ABSTRACT

This paper presents an enhanced evaluation framework for teacher professional development programmes, which is based on one originally proposed by Huber in 2011. This paper draws on a study on the Professional Up-skilling of English Language Teachers (ProELT) programme in Sabah (Borneo), Malaysia. The study adopted a mixed methods exploratory sequential design using a questionnaire survey, individual interviews and a focus group discussion. Based on the findings from the study, four new components have been added to Huber’s original framework, namely (1) selection of participants, (2) incorporation of the Adult Learning principles, (3) follow-up support, and (4) assessment of programme impact. This enhanced framework has significant contributions to make to programme designers and programme providers, in providing them with additional guidelines to consider when designing the pre-, ongoing and post-phases of a teacher professional development programme.

Introduction

International organisations such as the British Council, the World Bank, and the Department for International Development in the United Kingdom have funded teacher professional development programmes and projects in Asia and developing countries (Dushku Citation1998, Balassa et al. Citation2003, Courtney Citation2007, Hamid Citation2010). For example, Bangladesh received funds worth USD$500,000 and USD$155.7 million for two, long-term teacher professional development projects from the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank, respectively, to conduct the Teaching Quality Improvement in Secondary Education Project and the Secondary Education Quality and Access Enhancement Project (Hamid Citation2010). The duration of teacher professional development programmes or projects ranged between one year to an astounding fourteen years, the latter being the English Language Teaching Improvement Project in Bangladesh (Hamid Citation2010).

Most of these teacher development activities shared similar approaches. Skills- and knowledge development-based approaches are highly favoured by administrators, because they are ‘clearly focused, easily organised and packaged, and relatively self-contained’ (Hargreaves and Fullan Citation1992, p. 3). However, these approaches were criticised for placing little value on teachers’ knowledge and experience in the development of classroom skills. Hargreaves and Fullan (Citation1992) argue that ‘the skills in which teachers are trained are too often implemented out of context – their appropriateness for the teacher as a person, for the teachers’ purpose, or for the particular classroom setting in which the teacher works, being overlooked’ (p. 6). One of the core reasons for this lack of relevance between teacher development programmes and teachers’ needs is centralised planning and decision-making in which top bureaucrats decide what teachers ought to be doing (Dyer et al. Citation2004), and the design of a training programme is based on the required behavioural change (Courtney Citation2007). Studies by Dyer (Citation1996) and Uysal (Citation2012) on English language teacher professional development projects in India and Turkey, respectively, reveal issues resulting from centralised development projects. For example, the £250 million Operation Blackboard project in India aimed to enhance the quality of school education and teaching methods with a shift from a textbook-centred to a learner-centred approach by supplying a second teacher to existing single primary teachers (Dyer Citation1996). The project was undertaken via a mass orientation in the form of cascade training ‘with little attention to how the gap between teachers’ current practice and the desired behaviour was to be narrowed’ (Dyer Citation1996, p. 33). As a result, some teachers rejected the teaching and learning aids, which they claimed to be irrelevant to their teaching needs and of poor quality, and the lack of explanation and training by the programme provider on strategies to implement the aids. On the other hand, the Turkish Ministry of Education organised a one-week, compulsory in-service training for primary English language teachers, which aimed to familiarise teachers with the new curriculum goals and teaching techniques for young language learners (Uysal Citation2012). Unfortunately, teachers’ perceptions of the aforementioned training programmes revealed a lack of compatibility between the content and teachers’ needs, and a lack of opportunity for discussion regarding their own problems, the material development component, and course evaluation. These studies support Kennedy’s (Citation1988) argument that a top-down planning approach rarely gathers feedback from the implementers, and the feedback seldom reaches the programme providers. In addition, these studies also revealed the importance of including potential teacher participants, who would be able to provide first-hand views of the suitability of the content for their teaching context and needs, in the planning and decision-making of a programme. It is indeed a poor use of financial resources and participants’ invested time if these expensive programmes and projects fail to deliver their intended objectives and to fulfil the needs of the participants.

In Malaysia, the Professional Up-skilling of English Language Teachers (ProELT) programme was fully funded by the Malaysia Ministry of Education and was delivered by the British Council. The provider was selected from eight potential programme consultants who fulfilled the 6Cs criteria that were listed by the Ministry namely competence, capacity, content, customisation, context, and cost (Hasreena and Ahmad Citation2015). However, questions remain as to the way success of teacher professional development programmes is evaluated and whether the theoretical frameworks currently deployed are the most suitable. This paper presents some suggestions for the enhancement of the framework proposed by Huber (Citation2011) for the evaluation of a teacher professional development programme. It is based on Hiew and Murray's (Citation2018) study on the ProELT programme in Sabah (Borneo), Malaysia. Based on the major findings from the study, gaps were identified and four new elements are proposed for inclusion, namely: (1) selection of participants, (2) incorporation of Adult Learning principles, (3) follow-up support, and (4) assessment of programme impact. These will be discussed in detail below.

In the following sections, the background of the ProELT will first be explained. Two existing models of evaluation for teacher professional development programmes will be compared in order to justify the initial adoption of Huber’s framework. The need for inclusion of Adult Learning Theory in the ProELT study will be explained. Next, the four new elements in Huber’s enhanced framework will be discussed and how it is situated within the context of a developing country. This paper will conclude with the implications and limitations of the enhanced framework.

