ABSTRACT

Based on the classic models developed by Spady and Tinto on the link between social and academic integration and dropout, we propose a refined model to explain dropout intentions – relating to dropout from higher education (HE) and dropout from a specific study programme – that more strongly emphasises individual background characteristics (e.g. gender, social origin, and immigration background). Additionally, we consider students’ satisfaction with the institutional support structures. Using Eurostudent survey data, this conceptual model was tested using structural equation modelling in the international and diverse HE context of Luxembourg. While the fitted model confirmed most of the expected associations of the conventional Spady–Tinto approach, initial study commitment was not linked to social integration (contacts with fellow students). We were able to identify satisfaction with institutional support as a key factor in explaining dropout intention, thus contributing to existing knowledge. In addition, we found that the link between socioeconomic factors and dropout intention from a study programme is not entirely mediated by the Spady–Tinto factors of commitment and integration.

Introduction

Dropout from higher education (HE) study programmes remains one of major issues within global HE systems, particularly vis-à-vis educational policies in many parts of the world seeking to increase the number of university graduates. Defining dropout in terms of students leaving their study programme or the entire HE system, while conceptualising dropout rates as the opposite of completion rates, a meta-analysis prepared by the Center for Higher Education Policy Studies (University of Twente) and the Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education reveals differences in HE completion between different countries. It indicates a serious problem for some (e.g. France) in reaching the target of undisturbed, linear and smooth studies, and HE graduation rates (European Commission Citation2015, 33–34). Recent data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD Citation2019, 225) found that in many regions (e.g. Brazil, Slovenia, Chile, the French-speaking part of Belgium) almost half of the students did not finish any tertiary programme, and very likely dropped out of the entire HE system. While completion rates, rather than dropout rates, are the focus of comparative policy studies, specific data on dropout are scarce (European Commission Citation2015). The last OECD call for the explicit consideration of dropout from HE (OECD Citation2010, 22) indicated dropout rates (the proportion of students who enter tertiary education without graduating) of between more than 50 percent (US) and about 10 percent (Japan), with an OECD average of slightly above 30 percent.

In theory-oriented sociology of education, the influential Spady–Tinto models of student dropout (Spady Citation1971; Tinto Citation1975, Citation1993) serve as useful concepts in the explanation of HE dropout. These models specifically focus on the academic and social integration of students, and presume that these are linked to a certain commitment towards students’ academic and social environment in educational institutions, as well as being associated with university dropout as a negative outcome. This theoretical framework has been applied by many scholars and – in its classic or extended versions – proven to still be an adequate tool in the explanation of dropout (e.g. Berger and Braxton Citation1998; Mannan Citation2007; Nicoletti Citation2019). However, both theory and empirical studies lacked a clear differentiation between dropout from a study programme and/or total dropout from HE so far. Distinguishing between the two occasions entails meaningful consequences both for theorising on student dropout, and policies to capture and counteract student dropout, taking into account its more fine-grained understanding.

While major attention in dropout research has been devoted to integration and commitment (e.g. Mannan Citation2007; Piepenburg and Beckmann Citation2021), studies have neglected institutions’ support with regard to their roles in students’ dropout intentions (e.g. Rumberger et al. Citation1990; Brown and Mazzarol Citation2009; Yair, Rotem, and Shustak Citation2020). Given that many dropout studies are based on administrative and/or single-institution data sources, different types of dropout such as leaving the entire HE system, a HE institution or a specific study programme are often not adequately distinguished (for exceptions, see Belloc, Maruotti, and Petrella Citation2010; Meggiolaro, Giraldo, and Clerici Citation2017; Rodríguez-Gómez et al. Citation2016).

Furthermore, academic and social integration are widely considered constructs, but vis-à-vis a diversifying student population, differential integration levels for different groups of students need to be taken into account. In the nexus of HE expansion and a European HE policy strategy that explicitly fosters student mobility, today’s student populations are diverse with regard to many characteristics, particularly in relation to students’ geographic origin, migration background, or nationality. Thus, in adding to the current state of research, we consider the dropout intentions of three different groups, namely international and native students, and those with an immigrant background.

The aim of this study is twofold. First, we conceptualise dropout either from a study programme or from HE, taking into account individual and institutional characteristics. This enables us to enrich the existing Spady–Tinto models and highlight factors that are associated with dropout. In this respect, our main research questions in relation to the conceptual considerations are how individual characteristics (social origin, gender, immigrant backgrounds) link to dropout intention via aspects of commitment and integration, and what role institutional support plays in this.

Second, we apply the established dropout model to the young and international HE context in Luxembourg. Little is known about the mechanisms of HE dropout in Luxembourg, and even the dropout rates can barely be estimated, as dropout is not systematically monitored. The latest published key performance indicators of the University of Luxembourg, including completion rates (as an indicator that is complementary to dropout in some way), relate to the academic year 2013, disclosing completion rates of 46.6 percent (bachelor’s programmes 180 ECTS, European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System) and 69.7 percent (bachelor’s programmes 240 ECTS) at the bachelor’s level, and 81.5 percent at the master’s level (University of Luxembourg Citation2013) for the study entry cohort 2008/2009. While Luxembourg took part in the international Eurostudent VII survey for the first time, the related data set (gathered in 2019) provides an initial and unique insight into the mechanisms behind dropout and dropout intention in this specific setting. The Eurostudent data also allow for distinguishing between two types of dropout intentions: dropping out from the entire HE system and dropping out from a study programme.

