ABSTRACT

Based on interaction recorded in EFL classrooms, this study uses Conversation Analysis to document the post-first deployment of an absurd candidate formulation (ACF) to pursue recipient response at points of interactional delay. ACFs are a form of correction-invitation device in which the question initiator proffers a candidate response that is hearably inappropriate/inaccurate and therefore designed to be rejected by its recipient and replaced with a more plausible response. The design of the ACF turn is extreme, hyperbolic, absurd or otherwise implausible in nature, and the participants treat it as such via laughter and next-turn negation. ACFs thus help recipients arrive at an acceptable answer by eliminating obviously inappropriate alternatives and indexing a particular class of response. When used in conjunction with more plausible alternatives, ACFs can guide the recipient to select one of those candidates. Even so, recipients can resist the question by providing only minimal responses. Our data are taken from video-recordings of naturally occurring classroom interaction between L1-speaking EFL teachers and L2 learners of English.

1. Introduction

If a second-pair part (SPP) response is missing or delayed, the first-pair-part (FPP) initiator of the sequence can deploy a range of interactional practices to pursue it (Pomerantz Citation1984a; Schegloff Citation2007). When a teacher asks a question, for example, a response from the student they are addressing becomes conditionally relevant, and if missing, both the teacher and the student(s) orient to the delay by pursuing or mobilising a response (Antaki Citation2002; Bolden, Mandelbaum, and Wilkinson Citation2012; Jefferson Citation1981; Stivers and Rossano Citation2010). Some of the interactional practices teachers use to pursue students’ responses include modifying their language to match the students’ level (Hosoda Citation2014), producing polar yes-no questions and candidate responses (Margutti Citation2006), using designedly incomplete utterances (Koshik Citation2002), recalibrating the specificity of the question (Duran and Jacknick Citation2020) and initiating an epistemic status check like ‘no idea?’ or ‘you don’t know?’ (Sert Citation2013). On other occasions, the selected student might respond in a way that the question initiator treats as inapposite, leading to a variety of post-expansive re-initiations (Gardner Citation2004; Kasper and Kim Citation2007; Okada and Greer Citation2013) or reformulated questions (Svennevig Citation2012). Ultimately, the aim of such follow-up talk is to advance the conversation at a point where progressivity has been compromised and to realign it on a trajectory that meets the teacher’s pedagogical goals.

Our study contributes to this line of research by analysing how teachers use what we term absurd candidate formulations (ACFs) to pursue a missing or delayed response from a selected student. An initial example of this practice is shown below in Fragment 1.

Fragment 1. Adapted from Excerpt 2 below.

The teacher initiates a sequence by asking Aki to comment on a video she recently watched (line 11). After a brief delay, Aki offers an initial assessment (‘interesting’, line 13), but then extends the turn with ‘and’ before meeting with some sort of forward-oriented trouble that turns into an extended word search and therefore delays the progressivity of Aki’s response. Eventually in line 21, the teacher restarts Aki’s delayed turn by repeating the turn-initial element ‘it’s interesting’, then offering a short list of candidate responses that fit with the grammatical class Aki’s unfinished turn in line 13 had been projecting, ‘you laughed, you cried, you jumped out the window’ (lines 21–23). The first two of these candidates seem like fairly plausible responses to watching a video, but the third seems unlikely. In this context then, ‘you jumped out the window’ constitutes an absurd candidate formulation that works to restart the conversation by inviting Aki to come up with something less farfetched.

ACFs are therefore expressions that are designed to be hearably incorrect through the absurd nature of their formulation. They are often produced in conjunction with laughter that can highlight the non-serious nature of the expression. The absurdity/implausibility of an ACF is primarily isolated to a given sequential context but also constructed through the use of extreme or hyperbolic (Norrick Citation2004) turn design. However, ACFs stand as a distinct phenomenon from Extreme Case Formulations (ECFs) (Pomerantz Citation1984b) in that ECFs consist of terms of semantic extremity such as all, none, and absolutely. The implausibility of ACFs, on the other hand, is mainly (and often exclusively) brought about through the locally accomplished interactional context and need not involve extreme case formulations. The ACFs we will examine in this study are all deployed in the interactional business of pursuing a missing, delayed or fuller response and are therefore one of many question-asking strategies available to interactants to shape and facilitate recipient turn construction.

Following an overview of related literature on Candidate Answers and Correction-Invitation Devices, this paper analyses several excerpts of classroom interaction, each involving the incorporation of absurd candidate formulations for either (1) assisting in forward-oriented repair or (2) pursuing a response.

2. Candidate answers and correction-invitation devices

When a speaker asks a question, they have resources at their disposal to constrain and shape the type of responses they will receive. WH-questions, for example, allow for a wider range of responses than polar questions, which instead typically receive type-conforming yes or no answers. Speakers may also employ alternative questions, in which they list options for the recipient to choose from (Koshik Citation2005). While all of these question formulations will be explored in our analysis to varying degrees, of central importance is the speaker practice of designing questions to display assumptions concerning their recipients’ answer.

In the CA literature, research into this kind of assumption-displaying turn-constructional unit (TCU) has been developed under the term Candidate Answer (Pomerantz Citation1988). By proffering a Candidate Answer, speakers display an expectation about the kind of response they will receive, and in doing so constrain the next turn to either a confirmation or rejection of their assumption. The design of the candidate provides the recipient with a model of the type of answer that would satisfy the speaker’s purpose-for-asking. This is also shown to be a prevalent practice in second language interaction, where expert speakers can use candidate answers to pre-emptively avoid understanding issues or pursue missing responses when interacting with novice speakers (Svennevig Citation2012). Proffering a candidate is, therefore, a powerful resource which allows speakers to narrow a conditionally relevant response from their recipient(s).

In his lectures, Sacks (Citation1992) explores a similar conversational phenomenon that he refers to as a correction-invitation device: a speaker presents a recipient with an assumption in order to occasion a response that elicits both an on-the-record (dis)confirmation and a correction that contains the information the speaker is seeking. Correction-invitation devices also illustrate to the recipient the kind of response being sought. For example, if the device takes the form of an account, the correction it invites is also likely to be an account.

These features are apparent in the fragment below, in which a police officer (A) is talking to a woman (B) about a gun.

Fragment 2. (Sacks Citation1992, 21).

In line 1, A issues two consecutive WH-questions. B’s response in line 2 addresses the first question, albeit in a somewhat equivocal manner, but leaves the second question unanswered. Rather than repeating his just-prior question (‘whose is it’), A instead proffers one possibility (i.e., a candidate answer) in line 3 that models the class of response he is seeking (the class member ‘yours’). Although it takes the grammatical form of a polar question, the recipient (B) evidently treats a simple yes or no as insatisfactory and instead gives a correction by offering a different member of the same class (‘Dave’s’), thus providing the information A sought.

