?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This research distinguishes among the business interest groups and community factors associated with green building policies in cities and towns to examine a specific type of business interest group—construction industry associations—involved in the green building policy arena. Rare event logit modeling is used to estimate the association of “traditional” and “green” industry groups with green building policy while controlling for various characteristics of cities. It is no surprise that the results indicate that the presence of green industry association members increases the likelihood of the presence of a green building policy. However, traditional groups do not limit the probability of a green building policy, as was expected. Community characteristics show that general revenue, population, household income, and education are all higher in cities with modern building codes, and that the average cost of energy is lower in cities with modern building codes.

Green building policies, such as building certifications, prescriptive checklists, permit fee reductions and green building codes, have been diffusing throughout the United States continuously since the 1990s, when the U.S. Green Building Council launched the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program. Although it was originally intended to be a voluntary program, LEED certification is now required by many state and local governments for government, commercial, industrial, and residential buildings within their jurisdiction. The widespread adoption of these green building policies provides an opportunity to better understand (1) how business interest groups that are known to be influential in this policy arena at national and state levels of government are associated with green building policies at the local levels, and (2) if there are differences in associations depending on the target population of the policies, i.e., whether LEED requirements apply to private or public buildings.Footnote1

Adoption of green building varies across real estate markets and building types. The National Green Building Adoption Index that is published each year by real estate company CBRE, shows that almost 40% of office building square footage in 30 major real estate markets are certified to green or energy efficiency standards, up from 5% in 2005 indicating the growth in green buildings that has occurred over the past 15 years (CBRE, Citation2017). While this is impressive growth, it equates to only 4.7% of total physical buildings in these markets, suggesting that large office buildings in major real estate markets are more likely to be built to green standards than small buildings, industrial facilities, or buildings in small cities and towns with relatively non-competitive real estate markets (Gripne et al., Citation2012).

The cost to build green is typically offset by the market premium of the LEED certification. Research shows that building to green standards for office buildings costs 2–17% more compared to conventional office buildings depending on the certification level, credit selection, product and design choices, and other factors (Ross et al., Citation2007; USGBC, Citation2015; Zuo & Zhao, Citation2014). Green buildings command rental and sales price premiums of 3–17% and 13–26%, respectively (Gripne et al., Citation2012). Costs and returns on investments vary widely across the country, and in some real estate markets returns on investments have not been quantifiable due to limited data availability about construction costs and real estate market prices (Gripne et al., Citation2012). Therefore, many construction industry professionals are hesitant to embrace green building as a construction practice, but early adopters may benefit from new market demand (Circo, Citation2007; Fuerst et al., Citation2014; May & Koski, Citation2007).

The rapid green building market growth for some building types (e.g., office buildings) and slow progress for other types (e.g., industrial) as well as variations in costs and benefits lends to uncertainty in the marketplace and green building policy arena. This provides an ideal case selection to examine the roles and motivations of business interest groups at the local level, an understudied segment of the population in urban environmental policy research.

This paper begins with an exploration of theories on why various types of interest groups are expected to support or oppose green building policies that apply to public and private buildings. The theories lead into three hypotheses regarding the role of interest group association members in local green building standards. Next, I provide background information on the LEED program. I use rare event logit regression modeling to understand how two types of interest groups—traditional builders and green builders—correlate with green building policies while controlling for political, socioeconomic and problem severity factors. I find that the green building interest group is associated with increases in green building policies whereas the traditional building interest group does not have a statistically significant association.

Theory and Hypotheses

Regulations for green buildings isolates a highly technical, low public salience policy option, tending to engage technical building experts with minimal news media or public attention to the issue (Koski, Citation2010). Green building policies typically specify if the policy applies to public buildings only, or to both public and private buildings. These policies can require building certifications or prescriptive checklists that require minimum building standards; offer expedited permitting by the government’s building and planning departments when green building requirements are fulfilled by the builder; or provide financial incentives such as reduced permit fees. More recently, green building codes detailing prescriptive requirements for construction activity have been developed. Mostly these codes have been adopted in such a way that participation is voluntary rather than mandatory, as is more commonly required with other building codes.

This work examines two types of industry interest groups—traditional industry and green building association members—within the same industry. I define “green” industry association members as having the desire for construction and land development that enables fewer negative externalities than conventional buildings in terms of carbon emissions, auto-dependency and excess water consumption, for example, and more positive externalities such as better indoor air quality and reduced operating costs for building owners (Schindler, Citation2010). The green industry association members are associated with contemporary perspectives on corporate responsibility where business may act in ecological interests motivated by stakeholder pressures, as well as ethical motivations and a desire for new economic opportunity (Bansal & Roth, Citation2000). Traditional industry association members represent the classical economic view of the firm as a profit maximizer (March, Citation1962), and are associated with a motivation by profits for personal gains and less likely to internalize incremental costs associated with green building. Members in either organization include professionals such as builders, architects, designers, and product suppliers.

Drawing from literature on economics, policy studies, and urban sustainability, assorted factors help explain why various types of business interest groups are expected to support green building policies in some cases and oppose green building in other cases. Overall, some distinguishing factors include:

whether the policy applies to public buildings only or also includes privately owned buildings;

if it is voluntary (e.g., in exchange for permit fee reductions or other financial incentives) or mandatory (e.g., must comply with certification requirements or prescriptive green building codes); and

the extent to which the industry group is expected to gain a market advantage from the policy adoption.

