ABSTRACT

This paper explores the confluence of art, play and places, presenting three case studies enacted via participatory art projects which asked: How can artistic play change our relationship to place? The research was practice-based via participatory art and presents new, ludic cultural practices in regards to art, play and place. The case studies discuss how participants became liberated from normal adult behaviour in public spaces because of the alibi of art and play, as well as enjoying and interacting with the place differently. The artworks were contextually responsive to the specificities of each place, allowing players an opportunity to develop new, positive place-relationships. It also includes a reflection on the political imperatives of play in assisting adults imagining new futures for themselves. The findings of this paper are useful to those involved in heritage or cultural projects seeking to develop new audience relationships with their specific places.

HIGHLIGHTS

Adult play can be considered a ‘rebel base for imagination’ that helps with audience development for heritage/cultural projects.

Framing ‘play’ as an ‘artistic process’ encourages deeper engagement from adults, and this more effective engagement with place.

Conflict-based play approaches allows the politics of plurality and dissensus to occur and as such, is more age-appropriate for adults because such work involves complex themes responding to specific localities.

Play gives an opportunity for adults to ‘rehearse our future’ in regards to politics, culture and place, enabling capacity to explore meaning within our lives

1. Introduction

On a hot summer’s day in Finland in 2018, on an island off the coast of Helsinki, groups of adults were hiding in the dense undergrowth. The adults – all between 20 and 50 years old – were divided into two groups, half were dressed in blue and half in red. All were smiling, and some stifled a laugh, trying to remain hidden beneath the ferns. This joyful moment seemed discordant with the site because the island – Vallisaari – is a former military base, long abandoned with shoots of trees reaching up through the decaying barracks and munitions stores and the place holds difficult cultural memories relating to the Russian and Swedish rule of Finland.

This paper explores the conditions that led to the juxtaposition of adults playing among the ruins of a former military base and does so via the case of Vallisaari above as well as two other contexts. It proposes that (participatory) artistic approaches can provide the potential to transform sites into playable spaces for adults in a way that can have political ramifications.

This paper begins with our methodological framing, and explores our participatory art methods; it then presents a brief exploration of our understandings of both ‘place’ as well as the intersection of art and play; and then moves on to describe our three case studies and the findings from them. It concludes with a discussion about the political ramifications of adult play.

2. Methodology framing: an epistemology of affect

Three distinct opportunities organically emerged for the authors which could offer significant data about play, place and art, and these opportunities also aligned with our general artistic approach that uses creative methods to explore a shared interest in the intersection of art, space and adult play.

Play can be important in allowing adults to perceive, and to interact with, the world differently, with the concept of the ‘magic circle’ (Huizinga, Citation1955) often used as a shortcut for how a place and people are changed when we play, allowing different rules to apply compared to normal life. Playing as adults allows a ‘diminished consciousness of self’ (Brown & Vaughan, Citation2010, p. 17), which allows us to improvise in ways we might otherwise struggle with, and to inhabit roles that have different points of view to our normal lives. In these ways, play enables adults to construct new understandings of spaces, ourselves, and others.

The authors’ methodological expertise lies within artistic practice and our insights emerge from the doing of this work. The work takes an ontological position based in Constructivism, which is the understanding that objective truth does not exist, but it is consistently assembled through the study of diverse interpretations of meaning (Hugly & Sayward, Citation1987). Indeed, the works included below are couched in the understanding that space, place and meaning are all socially constructed, subjective, interrelated, and malleable, and can provide deeper understandings of the creative and social potential of spaces. We therefore used our artistic practice research to elicit insight into these ‘place relationships’. In this way, we explored new understandings through play, rather than about play.

Our arts-based methodologies have been applied to uncover tacit and affective cultural insights (Sullivan, Citation2010; Nelson, Citation2013). Often, the critique of such research strategies is that it ‘lack rigour and systematic inquiry’ (Nelson, Citation2013) but whilst rigour and systematisation might be important within an empiricist or rationalist paradigm, artistic research and its insights are not couched in such epistemologies. As Sullivan suggests: ‘To continue to borrow research methods from other fields denies the intellectual maturity of art practice as a plausible basis for raising significant life questions and as a viable site for exploring important cultural and educational ideas.’ (Citation2010) Indeed, artistic work functions best when it is disruptive and unique; when it provides frameworks to ‘think difference’; when it is surprising; when it ‘transforms understanding’ (Sullivan, Citation2010). As such, the work we present does not replicate existing traditional humanities research paradigms but rather intrinsically values the ways in which artistic works can provide affective insights which ‘new solutions visible’ evident and emotionally accessible. (Jokela, Citation2019) The aim for the research included in this paper therefore is to support the conjecture that particular artistic interventions (i.e. participatory art) can transform places into more ‘playable’ spaces for adults via an affective, artistic experience.

