?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Choosing a course of study is one of the most consequential decisions a university student will make. While there is considerable literature investigating how personality influences students’ choice of discipline, there is currently no evidence about how students cluster in disciplines relative to their civic-mindedness. This is an important gap in knowledge for faculty and staff who are increasingly implementing programmes and curricula aimed at developing civic-mindedness. Using data from a survey conducted at a single Dutch university (N = 1514) conducted prior to the start of first-year students’ undergraduate studies, we estimated a confirmatory factor analysis model to measure two constructs related to civic-mindedness, Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy, and personality traits included in the five-factor model. We present distributions of these traits across disciplines of study and show large differences between disciplines in both measures of civic-mindedness. We also found that a model including personality, Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy explained a small, but non-trivial (six percent) amount of the variation in discipline selection. A better understanding of the distribution of civic-mindedness across disciplines will help educators and policy makers develop types of civic education that are better suited to the heterogeneity of today’s student population.

Choosing a course of study is one of the most important academic decisions an undergraduate student will make. There is a substantial literature exploring how students make this decision. Economic returns to education (e.g. Long, Goldhaber, and Huntington-Klein Citation2015; Patnaik, Wiswall, and Zafar Citation2021), social identity groups such as race, gender and immigration (e.g. Morgan, Gelbgiser, and Weeden Citation2013; Orrenius and Zavodny Citation2015; Riegle-Crumb et al. Citation2012, Citation2018), and psychological attributes such as personality (e.g. Porter and Umbach Citation2006; Vedel Citation2016) have all been studied relative to their influence on this choice. However, at a time when many universities are focusing on public and community service education for their undergraduate students (Colby et al. Citation2003; Dungy Citation2012; Eurydice Citation2018), there is little understanding about how civic-mindedness is distributed across disciplines of study. This paper sheds new light on this question, connecting students’ personality attributes and civic-minded orientations with their propensity to enrol in different disciplines of study.

Understanding the ex-ante distribution of civic-mindedness across disciplines is important for both pedagogical resource allocation and for understanding the effects of educational programmes. Universities have historically conceptualised their missions as teaching and research, but European universities are facing both external and internal pressure to prioritise a socially engaged ‘third mission’ (Marhl and Pausits Citation2011; Montesinos et al. Citation2008; Pinheiro, Langa, and Pausits Citation2015). While the conceptualisation of this third mission includes continuing education, valorisation of research through technology transfer and broader societal engagement (Marhl and Pausits Citation2011; Pausits Citation2015) a growing part of this third mission has been to shift the educational mission from a ‘focus on content’ to a ‘focus on content, abilities and values,’ and reconceptualizing the ideal graduate from ‘productive professional’ to ‘citizen-professional’ (Krčmářová Citation2011, 317). This has led universities to increase their offerings of civically-related coursework, including community service learning (CSL), intergroup dialog, and traditional, classroom-based coursework with socially relevant themes embedded in the curriculum (McCowan Citation2014; McIlrath, Aramburuzabala, and Opazo Citation2019; Sotelino-Losada et al. Citation2021).

The theory of action for a particular pedagogical approach or extracurricular programme may, therefore, rest on targeting students who are predisposed to civic-mindedness or, conversely, who are most in need of intervention. When looking at student outcomes, we may expect the learning experience within some disciplines or programmes to socialise students into more civic-minded individuals. However, a large part of the differences between student populations may be due to self-selection (Elchardus and Spruyt Citation2009; Meyer, Neumayr, and Rameder Citation2019; Steinberg, Hatcher, and Bringle Citation2011). To date, no heuristics about the distribution of civic-mindedness have been developed to guide the implementation or evaluation of civic educational activities. To address these gaps, this study examined the distribution of civic-minded orientations across disciplines and the additional predictive value, if any, of civic-mindedness on discipline selection beyond the personality traits of the five-factor model.

Discipline selection and student attributes

Theory of vocational choice

Holland’s (Citation1959) theory of vocational choice provides a theoretical framework in which to situate discipline choice relative to students’ personality traits. Holland’s (Citation1997) articulation of the model consists of three parts: an individual with a particular personality, a work environment that is conducive to some personalities and hostile to others, and a potential congruence between the two that allows workers to ‘exercise their skills and abilities, express their attitudes and values, and take on agreeable problems and roles’ (4). It predicts psychological stress if there is incongruence between a person and their vocational environment.

Although originally posited as a model to describe how individuals choose and thrive in their careers, the theory of vocational choice can also be applied to academic environments (Lounsbury et al. Citation2009). Researchers interested in higher education have widely appropriated its use—especially when evaluating how students choose and thrive in various fields of study—and by higher education professionals and counselling psychologists in how they advise students in educational and career choices (Nauta Citation2010; Rocconi, Liu, and Pike Citation2020; Xu Citation2013).

Civic-mindedness, service motivation, and civic efficacy

For this study we adopt Van der Meer and Van Ingen's (Citation2009) definition of civic-mindedness: ‘the propensity to think and care more about the wider world’ (281). While there are a wide variety of other related constructs (e.g. public service motivation, Civic Minded Graduate, etc.) the chosen definition is better suited to this study because of its specificity. By only including thinking and caring as the objects of interest, it excludes knowledge, skills, and behaviours. Our population of interest is students entering university; having only recently graduated from secondary school, this population is not likely to have had opportunities to engage in civic activities (e.g. vote), join civic organisations or engage in civic behaviours that would be measured by alternative constructs. This definition is also closely related to attitudes and dispositions that are relevant for educational programmes aimed toward creating ‘citizen-professional[s]’ (Krčmářová Citation2011, 317) through developing students’ willingness to make a meaningful contribution to the wider world.

