Abstract

Recent years have seen an increasing amount of self-reflective discussion among media and communication scholars, about the hegemonic structures and inclusive participation within the field. In the scholarly community of journalism studies, similar reflections have emerged in recent years. Digital Journalism has also been actively pursuing a diverse and equitable scholarship in its journal. As part of the 10th anniversary issue of Digital Journalism, this article offers a systematic diagnosis of the diversity within published journalism scholarship between 2013 and 2021. In total, 3068 publications from a group of five journalism journals—Digital Journalism, Journalism, Journalism Studies, Journalism Practice, Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly—were analysed. The operationalisation of ‘diversity’ focuses on both the authorship and content levels. Findings from this study suggest that (1) Digital Journalism published research papers mostly from and on the Global North, (2) the gender distribution of corresponding authors in the journal is slightly less balanced than the group average, (3) the methodological approaches employed in Digital Journalism are more asymmetric towards quantitative and computational approaches in comparison to the group average. Based on the empirical evidence, this article makes several recommendations to Digital Journalism, and to the field at large, to achieve better equity and inclusiveness.

Introduction

Recent years have seen an increasing amount of self-reflective discussion from media and communication scholars about the field’s hegemonic structures and inclusive participation (Chakravartty et al. Citation2018; Hirji, Jiwani, and McAllister Citation2020; Ng, White, and Saha Citation2020; Murthy Citation2020). In the scholarly community of journalism studies, similar reflections have emerged in recent years (Hess et al. Citation2019; Tandoc et al. Citation2020; Usher Citation2019). Nikki Usher’s (Citation2019) keynote #JStudiesSoWhite, a call for equitable and inclusive journalism scholarship, is a case in point.

Launched in 2013, Digital Journalism is one of the newest major journalism journals. Since its launch, inclusiveness has been at the centre of the core beliefs and mission of its editorial team (Steensen and Westlund Citation2021; Tandoc et al. Citation2020). From introducing international engagement editors, to diversifying the composition of its editorial board (Steensen and Westlund Citation2021), and from its multilingual newsletter to its special issues dedicated to scholarship from underrepresented minority groups and topics (e.g., Appelgren, Lindén, and van Dalen Citation2019; Mitchelstein and Boczkowski Citation2021), Digital Journalism has demonstrated a commitment to and vision for equitable participation. As part of the 10th anniversary issue of Digital Journalism, this article measures, compares, and prognosticates on the development of diversity in five major journalism journals: Digital Journalism, Journalism, Journalism Studies, Journalism Practice, and Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly.Footnote1

Inclusiveness and diversity are important for journalism scholarship, as they bring insightful and contextualised knowledge and advance theoretical development. Inclusiveness is key to generating journalism scholarship endorsing global perspectives. With the globalisation of journalistic practices and proliferation of transnational crises, journalism from around the world has become increasingly interconnected and interdependent (Cottle Citation2019). This trend requires more journalism research employing the epistemology of the global outlook, which “seeks to understand and explain how economic, political, social and ecological practices, processes and problems in different parts of the world affect each other, are interlocked, or share commonalities” (Berglez Citation2008, 847).

On the other hand, inclusiveness allows journalism scholarship to focus more on particular local experience and move beyond the Euro-American scholarly silos (Schoon et al. Citation2020). Moving beyond Western-centrism is to decolonise the field of academia and give a voice to researchers from the periphery, which is not merely analogous to using the Global South as a place for data collection and theory testing. The practices, constitutions, and significances of journalism in the Global South can have their own particularities and require indigenous conceptualisation and approaches (Baum and Zhukov Citation2019; Tully et al. Citation2022; Zeng, Burgess, and Bruns Citation2019). Despite their being disregarded by the mainstream, theoretical and methodological developments from the “peripheral” south are intellectually rigorous and important in advancing the field (Burgess and Bruns Citation2020; Connell Citation2020; Chen Citation2010).

However, the imbalance of the field goes beyond geographical diversity. Gender representation and the diversity in research approaches are also part of the discussion of issues relating to inclusiveness in journalism research (Cushion Citation2008; Hanusch and Vos Citation2020; Tandoc et al. Citation2020). More balanced gender representation is not merely an issue of equity, but also enhances knowledge production (Nielsen et al. Citation2017). Earlier studies show that gender diversity increases collective intelligence and facilitates problem solving in scientific teamwork (Woolley et al. Citation2010). Research has also suggested that due to the distinct but often complementary viewpoints and areas of interest between male and female researchers, gender diversity can lead to stronger research output and innovative discoveries (Joshi Citation2014; Nielsen et al. Citation2017; Søraa et al. Citation2020). Within journalism research, though earlier evidence revealed an underrepresentation of female authors (Cushion Citation2008), more updated investigation is necessary to establish the current gender dynamic. Additionally, the scholarly communities’ pursuit of inclusiveness should also consider methodological approaches. In order to keep pace with the fast-changing inquiries of journalism research, as well as to understand multifarious local contexts, diverse and innovative methodologies are required but have been found to be underdeveloped in prior studies (Karlsson and Sjøvaag Citation2016; Steensen et al. Citation2019).

Emphasising the aspects of scholarly inclusiveness mentioned above, this article offers a systematic diversity audit of five journalism journals. In total, 3068 papers published between 2013 and 2021 are analysed. It is worth noting that the current study intends neither to use a competitive lens for ranking these five journals nor to serve as a publicity stunt for DJ. This article’s intention is to use empirical evidence to shed light on how diversity has been tackled in these journals and, in turn, make recommendations for improvement. Furthermore, as the study concentrates on English-language international journals without specific geographic focus, there are several successful journalism journals that are not included in the analysis. Examples include African Journalism Studies, Journalism & Communication (新闻与传播研究), Chinese Journal of Journalism and Communication, and Comunicar. These journals have stronger regional foci and play an important role in promoting and further advancing scholarship from underrepresented scholarly communities.

Literature Review

De-Westernising Journalism Studies

Western-centrism reinforces the hegemony of the privileged and scholarly inequality. In the field of journalism studies, as well as in the broader fields of media and communication studies, the power disparity between the Global North and the Global South has been discussed critically for years (Chakravartty et al. Citation2018; Chan, Zeng, and Schäfer Citation2022; Ng, White, and Saha Citation2020; Murthy Citation2020). In a systematic interdisciplinary review of publications, Demeter (Citation2019) found that although regional disparities between the Global North and the Global South exist in every discipline, media and communication studies have a particularly high level of inequality, with the Global North contributing to 93% of all publications in the field. Evidence from other research has also revealed how the legacy of colonialism continues to impact development in the field of academia in Africa (Schoon et al. Citation2020), Asia (Ullah Citation2014), and Latin America (De Albuquerque Citation2019).