3. Methods: participatory art and conflict

Participatory art is a genre of art making that is framed around the engagement of groups and/or individuals. The work is often referred to as Socially Engaged Practice and is defined as ‘any artform which involves people and communities in debate, collaboration or social interaction.’ (Tate. n.d) Within the genre of participatory art, a produced ‘artwork’ (i.e. an object) often holds less ‘importance to the collaborative act of creating them’ (Tate, Citationn.d.). Within this work social activities and events are framed as artistic processes and it is this collective meaning-making that lies at the core of Participatory art. Additionally, Stott (Citation2017) argues that ludic participation produces and organises complexity, and Jokela (Citation2019) also suggests that participatory acts evokes emotions directly within participants.

Historically, there is an extensive legacy of participatory art projects utilising play as a method (Skovbjerg, Citation2018). For example, Tine Bech applies play as a method within her participatory design projects to create ‘public art, light art, interactive installations, sculptures and games, which connect people for shared moments of discovery and wonder’ (Bech, Citationn.d.). In research contexts, the Participatory Urban Design projects considers the ‘materiality and sociability of urban space as starting points for play’ (Lundman, Citation2019). Festivals such as CounterPlay and the Playful Art Festival are both designed with a participatory approach in order to examine play’s context in a wider social context. Dönmez (Citation2017) argues that utilising art as a form of play challenges participants to think beyond ‘everyday existence,’ if they are able to surrender to its particular rules (p. 174).

Zimna (Citation2010) sees the application of play within a participatory art context as understandable as both are overlapping spheres operating as tools ‘of transgression and an ‘attractive supplement’ of the creative process – a way to activate the public and change the traditional [function] of art.’ (Zimna, Citation2010, p. 5) Relatedly, Schrag (Citation2016) explores how play and participation can manifest in community contexts not just via visual representation, but via physical actions and suggests that physical methodologies such as embodied games (racing, hiding, sports-based activities) are a highly effective mechanism for participatory arts (p.217).

There are, however, assumptions about ‘participatory art’ that we aimed to problematise and address via the application of ‘conflict’ within the works. Generally, theorists such as Kester (Citation2004) or Matarasso (Citation2012) situate participatory art activities along the legacy of Community Art with ‘negotiated dialogue’, amelioration and agreed consensus being the ultimate goal of such works. In opposition, Chantal Mouffe argues that within a pluralistic, diverse society, ‘consensus’ inevitably means certain voices are silenced in favour of a larger whole, and instead suggests that ‘a democratic society is one in which relations of conflict are sustained, not erased.’ (in Bishop, Citation2012, p. 66). Similarly, Deutsche has said: ‘Conflict, division, and instability, then, do not ruin the democratic public sphere; they are conditions of its existence’ (Deutsche, Citation1996, p. 295). Schrag (Citation2016) similarly argues for a ‘productive conflict’ (2016) and while the term ‘conflict’ can often have negative connotations, Schrag links the concept to Levinas’ suggestion that as social creatures, humans can only ever learn about themselves by engaging with others (Levinas, Citation1989). This engagement with someone different from oneself can sometimes be difficult, as it exposes one to the essential fact of another’s existence in a wider social context, and thus the essential social nature of human culture (rather than an individualised existence). These productive conflicts are therefore essential to building egalitarian social relations (Schrag, Citation2016).

So along with the participatory art approach – which involved a collective-meaning making by referencing the historical and cultural contexts of the specific locations – the work made through this project referenced childhood games such as ‘capture the flag’ or other oppositional activities where one team encounters the other in a participatory, productively conflictual manner was central to the project. In-Situ refers to this as ‘artistic acupuncture’ (Citation2018). In this way, we hoped the participants could develop new connections to these places in ways that could be captured in order to draw inferences about how adult play, place and art can productively be considered to intersect.

It should be noted that ethical procedures were established and approved via one of the author’s University, and adhered to strictly: participants were given information about the project and – if amenable – to sign consent forms which approved the use of images of them (or use of their images) within all public, published domains ().

Image 1. Right: Players with a captured flag, showing the excitement of success: they are rushing towards their own island and Micronation with their pillage (the opposite team’s flag), choosing the route carefully in order to avoid ambush from the opposite team. Top left: Participants having a joyful time while creating their Micronations. During the Micronation creation process we could hear a lot of laughter in the boat shed where this part of the play took place, where participants unleashed their imagination. Bottom left: Map of islands Vallisaari and Kuninkaansaari. Detached from traditional map colours and tinted into pink and purple started the process of shifting the participants’ thoughts from ordinary to imaginary. Photos: Ilkka Nissilä, 2018.

Image 2. Left: The Board Game in mid-play: the outsiders and the insiders are changing both the sides and the tasks. Participants took this part seriously in the beginning and then as the play evolved started to relax and laugh as the purpose of their play was step by step revealed to them. Top right: Expected adult behaviour in a place followed bottom right: ‘Playful interaction with a place’. The expressive movement and fun is evident from the documentation. Video: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8256560 Images and screenshot, Nina Luostarinen, 2019.

