ABSTRACT

This article examines how cultural diversity is incorporated into processes of urban renewal, creating images of the city, and considering local governance actors and strategies. It adopts the concept of diversity regimes to compare the two major cities in Portugal. The two cases studied here demonstrate the multiplicity of strategies employed to accommodate immigration and cultural diversity in local political action, but where city policy is in both cases aimed at the integration of migrants. The comparison of differentiated agency levels of local policy reveals distinct positions and models of intervention. These result from differences in the number of migrants, institutional settings and how the discourse of diversity does or does not incorporate narratives of territorial development and images of the city. We argue that what is relevant is the interplay between how governance networks are structured and participated in by migrants and how diversity discourse is incorporated (or not) into territorial development narratives. Both are part of new models of urban governance where the language of diversity and the symbolic arrangements to which it gives rise do not constitute a migration policy but rather a set of representational techniques for the creation of urban imaginaries.

1. INTRODUCTION

Terms such as ‘intercultural’, ‘cosmopolitan’ and ‘diverse’ are currently part of the lexicon through which the identity of cities is fixed in the context of globalization (Burchardt, Citation2017). While distinguishable memories, heritages and identities are constructed through urban planning and marketing, the complex cultural intersections that the new cosmopolitanism entails are reasserted. This is an extension enhanced by the relevance that culture as an asset has assumed in urban regeneration policies (Evans, Citation2005). It is in this context that we should enquire about the role that cultural diversity plays in urban development. This article examines how cultural diversity is incorporated in processes of urban renewal, creating images of the city, paying attention to the subjects and strategies of local governance. In other words, how are immigrants and ethnically diverse groups included in the strategies and practices of local governments and in which ways do political decision-makers take advantage of cultural diversity in certain parts of the urban fabric to create images of the city.

The article draws on the concept of diversity regimes (Raco, Citation2018), and in this sense it engages with the literature on urban and diversity governance (Schiller, Citation2015; Oliveira & Padilla, Citation2017), local models of immigrant integration (De Graauw & Vermeulen, Citation2016; Nicholls & Uitermark, Citation2013) and urban imaginaries (Bianchini, Citation2006; Soja, Citation2000).

This study, adopting the methodology of a case study (in other words, of detailed comparisons), discusses the examples of Lisbon and Porto as cities in which cultural diversity has grown more complex.

Processes such as these challenge city governance in various ways which demand structured responses according to needs, or the perception of needs. The governance of cities today is not limited to demands from government bodies, whether national or local. Rather, it involves multi-agency working, partnerships and policy networks that cut across organizational boundaries requiring coordination to achieve certain objectives, collectively defined and discussed in uncertain and fragmented environments (Le Galés, Citation2011; Denters & Rose, Citation2005). Conceptually, this entails decentring decision-making processes, turning them into polycentric systems, in local, public, issues.

Diversity governance, in a broad sense, focuses specifically on policies and strategies to accommodate cultural diversity in multilevel institutional frameworks (Koenig & Guchtenaire, Citation2007). However, looking specifically to the local level, and bearing in mind that integration policies are increasingly the remit of local bodies (Caponio & Borkert, Citation2010), diversity governance consists of the arrangements between diversity narratives adopted by different governance regimes and the concrete governance practices of local accommodation of socio-cultural diversity. Yet, diversity has gained an autonomous meaning, and as an idea or concept used in urban development and planning it structures governance practices; it is in this sense that we use the term ‘diversity regimes’ (Raco, Citation2018; Saeys et al., Citation2019).

Drawing from the assumption that cities have an appreciable amount of autonomy in national contexts, a factor which might be acknowledged as the application of the concept of paradigmatic pragmatism (Schiller, Citation2015), there is a wealth of research on the importance of the local in the processes of integration of immigrants (Glick Schiller & Çağlar , Citation2011; Caponio & Borkert, Citation2010; Malheiros, Citation2011; Gebhardt, Citation2014; Emilsson, Citation2015; Padilla & Azevedo, Citation2012). Indeed, instead of national paradigms and approaches, there is currently an emphasis on pragmatic ways in which these flows are managed locally at the city level (e.g., Brettell, Citation2003; Glick Schiller & Çağlar, Citation2011, Citation2015; Foner & Rath, Citation2014). Furthermore, the significance of local pragmatism in accommodating immigrant populations often contrasts with the limitations imposed by national integration and residence policy (Joppke, Citation2017).

Therefore, this article focuses on a comparison between two case studies at the intra-national level. The choice of the two main Portuguese cities – Lisbon and Porto – is of analytical interest for two main reasons. So far there is a notable dearth of comparative analysis between the two cities regarding migrant integration and diversity policies. Contrast this with so many other European states where systematic comparisons have been produced to make us wonder about such a gap. Although this may be interpreted as a necessary reason, it certainly does not constitute a sufficient reason to sustain a methodological choice. A second aspect should then be highlighted. Both cities undergo dynamics of upgrading and renewal of the city centre, ‘patrimonialization’ and tourism gentrification, in areas densely populated by migrants. Third, contrary to other comparisons where what is underlying is the contrast between cities open to cultural diversity and others that perceive it as a threat to social order (Uitermark, Citation2012; Tillie & Slijper, Citation2007), in the case at hand, city policy in both cases caters for migrant integration. Furthermore, the cities’ social inclusion policies do not collide with the national policy framework or its integration model (cf. Caponio & Borkert, Citation2010).

Considering the former, a combination of urbanism, culture and diversity has been central to these models and has been tested in many European capitals (Wood, Citation2012). Understanding how this configuration works or fails in different urban contexts is what we intend to do by confronting a space with a remarkable diversification history, such as the quarter examined in Lisbon, with a reality where this trend is embryonic, but with increasing expression, such as the one analysed in Porto.

The research carried out in this paper was based on a qualitative approach and focused on the mechanisms and strategies for accommodating cultural diversity in the local space, exploring the strand of the strategic, deliberative and discursive aspects of local governance.

In the first part we offer an overview of the main theoretical approaches to the governance of diversity, more particularly the relationship between diversity policies and entrepreneurial models of city-making. We discuss the concept of diversity regimes as proposed by Raco (Citation2018), stressing the importance of looking at both the structural dimension and symbolic systems discursively enacted. The next section depicts the contexts of the fieldwork and offers a description of the methodology. We then examine empirical differences between discourses and practices towards diversity in the two cities, identifying the most significant differences in policymaking. We look at structures of governance and the symbolic layers that underpin the discourse on diversity.

2. DIVERSITY REGIMES, URBAN GOVERNANCE AND INSTITUTIONAL STRUCTURES

The correspondence between national models, variously called paradigms (Bertossi & Duyvendak, Citation2012), philosophies (Favell, Citation2000) or grand narratives (Alba & Foner, Citation2013), and immigrant integration policies has been critiqued using the local scale. The rationale is to show how national models are modified when applied at the level of cities. In this case, national integration paradigms are contrasted with local policies, showing that the former do not function as independent variables to explain immigrant integration modes and the diversity policies associated with the latter. On the contrary, there is a level of paradigmatic pragmatism (Schiller, Citation2015) that refracts the broad outlines of national models in local strategies and practices. Consequently, there is a readjustment through pragmatic forms of diversity management that makes local policies far from being direct offshoots of national frameworks (Hoekstra, Citation2018; Schiller, Citation2015; Jørgensen, Citation2012; Alexander, Citation2007).