In extent research, empirical results on the effects of interest groups are widely varied. Some of the variation is explained by the aforementioned factors in addition to the level of government and how the interest group variable is constructed.

The extent research that explores business interest effects on green and sustainability policy adoption often does not recognize the importance of the distinction in the policy’s target population, and how the target population is expected to mediate the effects. Research that uses privately owned buildings for case selection does not necessarily generalize to policies that apply to public buildings because of the differences in who pays the incremental costs to build to higher standards. Whether the target population of the policy is public or privately owned buildings is often not overtly recognized as a critical emphasis or isolated in statistical modeling, even though the scope of a policy has long been acknowledged as a theoretical determinant in policy adoption (Schattschneider, Citation1975).

The works of May and Koski (Citation2007) and Koski and Lee (Citation2014) are among the exceptions of literature that deeply considers how the target population matters in the urban sustainability literature. May and Koski (Citation2007) provide the insight that “[t]he seemingly benign politics of state adoption of green building requirements defies the conventional depiction of environmental policymaking as pitting industry against environmental interests,” explaining that “green building requirements are aimed at practices of public agencies whereas the environmental regulatory focus is typically the behavior of firms” (p. 50). From this line of research, we can expect construction industry groups on the whole to support green building mandates that apply to public buildings.

However, May and Koski (Citation2007) did not find that homebuilders support environmental policies for public buildings at the state level. They found that the presence of interest groups had significant effects on the adoption of green building mandates for public buildings, with three times greater negative influence by oppositional groups such as homebuilders (p. 59). Interest group effects are expected to be more significant at the state and national levels than local levels because interest groups are generally more active at higher levels of government particularly with paid professionals lobbying for their group’s policy position (Berry, Citation2010).

Typically, urban sustainability research use proxies for interest group presence where the value of the manufacturing sector (e.g., Koski & Lee, Citation2014), counts of manufacturing establishments (e.g., Sharp et al., Citation2011), or combined measures of Chamber of Commerce members and developers represents industry group strength (e.g., Daley et al. Citation2013; Schumaker, Citation2013). While this approach is appropriate when interest groups are control variables and not the focal predictor, it neglects the variation of interest groups that are active in specialized issue domains. Consequently, estimates of interest groups effects on sustainability policy adoption are widely varied. For example, in a study on local-level green building (buildings, not policies), Lee and Koski (Citation2012) found statistically significant effects of manufacturing presence (as a proxy for industry interests) on counts of green buildings in cities (p. 616). In studies on broader sustainability policies, Berry and Portney (Citation2013) did not find statistically significant effects of interest groups on local-level sustainability policies that apply to privately owned buildings. Contrarily, Hawkins and Wang (Citation2013) find that involvement of businesses in policy adoption processes has a statistically significant positive effect on the number of sustainability policies adopted by cities. Empirical results are somewhat inconclusive on the effects of business interest groups on local green building policy adoption.

Building for a New Economy (Support for Green Building Policies)

Green building policies for public buildings have particular impacts on the construction industry. In the “political market” (Feiock et al., Citation2008), business interest groups may seek green building policy change for economic gain and support governments’ decisions to adopt green building policies, particularly when using governments’ own buildings (Hawkins & Wang, Citation2013, p. 65). Interest groups representing green construction may view governments’ willingness to construct buildings to green standards as an opportunity to shift the market and increase demand for green construction in the private sector (Berry & Wilcox, Citation2015, pp. 28–31; Volokh, Citation2003).

Green builders can gain market advantages by participating in energy efficient and green building policy processes. Industry actors can participate in a voluntary way, offering to help shape the guidelines (May & Koski, Citation2007) and bidding for contracts with the government as a way to learn new green building practices before the demand for green building increases. Firms experience the benefits of participating in advancing energy and green building policies as a way to differentiate themselves in the marketplace as the policies evolve to start regulating privately owned buildings (Cotton, Citation2012) or strive to marry economic development and environmental protection such as in Smart Growth policies (Portney, Citation2013). Moreover, firms generally want their stakeholders (clients and investors) to view their business as supportive of the environment and public interests (Bansal & Roth, Citation2000; Darnall et al., Citation2010).

H1 (Supportive): Higher numbers of green construction interest group members per capita are likely to increase the probability of a green building mandates.

Building as Usual (Opposition to Green Building Policies)

Drawing from the economic and political theory of the firm (March, Citation1962), business interest groups seek to maximize their profits in the short and long runs and therefore oppose public policies that impose higher cost burdens (Coase, Citation1937; March, Citation1962; Spulber, Citation2007). In classical economics, profit maximization is determined by the production function, cost function and price (March, Citation1962, p. 668). New green building regulations increase costs while price movement remains uncertain. It is unknown to builders whether the customer will pay a higher price for the building. Following March’s (Citation1962) perception of business as a political coalition, firms are expected to form interest groups towards the goal of conflict resolution, and their conflict resolution strategy is expected to be stable and meaningful. The stable and meaningful approach to conflict resolution for traditional construction associations when it comes to regulations on buildings has historically been a long-standing policy position of anti-regulation, tolerating voluntary involvement in green building but not mandatory prescriptive requirements. The business sector generally prefers less government regulation and more voluntary programs, such as financial incentives (Kamieniecki, Citation2006).

