ABSTRACT

The phenomenon of rural depopulation is seen in many places around the world as young adults move to urban areas where there is greater access to employment, government services and social activities. In Cyprus rural villages exemplify this pattern of demographic decline. Depopulation creates a cycle of loss that influences community identity and feelings of belonging. In this paper I argue that heritage may play a role in building community resilience in socially and economically marginalised rural areas. I focus on the heritage work of a Cypriot regional primary school – how its teachers and pupils created a new common sense of identity for the school, its pupils and the rural villages that the school serves. This case illustrates how even small heritage initiatives may enliven, strengthen and create new social networks – resources necessary to maintain a sense of place, build and sustain community resilience in rural areas.

As an anthropologist my interest lies in the relationship between socio-economic change, identity and feelings of belonging in rural Cyprus. In this paper I suggest that heritage – the process of building relationships with the past in the present – may play a role in building community resilience in socially and economically marginalized rural areas. Here I use the term resilience in the manner of Magis (Citation2010, 402), who defines community resilience as ‘the existence, development, and engagement of community resources by community members to thrive in an environment characterized by change, uncertainty, unpredictability and surprise’. Resilient communities not only have the ability to respond to change, but also have the skills necessary to shape that change and create new plans for the future of the community.

The ‘decline’ of rural areas is increasingly addressed through a place-based integrated approach to development that focusses on identifying what makes rural areas unique (see Li, Westlund, and Liu Citation2019; Markey, Halseth, and Manson Citation2008; Magis Citation2010; Salvia and Quaranta Citation2017). Importantly, it not only accepts that social and economic factors are linked, but also identifies the importance of social networks and community ties to rural renewal. As Li, Westlund, and Liu (Citation2019, 138) state, rural depopulation effects bonding and bridging capital – the close relationships among people within a group that creates cohesion and the looser connections that exist amongst more diverse individuals that may bridge or connect communities (see also European Commission Citation2017, 17–18; Magis Citation2010). These networks hold villages together and make them better able to mobilize resources to adapt to, and initiate change – ultimately increasing the chances that rural villages not only survive but thrive (Li, Westlund, and Liu Citation2019, 138).

Depopulation threatens people’s sense of place as villages become less cohesive, more individualistic and socially and economically isolated (Li, Westlund, and Liu Citation2019, 138). It is here that community-based heritage projects may play their greatest role in resisting this transformation. As Smith (Citation2006, 75) reminds us, ‘[h]eritage is about a sense of place. Not simply in constructing a sense of abstract identity, but also in helping us position ourselves as a nation, community or individual and our ‘place’ in our cultural, social and physical world’. Heritage is also a process of relationship building – creating connections with the past, its people, places and ‘things’ – in the present (Byrne, Brayshaw and Ireland Citation2001, 67–68; Gibson Citation2019; Smith Citation2006). The pasts that are mobilized and the nature of the relationships created with them are based on contemporary needs (Harrison Citation2015, 27; Smith Citation2016; Smith and Campbell Citation2017, 623). Shrinking populations and economies challenge the ability of communities to create and maintain relationships of heritage.

As the case study to follow illustrates, relationships are created, reworked and solidified through the ‘work’ of heritage (Byrne Citation2008). Heritage and identity entangle to create a sense of place and feelings of belonging. This paper focusses on the heritage work of a Cypriot regional primary school – how its teachers and pupils created a new common sense of identity not only for the school and its pupils, but for all the villages that the school serves. This case illustrates how even small heritage initiatives may enliven, strengthen and create new social networks – resources necessary to maintain a sense of place, build and sustain community resilience in rural areas.

I start by establishing the context to this research – the background and process through which the ‘Asinou Village Heritage Project’ developed. I then discuss the project itself, its focus on the abandoned village of Asinou, the heritage ‘work’ of the teachers and pupils at the Asinou Regional Primary School (fieldtrip, student-led research, presentations), and how it forged a new collective identity. Finally, I reflect on the project and touch briefly on the potential for small collaborative heritage projects to contribute towards building strength and resilience in rural communities both in Cyprus and abroad.

The emergence of the Asinou Village Heritage Project

In Cyprus, schools (like local banks, post offices and coffeeshops) play important social and economic roles in village life as places to meet, exchange knowledge, news and business. The Ministry of Education is forced to close schools when student enrolment drops below approximately 15 pupils (Georgia Mylourdou, personal communication, November 2019). Their closure impacts the social and cultural wellbeing of these communities. In many rural areas today, children affected by these closures attend new regional schools located both geographically and socially separate from their village communities.

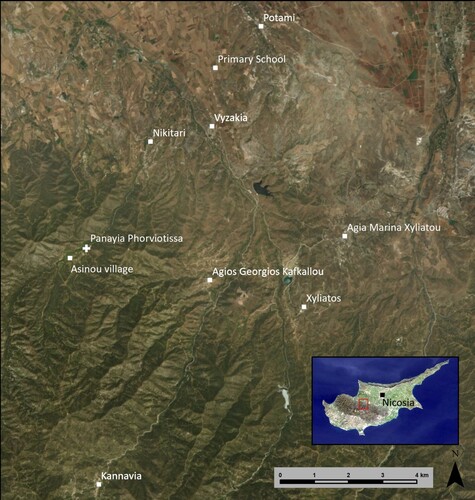

The Asinou Regional Primary School opened in 2009. In previous years, the schools in the villages of Kannavia, Agia Marina, Agios Georgios Kafkalou and Xyliatos had closed, and their children attended school in the larger villages of Nikitari, Potami or Vyzakia (each with populations less than 630 people), which remained in use up until the opening of the Asinou Regional Primary School (). As teacher Georgia Mylourdou states, parents’ associations and community councils in these villages pushed to have a regional school built that would serve all the region’s children and enable teachers to teach one class rather than several as was necessary in the village schools (Georgia Mylourdou, personal communication, November 2019).