However, this approach contains a normative bias, reflected, for example, in the idea that the norms of national models should be reproduced at the local/urban level; when this does not occur, it is said that the models suffered from an ‘implementation gap’ adjusted to local conditions. As Mouzelis (Citation1995) showed, any paradigmatic system is a system of practical application, which the author, drawing on linguistics, calls the syntagmic level. Indeed, the normative level can always be instantiated at a pragmatic level – of actual relationships and strategic needs of the actors involved – and there are degrees of freedom for contingency here.

Alternative explanations for this mismatch have been found, on the one hand, in the institutional domain, in particular in political opportunity structures (Jørgensen, Citation2012). Jørgensen’s interpretation deepens a theoretical line with a vast tradition in studies on local immigrant integration (Ireland, Citation1994; Penninx et al., Citation2004; Koopmans et al., Citation2005), but integrates the important aspect of the autonomy of culture. In turn, Hoekstra (Citation2018) examines the imaginaries of diversity that serve as a template for political actors. The author attributes significant weight to institutional logics, but these are informed by ‘tacitly shared imaginations about immigrants’ place in the urban community’ (p. 375).

A different line of research locates the phenomenon in urban development policies and management models of contemporary cities (Raco, Citation2018; Raco & Taşan-Kok, Citation2020). These authors propose the concept of a diversity regime that derives from the realization that cities construct and use the notion of diversity in different ways; specifically, turning diversity into an instrumental tool for promoting globally oriented economic growth coupled with a policy of social cohesion and cultural dynamism. Such regimes are made up of ‘well-organised networks and constellations of actors and institutions that seek to fix narratives and framings of diversity to pursue selective political agendas’ (Raco, Citation2018, p.11).

Seen in this way, these diversity regimes are no longer interpreted either as distortions or as direct duplications of national immigration models and policies. Instead, they more appropriately reflect the new urban governance and its objectives of repositioning cities in a global marketplace. The language of diversity and the symbolic arrangements to which it gives rise do not constitute a migration policy but rather a set of representation techniques for creating urban imaginaries. In this sense, the cases we discuss here are not confined to the strict implementation of migration policies and are more concerned with the urban policy taken as a generic whole.

In this line of thinking, we argue that the perspective that reads into strategies of representation of diversity in urban spaces (only) those policies that generate greater or lesser openness to the integration of immigrants (De Graauw & Vermeulen, Citation2016; Nicholls & Uitermark, Citation2013; Scholten, Citation2013) is incomplete. Despite the undeniable importance of an approach that stresses the ties between public institutional bodies, immigrant organizations and local political strategies, in identifying discourses and specific institutional structures, this approach continues to assume that the discourse of diversity is logically (if not practically) tied to integration policy. Furthermore, considered through the lens of governance mechanisms, this interpretation relegates the issue of the urban and its models of development to epiphenomena, contrary to the ‘diversity regimes’ approach that considers such mechanisms as crucial in the choices cities make about cultural diversity.

It is therefore important to retrieve another approach, one which highlights the role of diversity in urban imaginaries. This line of thinking is indebted to Lefebvre’s contributions to the theory of the urban, in that for him the urban imaginary is constituted through negotiation between exchange value and the utopian potential of the city. In a less political vein, Bianchini (Citation2006, p. 15) defines urban imaginaries as the ‘media and urban representations of meanings and memories’; mental constructs of the city associated with aspects of fantasy and desire. Another view of urban imaginaries sees them as ‘the interpretative grids through which we think, try out and assess … the places where we live’ (Soja, Citation2000, p. 324). In Bianchini’s (Citation2006, p. 13) conception, the idea of the urban imaginary is narrowly associated with that of ‘urban mindscapes’, these being understood as ‘a structure of thinking about the city … a bank of urban images which includes local and external images of it’.

We should combine these two literatures by tempering the fantasist and metaphorical side of the language of ‘urban imaginaries’ with the empirical realities of stakeholders and decision-makers who contribute to them by being active participants in specific institutional configurations that either open the framework of opportunities or constrain the possibilities of action and their cultural understandings. In other words, we should add a practical and strategic dimension to the construction of those same imaginaries.

In this context, we argue that cultural diversity, in addition to its presence and daily practice as a reality in cities, incorporates very precise strategies of urban governance translated into the contents of planning, place marketing, preparation of territories for tourist demand and, finally, accommodating the expressive patterns of different cultural groups in the logic of the aestheticization of urban living. These dynamics create structures of opportunity – for the emergence of identities, business practices and accommodation of citizenship claims – but they also create tensions and contradictions. Indeed, although we do not deal with such phenomena here, processes of touristic or urban gentrification bring about the expulsion of the weakest fringes of city centre inhabitants, who are often of immigrant origin (Mendes et al., Citation2020; Atkinson, Citation2000; Newman & Ashton, Citation2004; Cross & Moore, Citation2002).

Urban governance is here understood as the complex of networks and (public–private) partnerships mobilized in a neoliberal policy environment of urban competitiveness and state rescheduling oriented towards locational policies. The mechanisms of such a compound include new regulatory logics and a focus on the local or regional territory to the detriment of the national (Brenner, Citation2004; Jessop, Citation2002). This re-dimensioning of the scale of action implies that local policies must be related to the dynamics of globalization, namely the transnationalization of practices, consumption and mobilities that directly affect urban culture (De Frantz, Citation2013). In this model, it has been pointed out that the governance of culture (Kong, Citation2009) becomes an integral part of institutional change and urban policy orientation. In this context, culture is shaped as an asset, with obvious implications for the symbols and images that allow the legibility of the city and its places. Governance also has a discursive dimension (De Frantz, Citation2013) expressed in the frameworks that are used for the construction and interpretation of urban policy options.

In the European case, it was recently pointed out that there is a direct link between the ‘intercultural turn’ in European politics – the idea that the promotion of interaction between cultures is more important than the isolated development of cultural belonging – and urban governance (Adj-Abdou & Geddes, Citation2017). When translated into urban governance terms, cultural diversity is seen as a resource that should be used in strategies for urban regeneration or the revitalization of city centres, especially in its most evident materializations of ‘folkloric interculturalism’ (Caponio & Ricucci, Citation2015).

Zapata-Barrero (Citation2015) characterized a specific European intercultural model that he called constructivist. Its main axis involves considering cultural diversity as a resource that must be enhanced and reproduced, with benefits for other spheres. Constructivist models are considered the core of European political agendas for the incorporation of immigrants into cities. This allows us to speak of a European intercultural model, despite its national appropriations and specific historical configurations (Adj-Abdou & Geddes, Citation2017). This model embodies the main guidelines of an approach that has conventionally been called the ‘diversity advantage’. This concept condenses the idea that cultural diversity should be seen as a resource intrinsically linked to innovative policies in cities from a perspective of comparative economic advantage (Wood & Landry, Citation2008, p. 12).

