Abstract

Online discussions have emerged as one of the most popular practices of writing in academic contexts in the twenty-first century. Nevertheless, we know little about the rhetorical features and composition strategies employed by multilingual writers in these types of discussions. Using online discussions in the brainstorming phase of the process of writing a persuasive essay, this study inquired into the argumentative strategies employed by two multilingual writers when transitioning from one academic context to the other. A functional approach was utilized to analyze the discursive choices made by the two multilingual writers in online discussion posts and comments as well as the final versions of their essays. Findings reveal that while both multilingual writers successfully tackled the language demands of online discussions and persuasive essays through experimenting with a diverse array of discursive markers, they used different argumentative strategies to construct, strengthen, and position their ideas across the two academic contexts. This difference demonstrates the two multilingual writers’ ability to tap into their linguistic repertoires to creatively make discursive choices according to the demands of each academic context. Implications include the use of asynchronous, written online discussions as a springboard for multilingual writers to first argue ideas with an audience of peers to then select the strongest positions when writing more linguistically demanding pieces such as essays.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Multilingual writers have extraordinary abilities that go beyond the use of two or more languages to communicate. One such ability is the capacity to navigate different types of text, including the ones produced virtually. As engagement in online discussions has emerged as one of the most popular practices of writing in academic contexts in the twenty-first century, I decided to examine how two multilingual writers in my college-level English as a Second Language class would use language to create strong arguments in virtual discussions. My hope was to use these more informal ways of sharing opinions to help my students write traditional academic essays. I discovered the two students experimented with various argumentative strategies to construct, strengthen, and position their ideas across the two texts. Sharing and arguing with an audience of peers in online discussions can help multilingual writers improve argumentation in academic writing.

Multilingual writers have the unique ability to tap into all their linguistic repertoires, adjusting their composition strategies to the local demands of new situations, audiences, and writing genres (Canagarajah, Citation2011). Such ability provides multilingual writers with a vast array of literate experiences, prompting them to constantly engage in new ways of saying and acting in the world whenever using their languages (Kramsch, Citation2009). When living, studying, and learning in educational contexts where English is the main language of instruction, multilingual writers of diverse backgrounds are propelled into employing their unique abilities to succeed academically. This incredible feat involves not only the power of using two or more national languages or code-switching, but also the capacity of navigating many institutes, cultures, and modalities, including the many social practices mediated by digital media (Leonard, Citation2014).

As learning how to write in English has increasingly involved the use of new technologies, multilingual writers have become or need to become fluent in using language across different media. Engagement with digital literacies (Lankshear & Knobel, Citation2017), such as texting, tweeting, and emailing are examples of everyday texts multilingual writers use on a daily basis. Often, these digital texts are written in English as an additional language. This is also true for online discussions, which have emerged as one of the most popular digital literacy practices in academic contexts with the increased use of online course management systems (Andresen, Citation2009; Hew, Cheung, & Ng, Citation2010). In spite of this trend, we know little about the rhetorical features and composition strategies employed by multilingual writers in literacy practices mediated by the use of digital media, such as online discussions (Hopewell & Escamilla, Citation2014). Scarcer still are studies that explore ways engagement in literacy practices mediated by the use of digital media can aid in the process of writing for academic purposes and in academic contexts (Yi, Citation2014). Given the central role of digital media in our society, there is a pressing need for evidence-based research to demonstrate ways practices of digital literacy can be used in the development of multilingual writers’ academic writing (Chun, Citation2011; Moje, Citation2009; Thorne, Black, & Sykes, Citation2009).

The present study is an attempt to bridge this gap by sharing an in-depth analysis of the argumentative strategies employed by two Chinese-speaking multilingual writers when first engaging in online discussions at the brainstorming phase of their writing process, and then when writing their arguments in the final stage of their writing process for their persuasive essays. The analysis is framed by the following questions:

What were the argumentative strategies employed by two multilingual writers in online discussions?

What argumentative strategies did the two multilingual writers take up or modify in their persuasive essays?

What does the analysis reveal about the two multilingual writers’ rhetorical choices across different academic contexts?