Because the Van der Meer and Van Ingen (Citation2009) definition does not have an accompanying measurement tool, we chose two measures that, together, cover the construct of civic mindedness. These measures are Service Motivation (the willingness to help others in one’s working life) and Civic Efficacy (the belief to be able to bring about positive changes in the world). Previous research has shown personality accounts for about forty percent of the variation in Service Motivation and fifty percent of the variation in Civic Efficacy (Van Matre et al. Citation2022)—what Bainbridge, Ludeke, and Smillie (Citation2022) would classify as ‘peripheral or largely independent’ and ‘somewhat independent’ of the five-factor model, respectively—indicating that while closely related, they are distinct constructs from personality.

Current evidence on personality traits, civic-mindedness and discipline selection

The theory of vocational choice has been a useful lens in studying a variety of personality-related psychological constructs in relation to discipline selection. Authors have used Holland’s original six-factor occupational themes (Porter and Umbach Citation2006), the five-factor model of personality (Vedel Citation2016), measures of tough-mindedness and work drive (Lounsbury et al. Citation2009), measures of tendency for procrastination and academic dishonesty (Clariana Citation2013), and public service motivation (Perry and Wise Citation1990), among others within this framework.

Given its prevalence and acceptance in the psychology literature, the five-factor model—or individual factors of it—has been widely studied in relation to students’ selection of programmes of study (for a recent overview see Vedel Citation2016) as well as student success within those programmes (e.g. Gatzka and Hell Citation2018). For example, students studying in the arts and humanities tend to have a higher level of Openness to new experiences, lower levels of Conscientiousness, and higher levels of Neuroticism relative to those in engineering or the sciences (De Fruyt and Mervielde Citation1997; Kline and Lapham Citation1992; Lievens et al. Citation2002; Vedel, Thomsen, and Larsen Citation2015). While this literature provides important ideas and evidence on the association between personality traits and discipline choice, the question remains whether and how civic-mindedness is distributed differently across disciplines, and whether civic-mindedness explains any variation in students’ choices of discipline that personality cannot. As described above, vocational choice theory predicts distress if there is a lack of congruence between a student and their educational environment. For educators who develop civic education—like CSL courses or extracurricular civic activities—it is important to better understand the distribution of civic-mindedness of students at the start of their programmes. A vast body of theoretical and empirical work assumes that higher education can shape civic-mindedness (e.g. Bringle and Wall Citation2020; Steinberg, Hatcher, and Bringle Citation2011; Tijsma et al. Citation2020), embodied in a concept like ‘the civic minded graduate’. Other scholars however have cast doubts on the validity of the causal effect of educational experiences, arguing that it is rather civic minded students who self-select into civic education (e.g. Meyer, Neumayr, and Rameder Citation2019). While we do not provide an answer to this causality debate, our study does show distributions of civic-mindedness before students are exposed to any course in their undergraduate education, contributing to theories on academic choice and civic development. With civic education and community service becoming more prevalent in higher education programmes, it is important to know how students self-select into different fields of study.

Purpose of this study

This study sought to answer the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: How are civic orientations distributed across different academic disciplines of study?

RQ2: To what extent does civic-mindedness explain additional variation in students’ choices of major beyond the elements of the five-factor model? How do the relationships between personality and discipline of study change when accounting for civic-mindedness?

Given the literature that shows how personality is correlated with discipline selection, RQ2 interrogates whether civic-mindedness provides unique information about discipline selection beyond what personality can provide.

Data and methods

Survey administration

All first-year bachelors students at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam—a large, research university in the Netherlands—were invited to participate in an online survey from 21 May to 26 July 2021, before the start of academic instruction. This survey contained items related to personal and professional interests and was designed to support academic and career counselling initiatives at the university. The email invitation contained information about informed consent for participation and an estimate of the time commitment (20 min), and those who completed the survey were eligible to win computer tablets (approximately valued at €150 each) as an incentive to participate. Students received four additional reminders during the survey window. A data extract that contained only the discipline of study and the subset of responses to questions relevant to this study were provided to the researcher team; no personally identifiable information was included in the data set. These data were first collected and described by (Van Matre et al. Citation2022).

Of the 8,491 incoming students who were invited to complete this survey, 1,514 (17.8%) completed it and provided their consent to use their data in this study. We discuss this response rate in the context of other similar surveys in the Netherlands and the possible repercussions of survey non-response bias in the discussion section.

Personality and civic-mindedness

Personality was operationalised using the Dutch translation of the Big Five Inventory-2 (BFI-2; Denissen et al. Citation2020; Soto and John Citation2017), which has been shown to have comparable reliability in Dutch-speaking populations as its English counterpart (Denissen et al. Citation2020).

We use two measures to operationalise civic mindedness: Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy. The Service Motivation Scale uses a selection of items from the Public Service Motivation Scale (Perry and Wise Citation1990) and the Civic-Minded Graduate Scale (Steinberg, Hatcher, and Bringle Citation2011). It measures students’ relationships with the public purpose of education and careers (e.g. I feel a deep conviction in my career goals to achieve purposes that are beyond my own self-interest). Civic Efficacy Scale measures students’ attitudes of their own capacities to be effective in civic action (e.g. Realistically, I can do little to bring about changes in our society). The specific measure of Civic Efficacy that is included in the survey was a modified version of Weber et al.’s (Citation2004) Civic Efficacy Scale. Similar scales have been previously used among students in the Netherlands with satisfactory reliability (Heine, van Witteloostuijn, and Wang Citation2022; Munniksma et al. Citation2017). Table A1 lists the items associated with Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy.

Discipline

Students were able to indicate their degree programme from a pre-populated list of undergraduate programmes. Provided that students have the basic qualifications for a course (e.g. they have the appropriate diploma from a Dutch secondary school or foreign equivalent), Dutch universities operate largely on an open-enrolment basis. There are a small number of so-called ‘numerus fixus’ programmes, where there is a competitive application process (e.g. computer science, biomedical sciences). However, there is no discipline that is completely made up of numerus fixus degree programmes, and students who are not admitted can enrol in another course within the same discipline. As noted above, students responded to the survey prior to the commencement of courses; while all respondents had actively enrolled in their programme of choice, some may disenroll entirely or disenroll and reenroll in another programme prior to the commencement of courses. The latter would only effect our analysis if students enrolled in a programme outside their original discipline.

