ABSTRACT

This introduction examines the meaning of foreignness, drawing on Jacques Derrida‘s discussion of ‘the aporia’ to propose that foreignness is critically aporetic - undecidable and unstable. At a moment when racist political rhetoric is being normalized and xenophobic political movements are on the rise, thinking about ‘aporias of foreignness’ allows us to reflect upon questions of belonging and hospitality, and the complexity and historical contingency of the relationship between self and other, indigenous citizen and immigrant, asylum-seeker or refugee. The introductory chapter proposes that cinema is a crucial medium through which to rethink foreignness since cinema always involves a potentially disorienting encounter with the unfamiliar, an encounter that is at the centre of the work of artist Ai Weiwei in film and other media.

About foreignness and aporias

It’s a lot of work, being foreign.--Anne Tyler, Digging to America, Citation2006

What does it mean to be-placed-into-foreignness? To be marked as foreign? To inhabit this category and feel its weight? Why might it mean ‘a lot of work’ as a quote from Anne Tyler’s novel specifies? We know that certain bodies, or regions are labeled as foreign but also certain texts and images as well. The foreign is a sticky term—it sticks to a body of a human, or to a particular image—and it marks it as something else, something as not me, something other, alien, some form of alterity.

The word ‘aporia’ expresses doubt, an impasse. Its ancient Greek origin, aporos, means ‘impassable,’ ‘without passage.’ In philosophy, aporia expresses a difficulty in establishing a stable truth since aporia signifies the presence of evidence both for something and, simultaneously, against that something. Being aporetic, thus, points to non-binarism, toward a wavering border.

What do aporias have to do with the figure of the foreigner, a figure that has been historically a preoccupation of philosophy, political theory, cultural studies, and film and media studies to name just a few areas of inquiry? Why might we need aporias to talk about foreignness in more complex and nuanced ways? Jacques Derrida acknowledged his fascination with aporias: ‘the old, worn-out Greek term aporia, this tired word of philosophy and logic, has imposed itself upon me’ (Derrida Citation1993; 12). Aporias obscure clarity and certainty; they frustrate. Rather than overcoming or resolving aporias, Derrida posits their critical potential: ‘I was then trying to move not against or out of the impasse but, in another way, according to another thinking of the aporia, one perhaps more enduring. It is the obscure way of this “according to the aporia” that I will try to determine today’ (Derrida Citation1993, 13). We believe that foreignness invites us to think according to this other logic, indeed, ‘according to the aporia.’

We approached this special issue with an understanding that foreignness is critically aporetic—undecidable, impassable, and thus always quivering. In my (KM) earlier work I theorized the notion of ‘quivering ontologies’ (Marciniak Citation2006, 27) as a way of inhabiting the aporia, of conceptualizing the way the figure of the foreigner is always suspended between her place of origin and the host nation. She is negotiating her subjectivity in the interstices of belonging and, as such, is often vulnerable to processes of inclusion and exclusion, appropriation or expulsion. Quivering ontologies is a concept that allows us to explore the intricacy—and intimacy—of cultural mechanisms that place the foreigner on a precariously wavering border between being and not being a valid, culturally sanctioned subject. We could thus say that the aporetic foreigner embodies the border. Revisiting Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition, Judith Butler writes that Arendt ‘established politics as a public sphere on the basis of the classical Greek city-state and understood that in the private domain, a dark domain by the way, necessarily dark, slaves and children and the disenfranchised foreigners took care of the reproduction of material life’ (Butler, Spivak Citation2007, 14–15). In many cases globally, the disenfranchised foreigners still take care of the reproduction of material life and are ‘the barely legible or illegible human[s]’ (Butler, Spivak Citation2007, 15).

So why foreignness now? ‘Foreign’ derives from the Latin forās, meaning ‘outside.’ In our current historical moment, foreignness is increasingly an operative word that functions as a warning, a worry, a threat, or, indeed, an impasse. And foreignness is a term of unequal value, by all means not a universal term. If one follows President Trump’s rhetoric, for example, one could realize that one is a ‘wrong’ foreigner in the U.S. who came from a ‘shithole’ country, or one could be from a ‘desirable’ region, such as Scandinavia. So, to be sure, not all foreignness is disavowed and repudiated, just the kind that is specifically racially, ethnically, and nationally marked.

