ABSTRACT

This study is concerned with repair practices that a teacher and students employ to restore intersubjectivity when faced with interactional problems in a Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) classroom. Adopting a conversation analytic (CA) approach, it examines the interactional treatment of students’ verbal and embodied trouble displays in a video-recorded, teacher-fronted geography lesson held in English at a German high school. At the same time, it explores to what extent the repair practices employed are fitted to this specific interactional context. The analysis shows that students’ verbal trouble displays often result in extensive repair sequences, whereas students’ embodied trouble displays are usually met with teacher self-repair in the transition space. In this way, the latter are resolved much earlier and more quickly. The study further reveals practices like reformulation and translation to be especially useful for repairing interactional problems in classrooms in which a foreign language is used as the medium of instruction. The findings may be of interest for prospective as well as practicing teachers in that they provide relevant insights into how interactional trouble can be successfully managed in (CLIL) classroom interaction.

Introduction

The maintenance of intersubjectivity, viz. co-participants’ shared understanding of interactional events and social reality (e.g. Schegloff Citation1992), is a basic requirement for successful interaction. Problems of speaking, hearing or understanding, which can effect ‘breakdowns of intersubjectivity’ (Schegloff Citation1992, 1299), thus regularly engender repair by the interlocutors (e.g. Schegloff, Jefferson, and Sacks Citation1977; Kitzinger Citation2013). Generally speaking, the impact of interactional trouble may be more immediate in two-party conversation than in multi-party interaction. The ‘multilogue’ (Schwab Citation2011) character of classroom interaction, however, prompts all participants to work towards the (re-)establishment of mutual understanding – not least because it is an essential prerequisite to achieving the interactional goals of collaborative knowledge construction and learning (e.g. Seedhouse Citation2004, 73; Sert Citation2015, 33).

This conversation analytic (CA) study focuses on the interactional management of students’ trouble displays in a geography lesson taught in English at a German high school. Such Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) classrooms (e.g. Nikula, Dalton-Puffer, and García Citation2013), in which content subjects are taught through the medium of a foreign language, differ from ordinary language classrooms in that the overall focus is on content rather than language. Still, the use of a foreign language as the medium of instruction has implications for the learning environment as a whole and is likely to necessitate extra interactional work by both teacher and students to ensure understanding. The study demonstrates how students employ different verbal and embodied practices to display their trouble with co-participants’ contributions to the interaction and it investigates how such trouble displays are interactionally negotiated and collaboratively resolved to restore intersubjectivity. To begin with, I will provide an overview of previous CA research on intersubjectivity and repair in both ordinary conversation and classroom interaction and introduce the data and method employed for the present study. I will then illustrate and discuss the two main types of student trouble displays that emerged from the data: verbal displays of trouble in understanding and embodied displays of trouble in responding. Finally, I will draw some comparisons to related practices for managing intersubjectivity in the classroom and point to possible implications for teacher education.

Intersubjectivity and repair in talk-in-interaction

Conversation analysts generally conceive of intersubjectivity as a local and interactional achievement, brought about by co-participants with recourse to procedural means that are built into the very ‘fabric’ of social interaction (Schegloff Citation1992, 1299, 1338). Most commonly, co-participants display their own and ratify each other’s understanding of the prior turn, the ongoing sequence and the interaction-so-far ‘en passant’ (Schegloff Citation1992, 1300) through the production of sequentially appropriate next turns (cf. also Deppermann Citation2008, 231; Heritage Citation1984, 254–260; Schegloff and Sacks Citation1973, 297–298). Consider the following request/compliance sequence from the beginning of the CLIL geography lesson by way of illustration.

Extract 1. Atlases (Coastal Features 01, 00:11–00:47 min.)

In , the teacher (TEA) initiates a request sequence by asking her students (STUs) to open their atlases. While the teacher herself has some trouble identifying the relevant page numbers (see continuous page flipping and verbal comment in l. 01–06), there is no indication of trouble on part of the students. Instead, they simply begin to open their atlases as soon as the teacher’s turn recognisably reaches its first possible completion point (l. 09), thereby not only complying with the teacher’s request for action but also displaying their understanding of what the teacher had asked them to do. Once all students have opened their atlases at the right double page, the teacher progresses to a lesson-initial recap (l. 21ff.) and in this way implicitly ratifies the students’ understanding of her initiating action as displayed in their responsive conduct.

As a general rule, then, intersubjectivity is implied as long as the progressivity of talk is sustained. Yet, every turn-at-talk may contain or constitute a potential trouble source (e.g. Schegloff Citation1992, 1327) and put intersubjectivity and, by implication, progressivity at risk. Co-participants thus require interactional means to deal with such trouble sources – be it problems of speaking, hearing or understanding – to avert breakdowns of intersubjectivity and keep the interaction going. This is where repair, as the inbuilt ‘self-righting mechanism’ (Schegloff, Jefferson, and Sacks Citation1977, 381) of talk-in-interaction, takes effect. Co-participants can either repair a trouble source in their own talk (self-repair) or a trouble source in another co-participant’s talk (other-repair) and such repairs can either be initiated by the speaker of the trouble source (self-initiation) or by another co-participant (other-initiation) (e.g. Schegloff, Jefferson, and Sacks Citation1977, 363–364; Kitzinger Citation2013, 230–231). Importantly, these different types of initiating and executing repair are neither independent nor symmetrical alternatives. Rather, Schegloff, Jefferson, and Sacks (Citation1977) find that there is a structural preference for self-repair over other-repair and for self-initiation over other-initiation. In their seminal paper on the organisation of conversational repair, they, among other things, note that interactional trouble is most commonly addressed and resolved by the speaker of the trouble source within the same turn or its transition space (i.e. first position) (Schegloff, Jefferson, and Sacks Citation1977, 369), as in the case of the teacher’s self-initiated self-repair of the trouble source twelve (l. 01) in above. In contrast, repair initiations by co-participants in the next turn (i.e. second position) tend to be withheld to prolong the opportunity space for self-initiated repair (Schegloff, Jefferson, and Sacks Citation1977, 374–375) and result in side sequences, as they typically entail self-repair by the trouble source speaker in the turn after next (i.e. third position) (Schegloff, Jefferson, and Sacks Citation1977, 377).

