ABSTRACT

Background: The most used questionnaires for PTSD screening in adults were developed in English. Although many of these questionnaires were translated into other languages, the procedures used to translate them and to evaluate their reliability and validity have not been consistently documented. This comprehensive scoping review aimed to compile the currently available translated and evaluated questionnaires used for PTSD screening, and highlight important gaps in the literature.

Objective: This review aimed to map the availability of translated and evaluated screening questionnaires for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for adults.

Methods: All peer-reviewed studies in which a PTSD screening questionnaire for adults was translated, and which reported at least one result of a qualitative and /or quantitative evaluation procedure were included. The literature was searched using Embase, MEDLINE, and APA PsycInfo, citation searches and contributions from study team members. There were no restrictions regarding the target languages of the translations. Data on the translation procedure, the qualitative evaluation, the quantitative evaluation (dimensionality of the questionnaire, reliability, and performance), and open access were extracted.

Results: A total of 866 studies were screened, of which 126 were included. Collectively, 128 translations of 12 different questionnaires were found. Out of these, 105 (83.3%) studies used a forward and backward translation procedure, 120 (95.2%) assessed the reliability of the translated questionnaire, 60 (47.6%) the dimensionality, 49 (38.9%) the performance, and 42 (33.3%) used qualitative evaluation procedures. Thirty-four questionnaires (27.0%) were either freely available or accessible on request.

Conclusions: The analyses conducted and the description of the methods and results varied substantially, making a quality assessment impractical. Translations into languages spoken in middle- or low-income countries were underrepresented. In addition, only a small proportion of all translated questionnaires were available. Given the need for freely accessible translations, an online repository was developed.

HIGHLIGHTS

We mapped the availability of translated PTSD screening questionnaires.

The quality of the translation and validation processes is very heterogenous.

We created a repository for translated, validated PTSD screening questionnaires.

Antecedentes: Los cuestionarios más usados para el tamizaje del TEPT en adultos fueron desarrollados en inglés. Aunque muchos de esos cuestionarios fueron traducidos a otros idiomas, los procedimientos usados para traducirlos y para evaluar su confiabilidad y validez no han sido documentados consistentemente. Esta revisión exploratoria general buscó compilar los cuestionarios traducidos y evaluados actualmente disponibles para el tamizaje del TEPT y resaltar brechas importantes en la literatura.

Objetivo: Esta revisión tuvo por objetivo mapear la disponibilidad de cuestionarios de tamizaje traducidos y evaluados para el trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT) en adultos.

Métodos: La literatura fue buscada utilizando Embase, MEDLINE y APA PsycInfo, búsqueda de citaciones y contribuciones de los miembros del equipo de estudio. No hubo restricciones respecto al idioma objetivo de las traducciones. Se extrajeron datos respecto al procedimiento de traducción, la evaluación cualitativa, la evaluación cuantitativa (dimensionalidad del cuestionario, confiabilidad y rendimiento) y acceso abierto. Todos los estudios revisados por pares en los cuales un cuestionario de tamizaje del TEPT para adultos fue traducido, y que reportaron al menos un resultado de un procedimiento de evaluación cualitativo y/o cuantitativo.

Resultados: Se evaluó un total de 866 estudios, de los cuales 126 fueron incluidos. En forma colectiva, se encontró 128 traducciones de 12 diferentes cuestionarios. De estos, 105 estudios (83.3%) utilizaron un procedimiento de traducción hacia adelante y hacia atrás, 120 (95.2%) evaluaron la confiabilidad del cuestionario traducido, 60 (47.6%) la dimensionalidad, 49 (38.9%) el rendimiento, y 42 (33.3%) utilizaron procedimientos de evaluación cualitativos. Treinta y cuatro cuestionarios (27.0%) estaban disponibles libremente o accesibles bajo petición.

Conclusiones: Los análisis conducidos y la descripción de los métodos y resultados varió sustancialmente, haciendo impráctica una evaluación de calidad. Las traducciones a idiomas hablados en países de ingresos medios o bajos estuvieron sub-representadas. Adicionalmente, sólo una pequeña proporción de todos los cuestionarios traducidos estaba disponible. Dada la necesidad de traducciones disponibles libremente, se desarrolló un repositorio en línea.

目的:本综述旨在确定成人创伤后应激障碍 (PTSD) 的翻译和评估筛查问卷的可用性。

简介:最常用的成人 PTSD 筛查问卷是用英语开发的。尽管其中许多问卷被翻译成其他语言,但用于翻译和评估其可靠性和有效性的程序并没有得到一致的记录。这项全面的范围界定综述旨在汇编目前可用的 PTSD 筛查翻译和评估问卷,并突出文献中的重要不足。

纳入标准:所有翻译了成人 PTSD 筛查问卷,并报告了至少一项定性和/或定量评估程序结果的同行评议研究。

方法:使用 Embase、MEDLINE 和 APA PsycInfo、引文搜索和研究团队成员的贡献对文献进行搜索。翻译的目标语言没有限制。提取翻译程序、定性评价、定量评价(问卷的维度、可靠性和表现)和开放获取的数据。

结果:共筛选出866项研究,纳入了126项。总共找到了 12 份不同问卷的 128 份翻译。其中,105 项 (83.3%) 研究使用正向和反向翻译程序,120 项 (95.2%) 评估了翻译问卷的可靠性,60 项 (47.6%)含维度,49 项 (38.9%) 含表现,42 (33.3%)使用定性评估程序。 34 份问卷 (27.0%) 可免费获得或应要求提供。

讨论:所进行的分析以及对方法和结果的描述差异很大,使得质量评估不可实操。中等或低收入国家使用的语言翻译版本不足。此外,只有一小部分翻译后的问卷可用。鉴于需要免费获取翻译,开发了一个在线存储库。

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Screening for symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is essential when working with trauma-exposed individuals in clinical as well as research settings. Most commonly, screening is undertaken with the help of a questionnaire either completed by or administered to the individual who is being assessed. In clinical settings, these screening measures are often used to identify those likely to meet a PTSD diagnosis, while in research settings, they are used in a variety of study designs for example in epidemiological studies to assess the prevalence of PTSD in populations (Schlenger et al., Citation2002; Terhakopian et al., Citation2008).

The purpose of screening measures is to be a brief, easy to administer instrument which reliably distinguish between individuals with and without PTSD. However, a screening measure is not designed to obtain a definitive, but only a probable diagnosis, which needs to be clinically verified. Therefore, screening measures can but do not have to comprise items corresponding to the diagnostic criteria of PTSD. In addition, they could include any item, which is predictive of a probable PTSD diagnosis and can effectively be assessed in the target scenario, in which the screening measure is assumed to be applied (for more details see Brewin, Citation2005). Over the last few decades, a multitude of PTSD screening questionnaires have been developed (Brewin Citation2005). Differences between these questionnaires include differences in diagnostic criteria sets for PTSD (e.g. as defined by the fourth or the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; DSM-IV, DSM-5; [O‘Donnell et al., Citation2014] or eleventh edition of the International Classification of Diseases; ICD-11), the number of items included (e.g. assessing all symptoms of PTSD (Blanchard et al., Citation1996) vs only a few symptoms (Connor & Davidson, Citation2001), different target populations (e.g. refugees [Mollica et al., Citation1992] or veterans [Yarvis et al., Citation2012]), different settings (e.g. clinic [Duek et al., Citation2020], or community [Kilpatrick et al., Citation2013]) and constructs assessed (e.g. only symptoms of PTSD [Foa et al., Citation1997] vs broader sequelae of trauma [Oe et al., Citation2020]). Many of these measures were developed in English and in high-income countries, most commonly in the United States of America. Psychological trauma, however, affects individuals all around the globe, including many who do not live in high-income countries and are not native English speakers (Benjet et al., Citation2016). Therefore, screening for symptoms of PTSD in these diverse settings requires either new, context-specific screening measures or translations of existing questionnaires (Beaton et al., Citation2000; Bullinger et al., Citation1998)]. In both cases, the ability of the questionnaire to reliably measure symptoms of PTSD in the specific context is essential for ensuring the clinical utility and validity of the research in which this questionnaire is utilized. Otherwise, if the measures are inadequate, this risks the misdiagnosis of PTSD, the inaccurate assessment of symptom severity, biased estimates of prevalence rates, compromised comparisons across regions or ethnic groups and unreliable results for use in meta-analyses (van de Vijver and Tanzer Citation2004). Furthermore, in clinical settings, unreliable screening tools may result in individuals affected by PTSD not receiving adequate treatment.