In coining the term ‘aporias of foreignness,’ in our special issue we aim to explore the idea that foreignness is always overdetermined and unstable vis-à-vis national belonging and, as such, subject to scrutiny and discipline. Trinh T. Minh-ha, for example, refers to the figure of the foreigner as a ‘traveling self’ and, commenting on the U.S. border politics, she critiques the perception that ‘every immigrant or a voyager of color is a potential terrorist’ (Citation2011, 5). In a current climate, specifically in a European context, we see a vigorous renewal of this idea vis-à-vis the Syrian refugee crisis as waves of Islamophobia rise, singling out specifically the figure of a dark-skinned man as a site of national panic and spearheading what Imogen Tyler calls ‘epidemics of racial stigma,’ recasting ‘refugee crisis’ as a ‘racial crisis’ (Citation2017, 4).

The current frightening rise of xenophobic and nationalistic movements in various parts of the world certainly compels a reflection on foreignness as a perceived contentious and challenging idea. We think of present political tensions regarding the Syrian refugee crisis, the morbid reality of new border regimes and border deaths around Europe and the US, and the UK’s vote for ‘Brexit’—largely motivated by anti-immigrant sentiments and a desire to return to a core of white ‘Englishness.’ We think of the inflammatory rhetoric around the construction of a barrier between Mexico and the US, President Trump tweeting on 5 May 2018, ‘Our Southern border is under siege. Congress must act now to change our weak and ineffective immigration laws. Must build a wall.’ This is, however, the most visible local example of a global shift towards separation. As Ai Weiwei observes, ‘When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, 11 countries around the world were cut off by border fences and walls. By 2016, some 70 countries had built border fences and walls. The U.S. is now trying to build a new wall with Mexico and for me this is unthinkable. The solution has never worked and it testifies to the notion that we have become less courageous’ (Ai Citation2018, 2).

Transnational cinematic cultures are inevitably engaged with multifarious representations of foreignness that ask spectators to think intersectionally vis-à-vis complex configurations of nativity, race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, or economic privilege. The post-2000 period in particular offers a rich archive of global films—features, documentaries, experimental productions and online video—that place (im)migrants, refugees, exiles at the heart of the diegesis. In putting ‘aporias of foreignness’ center stage, we are interested in a politics and aesthetics of encounter, a trope we understand broadly, one that focuses on encounters occurring diegetically (for example, citizen/foreigner, foreigner/foreigner), or meta-diegetically (for example, the spectator and the text).

We treat ‘foreignness’ as a relational concept, considering not only the figures of (im)migrants and refugees but also historically dispossessed indigenous populations. We draw an inspiration here from Derrida’s complex contention that while the aporetic foreign has traditionally been considered a figure of death, there is at the same time an obligation to host the foreigner. We hope that this special issue will contribute to transnational cinema studies by bringing to light a rich archive of works that often show how xenophobia and xenophilia together function in the imagining of the nation. Simultaneously, we are interested in the way formal aspects of cinema, while foregrounding foreignness, at times play with a defamiliarization of spectatorial comfort by emphasizing alterity articulated both by the cinematic apparatus and the social context. For example, film and media scholars commenting on migrant, intercultural, or transnational cinema and grappling with the foreignness of certain aesthetic forms have approached filmic medium through discussions of ‘aesthetics of opacity’ (Bayraktar Citation2016, 145), ‘haptic visuality’ (Marks Citation2000), ‘revolting suture’ (Marciniak Citation2017a, 385), or ‘elsewhere-within-here’ (Trinh Citation2011). Transnational encounters involve figurations of (mis)recognition, conflict, desire, appropriation, and transgression. Focusing on the ways that cinematic language might offer ‘alternative alterities,’ we have sought innovative theoretical foci that would let us imagine ‘foreign’ difference outside the paradigms of subjugation, victimhood, or exoticization.