While the foregoing observations on the management of intersubjectivity in talk-in-interaction are mainly based on data from ordinary conversation, they appear to be equally applicable to other interactional contexts, including different types of classroom interaction (e.g. Dalton-Puffer Citation2007, 234; Gardner Citation2013, 603). Yet, it has also been shown that classroom interaction, like other types of institutional talk (e.g. Heritage Citation2005, 109), features a specialisation of certain interactional practices and organisations, among others in the area of repair (Gardner Citation2013, 594). Previous studies on the organisation of repair in classroom interaction, which largely focused on the correction of erroneous or inadequate student responses (e.g. McHoul Citation1990; Jung Citation1999; Dalton-Puffer Citation2007; Kääntä Citation2010), have, for instance, found other-initiation and other-repair to occur more frequently than in ordinary conversation (Gardner Citation2013, 604; cf. also Kasper Citation1985; van Lier Citation1988; McHoul Citation1990). The fact that this observation mainly pertains to the repair of student rather than teacher contributions suggests an interactional asymmetry of participation, as is typical for institutional contexts (e.g. Heritage Citation1997, 175). Studies addressing the repair of teacher talk, albeit relatively scarce, point in a similar direction: It is usually teachers themselves who initiate and accomplish repair operations dealing with potential or actual trouble sources in their own contributions – either in first position to pre-empt possible problems of understanding (e.g. Kasper Citation1985) or in third position to pursue a more adequate student response (e.g. Zemel and Koschmann Citation2011; cf. also Lee Citation2006, Citation2007). In contrast, student repair initiations relating to trouble sources in teacher contributions, which may, for instance, take the form of candidate understandings and clarification requests (e.g. van Lier Citation1988, 198, 207; Liebscher and Dailey-O’Cain Citation2003, 384, 386; Kääntä and Kasper Citation2018) or a combination of embodied noticing and verbal correction-initiation (Kääntä Citation2014), are oriented to as dispreferred and ordinarily yield teacher self-repair in third position. Perhaps as a means to counteract this dispreference, teachers have been found to commonly employ understanding-checks (Koole Citation2010; Waring Citation2012) to afford opportunities for students to initiate repair.

It is worth noting that research on intersubjectivity and repair in instructional contexts, but also beyond, has so far mainly centred on verbal repair initiations. Related bodily-visual practices, which may occur alongside or in absence of talk (Sert Citation2015, 89), are only recently coming into focus. As with research on repair in classroom interaction more generally, most studies of embodied repair have addressed instructors’ resources for displaying trouble with (erroneous) student contributions. These include the withholding of relevant next actions and shifts in gaze or posture (Kääntä Citation2010), forward leans and ‘hand to ear’ gestures (Mortensen Citation2012) as well as head tilts, turns and pokes (Seo and Koshik Citation2010; cf. also Mortensen Citation2012). Studies of embodied trouble displays on part of the students, on the other hand, are still scarce. Two notable exceptions are the abovementioned study by Kääntä (Citation2014), which illustrates how students display their noticing of teacher errors through a combination of sudden gaze shifts, puckered lips and frowns, and a study by Sert (Citation2013), which shows how teachers treat combinations of long silences with students’ gaze withdrawals, smiles or head shakes as displays of insufficient knowledge and react to them with (negative) ‘epistemic status checks’, which ultimately allow them to reallocate the turn to a different student.

In light of the current state of research, it appears worthwhile to explore the range of multimodal resources that students avail themselves of to display interactional trouble in order to gain a broader picture of how mutual understanding can be successfully negotiated in classroom interaction.

Data and method

The present study is based on a video recording of a 45-minute teacher-fronted CLIL lesson taught in English at a German high school.Footnote1 It is a tenth-grade geography lesson from a teaching unit on the coastal features of the British Isles. The students are between 15 and 16 years of age, have been learning English for six years in a regular EFL classroom and are now attending the school’s CLIL branch.

The data are analysed within the theoretical and methodological framework of ethnomethodological Conversation Analysis (CA) (e.g. Sidnell and Stivers Citation2013) with due consideration of the various verbal, vocal and bodily-visual resources employed. CA starts from the premise that its object of investigation, social interaction, is highly orderly (e.g. Sacks Citation1984, 22) and that this orderliness renders every interactional detail potentially relevant (cf. also Sidnell and Stivers Citation2013, 2). Furthermore, CA proceeds on the assumption that social interaction is jointly accomplished by participants on a turn-by-turn basis and that every contribution to the interaction is both context-shaped and context-renewing (e.g. Heritage Citation1984, 242). Relying on inductive micro-analyses of recorded and transcribed excerpts taken from naturally occurring talk-in-interaction, CA aims to identify the underlying structures of social interaction and to describe the organisation of social actions and activities (e.g. Sidnell and Stivers Citation2013, 2). To this end, CA scholars assemble collections of similar cases and search for recurrent patterns without losing sight of each single instance in the process (e.g. Sidnell Citation2013, 77–78). Importantly, CA analyses are exclusively based on data-internal evidence, including the sequential context, co-occurring (multimodal) resources, participant orientations displayed in subsequent talk and comparisons to alternative practices. In addition, deviant cases are not simply glossed over but treated as evidence in their own right (e.g. Sidnell Citation2013, 79–82). A multimodal CA approach, then, appears to be particularly suited to enhance our understanding of how teaching and learning are interactionally organised and achieved in the (CLIL) classroom (e.g. Evnitskaya and Jakonen Citation2017).

