ABSTRACT

This paper analyses the practice of participatory budgeting in Porto Alegre, Brazil, through an interdisciplinary lens that combines the theories of right to the city, environmental justice and deliberative democracy. It examines the democratic and deliberative nature of the participatory process as well its social, environmental and ecological outcomes. While participatory budgeting has been widely studied and internationally recognised, it has rarely been assessed in its ability to bring about urban sustainability. This analysis demonstrates that it is principally the deliberative nature of the participatory process that has allowed it to have a positive impact on the urban environment. In doing so, this article proposes key recommendations to successfully replicate this mechanism in order to face the various environmental and social challenges of the Anthropocene and contribute towards achieving the sustainable development goals.

1. Introduction

The twenty-first century has brought crucial challenges to our globalised and urbanised planet. As ecosystems are being destroyed and natural resources are dangerously running out, global capitalism is overshooting critical planetary boundaries and bringing about an unprecedented environmental collapse (Meadows et al. Citation1992; Rockström et al. Citation2009). The impacts of human activities on this planet have reached such an extent that we have arguably entered an entirely new geological epoch: the Anthropocene (Waters et al. Citation2016).

In these conditions, citizens are becoming increasingly frustrated towards a system that is not capable of securing its economic and environmental stability and in which inequalities rise while millions remain without access to basic human necessities (von Weizsäcker and Wijkman Citation2018). Faced with these challenges many groups have sought for more meaningful democracies so people can have the agency to shape their societies rather than letting decisions fall in the hands of a few. Amongst them are Nuit Debout in France, the anti-austerity movement in Greece, Occupy in the capitals of the world, 15-M Indignados in Spain, Arab and Kurd revolutionaries in the Middle East and Quebec students of the maple spring (Harvey Citation2012). On the other hand, many others have felt disillusioned with democracy as a whole and have recently voted for authoritarian populists hoping that they will improve the status-quo. In these conditions, democracy faces with a crucial challenge in order to demonstrate that it can work effectively and efficiently towards solving the social and environmental challenges of the twenty-first century; otherwise, authoritarian solution will become ever-more appealing.

Those demanding greater democracy such as the indignados and Occupy movements have expressed the desire to build a more direct and local form of governance through mechanisms such as participatory budgeting (PB or OP for its abbreviation in Portuguese) (Molina Molina Citation2011). While participatory budgeting can take many different forms and shapes, its main structure consists of local popular assemblies where citizens can directly deliberate on the use of the city’s budget as well as on other major planning priorities.

This paper will examine the process and outcomes of participatory budgeting and analyse whether it is capable of contributing towards the social and environmental sustainability that our world so urgently needs. To do so, this paper will assess the case of Porto Alegre, Brazil as it is the first and one of the most iconic and representative cases of PB in the world (Fung Citation2011). The theoretical framework will be based on an interdisciplinary approach that combines the right to the city, environmental justice and deliberative democracy. Moreover, the sustainable development goals (SDGs) will be used to contextualise the outcomes of PB with the targets set by the UN in order to overcome the sustainability challenges of the twenty-first century.

This paper fills an important research gap on the topic as most research has focused on the PB process itself; but much less attention has been placed on its actual social and environmental outcomes.Footnote1 This research will thus contribute to the debate on deliberative democracy and its potentials to bring about greater level of social and environmental sustainability.

Section 1 will examine the theoretical framework of environmental justice, right to the city and deliberative democracy. Section 2 will describe the context of Porto Alegre and how its PB works. Section 3 will evaluate the deliberative nature of Porto Alegre’s PB process. Section 4 will assess the socio-environmental outcomes of PB by examining the investment priorities ranked through PB, how they were implemented and how they have affected urban socio-environmental conditions. Section 5 will discuss the results and their significance for democracy, sustainability and resilience in the Anthropocene.

2. Theoretical framework

Representative democracies have critical problems of inequality, voice and participation, which have seriously affected their ability to deal with the social and environmental challenges of the Anthropocene (Fuentes-Nieva and Galasso Citation2014; Christoff and Eckersley Citation2013; Dryzek and Stevenson Citation2011; Bäckstrand et al. Citation2010; Downey and Strife Citation2010; Cohen and Fung Citation2004). In response to this challenge, theories of political participation and environmental democracy have grained greater attention.

Notable theoretical approaches include the right to the city, which demonstrates how citizens have become alienated from the freedom to control their lives by controlling their cities and thus shaping their own socio-ecological environments and how this will affect their lives (Lefebvre Citation1968; Harvey Citation2008). This right is to be achieved by controlling the creation and accumulation of capital generated by urbanisation, and hence controlling the economic and social basis of industrial capitalism. The right to the city is thus the right for citizens to directly govern their economies, their society and their future by co-creating their cities; henceforth becoming true agents of change rather than simple spectators (Harvey Citation2012).

Environmental justice theories are also concerned with democracy by showing the links between the exploitation of nature and that of people as well as the importance of developing participatory forms of governance in order to prevent unequal distributions of environmental ‘goods and bads’ (Agyeman Citation2005; Schlosberg Citation2007). Overall, environmental justice promotes the equal capabilities for all people to obtain and manage the social and environmental goods and services they need without preventing the ability of future generation to meet and manage their own.

Deliberative democracy theories are also concerned with practical and tangible solutions to democratic problems by designing and assessing various forms of democratic participation such as citizen forums, deliberative polls, referendums and participatory budgeting. Deliberative democracy theories thus seek to develop institutions and establish principles that enable the creation of green, inclusive and participatory democracies.Footnote2

The main argument behind deliberative democracy is that participatory democracy is enhanced and reinforced by the process of deliberation (Dryzek and Stevenson Citation2011). But what does deliberation mean? Dryzek describes deliberative democracy as a process where individuals ‘are amenable to changing their minds and their preferences as a result of the reflection induced by deliberation’ (Citation2000, p. 31).

In contrast to confrontational modes of decision-making, common in representative democracies, where a handful of self-interested individuals entrenched in their own ideologies compete against one another for influence and power; deliberation proposes a model where a plurality of people cooperate respectfully in an attempt to reach a common agreement that will lead to a positive-sum outcome for all (Smith Citation2003). Fung and Wright distinguish between adversarial and collaborative decision-making to show the difference between a deliberative form of collective agreement and the political confrontation so common in neoliberal democratic systems:

In adversarial decision-making, interest groups seek to maximize their interests by winning important government decisions over administrative and legal programs and rules, typically through some kind of bargaining process. In collaborative decision-making, by contrast, the central effort is to solve problems rather than to win victories, to discover the broadest commonality of interests rather than to mobilize maximum support for given interests. (Fung and Wright Citation2003, p. 261)

There are various benefits to a deliberative process. First of all, it grants legitimacy to the outcome. As Manin puts it: ‘the source of legitimacy is not the predetermined will of individuals, but rather the process of its formation that is deliberation itself’ (quoted in Smith Citation2003, p. 58).

Deliberation also results in more efficient and insightful decisions by exponentially increasing the amount of people involved and the number of views heard (Eckersley Citation2004). This enhances the information flows resulting in a greater number and diversity of interactions. By making all relevant actors actively participate in decision-making process; outcomes gain an insight unattainable to decisions taken by a handful of distant bureaucrats or politicians who are rarely directly affected nor held accountable (Dryzek Citation2000; Smith Citation2003; Cohen and Fung Citation2004).