We used the 2015 version of the Dutch National Academic Research and Collaborations Information System’s (NARCIS) codes to categorise each degree programme into one of eight disciplinary groups (Data Archiving and Networked Services Citation2015): behavioural and educational sciences; economics and business administration; humanities; life sciences, medicine and health; law and public administration; social sciences; science and technology; interdisciplinary studies. provides descriptive statistics of survey responses by discipline.

Table 1. Summary Statistics of Survey Respondents.

Latent construct measurement

An analysis plan for this study was preregistered; see https://osf.io/5dpjf/. The data and statistical code needed for replication, including all data inclusion criteria and pre-analysis manipulation, has been made publicly available at OSF and can be accessed via the previous link. Data were analysed using Stata 17.0.

The items related to the Civic Efficacy and Service Motivation scales had Cronbach’s alpha statistics of 0.71 and 0.65, respectively, and the statistic for each personality domain fell between .78 and .88. We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to estimate each of the five personality domains and the two civic-mindedness constructs (this model is first described in Van Matre et al. Citation2022). The twelve items associated with each personality domain from the BFI-2 loaded onto five personality factors, and the five items associated with each civic construct loaded onto two factors; we did not permit any cross loadings between factors. We did not include any intermediate facet structure for the five-factor model (e.g. anxiety, depression, and emotional volatility for Neuroticism), and we explicitly modelled covariance across the personality domains and between the two civic constructs. We use a full information maximum likelihood estimator (i.e. MLMV).

In order to improve model fit, we include error correlations between manifest variables within the same personality or civic domain in a stepwise fashion based on calculated modification indexes (Sörbom Citation1989). We do not include correlations between errors of manifest variables within different personality or civic domains. Because of the large number of observed variables in the model (ρ = 70) the fit statistics are more complex to interpret. Likelihood ratio tests which produce χ2 statistics are measures of exact fit. As Shi, Lee, and Maydeu-Olivares (Citation2019) note, they ‘often reject the null hypothesis, especially in large samples, even when the postulated model is only trivially false’ (311). RMSEA meets the common benchmark of <.06 (Hu and Bentler Citation1999), and BIC and AIC statistics indicate stepwise improvement, especially over the first five models. The CFI and TLI do not reach the normally accepted benchmark of .95 (.87 and .85, respectively) (Hu and Bentler Citation1999; West, Taylor, and Wu Citation2014), although they improve through the iterative process. We used Model 7 as our preferred specification. We report stepwise changes to the model fit statistics in Table A2 in the Appendix.

We stored student-level linearly projected estimates for each of the five personality domains and both civic constructs. Resulting scores are normally distributed with a mean of 0 while the standard deviation was allowed to vary.

Multinomial regression

To address Research Question 2, we used student-level linear predicted values for each of the seven outcomes to estimate a multinomial logistic regression of the form:

(1)

(1) where programmes of study are represented by

to

, and the personality domains of the five-factor model derived from the SEM are represented by

,

,

,

, and

. S0 was set to the discipline with the largest number of respondents—Life Sciences, Medicine, and Health. We estimated four more models of the same type that progress in a stepwise fashion: Model 1 is depicted in Equation 1, Model 2 included only

(Service Motivation), Model 3 only included

(Civic Efficacy), Model 4 included both

(Service Motivation) and

(Civic Efficacy), and Model 5 included all five personality domains and both civic constructs.

Results

Distribution of civic constructs across disciplines

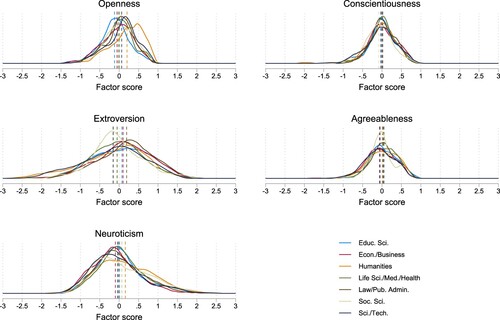

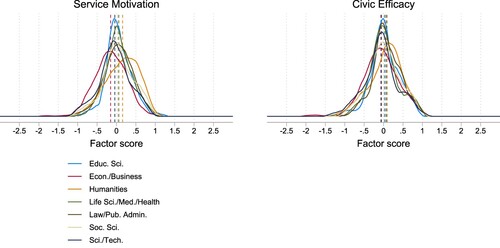

RQ1 asked how civic orientations are distributed across different academic disciplines of study. provides the means and standard deviations for students enrolled in each discipline across each of the five personality domains and two civic constructs. and show the full distributions for students in each discipline for the five personality domains and both civic constructs, respectively. Although the dispersion of the overall distributions is nearly identical for both constructs (SD [SM] = .39; SD [CE] = .41), the range of disciplinary means for the Service Motivation construct (-.15, .16) is wider than that for the Civic Efficacy construct (–.07, .09). Students enrolling in Economics and Business Administration have the lowest levels of Service Motivation, whereas students in the Humanities have the highest average, with a mean of approximately .4 standard deviations higher than average. Law and Public Administration students have the highest levels of Civic Efficacy, and Science and Technology students have the lowest levels.

Table 2. Summary Statistics of Latent Constructs by Discipline.

