Abstract

Today, the inclusion of special needs children into preschool classes is fully expected; however, the logistics and best practices for ensuring the success of inclusive classrooms are not fully understood by educators. The goal of this study was to address this lack of understanding among educators. This study used a narrative, phenomenological method to explore in-depth preschool teachers’ experiences and perspectives on preschool inclusion. Eight general education preschool teachers from the author’s school district in southeastern Virginia were interviewed using an open-ended interview format.

The major themes that emerged from these interviews included the general need for a better understanding of the role preschool teachers perform in the educational environment. The participants shared with the researcher that many parents and others outside of the school environment consider preschool teachers as little more than babysitters. Another theme that emerged was that more training is needed, both formal and on-the-job training, in the area of inclusion practices, as this would increase the comfort level of preschool teachers with these practices. Additional themes revealed that the attitudes of both teachers and outsiders also impact the effectiveness of preschool inclusion practices, and all of the participants reported having positive attitudes about teaching in an inclusive environment. The information obtained in this study provides us with a better understanding of preschool teachers’ experiences and perspectives about preschool inclusion. It also provides insight into what teachers may need to improve preschool inclusion.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Preschool inclusion practices are becoming increasingly widespread throughout the United States. With these practices, special needs children (e.g., children with learning disabilities or those on the autism spectrum) are integrated into the normal classroom. However, although inclusion may be expected, it is often not fully understood by educators. Providing teachers and other stakeholders (e.g., parents, school administrators, children) with appropriate knowledge and training is key to ensuring that inclusion practices are successful. This study explored teachers’ reflections and perspectives on their experience with preschool inclusion. The information obtained in this study illuminates our understanding of what is needed to ensure the success of preschool inclusion. The themes that emerged from this study will help educators provide appropriate staff development opportunities to improve the quality of inclusion practices.

1. Introduction

Many researchers have offered opinions about what inclusion practices offer children with special needs, as well as the complexity of integrating these children with children without special needs (Hall & Niemeyer, Citation2000; Norwich & Nash, Citation2011; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Citation2015). The intent of inclusion practices is to give children with special needs a sense of belonging and to also provide them with more choices with respect to education and participating with the other children (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Citation2015).

The Individual Disabilities Act (IDEA) of 1990 paved the way for students with special needs to receive a free and appropriate education (FAPE). With this act, the federal legislation mandated an inclusive educational environment for all students, and public school educators were charged with the primary responsibility to provide equal opportunities for students, regardless of their level of functioning (Banerjee, Lawrence, & Smith, Citation2016). Since 1990, inclusive educational environments have been increasing throughout the United States in response to the legislative mandates of IDEA and FAPE. However, teachers have not been adequately trained to work in inclusive environments (Piper, Citation2007). According to Efthymiou and Kington (Citation2017), even though inclusive practices have been mandated, the implementation of these guideline are determined, to a significant degree, by school agendas and social and local conceptualizations of the government guidelines, which may vary from school to school and region to region.

Further, teacher attitudes have a major impact on the success of inclusion practices, as their attitudes directly influence instruction in the classroom (Kwon, Hong, & Jeon, Citation2017). Personnel and specialists in preschool settings have indicated that these teacher attitudes toward inclusion within the classroom are largely dependent upon the availability of a number of factors and support services (Keaney, Citation2012), including access to paraprofessionals, provision of professional development, as well as preparation and collaborative planning time and controllable classroom sizes. Keaney (Citation2012) also highlighted that when teachers hold a positive attitude toward inclusion, there is a much greater probability for success for all children in the classroom. When the resources are not available and the training not provided, regular education teachers have not always been positive about their experience in inclusive classrooms (Gaines & Barnes, Citation2017).

Teacher training in general is important for the success of the students. As noted above, many teachers have not been appropriately trained for the inclusion process with students with disabilities in the preschool setting (Ignatovitch & Smantser, Citation2015). In addition to a lack of teacher training, teacher opposition to the inclusion process can prove difficult to overcome in the educational environment (Casale-Giannola, Citation2011). Not surprising, lack of teacher preparation also negatively influences teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion (DeMonte, Citation2013; Gaines & Barnes, Citation2017; Ignatovitch & Smantser, Citation2015; Keaney, Citation2012; Kwon et al., Citation2017; Mitchell & Hegde, Citation2007; Stein & Stein, Citation2016; Yang & Rusli, Citation2012).

