Abstract

Theoretically emerged from Vygotsky`s sociocultural theory of mind (SCT), Dynamic Assessment (DA) highlights the notions of mediation and reciprocity as the dynamics of learners` progress toward independent functioning. As a qualitative inquiry into the nature of Iranian EFL learners` development in DA based academic writing courses, this study examined their emerging mediation typologies and reciprocity patterns within the face-to-face (FTF) and Computer-Mediated (CM) contexts. In so doing, microgenetic analysis was applied to the interactions of four Iranian EFL learners with an expert within the focused contexts. Results indicated that although mediation typology of the FTF context encourages private analysis and other-regulation, CM mediation facilitates smart correction and consciousness raising. CM mediation also promotes learners` critical thinking through its focus on form. Based on the noticed differences, reciprocity in the CM context targets higher cognitive levels of performance and problem-solving. This study highlights the significance of the CM form of DA in guiding learners` efforts to get self-regulation in academic writing.

Public Interest Statement

This qualitative inquiry reports Iranian EFL learners` development in dynamic assessment (DA) based academic writing courses. In this research study, we investigated the role of learners’ mediation and responsiveness through DA in two different contexts of face-to-face (FTF) and Computer-Mediated (CM). Furthermore, the study put the spotlight on the specific characteristics of each context. The findings revealed that while FTF encourages learners’ private analysis, CM enhanced their consciousness-raising along with critical thinking in their academic writing. The results of the study indicated the significance of the CM context in guiding the learners’ efforts to move from their current capacity toward self-regulation in academic writing.

1. Introduction

Vygotsky`s Sociocultural Theory of Mind (SCT) considers learning a social enterprise mediated by social and cultural artifacts, the most influential of which is language (Lantolf & Thorne, Citation2006). Based on SCT, language contributes to individuals` emerging previously unknown abilities and ways of conceptualizing the world (Palinscar, Citation1998).

Dynamic assessment (DA), as the main realization of SCT, regards emergent abilities as a part of learners` Zone of Potential Development (ZPD) in contradiction with learners` already developed abilities belonging to their Zone of Actual Development (ZAD). DA targets learners` ZPD by engaging them in interactions with experts (Lantolf & Thorne, Citation2006). In this way, DA highlights the notion of mediation which implies that social and contextual interactions have the potential of regulating learners` development (Lantolf, Citation2000; Lantolf & Poehner, Citation2004). Through investigating learners` response to mediation, DA further depicts the details of their developing abilities (Poehner, Zhang, & Lu, Citation2014) and how they modify and subject mediation to their individualized needs (Nazari & Mansouri, Citation2014). Thus, DA implies that mediation and reciprocity patterns reveal valuable insights into learners` linguistic and cognitive development.

DA has increasingly been applied to writing instruction in the classroom (Face-to-Face (FTF)) and Computer-Mediated (CM) contexts (e.g., Aljaafreh & Lantolf, Citation1994; Antón, Citation2003; Nassaji & Swain, Citation2010; Oskoz, Citation2005; ; Poehner, Citation2005b; Poehner et al., Citation2014; Shrestha & Coffin, Citation2012) to examine the ways through which learners extend their mental functions and engage in knowledge negotiation and construction. However, research devoted to mediation and reciprocity aspects of learners` performance, which represent the means and processes of their cognitive development in the two contexts is rare (Ebadi, Citation2016). Given that, the study uncovers the patterns of mediation moves and learners` reciprocity in the FTF and CM contexts. By investigating mediation patterns, this study reveals the potentials of each context in providing learners with appropriate forms of help and facilitating their writing development. Learners` reciprocity patterns, however, show the details and stages of their development along with the ways they managed their learning processes. In doing that, this study uses the qualitative approach of DA, which enables researchers to present a thick description of each investigated element and the interconnection between them in a way that general conclusions can be drawn on the development of learners in each context.

1.1. Theoretical orientation of the study

Ferris (Citation2004) believes that mediation in writing instruction, irrespective of its delivery condition, is offered systematically, (mainly) indirectly and in a way that addresses the differences between different types of errors. Mediation should also target learners` real language needs (Van Beuningen, Citation2010) and their cognitive development (Bitchener & Knoch, Citation2010). These qualities of mediation are highly emphasized in DA which uses an emergent and flexible pattern of mediation moves to not only discover learners` problems but also empower them in their overcoming (Sternberg & Grigorenko, Citation2002). In this way, DA challenges the conventional views on the separation of instruction and assessment and provides them with various forms of support to enhance their functioning (Lidz & Gindis, Citation2003). DA, also, expedites learners` process of gaining knowledge by influencing their cognitive development and making it observable as it transpires (Kuhn, Citation1995). The feature, in its turn, enables DA researchers to report on the details of learners` struggling to get higher levels of functioning.

Lantolf and Poehner (Citation2004) make a distinction between two main DA approaches, namely, interventionist and interactionist. The former approach, known as the sandwich format (Sternberg & Grigorenko, Citation2002), involves test-intervention-retest sequence which allows for using pre-established interventions in separate sessions in relation to learners (Haywood & Lidz, Citation2007). The interactionist approach, in contradiction, is inclined to the assessment of the dynamics of the learners` development. Mediation in this approach is not established in advance; it is offered in dialogic interactions with learners to meet their on-the-spot problems (Azabdaftari, Citation2013b). In this approach, the researcher continually examines mediation nature in relation to learners` ZPD. This approach, which has been described as the cake format (Sternberg & Grigorenko, Citation2002), is inherently related to qualitative DA studies which examine individuals’ steps of development.