Civic-mindedness and discipline selection

RQ2 asked to what extent civic-mindedness explains additional variation in students’ choices of major beyond the elements of the five-factor model; it also asks how the relationships between personality and discipline of study change when accounting for civic-mindedness. shows the estimates from the multinomial logistic regressions described in Equation (1). With the log-likelihood ratio for each discipline as the dependent variable (relative to Life Sciences, Medicine, and Health as the baseline), column 1 shows the results for a model that only includes the personality domains, columns 2 and 3 show results for models that include only Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy, respectively. Column 4 shows results from a model that only includes Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy, and column 5 shows estimates for a model that includes personality domains and each civic construct. The model that includes personality accounts for about 4 percent of the variation in discipline choice (comparable to other recent studies of personality and discipline selection, e.g. Vedel, Thomsen, and Larsen Citation2015), while the model that includes both civic constructs explains a small but non-trivial amount of the variation in discipline selection, with pseudo statistic of .033. We find additional value to including Civic Efficacy and Service Motivation for the model that includes all seven constructs. The model that includes personality, Civic Efficacy and Service Motivation accounts for 6 percent of the variation in discipline selection (pseudo

= .06).

Table 3. Estimates for Multinomial Logistic Models of Discipline Selection.

We can divide the disciplines into two categories based on the multinomial logistic regression estimates across all five models in . The first category includes Behavioural and Educational Sciences; Humanities; Social Sciences; and Science and Technology. In these disciplines, there are meaningful patterns of association between either Service Motivation, Civic Efficacy, or both and the relative likelihood of enrolment in those disciples. However, the association disappears when also considering personality (Model 5). In the cases of the Humanities and Behavioural and Educational Sciences, Openness and Extraversion

have meaningful and statistically significant associations with the relative propensity to enrol in a degree programme in those disciplines (as shown in Model 1). However, enrolment in Behavioural and Educational Sciences does not have an association with either civic construct in Model 4 (similar to Social Sciences). Enrolment in the Humanities has a correlation only with Service Motivation.

A different pattern emerges for a second category which includes Economics and Business Administration and Law and Public Administration students. With these students, we see that several personality domains have meaningful relationships with discipline selection (Model 1). For these disciplines, both Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy also have significant relationships with discipline selection (Model 4). Unlike with the other disciplines, both civic constructs retain their meaningful relationship when personality is included (Model 5). In Law and Public Administration, the coefficients associated with personality attenuate slightly but remain statistically significant ; for students in Economics and Business Administration, coefficients associated with personality completely attenuate, leaving the only significant relationships between those with Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy

. This last finding suggests that for Economics and Business Administration students, personality is only associated with choice of discipline insofar as personality covaries with Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy.

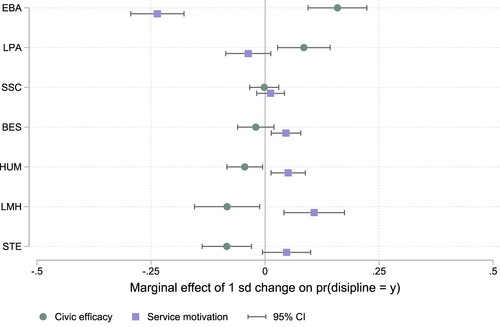

Finally, presents the results from Model 5, illustrating the average marginal effect of each of the civic constructs in a standard deviation metric. For example, it shows that, all else remaining equal, students with a score of one standard deviation above the mean level of Service Motivation have an approximately 25% lower probability of enrolling in an Economics and Business Administration degree programme than students with a mean level of Service Motivation. The same difference would increase the probability of a student enrolling in a Life Sciences, Medicine, and Health degree programme by approximately 13%. shows that, although generally correlated, Civic Efficacy and Service Motivation have marginal effects that pull in different directions.

Figure 3. Estimated Marginal effect of Civic Efficacy and Service Motivation. Note. Estimates are average marginal effects of one-unit change. Labels are as follows: EBA: Economics and Business Administration; LPA: Law and Public Administration; SSC: Social Sciences; BES: Behavioural and Educational Sciences; HUM: Humanities; STE: Science and Technology; LMH: Life Sciences, Medicine and Health.

Discussion

This paper brings research on the distribution of different personality traits across disciplines and civic-mindedness into conversation. We used survey data from more than 1,500 undergraduate students entering undergraduate programmes at a large, Dutch university in fall of 2021 to estimate a CFA measuring personality traits from the five-factor model of personality, Service Motivation, and Civic Efficacy. We found that distributions of personality domains from the Five-Factor Model are largely in line with previous research. We also found that Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy are distributed differently across disciplines and have differential marginal effects on discipline selection.

Civic-mindedness is not uniformly distributed across disciplines

Consistent with previous research, the results from this sample show disciplinary differences in personality domains. The estimates from this sample are qualitatively similar to trends found in previous research, specifically that Humanities students have higher levels of Neuroticism; Economics and Business Administration students have higher levels of Extraversion relative to Natural Sciences and Medicine students; and Humanities students have higher levels of Openness to new experience, with Economics and Business Administration students having lower levels.

What has not been previously documented in the literature are differences across disciplines related to civic constructs. Students enrolling in Economics and Business Administration have the lowest levels of Service Motivation. The higher end of the distribution, however, shows more surprising results. Students in the Humanities have a mean of approximately .4 standard deviations higher than average, whereas students in the Life Sciences, Medicine, and Health are less than half that.

Students enrolling in Economics and Business Administration stand out in almost every analysis conducted. They have the lowest level of Service Motivation of any discipline and are below the average level of Civic Efficacy. It is the only discipline where the civic constructs remain statistically significant, to the exclusion of personality traits, and the average marginal effect of both civic constructs is most extreme among all of the disciplines.

Being mindful of these distributions can help inform both the content and design of educational experiences aimed at supporting changing civic-mindedness outcomes. As noted in previous research (Van Matre et al. Citation2022), while Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy are related to personality, they are clearly differently constructs. This gives hope that while personality is by definition traitlike, Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy are likely more amenable to educational interventions. For example, while self-efficacy and civic-efficacy are distinct constructs, we may look at the more developed self-efficacy research for parallels and inspiration in civic course design. Prior research has shown that highly structured curricula can lead to higher levels of self-efficacy for students (Marczuk Citation2022) which in turn can lead to a wide variety of positive educational outcomes (Bartimote-Aufflick et al. Citation2016). Armed with this knowledge, a faculty member designing a service-learning course for Science and Technology—which has lower than average levels of initial civic-efficacy—may integrate clear performance expectations and additional scaffolding for projects into the curriculum to support these students.

