?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

How do people explain persistent inequality between whites and blacks? Research has focused on two dimensions of explanation, or attribution: internal (regarding shortcomings in black motivation and capability); and external (regarding the socioeconomic context). We argue that a third type of attribution – cultural – augments internal attributions, making them more compelling. A survey-based experiment with a white sample showed that internal attributions elicited greater agreement when framed in cultural terms – that is, when black character and behavior were linked to a distinct black culture. High knowledge participants responded more strongly to framing than low knowledge participants. Culturally framed internal attributions predicted issue attitudes more powerfully than traditional internal attributions. The results indicate that we should change how we conceptualize and measure public beliefs about racial inequality.

Introduction

This story isn’t about the loss of life, but a loss of living, of wealth and prosperity and possibilities that still reverberates today … Imagine all those hotels and diners and mom-and-pop shops that could have been passed down this past hundred years. Imagine what could have been done for Black families in Greenwood: financial security and generational wealth.

US President Joe Biden made the above remarks during a June 1, 2021 commemoration of the 100th anniversary of a destructive racist attack on the prosperous black neighborhood of Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma (Biden Citation2021). Biden drew attention to how racism has impeded black economic progress and contributed to the substantial, persistent wealth and income gap between black and white Americans (Creighton and Wozniak Citation2019; Hunt Citation2007). Racial inequalities in standards of living are mirrored by a disproportionate representation of African-Americans among the less educated and the incarcerated (Walton, Smith, and Wallace Citation2020). Like Biden, many Americans attribute racial inequality to external forces such as prejudice, discrimination, and lack of opportunity, while others attribute racial inequality to forces that are internal to blacks: poor motivation, a penchant for violence, and substandard skills and abilities (Drakulich Citation2015; Kluegel Citation1990; Kluegel and Bobo Citation1993; Knight Citation1998; Shelton Citation2017).

This internal-external dimensional framework dominates research on the white public’s attributions for racial inequality. We call for a substantial change in the conceptualization and measurement of political attributions to bring culture into the framework. Previous investigations have argued that culture amounts to a separate, independent attributional dimension of its own. In other words, people believe that inequality is due to external, internal, or cultural forces. Our view merges internal and cultural forces into a single hybrid dimension. We believe culturally framed internal attributions better represent white Americans’ thoughts about racial inequality than internal attributions absent a cultural frame. We present two findings to support this claim. First, white Americans found culturally framed internal attributions more convincing explanations for racial inequality than internal attributions without a cultural frame. Second, culturally framed internal attributions better predicted attitudes on race-relevant policies than internal attributions sans a cultural frame.

The attributions we make, both for specific events like a school shooting, and for general conditions like racial inequality, carry important political consequences (Joslyn and Haider-Markel Citation2013; Nelson Citation1999; Sahar Citation2014; Weiner, Osborne, and Rudolph Citation2011). The belief that blacks themselves are mostly or entirely responsible for their disadvantaged economic status, for example, is among the strongest predictors of opposition to welfare policies (Gilens Citation1995). By better capturing the attributions for racial inequality, we will achieve a more complete understanding of the micro-foundations of contemporary racial politics.

Attributions for racial inequality

Research on attributions for racial inequality in standards of living evolved from the scholarly inquiry into public understanding of poverty (Bennett, Raiz, and Davis Citation2016), and has largely echoed that early literature’s emphasis on an internal and external attributional structure (Bobo and Kluegel Citation1993; Hopkins Citation2009; Hunt Citation2007; Mijs Citation2018; Shelton Citation2017; Sniderman and Hagen Citation1985; Tuch and Hughes Citation1996). The General Social Survey racial inequality battery, for example, has featured two internal items (“Most blacks have less in-born ability to learn” and “Most blacks just don’t have the motivation or willpower to pull themselves up out of poverty”) and two external items (“Discrimination” and “Most blacks don’t have the chance for education that it takes to rise out of poverty”) (Bobo and Kluegel Citation1993; Hopkins Citation2009; Shelton Citation2017).

Research on attributions for racial disparities in the criminal justice system also adopts the internal and external dimensional framework (Drakulich Citation2015; Johnson Citation2007; Mullinix and Norris Citation2018; Pickett and Ryon Citation2017; Unnever Citation2008). Peffley, Hurwitz, and Mondak (Citation2017), for example, used a four-item measure of attributions for racial disparities in arrest and imprisonment. Two items are internal (“Blacks are more aggressive by nature” and “Blacks are just more likely to commit crimes”), and the other two external (“The police are biased against blacks” and “The courts and justice system are stacked against blacks and other minorities”).

Attributions for racial inequality are no mere passing fancies; they relate to attitudes on a number of issues that touch on race, both explicitly and implicitly (Huddy and Feldman Citation2009). Blaming inequality on insufficient motivation among blacks predicts opposition to government policies designed to increase opportunities and improve living standards among blacks (Bobo and Kluegel Citation1993; Kinder and Sanders Citation1996). Attribution of racial inequality to discrimination, on the other hand, predicts support for these ameliorative policies (Hughes and Tuch Citation2000; Tuch and Hughes Citation1996). The belief that a poor work ethic explains black poverty even predicts support for more punitive criminal justice policies (Wheelock, Wald, and Shchukin Citation2012).

Internal attributions for criminal behavior (without regard to race) predict more punitive attitudes, while external attributions predict leniency (Carroll et al. Citation1987). Peffley, Hurwitz, and Mondak (Citation2017) found that, among whites and latino/as, internal attributions for racial inequality with respect to crime predicted greater support for the death penalty when participants had been told about racial disparities in punishment (see also Peffley and Hurwitz Citation2007). Stereotypes of blacks as lazy and violent predict support for more punitive crime policies (Hawkins Citation1981; Peffley and Hurwitz Citation2002), while beliefs that blacks are treated unfairly by the criminal justice system predict less punitive attitudes (Johnson Citation2008). Whites who view blacks as predisposed to criminal behavior express more support for the police (Mullinix and Norris Citation2018).

Enter culture

Some have argued that “old-fashioned” notions of inherent black inferiority have recently yielded to a sense among whites that African-American culture is somehow deficient (Bobo, Kluegel, and Smith Citation1997; Bonilla-Silva Citation2017). Claims that blacks lack the motivation to get ahead, for instance, reflect implicit beliefs about shortcomings in black culture (Bobo and Charles Citation2009). This claim of a close intertwining of cultural and internal attributions has never been tested directly, however. The relative handful of attribution studies that explicitly incorporate culture typically conceptualize it as a third, independent dimension, and measure it with a distinctive set of items (Bullock Citation2004; Bullock, Williams, and Limbert Citation2003; Carroll et al. Citation1987; Cassese and Weber Citation2011; Clawson Citation1996; Homan, Valentino, and Weed Citation2017; Smith and Stone Citation1989). These measures include specific cultural elements such as the breakdown of the nuclear family and bad schools (Cassese and Weber Citation2011; Cozzarelli, Wilkinson, and Tagler Citation2001; Shelton Citation2017). There is no consensus about what constitutes a cultural cause, however. For example, “bad schools” has been treated as both a cultural and an external cause (Bobo and Hutchings Citation1996; Unnever Citation2008). One cultural attribution scale (Cozzarelli, Wilkinson, and Tagler Citation2001) includes items that appear either internal (“Being born with a low IQ”) or external (“The types of jobs that the poor can get are often low paying”).

