Abstract

This paper looks at the impact of the traditional and emerging institutional environment on the practice of migratory pastoralism in the Kailash Sacred Landscape (KSL), a transborder region in the western Himalayas around the tri-juncture between China, India, and Nepal, where migratory pastoralists have been an important part of the traditional political economy. It develops a conceptual perspective of migratory pastoralism and its associated social–ecological base using concepts drawn from common pool resource theories. The customary patterns of migratory pastoralism are described, as are the intra and extra-regional factors that have led to its decline. Understanding the transformation in recent decades of the variables linked to the social–ecological systems of the KSL, such as the sociocultural attributes of the landscape’s communities, the rules of resource management, and the biophysical attributes of the natural resource base, is key to understanding the decline of migratory pastoralism in the landscape. Recent geopolitics, national development trajectories, changing natural resource governance schemes, community adaptation strategies, and changing cultural perceptions all come together to shape the present day vulnerability of migratory pastoralism in this landscape.

Introduction

For communities residing at the peripheries of modern nation-states, the strategies and boundaries of natural resource use have historically often extended beyond the modern borders (Van Spengen Citation2000). Pastoralism is a mode of natural resource use that depends on mobility across space and periodical time, making optimum use of the resources in landscapes with harsh geo-climatic conditions and limited biomass. In the Himalayan region, customary institutions have provided the framework for sustainable use of rangeland resources by pastoralist communities for countless generations (Miller Citation1998; Banjade and Paudel Citation2008; Negi Citation2010). Institutions – defined as regularized patterns of behaviour between individuals and groups in society (Leach, Mearns, and Scoones Citation1999) or between segments of society (Ayers Citation1962) – are one of the crucial keys to sound natural resource management (Ghate Citation2004; Dong et al. Citation2008). There is much evidence that pastoralism is best managed communally (Herrera, Davies, and Baena Citation2014) and that forage resources in the Himalayas were historically governed by local communities as common property resources (CPRs) under customary frameworks (Oli et al. Citation2013). All along the Himalayas, many groups were previously involved in a complex cross-border network of social, cultural, and economic relations with residents of the Tibetan Plateau that led to the evolution of mutually dependent agriculturalist–trader–pastoralist economies (Van Spengen Citation2000; Bauer Citation2004). Migratory pastoralism was thus intricately intermeshed with other livelihood activities like trade and agriculture and was sustained by mobility and enabling customary systems along the migratory routes and rangelands, both within and beyond modern national boundaries.

However, several studies have observed a marked decline in the traditional practices and migration patterns of pastoralism, as well as its socio-economic viability, in the Himalayas in recent years (e.g. Wu and Richard, Citation1999; Goodall Citation2004; Negi Citation2007; Namgay et al. Citation2014; Sharma et al. Citation2014; Wu et al. Citation2014). While these studies have tried to capture various socio-economic and environmental factors undergirding this decline, there has been relatively little research on understanding how changes in institutions at multiple levels have overarching implications both directly on migratory pastoralism, as well as on these other factors effecting its decline in the Himalayas. Some studies that attempt addressing the role of institutions vis-à-vis migratory pastoralism in this regard include Goldstein and Beall (Citation1990), Agrawal and Ostrom (Citation2001), Gerwin and Bergmann (Citation2012), and Dong, Shaoliang, and Yan (Citation2016). The case study presented here intends to add to this literature by providing an analysis of the various factors that have contributed to the present day vulnerability of migratory pastoralism among three borderland communities at the Himalaya–Tibetan plateau interface – namely the Shaukas, the Humli Bhotiyas, and the Drokpas – from an institutional perspective. It looks at the impact of the emerging institutional environment, especially over the second half of the twentieth century, on the practice of migratory pastoralism among the aforementioned communities in the rangelands of the Kailash Sacred Landscape (KSL), a transborder region spread around the western tri-juncture between China, India, and Nepal. The study uses CPR concepts and variables linked to KSL’s socio-ecological systems to analyse the overall decline in the scale and socio-economic viability of migratory pastoralism in the KSL.

The conceptual perspective

Institutions can be understood as frameworks for socially constructed rules and norms which provide structure to everyday life, reduce uncertainty, and make certain forms of behaviour routine, thereby limiting choice (North Citation1990). By setting limits to social practice, including thought, institutions shape human experience and personal identity (Connell Citation1987). Institutions form the normative core of social–ecological systems (SESs), in which all resources used by humans are embedded. In a complex SES, subsystems such as a resource system (e.g. a rangeland), resource units (specific parcels of grazing areas), users (herders), and governance systems (organizations and rules that govern grazing on that rangeland) are relatively separable but interact to produce outcomes at the SES level. These outcomes in turn feed back into the SES to affect these subsystems and their components, as well other larger or smaller SESs (Ostrom Citation2009).

Around the world, resource units in SESs have been managed as common pool resources (CPRs) (Ostrom Citation2010). CPRs share the attribute of subtractability with private goods and the difficulty of exclusion with public goods (Ostrom Citation1990). There are four kinds of property rights in CPRs – withdrawal, management, exclusion, and alienation – but they are not necessarily available to all users. Owners have all four kinds of rights; proprietors have all rights except alienation; authorized claimants have rights of withdrawal and management; and authorized users only have the right to withdraw resources (Agrawal and Ostrom Citation2001).

Seen from a distance, a CPR can be understood as an ‘action arena’ whose structure is shaped by certain variables exogenous to the CPR such as the biophysical and material conditions of the SES it is embedded in, the attributes of the community that interacts with the CPR, and the set of rules that govern actions in the CPR (Ostrom, Gardner, and Walker Citation1994). It is vital to identify and understand these variables and the transformations among them in order to understand the dynamics governing a CPR. Furthermore, CPRs are usually not isolated or stand-alone entities in terms of the jurisdiction that governs them. Rather, they are enmeshed in webs of polycentric governance involving various, and usually interlinked, levels of decision-making, both vertically (hierarchically) and horizontally (at the same level), that shape their management (McGinnis Citation2011). Polycentric governance structures directly influence exogenous variables such as the rules of resource use and the attributes of the community, and indirectly even the biophysical attributes of the SES, for example through the delineation of administrative boundaries.

Decentralization of authority from central state structures to regional and local level institutions has become a favoured governance strategy in developing countries due to factors ranging from lower transaction costs to better availability of information at the local level (Bardhan Citation2002). Typically, successful decentralization of resource management results in the creation of new commons as central governments delegate rights and powers to new actors who can make decisions about the disposition of these resources. As governments formulate new rules, they allow lower level actors greater leeway in deciding the fate of locally situated resources, though now subject to supervision and checks by state agencies. In contrast, in a highly centralized regime, almost all authority for making rules is concentrated in a national government. Local officials and citizens are viewed as rule followers, not as rule makers (Agrawal and Ostrom Citation2001, 487–490).

However, the ability to benefit from resources is mediated not just by ‘bundles of rights’, as enlisted above, but also by the possibilities and constraints established by the specific political-economic and cultural frames within which access to resources is sought. Therefore, by focusing on access – defined as the ability to benefit from things including material objects, persons, institutions, and symbols – a wider range of social relationships that can constrain or enable people to benefit from resources is brought into attention, including but not limited to property relations alone (Ribot and Peluso Citation2003). Herder communities need to be seen as enmeshed in contested webs of relations alongside other local and trans-local communities, amidst which some people have access ‘at different levels, or with a wider geographical span, [while] others do not’ (Van Schendel Citation2005: 10). Besides, rather than ensuing from rigid categories such as ‘tradition’ or ‘the state’, many institutional arrangements are forged in practice through daily interactions, the necessary improvisation involved in daily life, and the constant use of resources (Cleaver Citation2002). This study intends to understand the access to rangeland resources among three Himalayan borderland communities traditionally practicing migratory pastoralism in a transborder region, by looking at this ‘institutional bricolage’ (ibid) resulting from the essentially complex, diverse, and ad-hoc nature of institutional formation.