We can, therefore, consider both Candidate Answers and correction-invitation devices to be addressing different aspects of the same phenomenon (assumption formulations). To Pomerantz, Candidate Answers are a way for speakers to display familiarity or knowledge of a situation while at the same time seeking further information. This means that candidates are usually what speakers project to be correct assumptions. As Pomerantz writes, ‘(i)n putting forth a Candidate Answer, a speaker recognizably offers the Candidate Answer as a likely possibility’ Pomerantz (Citation1988, 369). Sacks’ focus, meanwhile, is on how incorrect assumptions are used as a means of eliciting correct information: he highlights the fact that after one possibility has been negated by a recipient, the provision of a more suitable replacement becomes a relevant and regularly occurring next action. Pomerantz’ Candidate Answers can thus be characterised as relatively high plausibility assumptions while Sacks’ Correction-Invitation Devices appear plausibility-neutral or low plausibility. In contrast, as we will show through our analysis, ACFs present assumptions that are so absurd, factually problematic or exaggerated that they cannot reasonably be accepted by the recipient. Since ACFs are designed to be rejected, they also make an alternative candidate sequentially relevant. ACFs are therefore particularly relevant to contexts where a speaker is encouraging the recipient to arrive at an answer while maximising the probability of that answer being an original or independent contribution. As Svennevig (Citation2012) notes, Candidate Answers from expert speakers can restrict a novice recipient’s ability to respond freely and thus be considered interactionally dominating moves. ACFs retain many of the positive features of standard Candidate Answers while bypassing these problems. Additionally, in the classroom ACFs act as a resource for managing institutional rights and obligations between teachers and students as they allow teachers to direct the student towards providing a response without giving them an answer outright; the teacher maintains their role as question asker (and eventually evaluator) and the student can fulfil their obligation to answer as accurately as possible.

3. Data and method

Our data originate from EFL classrooms in a Japanese university in which the instruction focused on English speaking and presentation skills for first-year university students. The teachers were L1 speakers of English. The dataset was collected between April and August 2017 and consists of 20 hours of video-recordings from four classes. From this, we compiled a collection of 14 cases of the target phenomenon, of which four are analysed in detail here. Our analysis follows the Conversation Analytic (CA) method of focusing on the social and sequential details of both spoken and embodied elements of the participants’ interaction (Sidnell and Stivers Citation2012). The transcription is based on Jefferson’s conventions (Citation2004) and notes on the gestures are shown in grey relative to the talk via a separate tier, following Greer (Citation2019) (see Appendix A1).

4. Findings

As mentioned above, our analysis centres around an interactional practice deployed by teachers to help students arrive at locally adequate answers after a student has displayed difficulty doing so. This difficulty commonly manifests as a long gap after the teacher has issued a first-pair part but can also result from a response that is treated as inadequate or insufficient by the teacher. The latter case is apparent in below (reanalysed from Koole Citation2010), in which a student in a maths class gives a timely answer (line 13) that the teacher nonetheless orients to as problematic.

Excerpt 1. Tatjana RB-061299 (Koole Citation2010).

The teacher’s TCU in line 14 (‘two what?’) is brief but interactionally complex in that the addition of the prospective indexical (Goodwin Citation1996) ‘what’ serves to highlight an accountably missing component of her answer while still treating the initial turn component ‘two’, as acceptable. The teacher quickly follows this up with a candidate answer, ‘two cows?’ that replaces the prospective indexical with something hearably disjunctive to this local context and thus seemingly designs it to be rejected. Tatjana does indeed reject ‘cows’ implicitly in the next turn by not adopting that part of the candidate and instead reformulating her answer to ‘two centimetres’, displaying an understanding that the missing element of her original answer was a unit of measure, and indeed eventually this turns out to be correct (not shown in the transcript). The teacher’s turn in line 14 was therefore successful in guiding the student towards an appropriate response and restoring sequential progressivity.

The current paper focuses on turns like line 14, where a teacher gives a candidate answer that is designed to be rejected rather than seriously considered as a genuine possibility. We call this interactional practice proffering an absurd candidate formulation (ACF). While in progressivity was temporarily suspended to deal with Tatjana’s insufficient answer, the cases from our data will document spates of talk where a teacher issues an FPP but the students’ sequentially due SPP is delayed. Such is the case in the following section where a student’s response is put on hold to initiate forward-oriented repair.

4.1 Using ACFs within forward-oriented repair

In this section, we expand on Fragment 1 to document how the teacher employs an ACF to mobilise a response from a student engaged in forward-oriented repair (Greer Citation2013, Schegloff Citation1979). Just prior to this excerpt, the teacher had been walking around the room while monitoring the students, who were standing in small groups discussing some TED talks they viewed for homework.

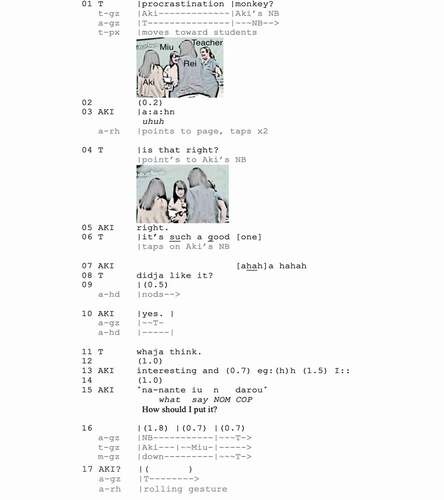

Excerpt 2. Jumped out the window.

On overhearing the name of a TED talk she apparently recognises, the teacher approaches one group of three students and issues an opinion query (Maynard Citation1989) to Aki in line 11. However, Aki seems to experience difficulty formulating a timely response. After a 1-sec gap in line 12, she begins an assessment saying its ‘interesting and’, but displays difficulty completing her turn-in-progress. This is evidenced by a 0.7-sec silence, some hesitation tokens, another 1.5-sec silence and the word ‘I’ (line 13), which is intonationally stretched at a grammatically incomplete juncture, indicating forward-oriented repair. After an additional 1.0-sec silence in line 14, Aki expresses formulation trouble by saying ‘how should I put it’ in Japanese before another lengthy pause totalling 3.2 seconds (line 16). Aki spends 2.5 sec of this silence looking at her notebook then gazes back to the teacher for 0.7 seconds before producing an inaudible utterance in line 17 along with some rolling hand gestures, bodily indicating that she is still in the process of formulating a response. Line 18 is yet another use of L1 to produce a TCU that overtly expresses formulation trouble, this time an assessment that treats providing a response as ‘difficult’. This laughed-through turn is followed by further public displays of formulation trouble: some small grunts, a tilt of the head and grooming of the hair (line 20).