The purpose of this study was to explore the experience and perceptions of general education preschool teachers about the inclusion of students with disabilities into the regular classroom. A phenomenological, qualitative approach using open-ended and semi-structured interviews was chosen because this approach is most suited for exploring participants’ experiences in the context in which the experience occurred (Eddles-Hirsch, Citation2015). Using this qualitative approach, the analysis of the interviews uncovers common themes that would then indicate future areas of study.

The research question that guided this study was: How do the general education preschool teachers feel about and experience the inclusion of students with disabilities into the regular classroom? The research question for this study focused on the gap in the research; that although it is ultimately the role of the teacher to carry out the inclusion mandate, not enough attention has been given in the literature to how general education preschool teachers feel about and experience the inclusion of students with disabilities into the regular classroom.

2. Methods

A qualitative research approach with a phenomenological design was used to explore the experiences and perspectives of general education preschool teachers with the inclusion of students with disabilities into the regular classroom. The participants included eight general education preschool teachers who were interviewed using an open-ended interview format. The insight gathered from these interviews allowed this researcher to provide recommendations for inclusion practices for preschool-aged children.

A phenomenological design was used for this study as this type of research analyzes perceived or experienced phenomena (Flynn & Korcuska, Citation2018), which for this study was preschool inclusion. Giorgi (Citation2010) referred to phenomenology as the study of a specific subject, and further, Giorgi (Citation2012) asserted that descriptive means involve the use of language to communicate the intentional objects of participation. Phenomenological research is based on general systems theory, which was originally developed by von Bertalanffy in 1928. Von Bertalanffy posited that all phenomena contain patterns that create a system and that the common patterns within the system provide greater insight into the phenomenon (Drack, Citation2009). Although researchers may interpret the general systems theory differently, von Bertalanffy (Citation1928/1972) argued that these differences in interpretation lead to a continued healthy development rather than confusion or ambiguity.

The participants in the study consisted of eight general education preschool teachers who taught in a public preschool in a school district in Southeastern Virginia. The participants volunteered and received no reward, and further, they were made aware of other participants in the study. The participants were interviewed during the academic school year because their experiences would be clearer and more accessible than they might if they were interviewed over the summer break.

Prior to the interviews, the interview questions were used in a pilot study to determine their appropriateness. For the pilot study, two teachers were interviewed, both of whom signed consent forms and agreed to participate in the study. Their responses confirmed that the questions were on target, and the information obtained helped to determine the feasibility of the study. No adjustments were required of the questions after the conclusion of the pilot study. The two interviews for the pilot study were private and uninterrupted. The pilot study participants were not included in the general study.

The interviews with the eight participants were transcribed verbatim, and notes were taken by the interviewee during the interviews to help in the analysis phase. Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) was implemented to analyze the data looking for common themes across the interviews.

Analysis consisted of reading and rereading each transcript and color coding it, looking for common words and themes. The themes were then compared against the notes and recordings. The same process was completed for each interview in the study. A number of themes emerged.

The next stage of analysis involved the construction of a master list of themes. The themes as a whole developed into a conceptual picture of the teachers’ experiences.

NVivo, which is an analytic software developed by QSR International, was also used to analyze the data. Specifically, this software has also been designed to work with audio and visual material and transcribe written words. The themes produced from using the software reinforced the themes that were discovered during the manual coding process.

A validity assumption was made that each participant provided truthful answers to the questions presented. In order to increase the validity of this study, threats of bias and pre-existing conclusions were minimized. To verify the accuracy and establish generalization of the participants’ responses, the option to provide feedback from participants was given. Although no feedback was given, each participant was offered the chance to review her individual transcript to check for accuracy.

