?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In line with internationally defined goals of sustainable development, European agricultural policies today have a far-sighted vision for rural areas. Using a case study approach, this paper explores how receptive rural farms in Sicily are to a long-term vision of development. The study focuses on three key factors of a long-term vision, that is, digitalisation, innovation and sustainability, to examine not only whether farms have invested in these areas but also how they perceive their role in the post-pandemic era. Empirical results provide insights into the concentration of farms in the central inland areas of Sicily without any real long-term vision of development. Nevertheless, the analysis also shows that some of them do have a positive attitude to change.

1. INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, rural areas are no longer considered just areas outside urban centres, but as places with important environmental, natural and cultural assets, where local actors play a strategic role in the preservation of biodiversity and soil, as well as cultural heritage (Aronica et al., Citation2021; Esposti, Citation2012). In line with this, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP)Footnote1 has recently evolved to support a holistic approach to agricultural productivity and rural development (the so-called first and second pillars). In particular, the European Commission (Citation2012, Citation2020a, Citation2021a, Citation2021b) has set out specific strategies and policies for a long-term vision of rural areas highlighting how some key factors such as digitalisation, innovation and sustainability are fundamental prerequisites for making local communities more resilient to potential exogenous shocks (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Citation2020a). In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the European Commission (Citation2020a), for example, has allocated extraordinary resources in the Next Generation EU Programme to promote rural development strategies based on the above-mentioned key factors.

However, the efficacy of policies and actions defined at a macro-spatial level could be reduced if they are not supported by changes in behaviour at the micro-firm level (Fazio & Piacentino, Citation2010). For instance, policymakers spending on technological infrastructures to reduce the urban–rural digital divide (OECD, Citation2018) would have little return on their investment if there were no corresponding spread of digital culture into the rural areas (Lythreatis et al., Citation2021). Referring to rural tourism, Randelli et al. (Citation2014) state that, ‘It is quite obvious that a new path, as RT [rural tourism] is, cannot start up if local farmers are not interested in moving forward’ (p. 277). The effectiveness of EU policies supporting the long-term development of rural areas is therefore also determined by whether local farms are prepared for change and are able to take advantage of the opportunities offered.

This study performs an empirical analysis on a case study of Sicilian farms, in the South of Italy, to explore whether or not farms have a long-term vision of rural development. Our survey on rural areas (here defined by a policy criterionFootnote2) explores the spatial areas where local action groups (LAGs)Footnote3 implement policies to achieve the goals set out in the regional rural development plan (RDP).

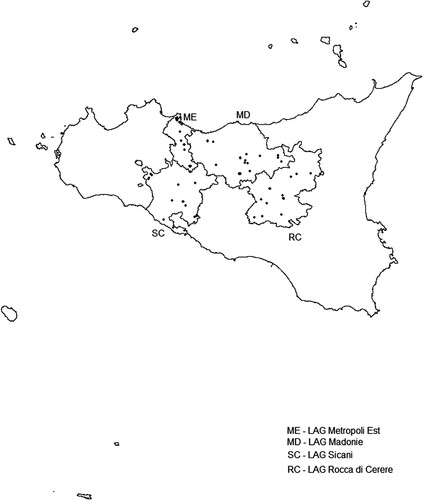

We have chosen four out of the 23 Sicilian LAGs (Metropoli Est; ISC Madonie; Rocca di Cerere Geopark; Sicani), covering a large swathe of north and central Sicily. This geographical area, in comparison with others in the same region, has a lower concentration of farms and industrial agglomerations (Aronica et al., Citation2021), as well as a lower endowment of digital and transport infrastructure. Investigating how receptive Sicilian farms are to a long-term vision and whether they are able to understand what changes need to be made could support regional and local policymakers to plan strategies for rural development.

Data were collected from a random sample of 149 farms on a set of items referring both to their general characteristics and three key factors of a long-term development vision, that is, digitalisation, innovation and sustainability. The latter enable us to define rural farmers’ Vision of development and their Attitude to Change. By combining Vision and Attitude to Change, we explore whether farms with a short-term Vision – namely, those that have so far not invested in digitalisation, innovation and sustainability – have a positive Attitude to Change.

To measure Attitude to Change, the survey explores how important digitalisation, innovation and sustainability are perceived to be in the post-pandemic era. This enables us to address the further question of how aware farms are of the changes induced by the pandemic crisis.

The COVID-19 pandemic presented rural farmers not only with the challenge of being resilient to the shock, but also of boosting business development by strategic investments in areas such as digitalisation, innovation and sustainability. This would trigger a virtuous circle in which the behaviour of rural farms would positively affect local sustainable development, and vice versa, generating a multiplier effect. This could be seen as the ‘last call’ for rural and inner areas, especially those in lagging regions, such as Sicily which is the subject of our case study. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt at an empirical analysis to assess the receptiveness of local farmers to European strategies of rural development and their awareness of the changes induced by the pandemic shock.Footnote4 Although the empirical results of our case study involve only a small sample of Sicilian farms, it may pave the way for future studies aimed at exploiting the receptiveness of entrepreneurs to the opportunities deriving from specific policies.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a synthesis of European policies in the field of agriculture and rural development and some evidence in the literature. Section 3 introduces the main aspects of the survey. Section 4 discusses the empirical results. Section 5 concludes. The supplemental data online includes the questionnaire.

2. EUROPEAN POLICY EVOLUTION: TOWARDS A LONG-TERM VISION FOR RURAL AREAS

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) in its first edition of 1962 had the following main goals: (1) increasing agricultural productivity; (2) supporting farmers’ incomes; and (3) stabilising markets and regulating prices.Footnote5 There is no mention of the impact of agricultural production in terms of environmental and social sustainability. Indeed, the policies of those days encouraged process innovation aiming at higher levels of agricultural productivity without any respect for the soil and other natural resources. The implementation of such policies generated overproduction and environmental damage with serious consequences for future generations.