The scholarly inequality between the Global North and the Global South is not only materialistic but also epistemological. The academic system, especially in the social sciences and humanities, favours narratives that endorse Western ideology and epistemology. Scholars from the hegemonic centre (i.e., Western Europe and the United States) are often contemptuous of indigenous theories and ausländische approaches from the peripheral south (Gunaratne Citation2010). At the same time, it is not uncommon to see media scholars make universalistic claims with evidence from a handful of Western countries, which could then be applied to make sense of “the rest” of the world (Curran and Park Citation2000; Willems Citation2014).

When it comes to journalism studies—a field with strong ambitions to incorporate the global outlook, it is particularly important to acknowledge the plurality of epistemologies. However, earlier evidence reveals the overwhelming dominance of Euro-American regions. In a review of publications in J and JS from 2000 to 2007, Cushion (Citation2008) pointed out that the United States and the United Kingdom alone contributed to over 65% of all articles published in journalism study journals. Cushion (Citation2008) concluded that despite the rapid development of journalism studies, scholarship is “largely seen and understood through the US and UK prism” and that the internationalisation of scholarship “remains an ambition rather than a reality” (291). Since the publication of Cushion’s review, journalism studies have continued to accelerate, and more journals have been launched (e.g., DJ). So how has the dominance of the “US and UK prism” developed in the last few years? To generate insights from this question, this study first asks:

RQ1: How did international diversity in authorship evolve in journalism studies between 2013 and 2021?

RQ2: To what extent did the regional foci in journalism research diversify between 2013 and 2021?

Gender Balance

When discussing the concept of diversity in scholarship, gender equality is also an important issue to explore. Accumulated findings from literature have shown that female scholars are faced with more obstacles, biases, and discrimination than their male peers. Such forms of inequality have been discussed in relation to areas such as career promotion (Meyers Citation2013; Goastellec and Pekari Citation2013), grant applications (Witteman et al. Citation2019), and even the process of peer reviewing (Helmer et al. Citation2017; Lundine et al. Citation2019).

As shown in previous studies, the underrepresentation of women is most prominent in scientific, technological, engineering, and mathematical disciplines, whereas female researchers are much more visible in the social sciences and humanities (Casad et al. Citation2021; Vásárhelyi et al. Citation2021). This seemingly balanced gender distribution in the social sciences and humanities is superficial. Although there is often a large representation of women at the graduate student and junior faculty levels, men continue to dominate senior positions (Goastellec and Pekari Citation2013). With regards to research output, research has also revealed that male researchers tend to have longer careers, have greater outputs, and that their work often attains a higher level of reach and citation than that of their female counterparts (Huang et al. Citation2020; Gabster et al. Citation2020; Vásárhelyi et al. Citation2021). Focussing on journalism research, Cushion (Citation2008) assessed the representation of female authors in two major journalism journals. The results showed that men represented two thirds of the authors and Australia had the most balanced gender ratio, where women authors accounted for 45% (in Europe, men accounted for 70%). In line with Cushion’s (Citation2008) investigation and using our more updated and encompassing dataset, we assess gender-related diversity with the following question:

RQ3: How did the representation of women in authorship vary between 2013 and 2021 across regions?

Methodological Perspective

Multidisciplinarity is an important characteristic of journalism studies (Peters and Broersma Citation2019; Steensen and Westlund Citation2021), which makes diversified methodological perspectives particularly relevant. However, accumulated evidence has revealed a homogeneity and a lack of creativity in the methodologies employed in journalism studies (Hanusch and Vos Citation2020; Witschge, Deuze, and Willemsen Citation2019; Riffe and Freitag Citation1997). For example, quantitative content analysis is by far the most commonly applied method in journalism studies (Hanusch and Vos 2020). Steensen et al. (Citation2019) analysis of publications in DJ showed a high level of interdisciplinary diversity but highlighted that such diversity had not been translated into diverse analytical approaches. Publications in the journal remain dominated by (semi-)quantitative methods, especially manual content analysis (Steensen et al. Citation2019; Steensen and Westlund Citation2021). Steensen et al. (Citation2019) stated that digital journalism research can benefit from incorporating methodological advances from computer science, informatics, and information science.

Since Steensen et al. (Citation2019) review, digital journalism scholars, especially that from the Global North, have taken an active role in implementing computational methods (De Grove, Boghe, and De Marez Citation2020; Günther and Quandt Citation2016; Madrid-Morales Citation2020; Hase, Mahl, and Schäfer Citation2022). For innovative journalism research, computational methods have a lot to offer. For example, they allow researchers to retrieve and analyse digital data on a large scale. In DJ’s first issue, Flaounas et al. (Citation2013) showcased the potential of applying data mining and natural language processing techniques to analyse over two million online news articles. Traceable online activities also allow researchers to study individuals’ consumption of news without relying on self-reported data (Vermeer et al. Citation2020).

Despite these aforementioned benefits, computational methods should not be celebrated or normalised without caution. It is crucial to acknowledge that no single approach should be perceived as privileged and that overselling computational methods can be even detrimental to the field’s pursuit of more inclusive scholarship. The so-called computational turn risks promoting normativity that devalues other methodological traditions, which in turn results in a skewed appreciation of institutions and individuals with technological resources (e.g., Boyd and Crawford Citation2012; Schoon et al. Citation2020; Steensen and Westlund Citation2021).

The normalisation of scholarly practices should always consider the digital materiality and infrastructure of the Global South (Dutta et al. Citation2021; Schoon et al. Citation2020). Universities and researchers from the Global South have relatively limited access to the financial investment and infrastructure required for computational methods. For example, proprietary social media data, which is a raw material of many computational journalism studies, is becoming increasingly exclusive to certain already privileged researchers and institutions (Bruns Citation2019). Moreover, due to the gender gap in computational methods trainings (Gatto et al. Citation2020), to blindly normalise computational approaches can lead to what Miltner (Citation2019, 164) described as a “gendered technological underclass” within the journalism research community. Employing such critical viewpoints to research methods, our fourth research question asks:

RQ4: How did methodological diversity develop between 2013 and 2021?