Business interest groups may oppose green building policies, even those that apply only to government buildings, for at least two reasons. First, the policy signals a market shift opening doors to subsequent regulation requiring construction practices that can be costly and therefore disadvantageous to maximizing profits. Many industry actors view regulations on public facilities as a slippery slope for mandates on private buildings (Bae, Citation2014; Levmore, Citation2010; May & Koski, Citation2007, p. 53). Any adoption of green building policies and programs may be viewed as an endorsement of green building ideals, paving the way for subsequent mandatory regulation that the traditional construction industry would ultimately oppose (Levmore, Citation2010). Further, market actors may negotiate with policymakers ta the stance that additional regulations are unwarranted because the industry professionals have already integrated green building and energy efficient construction practices into their businesses under a voluntary program (Kamieniecki, Citation2006). Second, the policy change may grow the market for their competitors who specialize in green construction (Levmore, Citation2010). In a finite construction industry, the total capital available for construction is limited. Construction industry professionals who do not expand into green building markets could be crowded out by professionals with modernized, green building skill sets (Levmore, Citation2010).

H2 (Oppositional): Higher numbers of traditional construction interest group members per capita are likely to limit the probability of green building mandates.

Background on the LEED Program

The LEED green building program was developed in 2000 by the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization founded in 1993. Continually developed through a consensus-based decision-ma process (USGBC, Citation2017c), the program details prescriptive requirements and environmental performance standards for the design and construction of buildings and development projects, and more recently expanded to provide standards for neighborhoods and cities. Initiated in the United States, LEED is used in over 160 countries with over 30,000 certified projects worldwide (Shutters & Tufts, 2016). While the program was originally used voluntarily by construction industry professionals, it has increasingly been adopted by governments as a mandatory policy (Schindler, Citation2010).

The LEED program has four levels of certification: Certified, Silver, Gold and Platinum (USGBC, Citation2017c). Building professionals can apply for certification based on the total number of points that the project attains, in addition to meeting minimum program requirements such as project size requirements. Points can be achieved in the areas of energy or water efficiency; site and land use development; location and transportation; indoor air quality; and sustainable materials and resources. To receive project certification, the project team must apply to the USGBC with the appropriate project documentation and registration and certification fees. Fees associated with the program vary by LEED program type and project size with registration fees starting at $1,200 and minimum fees for building design and construction certification between $2,850 and $27,500 depending on project size (USGBC, Citation2019). The USGBC Trademark Policy allows project owners to market their buildings as “LEED registered” or “LEED certified” based on if the building has only been registered or actually completed the certification process (USGBC, Citation2018c).

Research Design

Case Selection and Dependent Variable

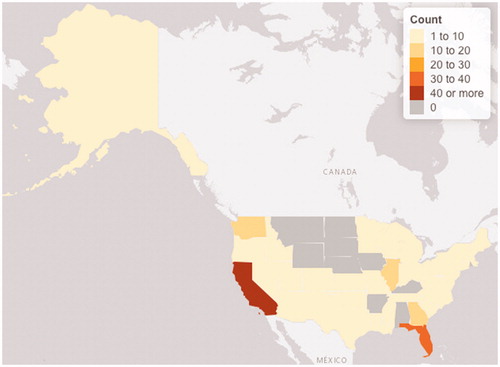

This study focuses on policies that require LEED certifications for city-level public and privately-owned commercial buildings, not market incentives such as expedited permitting or fee reductions. Only LEED certification policies are examined because industry groups are not expected to oppose policies for financial incentives or goal-setting, as those types of policies do not impose cost burdens to industry. The dependent variable is dichotomously coded for whether or not a city has adopted a certification policy. The source of this data comes from the Public Policy Library of green building requirements for cities, counties, states and federal government buildings maintained by the USGBC beginning in 2017 (USGBC, Citation2017b, Citation2018b). Two hundred and seventy-nine cities have a LEED certification policy for public and/or privately owned commercial buildings, including schools (USGBC, Citation2018b; ). California has the most local level green building policies, many of which are local adoptions of the state-level California Green Building Code to replace existing municipal requirements or amend the state code with local requirements.

Focal Independent Variables

shows the variables and descriptions for all data sources. The focal independent variables are counts of “traditional” and “green” construction industry interest group members normalized by the total number of construction workers in the city. The “traditional” interest group variable is comprised of members of the Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA). The “green” interest group variable is constructed from the publicly-available USGBC member list (USGBC, Citation2018a). There are 5,648 BOMA members in 1,480 communities and 50,336 USGBC members in 6,301 communities. To give a sense of how construction professionals in a community relate to the total population, in New York City and Kansas City, approximately 2% of the total population, or 196,634 and 11,473 people, respectively, works in the construction industry using American Community Survey estimations. Nationwide, BOMA and USGBC members represent a mean of 0.2 and 0.5% of the construction industry, respectively. New York City has 570 BOMA members and 2,098 USGBC members. Kansas City, MO has 98 BOMA members and 285 USGBC members.

Table 1. Variables, descriptions, and data sources for green building models.

The Washington, D.C.-based USGBC has a decentralized advocacy model where regional and local chapters have members, as well as paid staff, who provide local technical support and professional green building services and advocate for green building, which are core benefits of member association (Koski, Citation2010, p. 102; USGBC, Citation2019). USGBC members represent a variety of professions and sectors, including product manufacturers; contractors and builders; corporate and retail; education and research institutions; environmental and other 501(c)(3) nonprofit organizations; governments; finance and insurance; professional firms; trade associations; real estate professionals; and energy service providers (USGBC, Citation2017a). Members are granted access to an extensive library of resources, educational courses, and can market themselves in the membership directory (USGBC, Citation2019).