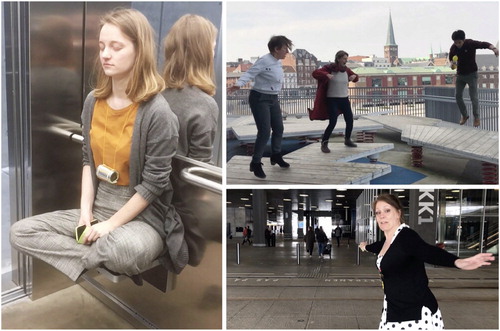

Image 3. Left: Meditating/levitating in a moving elevator. Using imagination and a playful attitude, a foldable bench in an elevator combined with the moment of the lift gives a perfect illusion of levitation. Video: 10.6084/m9.figshare.8256539. Top right: Playing with the place outside Dokk. This is a place dedicated for playing, but normally occupied by children. Screenshot from a video by a participant, 2019. Video: 10.6084/m9.figshare.8256554. Bottom right: Taking the role of a tightrope walker and imagining that rail tracks are a rope to dance and sing upon was performed with an irreverent attitude. Video: 10.6084/m9.figshare.8256545. All videos by participants, 2019.

4. Place attachment: the potentialities of places

The authors interested in play and art related to the creative and social potential of specific locations. We were interested in how to enhance ‘place attachment’ via artistic projects, exploring if artistic projects could alter a participant’s perception of a space/place. Below we briefly describe our understanding of ‘place’.

The distinction between the plethora of geological terms (place, space, site, location etc.) is nuanced and complex. Agnew’s Space and Place (Citation2011) provides a good contextualisation that place invariably cannot be separated from its socio-political connotations, whereas a space is a tangible locus emerging from the work of philosophers, cartographers, scientists (Agnew, Citation2011). As such, the places we explore are always thought of in relation to people’s lived experiences of the site.

How meaning emerges from places – in modernist, western traditions – has often been traced to Thoreau who extolled a pastoral life where man and nature were woven together in pastoral idyls; the rural was a place to ‘live deliberately’ (1854) and, in his understanding, the ideal location was necessarily natural, and meanings of such loci was transcendental. In contemporary studies, understandings of place are more nuanced: Mesch & Manor describe place attachments as a positive emotional bond that develops between individuals or groups and any environment (Citation1998). Forss suggests that due to the socio-political construction of places, they cannot be separated from emotions (Citation2007). Thus, an overall experience of place does not have to be a specific location, but rather loci that elicit emotional connection and ‘place’ will always be said to contain emotional attachments. Hidalgo and Hernández (Citation2001) define place attachment as a connection and emotional involvement between a person and a specific place. Altman & Low explain that emotional interaction with a place can lead to an attachment to that place, and positive emotions can create positive satisfaction and attachment (Citation1992) or emotional engagement with spaces (Russell, Citation2013). Place attachment therefore is founded upon emotional interaction with specific geographic locus, and we were interested in exploring if and how participatory art projects could adjust/enhance/change an emotional interaction of a place via specific interventions. For example, could making a place more ‘playable’ via a participatory art activity affect or alter a person’s place attachment. And what might this playable place attachment mean for such a site?

Some work has already explored the intersection of play and place: Päivi Granö (Citation2004) stating that a concept of the playground is formed by the relationship between play and space and these play locations create and carry meaning, including later on, as emotional memories. Similarly, ‘playing’ in a location operates as a sort of ‘mapping’ of a place which enables encounters with space, place and culture to stimulate flow, ingenuity and creativity, (Playful Mapping Collective, Citation2016). In this way, playing in places attaches the player to the site and there is similarly good research that explores the benefits of play within an urban context via smart technology (Innocent, Citation2020 and Nijholt, Citation2015) both of whom recognise this play is limited by the availability of smart technology integrated into the city environment (Nijholt, Citation2015, p. 2176). Both suggest that enhancing the playable qualities cities can transform them from urban spaces into places (Innocent, Citation2020). As this is possible within wider city-wide frameworks, could this playability also operate on a micro-scale, with specific locations? If so, this might have a significant impact on how individual places might engage differently with their audiences.

5. Rehearsing for the future: the potentialities of play

Curiously, theorists perhaps tacitly agree that play already acknowledges notions of ‘place’ within it: the fact that play is the space where ‘the edges of normal reality are broken … ’ (Riikonen, Citation2013, p. 181 – emphasis added); Or, that play has its own identifiable world and structure which also has a defined time and place; (Hänninen, Citation2003, pp. 12–13 – emphasis added); Or, recognise that play acts as a ‘boundary crosser’ (Hyde, Citation1998; Zimna, Citation2010). Lakoff and Johnson (Citation2003) argue that paying close attention to linguistic metaphors can give insight into embedded knowledges and understandings of subjects. Thus, reflecting on the common reoccurrence of such linguistic metaphors that link place (boundaries, edges, defined time and place, and imagined worlds etc.) to play reveals an existing link between these subjects. While this link may be tangential, it does provide a useful segue to discuss how the authors understand play and its potential in regards to creative and social potential.