Data and Methods

Data Collection

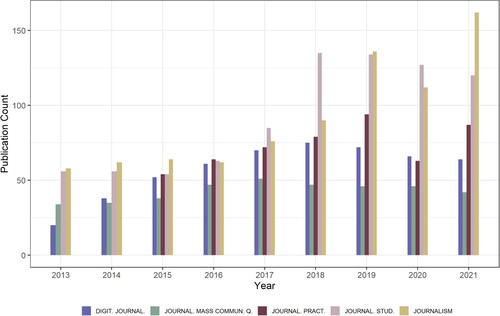

From Web of Science, we collected all articles published in the five selected journalism journals from one January 2013 to 31 December 2021. The time frame began in 2013 as that was when the first issue of DJ was published. The dataset included 3068 articles, and the yearly distribution of these articles is presented in .

Variables

In line with the four proposed research questions, four key variables were extracted from our analysis.

Author-Level International Diversity

In total, 1275 unique corresponding authors were identified in the dataset. We extracted information about their countries from the address field of the Web of Science data. This information reflected the researchers’ locations when the work was undertaken, rather than their nationalities, ethnicities, or countries of origin.

Content-Level International Diversity

We detected the possible geographical foci of all abstracts using Watanabe’s (Citation2018) semi-supervised Newsmap algorithm. This method only works when the abstract writer(s) explicitly mentions the regional context of the study. Usually, studies about non-Western contexts are more likely to explicitly spell out the geographical context (Rojas and Valenzuela Citation2019). We expected that this approach might have a high precision but probably a low recall.

Assignment of a Probabilistic Gender to the Corresponding Author’s Name

We applied a similar method used by Wang et al. (Citation2021) to assign a probabilistic gender to the corresponding author based on their name. The method was based on the first name of the corresponding author and checked against statistics from the United States on the gender of first names (Blevins and Mullen Citation2015). Four hundred and forty-six authors, whose first names were unavailable in the statistics, were checked manually using the same method used by Trepte and Loths (Citation2020), which involved checking the picture found online. Limitations of this approach are reflected upon in the last section of the paper.

Methodological Diversity

We used a dictionary-based approach to determine the possible methodological approaches of the studies. Based on prior literature (e.g., Hase, Mahl, and Schäfer Citation2022), we created a dictionary to detect quantitative and computational approaches (). This approach assumed that the abstract writer(s) explicitly mentioned the methodological approach.

Table 1. Dictionary entries used to detect quantitative and computational approaches in abstracts.

Calculation of Diversity Metrics

For the two geographical variables associated with countries (i.e., author-level internationality and content-level internationality), we calculated a Simpson’s Index of Diversity (McDonald and Dimmick Citation2003). The calculation of this index considered both the richness and the evenness of elements (i.e., countries in this case). The former referred to the total number of countries, and the latter measured the relative abundance of each country category (i.e., how many authors belonged to each country). This value varied between 0 and 1, and the larger the number, the greater the regional diversity in the authorship. For binary variables, we calculated the proportion of interest (e.g., the proportion of female corresponding authors and the proportion of quantitative studies). We generated the annual time series of diversity metrics. To avoid employing a “horse race” frame to directly compare journals against each other with numerical results, our interpretation of findings focussed on the group’s collective performance and DJ. We used all five journals to calculate the group’s diversity metrics.

Findings

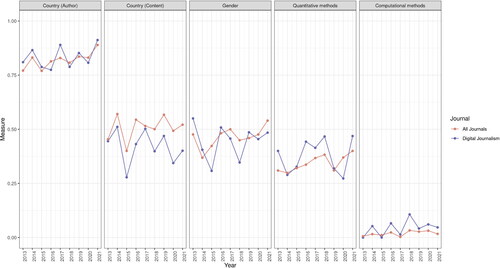

In this section, we present findings from our analysis and discuss them in relation to the four research questions that we proposed in the “Literature review” section. In , the group’s diversity indices and DJ are shown.

Figure 2. Diversity indices of all included journalism journals (pink) and Digital Journalism (purple) according to country (author), detected country (content), detected gender (author), detected quantitative methods, and detected computational methods.

Author-Level International Diversity

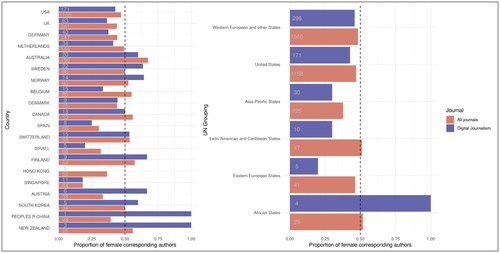

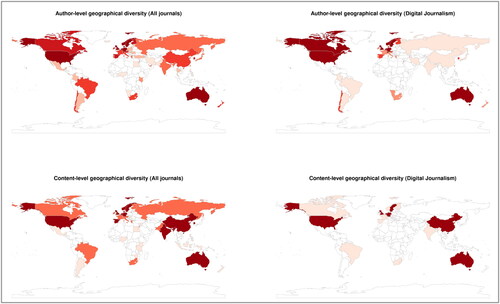

In terms of the internationality of authorship, the five journals together show a steady increase in the geographical diversity of authorship. As shown in , a significant increase has been observed since 2020. As previously mentioned, the diversity index measured both the richness (how many countries were represented) and the evenness (the relative distribution of countries). In general, DJ’s diversity index score in author-level internationality is on par with the group. When considering the richness alone, 64 countries are represented in all five journals together (). However, the distribution of scholarship is highly uneven. As shown in , authors located in the three Anglophone countries (i.e., the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia) are dominant. They account for 1159 (38%), 341 (11%), and 150 (5%) of the papers in our data, respectively. In the fourth and fifth places are the two Western European countries: Germany (n = 147, 4.8%) and the Netherlands (n = 144, 4.7%). All together, these top five countries contribute to 63% of the publications. The first non-Western region, Hong Kong, can only be seen in 15th place. shows the top 10 most represented countries in each journal. As the results illustrate, in all five journals, corresponding authors from the United States account for more than 30% of scholarship.

Figure 3. International diversity at the author level (top left: all five journals, top right: Digital Journalism) and content level (bottom left: all five journals, bottom right: Digital Journalism).

Table 2. The top 15 most represented countries in the five journals’ authorship.

Table 3. The top 10 most represented countries for each journal.

Steensen and Westlund (Citation2021) review of publications in five journalism journalsFootnote2 (2013–2019) revealed that DJ had the highest level of Western-centrism. According to our findings, such Western-centrism remains salient in the journal. As shown in and , Western countries dominate DJ’s scholarship: the United States (171, 33%), the United Kingdom (63, 12.1%), Germany (40, 7.7%), the Netherlands (34, 6.6%), and Sweden (22, 4.3%). In contrast, only four papers published in DJ have a corresponding author from Africa (two from Namibia and South Africa, respectively). Moreover, DJ’s publications represent 41 countries, which make it the second lowest in terms of richness of all of the journals.Footnote3 Despite the visible Western-centrism, the journal’s aforementioned efforts to increase its internationality may have brought about some changes. For instance, the last two years have seen a significant growth in DJ’s diversity index, with DJ performing better than other journals in the group.