Green building policy advocacy is a core activity of local chapters, and many Chapters have historically organized “State Advocacy Day” at their state capitol as an effort to educate and persuade state legislators to consider green building legislation (e.g., USGBC Florida Chapter, Citation2020; USGBC Texas Chapter, Citation2019; USGBC, Citationn.d). Considerable policy advocacy also occurs at the city and county levels (e.g., USGBC Florida Chapter, Citation2020). The USGBC explains:

USGBC engages with governments at all levels to help them leverage LEED and green building strategies to meet their goal—whether that be reducing climate and environmental impacts, achieving high performing and resilient buildings, or saving money. Through technical assistance, testimony, written comments, sign-on letters, direct advocacy, and expert articles and resources, we are working every day to advance green buildings through policy… USGBC’s advocacy activities focus on green building certification policies including leadership by example for public buildings and incentives to drive green building in the private sector. (USGBC, Citation2020)

A recent business news article highlights Colorado as ran highest in the nation for LEED green buildings, noting contributions of the USGBC community in helping to achieve these policy goals (ColoradoBiz, Citation2020).

BOMA is also an organization with local chapters. As clearly stated in BOMA’s policy positions statements,

BOMA International does not support the adoption and implementation of green/sustainable building codes intended to apply to all newly constructed buildings, or to all tenant finish-out, additions and major renovations to existing buildings… (BOMA, Citation2018a)

Based on their explicit policy position, it is expected that BOMA’s presence in a community will limit the likelihood of pushing a green building policy agenda forward. To gather counts of BOMA members per city, I used the Python programming language and the PDFMiner library to convert the 2018 BOMA Member Directory PDF to plain text. Using Python, I found all city and state combinations in the text, and aggregated the counts of members in each community (BOMA, 2018; Shinyama, Citation2016).

Ideally it would be possible to construct a pooled cross-sectional dataset with counts of all construction sector interest group members for each city in each year, but I was limited by time and resource constraints for data collection. Consequently, only the most dominant interest groups in commercial building policy processes—BOMA and USGBC—are represented in this research.

Political and community characteristics (control variables)

Various forms of government, such as mayor-council or council-manager structures, are expected to influence several aspects of policy processes such as interest group engagement during agenda-setting and policy adoption (e.g., Bae & Feiock, Citation2013; Hawkins et al., Citation2016; Sharp et al., Citation2011). Mayor-council forms of government are expected to be susceptible to the influences of dominant interest groups because these executive arrangements are associated with an emphasis on short-term political gains and political alignment with powerful groups within the city. In contrast, council-manager forms of government tend to be more tactically focused on policy implementation and thus more responsive to technical experts. Council-manager government types are thought to have a longer-term outlook with the primary interest of maximizing operational efficiency and ease of policy implementation. They are more likely to host stakeholder engagement activities so that a diverse interest groups can help to shape public policies (Bae & Feiock, Citation2013; Daley et al., Citation2013; Krause & Douglas, Citation2005). The political institutions variable is dichotomously coded for mayor-council (1) or other form of government such as council-manager (0) using data from the International City Management Association (ICMA) Municipal Yearbook and collected directly from city websites where data is not found in the yearbook.

Climate commitment

In addition to the institutional structure, the city’s commitment to climate protection is likely to influence the adoption of green building policies. As it relates specifically to climate protection, a combined measure of two indicators are used to construct the climate commitment variable: a dummy code if the city’s mayor is a signatory of the Mayor’s Climate Protection Agreement or if the city is a member of ICLEI Local Governments for Sustainability (1), otherwise 0. Additionally, California is included as a dummy variable in these models because it has been a leader in green building policy advancement with a statewide green building code that cities adopt locally. Almost 30% of localities with LEED certification policies in this study are in California.

Government and industry capacity

In most cities, the city planning and building department relies on general revenue and/or development permit fees to fund government staff to implement buildings policies. Thus, general revenue per capita for each city is used as a measure of government capacity for adopting new building policies, as building permit fee data is not available. Overall, cities with struggling economies may have less demand for mandatory green building requirements than a thriving city that is working to manage excessive growth. Further, cities need funding from general revenue or permit fees to manage the transaction costs, such as training industry members on new building practices, associated with new green building regulations (Nelson, Citation2012).

City characteristics and socioeconomic conditions: population, income and education

Cities with larger populations have been found to be more likely to adopt LEED policies due to having more resources, such as government staff to implement the policy (Cidell & Cope, Citation2014, p. 1774; Kontokosta, Citation2011, p. 75). The size of the construction industry highly correlates with population (0.95), so population logged is included in the models to retain consistency with many other policy adoption studies. Further, counts of housing units highly correlates with population (0.99) and was explored but is not used in these models. People with higher education tend to have higher incomes, which in turn typically results in a higher tax base to support government initiatives. The percentage of the population with a bachelor’s degree or higher as well as median household income for each city are included in the model.