Methodology

KSL – the study site

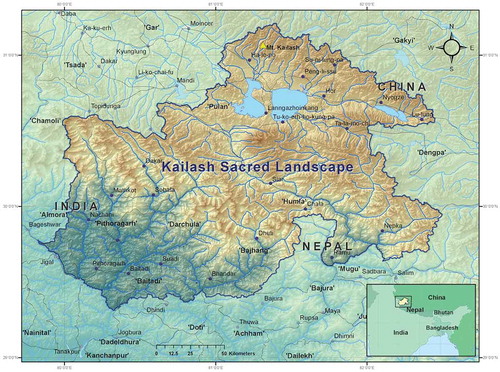

In 2010, national scientific institutions from China, India, and Nepal delineated the KSL, an area around the holy mountain of Kailash with shared ecological, historical, cultural, and climatic linkages () (Oli and Zomer Citation2011). Administratively, KSL covers the Pulan County of the Tibetan autonomous region (TAR), China (henceforth, referred to as KSL China); district Pithoragarh of Uttarakhand state, India (KSL India), and districts Baitadi, Darchula, Bajhang, and Humla of Nepal (KSL Nepal). Rangelands comprise 27% of the total area of KSL, and 50% when considered together with their interfaces with adjacent ecosystems. The rangelands provide essential watershed functions and support globally significant species of flora and fauna, including many medicinal plants. The flora also provides fodder and other biomass resources for various kinds of migratory pastoralism – traditionally one of the most important livelihood strategies in the landscape (Rawat et al. Citation2013). The major biophysical attributes of the KSL are summarized in .

Table 1. Biophysical attributes of the Kailash Sacred Landscape.

Historical background

Prior to mid-twentieth century, the geo-political and institutional conditions in KSL China and KSL Nepal allowed for rangelands and migratory pastoralism to be governed primarily by local level arrangements, which were nested within broader networks of governance. These local level arrangements included customary reciprocal ties with neighbouring communities and their rangelands across the national borders. In KSL India, the nature of access to rangelands and the volume of migratory pastoralism had already begun to be significantly shaped by the policies of the colonial government starting in the first half of the nineteenth century (Bergmann et al. Citation2012). The tax reductions on trans-Himalayan trade for Shaukas and industrialized wool production in the Gangetic plains favoured a substantial increase in the volume of the Shauka-dominated Indo-Tibetan trade and their investment in livestock over much of the nineteenth century (Atkinson, Citation1884[1996]). However, developments from the late nineteenth century onward till Indian Independence in 1947, such as restrictive colonial forestry policies (e.g. setting up of Reserved Forests [RFs]), the gradual replacement of Tibetan wool by imports from Europe and Australia, and of Tibetan salt by cheaper substitutes from coastal India, began to slowly dry up both Indo-Tibetan trade and seasonal transhumance (Guha Citation1989; Roy Citation2003).

Nonetheless, the Shaukas continued to practice a substantial volume of seasonal transhumance as well as Indo-Tibetan trade till the Indo-China war of 1962. Certain practices, such as the ‘Serji system’ – wherein messengers of Tibetan officials entered the Shauka-inhabited valleys of KSL India to initiate the trade season and negotiate a disease-free inflow of Shauka traders and livestock – were outlawed by the colonial government by the end of the nineteenth century, being cited as infringements to British Indian sovereignty (Brown Citation1984). But other customary arrangements, such as the ‘mitra’ ties ensuring exclusive trade ties between Shauka and Drokpa trader families, the practice of seasonal transhumance by the Shaukas, and their social, economic, and cultural ties with the Shaukas residing in KSL Nepal continued throughout and beyond the colonial period (ibid). The customary reciprocal ties of pastoralism between the Humli Bhotiyas of KSL Nepal and the Drokpas also continued till around the time when the border between China and Nepal got formalized in the 1960s (Goldstein Citation1975; Bauer Citation2004). This study thus understands ‘traditional’ systems of migratory pastoralism as those which were in place in the Himalayan and Tibetan borderlands of the KSL before the Chinese annexation of Tibet in the 1950s. This event had a drastic impact on migratory pastoralism in among all the three communities studied.

Data collection

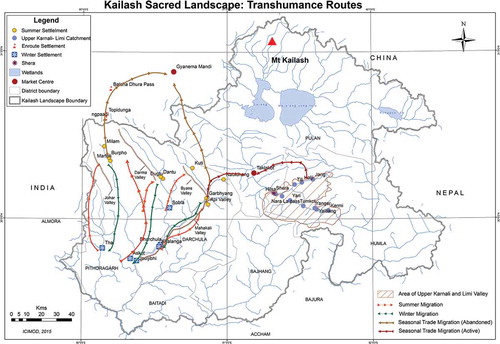

The findings in this paper draw primarily upon secondary data and a limited amount of primary data collected during field studies in KSL India and KSL Nepal in 2014 and 2015. The field study sites were selected in areas with a recent history of traditional transborder pastoral migration; three sites in the Mahakali river system – one amidst Chaudans, Api, and Nampa valleys each – along the border between India and Nepal; and one each in the upper reaches of the Karnali and Limi valleys (). Fifteen key informant interviews were held with Shauka community elders and current pastoralists in the Chaudans valley in KSL India. In KSL Nepal, two focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with Shaukas in the Api and Nampa valleys each. Two FGDs were conducted with Humli Bhotiya herders in upper Karnali and Limi valleys each. Two different open-ended questionnaires were designed keeping in mind the governance systems in India and Nepal. The questions were aimed to gather information on the traditional systems of rangeland governance and migratory pastoralism, the present day governance systems, historical and present-day experience of transborder pastoralism, and new livelihood strategies and aspirations among traditionally agro-pastoralist communities.

Results

Traditional institutions related to migratory pastoralism

Traditional institutions in KSL India

The Shauka tribes inhabit the northern, China-bordering reaches of districts Pithoragarh, Bageshwar, and Chamoli in the Uttarakhand state of India and include groups such as Byansis, Chaudansis, Darmis, Joharis, and Jaads. Some Byansi Shaukas also live in the Nepali parts of the Mahakali valley that borders India. The habitations of the Johari, Darmi, Chaudansi, and Byansi Shaukas are located within KSL India. The Shaukas follow syncretic strains of Hinduism and animism and speak dialects that represent a mix of Tibetan with Kumaoni. But all Shaukas consider themselves as belonging to the ‘Rajput’ caste of the Hindu caste system and follow patriarchy. Traditionally, the Shauka socio-economy was centred upon Indo-Tibetan trade and facilitated by seasonal transhumance. Goats and sheep were central to this trade, being the mode of freight of merchandise for the trade, as well as providing milk, meat, and wool for both local use and trade (Raipa Citation1974).

Each Shauka group resided in a separate tributary valley of either the Mahakali or the Ganges river system and practiced annual cycles of transhumance between downstream, low-altitude winter settlements, and upstream, high-altitude summer settlements (Chatterjee, Citation1976). Furthermore, each Shauka group distinguished themselves into ‘kunchas’, that is, those who practiced transhumance, and ’anwals’, that is, shepherds who practiced nomadic pastoralism (Hoon Citation1996). ‘Kuncha’ implied a family and livestock caravan that would migrate to the high-altitude villages in summer to cultivate crops and graze their animals. ‘Anwal’ implied a person whose main source of livelihood was livestock rearing rather than agriculture, and whose spatial mobility was primarily influenced by the livestock herds in relation to the resources of a place. Shauka ‘anwals’ were not necessarily related to the ’kunchas’.

