ABSTRACT

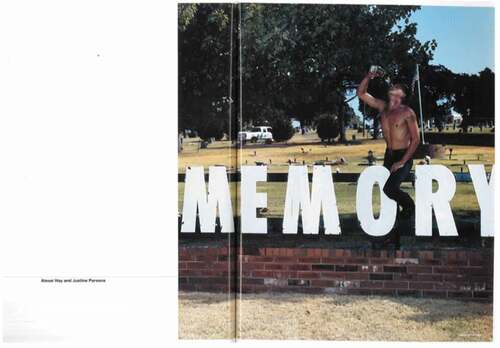

In this article, a photo story depicting “white trash” subjects in the act of defying middle-class proprieties of dress and manners serves as a case study for a critical exploration of the performative registers through which working-class bodies figure as agents of social sedition in the visual economy of fashion. The unglamorous and confrontational bodies in Memory—shot by Alexei Hay and Justine Parsons for Dutch in 2000—enact a parody of professional fashion models by exhibiting an exuberant, uncontained sexuality that cuts against the codes of “good taste” and decorum. The photo spread epitomizes how the vernacular aesthetic of “white trash” has been embraced by independent fashion magazines in order to unsettle the normative aesthetics associated with high fashion imagery and, more broadly, mainstream visual culture. Engaging with Giorgio Agamben’s reflections on gesture and profanation, the article discusses the political effect of an overperformance of corporeality through prosaic, bawdy gestures and argues that the unboundedness of the bodies in the photo spread represents an affront to the capitalist regime of productivity from which these bodies are excluded. Finally, it highlights the contribution of the aesthetic category of “white trash” to the troubling of the representational conventions within the genre of editorial fashion photography and calls for a politically committed rethinking of the aesthetic consumption of fashion images.

Introduction

This article probes how the vernacular aesthetic of “white trash” has been mobilized, since the 1990s, by fashion photography for the deconstruction of the aspirational aesthetics associated with high fashion imagery and mainstream visual culture more broadly. This aesthetic is parsed specifically in Dutch (1994–2002), an independent fashion magazine produced in The Netherlands whose oftentimes humorous visuals mocked and troubled the ideals of beauty enforced by the fashion industry. After providing a historicization of the term “white trash,” I outline how the style, or aesthetic, of “white trash” was fabricated and disseminated within fashion photography. Subsequently, I conduct an analysis of a photo story shot by Alexei Hay and Justine Parsons for Dutch in 2000 and broach the question of what those pictures might do in provoking gestural forms of visibility and sociality that are usually relegated to the margins by the sanitizing morality that hovers over the representations of non-normative bodies in the dominant culture. In my discussion, I employ Giorgio Agamben’s gesture and profanation theories to argue for a radical reading of “otherness” in the performance of a “white trash” identity as well as to think of profanation as a mode of political resistance in commercial culture. Agamben’s under-investigated and fragmentary reflections on the use of the body of the fashion model of the fashion model might provide, in fact, compelling insights on issues of agency, freedom, relationality, and resistance vis-à- the visual economy of the fashion image in a time of advanced capitalism.

In their canonical work on the politics and poetics of transgression, Peter Stallybrass and Allon White illustrate that the social imperative to reject or debase the “low” coincides with the desire for its otherness: this internal conflict captures the apparently oxymoronic nexus of power and desire which constructs the ideological formation of the low-Other. Julia Kristeva defined this precise “interspace between abjection and fascination” in terms of “affective ambivalence” (Citation1982, 204). While the low-Other is excluded as a social being on the level of socio-political organization, it is also symbolically instrumental for the composition of the collective imaginary repertoires of the dominant culture (the “Imaginary”) (Stallyrass Citation1986, 5–6). Manners constitute an important site where the physical and the social, the ideological and the subjective, interlink: the symbolic configuration of the body in the socius occurs through modes of physical self-regulation which inscribe the historical processual formation of the self and are often enacted automatically (Elias Citation1978). Bodily images and forms of bodily comportment are performed and materialized differently according to class (Bourdieu Citation1984): class and gender identities are indeed produced and reproduced on a visceral and corporeal level.Footnote1

With this set of premises in mind, “white trash” can be considered an embodied style of an at times humorous aesthetic debasement which exposes the abject that the individual who has assimilated tactics of affective management and comportment—in other words, middle-and upper-class self-surveillance—socially rejects. However, the negation of one’s potential self-identification with a “style” that feels menacing for one’s sense of self does not foreclose the possibility of corporeal appreciation, for one’s affective negative disturbance might also generate erotic pleasure. White trash operates at the threshold of visibility and invisibility, generating a libidinal lure that has to do with the imbrication of morality and sexuality: by exposing what middle class “good taste” rejects, it also brings to the surface the very repressive mechanisms that prevent the subject from a free engagement with the constitutive perversity of their desire. As I will explain, white trash has to do with the intermingling of class, race, and sexuality, and its manifestation has the capacity to unsettle one’s identity, intended here as a phantasmatic system of self-identifications and projections.

While I am aware that the discussion of representations of an ostracized social group in the context of fashion imagery might lead the way to reading the photo shoot in this article as a mere spectacularization that produces nothing but the reinforcement of the magazine reader’s self-positioning, I develop the argument that in the context of an independent publication like Dutch the trafficking with minor aesthetics such as white trash held the aesthetico-political potential of interrogating and expanding the taxonomies of bodies, styles, and feelings that were, and still are, normative in visual, especially fashion, cultures. By reading the affective embodiment of postures, gestures, and looks of the photographic subjects through Giorgio Agamben’s theories of gesture and profanation, I will elucidate the capacity of white trash figurations for disturbing the normative scripts of mainstream fashion and for interrogating the liberal affective economy of fashion modeling. In so doing, I suggest that rather than merely aestheticizing a “white trash” community for the pleasure of the reader, Hay and Parsons’s photo spread sets in motion a different dynamic wherein the subjects provocatively use their bodies in ways that redefine the communication with the photographer and the viewer.

In addition to showing how white trash functions affectively, aesthetically, and politically within the context of fashion editorial photography, in other words how it operates within and through the images, I also aim to discuss how with and beyond the images the viewers could be mobilized toward an ethical reconsideration of the politics of relationality. Thus, I explore the contribution of a white trash aesthetic to the disorganization of both the conventions of representation within the genre of fashion editorial photography and to practices of spectatorial engagement. Ultimately, I seek to unfold the disruptive potential of trash gesturality in relation to the general affective economy of “aspirational normativity” (Berlant Citation2007, 301) that typically sustains collective attachments to “the fantasy life” promised by the culture of capitalism (Berlant: 278).

White trash: history and popular culture

The origins of “white trash” have been traced back to the fifteenth-, sixteenth-, and seventeenth- century association, among the English bourgeoisie, of poverty with laziness, immorality, danger, and lasciviousness. However, the actual fabrication of their identities, with different names across the centuries such as “squatters,” “crackers,” “tackies,” “hillbillies,” “rednecks,” “white trash” and “trailer trash” occurred later on in the eighteenth-century, when, especially in the British colonies of Virginia and North Carolina, the “lazy lubber,” excluded from land ownership, became “a picaresque curiosity, an ethnological oddity” (Wray Citation2006, 135). “Lubbers” lived geographically outside the lands that fell under judicial and administrative powers and economically survived by squatting, grouping with other marginalized groups such as runaway slaves and native Americans. Because of their survival strategies they were viewed as symbolic threats to the social order.

As such survival strategies began including raiding and thieving, the threat represented by the “lubbers” became also a political one and the image of the colonial poor white evolved into a figure of violence and treachery known as the “cracker” (Wray: 136). As the repressive apparatus of the colonial government was set in place to face the threat posed by crackers, “poor white trash” turned from a regional odd stigmatype to a national concern in the context of the debate about their assimilation within the social body. In the antebellum period white trash was often the subject of public debates and the label “white trash” was indeed attached to poor white people living at the margins to verbally stigmatize their meagre living conditions. The “trashy” nature of poor white people was attributed either to their social and economic exclusion or to genetic heredity (Wray: 137). Anti-poor white trash campaigners were successful in triggering a process of stigmatization that has persisted until the present.