Problem severity

Cities with very little building activity may be less likely to adopt modern building policies than cities with more construction activity. The median age of housing in a city is used as a proxy to represent the building stock in the models. Older median housing age is associated with less current building activity and a newer median housing age correlates with higher levels of recent construction activity. Further, the average electricity cost in the county is also used as a proxy for problem severity, as places with more expensive energy are likely to seek buildings policies that reduce energy usage to lessen the economic burden of building operations. Where county-level electricity costs is not available, I use the average electricity cost for the state.

I collected all Census variables using the Python program, CenPy, which provides an API integration for retrieving Census data tables into Python for data processing, such as formatting and joining tables (Wolf, Citation2018). I used the Social Explorer Data Dictionary to find the unique identifiers for the American Community Survey data tables (Social Explorer, Citation2019). I stored the data in an SQLite database that is easily loadable as a .db file into the R program for statistical computing (Hipp et al., Citation2015; R Development Core Team, Citation2019).

Rare Event Logit Model and Discussion on Modeling Results

I use rare event logit modeling to estimate the probability of LEED certification policy adoption given differences in the presence of trade association members across cities (King & Zeng, Citation2001). This modeling technique resamples the data to run regression simulations with all values of policy adopters in each simulation. I selected this method because of the sparse number of cities that have adopted LEED certification policies (277 cities, or 1.4% of cities in the sample; ). In order to understand patterns in adoption, I use a dataset of permit issuing places for information on non-adopters. Of the 20,100 permit issuing places in the United States, 19,579 places have sufficient data to be included in the statistical models. I use the Zelig library ReLogit class in the R statistical computing program for modeling.Footnote2

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for green building policy adoption models.

For greatest explanatory power, I developed a full model that includes cities with LEED certification requirements for privately and publicly owned buildings. Next, I explore how the effects shift depending on whether the policy applies to privately owned buildings or publicly owned buildings by modeling these two population subsets separately. Each model has 19,579 cities that are bootstrapped or resampled using the rare event logit method. The first model has 277 cities that mandated LEED certification for any building type. The second model has 104 cities that adopted LEED certification mandates for public buildings. The third model has 125 adopting cities with mandates for privately owned commercial buildings (). The full model has the most explanatory power with an of 0.13. The public and commercial models have an

of 0.07 and 0.06, respectively.

Table 3. Rare event logit results from modeling green building policy adoption.

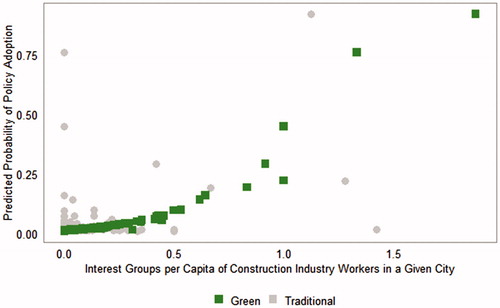

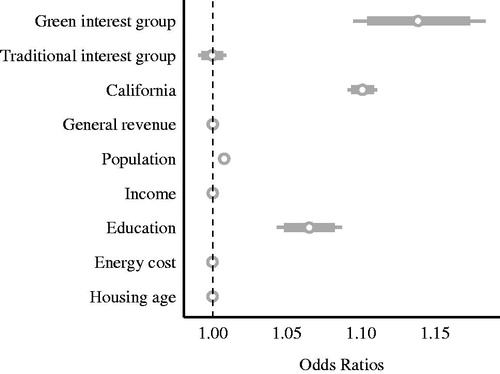

Across all models, green interest group presence matters for LEED policy adoption. It is not surprising that green interest groups—operationalized by counts of USGBC members per 1000 people—is important since the USGBC is the creator of the LEED program and has local association members advocating for policy adoption. This reflects the openness of local political systems where local business interest groups can effectively influence government policy. It also shows how powerful an industry association can be when they develop a voluntary program that gains such widespread attention and legitimacy that governments begin to adopt it as a mandatory requirement. Holding all other independent variables at their means, a one standard deviation increase in green interest group presence increases the city’s odds of LEED certification policy adoption by 14% in the full model and 4 to 6% in the public and commercial models ().

Table 4. Odds ratios for green building policy adoption models.

shows a less linear relationship between green building policy adoption and the traditional construction industry compared to the green construction industry. The traditional interest group is not significant, and the effects are very small (−0.001 or less). This could be explained as traditional builders not viewing green building construction as their target market, and LEED policies being more heavily targeted at public buildings. The commercial building model attempts to isolate policies that regulate privately owned commercial buildings, but these policies could be relatively weak. Builders may be able to easily meet the LEED-certified requirements in some markets, depending on state and local building codes. Rebate programs for energy and water efficiency and urban design of the cities could make LEED credits such as proximity to public transit more easily attainable.

As expected, the political institutional structure and climate commitment are consistent with urban policy theory. Cities with mayor-council forms of governments are more likely to have green building policies. Not surprisingly, the indicator with the most impact is whether the city has demonstrated a commitment to climate protection as a signatory of the Mayor’s Climate Protection Agreement or a member of ICLEI. Cities are 13% more likely to adopt LEED certification requirements when they have committed to climate protection (). Similarly, given the strong state commitment to green building, cities within California are more likely to adopt LEED certification requirements.

While population is significant across the models, the odds ratio of 1 signifies that there is not a substantive difference between cities that have or do not have LEED certification policies on this characteristic. The varied population sizes of cities adopting LEED requirements could be explained by the outsourced nature of LEED where a third party—the USGBC—and their members are doing most of the program management and document preparation for the program, alleviating the administrative burden to the government. This could also be why general revenue is not a significant indicator of policy adoption.