The translation of an existing questionnaire is an expensive, and time-consuming process. Historically, such translations have unfortunately often been handled ad hoc and were poorly documented and often have been inadequately evaluated (Chassany et al., Citation2002). Over the last decade, multiple guidelines, frameworks, and best-practice summaries that can guide the translation of questionnaires have been developed (Acquadro et al., Citation2008). Across all different guidelines, it is emphasized that a mere word-to-word translation of a questionnaire is insufficient to ensure reliability and validity in a target population and that cultural aspects of the target population also need to be taken into account, especially given that the trans-cultural validity of PTSD itself is a subject of ongoing debate (Hinton and Lewis-Fernández Citation2011; Gilmoor et al., Citation2019; Hall Citation2020). Yet, the recommended procedures differ substantially and indicate a lack of consensus regarding the procedures required to utilize a reliable translation.

Given the importance of PTSD screening questionnaires for clinicians, public health experts and researchers globally, free access to translated, accurate and reliable questionnaires is essential. Several literature reviews have discussed the availability of PTSD screening questionnaires beyond a US context (Ali et al., Citation2016; Beidas et al., Citation2015; Gagnon and Tuck (Citation2004). Beidas and colleagues (2015) systematically reviewed the literature for freely available, validated, standardized screening questionnaires for mental disorders for adults in low-resource settings (Beidas et al., Citation2015). Their review also included five questionnaires assessing symptoms of PTSD in English (Beidas et al., Citation2015). However, they did not assess whether these questionnaires had been translated from English into other languages. In another systematic review, Ali et al., Citation2016) provided an overview of brief screening tools for the detection of common mental disorders, including PTSD, that were validated in low- and middle-income countries (Ali et al., Citation2016). Importantly, they aimed to assess the diagnostic accuracy against a recognized gold standard diagnostic interview. Regarding PTSD screening questionnaires, 13 studies investigating a total of 10 different questionnaires were identified, with some studies assessing the accuracy of a translated version, while others assessed the accuracy of the original, English version. Evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of translated screening questionnaires is not commonly done as part of the translation process. Hence, the review likely excluded many studies reporting on the translation of a PTSD screening questionnaire. In a third systematic review, Gagnon and Tuck (Citation2004) aimed to determine the best questionnaires for assessing multiple outcomes, including PTSD, in refugee women (Gagnon and Tuck Citation2004). The study reported on the properties of seven different scales. Of these, the highest number of validation studies, namely 14, were reported for the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ; Mollica et al., Citation1992). However, their review was limited to a specific subpopulation, namely refugee women.

Notwithstanding these reviews, a comprehensive overview of the available translated PTSD screening questionnaires for different populations is currently lacking. This is problematic for two main reasons. First, without an overview, gaps in the literature are difficult to address. Notably, a lack of translated questionnaires constitutes an important hurdle for clinicians and researchers. Furthermore, it seems likely that PTSD screening questionnaires are less available for non-English speaking populations in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income countries. This is particularly a disadvantage for trauma-affected individuals, clinicians, and researchers who do not live in high-income countries, creating further barriers to research and treatment in these contexts. Second, systematic investigations (e.g. such as a systematic review) prerequire enough available information to ensure that the research question of interest can be addressed with the current literature. Regarding translations of PTSD questionnaires, no overview of the relevant literature exists. In addition, the above outlined reviews identified few studies investigating the performance of a translated PTSD questionnaire (Ali et al., Citation2016) or had to forgo the reliability and validity assessment due to very heterogeneous outcome reporting (Beidas et al., Citation2015). Hence, the information to plan a systematic review which would answer a specific quality-related question is currently lacking and not the goal of this review.

We aim to provide a broad overview of the existing literature of PTSD screening questionnaires translated from English to other languages, as well as the evaluation process of these translations. Therefore, neither a quality appraisal of the existing translated questionnaires, nor recommendations regarding the use of specific questionnaires are goals of this scoping review (Arksey & O‘Malley, Citation2005; Nyanchoka et al., Citation2019; Peters et al., Citation2020).

1.2. Review question

The objective of this scoping review is to map the global availability of evaluated non-English versions of PTSD screening questionnaires for adult populations. Our definition of a non-English version is one that has been translated from English to another language independent of whether additional steps were undertaken to adapt and evaluate a questionnaire to a target population or not. Because we aim to map the available translations of PTSD screening questionnaires and expect that few translations have undergone a formal evaluation procedure, we define evaluated questionnaires as questionnaires on which any kind of information about their translation technique as well as their accuracy is provided in a peer-reviewed journal article. Therefore, some of the included questionnaires might not be evaluated in a formal sense (e.g. performance might be only assessed by correlating the total score to another PTSD questionnaire’s total score). More information about the conducted evaluation procedures will be provided for each study (see below). The aims of this review are twofold: First, to identify published, peer-reviewed PTSD screening questionnaires that were translated to at least two different languages. The decision to only cover peer-reviewed, published studies as well as to exclude questionnaires with less than two translations, was made to limit the scope of this review, to ensure its feasibility and to include a criterion reflecting the use of a given questionnaires across a minimal number of different language groups. The second aim is to map all evaluated translations of the screening questionnaires identified in step one in terms of translation techniques used, results from the qualitative and/or quantitative evaluations, and accessibility of the translated questionnaires.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

The aim of a scoping review is to map existing evidence on a prespecified topic. In contrast to systematic reviews, scoping reviews are more exploratory and cover a broader spectrum of evidence (Peters et al., Citation2020). This scoping review will be conducted in accordance with the methodological framework for scoping reviews proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (Peters et al., Citation2015; Peters et al., Citation2020). This framework is based upon earlier work by Arksey and O‘Malley (Citation2005) and Levac and colleagues (Levac et al., Citation2010). The reporting will follow the guidance of the extension of the ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses’ for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., Citation2018).

2.2. Consultation

Several actions were taken to ensure adequate consultation from relevant stakeholders. First, the study team was assembled specifically to include researchers with a diverse background regarding gender, profession, cultural context, and geographical location. Second, all members of the research team will consult with local and international contacts (personal and professional). Third, the project was designed to be published as a registered report. Registered reports follow a two-phase publishing model (Nosek and Lakens Citation2014; Nosek et al., Citation2018). In a first phase, the authors only submit documents outlining the importance of the question they want to investigate and a detailed study plan including information about the proposed methodological approach and study design. These documents will then be reviewed by independent peers who can suggest modifications to all aspects of the submitted documents (including the study design, the measures etc.). If the study is deemed to investigate a relevant question in an appropriate manner, an ‘in-principle acceptance’ is granted meaning that the final manuscript (including the results and their discussion) will be published after the completion of the study, regardless of what the results show (Nosek et al., Citation2018; Simons et al., Citation2014). Due to this publishing model, independent peer-reviewers, will be consulted before the review will be conducted.

2.3. Review registration

The initial protocol including the appendices were revised upon the suggestions made by the reviewers during the first-phase review process. Following journal guidelines on registered reports, after the revised manuscript and the protocol were accepted ‘in-principle,’ the revised protocol was deposited and time-stamped here: https://osf.io/ud8hc. We used the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io), an open-source platform maintained by the Center for Open Science, a non-profit technology organization.