In the 1950s the cult of Elvis Presley shook the image, until then stigmatized, of poor white folks by revitalizing it through an aspirational narrative of the American dream. No longer rural outcasts, working-class “white trash” men could become successful, glamorous, and ascend the social ladder to the point of being publicly promoted by the nation (Isenberg Citation2016; Sweeney Citation1997). The figure of the poor rural white was indeed largely popularized through cinema and television. As Scott Herring (Citation2014) has shown, in the 1970s the genre of “hixploitation” cinema, by exposing the sexual debauchery and unruliness of the rural poor white, reinforced the stigmatizing social imaginary of the non-urban working class, eventually impacting the consolidation of national political conservatism. “Hick flicks,” as these movies were also called, portrayed scenes of unrestrained sex acts occurring outdoors in swamps, forests, and pigsties, often thrilling and shocking audiences by staging scenes of exuberant group sex and incest (Herring Citation2014, 99–100).

In the 1970s, John Waters, especially with the success of Pink Flamingos (Waters Citation[1981] 2005), brought a radical trash aesthetic to the wider public. His was a peculiar kind of “filthy” trash, aimed at unsettling audiences by shattering taboos and exposing, via humor, a poetics of immoral human behaviors. By employing shock as an aesthetic ruse to prompt his audience to rethink their values, Waters understood the potential of using obscenity as a viscerally liberating way of disquieting puritanical worldviews. In a different vein, Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey’s Trash (1970) documented instead the attempt of heroin-addict Joe (played by Joe Dallesandro) and Holly (Holly Woodlawn) to get on welfare by faking Holly’s pregnancy in order to sustain their drug scoring. Here, the typical white trash sexual debauchery is replaced by Joe’s sexual impotence caused by excessive drug consumption, which inhibits his sexual appetite. Joe’s attractiveness and the urban context of New York shifted the scripts of white trash representations from rural depravity to urban junk, the latter not bereft of a patina of underground “coolness.” Through these different channels, among others, white trash representations proliferated with variations that expanded the spectrum of representational possibilities. By the end of the 1980s, white trash was officially “branded” as an identity with its own identifiable cultural forms (Isenberg: 270).

Historian Allan Bérubé, recounting his upbringing in a New Jersey trailer park, teases out the “pop culture, retro-fifties nostalgia” that in the 1990s resurrected the imagery of trailer park life, recoding it as campy trash style through ironic and parodic books, souvenirs, and advertisements depicting those very stereotypical figures that had been historically identified as unworthy of national belonging (Bérubé Citation1997, 36–37). Bérubé’s account of trash reveals how porous and mobile the aesthetic form of trash is. Anthropologist John Hartigan (Citation2005) notes that in the wake of the surge in usage of the term and representations of “white trash” in popular cultural productions, white trash also began to serve occasionally as a means of self-identification. He connects the phenomenon to the popularity of entertainment figures such as the rapper Eminem and the comedian Roseanne, who deliberately claimed the epithet as a form of self-designation (Citation2005, 110–111; 160–162).

The racial aspect of white trash (that is, its whiteness) is inextricably dependent on class, to the point that scholars of the rural working class have considered whiteness as a social category rather than a racial one (Wray Citation2006, 139). White trash has functioned, historically, as a rhetorical identity associated with a category of pollution through which the behavior of white Americans of lower-class status has been evaluated. It is the very identification and policing of those who seem to breach the conventions of social and moral decorum that enables the subsistence of whiteness as the unmarked norm. The comportment of certain white subjects, in fact, can disturb ideas and perceptions of sameness/difference and belonging/unbelonging, hence ratifying a host of social anxieties, to the point that said subjects are concomitantly recognized as white yet also expelled from the privileged, hegemonic domain of whiteness: this intra-racial struggle over the legitimacy of belonging is at the core of the rhetoric of white class distinction (Hartigan Citation2005, 113–114; 59–60). Thus, white trash “is neither just a name nor a distinct social group. Rather, it is a form of objectification,” tapping primarily into the socio-cultural anxiety of pollution and contamination, through which white American citizens have identified and debased an economically disadvantaged group of fellow citizens as a threat to the state (Hartigan: 106).

Provided that “white trash” is a label attached to the rural working-class by the white upper classes and only later taken on by “white trash” subjects to define themselves, “white” functions as a racist and classist marker to assert the exclusion of non-urban working-class subjects from the privileged regime of racial invisibility. It operates as a socio-symbolic marker that differentiates one’s sovereignty, as a socioeconomically hegemonic subject, from the subaltern condition of poor people whose worth and disposability (trash) is so dramatically visible that it deserves an identifiable racial marker (white) to cast out and shame its obscenity. Whiteness, in fact, is constituted as an invisible norm, the uncontested epicenter from which racial determinations irradiate. Whiteness, in its assumed invisibility and universality, longs for a metaphysical detachment from corporeality: in Richard Dyer’s words, to some degree it aspires to “dis-embodiedness” (this aspiration to transcendence is most likely owed to the cultural impact of Christianity on ideas of the body) (Citation1997, 39). The nexus of bodily image and race/class/sexuality will be central in my analysis.

The aesthetic of white trash in fashion photography

The first instances of appropriation of working-class stylistic tropes by middle-class taste and mainstream fashion hark back to the mid-1980s and represent “an aspect of broader themes in post-punk fashion and design, and post-modern art prevalent in this period of bricolage […] and the knowing, disingenuous celebration of camp and kitsch” (Patrick Citation2004, 232). What started as a practice of ironic resignification of excessive or prosaic elements into designer collections came to create an entire vocabulary that defined the aesthetic identity, as well as the economic fortune, of many high-fashion brands. In 1988 cultural critic Margo Jefferson reports for Vogue on this trend: “While books, magazines, and TV have been wallowing in the lifestyles of the rich, richer, and famous, a counter-trend has evolved–downmarket chic. Part nostalgia, part condescension, it’s a campy attitude toward trailer parks and diner food, redneck rock and inarticulate heroes.”

It was not until the 1990s, however, that the appropriation of white working-class self-fashioning was labeled “white trash.” In Citation1993, New York Times fashion critic Amy Spindler draws attention to white trash in her essay “Trash Fash,” where she observes that the interest in white trash was spreading from cinema to fashion, suggesting that “[t]he fascination with trailer-park esthetics neatly parallels a trend that has left whites by the side of the road: hip-hop and gangster rap, with their emphasis on impoverished roots and violence” (10). Similarly, Adele Patrick (Citation2004), who has assembled an archive of articles featured in women’s magazines that promoted the embracing of white trash styles, identifies music and popular culture from the early 2000s as the main sources of inspiration and diffusion of white trash as a style across the media and street fashions.

A plethora of different stylistic strands could be identified within the domain of white trash. What Patrick and press articles from the early 2000s refer to is a lineage that can be woven into what Pamela Church Gibson calls “pornostyle” (Citation2014). “Pornostyle” stems from a mainstreaming of white trash “excessive” styles that in the spectacularizing process of “pornographication” were stitched together with sensual attitudes and clothing items derived from porn films and reality television shows. This kind of “glamorous trash” that proliferated through mainstream media differs, however, from the more literal white trash aesthetic of trailer parks that in alternative fashion photography of the late 1990s gradually penetrates into, blends, or overlaps with post-punk “grunge” aesthetics. As the visual analysis of the case study will evince, in the white trash aesthetic encountered in independent magazines, cheap opulence is replaced by exuberant lack, as shown by an untitled photo spread shot by Corinne Day in 2001 for issue n. 35 of Dutch in which young men and women hang out in garbage settings like landfill sites, urban tent cities, or filthy interiors.

A well-known photograph of model Kristen McMenamy—in which she is posing naked with the word “Versace” in a heart lipsticked on her chest—by Juergen Teller for i-D in 2003 is illustrative of the upfront, careless and unassuming attitudes of naked models smoking, drinking, and just “hanging out” that we encounter in trashy realist pictures from the early 2000s. Fashion scholars have sketched out the mutual influence of fashion photography and pornography, and have highlighted how, in contrast with the highly stylized, sexy, and sophisticated pornographic imagery promoted, for instance, by Tom Ford’s advertising campaigns for Gucci in the 1990s, which were largely indebted to the work of Guy Bourdin and Helmut Newton, photographers like Juergen Teller employed techniques adapted from porn cinematography to create raw scenarios that challenged the hyper-commercial character of those images that were so popular in the 1990s (Church Gibson and Karaminas Citation2014). Moreover, beyond fashion photography, there is a long-standing precedent for the crude immediacy of the photographic subject’s body as a cultivated photographic aesthetic, which can be traced back at least to the work of Nan Goldin, Larry Clark, and Wolfgang Tillmans, who introduced a style of “trashy realism” into fashion photography. Their pictures functioned as social documents of the underworld, pushing photography to blur the boundaries of documentary, art, and fashion. Via this route, realism became a trend in fashion photography and many of its tropes are still evident in contemporary fashion imagery. These considerations are instrumental to introducing my case study, a photo spread shot by Alexei Hay and Justine Parsons for issue n. 30 of Dutch in the year 2000.

