ABSTRACT

Background

Women are currently facing a tremendous threat of cervical cancer globally. Social media health campaigns have the potential to shape public health behaviors. This study explores the effects of cervical-cancer-related fear appeal messages with social cues on social media using the extended parallel processing model (EPPM).

Method

We use a 2 (threat: present vs. absent) × 2 (efficacy: present vs. absent) × 2 (social cues: high vs. low) factorial experimental design to examine the effects of fear appeal messages with social cues on behavioral intention to receive the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination.

Results

There was a significant main effect of threat on the intention to receive HPV vaccination. Additionally, a significant three-way interactive effect among threat, efficacy, and social cues was detected.

Conclusion

Women exposed to threat messages had a higher intention of HPV vaccination compared to those who were exposed to non-threat messages. Furthermore, with the low number of likes, women who were exposed to messages containing both threat and efficacy tended to have the highest intention of HPV vaccination.

Practice Implications

When conducting fear appeal campaigns on social media, the side effects of number of likes should be recognized. For vaccination promotion campaigns, the efficacy information should be more specific and audience-centered.

Introduction

Cervical cancer is one of the most common and invasive cancers among women.Citation1There were 569,000 new cases of cervical cancer and 311,000 deaths related to cervical cancer worldwide in 2018.Citation2 In China, 106,430 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer annually, accounting for about 19.71% of the global incidents.Citation3,Citation4 Compared with other cancers, cervical cancer ranked third in instances of cancers among Chinese women aged 15 to 44 in 2019.Citation2

Cervical cancer is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, and currently, the HPV vaccination is the most effective means of prevention.Citation5 HPV vaccinations in mainland China were first approved in 2016. However, due to scant knowledge and high price of the HPV vaccination, only about 3% of Chinese women have been vaccinated until 2019.Citation6–8 It is, therefore, imperative and urgent to promote the HPV vaccination among Chinese women.

In the past decade, social media has become a platform in which a large amount of health information is generated and exchanged.Citation9–12 Additionally, many social media sites have been used for health promotion and campaigns.Citation13,Citation14 Extant research has found that the effectiveness of health campaigns on between traditional and social media did not differ.Citation15 However, some studies have found that health campaign messages from different sources might affect readers’ credibility perceptions, which in turn, could influence the effectiveness of health campaigns.Citation16,Citation17 In addition, compared to the content in traditional media, social media content includes not only texts and images, but also various social cues with interactive implications hidden behind them, such as user ratings and numbers of friends, likes, comments, and reposts. Previous studies have indicated that social cues could enrich the meaning of the texts and images, which may alter its effectiveness.Citation15 However, little research has been conducted to examine the roles of social cues in social media health campaigns.Citation18 The current study seeks to develop the extended parallel process model (EPPM) with social cues to examine the effects of fear appeals and social cues as well as their interactive effects on the intention of Chinese women to receive the HPV vaccination.

Theoretical model and hypothesis development

Extended parallel process model (EPPM)

Witte proposed the extended parallel process model (EPPM), which provides a persuasive message design framework for deciding when fear appeals can be used and how they should be constructed.Citation19 The model divides the cognitive process that addresses fear appeals into two stages – the threat appraisal and the efficacy appraisal.

In the face of threat as an external stimulus, individuals appraise the severity of and their susceptibility to the stimulus.Citation19 Severity refers to the magnitude or seriousness of a threat, i.e., the anticipated negative consequences. Susceptibility refers to the expected possibility of experiencing the threat, i.e., the risk of harm perceived by individuals. These two aspects subsequently form the perceived threat, which determines the motivation to respond to fear-arousing information.Citation20 If the threat is perceived as negligible, then fear cannot be stimulated, and the individual loses the motivation to further process the information.Citation14 In contrast, if the fear is stimulated, then efficacy appraisal would take place. In other words, when the targeted audience is faced with a threat, fear guides them to appraise whether there are possible measures to be taken to protect them from it.