2.4. Eligibility criteria

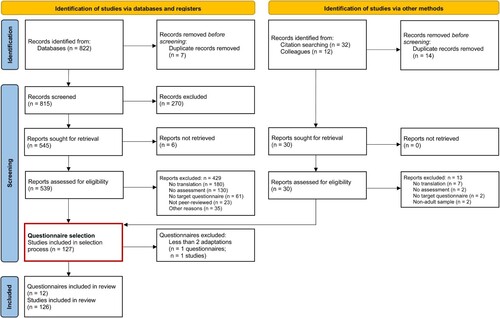

To ensure the feasibility of this review, its scope will be limited to PTSD screening questionnaires that were translated at least two different times. Two translations may include translations into different language (e.g. French, Arabic, Spanish), different versions or dialects within a given language (e.g. Levantine Arabic, Egyptian Arabic, Modern Standard Arabic), and different translations within the same language and dialect (e.g. Somali translations that differ based on translation team). Therefore, the inclusion of records is conducted in a two-step process which is shown in (which is an adaption of the PRISMA flow diagram; Page et al., Citation2021). In a first step, we will systematically search for peer-reviewed articles containing information on the translation of PTSD screening questionnaires for adults. A list with all translations for each questionnaire will be prepared. In a second step, all questionnaires for which less than two translations have been identified, will be removed prior to the data extraction. For all questionnaires that were adapted to account for revised PTSD diagnostic criteria (e.g. with one version assessing DSM-IV and a later version assessing DSM-5 criteria), the cumulative number of adaptations (across all versions of the questionnaires) will be assessed. If this cumulative number is five or higher, all versions of the questionnaires will be included in the data extraction process. The eligibility criteria for both steps are defined following the Population, Concept, Context (PCC) framework as follows:

Figure 1. Flow of information through different phases of the review, detailing in- and excluded papers.

Populations: This review focuses on translations of screening questionnaires developed for adult populations (≥ 18 years). No additional restrictions are imposed for the inclusion of populations (e.g. no restrictions regarding language, gender, country of origin, study site, whether the population was an epidemiological or clinical sample etc.).

Concept: The overarching concept of interest for this review is to map the availability of translated and evaluated PTSD screening questionnaires commonly used in traumatic stress research and/or in clinical practice. The following aspects of the concept of interest are discussed in depth: (a) PTSD, (b) screening questionnaire, (c) translation and/or cultural adaptation (d) evaluation.

PTSD: For the purpose of this review, questionnaires developed to assess PTSD as defined by either the fourth, the text-revised fourth or the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV, DSM-IV-TR, DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) or the tenth or eleventh edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10, ICD-11; World Health Organization, Citation1992) are considered.

Screening questionnaire: In accordance with the systematic review of PTSD screening instruments for adults by Brewin, screening questionnaires were defined as consisting of less than 30 items (not including the items assessing the types of trauma experienced or witnessed (Brewin, Citation2005). A list outlining the questionnaires that will be included in the first step is provided in Appendix I (Supplemental data).

Translation: The translation of a questionnaire to a new population is a resource-intensive and complex process (Sousa & Rojjanasrirat, Citation2011). For this review, we consider all studies that include at least one translation of a PTSD screening questionnaire from English to any other language. Each new translation, independent from the number of preexisting translations into the same target language, will be counted as one translation. In contrast, studies that adapted a questionnaire to a population without translating it will be excluded from this review.

Evaluation: The translation process of a questionnaire should include an evaluation of the questionnaire’s properties, including its reliability and validity (Boateng et al., Citation2018). For this review, only studies that report information about the translation procedure as well as results from a performance assessment are considered for inclusion. Consequently, articles that state that a questionnaire was translated, but do not report some results information regarding what translated questionnaires exist as well as the evaluation procedure they have undergone and not to answer a specific question (e.g. regarding the quality the included translations). Therefore, we will collect information about the evaluation of the translated questionnaires (e.g. whether the reliability of the questionnaire was assessed) but not the quality of the included studies (e.g. the reported sensitivity and specificity). Consequently, to cover the presumably very heterogeneous literature, we will include studies with any kind of information on the questionnaire’s performance, even if this information was gained using non-standard practices.

Context: We will consider studies with no restrictions regarding the context in which they were conducted.

Types of evidence sources: Only peer-reviewed, published studies reporting quantitative and qualitative results of the evaluation of the adapted questionnaire will be considered. Such studies can include but are not limited to the following designs: epidemiological study, experimental study, and cross-sectional studies. Qualitative studies and any kind of study not reporting quantitative or qualitative results of the evaluation of the adapted questionnaire(s) will not be considered for this review.

Languages: Articles published in English, German, Spanish, French, Chinese, Filipino and Hebrew will be included.

Date range. The publication date range will not be limited. However, the definitions of PTSD considered for this review are limited to the DSM-IV, DSM-IV-TR, DSM-5, ICD-10, and ICD-11, of which the DSM-IV was introduced in 1994 and the ICD-10 in 1990.

2.5. Search strategy

Our search strategy for the identification of articles of interest rests upon four main pillars to ensure coverage of the index, but also of the grey literature. First, we will conduct a systematic search of three electronic bibliographic databases: Embase, MEDLINE, and APA PsycInfo. Second, we will search the reference list of relevant review articles (Ali et al., Citation2016; Beidas et al., Citation2015; Gagnon and Tuck Citation2004). Third, all members of our research team, of whom some have several decades of experience translating and adapting questionnaires, will be asked to provide articles of interest from their personal archives. Fourth, we will search PTSDpubs (formerly PILOTS), a curated database covering literature on PTSD.

The search strategy for the bibliographic databases was developed in several steps. Initially, a limited search of MEDLINE was conducted to identify relevant articles. Index terms and relevant words from the identified articles’ titles and abstracts were obtained. Next, the search strategies of existing systematic reviews (Beidas et al., Citation2015; Boateng et al., Citation2018; Gagnon and Tuck Citation2004) were analysed. Subsequently, a search strategy was developed by three authors (JH, FS & TS), and reviewed by the remaining authors as well as by an experienced librarian. We will search Embase, MEDLINE, and APA PsycInfo; using OVID. The final search strategy is presented in Appendix II (Supplemental data).

2.6. Source of evidence selection

Following the search, all citations identified through each pillar of the search strategy will be exported into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation Citation2022). First, duplicates will be removed. Second, titles and abstracts of all remaining citations will be screened by a pair of independent reviewers against the inclusion criteria. The list with inclusion and exclusion criteria used by the reviewers is presented in Appendix III (Supplemental data). All abstracts deemed to meet inclusion criteria by at least one reviewer will be included in the review. Third, potentially relevant records will be fully retrieved. Again, a pair of reviewers will independently assess the records against the inclusion criteria. All articles deemed to meet inclusion criteria by at least one reviewer will be included in the review. Following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines (Tricco et al., Citation2018), the results of the search, the records inclusion process, and reasons for the exclusion of records during the full-text review will be recorded and reported. At the beginning of the evidence selection process, 25 randomly sampled records will be selected, and each will be screened by all reviewers. Afterwards, the results will be compared, and disagreements discussed. Based on this discussion, the document providing clarifications to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Appendix III, Supplemental data) will be revised. All articles deemed to meet inclusion criteria by at least one reviewer will be included in the review.

2.7. Data extraction

The data extraction process will be guided by a data extraction form and conducted by a pair of reviewers using Covidence, adhering to the JBI Manual for Evidence (Peters et al., Citation2020). Any disagreements between the two reviewers during data extraction will be resolved by a third reviewer. If more than a total number of 30 studies are identified, data extraction will be conducted by one reviewer only to ensure feasibility of the review. In this case, accuracy of the extracted data they will be verified by an additional reviewer. Any disagreements will be resolved by a third reviewer.

2.8. Data of interest and data extraction form

The data of interest aimed to be extracted from individual records can be grouped into three categories: (a) Study characteristics, (b) Translation and evaluation, and (c) Access.

Study characteristics: For each record, the following data will be assessed:

Translation and evaluation: As outlined above, multiple recommendations and guidelines for the translation of existing questionnaires exist (Acquadro et al., Citation2008). Still, very few studies have tested how different translation processes affect the validity of the corresponding translations (e.g. Perneger et al., Citation1999). Therefore, we only aim to map whether some basic steps regarding the translation procedures and performance testing of the resulting questionnaires were undertaken. For this purpose, we use the following three dimensions:

Translation.

Access. We will assess whether the source and the adapted questionnaires are freely available for clinical or research purposes. A questionnaire will be considered freely accessible, when it can either be freely accessed on the internet with a reasonable amount of effort (e.g. questionnaires only included in the supplementary materials of paywalled articles are not considered freely accessible) or can be requested from the authors with responses including the questionnaire within four weeks (also see Appendix V, Supplemental data).