Foreignness and cinema

Every film is a foreign film.--Atom Egoyan and Ian Balfour, Introduction to Subtitles: On the Foreignness of Film, Citation2004

Film is well suited to an investigation of foreignness in so far as an encounter with a film always involves an encounter with the unfamiliar, with images and sounds that require translation and recontextualization. Discussing a hypothetical spectator’s bewilderment in the face of a new artwork, text or performance, Slavoj Žižek likens the experience to an alienating encounter with an unfamiliar religious ceremony which draws our attention to cultural difference and the limits of our knowledge: ‘When we are witnessing an intense religious ritual, it is commonplace to claim that we, outside observers, cannot ever properly interpret it, since only those who are directly immersed in the life-world—part of which is this ritual—can comprehend its meaning (Žižek Citation2004, 286). In a similar way, he suggests, we watch films with a ‘foreign gaze,’ especially when we view a film for the first time. The relationship between spectator and screen is characterized by uncertainty, speculation and, perhaps confusion and so the viewing of a film involves the staging of foreignness. This is the experience of sense-making, of interpretation and translation, and the search for recognizable patterns and structures. While the impression of an encounter with foreign bodies and cultures might be heightened with transnational media, to some degree it characterizes our viewing of all films.

Becoming-refugee/becoming-foreign

No one likes refugees.--Charles Simic, ‘Refugees,’ Citation1999

A refugee could be anybody. It could be you or me. The so-called refugee crisis is a human crisis.--Ai Weiwei, Humanity, Citation2018

A US-based poet, Charles Simic, recalling his experiences of dislocation from post-WWII Yugoslavia, writes sarcastically: ‘My family, like so many others, got to see the world for free thanks to Hitler’s wars and Stalin’s takeover of Eastern Europe’ (Citation1999,120). And he adds: ‘It’s hard for people who have never experienced it to truly grasp what it means to lack proper documents….The pleasure of humiliating the powerless must not be underestimated’ (Simic Citation1999, 121). Ai Weiwei’s recent epic, Human Flow (Citation2017), a film currently gaining an international momentum, is keenly aware of these sentiments. We want to focus on Human Flow for a moment because of the extraordinary scope of the material it presents and the attention the film is receiving due to Ai’s international stature as an exilic (‘foreign’) artist and activist committed to social justice. The film offers a panoramic overview of the global refugee crisis, covering 23 countries from the US/Mexico border to Libya, Lebanon, Kenya, Pakistan, Turkey, Gaza, and across Europe. It offers interviews with several refugees, NGO workers, politicians and activists, which are scattered throughout the film like poems appearing on screen, punctuating the flow of images. At the heart of this documentary that offers harrowing images of human dispossession and trauma mixed with shots of human movement, landscapes, objects, and animals is an ethical consideration of how to represent a humanitarian disaster of such proportions in a way that resists aestheticization or sublimation of trauma.

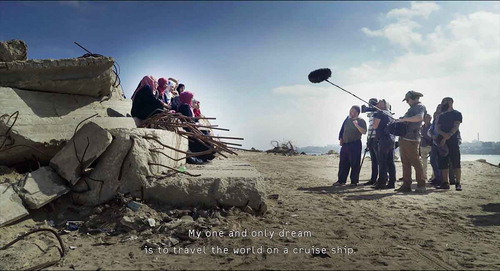

Eliminating voice-over, Human Flow is a contemplative cine-essay, advocating a politics of witnessing, and presenting Ai and his film crew as they travel around the world documenting but also being-with refugees (see ). In many ways, Human Flow is thus about encounters. This mode of ‘being-with’ is exemplified by Ai himself, as he appears on screen at various moments without addressing the viewers—directing the crew, cooking meat on the open grill, filming with his cell phone, buying fruit, getting a haircut, cutting a man’s hair, visiting graves (see , ). His presence then introduces varied emotionalities as he is directly interacting with refugees, joking with them, consoling them, offering water or blankets. At one point, we see him walking alongside refugees and, of course, as audience, we understand that Ai’s walking has a different valence and a different weight than the refugees’ walking. This ‘walking alongside’ might serve as a metaphor for an understanding how to apprehend the crisis and represent refugees who, at some point, were just inhabitants of specific societies and cultures and have become refugees and thus have become foreign through various modes of escaping from war zones, political strives, upheavals, or postcolonial hardships. The film makes it clear that no one just is a refugee, or a foreigner—one becomes one. Following Simone de Beauvoir who taught us that femininity is a social construct—‘One is not born, but rather becomes, woman’ (Citation1974, 301) —it is clear that being a refugee is a social construct as well. The film thus shows us the process of moving into a refugee status and then experiencing—living—its consequences. It reveals various painful ways of inhabiting this category of, to use Butler’s words, ‘spectral humans, deprived of ontological weight and failing the tests of social intelligibility’ (Citation2007, 15).