This study used the interactionist DA to target learners` writing development using oral and written mediation in a dialogic way. The graduated nature of mediation from implicit to explicit made it possible to get a clearer understanding of their ZPD and to evaluate their internalization of mediation. Aljaafreh and Lantolf (Citation1994) believe that mediation internalization shows learners` microgenetic development characterized by their different levels of functioning and movement form the stage of other-regulation (wherein the learner totally relies on the support of the assessor in doing the task), to the partial-regulation stage (when he acquires the skill partially but still needs the assessor`s help) and getting self-regulation (where he internalizes the mediation completely and acts independently). Thus, this study explored learners` microgenetic development through investigating their mediation internalization and reciprocity patterns and realizations of these three levels in their functioning.

2. Literature review

The inadequacy of traditional approaches of testing in examining writing development led to the conduction of a good many of DA studies, which have been mainly reported based on the setting dichotomy of FTF and CM contexts. In what follows some of them are presented.

2.1. FTF DA-based writing studies

Aljaafreh and Lantolf (Citation1994), in one of the first DA studies which is highly referenced, investigated the effectiveness of DA in meeting grammatical errors in writing skill, and stated that joint participation and meaningful interactions in DA improve the richness of the learning context. Their study implies that DA mediation facilitates the process of second language learning and avoids fossilization by providing learners with negative evidence on their errors. Lantolf and Aljaafreh (Citation1995) investigated the effectiveness of DA in teaching modals, prepositions and verb tenses over a two-month course, and reported learners` progression and regression during the program until they could fully grasp the instructional points. Darhower (Citation2007) examined cognitive development of students in narrative writing grammar under the principles of DA, and supported the efficacy of mediation in individualized treatment of learners` ZAD and ZPD which is among the largely claimed advantage of DA. Nassaji and Swain`s (Citation2010) case study compared the effects of DA and non-DA mediation on the development of Korean ESL learners in using English articles. The first group of their study participants received corrective feedback within their ZPD, while the second group received randomly organized prompts and corrections. Analysis of the data showed that ZPD learners experienced development more than the non-ZPD ones. Their study can be considered a pioneering one in the sense that they examined learners` development both within and between sessions of the DA program. Hadidi`s (Citation2012) mixed study examined the microgenetic development of Iranian adult EFL learners who received corrective feedback on the argumentative quality of their writings. Findings of the study revealed that DA could target learners` educational needs more accurately than the traditional approach of writing instruction. The study also showed that DA could be used for modifying reflective processes and cognitive strategies of writing. Farrokh and Rahmani (Citation2017) investigated the effects of DA and non-DA approaches to writing instruction on learners` performance in the transcendence tasks. The research, which was built on the positive effects of the DA on writing development, showed that the experimental group which received DA corrective feedback performed better not only in posttests but also in transcendence tasks. This study goes for the contextualized effects of DA by showing the better performance of the DA group in more difficult tasks.

2.2. Computerized DA studies

Davin (Citation2013) argues that among the main justifications of conducting DA studies over the internet context is the fact that DA integration into the classroom is time-consuming and, therefore, makes it difficult for the assessor to work efficiently with learners. In order to overcome this and similar problems, some DA researchers have focused on the internet context.

Shrestha and Coffin (Citation2012) explored the applicability of DA writing instruction through email exchanging and reported that it targeted the areas needed more support, and contributed to students` writing development by meeting their individual needs. Their study, however, can be criticized on the basis of their medium of instruction in the sense that email might not be much prevalent in writing instruction. Zhang, Wanyi, and Wanyi (Citation2013) presents a DA framework of writing instruction via web-based tools. The framework, which combines features of DA and writing process pedagogy, teaches and assesses students in writing different genres of texts. The researchers argue that its advantages are more noticeable when the quality and objectives of mediation are determined in advance, and the coherence of DA sessions are guaranteed. Suwantarathip and Wichadee (Citation2014) believe that learners who are taught writing on the internet context not only perform better but also have more positive views toward collaborative learning. Mathew, Al-Mahrooqi, and Denman (Citation2017) investigated the efficacy of electronically offered mediation which was supported by face-to-face interactions. In so doing, they trained 12 students, who were taking the Foundation Program of the Middle East College (MEC), using a combination of online and open-ended dialogic mediation. The study implies that electronic mediation which is attuned to learners` ZPD is more effective than the corrective feedback which is offered based on the assessor`s guess at the level of help learners need.

Presented studies, including the works of Iranian researchers, well support the efficacy of DA mediation in targeting learners` writing needs and contributing to their emerging abilities. However, they have mainly focused on a few grammatical items or rhetorical aspects of writing and traced learners` development either within or between DA sessions of instruction. They have ignored such issues as the very nature of DA mediation and learners` responses to them. They also lack the comparison between FTF and CM contexts of DA instruction. Given that DA writing instruction has been applying to both FTF and CM contexts, the comparison between them shows how learners act and develop in each context. Therefore, this study targets these issues. In filling the mentioned gaps, this study investigated the following two research questions:

What do FTF and CM mediation moves reveal about the potentials of the two contexts in regulating learners` academic writing development?

What do the reciprocity patterns within FTF and CM contexts reveal about learners` academic writing development?

3. Methodology

3.1. Design

Following prominent DA studies (Ableeva, Citation2010; Aljaafreh & Lantolf, Citation1994; Poehner, Citation2005b), this study utilized the qualitative method in general and heuristic case study approach, in particular, to describe the performance of learners as individuals in details. In so doing, the microgenetic method was implemented to trace learners` movement toward self-regulation and cognitive development (Lantolf, Citation2000) and to reveal their mediation and reciprocity patterns. The method is also compatible with not only the classroom context but also the CM context which allows for offering simultaneous online mediation.

3.2. Participants and context

Participants of this study were four BA-level students of English Translation at Payame Noor university (Islam Abad Branch) in Iran. They were selected in terms of their writing proficiency levels from students of a sophomore class who were sent the DIALANG link (a free online diagnostic assessment tool in language learning available athttps://dialangweb.lancaster.ac.uk/), asked to take its English writing exam, and send the researcher their exams results. As a diagnostic assessment tool, DIALANG provides its users with test scores based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). This study used the writing section of DIALANG, as a placement test, to determine participants` levels of writing ability. Based on their DIALANG results, two of the participants of this study were at an elementary level (A1) and two of them were at an intermediate level (B1).