A draft of the extraction form is provided in Appendix IV (Supplemental data). The data extraction form will be implemented with instructions into Covidence. The data extraction process will be piloted using five randomly selected full-text records which will be assessed by the involved data extraction reviewers. Disagreements will be discussed, and the extraction form will be revised as necessary with any resulting modifications explicitly stated in the resulting scoping review.

2.9. Deviations from the protocol

We report one deviation from the protocol. The search terms outlined in the protocol to be used in Embase and APA PsycInfo were missing an additional specifier included in the search terms for MEDLINE. Thus, we expanded the preregistered search terms (instead of ‘exp posttraumatic stress disorder’ they also included ‘or (ptsd or posttraumatic stress or post traumatic stress or trauma or traumatic) mp.’) for these two databases to increase consistency across all searched databases. However, this deviation only broadened the search criteria and did therefore not jeopardize the preregister aim of this scoping review.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

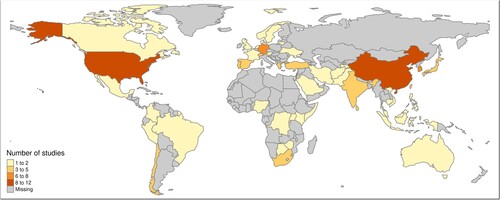

The flow through the study selection process is shown in . We identified 822 studies using our search strategy. An additional 32 studies were found by citation searching, and 12 were sent to us by colleagues. Thereof, 740 studies were excluded during the screening process, leaving 126 studies for extraction. The full screening details, including causes for exclusion, are shown in . Interrater reliability for each of the three pairs of reviewers who reviewed titles, abstract, and fulltexts was between fair and substantial (Cohen’s κ 0.28, 0.58, and 0.61, respectively).

3.2. Study characteristics

The details of the included studies are outlined in . Two of the 126 studies evaluated 2 questionnaires, so that from a total of 128 source questionnaires, 12 different PTSD screening measures were included, namely: The PTSD Checklist (PCL; n = 23; 18.0%); the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ; n = 21; 16.4%); the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R; n = 21; 16.4%); the PTSD Checklist for the DSM-5 (PCL-5; n = 15; 11.7%); the International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ; n = 14; 10.9%); the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS; n = 13; 10.2%); the Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS; n = 7; 5.5%); the Global Psychotrauma Screen (GPS; n = 3; 2.3%); the PTSD Symptom Scale-Interview (PSS-I; n = 3; 2.3%); the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire for DSM-5 (HTQ-5; n = 2; 1.6%); the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale-5 (PDS-5; n = 2; 1.6%); the Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD: n = 2; 1.6%); and the Trauma Screening Questionnaire (TSQ; n = 2; 1.6%). Most studies evaluated the translations in civilian populations (n = 89; 70.6%), followed by forcibly displaced (n = 25; 19.8%), post-conflict/veteran (n = 10; 7.9%), and mixed (n = 3; 2.4%) populations. Study settings were clinical (n = 38; 30.2%), community (n = 74; 58.7%), emergency departments (n = 5; 4.0%), and mixed settings (n = 10; 7.9%). Sample sizes ranged from 18 to 7034 participants. Countries in which studies were conducted can be seen in . The most common target languages were Arabic (n = 16), Spanish (n = 14), Chinese (n = 8), German (n = 7), Korean (n = 5), and French (n = 5); with all other languages ranging from 2–4 translations.

Table 1. Study characteristics.

3.3. Translation, evaluations and availability

Eighty-three per cent (n = 105) of studies described using a forward and back translation procedure. Regarding the evaluation of translated questionnaires, 95.2% of studies (n = 120) used quantitative reliability analyses (e.g. internal consistency, test-retest reliability, inter-rater reliability, etc.), 47.6% (n = 60) used quantitative dimensionality evaluations (e.g. confirmatory factor analysis, bifactor modelling, measurement invariance testing), 38.9% (n = 49) used quantitative performance analyses (e.g. diagnostic accuracy, correlation with another screening questionnaire) and 33.3% (n = 42) used qualitative methods (e.g. pilot testing of the adapted questionnaire, qualitative interviews, face validity). Regarding the availability of the translated questionnaires, 17 (13.5%) questionnaires are freely available online, 5 (4.0%) were made freely available online by their authors after being contacted by the study team, and in 12 (9.5%) cases the authors stated that they are willing to share the questionnaires upon request. We were unable to obtain 92 (73.0%) of all questionnaires for different reasons (e.g. the authors declined or did not respond to our request). For a more detailed description of the results see and the Supplementary Materials.

4. Discussion

The objective of this scoping review was to map the global availability of translations of evaluated PTSD screening questionnaires for adult populations. This was achieved by (1) identifying published, peer-reviewed screening questionnaires that were translated in at least two different languages, and (2) mapping these questionnaires across translation techniques, qualitative and quantitative evaluation procedures, and accessibility of translated questionnaires. This scoping review identified 12 PTSD screening questionnaires that had undergone at least two translations and evaluations from English into another language.

The breadth of the questionnaires identified in this review covers definitions of PTSD according to the DSM-IV, the DSM-5, and the ICD-11. While the 12 questionnaires identified in this review represent a broad sample of PTSD screening questionnaires, if this list is limited to current definitions (i.e. DSM-5 or ICD-11), many fewer questionnaires were identified (specifically HTQ-5, PDS-5, PCL-5, ITQ). The target languages included in this review highlight the diversity of translations and gaps to be addressed. The most frequent translations comprised targeted languages such as Arabic, Spanish, Chinese, German, Korean, and French. While these are dominant languages spoken in multiple countries, they tend to represent the dominant languages spoken in high income countries, and/or the language of the most dominant migrant groups that reside in those countries. The over-representation of high-income countries in target languages is reflected when viewing the geographic locations in which these studies were conducted. These include the USA, China, Germany, and Korea, while relatively fewer studies were conducted in parts of Africa, South America, Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East. These findings are not surprising, given that most research funding comes from high income countries. However, for clinicians and researchers residing in low- and middle-income countries, the lack of available non-English screening questionnaires poses major challenges (e.g. when accurate PTSD screening is needed to make important decisions regarding triaging patients or allocating resources). While most of the world’s population resides in lower- and middle-income countries, mental health resources in these contexts are limited (Saxena et al., Citation2007). Amplifying this problem, is that only a small fraction (n = 34, 27.0%) of all identified questionnaires are freely available online or upon request from the developers. These inequities in research funding and resources may exacerbate the disparity in global mental health and mental health research. More global partnerships are needed to provide valid translations of PTSD screening questionnaires to reduce this gap.

The utility of translated PTSD screening questionnaires is highly dependent upon the quality of the translation. In this review, most studies reported using forward and blind-back translation procedures, according to best practice (Acquadro et al., Citation2008). However, the reporting on this process, such as the qualifications of the translators, how discrepancies were reconciled and/or the use of expert panels to review the final translation, varied substantially across different studies. In many instances, it was unclear if the translation process was conducted by the authors themselves, or was completed in an alternate study. Indeed, the lack of descriptions around translation processes precludes a more systematic review of the literature. Greater transparency and more standardized documentation of the translation process will be important to establish, as the utility of screeners is dependent upon linguistic accuracy. Equally important in the translation process is the evaluation of the translated questionnaire. The most frequently reported evaluation in this scoping review was quantitative reliability analyses. In most cases this was using Cronbach’s alpha, with only a few studies implanting methods such as test-retest analyses. Less than 40% of studies evaluated the diagnostic performance of the translated questionnaire. It is also worth noting that less than 34% of studies reported qualitative methods which includes basic practices such as investigating the face validity of the questionnaire. Given that direct translations may often not convey the appropriate information, utilizing and reporting this form of evaluation is crucial for ensuring that meaning is retained, rather than only relying on statistical methods. These results indicate that there was substantial variability regarding the reported evaluation procedures. It is worth noting that 132 studies were excluded during screening because they did not include any form of evaluation. Guidelines are needed on baseline evaluation requirements for translation use, in addition to more studies in which the primary aim is to evaluate the diagnostic utility of translated questionnaires.