Hay is an American photographer whose work has been defined by photography critic Vince Aletti as “frisky, funny, a little fucked-up,” drawing from both photojournalism and Hollywood conventions, and characterized by a certain “ruthlessness” that emerges in the casting of usually young working-class subjects. According to Aletti, Hay photographs outsiders and outlaws not to protect or identify with them but to observe “with flashes of genuine feeling” how their lives and stories play themselves out (Citation2000, 130). In contrast, Parsons is associated with a wave of female artists including Elaine Constantine, Elinor Carucci, Ellen Nolan, and Liz Collins, who, in the late 1990s, began rejecting the conventional looks and unattainable beauty standards typical of fashion magazines and shooting ordinary people in more genuine situations and settings (Colman Citation2000). This group of photographers aimed to create “natural” and unretouched scenarios that questioned the artificiality of those images that had been so popular throughout the 1980s. Around the year 2000, Hay and Parsons partnered on a few experimental photo shoots.

The fashion story under examination in this article must be understood in the context of an editorial project oriented to the transmission of gestures and moods that helped shape alternative aesthetics unbound from the representational genres in vogue in fashion publications in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Whereas mainstream fashion magazines, or “glossies”, have historically tended to exclude non-normative bodies from representation (although this has gradually been changing, with the neoliberal assimilation of minoritized subjects in the pages of commercial magazines in the 2010s), independent fashion publications have been considerably more inclusive in terms of both their written and visual content. Archival research in independent fashion magazines from the 1990s unearths photo spreads, whose aesthetic often appears to be informed by feminist and porn zines more than by classical fashion imagery, featuring all kinds of non-normative bodies and subjects (Filippello Citation2019, 339; 353).

In Dutch, for instance, soft-porn snapshots of male models taken by Matthias Vriens were juxtaposed with Corinne Day’s trashy stories or Steven Klein’s somber portfolios. A sexualized imagery cohabited with the vernacular and the prosaic in its photographic narratives. Due to arresting images which avoided clear-cut understandings and codifications of masculinity and femininity, Dutch acquired resonance and popularity as an “avantgarde” magazine. It was precisely through a liberal approach to sexuality and identity that the magazine pushed for “the gradual dissolution of all manner of habitual and prejudiced ideas about sex and corporeality” (Teunissen Citation2015, 66). For instance, the figures of the asocial violent teenager, the gay porn actor, or the spaced-out suburban girl, i.e. all subjects in a position of possible social disenfranchisement, recur in the narratives of Dutch magazine, having as precursors erotic magazines, hixploitation movies, New Queer Cinema, and documentary photography. These characters bear witness to a sensibility which collides with the rather clichéd identity representations found in more commercially oriented imagery. With its photo stories, Dutch played a part in opening up countercultural feminist aesthetic scenarios in fashion photography.

Gestural profanations

Hay and Parsons’ photo spread does not have a title; however, as its opening photo foregrounds a sign that reads “Memory,” for the purposes of this article I will be referring to it as Memory. The opening shot () shows a tanned young man pouring scotch out of a bottle over his face. In view of his tan, the sunny weather, and the style of the car in the background it can be inferred that the story was shot in a southern, or perhaps midwestern, state in the U.S. Mimicking commercial imagery where actors and pin-ups cool off with water bottles, he is performing the same kind of action with a bottle of scotch. He is sitting with legs astride on the welcome sign to the cemetery. Behind his back we can see the tombs and an American flag. This first image introduces us to a theatrics of profanation wherein appropriateness and consideration for the state (the flag) and human death (the tombs) are beyond the photographic subject’s concern.

In Giorgio Agamben’s philosophy, profanation is an urgent political task, a modality of resistance against the “unprofanable” and the instigation to separation. A profanation is a way of returning things to the free use of the people (Citation2005, 73). It is a “return” in the sense that things, eventually, can get repossessed by the commons after rituals (of the state and religion, for instance) have subtracted them from the “human law”; they go back to their condition before the interruption of contact between people and things, that is, prior to any form of separation.Footnote2 Quoting Agamben, “To profane means to open the possibility of a special form of negligence, which ignores separation or, rather, puts it to a particular use” (Citation2005, 75). A profanation, according to the philosopher, can sometimes be effected through play and has the purpose of neutralizing the unavailability of its object, namely, to reinstate the thing into its original space so as to defuse the apparatus of power which had seized hold of that very space.

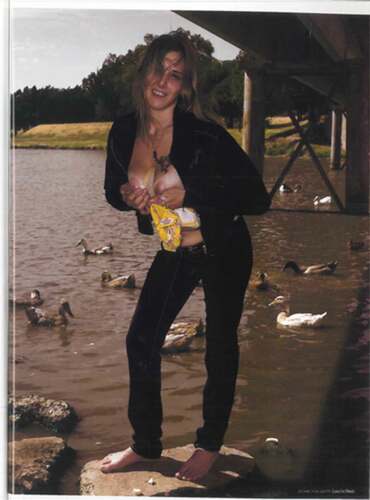

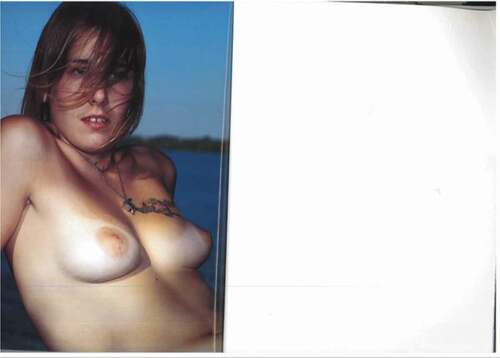

In the second shot of the sequence (), a young woman with her jacket unzipped is exposing her breasts. She is standing on a rock by a lake. The crumbs next to her feet tell us she has been feeding the ducks in the background: an action too mundane to be featured in a fashion magazine if not for humorous purposes. She is pushing her breasts against each other to squeeze in a slice of bread in the middle. The “motorboat” gesture confronts the viewer with an unexpected ludic performance of kink. Profanatory gestures refer, according to Agamben, to the “intersection between life and art, act and power, general and particular, text and execution. [The gesture] is a moment of life subtracted from the context of individual biography as well as a moment of art subtracted from the neutrality of aesthetics: it is pure praxis” (Citation2000, 80). The gesture is a pure exhibition of mediality insofar as it is neither a means to an end nor an end in itself; and in making a means as such visible, it pries open for people the sphere of ethos: it “allows the emergence of the being-in-a-medium of human beings and thus it opens the ethical dimension for them” (Citation2000, 58). In the picture, the messy hair, the poorly designed tattoo on her breast (see also ), and the use of sliced bread as a sex prop, are all signifiers pointing to a performative exhibition of “white trash” stereotypical identity. Two key elements of this image contravene the rhetoric of fashionable representability: the model’s facial expression and her posture. Within the perfectly balanced composition of the shot, the subject is placed at the center of the frame, humorously inviting the camera and/or the viewer to join her for a “titty fuck.”Footnote3

In a full mockery of the rationalizing modernist body performances and mechanical smiles of fashion models (Evans Citation2013), the model is proudly and jokingly exposing her teeth with her mouth almost fully opened in a laugh that might register either her being self-conscious about her act or her being high. She is bluntly enveloping the eyes of the viewer in a visual field wherein the optical focus is on her breasts mimicking a sex act. There is more than an affective recalibration of models’ rhetorical movements: the images play with affective registers of loud exuberance and shamelessness that translate into eruptive piercing visuality. The model’s disquieting impact is also achieved through her singularly unglamorous looks. In this sense, this photo shoot constitutes an exception to Caroline Evans’s statement that a model is always “both idealised and other” (Citation2003, 75), since here the bodies of the models most likely do not offer themselves to any psychic process of idealization; the body is “other” from the aspirational bodies of fashion models (whether these are slim, extremely skinny, or “curvy”) insofar as in Memory the models humorously flaunt the signs of the working class tattooed on the surface of their skin.