For the purpose of the present study, instances in which students observably display trouble with another participant’s interactional contribution and which are oriented to as such by the co-participants were collected through careful data inspection.Footnote2 Since the focus is on the negotiation of mutual understanding, cases of student-initiated correction which are clearly framed as exclusively dealing with problems of acceptability were excluded from the collection. All instances were then transcribed according to GAT 2 transcription conventions for English (cf. Couper-Kuhlen and Barth-Weingarten Citation2011). Relevant bodily-visual conduct which is simultaneous with verbal conduct is displayed on a separate line using a different font and a lighter font colour. It is aligned with the verbal transcript using a combination of vertical bars (‘|’), which mark its starting and end points, and underscores (‘_’), which depict its extension (cf. Selting et al. Citation1998). Modified still frames were included on occasion for a holistic representation of bodily-visual practices.

The interactional management of students’ trouble displays

As a matter of course, students may display trouble with a co-participant’s contribution in different positions and sequential contexts. In the current data set, most trouble displays are found in the response slot of Initiation-Response-Feedback (IRF) instructional sequences (Sinclair and Coulthard Citation1975). However, students’ trouble displays also occur subsequent to complete IRF sequences or at activity boundaries, in parallel to other participants’ contributions or in response to understanding-checks by the teacher. Depending on their sequential position and the interactional resources employed, such trouble displays engender different repair trajectories. In the course of the analysis, two broad sub-types of student trouble displays were identified: verbal displays of trouble in understanding and embodied displays of trouble in responding. While the former type is relatively well-attested in the literature on other-initiated repair (OIR) in the classroom (e.g. Kääntä and Kasper Citation2018; Liebscher and Dailey-O’Cain Citation2003; van Lier Citation1988; cf. Dingemanse, Blythe, and Dirksmeyer Citation2014; Kendrick Citation2015; Schegloff, Jefferson, and Sacks Citation1977 for verbal OIRs in ordinary conversation), the latter type – although predominant in the present data set – has so far only been described in conjunction with epistemic status checks and a slightly diverging set of bodily-visual practices (Sert Citation2013). Below, I will provide examples for each of the two major sub-types and explore their distinct interactional treatment. Another sub-type, namely students’ covert trouble displays to their neighbours, which can be conceived of as a transitional or hybrid form between verbal and embodied trouble displays, will only be touched upon briefly (see ) due to the limited scope of this paper.

Verbal displays of trouble in understanding

The first sub-collection of students’ trouble displays, which I will refer to as verbal displays of trouble in understanding, includes instances of clarification requests (e.g. Kääntä and Kasper Citation2018) and negative epistemic claims or formulations (e.g. Lindström, Maschler, and Pekarek Doehler Citation2016; Mondada Citation2011). In contrast to the entirely embodied trouble displays discussed below, students’ verbal trouble displays make explicit that there is a problem of understanding relating to another participant’s contribution. While students may proactively bid for a turn to address their understanding problems, verbal trouble displays may also be elicited by the teacher through understanding-checks or the selection of non-bidding students. On occasion, they may be preceded by more implicit bodily-visual trouble displays.

contains two verbal displays of trouble in understanding which are uttered by different students. The current activity, which revolves around a map of Great Britain that is projected on the wall (see ), has already been going on for a while and now appears to be coming to an end. The students’ task was to describe the map, which shows the height of storm surge above the predicted spring high tide level, and to explain where the danger lies for a certain coastal region. One of the students, Mirko, has just provided an explanation for why the tidal range is especially high in the affected area, as had previously been hinted at by the teacher. Mirko’s explanation is accepted by the teacher and followed up with complementary comments and a summarising statement. This is where sets in.

Extract 2. Why is that (Coastal Features 04, 01:45–03:09 min)

At the beginning of above, the current activity is noticeably approaching a possible completion point: Shortly before, the teacher had not only received a response to her (re)initiationFootnote3 but also accepted it publicly and highlighted its central aspects for the whole class with reference to the map under discussion. Her summarising statement in l. 01–06 reaffirms her approval of Mirko’s explanation without inviting further contributions, thereby treating the matter as sufficiently discussed and proposing sequence-closure. In line with her verbal contribution, the teacher’s bodily conduct also implies upcoming closure in that her extensive arm gesture is retracted step by step (e.g. Mondada Citation2015): After pointing at Mirko with her left arm, she points at the projection of the map with her right arm while retracting her left arm and finally, she drops her right arm while directing her gaze back at the class. The 1.6 sec. pause in l. 07, in which the teacher remains in her position, keeps her gaze on the class and continues to hold her retracted left arm at chest level, can be seen to establish an opportunity space for repair initiation before moving on to the next activity. As Kääntä and Kasper (Citation2018, 6) point out, such opportunity spaces are commonly afforded by the imminence of activity transitions and can, but need not, be made explicit through understanding-checks (cf. also Koole Citation2010; Waring Citation2012). In the present excerpt, the teacher does issue a delayed understanding-check (did you understand, l. 10), which is accompanied by a slight forward lean and addressed directly to one of the students (celine, l. 08). Considering Celine’s (CEL) slumped head-in-hand posture as she comes into sight (see Fig. 3), we may tentatively assume that this directed understanding-check was preceded by an embodied trouble display outside the camera view. In response to the teacher’s understanding-check, Celine claims insufficient understanding (not really, l. 12), thereby inhibiting sequence-closure. She does, however, not make her actual problem explicit. The teacher registers Celine’s negative epistemic display by repeating it (l. 14) but does not attempt to repair the apparent problem of understanding herself. Instead, she passes the turn on to Mathilde (MAT) (l. 16), who had raised her hand shortly after (l. 15). It thus appears that next-speaker selection is one strategy that teachers may employ when confronted with verbal trouble displays in the classroom. Yet, this strategy may not necessarily have the desired effect. In the present excerpt, it simply results in a deferred repair solution, since Mathilde bids for the turn to address her own problem of understanding rather than Celine’s.