In the cases below we were not interested in recreating ‘childhood’ play for adults, but rather developing an age-appropriate play that might align with an adult’s complexity of emotional life and social expectations. Katriina Heljakka’s doctoral thesis (Citation2013, p. 447) she presents studies showing that artistic play has positive effects on well-being for adults and adults should have the right to give themselves up to playing and to use playthings as part of their work and leisure without feeling guilty, but that guilt is a key factor in limiting adult play. Indeed, along with guilt, there are other factors including embarrassment, (fear of being labelled immature); being non-productive members of society; being irresponsible, etc., all acting as blocks to adult play (Citation2013). Similarly, Deterding suggested adults are often ‘expected to competently and appropriately enact their social roles’ and ‘to be an adult is to not be in need of play anymore’ (Citation2018). Despite the fact that adult play is not commonly socially sanctioned, Deterding reminds us that there are indeed ‘abundant empirical instances of productive, regulated, and normabiding play’ (Citation2018) for adults, but the social constraints can often contain and counteract the benefits of adult play. There are, however, ways around these constraints by finding appropriate frames to gain permission for unabashed playfulness. The appropriate management of these frames include: providing an alibi (i.e. a code that designates and delineates that the play is socially approved, such as wearing similar outfits); managing audiences to ensure that play is viewed as approved (i.e. clearly delineating who is a player and who is not); and awareness management (i.e. providing ways to prevent being identified, such as masks or hiding). These frameworks provide ‘alternative, adult-appropriate motives to account for their play’ (Deterding, Citation2018, p. 1) and give permission for an adult to engage in playful activity. These permissions, therefore, can provide excuses to play, but the question of why an adult should play is perhaps less explored.

In our conversations with participants, Tina Bruce’s theory of Play-Based Learning was often cited. In this theory, she discusses the importance of play for children’s learning, specifically because:

‘Play transforms children because it helps them to function beyond the here and now. They can become involved in more abstract thinking about the past … and into imagining the future, or alternative ways of doing things’ (Citation2011 - emphasis added)

This begs the question whether adult play could also be a methodology to grapple with ideologies; to explore our political contexts; or examine beliefs in an embodied, curiosity – or fantasy-led manner? It is possible that when adults play they can also rehearse for a (different) future and (re)imagine playful layers of places, politics and culture in order to strengthen the unbeatable capacity to find meaning for our lives, and in the future? If so, adult play has broader significance than just within the culture and heritage sector and could be re-contextualised to examine political potentialities in other realms, for example to engage apathetic voters. While not within the scope of this paper to explore such potentialities, the authors did try to use artistic processes as permission to play in a way that allowed adults to reimagine their relationships to specific places. In the cases below, we referenced Deterding’s frameworks to mitigate embarrassment and fear etc., using the artistic activities as sanctioned permission to play, combining art and play to bring people together to imagine and reimagine our relationships to places. This is not an unheard of strategy in that ‘play is a common and effective means of bringing people together, and it is also often a condition for the kind of experimentation associated with creativity,’ and ‘participatory practice increases playful qualities.’ (Johanson & Glow, Citation2018). As a tool for permission, (participatory) art practices can raise participants beyond our everyday existence, if they are able to surrender to its particular rules (Dönmez, Citation2017, p. 174).

6. The cases three

Below we describe the three cases and their contexts, while also providing some feedback from participants.

6.1 Case 1: Vallisaari and Kuninkaansaari – A rebel base for imagination

The first case study occurred on the Islands of Vallisaari and Kuninkaansaari. They are former military bases, situated only a few kilometres from Helsinki Harbour and were integral to Finland’s history with Russia and Sweden. As places, the islands are therefore inherently linked to questions of conflict, identity and nationhood and have only recently been open to the public after being off-limits for decades.

The author’s considered Alistair Bonnett’s Off the Map: Lost Spaces, Invisible Cities, Forgotten Islands, Feral Places and What They Tell Us About the World (Citation2014). In the work’s title, Bonnett plays with the meaning of the word of (‘belonging to’) and off (‘away from’) in order to reflect on the conceptual dissonance of both belonging to and being away from a place simultaneously. In such a dissonance, Bonnett argues that sites can become a ‘rebel base for imagination’ (Citation2014) to re-imagine and rethink what a place could mean.

To explore this ‘rebel base’ we designed a game for two groups. In the first part of the game, each group developed a flag and a manifesto for their own ‘Micronation’, collaboratively exploring their political, social and cultural beliefs. The second part replicated a traditional ‘capture-the- flag’ game with each group being assigned one of the two islands to defend from the opposing team but also tasked with ‘taking over’ the opposing team. There were 20 participants, all adults and the game took 4 h in total, including a break.

The game’s aim was to explore the emotional connection to these islands by playing in sites that were linked a socio-political-historical context. While it is perhaps obvious that citizens would have develop an emotional connection to these newly accessible places that have historical and cultural significance, it is important to consider Augé’s point that often geographic locations that do not hold enough significance to be regarded as ‘places’ (Augé, Citation1992), and in such places, human beings remain anonymous and therefore cannot develop emotional connection to such spaces. As the Islands had been isolated, it was a concern they would not hold enough ‘significance’ to participants. Korstanje (Citation2015), however, critiques Augé’s position complicates the narrative of what places ‘are’ and ‘who’ gets to decide their meaning. Despite this complication, what is clear, however, is that certain sites have meaning to some and not meaning to others, and it is experiences of these places that form attachments, allowing positive satisfaction and attachment (Altman & Low, Citation1992) or productive emotional engagement with spaces (Russell, Citation2013). These are not just emotional, but can be socially formulated, too: ‘Places participate in both individual and collective identities’ (Jankowski, Citation2019).