There have been several contributions seeking to explain the mechanisms of urban development that use diversity as an ‘advantage’ or ‘dividend’ (Wood & Landry, Citation2008; Syrett & Sepulveda, Citation2011; Florida, Citation2005). While some authors praise the value of a favourable environment for investment and attracting highly skilled labour, others focus on the practical ways municipal authorities have mobilized to reinforce differences between cities. Among such practices and marketable displays can be listed the promotion of ethnicized businesses, diasporic trade networks and the promotion of ethnic festivals and neighbourhoods (Evans, Citation2001; Syrett & Sepulveda, Citation2012). However, the critique of this stand elaborated by Peck (Citation2005) points to the discrepancy between the celebration of the potential of the cultural dimension and the effective structuring power of an ‘urban orthodoxy’ that links its strategies to interlocal competitiveness, gentrification, the marketization of places and the deepening of socio-spatial inequalities.

Part of what Zapata-Barrero calls the ‘constructivist’ model can be found in pragmatic, but contextually adjusted, policy agendas for promoting urban diversity. Such pragmatism is largely linked to the articulation between models of urban growth and competitiveness and the discourses that are elaborated around tolerance and acceptance of diversity (Raco, Citation2018). This strand is derived from an economistic reading of diversity associated with neoliberal orthodoxies of urban development.

Again, and addressing an idea developed by Keith (Citation2005), authors such as Raco and Taşan-Kok (Citation2020) have highlighted the use of diversity for curation strategies in the framework of management models and shifts in the languages of representation of diversity in urban policies. According to their research, the assimilation of diversity into curation practices would have the effect of producing it as something ‘visible, celebrated and valued’, while marginalizing generic concerns about the impact of demographic change, emphasizing rather more acceptable cultural narratives structured around ideas of cosmopolitanism, global city ‘branding’ and enhanced economic performance. While they are surely right in stressing the importance of curation practices in urban policies, in our view they offer an overly instrumental perspective of the types of curations of diversity, interpreting them within the framework of governmentality and performance technologies (Ahmed, Citation2012). Such an understanding leaves no room for practical–moral valuations nor for the accommodation of immigrants’ agency itself, often in line with the visibility strategies implied in such curations. Still, following their challenge to analyse how ‘specific curations of diversity are developed and operationalized’ (Raco & Taşan-Kok, Citation2020, p. 44), our research examines two case studies through which we raise some questions about the linearity of previous assumptions.

While we pay attention to public narratives of diversity, to how these are fitted to pragmatic agendas for the development and display of cities, there is also an infrastructural level, the particular level of governance networks, of partnerships on the ground, which constitute, albeit at a lower place in the hierarchy of power, the encounter between such narratives and concrete policies and their implementation. By analysing two cities whose discourses on diversity share the same tenor – that is, are equally open and tolerant of cultural diversity – but whose normative and material structures for implementing these notions differ, we show that different institutional logics determine a greater or lesser centrality of these same options in the set of urban policies.

3. CONTEXTS AND METHODS OF RESEARCH

The research took place in the two largest Portuguese cities with the most significant concentration of immigrants, Lisbon and Porto, between 2017 and the first half of 2018, and was integrated in the project ‘Diversities, Spaces and Migrations’, funded by the Asylum Migrations and Integration Fund (AMIF).Footnote1 It follows the premises of a multilevel approach, but unlike other interpretations for which the focus is on the national or the supranational level (Ambrosini & Boccagni, Citation2015; Gebhardt, Citation2014), our focus is on the differentiated levels of local political implementation. The analysis combines the municipal level with the parish level (a lower level in local government entities in Portuguese municipal territories), having as the backdrop the relationship between the political initiative framework and localized territories where the immigrant presence denotes these very places as being culturally diverse. Given the importance of this relationship, below we offer a brief history of the settlement process of immigrant communities in each of the research contexts.

For the two cities, a set of methodological procedures were applied: (1) document analysis of municipal strategy papers, local and social development policy instruments and other sectoral policies from the early 1990s to 2018; (2) the collection and handling of statistical data, provided by the National Institute of Statistics (Census, since 1981) and by the Statistical Office of the Aliens and Borders Service (Foreign population with legal resident status, between 2008 and 2020); (3) semi-structured interviews with social actors in the municipalities (three interviews with councillors, advisors and technicians), parishes (three interviews with parish council chairpersons and advisors) and third-sector organizations (11 organizations, mainly representative of migrants communities), conducted between 2017 and the first half of 2018; and (4) informal local contacts with members of the communities in both areas between 2017 and the first half of 2018.Footnote2

The interviews with public bodies focused on two main areas: on the one hand, policies towards immigration and diversity; and, on the other, the functioning of governance networks and the impact of diversity in the public space. In the case of interviews with grassroots organizations, the focus was on networks with public authorities and between communities, the perception of measures and initiatives to accommodate cultural diversity, the activities carried out by organizations, and the impacts of the transformation of the territory, both socially and demographically. Data were coded collectively using a systematic thematic analysis approach to identify the key issues raised by respondents. This involved interpretive code-and-retrieve methods wherein the data were transcribed and coded and an interpretative thematic analysis was undertaken using Maxqda.

We start by giving an overview of the share of foreign citizens at the two levels considered in both cities. Whereas in the capital foreigners account for 10.3% of residents, in Porto they are 7%, which is nevertheless still above the national average of 6%.Footnote3 At the level of the parish councils considered, the increase in the foreign population in the intercensal period is notorious. For Porto, in the Union of parishes of the historic centre of Porto,Footnote4 on which we focus in this article, the share of the immigrant population is approximately 13% of the resident population. In the case of Lisbon, in the two parishes considered, also located in the historical centre of the city, the resident foreign population represents 24% (Arroios) and 34.5% (Santa Maria Maior). These parishes were chosen in this study because they are the neighbourhoods where cultural diversity is most visible in the city as a whole. However, these cities present distinct histories of differentiation as well as differentiated population settlement patterns. The presence of immigrants in the historical centre of Lisbon (as in the city and metropolitan area of Lisbon) started to be noticed in the 1980s, being evident in the 1990s. In the historical centre of Porto, the phenomenon manifested itself from the end of the 1990s and it was only in the following decade that specific areas’ downtown started to be identified as an area of concentration of immigrants. While exhibiting distinct paths, both territories have long been marked by the presence and interaction of people of diverse origins and both have witnessed a process of ‘Asianization’. In the case of Lisbon, the presence of immigrants of Asian origin dates back to the end of the 1970s when a significant contingent of Indo-Portuguese citizens settled in this area of the city and established their businesses there (Mapril, Citation2010). From the 1980s onwards, other Africans, and also Chinese and Pakistanis, would join them, reinforcing the Asian presence (Menezes, Citation2001, p. 77). In the 1990s there was an increase in the number of immigrants from the Asian continent, namely from countries such as India, China, Bangladesh and Nepal, ‘strengthening its multicultural nature of great diversity and contributing to the consolidation of this area’s hosting, residence and daily life functions for waves of non-Western migrants’ (GABIP-AR [Support office for priority intervention neighbourhoods], 2017, p. 2). In conjunction with these inflows of Asian populations, this urban territory has also witnessed other residential flows, including Erasmus students and those from other parts of the country; also some segments of young, qualified adults from the suburban periphery coming in search of a more urban, cosmopolitan lifestyle, non-permanent city users (Costa & Magalhães, Citation2014) and other, mostly European, foreigners with higher qualifications who are generally older than most of the residents.

