ABSTRACT

Hepatitis B is the leading cause of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma worldwide. The incidence of HBV infection has significantly decreased with hepatitis B vaccination. Hepatitis B vaccine is administered to children at 0, 1 and 6 months of age according to the national schedule. There is a high rate of protective antibody (anti-HBs) development after hepatitis B vaccination. We conducted the study to investigate how the hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) positivity rates and the titers change over time in childhood following vaccination. Patients who presented at the general pediatric outpatient clinic of Yenimahalle Education and Training Hospital and the HBsAg and anti-HBs titers were tested for any reason between July 2011 and May 2018 were retrospectively evaluated. The cutoff level for protection by the anti-HBs titer was accepted as ≥10 mIU/mL with lower levels indicating no protection. Anti-HBs positivity was compared by age group. Anti-HBs levels were studied in 4326 children. The mean age of the included in the study was 127 ± 62 months. A protective anti-HBs level (≥10 mIU/mL) was present in 2292 children (69.2%). The highest anti-HBs antibody positivity rate was in the under 3 years’ age group. The positivity rate significantly decreased after age 7 years. The HBsAg level was determined in all children in the study and five had a positive result. In conclusion, our study found that the anti-HBs positivity rate and the anti-HBs level decreased with age. However, the anti-HBs antibody result remained positive in more than half of the children.

Introduction

Hepatitis B is the leading cause of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 257 million people were living with chronic hepatitis B infection and that hepatitis B resulted in an estimated 887,000 deaths in 2015.Citation1 The hepatitis B vaccine and the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine are the only vaccines that prevent cancer. The incidence of HBV infection has significantly decreased with hepatitis B vaccination.Citation2 Turkey is an area of intermediate endemicity for hepatitis B and the reported prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) is 2.3–4%.Citation3 In Turkey, the inclusion of the hepatitis B vaccine in the national vaccination schedule for all children and risk groups started in 1998. The hepatitis B vaccine is administered to children at 0, 1 and 6 months of age according to this schedule. HBV vaccination is started before hospital discharge because the risk of developing HBV infection shows an inverse relationship with the age at which the infection is acquired and a newborn is at the highest risk of developing chronic HBV infection if the virus is acquired perinatally.

There is a high rate of protective antibody (anti-HBs) development after hepatitis B vaccination. Routine anti-HBs testing after vaccination is therefore not recommended. However, such testing after vaccination is completed has been recommended for hemodialysis patients, those with immunosuppressive conditions, and also subjects with a risk of accidental HBV exposure such as health-care workers and those with HBsAg-positive sexual partners.Citation4

The vaccine non-responsiveness rate in a healthy population is reported as 4–10% but this rate is higher in patients with an autoimmune condition, type 1 diabetes (T1DM), celiac disease (CD), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), obesity, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients in addition to those undergoing dialysis .Citation5-7 It is also known that the protective antibody titers may gradually decrease and even disappear in some cases. Therefore, we conducted this study to investigate how the hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) positivity rate and the titers changed over time in childhood following vaccination.

Materials and methods

The hepatitis B vaccine is administered to children at 0, 1 and 6 months of age in Turkey. The first dose is administered to newborns before hospital discharge, and vaccination at the 1st and 6th month is then performed by the family physician. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and anti-HBs tests can be requested for reasons such as the curiosity of the families, before internship in high schools of health science, and before surgery. This study was conducted in Yenimahalle Education and Training Hospital. In the current study, patients who presented at the general pediatrics outpatient clinic whose HBsAg and anti-HBs titers were checked for any reason between July 2011 and May 2018, were retrospectively evaluated. Only children aged 7 months or older and who had completed three doses of HBV vaccine were included because the last vaccination dose is normally administered at 6 months of age.

The anti-HBs titer, HBsAg test result, anti-HBc (total) (antibody to HBcAg), and also the age, sex, vaccination history, and any history of an HBV-infected person in the household were recorded from the medical database of the hospital. The cutoff level for protection by the anti-HBs titer was accepted as ≥10 mIU/mL with lower levels indicating no protection. An anti-HBs level of ≥10 mIU/mL was considered to indicate a vaccine response. The last anti-HBs test result was included in the study for patients who had multiple anti-HBs titer results from different times.