After playing this game, we asked participants how they felt about playing this game on this site, the key responses being:

I was able to see hidden paths and look at maps differently because we needed some strategic thinking. It was a more holistic experience that way.

It gave a bit of a different experience. I saw the surroundings with different eyes.

I saw some areas/location which I would have missed as a normal visitor.

It was involving, interactive and developed team building skills. Get to enjoy the island better.

After describing the other two case studies, below, we discuss some of these findings in regards to adult play.

6.2 Case 1: GoMA – art, as an excuse

The Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA) in Glasgow, Scotland is a publicly owned building that hosts large scale exhibitions along with smaller education/outreach projects. Originally built by a prominent tobacconist and slave- trader, the building occupies a complicated spot in the contemporary Scottish cultural psyche. Most famous about the building is the equestrian statue of the Duke of Wellington that sits outside the building. The statue almost always has a large, orange traffic cone on its head, and for many years, the authorities regularly removed cones, only for them to be replaced the following day by (often inebriated) Glaswegians. The location is therefore inexorably linked to arts and culture, but also to authorities and power, and how a public engages with those authorities and power: the game we developed aimed to respond to these conditions of the place.

Like in Helsinki, the game developed was similarly arranged into two parts. The first part divided participants into ‘indoors’ and ‘outdoor’ groups with each group assigned either the inside of GoMA, or the immediate outdoor public square around the gallery and were tasked to map play actions they might do in those spaces – for example, hopping, skipping, singing, etc. They were then invited to creatively map these sites and actions. As Frosham (Citation2015) suggests, producing experimental maps can destabilise ‘long-standing assumptions about the nature of representation, knowledge, and power’. Doing this collectively as a part of playful participatory art action allowed the participants to find ‘new ways of seeing, knowing, and acting in the world’ (Citation2015). This map became the ‘game board’ for the second part of the game in which each member was given a Game Piece that resembled the equestrian statue outside GoMA – either horses or soldiers. In this way, the game began to reference the context of the location and its relationship with history and authority.

To play the Board Game, each team-member chose a single playable act that they might individually enact at an indoor or outdoor location. This act was written down onto a piece of paper that was folded and secured into the matchbox-base of their Game Pieces, and then rolled dice to move from ‘inside’ to ‘outside.’ Each team member exchanged playable acts that were linked to specific locations with at least one other person from the opposite team in a randomised way. Once the game was finished, the third and final part of the game occurred, in which each participant went to the location they had landed on, and enacted the specific playable act they had received and to document it by recording a video. For example, one participant had to run around the balcony as if it were a racetrack; someone else was tasked to mimic sculptures. The game took 2 h in total, with 12 adults.

In the informal feedback with participants after the game at GoMA, participants suggested that in framing the game as ‘art’ (rather than play) seemed to give adults an ‘alibi’ that seemed to deflect possible ‘embarrassment’ from acting in non-sanctioned ways adults normally act. This context of art to be able to reclaim and delineate significance and meaning seems to act as a mechanism to give ‘permission to play’ (Walsh, Citation2019). This elides with the above concept Johanson & Glow presented that ‘Play is a common and effective means of bringing people together, as well as linking with Deterding’s concept of providing ‘alibis’ to play. In Helsinki, the potential adult embarrassment was mitigated by visual clues such as providing coloured vests that identified the players as being intentionally engaged in sanctioned activity. In GoMA's case (and in Dokk1, below), the alibi took the form of the documentary photographer which signified the ‘documented players’ as being involved in intentional, sanctioned activity. In all three cases, these visual, identificatory clues assisted in the playful, place engagement. Further research is required into how to enhance this ‘alibi’ approach.

As with the Finnish case studies, the key response from the participants was:

It takes you away from how you usually behave [in an art gallery], which is more the point here, so leaving your own comfort zone to do something new.

There has to be priming, and the game gives a sense that it is ‘right’, because it creates that sense of: we are all playing it, we are all in this together.

The conflict is also about fun. For me to run around a balcony [in an art gallery] is more fun than if you run around a running track … but you shouldn't really run around a balcony … for me is a bit naughty! And fun.

We opened our eyes to the playful parts of our surroundings, whereas we would normally just navigate, go to the coffee place or go to the train station.

That is part of the fun as well: you make yourself a bit vulnerable. The risk is something new might happen: and that is that part of ‘rehearsing the future’.

6.3 Case 1:case 3: Dokk1 – playful strategies

Dokk1 in Aarhus, Denmark, was the venue for the 2019 CounterPlay festival, a festival that aims to bring ‘together professionals from many different domains to explore play and playfulness’ (Counterplay, Citation2019). The Dokk1 building is newly constructed designed to be ‘a distinctive hub around which life in the city revolves’ (Dokk1, Citation2019) and is a multi-purpose conference venue that also features a library, municipal services, restaurants and cafes, play areas for children and other services expected within a public space. As such, the location is inexorably linked to questions of civic activity and publicness, but also – due to the festival – notions of play.