While the translation and evaluation process of PTSD screening questionnaires can be costly and burdensome (Acquadro et al., Citation2008), this burden could be alleviated by making translations freely available for research and clinical use. For example, given that permission has been obtained from the authors of the original questionnaire, translated versions could be published alongside the article describing the translation and evaluation procedures. To disseminate the results from this review and increase access for clinicians and researchers, we created a website (https://tobiasrspiller.github.io/PTSD-Screener-Repo/) that provides global access to translated PTSD screening questionnaires. On this website, questionnaires can be downloaded or requested from the developers and the relevant studies are linked so that the developers can be credited appropriately. Moreover, the website also highlights gaps in the literature.

While this review aimed to map the availability of translated and evaluated PTSD screening questionnaires, some limitations should be noted. First, it was not the aim of this review to provide a quality assessment of each translated questionnaire. Information around translation is often lacking, precluding an assessment of this kind. Similarly, the review does not make recommendations on psychometric validity of the questionnaire. Rather, the aim was to present an overview in order to provide information for researchers and clinicians to make their own decisions. Second, to ensure feasibility of the review we planned to exclude all questionnaires that were translated only once. Following this preregistered protocol, we excluded the Short Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Rating Interview (SPRINT), the only questionnaire for which we found less than two translations. This cut-off was partially arbitrary, as was the list of the included questionnaires, both not covering all existing questionnaires and translations. Future studies should aim to map these uncovered gaps, for example, questionnaires that were developed in a language other than English. Finally, this study only examined English questionaries that were translated into a target language. Therefore, there may have been non-English PTSD questionnaires that have been developed, which were outside the scope of this review.

To conclude, while the results identified 12 translated PTSD questionnaires, more transparency is needed around translation processes, and more rigorous evaluation methods are needed to ensure the utility of these measures in clinical and research contexts. Furthermore, more investment is needed in developing high quality translations of PTSD screening questionnaires in countries and language groups that have thus far been neglected. As the majority of existing translations were not accessible, more avenues for freely accessible translations of PTSD questionnaires are urgently needed. Making translations available in an online repository will hopefully help eliminate the need for duplicate translations and create space for more rigorous validation studies to be made widely available.

Competing interests

The authors do not report competing interests.

Supplemental Material

Download Rich Text Format File (1.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.4 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (39.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (9.7 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (53.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

All relevant data is included in the supplement.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acarturk, C., McGrath, M., Roberts, B., Ilkkursun, Z., Cuijpers, P., Sijbrandij, M., Sondorp, E., Ventevogel, P., McKee, M., & Fuhr, D. C. (2021). Prevalence and predictors of common mental disorders among Syrian refugees in Istanbul, Turkey: A cross-sectional study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(3), 475–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01941-6

- Acquadro, C., Conway, K., Hareendran, A., & Aaronson, N. (2008). Literature review of methods to translate health-related quality of life questionnaires for use in multinational clinical trials. Value in Health, 11(3), 509–521. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00292.x

- Akerblom, S., Perrin, S., Rivano Fischer, M., & McCracken, L. M. (2017). The impact of PTSD on functioning in patients seeking treatment for chronic pain and validation of the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 24(2), 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-017-9641-8

- Al-Turkait, F. A., & Ohaeri, J. U. (2014). Exploratory factor analysis of the eysenck personality questionnaire and the hopkins and post-traumatic stress checklists. Clin Exp Med Lett, 55, 56–65. https://doi.org/10.12659/MST.892175

- Alghamdi, M., & Hunt, N. (2020). Psychometric properties of the Arabic posttraumatic diagnostic scale for DSM-5 (A-PDS-5). Traumatology, 26(1), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000204

- Alhalal, E., Ford-Gilboe, M., Wong, C., & AlBuhairan, F. (2017). Reliability and validity of the Arabic PTSD checklist civilian version (PCL-C) in women survivors of intimate partner violence. Research in Nursing & Health, 40(6), 575–585. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21837

- Ali, G.-C., Ryan, G., & De Silva, M. J. (2016). Validated screening tools for common mental disorders in Low and middle income countries: A systematic review. PLoS One, 11(6), e0156939. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156939

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorder (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

- Arksey, H. & O'Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Asukai, N., Kato, H., Kawamura, N., Kim, Y., Yamamoto, K., Kishimoto, J., Miyake, Y., & Nishizono-Maher, A. (2002). Reliability and validity of the Japanese-language version of the impact of event scale-revised (IES-R-J): Four studies of different traumatic events. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 190(3), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-200203000-00006

- Bahari, R., Alwi, M. N. M., Ahmad, M. R., & Saiboon, I. M. (2015). Translation and validation of the Malay post traumatic stress disorder checklist for civilians. ASEAN J Psychiatry, 16(2), 203–211.

- Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures: Spine, 25(24), 3186–3191.

- Beidas, R. S., Stewart, R. E., Walsh, L., Lucas, S., Downey, M. M., Jackson, K., Fernandez, T., & Mandell, D. S. (2015). Free, brief, and validated: Standardized instruments for Low-resource mental health settings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.02.002

- Benjet, C., Bromet, E., Karam, E. G., Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Ruscio, A. M., Shahly, V., Stein, D. J., Petukhova, M., Hill, E., Alonso, J., Atwoli, L., Bunting, B., Bruffaerts, R., Caldas-de-Almeida, J. M., de Girolamo, G., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Huang, Y., … Koenen, K. C. (2016). The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: Results from the world mental health survey consortium. Psychological Medicine, 46(2), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001981

- Bentley, J., Ahmad, Z., & Thoburn, J. (2014). Religiosity and posttraumatic stress in a sample of East African refugees. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 17(2), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2013.784899

- Blanc, J., Rahill, G. J., Laconi, S., & Mouchenik, Y. (2016). Religious beliefs, PTSD, depression and resilience in survivors of the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 697–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.046

- Blanchard, E. B., Jones-Alexander, J., Buckley, T. C., & Forneris, C. A. (1996). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(8), 669–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2

- Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6(149).

- Bobes, J., Calcedo-Barba, A., Garcia, M., Francois, M., Rico-Villademoros, F., Gonzales, M. P., & Grupo Espanol de Trabajo para el Estudio del Trastornostres Postraumático. (2000). Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of 5 questionnaires for the evaluation of post-traumatic stress syndrome. Actas Espanolas de Psiquiatria, 28(4), 207–218.

- Bonilla-Escobar, F. J., Fandiño-Losada, A., Martínez-Buitrago, D. M., Santaella-Tenorio, J., Tobón-García, D., Muñoz-Morales, E. J., Escobar-Roldán, I. D., Babcock, L., Duarte-Davidson, E., Bass, J. K., Murray, L. K., Dorsey, S., Gutierrez-Martinez, M. I., & Bolton, P. (2018). Randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral intervention for Afro-descendants’ survivors of systemic violence in Colombia. PLoS One, 13(12), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208483

- Boysan, M., Ozdemir, P. G., Ozdemir, O., Selvi, Y., Yilmaz, E., & Kaya, N. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (PCL-5). Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol, 27(3), 300–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750573.2017.1342769

- Brewin, C. R. (2005). Systematic review of screening instruments for adults at risk of PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(1), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20007

- Brunet, A., St-Hilaire, A., Jehel, L., & King, S. (2003). Validation of a French version of the impact of event scale-revised. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 48(1), 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370304800111

- Bullinger, M., Alonso, J., Apolone, G., Leplège, A., Sullivan, M., Wood-Dauphinee, S., Gandek, B., Wagner, A., Aaronson, N., Bech, P., Fukuhara, S., Kaasa, S., & Ware, J. E. (1998). Translating Health Status Questionnaires and evaluating their quality: The IQOLA Project Approach. 11.