Mathilde’s verbal trouble display is composed of a detailed negative epistemic formulation (i don’_understand X, l. 17–22) and a clarification request (why is that, l. 24). It is neither preceded nor accompanied by bodily-visual trouble indicators. In contrast to Celine’s trouble display, it clearly calls for trouble resolution and makes relevant a responsive action. This time, the teacher does not delegate the turn to another student but does not provide a straightforward response either. Instead, she invites Mathilde to have a try at solving the problem herself (but you could help yourself, l. 27), not without giving her some further hints with reference to the map (l. 29–41). The teacher concludes her scaffolding (Wood, Bruner, and Ross Citation1976) with a multimodal prompt composed of a stand-alone so (l. 43) (Raymond Citation2004), a term of address (l. 45) and an open palm gesture (l. 46). In response, Mathilde provides the projected formulation of upshot (l. 47), which is then ratified by the teacher (l. 48). Even though the teacher could simply treat the trouble as resolved now that the student who initiated the repair sequence has demonstrated sufficient epistemic access, she does not move on right away but instead restates the solution to Mathilde’s problem of understanding for the whole class (l. 51–53). She thereby orients to the fact that classroom interaction is a ‘multilogue’ (Schwab Citation2011) involving multiple participants, whose shared understanding is important for the learning process. Notably, the teacher does not invite further contributions at this point and thus implicitly proposes sequence-closure for the second time, which takes us back to the point of departure. The example thus shows that verbal trouble displays can be successfully managed by means of scaffolding: The provision of additional cues may facilitate students’ understanding and guide them towards resolving their trouble at least halfway by themselves.

Another way of managing students’ verbal trouble displays, namely direct repair by the teacher, will be illustrated in the following. Since the verbal trouble display in this extract is preceded by a marginal instance of a covert trouble display to a neighbour (see above), this aspect will be briefly touched upon in this context as well. The excerpt is taken from an earlier stage of the same map-related activity as above. One student, Frida (FRI), is in the process of verbalising a content-related problem of understanding.

Extract 3. What does predicted mean (Coastal Features 03, 04:54–05:33 min)

As mentioned above, begins with a verbal display of trouble in understanding by Frida, which will, however, not be addressed further here. The excerpt sets in at the end of Frida’s contribution, which contains several instances of the word predicted, the last one in l. 01. Notably, this word is not only relevant for understanding Frida’s contribution but also for the ongoing map activity as a whole. In l. 04, Marie (MAR) quietly claims not to know the meaning of the trouble-source word predicted in overlap with Frida’s turn (the camera view does not show who this negative epistemic claim is directed at). When Marie comes into sight (l. 09), she is raising her hand, but even though the teacher’s turn noticeably reaches completion in l. 11, Marie’s bid for the next turn is not accepted at first (it may have been overlooked by the teacher, who is outside the camera view). In the ensuing pause (l. 13), Marie first continues to raise her hand, but once her neighbour Levke turns to her, she retracts it and instead leans over to and establishes mutual gaze with Levke (see Fig. 4). While Marie appears to be saying something, this might at best be perceivable as a soft murmur for the other participants. Still, her bodily conduct is clearly observable for onlookers and may thus be recognised and taken up as a potential trouble display. Since the teacher only comes into view in l. 25, it is not clear, though, whether she orients to Marie’s prior hand raise or the covert trouble display to her neighbour when selecting her as the next speaker in l. 14.

Upon her selection, Marie issues a clarification request (what does predicted mean, l. 17), thereby publicly displaying her trouble in understanding. In contrast to the previously discussed verbal trouble displays, Marie’s repair initiation is straightforwardly followed by next-turn teacher repair in form of a word definition (you tell something in advance, l. 19). But similar to the second example in , the teacher does not leave it at that, despite the fact that Marie almost immediately claims sufficient understanding, both verbally (okay, l. 21) and visually (nodding, gaze aversion, observably preparing to take a note, l. 21–24). Instead, the teacher elaborates her definition, calls for a translation of the trouble-source word to German and even dips into the students’ knowledge of Latin by pointing out the word’s derivational morphology (not shown in transcript) before she reinitiates the original task. This once again shows that the teacher ultimately orients to the whole class rather than individual students, which is underlined by her gaze behaviour as well (l. 27). Moreover, this example suggests that the CLIL context may afford different kinds of trouble and practices to resolve trouble compared to monolingual instructional settings: In this specific interactional context, translating may usefully complement other repair operations like repeating or reformulating.

Overall, it was observed that verbal displays of trouble in understanding entail relatively complex repair trajectories: The trouble display generally leads to a side sequence that extends over two or more turns, depending on whether the repair is accomplished by the teacher in the next turn, delegated to another student or passed back to the student who initiated the repair sequence. Commonly, displays of epistemic access by the original producer of the trouble display do not yield immediate sequence-closure. Instead, the teacher typically delivers (or calls for) further explanations, reformulations or translations of relevant terms for the whole class. Whether this tendency towards thorough clarification is a characteristic feature of CLIL classroom interaction or also found in ‘regular’ L1 or L2 classrooms remains to be examined. Apart from their extensive trajectories, students’ verbal trouble displays are also characterised by their delayed placement relative to the trouble-source turn. Finally, they occur considerably less frequently than the embodied trouble displays to be discussed in the following. It thus appears that students’ verbal trouble displays are indeed oriented to as dispreferred (cf. Kääntä Citation2014; McHoul Citation1990, 376; van Lier Citation1988, 207; Waring Citation2012, 737).

