ABSTRACT

Parents’ experiences and satisfaction with their child’s compulsory school are affected by several factors. Some, such as parents’ education and marital status, are social factors, while others are school factors that local leaders and school personnel can address. Findings build on data from an online questionnaire to parents in 20 compulsory schools in Iceland (n = 2129). Factor analysis generated two factors: communication and teaching. These, together with a question on parents’ overall satisfaction with the school, were used as outcome variables in a regression analysis exploring what influences parents’ satisfaction with the school. The majority of parents were satisfied, which may make it is easy to overlook those who are dissatisfied. Parents who felt that their children had special needs that were not acknowledged in school were more likely to be dissatisfied than other parents. Educational background was also influential. Single mothers were overrepresented in the group of unsatisfied parents; they experienced more difficulties in communicating with school personnel, believed less in the possibility for parents to influence the school, and more frequently experienced that their child’s need for special support was not met in school. The findings imply that equity in Icelandic schools is disputable.

Background

The topic for this article is parental involvement in school in Iceland and the possible factors that influence parents’ satisfaction with school.

Schools are under pressure: International large-scale assessments indicate that schools in most Nordic countries are scoring lower than before, and that schools have become more segregated in terms of students’ academic results (Skolverket, Citation2009, Citation2012). Reports from PISA 2012 show that the within-school variations in student results in Iceland are amongst the highest in the world, although the between-school variations are very small (Halldórsson, Ólafsson, & Björnsson, Citation2013).

In response to pressure instigated by the high-profile PISA results, as well as other social and economic circumstances, compulsory school systems in Nordic countries have been undergoing several structural changes in recent years (Östh, Andersson, & Malmberg, Citation2013; Sahlberg, Citation2011, Citation2015). One aspect focuses on an increased consumer orientation with regards to the educational system. From the Finnish context, Poikolainen and Silmäri-Salo (Citation2015) pointed out that global education policy has brought national education closer to the consumer to whom the educational goods should be available. With reference to the Norwegian context, Bæck (Citation2009) pointed out that parents have been allocated a more significant position in schools, both in regard to decision making and as partners in their children’s learning processes, at least in the formal sense. However, Sahlberg (Citation2011, Citation2014) noted that the ideology of open market-based education has expanded parental choice and school autonomy, but has also introduced stronger measures of control over schools. Sahlberg claimed that the sixth element of the global educational reform movement (GERM) was indeed the increased control of schools. The influence of GERM is also visible in Iceland; for example, in the most recent White paper on educational reform (Mennta- og menningarmálaráðuneytið, Citation2014), where measures and measurable goals for improving schools are described. It is also visible in the yearly plans set forth by school authorities, for example in Reykjavík, where myriad indicators for evaluating school practices are defined (Reykjavíkurborg, Citation2015). At the same time, however, equity and quality are emphasized as important values in the Icelandic educational system. Among other things, this study focuses on how the ideal of equity in education is being challenged through practices connected to parent and school relationships.

Cultural pressure on parents to act in the best interest of their children is stronger in present-day societies than it was in the previous century, as shown by Böök & Perälä-Littunen (Citation2015) in their study of Finnish parents’ views on responsibility in home–school relations. They found that active parental involvement in school life was seen as a key to children’s success. Ultimately, this means that rather than being accepted as they are, children have become the target of all kinds of educative efforts. It is important to remember, however, that success in school is not only about academic achievement. Well-being, social relations, maturity and personal development should also be central success criteria. An Icelandic study showed that parents and school professionals consider these factors to be more important than academic achievement (Björnsdóttir & Jónsdóttir, Citation2014). Yet, the expectations for better academic achievement are pervasive in modern societies and put pressure on all parties, including students, teachers and school administrators – and increasingly also on parents.

It is a common belief that parents contribute best to their children’s success in compulsory school by participating in school-related activities, and this has been repeatedly supported in international research literature (Desforges & Abouchaar, Citation2003; Hattie, Citation2009, Citation2012; Jeynes, Citation2005, Citation2011a). However, this traditional image of what good home–school cooperation should entail has been criticized. For example, Jeynes (Citation2005, Citation2011a) concluded that the most powerful aspects of parental involvement are often subtle, such as maintaining high expectations in children, communicating with them about school, and parental style. Interestingly, Jeynes claimed that an increasing body of research has suggested that the key qualities for fostering parental involvement in schools may also be subtle: ‘Whether teachers, principals, and school staff are loving, encouraging, and supportive to parents may be more important than the specific guidelines and tutelage they offer to parents’ (Jeynes Citation2011b, p. 10).