Efficacy appraisal involves response efficacy and self-efficacy: the former refers to the effectiveness of the recommended response in the aversion to the threat, i.e., whether the suggested measure is feasible, whereas the latter refers to the capacity to perform behaviors recommended by messages, i.e., whether the suggested measure could be easily implemented.Citation14

These two aspects could form individual’s efficacy perception. In this appraisal, if the individual believes that the recommended measures provided by the stimulus are effective and he or she has the capability to take such a measure, the person will engage in danger control and perform the recommended behavior in order to reduce the threat.Citation21–23 At this point, the individual accepts the recommended strategy and actively responds to the danger. On the contrary, if the individual believes that the strategy would not be effective in helping to cope with the potential threat, or if the individual does not have the capability to perform the recommended health-oriented actions, defensive behaviors are adopted, placing the person into a passive mind-set, whereby no action is taken.

Many studies of fear appeals have documented that EPPM-based messages can enhance recipients’ perceived threat and perceived efficacy, thereby facilitating intentions to perform certain health protective behaviors.Citation10,Citation24,Citation25 Specifically, both threat and efficacy have main effects and interaction effects. Higher levels of both threat and efficacy, in various combinations, is more persuasive.Citation10,Citation26 In other words, individuals who receive messages including both threat and efficacy components have a higher degree of behavioral intention than messages containing only one or no component.

Some studies have also used the EPPM to design persuasive messages in promoting vaccination.Citation17,Citation27,Citation28 These messages highlight the risk of disease (i.e., threat) and provide a way to get vaccinations (i.e., efficacy). This has been found to be effective in increasing the intention to receive vaccination.

Social cues in social media

In addition to the message itself, social media content usually includes some system- and user-generated cues such as the number of followers, likes, comments, and reposts.Citation29 SundarCitation30 indicated that these cues were design features of technologies that can highlight the underlying affordances and serve as triggers for cognitive heuristics that affect people’s impressions of the quality and credibility of the underlying information. Many studies have found that social cues not only can direct attention to certain topics, but also influence their perceived validity and trustworthiness.Citation31,Citation32

The most common social cues in social media include the number of comments, reposts, and likes. They can serve as indicators of information engagement.Citation33 For example, reposting means the audience has read the original post, whereas commenting involves more cognitive efforts on the part of the audience given that it generally requires entering new content that adds value to the original post, and liking represents the popularity of a message.Citation34 In some studies, the number of likes was used as a proxy for social endorsement, indicating the level of public agreement with a certain message.Citation35,Citation36 Several studies have revealed that the more popular a message (i.e., receives a greater number of likes), the more valuable the message is believed to be. In other words, messages with a greater number of likes tend to affect the recipients more easily and deeply.

Furthermore, studies have found that the number of likes usually plays a significant role in social media health campaigns. Borah and Xiao examined the perceived credibility of social media health information and found that the gain-frame messages with a greater number of likes had a higher level of perceived credibility.Citation36 Jin, Phua, and Lee examined the effects of user-generated messages on attitudes toward breast feeding among female college students.Citation37 They found that strategic messages with a greater number of likes tended to have a higher level of perceived credibility and produce positive attitudes. However, no study has examined the interactive effects between social cues and fear appeals on behavioral intentions.

Based on the above literature review, this research proposes the following hypotheses and question:

H1: Women exposed to information with threat will have a greater intention to be vaccinated against HPV.

H2: Women exposed to information with efficacy will have a greater intention to be vaccinated against HPV.

H3: Women exposed to information with both threat and efficacy will have the highest intention of being vaccinated against HPV.

H4: Women exposed to messages with a greater number of likes will have a greater intention of being vaccinated against HPV.

RQ1: How do threat, efficacy, and the number of likes interact to affect the intention to receive a vaccination against HPV among Chinese women?

Materials and methods

Participants

A snowball sampling method was used to recruit Chinese female participants through the Internet. This method has also been used in previous experimental studies.Citation14,Citation38 Specifically, the authors first sent the link of the experiment to friends and acquaintances via social media and e-mail, and then asked them to share it by forwarding the link to their friends and acquaintances. A total of 478 women aged 16–45 years old (M= 23.05, SD = 4.52) who had never received an HPV vaccine were selected, due to the higher risk of cervical cancer among women older than 16 and their qualification for all three types of HPV vaccine. In addition, in order to obtain the general attitude of the females toward cervical cancer and HPV vaccination, individuals who were studying or working in the related fields of medicine, biomedicine and health care were excluded from this experiment.

Experiment design

This study used Weibo as the experimental context. Serving as a Chinese version of Twitter, Weibo has become a popular social media platform in China since it was launched in 2009.Citation29 The study was a 2 (threat: present vs. absent) × 2 (efficacy: present vs. absent) × 2 (social cues: high vs. low) factorial experiment that used a between-subjects design. All participants were randomly assigned to one of eight experimental groups. After being exposed to the stimulus, participants were asked to indicate their intention to receive the HPV vaccination.