1. Literature review

1.1. Online discussions for multilingual writers

Although writing in English in academic settings has increasingly become highly complex, involving participation in both digitally mediated and more conventional literacy practices (Hyland, Citation2016), formal educational settings seem to still have difficulties incorporating alternative ways of engaging with text, media, and self as an integral part of their pedagogical practices (Gee, Citation2004; Goodson, Lankshear, Mangan, & Knobel, Citation2002; Jenkins, Citation2009; Lotherington & Jenson, Citation2011). Especially in second language learning and writing, it is curious to notice that multilingual teenager and adult writers frequently report using and boosting their English to participate in various forms of digitally mediated collaborative discussions outside of school through Fan Fiction, eTandem, YouTube, and other affinity-based communities (Black, Citation2005; Hanh & Kellogg, Citation2005; Hughes, Morrison, & Thompson, Citation2016; Lam, Citation2000; Yang & Yi, Citation2017). However, few leading research studies have started to explore the impact of student participation in collaborative online discussions within the context of second language writing in academic contexts. This is particularly true regarding the discursive choices and strategies multilingual writers use when engaging in these discussions for academic purposes.

Scholars in language teaching agree that participation in online discussions can potentially foster collaboration (Chun, Citation1994; Warschauer, Citation1997), encourage critical thinking and self-expression, supporting academic literacy development (Black, Citation2005), improve linguistic complexity in writing (Jose & Abidin, Citation2016), increase vocabulary learning (Polat, Mancilla, & Mahalingappa, Citation2013), and stimulate the voicing of students’ perspectives and opinions (Kramsch, Citation2009). In particular, asynchronous online discussions can provide “favorable conditions for collaborative dialogue and collective scaffolding with minimal teacher intervention” (Cheng, Citation2010, p. 92), which can aid multilingual writers to become more independent and autonomous when engaging in academic literacy in the specific content areas they are studying.

Outside of the context of second language writing, research has shown that students seem to transfer argumentative skills acquired through collaborative online environments to their academic writing practices (Nussbaum, Citation2012). The written nature of asynchronous online discussions might afford students more time to formulate more thoughtful responses that consider different points of view (Marttunen & Laurinen, Citation2011). Asynchronous online discussion also affords the unique opportunity for students to have collaborative discussions with many participants, whose ideas and thoughts are available and visible for all to see and tap into (Harasim, Citation2012). These findings can be particularly useful in the context of argumentation for multilingual writers, where having more time and access to diverse perspectives may play a significant role in the development of valid grounds in support of one’s opinion.

1.2. Multilingual writers’ strategies

By engaging in talking, discussing, and writing, multilingual writers actively participate in a complex “patchwork of codes” (Buell, Citation2004, p. 97) connected to diverse arenas of the social life. In this process, language is always negotiated, recreated, and transformed, that is, localized or “relocalized” in practice (Pennycook, Citation2010). Multilingual writers are constantly (re)localizing discursive choices according to the flows of time and space, depending on the demands of the local communicative situations, codes, and media they are engaged in. In doing so, multilingual writers develop the ability to mix and transition to and from academic and non-academic codes as well as the ability to accommodate the English language to discourses that resemble local traditions.

These are resources also frequently and often strategically employed by multilingual writers in academic settings (Canagarajah, Citation2006, Citation2011; García, Sylvan, & Witt, Citation2011; Lu & Horner, Citation2013). Some call this process code-meshing (Canagarajah, Citation2011; Reaser, Adger, Wolfram, & Christian, Citation2017); others call it translanguaging (García, Johnson, & Seltzer, Citation2017). Both terms are utilized to describe ways multilingual writers leverage their diverse linguistic repertoires and assets when speaking and writing (Shin, Citation2018). When multilingual writers engage in translanguaging or code-meshing, they creatively use and tap into their different languages, codes, registers, and dialects in different situations and for different purposes from their own perspective, not from the perspective of a national or standard language (García, Johnson, & Seltzer, 2017).

Multilingual writers do not simply reproduce or imitate the language of native speakers and language teachers like robots, as Canagarajah (Citation2007) proposes: “Multilingual speakers are not moving toward someone else’s target; they are constructing their own norms” (p. 927). Multilingual writers invent and reinvent ways of saying and acting in the world whenever using their languages (Kramsch, Citation2009). The point of language learning is not to sound like a “native speaker,” but to successfully participate and accomplish something discursively with others in society (Cook, Citation2016).