Since the early 1990s, policymakers have recognised the need to reverse this trend and have introduced important reforms such as: (1) The MacSharry reform in 1992; (2) Agenda 2000; and (3) The Fischler reform in 2003. These reforms have led to an evolution of agriculture policies that have moved away from sectoral productivity to rural development. To implement these reforms, specific European funds, for example, the second pillar of CAP,Footnote6 have been exclusively reserved for rural development (Dwyer et al., Citation2007; Mack et al., Citation2021), and at the same time new mechanisms have been introduced conditioning agricultural subsidies to respect environmental standards, that is, the so-called conditionality (e.g., Bartolini & Viaggi, Citation2013; Moro & Sckokai, Citation2013). In this policy framework, the role of local actors is considered pivotal to the adoption of a sustainable approach to rural development (Daugbjerg, Citation2003; Frascarelli, Citation2017; Henke, Citation2002, Citation2004; Rizov, Citation2004).

More recently, to increase the competitiveness of rural economies, innovation and sustainability practices at farm level have further been supported by the Europe 2020 reform (European Commission, Citation2020b)Footnote7 and other European agricultural programmesFootnote8 (Frascarelli, Citation2017; Gregori & Sillani, Citation2012; Mantino, Citation2015; Pelucha & Kveton, Citation2017). These policies have not only reserved additional resources for rural development but also increased the flexibility of their use by member states (De Castro et al., Citation2021).

Finally, the European Green Deal (European Commission, Citation2019), the Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 (European Commission, Citation2021a), and the Farm to Fork strategies (European Commission, Citation2020c) have enriched the policy framework, stressing the role of rural economies in preserving the environment and biodiversity globally, as well as moderating the effects of climate change (Marandola & Vanni, Citation2019).

In 2021, following the direction indicated by these policies, the European Commission defined a long-term vision for the EU’s rural areas (European Commission, Citation2021b). This vision identifies four complementary actions to make rural areas: (1) stronger, empowering rural communities by increasing access to services, and facilitating innovation and digitalisation; (2) connected, by improving infrastructures; (3) more resilient to environmental, health and economic shocks; and (4) more prosperous, by encouraging the diversification of economic activities (for more details, see European Commission, Citation2021b).

To achieve this, factors such as digitalisation, innovation and sustainability play a key role. The digitalisation of local communities and farms, for example, should reduce the remoteness of rural areas (Salemink et al., Citation2017), making these more connected and stronger. Innovation affects the competitiveness of rural economies – increasing the quality of agricultural production and offering new business opportunities (Esposti, Citation2012) – and makes them stronger and more prosperous. Finally, investments in sustainability, for example, agroecological practices or other greening measures (Capitanio et al., Citation2016; Coderoni & Esposti, Citation2018; Cortignani & Dono, Citation2015; Garini et al., Citation2017), as well as the diversification of farming activities (Balezentis et al., Citation2020), are fundamental in making rural areas more resilient. However, there is still a long way to go before such a vision is realised due to the urban–rural cultural and digital divide to be found not only in Europe but also in the rest of the world (OECD, Citation2018).

For instance, in the case of Wales, Bowen and Morris (Citation2019) find that 19% of farmers have no access to broadband connection, with damaging consequences for their ability to innovate and grow, and also that many of them under-use the internet due to their limited digital literacy. This may be also attributed to the elderly population of rural areas and the small size of farms. Indeed, smaller farms with older and less educated farmers seem to be less likely to adopt digital technologies (Marescotti et al., Citation2021) and innovate (Arzeni et al., Citation2021; García-Cortijo et al., Citation2019; Läpple et al., Citation2015; McFadden & Gorman, Citation2016).

Overall, empirical research on developed countries highlights a persistent digital reticence on the part of rural farmers and the need to promote and incorporate the use of information technologies within an integrated approach for rural development (Grimes & Lyons, Citation1994). This integrated approach will mean supporting basic competence-building before introducing more advanced technologies, since even elementary digital skills may be new to farms (Norris, Citation2020). In this context, education and communication will play a crucial role in encouraging a positive attitude to digitalisation and innovation (Räisänen & Tuovinen, Citation2020). Similarly, a lower level of human capital in rural areas may threaten the adoption of sustainable practices and will call for skills, education and training to favour long-term development (OECD, Citation2020b).

Although the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically worsened an already vulnerable socio-economic condition (European Commission, Citation2021b; OECD, Citation2020a), today there is a great – maybe the greatest – opportunity for development. The pandemic has accelerated the digital transition in rural areas (Morris et al., Citation2022). Recovery packages, such as Next Generation EU, have been designed to bridge the urban–rural divide by funding investments in digital infrastructures, digital literacy, innovation and sustainable practices (Mikhaylova et al., Citation2021). However, as mentioned previously, changes at a macro-level will not happen if they are not supported by changes in behaviour at a micro-level. Hence, in short, a positive attitude to change on the part of local actors is a precondition to making effective investments. Using a case study approach, the empirical part of our study will explore this issue employing primary data on the specific case of Sicilian rural farmers.

3. A LOCAL SURVEY ON SICILIAN RURAL FARMS

3.1. Questionnaire and sampling procedures

Following a case study approach, our research issues have been addressed by collected data on a random sample of Sicilian farms located in rural areas where four LAGs operate.Footnote9 The questionnaire, administered with the support of LAGs, after the acceptance of a declaration of informed consent by the respondents,Footnote10 was processed ensuring the anonymity and in accordance with the usual provisions of the legislation on data privacy. The questionnaire is subdivided into four sections in order to investigate the following:

Farm characteristics such as ownership, management, market share, employees, etc.