Each Shauka village would migrate as a whole every year between the winter settlements and higher altitude summer settlements, which were scattered at fixed locations (). The ‘anwals’ grazed their livestock (largely goats and sheep, with some yaks and yak/cow crossbreeds) in high-altitude alpine rangelands called ‘bugyals’ that lay at the most two-day walk away from the summer settlement. For the annual Indo-Tibetan trade, the Shauka traders used the summer settlements as depots, and ‘animal trains’ composed of hundreds of sheep and goats to transport merchandise. Each Shauka group would use a pass lying at the head of their particular tributary valley to enter Tibet, and a Tibetan trade mart not far from this pass for trading. When in Tibet, their livestock were allowed to graze in rangeland areas around border market towns such as Gyanema Mandi and Taklakot (Sherring Citation1906).

Figure 3. Traditional transhumance routes in the KSL, as described in key informant information and Pant (Citation1935).

In India and Nepal, the ‘kunchas’ used the seasonal migration routes of the Shauka ‘anwals’ but grazed their animals on rangelands lying closer to the summer settlement than the ‘bugyals’ (Hoon Citation1996). In winter, the Shaukas either grazed their animals in the forests near their low-altitude winter settlements or grazed them further south in the forests of the Bhabar – the piedmont plains region immediately south of the Shauka homeland in India – and the Terai of far western Nepal. Both ‘kunchas’ and ‘anwals’ had a symbiotic relationship with the sedentary communities along the migration route, which included the flocks enriching the farmlands with animal manure, provisioning of sedentary communities with livestock products, clearing of stubble and weed by the grazing animals, and provision of resting places and food supplies to the herders by the sedentary communities (Pant Citation1935). During the winter, traders from the various Shauka groups would converge at Indian trade marts lying at the Himalayan foothills, such as Haldwani, Tanakpur, Almora, etc.

The customary management of bugyals involved the division of these rangelands into hundreds of named pastures of various sizes. They were not fenced, but the boundaries were known to all and enforced by the village head. The carrying capacity was assessed on the basis of size, altitude, and forage conditions and used to determine the number of animals allowed on each pasture. The pastures were allotted to households in proportion to the number of animals owned. A locally appointed grazing tax collector maintained records of the number of sheep on each pasture and periodically reassessed the carrying capacity by gathering information on the forage conditions from the shepherds. The pastures were first allotted to Shauka households; surplus pastures were then allotted to non-Shauka shepherds on a first-come, first-serve basis. There was no common pasture open to all. The Shauka custom allowed transit shepherds the use of leased pasture for one night only to avoid overgrazing. The Shauka herders leased bugyals into several smaller plots based on topography and altitude and periodically rotated the actual grazing site for the sheep by moving them through the subplots in sequence, thereby preventing any single area from being over-grazed (Hoon Citation1996: 106–107).

Traditional institutions in KSL Nepal

Humla district lies at the northwestern corner of Nepal, sharing its northern and northwestern borders with the Ngari Prefecture of TAR, China. The higher reaches of district Humla are inhabited by the Humli Bhotiyas, a culturally and linguistically Tibetan group. The Humli Bhotiya community has traditionally resided in the Nyin, upper Karnali, and Limi valleys of district Humla. For this community, migratory pastoralism was till recent times among their most important livelihood strategies (Gurung Citation2008; TU Citation2010). The practice of polyandrous marriage system was the prevalent form of traditional social organization among the Humli Bhotiyas. It was amenable to a lifestyle that depended upon annual seasonal pastoral migrations, as well as the maintenance of a subsistence level agriculture per household (Levine Citation1988; Lama Citation2002). Under this organization, the elder brother would stay at home, taking care of the estate, while the younger ones would migrate with the sheep and yak caravans for grazing and trade. Each village in Humla traditionally defined and recognized rangelands for each season (TU Citation2010). The rangelands were communally owned and each year lots were drawn to determine which families would use which grazing areas. In contrast, agricultural lands were normally owned on a household basis. Trade and pastoralism were largely conducted by members of the upper and middle strata of the Humli Bhotiya community. In Limi valley, these comprised over two-thirds of the total population. The lowest and poorest rungs subsisted on agriculture, practiced mostly in marginal landholdings and sometimes through shifting agriculture, and various crafts (Goldstein Citation1975; Haimendorf Citation1975).

Humli Bhotiyas raised yak, goats, and sheep, for all of which they depended upon seasonal pastoral migrations (Haimendorf, Christoph von Furer Citation1975). The Bhotiyas of Limi valley had a distinct system of local and transborder grazing cycles. During the summer, they grazed their animals among the high-altitude rangelands of the main and tributary valleys of the Humla Karnali and Limi rivers. During the winter, yak, sheep, and goat herds from Limi valley would be taken to rangelands lying deep in Tibet (China) under customary arrangements (Goldstein Citation1975). Reciprocally, the Tibetans residing in the border village of Shera had customary grazing rights in the Limi valley. During the summer, the Humli Bhotiya herders from the other valleys used to take their animals to grasslands higher up in the upper Karnali valley or in its tributary valleys bordering the Limi valley. During winter, these herders would take their herds down to rangelands located in Nepali mid-hill districts that bordered Humla on the south, such as Accham, Doti, and Bajura. ().

Trade was an important corollary activity to pastoralism for all Humli Bhotiyas. The Humli Bhotiyas of Limi valley would trade grain obtained from Simikot (Humla) in Tibetan borderland trade marts like Taklakot for wool and salt, and their pastoral produce (especially livestock younglings) with communities from the neighbouring Nepali district of Mugu to the east. Humli Bhotiyas from the upper Karnali and Nyin valleys not only traded in Tibet but also extensively with the Hindu communities of the bordering mid-hill Nepali districts to the south. While yak would be used as freight animal by the residents of Limi valley for trade with Tibet, the preferred choice of freight animal in general among the Humli Bhotiyas was highland and lowland varieties of sheep (Haimendorf, Christoph von Furer Citation1975). These intertwined practices of pastoralism and trade were highly lucrative economically as well as in terms of ensuring food security for the Humli Bhotiyas. In erstwhile times, salt and wool, brought down by Humli Bhotiya traders from Tibet and Humla’s higher valleys, were highly in demand among the Nepali mid-hill and even Terai communities. Each unit of salt or wool could fetch several units of barley and rice (Goldstein Citation1975; Haimendorf, Christoph von Furer Citation1975).

Traditional institutions in KSL China

Prior to the annexation of Tibet to China in 1959, the indigenous Drokpa communities in KSL were part of a system in which the land was owned by high reincarnate religious figures, aristocratic families, or monasteries – kinds of ‘lords of the estate’ – and the ultimate authority was the central government in Lhasa, headed by the Dalai Lama (Goldstein and Beall Citation1990). The nomadic families were subjects to the lord, to whom they paid taxes and corvee labour services. The lord in turn appointed officials who maintained law and order and managed disputes. The nomadic families owned their herds, managing and disposing off them as they wished. However, they were not free to leave the estate and move with their livelihood to the estate of another lord, without the new lord having to negotiate a payment with the old lord. The nomadic families were thus bound to the lord and the estate. Beneath the lord, the next key institution was the family. Members of a family shared a tent, cooked and ate together, and jointly managed their herd, decisions being made by the family head. Sharing and cooperation within the family contrasted with a norm of fierce independence between families. The ideal for nomad families was to be self-contained units, and they preferred to hire nomads from the class of poor and indigent nomads than negotiating with neighbours for tasks such as herding (Goldstein and Beall Citation1990: 55).