In creating the new regional school, care was taken to make sure that it was as neutral as possible – not connected to any one village more than another as it needed to serve each equally (Kyriakos Alexandrou, personal communication, August 2017). With this in mind, the Asinou Regional Primary School was built on land at the intersection of community boundaries and named for the shared ‘official’ heritage of the area – the famous twelfth-century UNESCO-listed Asinou Church (Panagia Phorviotissa) located approximately 8 km to the southwest of the school in the foothills of the Adelphi State Forest. As I will discuss, this care taken to create a school that was regional resulted in an institution that was geographically and socially separate from the villages (and the children) that it served.

The Asinou Village Heritage Project was part of a larger community-based research project called Pathways to Heritage (PATH 2016–2018) that I developed in partnership with the Nikitari Community Council.Footnote1 PATH was initiated to explore the council’s concern that younger people were leaving the rural village which in turn was affecting feelings of community identity and belonging. Answering the question – ‘what is important to you about this place where you live?’ – was the starting point for addressing this concern (Gibson Citation2019).

To understand the importance of the area to its children, I brought this question to the Asinou Regional Primary School where I worked with its teachers to design activities that were accessible to children from the ages of 7 through 11 (see Kindon, Pain and Kesby Citation2007 for participatory research techniques). The My Village exercises used visual techniques such as participatory mapping and drawing. Literat (Citation2013, 84) has shown that participatory drawing is an effective non-textual technique for qualitative research with children as it is not only more playful but, unlike interviews, it is not dependent on the language proficiency of the participant. In the My Village exercise pupils 7–9 years of age made postcards: on one side of the card, they drew 1or 2 places in their village that were the most important to them and on the other side wrote their name, village and age. Older children (10–11 years of age) were asked to draw a map of their village and include the places that were most important to them.

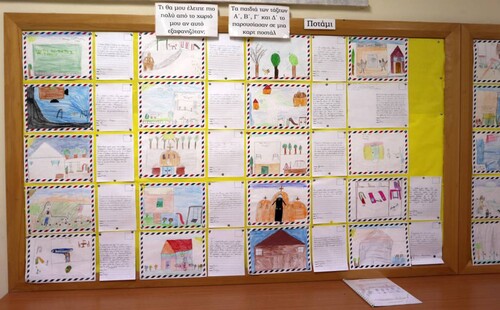

In total, 80 pupils from five different villages participated in the My Village exercises. Their maps and postcards highlighted the diversity of their rural villages and the complexity of their attachments (see ). Images included both places and activities – old and new. Some children drew images of themselves in their village, thus providing a ‘birds-eye view’ of themselves in the act of being in their village. Maps and postcards included village football pitches and churches, houses belonging to grandparents and friends, picnic spots, backyard gardens, swings, and farm animals. Local village schools were commonly included in the maps. No longer educational institutions, they have been converted into community centres and village halls – places to play, have village festivals and community meetings.

Figure 2. Postcards made by children from Potami Village (Grade 1-4), exhibited as part of an end-of-school celebration at the Asinou Regional Primary School on 17 June 2017. Photograph: author.

The catalyst for the development of the Asinou Village Heritage Project arose when the teacher of the Grade 5 class asked her pupils: ‘why is the Asinou Regional Primary School not on any of your maps?’ The pupils explained that the school was not part of their village or community, it was separate. Concerned by this disconnect, the teachers and principal made the objective of the 2017–2018 school year to connect village communities with the regional school, ‘so that children can feel that the school is part of the community instead of something different and separate’ (Georgia Mylourdou, personal communication, November 2017).

The focus for this school initiative developed slowly and organically through informal discussions with teachers following the My Village school activities. It was over coffee and a discussion about my previous archaeological research in the area that I casually mentioned the presence of the abandoned village called Asinou. While a few teachers on staff had heard of this village, none had visited it or realized it is located just 750 metres to the southwest of the famous Asinou church – the official namesake of their school. The teachers quickly decided that the abandoned village would become the focus of a project that would address their concerns about school identity while introducing children to the history and archaeology of the area.

It should be noted that while the Asinou Village Heritage Project was designed collaboratively with the teachers at the Asinou Regional Primary School, my role shifted throughout the duration of the project. Initially, I focussed on co-designing and co-organizing school activities that would communicate what I had learned about the Asinou area (its archaeology and history) in my previous research in the region. I ‘checked-in’ regularly, visited classrooms, shared resources, and met with the teachers to help coordinate a field trip to the village of Asinou. As the project developed, students and their teachers became connected to Asinou through their own personal engagements (i.e. field trip to Asinou; researching) and my ‘checking-in’ was no longer necessary. Their individual and collective experiences drove the project forward. As you will note in the pages that follow, my role shifted from active participant to research consultant then audience – someone to witness what they had accomplished and share in their pride. As Daglish (Citation2013, 7) and Nevell (Citation2013, 72–73) remind us, collaborative relationships with communities are dynamic; they shift throughout a project’s lifetime. My changing role in the project is one of its ‘success stories’ that marks its shift from a community-engaged project based on a partnership to one that is community-driven and under citizen control (see S. Arnstein’s Ladder of Public Involvement Citation1969, 221–224).

