Abstract

In this piece, I argue that the marginalized status of ugliness in the field of aesthetics, particularly in aesthetic conversations in the broader field of curriculum, is indicative of an as-of-yet unexplored source for understanding our societal values. The fact that we do not talk about the ugly is reason to believe that there is something that we do not want to talk about, and whenever such is the case, there is often a deep-seated reason as to why. I begin by establishing the case that ugliness is, in fact, a marginal idea in aesthetic conversations. From there, I explore notions of ugliness as interruptive; the treatment of the physically ugly and its implications; and ugliness of thought, both emotionally and through purposeful philosophizing. While I relate each of these back to the study of curriculum within their own sections, I also move forward to explore what an ugly curriculum may look like, utilizing the concept of asymmetry as a grounding ideal.

Public Interest Statement

While it is easy to sell the sentimental, clichéd notion that everyone is beautiful in their own way, the idea that we should truly examine our ugliness is rarely taken up. However, there is much that ugliness can teach us. This text is a meditation for educators on ugliness’s pedagogical possibilities.

And even the prettiest things rot. You fall apart like flowers.—Mrs. Blum, I Am the Pretty Thing that Lives in the Walls

1. Introduction

When I was in the 7th grade I had a crush on a girl. Honestly, I had several crushes that year, and I had something to learn from each of them, but this crush has always stood out in a very particular way. Here’s the scene: I’m in 7th grade and kind of awkward, particularly with girls. It’s the early 90s, so 3-way calling is a thing, but I don’t have it. My buddy CJ does, though. The plan was that I would call him, then he would call this girl—let’s call her Cheryl to cut down on reducing her to an extension of her gender—through his three-way and ask her if she was interested in being my girlfriend. If she said yes, I would chime in and things would go from there (a sneaky tactic, perhaps, but not uncommon among the kids I knew, male and female alike). If she said no, I would stay hushed and that would be that for a few awkward minutes or just hang up. When CJ popped the question, however, things took a turn that I was not prepared for. “J-,” she asked, flabbergasted at the suggestion. “No! He’s ugly!” I was crushed. Not because she said “no,” but because she used that word: ugly. What could have been worse, more debilitating to any developing sense of ego? While I have no recollection of ever thinking myself the handsomest of my peers, I certainly had never considered myself ugly. Having cobbled together my own understanding of what ugliness was from fairy tales, exaggerations of the human form in Horror and Comedy films, and the gross creations of my own imagination, I had to wonder: did she really think I was that? The fact is that she couldn’t have, because mine, as is often the case, was a very private conception, and this is the issue: while the notions of beauty and ugliness are both relative and often deeply personal, there are still general consensuses for what beauty is at any given time and in any given place. When we talk of aesthetics, what we tend to talk about is what is beautiful and what makes it so. What we do not talk about, however, is what is ugly, what makes that thing ugly, or whether the fact of its ugliness renders it meaningless, valueless. Just as ugly people, ugly feelings, and ugly thoughts are overlooked and pushed toward the edges of what we are willing to consider, so too, very often, is the very concept of ugliness. Further, just as there is a cultural curriculum of beauty that instructs us through such course materials as advertisements, television programs and films that idealize beauty for us, as well as trashy magazines that do the same, each of which would have us striving to reach and maintain very particular body images, there is also a curriculum of the ugly. However, whereas so-called beauty teaches us through constant bombardment with images and lulling sounds, ugliness often teaches us by presenting to us that which we would rather not talk about, leaving us with thoughts unspoken yet not unspeakable. Due to its marginalized status in the field of aesthetics and everyday conversation and its pedagogical potential, ugliness deserves a voice in the curriculum conversation. Not only can it be tacitly instructive as to what we value culturally, but also as to why we keep silent about certain subjects, as well as actively creating silence about others.

Schubert (Citation1991) wonders how it is that “educators unwittingly can be so certain about solutions to curriculum problems, when those very problems are embedded within a context of uncertainty amid the most profound questions that beset humankind” (p. 67). With this in mind, I must say that if we are to meditate sincerely on the instructional value of ugliness (or the problem that ugliness proposes for curriculum), we must consider it for its own sake. That is, instead of exploring ugliness toward the end of finding some beauty within it or that it may reveal to us—as Esch (Citation2010) does consistently in her essay extolling the virtues of the show “Ugly Betty,” inadvertently undercutting the value of the ugly as such—we must explore ugliness toward better understanding ugliness as ugliness, without pussyfooting the disquieting task and replacing it with something that is altogether more pleasant; such a displacement would be falling right into the trap that I am seeking to unhinge: allowing the ugly to silence honest conversation through the belief that we’ve solved a deep-seated issue while ignoring the context from which it arises.

Elizabeth Vallance (Citation1991) tells us that aesthetic inquiry “demands that the researcher have both the large perspective of the big picture and a sensitivity to the telling detail” (pp. 168–169). With regard to this, I argue that the “big picture” extends beyond any given aesthetic moment, any singular work of art and into the myriad machinations of the culture that allowed such a moment to be understood aesthetically or such a work to be produced. Therefore, aesthetic inquiry must often extend beyond the field of aesthetics itself to the study of culture and history. Such an exploration must entail at the very least a consideration of several of the domains under which ugliness falls as well as an account of ugliness’s status in the world today and historically.Footnote1

2. The red-headed stepchild of aesthetics: realizing ugliness’s marginalization

Perhaps some of the opening ideas are a bit overstated; ugliness has not been completely left out of the conversation concerning aesthetics.Footnote2 After all, Socrates rather famously debated Parmenides on the subjects of beauty and ugliness, arriving at the conclusion that ugliness is more than the mere opposite of beauty, but rather a concept in its own right (Plato, Citationn.d.). Interestingly, Morris (Citation2016) argues that the Platonic forms have little place in the postmodern context of a world that has seen such atrocities as the dropping of atomic bombs, the Vietnam War, and the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center. What we will find as we continue, though, is that where the Platonic form of Beauty may not have a relevant place in contemporary conversations, ugliness stems from a sort of formlessness that cannot help but pervade any conversation.