Content-Level International Diversity

At the content level, from 2013 to 2021, little progress in international diversity can be seen. As shown in , the diversity index has gone downwards in the last couple of years. One possible explanation for this trend is the focussing of journalism research on some highly US-centric phenomena (e.g., so-called fake news and Donald Trump’s presidency that began in 2016).Footnote4 When we compare DJ with the collective performance of all five journals, our analysis suggests that there is a lot of room for the journal to improve. DJ’s content-level international diversity is consistently lower than the group average (see and ). For all journals from our dataset, case studies relating to the United States represent the majority (69.5%), but such US-centrism is particularly visible in DJ, where US-related studies account for about 76% of publications. Moreover, our analysis of country richness in research content reveals that DJ only features 18 countries, which is the second lowest in the groupFootnote5.

Gender Representation in Authorship

As previously mentioned, in comparison to the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, the social sciences and humanities generally perform better in terms of gender equality, at least at a superficial level (the number of female scientists). Our analysis of all five journals shows that the representation of female authors is higher than 54% in 2021 but stands at 47% for the entire period. At the same time, as shown in , the temporal development of the gender disparity seems to be stagnant across time (i.e., there is no longer any improvement). We do not have direct explanations for this phenomenon, but one important factor to consider is the change in the natural distribution of the genders of journalism scholars. In certain countries (e.g., the United Kingdom, Germany, and Israel), according to the membership statistics compiled by Trepte and Loths (Citation2020), there are more male than female members registered in the communication associations of the respective countries. If we consider the annual report from the International Communication Association (ICA), we can also see a decline in the representation of females in authorship in the last decade. Worth noticing, the gender diversity of corresponding authors whose articles are published in DJ is slightly lower than the group average (47%), with 44% of authors being femaleFootnote6.

Another important insight from our analysis concerns the regional difference. shows two plots that display the gender distribution (1) across the top-most represented countries and (2) across five regions according to the United Nations’ categorisation of states.Footnote7 In both plots, we use two separate bars to represent DJ (purple) and all five journals as a whole (pink). Unlike Cushion’s (Citation2008) finding that there are more male authors across all countries, our results identify several countries with more female authors, such as Australia, New Zealand, Switzerland, Norway, Finland, and Belgium.

Methodological Diversity

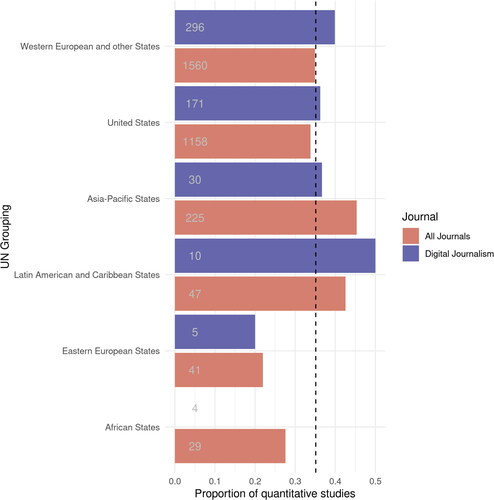

In DJ, 38.2% of publications are labelled as quantitative studies, whereas the group average is 35.1%.Footnote8 Since 2017, the percentage of quantitative methods in DJ has consistently exceeded the group (). shows the proportion of quantitative studies across six regions. As shows, quantitative studies are less common in Africa and Eastern Europe.

Figure 5. Proportion of quantitative studies across six regions. Countries are grouped based on the United Nations’ categorisation of states. The dotted line shows the group average: 35.1%.

With regard to computational methods, the overall presence of such new methodological approaches is burgeoning but still marginal. When considering all five journals, about 2% of studies employ computational methods (). DJ has the highest prevalence of computational methods, with about 5% of publications utilising one or more computational techniques. Findings from our analysis reveal that the vast majority of computational methods papers come from the Global North. Using our keywords (), we determined that all 25 computational methods papers published in DJ, excepting one from Chile, were from the Global North. Germany and the Netherlands took the lead, with each contributing five papers (i.e., 20% each).

Discussion and Recommendations

Expanding Global Diversity in Authorship

As the findings of the regional diversity index reveal, scholarship in DJ presents a level of Western-centrism that is similar to that of other selected journals. However, with regard to regional richness, countries represented in DJ are more limited when compared to the group average. Being the youngest journal among the five chosen journals also means that DJ has had a shorter amount of time to accumulate a broad coverage of regions in its scholarship. DJ’s recent appointment of international engagement editors in South America and Southeast Asia can be considered an important step in catching up with other journals, and such efforts could also be expanded to encompass more underrepresented regions, such as South Asia and Africa ().

Another measure that academic journals have employed widely in order to achieve more internationality is to increase the diversity of editorial boards and leadership teams by including researchers from underrepresented groups. However, any attempts to diversify editorial teams should have the aim of delivering real changes, without which such measures are nothing but tokenism. Tokenism can be defined as making cosmetic gestures by including individuals with specific traits, without giving them real influence or meaningful roles (Núñez, Rivera, and Hallmark Citation2020). To ensure journals’ measures to increase diversity are not tokenistic, minority board members should be given more voice and involvement in decision-making processes.

Journals need to improve their transparency and efficacy measurements. For instance, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) surveys should be regularly conducted and communicated. In this regard, ICA’s (2022) survey conducted by the Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Access Standing Committee is a good example. Such self-reported information from authors can also facilitate rigorous empirical research. For instance, demographic data allows researchers to approach and operationalise the concept of diversity with intersectional perspectives. In this context, intersectional perspectives refer to analytical strategies incorporating critical insights such as that “race, class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, nation, ability, and age operate not as unitary, mutually exclusive identities, but as reciprocally constructing phenomena that in turn shape complex social inequalities” (Collins Citation2015, 2). When examining intersectionality attributes of scholars, data regarding the authors’ race/ethnicity, gender, parental and socioeconomic status, and physical ability are particularly informative. However, in reality, such data is rarely available. Researchers relying on limited metadata from online databases have to compromise their analysis by using proxies and estimation. As exemplified by the current paper, without author information, we had to omit the analysis of ethnic/racial diversity and reduce gender analysis to the binary definitions of male and female. Such challenges can be tackled, at least partially, by collaborative efforts between journals and researchers.