Information and communication technologies (ICTs): to explore the readiness to use basic ICT tools such as websites and social media.Footnote11

Innovative activities such as product, process, marketing and organisational innovations.

Sustainable practices: to explore whether or not farms take into consideration social, economic and environmental sustainability.

The last three sections explore the attitude of farms to investment in digitalisation, innovation and sustainability (Vision); and also whether this has changed as a consequence of COVID-19 (Attitude to Change). Using a Likert scale of 1–10, we measure the opinion of farmers on the importance of these factors on their economic activities in the pre-pandemic era and how important they think these factors will be in the post-pandemic era.

Before defining the sampling design, the questionnaire was tested through a pilot analysis on 10 Sicilian farms from different LAGs in order to evaluate its comprehensibility and to receive potential feedback so as to improve the questions. The data were collected by means of direct interviews with the owner/administrator of the company using an online platform between 25 June and 10 July 2020. More than 70% of the interviewees declared they found the questionnaire to be clear, well-organised and relevant to the concerns of farmers and rural economies. This meant that only minor changes were needed to obtain the final version of the questionnaire (see the supplemental data online). The sample was randomly extracted at the end of 2020 from the population of Sicilian farms, that is, business units codified as A01 in the ATECO2007/NACE sectoral classification.Footnote12 Starting from a population of about 78,000 farms, we select the subpopulation of 13,762 farms in the areas where the LAGs under consideration operate (i.e., Metropoli Est, Sicani, ISC Madonie and Rocca di Cerere Geopark).

Finally, we extracted a sample of 388 farms by applying a proportional stratified random sampling technique with LAGs and the legal status of the farms as stratification variables. The sample size was obtained using Slovin’s formula.Footnote13 The selected farms were first contacted by email with the help of the LAGs. However, even at this early stage the problem of digital reticence emerged as some farmers did not even have an email address. Therefore, in some cases, interviews were conducted by telephone or in person. The survey was carried out from April to July 2021. The response rate was 38%. Hence, we collected data on 149 farms spatially distributed as follows: Metropoli Est (43), Sicani (36), ISC Madonie (33) and Rocca di Cerere Geopark (37).

shows the rural areas explored and the spatial distribution of the farms selected. This is a large portion of middle Sicily. The Metropoli Est (ME) LAG is the nearest to the metropolitan city of Palermo. Of the areas we studied, this has the easiest access to transport infrastructures and public services (airport, port, highways, broadband connections, etc.). Of course, even within this LAG, there are considerable differences between rural coastal and rural inner areas. The Sicani (SC) LAG area extends from the southern coast to the borders of the Metropoli Est LAG, crossing the Sicani mountains and the historic route of the Magna Via Francigena. The ISC Madonie (MD) LAG area covers a large portion of the northern coast of Sicily, with its famous tourist destinations such as the city of Cefalù, and extends inland through the Madonie mountains characterised by fascinating medieval villages. Finally, the Rocca di Cerere Geopark (RC) LAG includes exclusively inner rural areas and suffers most from the lack of transport infrastructures.

Even though the sample was obtained with statistically validated sampling procedures, the small number of observations obtained calls for the need to enlarge the targeted sample in future.

3.2. Variables and empirical strategy

lists the variables used in the analysis.Footnote14 We record a few missing values with observations that range across variables from 140 to 149. Among the list of variables Males highlights a significant gender gap, with 82% of respondents being men, in the Age variable the majority (62%) are under 50 years old, only 16% are under 30 and some 20% are over 60. Only 30% of farms operate outside their regional market (Outside Regional Market). More than half of farms (56%) are organised as family businesses (Family Business) and only 42% of farms have at least one certification among International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 22000, ISO 9001, International Food Standard (IFS), Brand Reputation through Compliance (BRC), global Good Agricultural Practice (GAP) and protected denomination of origin and Protected Geographical Indication (DOP-IGP) (Certifications).

Table 1. Variables.

Focusing on the variables that are of particular interest for this analysis, we find that only 40% of farms use websites or social media (ICTs), reflecting the digital reticence of rural areas. We separately asked farmers whether they have a website and if they use social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube). We then constructed a general variable, which we call ICTs, that assumes a value of 1 if the farm has adopted at least one of these digital tools, 0 otherwise. Those farms that had adopted them seemed, from a preliminary analysis, to be using only basic tools such as Facebook, which the literature suggests is not very useful for business purposes (e.g., Aronica et al., Citation2021b). A total of 43% of farms have introduced innovations over the last three years (Innovation). We divided this category into two: technological (product and process) innovations; and non-technological (organisational and marketing) ones. However, for our purpose, we aggregate this information in a variable called Innovation, which assumes a value of 1 when a farm has introduced at least one type of innovation, 0 otherwise. Farms seem to be slightly more oriented to innovation (43%) than to adopting ICTs (40%).

There is a greater willingness to adopt sustainable practices: 75% of farms adopted at least one Environmental Sustainability practice; 62% at least one Social Sustainability practice; falling to 56% in the Economic Sustainability category. We measure these dimensions of sustainability by a set of variables largely suggested by the literature (Arfini et al., Citation2019; Hosseininia & Ramezani, Citation2016). Environmental sustainability is initially measured by means of three binary variables that refer to the following practices: (1) using renewable energies; (2) using ecological products; and (3) preferring suppliers that adopt environmentally sustainable practices. We then aggregate this information to obtain a variable that assumes a value of 1 if the farm has adopted at least one of those practices, 0 otherwise (Environmental Sustainability). Similarly, we measure Social Sustainability by a variable that is 1 if the farm has adopted at least one of these practices: (1) providing health and safety training courses; (2) collaborating with charitable projects in the local community; and (3) disclosing sustainable aims in official documents or other channels. Economic Sustainability is measured by aggregating the following binary variables: (1) adopting environmentally sustainable practices to attract investors; and (2) adopting environmentally sustainable practices to improve economic performance. Finally, we construct a variable, called Sustainability, that is 1 if the farm has adopted at least one type of sustainable practice, irrespective of its dimensions.