Thus, it is important to investigate how multilingual writers successfully tackle the language demands of these discursive tasks, inquiring into the strategies they employ on their own right, independent of an idealized native speaker model (Firth & Wagner, Citation1997). One of these discursive tasks is argumentation, which is often required in academic contexts (Zwiers, O’Hara, & Pritchard, Citation2014). To become proficient in argumentation, multilingual writers need time and multiple opportunities to experiment with the specific language functions and forms associated with this important rhetorical skill (Gottlieb & Castro, Citation2017). This study is an attempt to capture these moments where two multilingual writers crafted their own strategies to accomplish the task of arguing in two different academic contexts for different academic purposes.

2. Methodology

2.1. Setting and participants

This study was conducted in one US Community College High-Intermediate English as a Second Language (ESL) Writing course, which belongs to a series of ESL writing classes designed to prepare multilingual writers for the more demanding academic tasks of regular college composition courses. The class was composed of 23 students of diverse linguistic, cultural, and socio-economic backgrounds, which included international students on an F-1 visa, immigrant adult students, and US high-school graduate students. Nine out of the 23 students were from Chinese-speaking backgrounds, making up for the majority of the class. As the instructor for the course, I became increasingly conscious and curious about the role digital media played in the English learning practices my students engaged in on a daily basis, especially my Chinese-speaking students as they seemed very eager and comfortable with using technology.

To provide a more nuanced and in-depth understanding of the trajectories taken by students in our course, two focus students were selected based on their similar cultural and linguistic backgrounds and performance in the course: Ian and Nate. Pseudonyms were used to protect their identities. Ian and Nate were both multilingual, middle-class, and international students on F-1 visas. Ian and Nate spoke English, Chinese Mandarin, and other Chinese-based dialects. Both Ian and Nate were very active in the online discussions, often participating in back and forth dialogues with each other and their peers. At the end of the course, Ian and Nate reported that the online discussions on Moodle, our course management system, had been helpful to them in the process of writing an essay. Nate wrote: “For me, my favorite activity is that we always talk to each other on the moodle. And this helped me get a lot of information about my essay. Then I can get a clear goal in my essay.” Ian showed similar views, “writing the outline and discuss with other students. It gave me more ideas about the essay.” Because of their high interest and motivation for engaging in online discussions, these two students seemed the natural choice for a rich dual case study.

2.2. Pedagogical approach

The course design was framed by online collaborative learning theory (Harasim, Citation2018), which emphasizes the role of collaborative discourse in students’ ability to develop a shared position through agreeing or disagreeing with other peers’ ideas posted online. To achieve this goal, students have to engage in three progressive stages of group discourse: (1) Idea Generating, where students brainstorm and share ideas and positions on a particular topic or problem and many perspectives emerge; (2) Idea Organizing, where students confront the new or different ideas generated by their peers and start to select the strongest or refute weaker positions through argumentation; and (3) Intellectual Convergence, where students can come to a consensus or solidify their opinion through a shared position.

As we were afforded the opportunity to use a course management system to house resources and activities, I decided to experiment with the collaborative nature of online discussions as a scaffold (Wood, Bruner, & Ross, Citation1976) for writing the four five-paragraph essay assignments required in the official guidelines for passing the course. I selected the persuasive essay for this study as it focused on argumentation, a valued rhetorical skill in academic contexts. I designed specific prompts that would support students in the process of writing the final essay, using online discussions as a creative initial space where my multilingual writers would have the opportunity to express their opinions in collaboration with other peers without worrying about grammatical accuracy or following a specific structure.