Further, we do each have a conception of what it means to be ugly, and phenomena like “ugly dolls,” and the aforementioned television program “Ugly Betty,” which ran for a total of 85 episodes (IMDb, Citation2016), have done anything but blot out the idea of ugliness from modern conversations. Beyond this, one criticism that I hear quite often concerning social media is that people only tend to post “happy” pictures of themselves and their beautiful families and are much more likely to only share optimistic or “positive posts,” creating online profiles that make their lives look perfect. Such a criticism indirectly posits that we should all know that there is enough dirt being swept under that digital rug to fill a desert. No one wants to show their scars; no one wants to share their own ugliness. Better to keep that in a closet somewhere, festering and rotting slowly.

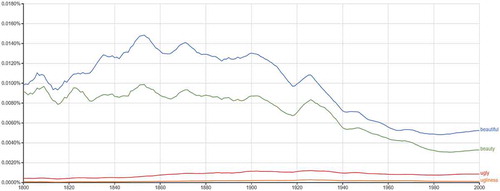

Despite these intrusions of ugliness into aesthetic dialogues, however, the ugly is still a minor player, the Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (Shakespeare, Hamlet, Citation1600) of Beauty’s great tragedy. As shown in Figure , when doing a search for the terms “beautiful,” “ugly,” “beauty,” and “ugliness” using Google’s nGram Viewer engine—which may have its limitations and a leaning toward scientific texts, but still draws from a corpus of over five million books spanning from 1800 to 2008 (Language Log, Citation2010)—we find that while “beautiful” reached its peak in 1853, making up 0.014% of all words recorded in that year and “beauty” reached its peak in the same year at 0.009% of all recorded words, the highest “ugly” ever reached was 0.001% and “ugliness,” the state of being ugly (as opposed to the judgment of owning that state), never reached above 0.0002%.

Figure 1. Comparison of the use of the terms “beautiful,” “beauty,” “ugly,” and “ugliness” 1800–2000

So, there we have it. When we talk about aesthetics, what we tend to focus on is what is beautiful; the ugly gets pushed to the sidelines. Perhaps, then, it is a bit ironic that nearly half of the texts with which I will engage in this piece have the terms “ugly” or “ugliness” in their titles. Ultimately, this is irrelevant, though, as we can clearly see that they are anomalies. With this in mind, and with the understanding that studies in curriculum often seek to find a space for the marginalized, a look into the ugly, its foundations and its implications is more than warranted.

3. Ugliness as interruption

While we all have our own ideas about what is beautiful, these ideas are often mediated through advertising, works of art, television shows, and movies. That is, there are gatekeepers who often decide beforehand what beauty is for us, keeping what they consider ugly (or at least not beautiful enough to be worthy of attention) out of our sight. Douglas (Citation2014) argues that the openness of the internet has created a space without these gatekeepers, one that is more democratized, where anyone with an idea and a connection can broadcast that idea to the world.

Because of this, and often as a statement against normalized beauty, many creators of online content purposefully uglify their creations, not only leaving the edges rough but also roughing them up on purpose.

Often, Douglas (Citation2014) argues, this very ugliness is created out of a sense of authenticity, something to stand against the corporation-generated images that march across our web browsers. One such iteration of ugly content is the meme series “Nailed It.” These memes, which pair highly stylized photographs of crafts or “beauty poses” with failed real-world attempts at re-creating the same crafts and images “normalize imperfection, counteracting the effect of magazines, TV shows, and corporate websites that use technical tools to build an unattainable simulacrum of the world” (Douglas, Citation2014, p. 327). While the case for an actual normalized ugliness is a bit of a longshot, it is safe to say that these images do disrupt the constant stream of beautified images by which we are bombarded. Here, we find that the arts can “help us to learn new things about the world by interrupting us and taking us to other places so that we can ‘release the imagination’” (Morris, Citation2016, p. 33). This “releasing the imagination” is, of course, a reference to Greene’s (Citation1995) work of the same title. Significantly, Greene writes in this piece that “[aesthetic] experiences require conscious participation in a work, a going out of energy, an ability to notice what is there to be noticed in the play, the poem, the quartet” (p. 125). That is, aesthetic experience requires work, it is active. In a strange way, an ugly aesthetic not only works toward challenging common notions of beauty, particularly those instances where beauty is simply manufactured, but also creates a new ground on which surprising instances of beauty may exist. This is not to say that there is any beauty in this ugliness or that beauty needs ugliness as a grounding binary, but rather that through exposure to ugliness, we have a new means by which we can judge when a thing is beautiful on its own versus when it has been manipulated to appear so. However attractive the beautiful appears, this sort of aesthetic goes, at least the ugly is authentic. Things are shitty. Accept it.

There is a danger with this line of thinking, however. Internet Ugly is ultimately a statement against and an aesthetic that arose out of manufactured beauty. Even though I argue that this sort of aesthetic does create a new space for authentic, natural beauty, it also threatens to distract us from it, opting for the eternally ironic. When such is the case, this sort of ugliness (which is itself manufactured) runs the risk of being a hidden mundanity, a bad interruption that does not “generate anything but annoyance. So [we] mustn’t romanticize the notion of interruption” (Morris, Citation2016, p. 36). That is, when the ugly interrupts just for the sake of interrupting, any self-reflective end that it may have achieved is lost in ambiguity, neither one thing or another; it’s nothing special, just ugly.