Expanding the Scope of Digital Journalism Studies

Compared with the collective performance of all five journals under study, DJ’s research scope demonstrates a greater Euro-American-centrism. One factor linked to this asymmetry in scholarship is the Western-centric definition of core issues in digital journalism as a research topic. For instance, the four digital journalism issues that Steensen and Westlund (Citation2021) suggested are the shift in revenue model, an increased emphasis on user data and audience analytics, a shift in distribution pattern, and susceptibility to manipulation and falsehood. These issues are undoubtedly important, but whether they are actually global issues is debatable. For example, the idea that the survival of journalism depends on its revenue model suggests the “North Atlantic” liberal model of media in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Ireland (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004). Large comparative journalism research studies, such as the Reuters Institute Digital News Report and Worlds of Journalism Study, suggest that the issues threatening the survival of (digital) journalism around the world extend beyond revenue-related factors (Hanitzsch et al. Citation2019; Newman et al. Citation2022). For example, the closure of several profitable online news outlets in Hong Kong between 2021 and 2022 was unrelated to revenue but was instead linked to political struggles in the region.

There have been several calls to internationalise the scope of digital journalism in DJ. The Digital Journalism Studies Compass (Eldridge et al. Citation2019) is a welcome attempt to redefine the field with a more global outlook. Special issues with comparative and regional scopes, such as Data Journalism Research: Studying a Maturing Field (Volume 7, Issue 9) and Digital Technologies and the Evolving African Newsroom: Towards an African Digital Journalism Epistemology (Volume 2, Issue 1), contain research from, as well as on, traditionally underrepresented parts of the world. We strongly advocate DJ’s revisiting of the 2019 special issue Defining Digital Journalism Studies (Volume 7, Issue 3) to explore new definitions of the field with more input from scholars from underrepresented communities.

Promoting Gender Sensitivity

Findings from our analysis show that when considering all five journals together, female researchers were more regularly appointed as corresponding authors than male researchers in 2021. However, in DJ, male corresponding authors continue to dominate.

In comparison to other forms of social bias, such as linguistic, regional, and institutional biases, academic journal editors are much more reluctant to acknowledge gender bias as an issue (Lundine et al. Citation2019). We hope that findings from our analysis could provide more incentives for the leadership of DJ to further improve gender-related fairness and equity in the journal. To do so, it is not enough to monitor the representation of female authors. First authorship and corresponding authorship must be monitored and even cross-checked. In our field, women are highly visible in junior positions, such as research assistants and PhD students. They play an active role in contributing to scholarship but are less likely to be in key author positions. In publications, they often end up in a less privileged position in the order of authors, with senior male colleagues occupying the prime positions (Ouyang et al. Citation2018).

It is worth pointing out that there are structural reasons behind this practice. For instance, in some systems (e.g., Universities in China) the evaluation of individual academics often considers their publications only when they are the first author or the corresponding author. Hence, the first authorship and corresponding authorship are commonly split, usually with senior male professors occupying the corresponding author position (Li Citation2013). The corresponding authorship should be allocated in a transparent and standardised matter, because it entails pragmatic responsibilities and has strong symbolic meaning (Fox, Ritchey, and Paine Citation2018). Failing to do so devalues the contribution of other authors, including the first author (Bhandari et al. Citation2014). To make the allocation of authorship fairer, the journal could implement better guidelines and encourage the inclusion of contribution statements to clarify how the authorship is distributed (Fox, Ritchey, and Paine Citation2018).

Furthermore, during the peer reviewing process, editors and reviewers could have more gender sensitivity. As Lundine et al. (Citation2019, 7) argued, to be “gender blind” in the publication system is “to remain unaware of the role of power and positionality, and perhaps more problematically, to inadvertently perpetuate systems of structural gender inequities.” Academic journals must ensure a balanced representation of female peer reviewers and editorial teams. In certain circumstances, journals should grant female authors, as well as reviewers, greater time flexibility. Women’s productivity is generally more prone to being adversely affected by external events. For instance, Gabster et al. (Citation2020) study of academic activities and autoethnographies by Blell, Liu, and Verma (Citation2022) during the COVID-19 pandemic showed that productivity and scientific output of women, and in particular women of colour, were disproportionately affected. The damage wrought by the pandemic could be translated into cumulative disadvantage (Blell, Liu, and Verma Citation2022). The timeframe for our data collection ended in 2021. Considering the lag due to the long publication cycle, findings from this study cannot accurately reflect the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on women’s academic productivity. We may soon see a reversal of the recent improvements in gender balance in journalism journals (), which makes the need for measures to promote gender equality particularly urgent.

Another aspect of gender sensitivity in the peer reviewing process that is rarely addressed, concerns protecting females from potential risk. Female academics can more easily fall victim to online bullying and harassment (Mortensen Citation2018). During the peer reviewing process, academic journals should be aware of the need to protect female authors from such harm. One concrete example comes from one of the authors’ own experiences of being an editor. During the peer review of a paper studying extremist groups online, one of the reviewers requested that the authors share the names of the groups studied. Although the reviewer made the request with good intentions, the authors rightly raised their concerns that revealing the names of these groups could expose authors, most of whom were female junior researchers, to potential harm. In a case such as this, the editors must mediate the process and prioritise the safety of the authors. This is just one example of a scenario in which the editorial team’s gender sensitivity is needed to protect female authors. This example also reveals a blind spot in our peer reviewing system that is too often overlooked. With ever increasing levels of online harassment and the growing visibility of scholars online, research institutions and journals should implement more policies and guidelines to safeguard vulnerable researchers.

Developing Methodological Diversity

In an earlier review, Steensen and Westlund (Citation2021, 70) point out that despite the relatively low visibility of computational methods, digital journalism research is “increasingly geared towards computation and big data.” Our finding suggests that DJ is now taking the lead in computational journalism research and is emerging as an important outlet for methods papers. Special issues focussing on methodological reflections about computational techniques have been featured in the journal (e.g., Karlsson and Sjøvaag Citation2016). The semi-supervised machine learning technique used in the paper—“Newsmap” (Watanabe Citation2018)—is another prime example. As it is an interdisciplinary journal focussing on digitalisation and technological innovations’ interplay with journalism, it is unsurprising that DJ is more attuned to computational and digital techniques than journals with a general focus on journalism.

Irrespective of the relevance of computational and data-driven research for digital journalism research, DJ should avoid normalising its perceived superiority. As previously mentioned, qualitative studies are already underrepresented in journalism research (Hanusch and Vos Citation2020; Steensen et al. Citation2019). The hype surrounding computational methods risks further marginalising qualitative and critical methods and diverting the attention of researchers away from important research investigations still to be conducted in digital journalism (see Steensen and Westlund (Citation2021) discussion). Moreover, as discussed in the “Methodological perspective” section, the normalisation of computational approaches can undermine the community’s pursuit of inclusiveness and equity, due to disparities in resources available to individuals and institutions around the globe. This concern is supported by the study. Our analysis reveals that the vast majority of computational methods papers come from the Global North.