Background of the Professional Up-skilling of English Language Teacher programme

Throughout the years, the Malaysia Ministry of Education and the British Council Malaysia have rolled out various professional development programmes for English language teachers. One of these projects, prior to the ProELT, was the English Language Teacher Development Project (ELTDP) for primary school English language teachers in Borneo specifically Sabah and Sarawak, which ran from 2010 to 2015 with an enormous cost of £27 million (British Council Citation2015). The project’s primary goal was to improve the teaching and learning of English effectiveness and to raise the English proficiency of 1,200 teachers in 600 rural schools through the assistance of 120 mentors (British Council Citation2013, Bowden Citation2015) by adopting a fully immersive and self-directed approach. The mentors were placed in schools to guide teachers in designing and conducting their lessons. Their teaching improvement was monitored by and discussed with the mentors during weekly sessions. By the end of the project, the teachers demonstrated they had moved up a level from B1 and B2 to levels B2 and C1 based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (British Council Citation2015). Due to the success of the ELTDP, the Ministry of Education decided to rebrand the ELTDP as ProELT and to expand the programme to include secondary school English language teachers throughout Malaysia.

The ProELT was a Malaysia government-funded programme which was conducted as a one-year, in-service training for primary and secondary school English language teachers. It was part of the Malaysia Education Blueprint 2013–2025 to reform the education system which included enhancing the quality of school teachers, specifically the language proficiency and instructional ability of English as a second language (ESL) teachers (Ministry of Education Malaysia Citation2013). The British Council was given the responsibility to design and conduct the ProELT for 14,000 teachers (British Council, n.d.). Its aims were: (1) to enhance English language teachers’ language proficiency and (2) to develop their instructional skills through a blended training approach, which included face-to-face training, supported online learning and integrated proficiency and methodology training. The trainers were qualified, native speakers from the United Kingdom, the United States of America, Australia, and New Zealand, amongst others. Each class was also assigned an e-moderator (online trainer) to manage and facilitate online training. In total there were 480 hours face-to-face (240 hours) and online learning (240 hours). Teacher participants were assigned to one of two modes: cluster mode and centralised mode. The former catered to teachers in the urban and rural schools and the latter for teachers in the remote and interior schools. Teachers in the cluster mode attended training once a week for six hours at selected teacher training centres. In contrast, due to the regional locations of the rural and interior teachers, the centralised mode training was implemented in four phases: Phase 1 and 3 (face-to-face and online), Phase 2 and 4 (online) (British Council, n.d.).

Although no specific justifications were mentioned in the Ministry of Education’s documents for conducting the ProELT for a one-year duration, literature from previous research on teacher professional development programmes have reported the greater effectiveness of long-term training programmes on teachers’ learning and instructional practice. In support of this position, Garet et al. (Citation1999), Birman et al. (Citation2000) and Desimone et al. (Citation2002) argue that reform approaches, which tend to have longer duration, are thus able to provide more active learning opportunities for teachers than to traditional approaches. Traditional approaches include one-size-fits-all workshops, courses, seminars, and conferences. Reform approaches are subject- and need-focused programmes which include study groups, teacher networking, mentoring, coaching, committee or task force, internship, individual research project, or teacher research centres (Desimone et al. Citation2002, Lee Citation2004). Darling-Hammond (Citation1997) also argues that the longer duration of reform types of activities enable them to be more accommodating to teachers’ needs and goals. For example, Garet et al.’s (Citation2001) national survey on 1,027 mathematics and science teachers showed that the duration of an activity significantly affects teacher learning, and they argued that professional development programmes should be sustained over time and include a considerable number of contact hours. Supovitz and Turner (Citation2000) reported two findings that strongly link longer training duration with teachers’ use of inquiry-based teaching practices, after approximately 80 hours of professional development, and teachers’ use of investigative classroom culture, after 160 hours, respectively, based on a random survey sample of 3,464 science teachers. Meanwhile, the four-week, eighty-hour Cognitively Guided Instruction summer institute programme conducted by Carpenter et al. (Citation1989), which focussed on improving teachers’ understanding of student learning in elementary arithmetic, showed positive effects on teachers’ instructional skill in teaching problem solving and in students’ understanding and problem-solving abilities. Another four-year study by Fennema et al. (Citation1996), also on the Cognitive Guided Instruction programme which involved twenty one Grade 1 to 3 teachers, produced similar findings to those of Carpenter et al. (Citation1989). The programme included coaching and mentoring in the classroom, and multiple workshops each year, as follows: Year 0 (induction) – one 2 ½-day workshop; Year 1 – one 2-day workshop before the start of the school year, and fourteen 3-hour workshops during the academic year; Year 2 – four 2 ½hour workshops, and one 2-day ‘reflection workshop’; Year 3 – one 3-hour reflection workshop, d two 2 ½-hour review workshops.

Besides the duration, the proposed outcomes of a programme are crucial in determining the success of a professional development programme. Many current state-of-the-art professional development programmes are content-focused, which emphasise content knowledge, subject matter, and/or understanding student learning. For example, Diamond et al. (Citation2014) designed a professional development intervention programme for Grade 5 Science teachers in order to enhance teachers’ content knowledge and student achievement outcomes. In addition to conducting workshops and providing school site support, a unique feature of this intervention programme was the comprehensive stand-alone science curriculum, which was specifically aligned with the benchmark tested by the state science assessment by consulting the state science content standards. This clearly showed that the intervention was not a standardised programme but was personalised for the programme participants. Results from the intervention showed significant effect on teachers’ content knowledge but not on the students’ learning outcomes. This was probably due to the timing of the study, which was conducted in the first year of the intervention programme, which was planned to continue for three years (Diamond et al. Citation2014). Another similar example of a state-of-the-art study was conducted by Lee et al. (Citation2004), who designed an inquiry-based science professional development programme for Grades 3, 4 and 5 teachers who taught diverse student groups, which enhanced teachers’ knowledge of science content and developed their instructional skills in teaching science to diverse student groups. The intervention programme was carried out for three years. Statistical analysis indicated overall positive performance by the students at the end of each school year. Hence, content-focused professional programmes have been shown to be beneficial for teachers’ and students’ learning outcomes, and worthwhile especially if they involve long-term time investment by the teachers and trainers. In the case of the ProELT, the content of the programme consisted of language input and skills development as well as the enhancement of teaching knowledge and skills.