Children were grouped according to age as 7 months to 3 years, 4–7 years (48–95 months), 8–11 years (96–143 months), 12–14 years (144–179 months), and 15 years and over (180–227 months). Anti-HBs positivity was compared by age group. Children who had a positive HBsAg test were accepted as being infected with HBV. Patients who had a history of vaccine refusal or incomplete vaccination with HBV vaccine (less than 3 doses) or who received booster doses in addition to primary vaccination were excluded from the study. Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Yenimahalle Education and Training Hospital.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median, minimum-maximum. The Chi-square test was used for comparative analyses of the categorical variables between independent groups. Quantitative anti-HBs titers are presented as mean concentrations. Anti-HBs titers of <1 mIU/mL were recorded as 1 mIU/mL for the calculations. Scatter Plot analysis was used to show the relationship between age and quantitative Anti HBs titers.

Results

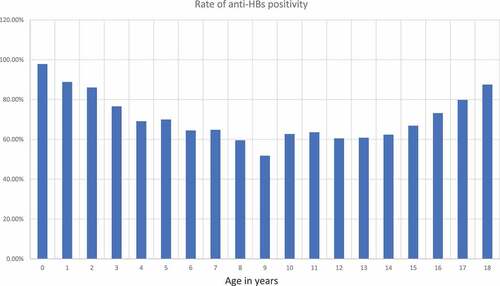

Anti-HBs levels were studied in 4326 children. The mean age of those included in the study was 127 ± 62 months. Males made up 51.7% and females 48.3% of the children included in the study. A protective anti-HBs level (≥10 mIU/mL) was present in 2292 children (69.2%). presents the anti-HBs positivity rate by age group. The highest anti-HBs antibody positivity rate was in the under 3 years age group. The positivity rate significantly decreased after 7 years of age. There was no statistically significant difference between the 8–11 years and 12–14 years age groups. There was a statistically significant increase in the percentage of subjects with a protective antibody level in the >15 years age group. shows the anti-HBs positivity rates and indicates the quantitative anti-HBs titers by age. There is a weak, positive, linear correlation between age and anti-HBs titers.

Table 1. The number and percentage of children with anti-HBs titer ≥10 mIU/mL by age groups and the number and percentage of children with anti-HBs titer ≥10 mIU/mL by sex

The HBsAg level was evaluated in all children included in the study and five had a positive result. The anti-HBc (total) level was evaluated in 107 children and was positive in two subjects, both were also positive for HBsAg. A history of chronic HBV disease in the household was positive in 150 children. A history of vaccine refusal was not present in the medical data of any children. presents the rate of having protective antibodies by sex.

Table 2. Summary of literature reporting the duration of hepatitis B immunity after primary vaccination

Discussion

In this study, we found that anti-HBs seropositivity decreased over time after primary vaccination, and both the anti-HBs seropositivity rate and the antibody titer increased in the 15 years and older age group.

Perinatal transmission from an HBV-infected mother to the newborn is the most important HBV transmission route in childhood. The rate of such transmission can be up to 70–90% in the absence of prophylaxis with the HBV vaccine and hepatitis B immunoglobulin. The age at acquisition is the most important determinant for progression to chronic infection after acute infection because 90% of infants who are infected perinatally develop chronic HBV infection. The use of HBV vaccination at birth together with the administration of hepatitis B immunoglobin has largely prevented mother-to-newborn transmission and infection in early childhood. Another expectation from vaccination is ensuring protection in adolescents and adults when the risk of HBV infection increases. Most acute HBV infections in the United States have been reported to occur during adolescence or adulthood, and to be linked to sexual exposure or injection drug use.Citation16 The duration of protection provided by the HBV vaccine is therefore important.