Procedure

One hyperlink of the eight available was sent to participants via social media. An online informed consent form was presented for the participants to complete. Participants were then randomly exposed to one of the eight posters (i.e., the stimulus) in the web-based questionnaire, which automatically assigned the stimuli to the participants randomly. Participants could only enter the final stage of the questionnaire after viewing the stimulus picture. They were then asked to indicate the perceived threat and efficacy as well as their intention to receive the HPV vaccination.

Stimuli

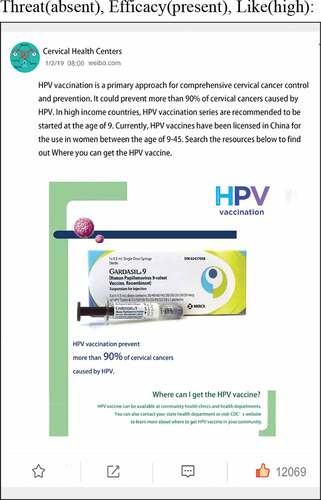

Posters presenting eight different versions of Weibo posts were created. All the stimulus posters first introduced cervical cancer and the HPV vaccination. In addition, the posters contained different levels of threat, efficacy, and social cues. Social cues were operationalized by manipulating the number of likes (high vs. low). A total of 12,069 likes were used in the high-like condition, and 2 were used in the low-like condition (see Appendix).Citation32,Citation36,Citation37 The number of likes was adjusted after pilot testing.

Measures

First, in order to check randomization, previous studies were followed.Citation39,Citation40 Demographic variables were measured, which included age (M= 23.05, SD = 4 52) and education level (Mdn = 3 undergraduate). Additionally, social media use was measured by asking participants to indicate the frequency of their daily social media use within a six month period using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all” to 7 = “very frequently”) (M = 6.65, SD = .88). Two items were used to measure prior knowledge based on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly unfamiliar” to 7 = “strongly familiar”):“To what extent are you familiar with 1) cervical cancer and 2) HPV vaccines” (M = 3.78, SD = 1.29, Pearson’ r = .83).

The Risk Behavior Diagnosis Scale (RDBS) was modified and used to measure the threat and efficacy levels of the stimuli.Citation41 All measures used a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”).

Threat

Three items were initially used to measure susceptibility. For example, the poster shows that I am at risk for experiencing cervical cancer. The three items on the severity scale. For example, the poster shows that cervical cancer is a serious threat. Scale reliability was measured for all six items (M= 4.70, SD = 1.38, Cronbach’s α = .85).

Efficacy

Response efficacy was measured by three items. For example, the poster shows that the HPV vaccine is important to limiting the spread of HPV. Three items were used to measure self-efficacy. For example, the poster teaches me how to begin HPV vaccination step by step. Scale reliability was measured for all six items (M= 5.04, SD = 1.28, Cronbach’s α = .87).

Behavioral intentions

Three items from a previous studyCitation42 were modified to measure HPV prevention intentions: a) I intend to begin the HPV vaccination; b) I will try to begin the HPV vaccination; and c) I plan to begin the HPV vaccination (M= 5.59, SD = 1.19, Cronbach’s α = .95).

Data analysis

Basic descriptive analysis, t-tests, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) through software SPSS 23.0 were conducted to check randomization and manipulation as well as address the hypotheses and research questions.

Randomization checks

Following previous studies,Citation43,Citation44 we conducted ANOVA to compare demographic variables, social media use and prior knowledge between different message conditions. The results revealed that participants in eight groups did not significantly differ in these variables (Fage(7, 470) = 0.46, p = .86; Feducation(7, 470) = 0.49, p = .84; Fsocial media use (7, 470) = 1.81, p = .08;Fknowledge = 0.99, p = .44), suggesting that randomization was successful.