4. Eschewing the physically ugly

Regarding ugliness and monstrosity, Henderson (Citation2015) tells us that the latter “could be didactic, derivative, comic or commercially valued” (p. 75). While the latter two of these could be rich digging grounds for cultural studies, it is the former that is most pertinent for this particular study. Given this, the didactic nature of ugliness comes to us strikingly in one tale surrounding the mythological Irish king Niall, as well as through tales of the legendary Dame Ragnell.

As the story goes, when the fifth century Irish high king Niall of the Nine Hostages was a young boy, he and three of his companions were seeking water and came upon a well. Before they could receive the water, the ugly, decrepit, wrinkled old hag at the well challenged them to give her a kiss (in some versions of the story, the challenge is to sleep with her). Only Niall met the challenge, and upon doing so, the hag transformed into a beautiful woman. This woman revealed to Niall her metaphoric nature as Sovereignty, informing Niall that only he among his companions was truly fit to take on the sovereignty of Ireland because he was willing to accept the ugliness that such a task entailed. What is implicit in this tale is that whatever beauty there may be in the fame and wealth of sovereignty is starkly overshadowed by the harshness and ugliness wrapped up therein.

Consider this in light of Diane Lee’s (Citation1991) argument that for teachers to be “authentic professionals, they […] have to reject notions of fixed values, fixed goals, fixed objectives, fixed truths” (p. 119). The classroom is a messy place, and while it may be easier, tidier, more pleasant, to work out of a fixed set of standards and objectives, whatever apparent beauty may come from such a set-up is ultimately a denial of the complexity of any given classroom situation, a shutting down of the imagination. Considering that Lake (Citation2015) tells us that imagination “emerges out of union of inward personal meaning and the external world” (p. 128), this fixed-in-place aesthetic is also a shutting down of personalizing meaning within the classroom. Here’s the kicker that the hag and Lee reveal, then: true sovereignty in the classroom is a matter of giving over to possibility, of embracing the ugliness of the unknown and allowing complex, monstrous situations to reveal themselves as they are and further allowing them to tear down whatever illusions of control we believe we have.

Stories that evoke the character of Dame Ragnell share some very similar themes, but complicate the notion of sovereignty even further. In the medieval text The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnell, Gawain and King Arthur must find the answer to the riddle “What is it women most desire,” to avoid Arthur’s beheading. Gawain and Arthur each quest for the answer, and Arthur eventually comes upon Dame Ragnell, a hag who claims she has the answer to his riddle, which she will reveal under one condition: she must be allowed to wed Gawain, and to do so publicly. While Arthur is loath to let his friend take on such a horrid burden, Gawain accepts, and Ragnell reveals that what women most desire is sovereignty. Nice answer, but this is not the end. Ragnell is not always a hag. In fact, she reveals to Gawain that she is cursed to spend half of her days as a hag and half of her days as her actual beautiful self. After this revelation, she gives Gawain a choice: should she be beautiful in the day and ugly at night, or beautiful at night and ugly during the day. The former would create a situation wherein Gawain could have a beauty on his arm at court and earn public praise, but be faced with sleeping next to and making love with her haggish form. In the latter case, Gawain could sleep next to and make love with the beautiful Ragnell in private, but be the butt of public jokes in having a hag on his arm at court. As it turns out, Gawain suggests that she make the decision herself, and doing so breaks the curse altogether. If Gawain had made the choice, he would have denied her the one thing that, according to the tale, women actually want: sovereignty. Since he gave her sovereignty in this situation that really had more to do with her life than his, she was freed.

So, there’s sovereignty and there’s sovereignty. The notion of sovereignty that we get from the tale of Niall is that it is ugly, but that the ugliness of being a ruler must be faced and embraced if we are to experience any beauty at all. With Ragnell, however, we must not only accept the ugliness of sovereignty, but be willing to extend sovereignty to others and allow them to make their own choices, not ruling over them but partnering with them as they make decisions for themselves.

To this point, we have dealt with characters who have either shrunk away from ugliness, like Niall’s companions and King Arthur, or who have accepted the challenge that ugliness presents. These are not the only responses to ugliness, however. Often, we respond to ugliness with violence. Henderson (Citation2015) tells us that although ugliness through deformity was a sign of divinity in many areas before the Greco-Roman era, by the classical period, ugliness of body, through notions of physiognomy, became equated to ugliness of spirit, suggesting that those who were deformed were made so as a mark of their inherent evil (Citation2015). Further, Eco (Citation2011) writes that “in most cases the many victims of the stake were accused of witchcraft because they were ugly. And, with regard to this ugliness, some people even imagined that during their hellish Sabbats they were able to transform themselves into attractive creatures” (p. 212). Here again we have the trope of ugly creatures, through the use of spells, magically becoming beautiful, but what is important for our current discussion is the violence that ugliness begets. With this in mind, and if ugliness “has long posed a challenge to aesthetics and taste, […] complicating questions about the human condition and the wider world in which we live and interact” (Henderson, Citation2015, p. 9), it makes sense that those who want to live in a world devoid of spiritual filth would want to destroy the physically ugly.