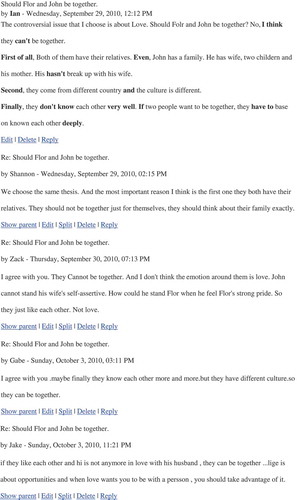

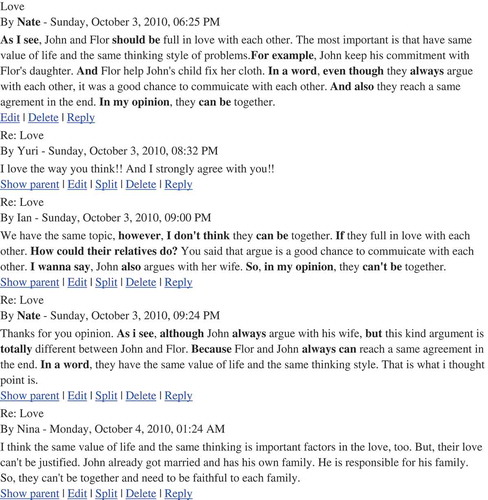

Drawing on these principles, asynchronous, written online discussions were introduced as part of the idea generating stage in the form of brainstorming for writing a persuasive essay about a controversial issue in the movie Spanglish. The movie features a Mexican immigrant, Flor, who works as a maid in an “Anglo” house and falls in love with her boss, John. The students and I generated a list of five controversial topics that stemmed from viewing the movie together. Issues about culture shock, language learning, and love were orally discussed in class and then selected for debate in the online discussions, whose task required that students pick one of the topics, formulate a thesis statement, and support their opinion with three reasons. One of the most popular topics picked by students for the online discussion was the romantic relationship between the main characters, Flor and John: Should Flor and John be together? The discussion generated much back and forth with students sharing different opinions for or against the relationship.

Following the online discussion, students engaged in a series of supportive tasks that would help them reframe the thesis statement and three reasons they shared in the online discussions in the context of a five-paragraph persuasive essay. Supportive tasks involved modeling, peer assessment, editing with support, instructor-written feedback, and conferences with instructor. In this process, students used that first thesis statement and supporting reasons posted in the online discussion as a springboard, borrowing, modifying, and changing their thesis and reasons based both on the feedback they received in the online discussion and the other many supportive activities they participated in the course. The final version of the persuasive essay was turned in digitally via Word document.

2.3. Online discussion participation

The specific discussion threads generated by Ian’s and Nate’s opposing views on the controversial issue “Should Flor and John be together?” produced a high amount of replies, triggering a highly collaborative online discussion. As it is demonstrated in Figures and (below), both Ian and Nate chose to talk about the controversial issue “Should Flor and John be together?” in their original online forum posts; however, Ian and Nate had opposing views on the matter. Ian expressed the opinion that the two main characters should not be together while Nate believed that they should be together. Ian’s and Nate’s original online posts generated, in turn, four replies each. These replies can be divided into agreeing or disagreeing with the original opinions that were stated by Ian or Nate. Figure shows that three people agreed with Ian (Shannon, Zack, and Gabe) and one disagreed (Jake). Figure shows that two people agreed with Nate (Yuri and Nate) and two did not (Ian and Nina). One of the replies in favor of Nate’s opinion was made by Nate himself in order to address Ian’s contrary reply.

In addition, among other online forum discussions in the class (not initiated or engaged by Ian or Nate), two other students chose to talk about the same controversial issue. Both of their original posts expressed the opinion that Flor and John should not be together, in line with Ian’s opinion. These other two original posts generated six other comments, amongst which five were against Flor and John being together and one was undecided, not overtly expressing an opinion that the main characters should or not be together. Overall, there were one original post and three comments for the opinion that “yes, Flor and John should be together,” three original posts and 10 comments for the opinion that “no, Flor and John should not be together,” and one comment for “undecided.”

It is important to note that out of the four original posts and 14 replies in the forum, the opinion that Flor and John should not be together was overwhelmingly more frequent, and therefore more available, than the opposite opinion that Flor and John should be together. Most of the students in the class under study that chose to engage in conversations about this controversial issue in the forum decided for “no” as their opinion. All these opinions in the forum make up for resources that were available for Ian and Nate to draw from when writing their online discussion comments and persuasive essays later. In particular, Ian’s and Nate’s argumentative strategies revealed by their choice of discursive markers should be understood in light of their peers’ ideas and opinions made available in the discussions displayed in Figures and .

2.4. Methodological approach

The data consist of two Chinese-speaking multilingual writers’ online discussion posts and comments, replies from peers, and final versions of persuasive essays. A case study approach was utilized to select texts produced by two multilingual writers out of 23 students in the class. Consent forms were distributed to all class participants at the onset of the study. Using a two-case study allows for comparability, providing empirical evidence on how two different people make decisions, use language, and participate in different literacy practices (Yin, Citation2003). Particularly in the case of the two multilingual writers’ selection, I was interested in finding out more about the writing practices of a growing number of Chinese-speaking international students on an F-1 visa status in our college campus. Asian countries send over 60% of the overall international student visa population in college or universities across the US (Ferris & Hedgcock, Citation2014).