As regards Porto, a significant part of its historic centre is typified as ‘a cosmopolitan, business street, where people from various countries and origins circulate, live together and interact’ (Cardoso et al., Citation2011, p. 3). It was the Indian community that (re-)occupied this zone, from the late 1980s, after a period of significant demographic decline, following on from the Chinese and, from the late 1990s onwards, the Pakistanis and Bangladeshis in addition to Egyptians, Moroccans and Algerians. Despite the large number of foreigners who came to this place, there are no areas in which the foreign population is highly concentrated: ‘what makes the city interesting is the fact that there are no ethnic enclaves as you see in cities like London. … What you see … is the peaceful co-existence of many different cultures’ (cf. Público, Citation2007).

Several stores are owned or managed by foreigners from Asian countries; in line with this growth, many Islamic immigrants, mainly from Bangladesh, have settled in the area, leading to the establishment of a makeshift and, apparently, temporary mosque. New investments also took place, particularly in tourism (sometimes replacing or repurposing older businesses) specifically as migrant entrepreneurs and owner/managers of local and other types of tourist accommodation have replaced their old investments (Rocha, Citation2017). In addition, changes in patterns of investment and real estate prices in the historic centre of Porto have also had a significant impact on commercial and residential dynamics.

Moreover, the image of these territories where the concentration of immigrants was most prominent (in Lisbon and Porto), before the processes of urban regeneration and the tourist gentrification that followed, was associated with street prostitution, drug trafficking, homelessness, crime and other ‘marginal’ phenomena (Nicodemos & Ferro, Citation2018; Menezes, Citation2012). The dynamics of change in recent decades are part of the transformation of the historic centre, where there are increasing gentrification trends and new migration patterns that have resulted in a demographic, economic and social recomposition of the centre (Mendes, Citation2018; Seixas et al., Citation2013), taking advantage of the fall in value associated with the ‘abandonment’ which these centres have suffered over many decades. Urban regeneration and the resulting transformations brought about an increase in tourism-oriented businesses: souvenir shops, hotels and short-term accommodation (Santos et al., Citation2017, pp. 15–16), alongside shops and restaurants of foreign cuisines (Chinese, Indian, Turkish), which reflect local cultural diversity.

4. TWO MODELS FOR RECONCILING DIVERSITY WITH URBAN DEVELOPMENT?

This analysis takes up the idea of diversity regimes and analyses governance organizations and the discourses surrounding them. In other words, it sees governance as a method of social organization that combines institutions (rule systems that define categories of interaction) with other symbolic systems (such as narratives, beliefs, ideologies and values) for coordinating politics and public strategic choices.

Contrary to many other examples identified in the literature, it is not insignificant that the local understanding of cultural diversity and, to a large extent, the integration of immigrants, is associated, in an unproblematic way, with the national framework whose insistence on the promotion of interculturality has marked early on political and national conceptions of the governance of cultural diversity. Unlike other European experiences, where the discrepancy between the strategies of the cities and the national framework is systematically pointed out, in our case, the central discourse has been marked by being tolerant of and an apologist for migrants and immigration. There are several reasons for this, which we will not detail here, but among them the fact that Portugal is one of the countries in the world with the most-aged population and therefore needs to renew its generations weighs significantly in the way migrants are perceived and constructed by authorities. On the other hand, there was no real political articulation of the anti-immigration speech, that is, it was only with the recent rise of a far-right party in Portugal that foci of politicization of immigration emerged (Carvalho, Citation2019).

The analysis of Lisbon municipal (Câmara Municipal de Lisboa – CML) policy documents revealed increasing references to immigrants and at the same time the multiplication of initiatives for promoting diversity. Political discourse and especially municipal strategy documents make clear that these topics have been explicitly addressed. Policies oriented towards immigration and diversity promotion have been visibly strengthened and, in addition, issues relating to immigration have increasingly been incorporated into municipal policy documents, not only in areas traditionally associated with this topic (e.g., social policy) but also in culture, economics, health and tourism, amongst others. Cultural policy is a flagship example of this cross-fertilization: the earliest cultural strategy document for Lisbon stresses the need to ‘enhance the city’s identity (identities) and memory (memories), diversity and multiculturalism’ (Costa, Citation2009, p. 22) acknowledging that its intercultural vocation is an ‘added value which should be promoted, making it more attractive to artists and creatives’ (p. 39) to which ‘various sub-brands may be associated. (…) Among many other narratives are those of Africa and Brazil, intermittent multiculturalism and immigration’ (p. 43). This close relationship between culture and diversity contrasts with the model of some other cities, such as Barcelona, where there is no connection between the department in charge of cultural policy and that which deals with intercultural strategy, revealing a deficit in terms of ‘diversity management’ (Zapata-Barrero, Citation2014).

The Lisbon Strategic Charter 2010–2024 – A Commitment to the Future of the City – reinforces the importance of diversity and multiculturalism for Lisbon, particularly in those sections that address issues of social cohesion and inclusion, where Jane Jacobs’s conviction that diversity is one of the main attributes of cities is largely reproduced in a report by the town council.Footnote5

Lisbon, to be sure, when compared with global cities with a more permanent history of attracting cultural and capital flows, such as London or Toronto, does not directly emphasize the role of diversity in the labour market or technological innovation, as Raco and Taşan-Kok (Citation2020) show for the above-mentioned cities. In effect, it would be difficult for its strategy to have an impact in these fields because it is still in an emerging position in the global labour market. Instead, it defines its commitment in terms of an ecology of diversities, where hybrid identities find expression in the life and culture of its neighbourhoods. Thus the Strategic Charter defines two types of complementary identities that are equally strong on the international stage. On the one hand, ‘Lisbon, capital of the Republic and the heart of its Citizenship, open to the Tagus and the World’, underlines the combination of domestic life at its centre and its global designs. On the other hand, ‘Lisbon, a cosmopolitan city of neighbourhoods’ stresses its roots in its traditional morphology, built and rebuilt over the centuries. It is in this sense that Lisbon’s strategy is peculiar when compared with other European cities. The aim is to cross-fertilize a certain parochialism with cosmopolitan globalization; a cross-fertilization finding expression in the idea of ‘Lisbon, city of discovery’, where a rich heritage, creativity, entrepreneurship and cosmopolitanism all complement each other: ‘a city sure of itself and on the frontiers of knowledge, with national and global projection is a platform for opportunity, creativity, and entrepreneurship’ (Lisbon Strategic Charter 2010–2024, 2009, p. 4). This strategy revisits the themes of the ‘curation of diversity’ associated with a language of managerial governance disseminated in models of ‘entrepreneurial identity’ (Lisbon Strategic Charter 2010–2024, 2009).