Yet deliberation is certainly not an easy process. How can people let go of their differences and cooperate for the common good? Dryzek (Citation2000) and Smith (Citation2003) demonstrate that deliberation requires an ‘enlarged mentality’ in order to work. Similarly, Mason shows that a green democracy needs ‘green citizens’ (Citation1999). The idea is that people must look at problems beyond their individual perspective and with a greater outlook at the plurality of other’s opinions, views and values. Deliberation is thus about building a decision based on constructive ‘good faith’, justified reasoning, understanding and respect as well as a thoughtful consideration for the common good (Steenbergen et al. Citation2003; Fishkin Citation2011; Dryzek Citation2012). An ‘enlarged mentally’ also entails a level of environmental awareness where people can reach beyond anthropocentric views in order to understand themselves as an integral part of nature rather than being ontologically separated from it (Mason Citation1999; Eckersley Citation2004).

The process of deliberation itself is key to create this ‘enlarged mentality’. In fact, it has been shown that deliberating in a well-facilitated process of democratic problem-solving can bring about the environmental and long-term thinking and the greater commitment to the common good that deliberative democracy seeks (Fung and Wright Citation2003; Smith Citation2003; Bäckstrand et al. Citation2010; Dryzek Citation2012). In addition to this, experiments and investigations have shown that people do change their minds after deliberating rather than remaining entrenched in their individual or ideological positions (Mason Citation1999; Dryzek Citation2000; Cohen and Fung Citation2004). The contact and discussion between people of various different views and the interaction with a plurality of ideas, including ecological ones, influences people to adopt both a greener and a more collaborative perspective (Eckersley Citation2004). Participatory deliberative democracy hence acts as a form of ‘citizenship school’ that can produce the change in worldviews and generates the mentality necessary for its success (Mason Citation1999; Dryzek Citation2000; Smith Citation2003; Eckersley Citation2004).

However, the political, social and environmental benefits of deliberative democracy largely dependent on the quality of deliberation that takes place. A central question is thus finding out what are the practical means and institutions that can bring about the best forms of deliberation. Many see PB as one of the most successful forms of deliberative democracy (Baiocchi Citation2003; Fung and Wright Citation2003; Cabannes Citation2004a; Gret and Sintomer Citation2005). As Fung puts it: ‘participatory budgeting is perhaps the most widespread and authoritative institutionalization of participatory democratic ideas anywhere in the world’ (Citation2011, p. 860). Even international organisations such as the Word Bank (WB) have promoted Participatory Budgets and in 1996 the UN named it one of the best 40 practices at the Istanbul Habitat II Conference (Wampler Citation2012).

However, not all PBs are equal and depending on the type and quality of the PB, very different benefits arise and diverse challenges are posed. This paper analyses the PB in Porto Alegre, arguably the most successful and amongst the most democratic and transformative forms of PB that have been carried out to this day (Cabannes Citation2015). By looking at this case, this paper attempts to test whether deliberative democracy can lead to just and sustainable outcomes.

3. Porto Alegre’s experiment with participatory budgeting

Following the return to democracy in 1988, Porto Alegre began a process of political and social transformation as the Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT) was voted in office for the first time. The PT was, at the time, a relatively small party and it took office in a moment when many strong social movements were advocating for direct citizen participation. Moreover, the new 1988 constitution increased decentralisation by granting greater powers and budgets to municipal governments. The constitution also mandated mechanisms of greater citizen participation but did not stipulate exactly what they should be. In this context, the PT decided to respond to both civil society’s demand for participation and the new constitutional opportunities with one of the most transformative experiments of local democracy at the time: participatory budgeting.

It is important to note that the deliberative nature of PB has changed substantively after the PT left office in 2004 and this has considerably reduced the quality of the process and its potential to bring about positive environmental outcomes (Marquetti et al. Citation2012; Melgar Citation2014). While after 2004, the PB maintained most of its formal rules and procedures, it was relegated to a secondary role in the city’s planning with the ability to decide only on a limited percentage of the capital budget (Rennó and Souza Citation2012). The OP was even suspended in 2017, only to be reinstalled latter in a different form (Núñez Citation2018). Since this paper attempts to evaluate and gain insights from the OP as a meaningful democratic experiment, it is imperative to evaluate the OP at a time when it can actually be assessed as such. This study thus describes the PB process as it was during the 1989–2004 period and the analysis in the next sections describes how deliberative aspects and socio-environmental outcomes have changed since then.

3.1. Porto Alegre’s participatory budgeting

To implement the participatory budget in a city as large as Porto Alegre (with over 1.4 million inhabitants) the municipality was sub-divided into 17 more manageable districts. Additionally, since 1994, five citywide Sectoral Assemblies were introduced to deal with more wide-scale municipal themes.Footnote3 The participatory process is structured around a yearly cycle with three phases.Footnote4

3.1.1. Phase 1 of the OP

This phase lasts from March to June and has two main rounds of deliberation as well as intermediary meetings in between.

The first round goes on from March to April with large Plenary Assemblies that are open to all citizens. In these Assemblies, citizens are first brought to review and monitor the implementation of the previous year’s Investment and Services Plan (PIS). The PIS is the yearly budgeting plan that contains all the projects and investments decided in the last PB cycle. During the Plenary Assemblies citizens also elect Delegates, which are a backbone of the PB process by creating a link between government and citizens. Finally these Plenary Assemblies decide on the citywide thematic priorities that will be ranked in later on.Footnote5

After this first round, a series of intermediary meetings are held from April to May. These consist of small community discussions organised independently by civil society and OP Delegates at the micro-local level (neighbourhoods, streets and apartment buildings). These meetings allow citizens to discuss concrete projects and investments that need doing as well as the ranking of the citywide thematic priorities.

The second round of Plenary Assemblies, open to all citizens, begins in June. In these large Plenary Assemblies, citizens vote on the final ranking of thematic priorities and on specific investment projects. In this round, Councillors are also elected amongst the Delegates and will be responsible for the next phase of the PB process.

3.1.2. Phase 2 of the OP

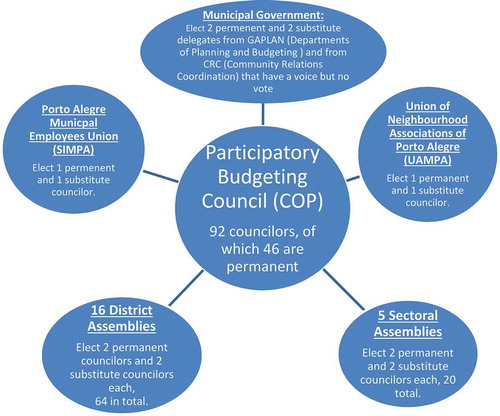

The second phase of PB starts in June and two major organs are responsible for this part of process: the Sectoral and District Forums of DelegatesFootnote6 and the Participatory Budgeting Council (COP).Footnote7

Each Forum of Delegates is assisted by the municipal government to review the prioritisation of works and services requested under each theme and assess their urgency and feasibility. Delegates continuously coordinate with civil society and visit various sites and neighbourhoods to evaluate their needs and assess their demands. After the Forums submit a final list of projects and priorities the municipal government prepares cost estimates for every demand.

When the municipality discloses the investment budget estimate, Councillors of the COP coordinate with District and Sectoral Forums to harmonise citizen’s demands and create the PIS. They have to reconcile the thematic priorities and investment projects voted previously with the resources available and with the distribution criteria in order to choose each individual project. This is a complex process that requires deliberation and cooperation between Councillors, Delegates, government workers, citizens and civil society. By December, the PIS is completed and submitted to the City Council (municipal legislative) and to the Mayor for final approval.