Asinou Village

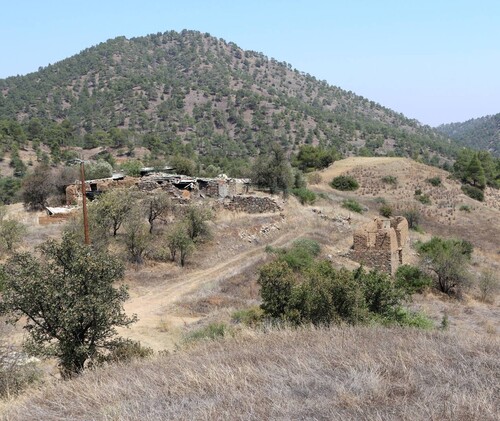

Today, the village of Asinou exists as an enclave of privately-owned land surrounded by the Adelphi State Forest (see ). It is in various states of decay with ruins consisting of multiphase mudbrick buildings, two ovens, three threshing floors and the remains of at least one sheep or goat enclosure (Ireland in Gibson Citation2013, 221–226). These physical remains indicate its use and reuse in the 18th through the 20th centuries while Venetian and Ottoman taxation records attest to its more distant past as a sixteenth-century estate (Grivaud Citation1998: 469; Ankara Tapu ve Kadastro Arşivi, T.T. 64). Up until the 1950s, the people of Asinou drew on forestry resources (producing resin, felling timber, grazing goats and collecting wood) to make a living. State Forests were created in 1881 when the island was under the British Colonial Administration. Throughout the island, all uncultivated lands including scrub, forest and brushwood became protected forests at this time (Given Citation2002, 14, Citation2004, 73–79). This ‘protection’ meant that inhabitants were no longer legally allowed to access the forestry resources that sustained them. Many villages and seasonal settlements located in the forest were abandoned and gradually their populations relocated to neighbouring villages located outside of the forest.

At Asinou, inhabitants resisted the forestry laws for as long as they could but by 1950 most villagers had moved to the plains, settling in villages like Nikitari where they turned to agriculture. As discussed elsewhere, this physical clearance of people from the forest had long-term social effects on how people connected to the forest and its past places (see Gibson Citation2019).

Asinou: From abandoned village to heritage place

Physical interaction with places, things and activities of the past is an important part of making heritage places. Therefore, the teachers of Asinou Regional Primary School and I designed a programme of activities (both in-school and at Asinou) that gave pupils ‘a direct and vivid experience with the past’ – what Jones (Citation2016, 138) sees as one of the strengths of heritage education. These experiences (e.g. exploring an abandoned village on foot, listening to stories, holding a pottery sherd in your hand) stimulate both emotion and imagination and facilitate the creation of new relationships with the past (Bagnall Citation2003; Smith Citation2006; Smith and Campbell Citation2016). By engaging the senses, they create new forms of knowledge and different ways of seeing (Pink Citation2015, 113–115).

Heritage work: Classroom and archaeological survey

The first activity was a classroom-based presentation with a ‘hands-on’ pottery component led by Dr Smadar Gabrieli (Troodos Archaeological and Environmental Survey Project (TAESP) pottery specialist 2003–2004; and Marie Skłodowska Curie Research Fellow, The Saxo Institute, University of Copenhagen), the aim of which was to introduce pupils to different ways of coming to know and understand the past (e.g. archaeological survey, excavation, ethnography and oral history). Whenever possible we used examples that highlighted relationships between the past/present and tangible/intangible in order to communicate the permeability of these categories. For example, we discussed the use and style of cooking pots in the past and present, their inheritance through women in the recent past and continued use in meals and social gatherings. We also used this opportunity to introduce students to the history and archaeology of the Asinou River Valley and to share findings of the Troodos Archaeological and Environmental Survey Project (TAESP; Given et al. Citation2013a, Citation2013b).

The field trip to the Asinou River Valley (the location of Asinou church and village) with the Grades 5 and 6 classes (40 pupils), the principal, and several teachers from the regional primary school took place two days after the ‘in-school’ heritage presentation. It included a demonstration of an archaeological survey, a discussion of the history and archaeology of the area and a tour of the abandoned village of Asinou with storytelling by Mr Panagiotis Alexandrou Loppas, an Elder who had grown up in the village.

With the permission of the Cyprus Department of Antiquities, a mock archaeological survey took place to the southeast of Asinou Church in a field previously surveyed and recorded through the TAESP Project (see Gibson Citation2013, 215–219). Students used knowledge gained from the classroom session to locate and identify different types of surface pottery. Many were surprised to find sherds from storage vessels and roof tiles – evidence that a structure with storage facilities once stood there. We used this exercise as the starting point for discussion about how people used to live in the Asinou River Valley in the distant and recent past.

Heritage work: Village tour

The tour of the abandoned village of Asinou was designed with the Grade 5 and 6 teachers to incite feelings in the students, spark their imagination and encourage their engagement with Asinou. Its multisensorial nature – walking, listening to stories, interacting with fellow classmates – helped to create a sense of empathy with the people who once lived in the village, while instilling in them a sense of commitment and desire to tell their story (Pink Citation2015; Jones Citation2010, 188–190; Smith and Campbell Citation2016, 446).

We chose Elder Panagiotis Alexandrou Loppas (past resident of the village) to guide the children through the village, sharing his stories and experience of living there as a child at their age (; link to video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = ziRAENdeNC8). The tour was the start of student-led research on the village. Prior to departure, pupils were assigned ‘fieldwork’ tasks: sketching, taking notes and photographs or using digital voice recorders to record the stories of Mr Loppas. At the time, I had no idea that their research would extend beyond this tour or that their interactions at/with the village would serve as a catalyst for future heritage ‘work’ and negotiations of identity.

Figure 4. Panagiotis Alexandrou tours Asinou Village with the Grade 5 and 6 classes of the Asinou Regional Primary School. Photograph: author.

The children arrived to Asinou on foot. Their 15-minute walk along the dusty road then up a small hill and along its spur to the site of the village created excitement among students, instilled a sense of adventure, and inadvertently reinforced the belief that Asinou was a remote and forgotten place.

Panagiotis started his tour with an introduction to the area – its history and significance. As the children sat among the ruins, he spoke about the origins of Asinou village, the legend of how it was founded by people from Asini Greece and how Nicephorus, the magistrate who built Asinou Church on his estate between the 11th and 12th centuries, became the monastery’s first abbot. A skilled storyteller, Panagiotis merged his accounts of the distant past with stories of his own past (see Gibson (Citation2019) for his use of story to revitalize connections with land, its places and ancestors). As Smith and Campbell (Citation2017, 617) state, nostalgia is a way of negotiating what the past means and which values should be brought forward into the present and future. Panagiotis took his position as guide seriously, making sure to tell the children why this village – and his place in it – mattered.