The seroconversion rate after HBV primary vaccination is ≥96% but protective anti-HBs titers are reported to decrease gradually over time.Citation3,Citation8 Several studies in the literature investigated long-term HBV immunity after primary vaccination ().Citation8-15,Citation20-24 A study monitoring 334 children for 3151 person-years (median, 10 years per child) found that anti-HBs concentrations dropped rapidly, with values of 10 mIU/mL or higher being found in 47%, 19%, and 8%, in children aged 2, 5, and 10 years, respectively.Citation8 A study including 20,634 individuals who were vaccinated at childhood reported the rate of negative anti-HBs results gradually increased to 66.7% after 15 years, demonstrating that protective antibody titers remained in only one third of vaccinated subjects.Citation9 Another study on 729 children reported that 84.4% of children had a protective anti-HBs level at 1 year of age, and this was valid for only 39.1% of children at 5–7 years of age.Citation10 These data demonstrate that antibody levels decrease gradually over time. We similarly found that the antibody titer decreased with age but the anti-HBs titer remained at a protective level at a higher rate than reported in the literature in similar age groups, even in the age group where the positive rate was found to be lowest in our study. The vaccine responsiveness rate has been reported to be lower in patients with autoimmune conditions, T1DM, CD, RA, obesity, IBD, and SLE and those on dialysis.Citation5-7 However, we are unable to comment on this matter because we did not investigate the underlying diseases in our study. It has been reported that the immunogenicity of the HBV vaccine varies according to the ethnic origin, and the vaccine is less immunogenic in various ethnic groups.Citation17,Citation18 In our study, we could not relate our results to ethnic origin, as there was no other ethnic group that we compared. Responsiveness to HBV vaccination has been reported to be more common in females.Citation19 We similarly found higher anti-HBs positivity rates in females. We cannot explain the higher general positivity rates in our study compared with the literature, only with the effect of sex, because we had a higher number of male subjects than female subjects.

A decrease in the antibody titer to a level below 10 mIU/mL may not always mean that protection is no longer present. An amnestic response with a high antibody titer response to a single booster dose of HBV vaccine together with an anti-HBs titer below 10 mIU/mL after primary vaccination has been interpreted as continuing immunologic memory. It has been reported that half of all children whose antibody titer became negative after the primary vaccination had a high titer antibody response to a single-dose booster that was administered 15 years after the primary series.Citation16 Another study found that only 41% of those who initially responded to the vaccine (primary responders) had a protective level of anti-HBs at age 60 months, but the entire group cohort had an anti-HBs response with a high titer after a booster dose.Citation11 A high antibody response after a booster dose has been reported up to 20 years after the primary vaccination.Citation12 We did not investigate the amnestic response in the current study. It has been reported that until the age of 20 years, anti-HBs seropositivity steadily decreases over time after the primary vaccination, but the rate of anti-HBs seropositivity increased in the 20–23 years’ age group, possibly due to natural boosting (natural exposure to HBV).Citation9 We similarly found a significant increase in both the anti-HBs positivity rate and the anti-HBs levels in the 15 years and older age group, when compared with the other groups, supporting natural exposure to HBV. More evidence of the persistence of immune memory is the lack of an increase in the prevalence of HBV infection with decreasing anti-HBs levels. A study conducted in a population with a high prevalence (10%) of chronic HBV infection found no infections in vaccinated children although the exposure risk continued, including the 60% of vaccinated subjects whose anti-HBs antibody became negative over time. The authors concluded that HBV vaccination beginning soon after birth provided long-term protection for children, even when the antibody titer later decreased.Citation11 Another study found that transient anti-HBc appeared in a small percentage of children during a median follow-up duration of 10 years among infants immunized with the HBV vaccine starting at birth but none of these subjects had hepatitis B surface antigen positivity or developed chronic HBV infection.Citation8 There are only a few reports of HBV breakthrough infection in vaccinated immunocompetent persons in the literature. A few reported patients have developed anti-HBs antibodies and then lost them, followed by the development of chronic HBV infection.Citation13-15 In the current study, a total of five subjects were found to be HBsAg positive, indicating a chronic HBV infection. There was no history of chronic HBV infection in their mother and none had refused vaccination. These patients can therefore be considered as having breakthrough infections. However, we are unable to provide a definite opinion on these patients because of the retrospective nature of the study.