The nomadic estate was divided into hundreds, or thousands, of named rangelands of various sizes, with delimited borders recorded in a register book. Although these pastures were not fenced off, boundaries were known to all and enforced by the officials of the estate. Households received rangelands proportionate to the number of animals owned, including multiple rangelands appropriate for use in different seasons. Nomadic custom allowed a migrating nomadic family to use any group’s rangeland for one night in transit, but no longer than that. Nomad families were completely independent of each other and there was no common rangeland. Even nomadic migrations happened between different rangelands allotted to the same family. The traditional system balanced rangelands and livestock by shifting rangelands between families according to the results of a once-in-three-years survey conducted by the lord and his officials. It involved making various kinds of shifts of herds and nomadic households from one rangeland to the other, depending upon how fluctuations in a herd size could be matched to the productive capacity of the land (Goldstein and Beall Citation1990: 69–70).

The majority of nomadic families had a base, usually a traditional winter settlement, where they built a house and barns, and moved from there to different rangelands at different times of year (Miller Citation1998). Unlike the Shaukas or the Humli Bhotiyas, the Drokpas did not move from one climatic region to another, since all of the area had a similarly harsh climate. Instead they moved shorter distances of around 15–70 km rotating the rangeland area and tracking favourable forage conditions. Established migratory routes, with regular encampment areas, were followed year after year (Goldstein and Beall Citation1990). The nomads followed a traditional multispecies grazing system with yaks, sheep, goats, and horses grazing together to maximize the use of forage, as different species graze different plants. The different animals also had different uses and provided a diverse range of products for home consumption or sale. Maintaining multiple species in herds also minimized the risk of total livestock loss from disease or severe winter storms and provided some insurance that not all animals would be lost and herds could be rebuilt (Miller Citation2000). The nomad families also traded salt and wool from the plateau with the southern Himalayan communities such as the Shaukas and the Humli Bhotiyas, both in Tibetan borderland marts as well as marts located close to the border in KSL India and KSL Nepal (Pant Citation1935; Haimendorf, Christoph von Furer Citation1975; Goldstein and Beall Citation1990). They also developed complex relations with agricultural communities outside the pastoral areas within Tibet as well, in which farmers provided them with barley, their staple diet, in exchange for livestock products (Miller Citation2000).

Contemporary institutions governing migratory pastoralism in KSL: intersections between the state and tradition

In the past, both the practice of migratory pastoralism and the rangeland resource base it depended upon were governed by flexible but well-defined customary institutions. However, these institutions have undergone a significant transformation, first as a result of the trend in all the three countries towards centralized governance structures, and second through the later trend towards increasing decentralization that saw local communities again becoming involved in the management of local natural resources, but now within new networks of polycentric governance (Ghate Citation2008). The present day institutions are described in the following.

KSL India and KSL Nepal

In India, the ‘Report on the Task Force on Grasslands and Deserts’ (GoI Citation2007) noted the urgent need for a National Grazing Policy to ensure the sustainable use of grasslands and biodiversity conservation. Yet, there is still no government institution or policy at the national level with the sole mandate of managing pastoral issues. At state level, the Departments of Agriculture, Animal Husbandry, Environment and Forests, and Revenue jointly implement various development programmes for the Himalayan pastoralists. All the Himalayan states have Animal Husbandry departments as separate or subsidiary units of Departments of Agriculture (Köhler-Rollefson, Morton, and Sharma Citation2003) that are involved in livestock development programmes, but their major focus is on settled farmers. The Revenue and Forest Departments are responsible for pasture development. In KSL India, rangelands are now managed largely through the institution of van panchayats. These represent a hybrid of state ownership and community responsibility. A van panchayat is managed by a forest committee which is guided by Revenue Department rules and technical advice from the Forest Department (as per the Indian Forest Act of 1927). The van panchayat is governed by rules developed and implemented by the communities regarding the use, monitoring, sanctions, and arbitration of conflicts. Customary rights to graze are also subsumed. As such, open access is avoided. Van panchayats are a form of CPRs, since they have (a) an identifiable user group, (b) finite subtractive benefits, (c) a susceptibility to degradation when used beyond a sustainable limit, and (d) are agreed upon by local users as a collective property which is indivisible (Mukherjee Citation2003).

In Nepal, the Nepal Rangeland Policy came into effect in 2012 and is currently being piloted in Bajhang district. The policy focuses on involving local pastoralist communities in managing rangelands. The pilot is in an early phase and the impact cannot yet be assessed. In KSL Nepal, rangeland management is generally carried out at the level of the community forest user group (CFUG) as notified by the Forest Department. The CFUG areas are managed by local village communities according to a work plan prepared by the communities working with the local Forest Department (as per the Nepal Forest Act of 1993).

In KSL India and KSL Nepal, migratory herders generally have traditional and statutory grazing rights in the van panchayats or CFUGs of the village in which they reside. However, when they move through rangelands belonging to other villages, they need to pay a nominal fee per animal to the van panchayat committee or CFUG of the other village. Due to poor reach of the state institutions, some remote rangelands in both KSL India and KSL Nepal either continue to be managed solely by customary institutions or are open access sites.

KSL China

In KSL China, as elsewhere on the Tibetan Plateau, many of the customary institutions of rangeland management disintegrated under the collectivization of pre-reform China. This centralized approach to control and exploitation of natural resources proved to be a failure, and after the breakdown of the communes, the use and control of the pastures went back into the hands of the local users. But the pastoralists had largely lost their traditional systems for organizing themselves to manage resources cooperatively, and in many places, this resulted in a tragedy-of-the-commons situation (Jiang Citation2005; Wang, Brown, and Agrawal Citation2013).

Reforms in the 1970s and later replaced collectives with a system of state-ownership of land in which pastures were leased out to individuals and communities for local level management. The Grasslands Law (1985), revised in 2002, is the primary law regulating land tenure in grasslands. It decentralizes control from the state to rangeland users. The Grasslands Law introduced the Pasture Contract System (PCS), an extension of the Household Contract Responsibility System for agriculture, to former communes in pastoral areas. The PCS grants ownership of rangelands to the state or collectives, which may grant 50-year contracts (an increase from the 30-year contracts used before 1996) and use right certificates to individual households for animal husbandry. The contracts set out individual household boundaries, seasonal pasture allocations, stocking rates (to be enforced by the Animal Husbandry Bureaus), pasture use fees, and a duty to sustain rangeland productivity. Individualized, exclusive, and transferable property rights and use fees seek to encourage users to view land as a production factor, not a ‘free good’ (Nelson Citation2006, 391–392).

In 2002, the ‘tuimi huancao’ (Restore Pastures to Grass) policy was initiated with the aim of resettling pastoralists into concentrated settlements with infrastructural assets. The Grasslands Law of 2002 supplemented the tuimi huancao by encouraging a new division of labour, in which pastoralists would be turned into labourers outside the region and professionals in other trades. It also supported the introduction of centralized livestock breeding and extension and support services (Kreutzmann Citation2011). In addition, the Rangeland Ecological Protection Reward and Compensation Mechanism was introduced in 2009 on the Tibetan Plateau as a payment for ecosystem services (PES) programme under which monetary compensation was to be given to pastoralists for reducing their herds to sizes deemed by the government to be sustainable (Cencetti Citation2013).