There is a close relationship between patina, emotion and feelings of authenticity. Certain old objects have an ability to connect people and places (past and present) to produce ‘sensations of proximity, interconnection and even identification’ with those who once lived in the past (Jones Citation2016, 134). Asinou is an atmospheric place that encourages imagining life there in the past. The ruins not only trigger the imagination but as Bagnall (Citation2003, 89) states, they invite you to feel something – what she calls ‘emotional realism’.

A mixture of old and new, some houses appear as if only recently abandoned with broken windowpanes and tin roofs while others look long-deserted with only stone foundations worn where their doors once hung. These ‘imprints of past lives’ collapse time and prompt one to enter a different world (see Gregory and Witcomb Citation2007, 265 for the introduction of this concept in the context of historic house museums). Jeremy Wells (Citation2017, 456, 465) might refer to this otherworldliness as the experience of ‘spontaneous fantasy’ – when a vignette of the past is triggered through the patina of an object or historic building.

Panagiotis guided the children through the village making sure to weave the disconnected and alien ‘things’ that made up the ruins together through his stories of growing up there as a child. He interacted with the ruins – pointed to where he once slept and acted out how his mother communicated with his aunt through a hole in their adjacent houses. He pointed to the roofless structures and named their owners making sure to outline connections to families currently living in the area. While none of the children were directly related to these past inhabitants, the pupils remembered family names and later wove them into their narrative of Asinou.

Guided by someone who lived in the village at their age made the past seem closer and more real. In their work on holocaust memorialization in Australia, Cooke and Frieze (Citation2017) speak of the transformative potential that holocaust survivor stories can have when told through face-to-face encounters. While the case is dissimilar, Panagiotis’ memories – the stories of daily life, poverty and resilience that he shared as he guided the teachers and schoolchildren through Asinou – were specifically chosen to make an impact, to create empathy and understanding amongst the children so that he and his ancestors would be remembered into the future. The tour (the places he stopped and stories he told) was an expression of identity, a call for recognition and a future action – it was part of his resistance to forgetting (see Gibson Citation2019).

The students were not passive consumers of Panagiotis’ stories. As the children moved through the village together listening to his stories, interacting with their teachers, the ruins and each other, they were actively creating their own narratives and memories. For example, sitting together in a clearing to the south of the main cluster of mudbrick buildings listening to the history of Asinou, some were more attentive than others. As they grew increasingly restless, they interacted more with their surroundings and each other – long pieces of dead grass were used to tickle the ears of those sitting nearby, others took the opportunity to braid hair, or used sticks to inscribe designs into the hardened dirt. Teachers too were distracted as they watched over the students making sure that they were listening and behaving appropriately. I later realized that this collective experience held as much emotional weight and historical significance as the information being conveyed by Panagiotis – it was part of the affective encounter that made Asinou into a meaningful place – one that included their own experiences. The feeling of empathy for those of the past created through their engagement at Asinou combined with their own personal experiences entwined the children in a powerful relationship with the abandoned village and each other while also fuelling their future heritage work.

Heritage work: Research

As mentioned earlier, the guided tour of Asinou village became the first stage and catalyst for the intensification of Grade 5 student-led research on the village. My role in this project quickly shifted from co-organizer to research advisor – a role later formalized when the student research project was later entered into the 2017–2018 Research and Innovation Foundation’s annual ‘Students in Research Contest’ seven months later.

The Asinou Village Heritage Project took place over the course of seven months. The teachers designed the research project with three main objectives: to find out who in their communities knew about Asinou village and what they knew; to collect new information about the village; and to learn the skills of doing research. The pupils and teachers created and distributed a questionnaire to 100 of the relatives of children at the school to find out who knew about the abandoned village. Of those that responded, 16 had ‘no knowledge’ of the village, 50 had ‘little knowledge,’ and 4 had a ‘rich knowledge’ of Asinou. Those with ‘rich knowledge’ were interviewed, their narratives were transcribed, summarized, and added to information collected from the guided walk with Panagiotis. Data from published sources such as archaeological reports (e.g. settlement and land-use data from the medieval to modern period) and archival accounts from the State Archives (e.g. records of shepherds living at Asinou) gave a greater breadth and time depth to this ethnographic knowledge. Children learned the process of carrying out qualitative research: how to create a questionnaire, develop interview questions, carry out and transcribe interviews, interpret and present different types of data.

This research was a sustained act of heritage-making. The physical and emotional attachment to Asinou created in the initial field trip made teachers and pupils not only committed to telling the story of Asinou’s past but to establishing their own position within that history. As Smith (Citation2006, 75) states, ‘[h]eritage is about a sense of place. Not simply in constructing a sense of abstract identity, but also in helping us position ourselves as a nation, community or individual and our ‘place’ in our cultural, social and physical world’. Researching plays an important role in creating feelings of belonging as illustrated by Mills, Simpson and Geller’s (Citation2019, 186) in community-based Industrial Devon project where research conducted with Scottish primary schools on Industrial Devon generated a sense of pride that spread from pupils to their families.

Through the process of researching Asinou the children and their teachers not only recognized the significance of the story they were telling but the important role they played in its telling. Researching (interviewing, listening, reading and interpreting) changed how they connected with this heritage place. It transformed the school’s Asinou Village Heritage Project into something more personal – a project about who they were and where they came from.

Researching is part of the process of deciding what values from the past and present to preserve and pass on into the future (Smith and Waterton Citation2009, 76). The below two quotes from Skevi and Georgia Mylordou (the main project organizers) illustrate how the process of carrying out research created new networks of relationships not only among the pupils and the abandoned village but among families, villages, teachers and the school. It had a ripple effect throughout their villages as questionnaires and interviews of family members initiated cross generational and intergenerational learning.