I had expected that communities with higher educational attainment and income would be more likely to have LEED certification policies. This expectation is met for education but not income. An increase of one standard deviation in education increases the city’s odds of policy adoption by 7%. Income is not significant (which is not surprising because it is a measure of household income), whereas LEED building policies typically affect commercial real estate, not residential. I had also expected higher energy costs and newer building stocks to be more likely to increase the odds of policy adoption. While energy cost and housing age have negative coefficients, the odds ratios are 1, indicating that there is no significant difference between adopting and non-adopting cities.

As illustrated by the statistical modeling in this study, the ability to identify distinctive motivations within a type of interest group can help explain how distinctive segments within a business interest affect urban policymaking differently—as opposed to than treating business interests as the same across the sector. The traditional industry association had a negative effect on LEED policy adoption while the green industry group had a positive effect, similar to findings in May and Koski (Citation2007). These groups both represent the construction industry, yet have very different effects on LEED certification policy adoption.

In line with the microeconomic theory that firms are profit maximizers and will seek market differentiation to secure profits, green industry association members are better positioned to absorb the new market for green building that is grown by city policy adoption than their traditional peers, who have not distinguished themselves in green building expertise. The green industry association members may be ideologically motivated, realizing that firms can obtain substantial profits while also supporting environmental protection, or they may just be strategic profit maximizers motivated to get a share of a new untapped market. Either way, this study shows that their presence increases the likelihood of green building policy adoption, unlike their traditional peers.

Regarding effects of the control variables, many were statistically significant but had odds ratios of 1, indicating no apparent difference between cities with or without LEED certification policies. LEED certifications are most common for commercial buildings, particularly office buildings, so demographic variables might be representing latent concepts such as urban development patterns involving concentrations of office parks and surrounding residential developments, or diverse urban core development patterns in these cities and towns. Controlling for city characteristics that characterize local commercial real estate markets, such as number of office buildings in the city or the competitiveness of the local office rental market, might provide a better fit for modeling LEED policies, but this data is not readily available unless purchased from CBRE, a company that sells commercial real estate data for local markets.

A limitation to this study is that it explores only two industry associations among many groups that are involved in influencing building-related policies, and the study cannot discern cross-membership between the two groups. I attempted to select the most distinctive and influential groups, but without surveying government staff and political leaders or counting testimonies from public hearings it is difficult to validate the selection of the two groups. The USGBC is an obvious choice because it is the organization that developed LEED. BOMA is known to be highly influential and oppositional in building-related policy adoption processes, according to expert knowledge, and their explicit oppositional policy statement is cited earlier in this paper. Other groups are also influential. An article on why some industry groups are trying to ban green building standards (Badger, Citation2013) points to the American High-Performance Buildings Coalition (AHPBC) as an industry-led coalition opposing LEED (AHPBC, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). The 42 coalition members listed on the AHPBC website are product-oriented councils and associations, each with their own membership populations. The Coalition supports “reasonable performance based policies” and “voluntary adoption,” similar to BOMA’s policy position statement. A subsequent study could model the sums of members in the 42 industry groups for an estimation of their effects on mandatory green building policy adoption at the local level.

Conclusion

The green building policy arena allows for a careful examination of the role that business interests play in the adoption and implementation of sustainability policies at the local level. This research segments interest groups that represent a major industry (construction) by isolating traditional and green building interests in order to examine interest group behavior in sustainability policy in more detail. Contributing to sustainability research, isolating business interest groups into distinct segments is conducive to explaining effects on urban policymaking with greater nuance than the more commonly taken empirical approach that treats business interest groups as one unit.

In this study, the presence of green building interest group members matter to LEED policies, increasing the odds of a LEED policy by up to 14%, whereas the traditional building interest group had very little influence. Because USGBC is expected thereby to gain a market advantage, it is not surprising that the industry group supports LEED policies. It is, however, surprising that the presence of traditional construction industry group members does not have a significant negative effect on the presence of LEED certification policies, because private industry is expected to reject mandatory regulations due to potential loss of profits and a perceived advantage of such policy benefiting their competitors.

The policy’s target population—public or commercial buildings—is not a distinguishing factor in this study, but theoretically the policy scope is expected to be an important consideration because construction industry groups are expected to be more likely to support policies that regulate public buildings rather than private buildings, due to who pays the incremental cost for green construction. More research is needed that isolates policies that apply to public and commercial buildings to determine the conditions under which the policy scope matters.

A city’s commitment to climate protection increases the odds of a LEED policy by 13%, indicating the strong relationship between urban sustainability goals and green building policy strategies. This study deviates from broad sustainability research by examining the types of interest groups that are active in the green building sector of sustainability. This is an important approach because distinct interest groups participate in each aspect of sustainability; treating sustainability as a broad concept misses the nuances of each policy domain within it. As the urban sustainability field grows, more acutely examining specific sectors will facilitate a better urban sustainability policy processes.

Notes

1 Public facilities in cities typically include convention centers, courthouses, fire stations, museums, warehouses, offices, parking garages, police stations, recreation facilities, schools, wastewater treatment plants (City of Kansas City, MO, 2017).

2 Zelig Version 5.1.6 is available at http://zeligproject.org/.

References

- American High-Performance Buildings Coalition. (2018a). Coalition members. Retrieved October 18, 2018, from https://www.betterbuildingstandards.com/coalition-members/.