The innovative potential of revisiting the Spady–Tinto approach with regard to Luxembourg relates to its nationally and culturally diverse HE system, which reflects a case where the effects of the internationalisation of HE can be observed in a magnified way. First, the student population is highly heterogeneous due to a large number of international students – about 50 percent (2019) – and students who received their university entrance certificate in Luxembourg, but have an immigrant background (more than 20 percent). This interesting HE context enables us to investigate the relationship between immigrant background and dropout intention, given the common assumption that immigrant students’ minority status hampers them in developing a sense of belonging within the HE environment as compared to majority group students (Hurtado and Carter Citation1997). By contrast, international students’ persistence has either been framed in the light of integration obstacles or, conversely, as a product of being highly motivated, and determined to succeed within the host HE context. Second, the University of Luxembourg as a key HE institution is young (it was founded in 2003). It was launched taking into account different international HE systems, and follows an international, interdisciplinary, and multilingual research university approach (Harmsen and Powell Citation2018).

Dropout from HE: conceptual framework

The Spady–Tinto approach

At the beginning of the 1970s, both Spady and Tinto worked on dropout from HE, summarising the state of research and synthesising the findings to develop explanatory models. While Spady and Tinto did not develop a joint model, Tinto (Citation1975) based his own theorising on a previous model by Spady (Citation1970) that he had reviewed. Thus, we will speak of the Spady–Tinto approach. Their distinct feature is the focus on sociological aspects of dropout: they emphasise both (socioeconomic) individual factors and factors relating to the HE institutions.

The conceptual starting point of both models is the classic sociological work of Durkheim (Citation[1897] 2010) on social integration. Applying Durkheim’s assumption that the main driver of suicide is a lack of integration into society, manifested in a deficit of social ties and a lack of congruence between one’s own norms and values and those of the collective, Spady (Citation1970) and Tinto (Citation1975) assume that malintegration into the HE system and its institutions leads to dropout (Nicoletti Citation2019). Both scholars underline that dropout is the result of a process.

Spady’s (earlier) model (Citation1970, Citation1971), the model of the dropout process, assumes that family background characteristics link to a differential academic potential (ability, achievement) and a differential normative congruence in terms of the fit between the dispositions, attitudes, and expectations of the student, and the expectations and behavioural demands of the HE institutional environment. Both academic potential and normative congruence are associated with students’ intellectual development and achievement (grade performance), and – mediated by these factors – social integration, reflected in interactions with other individuals in the context of the HE institution. Friendship support also appears to function as a mediator for the link between normative congruence and grade performance, intellectual development, and social integration. According to Spady’s model, social integration is strongly linked to satisfaction, institutional commitment and, finally, to the decision to drop out.

Tinto’s model (Citation1975), as a conceptual schema of dropout, includes the distinction between the academic system of the educational institution, and the academic integration of the student with the social system of the educational institution, as well as the social integration of the student. In detail, the model assumes that individual characteristics, such as family background, individual attributes, and pre-HE experiences (e.g. experiences and achievement in secondary school), are associated with both goal and institutional commitments at the start of the HE career. While goal commitment relates to orientations towards the acquisition of knowledge, institutional commitment is defined as ‘whether the person’s educational expectations involved any specific institutional components which predispose him toward attending one institution (or type of institution) rather than another’ (Tinto Citation1975, 93). Interpreting this description, this relates to a strong initial aspiration to experience HE, if not a specific HE institution. These initial commitments are associated with the integration of the student into the academic system of the study institution – as indicated by grade performance and intellectual development – and the integration into the social system, which is indicated by interactions with student peers and interactions with faculty members. A lack of academic and social integration leads to a lack of (goal and institutional) commitment, and eventually to a decision to drop out.

A current refinement of the model by Tinto (Citation1993) explicitly includes a timeline that emphasises the processual character of the explanatory dropout model. Furthermore, the role of intentions in terms of educational aspirations and learning motivation is highlighted in the description of the commitment aspects.

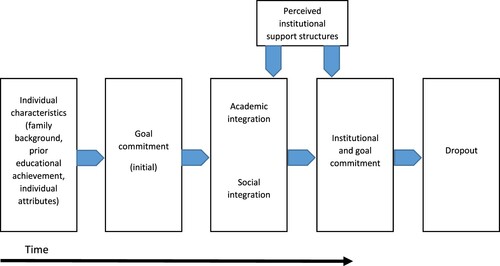

While the integration with – and commitment to – the HE institution are at the core of the model, the conceptual frame does not explicitly link institutional characteristics and student integration and commitment. However, this is vital, given that a student’s integration is not a passive, one-sided process. Universities differ in terms of actual services provided and service orientation, but also regarding whether and how such services are acknowledged and perceived by the students. Thus, we refine the model by introducing the general issue of (perceived) characteristics of the institution that supposedly shape the experiences of the student, and, thus, academic and social integration, as well as commitment. depicts the main assumptions of the Tinto models, and includes the additional feature of institutional characteristics.

Figure 1. Conceptual core of the Tinto Model and additional feature. Note: adapted depiction, based on Tinto (Citation1975).

State of research

Drawing upon different conceptual perspectives, previous research has effectively elaborated the drivers of student dropout.

Individual level characteristics. Individual factors associated with dropout risk include students’ starting conditions (e.g. ascriptive criteria) and their achievements prior to HE entrance. Socioeconomic background, parental level of education, and average grade at completion of secondary school are additional factors that can determine dropout intention. For instance, students coming from non-academic households or disadvantaged backgrounds are exposed to a higher risk of dropout (Georg Citation2009; Vignoles and Powdthavee Citation2009). One explanation for this is a lack of social and cultural resources, or of knowledge on respective norms and values in relation to HE that are commonly shared by students with an academic background, specifically an academic habitus (Lehmann Citation2007). Furthermore, particularly in countries with high tuition fees, economic resources and living arrangements matter as well. Students who work for a high number of hours alongside their studies, and who stay in the parental household, are at higher risk of study attrition (Bozick Citation2007). However, several studies (e.g.| Rumberger et al. Citation1990) questioned the direct influence of parents’ economic characteristics on the dropout intention of students, arguing that non-monetary factors such as the extent of parental involvement in students’ decisions and study progress are crucial for completing studies or dropping out. In addition, students’ lack of commitment towards HE in general, as well as in terms of the respective field of study – as a key explanation in the concepts of Spady (Citation1971) and Tinto (Citation1975) – has been identified as one of the main reasons for why students intend to drop out (Georg Citation2009).