Online discussion and persuasive essay were considered interrelated literacy practices connected by the social event of writing a persuasive essay in the ESL writing class under study (Bloome, Carter, Christian, Otto, & Shuart-Faris, Citation2004). Investigation of the strategies the two multilingual writers employed in online discussions and persuasive essays was carried out with particular attention to viewing students as multilingual writers on their own right, producing and enacting discourse in making systemic choices according to their contexts of language use (Canagarajah, Citation2009; Halliday & Matthiessen, Citation2004). A functional approach to language was used to analyze the argumentative strategies employed by the two multilingual writers, particularly the discursive choices they made in online discussions and in essay writing.

The analysis focused on the two multilingual writers’ use of certain discursive markers of argumentation, which, from a functional standpoint, can make visible argumentative strategies employed by writers in their texts (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, Citation1999; Charaudeau & Maingueneau, Citation2004; Ducrot, Citation1984; Halliday & Hasan, Citation1976; Halliday & Matthiessen, Citation2004; Koch, Citation2004). These discursive markers can be realized in a writers’ discourse in the form of concessive conjunctions, reported speech, modals, etc. This analysis happened in three steps. First, the two multilingual writers’ online discussion posts and comments were screened for the use of discursive markers of argumentation. Second, similar screening was done for the two multilingual writers’ persuasive essays. Third, argumentative strategies employed in online discussions and persuasive essays were compared and contrasted to find out whether there were similarities or differences between strategies employed in one context versus the other. The following discursive markers of argumentation displayed in Table emerged from one or both of the two students’ own writing strategies of argumentation in online discussions and persuasive essays:

Table 1. The two multilingual writers’ strategies in online discussions and persuasive essays.

3. Findings

Ian’s and Nate’s argumentative strategies revealed by their choice of discursive markers in online discussions and persuasive essays are detailed below. Refer to Figures , , , and in the methods section for the complete versions of the two multilingual writers’ posts, comments, and essays, respectively.

3.1. Argumentative strategies in online discussions

3.1.1. Expressions of modality

Ian’s opinion and supporting arguments include two high-value expressions of modality “I think” and “can’t.” “I think” is an epistemic expression of modality that makes explicit the source of conviction when attaching it to “I” (Halliday & Matthiessen, Citation2004). Ian also used another high-value expression of modality “can’t” for “they can’t be together.” His choice of high-value expressions of modality, instead of low or median, reveals an argumentative strategy of strong commitment to his opinion and demonstrates a high commitment to the truth value of the opinion. The same is true for “I wanna say” in his comment to Nate’s post. Nate, in turn, also employs high-value expressions of modality in his original post and comment. Nate makes visible the source of conviction and links it to himself, “I,” in using “As I see” and “In my opinion,” in his original online post and comments. This argumentative strategy indicates a high commitment to the truth value of his opinion, in both instances.

3.1.2. Polarity

When choosing to position himself negatively regarding the controversial issue involving the main characters, Ian’s discourse is marked by the use of negative forms, such as in “they can’t be together,” “they don’t know each other,” “His hasn’t break up with his wife,” and “I don’t think they can be together” in his comment. Ian’s argumentative strategy is to position his opinions negatively. Nate, in contrast, does not utilize negative forms in his original post or comment. Thus, Nate positions his arguments positively in relation to the topic being discussed.

3.1.3. Questioning

When commenting on Nate’s post, Ian asks the question “how could their relatives do?” as a way to challenge his peers’ divergent opinion or point view, especially regarding family values. A question that contains expressions of modality, such as “could” in Ian’s question, indicates a request for another person’s opinion (Halliday & Matthiessen, Citation2004). Ian’s use of questions can be an argumentative strategy to engage the reader so as to first ask for and acknowledge that there might be other opinions about the issue to next negate these opposing opinions. Nate does not employ this argumentative strategy.

3.1.4. Conjunctions

Ian employs the conjunction “and” orienting two reasons in the same direction, supporting his opinion that the main characters can’t be together because their cultures and countries are different. “If” introduces a condition for two people to be together, that is, they have to know each other, which restates Ian’s position that the main characters do not know each other, and cannot be together. The use of conjunctions makes visible explicit argumentative strategies of addition and condition. In his comment, Ian introduces the conjunction “so” after challenging Nate’s opinion that having arguments is not a strong reason for the main characters to be apart. In employing “so,” Ian uses the argumentative strategy of marking causes with results (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, Citation1999).