- American High-Performance Buildings Coalition. (2018b). About AHPBC. Retrieved October 18, 2018, from https://www.betterbuildingstandards.com/about/.

- Badger, E. (2013). Why are some states trying to ban LEED green building standards. Atlantic Cities, 28. Retrieved October 18, 2018 from https://www.citylab.com/design/2013/08/why-are-some-states-trying-ban-leed-green-building-standards/6691/.

- Bae, H. (2014). Voluntary disclosure of environmental performance: Do publicly and privately owned organizations face different incentives/disincentives? American Review of Public Administration, 44(4), 459–476.

- Bae, J., & Feiock, R. (2013). Forms of government and climate change policies in US cities. Urban Studies, 50(4), 776–788.

- Bansal, P., & Roth, K. (2000). Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Academy of management journal, 43(4), 717–736.

- Berry, J. M. (2010). Urban interest groups. In Maisel, L. S., & Berry, J. M. (Eds.) The Oxford handbook of American political parties and interest groups (pp. 502–518). Oxford University Press: Oxford, England.

- Berry, J. M., & Portney, K. E. (2013). Sustainability and interest group participation in city politics. Sustainability, 5(5), 2077–2097.

- Berry, J. M., & Wilcox, C. (2015). The interest group society. Routledge: London, UK.

- Building Owners and Managers Association. (2018a). Energy efficiency and green building codes: Policy positions. Retrieved February 17, 2018 from http://www.boma.org/Codes/Pages/Energy-Efficiency-and-Green-Building-Codes.aspx.

- Building Owners and Managers Association. (2018b). BOMA International Member Directory 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018 from http://www.naylornetwork.com/bom-nxt/

- CBRE. (2017). 2017 National green building adoption index. Retrieved March 13, 2018 from https://www.cbre.com/about/corporate-responsibility/environmental-sustainability/real-green-research-challenge.

- Cidell, J. (2015). Performing leadership: Municipal green building policies and the city as role model. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 33(3), 566–579.

- Cidell, J., & Cope, M. A. (2014). Factors explaining the adoption and impact of LEED-based green building policies at the municipal level. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 57(12), 1763–1781.

- Circo, C. J. (2007). Using mandates and incentives to promote sustainable construction and green building projects in the private sector: A call for more state land use policy initiatives. Penn State Law Review, 112(3), 731–782.

- Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405.

- ColoradoBiz. (2020, January 23). Colorado ranks first in the US for LEED Green Building. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://www.cobizmag.com/colorado-ranks-first-in-the-us-for-leed-green-building/

- Cotten, M. N. (2012). The wisdom of LEED’s role in green building mandates. Cornell Real Estate Review, 10(1), 22–37.

- Cotton, C. (2012). Pay-to-play politics: Informational lobbying and contribution limits when money buys access. Journal of Public Economics, 96(3-4), 369–386.

- Daley, D. M., Sharp, E. B., & Bae, J. (2013). Understanding city engagement in community-focused sustainability initiatives. Cityscape, 15(1), 143–161.

- Darnall, N., Henriques, I., & Sadorsky, P. (2010). Adopting proactive environmental strategy: The influence of stakeholders and firm size. Journal of Management Studies, 47(6), 1072–1094.

- Darnall, N., Potoski, M., & Prakash, A. (2009). Sponsorship matters: Assessing business participation in government-and industry-sponsored voluntary environmental programs. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 20(2), 283–307.

- Feiock, R. C., Tavares, A., & Lubell, M. (2008). Policy instrument choices for growth management and land use regulation. Policy Studies Journal, 36(3), 461–480.

- Fuerst, F., Kontokosta, C., & McAllister, P. (2014). Determinants of green building adoption. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 41(3), 551–570.

- Gripne, S., Martel, J. C., & Lewandowski, B. (2012). A market evaluation of Colorado's high-performance commercial buildings. Journal of Sustainable Real Estate, 4(1), 123–148.

- Hawkins, C. V., Krause, R. M., Feiock, R. C., & Curley, C. (2016). Making meaningful commitments: Accounting for variation in cities’ investments of staff and fiscal resources to sustainability. Urban Studies, 53(9), 1902–1924.

- Hawkins, C. V., & Wang, X. (2013). Policy integration for sustainable development and the benefits of local adoption. Cityscape, 15(1), 63–82.

- Hipp, D. R., Kennedy, D., Mistachkin, J. (2015). SQLite. [Computer software]. SQLite Development Team. Retrieved May 25, 2018 from www.sqlite.org.

- Kamieniecki, S. (2006). Corporate America and environmental policy: How often does business get its way? Stanford University Press.

- King, G., & Zeng, L. (2001). Logistic regression in rare events data. Political Analysis, 9(2): 137–163.

- Kontokosta, C. (2011). Greening the regulatory landscape: The spatial and temporal diffusion of green building policies in US cities. Journal of Sustainable Real Estate, 3(1), 68–90.

- Koski, C. (2010). Greening America’s skylines: The diffusion of low-salience policies. Policy Studies Journal, 38(1), 93–117.

- Koski, C., & Lee, T. (2014). Policy by doing: Formulation and adoption of policy through government leadership. Policy Studies Journal, 42(1), 30–54.

- Krause, G. A., & Douglas, J. W. (2005). Institutional design versus reputational effects on bureaucratic performance: Evidence from US government macroeconomic and fiscal projections. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 15(2), 281–306.