3.1.3. Phase 3 of the OP

The third and final phase of the PB process is dedicated to the implementation and monitoring of the PIS as well as the revision of PB procedures. Once the Mayor and the City Council approve the PIS, the municipal government starts public works in January. In the meantime the COP, in collaboration with the 21 Forums of Delegates, review and change PB guidelines and regulations in order to improve the process. The monitoring and evaluation of project completion is also carried out by the COP and the 21 Forums of Delegates until the next Council and the next Forums are voted.

4. Results: assessing PB with seven comprehensive variables

This section will assess the OP with each one of the seven dimensions developed by Cabannes (Citation2004a) in order to evaluate the democratic and deliberative nature of the process. These seven criteria are not only consistent with other indicators and methods, which have been recently developed in order to assess deliberative quality and deliberative systems (Steenbergen et al. Citation2003; Fishkin Citation2011; Dryzek Citation2012; Schouten, Leroy and Glasberg Citation2012), but they are also amongst the few robust methodologies which have been designed specifically for participatory budgeting. These indicators thus provide with a solid and verified instrument, which effectively adapts the principles of deliberative and participatory democracy to the specificities of PB.

4.1. Direct democracy and community-based representative democracy?

PB has levels of both direct and representative democracy. In the first phase, citizens participate directly in the decision-making process by proposing projects and ranking priorities. On the other hand, phase 2 and 3 are a mix of representative and direct process led by elected Delegates and Councillors. The PB is thus different form the forms representation typical to liberal democracies. Indeed, Delegates and Councillors are in constant communication, collaboration and deliberation with civil society though the entire process and do not represent a small minority of economic elites or bureaucrats. An analysis of the profile of Delegates and Councillors shows a good representation of the most marginalised groups in society (see below).

Table 1. Profile of participants in PB, 2000.

also demonstrates that PB participants are generally from disadvantaged sectors of the population. Although at first the OP was rather male dominated, women participation has continually increased with time and by 2007 there was full gender parity in participants, Delegates and Councillors (Marquetti et al. Citation2012). This is a significant improvement compared to traditional representative institutions like the City Council of Porto Alegre and the National Congress of Brazil where this number has never gone above 12%. Also, while councillors and delegates have a higher economic and educational level than other participants they are still less educated, poorer and more often afro descendant than the average citizen of Porto Alegre (see ). Yet there are still some limits to participation since the youth, Caucasians, middle and upper economic classes and entrepreneurial professions are less well represented (Fedozzi et al. Citation2013). This can be attributed to the fact that participatory budgeting is generally concerned with the provision of basic services and infrastructure for the poor. The OP thus lacks power in more wide-ranging policy and planning issues that could interest other social groups (WB Citation2008). Moreover, after term limits for councillors were eliminated in 2007, there has been a concerning lack of alterability as the rate of renovation of the COP fell to less than 30% (Núñez Citation2018). This further limits the democratic plurality and inclusiveness of the PB.

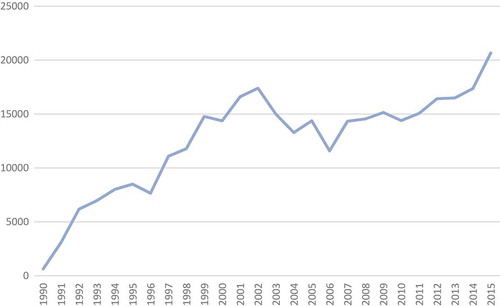

As we can see from , the number of participants in the PB process has continually increased but remains limited to about 1% of the total city population. Those numbers only represent people that attended District and Sectoral Plenary Assemblies. During local intermediary neighbourhood meetings of phase 1, many more are involved indirectly. About 19.8% of Porto Alegre’s residents have thus participated in the PB process at some point in time by 2006 (WB Citation2008). It is worth noting that the number of participants decreased after the weakening of the PB in 2004, and later rose substantially from 2011 onward. Despite the reduction in power of the OP after 2004, citizens still highly valued this process (see ) and perhaps sought to contrast its political weakening with a rise in participation.

Table 2. OP demands per municipal department, 1990–2007.

Table 3. Porto Alegre: participatory budgeting district thematic priorities.

Table 4. Municipal budget distribution by sector, 1989–2000 (millions of Reais).

Table 5. Percentage of investment projects completed and Total Investment in the OP in Porto Alegre.

Table 6. Evolution of social and environmental indicators in Porto Alegre.

Table 7. Survey of public perception of OP in Porto Alegre by percentage of population, 2006.

Figure 1. Participants in the PB Process in Porto Alegre (ObservaPoA Citation2017).

4.2. City-based participatory democracy and community-based participatory democracy?

The PB process in Porto Alegre has a good balance between city-based and community-based participation thanks to District and Sectoral Assemblies that permit people to be engaged in citywide themes or on local needs. Moreover, the COP is in charge of balancing municipal and district priorities as it has to build a PIS, which is adapted to the needs of each region while accounting for objectives of the city as a whole. However, it has been pointed out that there exists a general lack of coordination with other municipal institutions such as the Municipal Councils, the Urban Fora and the City Congress (WB Citation2008). This leads to disconnected and segmented planning decisions, as the OP responds to rather small-scale and short-term necessities without coordination with the city’s long-term development plans. This reduces the ability of the OP to deal with complex long-term issues and to develop multi-sectorial strategic objectives for the city.

4.3. What body is in charge of the participatory decision-making?

The COP is the most powerful and important body in the OP since it is in charge of creating the PIS. The diversity of members that constitute it, coming from civil society, sectoral and district assemblies as well as municipal government representatives allow for a relativelly inclusive and comprehensive collaboration to occur (see below). The continuous collaboration, interaction and negotiation of the COP with civil society, OP Delegates and the municipal government also make it a strongly deliberative institution.

Figure 2. The Composition of the COP in Porto Alegre (2004Footnote8).

4.4. Who makes the final budget decision?

While the mayor and city council give the final budget approval, their power is very limited as they can only make minor revisions and have historically done very few changes to the PIS. Members of the municipal legislative are even more reluctant to make changes as it might weaken their electoral support. The final budgeting decision hence remains essentially in the hands of the COP and thus, of civil society (Gret and Sintomer Citation2005). However, from 2005 onwards, Mayors have had a much heavier hand on the final PIS by directly changing priorities and projects as well as reducing its budget, thereby considerably weakening this deliberative dimension of the OP (Melgar Citation2014).

Moreover, while OP participants, and Councillors in particular, took the final budget decisions until 2004, there was nonetheless an overall lack of knowledge regarding the PB process that limited the decision-making capacity of PB participants. Surveys show that, in 2005, after 17 years of PB, 55.8% of first-time participants in the OP process know few or none of the rules (WB Citation2008, p. 34). With time this problem diminishes as those that have participated for various years in a row have a much more comprehensive knowledge of the process; indeed 11.7% of those that have participated 8 years know few or none of the rules (WB Citation2008, p. 34). Nonetheless, this creates an inequality between participants limiting the internal accountability of Councillors and Delegates who are generally better informed than others. It also created a knowledge barrier to enter the OP process and it prevents those that participate to do so in a well-informed manner, which can result in communication problems, and sub-optimal outcomes.