The decline of migratory pastoralism in the KSL: the role of geo-political, political-economic, and cultural transformation

The decades following the annexation of Tibet to China in the 1950s witnessed a strengthening of the reach of state and statutory institutions in these borderland regions and an increasingly rapid erosion of the attributes of SES which had earlier provided the optimum conditions for migratory pastoralism to flourish across the KSL.

Impact of the closure of international borders

The Indo-Chinese border conflict in 1962 brought the highly profitable Indo-Tibetan trade to a sudden and near complete halt by the closure of the Indo-Chinese border. In the absence of the profits from trade, the annual migratory pastoralist movements of the Shaukas between the summer and winter settlements became increasingly unsustainable. This led to a decline in the numbers of livestock owned by the Shauka ‘anwals’ as well as a gradual decline in migratory pastoralist movements (Negi Citation2007). The border settlement between Nepal and China during the 1960s caused new and gradually increasing restrictions on movements for both Humli Bhotiyas and Drokpas (Goldstein Citation1975; Bauer Citation2004). The transborder trade between Humli Bhotiyas and Drokpas gradually decreased due to the availability of cheap iodized salt from India and grain from China (Gurung Citation2008). Starting in the 1980s, the Chinese and Nepalese Governments began by mutual agreement to gradually decrease the amount of transborder grazing permitted (Banjade and Paudel Citation2008). Interviews with Humli Bhotiyas revealed that all transborder grazing was formally stopped between by the early 1990s. The loss of summer and winter rangelands in Tibet (China) was cited by interviewees as one of the most important reasons for the decline of migratory pastoralist activity in Humla. However, as an informal, local-level transborder deal, Drokpa herders from Tibet (China) are still allowed to graze their yak herds in the rangelands of Limi valley, in exchange for Humli people to have access to the daily wage labour market in Taklakot.

On the Indo-Nepal border, field studies revealed that the Shauka ‘anwals’ from KSL India had generally stopped migrating to the rangelands in the nearby districts in Nepal due to (a) an increase in customs tax per unit livestock and its strict implementation; (b) strict implementation of quarantine rules along the Indo-Nepalese border, and the need to provide a medical certificate assuring the health of the herd, and (c) a threat to life and property during the Maoist insurgency in Nepal, which had led to several Shauka herders dependent on the Nepalese rangelands selling off their herds. Nonetheless, one case of customary transborder migratory pastoralism is still intact among the Shaukas. The Byansi Shaukas from the border village of Garbyang (India) annually conduct pastoral migrations to rangelands lying next to the border Byansi Shauka villages of Chhyangru and Tinker (Nepal), where they are also allowed to collect the highly valuable ‘caterpillar fungus’ (Ophiocordyceps sinensis). Nobody from outside these three villages is allowed to either graze or collect herbs in this area. These three villages claim strong continuing cultural ties, fostered by intermarriage and customary grazing rights that predate the international border demarcation between India and Nepal.

In terms of policy provisions for cross-border grazing, there are some signs of potentially cooperating on transborder grazing. One of the stated aims of the Nepal Rangeland Policy of 2012, presently being piloted, is to simplify the process for the renewal of existing transborder grazing agreements with neighbouring countries. An article in The Economist (Citation2012) mentions a deal between the Chinese and Nepalese governments to provide grazing rights to borderland pastoral communities on both sides of the Nepal–China border. However, the fieldwork in Humla showed that this provision has not yet been implemented. A more state-monitored and regulated form of transborder trade has been permitted at Taklakot for the Humli Bhotiyas since the 1970s and for the Shaukas since the early 1990s. But transborder grazing remains out of bounds.

Friction between statutory institutions and migratory pastoralism

In KSL India, the rangelands and forests lying along the migration routes ceased to be solely under customary institutions of governance during the colonial era (Bhattacharya Citation1998). Grazing is not allowed at various stretches of forests protected by the state as ‘RFs’. Interviews revealed that sometimes the forest guards and beat officers allowed them to graze in RFs for small bribes of money, tea, or grain, but at other times, they were fined. Gerwin and Bergmann (Citation2012, 102) show that overall, the efforts of the Forest Department to control the implementation of rules for extracting resources in KSL India is rather low, especially in the high-altitude rangelands, and the villagers themselves prefer to rely on informal, customary institutions.

There are also significant incompatibilities between the provisions of the formal institutions that provide vital ancillary support to pastoral practices and the demands of the herders. In KSL India, graziers obtain monthly rations of like rice, flour, sugar, and oil from the Department of Civil Supplies. With the decline of customary transhumance, state provisioning of such basic needs has become a vital ancillary service for migratory pastoralism. However, during interviews, the herders said that they needed the rations for 6 months in one go when they migrated to the high-altitude pastures for there were no restocking stations along the route. But under the existing rules, graziers, like all others, could get rations only for 1 month at a time and had to buy supplies for the additional 5 months on the black market. That greatly increased the costs of migratory grazing. Another important state service provider for the migratory pastoralists, the Department of Animal Husbandry, also has some dispensaries and outlets in summer settlements like Milam. But these outposts are few and far between and often plagued with logistical problems such as lack of availability of personnel and medicine. Finally, employment under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme is only available in the winter settlements.

The availability of state veterinary services is also poor in KSL Nepal. But more importantly, the setting up of CFUGs undermined the interests of migratory pastoralism. Banjade and Paudel (Citation2008, 51–55) explain how the community forestry programme had the unintended consequence of favouring sedentary communities over herders. The dominant groups limited the idea of ‘community’ to the sedentary community with more permanent and regular use claims. The herders were unable to contest this and have adopted various coping strategies to protect their livelihoods. The fieldwork showed that the traditional rangelands for Humli Bhotiya herders in the bordering southern districts had become difficult to access as the rights of the sedentary communities were preferred. Furthermore, where they were allowed to graze, they needed to pay a grazing fee per animal.

On the Tibetan Plateau (China), current pastoral development policies to privatize rangelands, settle nomads, and introduce ‘modern’ livestock production technologies are greatly altering the traditional nomadic pastoral production systems. Both tuimu huancao and the rangeland PES programme restrict migratory herd movements between seasonal rangelands in favour of smaller, fenced pastures and growing of fodder (Kreutzmann Citation2011; Yonten Nyima, personal communication 2015). The traditional composition of nomads’ herds is being restructured along Western style commercial livestock production guidelines (Miller Citation2000). The privatization of natural resource use rights on the Tibetan Plateau, as under the Household Responsibility System, has also been seen to increase disputes and change the traditional social relations (Chen and Xiaoye Citation2009).

Migration into and out of KSL

In India, the Shauka community was accorded a ‘Scheduled Tribe’ status by the Government of India in 1967, making higher education and employment opportunities in state institutions all over India more accessible to all Shaukas. With the cessation of Indo-Tibetan trade, many Shaukas began to migrate outside the KSL region to make use of these economic opportunities, or to newly emerging markets in former winter settlements that were better connected (Hoon Citation1996; Negi Citation2010; Gerwin and Bergmann Citation2012).