The use of triangulation was employed in the study to provide a multidimensional perspective of the data. Triangulation consisted reviewing the notes taken during the interviews, the transcripts of the interviews, and the coding of different words and themes applied to the transcripts.

3. Results

The goals of the research were to obtain data that would be descriptive and interpretive. The interview questions were used to address the key research question: How do the general education preschool teachers feel about their experiences including students with disabilities into the regular classroom environment? The participants provided a narrative description of their feelings and experience of preschool inclusive practices.

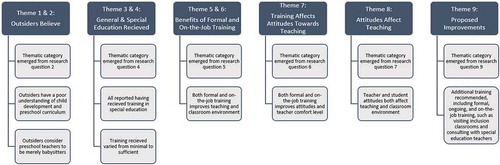

The frequency analysis of emergent themes emerged from leading words of teacher responses (see Appendix A). Themes were determined by the reoccurrence of words and phrases spoken by the participants during the interviews. General themes were determined when five to eight of the participants identified the same theme. Subthemes were indicated when two to three participants identified the same theme. Figure shows the nine themes that emerged from the interviews.

3.1. Themes

During the data analysis, nine themes emerged. The first two themes were that (a) people on the outside tend to think of preschool teachers as babysitters, and (b) they do not understand the developmental level or the curriculum of the preschool environment. The third and the fourth themes concerned training: (c) general and (d) special education. The fifth and sixth themes concerned the benefits of training, both (e) formal and (f) on-the-job. The seventh theme that emerged was that (g) teacher attitudes affect teachers and students in the classroom, and the eighth theme that emerged was that (h) training affects attitude towards teaching. The final theme to emerge was that (i) additional training would be beneficial to the district’s inclusion policies. Each of the themes is discussed below.

3.1.1. Themes 1 and 2: outsiders’ beliefs

Taken together, these themes were endorsed by eight participants: five endorsed theme 1 and three endorsed theme 2.

3.1.1.1. Theme 1: outsiders view preschool teachers as babysitters

The first theme was that people on the outside tend to think of preschool teachers as merely babysitters. The majority of the participants (five) expressed this view. Four of the participants used the term “babysitter” or “babysitting,” and one participant used the term “daycare”:

Some people consider us babysitters because we don’t have SOLs. (P2)

I think from the outside it looks like we’re just babysitting. (P3)

[People don’t understand] “that it’s not just daycare.” (P4)

[People don’t understand] “that we’re not babysitters.” (P5)

I think the hardest thing for people on the outside to understand is that it’s not a babysitting service, it is a school, and it is an education service. (P6)

3.1.1.2. Theme 2: outsiders do not understand the curriculum

The second theme was that people on the outside do not understand the importance of the preschool curriculum. The participants all shared that the preschool teacher’s role is, in fact, very important in preparing children for kindergarten. Preschool essentially is the starting point for a child’s academic success in school. This includes social learning as well as academic learning. This theme was endorsed by three participants:

A person on the outside might not understand the curriculum that’s being used. (P1)

I feel the hardest thing for you to understand may be their developmental level and knowing what a 4-year-old is all about…. [If you understand] what’s appropriate at their development, you’re fine. (P6)

Even some teachers don’t realize the extent of what we’re teaching. They think they play, but most of the time it is we’re learning through play. (P3)

Other participants also discussed the curriculum and the learning that takes place—both standard classroom learning but also emotional learning. Remarked P4, “Some of the kids have never been away from their parents.” P3 commented, “Inside the classroom, you see how much the kids are learning.”

3.1.2. Themes 3 and 4: general preschool and special education training

3.1.2.1. Theme 3: general education received

The participants in the study had a range of postsecondary degrees, including bachelor’s, master’s, and educational specialist. Of note, a teaching degree or endorsement is required to teach in a public preschool setting. None of the participants expressed regret for having chosen the teaching profession.

3.1.2.2. Theme 4: special education received

All participants had received at least one college course in special education or related district training. The one participant who reported having sufficient special education training had taken a full semester of special education classes. Seven of the eight participants reported having received limited special education training. Half of the participants reported that most of their training in special education had been part of professional development. For example, P4 stated that there had recently been a training offered in autism. However, four of the participants, although aware of trainings being offered, stated that they had not participated in any training specific to on special education.