This thinking, however, is fantastical, a delusion, and allows us to see the very human ugliness that arises from that which makes us uncomfortable. That is, an ugly response to perceived ugliness does little more than add to the pile. Further, the relation may not be so simple. Eco (Citation2007) clarifies for us that whereas beauty is finite and limited in its scope, ugliness is infinite “like God.” Not only does such an understanding of ugliness render the concept unfathomable in itself, it also makes ugliness an infinite possibility for us. If ugliness is infinite, then ugliness always risks becoming our possibility. Destroying the ugliness before us then, is essentially destroying the reminders of our own possible ugliness, physical and spiritual.

Perceived ugliness can inspire us to do more than just destroy it, however. There are the occasional instances where it can also drive us toward destruction in general. Consider the debut of Stravinsky’s (Citation1913/1989) ballet The Rite of Spring. When the Ballet Russes premiered the piece in Paris, an all-out riot ensued. While descriptions of the debacle vary, and, with descriptions of audience members drumming out rhythms on other members’ bald heads and sword fighting with canes, tend toward the cartoonish, it is clear that there was an upheaval in the theatre due to either (a) the consistent musical dissonance, (b) the downright clunkiness of the dance, or (c) a strange combination of the two. According to Hewitt (Citation2013), who quotes one critic of the time as having written that the “music always goes to the note next to the one you expect” (para. 8), it was more than likely that the dissonance was the true key to the outrage.

One interesting thing to note here is that the performance was completed. Despite the disruptions, the ballet ran without halt from the “almost strangled bassoon melody” (Hewitt, Citation2013, para. 7) that begins the work to its catastrophic end that reveals a certain mechanical quality to so many human rituals. However much violence the piece may have inspired, the music itself was not stamped out. This suggests a muddier relationship between ugliness and destruction than has been discussed up to now. While physical ugliness can drive us to attack the offending person or object directly so as to be done with it, aural ugliness, which requires a different type of perception and set of associations, can inspire a whole new level of ruination. Whereas the prospect always exists for projecting the possibility of physical ugliness onto ourselves, we can never be an ugly sound, we can only experience them. It appears that this sort of ugly experience, removed ever so slightly from what we can point directly at (for pointing at the violinist is not pointing at the music he is making any more than pointing at the notes on the score is) can drive us toward whatever it is that we can get our hands on, just to have done with something.

5. Skeletons in the closet: ugly emotions

The classroom is a strange place. Try as we might, the classroom situation is always manufactured. The students who come into our rooms and sit in the desks that we’ve arranged and participate in the activities and discussions that we’ve prepared for them do not do these things naturally. While each student may know some of their classmates, they ultimately did not group themselves. Nor did they (often, anyway) choose to be on our rosters. Yet there they are, with all of their intellectual and emotional strengths and baggage, trying to gain what they can from what we have to offer them. Such a situation often creates space for emotions and thoughts that we cannot quite name, or that are ambiguous in nature. These are the emotions that Ngai (Citation2005) calls “ugly feelings.” While we may commonly associate violent urges with ugliness of emotion, Ngai argues that the clarity of these feelings set them into a different category, and that it is the feelings that are less definite in their nature that are truly ugly, largely through their lack of tangible form. While there is a case to be made for both sides of this, let us begin with Ngai’s thought. From there, we will move beyond feelings (which may arise arbitrarily) to thought, which is, all things considered, more purposeful.

6. Ugly feelings

One of the feelings that Ngai describes as ugly is anxiety. Anxiety’s ugliness stems from its lack of a concrete object and its projected nature into possible futurity. It is a weird space that consistently imagines harmful futures for particular areas that can often stop us in our tracks.Footnote3 Ngai writes that anxiety is characterized by less “an inner reality which can be subsequently externalized than as a structural effect of spatialization in general” (Citation2005, p. 212). Places, and the possible futures that we project onto them, evoke anxiety, and the classroom is no different. Whitehead (Citation1929) speaks of just this sort of curricular anxiety in stating that the England of his day was unsure whether to produce amateurs with generalized knowledge or experts with specialized knowledge. Whitehead’s answer, of course, was that the issue is much muddier, and that curricula must be developed by those who are directly involved in their implementation for those who will most directly benefit; quite an anxiety-driving task of itself when one does not feel free to create. Still, perhaps it is better to be anxious about how to create a thing than to have anxiety over what to create in the first place.

While anxiety has its foundation in uncertainty and imagined possibility, the ground for anxiety in the twenty-first century classroom is, ironically, beyond sturdy, for both students and for teachers. Beyond the simple idea that we’re herded into rooms with people we do not (at first) know, many of whom we do not trust, the constant monitoring of students by teachers and administrators (and let’s not forget the policing that students do of each other), as well as that of teachers by administrators, the state, students, and parents, create the possibility of schools being bona fide anxiety factories. Every new person thrown into the mix re-places a place, creating new possible sources of anxiety.

What’s more is that while we look to technology to help us create new bonds and connect with our world in meaningful new ways, Dimitriadis (Citation2015) informs us that reform efforts toward incorporating technology into curricula to meet the needs of a changing world economy “underscore a deeper anxiety about how the world is changing and how our educations systems fit into this evolving landscape” (p. 135). In an odd way, then, the anxiety about ensuring that American students will be ready to meet the demands of the increasingly digital world drives curriculum reforms that do little more than rechannel anxieties.

This anxiety is, of course, not only limited to the classroom. Issues of identity, particularly cultural identity, can be a major source of anxiety. When one’s culture has been a grounding entity for how one defines oneself, slowly encroaching globalization and the muddying, sterilization, and nullification of cultures can be a destabilizing force. Again, Dimitriadis tells us that popular culture today “can only be understood against the backdrop of the massive social and technological shifts associated with ‘globalization’” (Citation2015, p. 136). This is problematic when we consider that, largely, individuals base their identities on those things with which they can connect and identify, and that pop culture offers a very limited, tailored set of identities from which to choose. In this way, a globalized identity threatens to flatten the categories with which an individual can identify, marginalizing those categories and, to an extent, uglifying them when they do not mix individual authenticity with a globalized identity. When the ugly becomes, as we have seen, that which we must be rid of, what we may authentically identify with often becomes the thing we must purge from our world, doubly creating plastic identities and ugly inner lifeworlds.