With Aki’s SPP still unfinished, the teacher joins in the word search by proffering a list of candidate reactions to the TED talk that concludes with an ACF. In line 21, the first part of the TCU (‘it’s interesting, you …’) is a co-operative transformation (Goodwin Citation2018) of Aki’s incomplete SPP in line 13 (‘interesting and I …’), which is further modified with the addition of a three-part list (Jefferson Citation1990) of candidate completions: ‘you laughed, you cried, you jumped out the window?’.Footnote1 First, note that the ACF is accompanied by laughter that works to further index its non-serious design. As we will show in our later analysis, laughter is a regularly occurring feature of ACF proffering sequences. It is also relevant that the teacher names the first two candidates of her list smoothly but displays hesitation (stretching her utterance and pausing for 0.2 sec) before giving the third. According to Jefferson (Citation1990), when a speaker has given two items they may engage in search for a third. If a third is not found or would not ‘adequately exhaust the possible array of nameables’ (68) a generalised list completer (e.g., ‘that sort of thing’) is given. Here the teacher’s utterance ‘you jumped out the window’ is not a generalised list completer, but is doing similar interactional work in that it suggests that there are many other possibilities that will not be named. This is accomplished by the juxtaposition of her candidates creating a continuum from mundane reactions (laughing, crying) to extreme or hyperbolic ones (jumping out a window).

While in many cases implausible candidates are offered by teachers as a means of eliminating options and guiding students towards acceptable answers (the focus of the next section), in this case the teacher seems to be widening the range of responses that would be treated as acceptable answers to her original question (line 11, ‘what did you think?’). In other words, the teacher suggests that at this point she would accept any kind of description of Aki’s reaction, be it normatively plausible or not.

Note also the prosody of the teacher’s turn in line 26 ‘what happened’ makes it hearable as an upshot of what her three-part list represented. We might then characterise the list as a failed attempt at eliciting a telling from Aki regarding her emotional reaction to the TED talk, as well as an invitation to select or correct from that list.

4.2 Pursuing a missing or delayed response with ACFs

Whereas the previous section focused on a student who produced a partial response but had difficulty formulating a complete TCU, this section will document how teachers use ACFs to pursue a response when it is missing or delayed within IRF sequences. We will focus on an impromptu activity in which the teacher is familiarising the students with the value of US dollars. The teacher poses a hypothetical scenario in which he states a dollar amount and tasks a selected student with naming an item that approximately matches that value. The transcription is divided into two excerpts, each one constituting one round or iteration of the IRF activity. We argue that each iteration gets progressively smoother as the students are able to produce responses better fitted to the teacher’s expectations based on prior examples involving the use of ACFs as well as standard Candidate Answers. As the first iteration in the series, contains the most substantial delays and our analysis documents how the teacher goes about dealing with them using an ACF.

Excerpt 3. Buy a house.

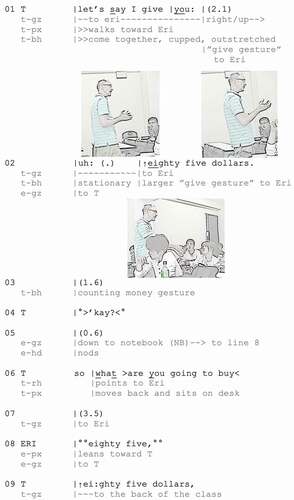

In lines 1 and 2, the teacher presents Eri with a proposal by saying ‘let’s say I give you 85 dollars, while moving his cupped hands towards her. The turn-initial ‘let’s say’ works to invite the hearing of the TCU as an imagined premise that projects a later question that will use the same hypothetical frame. His gesture serves as both an iconic depiction of giving and a re-selection of Eri, who aligns as a recipient by gazing directly towards the teacher. In line 3, the teacher then uses another gesture to enact the counting of money. Unlike the previous gesture that seemed to more generically represent giving (the holding up and lowering of a cupped hand), this one is instead a pantomime of handing out bills one by one. This more detailed enactment works to further facilitate both Eri and the other students’ imagining of his described scenario. The teacher follows this with a brief FPP seeking acceptance of his proposal with ‘okay?’ (line 4) to which Eri responds minimally with a slight nod. With his premise accepted, the teacher initiates a WH-question that hearably connects to and completes his earlier proposal by asking Eri ‘what are you going to buy?’ He then moves back and sits on a desk to wait for her response. However, this is followed by a 3.5-sec gap in line 7 during which Eri is seemingly engaged in searching her notes as a means of delaying her response (see Reinelt Citation1987).

Although her response is still conditionally due, in line 8 Eri instead looks up to the teacher, leans towards him and initiates repair by repeating ‘eighty-five’ in a soft voice. The teacher’s confirming response (line 9) is delivered in a louder voice and with gaze shifts around the classroom and therefore serves to include other students in the activity. From lines 11 to 13 the teacher provides a third-person reformulation of his earlier hypothetical proposal, further broadening the participation constellation, but also providing Eri with a subsequent version of the task to facilitate her still accountably missing response. This is followed by another long silence of 6.4-sec (line 14) in which Eri stares down at her notebook, briefly gazes back to the teacher, then looks back to the notebook again. Since she has yet to provide a spoken response, the teacher re-initiates the question by saying ‘what can you buy for eighty-five dollars?’ (line 15). By doing this, the teacher may be treating Eri’s delayed response as a language problem (Hosoda Citation2014), which he deals with by simplifying the grammatical formulation of his utterance (from ‘what are you going to buy’ to ‘what can you buy?’) making it easier for her to come up with an answer.Footnote2 However, this too is followed by a very long silence in line 16 in which Eri again focuses her attention down at her notebook, occasionally even writing in it. By not speaking further at this point, the teacher treats Eri as actively working towards a response for a full 18.3 sec.

Just as the teacher appears about to give up by closing the sequence with ‘okay’ and pointing to another student (line 17), Eri finally produces the beginning of her conditionally relevant response (in overlap) saying ‘I’ in a very quiet voice. The teacher immediately abandons his TCU mid-word (and therefore abruptly aborts his selection of the other student) and instead reorients his gaze and body to Eri before giving her a literal go-ahead (Schegloff Citation2007) to continue speaking. Eri produces the first part of the response ‘I buy’ in line 20 but does not complete it. In the next turn, she looks down at her notebook, tilts her head and smiles, indicating her difficulty in arriving at a response.

After a further delay of 7.8 seconds and with Eri’s turn not yet complete, the teacher produces a candidate answer, ‘can you buy a house?’ (line 22), reformulating it from a WH-question to a positive polar question that makes a reverse-polarity negative assertion (Koshik Citation2002). This constrains Eri’s response to a type-conforming yes or no and makes it easier for her to reply because it is weighted towards the no-response, based on cultural knowledge. The teacher’s proffered candidate is an ACF in this sequential context because a house not only exceeds the hypothetical amount of currency he has given her but does so in a blatant way. The teacher follows this ACF with laughter to further highlight its implausibility which occasions reciprocated laughter (Jefferson Citation1979) from Eri and some of the other students as they align with his treatment of his own candidate as not just implausible but laughably so. In line 26, the teacher gives another candidate (‘no?’), which pursues Eri’s missing second-pair part due after line 22. The delivery of this brief, smiled-through turn features two quick pitch rises that display a stance towards his ‘no’ answer as one that should be obvious, and therefore treats his own question as silly (Stokoe and Edwards Citation2008). Eri accepts his candidate repeating ‘no’ in the next turn and the teacher moves to close the sequence in third position saying ‘no house? No’. In lines 29–30 Eri again delays her response to the teacher, firstly by looking down at her notebook and then by whispering to the student next to her. In line 31, the teacher proffers another candidate, this time choosing an item that falls within the 85 dollar limitation and is therefore weighted towards a yes response, which is indeed the answer that Eri gives in line 33.