Manipulation checks

Since eight stimuli were used in this study, manipulation checks were conducted to ensure participants’ correct perception of the threat and efficacy levels of the stimuli. Specifically, the levels of threat and efficacy were tested. We used independent sample t-tests to examine participants’ perception of threat and efficacy in all instances. The results showed that perceptions of stimulus with threat (M= 5.23, SD = 0.94) scored significantly higher than stimulus without threat (M= 4.16, SD = 1.53), t(478) = 9.18, p< .01. Similarly, the results revealed that perceptions of stimulus with efficacy (M= 5.52, SD = 0.85) scored significantly higher than stimulus without efficacy (M= 4.57, SD = 1.45), t(478) = 8.77, p< .01 (see ). As such, participants’ perceptions of the threat and efficacy of the stimuli were consistent with the levels of threat and efficacy created for this study; the manipulation was successful.

Table 1. Manipulation checks

Results

To assess the hypotheses and research question, we conducted a three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the effects of stimulus messages with different numbers of likes on the participants’ behavioral intention to receive the HPV vaccination. The ANOVA model revealed a significant main effect of threat on participants’ intention to receive HPV vaccination, which indicated that participants exposed to threat messages have higher intention to receive the HPV vaccination (M= 5.72, SD = 1.12), while those who are exposed to non-threatening messages have a lower intention to receive the HPV vaccination (M= 5.38, SD = 1.21), F (1, 465) = 11.74, p < .001, partial η2 = .02. Thus, the results supported H1. However, the models showed that the main effects of efficacy and likes on behavioral intention were not significant. Thus, the results failed to support H2 and H4. In addition, H3 proposed that there was a two-way interaction effect between threat and efficacy, but the analysis demonstrated that this interaction on behavioral intentions was not significant, F (1, 465) = .20, p = .65, partial ηp2 < .00. Thus, H3 was not supported.

Furthermore, RQ1 asked how threat, efficacy, and the number of likes interact to affect the intention to receive vaccination against HPV. Our findings showed that there was a significant three-way interaction (F (1, 465) = 3.04, p < .05, partial η2 = .01). When the number of likes is high, women who are exposed to threat messages without efficacy had the higher intention to receive the HPV vaccination than those who were exposed to other messages. However, with a low number of likes, those who were exposed to messages containing threat and efficacy tended to have a higher intention to receive the HPV vaccination than other messages (See ). The ANOVA test results are displayed in . The significant interactions are depicted in .

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for intention to receive HPV vaccination

Table 3. Threat × Efficacy × Likes factorial analysis of variance for intention to receive HPV vaccination

Discussion

Through a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial experiment, this study explored the causal relationship between the provision of fear appeal messages on cervical cancer and the intention to receive the HPV vaccination under two different levels of social cues based on the EPPM . First, the main effects of threat and efficacy were examined. The results indicated that threat had a significant main effect on HPV vaccination intention, which was consistent with the results of previous studies.Citation11,Citation40,Citation45,Citation46 According to the EPPM, when exposed to messages with a high level of threat, people are more likely to accept the recommended health advice to control the potential danger. However, the findings revealed a non-significant main effect of efficacy. It is plausible that the efficacy information on the stimulus picture only provided a way to start the HPV vaccination. Many recipients may be unclear about when people should get the HPV vaccine, how many HPV vaccine injections people should take, and how much the HPV vaccine costs.Citation47 Thus, while the messages containing efficacy could increase individuals’ general perceive efficacy of HPV vaccination, the intention to receive the HPV vaccination was not significantly enhanced.

In addition, the study detected a significant three-way interaction among threat, efficacy, and social cues. The results revealed that messages including threat and efficacy had the best persuasive effect only when the number of likes was low, which is in line with the EPPM. This can be explained by the heuristic-systematic model (HSM). According to Chaiken’s HSM,Citation43 an individual will use either heuristic or systematic information processing to evaluate messages in order to arrive at judgments and attitudes.Citation44Serving as social cues, a high number of likes highlights the popularity of online messages and leads people to focus on others’ agreement and endorsement to the messages, rather than the message content itself. In other words, when the number of likes is high, people tend to apply the heuristic information processing to assess the message, leading to the difficulty in behavioral change.Citation34

On the contrary, with a low number of likes, people are less likely to process the heuristic cues in the message. Individuals tend to invest more cognitive resources to systematically evaluating the statements and arguments in the messages.Citation26,Citation48,Citation49 In this regard, people will consider more about how to go to the hospitals or medical centers for the HPV vaccination behind the efficacy information presented on the messages. Moreover, individuals’ cognitive thinking could be motivated to understand the benefits of the HPV vaccination clearly and to eliminate psychological barriers; thus finally enhancing individuals’ behavioral intention to receive the vaccination. Therefore, with a low number of likes, messages with both threat and efficacy components are more effective in promoting the HPV vaccination.