4.5. How much of the total budget is controlled by the participatory bodies?

Up to 2004, citizens controlled 100% of the capital investment budget through the OP; these are the funds remaining after all maintenance and administrative costs (WB Citation2008). Capital investments have greatly increased after the implementation of the PB rising from 2% of total expenditures in 1989 to an average of 10% from 1990 to 2000. This is mostly due to the fact that the municipal government was able to implement tax increases and tax collection rates have risen as people became more willing to pay them once they have a greater control over their use (IADB Citation2005). Overall, citizens control funds representing over USD$ 300 per inhabitant through the PB (Cabannes Citation2004a).Footnote9

In addition to the significant budget invested through the PB, many resources are spent on the process itself. Various different cultural and recreational entertainments are proposed to stimulate involvement and attendance during the festive first phase of Plenary Assemblies (Gret and Sintomer Citation2005). An activity bus with games for children is also provided so that parents can attend (Baiocchi Citation2005). Furthermore, technical training and assistance is given to Delegates and Councillors, and city employees facilitate assemblies with all necessary technology and equipment. The municipal government also covers the transport costs of Delegates so they can attend major OP assemblies and travel to each neighbourhood in order to hold parallel meetings and deliberate about their various demands (Gret and Sintomer Citation2005).

However, after 2004, the deliberative quality of this variable changed substantially as the percentage of the total investment budget controlled through the OP was significantly reduced (Melgar Citation2014). For instance, in 2008 the OP represented only 9.6% of the investment budget, and in 2016, it represented merely 5.4% (Núñez Citation2018). In addition to this, the budget and municipal team dedicated to the functioning and coordination of the OP was also considerably reduced. This affected the support available to Delegates and Councillors as well as the resources available to encourage participation (Rennó and Souza Citation2012).

4.6. Social control and inspection of works once the budget has been approved?

Monitoring and evaluation is a central component of the PB process and there is a comprehensive level of municipal transparency to allow it. Plenary assemblies in phase 1 permit a review of last year’s PIS and phase 3 includes various mechanisms for the continuous monitoring and evaluation of projects. Not only are the COP and Forums of Delegates in charge or supervising and observing the completion of projects but the transparency of the process permits every citizen to account for the budget through the printed PIS booklet, the PB website and the discussions in preparatory meetings of phase one. However, the monitoring process is limited by three major factors:

First, people have a very limited knowledge of the PB process (see part 3.4) and of the municipal budget as a whole. As much as 69% of surveyed PA citizens consider themselves as ‘without much information’ regarding the municipal budget. While this figure decreased for OP participants, it remains high at 57% (WB Citation2008, p. 69). This seriously affects their ability to effectively monitor the PIS and the OP.

Secondly, while information is generally available for people to consult, it is often too technical to be understood or hard to find. Moreover, financial literacy and monitoring and evaluation skills and competencies remain low, which limits the capacity of delegates and councillors to audit and assess public works effectively (WB Citation2008).

Finally, there is a monitoring gap in the design and technical implementation of projects once they have been approved. In fact, monitoring and evaluation consists almost entirely on the actual physical completion and adequacy of projects and does not include social and environmental considerations or design details.

4.7. Degree of formalisation and institutionalisation?

One of the most important characteristics of the PB in Porto Alegre is its ability to continuously evolve and be improved by citizens. The regimento interno, stipulating the rules and procedures, is revised and amended every year by citizens in phase 3. This institutional flexibility is a great strength that allows the process to become more democratic and to adapt to changing social circumstances. However, this can also be seen as a weakness as it permits the process to be debilitated or co-opted by a less supportive government (as occurred after 2004).

4.8. Analysing the PB process

It is clear that Porto Alegre’s PB has some limitations, especially in terms of monitoring, information, complexity, formal institutionalisation and effective coordination with other municipal institutions. Nonetheless, Porto Alegre’s PB can still be seen as a solid example of deliberative democracy thanks to the considerable amount of power that it concedes to citizens, its strong coordination with civil society, its plurality and breadth of participation, and its ability to continuously evolve democratically. All of these outcomes directly contribute to many SDGs related to participation (target 16.7), gender equity (target 5.5), inclusive urban governance (target 11.3), corruption (target 16.5) and transparency (target 16.6). However, after 2004, the OP suffered important changes, which considerably weakened this deliberative quality by reducing the percentage of the municipal investment budget controlled through the OP (variable 5) and by allowing the municipal government to make discretional changes to the democratically constructed budget (variable 4) (Núñez Citation2018).

5. Results: assessing environmental outcomes

The previous analysis revealed that PB is a successful deliberative process. This section will assess the outcomes of this process. It is worth noting that the following assessment of Porto Alegre’s PB will be evaluating the environmental figures and outcomes for years 1991, 2000 and 2010 as the vast majority municipal level data is only available for those years, which correspond to the national population censuses carried out by the IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics). This allows for a general comparison between the 1989–2004 period and the period after 2004 by contrasting results from 1991 to 2000 with those from 2000 to 2010.

shows that street paving, water and sanitation and housing have occupied a predominant position in people’s demands. SMOV, the institution responsible for street paving, obtained the majority of total OP demands, followed by DMAE, responsible for water and sanitation, and in third place DEMHAB, responsible for housing. The importance of these priorities demonstrates how the most pressing needs were to ameliorate the built environment as this can improve people’s quality of life in the most fundamental manner.

Since water is most expensive for the poor, access to running water brings a considerable addition to available income for other uses and significantly reduces the danger of contracting diseases (Satterthwaite Citation2003). Paving is also essential as it guarantees access to waste collection, public transportation, rainwater drainage, street lighting and sidewalks, which greatly enhances the health conditions, mobility, security and human dignity of urban residents (Menegat Citation2002). Sanitation and sewer connections also bring about similar benefits in terms of health and well-being (Satterthwaite Citation2003). It is also worth noting that SMAM (municipal department of environment, responsible for green areas) occupies the seventh place, with 4.6% of total demands, showing that citizens have also attached a relatively significant importance to ecological concerns.

demonstrates the evolution of priorities through time. Water and sanitation systematically ranks highly from 1992 to 2001 and disappears from then onwards. This can be explained by the fact that by 2000 the sewage network reached over 84% of households and access to running water was at 98.13% (see ).

After basic concerns were resolved, there is a shift in priorities towards more social aspects such as health and education.

and demonstrate what priorities people have demanded, but have they actually obtained greater investments in those areas? confirms that OP priorities were translated into investments in the corresponding municipal budget sectors from 1990 to 2000. However, the situation is reversed after 2004, as PB priorities no longer correspond to municipal investments (Rennó and Souza Citation2012). For instance, during the 2010 fiscal year health and sanitation received the largest percentage of the municipal budget (25% and 19.46%, respectively) while the areas of housing, education and social assistance obtained 2.31%, 15.62% and 9.15% of the municipal budget respectively, despite being the top ranked priorities that year (ObservaPoA Citation2017).

By examining the percentage of projects completed one can understand whether these investments actually resulted in new green and grey infrastructure. Between 1990 and 2001, the municipal government met a great majority of investment demands. However, there was an economic downturn in all of Brazil in early 2000s (2000–2003), which affected Porto Alegre’s budget and has caused this figure to drop (WB Citation2008). When the PT left office in 2004 these figures further deteriorated and there was a significant reduction in investments in the PB, despite the fact that Brazil’s economy improved in that same period (see ). The percentage of completed PB projects continued to drop after 2010, and from 2013 to 2016 only 8.6% were completed (Núñez Citation2018).

5.1. Urban environmental management through PB

As indicates, PB investments have significantly impacted various socio-environmental factors. As Porto Alegre devoted the city’s entire investment budget to the OP (at least until 2004), and since improvements in environmental and social conditions involve investments in green or grey infrastructure, it is fair to assume that progress in those areas are attributable to the OP.

By 2002, access to treated water increased to a near universal coverage and the proportion of unaccounted-for water was significantly reduced. This occurred while the price of water remained one of the most affordable in Brazil (Hall et al. Citation2002).