Service motivation and civic efficacy have competing marginal effects on discipline selection

The differences across disciplines in both personality domains and civic constructs do not lead to a single trend in terms of how personality and civic attitudes affect students’ propensities to enter a particular major. For students in most disciplines, civic attitudes play little role in their propensity to enrol in their discipline of choice when accounting for personality. However, for some students, especially those in Economics and Business Administration, civic attitudes have relationships with discipline selection that are not only stronger than personality attributes but also robust to and attenuate the relationship between personality and discipline.

The relationship between the effects of Civic Efficacy and Service Motivation across disciplines is also important. illustrates the average marginal effect of each civic construct. This visualisation highlights two points. First, a marginal analysis of discipline selection, holding personality constant, does not line up perfectly with the observed distributions of civic attitudes. Humanities students have, on average, the highest levels of Service Motivation in any discipline. The findings from the logistic regression and , however, show that even large marginal changes (e.g. a full SD increase in Service Motivation) have a limited predicted influence with regard to Humanities, as the bulk of the variation is explained through personality.

Second, the marginal effects of Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy tend to pull in opposite directions when both are included as independent variables in the discipline selection model. Models 2 and 3 in (those that only include Service Motivation or Civic Efficacy as independent variables) show that when only one civic orientation is included, each tends to have the same sign. However, despite the higher levels of correlation between the two civic constructs, they tend to have very different relationships to discipline selection when both are included, indicating that to the extent that each construct is measuring the same thing, the marginal effects of the two constructs move in tandem. To the extent they measure distinct constructs, the two constructs pull in different directions. This oppositional relationship is important to consider in the context of the disciplines when they have the most pronounced effects. The coefficient of Service Motivation is largest for students in Economics and Business Administration and Life Sciences, Medicine, and Health. Life Sciences, Medicine, and Health is a discipline that is concerned with improving the welfare of living systems and has a strong, positive relationship between enrolment and Service Motivation. Economics and Business Administration is concerned with allocating resources under the assumption of scarcity and has a strong negative association between enrolment and Service Motivation.

The Life Sciences and Economics and Business Administration are also the disciplines where increasing levels of Civic Efficacy have the largest influence. Life Sciences, Medicine, and Health are disciplines where one learns skills that result in immediate outcomes or effects. Conversely, professional economists and administrators often cannot see the immediate results or effects of their work. These results suggest that incoming students with higher self-perceptions of efficacy (civic or otherwise) are more likely at the margin to enter fields where the efficacy of one’s work is intrinsically difficult to measure, whereas those with a lower self-perception of their own efficacy would, at the margin, enter disciplines where one can see more concrete outcomes (e.g. health and sciences).

Future research

Our findings are a first step to identify how and why different parts of the student population differ in terms of their civic-mindedness. Using the lens of the theory of vocational choice (Holland Citation1997), future research could look into the specific aspects of study programmes that do and do not align with the civic-mindedness of their students, contributing to theory-building on academic choice and civic learning.

Given the large proportion of students in medical and health-related degree programmes and the caregiving nature of that work, their relatively low levels of Service Motivation in our study are a non-obvious result. While these professions are often described as one of the ‘caring professions’ (Edwards, Caplan, and Harrison Citation1998, 2) an intrinsic desire for service may not drive these academic choices, and students may require resources to deal with interpersonal stressors and compassion fatigue that come with working in health or medical services (Showalter Citation2010; Sorenson et al. Citation2016).

Future studies can also investigate civic development of students in the field of Business and Economics, adding to the small but steady body of literature suggesting several ways in which economics students (and the broader economics profession) are different. Various studies have claimed that economics students are more selfish, more likely to engage in corruption, and less likely to be cooperative in social games and more likely to adopt libertarian policy stances than other students (e.g. Carter and Irons Citation1991; B. Frank and Schulze Citation2000; R. H. Frank, Gilovich, and Regan Citation1993; Frey and Meier Citation2005; Hammock, Routon, and Walker Citation2016). Of the two potential explanations of these differences, selection effects (i.e. more selfish people choosing to enter economics) and socialisation effects (i.e. training in economics leading to more selfish behaviour), most research has concluded that selection into the discipline is the primary driver of differences (Cipriani, Lubian, and Zago Citation2009; B. Frank and Schulze Citation2000; Frey and Meier Citation2003, Citation2005). The findings in this study suggest a theory of the underlying social constructs that could drive those differences, namely, that it is their relative lack of Service Motivation that influences their choice of Economics and Business Administration.

Limitations

This research has several limitations including, as noted in a previous section, potential nonresponse bias. Dutch survey response rates tend to be lower than in other national contexts; the Netherlands often has lower-than-average response rates in social surveys relative to their European peers, and when they do reach higher levels, it is often based on repeated, in-person, or phone contacts (Couper and De Leeuw Citation2003; Stoop Citation2005). The Dutch National Student Survey (NSE) provides a useful comparison for this study’s response rate. Conducted annually via both web and mail instruments, the NSE receives administrative support from the state and all participating Dutch universities, has a window of more than 100 days, and last used approximately €13,000 for participant incentives. Despite this institutional effort, the most recent accountability report indicates that the 2019 survey resulted in a response rate of 29.9% (Studiekeuze123 Citation2019).

Responses from students in Economics and Business Administration are lower than their relative frequency in the incoming cohort (22.9% and 26.2%, respectively). The finding that students in Economics and Business Administration have the lowest response rates is consistent with the finding that the same students lower average scores on Service Motivation and Civic Mindedness measures. If one assumes a positive correlation between Service Motivation or Civic Efficacy and responding to the survey, selective nonresponse would indicate that the true mean in either civic construct is likely to be even lower, as the students that did respond will be the most civically-minded among them. This would tend to attenuate gaps, making the estimates reported here a lower bound to the true differences between disciplines. Table A3 in the Appendix provides a complete list of disciplinary response rates.