However they are measured, the empirical separation between cultural and internal dimensions is faint at best. The two dimensions are either strongly correlated (Bullock Citation2004; Clawson Citation1996) or tend to load on the same underlying factor (Bullock, Williams, and Limbert Citation2003). Cultural attributions contribute little to policy attitudes when individual attributions are controlled (Applebaum Citation2001; Tagler and Cozzarelli Citation2013). Although the two dimensions are theoretically separable, in practice the white public regards them as two sides of the same coin.

We believe the search for an independent cultural attribution dimension misses how ideas about culture function in public beliefs about racial inequality. First, cultural scales typically refer to specific elements of culture such as single-parent families rather than culture per se. As we will shortly demonstrate, explicit references to African American culture are widespread in popular political rhetoric. Second, public references to black culture often incorporate traditional internal attributions such as poor motivation and antisocial behaviors. Tying internal causes to cultural forces produces a hybrid attribution that is more compelling than internal elements sans culture. Culture augments and embellishes internal attributions, making them more convincing. For instance, it is sometimes asserted that blacks display criminal tendencies because their culture glorifies violence.

Why does a cultural frame round out internal attributions, lending them greater weight? One possibility is that culturally framed internal attributions present a believable blend of individual and environmental causal forces (Lepianka, Van Oorschot, and Gelissen Citation2009; Smith and Stone Citation1989; Tagler and Cozzarelli Citation2013). A substantial proportion of the population does not exclusively endorse internal or external attributions for racial inequality but rather sees a combination as the best explanation for racial disparity (Georgoudi Citation1985; Katz and Hass Citation1988; Kluegel Citation1990). Cultural forces originate outside the person but manifest themselves in individual traits and behaviors. Internal-cultural hybrid attributions therefore appeal to those who reject a strict internal/external dichotomy.

Relatedly, culturally framed internal attributions provide richer, more complete explanations for inequality than internal attributions alone. The cultural overlay functions as a second tier of causation, explaining where internal features such as motivation and behavior originate (Charles Citation2008). Biological attributions for racial inequality have largely disappeared from popular discourse and public opinion (Bobo, Kluegel, and Smith Citation1997; Sniderman and Piazza Citation1993). Culture now provides the dominant explanation for why blacks exhibit attitudes and behaviors that hold them back or get them into trouble.

Bonilla-Silva’s (Citation2017, 46) qualitative examination of “color-blind racism” found that whites pointed to culture as a reason for inequality, especially when funneled through the attitudes and behaviors of individual blacks. When asked whether laziness was responsible for blacks’ status, some respondents agreed, but took pains to link laziness to cultural dynamics. Said one, “Maybe it’s just their background,” while another asserted,

I just think that’s just, you know, they’re raised that way and they see what their parents are like so they assume that’s the way it should be. And they just follow the roles their parents had for them and don’t go anywhere.

Another possible reason for the popularity of cultural attributions is the influence of elite and mass-mediated rhetoric (Zaller Citation1992). Elite communication about racial inequality resounds with references to culture. A close reading of these texts reveals that culture does not compete with internal attributions but rather completes internal forces as comprehensive explanations for inequality.

In March 2014, Wisconsin Congressman Paul Ryan spoke of a “tailspin of culture, in our inner cities in particular, of men not working and just generations of men not even thinking about working or learning the value and the culture of work. There’s a real culture problem here” (Sestanovich Citation2014). When critics attacked Ryan, columnist George Will (Citation2014) wrote in his defense that the challenge is, “to acculturate those un-acquainted with the culture of work to the disciplines and satisfactions of this culture.” Another columnist, David Brooks (Citation2015), asserted that poverty persists because neighborhoods “ … discourage responsibility, future-oriented thinking, and practical ambition. Individuals are left without the norms that middle-class people take for granted.” In the words of FOX TV commentator Bill O’Reilly (NBC News Citation2013),

White people don’t force black people to have babies out of wedlock, but the entertainment industry encourages the irresponsibility by marketing a gangster culture … You want a better situation for blacks? Give them a chance to revive their neighborhoods and culture.

It is not just conservative politicians and pundits who spotlight culture, however. Liberals, academics, and prominent black celebrities and intellectuals have also made such claims (Bonilla-Silva Citation2017; Carroll et al. Citation2017). The “Moynihan Report” (Moynihan Citation1965) warned of the continuing deterioration of the black family as a harbinger of entrenched inequality (Sanneh Citation2015). Many progressives excoriated the Moynihan report for perpetuating negative stereotypes about black women (Bobo and Charles Citation2009; Charles Citation2008), but the sociologist Orlando Patterson has argued that time has proved Moynihan right (Sanneh Citation2015). Patterson (Citation2014) has criticized his fellow sociologists for tip-toeing around cultural explanations for black crime and underachievement. James Carville (Citation1996, 91), the architect of Democrat Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 presidential campaign, wrote, “As some Republicans are very quick and correct to point out, the single biggest social problem we have in America is the breakdown of families.” Similarly, Cornel West (Citation1994, 10–11) wrote, “The collapse of meaning in life – the eclipse of hope and absence of love of self and others, the breakdown of family and neighborhood bonds – leads to the social deracination and cultural denudement of urban dwellers, especially children.”

Culture gets the blame for black criminality as well. Commentators have decried a “culture of violence” or “thug culture” plaguing the inner cities (Robinson Citation1996). Critics single out hip-hop music and culture for glorifying violence:

It’s also their culture. Theirs is the hip-hop culture with the thugs, the jerseys and the hanging medallions. To them, they are living their culture, but only after they find themselves locked in a six-by-eight cell do they think about the consequences of their actions. (Moss Citation2005)

A final potential explanation for the appeal of culturally framed attributions is that they provide a means for blaming the victim for their predicament without incurring the wrath of racially progressive society (Bonilla-Silva Citation2017). By this account, people do not genuinely believe that culturally framed internal attributions are more satisfying than internal attributions alone, but they endorse these explanations because they cloak internal attributions in respectability. Mendelberg (Citation2001) has argued that the social norm against expressing nakedly racist views is so powerful that it has forced racially conservative political elites to make implicit, rather than explicit, racial appeals.

Experiment

We tested our claims about the potency of cultural frames via a survey experiment involving a non-student sample of white Americans. Some participants viewed conventional internal attribution statements and judged their importance as explanations for racial inequality. Other participants judged modified versions of these items that incorporated culture. Participants also expressed their opinions about welfare, affirmative action, and capital punishment.

Our primary empirical prediction follows from the claim that culture enhances internal attributions for racial inequality:

H1: Internal attributions framed by culture will be judged as more important explanations for racial inequality than the same internal attributions absent a cultural frame.