Figure 2. Walking alongside refugees: Ai (left) uses a cameraphone to film migrants boarding a ferry.

The tactic of ‘walking alongside’ refugees might be thought of as akin to Trinh’s ‘speaking nearby’ (Chen Citation1992), a methodology Trinh employed, for example, in her documentary film Reassemblage: one that strays from ‘speaking for’ or ‘speaking about’ Senegalese rural women she filmed. ‘Speaking nearby’ is thus a conceptual attempt to avoid a patronizing, racist, and controlling lens that apprehends the filmed subject. Indeed, Trinh defines the mode of ‘speaking nearby’ as ‘a speaking that does not objectify, does not point to an object as if it is distant from the speaking subject or absent from the speaking place. A speaking that reflects on itself and can come very close to a subject without, however, seizing or claiming it’ (Chen Citation1992, 87). Ai’s deliberate presence in Human Flow certainly points to the way the film reflects on itself and his ‘walking alongside’ refugees at least gestures toward some form of filmic transparency, toward a desire to find a non-patronizing, non-sentimental, non-sensational way to reflect on what it might mean to become a refugee. It gestures toward respect (and at one point we hear Ai insisting to a man, ‘I respect you’).

There is one moment, however, that makes it quite clear that ‘being-with’ refugees or ‘walking alongside’ them is, after all, only provisional, temporary. We see Ai holding a piece of paper with words ‘#standwithrefugees’ and then the wind blows it away, underscoring the fleeting nature of such efforts. As viewers we have already been prepared for this metaphorical moment as, earlier, Ai somewhat playfully exchanges passports with Mahmoud, a Syrian refugee (See ). The exchange lasts a brief instance as Mahmoud says, ‘You can also take my tent,’ and Ai acknowledges that he has an art studio in Berlin. This failed ‘exchange’ creates a tonality of incongruity and obvious awkwardness, ultimately pointing to the limits of such an ‘exchange.’ ‘Standwithrefugees’ is thus an evocative if not an aporetic hashtag of a limited material applicability while it still acknowledges the possibility of emotional solidarity or affinity. In doing this, it reminds us of the fraught issue of allyship and tensions surrounding this concept; that is, despite socially conscious intentions, allyship often perpetuates an uneven distribution of power that further disenfranchises the marginalized and dispossessed. And Ai seems to be acutely aware of this. Of his interaction with Mahmoud, he says in an interview with The Guardian: ‘You tell these people that you’re the same as them. But you are lying because you are not the same. Your situation is different; you must leave them. And that’s going to haunt me for the rest of my life’ (Brooks Citation2017).

Figure 4. Ai and Mahmoud playfully exchange passports in front of the camera and a group of onlookers.

Human Flow thus contemplates the possibilities and limits of being-with refugees while visually intertwining drone photography with close-ups on the ground (see ). The tactic of employing spectacular aerial shots and then taking us to close-ups (with varied affective impact, as we see crying and smiling children, barbed wire, a photo of someone’s cat on a cell-phone, a wrecked stove in a burned down house, refugee tents soaked in rain, open graves) suggests that the refugee crisis is both global and intimate, distant and not-so-distant. This constant, aporetic mode-switching—zooming in and zooming out—corresponds to a deliberate accumulation of the diversity of clashing images: still landscapes enveloped in a fog, shots of sea, images of mountains and roads, all juxtaposed with what Jacques Rancière called the ‘intolerable image’ – evoking the abject and perilous circumstances of refugees (Citation2009, 83).