Embodied displays of trouble in responding

The second sub-type of students’ trouble displays which emerged from the data, and which I will refer to as embodied displays of trouble in responding, covers a wide range of bodily-visual practices that co-occur with relatively long pauses at transition-relevance places (TRPs) of teacher-initiations.Footnote4 These practices include gaze aversion, frowning, slumped head-in-hand postures, chin or lip stroking, head scratching and unsolicited engagement with learning materials, among others. Unlike the explicit verbalisations of trouble in understanding discussed above, embodied displays of trouble in responding cannot unambiguously be traced back to problems of understanding. Still, the teacher treats noticeably absent student responses in combination with such embodied conduct as displaying trouble with her initiation-so-far in that she subsequently extends or reformulates (part of) her turn.Footnote5

exemplifies how students’ embodied displays of trouble in responding can manifest themselves and demonstrates how such implicit trouble displays are typically negotiated and resolved. The current activity is a recap at the beginning of the lesson. The teacher has just worked out the overall topic of the current teaching unit (Coastline features of the British Isles) together with her students. In the following, she seemingly attempts to get at a subtopic that they had been concerned with in past lessons, namely the impact of certain natural processes on the British coastline. To this end, she refers back to the tides, which had already been brought up by one student in the course of establishing the unit’s overall topic.

Extract 4. Southampton (Coastal Features 01, 03:09–04:06 min)

The beginning of above marks an intra-activity shift from assigning a label to the entire teaching unit to establishing a subtopic that had apparently been discussed in previous lessons. The teacher seems to be facing some difficulties in phrasing what emerges as the initiation of a new IRF sequence, as indicated by the high density of self-initiated self-repairs in l. 03–08. Still, she successfully brings her turn to a possible completion in l. 07–08: After producing two syntactically, prosodically and pragmatically complete interrogatives in short succession, she stops speaking while continuing to look at her students (see Fig. 5b). Despite this being a clear TRP, no student response appears to be forthcoming. In l. 12, the teacher then repeats part of her original initiation – most likely in reaction to the unintelligible student utterance in l. 10 or the overall lack of response. What follows is a long pause in which no one bids for the turn and several students display that there is trouble of some sort through their bodily conduct (l. 15): While the teacher’s gaze is on the class, many students avert their gaze and, for instance, casually occupy themselves with the learning materials on their desks instead. Other students, including the most clearly visible ones, Marie (MAR), Kira (KIR) and Frida (FRI), are furrowing their brows, looking back and forth between their notes and the teacher, sitting in a slumped posture and/or resting their heads in their hands. These co-occurring bodily-visual cues at a point in the interaction where a student response was clearly projected are oriented to as trouble indicators by the teacher. Notably, she treats her own turn as the trouble source and reformulates it (l. 17–19), thereby continuing to pursue a student response. The reformulation is again followed by a long pause (l. 20), but this time around, Marie bids for the turn, gets selected by the teacher (l. 21) and provides a (rather specific) response (l. 22ff.), which is later on acknowledged and taken to a more general level by the teacher (not shown in transcript). thus aptly illustrates how imminent interactional trouble, as displayed by the combination of a collective non-response and certain bodily-visual cues, can be averted through teacher self-repair in the transition space.

Another example for the emergence and interactional treatment of students’ embodied trouble displays is provided in . Teacher and students are still talking about natural processes that impact the British coastline, but have now progressed from talking about tides (–) to talking about the creation of waves. The teacher has brought the technical term fetch into play and not only asked the students to define it but also to identify the longest fetch affecting the British Isles. Just prior to the current excerpt, teacher and students have collaboratively established that the longest fetch comes from the Atlantic Ocean.

Extract 5. Dangerous fetch (Coastal Features 05, 04:21–04:54min)

In l. 02 of above, the teacher initiates a new IRF sequence, asking her students to assess the danger that the longest fetch poses for the British coast. After a 1.2 sec-pause (l. 03), she adds an increment (l. 04), specifying that she is referring to the creation of waves in particular. What follows is a long pause in which no student response seems to be forthcoming (l. 05). While the teacher’s gaze is, once again, on the class, most students – at least the ones visible – are looking down, some of them resting their faces in or against their hands (see Fig. 7). In l. 06, the teacher adds another increment to her turn, now specifying the comparandum. This is again followed by a long pause, in which the student response is noticeably absent (l. 07). Almost all students are – still or again – looking down, except for Mirko (MIR), who looks up while rubbing his chin. Many students are sitting with slumped shoulders and resting their faces on or in their hands in various ways (see Fig. 8), apart from Marie (MAR), who first scratches her head and then sways it slightly from side to side while furrowing her brow and keeping her gaze to her notebook. These enduring visual cues in combination with the overall lack of student response seemingly induce the teacher to launch yet another turn expansion (l. 08–09). She, however, interrupts herself, perhaps because she becomes aware of Lucas’ (LUC) bid for the turn. Once she selects him as the next speaker (l. 11), he provides the projected response (l. 12). Although it later turns out not to be the desired response, it still treats the teacher’s question as sufficiently understood and thus allows the sequence to continue.

One final example of an embodied display of trouble in responding is provided in . It differs from the previous examples in that the teacher’s initiation, a follow-up inquiry, is targeted at a specific student, namely Lucas (LUC), who had just provided a multimodal explanation of how the tides come about in front of the class (cf. Kupetz Citation2011 for a detailed analysis of this case). This specific context appears to facilitate a closer coordination of interactional conduct between teacher and student than whole-class interaction.

Extract 6. Specialities (Coastal Features 02, 04:11-04:35min)

With her turn at the beginning of (l. 01–06), the teacher seemingly pursues an account for the occurrence of spring tides from Lucas, who is standing next to her.Footnote6 The teacher’s initiation could be complete after specialities (l. 01), but her level intonation, gaze direction and the latched uh project turn continuation. However, she only increments her turn (l. 02) after a 1.1 sec. pause, now keeping her gaze on Lucas, who is looking down and fiddling with a pen. While the teacher may have missed Lucas’ potential trouble display in the shape of a thoughtful eye roll (see Fig. 9a for her gaze direction), she appears to be orienting to his ‘temporising’ bodily-visual conduct now in that she only tentatively offers him the turn by employing level rather than clearly turn-yielding final intonation (l. 02). It is, however, not until another relatively long silence has passed (l. 03) that she replaces the potential trouble source specialities (l. 01) with an alternative term (exceptions, l. 04), whereupon Lucas almost immediately displays that his trouble in responding has been resolved: He first visually gears up to take the turn (end of l. 04) and then begins to respond (l. 05) while embodying his change-of-state (see raised eyebrows, Fig. 10).