An auxiliary to the first hypothesis predicts that political sophistication will regulate the impact of adding a cultural frame to internal attributions. There are reasons to suspect that the preference for culturally framed internal attributions should be especially pronounced among more sophisticated respondents. Gomez and Wilson (Gomez and Wilson Citation2006a, Citation2006b) argue that individuals differ in their general tendency to make “proximal” (internal) versus “distal” (external) attributions for everything from racial inequality to the state of the economy. Chronic attributional style correlates with political sophistication, such that the less sophisticated favor internal attributions, while the more sophisticated show a preference for relatively complex external attributions. Similarly, Weiner, Osborne, and Rudolph (Citation2011) argue that internal attributions happen automatically, and are only modified after conscious consideration. In other words, only those with the requisite cognitive wherewithal make external attributions. Joslyn and Haider-Markel (Citation2013) found a preference among more educated Democrats for external over internal attributions for two notorious public shootings. To the extent that culturally framed internal attributions are more complex than standard internal attributions, as they include multiple levels of causation, they should appeal especially to the more politically sophisticated.

A separate line of inquiry has considered how sophistication governs the magnitude of framing effects (Chong and Druckman Citation2007; Lecheler and De Vreese Citation2019). Results have been mixed. On one hand, sophistication imbues opinions with strength and clarity, protecting them from the influence of framing. On the other hand, sophistication provides both the acuity to grasp frames and a large body of considerations that the frame invokes. In such a case, framing effects would be stronger among the more sophisticated (Nelson and Oxley Citation1999). We find the latter set of findings more compelling, and thus offer the following hypothesis:

H1A: Political sophistication will moderate the cultural framing effect, such that the more politically sophisticated will respond to the cultural framing manipulation more acutely than the less politically sophisticated.

Finally, we examined how well the two types of internal attributions predict policy attitudes. Generally, those who favor internal attributions tend to oppose policies like welfare and affirmative action that ameliorate inequality (Bobo and Charles Citation2009). They also tend to favor punitive criminal justice measures like capital punishment. We expected that culturally infused measures of internal attributions should better predict policy attitudes than standard internal attributions.

One rationale for this hypothesis lies in the improved validity of the culturally framed attribution measures relative to the conventional internal measures. If, as we claim, culture augments and enhances internal attributions, then measures incorporating culture should better capture such views. More valid measures better predict criterion measures such as policy attitudes (DeVellis and Thorpe Citation2021). Beyond measurement theory, perhaps the average individual who considers culture to be the culprit would oppose policies such as welfare and affirmative action that do nothing to “repair” this culture, and perhaps even perpetuate it (Bonilla-Silva Citation2017). By the same token, lenient criminal justice policies might also be viewed as permitting a criminal culture to persist.

H2: Culturally framed internal attributions will predict policy attitudes more reliably than standard internal attributions.

Materials and methods

We conducted an online survey-based experiment to examine the consequences of framing internal attributions in cultural terms. We recruited a nonstudent sample of US whites for the study. The survey asked participants about their attributions for inequality between blacks and whites with respect to standards of living and involvement in the criminal justice system. A random half of the sample responded to both the external and internal scales of a questionnaire. The other half received the same external scale, but also answered a culturally framed internal scale, rather than the conventional internal scale.

Sample

Qualtrics Panels supplied a sample of 497 white, non-Hispanic adults. Qualtrics Panels used quota sampling on demographic variables such as gender to approximate a nationally representative sample. Our exclusive focus on whites was purely practical; we did not anticipate obtaining enough black respondents to make meaningful comparisons between experimental conditions. Respondents received a small incentive for their participation. The data were collected two times: July 2017 (N = 103), and November 2018 (N = 394). While the core of the experiment remained the same in the two surveys, we added questions such as an educational attainment scale to the second survey. Several respondents dropped out of the study before reaching the attribution measures, leaving an effective sample size of 448 for the income experiment and 450 for the crime experiment. presents a comparison of the distribution of demographic and political variables in the Qualtrics sample to the distribution of comparable variables in the 2016 American National Election Study. We found no remarkable discrepancies.

Table 1. Comparison between selected qualtrics sample characteristics and the 2016 American National Election Survey Sample (non-hispanic whites only).

Attribution measures

Each participant answered questions assessing their attributions for racial inequality in two domains: jobs, housing, and income (hereafter referred to as income); and involvement in the criminal justice system (hereafter referred to as crime). The income questions consisted of two scales: a four-item internal scale, and a three-item external scale. The crime questions consisted of three internal items and three external items (see for the external items). These scales were drawn from previous studies (e.g., Peffley, Hurwitz, and Mondak Citation2017), with a few of our own creations. Two culturally framed internal scales were prepared; one each for the income questionnaire and the crime questionnaire. We created these items by re-writing the internal items to add a prominent place for culture. Participants indicated how important each item was as an explanation for inequality between whites and blacks in that domain by marking a six-point rating scale (“not important at all – extremely important”). Our experiment therefore amounted to a series of question-wording manipulations. The wording of the internal attribution questions (internal versus cultural) constituted the experimental treatment, while the responses to these questions constituted the principal dependent measure. The alternative versions of the internal items appear in .

Table 2. External attribution items.

Table 3. Internal and cultural frames for income and crime questions.

Design

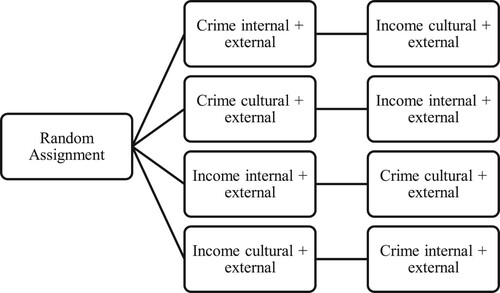

Respondents completed either the income items or the crime items first. The wording of the external attribution scales for income and crime did not vary across experimental conditions. We randomly assigned participants to receive either the standard internal attribution items (hereafter referred to simply as internal) or culturally framed internal attribution questions (hereafter referred to simply as cultural) about the reasons for racial disparities in income. Participants who received the internal items for the income questions received cultural items for the crime questions, and vice-versa. For example, some respondents answered a block of items offering external and internal attributions for black–white differences in income. These respondents also answered external and cultural items for racial disparities in crime. Other respondents answered external and internal items for crime, and external and cultural items for income. Thus, every respondent answered one set of internal items and one set of cultural items, in addition to the external items. The order of the question blocks (income vs. crime) was randomized, as was the order of the items within each block. illustrates the design.

Other measures

The post-treatment questionnaire included a six-item measure of political knowledge that used five items drawn from the Delli Carpini and Keeter (Citation1996) index in addition to a current events question of our own construction. A 101-point feeling thermometer measured affect towards blacks and whites. We calculated a racial animosity score by subtracting the feeling thermometer score for blacks from the feeling thermometer score for whites (Green, Staerklé, and Sears Citation2006). A six-item self-monitoring scale measured concerns about social appearance, thus serving as a proxy for social desirability motivation (Berinsky Citation2004; Huddy and Feldman Citation2009; Snyder and Gangestad Citation1986). We measured opinions about three matters of public policy that directly or indirectly touch on race: affirmative action, capital punishment, and welfare. Finally, we measured a set of demographic and political control variables: education, age, sex, ideology, and partisanship.