3.1.3. Themes 5 and 6: benefits of training

Half of the participants expressed the opinion that training is beneficial: two mentioned formal training specifically, and two mentioned on-the-job training. The difference in responses to this interview question was remarkable, especially considering that the participants work within the same school district and have access to the same information.

3.1.3.1. Theme 5: formal training is beneficial

Two of the participants, in particular, commented on the benefits of formal training in special education:

[With] a standard amount of training, at least you’re more comfortable working with the students, and because you know the ins and outs, what’s expected, what could be obtained from the children, if trained to teach them. So, I think that would be an important factor of training. (P1)

I think when someone mentions being in an inclusive environment with preschool kids, it sounds like a lot. It sounds like it’s going to be a hard task. But as you go through those trainings, it makes it seem like something that’s a little bit more doable. (P3)

3.1.3.2. Theme 6: on-the-job training is beneficial

Another theme that emerged was the benefit of on-the-job training.

A lot of the [training] has to do with the opportunities that you have within your classroom. You’re going to learn as you go along. (P4)

You’re going to learn as you go along. (P5)

3.1.4. Themes 7 and 8: training affects attitudes and attitudes affect teaching

3.1.4.1. Theme 7: training affects attitudes towards teaching

Seven of the eight participants reported that the amount of training they had received affected their comfort level in the classroom. Their comfort level affected their attitude, and thus, their teaching. All participants reported that teacher attitudes affect their teaching; further, student attitudes also affect the classroom.

With respect to training increasing teachers’ comfort in the classroom, P1 had this to say:

A standard amount of training at least you’re more comfortable working with the students.

Here are some of the comments about having a positive attitude and how it affects the classroom:

They can tell if you accept them; they can tell if you care for them. (P4)

3.1.4.2. Theme 8: attitudes affect teaching

All participants reported having positive attitudes in their current work environment. The participants generally agreed that teachers work best when they are comfortable performing their duties. If they are not comfortable, they will not be as effective as they might otherwise be because their students pick up on their teachers’ comfort level or attitude. Thus, the teacher’s comfort level will essentially translate into the students’ attitudes. This is especially true of preschool-aged students because, developmentally at their age, they are very impressionable and malleable, and they rely on and look up to their teachers. The quotes below reflect the teachers’ beliefs about having a positive attitude in the classroom:

I think a positive attitude has a positive effect on the students in the classroom…. The fact that we are positive about it [special needs], and we are working through and trying to make sure [we] accommodate them, I think that helps them to be more positive about learning and have a better attitude as well. (P2)

Students can tell right away if you are comfortable … with them. They know right away, and sometimes it’s not a good thing because you want them to know that you are sure of yourself and of what you have to offer them. (P1)

I find if I have a positive attitude, the students in the classroom are going to have a positive attitude. (P5)

3.1.5. Theme 9: proposed improvements

It is outside the scope of this qualitative study to determine whether general preschool teachers have received adequate training working with special needs children and working in inclusive classrooms. This warrants additional research. However, all eight participants expressed the opinion that additional training would be beneficial to them:

I would like some refresher courses…. I would like more training. (P1)

I definitely think we need training. (P2)

It would be nice to have more [training] … and have it so that it’s more a continuous education where you’re having something at least once a year or so to update, or once every other year. (P3)

I’m always willing to get into more trainings and learn more about the inclusive classroom. I think that there could be more offered, especially when you’re asked to be put in that position [of teaching in an inclusive classroom]. (P6)

4. Recommendations

Preschool provides a meaningful experience for the children, teacher, and parents. All participants in this study expressed a willingness to work in inclusive environments, and they all had positive attitudes toward teaching in an inclusive environment. Nonetheless, they believe additional training would benefit all stakeholders. All teachers want to be actively involved in the education of their students. For those teachers who work in public schools and participate in preschool inclusive practices, educational leaders need to support these teachers by providing them with adequate training so that they can perform their duties appropriately and with adequate tools and support. Thus, educational leaders should resolve to provide the necessary training and support, and teachers should participate in such trainings whenever they are available to them. Increasing training opportunities will enhance teacher knowledge, which will ultimately affect teacher attitudes toward preschool inclusion.