The relationship between home and school can sometimes be challenging, as reported in a number of studies. Böök and Perälä-Littunen (Citation2015) described discourses where teachers and parents were seen as polar opposites: teachers as experts and parents as laymen. Bæck (Citation2009, Citation2010) described the relationship between home and school as sometimes a distanced one. Similarly, Bæck (Citation2013) and Jónsdóttir and Björnsdóttir (Citation2012) described the relationship between teachers and parents as occasionally stressful. Furthermore, teachers’ opinions of parents are often ambivalent; parents are either a support or a barrier to successful teaching (Rasmussen, Citation2004). As pointed out by Bæck (Citation2009), failing to include parents in important decisions in school may indicate that they are not respected as equal partners. It is important to note that it can be a barrier to parental involvement if teachers do not recognize the social and cultural preconditions that affect participation, and respect the differences in the parent group.

From the Icelandic context, research has shown that parents and school professionals agree that working together is essential for children’s education and academic achievement in school (Jónsdóttir & Björnsdóttir, Citation2012). That does not mean, however, that parental support in education is unproblematic, or even that all parents have the same expectations when it comes to their role in education. Parents should therefore not be viewed as a homogenous group (Bæck, Citation2009), and school culture, and parents’ characteristics such as social status, gender, educational level and cultural values, have a great impact on the rationale and practice of parental involvement (Bæck, Citation2010; Pepe & Addimando, Citation2014). Formal education plays a part in whether and how parents cooperate with school. According to a Norwegian study, parents in lower-secondary schools with more formal education are more likely to take part in home–school cooperation compared to those with less education (Bæck, Citation2009). These parents are also often more likely to acknowledge that parental support is important in education. Findings from an Icelandic study have shown that parents prefer to participate in social activities, rather than, for example, school evaluations or planning students’ studies, and also that more educated parents favour parental involvement more compared to parents with less education (Jónsdóttir, Citation2013; Jónsdóttir & Björnsdóttir, Citation2014). The expectations of schools regarding parental involvement are more likely to match the values, capacities and involvement styles of middle-class parents than those of working-class parents (Bæck, Citation2005). Lareau (Citation2000) showed that working-class parents are often intimidated by the teachers’ professional authority. Parents’ status in society also has an effect: parents of high socio-economic standing are more likely to appreciate the importance of a good education in terms of living a successful adult life (Jeynes, Citation2011a). Parents with more capital and capacity, and who had their own success in school and highly value education, tend to be better able to tackle home–school relationships (Desforges & Abouchaar, Citation2003). As pointed out by Desforges and Abouchaar (Citation2003), the impact of such socio-economic factors can be counteracted by schools and parents through parental involvement in the form of ‘at-home good parenting’. This has proven to have a significant positive effect on children’s achievement and adjustment, even after all other factors shaping attainment have been removed from the equation.

This study explored how parents experienced the relationship with schools, and the way that the previously described background factors affected these relationships. The following research questions were explored:

How do parents experience different aspects of their relationship with school?

Which factors influence parents’ experiences and satisfaction with school?

To what extent is equity a significant quality characterizing home–school relationships in Iceland?

Method

The data was derived from a mixed-methods research project called Teaching and Learning in Icelandic Schools (Óskarsdóttir, Citation2014). The strand of parental involvement within the larger project was concerned with providing an overview of what characterizes a home–school relationship in Icelandic schools, and discovering what parents, school personnel, and teenage students find desirable in parental participation (Jónsdóttir, Citation2013, Citation2015; Jónsdóttir & Björnsdóttir, Citation2012, Citation2014). The main focus of this study was to illuminate the factors influencing parents’ experiences with school.

Participants

Participants were parents of students in 20 compulsory schools. With a sample size of 3481, this comprised parents of 17% of all students in compulsory schools in Iceland (Óskarsdóttir et al., Citation2014). The response rate was 67%, but some participants did not answer the whole questionnaire or skipped some questions. Parents were asked to respond to the questionnaire according to the child that was mentioned in an e-mail invitation, but they were also given the option to write comments concerning the experiences of other children they had in compulsory schools.