At the same time, in-migration of Gaddi pastoralists with their flocks of sheep and goats from the neighbouring Indian state of Himachal Pradesh has added both competition for and pressure on the rangelands in KSL India. This influx started in the 1970s when the Gaddis were uprooted from their original villages as a result of major dam-building projects and conversion of their traditional grazing grounds to agriculture. In earlier times, the Shaukas welcomed the Gaddis as the rangelands were abundant (Hoon Citation1996). The Gaddis have to pay a small fee per animal for grazing in the van panchayats. In the interviews, some Gaddi herders reported that the Shauka communities were very helpful when they suffered large losses in livestock during the 2013 flash floods in Uttarakhand. But most of the Shauka graziers said that they viewed the Gaddi graziers as competitors. The Gaddis were seen as more resourceful, possessing larger herds and able to dominate the winter grazing grounds, one reason cited by Shauka herders for having to reduce the size of their own herds. At the same time, the fieldwork showed that many Gaddis had become hired herders for Shauka families.

Alternative livelihood options within KSL

In KSL India, the government sector remains the primary magnet drawing pastoralists to alternative livelihood options both within and outside KSL. Sedentary animal husbandry that can be combined with agriculture has also emerged as an important option for both Indian and Nepali Shaukas. Manual labour in state development projects such as road and hydropower construction is another alternative for them. For Humli Bhotiyas, the opportunity for manual labour work in construction and road-building projects in KSL China at daily wages nearly three times as high as in Nepal is an important factor drawing them away from pastoralism. Another emerging lucrative source of income is harvesting of medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) from the wild (Negi Citation2007; Gerwin and Bergmann Citation2012). Some MAPs like Picrorhiza kurrooa, Aconitum herterophyllum, Dactylorhiza hatagiera, Chaerophyllum villosum, Pleurospermum angelicoides, and O. sinensis bring in high remuneration, although their extraction is illegal. Shauka households that undertake casual labour are reported to be more involved in MAP collection than those in government service, as are those with less land and lower earnings from other sources. Harvesting for 3–5 months a year provides significantly more income than migratory pastoralism over a whole year (Negi Citation2010). In KSL China, the main source of income is still animal husbandry. But transportation and ancillary services for tourists and pilgrims visiting Mt. Kailash are also lucrative livelihood options. With heavy government investment and subsidies, commercial cropping of land and growing oil seed are also emerging as important options (IGSNRR Citation2010).

Changes in cultural perceptions towards migratory pastoralism

Among the Shaukas, Humli Bhotiyas, as well as the Drokpas, migratory pastoralism is increasingly perceived as a ‘backward’ or ‘primitive’ occupation. The Shauka and Humli herders tend to send their children to schools and colleges for formal education, often in towns in the Himalayan foothills, so that the next generation can have ‘better’, and ‘more respectable’ job options (field observation). School education, state development agenda, the influence of electronic media, and tourism all contribute to the negative perception of migratory pastoralism (Gurung Citation2008; Negi Citation2010). On the Tibetan Plateau, the nomadic lifestyle of the Tibetan tribes has been commoditized in the form of packages providing an ‘authentic Tibetan experience’ to tourists, while at the same time, the traditional pastoral practices are seen as ill-informed and even ecologically harmful (Kreutzmann Citation2011).

Discussion and conclusions

Under the traditional systems of migratory pastoralism, the rangelands were not used as free-for-all commons which could result in a ‘tragedy of the commons’ condition as claimed by Hardin (Citation1968). Rather, the Shaukas, Humli Bhotiyas, as well as Drokpas, practiced migratory pastoralism on rangelands which they used as CPRs with well-defined rules of access, management, cyclical movements, and conflict resolution. The right to alienation was forbidden in practice either by custom (as in the case of Shaukas and Humli Bhotiyas) or by the larger networks of governance under which these herders worked (as in the case of the Drokpas). Besides, transborder grazing rights were a part of a broader regime of reciprocity that sustained ties of trade and kinship between these communities. These rights, facilitated by open borders, provided for a larger biophysical resource base for migratory pastoralism. Alongside, customary symbiotic ties with communities along the migration routes kept the transaction costs of migratory pastoralism low.

The changes in geo-politics and natural resource governance regimes since the mid-twentieth century have redesigned the commons, devolving certain powers of natural resource management to local communities but simultaneously nesting them in new networks of polycentric governance. In van panchayats, users continue to be proprietors of the local natural resources, and in CFUGs, users even possess limited rights to alienation (Agrawal and Ostrom Citation2001). That, however, implies a property rights regime more beneficial to sedentary pastoralism than migratory pastoralism. Access to traditional rangelands has become more constricted in a regime where herders have to pay to pass through rangelands other than those of their van panchayat or CFUG; where there are often illegitimate rents involved in passing through protected forest areas, and where transborder rangelands have become out of bounds. In KSL China, the move has been in the opposite direction, towards a largely top-down model of rangeland management based on rangeland privatization, reduction of user pressure on rangelands through resettlement, and livelihood diversification policies. The users of these privatized grazing parcels are entitled as individual or household level owners, but closely regulated by a state apparatus that favours western paradigms of grazing management, such as fencing and destocking, over local, communal capacity, and traditional ecological knowledge (Cencetti Citation2013). Alongside, state-provisioned ancillary services that are supposed to serve citizens better seem oblivious to the particular attributes of pastoral communities. With this decrease in the viability of migratory pastoral practices, KSL’s communities are adapting their livelihood strategies in a variety of ways. In some contexts, traditional transborder grazing rights are used as a bargaining point to gain access to lucrative new opportunities, whether it be the case of Shaukas from Garbyang going to Nepal to collect the ‘caterpillar fungus’, or the Humli Bhotiyas getting daily wage labour in Taklakot (China) in exchange of allowing Drokpas to graze in Limi rangelands. In other cases, there is a complete shift from grazing towards new opportunities afforded by government schemes and development projects and also a paradigmatic shift in how older generations of herders want the younger generations to grow up in a globalized economy, with emerging opportunities for education and physical-cum-economic mobility. Looking from a perspective of ‘institutional bricolage’ thus allows for a more nuanced picture to emerge, regarding how the overall decline in migratory pastoralism is being negotiated at the everyday local as well as trans-local levels. Such a perspective also indicates sites where more dialogue is needed between actors located at different levels, so to enable to an improved and sustainable flow of access to users as well as ecosystem services in the rangelands of KSL.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mr. Basant Pant from the International Center for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) and Dr. Yonten Nyima from the Chinese Academy of Sciences for their valuable inputs on pastoralism in KSL Nepal and KSL China, respectively. This study was partially supported by core funds of ICIMOD contributed by the Governments of Afghanistan, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Norway, Pakistan, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The views and interpretations in this publication are those of the authors and are not necessarily attributable to ICIMOD.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Abhimanyu Pandey

Abhimanyu Pandey is a cultural ecosystem services analyst at ICIMOD. Previously, he completed an MPhil in Development Studies from the University of Cambridge, UK, as a Commonwealth Scholar. He also has an MA in Sociology from the Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, India. He has ethnographic and qualitative research experience in Copenhagen, Old Delhi, and several remote regions of Himachal Pradesh and has been a Charles Wallace Fellow at the British Library, London. At ICIMOD, Mr Pandey is working on developing methods for assessing the biocultural diversity of the Indian and Nepalese parts of the Kailash Sacred Landscape and is involved in an institutional study of rangeland governance in the Landscape and efforts to promote heritage tourism.