The study randomly selected four low and intermediate proficiency level learners out of about 20 and put them into two groups of FTF and CM, respectively. In each group, there was one elementary level and one intermediate level student. For ethical reasons, participants were given pseudonyms (S1, S2, …) to protect their identities. They were also assured that their privacy will be protected. Learners of the FTF group received instruction in the class context, while CM learners used Google Docs (a free writing and editing tool, used for creating, editing and sharing online documents and tracing changes made by each writer). It should be noted that this study designed its writing course to apply to its experiment. In other words, the writing course was an additional yet quite relevant and beneficial course to the English Translation curriculum.

3.3. Data collection procedure

The DA course was conducted from July to August 2017. In each session, learners wrote an academic text in about 150 words based on the topics selected by one of the researchers. Both groups of learners received mediation mainly after finishing their texts. FTF learners delivered their texts by hand, while CM learners did so electronically. In doing that, CM learners pushed the Check mark, which showed that they completed their writing, and touched the Add People icon, where they entered the researcher`s email address. The email, which was in the form of an invitation to edit the learner`s text, included a small box (Open in Docs). By touching that box, the researcher could see the text and comment on it. Since the learner had the program opened at the time, he/she could see the researcher`s comments.

In implementing this DA course, the researcher adapted the “writing cycle” (Ho & Usaha, Citation2015) in which topic selection was followed by brainstorming, writing the first drafts and sharing or delivering them on the side of learners. The researcher, then, gave comments and mediation on their first drafts. Having revised the texts and delivered or shared their second drafts, students received the next level of mediation. Next, they revised their texts and delivered or shared their third drafts and received the researcher`s comments. After revising the text and delivering or sharing fourth drafts, students got the next level of mediation, revised their texts and delivered or shared fifth drafts, and got the last level of mediation. Table shows the order of the stages of the writing cycle for FTF and CM learners, which indicate that in line with DA principles, this study presented mediation levels from implicit to explicit assistance to leaners.

Table 1. Writing cycle of the study

Crème and Lea (Citation2003) believe that grammar and punctuation account for most of the academic writing errors of university students. Given that, this DA program mediated the grammar and punctuation of students` writings. Two weeks after the project, learners of the two groups were engaged in a more difficult writing, which aimed at testing their capability of transferring their acquired knowledge to another more challenging task. Furestian et al., (Citation2002) name such a task “transcendence task” and maintain that it involves “the widening of interaction beyond its immediate goals to other goals that are more remote in time and space” (p. 76).

3.4. Materials and tasks

For the diagnostic stage of the study, which aimed at collecting basic information about learners writing problems, the researcher used DIALANG results and a sample of their writings. DIALANG writing test, as a general diagnosis tool, highlighted learners` grammatical writing problems. Learners` writing samples, however, were used as a complementary tool mainly for recognizing their punctuation errors.

For DA sessions, learners did a writing task in each session. The topics were taken mainly from the English learning websites (e.g., https://www.study.com and https://www.thoughtco.com) that classify writing topics based on their main grammatical requirements. The frequent usage of punctuation marks in different texts made it easier for the researcher to find relevant data to their usage in each session.

Transcendence task, in this study, was investigated in terms of writing a summary of learners’ instructional process and the points they learned in 300 words. The task was believed to be more difficult than DA tasks for two reasons. First, it covered a range of different grammatical and punctuation items whose observance needed a good amount of related information (Robinson, Citation2005). Second, it was longer than the DA tasks. This means that they needed to write more about details and the possibility of committing errors increased for them.

4. Data analysis and results

For analyzing learners` microgenetic development, the study reported some instances of learners` interactions with the researcher in the form of Language Related Episodes (LREs) within both DA sessions and the transcendence task. Swain (Citation2001) describes LRE as ‘‘any part of a dialogue where students talk about the language they are producing, question their language use, or self-correct their language production” (p. 287). Therefore, they are the sites of language learning.

Descriptive data was used for analyzing the frequency of mediation reciprocity moves of each learner. In this way, this study elaborates on the nature of mediation and learners` reciprocity as emerged from the microgenetic analysis of relevant data. In so doing, first, mediation typologies are examined followed by the learners` reciprocity to highlight the development trajectory of the learners writing development in FTF and CM contexts.

4.1. Mediation typologies

According to Poehner (Citation2005b), developing typology is necessary for tracing learners` gradual development over time. Through tracing the level of mediation each learner needed, the researcher came up with the mediation typologies in the FTF and CM contexts. Mediation typology, in this study, shows the nature of all mediation levels used by the researcher in both DA and TR tasks across each context. This study used a mixture of oral and written mediation arranged from implicit to explicit levels to support learners` movement toward self-regulation in the FTF context. As for the CM context, however, mediation was only written. It should be mentioned that mediation typologies in the two contexts were applied to both grammar and punctuation correction.

4.1.1. Mediation typology of the FTF context

Table shows the five mediation categories emerged out of the researcher’s interactions with FTF learners. Each mediation category targeted one or two mediational strategies to help learners move beyond their current levels of functioning. In what follows, different mediational strategies in the FTF context are presented and exemplified.

Table 2. Materials and tasks of the study

Table 3. Mediation typology of the FTF context

It is worth mentioning that mediation in the FTF contexts was divided into three main categories, namely, private analysis, error treatment, and knowledge construction.