In terms of sanitation, PA’s sewer network became the most inclusive in the country by almost doubling its coverage (Hall et al. Citation2002). Additionally, the percentage of treated wastewater increased more than tenfold. The treatment of wastewaters has allowed a process of cleaning the shores of the Lake Guaíba and the restoration of major beaches such as the Belém Novo and Lami, which have become safe to bathe in since 2002 (Hall et al. Citation2002).

The SMOV has also brought about significant improvements in street paving and transportation. Approximately 30 km of roads with street lighting, drainage and sewage were built every year (Menegat Citation2002). By 2010, 88% of households had paved roads and 94% had street lighting thus reducing the deficit of paved roadways from 690 km in 1998 to 390 km in 2003 (Cabannes Citation2004). Additionally, PA’s public transit system is considered to be a model in Brazil gaining the title of ‘best company of urban transport of the country’ in 1999, and 2001 (Carris Citation2017). Yet, it is facing some major problems as transit tickets are amongst the most expensive in the country (ANTP Citation2017). Moreover, the city is motorising at alarming rates; while the city’s population grew by 3.63% from 2000 to 2010, the number of passengers in public transport has declined by 1.5% and the fleet of private vehicles increased by 31.2% (EPTC Citation2011; OserbaPoA Citation2017). This has caused Porto Alegre to have the second most polluted air amongst Brazilian capitals behind Sao Paulo (Cifuentes et al. Citation2005). There thus remains a clear necessity to promote and facilitate the use of public transport as well as other alternative forms of transportation.

The waste management system of Porto Alegre has also greatly benefited from PB. Collaboration with local citizens and informal waste collectors through the PB has allowed the creation of an internationally acclaimed system of integrated solid waste management (Dias and Alves Citation2008). In the early 1990s informal waste collectors organised in associations and were incorporated in the recycling and composting system of the DMLU. They obtained access to machinery, water, electricity and facilities to sort the solid waste and sell it directly to recycling firms. After household separation of waste, the 29 trucks of the DMLU collect it from practically every household in the city. From collection around 20% of the waste is recycled in a plant that generates over 700 jobs; the rest is either composted into fertiliser, turned into food for pig farming or sent to a modern sanitary landfill. It is an award winning system which is 50% self-sufficient and one of the most affordable in the entire country costing just US$42 per ton (Bortoleto and Hanaki Citation2007).

The green areas in the city have also continued to expand under the PB increasing from 12.5 m2 per resident in 1989 to 14.3 m2 in 2000 (see ). These numbers are well above the 9 m2 of green space per capita, which is recommended by the World Health Organisation. Presently, Porto Alegre is one of the greenest cities in Brazil, green space occupies over 30% of the total city area and one third of this green space is in dedicated protected areas, with high levels of biodiversity (ObservaPoA Citation2017) . There are more than one million trees just in public streets, this represents a forest of 20 km2 and over 160 different species of trees were identified in the city (Menegat Citation2002). Furthermore, PA has a total of 630 green areas, parks and plazas and 1.3 million m2 of public spaces were arborised from 1989 to 2000 (PMPA, Citation2017).

The above investments in basic services have translated in healthier environmental conditions for all residents. This has contributed to the significant reduction of child mortality as well as an increase in life expectancy. The HDI has hence improved from 0.660 to 0.744 (1991–2000) and became the highest amongst state capitals in Brazil (see ).

It is worth noting that for all the above figures the improvements in the 1991–2000 period were greater than those of the 2000–2010 period (see ). For instance, HDI saw a 12.73% improvement in the 1991–2000 period, and a 8.20% improvement in the 2000–2010 period. Similarly, the number of households with sewage waste connections improved by 38% in the 1991–2000 period, and by 10.26% in the 2000–2010 period (see ). Moreover, Brazil’s average GDP growth was of 2.6% in the 1991–2000 period, and of 3.7% in the 2000–2010 period (WB Citation2008). The above can lead to a hypothesis arguing that, despite having more favourable economic conditions, the decade following the weakening of the PB, was not able to accelerate the improvement in basic socio-environmental outcomes.

However, further research and more precise yearly data is needed to properly compare both periods so one can better assess the outcomes of different municipal governments and contrast them with their approach to the PB. Furthermore, much of the remaining progress in these figures after 2004, could actually be products of the PT period, as socio-environmental investments can take a long time to bring measurable results. Moreover, the PB set a precedent for large investments in social and environmental services in Porto Alegre, creating a standard that all governments following the PT had to maintain.

5.2. Analysing PB’s contribution to urban sustainability

The PB has brought about a great number of environmental benefits, related to various SDGs in the areas of water and sanitation (targets 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, 6.b), waste management (target 11.6), transportation and paving (target 11.2) green areas (targets 11.4 and 11.7) and health (targets 3.2 and 3.9). Moreover, these improvements occurred while the population grew by 7.69% from 1991 to 2000 and by 3.63% from 2000 to 2010 (ObservaPoA Citation2017). The OP was thus able to extend the coverage of many basic services while accommodating for the needs of newcomers. Another important achievement is that the treatment of solid and liquid waste was significantly improved during the same period henceforth partly reconciling the ‘brown and green agendas’ of urban sustainability. Additionally, studies have shown that the majority of those investments were carried out in the most deprived neighbourhoods; validating the important redistributive potential of PB (Marquetti Citation2002; Avritzer Citation2010; Marquetti Citation2012). While, progress remains to be achieved in many areas, Porto Alegre was still able to develop in a more environmentally responsible way than most cities in the global south, and it is considered an example of sustainable urbanism in Brazil (Menegat Citation2002).

6. Discussion: implications and challenges

6.1. The benefits of a radically democratic experiment

By allowing citizens to increase their quality of life without having to wait for the goodwill of an elected government, PB has not only benefited the city as a whole, but most importantly, the situation of the worst-off citizens of Porto Alegre. Indeed, PB is an effective method to fairly and efficiently distribute limited resources and to make sure that they attend the needs of the most vulnerable urban residents. This is particularly necessary in the global south where many basic necessities are not met and the lack of sufficient funds requires strict prioritisations in building infrastructure and providing services. As a planning process that fosters an equal control and a fair redistribution of environmental ‘goods and bads’, the PB essentially creates the conditions to ensure a greater level of environmental justice.

Thanks to these benefits, PB has enjoyed a solid level of legitimacy. shows the results of a survey demonstrating that a majority of citizens have a favourable opinion of it. Despite the fact that this survey was taken in 2006, two years after the weakening of the OP process, people still had a strong commitment and view of it as an important and effective form of governance with key benefits for democracy, quality of life and poverty. This can also explain why people kept participating in large numbers in spite of the changes that happened after 2004 (see ). Additionally, the transparency and accountability of the process has been able to decrease local corruption, patronage and clientelism while improving relations between citizens and their government (Avritzer Citation2006; Hilmer Citation2010). By being able to control the use of their taxes people become more open to pay them as well as more respectful of public goods that communities appropriate as their own (Cabannes Citation2015).

Porto Alegre’s PB has benefited from the wide information-base and local knowledge of each citizen thanks to its inclusive participation rates and its deliberative structure PB has thus increased the efficiency of public services through a better knowledge of needs and necessities of the population and a collective desire to design solutions for the benefit of society as a whole. This participatory structure of governance has thus allowed most public services to remain in government hands rather than being privatised during the three last decades of neoliberalism (Marquetti et al. Citation2012). Moreover, it has been shown that infrastructure built through PB is better maintained, of better quality and less expensive thanks to the legitimacy, ownership and oversight brought by the participatory system (Cabannes Citation2015).