For the analysis, only participants who answered all the questions used in the factor analysis were included, which provided a sample size of 2129 (61.2% of the original sample). A comparison of this group with the original sample showed no significant differences when it comes to the following variables: child’s gender (χ2 (1, n = 3481) = 0.04, p = .834), whether the child lived in a single-mother’s household or not (χ2 (1, n = 2878) = 3.00, p = .083), parents’ educational level (χ2 (3, n = 2837) = 1.55, p = .670), whether the child had special needs or not (χ2 (1, n = 3309) = 1.65, p = .199), to what degree the child’s special needs were met by extra support (χ2 (1, n = 3161) = 0.39, p = .530), and bullying (χ2 (6, n = 3099) = 5.76, p = .454).

A significant difference was found between the two samples in four variables: the child’s grade level, parents’ general satisfaction with school, parents’ participation in social events in school, and parents’ assessment of their influence on school decisions. Parents of children scoring at the middle level (grades 5–7) were slightly overrepresented in the new sample. Regarding general satisfaction with school, parents that were either happy or unhappy were better represented than those who were neither happy nor unhappy with school. Parents who participated in social events were overrepresented (χ2 (6, n = 3186) = 66.38, p < .001), as were parents who reported that they experienced being able to influence school decisions and vision (t(2976) = 3.94, p < .001). All in all, the new sample gave a slight overrepresentation of the more involved parents, which should come as no surprise considering that only those parents who completed all the questions in the analysis were included as part of the sample.

Characteristics of the participants are shown in . The great majority (72.1%) of respondents were mothers. Parents were invited to respond to the questionnaire together, and that opportunity was used by 5.6%. The participants noted that 73% of the children lived with both parents during schooldays, while 13.3% lived in single-mother households.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants.

The participants’ answers about their education were recoded into four groups of respondents’ highest educational levels, as shown in . The majority (62.7%) of participants had completed education at the university level, but parents that had only completed compulsory school accounted for 7.8%.

Materials

The questionnaire was developed for parents in 20 compulsory schools in Iceland using guidelines on survey construction (Karlsson, Citation2003; Þórsdóttir & Jónsson, Citation2007). The questionnaire included questions about parents’ opinions on teaching, communication, and cooperation with school staff; students’ well-being and need for support; parents’ general satisfaction with school and their ideas about desirable parent participation. Questions about parents’ background were, for example, about education and family structure. The questionnaire was tested in a pilot study in one compulsory school (Jónsdóttir & Björnsdóttir, Citation2012).

Variables

Three different outcome variables related to different aspects of parents’ satisfaction with their child’s school were used in the analysis. shows an overview of all variables used in the analysis. Two of the outcome variables were generated through a factor analysis of the answers given to a battery of survey questions concerning parents’ experiences. Similar to Bæck (Citation2009), factor analysis was used for data reduction purposes, meaning that a small number of factors were identified to explain as much of the observed variance as possible. Two factors, communication and teaching, presented different aspects of parents’ opinions by exploring their answers to five questions, explaining 72% of the variability in the scores. The factor teaching consisted of two variables that measured how parents evaluated the quality of teaching and assessment their child was receiving at school. The factor communication consisted of three variables measuring the ease of parents’ communication with supervisory teachers, other teachers and school leaders. Oblique factor rotation was used because it is unlikely that the two factors were unrelated, which is a prerequisite for using orthogonal rotation (Field, Citation2013). The third outcome variable was a response to a direct question to the parent group about their general satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their child’s school.

Table 2. Overview of variables used in the analysis (n = 2129).

Procedure

The online survey software Question Pro was used for data collection. The data was collected in the spring of 2011, and parents were sent invitations to participate via e-mail.

The data was analysed with SPSS 24. A multiple regression analysis was performed to provide information on the effect of the explanatory variables on the outcome variables (Gujarati & Porter, Citation2009).

The regression analysis on parents’ satisfaction with school was performed on the two outcome variables produced by the factor analysis, teaching and communication, and on the question about parents’ satisfaction with school. There was no indication of collinearity, with the highest variance inflation factor = 1.093, and tolerance was above .9 for all variables. The variables were deemed suitable for regression following guidelines in Field (Citation2013).