- Caamaño, W. L., Fuentes, M. D., González, B. L., Melipillán, A. R., Sepúlveda, C. M., & Valenzuela, G. E. (2011). Adaptación y validación de la versión chilena de la escala de impacto de evento-revisada (EIE-R). Revista Médica de Chile, 139(9), 1163–1168. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872011000900008

- Calbari, E., & Anagnostopoulos, F. (2010). Exploratory factor analysis of the Greek adaptation of the PTSD checklist-civilian version. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 15(4), 339–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2010.491748

- Carvalho, T., Cunha, M., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Duarte, J. (2015b). Portuguese version of the PTSD checklist-military version (PCL-M)-I: Confirmatory factor analysis and reliability. Psychiatry Research, 226(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.055

- Carvalho, T., Motta, C., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2020). Portuguese version of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Comparison of latent models and other psychometric analyses. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(7), 1267–1282. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22930

- Carvalho, T., Pinto-Gouveia, J., Cunha, M., & Duarte, J. (2015a). Portuguese version of the PTSD checklist-military version (PCL-M)-II: Diagnostic utility. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 37(1), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2013-1319

- Chassany, O., Sagnier, P., Marquis, P., Fullerton, S., & Aaronson, N. (2002). European regulatory issues on quality of life assessment group. Patient-reported outcomes: The example of health-related quality of life—a European guidance document for the improved integration of health-related quality of life assessment in the drug regulatory process. Drug Information Journal, 36(1), 209–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/009286150203600127

- Chen, C. H., Lin, S. K., Tang, H. S., Shen, W. W., & Lu, M. L. (2001). The Chinese version of the Davidson trauma scale: A practice test for validation. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 55(5), 493–499. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1819.2001.00895.x

- Cheung, A., Makhashvili, N., Javakhishvili, J., Karachevsky, A., Kharchenko, N., Shpiker, M., & Roberts, B. (2019). Patterns of somatic distress among internally displaced persons in Ukraine: Analysis of a cross-sectional survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(10), 1265–1274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01652-7

- Choi, H., Kim, N., & Lee, A. (2021). ICD-11 posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD among organized violence survivors in modern south Korean history of political oppression. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 34(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1839889

- Christen, D., Killikelly, C., Maercker, A., & Augsburger, M. (2021). Item response model validation of the German ICD-11 international trauma questionnaire for PTSD and CPTSD. Clin Psychol Eur, 3, e5501. https://doi.org/10.32872/cpe.5501

- Chukwuorji, J. C., Ifeagwazi, C. M., & Eze, J. E. (2017). Role of event centrality and emotion regulation in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among internally displaced persons. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 30(6), 702–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2017.1361936

- Cohen, M. H., Fabri, M., Cai, X., Shi, Q., Hoover, D. R., Binagwaho, A., Culhane, M. A., Mukanyonga, H., Davis, K. K., & Anastos, K. (2009). Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in HIV-infected and at-risk Rwandan women. Journal of Women's Health, 18(11), 1783–1791. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2009.1367

- Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. T. (2001). SPRINT: A brief global assessment of post-traumatic stress disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 16(5), 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004850-200109000-00005

- Costa-Requena, G., & Gil, F. (2010). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in cancer: Psychometric analysis of the Spanish posttraumatic stress disorder checklist-civilian version. Psycho-oncology, 19(5), 500–507. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1601

- de Faria Cardoso C., Ohe, N. T., Taba, V. L., Paiva, T. T., Baltatu, O. C., & Campos, L. A. (2021). Cross-Cultural adaptation, reliability, and validity of a Brazilian of short version of the posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 614554. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.614554

- De Fouchier, C., Blanchet, A., Hopkins, W., Bui, E., Ait-Aoudia, M., & Jehel, L. (2012). Validation of a French adaptation of the harvard trauma questionnaire among torture survivors from sub-Saharan African countries. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.19225

- Donat, J. C., Lobo, N. S., Jacobsen, G. S., Guimaraes, E. R., Kristensen, C. H., Berger, W., Mendlowicz, M. V., Lima, E. P., Vasconcelos, A. G., & Nascimento, E. (2019). Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the international trauma questionnaire for use in Brazilian Portuguese. Sao Paulo Medical Journal, 137(3), 270–277. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-3180.2019.0066070519

- Duek, O., Spiller, T. R., Pietrzak, R. H., & Fried, E. I. (2020). Harpaz-rotem I. Network analysis of PTSD and depressive symptoms in 158,139 treatment-seeking veterans with PTSD. Depression and Anxiety, 38(5), 554–562. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23112.

- Ertl, V., Pfeiffer, A., Saile, R., Schauer, E., Elbert, T., & Neuner, F. (2010). Validation of a mental health assessment in an African conflict population. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 318–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018810

- Fawzi, M. C. S., Pham, T., Lin, L., Nguyen, T. V., Ngo, D., Murphy, E., & Mollica, R. F. (1997). The validity of posttraumatic stress disorder among Vietnamese refugees. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 10(1), 101–108. 10.1023/A:1024812514796

- Fernando, G. A. (2008). Assessing mental health and psychosocial status in communities exposed to traumatic events: Sri Lanka as an example. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78(2), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013940

- Finkelstein, M. (2016). Resource loss, resource gain, PTSD, and dissociation among Ethiopian immigrants in Israel. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 57(4), 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12295

- Foa, E. B., Cashman, L., Jaycox, L., & Perry, K. (1997). The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Psychological Assessment, 9(4), 445–451. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.9.4.445

- Fung, H. W., Chan, C., Lee, C. Y., & Ross, C. A. (2019). Using the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) checklist for DSM-5 to screen for PTSD in the Chinese context: A pilot study in a psychiatric sample. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 16(6), 643–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/26408066.2019.1676858

- Gagnon, A., & Tuck, J. (2004). A systematic review of questionnaires measuring the health of resettling refugee women. Health Care for Women International, 25(2), 111–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330490267503

- Gargurevich, R., Luyten, P., Fils, J. F., & Corveleyn, J. (2009). Factor structure of the impact of event scale-revised in two different Peruvian samples. Depression and Anxiety, 26(8), E91–E98. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20430

- Ghezeljeh, T. N., Ardebili, F. M., Rafii, F., & Hagani, H. (2013). Translation and psychometric evaluation of Persian versions of burn specific pain anxiety scale and impact of event scale. Burns, 39(6), 1297–1303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2013.02.008

- Gilbar, O., Hyland, P., Cloitre, M., & Dekel, R. (2018). ICD-11 complex PTSD among Israeli Male perpetrators of intimate partner violence: Construct validity and risk factors. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 54, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.01.004

- Gilmoor, A. R., Adithy, A., & Regeer, B. (2019). The cross-cultural validity of post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic stress symptoms in the Indian context: A systematic search and review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10(439). https://doi.org/10/gh4pxz

- Grassi, M., Pellizzoni, S., Vuch, M., Apuzzo, G. M., Agostini, T., & Murgia, M. (2021). Psychometric properties of the Syrian Arabic version of the impact of event scale-revised in the context of the Syrian refugee crisis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 34(4), 880–888. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22667

- Griesel, D., Wessa, M., & Flor, H. (2006). Psychometric qualities of the German version of the posttraumatic diagnostic scale (PTDS). Psychological Assessment, 18(3), 262–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.18.3.262

- Halcon, L. L., Robertson, C. L., Savik, K., Johnson, D. R., Spring, M. A., Butcher, J. N., Westermeyer, J. J., & Jaranson, J. M. (2004). Trauma and coping in Somali and Oromo refugee youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.005

- Hall, B. J. (2020). Assessment of PTSD in Non-western cultures. In J. G. Beck, & D. M. Sloan (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of traumatic stress disorders (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Hall, B. J., Yip, P. S. Y., Garabiles, M. R., Lao, C. K., Chan, E. W. W., & Marx, B. P. (2019). Psychometric validation of the PTSD checklist-5 among female Filipino migrant workers. Eur J Psychotraumatology, 10, 1571378.