Results

Hypothesis 1 predicts that respondents will agree more strongly with cultural attributions than internal attributions. The test consisted of a set of independent samples t-tests that compared the mean response to each internal item with the mean response to the same item bearing a cultural frame. Results appear in .

Table 4. Effects of internal/cultural framing on importance ratings.

shows that all the internal items received higher importance ratings when expressed within a cultural frame. Six out of the seven differences were statistically significant: five returned p values of .005 or less. These results provide strong support for our hypothesis that internal attributions prove more compelling and persuasive when framed by culture.

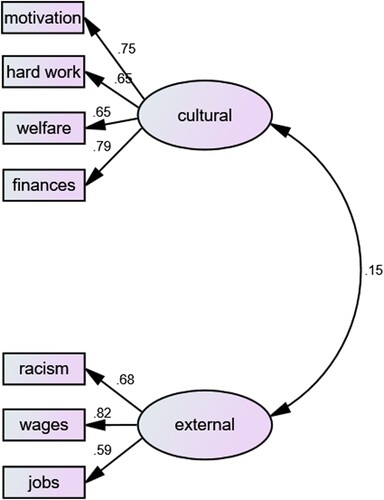

We used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to reassure ourselves on two points: (1) that cultural items hang together as a single factor just as readily as internal items; and (2) that cultural items are distinct from external items. We tested whether two factor models, like that depicted in , improved upon single factor models that dispense with the distinction between internal and external attributions. Indeed, the two-factor models greatly improved upon their single-factor kin: χ2 fit statistics declined by a factor of 8–40 when moving from single factor to two-factor models, with a loss of one degree of freedom. Just like internal items, therefore, cultural items held together as a single factor, and were empirically distinct from external factors.

Figure 2. Confirmatory factor analysis of external and culturally attributions for racial inequality in income (standardized coefficients).

Before combining the internal, cultural, and external items into separate unitary scales, we confronted the possibility of correlated error in our measures (Green and Citrin Citation1994). The structure of the questionnaire – a single block of items with a common response scale – might lend itself to correlated error, possibly due to satisficing (Krosnick, Narayan, and Smith Citation1996). To control for this bias, we tested the same two-factor models but added all possible pairwise error covariances, fixed at .5.Footnote1

shows the results of the model for the cultural and external attributions for income inequality. For simplicity, the figure omits error terms for the observed indicators of the two latent factors, as well as their covariances. Goodness-of-fit indices for all four models appear in . They range from acceptable (internal crime) to good (cultural crime). In general, the models involving cultural and external items fit just as well as models involving internal and external items. The last column of shows the correlations between the two latent factors (internal/cultural and external). While none is significant, three out of the four are nominally positive. This result is perhaps surprising: shouldn’t these correlations be significantly negative? Unnever et al. (Citation2010) refer to this expectation as the “hydraulic relations hypothesis:” the more one endorses internal attributions for inequality, the less one should endorse external attributions, and vice versa. However logical the hydraulic relations hypothesis might seem, the extant data do not support it. Studies that have formally tested the dimensional structure of inequality attributions find null or positive correlations between the dimensions among a substantial proportion of the population (Gomez and Wilson Citation2006a; Kluegel Citation1990; Kluegel and Smith Citation1986).

Table 5. Confirmatory factor analysis model fit statistics and latent factor correlations, two-factor attribution models with fixed error covariances.

Based on the CFA, we created four scales: an internal income scale (the average of the four internal income variables), a cultural income scale, an internal crime scale, and a cultural crime scale. Theta reliability coefficients for the four-item income scale and the three-item crime scale were good regardless of framing (income/internal = .915; income/cultural = .906; crime/internal = .882; crime/cultural = .864). As shows, the difference between the combined internal and combined cultural measures in both domains was highly significant. This finding lends further confirmation to Hypothesis 1 and shows that the enhanced appeal of the cultural frame generalizes to multiple items across two domains of racial inequality.

Political knowledge

To test Hypothesis 1A that the cultural framing effect would be magnified for more sophisticated respondents, we conducted analyses of variance (ANOVAs) on the income and crime attributional scales, using internal attribution frame (internal versus cultural) as a between-participants treatment factor, and political knowledge (low versus high) as a nonmanipulated blocking factor. We created the latter by splitting the knowledge variable at its median.

Hypothesis 1A received strong support from the income experiment. The ANOVA returned a main effect for the framing manipulation (F1,400 = 11.34, p = .001), which simply replicates the earlier t-tests showing that respondents favored cultural attributions over internal attributions. A main effect for political knowledge (F1,400 = 36.30, p < .001) was qualified by the predicted two-way interaction (F1,400 = 9.72, p = .002). Among the less knowledgeable, support for both cultural (M = 4.06, SD = 1.45) and internal attributions (M = 4.02, SD = 1.46) was relatively high. Among the more knowledgeable, however, support for cultural attributions (M = 3.63, SD = 1.46) substantially exceeded support for internal attributions (M = 2.68, SD = 1.51). The cultural framing effect was therefore confined to the more knowledgeable for the income experiment.

The results for the crime experiment did not support Hypothesis 1A. Main effects for framing (F1,400 = 19.37, p < .001) and knowledge emerged (F1,400 = 35.45, p < .001). The former effect simply replicates the earlier finding of a preference for cultural over internal items; the latter effect reveals that low knowledge respondents favored both internal and cultural attributions more than high knowledge respondents. The crucial two-way interaction was not significant. The preference for cultural over internal items was of about the same magnitude for low knowledge (Mcultural = 4.39, SD = 1.37; Minternal = 3.77, SD = 1.63) and high knowledge (Mcultural = 3.55, SD = 1.35; Minternal = 2.91, SD = 1.35) participants.

Policy attitudes

To test Hypothesis 2 – that cultural attributions predict policy attitudes better than internal attributions – we conducted OLS regressions for welfare, affirmative action, and capital punishment attitudes. We estimated each model three times: once using the internal attribution variable; a second time using the cultural attribution variable; and a third time including an interaction term to see whether the effect of cultural attributions was significantly stronger than the effect of internal attributions. We used attributions for income disparities to predict welfare and affirmative action support, and attributions for crime disparities to predict capital punishment support. The models included controls age, gender, education, self-monitoring, ideology, partisanship, political knowledge, racial animosity, and external attributions. The results appear in .

Table 6. Modeling welfare, affirmative action, and capital punishment attitudes.

Internal and cultural attributions were both associated with support for cuts in welfare spending, opposition to affirmative action, and support for capital punishment. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, coefficients for the cultural variables were stronger than for the internal variables in all three cases. The interaction term was not significant for affirmative action attitudes, but significant for welfare and capital punishment attitudes (p’s < .05, one-tailed test). Overall, the results show that cultural attributions predict policy attitudes better than internal attributions.