Three regression models were tested for each of the outcome variables. Model 1 included four variables regarding student background: gender, grade in school, whether the child lived in a single-mother household and whether the parent answering the survey had only basic education. In Model 2, two variables about parents’ experience were added: whether the parents participated in social activities at school and whether they felt that they had any influence on school decisions and the school’s vision of the future. In Model 3, two variables regarding the child’s needs and well-being were added: whether the child complained about bullying at school and whether the child received sufficient support at school if parents said that special support was necessary.

Factors that influence parents’ opinions

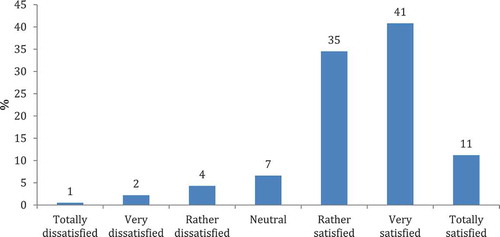

At first glance, the data portrayed parents as a rather homogenous group who were in a happy relationship, and satisfied, with the schools their children attended (see Figure 1). About 52% of parents reported that they were totally or very satisfied with the school; 35% were rather satisfied and 7% were unsatisfied.

As previously mentioned, the factor analysis brought forth two factors, teaching and communication, which showed different aspects of parents’ contentedness with school. Variables predicting these factors, as well as the general satisfaction, indicated differences amongst parents and their opinions in several ways. Parents’ marital status and education explained some of the variability in parents’ opinions. Being active in attending school events and having an opportunity to influence the school were also important. More influential, though, were variables concerning the children, such as grade level in school (age), complaints of bullying, and inadequate support because of special needs. As shown in , multiple regression models were used to examine how these variables influenced the three outcome variables of satisfaction, teaching and communication.

Table 3. Regression analysis on scores of outcome variables.

The results in show that the same variables predicted parents’ general satisfaction with school and their opinions of the quality of teaching and assessment, while the variables that predicted ease of communication were somewhat different.

Three background variables were significant predictors in Model 1 when looking at parents’ satisfaction and quality of teaching. When their children became older, parents grew less satisfied with the school, with parents of boys less content than parents of girls, and single mothers less satisfied than other parents. These variables explained a small but significant part of the variability in general satisfaction (1.7%) and quality of teaching (2.3%).

When two variables concerning parents’ experience were added to create Model 2, the three previous variables still made a significant contribution to the regression model. Frequent participation in social events and activities at school had no significant effect on parents’ general satisfaction, or on how they evaluated the quality of teaching. On the other hand, the feeling of having an influence on the school’s decisions and future vision predicted parents’ general satisfaction. Model 2 explained 11% of the variability in parents’ answers about general satisfaction. The variables in Model 2 had a similar but stronger explanatory power on parents’ opinions of the quality of teaching (R2adj 12.6%).

Two additional variables concerning the child’s well-being and support were added for Model 3, increasing the R2 and adding 10.3% to the explanatory power of the regression model of parents’ satisfaction with school. The two new variables also influenced the contribution of the variables in previous models. In Model 3, it remained significant that parents were less satisfied with school when their child became older, but the child’s gender and living in a single-mother household were no longer significant. Parents’ education levels contributed significantly: parents with more than compulsory education were less content compared to those with less education. The feeling of having an influence was still significant. The two new variables in Model 3 were important: if children complained of bullying, then parents became less satisfied; if parents felt that their child was getting inadequate support because of special needs, their satisfaction with school was substantially lowered. After adding these variables to Model 3, the regression explained 21.3% of the variability in parents’ answers to the question of general satisfaction.

The exact same variables that were significant in the regression model on teaching and in parents’ estimations of the quality of teaching and assessment were significant in the regression on general satisfaction. The explanatory factor, however, was even stronger for all three models in the regression on teaching, and Model 3 explained 25.1% of the variability of parents’ opinions.

The analysis of how easy or difficult it was for parents to communicate with school personnel highlighted influences of the background variables that differed from their influences in the previous regressions. In Model 1, grade level (child age) was not significant; parents of boys had more difficulties with communication than did parents of girls; and single mothers were more likely to experience problems with communication compared to other parents. The explanatory power was significant but small.

Only one of the variables from Model 1 was still significant in Model 2: being a single mother made communication more difficult. Parents that frequently participated in social events and activities at school reported more positive communication. The feeling of having an influence on school decisions and the school’s future vision had an effect on parents’ opinions about communication. Model 2 explained 11.1% of the variability of parents’ ease in communicating with school personnel.