From this research study, nine themes emerged that provided a framework for this researcher to develop a best practices model for preschool inclusion (see Figure ). This model is based on the three key components identified by the teacher participants. The first component is respect, which will only occur if all stakeholders understand the preschool curriculum and recognize that preschool teachers are not merely babysitters. The second component is adequate training, which teachers need to be able to optimally teach their students and provide a positive classroom atmosphere conducive to learning—not only academically but socially as well. The third component is to have an effective transition plan that would allow teachers to identify the students who would be most suitable to the inclusion classroom.

4.1. The first component: respect

One of the major themes that emerged is that outsiders do not understand the curriculum, and as such, often consider preschool teachers as merely babysitters. Thus, it is important to educate other stakeholders. One of the best ways to do this may be for the school administration to offer a presentation on preschool inclusive practices during a monthly meeting that would be attended by with school administrators, the school board, and the PTA. If outsiders have a better understanding of the scope and importance of the preschool teachers’ jobs, they will inevitably develop greater respect and appreciation for these teachers’ jobs, resulting in greater support, which would enhance teachers’ ability to succeed in their inclusive classrooms.

4.2. The second component: additional training

This is the most significant finding of this study.

All participants believed that training was important, and they all expressed the opinion that additional training would be beneficial. Yet, the majority stated that they had received limited training in special education. Additionally, although all participants had a positive attitude toward teaching, they also expressed their opinions that additional training would further improve their attitudes and the students’ attitudes, which also results in positive outcomes.

Based on the time spent with these eight preschool teachers and personal experience, this researcher would recommend that additional training be provided. Educational leaders within schools should welcome and encourage teachers to participate in various school- and district-based training. If educational leaders emphasize the importance of training and the impact on inclusive practices, preschool teachers will be more likely to become active participants and become more secure in their ability to teach within inclusive settings.

Such training might be offered as part of the college coursework within a bachelor’s degree program in education. Alternatively, the district could incorporate such training in ongoing continuing education courses, workshops, or through staff development trainings. Training teachers often occurs through professional development programs, and according to DeMonte (Citation2013), is the route taken in order to address issues or practices that challenge teachers or to provide information and applications about new approaches in instruction. The school district can provide training for preschool teachers to facilitate a better understanding of special education and inclusive practices. Such instruction should encompass the exceptionalities of children, including children’s various disabilities. Behavior management in the classroom is also indicated. Notably, many general education teachers have only one strategy for achieving class management, whereas special education teachers often use a variety of tactics, including visual strategies, using a timer, or using a token system. Instruction should also include strategies for helping problematic students modify their behavior. Finally, all students in inclusive classrooms should learn about their peers with special education needs (e.g., what is an IEP).

4.3. The third component: transition planning

Children placed in an inclusive classroom should be made with more care. Visitation and consultation with special education teachers would better prepare these teachers for inclusive classrooms. The special education teacher is very knowledgeable about what a child can and cannot do. As such, the preschool teacher would benefit from the knowledge of special education teachers about what is age-appropriate expectations. Also, the special education teacher would benefit from visiting or sitting in on an inclusive classroom. Preschool self-contained teachers should visit the inclusive classroom before making a determination on which students to include in the inclusive classroom. Unfortunately, in the district where this study took place, most of the special education preschool classrooms and the regular preschool classrooms are in different buildings.

Given these three components, respect, adequate training, and a transition plan, preschool inclusive practices would become more standardized. Teachers would have an increased comfort level and a positive attitude toward their preschool inclusion classrooms, which in turn would lead to successful preschool inclusive practices.

5. Limitations

The research study had numerous limitations. The limitations included sample size, coverage of the study, generalizations, and demographic variables of the results. The study had a very small participant group: eight general education preschool teachers who taught in an inclusive environment within a Southeastern Virginia school district that participated in public preschool. The small sample size and purposeful focus of preschool general education teachers within one school district prohibits generalization across other states or among other levels of education.