The Malaysia Ministry of Education and the British Council utilised two methods of selections for the ProELT participants. First, the Cambridge Placement Test (CPT), which measured the four language skills namely reading, writing, speaking and listening, served as an assessment tool to select the first batch of ProELT participants. Jalleh (Citation2012) reported that two-thirds of the 70,000 Malaysian English teachers had failed to reach a proficient English level (Band C) based on the Common European Framework Reference for Languages. Second, the second cohort were selected using the British Council-designed test called the Aptis test. Teachers who scored B1 and B2 (independent level) in the CPT and Aptis test were required to participate in the ProELT.

The ProELT participants were a combination of primary and secondary school teachers within the same training group. This was rather unusual as teachers from different levels do not usually attend the same professional development programme, especially if it pertains to instructional development. This is because primary and secondary level teachers deal with different groups of learners and apply different pedagogical approaches. Hence, the reasons justifying the focus of the present study on ProELT are as follows:

(i) to explore the impact of a standardised teacher professional development programme,

(ii) to contribute to the literature in the area of teacher professional development in a developing country.

More specifically, the study filled a gap in the literature by examining the outcome and impact of a standardised professional development programme amongst ESL teachers from mixed teaching levels. This was significant because different instructional approaches were required for teaching young learners in primary level and young adults in secondary level. Therefore, it was useful to investigate the outcome of a standardised teacher professional development programme that involved teachers with different level of instructional needs.

A comparison of existing models of evaluation for teacher professional development programmes

Huber’s (Citation2011) framework was adopted in the present study on the ProELT to evaluate the programme’s impact on the English language teacher participants (Hiew and Murray Citation2018). Before the decision was made to adopt Huber’s framework, we had considered applying two other models of evaluation namely Kirkpatrick’s (Citation1994) four-level evaluation model and Adey et al.’s (Citation2004) model of factors which influence the effectiveness of professional development.

Both models have their own unique strengths. Kirkpatrick’s simple model includes a four-level evaluation of a training as follows:

Level 1: Reaction (How did participants respond to the training?)

Level 2: Learning (How much did the participants learn from the training and have their skills improved?)

Level 3: Behaviour (How did participants apply what they learned from the training?)

Level 4: Result (What benefits has the organisation experienced as a result of the training?)

Each level is important and has an impact on the next level. Kirkpatrick stressed that ‘none of the levels should be bypassed simply to get to the level that the trainer considers the most important’ (p. 21).

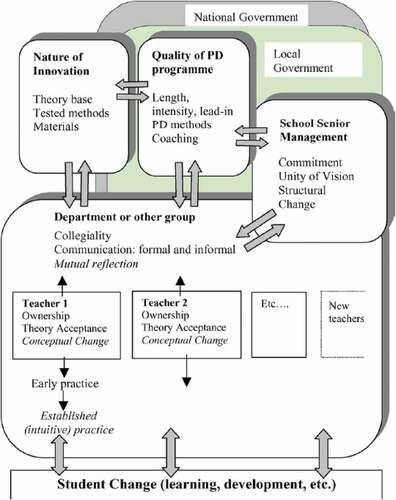

Meanwhile, Adey et al.’s model () considers the effectiveness of a professional development from five perspectives namely (1) Nature of innovation; (2) Quality of programme; (3) Department or teaching community; (4) School senior management; and (5) Student change. The two-way interaction between the elements indicates their co-dependence in ensuring the success of a professional development programme.

Figure 1. A model factors which influence the effectiveness of professional development.

However, both models have their limitations. Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model is one-way and each level is dependent on the other (i.e. the model does not permit separate evaluations for each level). Also, his model is participant-centred as opposed to Adey et al.’s model which includes evaluation of the content features of the programme. Both models are similarly limited by their focus on the evaluation of the progress and completion of a programme.

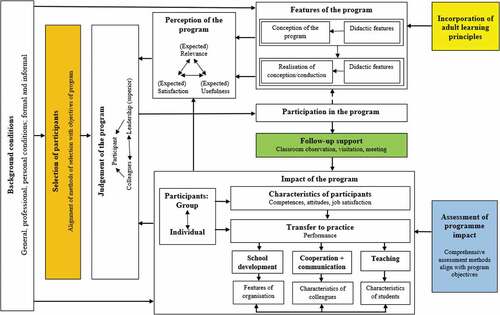

In comparison, Huber’s framework () contains a pre-training evaluation element of the participants’ general, professional and personal background conditions including job profile, educational aims, professional needs and interest in professional development, amongst others. Although the authors did not refer specifically to the framework, these individual elements have been highlighted in a number of studies including those by Kennedy and Clinton (Citation2009), Quick et al. (Citation2009), Perkins (Citation2010) and Khandehroo et al. (Citation2011) who all reported the importance of identifying teachers’ professional need and providing suitable professional development programmes to ensure the effectiveness of the programmes. Programme providers’ failure to take these elements into consideration have resulted in discouraging outcomes and responses from teacher participants in several standardised professional development programmes such as the Strengthening Mathematics and Sciences in Secondary Schools in Kenya (Mwangi and Mugambi Citation2013) and the Operation Blackboard in India (Dyer Citation1996), as the programmes did not fulfil the professional needs of the teachers. Hence, it was a waste of funding and teachers’ invested time. Based on the comparisons between Kirkpatrick, Adey et al. and Huber’s framework, we decided that Huber’s framework served as a more suitable and robust framework in line with the aim and objectives of the present study on the ProELT (Hiew and Murray Citation2018).