One finding we did not predict that emerged from the analysis of policy attitudes was that support for capital punishment was stronger in the internal condition (M = 2.85, SD = 1.21) than in the cultural condition (M = 2.58, SD = 1.33; t = 2.26, p = .024). Perhaps cultural crime items “softened” views about punishment. Seeing internal crime items in a cultural context might have removed some of the retributional motivation that energizes support for capital punishment (Ellsworth and Gross Citation1994) or challenged the sense that murderers have sole moral culpability for their crimes. There was no framing effect on welfare or affirmative action attitudes.

Discussion

The results provided rich evidence that culture enhances internal attributions for racial inequality, making them resonate better with public opinion about race. Respondents judged culturally framed internal attributions as superior explanations for racial inequality than the same internal attributions without the cultural frame. This effect was observed across multiple measures for two key areas of racial inequality: living standards and engagement with the criminal justice system. In general, the effect was substantively impressive: about .5 points on a 1–6 scale. The special appeal of cultural framing was apparent among more sophisticated respondents in the standard of living domain, and among all respondents in the crime domain. Finally, compared to conventional measures of internal attributions for racial disparities, culture-infused internal attributions predicted policy attitudes better.

Why does adding a cultural frame to internal attributions make them more compelling? One possibility is that cultural attributions are less exclusively internal than standard internal attributions. Culture injects a bit of extra-individual causality to internal attributions, perhaps making them more appealing to the substantial proportion of the American public who at least partly endorses both the internal and external dimensions of causation (Unnever et al. Citation2010). Furthermore, a nod to culture demystifies why blacks think and act in ways that put them at a disadvantage, in the eyes of the public. Culture supplies a cause behind internal causes, explaining whence they originate. Since biological causes for racial differences have been roundly discredited, culture stands as the ultimate source for proximal internal causes (Bobo, Kluegel, and Smith Citation1997).

Another possible reason for the appeal of cultural attributions is elite influence. We documented several instances of mass-mediated claims by political elites, pundits, academics, and others to the effect that deficiencies in African American culture also keep blacks down. The special appeal of culturally framed internal attributions among the public might reflect the top-down influence of such elite-level claims.

Finally, it is possible that the favoritism shown towards culture is a mere façade. Misgivings about social desirability bias have long plagued explicit measures of racial prejudice (Huddy and Feldman Citation2009; Krysan Citation2000). Perhaps cultural attributions garner more support than internal attributions because they are more polite ways to “blame the victim,” i.e., express prejudiced views (Bonilla-Silva Citation2017; Creighton and Wozniak Citation2019). Such an account would call into question the claim that culture enhances internal attributions among many white Americans. Instead, culture would merely provide a means to justify racism.

This account is surely true for some whites. Many explicit measures of contemporary racial attitudes are vulnerable to social desirability bias (Berinsky Citation2004; Krysan Citation2000). We have reasons to doubt that social desirability motivation explains the entirety of the cultural framing effect, however. Self-monitoring was significantly correlated with racial antipathy, but not with internal or cultural attributions. This finding is in keeping with Huddy and Feldman (Citation2009), who argue that, among explicit measures of racial opinions, attribution questions are the least likely to suffer from social desirability bias. At the elite level, it is certainly not the case that making cultural attributions insulates one from the charge of racism (Sestanovich Citation2014). Knowing that they are sure to face rebuke, communicators would presumably hesitate to invoke culture unless they sincerely believed in its contribution to racial inequality.

Still, it would be wise in the future to document more precisely the relative impact of social desirability motivation. “Count techniques” such as the randomized response technique, list experiments, or the crosswise model for questionnaire design (Schnell and Thomas Citation2021) all seek to minimize social desirability concerns for measuring sensitive topics such as racial attitudes. The researcher could implement these within the present experimental design to see if the culture framing effect is attenuated when social desirability pressure has been at least partly slackened. A less technical approach that preserves some of the data lost by count techniques is to vary social desirability concerns by making some data collection modes more intimate (e.g., a face-to-face interview) and some more impersonal (e.g., a mail survey).

A few notable theories of white racial attitudes assign a role to culture in explaining the white public’s attributions for racial inequality. In introducing laissez-faire racism theory, Bobo and colleagues (Bobo, Kluegel, and Smith Citation1997, 20) plainly state, “a large segment of white America attributes black–white inequality to the failings of black culture.” In Pettigrew and Meertens’s (Citation1995, 58) subtle prejudice theory, the prejudiced individual “attributes outgroup disadvantage to cultural differences.” Bonilla-Silva’s (Citation2017) theory of color-blind racism holds that white people cite deficiencies in black culture as a polite way of faulting backs for their own disadvantaged status. Finally, symbolic racism theory (Tarman and Sears Citation2005) and racial resentment theory (Kinder and Sanders Citation1996) argue that many whites believe that blacks have not assimilated the values underlying the Protestant work ethic.

Our focus on cultural attributions for racial inequality clearly owes much to the above research on white racial attitudes. There are important points of difference, however. Nearly all the work includes no direct mention of culture in their measures of racial attitudes. Symbolic racism and racial resentment measures, for example, faithfully replicate the internal/external attributional structure with no mention of culture per se (Kam and Burge Citation2018; Tarman and Sears Citation2005). Laissez-faire racism theory assumes that internal attributions or negative racial stereotypes provide prima facie evidence of perceived cultural inferiority. Work that does include direct measures of cultural attributions treats the cultural dimension as separate from internal attributions.

We argue instead that internal attributions do not necessarily reflect perceived cultural inferiority, but that adding a cultural element augments internal attributions, making them more satisfying explanations for racial inequality among much of the white population. Our evidence is experimental, rather than correlational, affording us greater confidence in our claims about the special appeal of cultural attributions. Much of the literature on cultural attributions assumes that culture precedes or underlies internal attributions. While our experimental evidence is consistent with this claim, there remains the possibility of feedback loops whereby internal and cultural attributions mutually reinforce. Finally, whereas nearly all the extant research examines attributions for inequality in standards of living, we extend the cultural analysis to the domain of inequality in involvement with the criminal justice system.

Our investigation studied the views of white Americans exclusively. This was a pragmatic decision based on the expected sample size. We will next test whether the results of our experiment replicate among a black sample. We know already that blacks are significantly less likely than whites to endorse internal attributions for racial inequality (Bobo and Charles Citation2009). Still, internal attributions for black–white inequality are not unheard of among blacks, nor are misgivings about certain aspects of African American culture (Pew Research Center Citation2007). It will be valuable to find out if cultural framing likewise enhances the appeal of internal attributions among this population.

Naturally, not everyone agrees that substantial racial inequalities persist in contemporary America, especially in material well-being. Only 47% of whites expressing a belief on the subject say that blacks are worse-off financially than whites. Blacks are certainly more likely to endorse that statement, but a hefty 38% assert that they are about as well off, or even better off, than whites (Pew Research Center Citation2016). By contrast, whites readily acknowledge the connection between race and crime (Hurwitz and Peffley Citation1997; Pickett et al. Citation2012). Future studies will measure participants’ beliefs about both the extent and causes of racial inequality.