- Hansen, M., Vaegter, H. B., Cloitre, M., & Andersen, T. E. (2021). Validation of the Danish international trauma questionnaire for posttraumatic stress disorder in chronic pain patients using clinician-rated diagnostic interviews. Eur J Psychotraumatology, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1880747

- Hearn, M., Ceschi, G., Brillon, P., Furst, G., & Van der Linden, M. (2012). A French adaptation of the posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne des Sciences du Comportement, 44(1), 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025591

- Hecker, T., Barnewitz, E., Stenmark, H., & Iversen, V. (2016). Pathological spirit possession as a cultural interpretation of trauma-related symptoms. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8(4), 468–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000117

- Hecker, T., Huber, S., Maier, T., & Maercker, A. (2018). Differential associations among PTSD and complex PTSD symptoms and traumatic experiences and postmigration difficulties in a culturally diverse refugee sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(6), 795–804. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22342

- Hem, C., Hussain, A., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Heir, T. (2012). The Norwegian version of the PTSD Checklist (PCL): Construct validity in a community sample of 2004 tsunami survivors. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 66(5), 355–359. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2012.655308

- Hinsberger, M., Sommer, J., Kaminer, D., Holtzhausen, L., Weierstall, R., Seedat, S., Madikane, S., & Elbert, T. (2016). Perpetuating the cycle of violence in South African low-income communities: Attraction to violence in young men exposed to continuous threat. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7(1), https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v7.29099

- Hinton, D. E., & Lewis-Fernández, R. (2011). The cross-cultural validity of posttraumatic stress disorder: Implications for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety, 28(9), 783–801. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20753

- Hinton, D. E., Pich, V., Marques, L., Nickerson, A., & Pollack, M. H. (2010). Khyal attacks: A key idiom of distress among traumatized Cambodia refugees. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 34(2), 244–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-010-9174-y

- Hinton, D. E., Pollack, A. A., Weiss, B., & Trung, L. T. (2018). Culturally sensitive assessment of anxious-depressive distress in Vietnam: Avoiding category truncation. Transcultural Psychiatry, 55(3), 384–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461518764500

- Ho, G. W. K., Hyland, P., Shevlin, M., Chien, W. T., Inoue, S., Yang, P. J., Chen, F. H., Chan, A. C. Y., & Karatzias, T. (2020). The validity of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD in East Asian cultures: Findings with young adults from China, Hong Kong, Japan, and Taiwan. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11, 1717826. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1717826

- Ho, G. W. K., Karatzias, T., Cloitre, M., Chan, A. C. Y., Bressington, D., Chien, W. T., Hyland, P., & Shevlin, M. (2019). Translation and validation of the Chinese ICD-11 International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) for the assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD (CPTSD). European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10, 1608718. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1608718

- Hocker, A., & Mehnert, A. (2012). Posttraumatic stress in cancer patients: Validation of the German version of the PTSD checklist-civilian version (PCL-C). Posttraumatische Belast Bei Krebspatienten Validierung Dtsch Version Posttraumatic Stress Disord Checkl-Civ Version PCL-C, 21(2), 68–79. https://doi.org/10.3233/ZMP-2012-210003

- Hollander, A.-C., Ekblad, S., Mukhamadiev, D., & Muminova, R. (2007). The validity of screening instruments for posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and other anxiety symptoms in Tajikistan. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 195(11), 955–958. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e318159604b

- Housen, T., Lenglet, A., Ariti, C., Ara, S., Shah, S., Dar, M., Hussain, A., Paul, A., Wagay, Z., Viney, K., Janes, S., & Pintaldi, G. (2018). Validation of mental health screening instruments in the kashmir valley, India. Transcultural Psychiatry, 55(3), 361–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461518764487

- Huang G, Zhang Y, Xiang H. (2006) The Chinese version of the impact of event scale-revised: Reliability and validity. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 20(1), 28–31.

- Hyland, P., Ceannt, R., Daccache, F., Abou Daher, R., Sleiman, J., Gilmore, B., Byrne, S., Shevlin, M., Murphy, J., & Vallières, F. (2018). Are posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex-PTSD distinguishable within a treatment-seeking sample of Syrian refugees living in Lebanon? Glob Ment Health Camb, 5(e14). https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2018.2

- Ichikawa, M., Nakahara, S., & Wakai, S. (2006). Cross-cultural use of the predetermined scale cutoff points in refugee mental health research. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(3), 248–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0016-2

- Iranmanesh, S., Shamsi, A., & Dehghan, M. (2015). Post-traumatic stress symptoms among Iranian parents of children during cancer treatment. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(4), 279–285. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2014.983622

- Jaapar, S. Z. S., Abidin, Z. Z., & Othman, Z. (2014). Validation of Malay Trauma Screening Questionnaire. Internal Medicine Journal, 21, 536–538. https://doi.org/10.21315/mjms2018.25.6.13

- Jang, Y. J., Kang, S. H., Chun, H. G., Choi, J. H., Kim, T. Y., & So, H. S. (2016). Application of short screening tools for post-traumatic stress disorder in the Korean elderly population. Psychiatry Investigation, 13(4), 406–412. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2016.13.4.406

- John, P. B., & Russell, P. S. S. (2007). Validation of a measure to assess post-traumatic stress disorder: A Sinhalese version of impact of event scale. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 3, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-0179-3-4

- Jung, Y. E., Kim, D., Kim, W. H., Roh, D., Chae, J. H., & Park, J. E. (2018). A brief screening tool for PTSD: Validation of the Korean version of the primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5 (K-PC-PTSD-5). Journal of Korean Medical Science, 33, e338. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e338.

- Karanikola, M., Alexandrou, G., Mpouzika, M., Chatzittofis, A., Kusi-Appiah, E., & Papathanassoglou, E. (2021). Pilot exploration of post-traumatic stress symptoms in intensive care unit survivors in Cyprus. Nursing in Critical Care, 26(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/nicc.12574

- Kazlauskas, E., Gegieckaite, G., Hyland, P., Zelviene, P., & Cloitre, M. (2018). The structure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD in Lithuanian mental health services. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1414559. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1414559

- Kilpatrick, D. G., Resnick, H. S., Milanak, M. E., Miller, M. W., Keyes, K. M., & Friedman, M. J. (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria: DSM-5 PTSD prevalence. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(5), 537–547. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21848

- King, D. W., Orazem, R. J., Lauterbach, D., King, L. A., Hebenstreit, C. L., & Shalev, A. Y. (2009). Factor structure of posttraumatic stress disorder as measured by the Impact of Event Scale–Revised: Stability across cultures and time. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 1(3), 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016990

- Kleijn, W. C., Hovens, J. E., & Rodenburg, J. J. (2001). Posttraumatic stress symptoms in refugees: Assessments with the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire and the Hopkins symptom Checklist-25 in different languages. Psychological Reports, 88(2), 527–532. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2001.88.2.527

- Klis, S., Velding, K., Gidron, Y., & Peterson, K. (2011). Posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms among people living with HIV in the Gambia. AIDS Care, 23(4), 426–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2010.507756

- Kontoangelos, K., Tsiori, S., Poulakou, G., Protopapas, K., Katsarolis, I., Sakka, V., Kavatha, D., Papadopoulos, A., Antoniadou, A., & Papageorgiou, C. C. (2017). Reliability, validity and psychometric properties of the Greek translation of the posttraumatic stress disorder scale. Mental Illness, 9(1), 6832. https://doi.org/10.4081/mi.2017.6832

- Kruger-Gottschalk, A., Knaevelsrud, C., Rau, H., Dyer, A., Schafer, I., Schellong, J., & Ehring, T. (2017). The German version of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Psychometric properties and diagnostic utility. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1541-6

- Leaman, S. C., & Gee, C. B. (2012). Religious coping and risk factors for psychological distress among African torture survivors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(5), 457–465. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026622

- Leiva-Bianchi, M. C., & Araneda, A. C. (2013). Validation of the davidson trauma scale in its original and a new shorter version in people exposed to the F-27 earthquake in Chile. Eur J Psychotraumatology, 4, 21239. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.21239

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O‘Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Lhewa, D., Banu, S., Rosenfeld, B., & Keller, A. (2007). Validation of a Tibetan translation of the hopkins symptom checklist-25 and the harvard trauma questionnaire. Assessment, 14(3), 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191106298876

- Lim, H.-K., Woo, J.-M., Kim, T.-S., Kim, T.-H., Choi, K.-S., Chung, S.-K., Chee, I.-S., Lee, K.-U., Paik, K. C., Seo, H.-J., Kim, W., Jin, B., & Chae, J.-H. (2009). Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the impact of event scale-revised. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 50(4), 385–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.011