Adult learning theory

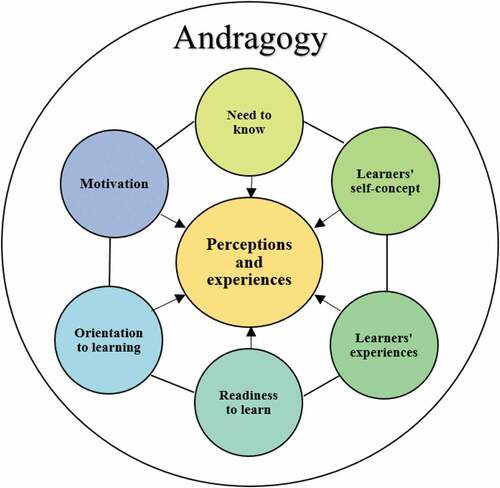

The present study was also guided by a second framework, namely the highly influential Adult Learning Theory, first proposed by Knowles (Citation1980) and further developed by him and subsequent researchers, It is known as andragogy, which is defined as ‘the arts and science of helping adults to learn’ (Knowles Citation1980, p. 43). The andragogical model by Knowles et al. (Citation2005) is based on six principles of adult learning requirements:

1. The need to know – Adults need to know why they need to learn something before undertaking to learn it.

2. The learners’ self-concept – Adults have a self-concept of being responsible for their own decisions.

3. The learners’ experience – Adults have a vast experience that is a rich source for learning.

4. Readiness to learn – Adults become ready to learn things that they need to know that are relevant to their real-life situation.

5. Orientation to learning – Adults’ learning is life-centred (or task-centred or problem-centred), which will motivate them to learn when they perceive that learning will help them perform tasks or deal with problems in their life situations.

6. Motivation – Adults are more responsive to internal motivators (e.g. self-satisfaction, self-esteem) as opposed to external motivators (e.g. promotions, higher salaries).

shows a visual representation of the adoption of andragogy, and its relation to the ESL teachers’ perceptions of and experiences with the ProELT.

Figure 2. The relationship between andragogy and ESL teachers’ perceptions of and experiences with the ProELT.

Figure 3. Addition of four new components to Huber’s evaluation framework for teacher professional development programme. Source: Huber (Citation2011)

Andragogy was used in the present study to explore teachers’ perceptions and experiences with the ProELT on whether the programme provider had taken these six principles into consideration when designing the ProELT. Although not all of these principles might be fully embedded in the ProELT, they are among the pertinent factors that would ensure the effectiveness and sustainability of a professional development (Hayes Citation2000, O’sullivan Citation2002, Fullan Citation2007). Hence, the adoption or otherwise principles of andragogy may also have influenced the perceptions of the ProELT participants as to whether the programme was relevant, satisfying and useful (Huber Citation2011). Other researchers had also indicated that programme providers need to consider teachers’ experiences, particularly experienced teachers, when designing a programme, due to the different stages of their careers and teaching contexts (Steffy and Wolfe Citation2001, Lessing and De Witt Citation2007), and the fact that they may have different learning needs (Knowles et al. Citation2005).

The addition of four new elements to Huber’s evaluation framework

Although findings from the questionnaire survey, focus group and interview in the ProELT study indicated that the teacher participants obtained new knowledge and skills from the programme, there were four major limitations identified in the programme: (1) the coursebook materials, (2) the negative emotional impact on the teachers, which compromised the potential benefit of the programme, (3) the selection of participants, and (4) the amount of follow-up support (Hiew and Murray Citation2018). These findings had led to the discovery of the gaps in Huber’s framework. Based upon the aforementioned findings, four new elements were generated to enhance Huber’s framework:

1. Selection of participants based on the objectives of a programme,

2. Incorporation of adult learning principles,

3. Follow-up support,

4. Methods for assessing the impact of a programme based on the programme objectives.

presents the enhanced version of Huber’s framework, with the four additional elements being represented in coloured boxes. In the following section we will explain in more detail how our findings led us to recommend these amendments.

Selection of participants

The first element (brown box), selection of participants, was added to Huber’s framework, based on two significant findings from the focus group and interview with the ProELT teacher participants. First, the experienced teachers were dissatisfied with the programme provider’s selection methods of participants, which was non-voluntary, because it did not consider their professional needs and postgraduate qualifications. The interview participants had between six and 28 years of teaching experience, two teachers had a Master’s in Education (TESL) and one was an experienced examiner for the Malaysian University English Test (MUET). The teachers viewed that the ProELT was similar to a refresher course in teaching methodology and the contents of the training, which focused on fundamental grammar and pedagogy, were more suitable for linguistically less proficient and instructionally less competent teachers. As a result, the experienced teachers considered their participations in the ProELT as a waste of time. Their views can be related to an existing element in Huber’s framework namely judgement of the programme. The teachers’ dissatisfaction supports the findings from previous studies on the impact of top-down passive-recipient form of professional development on teachers whose participations were non-voluntary (Hamid Citation2010, Mwangi and Mugambi Citation2013). Studies have shown that voluntary participations resulted in more positive impacts and successful learning outcomes amongst the participants. For example, the Master’s in Teaching and Learning degree for school teachers in the United Kingdom was a government-led intervention and was designed by higher education institutions as a professional development for teachers. The practice-focused programme was met with enthusiasm and eager anticipation, particularly by senior teachers who saw the benefits of the programme in increasing their level of thinking and interlacing their practical experience with theoretical knowledge (Burstow and Winch Citation2014). Meanwhile, the Science in the Classroom Partnership programme in the United States, which is funded by the National Science, has been in operation for an astounding 17 years. It partners science teachers from middle school with a scientist from the host university and partner university to co-teach in schools one day per week and two weeks in the summer workshop. Teachers are chosen based on their motivation to participate. Teachers reported that they had gained confidence in their teaching and increased their content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge of the subject matter (Ufnar and Shepherd Citation2019). Thus, if a model is to be used in the evaluation of professional development, it needs to be able to incorporate data on who is required to take part.