A second potential limitation is that of unobserved variable bias in the regression analysis. Given that the purpose of this survey was primarily for individual counselling related to academic advising, demographic data were not collected. The purpose of additional control variables would be to either increase predictive value or to attempt to establish causality. The estimates presented here cannot be interpreted as causal impacts; the empirical design of this research could not support causal inferences with even the most complete set of demographic data. Adding demographic variables would increase the explained variance of the model, but would mask the unconditional correlations between personality, Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy. The models presented in this paper are, nevertheless, intrinsically relevant as the underlying constructs of civic-mindedness and personality are of interest to educators, educational researchers and education policy makers. This is especially true for practitioners who want to create tailored civic coursework within different fields of study.

Conclusion

Increasingly, universities are articulating civic-mindedness as an important outcome of undergraduate education. We estimated discipline-specific distributions of Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy, which can provide a starting point for faculty whose civic education models are aimed at populations with specific baseline levels of civic-mindedness. We also estimated how personality, Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy are related to students’ selections of discipline. We found that models that include Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy explained more variation in discipline choice than the model with personality. Additionally, we found that while for most disciplines, the effects of these civic constructs were small, they had large effects in some disciplines, notable Economics and Business Administration. Service Motivation and Civic Efficacy have competing and oppositional marginal effects on enrolment in these fields of study. These findings can inform university faculty in their efforts to implement and improve the civic educational experience and can help the field refine the role civic-mindedness plays in undergraduates’ behaviour.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joseph Charles Van Matre

Joseph Charles Van Matre is a doctoral candidate at the Centre for Philanthropic Studies at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. His research focuses on the social and civic development of adolescents and young adults in educational contexts and higher education policy. Twitter: @JosephVanMatre.

René Bekkers

René Bekkers is Professor of Philanthropy and the director of the Centre for Philanthropic Studies at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. His research combines surveys, experiments and administrative data to study causes and consequences of philanthropy. Twitter: @renebekkers.

Mariëtte Huizinga

Mariëtte Huizinga is Associate Professor at the Department of Educational and Family Sciences, and member of the LEARN! Institute at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Her research focuses on individual development of executive functions in relation to school performance.

Arjen de Wit

Arjen de Wit is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. He studies philanthropic giving, nonprofit revenues, volunteering, and student engagement in different contexts. Twitter: @arjen_dewit.

References

- Bainbridge, T. F., S. G. Ludeke, and L. D. Smillie. 2022. “Evaluating the Big Five as an Organizing Framework for Commonly Used Psychological Trait Scales.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 122 (4): 749–777. doi:10.1037/pspp0000395.

- Bartimote-Aufflick, K., A. Bridgeman, R. Walker, M. Sharma, and L. Smith. 2016. “The Study, Evaluation, and Improvement of University Student Self-Efficacy.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (11): 1918–1942. doi:10.1080/03075079.2014.999319.

- Bringle, R. G., and E. Wall. 2020. “Civic-Minded Graduate: Additional Evidence.” Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning 26 (1), doi:10.3998/mjcsloa.3239521.0026.101.

- Carter, J. R., and M. D. Irons. 1991. “Are Economists Different, and If So, Why?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 5 (2): 171–177. doi:10.1257/jep.5.2.171.

- Cipriani, G. P., D. Lubian, and A. Zago. 2009. “Natural Born Economists?” Journal of Economic Psychology 30 (3): 455–468. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2008.10.001.

- Clariana, M. 2013. “Personalidad, Procrastinación y Conducta Deshonesta en Alumnado de distintos Grados Universitarios.” Electronic Journal of Research in Education Psychology 11 (30): 451–472. doi:10.14204/ejrep.30.13030.

- Colby, A., C. P. A. Colby, E. Beaumont, T. Ehrlich, J. Stephens, and A. P. of P. S. E Beaumont. 2003. Educating Citizens: Preparing America’s Undergraduates for Lives of Moral and Civic Responsibility. John Wiley & Sons.

- Couper, M. P., and E. D. De Leeuw. 2003. “Nonresponse in Cross-Cultural and Cross-National Surveys.” In Cross-cultural Survey Methods, edited by J. Harkness, F. van de Vijver, and P. Mohler, 157–177. Wiley.

- Data Archiving and Networked Services. 2015. NARCIS classification: Classification codes of the scientific portal NARCIS. Data Archiving and Networked Services. https://www.narcis.nl/content/pdf/classification_en.pdf.

- De Fruyt, F., and I. Mervielde. 1997. “The Five-Factor Model of Personality and Holland’s RIASEC Interest Types.” Personality and Individual Differences 23 (1): 87–103. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00004-4.

- Denissen, J. J. A., R. Geenen, C. J. Soto, O. P. John, and M. A. G. van Aken. 2020. “The Big Five Inventory–2: Replication of Psychometric Properties in a Dutch Adaptation and First Evidence for the Discriminant Predictive Validity of the Facet Scales.” Journal of Personality Assessment 102 (3): 309–324. doi:10.1080/00223891.2018.1539004.

- Dungy, G. 2012. “Connecting and Collaborating to Further the Intellectual, Civic, and Moral Purposes of Higher Education.” Journal of College and Character 13 (3): 3. doi:10.1515/jcc-2012-1917.

- Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency. Eurydice. 2018. The European Higher Education Area in 2018: Bologna Process Implementation Report. Brussels: Publications Office.

- Edwards, J. R., R. D. Caplan, and R. V. Harrison. 1998. “Person-Enviornment Fit Theory: Conceptual Foundations, Emperical Evidence, and Directions for Future Research.” In Theories of Organizational Stress, edited by C. L. Cooper, 28–67. London, New York: Oxford University Press. https://public.kenan-flagler.unc.edu/faculty/edwardsj/edwardsetal1998.pdf.

- Elchardus, M., and B. Spruyt. 2009. “The Culture of Academic Disciplines and the Sociopolitical Attitudes of Students: A Test of Selection and Socialization Effects.” Social Science Quarterly 90 (2): 446–460. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00626.x.