Nate employs many conjunctions in his post and comment. His argumentative strategy seems to be the one of concession in introducing subordinate clauses with “although” and “even though” and contrast in using “but.” The use of concessive conjunctions reveals the writer’s argumentative strategy to give importance and legitimacy to one or more other opinions to soften the impact of the writer’s arguments (Ducrot, Citation1984; Koch, Citation2004). The use of concessive conjunctions can also serve as an argumentative strategy to introduce another person’s opinion or argument to then deny it, showing that the writer’s argument is the strongest. In this original post, Nate considers the seemingly opposite idea that two people who argue can’t be together. He addresses this point by writing “even though they always argue with each other…” and then includes his opinion that this can be a “good chance to communicate with each other.” In his comment, he utilizes “although” and “but’ to directly address Ian’s comment and challenge to his opinion that John also argues with his wife in addition to arguing with Flor. Nate also uses “and” as an argumentative strategy to add one more example to how Flor and John share the same value of life in his post, and “because” as an argumentative strategy to introduce a reason for supporting his opinion that Flor and John’s arguments are different than the ones John has with his wife.

3.1.5. Adverbials

Ian marks his arguments by first grading them in order by using the sentence adverbials “first of all,” “second,” and “finally.” These discursive markers structure the arguments logically, which can be considered a strategy to orient the reader towards the order in which these arguments occur. Ian’s use of adverbials such as “very well,” “deeply,” and “even” can be considered an argumentative strategy to emphasize the intensity and manner of his stated opinions about the main characters’ lack of knowledge of each other. In his comment to Nate’s post, Ian employs “however” to mark the contrast between his opinion and Nate’s, using the argumentative strategy to refute his peer’s opinion.

The abundant use of “always” in Nate’s post and comment signals different argumentative strategies. In his original post, Nate employs “always” as part of his concession or acknowledge of a different opinion of “even though they always argue with each other, …”. In his comment to Ian’s challenge, Nate utilizes “always” twice, one to first concede to Ian’s challenge that John always argues with his wife to then refute this idea emphatically by introducing “totally” in the sentence “but this kind of argument is totally different between John and Flor.” The use of “In a word” at the end of his comment reveals the argumentative strategy to emphasize and summarize his opinions that having the same value of life and same thinking is the most important point that he is trying to convey (“That is what i thought the point is”).

Tables and , and below summarize the use of discursive markers used by Ian and Nate in their discourse in online discussions.

Table 2. Ian’s use of discourse markers in his post.

Table 3. Nate’s use of discursive markers in his post and comment.

Table 4. Ian’s use of discursive markers in his comment.

3.2. Argumentative strategies in persuasive essays

3.2.1. Expressions of modality

Ian’s first opinion statement in his original post in the online discussion contained two high-value expressions of modality “I think” and “can’t,” showing a high commitment to the truth value of his opinion. In his persuasive essay, Ian continues to use high-value expressions of modality; however, he includes an additional statement that recognizes other opinions about the issue: “Someone says they can be together,” which helps attenuate his commitment to the truth value of his opinion. While Ian’s body paragraphs contain many instances of more assertive statements without expressions of modality (Halliday & Matthiessen, Citation2004), his use of expressions of modality is also significant and may point to a more open stance regarding acknowledging other peers’ opinions. For example, Ian’s use of expressions of modality increases dramatically in his third body paragraph, which talks about the importance of people to know each other deeply to be together. He hedges his discourse by using a low-value expression of modality “maybe” and a median-value expression of modality “would” in “Let’s imagine, two people who don’t know each other deeply to be together, what would happen? Maybe they would argue about some small things or a misunderstanding.” This strategy shows less commitment to the truth value of his opinions. In his concluding paragraph, Ian hedges his statements even more by using the low-value expression of modality “could” accompany by the high-value expression of modality “In my opinion” to argue that “In my opinion, they couldn’t be together or couldn’t be together in a short time.” The change in tense from “can” to “could” can be considered a mark of politeness, positioning Ian’s opinions as less assertive and direct (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, Citation1999). This can signal more openness, and even respect, towards other people’s perspectives that John and Flor could be together in the future. All statements in Ian’s conclusion are modalized. This also demonstrates that Ian’s concluding remarks show openness to other people’s ideas.