Second, the selection method of participants should align with the objectives of the programme. If a professional development programme has two objectives that target two separate skill outcomes, the selection should be conducted using two or more methods of assessment. For example, the two objectives of the ProELT were to enhance teachers’ language proficiency and to develop teachers’ teaching methodology. Therefore, the selection should be based on the results of their language proficiency test and instructional skill assessment such as classroom observations and interviews. However, the second objective of the ProELT seemed generic and non-specific, and there were no valid methods to assess the teachers’ instructional skills to select suitable participants. This explains the second reason for the experienced teachers’ dissatisfaction with the ProELT selection methods, which did not consider their working experience.

Incorporation of principles of adult learning

In Huber’s framework, features of the programme include the didactic features, conception of the programme and realisation of the conception, which is determined by the background conditions element. The didactic features may be divided into macro-didactic and micro-didactic features. Macro-didactic includes programme provider, purpose of professional development, speaker/trainer, duration, and timing, amongst others, while micro-didactic features are formats, contents, methods and media used.

The six adult learning principles include the need to know, learners’ self-concept, learners’ experiences, readiness to learn, orientation to learning and motivation (Knowles Citation1980). The quantitative findings in Hiew and Murray's (Citation2018) study indicated that these six principles were only partially incorporated into the ProELT and the programme did not completely fulfil the learning needs and learning approaches of the teachers. This was supported with findings from the teachers interview and focus group whereby the teachers lamented the lack of relevance of the ProELT coursebook to their curriculum. A cross-check between the coursebook and eleven curricula (six for primary level and five for secondary level) supported the teachers’ claims. Similar reason was reported as part of the weaknesses of the New Opportunities Fund ICT training for United Kingdom teachers (Galanouli et al. Citation2004). It is essential that the design of a professional development programme contain coherent contents in which the learning goals match the designed activities (Hubers et al. Citation2020). These findings justify the addition of the second element (yellow box), incorporation of principles of adult learning, to enhance Huber’s framework in order to ensure that the micro-didactic features are designed according to the learners’ goals and needs instead of the organisation’s goals, unless the programme pertains to the introduction of a new curriculum (Hayes Citation1995). If the latter was the case, therefore, the organisation’s goals would dominate the learning objectives of the participants in order to ensure a successful transfer of knowledge.

Follow-up support

Follow-up support from the programme provider plays a crucial factor during and at the end of a programme to ensure that the transfer of knowledge and implementation of the programme resources in the teachers’ lessons are successful (Garet et al. Citation2001, Higgins and Spitulnik Citation2008, Guskey and Yoon Citation2009, Gerard et al. Citation2011, Van Driel et al. Citation2012). This might include classroom observations, school visits and meetings, amongst others, to discuss arising matters with the participants and to offer necessary advice. In the case of the New Opportunities Fund, part of its notably unsuccessful outcome was reportedly due to poor support from trainers and mentors (Galanouli et al. Citation2004). It is worth bearing in mind that the impact of a programme might not be immediately noticeable because changes to teachers’ instructional practices do not happen overnight (Hayes Citation1995) and are only gradually followed by changes in students’ learning outcomes. This is the reason the third additional element (green box), follow-up support, preceded the impact of the programme element in the enhanced framework.

Comprehensive assessment of programme impact

The impact of the programme element in Huber’s framework presents various aspects and levels for assessing the impact of a programme, namely teachers’ instructional skill, students learning outcomes, and also cooperation and communication among colleagues and the organisation. However, the assessment of the impact should also be comprehensive and based on the objectives of the programme in order to reflect the desired outcomes, with relevant supportive evidence (Guskey Citation2009, McChesney and Aldridge Citation2019). Hence, this justifies the addition of the fourth element (blue box), comprehensive assessment of programme impact, in Huber’s framework. Using the ProELT as an example, the primary objective of the programme was to enhance teachers’ language proficiency in all four skills. Therefore, the pre- and post-CPT and Aptis tests were utilised to gauge the participants’ performance before and after the programme. However, the secondary objective of the ProELT, which was to develop teachers’ teaching methodology, unfortunately did not include either formative or pre-/post-instructional skill assessments. This omission did not permit the investigation of the success or failure of the programme’s secondary objective in regard to each teacher. Previous studies showed that methods for instructional assessment could include classroom observations and/or interviews with the teachers. In addition to these methods, the assessment of impact could even be more rigorous and comprehensive by assessing students’ achievement and learning outcomes using a wide range of indicators such as assessment results, portfolio evaluations, marks or grades, scores from standardised examinations and even behavioural measures such as attitude, attendance and participation in activities (Guskey Citation2003, Desimone et al. Citation2013). There are many excellent examples of professional development that had incorporated comprehensive assessments on teachers’ and students’ changes in behaviour, beliefs and learning outcomes (Desimone et al. Citation2002, Gegenfurtner Citation2011, Dogan et al. Citation2016, Kennedy Citation2016, May et al. Citation2016, Maandag et al. Citation2017)