Like his other, often controversial work,Footnote 1 Human Flow has received criticism; Brooks interviewing Ai for The Guardian article summarizes these critiques: ‘His critics view him rather differently: as a crude provocateur, trading in stereotypes and bankrolled by the west’ (Citation2017). And Ai’s response to such critiques is quite pointed: ‘All day long, the media ask me if I have shown the film to the refugees: ‘When are the refugees going to see the film?’ But that’s the wrong question. The purpose is to show it to people of influence; people who are in a position to help and who have a responsibility to help. The refugees who need help—they don’t need to see the film. They need dry shoes. They need soup’ (Brooks Citation2017). If we accept his contention, it perhaps becomes clear why the film feels excessively long—140 min: it requires enduring spectatorship, one that accepts a certain level of monotony and the feeling of never-endedness, of unpredictable rhythms of movement and stasis, which appear to emulate the condition of refugeeism.

The pieces collected in this special issue examine the notion of aporetic foreignness in relation to contemporary film and media from a variety of perspectives, concentrating upon more marginal, less celebrated work than that of Ai, who is one of the most famous contemporary artist-film-makers, as was demonstrated by the high-profile UK premiere of Human Flow on 4 December 2017 when it was screened in over 200 cinemas and followed by a live-streamed panel discussion from London featuring the director.

Bruce Bennett’s article, ‘Becoming Refugees: Exodus and Contemporary Mediations of the Refugee Crisis,’ discusses a TV documentary series that follows the journeys of a number of migrants attempting make their way to Europe by various means, negotiating geographical and political borders and the vertiginous experience of foreignness. Situating the series in relation to a tradition of ethnographic films and also of accented cinema, the article discusses the ways in which Exodus (Bluemel, Citation2016) confronts the problem of giving a voice to the migrants. The article pays particular attention to the way that the mobile phone footage shot by the refugees is incorporated throughout the series, this participatory film-making process resulting in an innovative ethical and aesthetic solution that aims to place the spectator alongside these travellers.

Shohini Chaudhuri’s essay, ‘The Alterity of the Image: The Distant Spectator and Films about the Syrian War,’ discusses three experimental documentaries, circulating principally through international film festivals, that offer unfamiliar perspectives on the conflict and, like Exodus, undertake a self-reflexive examination of the mediation of this conflict. Silvered Water: Syria Self-Portrait (Mohammed, Bedirxan, Citation2014) is compiled from online videos, The War Show (Zytoon, Dalsgaard, Citation2016) is a personal account of the Syrian revolution from the perspective of Syrian DJ, Obaidah Zytoon and her companions, assembled from the footage they shot, while Little Gandhi (Kadi Citation2016), is a portrait of a peace campaigner killed by Syrian security forces in 2011. Chaudhuri argues that the ‘alterity’ or ‘foreignness’ of the image in the fragmented aesthetic of these films emphasizes the viewer’s distance from the figures and events portrayed in the films, and the limits of what can be conveyed by the documentary image. The ‘foreign’ or aporetic film image is the basis here for a radically productive incompleteness, which is the basis for the spectator’s imaginative and intellectual engagement with these partial histories of the Syrian war.

Bhaskar Sarkar’s essay, ‘On No Man’s (Is)land: Futurities at the Border,’ considers questions of foreignness in relation to the drawing and redrawing of national and regional boundaries. Concentrating on the documentary, …Moddhikhane Char [No Man’s Island] (Savangi Citation2013), Sarkar discusses the ways in which the shifting border between India and Pakistan draws attention to the violence and the abrupt mobility of boundaries, which can render familiar landscapes and individuals foreign. No Man’s Island is concerned with the shifting borderzone where the Ganges slices through Bengal, continually reshaping the topography, creating new islands, destroying river-banks, and raising questions about the permanence of borders, the capacity of media forms to articulate and document these abstract, invisible boundaries, and the speed with which people can find themselves on the wrong side, or caught somewhere in between.

In ‘“Seeing Justice to be Done”: The Documentaries of ICTY and the Visual Politics of European Value(s),’ Neda Atanasoski discusses a specialized category of documentary, a series of educational films produced by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. These documentaries, which sit within an expanded transnational screen culture, document the history of the Tribunal, key trials staged at ICTY, and certain passages of the civil wars of the former Yugoslavia. Atanasoski argues that these documentaries, which are designed as cautionary texts, constitute a discourse on Western European values which asserts that terrorizing violence and ethno-nationalism are ‘foreign’ to Western European liberalism, and are associated in these films with post-socialist and Southern Europe. Thus, for Atanasoski, the ICTY films invite us to reflect upon the role of documentary in gathering and preserving evidence, delimiting boundaries, and tracing the historical and geographical dimensions of foreignness.