The strategic options for the 2018/2021 City Council mandate recommend that Lisbon, for its part, be made into a ‘city of innovating and solidary cosmopolitanism’ and ‘with culture and openness’, concepts clearly expressed in the following passage:

Lisbon is an open, welcoming, tolerant city. … It is a city that encourages and acknowledges the enriching qualities of multicultural living, multilingualism, and ethnic and religious diversity. It is a city which combats xenophobia, homophobia and other discriminatory fundamentalisms, affirming its intolerance of intolerance. (CML, Citation2018, p. 57)

Lisbon as a modern and cosmopolitan city values cultural, ethnic and religious diversity. In welcoming and including people of different cultures and origins, Lisbon has benefitted from having a population which contributes to its rejuvenation and economic dynamism. (CML, n.d., vol. 1, p. 76)

While at the level of discourse this accommodation of diversity is unquestioned and is increasingly found in the city’s branding strategies, in daily practice not all sectors of the municipality take it into account, although it is clear that the city council plays (and must play) an active role in the context of diversity, seeking to ensure that the various sectors are committed to that purpose. It should be mentioned that the drafting and implementation of the Municipal Plan for the Integration of Migrants, in 2015 and already in its third edition,Footnote6 were backed up by a network of contact points, which include various municipal departments and offices for sharing information, collecting ideas for diagnosing problems and proposals, and monitoring and following up on the plan. As one councillor’s aide said, ‘we want to … involve the whole City Council, so that it is not just a responsibility of the Social Rights office but a commitment which cuts across all City Council departments’.

It means that underlying the rhetoric of place branding is a body of material investment in diversity. Examples range from initiatives aimed at incorporating immigrants such as the Local Centre to Support Migrants’ Integration (established in 2005) and the Municipal Plan for the Integration of Migrants (2015) to multiple events sponsored or supported by the council (essentially cultural events), bodies specifically set up in this context, such as the Municipal Council for Interculturality and Citizenship (in 1993) and the Lisbon World Crossroads office (in 2009), and also the financial support given in the form of ad hoc grants for migrant communities (such as for building the new Mouraria mosque). Therefore, the city council’s executive sees ‘interculturalism’ as a symbolic added value within an overall urban marketing strategy (Oliveira & Padilla, Citation2017) where the value of that concept goes beyond the council’s image policy, being closely coordinated with the municipality’s inclusion policies.

We really want the Municipal Council for Interculturality and Citizenship to discuss the city's policy, about interculturality, migrants, … to have more in-depth discussions, reflection, debate. … We do not want it to be a council to validate what the Municipality does or does not do. (interview with a councillor advisor)

Lisbon has adopted several initiatives which demonstrate its commitment to the intercultural approach. The city council has formally adopted a public statement [defining Lisbon] as an intercultural city. The local government has also designed an ‘intercultural city strategy, being one of the pillars of the mayor’s programme, and has developed an integration action plan to put it in practice. (Council of Europe, Citation2014, p. 5)

On the other hand, the two parishes in the area under study in Lisbon have different strategies. While in one case diversity is a strategic item on the executive’s programme, and is highlighted as a distinctive feature of the neighbourhood, in the other, despite the proximity to some communities, these relationships are not constructed as elements that confer a peculiar identity to this urban area. Rather, it is interpreted as a responsibility of other levels of central and municipal government, or of local and immigrant organizations which, in the view of this parish executive, should be the main promoters of initiatives for the inclusion of immigrants, given that these issues do not fall within their field of responsibility. These differences reflect the options of the local governments in each of the territories and depend on personal or party political positionings and priorities of their respective leaders, in addition to being affected by the availability of resources, the results of prior experience in this field, and other factors. As Oliveira (Citation2015) argues, the difference in contexts reproduces different grammars of interculturality, operating in specific ways according to the space and its history and also its actors’ broader conception of the city. In this connection, interculturality should not be seen as a homogeneous model: on the contrary, institutions and their actors have their grammars, tied to the urban space, and these, in turn, exert strategic influence on the representation of those spaces.

Still in the city of Lisbon, we find that the third sector complements the political work of the local authorities and that there is a wide array of organizations undertaking projects tied to immigration. Some of these bodies work on their own or on an ad hoc bilateral basis, while others have an established network of partners, through whom they carry out a significant portion of their work. It also emerged that some of these bodies (and partnerships) work well in networks, and not only in their own ‘spaces’ (geographical, target audience and thematic) but also outside them. It should be noted that the municipality’s operations helped to build and organize the network of actors, whether on a cross-cutting basis (e.g., within the Municipal Council for Interculturality and Citizenship) or at the local level (e.g., through Support Offices for Priority Action Neighbourhoods, such as the one set up in the Mouraria).

Some [associations] work very well in a network, they know each other quite well … they work well in the territories, but they have an intervention that goes beyond the territory or the specific monitoring they provide to a particular target group. (interview with a councillor advisor)

Even so, the municipality and parishes have demonstrated on an ad hoc basis increasing political sensitivity to issues relating to the foreign resident population and, at least on a technical level, there seems to have been an uptake in interest in this topic, and it may take its place in the municipality’s (social) policy instruments.

I think [the intention of the municipality] will not be to make it work [the council]. But one of the areas that we are already, at this moment, introducing in terms of working groups in this [Social] Diagnosis and the preparation of the next [Social] Development Plan … has to do with this [immigrants]. (interview with the department head of Porto’s municipality)

The Arroios Parish Council [in Lisbon] is an epic. They have as … the central core of, of their policies of intervention in cultural identity, and the respect for that cultural identity. I think that this is missing in Porto. … So, that there is … let’s say that, that greater openness to the promotion of diversity, even sponsoring or supporting cultural events, as happens so often in Lisbon. A … regarding the city, would probably be a city of tolerance, of cultural diversity. A positive image. And Porto, being a city of tourism, this is probably also important. … But we needed more frequent support. Maybe that root connection, more formal and more frequent, was missing. Not so punctual.

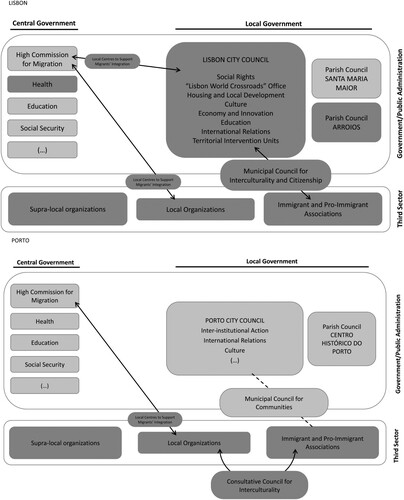

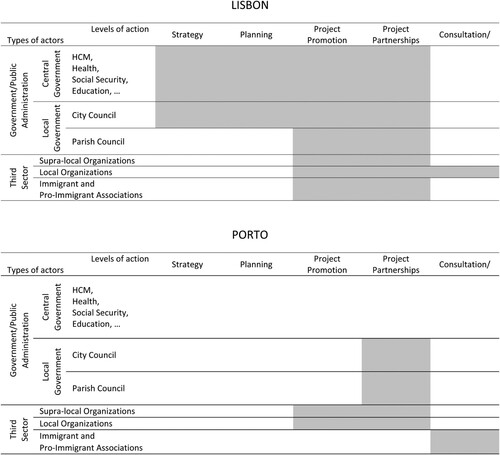

This systematic outline of the activity of different types of actors in the realm of diversity in the two settings under study illuminates the differences identified. Diversity is a relevant topic in local government strategy and planning instruments in Lisbon, and local authorities both promote and are active partners in diversity planning. Third-party bodies take part in these processes or are consulted for them and promote or are partners in projects (). This practice has been consolidated from very early on, at least since cultural diversity was a theme in CML initiatives, a period that can be traced back to 2008 with the initiatives around the European Year of Interculturality (Fonseca, Citation2011). Diversity is understood to be a key element and operates directly at the strategic and planning levels. In Porto, on the other hand, questions of diversity are not part of local authority strategy and planning instruments. Although they are partners in some initiatives, they do not promote projects in this domain; it is third-sector bodies that are the main promoters of initiatives in this field.