One of the things that particularly impressed me was that the students, from the moment they studied about Asinou, they immediately considered this as something that belonged to them (that concerned them). The more they gathered information about the village, interviews from their grandparents, and they understood that it was something their parents, grandparents, uncles and aunts were interested in as well, they felt themselves more connected with the school and also Asinou. (Skevi Mylordou, May 2018)

What impresses me is that the children have really become researchers … . The students often overturned the way I was scheduling the lesson and the research. They were telling me ‘Misses I just asked my grandmother who is from Lagoudera and she told me that in Lagoudera people didn’t face the same problem as in Asinou because there they used to take their animals into the lands that they owned.’ They became researchers; they came to love their place. (Georgia Mylordou, May 2018)

The Grade 5 class reworked the past and gave it meaning that suited their contemporary and future needs (see Smith and Waterton Citation2009, 76). Projects like the Asinou Village Heritage Project can, as Jones (Citation2013, 169) suggests, provide arenas for the negotiation and creation of community identities and memories. This became apparent when I interviewed the students and asked ‘do you think that Asinou is an important place? If so, then what makes it important?’ Their answers outlined below indicate that Asinou had become both the physical anchor and social place on which to create a new identity and sense of belonging (Smith Citation2006, 75).

It is important because there used to live grandpas and grandmas that loved their village, and this is very important for our ancestors.

What makes it important for me is that many years ago there used to live our ancestors.

Because it is very near to us and people have left the village of Asinou and came here, to our region, for example to Potami, Nikitari, Vyzakia

It is important because our school’s name comes from the name of that village.

I think it is important because it is our school’s name.

The responses of other children highlight the complexity of the heritage-making process and its link to the negotiation of social and cultural values. For two children it was the absence of knowledge or memory of Asinou that made it an important place: Asinou is important because it ‘is a village of our area and people should know about their heritage’ (Boy 2); ‘it is important because we are so near to this village and we didn’t know about it’ (Girl 4). Their responses suggest a sense of obligation or responsibility to learn and remember (or at least not forget) local heritage places – a theme reiterated by their teacher Georgia Mylordou who, as mentioned earlier, equated pupil’s desire to research and ask new questions about their local area with a newfound love for ‘their place’.

Telling their story: Heritage performance

In November 2017, Georgia Mylordou entered her Grade 5 class’ research into the National ‘Students in Research Contest’ or ΜΑΘΗΤΕΣ ΣΤΗΝ ΕΡΕΥΝΑ – ΜΕRΑ 2017–2018 (in cooperation with the Centre of Educational Research and Assessment and Ministry of Education and Culture, Republic of Cyprus) under the title ‘Tracing our Cultural Heritage’. As finalists in the competition, her class was invited to present their research to the adjudication committee in the State capital of Nicosia in May 2018. They presented their story in the auditorium at the Journalists House to a panel comprised of members from the Department of Education, University of Cyprus, Ministry of Education, and Research and Innovation Foundation. Standing on the stage, each pupil took their turn presenting a segment of their well-rehearsed story, then answered questions posed by the committee. In June they received notice from the Ministry of Education that they had won the contest.

The significance of this presentation (and those formal and informal presentations that followed) went far beyond knowledge translation. Identities and memories were negotiated through the process of creating, practicing, and presenting their research. As with any heritage negotiation, this process was embedded in power relationships, for example: how would they articulate their story? What parts would be left in or taken out? Creating and performing the presentation was both part of transforming Asinou into a ‘place’ and gaining recognition of that place – making their story legitimate and their heritage ‘official’. Not only had the children and teachers written themselves into the history of Asinou through their research, but this formal presentation also gave their story voice beyond their rural villages to ‘officials’ in the capital of the country – Nicosia.

As Laurajane Smith states, heritage can be used to define and legitimize identity but also to validate the ‘experiences and social/ cultural standing of a range of subnational groups’ (Smith Citation2006, 52). By presenting Asinou as a heritage place with a rich past, the teachers and children were also establishing the strength and significance of the people and villages with pasts rooted in Asinou. In this way, the presentation was as much about their rural villages gaining recognition from the State as it was about the abandoned village of Asinou or the regional primary school.

The process of making their heritage visible gave the Grade 5 pupils a sense of pride in place and self. Two weeks after the ‘Students in Research’ competition I asked two pupils how they had felt presenting their research on Asinou to the public. Their responses are an important reminder of how deeply the experience of doing heritage work can impact identity and feelings of belonging.

We are proud about that and we feel that it is really important … We feel part of the society and that we offer a contribution to society with this research.

I agree with my classmate, but I would like to add that we are lucky as well to have worked on a historical village … There are people who don’t know about the village, it is good to know.

At the end of their presentation the head of the Nikitari Community Council, Mr Kyriakos Alexandrou, stood, congratulated the children and teachers on their research and presentation and then publicly committed money to support publishing their research as a book. The other village councils quickly followed suit. Asinou village had ceased being an ‘abandoned’ or ‘forgotten’ village. The heritage work of the pupils, their teachers, families, and communities mobilized the place and its past inhabitants. One year later (May 2019) the book, The Settlement of Asinou: Tracing our Cultural Heritage (Ο ΟΙΚΙΣΜΟΣ ΤΗΣ ΑΣΙΝΟΥ Ιχνηλατηση πολιτιστικης κληρονομιας), was published and their story of the abandoned village of Asinou became ‘official’ heritage ().

Reflecting on the Asinou Village Heritage Project

Even though the Grade 5 teacher no longer teaches at the school, and the pupils who carried out the research now attend secondary school, the connection to Asinou remains – it is a heritage place. As Bagnall (Citation2003, 93) states, reminiscing reawakens past experiences and creates new connections between the past and present. In the classroom teachers tell Panagiotis’ stories about life at Asinou and young children in Grade 2 and 3 who heard of the Grade 5 research and field trip from elder brothers and sisters press their teachers to take them to visit Asinou to see and experience the place for themselves (Skevi Mylordou, personal communication, June 2019).