Aga Skrodzka’s article, ‘Xenophilic Spectacle in Films about Sex Slavery,’ addresses an extensive group of feature films that deal with sex slavery and trafficking. Skrodzka argues that the exploitable foreign body of the sex slave that is a sometimes marginal presence within these films, is the object of ambivalent attitude towards the foreign. The abject sex slave is the object of pity, compassion and contempt (for both spectators and protagonists), and also xenophilic desire. Skrodzka argues that recent sex-slave films belong to a long history of cinema’s preoccupation with the topic, stretching back to the ‘white-slavery’ films—or ‘slavers’—of early Hollywood, in which the topic was a coded expression of panic at women’s increasing mobility and social agency. Thus, in Skrodzka’s argument, the cinematic sex slave is an aporetic figure on which social anxieties about women’s autonomy and female desire are projected, while sex-slave narratives provide the pretext for an investigation into the taboo world of solicited sex. The figure of the trafficked sex slave embodies the ambivalent usability of the foreign body that is at once exploitable and commodified, but also abject, dehumanized and ‘illegal’.

In the concluding article in this special issue, ‘“As Foreign as it Gets”: Indigenous Immigrants, Transnationality, and Rage in Sherman Alexie’s The Business of Fancydancing,’ Katarzyna Marciniak examines the concept of foreignness in relation to indigenous identity through a study of the formally playful debut film by Native-American film-maker, novelist and poet, Alexie, The Business of Fancydancing (Citation2002). The film tells the story of a gay poet who returns from Seattle to visit the reservation on which he grew up, but on returning home finds he no longer belongs, and is regarded by his former friends as an exploitative sell-out who has built a successful career from exoticizing stories of abject life on the reservation. Using the critical frame of the ‘transnational’ to think about the multiply transected complexity of the ‘national’ and deploying the concept of ‘lyrical rage’ to describe the ways in which the experience of precariousness and dislocation is articulated both by the film and the characters within it, Marciniak’s discussion of The Business of Fancydancing explores the foreignness of indigenous identity, and the legacy of colonization and enclosure.

Considered together, these articles offer a critical account of the ways in which formally varied examples of recent transnational screen media have conceived foreignness during a historical interval in which national and regional borders are becoming increasingly impassable, as formerly invisible, conceptual boundaries take violent material form as concrete walls and fences topped with razor wire. They invite us to look anew at these proliferating structures, and to consider Ai Weiwei’s claim that, ‘Allowing borders to determine your thinking is incompatible with the modern era’ (Ai Citation2018, 37).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Katarzyna Marciniak

Katarzyna Marciniak is Professor of Transnational Studies in the English Department at Ohio University. She is the author of Alienhood: Citizenship, Exile, and the Logic of Difference (University of Minnesota Press, 2006) and Streets of Crocodiles: Photography, Media, and Postsocialist Landscapes in Poland (Intellect/University of Chicago Press, 2010), co-editor of Transnational Feminism in Film and Media (Palgrave, 2007), Protesting Citizenship: Migrant Activisms (Routledge, 2014), Immigrant Protest: Politics, Aesthetics, and Everyday Dissent (SUNY Press, 2014), and Teaching Transnational Cinema: Politics and Pedagogy (Routledge, 2016). With Anikó Imre and Áine O‘Healy, she is Series Editor of Global Cinema, a new book series from Palgrave.

Bruce Bennett

Bruce Bennett is Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at Lancaster University. His publications include the monograph, The Cinema of Michael Winterbottom: Borders, Intimacy, Terror (2014), and the co-edited volumes, Teaching Transnational Cinema: Politics and Pedagogy (2016), and Cinema and Technology: Cultures, Theories, Practices (2008). He has published work on the films of James Cameron and Michael Bay, film and new media technology, documentary cinema, and the war on terror on film and television. Forthcoming publications include the monograph, Revolutionary Films: Cycling and Cinema (Goldsmiths/MIT, 2018).

Notes

1. See Marciniak (Citation2017b) for a discussion surrounding Ai's photographic performance in relation to Aylan Kurdi, a Syrian toddler who drowned off the coast of Turkey in 2015.