Figure 1. Network of actors and levels of intervention (darker = greater) as far as diversity is concerned in the cities of Lisbon and Porto.

Figure 2. Action levels for different types of actors in connection with diversity in the cities of Lisbon and Porto.

The clear differences between the two contexts match substantially different institutional positionings and models of political intervention at both municipal (Lisbon and Porto) and parish council levels. While a great many cities, such as Lisbon, implement such a strategy, seeking to boost their perception in the target publics or to enhance their position in a hierarchy of preferences, the case of Porto clearly shows that even though policymakers promote the same urban processes based on international tourism flows or by pandering to international investors, as the gentrifying trend and the internationalization of the city clearly show, urban policies do not establish the same type of mechanisms about cultural diversity.

Although the absence of a strategy set out in a programme or document in the city of Porto is not negligible, this lack of centrality of the immigrant element and, as a result, of cultural diversity extends to any area of municipal attribution. While there is no mention of immigrants or interculturality in the CMP’s strategic blueprint, this does not mean that the immigration issue does not deserve the attention of the municipality, namely at the level of inter-institutional networking and social development. However, cultural diversity appears to be associated with a providential welfarism where it is posited as a social problem, usually of the order of exclusion, to which the mechanisms of the welfare state must respond. In other words, it is not invoked as an endogenous element in urban growth and identity. Thus, in Porto these themes are not placed in the symbolic and discursive universe of cosmopolitanism or urban development strategies. Likewise, the spaces where it could be strategically enhanced are also not symbolically or organizationally singled out, being instead part of a political and social relationship with public authorities made up of specific opportunities for and facilitators of socially desirable exchanges (ephemeris, games of influence, etc.).

Such exchanges also exist in Lisbon but are enhanced by a broader cultural context whose production and reproduction of plurality are synthesized into a new identity and practice of urban subjectivities. Here we find a local authorities’ approach included in what we call creative cosmopolitanism. Even if a providential welfarism approach underlies municipal action – as is amply demonstrated by the inclusion of immigration and diversity matters in departments responsible for social rights (as happens in Porto, where the topic falls into the social welfare sector) and a vast and rich experience of work with immigrant communities – the grammar which takes diversity into other domains of Lisbon Municipal Council’s action has increasingly asserted itself. In tourism, entrepreneurship, culture, the public space and many other areas, diversity is incorporated as a dividend and a fundamental part of the city’s strategic development plan as set out by the local government.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In this article we have discussed how diversity regimes in cities may be interpreted by taking into account structures of meaning as well as organization. Drawing on data on diversity governance, our approach differs from other approaches mentioned here in so far as it recovers the centrality of urban governance on the pragmatic ways of managing difference. In this sense, it does not subscribe to the languages of immigrant integration, nor to those of urban imaginaries, when taken as mere ‘metanarratives’ (Hoekstra, Citation2018). Urban imaginaries operate and function within a particular strategy for presenting the city; in this connection, they are narratives that are constitutive of social actors, the modalities of agency and the social world with which these interact (Somers, Citation2008). In turn, and in response to Hoekstra’s (Citation2018) challenge to deconstruct the idea of pragmatism, that which is or ceases to be pragmatic is directly associated with the culture of governance. This has two significant aspects. First, it should be situated and interpreted in the context of what is conventionally called urban neoliberalism (Rossi & Vanolo, Citation2015). In this context, the logics of the presentation of diversity are inseparable from the commodification of space and the entrepreneurship systems which have multiplied in urban governance. Second, and consequently, we argue that it is not so much a question of ‘shared imaginations about the place of migrants in the urban community’ (Hoekstra, Citation2018, p. 375) – an issue that necessarily touches on the extension of citizenship and its modalities – but rather of setting up diversity as urban imaginary regardless of what may be judged to be ‘just diversity’ (putting a gloss here on the theme of the just city). The imaginary of diversity, when it is found, is independent of the actual social intercourse of immigrant communities.

Contrary to other studies, the two conceptions emphasized here do not represent visions polarized between integration and rejection, such as in comparisons between regions where integrating migrants is welcomed and others where restricting them is policy and practice. Instead, the two cases studied here demonstrate the multiplicity of strategies employed to accommodate immigration and cultural diversity in local political action, but where city policy caters in both cases to migrant integration, as the result of a broader national discourse on welcoming and accommodating migrants which, so far, has been accepted unequivocally by public institutions.

Yet, the comparison of the action and discourse of municipal and parish councils and other local actors reveals substantially different positions and models of intervention concerning the way diversity is metabolized by urban practice and planning as such. On the one hand, these derive from differences in the ways governance networks are structured and participated in by migrants themselves. On the other hand, in the ways the discourse of diversity is incorporated (or not) into narratives of territorial development and the canonical tropes of urban entrepreneurship practices.

First, and in the wake of the idea that local governance is characterized by the spread of multi-agency networks (Denters & Rose, Citation2005), the dissemination of partnerships with immigrant and third-sector organizations across the various levels of action () as well as across the various fields of social and economic intervention at both local and central levels represent a remarkable difference between cities. To this proliferation of contacts and exchanges we must add the incorporation of immigrant organizations into consolidated bodies belonging to the centrality of local government, such as consultative councils. In effect, in the logic of public–private partnerships, the public authority in Porto seems to have evacuated immigration issues to the space of private bodies, thus leaving little power of influence for immigrant organizations in matters centralized by local government.

A second aspect has to do with the nature, composition and contents, of the narratives of the city that are instantiated by each of the local powers (and here we also include the parish level). Lisbon's focus on a discourse celebrating diversity as a construction of identity has no parallel in Porto. As we have seen in the comparison between the two parishes in the centre of Lisbon, this greater or lesser inclination toward the imaginary of diversity can be explained entirely as a political option. Therefore, the number of immigrants only has a marginal influence. As shown by the different political positions of the two Lisbon parishes, the proportion of immigrants (measured by the number of foreign residents) is greater in the parish that least incorporates the narrative of diversity in its programme and discourse.

In the cases presented here, two broad models were extracted that we classified as providential welfarism and creative cosmopolitanism. These models not only represent different languages for symbolizing diversity but also different strategies for involving actors in the processes of governance of diversity. By this we mean networks between organizations that are also power networks that, depending on their structure and the nature of the organizations involved in them, provide a narrower or wider range of participation modalities for social groups affected by policy implementation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors acknowledge the two anonymous reviewers for their suggestions that refined and improved our analysis.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The project involved collaboration between CIES (Centre for Research and Studies in Sociology), the Faculty of Architecture and CRIA (Centre for Research in Anthropology).

2 All data collected through the interviews resulted from informed consent and have been duly anonymised throughout this article.

3 Source: Sefstat, 2020 e INE/Census 2021.

4 The union of parishes in the historic centre of Porto resulted from the merger of the six previous parishes that comprised the historic centre of Porto.

5 ‘City areas with flourishing diversity sprout strange and unpredictable uses and peculiar scenes. But this is not a drawback of diversity. This is the point, or part of it. That this should happen is in keeping with one of the missions of cities’ (Jacobs, Citation1961, p. 238, quoted in CML, 2010, Report 2, p. 3.