PB has also acted as a form of ‘citizenship school’ by mixing direct democracy and community-based representative democracy in innovative ways . As citizens participate they interact with members of civil society organisations who encourage them to engage with various different social and environmental causes (Gret and Sintomer Citation2005). Since the PB was created, civil society membership has significantly increased and many new associations were initiated (see ). Moreover, PB has built a more positive opinion of democracy amongst participants. In fact, 61.4% of first-time OP participants have a positive opinion of democracy while 77.5% of participants having participated in the PB for eight or more years have a positive opinion of democracy (Fedozzi et al. Citation2013, p. 109). The PB has hence helped in the creation of militant citizens and community leaders. This healthy civil society with a strong oversight capacity has also largely contributed to the elimination of the previous clientelist relations, where public resources were not distributed according to needs but as a result of political favours and relations (Avritzer Citation2006).

Table 8. Basic indicators of civil society organisations, Porto Alegre, 1988–2009.

Finally, PB has helped move the balance of power away from the economy and the state, and brought it towards civil society and the people. By empowering citizens, the OP has mitigated some of the negative social and environmental externalities of capitalism. Moreover, by controlling the capital budget, citizens gain control over part of the surplus capital generated by urbanisation that they can invest to rebuild and redesign their own city. These are essentially the redistributive principles sought by citizens to reclaim their right to the city (Harvey Citation2012).

6.2. The challenges ahead

Beyond the benefits explored above, the OP also has many important limitations and challenges, which have reduced the positive impacts of PB. These points are resumed and explored in below:

Table 9. Principal institutional challenges and solutions to Porto Alegre’s participatory budgeting process.

6.3. Participatory budgeting in the context of global capitalism

Beyond these institutional challenges PB also faces major obstacles due to the nature of the system in which it operates. The economic drivers of neoliberal globalisation have remained in parallel to the democratic and inclusive structure of PB. Porto Alegre’s Gini coefficient has thus increased in the 1991 to 2000 period and poverty and extreme poverty levels have remained stagnant during that decade (see ). While the PB was able to bring major improvements to the living conditions of the poor, the general socio-economic structure remained unchanged. This shows the limitations of local participatory democracy in the context of a globalised capitalist system. Although PB represents a large step towards a better and more inclusive future for all, as long as the general socio-economic structures remain unchanged, more wide-ranging social transformations will be limited. It is only with the arrival of Lula in 2003, and the instauration of wide-scale national measures to combat poverty, that we see poverty levels falling in Porto Alegre (see ).

Table 10. Evolution of socio-economic indicators in Porto Alegre 1991–2000.

Another reason why PB has been unable to adequately deal with the large-scale issues is due to its focus on short-term individual projects and disconnected sectorial topics. This narrow objective prevents it to effectively address multi-sectorial issues like poverty and inequality as well as long-term intergenerational issues like ecological sustainability. Most importantly, PB does not follow nor directly influence or coordinate with the city’s 10-year development plan. This leads to a situation where the OP tackles specific problems in different neighbourhoods or planning sectors, through capital budget investments, but lacks general cohesion, inter-sectorial planning and long-term vision. This is a critical issue that needs to be tackled by all PB’s in the world. In order to address these challenges, the PB process can be expanded to the entire municipal budget, and to the direct creation of municipal plans and ordinances.

The environmental impacts of PB have also been limited by the nature of the environmental problems the biosphere currently faces. Indeed, the environmental challenges brought by the Antropocene necessitate a change in our way of life beyond sustainable urban planning. A radical change in exploitative production structures and cultural habits of mass consumption is necessary (Meadows et al. Citation1992). This change in lifestyle necessitates commitment, education and participation. Indeed, if people participate with knowledge about the environment and its limits, they can voluntarily decide to change the lifestyle that the earth’s life support systems cannot sustain. This decision cannot be imposed. It must be collective, informed and genuine for it to turn out positively and direct democracy could thus the best mechanism there is to peacefully bring about this radical change. PB has already started this process by establishing solid deliberative mechanisms, strengthening the ability of civil society to mobilise people on ecological and social issues, and thus helping towards the creation of an ‘enlarged mentality’.

Expanding PB to provincial level (as was attempted in Rio Grande do Sul) and event to national and international levels, through mechanisms such as deliberative juries or assemblies could encourage further transformative change at larger scales. However, in doing so, it is important to maintain the deliberative nature of those solutions, and grant them tangible decision-making power, otherwise they could have mitigated results that undermine those efforts (Bäckstrand et al. Citation2010; Cabannes and Delgado Citation2015).

6.4. Is participatory budgeting: a universally ‘exportable’ model?

There is much to learn from this participatory model especially considering the democratic and environmental challenges of the Anthropocene and the urgency to achieve the SDGs. Yet the 1700 experiences in PB that were created in over 40 countries around the globe have had mixed results (Cabannes Citation2015). This poses the question of how replicable this model really is.

Overall, PB does not in and of itself guarantee better social and environmental outcomes. It is mainly the quality of the process, which enables citizens to participate equally and deliberatively that enables it to bring about positive outcomes. In that sense, the more deliberative and democratic the nature of the PB process, the greater the social and environmental results. Three main considerations should be kept in mind when trying to export this model; if the below conditions are not met, the PB process will likely lack deliberative quality and could have mixed impacts and results.

First, Porto Alegre had a committed government willing to concede substantial amounts of power to its people by committing its entire investment budget through the PB and dedicating a large amount of resources to this process (at least until 2004). Deliberation is expensive and time consuming, the support of the municipal state is thus vital provide with the various resources needed to create the conditions for an effective deliberation such as informing citizens, training PB Delegates and Councillors, dedicating sufficient municipal staff for the process, generating a collaborative mentality, ensuring transparency, educating citizens and giving incentives for people to participate. Moreover, it is essential to have the political willingness to concede power over the 100% of the investment budget directly to citizens; otherwise the democratic process will not have a significant redistributive power and it will not obtain the necessary popular support, participation and commitment.

Second, Porto Alegre authorities have supported and collaborated with a strong and autonomous civil society. This is vital for the quality of deliberation and the active participation of citizens. As we saw in sections 2 and 3, people need to be mobilised and organised actively through the entire PB process and the government cannot do this by itself. The extensive coordination and deliberation required between various CBOs, NGOs, citizens, Delegates, Councillors and the municipal government is a complex and difficult process. An empowered, diverse and vibrant civil society is hence vital for the positive deliberation between all these groups and for the success of PB.

Third, any PB should be resilient, malleable and carefully adapted local conditions. Even the creation of PB institutions has to be a participatory and deliberative process involving local people. The malleable structure of PB, that can be changed every year by the citizens, allows it to be more easily adaptable to local circumstances and more resilient to changing conditions. Nonetheless, this flexibility must not come at the cost of lacking formal legal institutionalisation, as in the case of PA, this could lead to the weakening of the system by a newly elected unsupportive government.

7. Conclusion

This paper has shown the major benefits and challenges of PB and its potentials and limitations to bring about sustainable change and to achieve a number of SDG targets. We have seen how it is in mainly the deliberative and empowering nature of the PB process, which enabled it to bring about socially and environmentally just outcomes as well as fostering people’s right to the city. Thanks to it, Porto Alegre became a counter hegemonic city, showing the world that another form of globalisation is possible. PB is thus part of an innovative wave of policy solutions originating from the global south, like the Buen Vivir, ubuntu, gross national happiness, the rights of nature and the Yasuní-ITT Initiative (Calisto Friant and Langmore Citation2015; Vallejo Silva and Calisto Friant Citation2015).