Laura Kipnis has assessed how “improper bodies have political implications, and are particularly valenced in relation to issues of class.” By improper bodies, she means bodies “that defy social norms and proprieties of size, smell, dress, manner, or gender conventions; or lack of proper decorum about matters of sex and elimination; or defy bourgeois sensibilities by being too uncontained and indecorous—these bodies seem to pose multiple threats to social and psychic orders […]” (Citation1997, 114). These kinds of bodies can be employed as instruments of social sedition since, as Kipnis reminds us following Foucault, the body is what any system of power is committed to keeping in its place. The unmannered and out of control bodies of the subjects in these photographs expose an unruliness that mechanisms of psychic repression tend to keep under control. These bodies, exposing their erotic ebullience, constitute a problem or a disturbance in the customs of polite society. As Cathy J. Cohen sharply observed, sexual deviance from a prescribed moral norm has been used to demonize even segments of the population that fall under the label of heterosexuality, such as the “lazy people” living on welfare (Citation1997, 457).

The unruliness, or excess, of the subjects’ bodies can also be a compensatory act for their symbolic and material negative recognition in the outside world. The anxiety of being deemed unworthy or disposable (trash) is managed through prosaic bodily over-performances that cannot be ignored by those who are themselves complicit with capitalist logics of separation, and that leave an affective mark on the ordinariness of places and others. With bold physical freedom, they elbow through the maze of symbols from which they are left out. In a libidinal economy that either de-sexualizes excess with the purpose of sanitizing it or adamantly ignores it in the attempt to annihilate it, the stereotypical white trash exuberant sexuality is redeployed by these subjects as free-spirited so as to playfully encourage the viewers to confront any possible anxious discomfort over the public, shameless exhibition of working-class erotic bodies.

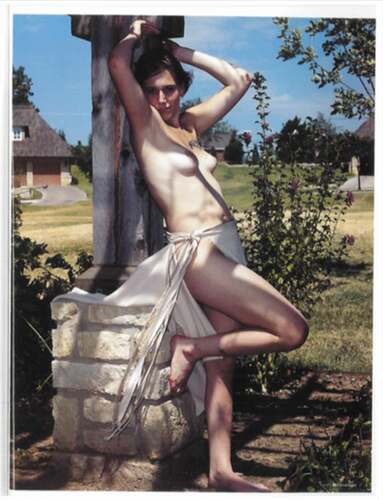

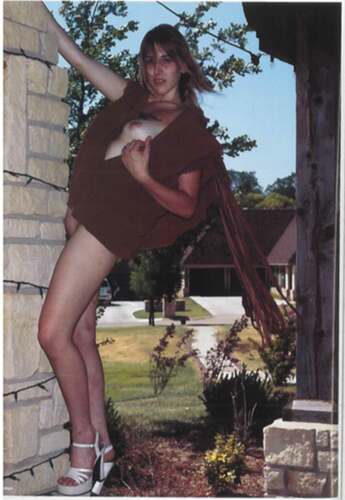

In the shot pictured below (), the subject is wearing a chiton-style skirt that, with no undergarment, exposes her bare legs emulating the postures of statues from classical antiquity. We can glimpse some houses in the backdrop, which tell us that the models and the photographers might have been playing a game of hide and seek: a kind of interaction that is clearly at odds with the constructed dynamic of a fashion editorial sitting. With a naughty sneer on her face addressed to the photographers/viewers, her clumsy attitude takes the form of a parodic performative embodiment of how idealized bodies of Greek statues and fashion models alike instill aspirations among the middle class. At the margins of aesthetic inclusion, the models in this shoot stand for a mockery of the hyper-capitalist regime of visibility that via fashion magazines, among other channels, establishes standards of appropriateness and sets paradigms of representability. Here, before the viewer’s eyes, there is a straightforward display of what the fashion magazine’s consumer normally steers clear of: the “primitive” exhibition of the body, which does not encapsulate any viable and desirable attitude for the reader to take on. The dearth of clothing in this photo shoot, and the thrifty look of the few garments that are actually featured, makes this “profanation” of the medium (i.e. the model’s body), which conventionally is “used” to convey highly staged yet legible styles of affect and aesthetic in conformity with the commercial magazine’s mode of address, even more palpable. Additionally, the model is leaning with her back on what seems to be a cross, erected over a tomb. We are brought back for a moment into the graveyard from the opening shot. From observing a man getting wet and drunk over the cemetery’s welcome sign, we have now moved to witnessing the playful contact between the naked flesh and the tomb.

In this photo story profanation operates doubly. On the one hand, there is a profanation of the consumerist employment of the medium of the magazine as a means toward a commercial end: there are barely any saleable clothes in the pictures and the models are far from being and looking commercially purposeful. On the other hand, the kinesics and proxemics of the subjects in the photos profane the upper middle-class mannerisms of composure that are ritualistically learned and enacted by professional fashion models in their work in front of the camera. In addition to restoring a natural state of pre-encumbrance of external power over the body, profanation can also act as a form of play, a “pure means,” that is, a praxis that is isolated from its possible relationship with an end. In other words, by deactivating the uses of the body (Agamben uses Jean-Luc Nancy’s term “inoperative”) imposed by the exercise of power, the act of profanation can become pure mediality without teleology. This resignification of the medial use of the act reinscribes the latter into the domain of potentiality, therefore opening it up to new and generative uses.

In closing his reflection on profanation, Agamben resorts to Benjamin’s concept of “exhibition-value” (Ausstellungswert) to describe the work of fashion models and porn stars (Citation2005, 88–92). He suggests that the bodies of these actors are exhibited as removed from the sphere of use, in the sense that they exhibit themselves, henceforth creating value in the very act of exhibition. Models and porn stars achieve this pervasiveness of exhibition-value, according to Agamben, through the “inexpressive” look on their faces (he speaks of “nullification of expressivity”), which signals nothing beyond itself. By stating that the model’s body is conflated with exhibition-value Agamben is arguing that the “brazen-faced indifference” of fashion and porn professionals displays the human face (and, by extension, the body) as a “pure means”: it is “bare” because these bodies show themselves as absolute mediality. For Agamben, pure mediality does not imply an annihilation of possibilities. Quite the contrary, the reduction to pure means avails the object of new uses and forms of communication. This latter part of the argument, namely the unfurling of novel modes of use of the body, is particularly salient and useful in order to conceptualize possibilities of corporeal resignification.

Going back for a moment to Agamben’s earlier work, in The Coming Community (Citation1990) he had already put in correlation the fashion model and the porn actress in an epigrammatic passage in which he writes that, with the invention of photography and the consequent serial reproduction and distribution of images, “the body now became something truly whatever” (47). Here, he is influenced by Debord as he argues that, in the present era, the commodity form has come to regulate social life and that experience has been replaced by “spectacle,” which is a social relation that separates human beings from each other and hence alienates sociality itself. So, when in 1990 Agamben originally refers to the body of the fashion model as a whatever-body, he means that with the spectacular manipulation and commodification of the female body in the epoch of technological reproducibility, the body has lost its specificity and has become pure image, a separate thing from actual physical living bodies. I believe that this view is assuaged and redirected toward more sanguine outcomes in Agamben’s later work.

In Profanations (Citation2005), in fact, as I have mentioned previously, Agamben engages again in a reflection on the body of the model and the porn star, but this time he does so via Benjamin. In this essay, he quotes film director Ingmar Bergman who in reference to Swedish actress Harriet Andersson’s performance in Summer with Monika (1952) commented: “There is established a shameless and direct contact with the spectator” (2005, 89, my emphasis). Agamben uses this statement to affirm that in commodity society the bodily performance, including the facial expression, of women on screen has become more animated, to the extent that they seem to be playing for the camera with a high degree of awareness of their own spectacle. In performing the awareness of being watched, he writes, fashion models and porn actresses show exhibition itself. Exhibition-value is used here by Agamben as a descriptor of the affectless modality of the model’s or actress’s self-staging and is taken as emblematic of the spectacle of the human body at the time of advanced capitalism. At this point, however, Agamben finally takes a step further toward a reconsideration of the potential of what he reads as shameless indifference: precisely because of the models’ “impersonality,” the exhibition of their body to the eye of the camera opens itself to another use “which concerns not so much the pleasure of the partner as a new collective use of sexuality” (Citation2005, 91). In other words, Agamben reveals that the models’ staged indifference might have the capacity to generate, or gesture at, creative and unexpected relational outcomes. Aside from this brief comment, unfortunately Agamben does not provide further insights as to the kinds of uses of the body that the model/actress might unlock.