Demographic variables such as ethnicity were not included. The participants produced similar responses to the interview questions, which can also be seen as a limitation. The results were elicited freely and the teachers who participated did not know who else participated. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the problem, additional research could address a larger sample size across the state of Virginia or within several states in the United States. As noted by a number of researchers (see, for example, Harvey, Yssel, Bauserman, & Merbler, Citation2010; Hsien, Brown, & Bortoli, Citation2009; Kessell, Wingenbach, & Lawver, Citation2009; Odom, Buysse, & Soukakou, Citation2011), many factors, including attitudes, training, experiences of teachers and administrators, can impact the extent to which inclusive practices are implemented and viewed. A comparison across several districts or states with high participation of preschool inclusion could offer a more varied perspective.

6. Future studies

The qualitative phenomenological study established a foundation for future studies regarding how teachers experience and perceive the inclusion of students with disabilities into the regular classroom. In the current study, the majority of teachers reported that they had not received sufficient training in special education, nor were they sufficiently supported by the community and other stakeholders, many of whom had a poor understanding of the preschool curriculum and teacher responsibilities. These results were similar to past studies. However, an additional finding was that the teachers observed that attitudes, both of the teachers and the students, impact the classroom environment and the effectiveness of their teaching.

Additional studies may provide us with a better understanding of preteacher programs, which might indicate additional coursework be provided on special education. Future research emanating from this study could offer leaders, educators, and teachers a range of varying viewpoints of training and supports needed for successful preschool inclusion. The current study provided concrete data based on the teachers’ feelings of working in an inclusion environment rather than the viewpoints of the school system.

Researchers may wish to study schools that have preschool inclusion programs within specific learning communities. In addition, they may wish to interview building principals and lead teachers. In fact, specific training for inclusive practices could be initiated from the building, district, or state level. These suggestions may provide additional support to improve and expand inclusive practices.

7. Conclusion

The findings from this phenomenological study provided insight into teachers’ experiences and perceptions about preschool inclusion. They identified three areas that impede their ability to effectively teach in an inclusive classroom: (a) lack of understanding about their job and therefore respect from outsiders; (b) lack of adequate training working in inclusive classrooms with special needs children; and (c) lack of visitation to other classrooms to be in a position to select the students most appropriate for the inclusive classroom. These observations and themes were used to develop a best practices preschool inclusion model (as illustrated in Figure ). If implemented, all stakeholders will benefit: students, as it will enhance their learning; teachers, as it will enhance their effectiveness and teaching in the classroom; and parents, as their children will be in a more positive and effective school environment. They will learn about each other—those who are able bodied and those challenged with special needs.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jeanice P. Bryant

Jeanice P. Bryant is a special education supervisor at the Newport News School District in southeastern Virginia. This school district is in an urban area that encompasses 69 square miles of land and 51 square miles of water. A population of 29,400 children attend school (53.4% African American, 23.8% Caucasian, 13.2% Hispanic, 6.5% 2 or more races, 2.5% Asian). Dr. Bryant has been a special educator for over 30 years, working with students of all ages, including students with developmental delays and intellectual disabilities, as well as students on the autism spectrum. Dr. Bryant earned an undergraduate degree from Old Dominion University in 1985, Virginia; graduate degrees from Hampton University in 1987, Virginia; and Old Dominion University in 2005; and she received her doctorate of education at the University of Phoenix in 2015, Arizona. Her primary area of research is inclusion practices and logistics at the preschool level. Dr. Bryant has presented at numerous education conferences.

References

- Banerjee, R., Lawrence, S., & Smith, S. (2016). Preschool inclusion: Key findings from research and implications for policy. Child Care & Early Education Research Connections, 3–15.

- Casale-Giannola, D. (2011). Inclusion in CTE: What works and what needs fixin’. Tech Directions, 70(10), 21–23.

- DeMonte, J. (2013). High-quality professional development for teachers: Supporting teacher training to improve student learning. Center for American Progress. (ERIC No. ED561095).