Democracy and participation has been desperately lacking in the ways that global capitalism has faced the social and environmental challenges of the Anthropocene. In contrast to this, PB provides with an institutional channel for people to participate, deliberate and think collectively about creative solutions to these same problems. In can thus build better, more resilient and legitimate responses to the challenges our world is currently facing. In those ways PB has demonstrated that deliberation and democracy can bring about the level of social and environmental sustainability that our world so urgently needs, and in doing so, it provides the roadmap for an alternative to authoritarian populism. Nonetheless, PB will have only limited results if it is replicated without consideration for the key elements mentioned in sections 5.2, 5.3 and 5.4. This is a reminder against simply promoting ‘best practices’ in order to achieve the SDGs without also carefully considering why those practices where successful so that those details can also be replicated. New and current participatory budgets could make use of the recommendations presented in this paper to improve their results.

Moreover, PB itself is perfectible and limited for various reasons explained in Sections 5.2 and 5.3. People are only able to control short-term investment decisions at the municipal level and the entire process can be weakened by an unsupportive government. It is thus clear that PB is only a first step towards a more inclusive, sustainable and resilient society. Nonetheless, PB is not only a good first step; it is actually one of the most important ones. Control over 100% the municipal investment budget grants citizens an amount of power that few other participatory mechanisms can provide. By managing investments citizens control the distribution of capital, shifting the balance of power away from the hands of the private and state sectors and bringing it in the hands of the people. It can thus effectively distribute limited resources in order to deliver on key public needs. In addition to this, under the right circumstances, PB can work as a form of ‘citizenship school’ that strengthens civil society and generates an ‘enlarged mentality’, which forges the path towards further transformative change.

Considering the potential of PB, further research is needed to analyse how it can be adapted, replicated, improved and expanded so it can best contribute to a greener and fairer future for all.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the “First Ecuadorian Congress of Urban Studies” held from the 23rd to the 25th of November 2017 in Quito, Ecuador and at the “Second Ecuadorian Congress of Political Sciences” held from the 20th to the 22nd of August 2018 in Quito, Ecuador. The author wishes to thank all the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and recommendations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Martin Calisto Friant

Martin Calisto Friant PhD candidate on the discourse, theory and practice of the Circular Economy at the Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, Utrecht University. Martin holds a BA in Political Science and International Development Studies from McGill University, Canada, a Master in Environment and Sustainable Development from University College of London, England and a Master in Development Studies from the University of Melbourne, Australia. He has been a practitioner in the field of sustainable development for 5 years before starting his PhD.

Notes

1. For some notable exceptions see Cabannes Citation2015; Touchton and Wampler Citation2014; Gonçalves Citation2014; Marquetti et al. Citation2012; Avritzer Citation2010; Boulding and Wampler Citation2010; WB Citation2008; Menegat Citation2002. However, most of these studies evaluate the social impact of PB, and only a couple of them analyse environmental and ecological outcomes.

2. There are many expressions of deliberative democracy and environmentalism. Dryzek described a Discursive Democracy (Citation2000), Mason proposed an Environmental Democracy (Citation1999), Eckersley called for a Green Democratic State (Citation2004), Smith envisaged an Ecological Democratisation (Citation2003) while Fung and Wright pursued an Empowered Participatory Governance (Citation2003).

3. Sectoral assemblies vary each year, in 2002 they were the following: (1) urban planning and development, (sub-divided into environment and sanitation, and city planning and housing); (2) traffic management and public transport; (3) health and social welfare; (4) education, culture and recreation and (5) economic development and taxation (PMPA Citation2002).

4. Please note that the PB process varies slightly each year, as rules are reviewed and discussed in phase 3, the following description presents the process for year 2002.

5. The themes vary each year, in 2002 they were: (1) Water and Sanitation; (2) Street Lighting; (3) Housing; (4) Street Paving; (5) Education; (6) Social Assistance; (7) Health; (8) Economic Development; (9) Recreational Areas and Parks; (10) Sport and Leisure; (11) Culture; (12) Transport; (13) Waste Management (PMPA Citation2002) .

6. There are 21 Forums, one for each district (17) and for each sector (5), and they are constituted by the Delegates, which were elected by the respective District and Sectoral Plenary Assemblies in phase one.

7. The COP is the principal institution in charge of creating the PIS for the whole city and is mainly constituted by the Councillors elected in phase one.

8. The structure and members of the COP change every year as the OP rules are reviewed but the plurality of its constituents has remained similar.

9. It is worth noting that, while the OP controls 100% of the investment budget, this budget has a set of distribution criteria, which rank proposed projects based on three aspects: population size, necessity, and the ranking of the related thematic priority (which is voted in the General Assemblies of phase one). These distribution criteria are designed in order to ensure that resources are distributed in an equitable manner (Marquetti Citation2002).

References

- Agyeman J. 2005. Sustainable communities and the challenge of environmental justice. London: NYU Press.

- ANTP. 2017. Tarifas em capitais e cidades com mais de 500 mil habitantes. [accessed 2017 Sept 22]. http://www.antp.org.br/sistema-de-informacoes-da-mobilidade/tarifas.html

- Avritzer L. 2006. New public spheres in Brazil: local democracy and deliberative politics. Int J Urban Reg Res. 30(3):623–637.

- Avritzer L. 2010. Living under a democracy: participation and its impact on the living conditions of the poor. Lat Am Res Rev. 45:166–185.

- Bäckstrand K, Khan J, Kronsell A, Lövbrand E. 2010. eds Environmental politics and deliberative democracy: examining the promise of new modes of governance. Cheltenham (UK): Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Baiocchi G. 2003. Participation, activism, and politics: the Porto Alegre experiment. In: Archon Fung A, Wright EO, editors. Deepening democracy: institutional innovations in empowered participatory governance. London: Verso; p. 45–76.

- Baiocchi G. 2005. Militants and citizens: the politics of participatory democracy in Porto Alegre. Stanford (CA): Stanford University Press.

- Bortoleto AP, Hanaki K. 2007. Report: citizen participation as a part of integrated solid waste management: Porto Alegre case. Waste Manage Res. 25:276–282.

- Boulding C, Wampler B. 2010. Voice, votes, and resources: evaluating the effect of participatory democracy on well-being. World Dev. 38(1):125–135.

- Brazil A 2017. Atlas do Desenvolvimento Humano no Brasil. Porto Alegre; [accessed 2017 Sept 22]. http://www.atlasbrasil.org.br/2013/pt/perfil_m/porto-alegre_rs

- Cabannes Y. 2004. 72 frequently asked questions about participatory budgeting. In: United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) Urban governance toolkit series. Quito: UN-HABITAT. ISBN: 92-1-131699-5. https://unhabitat.org/books/72-frequently-asked-questions-about-participatory-budgeting/

- Cabannes Y. 2004a. Participatory budgeting: a significant contribution to participatory democracy. Environ Urban. 16(1):27–46.

- Cabannes Y. 2015. The impact of participatory budgeting on basic services: municipal practices and evidence from the field. Environ Urban. 27(1):257–284.

- Cabannes Y, Delgado C, editors. 2015. Participatory budgeting, dossier Nº 1, another city is possible ! Alternatives to the city as a commodity series. Lisbon: Spora. ISBN 978-989-20-5561-9.

- Calisto Friant M, Langmore J. 2015. The buen vivir: a policy to survive the Anthropocene? Global Policy. 6(1):64–71.

- Carris. 2017. Títulos e Conquistas. [accessed 2017 Nov 17]. http://www.carris.com.br/default.php?p_secao=63

- Christoff P, Eckersley R. 2013. Globalization and the environment. Landham (MD): Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Cifuentes LA, Krupnick AJ, O’Ryan R, Toman M. 2005. Urban air quality and human health in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington (DC): Inter-American Development Bank.