Taken as a whole, students’ embodied displays of trouble in responding, which occur comparatively frequently in the current data set, are usually resolved fairly quickly. Unlike the verbal trouble displays described above, they do not result in side sequences but are typically met with teacher self-repair in the transition space. The teacher thus accepts responsibility for the trouble and treats students’ apparent difficulties in responding as displaying lack of understanding rather than, say, lack of knowledge or reluctance to participate. In most cases, the teacher is successful in pursuing a student response by reformulating or extending her initiation in that students begin to bid for the turn at the next TRP or the TRP after next. Overall, it thus appears that the teacher’s orientation to students’ embodied trouble displays, which are commonly placed in close vicinity to the trouble-source turn, can aid in early trouble recognition and resolution and possibly pre-empt explicit claims of non-understanding and longer halts in progressivity. While embodied displays of trouble in responding are clearly instances of student-initiated repair, the exclusively bodily-visual mode allows for a repair trajectory that closely resembles that of self-initiated teacher-repair in first position.

Discussion and conclusion

As pointed out at the outset, most of the previously described practices for student-initiated repair, including clarification requests and negative epistemic claims, fall into the realm of what I have referred to as verbal displays of trouble in understanding. The present study, however, highlights another way in which students may initiate repair in the (CLIL) classroom, namely through embodied displays of trouble in responding. It thus substantiates that embodied practices can be used as repair initiations in their own right (i.e. in the absence of talk), not only by teachers (Kääntä Citation2010; Seo and Koshik Citation2010; Mortensen Citation2012) but also by students.Footnote7 In contrast to students’ verbal trouble displays, which typically result in extensive repair sequences, students’ embodied trouble displays allow for early trouble recognition and are commonly resolved by teacher self-repair in the transition space. It thus appears that the revision of teacher initiations in the service of pursuing (adequate) student responses is not restricted to third position (Zemel and Koschmann Citation2011) but similarly effective in first position. Importantly, there seems to be some overlap between the embodied displays of trouble in responding described in the present study and the embodied displays of insufficient knowledge described in Sert’s (Citation2013) study on ‘epistemic status checks’. Interestingly enough, Sert (Citation2013, 20, 25) also mentions lack of understanding and unwillingness to participate (UTP) as alternative interpretations for some of his cases (cf. also Sert Citation2015, chap. 4). It might thus be worthwhile to explore the extent to which teacher self-repair in the transition space and ‘epistemic status checks’ can, at least in some cases, be seen as alternative practices for handling students’ embodied trouble displays and if so, on what grounds teachers choose one practice over the other in particular sequential contexts.

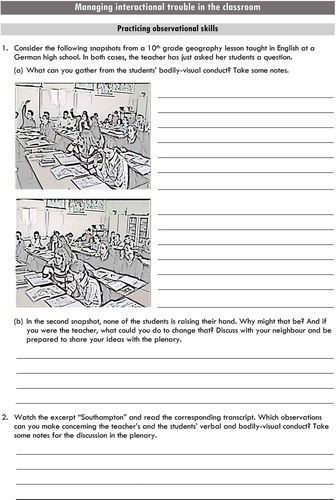

All in all, the findings clearly point to the importance of raising (prospective) teachers’ awareness for the fine details of classroom discourse, including the various multimodal resources that may be employed by students to negotiate meaning and mutual understanding (cf. also Kupetz Citation2011; Sert Citation2013). As the present study suggests, teachers’ orientation to early trouble-indicating cues in the students’ embodied conduct can effectively contribute to restoring and maintaining intersubjectivity and progressivity in the classroom and thereby facilitate collaborative knowledge construction and learning. Hence, teachers should be made aware of students’ use of both verbal and bodily-visual practices for displaying trouble and of possible strategies for their interactional treatment in order to promote successful classroom management. Suggestions for how such awareness-raising could be implemented in teacher training include an introduction to the very basics of CA along with guided micro-analyses of video-recorded and transcribed classroom data taken from the (prospective) teachers’ own or other teachers’ lessons and critical reflections on teachers’ and students’ interactional conduct (cf. also Huth et al., this volume). A concrete proposal for how (prospective) teachers could be encouraged to think and talk about the constitution and interactional management of students’ trouble displays is provided in the Appendix in the form of an exemplary worksheet which is composed of two exercises (see ).Footnote8 The first exercise revolves around two antithetical still frames from the current data set: The ‘unproblematic’ one shows several students raising their hands and others looking up and/or orienting to the front; the ‘trouble-implicative’ one shows a collective non-response with several students looking down and resting their heads in their hands (see ). This exercise (a) invites (prospective) teachers to engage in very basic micro-analyses by calling their attention to the students’ bodily-visual conduct and (b) taps into their intuitions by asking them to reflect on possible trouble sources and trouble solutions with regard to the second still frame. The second exercise goes one step further: It provides (prospective) teachers with audio-visual data and a broader sequential context in which interactional trouble unfolds (see ). This exercise, which is particularly versatile and can be carried out using different data excerpts,Footnote9 allows instructors to guide teacher trainees towards analysing the emergence and interactional treatment of students’ trouble displays by drawing on data-internal evidence. Analysing several good (and bad) practice examples in a similar manner as part of a larger teaching unit on interactional trouble management may not only raise (prospective) teachers’ awareness for students’ employment of multimodal resources in classroom interaction but also enable them to deduce implications for their own teaching practice in terms of concrete interactional strategies for managing students’ trouble displays.

Despite this study being based on CLIL data, the findings are thought to be of relevance for other types of classroom interaction as well, since the verbal and embodied practices that are found in students’ trouble displays in the CLIL context are probably not restricted to this interactional setting. Still, it appears that at least some of the repair sequences are both occasioned and shaped by the CLIL constellation (see ). Future research comparing students’ trouble displays in more traditional L1 and L2 classrooms to those in the CLIL classroom will likely yield more definite results. Overall, it is hoped that the present study has not only made a valuable contribution to this field of research and raised issues that may be of interest for scholars and (prospective) teachers alike but also inspired teacher trainers to incorporate CA findings into their teacher training seminars in an accessible manner.