Nawraj Pradhan

Nawraj Pradhan is Associate Coordinator for the Kailash Sacred Landscape conservation and Development Initiative and ecosystem management analyst at ICIMOD. He has professional experience in Australia and south Asia, including in programme and project management, with technical experience in climate change adaptation, ecosystem services, environmental impact assessment, and corporate social responsibility. He has worked with diverse rural communities in the field on a range of current ecosystem management issues. As a researcher, he has designed and executed participatory approaches and methodologies on valuation of ecosystem services. He has published articles and research briefs and presented at international conferences, forums, and networks on innovative ecosystem management, and climate change adaptation approaches. He holds a master’s degree in environmental management from the University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

Swapnil Chaudhari

Swapnil Chaudhari is a Programme Officer in the Kailash Sacred Landscape conservation and Development Initiative at ICIMOD. He has been involved in various global and national projects related to biodiversity conservation, climate change adaptation, and ecological restoration with institutions such as UNEP-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC), Cambridge; the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), Delhi, India; the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Kharagpur; and the Centre for Development in Advanced Computing (C-DAC), India. In 2013, he completed an MPhil in Conservation Leadership at the University of Cambridge. He has been engaged in extensive field expeditions covering different ecosystems of India including the central dry grasslands.

Rucha Ghate

Rucha Ghate is Senior Governance and NRM Specialist at ICIMOD. Before joining ICIMOD she was Director (Research) at SHODH: The Institute for Research and Development, Nagpur, India. Rucha’s research interests lie in common pool resources, collective action, and institutions. She has conducted several studies on the human aspects of natural resources – traditional knowledge, governance, and impact of government policies. She has also taught environmental economics and research methodology courses at Nagpur University, India; Asian Institute of Technology, Thailand; TERI University, New Delhi; and Mekong Institute Foundation, Thailand. She has published in several international and national journals, authored two books, and co-edited one book. Rucha has received several fellowships, including a post-doctoral overseas fellowship in Environmental Economics, two writing fellowships at Indiana University in 2004, and 2011, the (shared) Karl Goran Maler scholarship at Beijer Institute, Stockholm, Sweden, in 2009, and at the University of Michigan, USA, in 2009.

References

- Agrawal, A., and E. Ostrom. 2001. “Collective Action, Property Rights, and Decentralization in Resource Use in India and Nepal.” Politics and Society 29 (4): 485–514. doi:10.1177/0032329201029004002.

- Atkinson, E. T. 1884[1996]. The Himalayan Gazetteer, Vol II, Part I. Dehra Dun: Natraj Publishers.

- Ayers, C. 1962. The Theory of Economic Progress. 2nd ed. New York: Schoeken Books.

- Banjade, M. R., and N. S. Paudel. 2008. “Mobile Pastoralism in Crisis: Challenges, Conflicts and Status of Pasture Tenure in Nepal Mountains.” Journal of Forest and Livelihood 7 (1): 49–57.

- Bardhan, P. 2002. “Decentralization of Governance and Development.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 16 (4): 185–205. doi:10.1257/089533002320951037.

- Bauer, K. 2004. High Frontiers: Dolpo and the Changing World of Himalayan Pastoralists. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Bergmann, C., M. Gerwin, M. Nüsser, and W. S. Sax. 2012. “State Policy and Local Performance: Pasture Use and Pastoral Practices in the Kumaon Himalaya.” In Pastoral Practices in High Asia, edited by H. Kreutzmann, 175–194. Netherlands: Springer.

- Bhattacharya, N. 1998. “Pastoralists in a Colonial World.” In Nature, Culture, Imperialism: Essays on the Environmental History of South Asia, edited by D. Arnold and R. Guha, 49–85. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Brown, C. W. 1984. The Goat Is Mine, the Load Is Yours: Morphogenesis of Bhotiya-Shauka, U. P., India. Dissertation, Lund University. Lund: Department of Social Anthropology, Lund University.

- Cencetti, E. 2013. ‘Rangeland Ecosystem & Pastoralism in Tibet: A review of From ‘Retire Livestock, Restore Rangeland’ to the Compensation for Ecological Services: State Interventions into Rangeland Ecosystem and Pastoralism in Tibet, by Yönten Nyima.’ Accessed 11 May 2015. http://dissertationreviews.org/archives/3733

- Chatterjee, B. B. 1976. “The Bhotias of Uttarakhand.” India International Centre Quarterly 3 (1): 3–16.

- Chen, Y., and Z. Xiaoye. 2009. “How to Define Property Rights? A Social Documentation of the Privatisation of Collective Ownership.” Polish Sociological Review 3 (167): 351–372.

- Cleaver, F. 2002. “Reinventing Institutions: Bricolage and the Social Embeddedness of Natural Resource Management.” The European Journal of Development Research 14 (2): 11–30. doi:10.1080/714000425.

- Connell, R. W. 1987. Gender and Power: Society, the Person, and Sexual Politics. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

- Dong, S., D. James Lassoie, E. S. Pariya, K. K. Shreshtha, and Y. Zhaoli. 2008. “Institutional Development for Sustainable Rangeland Resource and Ecosystem Management in Mountainous Areas of Northern Nepal.” Journal of Environmental Management 90: 994–1003. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.03.005.

- Dong, S. L., Y. Shaoliang, and Z. L. Yan. 2016. “Maintaining the Human–Natural Systems of Pastoralism in the Himalayas of South Asia and China.” In Building Resilience of Human-Natural Systems of Pastoralism in the Developing World, edited by S. Dong, K. A. S. Kassam, J. F. Tourrand, and R. B. Boone, 93–135. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Gerwin, M., and C. Bergmann. 2012. “Geopolitical Relations and Regional Restructuring: The Case of the Kumaon Himalaya, India.” Erdkunde 66 (2): 91–107. doi:10.3112/erdkunde.2012.02.01.

- Ghate, R. 2004. ‘Traditional and Non-Traditional Indigenous Informal Institutions in Orest Management.’ Paper presented at the EGDI and UNU-WIDER Conference on ‘Unlocking the Human Potential: Linking the Informal and Formal Sectors, Helsinki, Finland, 17–18 September.

- Ghate, R. 2008. “A Tale of Three Villages: Practiced Forestry in India.” In Promise, Trust and Evolution: Managing the Commons of South Asia, edited by R. Ghate, N. Jodha, and P. Mukhopadhayay. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- GoI. 2007. Report of the Taskforce on Grasslands and Deserts. Government of India, New Delhi. Accessed 19 August2015. http://planningcommission.nic.in/aboutus/committee/wrkgrp11/tf11_grass.pdf

- Goldstein, M. C. 1975. “A Report on Limi Panchayat, Humla District, Karnali Zone.” Contributions to Nepalese Studies 2 (2): 89–101.

- Goldstein, M. C., and C. C. Beall. 1990. Nomads of Western Tibet: The Survival of a Way of Life. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Goodall, S. K. 2004. “Rural to Urban Migration and Urbanization in Leh, Ladakh: A Case Study of Three Pastoral Communities.” Mountain Research and Development 24 (3): 220–227. doi:10.1659/0276-4741(2004)024[0220:RMAUIL]2.0.CO;2.

- Guha, R. 1989. The Unquiet Woods: Ecological Change and Peasant Resistance in the Himalaya. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Gurung, K. 2008. ‘Sheep Transhumance in Humla: A Declining Practice.’ Accessed 12 May 2015. http://www.socialinclusion.org.np/new/files/kushal-paper_1336386349cmtX.doc

- Hardin, G. 1968. “The Tragedy of the Commons.” Science 162 (3859): 1243–1248.

- Haimendorf, Christoph von Furer. 1975. Himalayan Traders: Life in Highland Nepal. London: John Murray.

- Herrera, P. M., J. Davies, and P. M. Baena. 2014. Governance of Rangelands: Collective Action for Sustainable Pastoralism. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Hoon, V. 1996. Living on the Move: Bhotiyas of the Kumaon Himalaya. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- IGSNRR. 2010. Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation Initiative: Feasibility Assessment Report of China. Beijing: Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resource Research (IGSNRR.