The question becomes, which of these uglies, if either, is acceptable, the one to be embraced? With this question in mind, it must be said that one large part of educating is building an environment of trust wherein students can explore their own ugly feelings with the instructor and with each other. The twenty-first century educator must explore not only ideas and projections of students’ possible beauty, but also the avenues of ugliness that they must travel. This is a narrow path, indeed. Thacker (Citation2016) writes that the “mourning voice of Greek tragedy constantly threatens to dissolve song into wailing, music into moaning, and the voice into a primordial, disarticulate anti-music” (p. 24). Standing upon the backbone of tragedy, we must ever be alert to the dissolution of our songs. Given such a situation, it would seem that we would be better served by letting ugliness lie beneath the metaphorical rug, and yet to do so would rob any experience of its authenticity. On this note, Pop (Citation2014) questions whether beauty and ugliness can coexist, and, utilizing an argument of degrees and comparison, concludes that the two are ultimately co-dependent. While some of Pop’s methodology and reasoning is a bit dubious (his claim, for example, that “to be beautiful means ‘to be lovelier than’ and to be ugly ‘to be less lovely than’” (p. 175), have little ground, for one can experience an instance of beauty or ugliness without necessarily having any experience with which to compare it), the notion that the two consistently intermingle within an individual’s experience, informing those experiences from behind the scenes, is hardly refutable.

Finally, and briefly, I wish to discuss that emotion that makes itself so readily available in the classroom: shame. Shame, Henderson (Citation2015) tells us, “suggests another kind of ugliness, akin to emotional ‘dirt’ (in the sense of ‘matter out of place’) that soils the soul” (p. 41). Shame arises when we feel as if we’ve felt or done and internalized something that “doesn’t belong,” a feeling that develops, ultimately, from having unrealistic ideas about what others actually feel and experience themselves. In the song “Delicate Cycle” (Bavitz & Dawson, Citation2013) by the Anti-folk/Hip-Hop duo The Uncluded, Kimya Dawson sings about growing up working in a laundromat that her father ran. She goes on to tell us that the first time she lived in a house with a washer and dryer at the age of 26 was the “year [she] bottomed out,” speculating that it was the lack of “community that comes from/hauling your big old load out in public and airing your dirty laundry” that caused her life to fall apart. Her bottoming-out derived from no longer being part of a community that aired its dirty, sweat-stained undies and smelly socks. Shame, the argument goes, disappears in communities where people openly share these simple, if unpleasant, secrets.

The classroom should be no different. When we can openly share our successes (teachers especially) then we create a ground where possible failure does not have to be completely stultifying. It is on this type of ground that students actually feel free to take intellectual risks and not feel isolated from their peers through the shame they could possibly feel if they are unsuccessful. The emotional filth of shame gets a thorough wash and rinse when communal ugliness gets pulled from the bottom of the hamper.

7. Ugly thoughts

Of course, no exploration of mental ugliness would be complete without consideration of that ugliest of philosophies, pessimism, with its embrace of doom and gloom. These terms deserve some discussion in their own right. Thacker (Citation2016) explains that what comes out of an understanding that all things will end (doom) is “a sense of the unhuman as an attractor, a horizon towards which the human is fatally drawn” (p. 20). Gloom, however, doom’s atmospheric counterpoint, in its “austerity of stillness,” instead of facing us with our inevitable demise, rather becomes “the horror of a hovering stasis that is life” (p. 21). In other words, either way we shake it, everything runs the risk of being terrible. Of course, it’s not quite so simple. Paradoxically, then, it appears that ugliness and monstrosity can become analeptics for those who would stave off the gloominess of a stagnant existence. Let us work backward here. The gloomy individual, in her melancholy stasis, sees no end, is trapped in an infinite nothingness of the now. A mild injection of doom into this sort of pessimism, however, allows for a new sort of authenticity of Being, as it provides a sort of telos or towards which for the individual (Heidegger, Citation1926/1962). Instead of drifting upon a stagnant sea, we instead rush toward the gaping mouth of the Kharybdis. Could it be, then, that a doom-focused pessimism is actually a sort of cloaked optimism? Is an ugliness of thought that embraces our inherent demise preferable to an ugliness of thought that sees no possibility? Perhaps my desire to answer “yes” is simply more evidence that the “notion of an American pessimism is an oxymoron” (Thacker, Citation2016, p. 54).

It is in light of this understanding of ugliness that Asger Jorn’s proposition that “an era without ugliness would be an era without progress” (quoted in Henderson, Citation2015, p. 14) is most pertinent. The dulling ugliness of gloom, that is, can still be shaken up, interrupted by the ugliness of impending doom. Whereas gloominess acts as its own analgesic, perpetuating a cycle of endless nothingness, doom promises an end, and ends require motion. With that in mind, teleological destruction still lays the pathway for progress, for motion forward, however ugly the thing toward which we are moving may be.