It should be emphasised that our focus is not on specific aspects of ICTs, innovation and sustainability, but is rather from a holistic and multidimensional perspective, as we endeavour to understand whether an agricultural enterprise is adopting a long-term vision of development or remains short-sightedly short-term in its outlook. To this end, we construct a categorical variable called Vision and labelled as follows:

0 if ICTs, Innovation and Sustainability assume values = 0. We call this category ‘Short-Term Vision’.

1 if one of the above variables is = 1. We call this ‘Long-Term Vision – low intensity’.

2 if two of the above variables are = 1. We call this ‘Long-Term Vision – medium intensity’.

3 if all three variables are = 1. We call this ‘Long-Term Vision – high intensity’.

This categorical variable will enable us to address our first research issue, that is, whether farms are prone to a long-term vision for rural areas. Specifically, we will observe the association between the Vision and the main characteristics of a farm in order to find some regularities.

To address our second research issue, that is, how aware farms are of the changes induced by the pandemic crisis, we define another variable that aims to capture farmers’ Attitude to Change in response to the pandemic. To this end, we use information from the following questions:

BEFORE the Covid-19 pandemic, how important do you think the following were to your business:

adopting ICTs.

introducing innovations

using renewable energies.

other …

AFTER the Covid-19 pandemic, how important do you think the following will be to your business:

adopting ICTs.

introducing innovations.

using renewable energies.

other …

We measure each item by means of a Likert scale 1–10.Footnote15 We take the average score of the different sustainable practices to obtain the aggregate measures described above (Environmental Sustainability; Social Sustainability; Economic Sustainability). Therefore, we define a measure of Attitude to Change as follows:

(1)

(1) and classify farms as follows:

0 if Attitude to Change is negative. We call this category ‘Negative’.

1 if Attitude to Change is null. We call this ‘Neutral’.

2 if Attitude to Change is positive. We call this ‘Positive’.

In the next section, we will cross-reference the two variables Vision and Attitude to Change. Our findings could be particularly useful to policymakers at different levels of governance as they face the challenges of the upcoming period of recovery and resilience.Footnote16

4. EMPIRICAL RESULTS

4.1. Vision

Table A1 in the supplemental data online gives an overview of Vision and the main demographic and business characteristics of the rural farms involved in the analysed case study. We note that while Vision is not significantly associated with gender (Males), it is connected to all the other characteristics. Younger farmers (Age ≤ 50 years), farms that also operate outside their regional markets, farms organised as a family business and farms with at least one certification are less likely to have a Short-Term Vision. For example, while only 2% of farms that commercialised their products outside the regional market were classified as having a Short-Term Vision, 62% of them were termed as having a Long-Term Vision of high intensity. And only 4% of farms with quality certifications have a Short-Term Vision in comparison with 39% of them with a Long-Term Vision of high intensity.

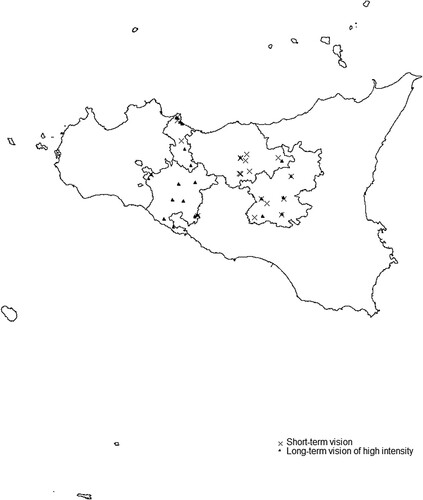

Table A2 in the supplemental data online shows the frequency distribution of Vision by LAG. Farms with a Short-Term Vision are particularly concentrated in the ISC Madonie and Rocca di Cerere Geopark LAGs (50% and 26%, respectively), which probably suffer more than most from inadequate transport infrastructure and poor essential services. Just to mention a few of them, the section of the Palermo–Catania highway that crosses these areas has serious structural problems that affect traffic flow, broadband connection is still a mirage, and hospital services have been drastically reduced over recent years. The Metropoli Est and Sicani LAGs, however, have the highest percentages of farms with a Long-Term Vision of high intensity (34% and 39%, respectively). Almost half of the farms interviewed (46%) in the Sicani LAG have a Long-Term Vision of high intensity. This evidence is even clearer from a visual inspection of . In our sample, on the one hand, there are 26 farms with a Short-Term Vision – marked by crosses on the map – that are almost exclusively located in the innermost zone of Sicily where the ISC Madonie and Rocca di Cerene Geopark LAGs operate. On the other hand, the 38 farms with a Long-Term Vision of high intensity – marked by black triangles on the map – seem to be less spatially concentrated, except for a cluster in the coastal area of the Metropoli Est LAG which is close to the metropolitan city of Palermo.