In Model 3, the two variables that were added concerning the child’s well-being and support changed the significance of the variables in previous models. In Model 3, it was still significant that single mothers experienced more difficulties in communicating with school compared to other parents, but the other background variables were not significant. The feeling of having an influence at school and actively participating in social events was still significant for communication. The two new variables in Model 3 were important. If a child complained of bullying, or if parents felt that the child was getting inadequate support because of special needs, their communication with school personnel became more difficult. Adding these two variables in Model 3 increased the explanatory power to 15.9%.

To sum up these findings, the regression analysis revealed different aspects of parent satisfaction with their child’s school. Model 1 draws attention to important background variables: child’s grade level, gender, single-mother household and parent education. The variability explained by the model was small, and though the variables are outside of the school’s control, it can control how the school personnel react toward parents and children belonging to different groups.

Model 2 revealed that the feeling of being able to influence school decisions and future vision gave parents confidence in the school and enhanced their general satisfaction, satisfaction with teaching, and communication with school personnel. On the other hand, the traditional means of parent participation by attending social events did not have the expected positive influence on parents’ opinions. It was not significant in regard to parents’ general satisfaction and their evaluation of the quality of teaching. It was, however, significant in regard to communication: participating in social activities at the school made communication with school personnel easier.

In Model 3, it became clear that the most influential variables for parents’ opinions concerned the child’s well-being and school’s responsiveness if the child needed special support. If children frequently complained about bullying, the consequence was parental dissatisfaction in general, and with communication and teaching. Furthermore, the analysis revealed the urgency to react when parents state that their child needs special support at school, since that variable was very influential for parents’ satisfaction in general, and with teaching and communication.

The analysis draws special attention to how disadvantaged single mothers are when approaching school compared to others in the parent group. The findings showed differences in educational level: 12.8% of single mothers only had compulsory education, whereas only 7% of other parents were in that situation. The likelihood of a child receiving inadequate support in school was double for single mothers compared to other parents: 25.8% reported that their children were not getting the necessary support, while only 12.8% of other parents experienced the same problem. Single mothers’ general satisfaction with school was lower than that of other parents, and they experienced difficulties in communication more frequently than did other parents. These findings clearly indicate that social factors influence the support services children get at school; home–school relations and communication; and parents’ satisfaction with school in general.

Discussion

Parental satisfaction with their children’s school varied, even though it was in most cases very high. More than half of the parent group was totally or very satisfied, and an additional 35% were rather satisfied, as shown in . When results are so positive at first glance, it is easy to overlook that 7% of the parents were dissatisfied and another 7% said that they were neutral, and thereby not willing to say that they were satisfied. Even though an acceptable rate of dissatisfaction is debatable, it is important to be aware of the groups of parents that are more prone to be dissatisfied than others, especially since these parents share some common traits.

Figure 1. Percentage of parents’ answers to a question about their general satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their child´s school (n = 2113).

Responsiveness to children’s needs

The results show that the most important aspects influencing parents’ satisfaction or dissatisfaction with school relate to their children’s well-being and development. When children complain about being bullied, or when parents are disappointed because the school is not responsive to their children’s need for special support, they experience a loss of needed and desired cooperation that manifests in disappointment and dissatisfaction. The importance of cooperation and coherent effort focusing on children’s learning and maturation is accentuated by the findings, which show that parents’ dissatisfaction increases as children get older, and especially between 4th and 5th grade (Jónsdóttir & Björnsdóttir, Citation2012). An explanation for this can be related to a systemic change at that point in many of the compulsory schools in Iceland: students often get new teachers, a few more subjects, and two to three more lessons per week at this time. These changes may be particularly challenging for students in need of special support, which is manifested in findings showing that parents of children in need of special support are more dissatisfied compared to those of other parents. The need for special support also increases as students get older, and the difference in the percentage of students that parents consider to have learning or behavioural difficulties is quite striking. For the youngest students, 19% of the parents claimed that this was the case, as opposed to 28% of the parents of teenagers (Jónsdóttir & Björnsdóttir, Citation2012).