In 2017 the Asinou Regional Primary School’s goal was to connect the local villages with the school so that, as teacher Georgia Mylourdou states, ‘children can feel that the school is part of the community instead of something different and separate’. It is not clear that this was achieved. The regional school is located outside of their individual village boundaries and as such will likely always be geographically and socially separate from their villages – it is not an integral part of their lived village landscape.

The real challenge that the school faced, and managed to address, was a lack of collective identity and a feeling of belonging among pupils at the school. Through their heritage work – the field trip, research, presentation – they created a narrative that wove themselves and their regional school into a unique local history. The process of doing this work created new connections among Asinou village, the pupils, their families, and communities. The children created shared memory and common history that connected villages of the area by anchoring them to Asinou – the place of their ancestors. They made this past visible within their rural area and beyond through presentations in the State Capital Nicosia and the publication, The Settlement of Asinou: Tracing our Cultural Heritage.

I learned through working with the teachers at the Asinou Regional Primary School that truly collaborative heritage projects need to be given the space and time to develop organically. The Asinou Village Heritage Project emerged through the process of developing relationships with the teachers at the primary school – informal discussions around their staffroom table and brainstorming sessions over coffee in Nicosia. While the initial impetus for the project came from me through the ‘My Village’ activities and latterly the co-organized field trip to Asinou village, the project would never have developed without the interest, enthusiasm and commitment of the teachers and principal at the Asinou Regional Primary School. Skevi Mylordou (Grade 2 teacher) and Georgia Mylordou (Grade 5 teacher), sisters and residents of Vyzakia, designed, organized and implemented the research programme and submitted it to the ‘Students in Research Contest’ and I enthusiastically took on the role of an advisor and witness to their heritage-making. As ‘locals’ living within the catchment area of the school, they both had a vested interest in the research and a commitment to the area (past, present and future). It is difficult to determine if the project would have developed without them.

Conclusion: Building resilience through heritage work

The villages of Nikitari, Potami, Vyzakia, Kannavia, Agia Marina, Agios Georgios Kafkalou, and Xyliatos are in rich agricultural areas at the intersection of forested mountains and plains. While they are accessible by car and serviced by bus they are geographically and, in many ways, ideologically at the ‘end of the road’. Each of these villages faces similar social and economic challenges as their populations decline. To survive they will increasingly have to adapt and innovate. Creating strong internal relationships and networks to connect these villages is a necessary step toward their resilience.

Regional primary schools, like the Asinou Regional Primary School, may be best located to create the social networks necessary to build resilience in rural areas. Loizos Symeou’s (Citation2008, 20) research on teacher-parent networks in rural and urban Cyprus found that rural parents hold an ‘ideal of a teacher who spends more time, if possible even resides in the community’. They see teachers as community stakeholders that should not only play a role in the development of the school, but in the broader community – feelings that have their roots in the past when schools and their teachers were embedded in the rural village (Symeou Citation2008, 20). The parents interviewed in Symeou’s (Citation2008, 20) study were critical of the growing number of teachers who live in the city but commute to rural schools for work as they do not contribute to the local area. They see this shift as a recent change because of rural depopulation.

While teachers and their schools are no longer embedded in village life as they once were, the Asinou Village Project illustrates the potential for regional schools to become centres for the creation and maintenance of relationships that crosscut individual village boundaries. Local community leaders may already be actively involved in regional schools as is the case at the Asinou Regional Primary School where presidents from local community councils and village priests take part in school celebrations and support local school initiatives like funding the publication of The Settlement of Asinou: Tracing our Cultural Heritage. Heritage projects based at regional schools but codesigned with local community councils and community leaders may create new relationships, shared identities and a sense of belonging among pupils, their families and villages – elements that are threatened by the shrinkage of rural economies and subsequent depopulation of villages. Relationships of trust, shared values and feelings of belonging created among school children, their families and community leaders are the social capital that is necessary to respond to change. As Li, Westlund, and Liu (Citation2019, 141) state, the ‘development capability of communities is strengthened and the local social capital is enhanced when increased unity, cooperation and trust is developed among the villagers. Then, the local social capital can serve as a platform for collaboration and interplay with different external actors and sectors.’

The impact of heritage initiatives on those living in rural areas should not be underestimated. At the Asinou Regional Primary School, the teachers and pupils created their own narrative of Asinou that started with the embodied experience of visiting (engaging with the place, its material remains and each other) the ruined village and listening to the stories of Mr Panagiotis Loppas. This is known pedagogically as experiential learning. The relationships they made with the past and present through these interactions fuelled their desire to research this place, to rework its past, and tell their story.

By its very nature, experiential education is ‘designed to empower’ (Shellman Citation2014, 19). As Shellman states, empowerment includes a ‘sense of personal control, or agency, including the belief that one’s actions will result in a desired outcome’ (Citation2014, 21). When this experience focusses on creating relationships with your own past (i.e. generating and presenting knowledge) the results can be transformative – creating confidence, pride and instilling the belief that your actions can make a difference beyond the classroom or village. This was made clear by one Grade 5 pupil who said, ‘we feel part of the society and that we offer a contribution to society with this research’. To me, this is the most important lesson that the teachers at the Asinou Regional Primary School taught – the power of research to enliven the past and enact change for the future.

While it is still too soon to determine whether the skills, confidence and connections instilled through the heritage work of the teachers and pupils of the Asinou Regional Primary School is strong enough to serve as a catalyst for future regional initiatives among the rural villages of the area, Asinou remains a site of local heritage and a focal point for collective memory.

Following the MERA competition, the Asinou Regional Primary School applied for (and was awarded) an EU Erasmus + School Exchange to work with rural schools in France, Italy, Croatia, Romania and Spain. This EU-funded educational programme includes student exchanges and teacher training. It brings together the teachers and students of similar-sized rural schools where they share local histories, literature, music, dance, art, cultural traditions and foodways (for details see https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2018-1-CY01-KA229-046851). They named their Erasmus programme ‘Tracing our Cultural Heritage’.