References

- Ai, W., dir . 2017. Human Flow . Germany/USA/China/Palestine: 24 Media Production Company/AC Films/Ai Weiwei Studio/Ginger Ink and Halliday Finch/Green Channel/HighLight Films/Human Flow/Maysara Films/Optical Group Film and TV Productions/Participant Media/Redrum Production/Ret Film.

- Ai, W. 2018. Humanity , Edited by L. Warsh . Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Alexie, S., dir. 2002. The Business of Fancydancing . USA: FallsApart Productions.

- Bayraktar, N. 2016. Mobility and Migration in Film and Moving-Image Art . New York: Routledge.

- Brooks, X. 2017. “Ai Weiwei: ‘Without the Prison, the Beatings, What Would I Be?’” The Guardian . September 17. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2017/sep/17/ai-weiwei-without-the-prison-the-beatings-what-would-i-be.

- Chen, N. N. 1992. “’Speaking Nearby’: A Conversation with Trinh T. Minh-Ha.” Visual Anthropology Review 8 (1): 82–91. doi:10.1525/var.1992.8.1.82. Spring.

- De Beauvoir, S. 1974. The Second Sex . Translated by H. M. Parshley. New York: Vintage Books.

- Derrida, J. 1993. Aporias . Translated by Thomas Dutoit. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Egoyan, A. , and I. Balfour . 2004. “Introduction.” In Subtitles: On the Foreignness of Film , edited by A. Egoyan and I. Balfour , 21–31. Cambridge, Mass and London: MIT Press.

- James, B., dir. 2016. Exodus: Our Journey to Europe . UK: KEO films.

- Butler, J. , and G. Chakravorty Spivak . 2007. Who Sings the Nation State? Language, Politics, Belonging . London, New York, Calcutta: Seagull Books.

- Kadi, S., dir. 2016. Little Gandhi . USA/Syria/Turkey: Samer K Production.

- Marciniak, K. 2006. Alienhood: Citizenship, Exile, and the Logic of Difference . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Marciniak, K. 2017a. “Revolting Aesthetics: Feminist Transnational Cinema in the US.” In Routledge Companion to Cinema and Gender , edited by K. Hole , E. Dijana Jelača , A. Kaplan , and P. Petro , 385–394. New York: Routledge.

- Marciniak, K. 2017b. ‘“Opening A Certain Poetic Space” What Can Art Do for Refugees?’ Media Fields Journal 12: Media and Migration. http://mediafieldsjournal.org/opening-a-certain-poetic-space/

- Marks, L. U. 2000. The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses . Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Mohammed, O. , and W. Bedirxan dir. 2014. Silvered Water: Syria Self-Portrait . France/Syria/USA/Lebanon: Les Films d’Ici, Proaction Film.

- Rancière, J. 2009. The Emancipated Spectator . Translated by G. Elliott. London: Verso.

- Savangi, S., dir . 2013. …Moddhikhane Char [No Man’s Island] . India: Sourav Sarangi, Stefano Tealdi, Signe Byrge Sørensen, Jon Jerstad.

- Simic, C. 1999. “Refugees.” In Letters of Transit: Reflections on Exile, Identity, Language, and Loss , edited by A. Aciman , 115–135. New York: New Press.

- Trinh, M.-H. T., dir . 1983. Reassemblage: From Firelight to the Screen . USA: Jean-Paul Bourdier.

- Trinh, M.-H. T. 2011. Elsewhere, within Here: Immigration, Refugeeism, and the Boundary Event . New York: Routledge.

- Tyler, A. 2006. Digging to America . New York: Ballantine Books.

- Tyler, I. 2017. “The Hieroglyphics of the Border: Racial Stigma in Neoliberal Europe.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 1–19. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1361542.

- Žižek, S. 2004. “The Foreign Gaze Which Sees Too Much.” In Subtitles: On the Foreignness of Film , Edited by A. Egoyan and I. Balfour , 285–306. Cambridge, Mass and London: MIT Press.

- Zytoon, O. , and A. Dalsgaard dir . 2016. The War Show . Denmark/ Germany, Finland: Fridrhjof Film, Oktober, Yleisradio.