The importance of influence

The feeling of being able to influence the school’s decisions and future vision is important for parents. Those who feel that they are able to influence the school in this way are generally more satisfied with the school, and especially with the teaching, and this feeling also makes communication with school personnel easier. This is in line with findings from other studies that failing to include parents in important decisions in school settings indicates that parents are not treated as equals (Bæck, Citation2009). Moreover, teachers’ opinions of parents are often ambivalent; they see parents either as a support or a barrier to successful teaching (Rasmussen, Citation2004). Thus, school professionals need to discuss and clarify the attitudes and values they bring into the relationship with students’ families.

On the other hand, the findings of this study show that traditional methods of parental involvement (i.e. attending social events) increase neither general parental satisfaction nor satisfaction with teaching specifically, but does have a positive influence on communication between parents and school personnel. Encouragement and support for parents is more important than tutelage and guidelines, according to Jeynes’ (Citation2011b) conclusion on how schools can foster parental involvement, and the findings here certainly point in the same direction. The relationship between parents and school personnel, with supervisory teachers as key figures, can be sensitive and somewhat personal, but must be cultivated with care.

Equity for all but single mothers

International research has shown that parental participation in school-related activities contributes to children’s success at school (Desforges & Abouchaar, Citation2003; Hattie, Citation2009, Citation2012; Jeynes, Citation2005, Citation2011a). Parents experience pressure to participate because it is in their children’s best interest (Böök & Perälä-Littunen, Citation2015). The present study echoes these findings: both parents and school professionals believe that parental support is important to the academic achievement of children (see also Jónsdóttir & Björnsdóttir, Citation2012). However, findings from the present study also indicate that parents are presented with varying opportunities to become involved, to have influence in school and to get special support if they feel that their child needs it. Research shows that parents with more formal education are more likely to participate in home–school cooperation, and more likely to acknowledge the importance of parental support in education (Bæck, Citation2009). Furthermore, researchers have claimed that schools are more likely to match middle-class parents’ values and involvement styles than those of the working class (Bæck, Citation2005; Lareau, Citation2000). Findings from the present study indicate that this may affect the extent to which parents’ voices are heard when arguing for their children’s needs for special support in school. Even though parental assessment of whether their child needs special support in school is not the basis for schools’ decisions to provide such support, parents’ confidence in speaking on behalf of their child, in a way that the schools consider to be reliable and persuasive, may play a role in the decision. Therefore, it is worrying that single mothers are overrepresented in the group of parents who view their children as in need of special support, but not getting any. The educational level among single mothers is lower compared to the other parent groups in this study, and the findings indicate that parental background influences aspects such as receiving special support in school. When parents of children with learning or behavioural difficulties feel that their needs are not met in school, their satisfaction is influenced in a negative way. On the other hand, if parents feel that the special needs of their child are being met, they tend to be more satisfied and find communication easier compared to parents who have children with no disabilities (Jónsdóttir & Björnsdóttir, Citation2012). The same mechanism was demonstrated by Bæck (Citation2007).

The present findings also indicate that it is somewhat harder for schools to please more educated parents. Single mothers feel powerless compared to other parents, but are also more willing than others to participate in social activities at school. Perhaps school personnel tend to listen more carefully when two parents speak on behalf of a child, or when those with more education voice concerns. If this is the reality, intended or not, there is urgent need to open a discussion in Icelandic schools about equity, social status, and the necessity of distributing quality teaching and ‘goods’, such as special support, in a fair way to students. Keeping in mind that the majority of teachers in Icelandic compulsory schools are women, just like the single mothers, these findings also call for critical discussions about respect, women’s status, and power structures within the school system.

It is a common belief that Iceland is a society of educational equity. The present findings concerning different levels of access to special support, the influence of parents’ educational level, and the importance of feeling that the school appreciates parents’ opinions all contest the idea of equity as a major value in the relationship between schools and student families. One of the major issues to address is probably the illusion of equity, since it is not necessarily a leading value in practice. It is necessary to acknowledge that the social status, gender, educational level and cultural values of parents do, indeed, have an impact on the rationale and practice of parental involvement in Icelandic schools, just as in schools in other countries (Bæck, Citation2009, Citation2010; Pepe & Addimando, Citation2014).