Additionally, previous research has been controversial with regard to its findings on dropout intentions among women and men, by considering the former a minority, especially in male-dominated educational settings and programmes. While some studies found no gender differences (Guzmán and Kingston Citation2012), others showed unequal dropout rates between men and women depending on academic achievement, the field of study, or care responsibilities (Conger and Long Citation2010; Quinn Citation2013).

Furthermore, international students, namely students who have obtained their HE entrance qualification in another country, and immigrated to a host country to pursue their studies, may face several challenges when starting their studies, as they not only have to integrate into the HE environment, but also face language barriers, and have to deal with cultural differences in teaching and learning, or isolation. In this vein, the institutional support structures provided by the HE institution might be particularly vital for international students during the integration process.

Kercher (Citation2018) found that international students are more likely to drop out of German HE. However, this particularly referred to students of European origin compared to students originating from Asian countries – likely pointing to the fact that these students are a preselected group in terms of motivation, who are particularly determined to succeed in the host country. In fact, in major target countries for international students, such as the US or Australia, international students are more likely to complete their studies in time, and this could be related to these students’ full-time enrolment status or cost pressure (Kercher Citation2018). As one of the few studies that considers local, international, and immigrant background students separately, Da Silva et al. (Citation2017) found that both international and immigrant background students faced a greater dropout risk compared to the non-migrant background students at a large Canadian research university.

Students’ migration background or ethnicity matters as well. For instance, ethnic minorities are more likely to drop out from HE in the US context (Thompson, Johnson-Jennings, and Nitzrim Citation2013; Arbona, Fan, and Olvera Citation2018). In Europe, studies create an ambiguous picture with regard to immigrant status (namely students who obtained their HE entrance qualification within the respective country), but this is likely to be a result of the fact that immigrant status is a heterogeneous category in itself. On the one hand, immigrants may lack information and knowledge on the organisation of HE studies in the host country, but on the other, they represent a positively selected group, as they likely demonstrate high achievements throughout their educational career, and enrol in HE (Støren Citation2009; Reisel and Brekke Citation2010; Van Houtte and Stevens Citation2010).

Students with an immigrant background may drop out for very different reasons. In many European countries, immigration background intersects closely with a low social origin, given that many students have low-skilled parents. As a consequence, they could lack the above-mentioned resources needed to succeed in HE (Brinbaum and Guégnard Citation2013; Camilleri et al. Citation2013; Heublein Citation2014). Furthermore, adolescents with an immigrant background have been found to have high ambitions overall to attain a HE degree, despite low academic achievement. As a consequence, they may have to leave HE more often due to poor academic performance. However, the difference in the dropout risk of students with an immigrant background differs by HE system – suggesting that the institutional structures of the HE system have a vital mediating role (Reisel and Brekke Citation2010). Thus, within a highly stratified education system, young people with an immigrant background may face greater obstacles in reaching HE in Luxembourg from the beginning (Griga and Hadjar Citation2014).

Institution-related factors. On the other hand, institutional conditions, such as the study environment, modalities of particular study programmes, size, expenditure, institutional selectivity, or teaching quality, shape further drivers of dropout (Pascarella et al. Citation2004; Georg Citation2009; Chen Citation2012). These not only relate to established social ties and activities between students that foster social inclusion and the feeling of belonging, but also to the quality of studies and characteristics of the HE institution and faculty. A lack of study skills or deficit in self-identification with the HE institution would cause a ‘delayed selection’ (Heublein, Spangenberg, and Sommer Citation2003): a late realisation of not belonging to a study programme or the entire HE system. While previous research has shown that individual academic and social integration are important to counteract dropout (Collings, Swanson, and Watkins Citation2014; Dahm and Lauterbach Citation2016; Truta, Parv, and Topala Citation2018), it has barely explored the dimension of institutional support and effort put into the retention of students. This is especially true for dimensions such as satisfaction with various institutional material and non-material provisions, as well as the involvement of the faculty in students’ learning process (Brown and Mazzarol Citation2009; Nadiri, Kandampully, and Hussain Citation2009).

Differentiating dropout from HE and dropout from study programmes. HE researchers increasingly differentiate different types of dropout, such as leaving HE for good, leaving a study programme or a HE institution, and also acknowledge that HE dropout is a reversible decision. However, drivers or mechanisms of these different dropout types have not yet been explicitly considered conceptually. Such different types of dropout are likely differentially linked to students’ initial commitment and the certainty with which students’ have made their study choice. Furthermore, HE integration and the orientation process into and within HE matters (Rodríguez-Gómez et al. Citation2016). Meggiolaro, Giraldo, and Clerici (Citation2017) found that study programme dropout is, in contrast to HE dropout, less often the result of poor academic achievement, given their finding that the academic performances prior to HE enrolment of students that dropped out from their study programmes were similar to those of persisting students.

The context: HE in Luxembourg

The HE sector of small and multicultural Luxembourg has become a vital means of diversifying and strengthening its economy (Harmsen and Powell Citation2018). The majority of students enrol at the only research-focused flagship university, established in 2003, which offers HE degrees at all levels. Private, mostly field-specific, HE exists, but is negligible in terms of overall student enrolment (OECD Citation2019, 153), whereas there is another major share of enrolment for vocationally oriented short-cycle (i.e. two-year) programmes (Formations au Brevet de Technicien Supérieur, BTS) at the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 5 level, which is usually offered by public vocational or upper-secondary schools. Most of the study programmes are constructed as initial educational full-time studies. Study conditions are attractive because of their comparatively generous public funding, low tuition fees, modern study infrastructure, and the small cohort sizes of most study programmes (Powell Citation2014, 120; OECD Citation2019, 264).