- Cohen J, Fung A. 2004. Radical democracy. Swiss Political Sci Rev. 10(4):23–34.

- Dias SM, Alves FCG 2008, Integration of the informal recycling sector in solid waste management in Brazil. Study Prepared For GIZ’s Sector Project “Promotion Of Concepts For Pro-Poor And Environmentally Friendly Closed-Loop Approaches In Solid Waste Management.

- Downey L, Strife S. 2010. Inequality, democracy, and the environment. Organiz Environ. 23:155–188.

- Dryzek JS. 2000. Deliberative democracy and beyond: liberals, critics, contestations. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press.

- Dryzek JS. 2012. Foundations and frontiers of deliberative governance. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Dryzek JS, Stevenson H. 2011. Global democracy and earth system governance. Ecol Econ. 70(11):1865–1874.

- Dryzek JSStevenson H. 2011. Global democracy and earth system governance. Ecological Economics. 70(11):1865–1874.

- Eckersley R. 2004. The green state: rethinking democracy and sovereignty. Cambridge. (MA): MIT Press.

- EPTC (Empresa Pública de Transporte e Circulação). 2011. Total de Passageiros. [accessed 2017 Aug 22]. http://lproweb.procempa.com.br/pmpa/prefpoa/eptc/usu_doc/total_passageiros_transportados_portipo_porano_mar2011.pdf

- Fedozzi L, Furtado A, Bassani VDS, Macedo CEG, Parenza CT, Cruz M. 2013. Orçamento Participativo de Porto Alegre: perfil, avaliação e percepções do público participante. Porto Alegre: Gráfica e Editora Hartmnn.

- Fishkin JS. 2011. When the people speak: deliberative democracy and public consultation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Fuentes-Nieva R, Galasso N. 2014. Working for the few: political capture and economic inequality. Oxford: Oxfam.

- Fung A. 2011. Reinventing democracy in Latin America. Perspect. Politics. 9:857–871.

- Fung A, Wright EO, editors. 2003. Deepening democracy: institutional innovations in empowered participatory governance. The Real Utopias Project IV. London: Verso.

- Gonçalves S. 2014. The effects of participatory budgeting on municipal expenditures and infant mortality in Brazil. World Dev. 53:94–110.

- Gret M, Sintomer Y. 2005. The Porto Alegre experiment: learning lessons for better democracy. Translated by Wright S. London/New York: Zed Books.

- Hall D, Lobina E, Viero OM, Maltz H. 2002. Water in Porto Alegre, Brazil. In: A Psiru and DMAE paper for WSSD. Porto Alegre: DMAE and PSI.

- Harvey D. 2008. The right to the city. New Left Rev. 53:23–40.

- Harvey D. 2012. Rebel cities: from the right to the city to the urban revolution. London: Verso Books.

- Hilmer JD. 2010. The state of participatory democratic theory. New Political Sci. 32(1):43–63.

- IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica). 2010. Censo demografico 2010. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE.

- Inter-America Development Bank (IADB). 2005. Assessment of participatory budgeting in Brazil. Washington (DC): IADB.

- Lefebvre H. 1968. Le droit à la ville. Paris: Anthropos.

- Marquetti A. 2002. O Orçamento Participativo como uma política redistributiva em Porto Alegre. 1º Encontro de Economia Gaúcha, 16–17 May 2002. Porto Alegre: FEE.

- Marquetti A, Schonerwald Da Silva CE, Campbell A. 2012. Participatory economic democracy in action participatory budgeting in Porto Alegre, 1989–2004. Rev Radical Political Econ. 44(1):62–81.

- Mason M. 1999. Environmental democracy. London: Earthscan.

- Meadows DH, Meadows DL, Randers J. 1992. Beyond the limits: global collapse or a sustainable future. London: Earthscan.

- Melgar TR. 2014. A time of closure? Participatory budgeting in Porto Alegre, Brazil, after the workers’ party era. J Lat Am Stud. 46(1):121–149.

- Menegat R. 2002. Participatory democracy and sustainable development: integrated urban environmental management in Porto Alegre. Brazil Environ Urban. 4(2):181–206.

- Molina Molina J. 2011. Los presupuestos participativos un modelo para priorizar objetivos y gestionar eficientemente en la Administración Local. Pamplona: Editorial Aranzadi.

- Núñez T. 2018. Porto Alegre, from a role model to a crisis. In: Dias N, editor. Hope for democracy: 25 years of participatory budgeting worldwide. Porto Alegre: Epopeia Records and Oficina coordination; ; p. 517–536.

- ObservaPoA. 2017. Porto Alegre Em Analise, Sistema de gestão e análise de indicadores. [accessed 2017 Aug 29]. http://portoalegreemanalise.procempa.com.br/.

- PMPA (Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre). 2002. Plano de Investimentos e Serviços – 2002. Porto Alegre: PMPA CRC, GAPLAN.

- PMPA (Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre). 2017. A Cidade. [accessed 2017 Aug 29] http://www2.portoalegre.rs.gov.br/turismo/default.php?p_secao=256.

- Rennó L, Souza A. 2012. A metamorfose do orçamento participativo. Revista de Sociologia e Política. 20(41):235.

- Rockström J, Steffen W, Noone K, Å P, Chapin III FS, Lambin E, Lenton T, Scheffer M, Folke C, Schellnhuber HJ, et al. 2009. Planetary boundaries: exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecol Soc. 14:2.

- Satterthwaite D. 2003. The links between poverty and the environment in urban areas of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Ann Am Acad Political Soc Sci. 590(1):73–92.

- Schlosberg D. 2007. Defining environmental justice: theories, movements and nature. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press.

- Schouten G, Leroy P, Glasbergen P. 2012. On the deliberative capacity of private multi-stakeholder governance: the roundtables on responsible soy and sustainable palm oil. Ecol Econ. 83:42–50.

- Silveira Campos P, Silveira N. 2015. Orçamento participativo de Porto Alegre: 25 anos. Porto Alegre: Editora da Cidade/Gráfica Expresso.

- Smith G. 2003. Deliberative democracy and the environment. London and New York: Routledge.

- Souza A. 2010. A metamorfose do orçamento participativo: uma analise da transição politica em Porto Alegre (1990-2009). [master’s thesis] Brasilia: Universidade de Brasília, instituto de Ciencias Sociais.

- Steenbergen MR, Bächtiger A, Spörndli M, Steiner J. 2003. Measuring political deliberation: a discourse quality index. Comp Eu Politics. 1(1):21–48.

- Touchton M, Wampler B. 2014. Improving social well-being through new democratic institutions. Comp Polit Stud. 47(10):1442–1469.

- Vallejo Silva T, Calisto Friant M. 2015. Ecuador’s Yasuní-ITT initiative for mitigating the impact of climate change. Environ Plann Law J. 32:278–293.

- von Weizsäcker EU, Wijkman A. 2018. Come on!: capitalism, short-termism, population and the destruction of the planet. New York: Springer.

- Wampler B. 2012. Entering the state: civil society activism and participatory governance in Brazil. Polit Stud. 60:341–362.

- Waters CN, Zalasiewicz J, Summerhayes C, Barnosky AD, Poirier C, Gałuszka A, Cearreta A, Edgeworth M, Ellis EC, Ellis M, et al. 2016. The anthropocene is functionally and stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene. Science. 351:6269.

- WB (World Bank). 2008. Brazil: toward a more inclusive and effective participatory budget in Porto Alegre. Washington (DC): World Bank. Report No. 40144-BR. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/8042