The teacher’s ACF in line 22 had multiple pedagogical functions. For one, it helped to provide a much-needed injection of levity after long awkward gaps. It also provided a question that the selected student could presumably answer easily and quickly before re-initiating the original question that was left unanswered. The practice also allows for the joint establishment of what is not an acceptable answer to the problematic question and thus works to narrow the scope of what is acceptable. The design of both the ACF and the regular candidate (line 31) hints at the type of response the teacher is seeking in that they both contain everyday items that have commonly known values, making it inferable that he is not asking for responses that contain multiple items or unusual items with ambiguous values. As a whole, this drawn out IRF sequence functions as an exemplar for subsequent iterations of the activity to progress more smoothly as shown in , which continues directly after this.

In the teacher moves to a new student extending the activity to its second round.

Excerpt 4. Buy a car.

The teacher initiates a hearably iterative version of the sequence in , first by linking it with ‘okay’ and ‘so’, which work to close the prior version and transition to the next. His turn in lines 35–36 also serves to multimodally select a new student, Dai, via talk (interrogative syntax and proterm usage), prosody (emphasis on you via initial stress and vowel-lengthening) and embodiment (pointing to Dai) (see Amar Citation2020 on multimodal next-speaker selection). His intonation on the word ‘you’ sets up an implied contrast with Eri, who he selected in the first round of this task. In line 36, the teacher concludes his premise-setting turn by stating the amount of imaginary money he has allotted to Dai ($700) and issuing a sequence-initiating WH-interrogative that prompts Dai to respond by naming something that is commonly bought at that price point (line 38). The pronoun ‘you’ is again intonationally emphasised in order to position this activity as something another student has already done. The teacher’s formulation in this round is also somewhat streamlined compared to the first iteration, suggesting he is designing this turn for a group of recipients who are now familiar with the nature of the task. We can notice, for example, that the hypothetical marker ‘let’s say’ does not appear (as it did in line 1) and nor does the inserted confirmation check after the number of dollars is specified (cf. line 4). Additionally, rather than providing multiple embodied enactments of giving money, the teacher makes a single simple movement of the left hand towards Dai. These subtle changes in question design demonstrate that the teacher now sees the students as more familiar with the task than they were in its first iteration ().

In lines 39 to 42, Dai displays various embodied and verbal indications of difficulty, including extended silence, averted gaze, hesitation markers (‘ehh’, ‘mmm’), head tilting and chin rubbing. Together these all seem to send a message that Dai has understood the question but is still considering his answer. In the first iteration of this activity, the teacher’s initial attempts at addressing the lack of a conditionally due SPP involved recasting/clarifying the task for the students ( lines 9, 11, 13, 15). We can thus say that in round 1 the teacher initially attributed the delay to some problem in his own formulation of the question. Conversely, in round 2, the teacher chooses to employ an ACF immediately (in line 43), asking Dai ‘can you buy a car?’ As in , the proffered candidate is an ACF because it clearly exceeds the amount specified in the teacher’s premise and is thus likely designed for rejection. The teacher has again not only shifted from a WH-question (with many possible answers) to a polar question (two possible answers) but also to one that is highly weighted towards a ‘no’ response (i.e., effectively one possible answer). In the next turn (line 44), Dai indeed orients to the ACF as something both laughable and rejectable, bolstering it with embodied rejection by waving his hand in front of his face which the teacher affirms by repeating ‘no’ while nodding, thus closing the sequence. After this inserted sequence in which they jointly establish what cannot be bought with 700 USD, the teacher re-initiates his first question asking what can be bought (line 49).

After waiting for 1.6 sec, Dai provides a response (line 51) by proffering an item (‘personal computer’) that is both cheaper than the ACF ‘car’ and potentially under the hypothetically posed limit of 700 USD. Dai, therefore, designs his response in accordance with the rejected ACF and this is treated as plausible and acceptable in the third position by the teacher via receipt through repetition, positive assessment and ‘okay’ (line 55), which all serve to close down the sequence (Wong and Waring Citation2009).

The teacher’s use of an ACF, therefore, works as one element of a response-pursuing sequence. The teacher narrows the range of possible answers by proposing a candidate that is hearable to the student as patently implausible. This allows the student to (1) launch an immediate response (rejecting the candidate) and (2) get access to several clues about the sort of response the teacher is looking for: its grammatical class (a noun), nature (a thing that can be bought) and value (less than that of a car). All this helps the student come up with an item that is less expensive than the ACF and thus constitutes a plausible response. In short, the teacher’s deployment of an ACF has rebooted the stalled progressivity of the sequence.

Together these two excerpts form part of an extended multi-part activity in which the teacher initiates a series of questions designed to help the students better understand the value of US currency. The main focus of this section of the analysis has been on how the teacher uses ACFs to progress the talk at points where a student response is hearably delayed. The recipient treats the ACF as implausible with next-turn laughter and follows it with a rejection of the candidate, meaning the ACF also works to pursue a response by prompting the student to come up with something less implausible. By suggesting something beyond the limit he has set, the teacher guides the students to think of an alternative under the limit. Although the candidate is implausible and rightly rejected, it does offer the student information about the class of response that the teacher is expecting, and therefore serves to narrow the kind of answer that is appropriate. In addition, as with correction-invitation devices, when one proposed assumption is negated, the proposal of a replacement becomes a relevant next action for the recipient. ACFs thus form part of the interactional arsenal available to teachers for pursuing a second-position response when one is sequentially due.

4.3 Multiple ACFs and recipient resistance during the pursuit of response

In the previous section, we showed how ACFs were used across iterations of a teacher-directed whole-class discussion to pursue missing responses. This section will further explore the subject of pursuing a due response, but is distinct in several ways. First, whereas and were each relatively short rounds of a teacher-directed activity, the following and are part of a single extended pursuit sequence that contains multiple ACFs. Second, the focal student, Koh, displays resistance to the teacher throughout the talk which leads to a somewhat tense negotiation about who is responsible for the stalled sequential progressivity.

As in , the students in are standing in small groups discussing a TED talk that they had watched as homework . Koh appears to be in the midst of delivering a telling when the teacher walks up to his group, stands about 20 cm from him and maintains gaze on his face. The participation framework of the interaction has thus shifted from a triadic student discussion (with the teacher in the periphery as an overhearer) to a four-participant constellation. It is just after the teacher’s somewhat abrupt entry into the group that Koh begins to show signs of formulation trouble.