For DJ, more focus should be given to proposing hybrid approaches that incorporate theoretical advances and contextual insights. To this end, researchers from the Global South are making important contributions to the incorporation of computational methods with indigenous approaches and theories (Burgess and Bruns Citation2020; Madrid-Morales Citation2020), which further showcases the significance of expanding scholarship beyond the European and North American silos. The journal could feature more work on and dedicate special issues to coverage of this emerging research area. Burgess and Bruns (Citation2020) special issue “Digital Methods in Africa and Beyond: A View from Down Under” in African Journalism Studies is a good example of such an initiative.

Lastly, DJ could help to ameliorate the difficulties that underprivileged researchers face when applying computational methods. For instance, one problem associated with computational text analysis, as Baden et al. (Citation2022) identified, is the field’s heavy focus on English and Germanic languages. Similar to those of the special issues Rethinking Research Methods in an Age of Digital Journalism (Volume 4, Issue 1) and the upcoming Analytical Advances through Open Science, innovative textual analysis methods for widely read but poorly studied journalistic texts in languages such as Hindi, Swahili, and Arabic should be actively called for.

Conclusion and Limitations

Focussing on journalism studies, this article discusses five leading journals’ diversity initiatives at both the authorship and content levels. Findings from the paper reveal (1) that DJ publishes research papers mostly from and about the Global North, (2) that DJ’s gender distribution of corresponding authors is slightly more imbalanced than other journals, and (3) that the methodological approaches employed in DJ favour quantitative and computational methods more than other journals.

Historically, as Dutta et al. (Citation2021) pointed out, the broad fields of media and communication studies are “mired in the politics of whiteness, with journals and disciplinary organisations serving as sites of knowledge circulation that perpetuate whiteness” (p.805). Despite growing advocacy for diversity in scholarly communities, Dutta et al. (Citation2021) remarks remain relevant, as they highlight journals’ responsibilities towards and impacts on improving scholarly equality, diversity, and inclusiveness. For DJ to better contribute to the diversification of journalism studies, it should take more concrete actions, and we have suggested several.

This study has several limitations. First, our operationalisation of diversity is rather narrow. There are other important dimensions of diversity that our analysis could not incorporate, such as race, ethnicity, nationality, and discipline. With access to more informative author data, future studies can better operationalise diversity and apply an intersectional lens to investigate scholarly inequality (see discussion in the “Expanding global diversity in authorship” section). Second, our analysis only categorises authors into female and male genders. In future studies, it will be important to expand the categories to reflect non-binary gender identities. As mentioned in the previous section, such data could be collected through EDI surveys. In addition, future diversity audits should incorporate more qualitative insights. Although most review studies rely on quantified findings to identify inequality and biases in scholarship, they can be enhanced by qualitative approaches. For instance, interviews can provide more in-depth insights into the experiences of scholars and the hurdles they face (Hosseini and Sharifzad Citation2021).

Notes

1 Throughout the remainder of the paper, the five journals are referred to as DJ, J, JS, JP, and JMCQ.

2 Journalism practice, Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, Journalism, Journalism Studies, Digital Journalism.

3 The country richness numbers for the other four journals are JMCQ: 26, JP: 48, JS: 50, and J: 54.

4 An exploratory analysis of keywords in abstracts before and after 2016 showed that the terms “fake” and “Trump” were among the top 15 keywords of the post-2016 era.

5 Content-level richness for the other four journals are JMCQ: 17, JP: 24, JS: 32, J: 33.

6 The ratio of female authors in the other four journals is as follows: JMCQ (43%), JP (54.5%), JS (46.7%), and J (47.1%).

7 Link to the source: https://www.un.org/dgacm/en/content/regional-groups. The original grouping categorises the United States under “Western European and Other States.” Considering this country’s dominance in journalism scholarship, we list it on its own.

8 The proportion of quantitative methods detected in our dataset is as follows: J (27.5%), JS (34.5%), JP (33.9%), and JMCQ (49.6%).

References

- Appelgren, E., C.-G. Lindén, and A. van Dalen. 2019. “Data Journalism Research: Studying a Maturing Field across Cultures, Media Markets and Political Environments.” Digital Journalism 7 (9): 1191–1199.

- Baden, C., C. Pipal, M. Schoonvelde, and M. A. G. van der Velden. 2022. “Three Gaps in Computational Text Analysis Methods for Social Sciences: A Research Agenda.” Communication Methods and Measures 16 (1): 1–18.

- Baum, M. A., and Y. M. Zhukov. 2019. “Media Ownership and News Coverage of International Conflict.” Political Communication 36 (1): 36–63.

- Berglez, P. 2008. “What is Global Journalism? Theoretical and Empirical Conceptualisations.” Journalism Studies 9 (6): 845–858.

- Bhandari, M., G. H. Guyatt, A. V. Kulkarni, P. J. Devereaux, P. Leece, S. Bajammal, D. Heels-Ansdell, and J. W. Busse. 2014. “Perceptions of Authors’ Contributions Are Influenced by Both Byline Order and Designation of Corresponding Author.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67 (9): 1049–1054.

- Blell, M., S. J. S. Liu, and A. Verma. 2022. “Working in Unprecedented Times: Intersectionality and Women of Color in UK Higher Education in and Beyond the Pandemic. Gender, Work & Organization 30 (2): 353–372.

- Blevins, C., and L. Mullen. 2015. “Jane, John… Leslie? A Historical Method for Algorithmic Gender Prediction.” DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly 9 (3): 2.

- Boyd, D., and K. Crawford. 2012. “Critical Questions for Big Data: Provocations for a Cultural, Technological, and Scholarly Phenomenon.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (5): 662–679.

- Bruns, A. 2019. “After the ‘APIcalypse’: Social Media Platforms and Their Fight against Critical Scholarly Research.” Information, Communication & Society 22 (11): 1544–1566.

- Burgess, J., and A. Bruns. 2020. “Digital Methods in Africa and beyond: A View from down Under.” African Journalism Studies 41 (4): 16–21.

- Casad, B. J., J. E. Franks, C. E. Garasky, M. M. Kittleman, A. C. Roesler, D. Y. Hall, and Z. W. Petzel. 2021. “Gender Inequality in Academia: Problems and Solutions for Women Faculty in STEM.” Journal of Neuroscience Research 99 (1): 13–23.