In the spring of 2020 students from partnered schools were meant to visit Cyprus and stay with the pupils from the Asinou Regional Primary School as the finale to this project. They aimed to introduce the history of Cyprus and the local area through a tour of the abandoned village of Asinou led by the current and past Grade 5 classes. Asinou was integral to the negotiation of their local and national identities.

The COVID-19 pandemic made this final student and teacher exchange to Cyprus impossible. After several postponements, a ‘virtual’ trip to Cyprus took place on 7–9 December 2020. Over the course of two days the partnered schools, their teachers and pupils met online to hear presentations from the Asinou Regional Primary School; two of which focussed on the village of Asinou. In the first, a teacher led her class and audience through the research process – how data were collected on the abandoned village of Asinou. The other presentation was led by me.

Now attending secondary school, it was too difficult to involve the previous Grade 5 students in leading a virtual field trip (COVID-19 health regulations, limitations of Wi-Fi technology, access to computers). I was therefore asked to share what I knew about Asinou Village and the surrounding area – its history and archaeology – take pupils to the village virtually. I embedded video and audio into my presentation, spoke about the smells and sounds of Asinou village and the surrounding landscape in a desperate attempt to give students a sense of being at Asinou. It didn’t work. Not only was I presenting my Asinou – my sense of the place based on the visceral experience of having been there – but relationships with the past emerge through personal experiences. Someone showing you a place is important (especially when communicated online) is not enough to build meaningful connections.

The finale of the ‘Tracing our Cultural Heritage’ EU Erasmus+ Student Exchange was disappointing for everyone. The final presentations were a top-down approach at odds with the student-led nature of the Asinou Village Project, but they were a necessary substitute in a period of economic and social disruption. While there is heritage and identity work that did not take place because partnered schools did not come to Cyprus, relationships (friendships, partnerships) have been established among teachers, pupils, and their families through pre-COVID-19 exchanges and joint school projects. These connections may be the stimulus for innovation in their rural communities offering new perspectives, ways of adapting to, and enacting change.

The heritage work of the Asinou Regional Primary School is a poignant reminder of the power of grassroots initiatives to affect change. While the futures of the rural villages of Kannavia, Agia Marina, Agios Georgios Kafkalou, Xyliatos, Nikitari, Potami and Vyzakia are uncertain, it is wonderful to think that the seeds for their revitalization may have been planted at an abandoned village through the care of an Elder, a Grade 5 class and its teacher.

Acknowledgment

This research was conducted through a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Research Fellowship in Archaeology at the University of Glasgow, Scotland. I am grateful to Cyprus' Department of Antiquities and the Department of Forests who were both valuable partner organisations in this research. Permission to undertake collaborative research at the Asinou Regional Primary School as part of the ‘Pathways to Heritage Project’ was granted by the Ministry of Primary Education, head teachers Mr. Michael Michael (2017), Ms. Poly Hadjiprokopiou (2018-19) and the parents/guardians of the Grade 5 class. The Asinou Village Heritage Project was co-developed with the Asinou Regional Primary School but galvanized by the Grade 5 and Grade 3 teachers Georgia and Skevi Mylourdou. I am grateful to Elder Panagiotis Alexandrou whose stories not only enlived Asinou Village but inspired a new generation of memory-making. Invaluable assistance with classroom activities was provided by Aikaterini Vitsadaki, Doria Nicolaou, Chrystalla Loizou and Andri Evripidou while Varvara Stivarou and Manto Papadopoulou transcribed and translated interviews for the project. Thank you to the editors and two anonymous reviewers whose comments helped to improve this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Erin S. L. Gibson

Erin Gibson held a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Research Fellow in Archaeology at the University of Glasgow, Scotland (2016-18) where she maintains affiliate researcher status. She is an associate member of the Centre for Environment, Heritage and Policy at Stirling University, Scotland and holds adjunct status in Anthropology at the University of Northern British Columbia, Canada. Her community-engaged research draws on ethnographic and archaeological techniques to address heritage-making in contested landscapes (Canada, Cyprus).

Notes

1 I first worked in the Asinou area as part of the Troodos Archaeological and Environmental Survey Project (2000–2004) and my PhD research (2000–2004) on communication routes in the area. The PATH Project was designed in response to these top-down projects that drew on the knowledge of the local population without engaging them in the design of research questions. For more information on the context of PATH, see Gibson Citation2019, 2–3.

References

- Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224.

- Attalides, Michael. 1981. Social Change in Cyprus: A Study of Nicosia. Publication of the Social Research Centre 2. Nicosia: Social Research Centre.

- Bagnall, Gaynor. 2003. “Performance and Performativity at Heritage Sites.” Museum and Society 1 (2): 87–103.

- Byrne, Denis. 2008. “Heritage as Social Action.” In The Heritage Reader, edited by Graham Fairclough, Rodney Harrison, John Jameson, and John Schofield, 149–173. New York: Routledge.

- Byrne, Denis, Helen Brayshaw, and Tracy Ireland. 2001. Social Significance: A Discussion Paper. Hurstville: NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service.

- Cooke, Steven, and Donna-Lee Frieze. 2017. “Affect and the Politics of Testimony in Holocaust Museums.” In Heritage, Affect and Emotion: Politics, Practices and Infrastructures, edited by Divya P. Tolia-Kelly, Emma Waterton, and Steve Watson, 75–92. London: Routledge.

- Daglish, C. 2013. “Archaeologists, Power and the Recent Past.” In Archaeology, the Public and the Recent Past, edited by Chris Daglish, 1–10. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer Inc.

- European Commission. 2017. Modernising and Simplifying the CAP. Socio-Economic Challenges Facing Agriculture and Rural Areas. Brussels: Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development, European Commission.

- Giannakis, Elias. 2014. “The Role of Rural Tourism on the Development of Rural Areas: The Case of Cyprus.” Romanian Journal of Regional Science 8 (1): 38–53.