4.2. Attitude to Change

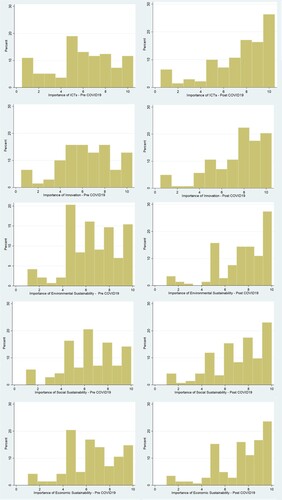

compares the answers of farms on the importance of ICTs, Innovation and the three dimensions of Sustainability before and after the pandemic. As a consequence of the pandemic, there has been an increased awareness of the role of digital tools, innovation and sustainability. Indeed, all histograms on the right-hand side show a greater concentration of respondents with the highest scores.

Tables A3–A7 in the supplemental data online focus on the distribution of Attitude to Change by LAG. As regards ICTs, we observe that 59% of farms have a Positive Attitude, 39% are Neutral and the remaining 1.48% are Negative (see Table A3 online). In general, farmers seem to be aware of the increasing importance of information and communication technologies in the post-COVID19 era. We do not find important differences across LAGs: the share of Positive ranges from 68% of Sicani to 45% of ISC Madonie.

Farmers seem less interested in the role of innovation post-COVID (see Table A4 in the supplemental data online). Only 44% have a Positive Attitude, while 52% are Neutral to change. There is a spatial heterogeneity across LAGs with a higher concentration of Positive in the Metropoli Est and Rocca di Cerere Geopark LAGs (the row percentages being 32% and 39%, respectively) and of Neutral in the other two LAGs (the row percentages being 32% in ISC Madonie and 30% in Sicani).

As far as sustainability is concerned, the farmers are more Neutral than Positive, independently of the type of sustainability (see Tables A5–A7 in the supplemental data online). The percentages of Positive are 46%, 31% and 44% for environmental, social and economic sustainability, respectively. However, looking at each LAG we observe some differences, especially between the ISC Madonia and the Rocca di Cerere Geopark. Although the two LAGs are similar enough in terms of Vision, there are significant differences in terms of Attitude to Change. Indeed, the ISC Madonie has the lowest concentration of Positive of all the LAGs (16%, 13% and 20% for environmental, social and economic sustainability, respectively), while the Rocca di Cerere Geopark has the highest (62%, 39% and 61%, respectively). Overall, rural farmers seem to be more concerned about environmental and economic sustainability than social sustainability. However, this evidence has to be carefully interpreted as it emerges from a case study involving mainly small size farms. Indeed, smaller farms might have less motivation to invest in social sustainability, especially charitable projects in comparison to larger farms with more economic resources and a greater reputation to maintain.

4.3. Vision versus Attitude to Change

Looking at the association between Vision and Attitude to Change, as concerns ICTs, Table A8 in the supplemental data online shows that about 46% of farms with a Short-Term Vision have a Positive Attitude. This evidence is encouraging since it means that a large percentage of rural farms which do not have a Long-Term Vision, still recognise the increasing role played by digital technologies. As expected, the share of farms with Positive Attitude increases significantly in the case of Long-Term Visions (55%, 72% and 68% for low, medium and high, respectively).

The results are less exciting for innovation. Table A9 in the supplemental data online shows that only 38% of farms with a Short-Term Vision have a Positive Attitude. We need to reach a Long-Term Vision of high intensity before we find 50% of farms with Positive Attitude. Looking at the full sample, we find that most farms are Neutral to change (52%) in terms of innovation. Tables A10–A12 in the supplemental data online show that 40% of farms with a Short-Term Vision have a Positive Attitude in the case of environmental and economic sustainability, while only 24% do so when we consider social sustainability. Only farms with a Long-Term Vision of high intensity exceed 50% of Positive Attitude, reaching 60% in the case of environmental and economic sustainability.

Overall, even those farms with a Short-Term Vision are aware of the role that information and communication technologies may play in the post-pandemic era. However, it is mostly those with a Long-Term Vision of high intensity who have a Positive Attitude to Change when it comes to innovation and sustainability. Finally, even those farms with Long-Term Visions seem to have only a limited interest in social sustainability.

4.4. A regression analysis

To examine the previous empirical evidence in greater depth, a regression analysis has been performed. First, we estimate an ordered probit model to explore the effects of farm characteristics and location on the probability of being in the upper levels of Vision (). In this model, the Short-Term Vision represents the reference category. The estimations show that those in the younger (Age) group are much more likely to be found in an upper level of Vision as are farms that operate Outside Regional Market and have at least one Certification. We also found that farms located in the ISC Madonie LAG have lower probabilities of being in the upper levels of Vision. From estimates, we have computed marginal effects to interpret the magnitude of impacts (columns 2–5 in ). We found that younger farmers are 13.6% less likely to have a Short-Term Vision and 15.5% more likely to have a Long-Term Vision of high intensity. Farms operating outside the regional market are 16% less likely to have a Short-Term Vision, and 29.4% more likely to have a Long-Term Vision of high intensity. Finally, farms with at least one certification are 8.6% less likely to have a Short-Term Vision, and 11.1% more likely to have a Long-Term Vision of high intensity.

Table 2. Farms: vision – ordered probit model.

In , we estimate a set of probit models to look at the probability of having a Positive Attitude to Change for each of the factors used to define Vision.Footnote17 Our results show that having a Long-Term Vision of medium and high intensity impacts only on the Positive Attitude of Change in the case of ICTs and Social Sustainability. In all the other cases, there are no significant differences. What the evidence indicates is that there is a large percentage of farms with a Short-Term Vision which still have a Positive Attitude. Therefore, the regression analysis reveals that even some of the ‘less virtuous’ farms have not yet abandoned the idea of change, and recognise the increasing role of digitalisation, innovation, and sustainability in their businesses, especially in the post-pandemic era. This evidence should be carefully read by policymakers so as to identify the most fertile ground in which to plant the seeds of recovery.