Acknowledgement

First and foremost, I would like to thank the editors of this special issue, Karen Glaser, Maxi Kupetz and Hina You, for allowing me to take part in this undertaking and for being very supportive in the process. I am also grateful to the participants of the symposium “ARTE 2017”, my colleagues at University of Potsdam and the two anonymous reviewers for providing helpful comments and feedback on earlier versions of this paper. Special thanks go to Constanze Lechler, who was my research partner in a project that inspired this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marit Aldrup

Marit Aldrup is currently a lecturer and PhD student at the chair of Communication Theory and Linguistics in the Department of German Studies at University of Potsdam, Germany. Her research interests include language teaching, language learning and language use in interaction at large. While her main focus is on how linguistic and other interactional resources are employed in English and German talk-in-interaction, she is also interested in how the findings of (multimodal) Conversation Analysis and (comparative) Interactional Linguistics can be applied in language education and intercultural communication.

Notes

1. See Video catalogue of the English Department (English Didactics) at Leibniz University Hanover. 2003. Coastal features: Geografieunterricht auf Englisch (10. Klasse Gymnasium). Hannoveraner Unterrichtsbilder (HanUB) CD 38, no. 21. I would like to thank Maxi Kupetz for making this recording available to me.

2. The recording was made using a single, moving camera which alternatingly captures either the teacher or (parts of) the class. Given the limited camera perspective, it is likely that some trouble displays could not be analysed in every detail or were even overlooked (see Mondada Citation2013 for the advantages of static multi-source recordings), especially those that are negotiated among the students without involving the teacher. Thus, the analysis is by no means exhaustive.

3. Note that the teacher had already amended her original task description several times and provided additional explanations.

4. In a less teacher-fronted setting, such embodied displays of trouble in responding might also occur in the context of student-initiations, however – for instance during group work.

5. The ambiguity of these embodied trouble displays also manifests itself in alternative treatments of similar practices as indicating reluctance or unwillingness to participate (e.g. you’re very very talkative i must say this morning as an ironic comment on low student participation) or lack of knowledge (e.g. well i guess you are looking for the right pages now in reaction to students’ vigorous page flipping in the response slot). Cf. also Sert (Citation2015, chap. 4).

6. Note that standing may create different affordances for embodied trouble displays than sitting.

7. And perhaps more commonly in instructional contexts than in ordinary conversation (cf. Kendrick Citation2015, 178; Kitzinger Citation2013, 251).

8. While both exercises on the exemplary worksheet focus on students’ embodied trouble displays, students’ verbal trouble displays could be addressed in a similar way: Instructors could, for instance, first confront teacher trainees with an ‘isolated’ verbal trouble display (e.g. what does predicted mean, see Extract 3), ask them to reflect on possible trouble sources and solutions and then provide them with one or several longer excerpts for analysis (e.g. Extract 2 or 3).

9. Generally, instructors are recommended to replace the still frames and data excerpts with material that is readily available to them.

References

- Couper-Kuhlen, E., and D. Barth-Weingarten. 2011. “A System for Transcribing Talk-in-Interaction: GAT 2. Translated and Adapted for English.” Gesprächsforschung - Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 12: 1–51.

- Dalton-Puffer, C. 2007. Discourse in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) Classrooms. Language Learning & Language Teaching 20. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Deppermann, A. 2008. “Verstehen Im Gespräch.” In Sprache - Kognition - Kultur: Sprache zwischen mentaler Struktur und kultureller Prägung, edited by H. Kämper and L. Eichinger, 225–261. Jahrbuch des Instituts für Deutsche Sprache 2007. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Dingemanse, M., J. Blythe, and T. Dirksmeyer. 2014. “Formats for Other-Initiation of Repair across Languages: An Exercise in Pragmatic Typology.” Studies in Language 38 (1): 5–43. doi:10.1075/sl.

- Evnitskaya, N., and T. Jakonen. 2017. “Multimodal Conversation Analysis and CLIL Classroom Practices.” In Applied Linguistics Perspectives on CLIL, edited by A. Llinares and T. Morton, 201–220. Language Learning & Language Teaching 47. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Gardner, R. 2013. “Conversation Analysis in the Classroom.” In The Handbook of Conversation Analysis, edited by J. Sidnell and T. Stivers, 593–611. Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Heritage, J. 1984. Garfinkel and Ethnomethodology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Heritage, J. 1997. “Conversation Analysis and Institutional Talk: Analysing Data.” In Qualitative Research: Theory, Method and Practice, edited by D. Silverman, 161–182. London: Sage Publications.

- Heritage, J. 2005. “Conversation Analysis and Institutional Talk.” In Handbook of Language and Social Interaction, edited by K. L. Fitch and R. E. Sanders, 103–147. LEA’s Communication Series. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Jung, E. H. S. 1999. “The Organization of Second Language Classroom Repair.” Issues in Applied Linguistics 10 (2): 153–171.

- Kääntä, L. 2010. Teacher Turn Allocation and Repair Practices in Classroom Interaction: A Multisemiotic Approach. Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities 137. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

- Kääntä, L. 2014. “From Noticing to Initiating Correction: Students’ Epistemic Displays in Instructional Interaction.” Journal of Pragmatics 66: 86–105. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2014.02.010.

- Kääntä, L., and G. Kasper. 2018. “Clarification Requests as a Method of Pursuing Understanding in CLIL Physics Lectures.” Classroom Discourse 9 (3): 205–226. doi:10.1080/19463014.2018.1477608

- Kasper, G. 1985. “Repair in Foreign Language Teaching.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition 7 (2): 200–215. doi:10.1017/S0272263100005374.

- Kendrick, K. H. 2015. “Other-Initiated Repair in English.” Open Linguistics 1 (1): 164–190. doi:10.2478/opli-2014-0009.