Nate’s use of “should” in place of “can” as an argumentative strategy to assert his opinion statement in his persuasive essay is a significant change from his post. “Should” is a median-value expression of modality while “can” is a low-value expression of modality. In utilizing “should,” Nate employs the argumentative strategy of making a higher commitment to the truth value of his opinion. Nate’s supporting arguments differ from his original online post. In his persuasive essay, Nate adds a new argument that “love always needs to give unconditionally and to make an effort.” At the same time, Nate maintains his original online argument that arguing gives John and Flor a good chance to communicate and get to know each other in the first body paragraph of his persuasive essay, even after this argument was challenged by Ian. Nate’s first body paragraph is marked by more direct and assertive statements, presenting only one instance of an expression of modality, differently from his original post. Statements without expressions of modality indicate an argumentative strategy of a stronger commitment to the truth value of the writer’s opinion. Nate’s second and third body paragraphs concentrate a greater amount of expressions of modality – eight total. Similar to the argumentative strategy used in his opinion statement, Nate’s second and third body paragraphs also challenge the counterargument regarding different cultural backgrounds. For example, in Nate’s second body paragraph, he hedges his argument “that love always needs to give unconditionally and to make an effort” by using the low-value expression of modality “can.” Nate concludes his second body paragraph by using a combination of a high-value expression of modality “As I see” and a low-value expression of modality “can” in “As I see, both of them have tried their best to adjust their ties by different things they can do for each other.” Nate’s use of “As I see” positions his opinion as surer, confident, and forward. In his third body paragraph, Nate maintains one of the opinions he stated in his original post, now hedging his statements by using the median-value expression of modality “should” in “In the last place, the most important reason is that they should have the same value of life and almost same thinking style of problems.” In Nate’s concluding paragraph, he first chooses to use the low-value expression of modality “can” in “In conclusion, for all of these reasons we can know people who are entirely different also can be together” and in “we can overcome all of obstacles on our way be together, “ seemingly less committed to the truth value of his opinion. However, Nate ends his concluding paragraph with a direct or blunt statement without any expressions of modality, “That is true love,” showing a high commitment to the truth value of his opinion and positioning his convictions as more certain and less open to change. Nate still commits himself highly to his opinion, which was overwhelmingly different from most of his peers in the online discussion.

3.2.2. Polarity

Ian continues to position his arguments negatively or contrary to the idea that the main characters should be together by utilizing negative expressions of modality, such as “can’t.” Nate does not utilize this argumentative strategy in his essay.

3.2.3. Questioning

Instead of using affirmative or negative declarative sentences, Ian chooses to phrase many of his arguments in the form of questions in his essay. For example, when Ian writes about his opinion that Flor and John cannot be together because they come from different countries and cultures in his second body paragraph, he asks “When they face the same thing at the same time, what would happen?” and “How could they be together?” The same happens when Ian writes about his opinion that Flor and John cannot be together because they do not know each other for a long time. In his third body paragraph, Ian asks: “Let’s imagine, two people who don’t know each other deeply to be together, what would happen?” In almost all of these instances, Ian answers his own questions, asserting his position about the issue. In this case, Ian’s questions consist of the well-known argumentative strategy of using rhetorical questions (Koch, Citation2004), which can also serve the purpose of making his/her arguments stronger by engaging the readers in contemplating diverse opinions about the matter. Nate employs solely one question as an argumentative strategy to introduce his essay by requesting the reader’s opinion in his first paragraph.

3.2.4. Conjunctions

Ian hedges his opinion that the characters in the movie “can’t be together” in his opinion statement by using the coordinate conjunction “or” in “or they can’t be together for a short time.” In his original post, Ian was more assertive, using a more direct and aggressive tone by starting his statement with “No,” and following by using two high-value expressions of modality “I think” and “can’t.” There is a marked increase in Ian’s use of conjunctions as an argumentative strategy from his post to his persuasive essay, where he employed (see Table ). These conjunctions are mainly employed to introduce examples to support his reasons for John and Flor not to be together. The use of “although” in the first paragraph marks a concession to the idea that John and his children also argue with his wife, and the use of “so” in the third body paragraph is used as an argumentative strategy to establish a cause–effect relationship between two logical arguments that support the idea that the two main characters do not know each other deeply. In his concluding paragraph, Ian includes a new argument by introducing two clauses with the subordinate conjunctions “when” and “if” in: “They can be together, when they know each other very well and if John breaks up with Deborah.” Through this final statement, Ian employs the argumentative strategy of condition and time, conceding to the possibility for John and Flor to be together, an opinion that is contrary to his. The use of the low-value “can” does not mark a stronger commitment to the truth value of this final statement.