Table 3. Attitude to change – probit models.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The social and economic changes of recent decades have made rural areas very vulnerable due to depopulation and ageing of the population, and lack of infrastructures and services. To combat this, the latest European policy is based on strategies with a long-term vision of rural development in the areas of digitalisation, innovation and sustainability. Moreover, in response to challenges related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the European Commission has also allocated extraordinary resources to support investment in these areas.

These initiatives provide opportunities to promote the green and digital transition in these places which will, in turn, ease the diversification of economic activities, preserve biodiversity and rural landscape, and attract younger people, avoiding land abandonment (European Commission, Citation2021b). However, for these policies to be effective they should be supported by changes in behaviour at a micro-firm level, that is, rural farmers should be aware of the opportunities and recognise the social and economic implications.

Even though these issues are highly important, empirical research is still limited and existing studies have mostly focused on individual aspects of the problem, such as digital and innovative backwardness or the lack of sustainable development. In contrast, using a case study approach on Sicilian farms, we adopt a holistic perspective considering all three issues (i.e., digitalisation, innovation and sustainability) in a single framework of analysis. To this end, we devised a questionnaire and conducted a survey on Sicilian farms located in the rural areas where the Metropoli Est, Sicani, ISC Madonie, and Rocca di Cerere Geopark LAGs operate.

Empirical results highlight the digital reticence of rural farms, especially in the more inland areas, farther away from the metropolitan city of Palermo. Overall, rural farms seem to have oriented their strategies more towards environmental and economic sustainability than towards digitalisation and innovation. We find that farmers under 50 are more likely to have a Long-Term Vision as are farms with at least one certification and those which also operate outside the regional market. Farms which are family businesses also seem to be more likely to have a Long-Term Vision, although this is not confirmed by regression analysis. We find that farms with a Long-Term Vision are more likely to have a Positive Attitude to Change only in the case of information and communication technologies and social sustainability. In the other cases, we find that there are a number of farms with a Short-Term Vision but with a Positive Attitude to Change.

In conclusion, the empirical results may provide policymakers interesting insights into the farmers’ attitude to long-term development. We observe that rural companies generally lack a long-term vision, meaning that they are not able to invest in digitalisation, innovation and sustainability simultaneously, even though they recognise their importance. This is probably due to a lack of economic resources as well as digital literacy. This suggests that rural farmers are aware of the opportunities offered by recent European policies and if adequately supported, both in terms of additional economic resources and digital culture, they could bridge the rural–urban divide.

Although our empirical results emerge from a case study based on a small random sample, we have been able to highlight, some important features of farmers behaviour and their long-term vision of rural development using innovative activities, digital tools and sustainable practices even in the face of the challenges of COVID-19. Our questionnaire explored the key factors of rural development in a holistic way and we believe its use could be extended to other regions and repeated over a longer period to make findings more generalisable. This could help policymakers to identify local areas and ‘less virtuous’ farms which would benefit from their support in building a long-term vision of rural development.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (192.6 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For details, see https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/key-policies/common-agricultural-policy/cap-glance_en

2 Empirical analyses usually adopt an administrative criterion to define the spatial units of investigation (e.g., regions).

3 European policies have favoured a more direct participation of local actors in rural development strategies adopting a bottom-up approach, called community-led local development (CLLD). In this approach a key role is played by LAGs, public–private partnerships with an understanding of the needs of rural communities financed by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) to implement local policy actions. See https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/leader-clld_en (accessed on 21 October 2021).

4 There is only one study that looks at the attitude of farms in response to rural development policy challenges, but its approach is mainly psychological (Stojcheska et al., Citation2016).

5 For more details, see https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/key-policies/common-agricultural-policy/cap-glance_en (accessed on 19 October 2021).

6 For more details, see https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/find-funding/eu-funding-programmes/european-agricultural-guarantee-fund-eagf_en; and https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/find-funding/eu-funding-programmes/european-agricultural-fund-rural-development-eafrd_en (accessed on 21 October 2021).

7 Europe 2020 is the EU’s 10-year strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. In order to deliver on this objective, five ambitious targets have been set, covering employment, research and development, climate change and energy sustainability, education, and the fight against poverty and social exclusion. See ‘Glossary –Regional Policy –European Commission’ (europa.eu) (accessed on 21 October 2021).

8 See https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/key-policies/common-agricultural-policy/new-cap-2023-27/key-policy-objectives-new-cap_en#nineobjectives (accessed on 21 October 2021).

9 Territorial systems that include cohesive aggregations of municipalities defined by the 2014–2020 Sicily Rural Development Program (RDP) and the Operational Program (PO) European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) Sicily 2014–2020. There are 22 LAGs in Sicily; in our study we consider the Metropoli Est, Sicani, ISC Madonie and Rocca di Cerere Geopark LAGs. It should be mentioned that LAGs only have the authority to implement policy actions in rural and marginal areas, that is, those areas classified as C and D in the Sicilian RDP, whereas areas classified A and B include urban and high-intensity agricultural areas.

10 For the full declaration of informed consent, see the supplemental data online.

11 As the farms involved in the case study were small and operating mainly in marginal rural areas where broadband connection has not yet become widespread, we refer to the use of basic ICTs and digital tools and do not consider advanced digital technologies, such as the Internet of Things, 3D modelling, etc.

12 We thank the Palermo Chamber of Commerce for allowing us to use these data.

13 Slovin’s formula n = N(1 + Ne2) is used to calculate the optimal sample size (n) from a population (N), deciding a certain level of error tolerance (e). In this case, N = 15,000 and e = 0.05 (Altares et al., Citation2003; Guilford & Frucher, Citation1973).