- Frank, R. H., T. Gilovich, and D. T. Regan. 1993. “Does Studying Economics Inhibit Cooperation?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 7 (2): 50. doi:10.1257/jep.7.2.159.

- Frank, B., and G. G. Schulze. 2000. “Does Economics Make Citizens Corrupt?” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 43 (1): 101–113. doi:10.1016/S0167-2681(00)00111-6.

- Frey, B. S., and S. Meier. 2003. “Are Political Economists Selfish and Indoctrinated? Evidence from a Natural Experiment.” Economic Inquiry 41 (3): 448–462. doi:10.1093/ei/cbg020.

- Frey, B. S., and S. Meier. 2005. “Selfish and Indoctrinated Economists?” European Journal of Law and Economics 19 (7): 165–171. doi:10.1007/s10657-005-5425-8.

- Gatzka, T., and B. Hell. 2018. “Openness and Postsecondary Academic Performance: A Meta-Analysis of Facet-, Aspect-, and Dimension-Level Correlations.” Journal of Educational Psychology 110 (3): 355–377. doi:10.1037/edu0000194.

- Hammock, M. R., P. W. Routon, and J. K. Walker. 2016. “The Opinions of Economics Majors Before and after Learning Economics.” The Journal of Economic Education 47 (1): 76–83. doi:10.1080/00220485.2015.1106927.

- Heine, F., A. van Witteloostuijn, and T.-M. Wang. 2022. “Self-Sacrifice for the Common Good Under Risk and Competition: An Experimental Examination of the Impact of Public Service Motivation in a Volunteer’s Dilemma Game.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 32 (1): 217–232. doi:10.1093/jopart/muab017.

- Holland, J. L. 1959. “A Theory of Vocational Choice.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 6 (1): 35–45. doi:10.1037/h0040767.

- Holland, J. L. 1997. Making Vocational Choices: A Theory of Vocational Personalities and Work Environments. 3rd ed. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Hu, L., and P. M. Bentler. 1999. “Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus new Alternatives.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6 (1): 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Kline, P., and S. L. Lapham. 1992. “Personality and Faculty in British Universities.” Personality and Individual Differences 13 (7): 855–857. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(92)90061-S.

- Krčmářová, J. 2011. “The Third Mission of Higher Education Institutions: Conceptual Framework and Application in the Czech Republic.” European Journal of Higher Education 1 (4): 315–331. doi:10.1080/21568235.2012.662835.

- Lievens, F., P. Coetsier, F. De Fruyt, and J. De Maeseneer. 2002. “Medical Students’ Personality Characteristics and Academic Performance: A Five-Factor Model Perspective.” Medical Education 36 (11): 1050–1056. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01328.x.

- Long, M. C., D. Goldhaber, and N. Huntington-Klein. 2015. “Do Completed College Majors Respond to Changes in Wages?” Economics of Education Review 49: 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.07.007.

- Lounsbury, J. W., R. M. Smith, J. J. Levy, F. T. Leong, and L. W. Gibson. 2009. “Personality Characteristics of Business Majors as Defined by the Big Five and Narrow Personality Traits.” Journal of Education for Business 4 (84): 200–205. doi:10.3200/JOEB.84.4.200-205.

- Marczuk, A. 2022. “Is it all About Individual Effort? The Effect of Study Conditions on Student Dropout Intention.” European Journal of Higher Education, 1–27. doi:10.1080/21568235.2022.2080729.

- Marhl, M., and A. Pausits. 2011. “Third Mission Indicators for new Ranking Methodologies.” Evaluation in Higher Education 5 (1): 43–64. doi:10.15393/j5.art.2013.1949.

- McCowan, T. 2014. “Democratic Citizenship in the University Curriculum: Three Initiatives in England.” In Civic Pedagogies in Higher Education: Teaching for Democracy in Europe, Canada and the USA, edited by J. Laker, C. Naval, and K. Mrnjaus, 81–101. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McIlrath, L., P. Aramburuzabala, and H. Opazo. 2019. “Europe Engage: Developing a Culture of Civic Engagement Through Service Learning Within Higher Education in Europe.” In Embedding Service Learning in European Higher Education, edited by L. McIlrath, P. Aramburuzabala, and H. Opazo, 69–80. New York: Routledge.

- Meyer, M., M. Neumayr, and P. Rameder. 2019. “Students’ Community Service: Self-Selection and the Effects of Participation.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 48 (6): 1162–1185. doi:10.1177/0899764019848492.

- Montesinos, P., J. M. Carot, J. Martinez, and F. Mora. 2008. “Third Mission Ranking for World Class Universities: Beyond Teaching and Research.” Higher Education in Europe 33 (2–3): 259–271. doi:10.1080/03797720802254072.

- Morgan, S. L., D. Gelbgiser, and K. A. Weeden. 2013. “Feeding the Pipeline: Gender, Occupational Plans, and College Major Selection.” Social Science Research 42 (4): 989–1005. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.03.008.

- Munniksma, A., A. B. Dijkstra, I. van der Veen, G. Ledoux, H. van de Verfhorst, and G. ten Dam. 2017. Burgerschap in het voortgezet onderwijs: Nederland in vergelijkend perspectief. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Nauta, M. M. 2010. “The Development, Evolution, and Status of Holland’s Theory of Vocational Personalities: Reflections and Future Directions for Counseling Psychology.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 57 (1): 11–22. doi:10.1037/a0018213.

- Orrenius, P. M., and M. Zavodny. 2015. “Does Immigration Affect Whether US Natives Major in Science and Engineering?” Journal of Labor Economics 33 (S1): S79–S108. doi:10.1086/676660.

- Patnaik, A., M. Wiswall, and B. Zafar. 2021. “College Majors.” In The Routledge Handbook of the Economics of Education, edited by B.P. McCall, 415–457. New York: Routledge.