Support for our hypotheses was not uniform. Hypothesis 1 was supported for seven out of eight comparisons. The lone exception was the “law and order” item in the crime experiment. Hypothesis 1A was supported for the income experiment but not for the crime experiment. Hypothesis 2 was supported for welfare and capital punishment, but not for affirmative action. We believe the preponderance of evidence makes a strong case for the special appeal of culturally framed attributions, but the exceptions want explanation. Naturally, any such account is mere post hoc speculation.

With respect to Hypothesis 1A, we found that support for cultural crime items was stronger than support for internal items among both the more and less knowledgeable. A careful reading of the internal crime items suggests a possible reason. The two items that showed a clear internal-cultural difference are explicitly behavioral in their internal forms (“Black people are more violent and aggressive”; “Black people commit more crime than white people”). Perhaps plain behavioral items like these especially beg the more complete explanation that culture provides. As mentioned above, the “law and order” attribution item did not vary by framing condition, perhaps because it was less explicitly behavioral.

Cultural items predicted affirmative action attitudes better than standard internal items, as predicted, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. What explains the relative weakness of this effect? One thing that stands out in the analysis of affirmative action attitudes is the powerful impact of external attributions. The unstandardized coefficients relating external attributions to affirmative action are about double those relating external attributions to welfare and capital punishment attitudes. Affirmative action is often promoted as a remedy for structural inequalities that deny blacks opportunities in employment and education. It should perhaps come as no surprise that external attributions therefore overshadow internal attributions in predicting affirmative action attitudes, and that cultural framing only somewhat enhances their power. Nelson and Kinder (Citation1996) found that “group centric” frames for affirmative action, such as the portrayal of affirmative action as an undeserved advantage for blacks (rather than reverse discrimination against whites) enhanced the impact of antiblack attitudes on affirmative action attitudes. Our relatively unadorned question about affirmative action perhaps did not foreground internal attributions.

Conclusion

Academics scorned explanations for poverty and inequality rooted in culture following the furor over the Moynihan Report (Cohen Citation2010; Moynihan Citation1965). Others stepped into the void and talked openly about culture. Fresh from his triumph in the 1994 midterm elections, Georgia Congressman Newt Gingrich attacked Great Society programs for fostering a degenerate culture: “They are a disaster. They ruined the poor. They created a culture of poverty and a culture of violence which is destructive of this civilization … ” (Bishop Citation1994).

Some scholars are again investigating culture’s actual, not perceived, impact on inequality (Anderson Citation2000; Charles Citation2008; Patterson and Fosse Citation2015; Stewart and Simons Citation2010; Wilson Citation1987, Citation2010). They argue that the distinct culture of the black underclass represents a functional adaptation to the group’s persistent disadvantage. Under this conception, culture occupies a meso layer of causation between the proximate layer of individual attitudes and behaviors and the ultimate layer of socio-economic structure and entrenched racism. Future work will explore the relative pull of such complex views about inequality among ordinary citizens.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the help of Michele Acker, William Minozzi, Michael Neblo, Kira Sanbonmatsu, and members of the political psychology workshop in the Department of Political Science, Ohio State University.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Another approach to controlling for correlated error is to include a common method factor, uncorrelated with the two substantive factors (Nelson Citation1999). We tried this, but the analysis did not yield plausible solutions.

References

- Anderson, Elijah. 2000. Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City. New York: WW Norton.

- Applebaum, Lauren D. 2001. “The Influence of Perceived Deservingness on Policy Decisions Regarding Aid to the Poor.” Political Psychology 22 (3): 419–442.

- Bennett, Robert M., Lisa Raiz, and Tamara S. Davis. 2016. “Development and Validation of the Poverty Attributions Survey.” Journal of Social Work Education 52 (3): 347–359.

- Berinsky, Adam J. 2004. “Can We Talk? Self-Presentation and the Survey Response.” Political Psychology 25 (4): 643–659.

- Biden, Joe. 2021. “Remarks by President Biden Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre.” The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/06/02/remarks-by-president-biden-commemorating-the-100th-anniversary-of-the-tulsa-race-massacre/. June 2, 2021.

- Bishop, Bill. 1994. “Blame Game and the Culture of Poverty.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. December 28.

- Bobo, Lawrence, and Camille Charles. 2009. “Race in the American Mind: From the Moynihan Report to the Obama Candidacy.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 621 (1): 243–259.

- Bobo, Lawrence, and Vincent L. Hutchings. 1996. “Perceptions of Racial Group Competition: Extending Blumer’s Theory of Group Position to a Multiracial Social Context.” American Sociological Review 61 (6): 951–972.

- Bobo, Lawrence, and James R. Kluegel. 1993. “Opposition to Race-targeting: Self-Interest, Stratification Ideology, or Racial Attitudes?” American Sociological Review 58 (4): 443.

- Bobo, Lawrence, James R. Kluegel, and Ryan A. Smith. 1997. “Laissez-Faire Racism: The Crystallization of a Kinder, Gentler, Antiblack Ideology.” Racial Attitudes in the 1990s: Continuity and Change 15: 23–25.

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2017. Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America. 5th ed. Latham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Brooks, David. 2015. New York Times. “The Nature of Poverty.” https://search.proquest.com/docview/1712365542.

- Bullock, Heather E. 2004. “From the Front Lines of Welfare Reform: An Analysis of Social Worker and Welfare Recipient Attitudes.” The Journal of Social Psychology 144 (6): 571–590.

- Bullock, Heather E., Wendy R. Williams, and Wendy M. Limbert. 2003. “Predicting Support for Welfare Policies: The Impact of Attributions and Beliefs About Inequality.” Journal of Poverty 7 (3): 35–56.

- Carroll, Joseph, John A. Johnson, Catherine Salmon, Jens Kjeldgaard-Christiansen, Mathias Clasen, and Emelie Jonsson. 2017. “A Cross-Disciplinary Survey of Beliefs About Human Nature, Culture, and Science.” Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture 1 (1): 1–32.

- Carroll, John S., William T. Perkowitz, Arthur J. Lurigio, and Frances M. Weaver. 1987. “Sentencing Goals, Causal Attributions, Ideology, and Personality.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52 (1): 107–118.

- Carville, James. 1996. We’re Right, They’re Wrong: A Handbook for Spirited Progressives. New York: Random House: Simon & Schuster.

- Cassese, Erin, and Christopher Weber. 2011. “Emotion, Attribution, and Attitudes Toward Crime.” Journal of Integrated Social Sciences 2 (1): 63–97.

- Charles, Maria. 2008. “Culture and Inequality: Identity, Ideology, and Difference in ‘Postascriptive Society’.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 619 (1): 41–58.

- Chong, Dennis, and James N. Druckman. 2007. “Framing Theory.” Annual Review of Political Science 10 (1): 103–126.