14 For the full list of questions included in the questionnaire, see the supplemental data online.

15 To test the consistency of responses related to multiple-items measurements of attitudes, Cronbach’s Alpha was used. It assumes acceptable values ranging from 0.86 to 0.90.

16 For details on European and Italian Recovery and Resilience Plans, see https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/recovery-plan-europe_en#nextgenerationeu; and https://www.mef.gov.it/focus/Il-Piano-Nazionale-di-Ripresa-e-Resilienza-PNRR/

17 To avoid potential multicollinearity with Vision, we do not add other covariates into the specification.

REFERENCES

- Altares, P. S., Copo, A. R. I., Gabuyo, Y. A., Laddaran, A. T., Mejia, L. D. P., Policarpio, I. A., Sy, E. A. G., Tizon, H. D., & Yao, A. M. S. D. (2003). Elementary statistics: A modern approach. Rex Bookstore Inc.

- Arfini, F., Antonioli, F., Cozzi, E., Donati, M., Guareschi, M., Mancini, M. C., & Veneziani, M. (2019). Sustainability, innovation and rural development: The case of Parmigiano–Reggiano PDO. Sustainability, 11(18), 4978. doi:10.3390/su11184978

- Aronica, M., Bonfanti, R. C., & Piacentino, D. (2021). Social media adoption in Italian firms. Opportunities and challenges for lagging regions. Papers in Regional Science, 100(4), 959–978. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12606

- Aronica, M., Cracolici, M. F., Insolda, D., Piacentino, D., & Tosi, S. (2021). The diversification of Sicilian farms: A way to sustainable rural development. Sustainability, 13(11), 6073. doi:10.3390/su13116073

- Arzeni, A., Ascione, E., Borsotto, P., Carta, V., Castellotti, T., & Vagnozzi, A. (2021). Analysis of farms characteristics related to innovation needs: A proposal for supporting the public decision-making process. Land Use Policy, 100, 104892. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104892

- Balezentis, T., Ribasauskiene, E., Morkunas, M., Volkov, A., Streimikiene, D., & Toma, P. (2020). Young farmers’ support under the common agricultural policy and sustainability of rural regions: Evidence from Lithuania. Land Use Policy, 94, 104542. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104542

- Bartolini, F., & Viaggi, D. (2013). The common agricultural policy and the determinants of changes in EU farm size. Land Use Policy, 31, 126–135. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.10.007

- Bowen, R., & Morris, W. (2019). The digital divide: Implications for agribusiness and entrepreneurship. Lessons from Wales. Journal of Rural Studies, 72, 75–84. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.10.031

- Capitanio, F., Gatto, E., & Millemaci, E. (2016). CAP payments and spatial diversity in cereal crops: An analysis of Italian farms. Land Use Policy, 54, 574–582. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.03.019

- Coderoni, S., & Esposti, R. (2018). CAP payments and agricultural GHG emissions in Italy. A farm-level assessment. Science of the Total Environment, 627, 427–437. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.197

- Cortignani, R., & Dono, G. (2015). Simulation of the impact of greening measures in an agricultural area of the southern Italy. Land Use Policy, 48, 525–533. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.06.028

- Daugbjerg, C. (2003). Policy feedback and paradigm shift in EU agricultural policy: The effects of the MacSharry reform on future reform. Journal of European Public Policy, 10(3), 421–437. doi:10.1080/1350176032000085388

- De Castro, P., Miglietta, P. P., & Vecchio, Y. (2021). The common agricultural policy 2021–2027: A new history for European agriculture. Italian Review of Agricultural Economics, 75(3), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.13128/rea-12703

- Dwyer, J., Ward, N., Lowe, P., & Baldock, D. (2007). European rural development under the common agricultural policy’s ‘second pillar’: Institutional conservatism and innovation. Regional Studies, 41(7), 873–888. doi:10.1080/00343400601142795

- Esposti, R. (2012). Knowledge, technology and innovations for a bio-based economy: Lessons from the past, challenges for the future. Bio-based and Applied Economics, 1(3), 235–268. https://doi.org/10.13128/BAE-11145

- European Commission. (2012). Communication from the commission to the European parliament and the council on the European Innovation Partnership ‘Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability’ Brussels, 29.2.2012 COM (2012).

- European Commission. (2019). The European Green Deal, Brussels, 11.12.2019 COM (2019), 640 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:b828d165-1c22-11ea-8c1f-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF

- European Commission. (2020a). Recovery plan for Europe.

- European Commission. (2020b). Communication from the commission EUROPE 2020 A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. Brussels, 3.3.2010 COM (2010).

- European Commission. (2020c). Farm to Fork Strategy for a fair, healthy and environmentally friendly food system. https://ec.europa.eu/food/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en#related.

- European Commission. (2021a). EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 bringing nature back into our lives. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/strategy/biodiversity-strategy-2030_en.

- European Commission. (2021b). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘A long-term Vision for the EU’s Rural Areas – Towards stronger, connected, resilient and prosperous rural areas by 2040’ Brussels, 30.6.2021 COM (2021).