- Pausits, A. 2015. “The Knowledge Society and Diversification of Higher Education: From the Social Contract to the Mission of Universities.” In The European Higher Education Area: Between Critical Reflections and Future Policies, edited by A. Curaj, L. Matei, R. Pricopie, J. Salmi, and P. Scott, 267–284. New York: Springer International Publishing.

- Perry, J. L., and L. R. Wise. 1990. “The Motivational Bases of Public Service.” Public Administration Review 50 (3): 367. doi:10.2307/976618.

- Pinheiro, R., P. V. Langa, and A. Pausits. 2015. “The Institutionalization of Universities’ Third Mission: Introduction to the Special Issue.” European Journal of Higher Education 5 (3): 227–232. doi:10.1080/21568235.2015.1044551.

- Porter, S. R., and P. D. Umbach. 2006. “College Major Choice: An Analysis of Person–Environment Fit.” Research in Higher Education 47 (4): 429–449. doi:10.1007/s11162-005-9002-3.

- Riegle-Crumb, C., B. King, E. Grodsky, and C. Muller. 2012. “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same? Prior Achievement Fails to Explain Gender Inequality in Entry Into STEM College Majors Over Time.” American Educational Research Journal 49 (6): 1048–1073. doi:10.3102/0002831211435229.

- Riegle-Crumb, C., S. B. Kyte, and K. Morton. 2018. “Gender and Racial/Ethnic Differences in Educational Outcomes: Examining Patterns, Explanations, and New Directions for Research.” In Handbook of the Sociology of Education in the 21st Century, edited by B. Schneider, 131–152. New York: Springer International Publishing.

- Rocconi, L. M., X. Liu, and G. R. Pike. 2020. “The Impact of Person-Environment fit on Grades, Perceived Gains, and Satisfaction: An Application of Holland’s Theory.” Higher Education 80 (5): 857–874. doi:10.1007/s10734-020-00519-0.

- Shi, D., T. Lee, and A. Maydeu-Olivares. 2019. “Understanding the Model Size Effect on SEM fit Indices.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 79 (2): 310–334. doi:10.1177/0013164418783530.

- Showalter, S. E. 2010. “Compassion Fatigue: What is it? Why Does it Matter? Recognizing the Symptoms, Acknowledging the Impact, Developing the Tools to Prevent Compassion Fatigue, and Strengthen the Professional Already Suffering from the Effects.” American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine 27 (4): 239–242. doi:10.1177/1049909109354096.

- Sörbom, Dag. 1989. “Model modification.” Psychometrika 54 (3): 371–384. doi:10.1007/BF02294623.

- Sorenson, C., B. Bolick, K. Wright, and R. Hamilton. 2016. “Understanding Compassion Fatigue in Healthcare Providers: A Review of Current Literature.” Journal of Nursing Scholarship 48 (5): 456–465. doi:10.1111/jnu.12229.

- Sotelino-Losada, A., E. Arbués-Radigales, L. García-Docampo, and J. L. González-Geraldo. 2021. Service-Learning in Europe. Dimensions and Understanding From Academic Publication. Frontiers in Education, 6. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389feduc.2021.604825.

- Soto, C. J., and O. P. John. 2017. “The Next big Five Inventory (BFI-2): Developing and Assessing a Hierarchical Model with 15 Facets to Enhance Bandwidth, Fidelity, and Predictive Power.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 113 (1): 117–143. doi:10.1037/pspp0000096.

- Steinberg, K. S., J. A. Hatcher, and R. G. Bringle. 2011. “Civic-Minded Graduate: A North Star.” Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning 18 (1): 19–33.

- Stoop, I. A. L. 2005. The Hunt for the Last Respondent: Nonresponse in Sample Surveys. The Hague: Social and Cultural Planning Office of the Netherlands.

- Studiekeuze123. 2019. Onderzoeksverantwoording Nationale Studenten Enquête 2021. .: Studiekeuze123.

- Tijsma, G., F. Hilverda, A. Scheffelaar, S. Alders, L. Schoonmade, N. Blignaut, and M. Zweekhorst. 2020. “Becoming Productive 21st Century Citizens: A Systematic Review Uncovering Design Principles for Integrating Community Service Learning Into Higher Education Courses.” Educational Research 62 (4): 390–413. doi:10.1080/00131881.2020.1836987.

- Van der Meer, T., and E. Van Ingen. 2009. “Schools of Democracy? Disentangling the Relationship between Civic Participation and Political Action in 17 European Countries.” European Journal of Political Research 48 (2): 281–308. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00836.x.

- Van Matre, J. C., R. Bekkers, M. Huizinga, and A. de Wit. 2022. Civic-mindedness is more than personality: Untangling the overlapping constructs of service motivation, civic efficacy and the Big Five. PsyArXiv.

- Vedel, A. 2016. “Big Five Personality Group Differences Across Academic Majors: A Systematic Review.” Personality and Individual Differences 92: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.12.011.

- Vedel, A., D. K. Thomsen, and L. Larsen. 2015. “Personality, Academic Majors and Performance: Revealing Complex Patterns.” Personality and Individual Differences 85: 69–76. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.04.030.

- Weber, P. S., J. E. Weber, B. R. Sleeper, and K. L. Schneider. 2004. “Self-efficacy Toward Service, Civic Participation and the Business Student: Scale Development and Validation.” Journal of Business Ethics 49 (4): 359–369. doi:10.1023/B:BUSI.0000020881.58352.ab.

- West, S. G., A. B. Taylor, and W. Wu. 2014. “Model fit and Model Selection in Structural Equation Modeling.” In Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling, edited by R. H. Hoyle, 209–232. New York: Guilford Press.

- Xu, Y. J. 2013. “Career Outcomes of STEM and Non-STEM College Graduates: Persistence in Majored-Field and Influential Factors in Career Choices.” Research in Higher Education 54 (3): 349–382. doi:10.1007/s11162-012-9275-2.