- Clawson, Rosalee A. 1996. “Social Groups and Socio-Cultural Explanations in American Public Opinion.” PhD Thesis. http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=osu1487935573773662.

- Cohen, Patricia. 2010. International Herald Tribune. “Why Are the Poor Poor, and Whose Fault Is It? The ‘Culture of Poverty,’ a Theory from the ‘60s, Is Reconsidered in U.S.”.

- Cozzarelli, Catherine, Anna V. Wilkinson, and Michael J. Tagler. 2001. “Attitudes Toward the Poor and Attributions for Poverty.” Journal of Social Issues 57 (2): 207–227.

- Creighton, Mathew J., and Kevin H. Wozniak. 2019. “Are Racial and Educational Inequities in Mass Incarceration Perceived to Be a Social Problem? Results from an Experiment.” Social Problems 66 (4): 485–502.

- Delli Carpini, Michael X, and Scott Keeter. 1996. What Americans Know About Politics and Why It Matters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- DeVellis, Robert F., and Carolyn T. Thorpe. 2021. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. 5. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Drakulich, Kevin M. 2015. “Explicit and Hidden Racial Bias in the Framing of Social Problems.” Social Problems 62 (3): 391–418.

- Ellsworth, Phoebe C., and Samuel R. Gross. 1994. “Hardening of the Attitudes: Americans’ Views on the Death Penalty.” Journal of Social Issues 50 (2): 19–52.

- Georgoudi, Marianthi. 1985. “Dialectics in Attribution Research: A Reevaluation of the Dispositional-Situational Causal Dichotomy.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49 (6): 1678–1691.

- Gilens, Martin. 1995. “Racial Attitudes and Opposition to Welfare.” The Journal of Politics 57 (4): 994–1014.

- Gomez, Brad T., and J. Matthew Wilson. 2006a. “Cognitive Heterogeneity and Economic Voting: A Comparative Analysis of Four Democratic Electorates.” American Journal of Political Science 50 (1): 127–145.

- Gomez, Brad T., and J. Matthew Wilson. 2006b. “Rethinking Symbolic Racism: Evidence of Attribution Bias.” The Journal of Politics 68 (3): 611–625.

- Green, Donald Philip, and Jack Citrin. 1994. “Measurement Error and the Structure of Attitudes: Are Positive and Negative Judgments Opposites?” American Journal of Political Science 38 (1): 256–281.

- Green, Eva G. T., Christian Staerklé, and David O. Sears. 2006. “Symbolic Racism and Whites’ Attitudes Towards Punitive and Preventive Crime Policies.” Law and Human Behavior 30 (4): 435–454.

- Hawkins, Darnell F. 1981. “Causal Attribution and Punishment for Crime.” Deviant Behavior 2 (3): 207–230.

- Homan, Patricia, Lauren Valentino, and Emi Weed. 2017. “Being and Becoming Poor: How Cultural Schemas Shape Beliefs About Poverty.” Social Forces 95 (3): 1023–1048.

- Hopkins, Daniel J. 2009. “Partisan Reinforcement and the Poor: The Impact of Context on Explanations for Poverty.” Social Science Quarterly 90 (3): 744–764.

- Huddy, Leonie, and Stanley Feldman. 2009. “On Assessing the Political Effects of Racial Prejudice.” Annual Review of Political Science 12: 423–447.

- Hughes, Michael, and Steven A. Tuch. 2000. “How Beliefs About Poverty Influence Racial Policy Attitudes: A Study of Whites, African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians in the United States.” In Racialized Politics: The Debate About Racism in America, edited by David O. Sears, Jim Sidanius, and Lawrence Bobo, 165–190. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Hunt, Matthew O. 2007. “African American, Hispanic, and White Beliefs About Black/White Inequality, 1977-2004.” American Sociological Review 72 (3): 390–415.

- Hurwitz, Jon, and Mark Peffley. 1997. “Public Perceptions of Race and Crime: The Role of Racial Stereotypes.” American Journal of Political Science 41 (2): 375–401.

- Johnson, Devon. 2007. “Crime Salience, Perceived Racial Bias, and Blacks’ Punitive Attitudes.” Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice 4 (4): 1–18.

- Johnson, Devon. 2008. “Racial Prejudice, Perceived Injustice, and the Black-White Gap in Punitive Attitudes.” Journal of Criminal Justice 36 (2): 198–206.

- Joslyn, Mark R., and Donald P. Haider-Markel. 2013. “The Politics of Causes: Mass Shootings and the Cases of the Virginia Tech and Tucson Tragedies: The Politics of Causes.” Social Science Quarterly 94 (2): 410–423.

- Kam, Cindy D., and Camille D. Burge. 2018. “Uncovering Reactions to the Racial Resentment Scale Across the Racial Divide.” The Journal of Politics 80 (1): 314–320.

- Katz, Irwin, and R. Glen Hass. 1988. “Racial Ambivalence and American Value Conflict: Correlational and Priming Studies of Dual Cognitive Structures.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55 (6): 893.

- Kinder, Donald R., and Lynn M. Sanders. 1996. Divided by Color: Racial Politics and Democratic Ideals. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Kluegel, James R. 1990. “Trends in Whites’ Explanations of the Black-White Gap in Socioeconomic Status, 1977-1989.” American Sociological Review 55: 512–525.

- Kluegel, James R., and Lawrence Bobo. 1993. “Dimensions of Whites’ Beliefs About the Black-White Socioeconomic Gap.” In Prejudice, Politics, and the American Dilemma, edited by Paul M. Sniderman, Philip E. Tetlock, and Edward G. Carmines, 127–147. Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ. Press.

- Kluegel, James R., and Eliot R. Smith. 1986. Beliefs About Inequality: Americans’ Views of What Is and What Ought to Be. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Knight, Kathleen. 1998. “In Their Own Words: Citizens’ Explanations of Inequality Between the Races.” In Perception and Prejudice: Race and Politics in the United States, edited by Jon Hurwitz and Mark Peffley, 202–232. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Krosnick, Jon A., Sowmya Narayan, and Wendy R. Smith. 1996. “Satisficing in Surveys: Initial Evidence.” New Directions for Evaluation 1996 (70): 29–44.

- Krysan, M. 2000. “Prejudice, Politics, and Public Opinion: Understanding the Sources of Racial Policy Attitudes.” Annual Review of Sociology 26: 135–168.

- Lecheler, Sophie, and Claes H. De Vreese. 2019. News Framing Effects: Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Lepianka, Dorota, Wim Van Oorschot, and John Gelissen. 2009. “Popular Explanations of Poverty: A Critical Discussion of Empirical Research.” Journal of Social Policy 38 (3): 421–438.

- Mendelberg, Tali. 2001. The Race Card: Campaign Strategy, Implicit Messages, and the Norm of Equality. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Mijs, Jonathan J. B. 2018. “Inequality Is a Problem of Inference: How People Solve the Social Puzzle of Unequal Outcomes.” Societies 8 (3): 64–80.