- Gibson, Erin. 2013. “The Mountains.” In Landscape and Interaction. The Troodos Archaeological and Environmental Survey Project, Cyprus. Volume 2: The TAESP Landscape. Levant Supplementary Series, edited by Michael Given, A. Bernard Knapp, Jay Noller, Luke Sollars, and Vasiliki Kassianidou, 204–242. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Gibson, Erin. 2019. “Resisting Clearance and Reclaiming Place in Cyprus’ State Forests Through the Work of Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 26 (7): 700–716 doi:10.1080/13527258.2019.1693415.

- Given, Michael. 2002. “Maps, Fields and Boundary Cairns: Demarcation and Resistance in Colonial Cyprus.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 6 (1): 1–22.

- Given, Michael. 2004. The Archaeology of the Colonised. London: Routledge.

- Given, Michael, Bernard Knapp, Jay Noller, Luke Sollars, and Vasiliki Kassianidou, eds. 2013a. “Landscape and Interaction.” In The Troodos Archaeological and Environmental Survey Project, Cyprus. Volume 1: Methodology, Analysis and Interpretation. Levant Supplementary Series 14. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Given, Michael, Bernard Knapp, Jay Noller, Luke Sollars, and Vasiliki Kassianidou, eds. 2013b. “Landscape and Interaction.” In The Troodos Archaeological and Environmental Survey Project, Cyprus. Volume 2: The TAESP Landscape. Levant Supplementary Series 15. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Gregory, Kate, and Andrea Witcomb. 2007. “Beyond Nostalgia: The Role of Affect in Generating Historical Understanding at Heritage Sites.” In Museum Revolutions: How Museums Change and are Changed, edited by Sheila Watson, Suzanne MacLeod, and Simon Knell, 263–275. London: Routledge.

- Grivaud, Gilles. 1998. Villages Desertes a Chypre (Fin XII - Fin XIX Siecle). Nicosia: Archbishop Makarios III Foundation.

- Harrison, Rodney. 2015. “Beyond ‘Natural’ and ‘Cultural’ Heritage: Toward an Ontological Politics of Heritage in the Age of Anthropocene.” Heritage and Society 8 (1): 24–42.

- Johnston, Robert, and Kimberly Marwood. 2017. “Action Heritage: Research, Communities, Social Justice.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 23 (9): 816–831.

- Jones, Siân. 2010. “Negotiating Authentic Objects and Authentic Selves. Beyond the Deconstruction of Authenticity.” Journal of Material Culture 15 (2): 181–203.

- Jones, Siân. 2013. “Dialogues Between Past, Present and Future: Reflections on Engaging the Recent Past.” In Archaeology, the Public and the Recent Past, edited by Chris Daglish, 163–175. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer Inc.

- Jones, Siân. 2016. “Unlocking Essences and Exploring Networks. Experiencing Authenticity in Heritage Education Settings.” In Sensitive Pasts. Questioning Heritage in Education, edited by Carla van Boxtel, Maria Grever, and Stephan Klein, 130–152. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Kindon, Sara, Rachel Pain, and Mike Kesby. 2007. “Participatory Action Research: Origins, Approaches and Methods.” In Participatory Action Research Approaches and Methods. Connecting People, Participation and Place, edited by Sara Kindon, Rachel Pain, and Mike Kesby, 9–19. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Li, Yuheng, Hans Westlund, and Yansui Liu. 2019. “Why Some Rural Areas Decline While Some Others Not: An Overview of Rural Evolution in the World.” Journal of Rural Studies 68: 135–143.

- Literat, Ioana. 2013. “‘A Pencil for Your Thoughts’: Participatory Drawing as Visual Research Method with Children and Youth.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 12 (1): 84–98.

- Magis, Kristen. 2010. “Community Resilience: An Indicator of Social Sustainability.” Society and Natural Resources 23 (5): 401–416. doi:10.1080/08941920903305674.

- Mills, Catherine, Ian Simpson, and Jennifer Geller. 2019. “Industrial Devon: Reflections and Learning from Schools-Based Heritage Outreach in Scotland.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 6 (3): 172–188.

- Markey, Sean, Greg Halseth, and Don Manson. 2008. “Challenging the Inevitability of Rural Decline: Advancing the Policy of Place in Northern British Columbia.” Journal of Rural Studies 24: 409–421.

- Nevell, Micheal. 2013. “Archaeology for All: Managing Expectations and Learning from the Past for the Future – the Dig Manchester Community Archaeology Experience.” In Archaeology, the Public and the Recent Past, edited by Chris Daglish, 65–75. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer Inc.

- Pink, Sarah. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. 2nd Edition. London: Sage Publishing.

- Salvia, Rosanna, and Giovanni Quaranta. 2017. “Place-Based Rural Development and Resilience: A Lesson from a Small Community.” Sustainability 9 (6): 1–15.

- Shellman, Amy. 2014. “Empowerment and Experiential Education: A State of Knowledge Paper.” Journal of Experiential Education 37 (1): 18–30.

- Smith, Laurajane. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge.

- Smith, Laurajane, and Gary Campbell. 2016. “The Elephant in the Room.” In IA Companion to Heritage Studies, edited by William Logan, Máiréad Nic Craith, and Ullrich Kockel, 443–460. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/9781118486634.ch30.

- Smith, Laurajane, and Gary Campbell. 2017. “Nostalgia for the Future: Memory, Nostalgia and the Politics of Class.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 23 (7): 612–627. doi:10.1080/13527258.2017.1321034.

- Smith, Laurajane, and Emma Waterton. 2009. Heritage Communities and Archaeology. London: Duckworth.

- Symeou, Loizos. 2008. “From School-Family Links to Social Capital. Urban and Rural Distinctions in Teacher and Parent Networks in Cyprus.” Urban Education 20 (10): 1–27.

- Wells, Jeremy C. 2017. “How are Old Places Different from New Places? A Psychological Investigation of the Correlation Between Patina, Spontaneous Fantasies and Place Attachment.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 23 (5): 445–469. doi:10.1080/13527258.2017.1286607.