The presence of anti-HBs antibodies is not the only marker of continued immunity. Cellular immunity following HBV vaccination has been investigated in several studies. The presence of HBsAg-specific T cells in the circulation after primary vaccination of HBV, indicating a specific immune response, has also been reported. The presence of functional HBsAg-specific memory T and B cells has been detected in some vaccinated individuals who subsequently lost the antibodies.Citation20,Citation25,Citation26 Thanks to cellular immune memory, the protective capacity against HBV may continue even after the anti-HBs antibodies developing following vaccination are gone.

The limitations of our study is that our study is retrospective and that we accessed patient information from the medical database of the hospital. Incomplete vaccination history or vaccine refusal information of some patients may not be entered to the medical database of the hospital. Another limitation is that we did not investigate whether the participants had underlying diseases, given that certain diseases negatively affect the vaccine response.

In conclusion, our study found that the anti-HBs positivity rate and the anti-HBs level decreased with age. However, the anti-HBs antibody result remained positive in more than half of the children. Taking into account our results and also considering that antibody positivity is not the only indicator of ongoing immunity after vaccination and that breakthrough hepatitis B infection is reported relatively rarely in the vaccinated population, we want to emphasize that immunity may continue even when the anti-HBs antibody result is negative.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

There is not any financial interest or benefit that has arisen from the direct applications of our research.

References

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b [accessed 2021 March 22].

- Stramer SL, Wend U, Candotti D, Foster GA, Hollinger FB, Dodd RY, Allain J-P, Gerlich W. Nucleic acid testing to detect HBV infection in blood donors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:236–47. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1007644.

- Van Den Ende C, Marano C, Van Ahee A, Bunge EM, De Moerlooze L. The immunogenicity of GSK’s recombinant hepatitis B vaccine in children: a systematic review of 30 years of experience. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2017;16:789–809. doi:10.1080/14760584.2017.1338569.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Hepatitis B. In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, editors. Red book: 2018 report of the committee on infectious diseases. 31st ed. Itasca (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 2018. p. 401–28.

- Liu F, Guo Z, Dong C. Influences of obesity on the immunogenicity of hepatitis B vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13:1014–17. doi:10.1080/21645515.2016.1274475.

- Mormile R. Hepatitis B vaccine non response: a predictor of latent autoimmunity? Med Hypotheses. 2017;104:45–47. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2017.05.020.

- Saco TV, Strauss AT, Ledford DK. Hepatitis B vaccine nonresponders: possible mechanisms and solutions. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121:320–27. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2018.03.017.

- Dentinger CM, McMahon BJ, Butler JC, Dunaway CE, Zanis CL, Bulkow LR, Bruden DL, Nainan OV, Khristova ML, Hennessy TW, et al. Persistence of antibody to hepatitis B and protection from disease among Alaska natives immunized at birth. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:786–92. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000176617.63457.9f.

- Klinger G, Chodick G, Levy I. Long-term immunity to hepatitis B following vaccination in infancy: real-world data analysis. Vaccine. 2018;36:2288–92. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.03.028.

- Yazdanpanah B, Safari M, Yazdanpanah S. Persistence of HBV vaccine’s protection and response to hepatitis B booster immunization in 5- to 7-year-old children in the Kohgiloyeh and Boyerahmad Province, Iran. Hepat Mon. 2010;10:17–21.

- Williams IT, Goldstein ST, Tufa J, Tauillii S, Margolis HS, Mahoney FJ. Long term antibody response to hepatitis B vaccination beginning at birth and to subsequent booster vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:157–63. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000050463.28917.25.

- Cadavid-Betancur DA, Ospina MC, Hincapié-Palacio D, Bernal-Restrepo LM, Buitrago-Giraldo S, Perez-Toro O, Santacruz-Sanmartín E, Lenis-Ballesteros V, Almanza-Payares R, Díaz FJ. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and factors potentially associated in a population-based study in Medellin, Colombia. Vaccine. 2017;35:4905–12. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.084.