- Moss, Khalid. 2005. Dayton Daily News. “Think Tank Targets Violence”.

- Moynihan, Daniel Patrick. 1965. The Negro Family: The Case for National Action. Washington, DC: Office of Policy Planning and Research, U.S. Department of Labor.

- Mullinix, Kevin J., and Robert J. Norris. 2018. “Pulled-Over Rates, Causal Attributions, and Trust in Police.” Political Research Quarterly 72 (2): 420–434.

- NBC News. 2013. Fox’s Bill O’Reilly Loses It When Talking about Race. http://www.nbcnews.com/video/all-in-/52559880.

- Nelson, Thomas E. 1999. “Group Affect and Attribution in Social Policy Opinion.” The Journal of Politics 61 (2): 331–362.

- Nelson, Thomas E., and Donald R. Kinder. 1996. “Issue Frames and Group-Centrism in American Public Opinion.” The Journal of Politics 58 (4): 1055–1078.

- Nelson, Thomas E., and Zoe M. Oxley. 1999. “Issue Framing Effects on Belief Importance and Opinion.” The Journal of Politics 61 (4): 1040–1067.

- Patterson, Orlando. 2014. “How Sociologists Made Themselves Irrelevant.” The Chronicle of Higher Education 61 (14): B4.

- Patterson, Orlando. 2015. “The Real Problem With America's Inner Cities.” New York Times. May 9.

- Patterson, Orlando, and Ethan Fosse. 2015. The Cultural Matrix: Understanding Black Youth. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Peffley, Mark, and Jon Hurwitz. 2002. “The Racial Components of ‘Race-Neutral’ Crime Policy Attitudes.” Political Psychology 23 (1): 59–75.

- Peffley, Mark, and Jon Hurwitz. 2007. “Persuasion and Resistance: Race and the Death Penalty in America.” American Journal of Political Science 51 (4): 996–1012.

- Peffley, Mark, Jon Hurwitz, and Jeffery Mondak. 2017. “Racial Attributions in the Justice System and Support for Punitive Crime Policies.” American Politics Research 45 (6): 1032–1058.

- Pettigrew, T. F., and R. W. Meertens. 1995. “Subtle and Blatant Prejudice in Western Europe.” European Journal of Social Psychology 25 (1): 57–75.

- Pew Research Center. 2007. Optimism about Black Progress Declines: Blacks See Growing Values Gap Between Poor and Middle Class. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2007/11/13/blacks-see-growing-values-gap-between-poor-and-middle-class/.

- Pew Research Center. 2016. On Views of Race and Inequality, Blacks and Whites Are Worlds Apart. ProQuest. https://search.proquest.com/docview/2256979582.

- Pickett, Justin T., Ted Chiricos, Kristin M. Golden, and Marc Gertz. 2012. “Reconsidering the Relationship Between Perceived Neighborhood Racial Composition and Whites’ Perceptions of Victimization Risk: Do Racial Stereotypes Matter?” Criminology; An interdisciplinary Journal 50 (1): 145–186.

- Pickett, Justin T., and Stephanie Bontrager Ryon. 2017. “Race, Criminal Injustice Frames, and the Legitimation of Carceral Inequality as a Social Problem.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 14 (02): 577–602.

- Robinson, Frederick D. 1996. “The Atlanta Journal and Constitution.” I’ll Weep for Shakur: Another Victim of the Culture of Black Deviancy. https://search.proquest.com/docview/293161063.

- Sahar, Gail. 2014. “On the Importance of Attribution Theory in Political Psychology.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 8 (5): 229–249.

- Sanneh, Kelefa. 2015. “Don’t Be Like That.” New Yorker 90 (47): 62–68.

- Schnell, Rainer, and Kathrin Thomas. 2021. “A Meta-Analysis of Studies on the Performance of the Crosswise Model.” Sociological Methods & Research 1–26.

- Sestanovich, Clare. 2014. “Black Culture and Progressivism.” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/04/black-culture-and-progressivism/360362/, April 22, 2021.

- Shelton, Jason E. 2017. “A Dream Deferred?: Privileged Blacks’ and Whites’ Beliefs About Racial Inequality.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 14 (1): 73–91.

- Smith, Kevin B., and Lorene H. Stone. 1989. “Rags, Riches, and Bootstraps: Beliefs About the Causes of Wealth and Poverty.” The Sociological Quarterly 30 (1): 93–107.

- Sniderman, Paul M., and Michael Gray Hagen. 1985. Race and Inequality. Chatham, NJ: Chatham House Publishers.

- Sniderman, Paul M., and Thomas Leonard Piazza. 1993. The Scar of Race. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Snyder, Mark, and Steve Gangestad. 1986. “On the Nature of Self-Monitoring: Matters of Assessment, Matters of Validity..” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51 (1): 125–139.

- Stewart, Eric A., and Ronald L. Simons. 2010. “Race, Code of the Street, and Violent Delinquency: A Multilevel Investigation of Neighborhood Street Culture and Individual Norms of Violence.” Criminology; An interdisciplinary Journal 48 (2): 569–605.

- Tagler, Michael J., and Catherine Cozzarelli. 2013. “Feelings Toward the Poor and Beliefs About the Causes of Poverty: The Role of Affective-Cognitive Consistency in Help-Giving.” The Journal of Psychology 147 (6): 517–539.

- Tarman, Christopher, and David O. Sears. 2005. “The Conceptualization and Measurement of Symbolic Racism.” The Journal of Politics 67 (3): 731–761.

- Tuch, Steven A., and Michael Hughes. 1996. “Whites’ Racial Policy Attitudes.” Social Science Quarterly 77 (4): 723–745.

- Unnever, James D. 2008. “Two Worlds Far Apart: Black-White Differences in Beliefs About Why African-American Mean Are Disproportionately Imprisoned.” Criminology; An interdisciplinary Journal 46 (2): 511–538.

- Unnever, James D., John K. Cochran, Francis T. Cullen, and Brandon K. Applegate. 2010. “The Pragmatic American: Attributions of Crime and the Hydraulic Relation Hypothesis.” Justice Quarterly 27 (3): 431–457.

- Walton, Hanes, Robert C. Smith, and Sherri L. Wallace. 2020. American Politics and the African American Quest for Universal Freedom. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Weiner, Bernard, Danny Osborne, and Udo Rudolph. 2011. “An Attributional Analysis of Reactions to Poverty: The Political Ideology of the Giver and the Perceived Morality of the Receiver.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 15 (2): 199–213.

- West, Cornel. 1994. Race Matters. New York: Vintage Books.

- Wheelock, Darren, Pamela Wald, and Yakov Shchukin. 2012. “Managing the Socially Marginalized: Attitudes Toward Welfare, Punishment, and Race.” Journal of Poverty 16 (1): 1–26.

- Will, George. 2014. “A Half Century in Denial About Poverty.” The Denver Post.

- Wilson, William J. 1987. The Truly Disadvantaged. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press.

- Wilson, William J. 2010. More Than Just Race. New York: Norton.

- Zaller, John. 1992. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press.