The game designed for this followed much the same path as the one designed for GoMA mimics that process significantly in that it was designed in three phases – indoor/outdoor groups that mapped playable activity, a context-specific board game that developed out of this mapping, followed by a performance where each participant was invited to enact (and photograph/film) a playable act either indoors or outdoors. The game was played with 14 adults, and took place over 1.5 h.

Due to the context of the CounterPlay festival in which there were multiple events happening at the same time, there were insufficient opportunities to gather user feedback, and so our data for this activity is entirely couched within visual (photograph/videos) material.

7. What does this all mean, if anything?

The above cases have provided material to reflect upon questions of place, art and play. In Vallisaari, the two most significant quotes were: ‘It gave a bit of a different experience. I saw the surroundings with different eyes.’ and ‘I saw some areas/locations which I would have missed as a normal visitor.’ In both of these, the participants make a clear link between the experience of the game and the opportunity to explore the space in a new and unique way. The context of the game relating to its context assisted in making this context embedded and relevant to the visitors, but also an age-appropriate adult play experience that was sufficiently complex to engage the adult players.

In GoMA, the similarly age-appropriate, complex themes such as ‘art’, ‘public space’ and ‘power’ were explored through the game, with the relevant responses being: ‘It takes you away from how you usually behave [in an art gallery], which is more the point here, so leaving your own comfort zone to do something new.’ And ‘The conflict is also about fun. For me to run around a balcony [in an art gallery] is more fun than if you run around a running track … but you shouldn't really run around a balcony … for me is a bit naughty! And fun.’ The concept of ‘fun’ has returned often through-out this work and suggests further research needs to be done to explore how ‘fun’ – and how to elicit such responses – might be at the ‘anchor of an aesthetic of play’ (Sharp & Thomas, Citation2019). And, also: ‘We opened our eyes to the playful parts of our surroundings, whereas we would normally just navigate, go to the coffee place or go to the train station.’ Here, the participant’s engagement with the artistic sites altered due to the game, giving a more positive relationship with sites normally associated with authoritarian control. Similarly, there was an acknowledgement that the conflictual, physical approaches allowed these new relationships to occur for the adults engaged in the playful acts in ways that would not have happened without the playful intervention. Lastly, there was acknowledgment of risk and that the game recognised that this risk might be important; that playing allows adults to continue ‘rehearsing the future.’ This risk alludes to the political imperative of these sorts of activities.

In Dokk1, it could be argued that the context of The CounterPlay Festival might significantly skew results due to the high proportion of ‘players’ that might be attending the festival, however, the visual documentation does provide unique examples of alternative engagements with spaces that are possible. That these actions should occur within a municipal, public space provides opportunity for how publics can develop new relationships with public spaces, as is visible from the images above. In a time of increasing privatisation of public contexts (Nemeth & Schmidt, Citation2011), this underscores a political imperative of playing in public space and the positive engagements that municipalities could engender by welcoming such activities in that they provide citizens ownership over these places by being able to develop new positive memories (Granö, Citation2004).

Two of these art play activities occurred within urban spaces and one within a rural context, and there was no significant variance in the level of adult engagement with the game or the artistic processes. This suggests that the context is not dependent upon specific locations but could occur in plural contexts and accessible to a multitude of sites. Similarly, one occurred on a heritage site (Vallisaari), one in a traditional art context (GoMA) and the other on a public site (Dokk1). It was clear that on all sites, there was excellent take up of the offer, with positive results for the adults in developing new place relationships through the art game. This would also suggest that processes are accessible to multiple types of organisations, with a variety of access points. Indeed, in all engagements of the playful activities (whether via providing an alibi via uniforms, or disguising it as ‘art’) there seemed to be significant potential for participants to construct new collaborative understandings of places collaboratively. As Horlings suggests: ‘A shared sense of place can potentially be a call for action and result in collective care and responsibility of resources in common lands … Place is a site of collective action and co-creation between diverse actors’ (Horlings, Citation2019, p. 21). Combining this ‘collective action and co-creation between diverse actors’ with the concept of play being a way to ‘rehearsing for the future’ suggests that adults playing can have political imperatives that might have significant impact in contexts beyond the culture and heritage.

What can we interpret from feedback and documentation is that participants became liberated from normal, adult behaviour in public spaces because of the alibi of art and were able to interact with the place differently. The play was age-appropriate as it was composed of complex themes and was all contextually responsive to the specificities of each place; the conflict-based approaches allowed the politics of plurality and dissensus to occur within the participatory approach. Combined, these effects gave the players an opportunity to develop new and positive place relationships.