Zero level. Reliance on Intuitive and Conscious Language Awareness (RILCA)

The most implicit level of mediation, according to Aljaafreh and Lantolf (Citation1994), is the mediator`s mere presence as it triggers correction on the side of learners. This level is called “collaborative framework” or the “zero level of mediation”. The zero level of mediation in the FTF context was realized by asking each learner to read his/her text, find and correct its errors prior to the instruction. Learners` performance, at this stage, was influenced by their intuitive and conscious knowledge rather than the researcher`s help.

Level 1. Encouraging Collaborative Correction (ECC)

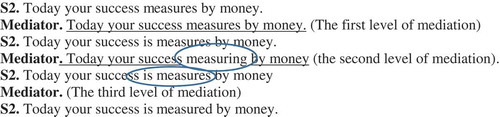

As the second most implicit mediational strategy used in FTF context, ECC aimed at making learners aware of the significance of the social context of interaction in noticing and correcting errors they first had failed to meet. At this level, the mediator underlined the erroneous sentence and asked them to find the error and correct it. The following example, taken from the fourth DA session of S2, show how she used this mediational strategy to meet her error in relation to future tense.

Student 2 (DA 4: Future Tense)

S2. In my view majority of people in my country going to go other country for education.

Mediator. In my view majority of people in my country going to go other country for education. (Level 1, underling the erroneous sentence)

S2. In my view majority of people in my country are going to go other country for education.

Level 2. Orienting Learners to Their Own Knowledge (OLK)

The third most implicit mediational strategy in the FTF context was helpful when learners had the necessary knowledge to correct their errors but needed the researcher`s help in recognizing them (Aljaafreh & Lantolf, Citation1994). At this level, the mediator circled the error and asked learners to correct it. The following example shows how S1 successfully used this mediational strategy to overcome her grammatical error.

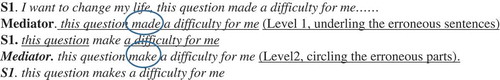

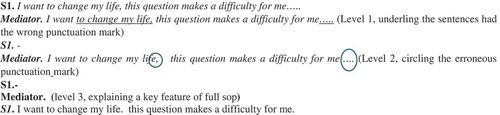

Student 1 (DA1: Simple Present Tense)

level 3.1. Being the Trigger Point for The Forgotten Point (BTPFP)

BTPFP, as the first category of the “Error Correction” mediational strategy, involved the researcher`s oral explanation of a key point related to the intended error. In the following excerpt, the third level of mediation helped S1 to remember that at the end of each sentence “full stop” is to be used.

Student1 (DA1: Full Stop)

level 3.2. Clearing a Related Misunderstanding (CRM)

Another function of the “Error Correction” mediational strategy was clearing a related misunderstanding to the error at hand. In the following instance, for example, S2 failed to correct her error on the formation of simple present passive tense, even though she correctly recognized it after getting the first level of mediation. The third level of mediation met her misunderstanding based on which she regarded “is + simple present verb” as the passive form of simple present tense.

Student 2 (DA3: Simple Present Passive)

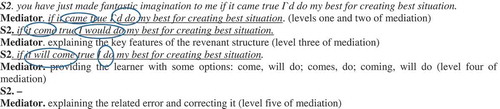

Level 4. Stablishing the Basis of the Related Knowledge to the Given Feature (SBK)

According to Aljaafreh and Lantolf (Citation1994), one reason of learners` unresponsiveness is their lack of basic knowledge to the intended structure. The appropriate level of mediation, in this case, would be stablishing the related knowledge. The following example is relevant here as it involved stablishing the related basic knowledge through both correction and explanation on the side of the mediator.

Student 2 (DA6: Conditional Sentences)

4.1.2. Mediation typology of the CM context

Table shows that six main mediational categories were used in the CM context each of which targeted one mediational strategy to help learners move beyond their current levels of functioning (Poehner, Citation2005b). In what follows, different mediational strategies in the CM context are presented and exemplified. Mediation in the CM context was divided into four main categories, namely, auto-correction, consciousness raising, focus on form, and knowledge construction.

Level 1. Encouraging Context Reliance (ECR)

The first most implicit mediational strategy in the CM context was related to the inherent feature of the Google Docs; underling errors and suggesting correction options (Ebadi & Rahimi, Citation2018). The feature was mainly useful when it came to the focus on the grammar of academic writing. Since both the researcher and learners were online at the same time, the researcher could easily trace the changes happened as a result of this mediational strategy. The following example is relevant here.

Student 4 (DA2: Simple Present Passive)

S4. Natural places are endanger by humans.

S4. Natural places are endangered by humans.

level 2. Emphasizing Top-Down and Bottom up Analyses (ETBA)

The next implicit mediational strategy in the CM context, which involved red highlighting the erroneous sentence by the mediator, encouraged both a top down and a bottom up analyses of sentences, as it triggered examining the syntax or punctuation at both the sentence and word levels.

Student 3 (DA1: Noun Determiners)

S4. I asked question from experienced people.

Mediator. I asked question from experienced people. (the first level of mediation).

S4. I asked that question from experienced people.

Level 3. Emphasizing Bottom-Up Analysis (EBA)

Correction of some academic writing errors lower in ZPD (in comparison with the above category), required the second chance of analyzing bottom up relations. The following episode can be referred to in this regard.

Student 4 (DA1: Verb Tense Consistency)

S4. Smith was an optimist person who believe in openness trade and personal gain.

Mediator. Smith was an optimist person who believe in openness trade and personal gain. (first level of mediation).

S4. –

Mediator. Smith was an optimist person who believe in openness trade and personal gain. (second level of mediation)

S4. Smith was an optimist person who believed in openness trade and personal gain.

Level 4. Filling Knowledge Gaps (FKG)

Given that the first and second mediational strategies in the CM context led to identifying academic writing errors, learners who needed a further level of mediation could use appropriate materials they were sent via Google Docs to fill their knowledge gaps.

Student 3 (DA2: Plural Nouns)

S3. We can use too many facility, because this cities has some facility to comparison with small cities.