Given the favourable economic situation, study conditions, and emphasis on internationalisation and multilingualism, Luxembourg attracts many international students (Harmsen and Powell Citation2018). Among OECD countries, it has by far the most international student body (OECD Citation2019, 228): only about 40 percent of all students are of Luxembourgish origin, but there is a great variation by degree type: whereas international students are in the minority in the short-cycle programmes, 85 percent of all doctoral students are non-Luxembourgish (University of Luxembourg [UL] Citation2018; OECD Citation2019, 233). Yet, the low share of local students is also driven by the fact that most school leavers refrain from studying in Luxembourg, thus conforming to a long tradition among Luxembourgish families of obtaining university education abroad (Rohstock and Schreiber Citation2013).

With regard to dropout, on the one hand we may expect that the favourable study conditions in terms of study infrastructure, low fees, small student cohorts, and the international environment may facilitate overall integration into the academic environment, particularly for international students as well. On the other hand, the international, multicultural, and multilingual environment may be overwhelming and challenging for other students. Furthermore, financial stress may be an issue, as international students may underestimate the living and housing costs despite the low tuition fees.

Methodology

Data base

The analysis is based on the Luxembourgish Eurostudent VII data. Eurostudent is a recurring, cross-sectional survey covering HE students, which is conducted in many European countries. Objectives of this survey include the establishment of policy-relevant national monitoring structures, thus facilitating country comparisons so as to review and improve the social dimension of HE. Major themes covered relate to students’ living, socioeconomic, and study conditions. The study is run by a European consortium that is managed by the German Center for Higher Education Research and Science Studies (DZHW) in Hanover, Germany (e.g. DZHW Citation2018). The first Eurostudent studies were carried out in 1997 (pilot) and in 2000 (wave 1).

Students in Luxembourg participated for the first time in 2019 (Eurostudent VII). As the HE system in Luxembourg is quite small, the survey has been set up as a census of all HE students in all recognised degree-granting HE institutions in Luxembourg, namely, both public and private ones. The survey was constructed as a Computer Assisted Web Interview (CAWI) questionnaire. All students were invited to the survey via an e-mail sent out by their HE institutions. Furthermore, students were informed and reminded of the ongoing data collection phase on campus by handing out flyers, making short announcements before lectures and providing small participation incentives (chocolate bars). As indicated, the population covered includes all students who were enrolled in HE programmes in Luxembourg in the academic year 2018/2019, consisting of students from the first to the final year of their studies. The population includes students in (vocationally oriented) short-cycle tertiary study programmes (BTS), classified as level 5 of the International Standard Classification for Education (ISCED), bachelor’s students (ISCED level 6), master’s students (ISCED level 7) and PhD candidates who are all attending doctoral education at the University of Luxembourg (ISCED level 8). Although PhD candidates are not part of the harmonised Eurostudent target sample population, they have been included in the target population of the Luxembourgish data collection. The net sample, after data cleaning (i.e. the exclusion of incomplete surveys), amounts to 871 students. This corresponds to a survey response rate of 17.9 percent of the non-harmonised sample. Overall, this is a favourable outcome in comparative terms, given the often much lower gross return rates in other participation countries that conduct Eurostudent as a full population survey (cf. Appendix C3; Hauschildt et al. Citation2021). After listwise exclusion of item non-response cases regarding the x-variables (while missing cases of the dependent variables were imputed via the full information maximum likelihood FIML procedure that is default in Mplus), the sample amounts to 744 students. All displayed results are subject to post-survey weighting. These are based on an alignment with the official student numbers and characteristics in terms of HE institution type, degree type, field of study, nationality, age, and gender.

The Eurostudent project relates to a trend study. The single surveys are cross-sectional. However – and this is of importance regarding the processual character of the dropout concept – the surveys include retrospective elements that allow for an analysis of individual data relating to different stages of their educational career.

Measurements

displays the operationalisation of the major concepts. We distinguish between two different types of dropout intentions. Students’ responses were dichotomised, as the distribution of the variables appear to be extremely skewed (with a large majority indicating no dropout intentions), to generate two dependent binary variables: those seriously considering dropping out of one’s study programme and of HE entirely. The measurements for academic and social integration, as well as commitment and institutional support, have been developed within the Eurostudent framework (Eurostudent Consortium Citation2021), and are based on previous scales of the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS) in Germany (Dahm and Lauterbach Citation2016).

Table 1. Overview of variables and operationalisation of major concepts.

Analytical strategy

As the theory-driven hypothetical model at the core of our analysis resembles the Spady–Tinto approach with its complex associations, structural equation modelling (SEM) appears to be the appropriate data analysis technique. The SEM approach seems to be especially useful in fitting the processual nature of the conceptual background of the Spady–Tinto approach and adequately analysing the mediating functions of the Spady–Tinto core factors of commitment and integration. The SEM method allows for an analysis of complex relationships, as not only are direct links on a dependent variable such as dropout taken into account, but also indirect effects via mediating variables. To study dropout based on the Spady–Tinto approach, as well as on our additional interest in perceived institutional provisions (satisfaction), we estimated a structural equation model using Mplus 7.3 (Muthén and Muthén Citation1998–2014). As some of the variables are categorical dependent variables, we used the weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator mode for an adequate estimation of path coefficients.

Results

To gain an initial insight into group-specific dropout intention scores, we first present descriptive statistics, before elaborating on the complex mechanisms employing structural equation modelling in a theory-driven way.

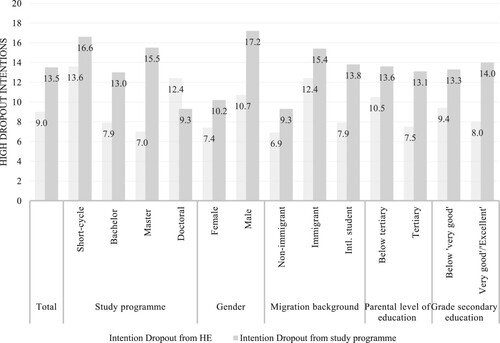

Descriptive findings on the dropout intentions by selected variables indicate different dropout patterns structured by study programme, gender, migration background, and educational background ().