Conclusion

The contributions of our study are twofold. From the theoretical perspective, this study advances the EPPM with social cues by exploring fear appeal messages in social media health campaigns and investigating the potential effectiveness of social cues on health message acceptance. The findings reveal a significant main effect of threat and three-way interaction among threat, efficacy, and social cues. This research provides a new perspective for health campaigns on social media, which motivates scholars to broaden the field’s understanding of the interactive effects of message content and social cues on social media.

In terms of practical implications, the findings of the current study provide useful suggestions for vaccination promotion campaigns on Chinese social media. Specifically, it suggests that fear appeal messages could be effective in promoting HPV vaccination among Chinese women. However, in order to avoid only using heuristic information processing to assess messages, the side effects of the number of likes should be recognized when conducting fear appeal campaigns on social media. In addition, for vaccination promotion campaigns, the efficacy information should be more specific and audience-centered.

Nevertheless, the study is not without limitations. First, in regard to stimuli, the efficacy message in the experiment is inadequate. The efficacy on the stimulus picture only provided information about vaccination appointments, but lacked specific steps to instruct and guide individuals on how to carry out the HPV vaccination. Future studies might conduct a focus group to gain a deeper understanding of general efficacy perception and to design a message with sufficient efficacy. Second, this study merely focused on the effectiveness of fear-appeal messages. However, message framing and message structure that might also promote HPV vaccinations have never been examined. Future studies should use a different persuasive health message framework to develop vaccination promotion campaigns. Third, the current study only investigated a single type of social cues – likes. However, social cues are not presented separately on social media platforms. The experimental settings of social cues should integrate multiple social cues, such as likes and reposts in future studies. The effects of different social cues on fear appeal messages should be further examined as well. Lastly, the current research measured behavioral intentions for HPV vaccinations. While some scholars have indicated a high correlation between, and transformation from, intentions to behaviors,Citation50 intentions do not indicate HPV vaccination behavior. Future research should focus on actual behavioral outcomes. In total, further investigation is needed to address the above limitations in different contexts and cultures.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (4.1 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1975449.

Additional information

Funding

References

- HPV Information Centre. Human papillomavirus and related diseases report: China. [accessed 2020 Dec 6]. http://www.hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/CHN.pdf

- Hull R, Mbele M, Makhafola T, Hicks C, Wang SM, Reis RM, Mehrotra R, Mkhize Kwitshana Z, Kibiki G, Bates DO, et al. Cervical cancer in low and middle income countries. Oncol Lett. 2020 Sep 1;20(3):2058–74. doi:10.3892/ol.2020.11754.

- Bruni L, Albero G, Serrano B, Mena M, Gómez D, Muñoz J, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. ICO/IARC information centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV information centre).Human papillomavirus and related diseases in China. Summary Report. 2019 June 17 [Accessed 2021 Apr 5]. https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/CHN.pdf?t=1617614054427

- Xiang J, Han L, Fan Y, Feng B, Wu H, Hu C, Qi M, Wang H, Liu Q, Liu Y. Prevalence and genotype distribution of human papillomavirus among attendees at a sexually transmitted diseases clinic in Urban Tianjin, China. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:1983. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S308215.

- National Institutes of Health. Cervical cancer treatment (PDQ®)–Health professional version. [accessed 2020 Dec 6]. https://www.cancer.gov/types/cervical/hp/cervical-treatment-pdq#_284_toc

- Chen L, Song Y, Ruan G, Zhang Q, Lin F, Zhang J, Sun P, An J, Dong B, Sun P. Knowledge and attitudes regarding HPV and vaccination among Chinese women aged 20 to 35 years in Fujian province: a cross-sectional study. Cancer Control. 2018;25:1–9. doi:10.1177/1073274818775356.

- Hu S, Xu X, Zhang Y. A nationwide post-marketing survey of knowledge, attitude and practice toward human papillomavirus vaccine in general population: implications for vaccine roll-out in mainland China. Vaccine. 2021;39:35–44.

- Zhang Y, Wang Y, Liu L, Fan Y, Liu Z, Wang Y, Nie S. Awareness and knowledge about human papillomavirus vaccination and its acceptance in China: a meta-analysis of 58 observational studies. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:216. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2873-8.

- Zhou L, Zhang D, Yang CC, Wang Y. Harnessing social media for health information management. Electron Commer Res Appl. 2018;27:139–51. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2017.12.003.

- Graham AL, Cobb CO, Cobb NK. The internet, social media, and health decision-making. In: Diefenbach MA, Miller-Halegoua S, Bowen DJ, editors. Handbook of health decision science. New York (NJ): Springer; 2016. p.335–55.

- Shi J, Chen L. Social support on Weibo for people living with HIV/AIDS in China: a quantitative content analysis. Chin J Commun. 2014;7:285–98.

- McMullan M. Patients using the Internet to obtain health information: how this affects the patient–health professional relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63:24–28. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2005.10.006.

- Chen L, Yang X. Using EPPM to evaluate the effectiveness of fear appeal messages across different media outlets to increase the intention of breast self-examination among Chinese women. Health Commun. 2019;34:1369–76. doi:10.1080/10410236.2018.1493416.

- Chou WYS, Trivedi N, Peterson E, Gaysynsky A, Krakow M, Vraga E. How do social media users process cancer prevention messages on Facebook? An eye-tracking study. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103:1161–67. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2020.01.013.

- Tong ST, van der Heide B, Langwell L, Walther JB. Too much of a good thing? The relationship between number of friends and interpersonal impressions on Facebook. J Comput-Mediat Commun. 2018;13:531–49. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2008.00409.x.

- Chen L, Tang H, Liao S, Hu Y. e-Health campaigns for promoting influenza vaccination: examining effectiveness of fear appeal messages from different sources. Telemed e-Health. 2020;27:763–70. doi:10.1089/tmj.2020.0263.

- Wang X, Chen L, Shi J, Peng T. What makes cancer information viral on social media? Comput Hum Behav. 2019;93:149–56. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.024.

- Shi J, Poorisat T, Salmon CT. The use of social networking sites (SNSs) in health communication campaigns: review and recommendations. Health Commun. 2018;33:49–56. doi:10.1080/10410236.2016.1242035.

- Witte K. Predicting risk behaviors: development and validation of a diagnostic scale. J Health Commun. 1996;1:317–42. doi:10.1080/108107396127988.

- Maloney EK, Lapinski MK, Witte K. Fear appeals and persuasion: a review and update of the extended parallel process model. Soc Pers Psychol Compa. 2011;5:206–19. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00341.x.

- De Hoog N, Stroebe W, De Wit JB. The impact of vulnerability to and severity of a health risk on processing and acceptance of fear-arousing communications: a meta-analysis. Rev Gen Psychol. 2007;11:258–85. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.11.3.258.

- Witte K, Allen M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(5):591–615. doi:10.1177/109019810002700506.

- Witte K. Fear control and danger control: a test of the extended parallel process model (EPPM). Commun Monogr. 1994;61:113–34. doi:10.1080/03637759409376328.

- Shi J, Smith SW. The effects of fear appeal message repetition on perceived threat, perceived efficacy, and behavioral intention in the extended parallel process model. Health Commun. 2016;31:275–86. doi:10.1080/10410236.2014.948145.

- Smith SW, Rosenman KD, Kotowski MR, Glazer E, McFeters C, Keesecker NM, Law A. Using the EPPM to create and evaluate the effectiveness of brochures to increase the use of hearing protection in farmers and landscape workers. J Appl Commun Res. 2008;36:200–18. doi:10.1080/00909880801922862.

- Sheeran P, Harris PR, Epton T. Does heightening risk appraisals change people’s intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:511. doi:10.1037/a0033065.

- Avery EJ, Park S. HPV vaccination campaign fear visuals: an eye-tracking study exploring effects of visual attention and type on message informative value, recall, and behavioral intentions. Public Relat Rev. 2018;44:321–30. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.02.005.

- Prati G, Pietrantoni L, Zani B. Influenza vaccination: the persuasiveness of messages among people aged 65 years and older. Health Commun. 2012;27:413–20. doi:10.1080/10410236.2011.606523.

- Walther JB. Computer-mediated communication: impersonal, interpersonal, and hyperpersonal interaction. Commun Res. 1996;23:3–43. doi:10.1177/009365096023001001.

- Sundar SS. The MAIN model: a heuristic approach to understanding technology effects on credibility. In: Miriam JM, Andrew JF, editors. Digital media, youth, and credibility. Cambridge (MA): The MIT Press; 2008. p. 73–100.

- Metzger MJ, Flanagin AJ, Medders RB. Social and heuristic approaches to credibility evaluation online. J Commun. 2010;60:413–39. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01488.x.

- Westerman D, Spence PR, van der Heide B. A social network as information: the effect of system generated reports of connectedness on credibility on Twitter. Comput Hum Behav. 2012;28:199–206. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2011.09.001.

- Chen L, Yang X, Fu L, Liu X, Yuan C. Using the extended parallel process model to examine the nature and impact of breast cancer prevention information on mobile-based social media: content analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2019;7:e13987. doi:10.2196/13987.

- Boyd D, Golder S, Lotan G. Tweet, tweet, retweet: conversational aspects of retweeting on twitter. In: 2010 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. USA, Hawaii: IEEE; 2010. p. 1–10.

- Borah P, Xiao X. The importance of ‘Likes’: the interplay of message framing, source, and social endorsement on credibility perceptions of health information on Facebook. J Health Commun. 2018;23:399–411. doi:10.1080/10810730.2018.1455770.

- Winter S, Brückner C, Krämer NC. They came, they liked, they commented: social influence on Facebook news channels. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw. 2015;18:431–36. doi:10.1089/cyber.2015.0005.

- Phua J, Ahn SJ. Explicating the ‘like’on Facebook brand pages: the effect of intensity of Facebook use, number of overall ‘likes,’ and number of friends”likes’ on consumers’ brand outcomes. J Mark Commun. 2016;22:544–59. doi:10.1080/13527266.2014.941000.

- Ma Z, Nan X. Investigating the interplay of self-construal and independent Vs. interdependent self-affirmation. J Health Commun. 2019;24:293–302. doi:10.1080/10810730.2019.1601300.

- Chen M, Chen L. Promoting smoking cessation in China: using an expansion of the EPPM with other-oriented threat. J Health Commun. 2021;26:1–10.

- Napper LE, Harris PR, Klein WM. Combining self-affirmation with the extended parallel process model: the consequences for motivation to eat more fruit and vegetables. Health Commun. 2014;29:610–18. doi:10.1080/10410236.2013.791962.

- Witte K, Meyer G, Martell D. The risk behavior diagnosis scale. Effective health risk messages: a step-by-step guide. Los Angeles (CA): Sage; 2001. p. 67–76.

- Carcioppolo N, Jensen JD, Wilson SR, Collins WB, Carrion M, Linnemeier G. Examining HPV threat-to-efficacy ratios in the extended parallel process model. Health Commun. 2013;28:20–28. doi:10.1080/10410236.2012.719478.

- Chaiken S. Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39:752. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.39.5.752.

- Chaiken S, Liberman A, Eagly AH, Uleman JS, Bargh JA. Heuristic and systematic information processing within and beyond the persuasion context. In: James SU, John AB, editors. Unintended thought. New York (NJ): Gulford Press; 1989. p. 212–52.

- Hong H. An extension of the extended parallel process model (EPPM) in television health news: the influence of health consciousness on individual message processing and acceptance. Health Commun. 2011;26:343–53. doi:10.1080/10410236.2010.551580.

- Goei R, Boyson AR, Lyon-Callo SK, Schott C, Wasilevich E, Cannarile S. An examination of EPPM predictions when threat is perceived externally: an asthma intervention with school workers. Health Commun. 2010;25:333–44. doi:10.1080/10410231003775164.

- Li L, Li J. Factors affecting young Chinese women’s intentions to uptake human papillomavirus vaccination: an extension of the theory of planned behavior model. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16:3123–30. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1779518.

- Oinas-Kukkonen H, Harjumaa M. Persuasive systems design: key issues, process model and system features. In: Michael H, Ishani M, editors. Routledge handbook of policy design. New York (NJ): Routledge; 2018. p. 105–23.

- Trumbo CW. Information processing and risk perception: an adaptation of the heuristic-systematic model. J Commun. 2002;52:367–82. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2002.tb02550.x.

- Peters GJY, Ruiter RA, Kok G. Threatening communication: a critical re-analysis and a revised meta-analytic test of fear appeal theory. Health Psychol Rev. 2013;7(sup1):S8–S31. doi:10.1080/17437199.2012.703527.