Concluding remarks

Parents value their children’s well-being in school as much as their achievements, and even though media discussions often seem to suggest otherwise, parents will sometimes value well-being even more (Desforges & Abouchaar, Citation2003). However, policy documents, such as a white paper released by the Icelandic Ministry of Culture and Education (Mennta- og menningarmálaráðuneytið, Citation2014), show that school authorities do not necessarily seem to be very aware of parents’ priorities, or sufficiently respect parents’ opinions. Communal leaders and school personnel are under pressure from international comparisons such as PISA, and the position is often ambivalent on the local level, as can be seen in policy documents (Reykjavíkurborg, Citation2015).

Emphasis on equity and quality in educational systems has been thoroughly discussed by Sahlberg (Citation2014), who questioned whether this emphasis should be called Nordic, fearing that so-called Nordic values of equality could be changing. The findings from the present study in some respects sustain this fear. In Iceland, the blame cannot be put on free school choice, like in Sweden (Östh et al., Citation2013), but at the same time many other influences of GERM can be traced within the Icelandic compulsory school system, such as stronger measures of control over schools. The situation is difficult: the Nordic point of view on education, which emphasizes quality and equity, is visible in official policy documents, but the actions of politicians in charge of the Ministry of Education in Iceland point in a somewhat different direction. The experiences of parents also show that treating all children and all parents equally does not seem to be of prime concern in school practice. The lack of school funding or access to professional expertise cannot excuse this. The illusion of the Icelandic educational system as upholding the values of equity and quality may be one of the reasons for the downplaying of equity in schools’ practice, which in turn is displayed in parents’ dissatisfaction. It is likely that many teachers and school leaders would reconsider how they act in home–school relationships and reform their decisions and daily practices if the discussion about home–school relations were informed by the findings from the present study and from similar studies in other national contexts. Quality and equity are often promoted as values that are generally emphasized in the Nordic countries (Sahlberg, Citation2014), but findings from the present study signal the importance of bringing these values forth when working with home–school relations and including them in discussions about school development, where school professionals, parents and students should all have a respected voice. The image of equity in Icelandic schools is disputable. If the aim is joint responsibility for student welfare and education, parental involvement must be discussed and encouraged in many different ways.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bæck, U.-D. K. (2005). School as an arena for activating cultural capital: Understanding differences in parental involvement in school. Nordisk Pedagogik, 25(3), 217–228.

- Bæck, U.-D. K. (2007). Foreldreinvolvering i skolen. Delrapport fra forskningsprosjektet “Cultural encounters in school. A study of parental involvement in lower secondary school.” ( Norut AS Rapportserie, SF 06/2007). Tromsø: Norut AS.

- Bæck, U.-D. K. (2009). From a distance – How Norwegian parents experience their encounters with school. International Journal of Educational Research, 48(5), 342–351. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2010.03.004

- Bæck, U.-D. K. (2010). Parental involvement practices in formalized home-school cooperation. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 54(6), 549–563.

- Bæck, U.-D. K. (2013). Lærer-foreldre relasjoner under press [Teacher-parent relations under pressure]. Barn, 31(4), 77–87.

- Björnsdóttir, A., & Jónsdóttir, K. (2014). Viðhorf nemenda, foreldra og starfsmanna skóla. In G. G. Óskarsdóttir (Ed.), Starfshættir í grunnskólum við upphaf 21. aldar (pp. 29–56). Reykjavík: Háskólaútgáfan.

- Böök, M. L., & Perälä-Littunen, S. (2015). Responsibility in home-school relations – Finnish parents’ views. Children & Society, 29, 615–625. doi:10.1111/chso.12099

- Desforges, C., & Abouchaar, A. (2003). The impact of parental involvement, parental support and family education on pupil achievement and adjustment: A literature review (DfES Research Report 43). Nottingham: DfES publications.

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. London: Sage.

- Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. (2009). Basic econometrics (5th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- Halldórsson, A. M., Ólafsson, R. F., & Björnsson, J. K. (2013). Helstu niðurstöður PISA 2012. Læsi nemenda á stærðfræði og náttúrufræði og lesskilningur. Reykjavík: Námsmatsstofnun. Retrieved from https://mms.is/sites/mms.is/files/pisa_2012_island.pdf

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

- Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. London: Routledge.

- Jeynes, W. H. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relation of parental involvement to urban elementary school student academic achievement. Urban Education, 40(3), 237–269. doi:10.1177/0042085905274540

- Jeynes, W. H. (2011a). Parental involvement and academic success. New York: Routledge.