Figure 2. Dropout intentions by selected variables (in percent). Data Source: Eurostudent VII Luxembourg, N = 871, weighted (age, gender, nationality, study programme/degree type, field of study).

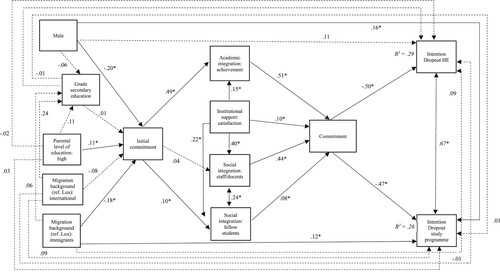

As outlined above, structural equation modelling (Mplus 7.3; Muthén and Muthén Citation1998–2014) is employed to analyse the complex model based on the Spady–Tinto conceptual approach. The goodness of fit is highly satisfactory since the major threshold is met (root mean square error of approximation, RMSEA < .06; Hu and Bentler Citation1999). However, the hypothetical model still differs significantly from the empirical model (data) if the five percent significance convention is applied. This may be due to the high complexity of the model that usually comes with lower average goodness-of-fit indices.

The results are depicted in . As expected, the dropout intention is strongly associated with commitment, whereas its lack increases the likelihood of both the intention to leave HE entirely and to leave the study programme. A lack of commitment during studies is linked to a lower academic integration – regarding both docents and fellow students – and a lower social integration, as outlined in the classic Spady–Tinto models (Tinto Citation1975). In line with the Spady–Tinto approach, initial commitment shows a profound positive association with academic integration and social integration. However, a detailed look shows that initial commitment is significantly positively associated with social integration with respect to faculty members/docents, but not with social integration with respect to fellow students. Regarding the role of socioeconomic factors and previous educational experiences (grade/achievement in secondary education), we take into account the links between socioeconomic factors and these previous educational experiences, in addition to the direct links postulated in the classic models (Tinto Citation1975). This leads us to represent a different picture: gender matters, with women showing a stronger initial commitment than men. Positive previous educational experiences, namely a higher achievement (grade) in secondary education, is not associated with initial commitment to HE. Social origin, namely the parental level of education, is linked to initial commitment, but interestingly does not indirectly via previous achievements (grade, secondary education). With regard to immigrant background, immigrants who transitioned from the secondary education system of Luxembourg to HE show a lower initial commitment than non-immigrants of Luxembourgish origin.

Figure 3. Structural equation model on intentions to drop out from HE and study programme. Notes: Mplus, ESTIMATOR = WLSMV, standardised estimates (* Significance level: p ≤ .05), Clusters: study programmes. Goodness of Fit: Χ2 = 51.048, df = 35, p = .039; RMSEA = .025W. Data Source: Eurostudent VII Luxembourg, N = 744, weighted (age, gender, nationality, study programme/degree type, field of study).

The quality of institutional support structures, operationalised as the students’ satisfaction with certain provisions of their institution (for instance, in facilitating studying, compensating for financial difficulties, and allowing for a good family life–study balance), shows a profound association with all integration variables. If the institution is perceived as doing well in supporting the students in the above-mentioned matters, students show a higher academic integration (achievement) and a higher social integration, with regard to both faculty members/docents and their fellow students.

Regarding the mediating function of the commitment and integration factors, the association of the socioeconomic variables on dropout from HE seem to be entirely mediated by these factors, while some direct association remains with regard to dropout from a study programme. In particular, male gender and being of migrant origin is still associated with a higher intention to drop out from the current study programme, even if all the other mediating factors are considered.

Finally, the two types of dropout intentions, namely the intention to drop out from HE in general and the intention to drop out from the current study programme, appear to be strongly linked. Nevertheless, they relate to two distinct phenomena.Footnote1

Discussion

As highlighted at the beginning of this article, dropout is a theme of major concern stressed by policy makers, HE researchers and practitioners. The aim of this study was twofold. First, we revisited and refined the classic Spady–Tinto approach to dropout (based on Spady Citation1971; Tinto Citation1975, Citation1993), giving special emphasis to the link between individual background characteristics, study commitment and integration. In particular, in addition to other background characteristics, we considered students’ immigration background in more detail than is usually done, namely by differentiating students with and without immigrant background as well as international students. Furthermore, stressing the role of the institutional HE environment in regard to the dropout decision, we also considered perceived institutional support. Second, we investigated the dropout intentions of students enrolled in the Luxembourgish HE system, a largely diversified and internationalised HE environment that can be deemed an example of the HE model of the future. This study employed the Eurostudent VII data, which include information on short-cycle, bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral students and, after weighting, represent the current HE student population in Luxembourg.

The Spady–Tinto approach – particularly the Tinto (Citation1975) model – could be reproduced based on current Luxembourgish data. The paths of the structural equation model resembled the hypothetical scenario derived from the concepts of Spady (Citation1971) and Tinto (Citation1975, Citation1993) on the linkages between individual characteristics, initial commitment to HE, academic and social integration, commitment (during studies), and dropout intention. Non-intuitive findings only relate to prior performance (secondary education) as an individual characteristic that showed no association with any of the factors, as well as the lack of a link between initial commitment and the social integration regarding fellow students. Initial commitment seems to be more important for social integration regarding teaching staff and faculty contacts than with regard to social relationships with fellow students. The perceived institutional support, a factor we emphasised refining the Spady–Tinto approach, was significantly positively linked to academic integration, social integration (fellow students, docents), and commitment. Perceiving support from the institution with regard to study support services, learning facilities, balancing studies, family, paid jobs, and future career prospects appears to have a key role in the prevention of dropout.