Mediator. We can use too many facility,…. (the first level of mediation)

S3. -

Mediator. We can use too many facility,…. (the second level of mediation)

S3. –

Mediator. Receiving instructional materials (the third level of mediation) (http://dictionary.cambridge.org/grammar/british-grammar/determiners/determiners-and-types-of-noun)

S3. We can use too many facilities, ….

In above example, student 3 changed his incorrect form after the third level of mediation. Therefore, it can be assumed that the process of mediation filled his knowledge gap in relation to the agreement between determiners and nouns.

level 5. Self- Reliance in Managing Errors (SME)

The fourth mediational strategy in CM context aimed at making learners examine their academic writing errors considering the choices they were offered (Birjandi & Ebadi, Citation2012). Since CM learners had no more interaction with the mediator at this stage, their corrections could mainly be contributed to their management of errors by referring to their own criteria of what is correct and/or their mere guesses.

Student 3 (DA3: Passive Voice of Simple Present)

S. Sometimes parents want their children to commit crimes. In this situation parents must be punished until crimes be restricted.

Mediator. In this situation parents must be punished until crimes be restricted. (the first, second and third levels of mediation)

S. In this situation parents must be punished until crimes be restricted.

Mediator. presenting some choices (are, is, was, were)

S. In this situation parents must be punished until crimes are restricted.

In the above example, the response of S3 to the first three levels of mediation is presented in a single S turn because his only change was made after getting the third mediation level.

Level 6. Other-Reliance in Correcting Errors (OCE)

As the last mediational strategy, OCE, involved correcting errors with complete reliance on the mediator. At this stage, CM learners had not only the chance of internalizing mediation but also asking their questions and receiving to the point explanations. Below, a relevant example to this mediational strategy is presented.

Student 4 (DA2: Parallel Structures)

S4. government has three roles; generate public goods, creating economic security at the country and maintaining the borders of the country.

Mediator. generate public goods, creating economic security at the country and maintaining the borders of the country (first level of mediation)

S4. generate public goods, creating economic security at the country and maintaining the country borders.

Mediator. generate public goods, creating economic security at the country and maintaining the country borders (second level of mediation).

S4. produce public goods, creating economic security at the country and maintaining the country borders.

Mediator. Sending instructional materials and/or links (third level of mediation) (https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/623/1/)

S4. production public goods, creating economic security at the country and maintaining the country borders.

Mediator. Suggesting some choices (producing, produced, produces, productions) (fourth level of mediation)

S4. productions public goods, creating economic security at the country and maintaining the borders of the country.

Mediator. correcting the error at hand and explaining about it. (fifth level of mediation)

The above LREs specified learners` academic writing errors and the degree to which they needed mediator`s help in overcoming them. Although the findings cannot be generalized, they show the nature of error treatment in the FTF and SCM contexts.

This study investigated progression and/or regression of learners` academic writing using the regulatory scale of Aljaafreh and Lantolf (Citation1994), based on which frequency and type of help learners need represent their development. The regulatory scale included 5 levels representing three stages of development namely other regulation (levels 1–3), partial regulation (level 4) and self-regulation (level 5). Following Aljaafreh and Lantolf (Citation1994), this study regarded the “quality” and “frequency” of mediation learners needed as two criteria for microgenetic development. Mediation moves used in the two contexts of the study are presented in the Table to . It was mentioned before that mediation in each context was ordered from the most implicit to the most explicit form.

Table 4. Mediation typology in the CM context

Table 5. Type and frequency of mediational moves for S1

Table shows that mediation moves 0, 1 and 2 which constituted the most implicit mediation levels were used more frequently than others for S1. Therefore, following Aljaafreh and Lantolf (Citation1994), who claim that the fewer the learners require explicit mediation the more they exhibit microgenetic development, S1 exhibited microgenetic development and achieved a self-regulated level in academic writing skill. Moreover, S1 totally received equal mediation moves for grammar and punctuation, which might be related to the difficulty of both areas in academic writing for her. It is clear that in the TR session in which the writing task was more difficult, she required more explicit mediation on grammar, which showed her regression in that aspect of academic writing.

Based on Table , the total number of implicit levels of mediation S2 received was more than explicit levels. It shows that she could achieve self-regulation stage in academic writing skill (Aljaafreh & Lantolf, Citation1994). Moreover, although she received an almost equal number of corrections for her grammar and punctuation, the number of times she received SBK (Stablishing Basic Knowledge) mediation for correcting grammar was more than the time she received this level of mediation for correcting punctuation. It showed that she got more new knowledge in grammar correction than in punctuation correction.

Table 6. Type and frequency of mediational moves for S2

4.1.2.1. Mediational moves of CM learners

Simultaneous correction on the internet context of this study led to the usage of a specific number of mediational moves whose frequencies were different across CM learners. Below, you will see related information to the usage of these moves in relation to each learner.

Based on Table , S3 showed the signs of microgenetic development because he received more implicit levels of mediation. The table also shows that after examining top down and bottom up relationships of sentences, S3 mainly relied on the materials he received through Google Docs in correcting his errors. This shows the significance of simultaneous mediation in triggering higher levels of performance (Jeon, Citation2007; Trofi Movich, Ammar, & Gatbonton, Citation2007). Moreover, the OCE row shows that S3 could gain a good amount of academic writing knowledge using the researcher`s explicit explanation (Alsagoff, Citation2016).

Table 7. Type and frequency of mediational moves for S3

The higher number of grammatical corrections S4 received in the program showed that her microgenetic development was mainly related to the grammatical performance. Because she had used most of the punctuation marks correctly, she received little if any correction in that regard. Moreover, the pretty low number of SME and OCE mediational strategies shows that she had a good knowledge of grammar whose trigger needed mainly the implicit levels of mediation. Wu, Wu, Chen, and Chen (Citation2014) argue that CM mediation has a lot to do with developing critical thinking and problem-solving processes. Jonassen and Kwon (Citation2001) in much the same vein, emphasize that the very nature of computerized mediation helps learners to reflect on what they are going to convey and be analytical of its content.