When Agamben writes about the indifference of the faces and bodies of the fashion models he is thinking about the exemplarity of their lack of specificity. I propose that their unpredictable uses of the body might be thought of, via Agamben, as openings into the ethical sphere of potentiality, intended as that which cannot be reduced to its presentness: potentiality is immanent yet not actual, it can be imagined as unfolding in the horizon, which means that we can understand it only in its constitutive futurity (Agamben 2000). If we understand the uses of the body as indeterminate and indefinite (but still contingent upon the body’s materiality), then the body is “whatever” in the sense in which whatever “is the event of an outside” (Citation1990, 66): it is always in relation to something. To use Agamben’s terminology, in its being “such as it is,” it is “pure relationship” and in such a relationship it can take on new qualities and properties and thereby make a free use of itself.

Thus, the intrinsic mediality of the fashion models’ use of their own bodies may, as a medium without an end, beckon toward new forms of communication and interaction. I suggest, on the one hand, that the model’s body undergoes a process of commodification under the gaze of designers, photographers, magazine readers, and the prospective consumers of the goods they promote; on the other hand, the face and bodies of the models are far from being static or “indifferent,” as Agamben claims (he speaks of their lack of facial expression hyperbolically as “the most absolute indifference, the most stoic ataraxy” [Citation2005, 91]). The models featured in the commercial fashion photographs which Agamben presumably has in mind may indeed have a dégagé or carefree expression; however, while I do understand his assertion as pointing to a common lack of individuality, it would be perfunctory to take as a given that models look “indifferent.”

Moreover, there exist two kinds of fashion models, whose bodily performances usually diverge: fashion editorial models are required to work as film actresses, impersonating a character in order to co-produce a narrative with editors and image professionals on set; in a different manner, commercial models can look “indifferent” or “affectless”—although they most certainly are not, for there is conspicuous affective work behind the performance of affectlessness—to the degree that, as Debord would put it, they need to act as “stars of consumption.” I argue that, as the bodily performance of the models in Memory demonstrates, it is exactly the models’ capacity to modulate affective registers beyond staged inexpressiveness that renders their mediality so eloquent. They are not impassive, and their bodies are not a tabula rasa. Their affective mobility is indeed the most valuable resource of their body’s potentiality for “otherwiseness”; namely, through their affective memory and knowledge they can suggest possibilities of embodiment or critical thinking that are hard to predict or that, in Agamben’s terms, may be without an end.

For the Italian philosopher, the porn actress, who in performing her erotic gestures becomes a means addressed to the end of giving pleasure to the spectator, is actually suspended in and by her own mediality, and can thus become the medium of new forms of pleasure and contact in the audience. This can well be applied to the fashion model (although there are certainly numerous differences between fashion models and porn stars on the level of their use of the body which Agamben does not address): the models’ bodies in their gestural performativity can function as affective mediality that disturbs and paves the way for new modes of looking, connecting, and thinking about one’s pleasures and desire, as well as those of other bodies.

Affective labor and the meaning of whiteness

Elizabeth Wissinger (Citation2007) has described the work routinely undertaken by fashion models in terms of immaterial and affective labor (two notions derived respectively from Maurizio Lazzarato and Antonio Negri). The models’ affective work is in line with capitalist productive strategies in ways that are not merely about the sale of commodities: modeling, in fact, is also, and most importantly, about calibrating bodily affects in various forms. In the immaterial-affective work undertaken in front of the camera, the fashion model creates, together with the team of professionals involved in the production of the shoot, affective networks and intensities: these affective energies are, later on, virtually manipulated in their economic distribution. Wissinger’s account of the affective labor of models is useful in order to fill the gap left by Agamben’s account of the mediality of the model’s body: the actual potentiality of this type of body resides, beyond its exhibition-value, in what, following Toni Negri, can be called “value-affect” (Citation1999, 79). The immaterial labor of the model’s body, using Negri’s language, “becomes affect or rather, labor finds its value in affect” (which conjures Spinoza’s description of being affected as an increase or decrease in the body’s vital force).

Thus, the affective capacity of the model’s body coincides with a twofold potentiality: it is produced, transferred, circulated and distributed in the form of what Elspeth H. Brown terms “commercialized affect” (Citation2012, 37, Citation2017, 289), a formula indicating that the body is socially articulated through collective forms of affective labor embedded in the consumer economy; but also, it can open to the unexpected by being dynamic and creative: challenging the boundaries that keep the body composed and decorous and upending those same visual rhetorics that instrumentalize bodies in order to produce and disseminate “commercialized feelings.” Such an affective capacity of the model’s body entrusts it with more agency and reveals affect as potentially transformational. Negri writes that affect is “an expansive power … a power of freedom, ontological opening, and omnilateral diffusion.” Such power of incommensurability and uncontainability lies in the fact that “affects construct a commonality among subjects” inasmuch as they express a commonality of desire that may be collective, expansive, and possibly universal (Citation1999, 85). Negri remarks that despite the politico-economic attempts to regulate and control the expansivity of affect, affect can always bind communities and consequently move them toward action and transformation.

The white trash bodies in Memory stand for this expressivity that resists containment. Quoting José E. Muñoz (who is inspired by Althusser’s philosophy of the encounter to imagine a punk theory of the commons), I propose that the “trashy” bodies in the photo spread are enacting “the social choreography of a potentially insurrectionist mode of being in the world” (Citation2013, 97). In a space abandoned by capital, the subjects mock the very affective labor carried out by commercial models subjugated by, or complicit with, the regime of productivity. They are doing so by using humor in a scene of abandonment. They exceed the dialectic of activity/passivity or productivity/non-productivity by being overly active in unproductive activities; that is, by overperforming a use of the body that leads to no productive end. They use their bodies “queerly” in an affective excess of aesthetic boundaries of moral representability, namely, in defiance of the neoliberal expectations placed on bodies to perform in constructive ways.

What should also be emphasized in the context of this photo shoot is the specific whiteness of these models’ “trash bodies.” Gesturing, in fact, confronts social demands of normativity that have to do in equal measure with gender, sexuality, and race (Noland Citation2008, x). Obscene or excessive gestures signal the body’s refusal to be domesticated by socially built moral codes, which are even more vehemently repressive when they are attached to non-normative bodies. The peculiarity in the instance of white trash bodies is that they look simply white, and therefore not “uncommon” or “aberrant”; however, they are socioeconomically chastised as eccentric, or worse, as waste. The flaunted “sluttiness” and “tackiness” of the markedly “white trash” bodies in this photo story could be read as an affective form of disidentification with the dominant body of the upper classes. Whiteness, in other words, functions as an intensifying marker of a working-class aesthetic that disquiets the body politic, socially as well as erotically, through exhibitionism.

Richard Dyer has pointed out how, in the visual arts, whiteness is usually visualized and recognized qua whiteness only when white bodies are juxtaposed with non-white bodies (Citation1997, 13). In this photo spread, however, whiteness is all-pervasive and its very spectacle renders it the conceptual and visual focus of the representation. Here the bodies are tanned and sweaty: they carry the markers of the working class. That is to say, their whiteness is racially signified through class signifiers. The immateriality, or disembodiment, of whiteness is counteracted in this photo spread by a precisely antithetical excess of corporeality. The unboundedness of these bodies is equated with an unredeemable cheapness of looks that resists the sanitized representations of bodies and their reification as covetable luxury goods in mainstream culture.

Figures of white trash are in fact designated as white because they are often “monstrously” so (Newitz Citation1997, 134), and they cannot be reduced to aspirational marketable images with commercial value. The idiom of monstrosity is hyperbolic; however, it is the very untamable visibility of the poverty of looks and taste that accounts for the racialization of the working-class “trash” subject. The bodies in these images might interpellate white viewers to confront how the disavowal of one’s own whiteness occurs by displacing it onto others who they deem subaltern: a process of inversed displacement, or “displaced abjection” (Stallybrass and White Citation1986, 53). In this sense, white trash bodies prompt privileged white subjects to become self-conscious about the invisibility of their race, and they do so by exposing the “horror” of whiteness, namely the very abjected trash that bourgeois morality rejects.Footnote4