Situating Huber’s enhanced framework within the context of a developing country

This study took up Huber’s (Citation2011) ‘plea’ for more original research in the field of professional development outside the United States by undertaking a research in South East Asia, particularly in Borneo, Malaysia. The study by Hiew and Murray (Citation2018) and the proposed enhancement of Huber’s framework both contribute to the research, planning and evaluation of teacher professional development programmes in developing countries. Some developing countries have benefited from fully- and partially funded teacher professional development programmes by generous international providers, for example, the large-scale English Language Teaching Improvement Project in Bangladesh, which trained 35,000 out of 60,000 secondary school English teachers between 1997 and 2010, the English for Teaching, Teaching for English project, with the participation of 2,000 primary school teachers from remote districts in Bangladesh (Hamid Citation2010), and the Sri Lanka Primary English Language Project, which aimed to improve the instructional quality of 6,000 primary school English language teachers in teaching basic English (Hayes Citation2000). A smaller scale teacher professional development programme include the Reading Project Partnerships Achieve Literacy (PAL) in South Africa which was designed to transform teachers’ pedagogical practices in literacy instruction in an under-resourced school and subsequently improve students’ reading competency (Flint et al. Citation2019). Cambodia and Vietnam have greatly benefited from international aid through monetary and manpower assistance to rebuild their education systems, which were left with substantial gaps as a result of the grim genocides of the Khmer Rouge era from 1975 to 1979 and the Vietnam War from 1965 to 1975, respectively. Most developing countries are currently able to self-fund locally delivered programmes, while other more financially advantaged countries are able to offer foreign-delivered programmes such as the ProELT. However, research findings on teacher professional development programmes in developing countries revealed mixed outcomes and limited perspectives on the planning and evaluation processes (Mwangi and Mugambi Citation2013).

Our research has led us to the conclusion that Huber’s enhanced framework could offer a more systematic, effective and robust planning and evaluation of professional development programmes in developing countries, whether the programmes are locally or foreign-delivered. At the beginning stage of the planning process, the framework guides programme designers to identify the background conditions of the potential participants, for example, professional needs and educational aims, amongst others, which subsequently influence the features of the programme. Next, the selection of participants element guides programme designers to adopt relevant and sufficient instruments that align with the programme objectives in order to select target-specific participants (i.e. this element also considers their experience, needs and skills). However, it is acknowledged that, on occasions, favouritism and bureaucratic influence are practiced (Zein Citation2016), which might impede an equitable and valid selection process of participants.

Huber’s enhanced framework also allows for a thorough and multi-perspective evaluation of the impact of a programme from a narrow or widened focus, depending on the aim and orientation of the evaluation, such as: (1) the judgement of the programme by the participants, their colleagues and superiors, which could influence the actual participation in the programme; (2) the degree of incorporation of adult learning principles in the programme and features of the programme; (3) participants’ perception of the programme in regard to the (expected) relevance, (expected) usefulness, and (expected) satisfaction; (4) relevant follow-up support; (5) comprehensive assessment methods that align with the programme objectives; and (6) three-level evaluation of the impact of the programme on the school (organisation), the staff and the students, although this does not imply that every single professional development programme should evaluate the impact on all three levels as different programmes evoke different kinds of impact. Hence, this multi-perspective enhanced framework would allow programme designers to select the focus of evaluation that would help to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the programmes, and subsequently further improve the planning and fine-tuning of the conceptions and the implementation of future professional development programmes in developing countries.

Conclusion

This paper has presented an enhanced framework by Huber (Citation2011) for the evaluation of a teacher professional development, with the addition of four new elements namely (1) Selection of participants; (2) Incorporation of adult learning principles; (3) Follow-up support; and (4) Comprehensive assessment of programme impact. The four additional elements were derived from the findings of Hiew and Murray's (Citation2018) study on the one-year ProELT teacher training programme in Borneo, Malaysia. The ProELT included the participation of primary and secondary teachers in the same programme, which was rather unusual for an instructional development programme because primary and secondary level teachers deal with different groups of learners, different pedagogical approaches and different syllabus content. Comparisons were made between Kirkpatrick’s (Citation1994) four-level evaluation model, Adey et al.’s (Citation2004) model of factors which influence the effectiveness of professional development and Huber’s evaluation framework. Each model has its strengths and limitations, but it became evident that Huber’s framework served as a more suitable and robust framework in line with the aim and objectives of Hiew and Murray's (Citation2018) study.

This enhanced framework has practical applications for programme designers and programme providers of teacher professional development. The enhanced framework offers opportunities for more effective and robust planning and designing of a teacher professional development programme by considering suitable methods to select programme participants that align with the programme objective. This is particularly important if the programme is non-voluntary, in order to ensure that the programme fulfils the participants’ professional needs (McElearney et al. Citation2019). In addition, the enhanced framework offers a guide to programme designers and programme providers to consider incorporating Knowles’s (Citation1980) six principles of adult learning into the programme design, namely (1) the need to know; (2) learner’s self-concept; (3) learners’ experience; (4) readiness to learn; (5) orientation to learning; and (6) motivation. By taking into account of the selection method and principles of adult learning, it is pertinent that only target-specific teachers are selected for a programme that will fulfil their professional needs, instead of wasting their time and the programme provider’s funding. It is also vital that the programme designers and programme providers provide continuous follow-up support to the participants either during or after the completion of a programme. This would ensure that the teachers are able to successfully incorporate the knowledge and materials in their classroom. Some programmes do not provide follow-up support probably due to limited funding and manpower and logistics. Finally, the enhanced framework offers a guide for programme designers and programme providers to assess the impact of a programme by aligning an assessment method with the programme objective. For example, if the objective of a programme is to enhance participants’ instructional skills, therefore, a valid assessment tool needs to be selected.

There are two remaining limitations in this enhanced framework. The focus of the study was based on the context in Borneo, Malaysia and on English language teachers. Future studies could perhaps adopt this enhanced framework in other developing countries by exploring and evaluating the impact of a teacher professional development programme for other languages or subjects, on the teachers’ organisations (i.e. schools) and their students’ academic learning outcomes and performances.

Finally, it is worth bearing in mind that the success and failure of a teacher professional development programme in any context does not depend solely on a perfect framework, theory or policy, but on the joint effort, accountability and responsibility of multiple stakeholders who fund, design, deliver, implement, receive and support the innovation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adey, P., et al., 2004. The professional development of teachers: practice and theory. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Balassa, K., Bodo´Czky, C., and Saunders, D., 2003. An impact study of the national Hungarian mentoring project in English language training. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 11 (3), 307–320. doi:10.1080/1361126032000138346

- Birman, B.F., et al., 2000. Designing professional development that works. Educational Leadership, 57, 28–33.