Focusing specifically on different immigration background groups, this study showed that students with an immigrant background more often intended to drop out than students without an immigration background and international students. The latter might be better prepared for HE, and specifically in the international and multilingual study environment of Luxembourg, integration may work well for these students, but at the same time – due to their experiences – they may more critically evaluate study conditions. Regarding immigrant background students, they may lack adequate cultural resources to compensate for any shortcomings pertinent to the new study environment. Thus, the initial commitment to HE of a (minor) proportion of these students may not be strong. Other studies also identified a higher dropout risk for (ethnic) minority students in some country-contexts, pointing to the fact that the institutional structures of an (higher) education system may mediate the link between minority status and dropout risk (Reisel and Brekke Citation2010). Consequently, this calls for a stronger anticipation of the macro-level context, including the structure of secondary education as an important preparatory stage towards HE (Griga and Hadjar Citation2014).

Parents’ level of education is directly associated with students’ initial commitment. This supports previous findings on parental support and interest in students’ overall study progress (e.g. Goldrick-Rab Citation2006; Zarifa et al. Citation2018). The missing path between initial commitment and social integration with regard to fellow students could also be partially attributed to the linkage between the two social integration aspects (students and docents). As both are linked to a medium extent, for those students who have neither relationships with fellow students nor docents, both aspects may contribute to low commitment.

Apart from refining the model by taking into account social and immigrant background, and disentangling the factors influencing the initial goal commitment of students at an individual level, we add to the international discussion on dropout from HE by exploring the dimension of institutional support. Bringing in several factors related to satisfaction, not only in the way the HE institution caters for students’ well-being and preparation for the labour market, but also with the faculty and so-called ‘service quality,’ we demonstrated that dropout intention does not solely depend on students’ characteristics. Satisfaction with several aspects of study programmes, such as peers, staff, and congruence with individual life plans, turned out to be a powerful instrument that can attract or discourage students (Li and Carroll Citation2020; Ammigan and Jones Citation2018; Kehm, Larsen, and Sommersel Citation2019).

Thus, HE institutions can counteract dropout – both from HE in general or from study programmes – by including students in the evaluation of study programmes, and by giving them a voice with regard to suggestions for the continuous improvement of respective programmes. At the same time, this points to the need for service orientation on the part of HE institutions towards very different social groups and the changed role of HE in society. The latter no longer means exclusiveness and attachment to HE as a matter of course, but rather has a smoothing function in relation to social inequalities, as inclusive institutions may foster upward mobility. Approaching distinct groups of students and offering them specific help would retain them in their study programmes. Possible ways for implementation are peer mentoring or information workshops for targeted groups to increase their understanding of how things work (Collings, Swanson, and Watkins Citation2014).

Finally, our study focused on two different types of dropout intentions. All in all, the mechanisms behind the intention to drop out from a study programme and the intention to entirely leave the HE system seem to be the same. Study commitment appears to be strongly related to both intentions. Differences only relate to the mediating function of the Spady–Tinto factors of commitment and integration in the link between socioeconomic factors and dropout intentions.

The limitations of our study include a relatively small sample size, the neglect of fields of study, the cross-sectional nature of our data that does not allow for causal inferences, and certain sample bias that we compensated for by employing weighting procedures. Limitations are outlined more in detail in the online appendix.

Based on our results, we believe that future studies investigating dropout intentions and starting from the concepts of Spady (Citation1971) and Tinto (Citation1975, Citation1993) need to incorporate the institutional dimension in an even more detailed way, in order to shed light on practices and services offered to students as help or support. Thus, commitment should not be treated as a one-sided phenomenon, as it is a result of the interplay of micro and meso levels of agency.

All in all, the concepts of Spady (Citation1971) and Tinto (Citation1975, Citation1993) still appear to be useful for sociological research on HE. Not only providing students with the skill resources they need before they enrol in studies, but also selecting students to ensure their strong academic and social integration (particularly with regard to student–faculty relations), thus fostering commitment to HE, can be regarded as the most promising tools to keep dropout rates low. The institution and its student support measures play a key role in this.

Authors’ contribution

The authors are listed based on their contribution to the article.

Code availability

This research has been performed using SPSS and MPlus software. The syntaxes are available upon request.

Data availability statement

Data relates to the international project EUROSTUDENT VII and is available upon request. The data are ethics-approved.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andreas Hadjar

Andreas Hadjar is a Full Professor of Sociology, Social Policy and Social Research at the University of Fribourg (CH), and is also conducting projects at the University of Luxembourg as a Professor of Sociology of Education. He received his PhD from Chemnitz University of Technology (DE) and his venia legendi Sociology from the University of Bern (CH). Main research interests include inequalities in education and beyond, education and welfare systems, subjective well-being, and research methods.

Christina Haas

Christina Haas is a post-doctoral researcher at the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories. Her research interests include comparative and processual perspectives on higher education, study trajectories and inequality in higher education using mainly quantitative research methods. In her dissertation, she compared the study trajectories of students in different institutional settings in Germany and the United States using large-scale panel data and a sequence-analytical approach.

Irina Gewinner

Irina Gewinner is a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Sociology, Leibniz Universität Hannover (DE). Her research interests include social inequalities in education and labour market; skilled migration, mobility and tourism; and cultural and gender studies. Her recent publications are ‘Understanding patterns of economic insecurity for post-Soviet migrant women in Europe’ (Frontiers in Sociology), and ‘Geschlechtsspezifische Studienfachwahl und kulturell bedingte (geschlechts)stereotypische Einstellungen’ (Career Service Papers).

Notes

1 For validity checks, we also ran separate models with either intention to drop out from HE in general or intention to drop out from a study programme as a dependent variable. The results are similar and the mechanisms, namely the direct and indirect effects via the commitment and integration variables, also function in a similar way.

References

- Ammigan, R., and E. Jones. 2018. “Improving the Student Experience: Learning from a Comparative Study of International Student Satisfaction.” Journal of Studies in International Education 22 (4): 283–301.