8. Toward an ugly curriculum

The immediately preceding discussion, is, of course, a new imagination of the absurdist existentialist dilemma. If everything is certain to crumble, does anything ever really change? The works we think we are developing today will be forgotten a 1000 years from now, and that’s always been the case. Does, then, the meaning we posit into our activities and experiences valid? Whereas gloom would issue a resounding “of course not,” the idea of doom breaks this up with a less confident “maybe.” If life is absurd anyway, better to let anxiety-riddled projections toward the future go. As Camus (Citation1955/1983) has written, “Each atom of [Sisyphus’s] stone, each mineral flake of that night filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart” (p. 123). It is in the midst of this strange chasm that we may continue onward to consider what an ugly curriculum would look like. Considering all of the above, it is perhaps the idea of asymmetry through which we can most clearly accomplish this.

9. Ugliness as asymmetry

In the song “Hang Ten” by the Hip Hop duo Hail Mary Mallon, Rob Sonic raps briefly about his outfit. ““Boat shoes, gold tooth, fanny packs,” he begins, closing out the rhyme with the fact that he’s “in some fancy pants and a Stussy hat/just because [he’s] motherfuckin’ bringin’ ugly back” (Bavitz & Smith, Citation2014, Track 7). Such an awkward assemblage—a little of this, a little of that—hints at a collage-like aesthetic, lacking balance or completion, borrowing from a random collection of styles that has no ground beyond that of the particular individual. Consider here Rosenkranz’s (Citation1853/2015) ideas that the “abstract fundamental definition of all beauty is […] unity,” and that the “opposite of unity as abstract disunity would thus be the absence of an outward limit or interior differentiation” (pp. 63, 64). For Rosenkranz, beauty needs form, and that form should have some semblance of symmetry, wherein every part has a relation to every other part, but is distinguished from them in such a way as to not only counterbalance them, but also to be worthy of contemplation in itself. Random assemblages of objects miss the mark here.

The ugliness of asymmetry is not limited to obvious and outward physicality. There can also be asymmetries between ideologies and their realities. For example, Henderson (Citation2015) reminds us that the “‘beauty’ of Chinese foot-binding and Victorian corsets crippled or caused broken bones, while the art of ballet turned a woman’s body into a ‘deformed skeleton’ according to the mother of modern dance, Isadora Duncan” (pp. 16–17). To better illustrate this point, I would like to share one image from Jo Farrell’s (Citation2014) “Living history project.” This image (Figure ) is a photograph of the feet of a woman Farrell identifies as Yange Jinge. Jinge, now aged many years, had her feet bound as a young girl. The following is the result of this binding in all of its horrific splendor.

What we must consider is that this deformation of the feet would have occurred when Jinge was still very, very young. Here, then, we see quite plainly the barbarity that so-called beauty can mask, for surely these feet were not intended to be seen out of stockings or shoes. The ugliness here is not even so much of the physical makeup of the feet themselves, but rather in the violence that we must understand that it took to create these feet. The ugliness, that is, occurs in the theoretical asymmetry of achieving apparent beauty (as well as the loveliness that said beauty is supposed to represent) and the physical means of achieving it.

Often, I challenge my students to imagine how they would behave in situations such as whether they would go along with a discriminatory law or what choice they would make if faced with the infamous trolley problem. Regarding the former, students tend to state that they would not go along with such a law, though many admit that while they would not want to, they probably would if it came down to having to suffer some sort of penalty. Regarding the trolley problem, students tend to try to skirt the problem, replacing the parameters of the thought experiment with their own terms that soften the choices they are required to make. When conferencing with students about these experiments and bringing attention to the fact that they try to change the rules, students often respond with something like, “I don’t want to have to make that kind of decision.” It’s not a bad response, really. Who would? This, however, is why imagination is important. Eisner (Citation2002) tells us that imagination “gives us images of the possible that provide a platform for seeing the actual, and by seeing the actual freshly, we can do something about creating what lies beyond it” (p. 4). That is, while we may not want to be faced with ugly decisions, and while we may be of several minds about making them, imagination allows a glimpse into our psyches so that we can work toward mending the imbalance between the selves we desire to be in our minds and the selves that we present to the world through our words and actions.

10. Ugly connections

Eisner (Citation2002) tells us that aesthetic experience “is potential in any encounter an individual has with the world. One very important aim of arts education is to help students recognize that fact and to acquire an ability to frame virtually any aspect of the world aesthetically” (p. 232), as well as the fact that the arts “liberate us from the literal; they enable us to step into the shoes of others and to experience vicariously what we have not experienced directly” (p. 10). What arts education does for us, then, is open for us not only our own possibilities, but the possibilities of others. This may not always be a welcome experience, though.

It is important to note that, according to Simpson (Citation2014), for psychological and philosophical theorist Theodor Lipps, an originator of theories concerning Einfuhlung (empathy), empathy was “not a sensation in one’s [own] body, but feeling something, namely, oneself, into the [a]esthetic object” (p. 123). We write our lives onto the objects with which we share moments of empathy, but this projection is not limited to objects, as it is possible “in all intersubjective encounters” (p. 123). Every moment is a possible gateway into shared feeling, and every moment of shared feeling is a ground for aesthetic experience. This is important to our current discussion because Simpson (Citation2014) carries the argument forward, reasoning that since positive Einfuhlung was a “harmonious feeling of love, freedom, and confidence in the face of a beautiful person, object, or work of art [… and in] such a context, ugliness and negative empathy threaten not only the aesthetic participant, but the optimism of Eihfuhlung theory itself” (p. 127). Here is the idea. When we have an aesthetic encounter, a sort of identification with the aesthetic object occurs. When that encounter causes us pain (negative feeling) we believe the object ugly and reject it. Empathy, it appears, is quite a loaded gun. On the one hand, we want to connect with others, to feel along with them, to open ourselves up to their pain. On the other hand, though, experiencing that pain can turn us off from being empathetic because… well… it hurts. Since such is the case, the educator who would invite his students toward authentic empathy must not delude himself into a sunshine and rainbows, fluffy version of the emotion, but rather see it and respect it for the bundle of ugliness that it can be.