4.2. Reciprocity typology

As far as the reciprocity typology of learners in this study is concerned, irrespective of the context in which learners of the study were instructed, four main categories emerged: lack of responsiveness to mediation, partial responsiveness to mediation, correcting the academic writing errors, and getting independence. Table presents the emergent categories, their descriptions and reciprocity moves.

Table 8. Type and frequency of mediational moves for S4

Table 9. Reciprocity typology

Table shows that the direction of learners` movement to self-regulation in academic writing development started from lower levels of responsiveness (lack of responsiveness) to higher ones (getting independence in the usage of grammatical and punctuation errors). Based on this table each reciprocity level included one or more reciprocity moves to the researcher`s mediation. In what follows reciprocity moves are exemplified.

Level 1. Lack of Responsiveness

Throughout this DA based academic writing course, sometimes learners failed to identify or correct their errors even with the researcher`s mediation.

S3 (DA5: Possessive Adjective)

Sh. Parents can give us solution with they`re experience.

R. Parents can give us solution with they`re experience. (The first level of mediation)

S3. –

Level 2. Partial Responsiveness

In the following example, as an example of partial responsiveness, S1 truly recognized and corrected the first future verb in her sentence but missed the second one.

S1 (DA2: Future Tense)

S1. People will finding the study will not having any future.

Mediator. People will finding the study will not having any future (The first level of mediation).

S1. People will be finding the study will not having any future

Level 3. Error Correction

The next form of response, in this study, involved error correction on the side of learners using the mediation they received.

S4 (DA2: Plural Nouns)

S4. Humans will have a lot of problems in their life.

Mediator. Humans will have a lot of problems in their life. (the first level of mediation)

S4. Humans will have a lot of problem in their life.

Level 4. Getting Independence

As the highest level of reciprocity move, “Getting independence” happened when learners became completely independent in using the intended structures and features. In that case, they did not need the researcher`s mediation for writing their sentences.

4.2.1. Reciprocity moves of FTF learners

Table shows the type and frequency of the reciprocity moves of FTF learners, ordered from learners` low reciprocity to mediation to their high reciprocity to it.

Table 10. Type and frequency of reciprocity moves for S1

As Table shows, the total number of corrections resulted from independent correction (reciprocity move 10) and the highest implicit level of mediation (reciprocity move 9) account for almost half (84) of the corrections S1 did in this study. Moreover, the number of low reciprocity moves (reciprocity moves 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6) decreased over time, while their high reciprocity levels (here the reciprocity move 8) increased, which indicates her development toward self-regulation in academic writing skill. Her lack of responsiveness to different mediational strategies indicated her ZPD, as it led to the usage of more explicit mediational strategies which targeted the degree to which she could gain related knowledge.

Based on Table , the main reciprocity moves of S2 belonged to the Error Correction and Independence Getting categories. Among the Error Correction subcategories, CE, which involved using the most implicit levels of mediation had the highest frequency. These findings show her development toward self-regulation in academic writing skill. After CE, RDFM had the highest frequencies among subcategories of Error Correction. It showed that S2 could overcome a number of her errors through a spontaneous attempt to find relevant information and request for the type of mediation she found more useful. Therefore, her lack of responsiveness to different mediational strategies could not only indicate her ZPD but also show her development in handling her academic writing errors.

Table 11. Type and frequency of reciprocity moves for S2

4.2.2. Reciprocity moves of CM learners

Table shows that this study triggered independence of S3 in academic writing after the second session, and this trend had a constant effect on his writings until the end of the program (look at the SAWE mediation reciprocity). Besides, almost half of his responses to implicit levels of mediation led to the correct usage of the intended structure or punctuation mark. Comparison between RDFM and WC shows that he tended to rely on himself rather than requesting other forms of mediation in error correction. Extending this view, we can say that he was not willing to criticize the mediation even though he could not use it properly. The reason could be his sense of responsibility in learning (Newman, Griffin, & Cole, Citation1989).

Table 12. Type and frequency of reciprocity moves for S3

4.2.2.1. Reciprocity moves of S4

Table , in addition to showing the microgenetic development of S4 (based on the higher number of her responses to the implicit level of mediation), indicates that a high number of punctuation errors of S4 were correctly addressed through the SAWE reciprocity move which did not involve any form of mediation. It shows that immediate online correction did not hinder the possibility of self-correction provided that targeted errors are high in ZPD (Williams, Citation2012). Her grammatical errors, however, were mainly targeted using the CE reciprocity move to show that her grammatical errors were lower in ZPD compared to the punctuation ones. CTUM and RDFM reciprocity moves targeted the rest of the errors which needed stronger forms of the trigger.

Table 13. Type and frequency of reciprocity moves for S4

Although we represented quantitative data on mediation and reciprocity moves for showing learners` microgenetic development, qualitative data on the step by step development of learners could add to the validity of our findings. In so doing, the following LREs are presented.

Episodes 1 and 2 target the first and second times S1 was corrected for her negligence of using THE before ordinal numbers. As it is clear, the first time she got the mediation, she was at the third level of other regulation characterized by her dependence on mediation in error recognition and correction.

Episode 1: S1 (using THE before ordinal numbers)

It wasn’t first time she was here.

Mediator. (the first level of mediation)

S1. -.

Mediator. (the second level of mediation)

S1. It wasn’t a first time she was there.

Mediator. (the third level of mediation)

S1. It wasn’t the first time she was there.

Based on Episode 2, the second time she encountered the same problem, she needed two levels of mediation, showed her movement to the partial regulation stage.

Episode 2: S1 (reexamination of using THE before ordinal numbers)

Second effect of tv is that family is away from each other.

