und_kindergartenbasierte_ergotherapie_positionspapier_ergotherapie.pdf

- UNESCO. (1994). The salamanca statement and framework for action on special needs education. United Nations. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000098427%0A

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). 10.5771/9783845266190-471

- United Nations. (2016). General comment No. 4 (2016), Article 24: Right to inclusive education. In UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (Issue September, pp. 1–24). http://www.refworld.org/docid/57c977e34.html

- van Nes, F., Abma, T., Jonsson, H., & Deeg, D. (2010). Language differences in qualitative research: Is meaning lost in translation? European Journal of Ageing, 7(4), 313–316. doi:10.1007/s10433-010-0168-y

- Whiteneck, G., & Dijkers, M. P. (2009). Difficult to measure constructs: conceptual and methodological issues concerning participation and environmental factors. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90(11), 22–35. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2009.06.009

- Yngve, M., Lidström, H., Ekbladh, E., & Hemmingsson, H. (2019). Which students need accommodations the most, and to what extent are their needs met by regular upper secondary school? A cross-sectional study among students with special educational needs. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 34(3), 327–341. doi:10.1080/08856257.2018.1501966

- Yngve, M., Munkholm, M., Lidström, H., Hemmingsson, H., & Ekbladh, E. (2018). Validity of the school setting interview for students with special educational needs in regular high school - a Rasch analysis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 1–10. doi:10.1186/s12955-017-0830-6