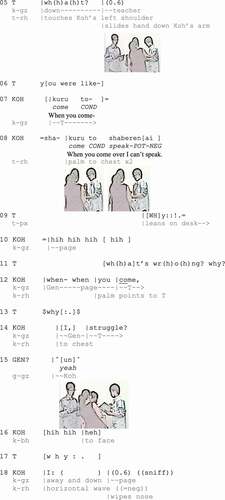

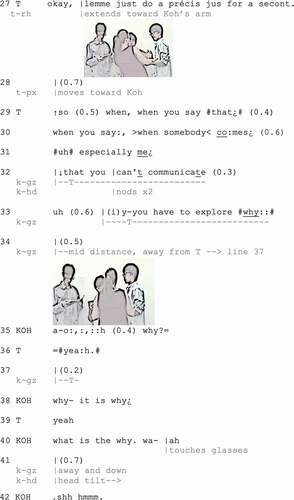

Excerpt 5. Do I smell.

In line 1, Koh gets partway through his TCU before pausing for 1.4-sec and producing a stretched ‘ah’ which is hearable as a display of forward-oriented repair. This is followed by another 1.3-sec pause, an intonationally stretched ‘so’, and a quiet hesitation token in Japanese as he touches his glasses, which taken together delay the turn. Line 3 marks the abandonment of Koh’s turn-in-progress, and he instead starts a new turn in Japanese (kyuuni shaberenakunatta zo/”Suddenly I can’t talk”), a claim of his own sudden inability to speak, followed in line 4 with laughter tokens. His turn only describes his current condition without attributing it to anything – an effect without a stated cause. Interactionally we could think of this as a noticing (of his internal state and its public outcome), which occasions or invites an account (Greer Citation2019). The teacher reciprocates Koh’s laughter in next turn as she other-initiates repair (‘what?’) while touching his left shoulder. She begins to start another turn when Koh gazes towards her for the first time since she entered the group, specifying a reason for his inability to speak (kuru to shaberenai/‘When you come over here I can’t speak’). Unlike his earlier turn in line 3, his formulation in lines 7–8 works as an account for his speaking trouble: the teacher’s presence. This account, while brief, shifts the responsibility for the abandonment of his telling (and consequently the assigned task) to the conduct of the teacher rather than one of his own linguistic (in)ability and overtly expresses resistance to her reconfiguration of the participation constellation.

Rather than accepting his account, the teacher questions it directly, asking ‘why!’ in partial overlap with the end of his turn, effectively soliciting an account for his account. In other words, the teacher’s ‘why’ targets not only the reason he cannot speak but also the reason her presence is to blame. Rather than responding with an SPP to the teacher’s question, Koh simply laughs and averts his gaze to his notebook but says nothing more, leading the teacher to re-initiate her account solicitation in line 11 asking ‘what’s wrong? Why?’. Her turn is produced with several inserted laughter tokens indicating that, on the one hand, she is aligning with Koh in treating the matter as laughable at this point while on the other hand holding him accountable to justify his claim that her entering the conversation renders him unable to speak. In line 12, Koh orients to the teacher’s re-initiated question as an issue related to medium rather than content, in that he begins to repeat his originally stated reason ‘when you come’ but does so in English this time. He is hearably on the way to something when the teacher interjects mid-TCU, again re-issuing her call for an account by saying ‘why’ and thus showing her orientation to the content of his assertion as problematic. Undeterred, Koh finishes his turn saying ‘I struggle’ in overlap with the end of the teacher’s utterance. This is once more followed by some laughter tokens, which work to make this potentially combative exchange seem less so. Still not having received a proper account, the teacher re-initiates her account-eliciting ‘why?’ (line 17) in overlap with Koh’s laughter. In line 18, Koh begins responding to the teacher’s FPP but does not seem to produce a full TCU before pausing for 0.6 sec and sniffing.

By this point, the teacher has now used ‘why’ to seek the same information a total of four times (lines 9, 11, 13, 17) and has still not received an account from Koh that she treats as acceptable: in other words, her recurrent account initiations are a means of pursuing an apposite response. Rather than just letting it pass or repeating more of the same open-ended account solicitations (‘what’s wrong?, why?’), in line 19 the teacher deploys an ACF in an attempt to realign the talk and restore progressivity. Her formulation ‘is it because – do I smell?’ models the relevant next action for responding to her “why?” (giving an account), while the premise it poses is obviously designed to be rejected for several reasons. First, as a self-deprecation, her turn uses preference organisation to constrain Koh’s likely response to a disagreement (Pomerantz Citation1984a). Next, the scenario that it describes, a person unable to talk because of another’s body odour, is an unlikely reason one might not be able to speak. The teacher further emphasises the ACF’s rejectability in the next turn by giving her own assessment (line 20, ‘I don’t think I smell’) and Koh’s response in line 21 aligns with this by rejecting the ACF with an intonationally stretched ‘no’ and several emphatic waves of his right hand. In setting up a candidate that can be easily rejected by the student, the teacher works to turn the arrival at a response into a joint activity of specification through elimination. By co-establishing what a correct response is not, they are working together towards finding what it is.Footnote3 Additionally, in eliminating a candidate that holds her responsible (‘do I smell?’) the teacher begins to place the talk on a trajectory that disagrees with Koh’s original claim ‘when you come, I can’t speak’.

However, even after rejecting the ACF Koh does not provide a replacement account, leaving the original FPP issued by the teacher (‘why?’, line 17) still unanswered. Thus far then, the teacher has used an ACF as one element in her pursuit of an account, and she continues that pursuit in , eventually launching a second ACF involving the candidate answer ‘Did you have an English teacher punch you or something?’

Excerpt 6. Trauma.

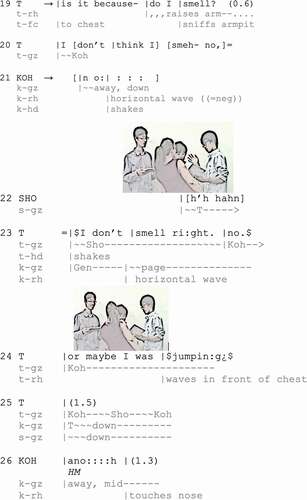

At the end of , Koh was working to ignore the teacher’s line of questioning, shifting his gaze down at his notebook then into the mid-distance (lines 25 and 26), seemingly searching for a way to restart the conversation he was having before she came along. At the start of (line 27), the teacher orients to this resistance, touching Koh on the arm and repositioning her upper body to within closer proximity to his line of sight as she launches a second round of response pursuit. At this point, she effectively puts the pedagogical activity (the student discussion) on hold by initiating a pre-sequential request that projects an activity she identifies as a ‘précis’. In momentarily redefining the activity, she also repositions herself as central to that activity.

However, rather than just a summary, the teacher’s contribution in lines 29 to 33 seems to primarily consist of an explanation that reprises her earlier line of questioning. She begins her turn in line 29 with ‘so’, a discourse marker that ties it to the previous talk and she marks the ‘précis’ with a variety of rewordings and self-repairs that sequentially unpack the explanation as she goes: she reformulates Koh’s ‘shaberenai’ to ‘can’t communicate’ (line 32) and recalibrates the pro-term ‘somebody’ in line 30 to ‘especially me’ (line 31). Crucially she follows her conditional clause ‘when you say that …’ with ‘you have to explore why’ (line 33), and this effectively restarts the pursuit of response, not only with the turn-final account initiator (‘why’) but also by designing it as an implied directive (‘you have to’), which invokes a moral stance, increasing the level of obligation and responsibility implicit in pursuing a response that satisfies her, as well as displaying an explicit stance towards Koh’s earlier claim (‘when you come I can’t speak’, line 13) as something that he must account for.