6 The first Municipal Plan for Immigrant Integration that covered the period from 2015 to 2017 was succeeded by the plans for 2018–20 and 2020–22.

REFERENCES

- Adj-Abdou, L. H., & Geddes, A. (2017). Managing superdiversity? Examining the intercultural policy turn in Europe. Policy & Politics, 45(4), 493–510. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557317X15016676607077

- Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press.

- Alba, R., & Foner, N. (2013). Comparing immigrant integration in North America and Western Europe: How much do the grand narratives tell us. International Migration Review, 48(1), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12134.

- Alexander, M. (2007). Cities and labour migration: Comparing policy responses in Amsterdam. Ashgate.

- Ambrosini, M., & Boccagni, P. (2015). Urban multiculturalism beyond the ‘backlash’: New discourses and different practices in immigrant policies across European cities. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 36(1), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2014.990362

- Atkinson, R. (2000). The hidden costs of gentrification: Displacement in central London. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 15(4), 307–326. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010128901782

- Bertossi, C., & Duyvendak, J. W. (2012). National models of integration: The costs for comparative research. Comparative European Politics, 10(5), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2012.10

- Bianchini, F. (2006). Introduction. European urban mindscapes: Concepts, cultural representations and policy applications. In Godela Weiss-Sussex & Franco Bianchini (Eds.), Urban mindscapes of Europe, European studies (Vol. 23, pp. 13–31). Amsterdam: Editions Rodopi.

- Brenner, N. (2004). New state spaces: Urban governance and the rescaling of statehood. Oxford University Press.

- Brettell, C. B. (2003). Bringing the city back in: Cities as contexts for immigrant incorporation. In N. Foner (Ed.), American arrivals: Anthropology engages the new immigration (pp. 163–119). School of American Research.

- Burchardt, M. (2017). Diversity as neoliberal governmentality: Towards a new sociological genealogy of religion. Social Compass, 64(2), 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0037768617697391

- Câmara Municipal de Lisboa (CML). (2010). Carta Estratégica de Lisboa 2010–2024 – Um compromisso para o futuro da cidade. Relatórios 1 a 6, Sumários executivos e Relatório-síntese [Lisbon Strategic Charter 2010–2024]. CML.

- Câmara Municipal de Lisboa (CML). (2018). Grandes Opções do Plano para a Cidade de Lisboa 2018/2021 (versão final aprovada em AML a 16 de janeiro 2018) [Major options for the Lisbon City Plan]. CML.

- Câmara Municipal de Lisboa (CML). (n.d.). Plano Municipal para a Integração de Imigrantes de Lisboa, 2 vols [Lisbon Municipal Plan for the Integration of Immigrants]. CML.

- Caponio, T., & Borkert, M. (2010). Introduction: The local dimension of migration policymaking. In T. Casponio, & M. Borkert (Eds.), The local dimension of migration policymaking (pp. 9–23). Amsterdam University Press.

- Caponio, T., & Ricucci, R. (2015). Interculturalism: A policy instrument supporting social inclusion? In R. Zapata-Barrero (Ed.), Interculturalism in cities, concept, policy and implementation (pp. 20–34). Edward Elgar.

- Cardoso, J., Borges, M., Pestana, P., & Quintela, P. (2011). Em Cima da Vila, Manobras no Porto, Setembro e Outubro, Porto.

- Carvalho, J. M. (2019). Immigrants’ acquisition of national citizenship in Portugal and Spain: The role of multiculturalism? Citizenship Studies, 24(2), 228–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2019.1707483.

- Costa, P. (2009). Estratégias para a Cultura em Lisboa. Câmara Municipal de Lisboa (CML).

- Costa, P., & Magalhães, A. (2014). Novos tempos. Nova vida. Novo centro? Dinâmicas e desafios para uma vida nova do centro histórico de Lisboa, in Revista Rossio, Gabinete de Estudos Olisiponenses/CML, n° 4.

- Council of Europe. (2014). Lisbon: Results of the Intercultural Cities Index, May 2014 – A comparison between more than 50 cities. https://rm.coe.int/16802ff6ce

- Cross, M., & Moore, R. (2002). Globalization and the new city: Migrants, minorities and urban transformations in comparative perspective. Palgrave.

- De Frantz, M. (2013). Culture-led urban regeneration: The discursive politics of institutional change. In M. Leary, & J. McCarthy (Eds.), Routledge companion to urban regeneration: Global constraints, local opportunities (pp. 526–535). Routledge.

- De Graauw, E., & Vermeulen, F. (2016). Cities and the politics of immigrant integration: A comparison of Berlin, Amsterdam, New York City, and San Francisco. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(6), 989–1012. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1126089

- Denters, B., & Rose, L. E. (2005). Towards local governance? In B. Denters, & L. E. Rose (Eds.), Comparing local governance. Trends and developments (pp. 46–62). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Emilsson, H. (2015). A national turn of local integration policy: Multi-level governance dynamics in Denmark and Sweden. Comparative Migration Studies, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-015-0008-5.

- Evans, G. (2001). Cultural planning. An urban renaissance? Routledge.

- Evans, G. (2005). Measure for measure: Evaluating the evidence of culture’s contribution to regeneration. Urban Studies, 42(5–6), 959–983. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500107102

- Favell, A. (2000). Philosophies of integration. Immigration and the idea of citizenship in France and Britain. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Florida, R. (2005). Cities and the creative class. Routledge.

- Foner, N., & Rath, J. (2014). New York and Amsterdam: Immigration and the new urban landscape. New York University Press.

- Fonseca, M. L. (2011). Imigração, Diversidade e Política Cultural em Lisboa. Working paper. Centro de Estudos Geográficos, UL.

- Gabinete de Apoio aos Bairros de Intervenção Prioritária (GABIP) – Almirante Reis. (2017). Estratégia Territorial de Desenvolvimento Social: Pena – Anjos – Almirante Reis, Lisboa [Territorial Strategy for Social Development: Pena – Anjos – Almirante Reis].

- Gebhardt, D. (2014). Building inclusive cities. Challenges in the multilevel governance of immigrant integration in Europe. Migration Policy Institute.

- Glick Schiller, N., & Çağlar, A. (2011). Downscaled cities and migrant pathways: Locality and agency without an ethnic lens. In N. G. Schiller, & A. Çağlar (Eds.), Locating migration: Rescaling cities and migrants (pp. 190–212). Cambridge University Press.

- Glick Schiller, N., & Çağlar, A. (2015). Displacement, emplacement and migrant newcomers: Rethinking urban sociabilities within multiscalar power. Identities, 23(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2015.1016520.

- Hoekstra, M. S. (2018). Governing difference in the city: Urban imaginaries and the policy practice of migrant incorporation. Territory, Politics, Governance, 6(3), 362–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2017.1306456

- Ireland, P. (1994). The policy challenge of ethnic diversity: Immigrant politics in France and Switzerland. Harvard University Press.

- Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. Random House.

- Jessop, B. (2002). Liberalism, neoliberalism, and urban governance: A state-theoretical perspective. Antipode, 34(3), 452–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00250

- Joppke, C. (2017). Is multiculturalism dead? Crisis and persistence in the constitutional state. Polity Press.