- Arbona, C., W. Fan, and N. Olvera. 2018. “College Stress, Minority Status Stress, Depression, Grades, and Persistence Intentions Among Hispanic Female Students: A Mediation Model.” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 40 (4): 414–430.

- Belloc, F., A. Maruotti, and L. Petrella. 2010. “University Drop-Out: An Italian Experience.” Higher Education 60 (2): 127–138.

- Berger, J. B., and J. M. Braxton. 1998. “Revising Tinto’s Interactionalist Theory of Student Departure Through Theory Elaboration.” Research in Higher Education 39 (2): 103–119.

- Bozick, R. 2007. “Making it Through the First Year of College: The Role of Students’ Economic Resources, Employment, and Living Arrangements.” Sociology of Education 80 (3): 261–285.

- Brinbaum, Y., and C. Guégnard. 2013. “Choices and Enrollments in French Secondary and Higher Education: Repercussions for Second-Generation Immigrants.” Comparative Education Review 57 (3): 481–502.

- Brown, R. M., and T. M. Mazzarol. 2009. “The Importance of Institutional Image to Student Satisfaction and Loyalty Within Higher Education.” Higher Education 58 (1): 81–95.

- Camilleri, A. F., D. Griga, K. Mühleck, K. Miklavic, F. Nascimbeni, D. Proli, and C. Schneller. 2013. Evolving Diversity II: Participation of Students with an Immigrant Background in European Higher Education. Brussels: MENON Network.

- Chen, R. 2012. “Institutional Characteristics and College Student Dropout Risks: A Multilevel Event History Analysis.” Research in Higher Education 53 (5): 487–505.

- Collings, R., V. Swanson, and R. Watkins. 2014. “The Impact of Peer Mentoring on Levels of Student Wellbeing, Integration and Retention.” Higher Education 68 (6): 927–942.

- Conger, D., and M. C. Long. 2010. “Why Are Men Falling Behind? Gender Gaps in College Performance and Persistence.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 627 (1): 184–214.

- Dahm, G., and O. Lauterbach. 2016. “Measuring Students’ Social and Academic Integration.” In Methodological Issues of Longitudinal Survey, edited by H.-P. Blossfeld, J. von Maurice, M. Bayer, and J. Skopek, 313–329. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Da Silva, T. L., K. Zakzanis, J. Henderson, and A. V. Ravindran. 2017. “Predictors of Post-Secondary Academic Outcomes Among Local-Born, Immigrant, and International Students in Canada.” Canadian Journal of Education 40 (4): 543–575.

- Durkheim, É. [1897] 2010. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. Glencoe: The Free Press.

- DZHW (German Center for Higher Education Research and Science Studies). 2018. Social and Economic Conditions of Student Life in Europe. EUROSTUDENT VI 2016–2018. Synopsis of Indicators. Bielefeld: wbv.

- European Commission, Education and Culture. 2015. Dropout and Completion in Higher Education in Europe. Main Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Eurostudent Consortium. 2021. Eurostudent VII. Questionnaire Handbook. Hanover: DZHW.

- Georg, W. 2009. “Individual and Institutional Factors in the Tendency to Drop Out of Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 34 (6): 647–661.

- Goldrick-Rab, S. 2006. “Following Their Every Move: An Investigation of Social-Class Differences in College Pathways.” Sociology of Education 79 (1): 67–79.

- Griga, D., and A. Hadjar. 2014. “Migrant background and higher education participation in Europe.” European Sociological Review 30 (3): 275–286.

- Guzmán, J. F., and K. Kingston. 2012. “Prospective Study of Sport Dropout: A Motivational Analysis as a Function of Age and Gender.” European Journal of Sport Science 12 (5): 431–442.

- Harmsen, R., and J. J. W. Powell. 2018. “Higher Education Systems and Institutions, Luxembourg.” Encyclopedia of International Higher Education Systems and Institutions, doi:10.1007/1978-1094-1017-9553-1001_1398-1001.

- Hauschildt, K., C. Gwosć, H. Schirmer, and F. Wartenbergh-Cras. 2021. Social and Economic Conditions of Student Life in Europe. EUROSTUDENT VII Synopsis of Indicators 2018–2021. Hanover: DZHW.

- Heublein, U. 2014. “Student Drop-out from German Higher Education Institutions.” European Journal of Education 49 (4): 497–513.

- Heublein, U., H. Spangenberg, and D. Sommer. 2003. Ursachen des Studienabbruchs: Analyse 2002. Hanover: HIS.

- Hu, L., and P.-M. Bentler. 1999. “Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6 (1): 1–55.

- Hurtado, S., and D. F. Carter. 1997. “Effects of College Transition and Perceptions of the Campus Racial Climate on Latino College Students’ Sense of Belonging.” Sociology of Education 70 (4): 324–345.

- Kehm, B. M., M. R. Larsen, and H. B. Sommersel. 2019. “Student Dropout from Universities in Europe: A Review of Empirical Literature.” Hungarian Educational Research Journal 9 (2): 147–164.

- Kercher, J. 2018. Academic Success and Dropout Among International Students in Germany and Other Major Host Countries. Bonn: DAAD.

- Lehmann, W. 2007. ““I Just Didn’t Feel Like I fit in”: The Role of Habitus in University Dropout Decisions.” Canadian Journal of Higher Education 37 (2): 89–110.

- Li, I. W., and D. R. Carroll. 2020. “Factors Influencing Dropout and Academic Performance.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 42 (1): 14–30.

- Mannan, M. A. 2007. “Student Attrition and Academic and Social Integration: Application of Tinto’s Model at the University of Papua New Guinea.” Higher Education 53: 147–165.

- Meggiolaro, S., A. Giraldo, and R. Clerici. 2017. “A Multilevel Competing Risks Model for Analysis of University Students’ Careers in Italy.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (7): 1259–1274.