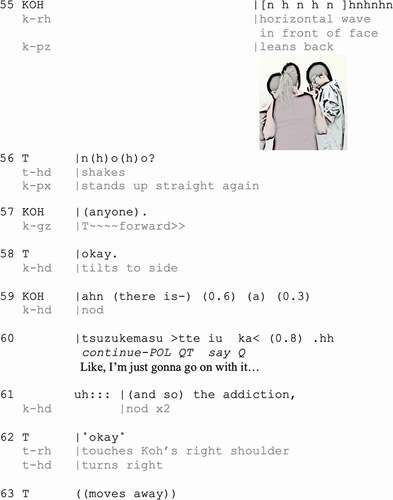

Koh appears to orient to this obligation in the following turns (lines 34–44), at least to the extent that he abandons his attempt to return to the assigned task and instead addresses what he has understood so far: although he still cannot explain the reason behind his nervousness, he is at least aware that the teacher is asking him why. What follows is a broken series of silences (lines 34, 37), non-lexical claims to understanding (line 35), followed immediately by delay-inducing confirmation sequences (line 35–36, 37–38) and more silence during which Koh looks away and tilts his head in a manner that displays his inability to arrive at an answer (line 41). His non-lexical perturbations in line 42 and silence in line 43 further serve to delay his response, and this eventually leads the teacher to offer a second round of possible candidates, two of which we consider ACFs.

Although Koh’s turn in line 44 finally appears to be formulating a response, it displays evidence of further forward-oriented repair (vowel-lengthening, lexical perturbation, mid-turn pauses) and before he brings it to completion, the teacher offers further candidate responses. Designing her turn as a multiple-choice alternative question, her initial candidates are formulated in a three-part list (lines 45–46) and offer hearably rational reasons for not being able to speak (‘nervous, or embarrassed, or ashamed’) and at this point Koh seems to be considering these options, his gaze shifting between the teacher and the mid-distance as he listens. However, before he can respond, the teacher self-selects to shift tack slightly. In line 47 she begins with ‘or have I’ but then abandons that turn before bringing it to completion, replacing it instead with the possible ACF ‘is it a reaction from some trauma?’ In addition to deleting the personal pronoun (that held the potential to implicate herself as the source of his nervousness), the teacher’s ACF is post-positioned after a list of three commonsense reasons that are scaled responses which escalate in extremity (Bilmes Citation2009). As was the case in earlier excerpts the deployment of an ACF leads the student to provide a minimal negative response in a relatively prompt and emphatic fashion (line 52).

In lines 53 and 54 the teacher goes on to produce a laughed-through specification of the sort of trauma she is suggesting, ‘like did you have an English teacher punch you or something?’, which makes it clear that the candidate is intended to be heard as absurd. Koh does in fact treat it that way in next turn by laughing as he produces an embodied response that rejects the candidate. However, while it is hearably absurd, the membership categorisation work that this ACF accomplishes is also rather telling. Up until this point, the teacher has used fairly neutral pro-terms such as ‘you’, ‘I’ and ‘somebody’, but here she specifies the actor of the trauma as ‘an English teacher’, a category that could be applied to her, and that activates its standard relational pair (Sacks Citation1992), ‘student of English’, which is hearably applicable to Koh. The sort of activities that are bound to the category of ‘English teacher’ would normatively include things like explaining, teaching or reading, but not punching. By linking that activity to the category of English teacher, she is, therefore, setting the candidate up to receive a rejection, and possibly also inviting the student to search for a more commonsense response, or indeed to choose one from the list she has already provided.

However, as it turns out, in this case Koh never does formulate a reason, and the teacher eventually abandons her inquiry and moves on to another group. In line 56 she initiates a confirmation, but Koh’s response is inaudible and his gaze shifts away as he again tilts his head laterally, suggesting incomprehension and/or projecting further delays to the progressivity (Seo and Koshik Citation2010) and he appears to be disaligning or even resisting the teacher’s interactional project. At this point, the teacher seems to give up, producing a sequence-closing ‘okay’ in line 58, and Koh switches to Japanese to initiate a disjunctive return to the topic his group were discussing before the teacher arrived (line 60). After it becomes clear to the teacher that Koh is not going to respond to her questions, she touches him lightly on the arm and produces another quiet ‘okay’ as she walks away.

The analysis of this sequence provides a number of insights into ACFs. Firstly, they are often produced in conjunction with other hearably rational options, and this helps shape their implausibility. At the same time, they serve to invite the recipient’s inspection of the alternative candidates and perhaps incorporate one of them into their response. Secondly, they can be resisted and do not always lead to a successful outcome. In Koh’s case, it seems the teacher’s persistent bids for a deeper account (lines 17, 19, 33, 45–50), only exacerbate the situation; rather than just being due to limits in his interactional competence, it could also be that the nature of the original topic may account for Koh’s reticence to progress the talk in this instance. Stating that he cannot speak when the teacher is listening (lines 7–8, 12, 14) has the potential to be heard as a criticism of her, and to unpack it further may lead to disagreement and even argument. By resisting the teacher’s pursuit of a response, Koh actually works to avoid such an eventuality before it escalates.

5. Discussion and conclusion

To recap briefly on our findings, this study has documented the deployment of a particular form of candidate answer in the pursuit of a sequentially due recipient response. By launching a post-initiation ACF after a period of recipient-attributable silence, teachers are able to help students formulate a response by highlighting an improbable candidate as non-appropriate or setting it up as a correction-invitation device. Proffering an absurd candidate response (by formulating it as implausible, extreme, hyperbolic or the like) guides students to consider a plausible alternative within the same class of answer and thus urges them to provide an apposite response. The initiator of the ACF highlights its absurdity with laughter, smiled-through delivery, intonational emphasis or some form of embodied hint, such as a side glance. The ACF is thus designed to be rejected, and recipients orient to this in next turn via laughter and immediate negation. The interactional practice of initiating an ACF promotes progressivity while orienting to the preference for a response from a selected next-speaker. Our study, therefore, contributes to the CA literature on pursuing a response (Jefferson Citation1981; Pomerantz Citation1988; Stivers and Rossano Citation2010) by documenting this previously undescribed interactional practice.

Revising the question plays a crucial role in arriving at an eventual student response. The act of reformulating a question (e.g., from a WH-question to a Y/N or alternative question) narrows a broad range of answers to a limited number of choices (Duran and Jacknick Citation2020), while a candidate response provides the student with a model answer (Svennevig Citation2012), making it easier for the recipient to respond to. However, in addition to this, an ACF expressly avoids revealing the answer by inviting the recipient to instead inspect the candidate for plausibility and formulate a substitute response of their own. As a non-example, the ACF, therefore, provides the student with insight into the sort of response the teacher is expecting or that they deem (factually or morally) acceptable.