- Bowden, R., 2015. Teacher research in the English language teacher development project. In: S. Borg and H.S. Sanchez, eds. International perspectives on teacher research. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 152–169

- British Council, 2013. Narrative of teacher development: reading and speaking. United Kingdom: British Council.

- British Council, 2015. English language teacher development project [online]. https://www.britishcouncil.org/partner/track-record/english-language-teacher-development-project [Accessed 23 December 2020]

- British Council, n.d. Malaysian Ministry of Education and pro-ELT [online]. https://www.britishcouncil.my/partnerships/success-stories/malaysian-ministry-education-pro-elt [Accessed 23 December 2020]

- Burstow, B. and Winch, C., 2014. Providing for the professional development of teachers in England: a contemporary account of a government-led intervention. Professional Development in Education, 40 (2), 190–206. doi:10.1080/19415257.2013.810662

- Carpenter, T.P., et al., 1989. Using knowledge of children’s mathematics thinking in classroom teaching: An experimental study. American Educational Research Journal, 26 (4), 499–531. doi:10.3102/00028312026004499

- Courtney, J., 2007. What are effective components of in‐service teacher training? A study examining teacher trainers’ perceptions of the components of a training programme in mathematics education in Cambodia. Journal of In-Service Education, 33 (3), 321–339. doi:10.1080/13674580701486978

- Darling-Hammond, L., 1997. Doing what matters most: investing in quality teaching. New York, NY: National Commission on Teaching & America’s Future.

- Desimone, L., Smith, T.M., and Phillips, K., 2013. Linking student achievement growth to professional development participation and changes in instruction: A longitudinal study of elementary students and teachers in Title I schools. Teachers College Record, 115, 1–46

- Desimone, L.M., et al., 2002. Effects of professional development on teachers’ instruction: Results from a three-year longitudinal study. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24 (2), 81–112. doi:10.3102/01623737024002081

- Diamond, B.S., et al., 2014. Effectiveness of a curricular and professional development intervention at improving elementary teachers’ science content knowledge and student achievement outcomes: year 1 results. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 51 (5), 635–658. doi:10.1002/tea.21148

- Dogan, S., Pringle, R., and Mesa, J., 2016. The impacts of professional learning communities on science teachers’ knowledge, practice and student learning: a review. Professional Development in Education, 42 (4), 569–588. doi:10.1080/19415257.2015.1065899

- Dushku, S., 1998. ELT in Albania: project evaluation and change. System, 26 (3), 369–388. doi:10.1016/S0346-251X(98)00024-4

- Dyer, C., 1996. Primary teachers and policy innovation in India: some neglected issues. International Journal of Educational Development, 16 (1), 27–40. doi:10.1016/0738-0593(94)00046-5

- Dyer, C., et al., 2004. Knowledge for teacher development in India: the importance of ‘local knowledge’ for in-service education. International Journal of Educational Development, 24 (1), 39–52. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2003.09.003

- Fennema, E., et al., 1996. A longitudinal study of learning to use children’s thinking in mathematics instruction. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 27 (4), 403–434. doi:10.2307/749875

- Flint, A.S., Albers, P., and Matthews, M., 2019. ‘A whole new world opened up’: the impact of place and space-based professional development on one rural South Africa primary school. Professional Development in Education, 45 (5), 717–738. doi:10.1080/19415257.2018.1474486

- Fullan, M., 2007. The new meaning of educational change. 4th ed. New York, NY: Teachers College Press

- Galanouli, D., Murphy, C., and Gardner, J., 2004. Teachers' perceptions of the effectiveness of ICT-competence training. Computers & Education, 43 (1–2), 63–79. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2003.12.005

- Garet, M.S., et al., 1999. Designing effective professional development: lessons from the Eisenhower program. Washington, DC: American Institute for Research.

- Garet, M.S., et al., 2001. What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 38 (4), 915–945. doi:10.3102/00028312038004915

- Gegenfurtner, A., 2011. Motivation and transfer in professional training: a meta-analysis of the moderating effects of knowledge type, instruction, and assessment conditions. Educational Research Review, 6 (3), 153–168. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2011.04.001

- Gerard, L.F., et al., 2011. Professional development for technology-enhanced inquiry science. Review of Educational Research, 81 (3), 408–448. doi:10.3102/0034654311415121

- Guskey, T.R., 2003. What makes professional development effective? Phi Delta Kappan, 84 (10), 748–750. doi:10.1177/003172170308401007

- Guskey, T.R., 2009. Closing the knowledge gap on effective professional development. Educational Horizons, 87, 224–233.

- Guskey, T.R. and Yoon, K.S., 2009. What works in professional development. Phi Delta Kappan, 90 (7), 495–500. doi:10.1177/003172170909000709

- Hamid, M.O., 2010. Globalisation, English for everyone and English teacher capacity: language policy discourses and realities in Bangladesh. Current Issues in Language Planning, 11 (4), 289–310. doi:10.1080/14664208.2011.532621

- Hargreaves, A. and Fullan, M., 1992. Understanding teacher development. New York, NY: Teacher College Press.