- Chakravartty, P., R. Kuo, V. Grubbs, and C. McIlwain. 2018. “# CommunicationSoWhite.” Journal of Communication 68 (2): 254–266.

- Chan, C.-H., J. Zeng, and M. S. Schäfer. 2022. “Whose Research Benefits More from Twitter? On Twitter-Worthiness of Communication Research and Its Role in Reinforcing Disparities of the Field.” PLoS One 17 (12): e0278840.

- Chen, K. H. 2010. Asia as Method: Toward Deimperialization. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Collins, P. H. 2015. “Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemmas.” Annual Review of Sociology 41 (1): 1–20.

- Connell, R. 2020. Southern Theory: The Global Dynamics of Knowledge in Social Science. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Cottle, S. 2019. “Journalism Coming of (Global) Age, II.” Journalism 20 (1): 102–105.

- Curran, J., and M. J. Park. 2000. “Introduction.” In De-Westernizing Media Studies, edited by Curran, J., and M. J. Park. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Cushion, S. 2008. “Truly International?” Journalism Practice 2 (2): 280–293.

- De Albuquerque, A. 2019. “Protecting Democracy or Conspiring against It? Media and Politics in Latin America: A Glimpse from Brazil.” Journalism 20 (7): 906–923.

- De Grove, F., K. Boghe, and L. De Marez. 2020. “(What) Can Journalism Studies Learn from Supervised Machine Learning?” Journalism Studies 21 (7): 912–927.

- Demeter, M. 2019. “The Winner Takes It All: International Inequality in Communication and Media Studies Today.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 96 (1): 37–59.

- Dutta, M., S. Ramasubramanian, M. Barrett, C. Elers, D. Sarwatay, P. Raghunath, S. Kaur, et al. 2021. “Decolonizing Open Science: Southern Interventions.” Journal of Communication 71 (5): 803–826.

- Eldridge, S. A., K. Hess,E. C. Tandoc, andO. Westlund. 2019. “Navigating the Scholarly Terrain: Introducing the Digital Journalism Studies Compass.” Digital Journalism 7 (3): 386–403.

- Flaounas, I., O. Ali, T. Lansdall-Welfare, T. De Bie, N. Mosdell, J. Lewis, and N. Cristianini. 2013. “Research Methods in the Age of Digital Journalism: Massive-Scale Automated Analysis of News-Content—Topics, Style and Gender.” Digital Journalism 1 (1): 102–116.

- Fox, C. W., J. P. Ritchey, and C. T. Paine. 2018. “Patterns of Authorship in Ecology and Evolution: First, Last, and Corresponding Authorship Vary with Gender and Geography.” Ecology and Evolution 8 (23): 11492–11507.

- Gabster, B. P., K. van Daalen, R. Dhatt, and M. Barry. 2020. “Challenges for the Female Academic during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” The Lancet 395 (10242): 1968–1970.

- Gatto, M., A. Gohdes, D. Traber, and M. Van der Velden. 2020. “Selecting in or Selecting out? Gender Gaps and Political Methodology in Europe.” PS: Political Science & Politics 53 (1): 122–127.

- Goastellec, G., and N. Pekari. 2013. “Gender Differences and Inequalities in Academia: Findings in Europe.” In The Work Situation of the Academic Profession in Europe: Findings of a Survey in Twelve Countries, edited by Teichler, U., and E. A. Höhle, 55–78. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Gunaratne, S. A. 2010. “De-Westernizing Communication/Social Science Research: Opportunities and Limitations.” Media, Culture & Society 32 (3): 473–500.

- Günther, E., and T. Quandt. 2016. “Word Counts and Topic Models: Automated Text Analysis Methods for Digital Journalism Research.” Digital Journalism 4 (1): 75–88.

- Hallin, D. C., and P. Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Hanitzsch, T., F. Hanusch, J., Ramaprasad, and A. S. De Beer, eds. 2019. Worlds of Journalism: Journalistic Cultures around the Globe. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Hanusch, F., and T. P Vos. 2020. “Charting the Development of a Field: A Systematic Review of Comparative Studies of Journalism.” International Communication Gazette 82 (4): 319–341.

- Hase, V., D. Mahl, and M. S. Schäfer. 2022. “Der „Computational Turn “: Ein „Interdisziplinärer Turn “? Ein Systematischer Überblick zur Nutzung der Automatisierten Inhaltsanalyse in der.” Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft 70 (1–2): 60–78.

- Helmer, M., M. Schottdorf, A. Neef, and D. Battaglia. 2017. “Gender Bias in Scholarly Peer Review.” eLife 6 (2017): 1–18.

- Hess, K., S. Eldridge, E. Tandoc, and O. Westlund. 2019. “Diversity in Digital Journalism.” Digital Journalism 7 (5): 549–553.

- Hirji, F., Y. Jiwani, and K. E. McAllister. 2020. “On the Margins of the Margins: #CommunicationSoWhite—Canadian Style.” Communication, Culture & Critique 13 (2): 168–184.

- Hosseini, M., and S. Sharifzad. 2021. “Gender Disparity in Publication Records: A Qualitative Study of Women Researchers in Computing and Engineering.” Research Integrity and Peer Review 6 (15): 3–16.

- Huang, J., A. J. Gates, R. Sinatra, and A. L. Barabási. 2020. “Historical Comparison of Gender Inequality in Scientific Careers across Countries and Disciplines.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (9): 4609–4616.

- International Communication Association, Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Access Standing Committee. 2022. “Perceptions about Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Access: First Insights.” https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.icahdq.org/resource/resmgr/newsletters/2022/ica_idea_report_on_membershi.pdf

- Joshi, A. 2014. “By Whom and When Is Women’s Expertise Recognized? The Interactive Effects of Gender and Education in Science and Engineering Teams.” Administrative Science Quarterly 59 (2): 202–239.

- Karlsson, M., and H. Sjøvaag. 2016. “Introduction: Research Methods in an Age of Digital Journalism.” Digital Journalism 4 (1): 1–7.

- Li, Y. 2013. “Text-Based Plagiarism in Scientific Writing: What Chinese Supervisors Think about Copying and How to Reduce It in Students’ Writing.” Science and Engineering Ethics 19 (2): 569–583.

- Lundine, J., I. L. Bourgeault, K. Glonti, E. Hutchinson, and D. Balabanova. 2019. “‘I Don’t See Gender”: Conceptualizing a Gendered System of Academic Publishing.” Social Science & Medicine 235 (2019): 112388–112389.

- Madrid-Morales, D. 2020. “Using Computational Text Analysis Tools to Study African Online News Content.” African Journalism Studies 41 (4): 68–82.