In addition, it is worth noting the considerable extent of delay in the examples we have analysed, sometimes up to 18.5-sec of silence between the initial formulation of the question and the onset of the revised format (, line 16). Such silence is not comfortable. Given the non-serious nature of ACFs, it could be that at least part of their purpose is to relieve some of the tension in the air when a student cannot come up with a timely response. The teacher’s joking stance inherent in many of the ACFs occasionally borders on jocular mockery (Haugh Citation2010), and therefore serves as a bid for affiliation. In proffering an answer that is patently incorrect, the design of the ACF also invites recipients to proffer an answer that, even if it is not correct, is at least not equally absurd. ACF initiators, therefore, send the message that any answer is preferable to silence at a temporal point where the recipient is accountable for that silence.

That said, while the ACFs in our data do eventually lead to some sort of response, many were just one or two words, and none occasioned further detailed interaction. In two of the cases the teacher left the conversation entirely by walking away ( and ), while in others the teacher initiated topic transition by selecting another student (–). This may be a feature of the sort of interaction in our dataset – classroom talk between an L1-speaking teacher and novice L2 users of English. Had the students been better at English they might have gone on to produce a post-expansive account for their response. Faced with the possibility of even further delay, the teacher accepts a minimal response, even when it does not go beyond the original answer the student gave (e.g., ‘interesting’, , lines 13 and 28).

Moreover, at least some of these ACFs were deployed in sequential environments that invoke and embody student resistance. Post-initiation silence may result from a variety of issues – the recipient may not understand the question, or may not have heard it, or may be working on a response. But it could also be that there are participatory or preference issues at play, as seemed to be the case in and , when the teacher approached small groups of students who were actively talking with each other. In such cases, the teacher did not have the right to the floor (as was the case in the whole-class discussion in –), so in order to speak, she had to renegotiate the participant constellation, either through physical proximity () or interruption (). This may lead to a form of deontic incongruence (Stevanovic and Peräkylä Citation2012) in which the students resist the suggested distribution of rights by refusing to respond. Furthermore, the nature of the questions themselves is different here too: in the whole-class discussions they are display questions, but in the small-group talk the teacher is genuinely asking the students about their opinions or feelings, meaning that the students possess the epistemic rights to the answer. In proffering an ACF in those situations, the teacher is therefore only able to formulate the candidate in terms she attributes to the student, not on what she herself knows to be true. It is the student who has the right to replace the ACF with their own answer, and when this does not happen (for whatever reason), the teacher abandons the conversation by walking away.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants at the 2018 CAN-Asia Hattoji retreat, including Eric Hauser, Daisuke Kimura, Yosuke Ogawa and Ian Nakamura, for their early insights on this data. We are also greatly indebted to the editors and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cheikhna Amar

Cheikhna Amar is a PhD candidate and an EFL instructor at Kobe University. He is writing his dissertation using CA methods to analyse teacher-student interaction in EFL classrooms in Japan. The main focus of his research is on teachers’ practices to pursue students’ responses. [email protected]

Zachary Nanbu

Zachary Nanbu is a PhD student and language instructor at Kobe University. He is interested in using Conversation Analysis to explore second-language interaction in both classrooms and in the wild. His research focuses include epistemics and the use of embodied resources such as gesture, gaze and object manipulation. [email protected]

Tim Greer

Tim Greer is a professor at Kobe University. He is interested in micro-interactional aspects of second language use, including bilingual interaction, interactional ecology and identity-in-interaction. A list of his publications can be found on his website at: tim792.wixsite.com/greer

Notes

1. The phrase ‘I laughed, I cried’ is a fairly common expression in American English used as a critique of theatre, cinema, etc. An internet search of the phrase revealed a variety of usages within the three-part list format where the third item in the list was extreme or absurd. Some examples include an article on MIT’s website titled ‘I laughed, I cried, I projectile vomited’, several quotes from film and television, such as ‘I laughed, I cried, I puked in my mouth a little’ and Google auto-completions like ‘I laughed, I cried, I fist pumped the air’.

2. In addition, ‘what are you going to buy’ frames the question as one of Eri’s volition whereas ‘what can you buy?’ asks for one possibility. Since the teacher has not specified the purpose of the purchase, it might be difficult for Eri to come to a decision as to what she is going to buy since she is unsure of the consequences. Simply saying something that can be bought makes it a possibility disconnected from Eri as an individual and is thus less consequential.

3. This may also be related to the phenomenon of negating a semantically contiguous referent documented by Kurhila (Citation2006) in which speakers during word search sequences will negate items semantically related to the word they are searching for.

References

- Amar, C. 2020. “Turn Allocation Practices for Selecting a Speaker and Pursuing a Response in English Classroom Interaction.” Journal of the School of Languages and Communication, Kobe University 16: 80–100.

- Antaki, C. 2002. “Personalised Revision of ‘Failed’ Questions.” Discourse Studies 4 (4): 411–428.

- Bilmes, J. 2009. “Taxonomies are for Talking: Reanalyzing a Sacks Classic.” Journal of Pragmatics 41 (8): 1600–1610. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2008.10.008.

- Bolden, G., J. Mandelbaum, and S. Wilkinson. 2012. “Pursuing a Response by Repairing an Indexical Reference.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 45 (2): 137–155. doi:10.1080/08351813.2012.673380.

- Duran, D., and C. M. Jacknick. 2020. “Teacher Response Pursuit in Whole Class Post Task Discussion.” Linguistics and Education 56: 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2020.100808.

- Gardner, R. 2004. “On Delaying the Answer: Question Sequences Extended after the Question.” In Second Language Conversations, edited by R. Gardner and J. Wagner, 246–266. London: Continuum.

- Goodwin, C. 1996. “Transparent Vision.” In Interaction and Grammar, edited by E. Ochs, E. Schegloff, and S. Thompson, 370–404. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Goodwin, C. 2018. Co-operative Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Greer, T. 2013. “Word Search Sequences in Bilingual Interaction: Codeswitching and Embodied Orientation toward Shifting Participant Constellations.” Journal of Pragmatics 57: 100–117. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2013.08.002.

- Greer, T. 2019. “Noticing Words in the Wild.” In Conversation Analytic Research on Learning-in-Action: The Complex Ecology of L2 Interaction in the Wild, edited by J. Hellermann, S. Eskildsen, S. Pekarek Doehler, and A. Piirainen Marsh, 131–158. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Greer, T., M. Ishida, and Y. Tateyama. 2017. Interactional Competence in Japanese as an Additional Language. Honolulu: National Foreign Language Resource Center.

- Haugh, M. 2010. “Jocular Mockery, (Dis)affiliation, and Face.” Journal of Pragmatics 42 (8): 2106–2119. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2009.12.018.