- Muthén, L. K., and B. O. Muthén. 1998–2014. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

- Nadiri, H., J. Kandampully, and K. Hussain. 2009. “Students’ Perceptions of Service Quality in Higher Education.” Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 20 (5): 523–535.

- Nicoletti, M. 2019. “Revisiting the Tinto's Theoretical Dropout Model.” Higher Education Studies 9 (3): 52–64.

- OECD. 2010. How Many Students Drop Out of Tertiary Education?” Highlights from Education at a Glance 2010. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD. 2019. Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Pascarella, E. T., C. T. Pierson, G. C. Wolniak, and P. T. Terenzini. 2004. “First-Generation College Students: Additional Evidence on College Experiences and Outcomes.” The Journal of Higher Education 75 (3): 249–284.

- Piepenburg, J. G., and J. Beckmann. 2021. “The Relevance of Social and Academic Integration for Students’ Dropout Decisions. Evidence from a Factorial Survey in Germany.” European Journal of Higher Education, 1–22. doi:10.1080/21568235.2021.1930089.

- Powell, J. J. W. 2014. “International National Universities: Migration and Mobility in Luxembourg and Qatar.” In Internationalization of Higher Education and Global Mobility, edited by B. Streitwieser, 119–133. Oxford: Symposium.

- Quinn, J. 2013. Drop-Out and Completion in Higher Education in Europe Among Students from Under-Represented Groups. NESET: European Commission.

- Reisel, L., and I. Brekke. 2010. “Minority Dropout in Higher Education: A Comparison of the United States and Norway Using Competing Risk Event History Analysis.” European Sociological Review 26: 691–712.

- Rodríguez-Gómez, D., J. Meneses, J. Gairín, M. Feixas, and J. L. Muñoz. 2016. “They Have Gone, and Now What? Understanding Re-Enrolment Patterns in the Catalan Public Higher Education System.” Higher Education Research & Development 35 (4): 815–828.

- Rohstock, A., and C. Schreiber. 2013. “The Grand Duchy on the Grand Tour: A Historical Study of Student Migration in Luxembourg.” Paedagogica Historica 49 (2): 174–193.

- Rumberger, R. W., R. Ghatak, G. Poulos, P. L. Ritter, and S. M. Dornbusch. 1990. “Family Influences on Dropout Behavior in one California High School.” Sociology of Education 63 (4): 283–299.

- Spady, W. G. 1970. “Dropouts from Higher Education: An Interdisciplinary Review and Synthesis.” Interchange 1: 64–85.

- Spady, W. G. 1971. “Dropouts from Higher Education: Toward an Empirical Model.” Interchange 2: 38–62.

- Støren, L. A. 2009. Choice of Study and Persistence in Higher Education by Immigrant Background, Gender, and Social Background. NIFU-Rapport 2009: 43. Oslo: NIFU.

- Thompson, M. N., M. Johnson-Jennings, and R. S. Nitzrim. 2013. “Native American Undergraduate Students' Persistence Intentions: A Psychosociocultural Perspective.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 19 (2): 218–228.

- Tinto, V. 1975. “Dropout from Higher Education: A Theoretical Synthesis of Recent Research.” Review of Educational Research 45 (1): 89–125.

- Tinto, V. 1993. Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes of Student Attrition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Truta, C., L. Parv, and I. Topala. 2018. “Academic Engagement and Intention to Drop Out.” Sustainability 10 (12): 4637.

- University of Luxembourg (UL). 2013. Report 2013. Key Performance Indicators. Esch-sur-Alzette: University of Luxembourg.

- University of Luxembourg (UL). 2018. Year in Review: 2018. Report. Esch-sur-Alzette/Luxembourg.

- Van Houtte, M., and P. A. J. Stevens. 2010. “School Ethnic Composition and Aspirations of Immigrant Students in Belgium.” British Educational Research Journal 36 (2): 209–237.

- Vignoles, A., and N. Powdthavee. 2009. “The Socio-Economic Gap in University Dropout.” The BE Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy 9 (1): 1–36.

- Yair, G., N. Rotem, and E. Shustak. 2020. “The Riddle of the Existential Dropout: Lessons from an Institutional Study of Student Attrition.” European Journal of Higher Education 10 (4): 436–453.

- Zarifa, D., J. Kim, B. Seward, and D. Walters. 2018. “What’s Taking You So Long? Examining the Effects of Social Class on Completing a Bachelor’s Degree in Four Years.” Sociology of Education 91 (4): 290–322.

Appendix

Limitations of the research (long version)

The limitations of our study are, first, rooted in a relatively small sample size that, admittedly, reflects a rather small, yet diverse, overall student population in Luxembourg. As a comprehensive monitoring of students’ pathways after entering Luxembourgish HE does not exist, a comparison of official dropout numbers with our intention-to-dropout concept is not possible. While this conceptual definition may underestimate involuntary dropout due to academic failure, survey data have the advantage of being a rich source capturing students’ perceptions and thus allow for a more fine-grained exploration of relationships between sociodemographic background categories, socio-psychological concepts and dropout. Second, differentiating fields of study might result in further insights with regard to the social inequalities underlying dropout intention. We had to refrain from making such distinctions due to the limited sample size. Third, structural equation modelling (SEM) as a statistical method relies on causal assumptions. While our survey reflects a temporal–processual dimension by asking students how they felt about their study decision at different points in time, specifically prior to enrolment and at the time of the survey, our data are of a retrospective nature, but do not resemble panel data. Thus, although our research design does not allow for causal interpretations, the specific retrospective design of the survey items should prevent drawing reverse causal conclusions. Fourth, the survey was planned as a census, that is to say, each student on each tertiary level received an e-mail invitation, but the return rate was below 20 percent. However, administrational data on the population allowed for weighting procedures to compensate for bias regarding some major sociodemographic characteristics, degree and HE type. Nevertheless, we cannot fully account for survey participation bias and related unobserved heterogeneity.