- Jørgensen, M. B. (2012). The diverging logics of integration policy making at national and city level. International Migration Review, 46(1), 244–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2012.00886.x

- Keith, M. (2005). After the cosmopolitan. Multicultural cities and the future of racism. Routledge.

- Koenig, M., & Guchtenaire, P. (2007). Political governance of cultural diversity. Democracy and human rights in multicultural societies. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- Kong, L. (2009). Making sustainable creative/cultural space: Shanghai and Singapore. Geographical Review, 99(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2009.tb00415.x

- Koopmans, R., Staham, P., Giugni, M., & Passy, F. (2005). Contested citizenship. Immigration and cultural diversity in Europe. University of Minnesota Press.

- Le Galés, P. (2011). Urban governance in Europe. What is governed? In G. Bridge, & S. Watson (Eds.), The new Blackwell companion to the city (pp. 747–758). Blackwell.

- Malheiros, J. (2011). Promoção da interculturalidade e da integração de proximidade. ACIDI.

- Mapril, J. (2010). Banglapara: imigração, negócios e (in)formalidades em Lisboa. Etnográfica, 14(2), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.4000/etnografica.284

- Mendes, L. (2018). The panacea of touristification as a scenario of post-capitalist crisis. In I. David (Ed.), Crisis, Austerity, and Transformation: How Disciplinary Neoliberalism Is Changing Portugal (pp. 25–48). Lexington Books.

- Mendes, M. M., Oliveira, N., & Mapril, J. (2020). Diversidades, Espaço e Migrações na Cidade Empreendedora. Dezembro, Estudo OM 66. ACM.

- Menezes, M. (2001). Mouraria: Entre o Mito da Severa e o Martim Moniz. Dissertation for obtaining the degree of Doctor FCSH/UNL, Lisboa.

- Menezes, M. (2012). Debatendo mitos, representações e convicções acerca da invenção de um bairro lisboeta. Sociologia. Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto Cultural, 69–95.

- Mouzelis, N. (1995). What went wrong with sociological theory? Routledge.

- Newman, K., & Ashton, P. (2004). Neoliberal urban policy and new paths of neighbourhood change in the American inner city. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 36(7), 1151–1172. https://doi.org/10.1068/a36229

- Nicholls, W., & Uitermark, J. (2013). Post-multicultural cities: A comparison of minority politics in Amsterdam and Los Angeles, 1970–2010. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 39(10), 1555–1575. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X2013.833686

- Nicodemos, J. C., & Ferro, L. (2018). Entre o fazer etnográfico e o fazer psicanalítico: reflexões sobre a ‘escuta’ da população sem-abrigo na rua de Cimo de Vila da Cidade do Porto. In Sociologia: Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto (pp. 92–115). https://ojs.letras.up.pt/index.php/Sociologia/article/view/4961.

- Oliveira, N. (2015). Producing interculturality. Repertoires, strategies and spaces. New Diversities (Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity), 17(2), 129–143.

- Oliveira, N., & Padilla, B. (2017). Integrating superdiversity in local governance. The case of Lisbon’s inner-city. Policy and Politics, 45(4), 605–622. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557317X14835601760639

- Padilla, B., & Azevedo, J. (2012). Territórios de diversidade e convivência cultural: considerações teóricas e empíricas. In Maria M. Mendes (Ed.), Sociologia, Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto (pp. 43–67). Número temático.

- Peck, J. (2005). Struggling with the creative class. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 29(), 740–770. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2005.00620.x.

- Penninx, R., Kraal, K., Martiniello, M., & Vertovec, S. (2004). Citizenship in European cities. Ashgate.

- Público. (2007, December 5). Viagem à volta do mundo na Rua do Cimo de Vila [Around the world in the Rua do Cimo de Vila]. Público. https://www.publico.pt/2007/12/05/jornal/viagem-a-volta-do-mundo-na-rua-do-cimo-de-vila-240261

- Raco, M. (2018). Critical urban cosmopolitanism and the governance of urban diversity in European Cities. European Urban and Regional Studies, 25(1), 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776416680393

- Raco, M., & Taşan-Kok, T. (2020). A Tale of Two Cities: Framing urban diversity as content curation in London and Toronto. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 12(1), 43–66. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v12.i1.6835

- Rocha, M. (2017). Dinâmicas Recentes e Urbanismo na Baixa do Porto. In Dissertação de Mestrado em Riscos, Cidades e Ordenamento do Território. FLUP.

- Rossi, U., & Vanolo, R. (2015). Urban neoliberalism. In James D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences, (2nd Ed.) (pp. 846–853). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.74020-7.

- Saeys, A., Van Puymbroeck, N., Albeda, Y., Oosterlynck, S., & Verschraegen, G. (2019). From multicultural to diversity policies: Tracing the demise of group representation and recognition in a local urban context. European Urban and Regional Studies, 26(3), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776419854503

- Santos, T., Soares, N., Ramalhete, F., & Vicente, A. (2017). Avenida Almirante Reis: diagnóstico urbano. Revista Estudo Prévio, 11, CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa [online].

- Schiller, M. (2015). Paradigmatic pragmatism and the politics of diversity. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 38(7), 1120–1136. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2014.992925

- Scholten, P. (2013). Agenda dynamics and the multi-level governance of intractable controversies: The case of migrant integration policies in the Netherlands. Policy Sciences, 46(3), 217–236.

- Seixas, J., Magalhães, A., & Costa, P. (2013). Os tempos novos do centro histórico de Lisboa. In R. Fernandes, & M. E. J. Alberto e Sposito (Eds.), A Nova Vida do Velho Centro nas Cidades Portuguesas e Brasileiras, CEGOT (pp. 63–92). FLUP.

- Soja, Edward. (2000). Postmetropolis. Critical Studies of Cities and Regions. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Somers, M. (2008). What’s political or cultural about political culture and the public sphere? Toward a historical epistemology of concept formation, in Genealogies of citizenship. Markets, statelessness, and the right to have rights (pp. 171–209). Cambridge University Press.

- Syrett, S., & Sepulveda, L. (2011). Realising the diversity dividend: Population diversity and urban economic development. Environment and Planning A, 43(2), 487–504. https://doi.org/10.1068/a43185

- Syrett, S., & Sepulveda, L. (2012). Urban governance and economic development in the diverse city. European Urban and Regional Studies, 19(3), 238–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776411430287

- Tillie, J., & Slijper, B. (2007). Immigrant political integration and ethnic civic communities in Amsterdam. In S. Benhabib, & I. Shapiro (Eds.), Identities, allegiances, and affiliations (pp. 206–225). Cambridge University Press.

- Uitermark, J. (2012). Dynamics of power in Dutch integration Politics. From accommodation to confrontation. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Wood, P. (2012). Challenges of governance in multi-ethnic cities. In H. K. Anheier, & Y. R. Isar (Eds.), Cultures and globalization: Cities, cultural policy and governance (pp. 44–60). Sage.

- Wood, P., & Landry, C. (2008). The intercultural city: Planning for diversity advantage. Earthscan.

- Zapata-Barrero, R. (2014). The limits to shaping diversity as public culture: Permanent festivities in Barcelona. Cities, 37, 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.11.007

- Zapata-Barrero, R. (2015). Introduction: Framing the intercultural turn. In Zapata-Barrero (Ed.), Interculturalism in cities: Concept, policy and implementation (pp. viii–xvi). Edward Elgar.