While this section is largely predicated upon ideas that come from Eisner, we must keep in mind that Eisner’s main focus is on arts education. However, there is no reason why Eisner’s ideas cannot be applied to any sort of education. That is to say, it is not out of the question to wonder why a Social Studies or English or even a Mathematics curriculum could not be tailored toward realizing and embracing aesthetic experience. If we are to be transparent in our delivery of history, could we not invite our students to feel along with historical monsters? Would English teachers do their students a disservice in asking them to develop relationships with fictitious villains and to see them as real possibilities for humanity? Or how about this: H.P. Lovecraft is rather famous for creating nightmarish landscapes wherein the geometry is simply wrong, considering the Euclydian understanding we currently have of that branch of mathematics. Graham Harman (Citation2012) writes that nothing is more Lovecraftian than his repeated vague assaults on the assumptions of normal three-dimensional space and its interrelations, as learned by students since ancient Greece. For this reason, nothing could be more threatening than the notion that something is ‘all wrong’ in the presumed spatial contours on which all human thought and action is based. (p. 71).

Suppose a Geometry teacher actually incorporated Lovecraft’s (Citation1926/2014) “The call of Cthulhu” into her curriculum simply for the sake of having her students empathize with the anxiety derived from the vagueness, the wrongness, the weirdness the characters experience in discovering a place in our world where the geometry is not of our world. Are we treading dangerous waters by even mentioning this as a possibility?

All of this is to say that while it is “inclinations toward satisfaction and exploration that enlightened educators and parents wish to sustain rather than to have dry up under the relentless impact of ‘serious’ academic schooling” (Eisner, Citation2002, p. 5), there is no real reason why the two have to be mutually exclusive. We can have “serious” academic schooling that invites a sense of playfulness… provided we are prepared to deal with the ugly, messy thoughts and emotions that come from blending them.

11. Conclusion

The Greek myth of Orchis tells the tale of the son of a satyr and a nymph who attempts to take sexual advantage a high priestess during a Bacchanal (which would hardly be out of the ordinary, considering the highly sexually-charged nature of the festival) and ends up getting torn to pieces by wild beasts. The cause of his dismemberment is more to do with the sacrilege of attempting to take a priestess, who is to remain sexually “pure,” than with the attempted rape itself (on this, we should keep in mind that for the Greeks, nymphs and satyrs were very much sexual beings, having little understanding or regard for human mores regarding sex and purity, seeking only pleasure and frivolity). Orchis’s mother pleads with the gods to restore him, and they did… as a flower, the orchid. Beautiful ending, right? Eh. Not so much.

The character Jonathan in the film Decay (Haskins, Huling, and Wartnerchaney, Citation2015), troubles over the gods’ decision to re-incorporate Orchis in this manner. While his unnamed imaginary neighbor attempts to convince him that Orchis ends up being eternally beautiful, Jonathan, having lost his mother to her own psychosis early in his life, protests, obsessed with the idea of rot. Whatever beauty Orchis may have, he argues, comes from nothing but layers of rotting wood. Jonathan has reversed the popular notion of finding beauty in ugliness to uncovering the ugliness, the rot, the decay that fuel the beautiful. This aesthetic flip is beyond important. While it is popular and commendable to seek the beautiful in ugliness, to deny that beauty grows out of ugliness is to deny a full understanding of the experience of beauty.

Regarding curriculum, and most particularly the curricula that students who sit in desks organized by teachers who have been told what subject matter is most important to relay to their pupils and the best practices for doing so, these sorts of experiences seem almost moot. While the roots from which we derive our modern term “ugly” originally denoted what was to be feared or dreaded, newer conceptions of the term allow us to see the world from different angles, troubling ideas about what we are to fear and what we simply deem not worthy of our time (Henderson, Citation2015). Whether it is the case that we must do away with what we fear (ugliness and its possibility for us), or the ugly is just that which we do not want to talk about because it is not apparently worth our time, completely ignoring the ugly flattens our world, stripping the beautiful of whatever differentiating value it may have had. If we look toward what it means for an education to be standardized and anaesthetized, stripped of local flavor and the daily needs of particular students in particular classrooms, we can easily see that what was once intended to create a complex ground by which students could understand and participate in beauty becomes little more than polished linoleum. In a not-dissimilar way, curricula that tend toward so-called positive experiences and understandings of history (i.e., those that do not allow for the “ugly realities” of life) are much more in vogue than those that dig into the out-of-place dirt, the decaying historical wood, and the very ugliness of our being, making beauty an inauthentic commonplace, awaiting interruption. When such is the case, perhaps a healthy dose of ugliness is just the thing to wake us up.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

James Grant

James Grant is a doctoral student in the Curriculum Studies at Georgia Southern University in Statesboro, GA, USA, where his primary interests are cultural and media studies within the context of curriculum. The work presented here is an extension of this interest, particularly in regard to aesthetics in horror films and texts and how these aesthetics translate to the twenty-first century classroom. He has been an educator since 2009, and has worked at the middle- and high-school levels in private and public institutions. He currently teaches 9th grade composition and AP language, and Film Studies at Grovetown High School in Grovetown, Georgia.

Notes

1. I should note here that readers need to be conscientious about what occurs in a meditation, as there will be some who demand an insight into my “approach” for the term. To those readers, I will give a nod to the Zen koan wherein a student trying to meditate becomes frustrated with his master, who makes incessant noise during the student’s meditations. The student says to the master, “Can’t you see I’m trying to meditate?” To this, the master remarks on the young student’s foolishness, reprimanding him with the question, “How can you try to meditate?!” There is no algebra of meditation, it occurs organically, and so this exploration will be a bricolage of sorts, allowing thoughts to emerge and be explored as they are relevant to the discussion.