- Jeynes, W. H. (2011b). Parental involvement research: Moving to the next level. School Community Journal, 21(1), 9–18.

- Jónsdóttir, K. (2013). Desirable parental participation in activities in compulsory schools. Barn, 4, 29–44.

- Jónsdóttir, K. (2015). Teenagers opinions on parental involvement in compulsory schools in Iceland. International Journal about Parents in Education, 9(1), 24–36.

- Jónsdóttir, K., & Björnsdóttir, A. (2012). Home-school relationships and cooperation between parents and supervisory teachers. Barn, 4, 109–127.

- Jónsdóttir, K., & Björnsdóttir, A. (2014). Foreldrasamstarf. In G. G. Óskarsdóttir (Ed.), Starfshættir í grunnskólum við upphaf 21. aldar (pp. 197–216). Reykjavík: Háskólaútgáfan.

- Karlsson, Þ. (2003). Spurningakannanir: Uppbygging, orðalag og hættur. In S. Halldórsdóttir & K. Kristjánsson (Eds.), Handbók í aðferðafræði og rannsóknum í heilbrigðisvísindum (pp. 331–356). Akureyri: Háskólinn á Akureyri.

- Lareau, A. (2000). Home advantage: Social class and parental intervention in elementary education (2nd ed.). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Mennta- og menningarmálaráðuneytið. (2014). Hvítbók um umbætur í menntun. Reykjavík: Author.

- Óskarsdóttir, G. G. (2014). Starfshættir í grunnskólum við upphaf 21. aldar. Reykjavík: Háskólaútgáfan.

- Óskarsdóttir, G. G., Björnsdóttir, A., Sigurðardóttir, A. K., Hansen, B., Sigurgeirsson, I., Jónsdóttir, K., … Jakobsdóttir, S. (2014). Framkvæmd rannsóknar. In G. G. Óskarsdóttir (Ed.), Starfshættir í grunnskólum við upphaf 21. aldar (pp. 17–27). Reykjavík: Háskólaútgáfan.

- Östh, J., Andersson, E., & Malmberg, B. (2013). School choice and increasing performance difference: A counterfactual approach. Urban Studies, 50(2), 407–425. doi:10.1177/0042098012452322

- Pepe, A., & Addimando, L. (2014). Teacher-parent relationships: Influence of gender and education on organizational parents’ counterproductive behaviors. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 29(3), 503–519. doi:10.1007/s10212-014-0210-0

- Poikolainen, J., & Silmäri-Salo, S. (2015). Contrasting choice policies and parental choices in Finnish case cities. In P. Seppänen, A. Carrasco, M. Kalalahti, R. Rinne, & H. Simola (Eds.), Contrasting dynamics in education politics of extremes: School choice in Chile and Finland (pp. 225–243). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Rasmussen, J. (2004). Undervisning i det refleksivt moderne: Politik, profession, pædagogik. København: Hans Reitzel.

- Reykjavíkurborg. (2015). Starfsáætlun 2015 (Reykjavik City – Education and Youth – Policy and Projects 2015). Retrieved from http://issuu.com/skola_og_fristundasvid/docs/starfsaetlun_sfs_2015/c/suil0dn

- Sahlberg, P. (2011). The fourth way of Finland. Journal of Educational Change, 12(2), 173–185. doi:10.1007/s10833-011-9157-y

- Sahlberg, P. (2014). True facts and tales about teachers and teaching: A nordic point of view. Paper presented at the future teachers: A profession at crossroads: 14th of August 2014, Reykjavík, Iceland. Retrieved from http://starfsthrounkennara.is/future-teachers-a-profession-at-crossroads/

- Sahlberg, P. (2015). Finnish lessons 2.0: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland? (2nd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press.

- Skolverket. (2009). Sverige tappar i både kunskaper och likvärdighet. Retrieved from http://www.skolverket.se/publikationer?id=2473

- Skolverket. (2012). Likvärdig utbildning i svensk grundskola? En kvantitativ analys av likvärdighet över tid ( Rapport 374). Stockholm. Retrieved from http://www.skolverket.se/publikationer?id=2816

- Þórsdóttir, F., & Jónsson, F. H. (2007). Gildun á mælistikum. In G. Þ. Jóhannesson (Ed.), Rannsóknir í félagsvísindum VIII (pp. 527–536). Reykjavík: Félagsvísindastofnun Háskóla Íslands.