- Malinauskienė, V., & Bernotaitė, L. (2016). The impact of event scale - revised: Psychometric properties of the Lithuanian version in a sample of employees exposed to workplace bullying. Acta Med Litu, 23(3), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.6001/actamedica.v23i3.3384

- Marshall, G. N. (2004). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Checklist: Factor structure and English-Spanish measurement invariance. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17(3), 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTS.0000029265.56982.86

- Martínez-Levy, G. A., Bermúdez-Gómez, J., Merlín-García, I., Flores-Torres, R. P., Nani, A., Cruz-Fuentes, C. S., Briones-Velasco, M., Ortiz-León, S., & Mendoza-Velásquez, J. (2021). After a disaster: Validation of PTSD checklist for DSM-5 and the four- and eight-item abbreviated versions in mental health service users. Psychiatry Research, 305, 114197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114197

- Mayer, Y., Ilan, R., Slone, M., & Lurie, I. (2020). Relations between traumatic life events and mental health of Eritrean asylum-seeking mothers and their children‘s mental health. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 105244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105244

- McDonald, S. E., Im, H., Green, K. E., Luce, C. O., & Burnette, D. (2019). Comparing factor models of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with Somali refugee youth in Kenya: An item response theory analysis of the PTSD checklist-civilian version. Traumatology, 25(2), 104–114. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000175

- Mendoza, N. B., Mordeno, I. G., Latkin, C. A., & Hall, B. J. (2017). Evidence of the paradoxical effect of social network support: A study among Filipino domestic workers in China. Psychiatry Research, 255, 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.037

- Mollica, R. F., Caspi-Yavin, Y., Bollini, P., Truong, T., Tor, S., & Lavelle, J. (1992a). The harvard trauma questionnaire: Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 180(2), 111–116. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199202000-00008

- Mollica, R. F., Caspi-Yavin, Y., Bollini, P., Truong, T., Tor, S., & Lavelle, J. (1992b). The harvard trauma questionnaire: Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 180(2), 111–116. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199202000-00008

- Morales Miranda, C. (2006). Evaluación de la escala de trauma de davidson: Estandarización de la escala de trauma de davidson (DTS). Temática Psicológica, 2, 31–36.

- Mordeno, I. G., Nalipay, M. J. N., Sy, D. J. S., & Luzano, J. G. C. (2016). PTSD factor structure and relationship with self-construal among internally displaced persons. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 44, 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.10.013

- Mordeno, I. G., Nalipay, M. J. N., Untalan, J. H. C., & Decatoria, J. B. (2014). Examining posttraumatic stress disorder‘s latent structure between treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking Filipinos. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 11, 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2014.05.003

- Murphy, S., Elklit, A., Dokkedahl, S., & Shevlin, M. (2018). Testing competing factor models of the latent structure of post-traumatic stress disorder and complex post-traumatic stress disorder according to ICD-11. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9, e011667. https://doi.org/10/gmgz7w

- Myers, H. F., Wyatt, G. E., Ullman, J. B., Loeb, T. B., Chin, D., Prause, N., Zhang, M., Williams, J. K., Slavich, G. M., & Liu, H. (2015). Cumulative burden of lifetime adversities: Trauma and mental health in low-SES African Americans and Latino/as. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 7(3), 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039077

- Mystakidou, K., Tsilika, E., Parpa, E., Galanos, A., & Vlahos, L. (2007). Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale in Greek cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 33(4), 454–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.023

- Nickerson, A., Bryant, R. A., Schnyder, U., Schick, M., Mueller, J., & Morina, N. (2015). Emotion dysregulation mediates the relationship between trauma exposure, post-migration living difficulties and psychological outcomes in traumatized refugees. Journal of Affective Disorders, 173, 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.043

- Nickerson, A., Byrow, Y., O‘Donnell, M., Mau, V., McMahon, T., Pajak, R., Li, S., Hamilton, A., Minihan, S., Liu, C., Bryant, R. A., Berle, D., & Liddell, B. J. (2019). The association between visa insecurity and mental health, disability and social engagement in refugees living in Australia. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1688129. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1688129

- Norris, A. E., & Aroian, K. J. (2008). Assessing reliability and validity of the Arabic language version of the post-traumatic diagnostic scale (PDS) symptom items. Psychiatry Research, 160(3), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2007.09.005

- Nosek, B. A., Ebersole, C. R., DeHaven, A. C., & Mellor, D. T. (2018). The preregistration revolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(11), 2600–2606. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708274114

- Nosek, B. A., & Lakens, D. (2014). Registered reports. Social Psychology, 45(3), 137–141. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000192

- Nyanchoka, L., Tudur-Smith, C., Thu, V. N., Iversen, V., Tricco, A. C., & Porcher, R. (2019). A scoping review describes methods used to identify, prioritize and display gaps in health research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 109, 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.01.005

- Odenwald, M., Lingenfelder, B., Schauer, M., Neuner, F., Rockstroh, B., Hinkel, H., & Elbert, T. (2007). Screening for posttraumatic stress disorder among Somali ex-combatants: A validation study. Conflict and Health, 1, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-1-10

- O‘Donnell, M. L., Alkemade, N., Nickerson, A., Creamer, M., McFarlane, A. C., Silove, D., Bryant, R. A., & Forbes, D. (2014). Impact of the diagnostic changes to post-traumatic stressdisorder for DSM-5 and the proposed changes to ICD-11. British Journal of Psychiatry, 205(3), 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.135285

- Oe, M., Kobayashi, Y., Ishida, T., Chiba, H., Matsuoka, M., Kakuma, T., Frewen, P., & Olff, M. (2020). Screening for psychotrauma related symptoms: Japanese translation and pilot testing of the global psychotrauma screen. Eur J Psychotraumatology, 11, 1810893. https://doi.org/10/gjkz46

- Olff, M., Bakker, A., Frewen, P., Aakvaag, H., Ajdukovic, D., Brewer, D., Elmore Borbon, D. L., Cloitre, M., Hyland, P., Kassam-Adams, N., Knefel, M., Lanza, J. A., Lueger-Schuster, B., Nickerson, A., Oe, M., Pfaltz, M. C., Salgado, C., Seedat, S., Wagner, A., … Global Collaboration on Traumatic Stress (GC-TS). (2020). Screening for consequences of trauma – an update on the global collaboration on traumatic stress. Eur J Psychotraumatology, 11, 1752504. https://doi.org/10/gg284k

- Olff, M., Primasari, I., Qing, Y., Coimbra, B. M., Hovnanyan, A., Grace, E., Williamson, R. E., & Hoeboer, C. M. (2021). Mental health responses to COVID-19 around the world. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12, 1929754. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1929754

- Orlando, M., & Marshall, G. N. (2002). Differential item functioning in a Spanish translation of the PTSD checklist: Detection and evaluation of impact. Psychological Assessment, 14(1), 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.14.1.50

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 2021, n71. https://doi.org/10/gjkq9b

- Patel, A. R., Newman, E., & Richardson, J. (2022). A pilot study adapting and validating the harvard trauma questionnaire (HTQ) and PTSD checklist-5 (PCL-5) with Indian women from slums reporting gender-based violence. BMC Women's Health, 22(22). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01595-3

- Patel, A. R., Prabhu, S., Sciarrino, N. A., Presseau, C., Smith, N. B., & Rozek, D. C. (2021). Gender-based violence and suicidal ideation among Indian women from slums: An examination of direct and indirect effects of depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 13(6), 694–702. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000998

- Perera, S., Gavian, M., Frazier, P., Johnson, D., Spring, M., Westermeyer, J., Butcher, J., Halcon, L., Robertson, C., Savik, K., & Jaranson, J. (2013). A longitudinal study of demographic factors associated with stressors and symptoms in African refugees. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 83(4), 472–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajop.12047

- Perneger, T. V., Leplège, A., & Etter, J.-F. (1999). Cross-Cultural Adaptation of a Psychometric Instrument: Two Methods Compared. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 52(11), 1037–1046.

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid Implement, 13(3), 141–146. https://doi.org/10/gdkzzq

- Peters, M. J. V., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C., & Khalil, H. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping reviews (2020 version). In E. Aromataris, & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI.