ABSTRACT

Parental hesitancy related to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines has increased during the pandemic, and there is a call to action by the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable to improve vaccination rates. While there are evidence-based strategies available to address parental hesitancy, there are few clear guidelines on how to engage parents to build confidence in the HPV vaccine within the clinical settings. The purpose of this investigation is to explore practice protocols, individual provider strategies, and perceived tools needed to address HPV vaccine hesitant parents from the perspective of providers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Fifteen healthcare providers participated in qualitative, semi-structured interviews between May 2021 and March 2022. An inductive, qualitative content analysis approach was used to analyze the data. Five themes were described: 1) Provider experiences engaging with HPV vaccine hesitant parents; 2) Existing protocols in the clinics to address HPV vaccine hesitant parents; 3) Strategies used by providers to address parental HPV vaccine hesitancy; 4) Sample message content used by providers to address parental HPV vaccine concerns; and 5) Perceived strategies and tools needed to address parental vaccine hesitancy. Recommendations to address parental hesitancy include recommending HPV vaccinationat 9 years, using a strong recommendation and continued discussion, applying evidence-based approaches and/or promising strategies, linking parents to credible outside sources, and ongoing follow-up if delayed or declined. These findings can be used by researchers and clinicians to improve strategies and messages to inform the development of a protocol to standardize encounters and communication for patient-parent-provider encounters that can influence parental decision-making around HPV vaccine uptake.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination rates remain suboptimal despite proven safe and efficacious vaccines.Citation1–5 HPV causes the majority of cervical, oropharyngeal, anal, vulvar, vagina, and penile cancers and genital warts.Citation6–8 Ninety percent of HPV-attributable cancers could be prevented through vaccination.Citation6–8 Only 67.1% of U.S. adolescents aged 13–17 years are up-to-date on their HPV vaccines in 2021,Citation9 well below the national goal of 80%. Recent studies further suggest the COVID-19 pandemic impacted HPV vaccination rates. For example, Saxena et al. used historical data in a U.S. claims database and found that HPV vaccination was 24.0% lower in 2020 compared to 2019 among adolescents aged 9–16 years.Citation10 HPV vaccine hesitancy is on the rise with rates estimated as high as 64%.Citation11–14 Vaccine hesitancy is when an individual chooses to delay or refuse the HPV vaccine at the time of the initial recommendation despite vaccine availability.Citation15 Lack of, inconsistent, or low-quality healthcare provider recommendations, the strongest predictor of vaccine uptake,Citation16 have played a major role in undermining parental acceptance.Citation17,Citation18 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends continued engagement with vaccine hesitant parents with ultimate practice dismissal as an option.Citation19 Yet, there are few guidance documents on how to engage parents in building confidence in the HPV vaccine.

Evidence suggests that a presumptive approach,Citation20,Citation21 motivational interviewing,Citation22 and persistenceCitation23,Citation24 are associated with increased likelihood and uptake of the HPV vaccine. However, past studies suggest there are existing barriers that can create difficulty in implementing these methods within a clinic practice. Many studies have found that low HPV vaccine knowledge levels, negative attitudes, and beliefs of providers can decrease or lead to lack of confidence to recommend and discuss the vaccine.Citation25,Citation26 In addition, personal biases, perceived discomfort, and lack of skills can negatively influence provider recommendation practices (e.g., lack of a presumptive approach).Citation25,Citation26 Perceived parental hesitancy has also been found associated with lack of provider self-efficacy, reduced outcome expectations, and concerns over HPV vaccine safety.Citation27 In an earlier study, some providers stated continued discussion and the additional time needed to conduct the persistence approach with vaccine hesitant parents creates an unsatisfactory job environment,Citation28 and reports suggest this is leading to increased family dismissals.Citation29 Sturm et al. further found that pediatricians provided mixed messages and sometimes offered inaccurate information.Citation30 These findings suggest there is a need for standardization of practice to improve HPV vaccination outcomes.

Earlier studies with other health behaviors have shown that clinic protocols can improve standardization and communication,Citation31 and ultimately health outcomes.Citation32 They aid in the management of a clinical situation or process of care that will apply to most patients, and can be tailored to the clinics’ needs.Citation33 They support the adoption of evidence-based strategies into the protocols which can help reduce harm to the patient and promote good will.Citation32 Application of these protocols in clinical encounters can strengthen provider’s recommendation and communication practices and reduce error in message delivery.Citation32 Furthermore, they facilitate the implementation of training for providers to ensure these protocols are implemented accurately.Citation31 Emerging studies, primarily quantitative in nature, explore strategies used at the clinic level which can be used to inform protocols and checklists. EMR-based remindersCitation34 and EMR-linked clinical decision support toolsCitation35 have been found effective in increasing the likelihood of routine recommendations. Fontenot et al.Citation36 found that use of a coordinated team approach increases HPV vaccination rates. Tsui et al.Citation37 explored clinic staff roles in communication and administration of the HPV vaccine. However, little has been reported on the actual protocols used within clinics to address parents who delay or decline the HPV vaccine. The goal of this study was to explore existing practice protocols, individual provider strategies, and tools that providers perceive would help to address HPV vaccine hesitant parents from the perspective of pediatric, adolescent medicine, and family providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is anticipated that these findings might be used to inform the development of a protocol for providers that would assist in their ability to address parental HPV vaccine hesitancy.

Materials and methods

Study design

We conducted semi-structured interviews using a qualitative, phenomenologicalCitation38,Citation39 study design to: 1) gain a deeper understanding of practice protocols and provider strategies to address parental HPV vaccine hesitancy; and 2) perceived tools need to improve parental hesitancy. Adapted from Vaccination Confidence Scale,Citation40 we used a brief 10-item survey prior to the interview to identify common barriers to HPV vaccination for vaccine hesitant parents. Data collection occurred from May 2021 to March 2022. This study was approved by Meharry Medical College Institutional Review Board (Protocol Number: 18-12-890).

Sample and recruitment

We recruited a purposeful, criterion sample of U.S. providers who routinely see adolescents and engage with HPV vaccine hesitant parents. A purposeful, criterion sample is a selection of individuals that are especially knowledgeable about or experienced with a phenomenon of interest.Citation41,Citation42 Studies have found that 6 to 12 interviews are a necessary number of participants to reach saturation.Citation43–45 For example, Creswell recommends up to 10 long interviews to reach saturation in a qualitative, phenomenological study.Citation39 Ongoing data analyses allowed us to determine when saturation (i.e., no new emerging themes) was met.Citation46

Providers were identified using a purposeful, snowball sampling method, enlisting providers throughout the U.S. who met eligibility criteria.Citation41,Citation42 Specifically participants were asked to nominate other providers to participate in the interview. This method was chosen to help increase participation since: 1) many providers were “hard-to-reach during early COVID-19 pandemic due to shifted priorities and high demands,Citation47 and 2) the physicians-recruiting-physicians method has been found successful.Citation48 Recruitment methods were mail, e-mail (personal and list-servs), or word-of-mouth. Providers were eligible if they were physicians (i.e., pediatric, adolescent medicine, or family medicine), physician assistants, or nurse practitioners who deliver primary care to adolescent patients aged 11–18 years.

Data collection

Participants were sent a survey screener by e-mail. If they met the eligibility criteria, they were sent an informed consent document followed by a brief survey. These data were collected via REDCap, a secure web-based data collection application.Citation49 After the surveys were collected, 30–45 minute interviews were conducted by a PhD level researcher and Master’s level program manager who are trained in qualitative research methodology and knowledgeable on parental HPV vaccine hesitancy based on current and past research projects. The interview protocol was based on the literature and had five primary questions with associated probes:

Please describe your experience in engaging with parents who were hesitant about receiving the HPV vaccine.

In your experience, what are reasons parents decide not to get their child vaccinated for HPV?

What is the protocol of your practice once a parent delays and/or refuses the HPV vaccine?

What strategies have you and/or your staff used to address parents who are hesitant about getting the HPV vaccine for their children? Were they successful or not successful?

What tools or information do you need in order to engage vaccine hesitant parents?

In addition, the interview protocol included questions asking the providers to give feedback on a draft intervention under development by the team, which were not included in the current analysis. Interviews were recorded via Zoom, transcribed verbatim, and de-identified for data analysis.

Analytic plan

SPSS version 28 was used to analyze survey data. Descriptive analysis (e.g., means, frequencies) were used to describe patterns in the data. Qualitative data coding and analysis were conducted following Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) guidelines.Citation50 Microsoft Excel version 2016 was used to manage quotations and codes. A PhD level researcher and a 2nd year graduate student, both trained in qualitative research methodology, conducted the analysis using an inductive-deductive qualitative approach. Each coder performed an open coding technique among five transcripts to establish reliability in the coding system. Meetings occurred at four time points to discuss subsequent coding. As new meanings emerged, codes were added or modified accordingly. Inconsistencies in coding were checked and rechecked until a coding consensus was reached. Codes were placed into categories using axial coding. Inductively, a constant comparison method was used to compare the codes and develop higher-order themes. Based on analysis, saturation was met at participant 11; however, we collected data until participant 15. Strategies to ensure rigor included investigator triangulation, thick, rich descriptions, and peer debriefing.Citation51

Results

Socio-demographics

Nineteen providers were screened, of which four did not respond to complete the interview. Majority of the 15 providers interviewed were White (66.7%), female (73.3%), pediatricians (88.6%), and practiced in an urban area (66.7%). The mean of years practicing was 14.3 with year of residency training completion ranging from 1982 to 2021. The providers varied in their areas of residence in the U.S., with 8 from the South, five from the Northeast, one in the West, and one in the Midwest. See for summary of providers’ socio-demographics.

Table 1. Provider characteristics, n = 15.

Semi-structured interviews

Theme 1: Provider experiences engaging with HPV vaccine hesitant parents

Most providers stated parents were more hesitant about the HPV and influenza vaccines in a clinical encounter compared to other vaccines. The “spillover” of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy into childhood immunizations such as HPV was also stated. Specifically, the lack of understanding of the testing and approval process for COVID-19 vaccines were identified to increase hesitancy. One provider stated, “doctors don’t start with a clean slate due to garbage on the internet.” Parents of male, transgender/gay, or younger adolescents were perceived to delay or refuse the HPV vaccine at higher rates compared to other adolescent immunizations according to a few providers. One provider perceived HPV vaccine hesitancy was higher and vaccine uptake lower when mothers took the child for the clinic visit.

In clinical encounters, many providers perceived hesitant parents had many questions but often did not want to engage in discussion. A provider further described how parents classified vaccines as essential (i.e., preventing a deadly disease), mandatory for school, or non-essential (i.e., not an immediate threat), in which the vaccine was often viewed as non-essential. Almost half of the providers discussed how adolescents and teens occasionally played a role in parental decision-making. Specific examples were: 1) if the younger adolescent was unsure or did not want to get the vaccine, then the parent would delay or refuse the vaccine; or 2) an older adolescent wanted to get the vaccine and convinced their undecided or hesitant parent to allow them to get the vaccine. However, providers stated that sometimes a parent would use statements like “well, don’t look at me if something happens” to try to deter their child from getting the vaccine, or just say “after 18 years you can make your own decisions.” Last, a provider stated many other providers in the clinic were uncomfortable discussing the HPV vaccine after a parent delayed or refused the vaccine, which negatively impacted the clinics’ progress in vaccine uptake.

Theme 2: Existing protocols in the clinics to address HPV vaccine hesitant parents

All providers were required to monitor HPV vaccination rates and document encounters with parents and their adolescents during clinic visits. One provider highlighted it was hard to document these visits as there was no code in the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) to document HPV vaccine refusals. Only one provider stated their clinic had an official protocol to use motivational interviewing to address HPV vaccine hesitant parents. The pediatrician stated,

We’re all trained. I work at a hospital in a two-physician practice for an advanced nursing practice which involves three sites, two school-based clinics and one outpatient hospital site. We are all trained in motivational interviewing, and we all are on board with including it in every option that we give to our patients.

Most providers stated their clinics had a standard practice to strongly recommend the vaccine. This included announcing all three vaccines (meningococcal, HPV, and Tdap vaccines) while “sandwiching” HPV vaccination in the middle. One provider stated a trained medical assistant recommended the vaccine, documented parental concerns, and relayed those concerns to the provider to address during the clinic visit. If parents delayed or refused, almost all providers queried their concerns and provided written materials or webpages to review post-visit (CDC and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia). They also provided reminders at follow-up visits. A few clinics used a team-based approach (i.e., “clinic staff from the front to the back of the office”) to recommend and discuss the vaccine, or the use of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles and in-service to provide education to clinic staff to address parental concerns. In addition, a few clinics were recommending the HPV vaccine starting at 9 years of age. One physician provider stated,

“We have been initiating at 9 years for a long time. Majority of patients get two vaccines. A fair number of parents do not want to start a nine and more receptive at 11 or 12 years. However, there is less resistance once initiating other shots. I would say one-half get vaccinated at age 9, and 14, 15, and 16 year olds say they want it and they convince the parents at these older ages.”

For providers working at a teaching hospital or a resident-run clinic, they trained residents to provide a strong recommendation, have evidence on vaccine safety and effectiveness, and offer different strategies (e.g., motivational interviewing) to address vaccine hesitancy. One provider mentioned the resident-run clinic developed a script for providers to give a strong recommendation and HPV information, highlight vaccine safety and effectiveness, and state the importance of vaccinating now. One provider stated the clinic provides parents with HPV vaccine information sheets (VIS) in the waiting room and then have a brief discussion during the clinic encounter. Many providers indicated these varying practices within clinics can further fuel HPV parental hesitancy.

Theme 3: Strategies used by providers to address parental HPV vaccine hesitancy

Strategies used by providers were clinical level strategies and/or provider dependent. At every visit, almost all providers identified and tailored discussion to parents’ concerns. A few began recommending vaccines at 9 years of age and others used motivational interviewing to discuss concerns regardless of clinic practices. The purpose of early recommendation was to: 1) reduce the number of vaccine types needed at ages 11 to 12 years (e.g., HPV vaccine given between ages 9 and 10 years and Tdap and Meningoccocal vaccines given between ages 11 and 13 years; 2) discuss the HPV vaccine over time; and 3) alleviate the concern of adding this vaccine during puberty when both parents and children are “overwhelmed” and can be “less stigmatizing.” After a parent declined or delayed the vaccine, almost all providers provided written information and continued to recommend the HPV vaccine. This was done until a parent(s) agreed to get the child the vaccine or stated they no longer wanted to discuss the vaccine. “Constantly bringing up the vaccine after each refusal at each visit allows the parent to think about the benefits of getting the vaccine, see others who have gotten it, and become more comfortable with the idea of giving it to their child,” one provider stated.

A few providers used parent-centered approaches via partnering with parents to teach young adolescents and teens autonomy in health decision-making, or to encourage them to communicate about sex with children. The purpose was to ensure the medical teams’ recommendations were in line with parental values and recommendations. One provider encouraged a parent to talk with other parents to hear their experiences, and another did pre-visit outreach via families completing a survey to identify parental concerns and prepare for the clinic visit. Last, a provider found it important to evaluate provider-parent-patient encounters via a post-survey to ensure parents were still satisfied despite the discussion. Other strategies included use of bulletin boards in clinic to demonstrate progress on HPV vaccine uptake and compliance, along with articles in newspapers and workshops in the community for education purposes.

Two providers also discussed the importance of being trustworthy for parents to believe in the recommendations and to dialogue about the vaccine. Another provider further discussed the importance of transparency and honesty about HPV and the vaccine to build trust. One provider stated,

I try to understand their reasoning and not be judgmental. I assess what they know and don’t know. I have various strategies of persuasion and education depending on their reasoning for hesitancy. The common denominator for all strategies is to provide education depending on where they are. The level of knowledge about the disease and the vaccine and the underlying medical condition of the adolescent patient will dictate my approach.

Three providers identified use of signage in waiting rooms and clinic rooms, too many messages from different sources, discussion of sexual practices, and education for parents who “have already done their homework” as unsuccessful. Examples of perceived unacceptable messaging for a couple of providers were telling parents they are responsible for the decision makes them feel as if they are giving permission to have sex or cancer prevention. Another provider stated the discussion around cancer prevention did not work for many hesitant parents, especially if the child was younger and cancer was not on their “radar.”

While she asked the parent to have an “open-mind,” one provider did not engage with a parent once he or she declined the vaccine for the child. The rationale was the provider perceived these parents have done their research and does not want to “push them away.” Furthermore, the provider wanted parents to be happy with their decision.

Theme 4: Sample message content used by providers to address parental HPV vaccine concerns

When providers were asked of the strategies used to address parental HPV vaccine hesitancy, a few offered examples of message content. A brief summary of the message content used by providers to build confidence in the HPV vaccine is described below.

General hesitancy

To initiate the conversation, one provider asks “Did you get your child the HPV vaccine at another location or are you aware of it?” To ease comfort of parents, some providers state their child received the HPV vaccine, “why” they received it, and the process he/she went through to make the decision. A few told parents there is a lot of misinformation and suggested reputable websites (e.g., CHOP and CDC). One provider reminded parents they make decisions every day for their child(ren) and this is a positive one they can make if they are ready.

Too new

Most providers state the date of FDA approval or number of years the vaccine has been approved. Another provider discussed the number of vaccines given since approval.

Perceived low risk of HPV

A few providers validated parent’s perception of adolescent being at low risk. They further provided the caveat of the child possibly getting HPV from someone, which could lead to cancer or the child could cause cancer in others. They further emphasized “we want to treat each other like family and keep each other safe for the greater good of the people.” Another provider commonly told parents of younger adolescents “This is not about preventing them from a STD at age 11.”

Need for vaccine

To increase parental perceived need of the child getting the HPV vaccine, many providers defined HPV and its etiology and link with cancer. They also state it is the only vaccine and most successful prevention tool against HPV-related cancers and genital warts. A small number of providers highlighted the number of pre-cancer and cancers prevented post-vaccination. The provision of evidence-based guidelines of why adolescents and teens are vaccinated and stating this is an investment in the child’s future was thought to increase parental perceived need. Another statement used is “you do not know when someone could be exposed.” To reduce stigma of HPV being a “females disease,” one provider emphasized everyone can receive the vaccine now and it prevents cancer in both men and women.

Safety

Some providers announce the vaccine is safe, and then discuss vaccine safety issues. Examples include explaining the vaccine purpose and how it works and providing safety evidence and how it compares to other cancer prevention drugs. They also list adverse events and explain how they are monitored by the CDC to ensure children are safe. A few providers discuss the number of trials, the amount of safety data, and explanation of trial results. It was deemed important to explain the side effect profile of the HPV vaccine and how it is comparable to other vaccines. Last, to address the concern of a child dying from receipt of the vaccine, a provider states there is no evidence to suggest HPV vaccines can lead to death and/or other major health concerns.

Permission to have sex

Many providers stated studies demonstrate HPV vaccine receipt is not associated with increased sexual activity. Another statement was, “You give hep b vaccine [vaccine to prevent against sexually transmitted disease that can cause cancer] for your child(ren) and it is very effective most of the time.” One provider even addresses sex in the context of dating, stating they raised the child and have done a good job. The parent is encouraged to trust the child and to support wanting to receive the HPV vaccine.

Too young

Most providers discussed with the adolescent and parent that hepatitis B vaccine was given at birth to protect against liver cancer. Providers also stated, “Your child gets two shots compared to three if given before 15 years of age.” Furthermore, some explained the immune system responds differently at 15 years; hence, the need for 3 doses instead of two. Another message used by a provider was, “We want to make sure the vaccine is in their system well before exposed to HPV so that they have maximum protection. It is never a bad time but there’s no time like the present.” These messages were primarily for parents with younger adolescents.

Effectiveness

Providers stated, “This vaccine is effective in preventing cancer and HPV, the virus that causes cancer.” They further emphasized HPV causes several cancers. Statistics related to HPV cancer incidence, morbidity, and deaths post-HPV vaccination were also provided by two providers. Last, a provider ended this message with positives statements like “It is pretty cool to have a vaccine that prevents cancer.”

Religion

One provider told parents he shared their goals for the adolescent to be healthy now and in the future along with wanting to work with the parent to help in decision-making for the child such as HPV-related cancers.

Theme 5: Perceived strategies and tools needed to address parental vaccine hesitancy

Twelve providers perceived new strategies and tools were needed to address parental HPV vaccine hesitancy. Based on their experiences, 13 providers made suggestions to address perceived parental HPV vaccine hesitancy using multi-level strategies.

Policy and clinic level strategies

The recommended policy level changes by some providers included recommending the vaccine at nine years and mandating the vaccine. Clinic level changes include establishing a protocol for providers on how to address parental HPV vaccine hesitancy, along with dedicated time to have “fruitful conversations and not rushing.” Other recommendation included consistent messaging from the front desk to the provider, posting QR codes in clinic to link parents to credible information, and use of dot phrases in the EMR to document reasons for hesitancy and instructions to parent post-clinic visit for reference in future visits. In addition, a strong recommendation and information pre-visit via phone or text or in waiting room during the visit was highly favored. One provider stated parents should be given the opportunity to think about the recommendation and do their own research if they delay or refuse the HPV vaccine.

Community and interpersonal level strategies

Many providers perceived it was important to teach adolescents and teens autonomy in decision-making. One provider further suggested encouraging family discussion and research on the HPV vaccine pre- or post-clinic visit with guidance from providers on reputable resources. This could help adolescents and teens convince parents to get the vaccine or they would be ready to get the vaccine as soon as they turned 18 years of age. A handful of providers suggested community members including parents and patients should serve as peer educators or vaccine champions. They are trusted due to their experience or advocacy for vaccines. Furthermore, it was suggested that parents and their teens should be empowered to have conversations with their doctor about the HPV vaccine. Last, one provider stated all clinics should stock the vaccine to facilitate easy access.

Educational strategies

Almost all providers needed more educational tools. These tools could be a one-to-two minute video for parents to view in waiting room, a brief handout for clinic visits, or an electronic-based intervention(s) that could be sent through the clinics’ encrypted Wi-Fi pre- and post-visit. Content should be gender neutral and multilingual. Materials should not be “heavy” in content, statistics, and images. Example content included etiology of HPV-cancers and rates by sex, vaccine efficacy (e.g., number of cancers prevented among men and women with the vaccine), number of doses given to date, adverse side effects, and date of approval.

Discussion

The recent decline in HPV vaccination rates during the COVID-19 pandemic has created a public health call to action to get vaccination back on track.Citation52 Gilkey et al. highlighted a 70% or greater decline in billing for HPV vaccines in March 2020,Citation52 and studies suggest there is convergence in hesitancy between COVID-19 and HPV vaccines.Citation53 Providers play a critical role in recommending and addressing parental concerns on HPV vaccination.Citation54 This is one of the first studies to explore existing clinic protocols used to address HPV vaccine hesitant parents according to pediatric, family, and adolescent providers. In our study, only one provider stated his clinic had a protocol to use motivational interviewing, a strategy found effective in addressing HPV vaccine parents.Citation22 As recommended by Brewer et al.Citation21 a few did announce the vaccines that were due and engaged in dialogue to address parental concerns, if necessary. Primary health care providers are now being encouraged to recommend the vaccine as early as 9 years of age to increase likelihood of “on time” vaccination.Citation55 Similar to our findings, Kong et al.Citation56 found that over two-thirds of the providers in a national sample were willing to or recommended the vaccine at ages nine and ten years. Lack of clear clinic protocols to address HPV parental vaccine hesitancy has been found to influence provider advocacy for the vaccine,Citation57 and could reflect the varying strategies applied by providers in our study.

Our study also asked providers their perceived needs to address HPV vaccine hesitant parents based on their experiences. Most providers recommended HPV vaccine administration at age of 9 years, supporting current findings of the positive impact of early recommendations in improving on-time vaccine initiation and completion.Citation58 Provider consideration of an early recommendation is potentially advantageous having a longer decisional timeframe could increase parental likelihood of HPV vaccine uptake.Citation59 Other recommendations were the development of a protocol to address HPV vaccine hesitant parents and the need to allot time for providers to counsel parents during clinic visits. This has been identified by prior studies,Citation59 and collectively these findings support a review of current clinic protocols to create a universal protocol to recommend HPV vaccines and engage hesitant parents, but one that could be adapted per needs of the clinic. Providers also perceived there was a need to address parents outside of the clinic visit, including use of parent champions and patient advocates, which are supported by the National HPV Vaccination RoundtableCitation60 and parent advocacy groups.Citation61 Other strategies with potential impact include empowering families to support adolescent autonomy in health decision-making especially among older adolescents,Citation62 discussions on sex and the vaccine,Citation63 and improvement in patient-parent-provider communications.Citation64

Messaging from providers is equally important to the strategies used to engage HPV vaccine parents. An emerging finding in our study was the discussion of different messages providers used to address different concerns on the HPV vaccine. Similar to Tsui,Citation37 personal experience and scientific data were used to address parental HPV vaccine hesitancy. We further found that message content varied by age of the patient, includes analogies, and relates to altruism and/or protection of child’s health. Further research is needed to explore messaging to further inform adolescent-parent-provider communication.

To inform protocol development, it is important to understand the context of engaging HPV vaccine hesitant parents along with their concerns. When describing experiences engaging HPV vaccine hesitant parents, they varied with almost a third perceiving HPV vaccination communication was normalized. This finding supports the need for effective patient-provider communication. Similar to past studies,Citation63,Citation65 adolescents played a role in the decision of parents to get the HPV vaccine, supporting the need to identify strategies for clinic protocol that supports parent-provider-adolescent communication in the decision-making process. This is particularly important if adolescents have a desire to be involved in decision-makingCitation66 and need to prepare to make health decisions in the future. While uncommonly mentioned, a few providers described increased hesitancy among parents of younger, gay/transgender, and male adolescents. Further exploration is needed among parents with adolescents’ representative of these groups.

Lessons learned and next steps

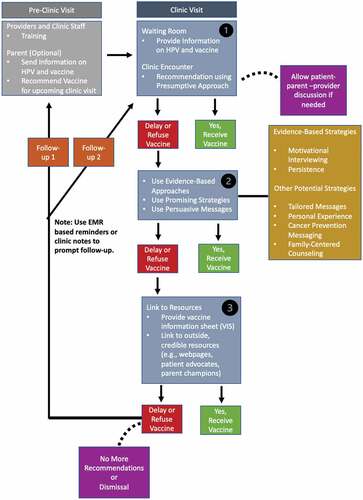

Based on past and current findings, we recommend components for a protocol to standardize clinical encounters when engaging with HPV vaccine hesitant parents in . An example protocol that can happen during one or more clinical visits is available in . The barriers and inconsistencies in engagement indicate ongoing research is needed to improve patient-parent-provider encounters. Next steps for research include determining if targeted strategies and messaging differ by local context and subgroups within the adolescent populations including sex (female compared to males), age (older versus younger), and sexual practices. The use of patient advocates and parent champions should be further explored. There is a need to further explore impactful health education materials that can be disseminated in a vaccine information sheet (VIS) or electronic resource across encrypted Wi-Fi to engage with HPV vaccine hesitant parents pre-, during, and post-visit if necessary. Future research should also examine the relationship between clinic protocol and/or strategy(s) application to address HPV vaccine hesitant parents and actual uptake of the vaccine. Last, there is a need to further explore views and use of protocol and guideline use among providers at a national level and engage other stakeholders (i.e., adolescents, parents, nurses, clinic staff) to inform clinic needs to enhance patient-parent-provider encounters.

Figure 1. Example protocol to engage HPV vaccine hesitant parents in a clinical encounter(s).

Table 2. Recommendations for HealthCare providers to engage HPV vaccine hesitant parents.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength is this study uses semi-structured interviews to obtain rich data on provider protocols, strategies and messages, and necessary tools to address parental HPV vaccine hesitancy. Another strength is perspectives were from providers in states with varying rates for adolescents’ initiation and completion rates. This study has several limitations. The sample is convenient, relatively small, with varying representation across provider types, limiting generalizability of this study’s findings. There was limited representation of family medicine providers. Furthermore, these findings only represent the provider perspective, not other staff (e.g., nurses), or the parents or adolescents. All views related to engaging parents during patient encounters may not be accounted for due to self-selection bias (i.e., providers volunteering for participation), and the likelihood of participants being anonymous is decreased. Current practices and needs may also be influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, which warrants further study. Data collection, analysis, and interpretation could be influenced by researcher biases. However, establishment of researcher biases, investigator triangulation, and thick rich descriptions were used as checkpoints. Last, we did know the vaccination rate for each provider, which could have allowed us to associate their different strategies with higher or lower vaccination rates.

Conclusion

Insights from this study suggest the need for a comprehensive protocol for providers to address hesitant parents to improve HPV vaccine uptake. Researchers and clinicians can use these insights to better understand targeted strategies and messages for patient-parent-provider encounters. Furthermore, policy makers and organizations have an opportunity to support providers in their efforts by developing a standard protocol with associated guidelines to address HPV vaccine hesitant parents that could be tailored to meet the needs of the individual practice.

Consent to participate

Informed Consent was obtained from all study participants.

Data availability

Due to the confidentiality agreements, supporting data cannot be made openly available.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the healthcare providers for their valuable insights on their lived experiences in addressing HPV vaccine hesitant parents.

Disclosure statement

Kathryn Edwards is a consultant to Bionet and IBM: Member Data Safety and Monitoring Board for Sanofi, X-4 Pharma, Seqirus, Moderna, Pfizer, Merck, and Roche.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, Goldstone S, Moreira ED, Aranda C, Jessen H, Hillman R, Ferris D, Coutlee F, Stoler MH, et al. HPV vaccine against anal HPV infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. Oct 27 2011;365(17):1–11. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1010971.

- Giuliano AR, Palefsky JM, Goldstone S, Moreira ED, Penny ME, Aranda C, Vardas E, Moi H, Jessen H, Hillman R, et al. Efficacy of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV Infection and disease in males. N Engl J Med. Feb 3 2011;364(5):401–11. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0909537.

- Kreimer AR, González P, Katki HA, Porras C, Schiffman M, Rodriguez AC, Solomon D, Jiménez S, Schiller JT, Lowy DR, et al. Efficacy of a bivalent HPV 16/18 vaccine against anal HPV 16/18 infection among young women: a nested analysis within the Costa Rica vaccine trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011 Sep;12(9):862–70. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70213-3.

- Herrero R, Quint W, Hildesheim A, Gonzalez, P, Struijk, L, Katki, HA, Porras, C, Schiffman, M, Rodriguez, AC, Solomon, D, et al. Reduced prevalence of oral human papillomavirus (HPV) 4 years after bivalent HPV vaccination in a randomized clinical trial in Costa Rica. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68329. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068329.

- FUTUREI/IIStudyGroup,Dillner J, Kjaer SK, Wheeler, CM, Sigurdsson, K, Iverson, OE, Hernandez-Avila, M, Perez, G, Brown, DR, Koutsky, LA, et al. Four year efficacy of prophylactic human papillomavirus quadrivalent vaccine against low grade cervical, vulvar, and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia and anogenital warts: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. Jul 20 2010;341:c3493. doi:10.1136/bmj.c3493.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV cancers are preventable. DHHS. Accessed September 22, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/protecting-patients.html

- Saraiya M, Unger ER, Thompson TD, Lynch CF, Hernandez BY, Lyu CW, Steinau M, Watson M, Wilkinson EJ, Hopenhayn C, et al. US assessment of HPV types in cancers: implications for current and 9-valent HPV vaccines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015 Jun;107(6):djv086. doi:10.1093/jnci/djv086.

- Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, Markowitz LE, Thomas CC, Thompson TD, Razzaghi H, Saraiya M. Human Papillomavirus–associated cancers — United States, 2008–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jul 8 2016;65(26):661–66. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6526a1.

- Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, Markowitz LE, Valier MR, Fredua B, Crowe SJ, Stokley S, Singleton JA. National vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years — national immunization survey-teen, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Sep 2 2022;71(35):1101–08. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7135a1.

- Saxena K, Marden JR, Carias C, Bhatti, A, Patterson-Lomba, O, Gomez-Lievano, A, Yao, L, Chen, YT. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent vaccinations: projected time to reverse deficits in routine adolescent vaccination in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(12):2077–87. [Accessed 2021 Dec 02]. doi:10.1080/03007995.2021.1981842.

- Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, Markowitz LE, Williams CL, Fredua B, McNamara LA, Stokley S, Singleton JA. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Sep 3 2021;70(35):1183–90. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7035a1.

- Rositch AF, Liu T, Chao C, Moran M, Beavis AL. Levels of parental human papillomavirus vaccine hesitancy and their reasons for not intending to vaccinate: insights from the 2019 National Immunization Survey-Teen. J Adolesc Health. 2022 Jul;71(1):39–46. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.01.223.

- Szilagyi PG, Albertin CS, Gurfinkel D, Saville AW, Vangala S, Rice JD, Helmkamp L, Zimet GD, Valderrama R, Breck A, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of HPV vaccine hesitancy among parents of adolescents across the US. Vaccine. Aug 27 2020;38(38):6027–37. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.06.074.

- Tsui J, Martinez B, Shin MB, Allee-Munoz A, Rodriguez I, Navarro J, Thomas-Barrios KR, Kast WM, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Understanding medical mistrust and HPV vaccine hesitancy among multiethnic parents in Los Angeles. J Behav Med. Feb 2 2022;1–16. doi:10.1007/s10865-022-00283-9.

- MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. Aug 14 2015;33(34):4161–64. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- McRee AL, Gilkey MB, Dempsey AF. HPV vaccine hesitancy: findings from a statewide survey of health care providers. J Pediatr Health Care. 2014 Nov-Dec;28(6):541–49. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2014.05.003.

- Vadaparampil ST, Malo TL, Sutton SK, Ali KN, Kahn JA, Casler A, Salmon D, Walkosz B, Roetzheim RG, Zimet GD, et al. Missing the target for routine human papillomavirus vaccination: consistent and strong physician recommendations are lacking for 11- to 12-year-old males. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016 Oct;25(10):1435–46. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-15-1294.

- Hopfer S, Wright ME, Pellman H, Wasserman R, Fiks AG. HPV vaccine recommendation profiles among a national network of pediatric practitioners: understanding contributors to parental vaccine hesitancy and acceptance. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1776–83. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1560771.

- Edwards KM, Hackell JM. Countering vaccine hesitancy. Pediatrics. 2016 Sep;138(3). doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2146

- Opel DJ, Zhou C, Robinson JD, Henrikson N, Lepere K, Mangione-Smith R, Taylor JA. Impact of childhood vaccine discussion format over time on immunization status. Acad Pediatr. 2018 May-Jun;18(4):430–36. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2017.12.009.

- Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, Gilkey MB, Quinn B, Lathren C. Announcements versus conversations to improve HPV vaccination coverage: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2017 Jan;139(1). doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1764

- Reno JE, O’Leary S, Garrett K, Pyrzanowski J, Lockhart S, Campagna E, Barnard J, Dempsey AF. Improving provider communication about HPV vaccines for vaccine-hesitant parents through the use of motivational interviewing. J Health Commun. 2018;23(4):313–20. doi:10.1080/10810730.2018.1442530.

- Kornides ML, McRee AL, Gilkey MB. Parents who decline HPV vaccination: who later accepts and why? Acad Pediatr. 2018 Mar;18(2s):S37–s43. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2017.06.008.

- Margolis MA, Brewer NT, Boynton MH, Lafata JE, Southwell BG, Gilkey MB. Provider response and follow-up to parental declination of HPV vaccination. Vaccine. Jan 21 2022;40(2):344–50. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.055.

- Gilkey MB, Malo TL, Shah PD, Hall ME, Brewer NT. Quality of physician communication about human papillomavirus vaccine: findings from a national survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015 Nov;24(11):1673–79. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-15-0326.

- Ellingson MK, Bednarczyk RA, O’Leary ST, Schwartz JL, Shapiro ED, Niccolai LM. Understanding the factors influencing health care provider recommendations about adolescent vaccines: a proposed framework. J Behav Med. 2022 [Accessed 2022 Feb 22]. doi:10.1007/s10865-022-00296-4.

- Cunningham-Erves J, Koyama T, Huang Y, Jones J, Wilkins CH, Harnack L, McAfee C, Hull PC. Providers’ perceptions of parental human papillomavirus vaccine hesitancy: cross-sectional study. JMIR Cancer. Jul 2 2019;5(2):e13832. doi:10.2196/13832.

- Kempe A, Daley MF, McCauley MM, Crane LA, Suh CA, Kennedy AM, Basket MM, Stokley SK, Dong F, Babbel CI, et al. Prevalence of parental concerns about childhood vaccines: the experience of primary care physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2011 May;40(5):548–55. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.025.

- Williams JTB, O’Leary ST, Nussbaum AM. Caring for the vaccine-hesitant family: evidence-based alternatives to dismissal. J Pediatr. 2020 Sep;224:137–40. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.029.

- Sturm L, Donahue K, Kasting M, Kulkarni A, Brewer NT, Zimet GD. Pediatrician-parent conversations about human papillomavirus vaccination: an analysis of audio recordings. J Adolesc Health. 2017 Aug;61(2):246–51. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.02.006.

- Kirkpatrick DH, Burkman RT. Does standardization of care through clinical guidelines improve outcomes and reduce medical liability? Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Nov;116(5):1022–26. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f97c62.

- Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. Feb 20 1999;318(7182):527–30. doi:10.1136/bmj.318.7182.527.

- Heymann T. Clinical protocols are key to quality health care delivery. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 1994;7(7):14–17. doi:10.1108/09526869410074702.

- Bundy DG, Persing NM, Solomon BS, King TM, Murakami PN, Thompson RE, Engineer LD, Lehmann CU, Miller MR. Improving immunization delivery using an electronic health record: the ImmProve project. Acad Pediatr. 2013 Sep-Oct;13(5):458–65. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2013.03.004.

- Mayne SL, du Rivage NE, Feemster KA, Localio AR, Grundmeier RW, Fiks AG, duRivage NE. Effect of decision support on missed opportunities for human papillomavirus vaccination. Am J Prev Med. 2014 Dec;47(6):734–44. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.010.

- Fontenot HB, Kornides ML, McRee AL, Gilkey MB. Importance of a team approach to recommending the human papillomavirus vaccination. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2018 Jul;30(7):368–72. doi:10.1097/jxx.0000000000000064.

- Tsui J, Vincent A, Anuforo B, Btoush R, Crabtree BF. Understanding primary care physician perspectives on recommending HPV vaccination and addressing vaccine hesitancy. Hum Vaccin Immunother. Jul 3 2021;17(7):1961–67. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1854603

- DeJonckheere M, Vaughn LM. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour. Fam Med Community Health. 2019;7(2):e000057. doi:10.1136/fmch-2018-000057.

- Creswell J. Qualitative inquiry and research design: chooosing among five traditions. Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications; 1998.

- Gilkey MB, Magnus BE, Reiter PL, McRee AL, Dempsey AF, Brewer NT. The vaccination confidence scale: a brief measure of parents’ vaccination beliefs. Vaccine. Oct 29 2014;32(47):6259–65. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.007

- Creswell JW, Plano-Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed method research, 3rd ed. Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications; 2011.

- Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015 Sep;42(5):533–44. doi:10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y.

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough?: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. [Accessed 2006 Feb 01]. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903.

- Hagaman AK, Wutich A. How many interviews are enough to identify metathemes in multisited and cross-cultural research? Another perspective on guest, Bunce, and Johnson’s (2006) landmark study. Field Methods. 2016;29(1):23–41. [Accessed 2017 Feb 01]. doi:10.1177/1525822X16640447.

- Morse JM Designing funded qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, and Lincoln YS, Handbook of qualitative research. Newbury Park, California: Newbury Park; 1994. pp. 230–35.

- Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews are enough? Qual Health Res. 2017 Mar;27(4):591–608. doi:10.1177/1049732316665344.

- Goddard AF, Patel M. The changing face of medical professionalism and the impact of COVID-19. Lancet. Mar 13 2021;397(10278):950–52. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00436-0

- Borgiel AE, Dunn EV, Lamont CT, MACDONALD PJ, EVENSEN MK, BASS MJ, SPASOFF RA, WILLIAMS J. Recruiting family physicians as participants in research. Fam Pract. 1989 Sep;6(3):168–72. doi:10.1093/fampra/6.3.168.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019 Jul;95:103208. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Morse JM. Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2015 Sep;25(9):1212–22. doi:10.1177/1049732315588501.

- Gilkey MB, Bednarczyk RA, Gerend MA, Kornides ML, Perkins RB, Saslow D, Sienko J, Zimet GD, Brewer NT. Getting human papillomavirus vaccination back on track: protecting our national investment in human papillomavirus vaccination in the COVID-19 era. J Adolesc Health. 2020 Nov;67(5):633–34. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.013.

- Olagoke AA, Carnahan LR, Olagoke O, Molina Y. Shared determinants for human papillomavirus and COVID-19 vaccination intention: an opportunity for resource consolidation. Am J Health Promot. 2022 Mar;36(3):506–09. doi:10.1177/08901171211053933.

- Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: the impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine. Feb 24 2016;34(9):1187–92. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.023.

- O’Leary S, Nyquist A. Why AAP recommends initiating HPV vaccination as early as age 9. Accessed July 16, 2022. https://www.aappublications.org/news/2019/10/04/hpv100419.

- Kong WY, Huang Q, Thompson P, Grabert BK, Brewer NT, Gilkey MB. Recommending human papillomavirus vaccination at age 9: a national survey of primary care professionals. Acad Pediatr. 2022 May-Jun;22(4):573–80. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2022.01.008.

- Lin C, Mullen J, Smith D, Kotarba M, Kaplan SJ, Tu P. Healthcare providers’ vaccine perceptions, hesitancy, and recommendation to patients: a systematic review. Vaccines (Basel). Jul 1 2021;9(7). doi:10.3390/vaccines9070713.

- Biancarelli DL, Drainoni ML, Perkins RB. Provider experience recommending hpv vaccination before age 11 years. J Pediatr. 2020 Feb;217:92–97. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.10.025.

- Gilkey MB, McRee AL. Provider communication about HPV vaccination: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. Jun 2 2016;12(6):1454–68. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1129090

- Perkins RB, Fisher-Borne M, Brewer NT. Engaging parents around vaccine confidence: proceedings from the national HPV vaccination roundtable meetings. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1639–40. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1520592.

- Sundstrom B, Cartmell KB, White AA, Russo N, Well H, Pierce JY, Brandt HM, Roberts JR, Ford ME. HPV vaccination champions: evaluating a technology-mediated intervention for parents. Front Digit Health. 2021;3:636161. doi:10.3389/fdgth.2021.636161.

- Karafillakis E, Peretti-Watel P, Verger P, Chantler T, Larson HJ. The role of maturity in adolescent decision-making around HPV vaccination in France. Vaccine. Sep 24 2021;39(40):5741–47. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.08.096.

- Berenson AB, Laz TH, Hirth JM, McGrath CJ, Rahman M. Effect of the decision-making process in the family on HPV vaccination rates among adolescents 9-17 years of age. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(7):1807–11. doi:10.4161/hv.28779.

- Gamble HL, Klosky JL, Parra GR, Randolph ME. Factors influencing familial decision-making regarding human papillomavirus vaccination. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010 Aug;35(7):704–15. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsp108.

- Alexander AB, Stupiansky NW, Ott MA, Herbenick D, Reece M, Zimet GD. Parent-son decision-making about human papillomavirus vaccination: a qualitative analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12(1):192. [Accessed 2012 Dec 14]. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-12-192.

- Herman R, McNutt LA, Mehta M, Salmon DA, Bednarczyk RA, Shaw J. Vaccination perspectives among adolescents and their desired role in the decision-making process. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1752–59. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1571891.