- Krause, R. M., & Martel, J. C. (2018). Greenhouse gas management: A case study of a typical American city. In Brinkmann, R., & Garren, S. J. (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Sustainability: Case Studies and Practical Solutions (pp. 119–138). Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK.

- Lee, T., & Koski, C. (2012). Building green: Local political leadership addressing climate change. Review of Policy Research, 29(5), 605–624.

- Levmore, S. (2010). Interest groups and the problem with incrementalism. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 815–858.

- March, J. G. (1962). The business firm as a political coalition. Journal of Politics, 24(4), 662–678.

- Martel, J. C., & Krause, R. K. (2015). The diffusion of climate protection approaches across U.S. cities with distinct greenhouse gas emissions profile types [Presentation]. Association of Public Policy and Management 37th Annual Fall Research Conferences, Miami, FL. Retrieved on March 18, 2018 from https://appam.confex.com/appam/2015/webprogram/Paper12652.html.

- May, P. J., & Koski, C. (2007). State environmental policies: Analyzing green building mandates. Review of Policy Research, 24(1), 49–65.

- Nelson, H. T. (2012). Government performance and US residential building energy codes. The performance of nations. Plymouth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Portney, K. E. (2013). Local sustainability policies and programs as economic development: Is the new economic development sustainable development? Cityscape, 15(1), 45–62.

- R Development Core Team. (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved May 25, 2018 from www.R-program.org.

- Ross, B., López-Alcalá M., & Small III, A. A. (2007). Modeling the private financial returns from green building investments. Journal of Green Building, 2(1), 97–105.

- Saha, D. (2009). Factors influencing local government sustainability efforts. State and Local Government Review, 41(1), 39–48.

- Schattschneider, E. E. (1975). The semi-sovereign people: A realist’s view of democracy in America. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

- Schindler, S. B. (2010). Following industry’s LEED: Municipal adoption of private green building standards. Florida Law Review, 62(2), 285–350.

- Schumaker, P. (2013). Group involvements in city politics and pluralist theory. Urban Affairs Review, 49(2), 254–281.

- Sharp, E. B., Daley, D. M., & Lynch, M. S. (2011). Understanding local adoption and implementation of climate change mitigation policy. Urban Affairs Review, 47(3), 433–457.

- Shinyama, Y. (2016). PDFMiner: Python PDF parser. Retrieved October 1, 2018 from https://github.com/euske/pdfminer.

- Social Explorer. (2019). Data Dictionary: American Community Survey 2016 (5-year estimates). https://www.socialexplorer.com/data/ACS2016_5yr/metadata/?ds=ACS16_5yr

- Spulber, D. F. (2007). The theory of the firm: Microeconomics with endogenous entrepreneurs, firms, markets, and organizations. Cambridge University Press.

- U.S. Conference of Mayors. (2018). List of participating mayors. Retrieved February 16, 2018 from http://www.mayors.org/climateprotection/list.asp.

- U.S. Green Building Council. (2015). Green building costs and savings. Retrieved January 20, 2019 from https://www.usgbc.org/articles/green-building-costs-and-savings

- U.S. Green Building Council. (2017a). Bylaws. Retrieved February 12, 2018 from https://www.usgbc.org/sites/default/files/usgbc-bylaws.pdf

- U.S. Green Building Council. (2017b). Discover public policies in the USGBC’s new Public Policy Library. Retrieved October 18, 2018 from https://www.usgbc.org/articles/discover-public-policies-usgbcs-new-public-policy-library

- U.S. Green Building Council. (2017c). Foundations of LEED (Last revision in 2017). Retrieved February 17, 2018 from https://www.usgbc.org/articles/how-leed-rating-systems-are-developed.

- U.S. Green Building Council. (2018a). People directory. Retrieved January 23, 2018 from https://www.usgbc.org/people.

- U.S. Green Building Council. (2018b). Public policy library. Retrieved January 23, 2018 from http://public-policies.usgbc.org/.

- U.S. Green Building Council. (2018c). Trademark policy and branding guidelines. Retrieved March 15, 2019 from https://www.usgbc.org/resources/usgbc-trademark-policy-and-branding-guidelines

- U.S. Green Building Council. (2019). Organizational member benefits. Retrieved January 21, 2019 from https://new.usgbc.org/benefits/organizational

- U.S. Green Building Council. (2020). Advocacy @ USGBC. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://www.usgbc.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/Advocacy-at-USGBC-2020-Priorities.pdf

- U.S. Green Building Council. (n.d.). State Advocacy Day Playbook for USGBC Chapters. Retrieved November 11, 2020. https://s3.amazonaws.com/legacy.usgbc.org/usgbc/docs/Archive/General/Docs18483.pdf

- USGBC Florida Chapter. (2020). Chapter Priorities. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://usgbcflorida.wildapricot.org/Chapter-Priorities

- USGBC Texas Chapter. (2019). USGBC Texas State Advocacy Day, Feb. 19th, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://usgbctexas.org/event-3158070

- Volokh, E. (2003). The mechanisms of the slippery slope. Harvard Law Review, 116(4), 1026–1137.

- Wolf, L. J. (2018). CenPy. Retrieved September 1, 2018 from https://github.com/ljwolf/cenpy.

- Zuo, J., & Zhao, Z. Y. (2014). Green building research–current status and future agenda: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 30, 271–281.