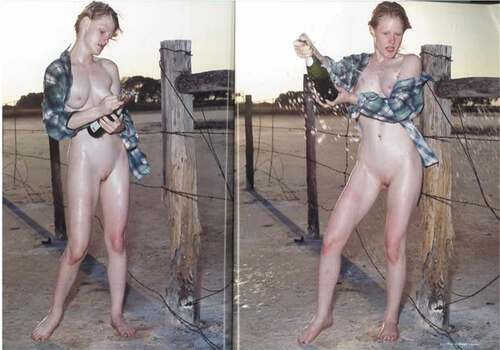

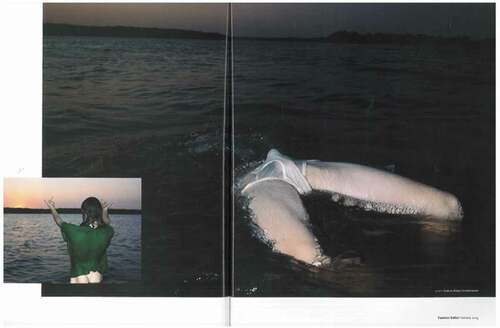

From the tanned bodies encountered in the previous shots, in the double-page spread in the next page () there is a shift to a luminous, translucent, soft, marble-like surface, which nevertheless does not contain its excess. The visceral abrasiveness of these “white trash” bodies is also enhanced through the lighting. On this point Dyer argues that lighting is an aesthetic technology that has been used in cinema to construct images of white people; in other words, technological modes of representation have been historically implicated in the ideology of whiteness (Citation1997, 82–84). In Memory, Hay and Parsons are shooting in natural light, at times resorting to bare flash for harsh, direct, extra lighting on the sweat and tan of the bodies. The photographic technique, overall, is intentionally unpolished and carefully reduced to basics. Thus, they are not employing lighting as a tool for coding aspirational femininities or masculinities; instead, their technique aims to be consistent with the bare “authenticity” of white trash as it frames everyday scenes of working-class youth life. In , sweating, with just a grungy plaid shirt on her shoulders, the model is uncorking a sparkling wine bottle, conjuring up the embodied anti-sociality typical of hard-drinking and hard-smoking music icons such as Courtney Love and her 1990s rock band Hole. She is out in the country, next to a barbed wire fence. The full nudity and the exposure of genitalia is indebted to the boisterous attitude of “all-girl zines that are all about hot sweaty all-clits-out girl power” (Kipnis Citation1997, 129–130).

The eroticism exuded in the pictures above is reminiscent of the feminist riot girl aesthetic of trash that one could encounter in girl rock music zines. It is also influenced by an aesthetic of amateur porn that provides a stage for white trash looks and tastes. Constance Penley has construed trash as a genre that manifests itself “as a form of populist cultural criticism” whose operationality is germane to pornography, which has historically challenged political, religious, and moral authorities (Citation1997, 92). The raunchiness, the ostensibly stupid humor, the sluttiness—all elements that Penley encompasses under the rubric of “bawdiness,” which taps into the aesthetic and erotic of the “stag film” (Waugh Citation1996)—are properties of the in-your-face confrontationality against codes of decorum that porn zines share with white trash.

Fashion photography is one of the fields of visual culture that is most evidently informed by uses of the body derived from pornography. The style of postures that we encounter in the photo spread under examination appears to be influenced by amateur porn photography as much as by “cheesecake pin-ups” from the 1950s. In particular, the quirky eroticism of Bettie Page is often referenced in the work of Alexei Hay. Black and white images of model Karen Elson with bangs (a literal reference to Page) shot by Hay for issue #37 of Dutch in 2002 evidently recall the postures and attitude of the pin-ups. The lively sensuality of the glamorous erotic photography from the 1950s is, however, reframed by Hay and Parsons in a trashy realist aesthetic, in which the models of our photo spread are immersed. In , the model is exposing her breast while leaning back in a pose that, as the platform shoes conventionally worn by strippers or porn stars suggest, we could easily come across in a porn magazine. The visible presence of a house and a parked car in the background call to mind the outdoor scenes of amateur pornography. The fashion set is turned by Hay and Parsons into a ludic erotic playground.Footnote5 The humorous faces, clumsiness, and uninhibited self-presentations of the models in Memory appear indeed to owe more to amateur pornography and the campy obscenity of the stag film than to traditional fashion photography, wherein even happy and lighthearted feelings have to be embodied and then staged seriously and professionally by the model.

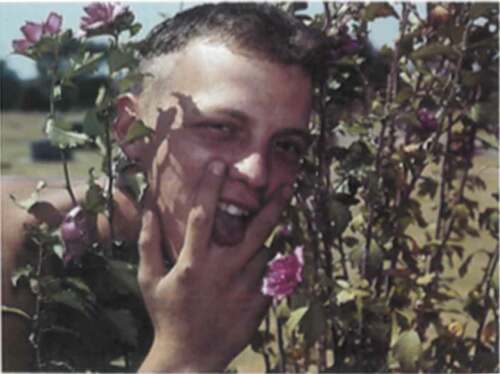

In , a boy is simulating with his hands the act of male-to-female oral sex, making what is also known as a “vagface.” He is sticking his head through the branches of a plant, perhaps peeking at his female counterpart from the previous image. The look on his face is tired, or high, and yet, like the woman in the immediately preceding shot, his face shows a naughty expression that is telegraphing the atmosphere of arousal collectively inhabited by the subjects in the spread. Considering the montage of the story, the “vagface” can be read as the sign of a fantasized sexuality in relation to the female models in the photographic sequence. Obscene humour may also signify a release of sexual anxiety and boredom. Conversely, the gesture might be read as a mocking confrontation with the photographers/viewers who are rendered passive as the obscene joke is redirected at them. The entire sequence plays with the presence/absence of the photographers and the viewers in their participation/exclusion from the scene: while at times the subjects look directly at the camera, lending the impression that they are playing around with them/us, in other instances they appear unaware or as though they do not care. This discontinuity produces a disjointed mode of spectatorship wherein the photographic subjects have a higher degree of agency in comparison with conventional fashion stories in which the models appear to be deliberately posing for the camera or engaging with each other. They appear to have the license to re-orchestrate the scene, challenging their interaction with the photographers and reframing the virtual engagement with the magazine reader.

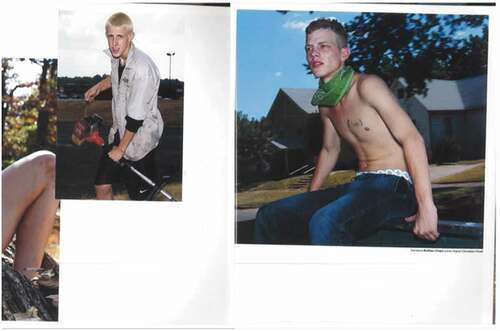

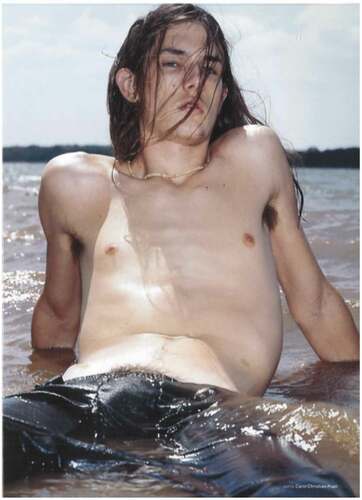

Two other young men in the following shots () match the slim body shapes and the pale skin, reddened by the sun or alcohol, of the female models. They represent the figure of the “juvenile,” another socially despised trash category (Kipnis Citation1997, 130). In this spread the aesthetic of the juvenile boy as it is fabricated in American movies from the 1990s is interlocked with titillating eroticism and humor. The photographic subjects use their bodies to hang out within the pervasively slow, bored temporality that coordinates their lives, separated from the fast pace of capitalist production. Another male model () is portrayed leaning on his arms in the water exhibiting his body in a more calculated pose. There seems to be no humor here, merely the exhibition of a young body with exposed pubic hair. His staged seriousness is somewhat dissonant from the previous images. This affective modality of serious and confident self-exposure recurs in other stories in Dutch from the same years, wherein male subjects whose looks resemble the “trade” boys in Gus Van Sant’s photographs are portrayed like amateur porn actors (as in Steven Klein’s Lone Star photo essay for issue #27 of Dutch in 2000). This male model appears one last time in the last two shots of the photo story (). Here he shows the photographers/viewers his naked butt as he gestures a “fuck you” with both his hands; the picture overlaps a close-up, extended over nearly the entirety of the double page, of his legs and erect penis emerging from the water. This confrontational gesturality can be taken as a coherent epilogue of the erotico-political bluntness of the story.