Mediator. (the first level of mediation)

S1. the second effect of tv is that family is away from each other

Our investigation showed that simultaneous correction led to more sensitivity to errors by CM learners and facilitated their fast microgentic development. In relation to the target of the following episode, although S4 was initially at the partial regulation stage, she soon got the self-regulation stage as she received no more mediation in that regard.

Episode 1: S4 (Verb Phrases)

His information was private. But they send out it.

Mediator. the first level of mediation

S4. But they had send out it.

Mediator. the second level of mediation

S4. But they send out his information.

5. Conclusion

This study highlighted the significance of context which plays a crucial role in the quality and nature of mediation moves in DA academic writing instruction. Regarding the first question, although the mediation moves of the FTF context emphasized private analysis and more explicit levels of mediation, the CM context encourages consciousness raising through using contextual prompts and more implicit levels of mediation. Considering the difference, it is assumed that the CM context encouraged the knowledge contributor (Block, Citation2007a) rather than merely the knowledge consumer view to learners and affected their self-representation in the program (Hyland, Citation2012a). The “developing-self” view of the study created more motivation for CM learners to decrease the distance between their “real-self” and “ideal-self” (Dornyei, Citation2005). In this way, the CM form of DA targets both learning potential and thinking potentials (Kozulin, Citation2011) of learners, while FTF form of DA mainly targets learning potential. Regarding the second question, the findings indicated that the difference in the mediation moves resulted in learners` different reciprocity patterns in the sense that FTF learners had more difficulty with acquiring knowledge and transferring it to the TR task (DeKeyser, Citation2007). Conducting delayed TRs can provide more insights into this finding.

The pedagogical implication of the present study lies in the fact that DA based academic writing instruction can be more facilitative if the context in which it is provided (Chen & Cheng, Citation2008) and its different potentials for writing development (Lahuerta, Citation2017) are considered.

Although the qualitative nature of this study limits the generalizability of its findings, it led to a description of the contributing aspects of FTF and CM contexts into microgenetic development of academic writing. Considering that, future research can delve into the potentials of FF and CM contexts into each stage of microgenetic development separately. They can also focus on the development of other aspects of academic writing such as lexical and rhetorical development in each context.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shokoufeh Vakili

Shokoufeh Vakili is a PhD candidate in Applied Linguistics at Razi university, Kermanshah, Iran. Her areas of interest include CALL, dynamic assessment and discourse analysis . She is the author of some articles in the areas of her interest and has presented both in and outside the country.

Saman Ebadi

Saman Ebadi is an associate professor in Applied Linguistics at Razi University, Iran. His research focuses on CALL, dynamic assessment, qualitative research, and sociocultural theory. He has published extensively in both international journals (e.g. Computer Assisted Language Learning, Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, Cogent Education, etc.) and local journals. He has also presented in both international and national conferences.

References

- Ableeva, R. (2010). Dynamic assessment of listening comprehension in second language learning ( Unpublished doctoral dissertation). The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

- Aljaafreh, A., & Lantolf, P. (1994). Negative feedback as regulation and second language learning in the zone of proximal development. Modern Language Journal, 78(4), 465–26.

- Alsagoff, L. (2016). Interpreting error patterns in a longitudinal primary school corpus of writing. The Asian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 3(1), 114–124.

- Antón, M. (2003, March). Dynamic assessment of advanced foreign language learners. Paper Presented at the American Association of Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C.

- Azabdaftari, B. (2013b). On the implications of Vygotskian concepts for second language teaching. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 1(2), 99–114.

- Birjandi, P., & Ebadi, S. (2012). Microgenesis in dynamic assessment of L2 learners’ socio- cognitive development via web 2.0. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 32, 34–39. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.006

- Bitchener, J., & Knoch, U. (2010). Raising the linguistic accuracy level of advanced L2 writers with written corrective feedback. Journal of Second Language Writing, 19, 207–217. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2010.10.002

- Block, D. (2007a). Second language identities. London: Continuum.

- Chen, C.-F., & Cheng, W.-Y. (2008). Beyond the design of automated writing evaluation: Pedagogical practices and perceived learning effectiveness in EFL writing classes. Language Learning & Technology, 12(2), 94–112.

- Creme, P., & Lea, M. R. (2003). Writing at university: A guide for students. UK: Open University Press.

- Darhower, M. (2007). Interactional features of synchronous computer-mediated communication in the intermediate L2 class: A sociocultural case study. CALICO Journal, 19(2), 249–277. doi:10.1558/cj.v19i2.249-277

- Davin, K. J. (2013). Integration of dynamic assessment and instructional conversations to promote development and improve assessment in the language classroom. Language Teaching Research, 17, 303–310. doi:10.1177/1362168813482934

- Dekeyser, R. M. (2007). Skill acquisition theory. In B. Vanpatten & J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction (pp. 97–113). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Ebadi, S. (2016). Mediation and reciprocity in online L2 dynamic assessment. CALL-EJ, 17, 18–42.

- Ebadi, S., & Rahimi, M. (2018). An exploration into the impact of web quest-based classroom on EFL learners’ critical thinking and academic writing skills: A mixed methods study. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 5(6), 617–651. doi:10.1080/09588221.2018.1449757

- Farrokh, P., & Rahmani, A. (2017). Dynamic assessment of writing ability in transcendence tasks based on Vygotskian perspective. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 2. doi:10.1186/s40862-017-0033-z

- Ferris, D. R. (2004). The “grammar correction” debate in L2 writing: Where are we, and where do we go from here? (and what do we do in the meantime…?). Journal of Second Language Writing, 13, 49–62. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2004.04.005

- Feuerstein, R., Feuerstein, R. S., Falik, L. H., & Rand, Y. (2002). The dynamic assessment of cognitive modifiability: The learning propensity assessment device: Theory, instruments and techniques. Jerusalem: International Center for the Enhancement of Learning Potential.