- Jiang, H. 2005. “Grassland Management and Views of Natures in China since 1949: Regional Policies and Local Changes in Uxin Ju, Inner Mongolia.” Geoforum 36: 641–653. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2004.10.006.

- Köhler-Rollefson, I., J. Morton, and V. P. Sharma. 2003. ‘Pastoralism in India: A Scoping Study for DFID, UK.’ Accessed 5 May 2015. http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/pdf/outputs/zc0181b.pdf

- Kreutzmann, H. 2011. “Pastoral Practices on the Move: Recent Transformations in Mountain Pastoralism on the Tibetan Plateau.” In Pastoralism and Rangeland Management on the Tibetan Plateau in the Context of Climate and Global Change, edited by H. Kreutzmann, Y. Yong, and J. Richter. Bonn: GIZ, BMZ.

- Lama, C. 2002. Kailash Mandala. Kathmandu: Humla Conservation and Development Association.

- Leach, M., R. Mearns, and I. Scoones. 1999. “Environmental Entitlements: Dynamics and Institutions in Community-Based Natural Resource Management.” World Development 25 (2): 225–247. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00141-7.

- Levine, N. 1988. The Dynamics of Polyandry: Kinship, Domesticity, and Population on the Tibetan Border. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- McGinnis, M. D. 2011. “An Introduction to IAD and the Language of the Ostrom Workshop: A Simple Guide to a Complex Framework.” Policy Studies Journal 39 (1).Accessed 11 April 2015 doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00401.x.

- Miller, D. J. 1998. “Nomads of the Tibetan Plateau Rangelands in Western China. Part One: Pastoral History.” Rangelands 20 (6): 24–29.

- Miller, D. J. 2000. “Tough Times for Tibetan Nomads in Western China: Snowstorms, Settling Down, Fences and the Demise of Traditional Nomadic Pastoralism.” Nomadic Peoples. New Series 4 (1): 83–109. doi:10.3167/082279400782310674.

- Mukherjee, P. 2003. ‘Community Forest Management in India: The Van Panchayats of Uttaranchal. Paper presented at the XII World Forestry Congress, Quebec.’ Accessed 21 May 2015. http://www.fao.org/docrep/ARTICLE/WFC/XII/0108-C1.HTM

- Namgay, K., J. E. Millar, R. S. Black, and T. Samdup. 2014. “Changes in Transhumant Agro-Pastoralism in Bhutan: A Disappearing Livelihood?” Human Ecology 42 (5): 779–792. doi:10.1007/s10745-014-9684-2.

- Negi, C. S. 2007. “Declining Transhumance and Subtle Changes in Livelihood Patterns and Biodiversity from the Kumaon Himalaya.” Mountain Research and Development 27 (2): 114–118. doi:10.1659/mrd.0818.

- Negi, C. S. 2010. Askote Conservation Landscape: Culture, Biodiversity, and Economy. Dehra Dun: Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh.

- Nelson, R. 2006. “Regulating Grassland Degradation in China: Shallow Rooted Laws?” Asia-Pacific Law and Policy Journal 7 (2): 385–417. Accessed 20 May 2015. http://blog.hawaii.edu/aplpj/files/2011/11/APLPJ_07.2_nelson.pdf.

- Ning, W., and C. E. Richard. 1999. ‘The Privatisation Process of Rangeland and Its Impacts on the Pastoral Dynamics in the Hindu Kush Himalaya: The Case of Western Sichuan, China.’ People and Rangelands. Proceedings of VI International Rangelands Congress, Townsville, Australia.

- North, D. C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Oli, K. P., L. Zhandui, R. S. Rawal, R. P. Chaudhary, S. Peili, and R. Zomer. 2013. “‘The Role of Traditional Knowledge and Customary Arrangements in Conservation: Trans-Border Landscape Approaches in the Kailash Sacred Landscape of China, India and Nepal.’ Chap. 3.” In The Right to Responsibility: Revisiting and Engaging Development, Conservation, and the Law in Asia, edited by H. Jonas, H. Jonas, and S. M. Subramanian. Tokyo: UNU Press.

- Oli, K. P., and R. Zomer, eds. 2011. Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation Initiative: Feasibility Assessment Report. Kathmandu: International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

- Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ostrom, E. 2009. “A General Framework for Analysing the Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems.” Science 325 (5939): 419–422. doi:10.1126/science.1172133.

- Ostrom, E. 2010. “Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems.” American Economic Review 100 (3): 641–672. doi:10.1257/aer.100.3.641.

- Ostrom, E., R. Gardner, and J. Walker. 1994. Rules, Games, and Common Pool Resources. Chicago: University of Michigan Press.

- Pant, S. D. 1935. The Social Economy of the Himalayans: Based on a Survey in the Kumaon Himalayas. London: Allen Unwin.

- Raipa, R. S. 1974. Shauka: Seemavarti Janajati (Samajik Evam Sanskritic Adhyayan). Nainital: Ankit Prakashan. (In Hindi).

- Rawat, G. S., R. S. Rawal, R. P. Chaudhary, and S. Peili. 2013. “Strategies for the Management of High-Altitude Rangelands and Their Interfaces in the Kailash Sacred Landscape.” In High Altitude Rangelands and Their Interfaces in the Hindu Kush Himalayas, edited by W. Ning, G. S. Rawat, S. Joshi, M. Ismail, and E. Sharma, 25–36. Kathmandu: International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

- Ribot, J. C., and N. L. Peluso. 2003. “A Theory of Access.” Rural Sociology 68 (2): 153–181. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.2003.tb00133.x.

- Roy, T. 2003. “Changes in Wool Production and Usage in Colonial India.” Modern Asian Studies 37 (2): 257–286. doi:10.1017/S0026749X03002014.

- Sharma, L. N., O. R. Vetaas, R. P. Chaudhary, and I. E. Måren. 2014. “Pastoral Abandonment, Shrub Proliferation and Landscape Changes: A Case Study from Gorkha, Nepal.” Landscape Research 39 (1): 53–69. doi:10.1080/01426397.2013.773299.

- Sherring, C. A. 1906. Western Tibet and the British Borderland: The Sacred Country of the Hindus and the Buddhists. London: Edwin Arnold.

- The Economist. 2012: ‘Jan 18th. Nepal and Its Neighbours: Yam Yesterday, Yam Today.’ The Economist 18 January. Accessed 18 August 2015. http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2012/01/nepal-and-its-neighbours

- TU. 2010. Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation Initiative: Feasibility Assessment Report of Nepal. Kathmandu: Central Department of Botany, Tribhuvan University (TU).

- Van Schendel, W. 2005. The Bengal Borderland: Beyond State and Nation in South Asia. London: Anthem Press.

- Van Spengen, W. 2000. Tibetan Border Worlds: A Geo-Historical Analysis of Trade and Traders. London: Routledge.

- Wang, J., D. G. Brown, and A. Agrawal. 2013. “Climate Adaptation, Local Institutions, and Rural Livelihoods: A Comparative Study of Herder Communities in Mongolia and Inner Mongolia, China.” Global Environmental Change 23 (6): 1673–1683. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.08.014.

- Wu, N., M. Ismail, S. Joshi, Y. Shao-Liang, R. M. Shrestha, and A. W. Jasra. 2014. “Livelihood Diversification as an Adaptation Approach to Change in the Pastoral Hindu-Kush Himalayan Region.” Journal of Mountain Science 11 (5): 1342–1355. doi:10.1007/s11629-014-3038-9.