8. Conclusion: the (Possible) politics of play

From the above, it is possible to see that participatory artistic methods created alibis for play that encouraged adults to develop new relationships with places: these relationships provide new engagements to sites and were linked to the contextual nature of the places. As with all artistic projects, these are not models to be universally applied, but are useful examples for those working within heritage, cultural or public spaces to consider, especially if they wish to encourage publics to have new and different relationships with the places they manage and steward. The findings go beyond just those who wish to apply play methodologies for place engagement. The political imperative that emerged from the concept of ‘Rehearsing for the Future’ through play has given us significant pause in our reflection on play, place and art. In a world that has become politically partisan, playing together – collaboratively and conflictually – can provide a shared ‘call for action and result in collective care and responsibility’ (Horlings, Citation2019, p. 21). This is especially a concern for adults who have few opportunities to grapple with and explore our politics, or beliefs in an embodied, curiosity – or fantasy-led manner: we have few opportunities to rehearse for our own future, or understand how that future fits together with others’ futures. Playing reinforces our engagement with meaning-making in regards to places, politics and culture. This is not simply about how one imagines and works towards creating a better world, but also is a growing cultural imperative: robots and artificial intelligence have (as yet) no ability of to play (Johnson, Citation2017) and a world organised by such mechanisms might see no value in such frivolous actions jumping as high as you can, or running madly around an art gallery balcony or hiding in the ferns on a sunny summer day.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Andrew Walsh from The University of Huddersfield for providing editorial review and further insight about adult play.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nina Luostarinen

Nina Luostarinen has a background in puppetry, performing arts and new media content creation. She has been producer and scenographer for various cultural events and theme parks. She has also been a designer for interactive games and an animator for the national TV broadcaster in Finland. In recent years, she has been working with several EU-funded projects seeking to connect different forms of art and culture with other fields of life. She is fascinated by visual things in general and especially by the power of photography. A common thread in her work has been believing in serendipity, existence of the invisible worlds and enabling illusions. She is a Doctoral Candidate at the University of Lapland where she is researching the possibilities of art-based play in regards to place attachment.

Anthony Schrag

Anthony Schrag is an artist and researcher currently lecturing in Cultural Management at Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh. He is an associate member of the Centre for Communication, Cultural and Media Studies as well as the Centre for Person Centred Care. His practice-based PhD – completed in 2016 – explored the relationship between artists, institutions and the public, looking specifically at a productive nature of conflict within institutionally supported participatory/public art projects. Schrag is a practising artist and researcher who has worked nationally and internationally, including residencies in Iceland, USA, Canada, Pakistan, Finland, The Netherlands and South Africa, among others. He works in participatory manner, and central to his practice is a discussion about the place of art in a social context. Lecturing interests include the ethics of artists ‘working with people’, critical pedagogies and practice-based research.

References

- Agnew, J. (2011). Space and place. In J. Agnew, & D. Livingstone (Eds.), Handbook of geographical knowledge (pp. 316–330). London: Sage.

- Alistair Bonnett’s. (2014). Off the Map: Lost Spaces, Invisible Cities, Forgotten Islands, Feral Places and What They Tell Us about the world. London: Aurum Press Ltd.

- Altman, I., & Low, S. M. (1992). Place attachment. New York: Springer.

- Augé, M. (1992). Non-places introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity. London: Verso.

- Bech, T. (n.d.). Tine Bech Studio - Public Art, Installations and Exhibitions. http://www.tinebech.com/ (Accessed 12 Mar 2021)

- Bishop, C. (2012). Artificial hells: Participatory Art and the politics of spectatorship. London: Verso.

- Brown, S., & Vaughan, C. (2010). Play: How it shapes the brain, opens the imagination, and invigorates the soul. London: Avery.

- Bruce, T. (2011). Learning through play: For babies, toddlers and young children. London: Hodder Education.

- Counterplay. (n.d.). http://www.counterplay.org/ (Accessed 11 June 2019)

- Deterding, S. (2018). Alibis for adult play. Games and Culture, 13(3), 260–279.

- Deutsche, R. (1996). Evictions: Art and spatial politics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, p. 295–296.

- Dokk1. (n.d). (https://dokk1.dk/english) (Accessed 11 June 2019)

- Dönmez, D. (2017). The paradox of rules and freedom; ant and life in the simile of play. In M. MacLean, W. Russell, & E. Ryall (Eds.), Philosophical perspectives on play (pp. 166–176). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Forss, A. (2007). Paikan estetiikka: Eletyn ja koetun ympäristön fenomenologiaa (Aesthetics of Place: The Phenomenology of Lived and Experienced Environment). Helsinki: Yliopistopaino.

- Frosham, D. (2015). Mapping beyond cartography: The experimental maps of artists working with locative media (Doctoral thesis). Exter: University of Exeter.

- Granö, P. (2004). Näkymätön ja näkyvä lapsuuden maa, leikkipaikka pellon laidasta tietokonepeliin (An invisible and visible childhood land, a playground from the field to a computer game) Piironen, (ed) (2004) Leikin pikkujättiläinen. Helsinki, WSOY. p. 40-49.

- Hänninen, R. (2003). Leikki: Ilmiö ja käsite (play: A phenomenon and a concept). Jyväskylä: Jyväskylän yliopisto.