- Hadidi, A. (2012). Fostering argumentative writing ability in the zone of proximal development: A dynamic assessment. Paper presented at the Canadian Association for the Study of Discourse and Writing Conference, Wilfred Laurier and University of Waterloo, Ontario.

- Haywood, H. C., & Lidz, C. S. (2007). Dynamic assessment in practice: Clinical and educational applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ho, P., & Usaha, S. (2015). Blog-based peer response for L2 writing revision. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29, 1–25.

- Hyland, K. (2012a). Disciplinary identities: Individuality and community in academic discourse. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Jeon, M. (2007). Language ideologies and bilingual education: A Korean-American perspective. Language Awareness, 16(2), 114–130. doi:10.2167/la369.0

- Jonassen, D. H., & Kwon, H. (2001). Communication patterns in computer-mediated versus face-to-face group problem solving. Educational Technology Research and Development, 49(10), 35–52. doi:10.1007/BF02504505

- Kozulin, A. (2011). Learning potential and cognitive modifiability. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 18(2), 169–181. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2010.526586

- Kuhn, D. (1995). Microgenetic study of change: What has it told us? Psychological Science, 6(3), 133–139. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1995.tb00322.x

- Lahuerta, A. (2017). Analysis of accuracy in the writing of EFL students enrolled on CLIL and non-CLIL programs: The impact of grade and gender. The Language Learning Journal, 0957–1736, 1–12. doi:10.1080/09571736.2017.1303745

- Lantolf, J. (2000). Second language learning as a mediated process. Language Teaching, 33, 79–96. doi:10.1017/S0261444800015329

- Lantolf, J., & Aljaafreh, A. (1995). Second language learning in the zone of proximal development: A revolutionary experiment. International Journal of Educational Research, 23, 619–632. doi:10.1016/0883-0355(96)80441-1

- Lantolf, J. P., & Poehner, M. E. (2004). Dynamic assessment of L2 development: Bringing the past into the future. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1, 49–74. doi:10.1558/japl.1.1.49.55872

- Lantolf, J. P., & Thorne, S. L. (2006). Sociocultural theory and the genesis of second language development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lidz, C. S., & Gindis, B. (2003). Dynamic assessment of the evolving cognitive functions in children. In A. Kozulin, B. Gindis, V. S. Ageyev, & S. M. Miller (Eds.), Vygotsky’s educational theory in cultural context (pp.39-64). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mathew, P., Al-Mahrooqi, R., & Denman, C. (2017). Electronic intervention strategies in dynamic assessment in an Omani EFL classroom. In Revisiting EFL assessment (pp. 321–338). NY: Springer International Publishing.

- Nassaji, H., & Swain, M. (2010). A Vygotskian perspective on corrective feedback in L2: The effect of random versus negotiated help on the learning of English articles. Language Awareness, 9, 34–51. doi:10.1080/09658410008667135

- Nazari, B., & Mansouri, S. (2014). Dynamic assessment versus static assessment: A study of reading comprehension ability in Iranian EFL learners. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 10(2), 134–156.

- Newman, D., Griffin, P., & Cole, M. (1989). The construction zone: Working for cognitive change in school. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Oskoz, A. (2005). Students’ dynamic assessment via online chat. CALICO Journal, 22(3), 513–536. doi:10.1558/cj.v22i3.513-536

- Palinscar, S. A. (1998). Social constructive perspectives on teaching and learning. Annual Review Psychology, 49, 347–375.

- Poehner, M. E. (2005b). Dynamic assessment: A Vygotskian approach to understanding and promoting second language development. Berlin: Springer Publishing.

- Poehner, M. E., Zhang, J., & Lu, X. (2014). Computerized dynamic assessment (C-DA): Diagnosing L2 development according to learner responsiveness to mediation. Language Testing, 32(3), 337-357. 0265532214560390.

- Robinson, P. (2005). Cognitive complexity and task sequencing: A review studies in a componential framework for second language task design. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 43(1), 1–33. doi:10.1515/iral.2005.43.1.1

- Shrestha, P., & Coffin, C. (2012). Dynamic assessment, tutor mediation and academic writing development. Assessing Writing, 17, 55–70. doi:10.1016/j.asw.2011.11.003

- Sternberg, R. J., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2002). Dynamic testing. The nature and measurement of learning potential. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Suwantarathip, O., & Wichadee, S. (2014). The effects of collaborative writing activity using Google Docs on students’ writing abilities. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology - TOJET, 13(2), 148–156.

- Swain, M. (2001). Examining dialogue: Another approach to content specification and to validating inferences drawn from test scores. Language Testing, 18, 275–302. doi:10.1177/026553220101800302

- Trofi Movich, P., Ammar, A., & Gatbonton, E. (2007). How effective are recasts? The role of attention, memory, and analytical ability. In A. Mackey (Ed.), Conversational interaction in second language acquisition: A collection of empirical studies (pp. 171–195). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Van Beuningen, C. (2010). Corrective feedback in L2 writing: Theoretical perspectives, empirical insights, and future directions. International Journal of English Studies, 10, 1–27. doi:10.6018/ijes/2010/2/119171

- Williams, J. (2012). The potential role(s) of writing in second language development. Journal of Second Language Writing, 21(4), 321_331. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2012.09.007

- Wu, H.-Y., Wu, H.-S., Chen, I.-S., & Chen, H.-C. (2014). Exploring the critical influential factors of creativity for college students: A multiple criteria decision-making approach. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 11, 1–21. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2013.09.004

- Zhang, D., Wanyi, F., & Wanyi, D. (2013). Sociocultural theory applied to second language learning: Collaborative learning with reference to the Chinese context. International Education Studies, 6(9), 165–174. doi:10.5539/ies.v6n9p165