- Kitzinger, C. 2013. “Repair.” In The Handbook of Conversation Analysis, edited by J. Sidnell and T. Stivers, 229–256. Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Koole, T. 2010. “Displays of Epistemic Access: Student Responses to Teacher Explanations.” Research on Language & Social Interaction 43 (2): 183–209.

- Kupetz, M. 2011. “Multimodal Resources in Students’ Explanations in CLIL Interaction.” Novitas-ROYAL 5 (1): 121–142. Special Issue: Conversation Analysis in Applied Linguistics.

- Lee, Y.-A. 2006. “Respecifying Display Questions: Interactional Resources for Language Teaching.” TESOL Quarterly 40 (4): 691–713. doi:10.2307/40264304.

- Lee, Y.-A. 2007. “Third Turn Position in Teacher Talk: Contingency and the Work of Teaching.” Journal of Pragmatics 39 (6): 1204–1230. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2006.11.003.

- Liebscher, G., and J. Dailey-O’Cain. 2003. “Conversational Repair as a Role-Defining Mechanism in Classroom Interaction.” The Modern Language Journal 87 (3): 375–390. doi:10.1111/1540-4781.00196.

- Lindström, J., Y. Maschler, and S. Pekarek Doehler. 2016. “A Cross-Linguistic Perspective on Grammar and Negative Epistemics in Talk-In-Interaction.” Journal of Pragmatics 106: 72–79. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2016.09.003.

- McHoul, A. W. 1990. “The Organization of Repair in Classroom Talk.” Language in Society 19 (3): 349–378. doi:10.1017/S004740450001455X.

- Mondada, L. 2011. “Understanding as an Embodied, Situated and Sequential Achievement in Interaction.” Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2): 542–552. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2010.08.019.

- Mondada, L. 2013. “The Conversation Analytic Approach to Data Collection.” In The Handbook of Conversation Analysis, edited by J. Sidnell and T. Stivers, 32–56. Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Mondada, L. 2015. “Multimodal Completions.” In Temporality in Interaction, edited by A. Deppermann and S. Günthner, 267–308. Studies in Language and Social Interaction 27. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Mortensen, K. 2012. “Visual Initiations of Repair – Some Preliminary Observations.” In Proceedings of the Symposium “Challenges and New Directions in the Micro-Analysis of Social Interaction,” edited by K. Lkeda and A. Brandt, 45–50. Osaka: Kansai University.

- Nikula, T., C. Dalton-Puffer, and A. L. García. 2013. “CLIL Classroom Discourse: Research from Europe.” Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education 1 (1): 70–100. doi:10.1075/jicb.

- Raymond, G. 2004. “Prompting Action: The Stand-Alone “So” in Ordinary Conversation.” Research on Language & Social Interaction 37 (2): 185–218. doi:10.1207/s15327973rlsi3702_4.

- Sacks, H. 1984. “Notes on Methodology.” In Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis, edited by J. M. Atkinson and J. Heritage, 21–27. Studies in Emotion and Social Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schegloff, E. A. 1992. “Repair after Next Turn: The Last Structurally Provided Defense of Intersubjectivity in Conversation.” American Journal of Sociology 97 (5): 1295–1345. doi:10.1086/229903.

- Schegloff, E. A., G. Jefferson, and H. Sacks. 1977. “The Preference for Self-Correction in the Organization of Repair in Conversation.” Language 53 (2): 361–382. doi:10.1353/lan.1977.0041.

- Schegloff, E. A., and H. Sacks. 1973. “Opening up Closings.” Semiotica 8 (4): 289–327. doi:10.1515/semi.1973.8.4.289.

- Schwab, G. 2011. “From Dialogue to Multilogue: A Different View on Participation in the English Foreign‐Language Classroom.” Classroom Discourse 2 (1): 3–19. doi:10.1080/19463014.2011.562654.

- Seedhouse, P. 2004. The Interactional Architecture of the Language Classroom: A Conversation Analysis Perspective. Language Learning Monograph Series. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Selting, M., P. Auer, B. Barden, J. Bergmann, E. Couper-Kuhlen, S. Günthner, C. Meier, U. Quasthoff, P. Schlobinski, and S. Uhmann. 1998. “Gesprächsanalytisches Transkriptionssystem (GAT).” Linguistische Berichte 173: 91–122.

- Seo, M.-S., and I. Koshik. 2010. “A Conversation Analytic Study of Gestures that Engender Repair in ESL Conversational Tutoring.” Journal of Pragmatics 42 (8): 2219–2239. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2010.01.021.

- Sert, O. 2013. ““Epistemic Status Check” as an Interactional Phenomenon in Instructed Learning Settings.” Journal of Pragmatics 45 (1): 13–28. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2012.10.005.

- Sert, O. 2015. Social Interaction and L2 Classroom Discourse. Studies in Social Interaction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Sidnell, J. 2013. “Basic Conversation Analytic Methods.” In The Handbook of Conversation Analysis, edited by J. Sidnell and T. Stivers, 77–99. Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Sidnell, J., and T. Stivers, eds. 2013. The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Sinclair, J. M., and M. Coulthard. 1975. Towards an Analysis of Discourse: The English Used by Teachers and Pupils. London: Oxford University Press.

- van Lier, L. 1988. The Classroom and the Language Learner: Ethnography and Second-Language Classroom Research. Applied Linguistics and Language Study. London: Longman.

- Waring, H. Z. 2012. ““Any Questions?”: Investigating the Nature of Understanding-Checks in the Language Classroom.” TESOL Quarterly 46 (4): 722–752.

- Wood, D., J. S. Bruner, and G. Ross. 1976. “The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 17 (2): 89–100. doi:10.1111/jcpp.1976.17.issue-2.

- Zemel, A., and T. Koschmann. 2011. “Pursuing a Question: Reinitiating IRE Sequences as a Method of Instruction.” Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2): 475–488. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2010.08.022.