- McDonald, D. G., and J. Dimmick. 2003. “The Conceptualization and Measurement of Diversity.” Communication Research 30 (1): 60–79.

- Meyers, M. 2013. “The War on Academic Women: Reflections on Postfeminism in the Neoliberal Academy.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 37 (4): 274–283.

- Miltner, K. M. 2019. “Girls Who Coded: Gender in Twentieth Century UK and US Computing.” Science, Technology & Human Values 44 (1): 161–176.

- Mitchelstein, E., and P. J. Boczkowski. 2021. “What a Special Issue on Latin America Teaches Us about Some Key Limitations in the Field of Digital Journalism.” Digital Journalism 9 (2): 130–135.

- Mortensen, T. E. 2018. “Anger, Fear, and Games: The Long Event of #GamerGate.” Games and Culture 13 (8): 787–806.

- Murthy, D. 2020. “From Hashtag Activism to Inclusion and Diversity in a Discipline.” Communication, Culture and Critique 13 (2): 259–264.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, C. Robertson, K. Eddy, and R. Nielsen. 2022. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2022.

- Ng, E., K. C. White, and A. Saha. 2020. “# CommunicationSoWhite: Race and Power in the Academy and beyond.” Communication, Culture & Critique 13 (2): 143–151.

- Nielsen, M. W., S. Alegria, L. Börjeson, H. Etzkowitz, H. J. Falk-Krzesinski, A. Joshi, E. Leahey, L. Smith-Doerr, A. W. Woolley, and L. Schiebinger. 2017. “Gender Diversity Leads to Better Science.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (8): 1740–1742.

- Núñez, A. M., J. Rivera, and T. Hallmark. 2020. “Applying an Intersectionality Lens to Expand Equity in the Geosciences.” Journal of Geoscience Education 68 (2): 97–114.

- Ouyang, D., D. Sing, S. Shah, J. Hu, C. Duvernoy, R. A. Harrington, and F. Rodriguez. 2018. “Sex Disparities in Authorship Order of Cardiology Scientific Publications: Trends over 40 Years.” Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 11 (12): e005040.

- Peters, C., and M. Broersma. 2019. “Fusion Cuisine: A Functional Approach to Interdisciplinary Cooking in Journalism Studies.” Journalism 20 (5): 660–669.

- Riffe, D., and A. Freitag. 1997. “A Content Analysis of Content Analyses.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 74 (3): 515–524.

- Rojas, H., and S. Valenzuela. 2019. “A Call to Contextualize Public Opinion-Based Research in Political Communication.” Political Communication 36 (4): 652–659.

- Schoon, A., H. M. Mabweazara, T. Bosch, and H. Dugmore. 2020. “Decolonising Digital Media Research Methods: Positioning African Digital Experiences as Epistemic Sites of Knowledge Production.” African Journalism Studies 41 (4): 1–15.

- Søraa, R. A., M. Anfinsen, C. Foulds, M. Korsnes, V. Lagesen, R. Robison, and M. Ryghaug. 2020. “Diversifying Diversity: Inclusive Engagement, Intersectionality, and Gender Identity in a European Social Sciences and Humanities Energy Research Project.” Energy Research & Social Science 62: 101380.

- Steensen, S., and O. Westlund. 2021. What Is Digital Journalism Studies? Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Steensen, S., A. M. Grøndahl Larsen, Y. B. Hågvar, and B. K. Fonn. 2019. “What Does Digital Journalism Studies Look like?” Digital Journalism 7 (3): 320–342.

- Tandoc, E., Jr, K. Hess, S. Eldridge, and O. Westlund. 2020. “Diversifying Diversity in Digital Journalism Studies: Reflexive Research, Reviewing and Publishing.” Digital Journalism 8 (3): 301–309.

- Trepte, S., and L. Loths. 2020. “National and Gender Diversity in Communication: A Content Analysis of Six Journals between 2006 and 2016.” Annals of the International Communication Association 44 (4): 289–311.

- Tully, M., D. Madrid-Morales, H. Wasserman, G. Gondwe, and K. Ireri. 2022. “Who is Responsible for Stopping the Spread of Misinformation? Examining Audience Perceptions of Responsibilities and Responses in Six Sub-Saharan African Countries.” Digital Journalism 10 (5): 679–697.

- Ullah, M. S. 2014. “De-Westernization of Media and Journalism Education in South Asia: In Search of a New Strategy.” China Media Research 10 (2): 15–23.

- Usher, N. 2019. “#JStudiesSoWhite: A Reckoning for the Future.” Keynote presentation at the seventh Future of Journalism conference, Cardiff, UK, September.

- Vásárhelyi, O., I. Zakhlebin, S. Milojević, and E. Á. Horvát. 2021. “Gender Inequities in the Online Dissemination of Scholars’ Work.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (39): e2102945118.

- Vermeer, S., D. Trilling, S. Kruikemeier, and C. de Vreese. 2020. “Online News User Journeys: The Role of Social Media, News Websites, and Topics.” Digital Journalism 8 (9): 1114–1141.

- Wang, X., J. D. Dworkin, D. Zhou, J. Stiso, E. B. Falk, D. S. Bassett, P. Zurn, and D. M. Lydon-Staley. 2021. “Gendered Citation Practices in the Field of Communication.” Annals of the International Communication Association 45 (2): 134–153.

- Watanabe, K. 2018. “Newsmap: A Semi-Supervised Approach to Geographical News Classification.” Digital Journalism 6 (3): 294–309.

- Willems, W. 2014. “Beyond Normative Dewesternization: Examining Media Culture from the Vantage Point of the Global South.” The Global South 8 (1): 7.

- Witschge, T., M. Deuze, and S. Willemsen. 2019. “Creativity in (Digital) Journalism Studies: Broadening Our Perspective on Journalism Practice.” Digital Journalism 7 (7): 972–979.

- Witteman, H. O., M. Hendricks, S. Straus, and C. Tannenbaum. 2019. “Are Gender Gaps Due to Evaluations of the Applicant or the Science? A Natural Experiment at a National Funding Agency.” Lancet (London, England) 393 (10171): 531–540.

- Woolley, A. W., C. F. Chabris, A. Pentland, N. Hashmi, and T. W. Malone. 2010. “Evidence for a Collective Intelligence Factor in the Performance of Human Groups.” Science 330 (6004): 686–688.

- Zeng, J., J. Burgess, and A. Bruns. 2019. “Is Citizen Journalism Better than Professional Journalism for Fact-Checking Rumours in China? How Weibo Users Verified Information following the 2015 Tianjin Blasts.” Global Media and China 4 (1): 13–35.