2. I should also note that some readers, at this point, will begin to complain that I’m being unclear about what I mean by “ugly” and “ugliness,” requesting that I provide some sort of hardline definition and framework for the terms. Too bad. Such a mindset completely misses the point here, and begs that I perpetrate a performative contradiction, in that such an undertaking would seek to tidy up something that is messy, to sanitize the ugly.

3. Readers may here wonder something to the effect of, “but are there other interpretations of ‘ugly emotions’?” There probably are, just as there are multiple interpretations of just about everything. Ngai, however, presents an astute and focused study on the matter, and so holding on to her theories should be just fine for our purposes.

References

- Bavitz, I., & Dawson, K. (2013). Delicate cycle. [Recorded by The Uncluded]. On Hokey Fright [LP]. Minneapolis, MN: Rhymesayers Entertainment.

- Bavitz, I., & Smith, R. (2014). Hang ten. [Recorded by Hail Mary Mallon]. On Bestiary [CD]. Minneapolis, MN: Rhymesayers Entertainment.

- Camus, A. (1983). The myth of Sisyphus and other essays. J. O’Brien (Trans.). New York, NY: Vintage International.

- Dimitriadis, G. (2015). Popular culture as subject matter. In M. F. He, B. D. Schultz, & W. H. Schubert (Eds.), The SAGE guide to curriculum in education (pp. 134–141). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Douglas, N. (2014). It’s supposed to look like shit: The internet ugly aesthetic. Journal of Visual Culture, 13(3), 314–339. doi:10.1177/1470412914544516

- Eco, U. (2007, December 14). On the history of ugliness [video file]. Retrieved from http://videolectures.net/cd07_eco_thu/?q=umberto%20eco

- Eco, U. (2011). On ugliness. New York, NY: Rizzoli.

- Eisner, E. (2002). The arts and the creation of mind. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Esch, M. S. (2010). Rearticulating ugliness, repurposing content. Ugly Betty Finds the Beauty in Ugly. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 34(2), 168–183. doi:10.1177/0196859909351743

- Farrell, J. (2014). Yange Jinge detail [digital photograph]. Retrieved from http://www.livinghistory.photography/images.html

- Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts, and social change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Harman, G. (2012). Weird realism: Lovecraft and philosophy. Alresford, UK: Zero Books.

- Haskins, M., & Huling, C. (Producers) & Wartnerchaney, J. (Director). (2015). Decay [motion picture]. USA: Ghost Orchid Films.

- Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and time. J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson (Trans.). San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco. Original work published 1926.

- Henderson, G. E. (2015). Ugliness: A cultural history. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Hewett, I. (2013, May 16). The rite of spring 1913: Why did it provoke a riot? The Telegraph. Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/classicalmusic/10061574/The-Rite-of-Spring-1913-Why-did-it-provoke-a-riot.html

- IMDb. (2016). Ugly betty. Retrieved August 30, 2016, from http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0805669/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1

- Lake, R. (2015). Curriculum imagination as subject matter. In M. F. He, B. D. Schultz, & W. H. Schubert (Eds.), The SAGE guide to curriculum in education (pp. 127–133). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Language Log. (2010, December 16). Humanities research with the Google books corpus. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=2847

- Lee, D. (1991). Diane’s voice. In L.M. Berman, F.H. Hultgren, D. Lee, M.S. Rivkin, J.A. Roderick, & T. Aoki (contributors), Toward curriculum for being: Voices of educators. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- Lovecraft, H. P. (2014). The call of Cthulhu. In Milton Creek Editorial Services (Eds.), The complete fiction of H.P. Lovecraft (pp. 381–407). New York, NY: Quarto Knows. Original work published 1926.

- Morris, M. (2016). Curriculum studies guidebooks (Vol. 2). New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Ngai, S. (2005). Ugly feelings. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Plato. (n.d.). Parmenides. B. Jowett (Trans.). Retrieved from http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/parmenides.html

- Pop, A. (2014). Can beauty and ugliness coexist? In A. Pop & M. Widrich (Eds.), Ugliness: The non-beautiful in art and theory (pp. 165–179). London, UK: I.B. Tauris & Co, Ltd.

- Rosenkranz, K. (2015). Aesthetics of ugliness: A critical edition. A. Pop & M. Widrich (Trans.). London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic. Original work published 1853.

- Schubert, W. H. (1991). Philosophical inquiry: The speculative essay. In E. C. Short (Ed.), Forms of curriculum inquiry (pp. 61–76). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Shakespeare, W. (1600). Hamlet. Austin, TX: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Simpson, K. (2014). I’m ugly because you hate me: Ugliness and negative empathy in Oskar Kokoschka’s early self-portraiture. In A. Pop & M. Widrich (Eds.), Ugliness: The non-beautiful in art and theory (pp. 122–140). London, UK: I.B. Tauris & Co, Ltd.

- Stravinsky, I. (1989). The rite of spring. Mineola, NY: Dover. (Original work published 1913).

- Thacker, E. (2016). Cosmic pessimism. Minneapolis, MN: Univocal.

- Vallance, E. (1991). Aesthetic inquiry: Art criticism. In E. C. Short (Ed.), Forms of curriculum inquiry (pp. 155–172). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Whitehead, A. N. (1929). The aims of education. In The aims of education (Chapter One). Retrieved from http://www.anthonyflood.com/whiteheadeducation.htm