Obscenity as political gesture

The affective salience of the scene constructed by Hay and Parsons lies in its reduction to bareness, or rawness (as I have already remarked, there are barely any clothes) in its confrontational attitude toward the consumer and the external world more broadly. Bareness could also be rephrased here as de-glamorization. Glamour is indeed taken on in the poses and is caricatured by bodies that create a theatrics of trash exerting no materialist seduction. In the unglamorous decadent setting in which these subjects are hanging out, their performance of glamour, if any at all, may be occurring only in the guise of parody. The subjects are indeed unglamorous and vulgar. The very ostentation of their bodies makes the glamorous context of fashion imagery and the production and consumption practices that materialize its existence appear problematic and possibly even ridiculous: that is, they bring out the ridiculous artificiality of fashion imagery by acting ridiculous themselves. They do so by turning into spectacle all that is normally abjured in fashion photography in order for glamour to flow out.

If mainstream fashion photography is one among many vehicles for the transmission of commodified feelings and the shaping of a public intimacy bound together by an aesthetic rhetoric of optimistic affect, this photo spread proposes a visual imagery of “inappropriate” affects that questions the very social, cultural, and economic function of the fashion photographic medium within the context of the creative industry. It is indeed in the setting of this last that capitalism constructs forms of “parasexuality” (Bailey Citation1990) that employ glamour as an aesthetic tool of cultural management and profit-making. Glamour operates in the liminal space of sexuality and a-sexuality, producing containable pleasure and therefore encouraging publics-consumers to experience desire within boundaries. The photo spread that I am examining here, instead, exceeds such boundaries and counteracts glamour with obscene foolishness.

Obscenity, as Lauren Berlant and Elizabeth Freeman have written in regard to 1990’s queer zines, is valuable political speech that often relies on affronting or negating its audience in order to exert political force, inducing the viewers to question where they are culturally and politically situated. Gestures of parody, for instance, demonstrate a disinvestment in the logics of the nation and violate its normative forms, ultimately claiming “to be out beyond the censoring imaginary of the state” (Berlant and Freeman Citation1992, 177–180). Thus, the hyper-awareness of the models-characters’ bodies sustains their aesthetic strategy of embracing nudity straightforwardly thereby translating the trash body that is often held in contempt by the culture at large into a powerful instrument of dissent. Via their gestural mediality, these bodies suggest the possibility of effecting what Stallybrass calls “transgression,” or counter-sublimation, which he defines as the “undoing [of] the discursive hierarchies and stratifications of bodies and cultures which bourgeois society has produced as the mechanism of its symbolic dominance” (Citation1986, 200–201). In Memory the pornographic idiom expressed in the gestures of the subjects can be seen as a form of political speech that scorns the seriousness and uptightness of high and/or mainstream culture.

Historically, profanities have constituted a genre of communication excluded from the spheres of official culture and speech since it purported to break norms of decorum (Bakhtin Citation[1968] 1984). The core principle of profanities is the display of the free possibilities of the material body, namely its openness and abjection. Profanatory aesthetic forms unveil “the bodily participation in the potentiality of another world”; they uncover “the potentiality of an entirely different world, of another order, another way of life” (Bakhtin, 48). By bringing visibility to the materiality of the body, life might emerge as a collective force and, to use Agamben’s terminology, might be reconquered for the use of the people. Profanations can thus be understood as aesthetically “low” forms of collectivizing affectivity that debase the urgency of self-fulfillment. In their gesturality, they disclose the common human potential of experiencing life with a sense of unpredictable curiosity that the atomization and privatization of the bodies preclude (Bakhtin, 376).

The models in Memory provoke, challenge, and enrich the gestural economy of the fashion photograph by showcasing the body’s constitutive unboundedness, its freedom. It is indeed the affective mediality, in the form of gestural profanation, of the models’ bodies that brings into being the possibility of its functioning as a countercultural and political critique against social hierarchies as well as normative values and sensibilities. The disalignment from prescriptive modes of looking and living bears a queer anticipatory potential insofar as it unfolds the possibility of the otherwise with regard to one’s comportment and social interactions. In Memory the feminine bodies dominate the scene, while the male subjects appear to be embracing a supine disempowered position. Ultimately, the feminine bodies are “obscenely” marked by class in a feminist attempt to offer a carnal aesthetic response to idealizing or sanitizing paradigms for the representation of women’s bodies in fashion imagery.

Light seriousness is, conventionally, the mode of address through which values, ideas, and meanings are distributed via the commercial fashion magazine: the fashion content has to be promoted and circulated with both verbal and visual discourses composing an aesthetic repertoire that is concomitantly easily legible, aspirational, and authoritative. It is the balancing of lighthearted escapism, commodity fetishization, and desire for self-transformation that most likely provides pleasure in the reader. In Memory, instead, the characters counteract the very humorlessness which professional fashion models typically embody as an affective bodily tactic to exert credibility and, ultimately, desire in the viewer. Memory manifests the possibility of expressing unconstrained erotic impulses and discomposure in the pages of a fashion magazine as well as generating discomfiture, and possibly even laughter, in the reader.

Memory encodes a mode of spectatorship that is removed from the viewing habits, bound as they are to patterns of consumption, that are associated with the practice of reading fashion magazines. It is typical of how Dutch created scenes of unfamiliarity and discomfort in order to lure its audience into becoming alert to the strange, the ambiguous, the non-transparent and to incite them to reconceive of fashion magazine reading as a practice guided by the willingness to be disoriented and reoriented, in one’s affective attachments, toward ideas and bodies that eclipsed the parameters of the fashionable. By giving a platform to characters who were, in varied ways, disenfranchised from the world of capital, the magazine enticed its readers to actively contest bodily constraints and moral expectations as well as to consider new modes of socialization.

In addition to the symbolic and political meaning of the models’ gestures, the photographers’ undertaking can be read as profaning the very representational conventions of fashion photography. Firstly, the wide-open suburban space they have chosen as a location for the photo shoot challenges the “metronormativity” (Halberstam Citation2005, 36), or “visual metro norms” (Herring Citation2006, 220), that, alternated with the occasional far-flung exotic location, has historically contributed to the construction of the cultural imaginary of fashion. Secondly, the photographers’ operation consists in making the readers of the magazine join in the publicness of the photographed subjects not as much by way of identification but by sympathy and allegiance with their bodily freedom and humorous expressivity. What is staged is a gag that mocks fashion as industry and system (in which both cultural producers and consumers participate).

Conclusion

The models’ shameless gesturality in Memory is displayed “in your face” with non-aspirational looks and poverty of clothing as a means to expose simultaneously the subtle violence of the expectations that are normally placed on the models’ bodies and, conversely, the models’ openness to being freely re-staged, with the aim of reclaiming for themselves the original (potential and virtually indeterminate) “use” of their own bodies, a use which the industry heavily restricts through a grammar of poses and moods. Here I am echoing Agamben in his assertion that the apparatuses of the fashion show and the pornography industry compromise the value of the mediality of the models’ bodies by diverting them “from their possible use” (Citation2005, 91–92). Through the provocative mediality of their gestures, they lift the veil of the repressive artificiality of practices of glamour. The “white trash” subjects in this photo spread, via acts of replication and collective mimicry, are poking at the mainstream identities commodified by the fashion industry and advanced capitalist economies more extensively. It is Agamben’s contention that the specificity of the image is its own ability to crystallize gestures and to become a gesture itself. This is what, I suggest, happens with this photo story, and I have evinced what the mediality of the models’ gestures reveals on the level of the hierarchies of visuality and representation.

The Dutch photo shoot under examination in this article proposes an oppositional politics against socially accepted ways of being and acting in the world as well as a destabilization of conventional spectatorial modes of looking at fashion stories. More precisely, the aesthetic construction of white trash in the photo spread turns the spectacle of its seductive “otherness” into an arresting staging of alternative self-representation and subversive politics. By stressing the complex entanglement of race, class, and sexuality in possibly generating disturbance in the spectatorial engagement with the images as well as in the social order, I have construed the models’ bodily gestures both as pure affective mediality and as a critique of the outside world that considers “white trash” bodies disposable.

On the one hand, I have sought to demonstrate how fashion photographic representations might solicit modes of spectatorship beyond mere disinterested aesthetic appreciation and toward considerations of one’s own subjectivity and attunement to other bodies; on the other, I have proposed that the gestural mediality of bodies may enable feelings of social exclusion and unbelonging to be converted into an obscene, shameless, profanatory attitude toward the outside that could serve to interrogate and, ideally, alter the hierarchical relational dynamics between differently marked bodies. The heightened affective expressivity of the “white trash” characters in Memory demonstrates the ability of the fashion image to undermine itself: that is, to challenge the fashion system (intended as a capitalist infrastructure) as well as the aspirational liberal, individualistic fantasies of wealth, health, and self-improvement that it animates.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Alexei Hay and Justine Parsons for their kind permission to reproduce their work here. I am grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful and generous comments, as well as to Glyn Davis, Chris Breward, Carole Jones, and Ilya Parkins for offering feedback on early drafts of this essay.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Roberto Filippello

Roberto Filippello has recently obtained his PhD and is currently working on his first book project. His research investigates the politics of queer representation in the visual cultures of fashion. He lectures and publishes on queer theory, fashion media, and LGBTQ activism.