- Hasreena, A.R. and Ahmad, J., 2015. The standard and performance of Professional Upskilling of English Language Teachers programme: an evaluation. International Academic Research Journal of Social Science, 1, 40–47

- Hayes, D., 1995. In-service teacher development: some basic principles. ELT Journal, 49 (3), 252–261. doi:10.1093/elt/49.3.252

- Hayes, D., 2000. Cascade training and teachers’ professional development. ELT Journal, 54, 135–145. doi:10.1093/elt/54.2.135

- Hiew, W. and Murray, J., 2018. Issues with effective design of an ESL teacher professional development programme in Sabah, Malaysia. MANU, 28, 51–76. doi:10.51200/manu.v0i0.1582

- Higgins, T.E. and Spitulnik, M.W., 2008. Supporting teachers’ use of technology in science instruction through professional development: a literature review. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 17 (5), 511–521. doi:10.1007/s10956-008-9118-2

- Huber, S.G., 2011. The impact of professional development: a theoretical model for empirical research, evaluation, planning and conducting training and development programmes. Professional Development in Education, 37 (5), 837–853. doi:10.1080/19415257.2011.616102

- Hubers, M.D et al.2020. Effective characteristics of professional development programs for science and technology education. Professional Development in Education. 1–20. doi:10.1080/19415257.2020.1752289

- Jalleh, 2012. Majority of teachers not proficient in English. The Star, 26 September. https://www.thestar.com.my/News/Nation/2012/09/26/Majority-of-teachers-not-proficient-in-English/ [Accessed 23 January 2020]

- Kennedy, A. and Clinton, C., 2009. Identifying the professional development needs of early career teachers in Scotland using nominal group technique. Teacher Development, 13 (1), 29–41. doi:10.1080/13664530902858485

- Kennedy, C., 1988. Evaluation of the management of change in ELT projects. Applied Linguistics, 9 (4), 329–342. doi:10.1093/applin/9.4.329

- Kennedy, M.M., 2016. How does professional development improve teaching? Review of Educational Research, 86 (4), 945–980. doi:10.3102/0034654315626800

- Khandehroo, K., Mukundan, J., and Alavi, Z.K., 2011. Professional development needs of english language teachers in Malaysia. Journal of International Education Research, 7, 45–52.

- Kirkpatrick, D.L., 1994. Evaluating training programs: the four levels. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Knowles, M.S., 1980. The modern practice of adult education: from pedagogy to andragogy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Cambridge.

- Knowles, M.S., Holton Iii, E.F., and Swanson, R.A., 2005. The adult learner: the definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. In: 6th ed. Boston, MA: Elsevier.

- Lee, H.J., 2004. Developing a professional development program model based on teachers’ needs. Professional Educator, 27, 39–49.

- Lee, O., et al., 2004. Professional development in inquiry‐based science for elementary teachers of diverse student groups. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41 (10), 1021–1043. doi:10.1002/tea.20037

- Lessing, A. and De Witt, M., 2007. The value of continuous professional development: teachers’ perceptions. South African Journal of Education, 27, 53–67.

- Maandag, D., Helms-Lorenz, M., and Lugthart, E., 2017. Features of effective professional development interventions in different stages of teachers’ careers. Netherlands: University of Groningen. Available from: https://www.nro.nl/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Effectivenessof-professional-development-interventions-in-different-teacher-career-stages.pdf

- May, H., et al., 2016. Reading Recovery: an evaluation of the four-year i3 scale-up. CPRE Research Reports. Available from: https://repository.upenn.edu/cpre_researchreports/81/ [Accessed 1 May 2020]

- McChesney, K. and Aldridge, J.M., 2019. A review of practitioner-led evaluation of teacher professional development. Professional Development in Education, 45 (2), 307–324. doi:10.1080/19415257.2018.1452782

- McElearney, A., Murphy, C., and Radcliffe, D., 2019. Identifying teacher needs and preferences in accessing professional learning and support. Professional Development in Education, 45 (3), 433–455. doi:10.1080/19415257.2018.1557241

- Ministry of Education Malaysia, 2013. Malaysia Education Blueprint (2013-2025). Pre-school to post-secondary education. Putrajaya, Malaysia: Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia.

- Mwangi, N.I. and Mugambi, M., 2013. Evaluation of strengthening of mathematics and science in secondary education (SMASSE) program: a case study of Murang’a south district, Kenya. International Journal of Education Learning and Development, 1, 46–60.

- O’sullivan, M.C., 2002. Effective follow-up strategies for professional development for primary teachers in Namibia. Teacher Development, 6 (2), 181–203. doi:10.1080/13664530200200164

- Perkins, J., 2010. Personalising teacher professional development: strategies enabling effective learning for educators of 21st century students. Quick, 113, 15–19

- Quick, H.E., Holtzman, D.J., and Chaney, K.R., 2009. Professional development and instructional practice: conceptions and evidence of effectiveness. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 14 (1), 45–71. doi:10.1080/10824660802715429

- Steffy, B.E. and Wolfe, M.P., 2001. A life-cycle model for career teachers. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 38 (1), 16–19. doi:10.1080/00228958.2001.10518508

- Supovitz, J.A. and Turner, H.M., 2000. The effects of professional development on science teaching practices and classroom culture. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 37 (9), 963–980. doi:10.1002/1098-2736(200011)37:9<963::AID-TEA6>3.0.CO;2-0

- Ufnar, J.A. and Shepherd, V.L., 2019. The scientist in the classroom partnership program: an innovative teacher professional development model. Professional Development in Education, 45 (4), 642–658. doi:10.1080/19415257.2018.1474487

- Uysal, H.H., 2012. Evaluation of an in-service training program for primary-school language teachers in Turkey. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37 (7), 14–19. doi:10.14221/ajte.2012v37n7.4

- Van Driel, J.H., et al., 2012. Current trends and missing links in studies on teacher professional development in science education: a review of design features and quality of research. Studies in Science Education, 48 (2), 129–160. doi:10.1080/03057267.2012.738020

- Zein, M.S., 2016. Government-based training agencies and the professional development of Indonesian teachers of English for young learners: perspectives from complexity theory. Journal of Education for Teaching, 42 (2), 205–223. doi:10.1080/02607476.2016.1143145