- Fazio, G., & Piacentino, D. (2010). A spatial multilevel analysis of Italian SMEs’ productivity. Spatial Economic Analysis, 5(3), 299–316. doi:10.1080/17421772.2010.493953

- Frascarelli, A. (2017). L’evoluzione della Pac e le imprese agricole: Sessant’anni di adattamento. Online publication. Agriregioneuropa, 13. https://agriregionieuropa.univpm.it/it/content/article/31/50/levoluzione-della-pac-e-le-imprese-agricole-sessantanni-di-adattamento

- García-Cortijo, M. C., Castillo-Valero, J. S., & Carrasco, I. (2019). Innovation in rural Spain. What drives innovation in the rural–peripheral areas of Southern Europe? Journal of Rural Studies, 71, 114–124. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.02.027

- Garini, C. S., Vanwindekens, F., Scholberg, J. M. S., Wezel, A., & Groot, J. C. (2017). Drivers of adoption of agroecological practices for winegrowers and influence from policies in the province of Trento, Italy. Land Use Policy, 68, 200–211. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.07.048

- Gregori, M., & Sillani, S. (2012). Cinquant’anni di PAC: riflessioni in un’ottica di lungo periodo | Agriregionieuropa (univpm.it). Agriregioneuropa, 8(28), 63. https://agriregionieuropa.univpm.it/it/content/article/31/28/cinquantanni-di-pac-riflessioni-unottica-di-lungo-periodo

- Grimes, S., & Lyons, G. (1994). Information technology and rural development: Unique opportunity or potential threat? Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 6(3), 219–237. doi:10.1080/08985629400000013

- Guilford, J. P., & Frucher, B. (1973). Fundamental statistics in psychology and education. McGraw-Hill.

- Henke, R. (2002). Dalla Riforma MacSharry ad Agenda 2000: Il processo di greening della Pac. La Questione Agraria, n.1.

- Henke, R. (2004). Il riorientamento delle politiche di sostegno all’agricoltura dell’UE. Politica Agraria Internazionale, n. 1–2.

- Hosseininia, G., & Ramezani, A. (2016). Factors influencing sustainable entrepreneurship in small and medium-sized enterprises in Iran: A case study of food industry. Sustainability, 8(10), 1010. doi:10.3390/su8101010

- Läpple, D., Renwick, A., & Thorne, F. (2015). Measuring and understanding the drivers of agricultural innovation: Evidence from Ireland. Food Policy, 51, 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.11.003

- Lythreatis, S., Singh, S. K., & El-Kassar, A. N. (2021). The digital divide: A review and future research agenda. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, p. 121359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121359.

- Mack, G., Fintineru, G., & Kohler, A. (2021). Effects of EU rural development funds on newly established enterprises in Romania's rural areas. European Planning Studies, 29(2), 291–311. doi:10.1080/09654313.2020.1746243

- Mantino, F. (2015). La riforma della PAC e dei Fondi Strutturali 2014–2020: quale impatto sulla governance. Agriregioneuropa, 41. https://agriregionieuropa.univpm.it/it/content/article/31/41/la-riforma-della-pac-e-dei-fondi-strutturali-2014-2020-quale-impatto-sulla

- Marandola, D., & Vanni, F. (2019). Le sfide della nuova architettura verde della Pac post 2020. Agriregioneuropa, 56. https://agriregionieuropa.univpm.it/it/content/article/31/56/le-sfide-della-nuova-architettura-verde-della-pac-post-2020

- Marescotti, M. E., Demartini, E., Filippini, R., & Gaviglio, A. (2021). Smart farming in mountain areas: Investigating livestock farmers’ technophobia and technophilia and their perception of innovation. Journal of Rural Studies, 86, 463–472. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.07.015

- McFadden, T., & Gorman, M. (2016). Exploring the concept of farm household innovation capacity in relation to farm diversification in policy context. Journal of Rural Studies, 46, 60–70. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.05.006

- Mikhaylova, A. A., Mikhaylov, A. S., & Hvaley, D. V. (2021). Receptiveness to innovation during the COVID-19 pandemic: Asymmetries in the adoption of digital routines. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 8(1), 311–327. doi:10.1080/21681376.2021.1962400

- Moro, D., & Sckokai, P. (2013). The impact of decoupled payments on farm choices: Conceptual and methodological challenges. Food Policy, 41, 28–38. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.04.001

- Morris, J., Morris, W., & Bowen, R. (2022). Implications of the digital divide on rural SME resilience. Journal of Rural Studies, 89, 369–377. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.01.005

- Norris, L. (2020). The spatial implications of rural business digitalization: Case studies from Wales. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 7(1), 499–510. doi:10.1080/21681376.2020.1841674

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2018). Bridging the rural digital divide, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 265. OECD Publ. https://doi.org/10.1787/852bd3b9-en

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020a). Policy implications of coronavirus crisis for rural development. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=134_134479-8kq0i6epcq&title=Policy-Implications-of-Coronavirus-Crisis-for-Rural-Development.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020b). Managing environmental and energy transitions for regions and cities. OECD Publ. https://doi.org/10.1787/f0c6621f-en

- Pelucha, M., & Kveton, V. (2017). The role of EU rural development policy in the neo-productivist agricultural paradigm. Regional Studies, 51(12), 1860–1870. doi:10.1080/00343404.2017.1282608

- Räisänen, J., & Tuovinen, T. (2020). Digital innovations in rural micro-enterprises. Journal of Rural Studies, 73, 56–67. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.09.010

- Randelli, F., Romei, P., & Tortora, M. (2014). An evolutionary approach to the study of rural tourism: The case of Tuscany. Land Use Policy, 38, 276–281. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.11.009

- Rizov, M. (2004). Rural development and welfare implications of CAP reforms. Journal of Policy Modeling, 26(2), 209–222. doi:10.1016/j.jpolmod.2004.03.003

- Salemink, K., Strijker, D., & Bosworth, G. (2017). Rural development in the digital age: A systematic literature review on unequal ICT availability, adoption, and use in rural areas. Journal of Rural Studies, 54, 360–371. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.09.001

- Stojcheska, A. M., Kotevska, A., Bogdanov, N., & Nikolić, A. (2016). How do farmers respond to rural development policy challenges? Evidence from Macedonia, Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Land Use Policy, 59, 71–83. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.08.019