- Drack, M. (2009). Ludwig von Bertalanffy’s early system approach. System Research & Behavioral Science, 26, 563–572. doi:10.1002/sres.992

- Eddles-Hirsch, K. (2015). Phenomenology and educational research. International Journal of Advanced Research, 3, 251–260.

- Efthymiou, E., & Kington, A. (2017). The development of inclusive learning relationships in mainstream settings: A multimodal perspective. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1304015. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2017.1304015

- Flynn, S., & Korcuska, J. (2018). Credible phenomenological research: A mixed-methods study. Counselor Education & Supervision, 57, 34–50. doi:10.1002/ceas.12092

- Gaines, T., & Barnes, M. (2017). Perceptions and attitudes about inclusion: Findings across all grade levels and years of teaching experience. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1313561. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2017.1313561

- Giorgi, A. (2010). Phenomenology and the practice of science. Existential Analysis, 21(1), 3–22.

- Giorgi, A. (2012). The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 43, 3–12. doi:10.1163/156916212X632934

- Hall, A., & Niemeyer, J. A. (2000). Inclusion of children with special needs in school-age child care programs. Early Childhood Education Journal, 27, 185–190. doi:10.1007/BF02694233

- Harvey, M., Yssel, N., Bauserman, A., & Merbler, J. (2010). Preservice teacher preparation for inclusion. Remedial and Special Education, 31(1), 24–33. doi:10.1177/0741932508324397

- Hsien, M., Brown, P., & Bortoli, A. (2009). Teacher qualifications and attitudes toward inclusion. Australasian Journal of Special Education, 33(1), 26–41. doi:10.1375/ajse.33.1.26

- Ignatovitch, E., & Smantser, A. (2015). Future teacher training for work in inclusive educational environment: Experimental study results. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 214, 422–429. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.699

- Keaney, M. T. (2012). Examining teacher attitudes toward integration: Important considerations for legislatures, courts, and schools. St. Louis University Law Journal, 56, 827–856.

- Kessell, J., Wingenbach, G., & Lawver, D. (2009). Student teachers’ knowledge of the individuals with disabilities act. Journal of Academic & Business Ethics, 2, 21–30.

- Kwon, K.-A., Hong, S.-Y., & Jeon, H.-J. (2017). Classroom readiness for successful inclusion: Teacher factors and preschool children’s experience with and attitudes toward peers with disabilities. Faculty Publications, Department of Child, Youth, and Family Studies., 153, 360–378.

- Mitchell, L., & Hegde, A. V. (2007). Beliefs and practices of in-service preschool teachers in inclusive settings: Implication for personnel preparation. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 28, 353–366. doi:10.1080/10901020701686617

- Norwich, B., & Nash, T. (2011). Preparing teachers to teach children with special education needs and disabilities: The significance of a national PGCE development and evaluation project for inclusive teacher education. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 11(1), 2–11. doi:10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01175.x

- Odom, S. L., Buysse, V., & Soukakou, E. (2011). Inclusion for young children with disabilities: A quarter century of research perspectives. Journal of Early Intervention, 33, 344–356. doi:10.1177/1053815111430094

- Piper, A. W. (2007). What we know about integrating early childhood education and early childhood special education teacher preparation programs: A review, a reminder and a request. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 28, 163–180. doi:10.1080/10901020701366749

- Stein, L., & Stein, A. (2016). Re-thinking America’s teacher education programs. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 89, 191–196. doi:10.1080/00098655.2016.1206427

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. U.S. Department of Education. (2015, September 14). Policy statement on inclusion of children with disabilities in early childhood programs. Retrieved from https://ed.gov/policy/speced/guid/earlylearning/joint-statement-full-text.pdf

- von Bertalanffy, L. (1972). The history and status of General Systems Theory. Academy of Management Journal (Pre-1986), 15(000004), 407–426. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.docview/229596723?accountid=35812 ( Original work published 1928

- Yang, C. H., & Rusli, E. (2012). Teacher training in using effective strategies for preschool children with disabilities in inclusive classrooms. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 9(1), 53–64. doi:10.19030/tlc.v9i1.6715