- Hosoda, Y. 2014. “Missing Response after Teacher Question in Primary School English as a Foreign Language Classes.” Linguistics and Education 28: 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2014.08.002.

- Jefferson, G. 1979. “A Technique for Inviting Laughter and Its Subsequent Acceptance/Declination.” In Everyday Language: Studies in Ethnomethodology, edited by G. Psathas, 79–96. New York: Irvington.

- Jefferson, G. 1981. “The Abominable Ne?: An Exploration of Post-Response Pursuit of Response.” In Dialogforschung. Jahrbuch 1980 Des Instituts Für Deutsche Sprache, edited by P. Schröder and H. Steger, 53–88. Düsseldorf: Pädagogisher Verlag Schwann.

- Jefferson, G. 1990. “List Construction as a Task and Interactional Resource.” In Interaction Competence, edited by G. Psathas, 63–92. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- Jefferson, G. 2004. “Glossary of Transcript Symbols with an Introduction.” In Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation, edited by G. Lerner, 13–34. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Kasper, G., and Y. Kim. 2007. “Handling Sequentially Inapposite Responses.” In Language Learning and Teaching as Social Inter-action, edited by Z. Hua, P. Seedhouse, L. Wei, and V. Cook, 22–41. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Koole, T. 2010. “Displays of Epistemic Access: Student Responses to Teacher Explanations.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 43 (2): 183–209. doi:10.1080/08351811003737846.

- Koshik, I. 2002. “Designedly Incomplete Utterances: A Pedagogical Practice for Eliciting Knowledge Displays in Error Correction Sequences.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 35 (3): 277–309. doi:10.1207/S15327973RLSI3503_2.

- Koshik, I. 2005. “Alternative Questions Used in Conversational Repair.” Discourse Studies 7 (2): 193–211.doi:10.1177/1461445605050366.

- Kurhila, S. 2006. Second Language Interaction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Margutti, P. 2006. “Are Fa Si Human Beings? Order and Knowledge Construction through Questioning in Primary Classroom Interaction.” Linguistics and Education 17 (4): 313–346. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2006.12.002.

- Maynard, D. W. 1989. “Perspective Display Sequences in Conversation.” Western Journal of Speech Communications 53 (2): 91–113. doi:10.1080/10570318909374294.

- Mondada, L. 2018. “Multiple Temporalities of Language and Body in Interaction: Challenges for Transcribing Multimodality.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 51 (1): 85–106. doi:10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878.

- Norrick, N. 2004. “Hyperbole, Extreme Case Formulation.” Journal of Pragmatics 3 (9): 1727–1739. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2004.06.006.

- Okada, Y., and T. Greer. 2013. “Pursuing a Relevant Response in OPI Roleplays.” In Pragmatics and Language Testing, edited by S. Ross and G. Kasper, 294–316. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pomerantz, A. 1984a. “Pursuing a Response.” In Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis, edited by J. M. Atkinson and J. Heritage, 152–166. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Pomerantz, A. 1984b. “Agreeing and Disagreeing with Assessments: Some Features of Preferred/Dispreferred Turn Shapes.” In Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis, edited by J. M. Atkinson and J. Heritage, 57–101. Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press.

- Pomerantz, A. 1988. “Offering a Candidate Answer: An Information Seeking Strategy.” Communication Monographs 55 (4): 360–373. doi:10.1080/03637758809376177.

- Reinelt, R. 1987. “The Delayed Answer: Response Strategies of Japanese Students in Foreign Language Classes.” The Language Teacher XI 11: 4–9.

- Sacks, H. 1992. Lectures on Conversation. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Schegloff, E. A. 1979. “The Relevance of Repair to Syntax-for-Conversation”. In Discourse and Syntax, Vol. 12. edited by T. Givon, 261–286. New York: Academic Press.

- Schegloff, E. A. 2007. Sequence Organization in Interaction: A Primer in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Seo, M. S., and I. Koshik. 2010. “A Conversation Analytic Study of Gestures that Engender Repair in ESL Conversational Tutoring.” Journal of Pragmatics 42 (8): 2219–2239. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2010.01.021.

- Sert, O. 2013. “‘Epistemic Status Check’ as an Interactional Phenomenon in Instructed Learning Settings.” Journal of Pragmatics 45 (1): 13–28. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2012.10.005.

- Sidnell, J., and T. Stivers. 2012. The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Stevanovic, M., and A. Peräkylä. 2012. “Deontic Authority in Interaction: The Right to Announce, Propose, and Decide.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 45 (3): 297–321. doi:10.1080/08351813.2012.699260.

- Stivers, T., and F. Rossano. 2010. “Mobilizing Response.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 43 (1): 3–31. doi:10.1080/08351810903471258.

- Stokoe, E., and D. Edwards. 2008. “`did You Have Permission to Smash Your neighbour’s Door?‘ Silly Questions and Their Answers in Police—suspect Interrogations.” Discourse Studies 10 (1): 89–111. doi:10.1177/1461445607085592.

- Svennevig, J. 2012. “Reformulation of Questions with Candidate Answers.” International Journal of Bilingualism 17 (2): 189–204. doi:10.1177/1367006912441419.

- Wong, J., and H. Z. Waring. 2009. “‘Very Good’ as a Teacher Response.” ELT Journal 63 (3): 195–203. doi:10.1093/elt/ccn042.

Appendix A1

Transcription conventions

The transcripts follow standard Jeffersonian conventions (Jefferson Citation2004), with embodied elements shown via a modified version of the conventions developed by Mondada (Citation2018). The embodied elements are positioned in a series of tiers relative to the talk and rendered in grey.

| | Descriptions of embodied actions are delimited between vertical bars

| – > The action described continues across subsequent lines

– -|The action reaches its conclusion

≫The action commences prior to the excerpt

– ≫The action continues after the excerpt

….Preparation of the action

– -The apex of the action is reached and maintained

~~~~ The action moves or transforms in some way.

AKI The current speaker is identified with capital letters

Participants enacting an embodied action are identified relative to the talk by their initial in lower case in another tier, along with one of the following codes for the action:

-gzgaze

-lhleft hand

-rhright hand

-bhboth hands

-pxproximity

-hdhead

-gsgesture

Anonymised framegrabs are positioned within the transcript relative to the moment at which they were taken.

Following Greer, Ishida, and Tateyama (Citation2017), Japanese talk has been translated via the following additions:

First tier: Original Japanese rendered in Hepburn romanisation

Second tier: Word-by-word gloss (Italicised Courier font)

Third tier: Vernacular translation (Italicised Times font)

In cases where the turn extends over several lines, the third-tier vernacular translation only appears after the end of the complete TCU. If the Japanese consists of a single morpheme embedded within an otherwise English turn at talk, the third-tier translation is not given.

Abbreviations used for Japanese morphemes in the word-by-word gloss tier are as follows:

COPcopula (e.g., da, desu)

HMhesitation marker (e.g., e::, ano)

CoSchange-of-state token (ah)

RTreceipt token

NGnegative morpheme (-nai)

VOLvolitional verb form

GERgerundive verb form