- Wainwright RB, Bulkow LR, Parkinson AJ, Zanis C, McMahon BJ. Protection provided by hepatitis B vaccine in a Yupik Eskimo population–results of a 10-year study. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:674–77. doi:10.1093/infdis/175.3.674.

- O’Halloran JA, De Gascun CF, Dunford L, Carr MJ, Connell J, Howard R, Hall WW, Lambert JS. Hepatitis B virus vaccine failure resulting in chronic hepatitis B infection. J Clin Virol. 2011;52:151–54. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2011.06.020.

- Poorolajal J, Mahmoodi M, Majdzadeh R, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Haghdoost A, Fotouhi A. Long-term protection provided by hepatitis B vaccine and need for booster dose: a meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2010;28:623–31. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.068.

- Hammitt LL, Hennessy TW, Fiore AE, Zanis C, Hummel KB, Dunaway E, Bulkow L, McMahon BJ. Hepatitis B immunity in children vaccinated with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine beginning at birth: a follow-up study at 15 years. Vaccine. 2007;25:6958–64. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.06.059.

- Öm K, Menart C, Theodore J, Kremer C, Hens N, Koek GH, Oude Lashof AML. Ethnicity and response to primary three-dose hepatitis B vaccination in employees in the Netherlands, 1983 through 2017. J Med Virol. 2020;92:309–16. doi:10.1002/jmv.25610.

- Wang LY, Lin HH. Ethnicity, substance use, and response to booster hepatitis B vaccination in anti‐HBs‐seronegative adolescents who had received primary infantile vaccination. J Hepatol. 2007;46:1018–25. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2007.01.022.

- Li M, Zhao Y, Chen X, Fu X, Li W, Liu H, Dong Y, Liu C, Zhang X, Shen L, et al. Contribution of sex-based immunological differences to the enhanced immune response in female mice following vaccination with hepatitis B vaccine. Mol Med Rep. 2019;20:103–10. doi:10.3892/mmr.2019.10231.

- Lu CY, Ni YH, Chiang BL, Chen PJ, Chang MH, Chang LY, Su IJ, Kuo HS, Huang LM, Chen DS, et al. Humoral and cellular immune responses to a hepatitis B vaccine booster 15-18 years after neonatal immunization. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1419–26. doi:10.1086/587695.

- Bruce MG, Bruden D, Hurlburt D, Zanis C, Thompson G, Rea L, Toomey M, Townshend-Bulson L, Rudolph K, Bulkow L, et al. Antibody levels and protection afer hepatitis B vaccine: results of a 30-year follow-up study and response to a booster dose. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jul 1;214(1):16–22. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiv748.

- Belloni C, Pistorio A, Tinelli C, Komakec J, Chirico G, Rovelli D, Gulminetti R, Comolli G, Orsolini P, Rondini G. Early immunisation with hepatitis B vaccine: a five-year study. Vaccine. 2000;18:1307–11. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00414-4.

- Alfaleh F, Alshehri S, Alansari S, Aljeffri M, Almazrou Y, Shaffi A, Abdo AA. Long-term protection of hepatitis B vaccine 18 years afer vaccination. J Infect. 2008;57:404–09. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2008.08.008.

- Bialek SR, Bower WA, Novak R, Helgenberger L, Auerbach SB, Williams IT, Bell BP. Persistence of protection against hepatitis B virus infection among adolescents vaccinated with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine beginning at birth: a 15-year follow-up study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:881–85. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e31817702ba.

- Brunskole Hummel I, Huber B, Wenzel JJ, Jilg W. Markers of protection in children and adolescents six to fourteen years after primary hepatitis B vaccination in real life: a pilot study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35:286–91. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000000994.

- Bauer T, Jilg W. Hepatitis B surface antigen-specific T and B cell memory in individuals who had lost protective antibodies after hepatitis B vaccination. Vaccine. 2006;24:572–77. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.058.