- Heljakka, K. (2013). Principles of adult play(fulness) in contemporary toy cultures: From wow to flow to glow. Available from Aaltodoc.

- Hidalgo, C., & Hernández, B. (2001). Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(3), 273–281.

- Horlings, L. G. (Ed.) (2019). Sustainable place-shaping: what, why and how. Findings of the SUSPLACE program; Deliverable D7.6 Synthesis report. Wageningen University and Research, Wageningen. https://www.sustainableplaceshaping.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/D7.6-SUSPLACE-Synthesis-Report.pdf

- Hugly, P., & Sayward, C. (1987). Relativism and ontology. Philosophical Quarterly, 37(148), 278–290.

- Huizinga, J. (1955). Homo ludens: A study of the play-element in culture. Beacon press. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Hyde, L. (1998). Trickster Makes This World: How disruptive imagination creates culture. Edinburgh and London, Canongate.

- In-Situ. (2018). Artistic Acupuncture for Places in Europe. In-Situ: European Platform for Artistic Creation in Public Space. http://www.in-situ.info/en/activities/en/think-tank- artistic-acupuncture-for-places-in-europe-20?fbclid = IwAR2zRCsAmL3DTyscUNmV-r-zKH8ShFKjKLP_EL NsoR5EEIde78a1DyrOUf0)

- Innocent, T. (2020). Citizens of play: Revisiting the relationship between playable and smart cities. In A. Nijholt (Ed.), Making smart cities more playable (pp. 25–49). Singapore: Springer.

- Jankowski, F. (2019). Combining attachment surveys, collaborative photography and forum theatre for eliciting and debating the plurality of relation to place. Unpublished manuscript. https://www.lyyti.fi/att/7f13d3a67e/Bbb5BA6ec7c866e3aDf298546A902E89196324700639

- Johanson, K., & Glow, H. (2018). Reinstating the artist’s voice: Artists’ perspectives on participatory projects. Journal of Sociology, 55(3), 411–425.

- Johnson, S. (2017). Wonderland: How play made the modern world. London: Pan Books.

- Jokela, T. (2019). Arts–based action research in the north. In George W. Noblit (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of education. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.522.

- Kester, G. (2004). Conversation pieces: Community and Communication in modern Art. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 58.

- Korstanje, M. (2015). The Anthropology of artports: Criticism to non-place theory. Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research (AHTR), 3(1), 40–58.

- Lakoff, R., & Johnson, G. (2003). Metaphors We live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Levinas, E. L. (1989) The Levinas reader, Edited by Sean Hand, Oxford: Blackwell

- Lundman, R. (2019). Participatory Urban Design – researching for best practices (PARTI). Turku: University of Turku.

- Matarasso, F. (2012). ‘All in this together’: The depoliticisation of community art in Britain, 1970-2011, Community, Art, Power: Essays from ICAF. Rotterdam: ICAF.

- Mesch, G. S., & Manor, O. (1998). Social ties, Environmental perception and local attachment. Environment and Behaviour, 30, 504–519.

- Nelson, R. (2013). Practice as research in the arts: Principles, protocols, pedagogies, resistances. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nemeth, J., & Schmidt, S. (2011). The privatization of public space: Modeling and measuring publicness. Environment and Planning B Planning and Design, 38(1), 5–23.

- Nijholt, A. (2015). Designing humor for playable cities. Procedia Manufacturing, 3(C), 2175–2182.

- Playful Mapping Collective. (2016). Playful mapping in the digital age. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures.

- Riikonen, E. (2013). Työ ja elinvoima: eli miksi harrastukset, leikki ja taide ovat siirtymässä työn ja hyvinvointiajattelun ytimeen? (Work and vitality: so why are hobbies, play and art moving to the heart of work and well-being) Helsinki: Osuuskunta Toivo.

- Russell, W. (2013). Towards a spatial theory of playwork: What can lefebvre offer as a response to playwork's inherent contradictions? In E. Ryall, W. Russell, & M. Maclean (Eds.), The philosophy of play (pp. 166–174). Oxon: Routledge.

- Schrag, A. (2016). Agonistic tendencies: The role of conflict in institutionally supported participatory art projects (PhD thesis), Newcastle: Newcastle University.

- Sharp, J., & Thomas, D. (2019). Fun, taste, & games - an aesthetics of the idle, unproductive, and otherwise playful. Connecticut: MIT Press.

- Skovbjerg, H.-M. (2018). Counterplay 2017 – ‘this is play!’. International Journal of Play, 7(1), 115–118.

- Stott, T. (2017). Play and participation in contemporary arts practices. New York: Routledge.

- Sullivan, G. (2010). Art practice as research: Inquiry in visual arts. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Tate. (n.d.). ‘Socially Engaged Practice’ tate.org. (https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/s/socially-engaged-practice (Accessed 12 March 2020)

- Walsh, A. (2019). Giving permission for adults to play. The Journal of Play in Adulthood, 1(1), 1–14.

- Zimna, K. (2010). Play in the theory and practice of art (PhD Thesis). Loughborough: Loughborough University.