Notes

1. As Nancy Isenberg underscores, “Class has never been about income or financial worth alone. It has been fashioned in physical—and yes, bodily—terms.” (Citation2016, 315).

2. According to Agamben, the act of forceful separation that extirpates the object from its original use or space is most evidently exercised over our bodies, for instance through society’s tabooing of bodily functions. In this sense, a return to and embracing of the “naturality” of our bodily functions can easily generate parody. The task, for Agamben, is to collectively invent new modes of use of those very acts and objects of which we have been symbolically deprived.

3. In a strikingly similar location, Hay shot Margaret Grantner the following year (2001) for issue #32 of Dutch. There the model, with an unkempt look and disheveled hair, exposes her breasts and her scratched up legs from under a Chanel suit. She is captured in the woods, with a lake in the background. She is alternately sitting on a rock or on a tree branch—in sexually awkward poses which closely recall those in Memory—and flirting with the camera. Curiously, scratches are also visible on the models’ legs in some of the shots under examination here: a presumable hint at raunchy outdoor sex.

4. Abjection, according to Kristeva, “is a composite of judgement and affect, of condemnation and yearning, of signs and drives” (Citation1982, 10).

5. This erotic subversion of the sitting can be seen in virtually the entirety of Juergen Teller’s fashion work, which most likely influenced Hay and Parsons in the late 1990s-early 2000s. A recent example by Teller is a photo shoot in the countryside with Kim Kardashian for System magazine in 2015. Here, the celebrity appears to oddly improvise sexy poses as she wears the same outfit (a champagne bustier, a cream bodysuit, black thigh-highs and leather boots) in every shot. She stands next to some farm equipment, climbs up a mount of rubble, or leans down amidst the hay. These ridiculous, and perhaps intentionally caricatural, stills, mix seriousness and awkwardness. A similar yet zanier and much more active eroticism can be seen in the non-professional fashion models of Memory.

References

- Agamben, G. 1990. The Coming Community. Translated from the Italian by M. Hardt. Minneapolis MI: University of Minnesota Press.

- Agamben, G. 2000. Means without End: Notes on Politics. Translated from the Italian by C. Casarino and V. Binetti. Minneapolis MI: University of Minnesota Press.

- Agamben, G. 2000. Potentialities: Collected Essays in Philosophy. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

- Agamben, G. 2005. Profanations. Translated from the Italian by J. Fort. New York: Zone Books.

- comment

- Agamben, G. 2015. The Use of Bodies. Translated from the Italian by A. Kotsko. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

- Aletti, V. 2000. The Photography of Alexei Hay Fashion Victor.” Artforum International, October, 130.

- Bailey, P. 1990. “Parasexuality and Glamour: The Victorian Barmaid as Cultural Prototype.” Gender & History 2 (2): 148–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0424.1990.tb00091.x

- Bakhtin, M. [1968] 1984. Rabelais and His World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Berlant, L. 2007. “Nearly Utopian, Nearly Normal: Post-Fordist Affect in La Promesse and Loretta.” Public Culture 19 (2): 273–301. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2006-036.

- Berlant, L., and E. Freeman. 1992. “Queer Nationality.” Boundary 2 19 (1): 149–180. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/303454.

- Bérubé, A. 1997. “Sunset Trailer Park.” In White Trash: Race and Class in America, edited by M. Wray and A. Newitz, 15–39. New York: Routledge

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, Translated by R. Nice. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

- Brown, E. H. 2012. “From Artist’s Model to the ‘Natural Girl’: Containing Sexuality in Early-Twentieth-Century Modelling.” In Fashioning Models: Image, Text and Industry, edited by J. Entwistle and E. Wissinger, 37–55. Berg: New York.

- Brown, E. H. 2017. “Queering Glamour in Interwar Fashion Photography: The “Amorous Regard” of George Platt Lynes.” GLQ 23 (3): 289–326. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-3818429.

- Church Gibson, P. 2014. “Pornostyle: Sexualized Dress and the Fracturing of Feminism.” Fashion Theory 18 (2): 189–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.2752/175174114X13890223974588.

- Church Gibson, P., and V. Karaminas. 2014. “Letter from the Editors.” Fashion Theory 18 (2): 117–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.2752/175174114X13890223974425.

- Cohen, C. J. 1997. “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?.” GLQ 3: 437–465. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-3-4-437.

- Colman, D. 2000. “Our Cameras, Our Selves.” New York Magazine. Available at: http://nymag.com/nymetro/shopping/fashion/features/1942/ (Accessed: 14 February 2018)

- Dyer, R. 1997. White. London: Routledg

- Elias, N. 1978. The Civilizing Process, Vol. 1 (The History of Manners). Translated from the German by E. Jephcott. New York: Pantheon

- Evans, C. 2003. Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity, and Deathliness. New Haven CT: Yale University Press.

- Evans, C. 2013. The Mechanical Smile: Modernism and the First Fashion Shows in France and America, 1900-1929. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Filippello, R. 2019. ““On Queer Neutrality: Disaffection in the Fashion Photo Story ‘Paradise Lost’.” Criticism 61 (3): 335–357. doi:https://doi.org/10.13110/criticism.61.3.0335.

- Halberstam, J. 2005. In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. New York: NYU Press.

- Hartigan, J. 2005. Odd Tribes: Toward a Cultural Analysis of White People. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Herring, S. 2006. “Caravaggio’s Rednecks.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 12 (2): 217–236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-12-2-217.

- Herring, S. 2014. “’Hixploitation’ Cinema, Regional Drive-Ins, and the Cultural Emergence of a Queer New Right.” GLQ 20 (1–2): 95–113. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2370378.

- Isenberg, N. 2016. White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America. New York: Viking.

- Jefferson, M. 1988. “Slumming: Ain’t We Got Fun.” Vogue, March, 344–347.

- Kipnis, L. 1997. “White Trash Girl.” In White Trash: Race and Class in America, edited by M. Wray and A. Newitz, 113–130. New York: Routledge.

- Kristeva, J. 1982. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, Translated by L. S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Muñoz, J. E. 2013. “Gimme Gimme This … Gimme Gimme That: Annihilation and Innovation in the Punk Rock Commons.” Social Text 31 (3): 95–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-2152855.

- Negri, A. 1999. “Value and Affect.” Boundary 2. Translated by Michael Hardt. 26 (2): 77–88.

- Newitz, A. 1997. “White Savagery and Humiliation, or A New Racial Consciousness in the Media.” In White Trash: Race and Class in America, edited by M. Wray and A. Newitz, 131–152. New York: Routledge.

- Noland, C., and S. A. Ness. 2008. Migrations of Gesture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Patrick, A. 2004. “A Taste for Excess: Disdained and Dissident Forms of Fashioning Femininity.” PhD thesis, University of Stirling.

- Penley, C. 1997. “Crackers and Whackers: The White Trashing of Porn.” In White Trash: Race and Class in America, edited by M. Wray and A. Newitz, 89–112. New York: Routledge.

- Spindler, A. 1993.“Trash Flash.” New York Times, September 12: 10.

- Stallybrass, P., and A. White. 1986. The Politics and Poetics of Transgression. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Sweeney, G. 1997. “The King of White Trash Culture: Elvis Presley and the Aesthetics of Excess.” In White Trash: Race and Class in America, edited by M. Wray and A. Newitz, 249–266. New York: Routledge.

- Teunissen, J. 2015. “Introduction.” In Everything but Clothes: The Connection between Fashion Photography and Magazines, edited by J. Teunissen, Arnhem: ArtEZ Press and Terra Lannoo, 6–15.

- Waters, J. [1981] 2005. Shock Value: A Tasteful Book about Bad Taste. Philadelphia: Running Press.

- Waugh, T. 1996. Hard to Imagine: Gay Male Eroticism in Photography and Film from Their Beginnings to Stonewall. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Wissinger, E. 2007. “Modelling a Way of Life: Immaterial and Affective Labour in the Fashion Modelling Industry.” Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization 7 (1): 250–269.

- Wray, M. 2006. Not Quite White: White Trash and the Boundaries of Whiteness. Durham: Duke University Press.