Table 5. Ian’s use of discursive markers in his persuasive essay.

One of the most significant changes in Nate’s argumentative strategy between his opinion stated in the online post and his opinion statement in his essay is the insertion of the subordinate conjunction “although” in the clause “although they come from different countries.” In his second body paragraph, Nate employs the same argumentative strategy he used in his opinion statement in addressing other people’s perspectives by using the concessive conjunction “although” in “Although they misunderstood each other at the beginning, they also could fix their problem through argument which I think that is a kind of communication.” Through the strategy of concession, Nate positions himself as a writer who is careful to introduce counterpoints to recognize the existence of different points of view to then refute them, strengthening his own arguments and opinions (Ducrot, Citation1984).

3.2.5. Adverbials

Ian maintained the same three core ideas he had had in his original post in his persuasive essay. Even the order of the arguments is the same between the essay and the post. This is demonstrated by the use of adverbials of order “first” and “second” to introduce his reasons. However, there is a change in argumentative strategy to emphasize the last reason from employing “finally” in his online post to utilizing the adverbial phrase as well as the adverbial “also” in “the last and also the most important reason” in his third body paragraph. This strategy emphasizes the hierarchy of the arguments placing the final one as the most salient. In his first body paragraph, Ian uses “maybe” to answer to one of his rhetorical questions about what would happen if the main characters got together, showing a strategy that concedes to the possibility that the main characters may or may not argue. Ian employs “sometimes” as a strategy to differentiate the kinds of arguments the main character has with his wife. In his second body paragraph, Ian utilizes “however” as an argumentative strategy to juxtapose Flor’s and Deborah’s cultural values. In his third body paragraph, Ian continues to use “deeply” as an argumentative strategy to emphasize that to be together a couple needs to know each other.

There is a marked increase between the use of adverbials in Nate’s online posts and in his essay (see Table ), which points to an argumentative strategy to lead the reader to infer or interpret connections between two clauses or ideas related to each other (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, Citation1999). Moreover, these sentence adverbials can function as logical connectors that strengthen and specify the relationship between sentences, contributing to the cohesiveness of a text (Halliday & Hasan, Citation1976). Many of these adverbials are used by Nate as an argumentative strategy to reinforce his opinions or to introduce a counter-argument or opposing view. For example, Nate’s use of the adverbial “still” accompanied by the high-value and subjective “I believe” in “And I still believe that the whole world is becoming more and more international, we can overcome all of the obstacles on our way be together” in his conclusion signals that in spite of contrary opinions that Flor and John could not be together due to their different backgrounds, Nate still maintains his opinion that they can.

Table 6. Nate’s use of discursive markers in his persuasive essay.

3.2.6. Reported speech & quotations

Ian did not utilize this argumentative strategy in his essay. Nate, in turn, employs the strategy of reported speech in his third body paragraph by citing a popular Chinese proverb in “As a Chinese proverb goes, ‘birds of a feather flock together.’ It means people divide a lot of kinds, only who has the approach concept can live close.” When Nate cites the proverb, he is not only alluding to popular wisdom and words of others, but he is also affirming his position by evoking authority in his discourse. This argumentative strategy makes visible that there are other voices and perspectives that agree and support Nate’s opinion that the “same value of thinking” is a very important reason for a couple to be together, differently from most of the other opinions made available in the online discussion.

4. Discussion

Findings reveal that the two multilingual writers experimented with specific language functions and forms associated with the highly complex task of argumentation through posting, commenting, and repurposing their opinions for their persuasive essays. However, the two multilingual writers used different argumentative strategies to construct, strengthen, and position their ideas in online discussions and persuasive essays. First, the two writers chose contrasting opinions regarding the controversial issue involving the romantic relationship between the two characters, which led Ian to position himself negatively regarding the issue whereas Nate positioned himself positively. This decision drove the use of different discursive markers for different purposes. Second, as the two writers relocalized their arguments from online discussions to a persuasive essay, Ian’s argumentative strategies revealed a more open stance whereas Nate’s strategies became more assertive. Third, the two writers directly drew from their opinion statements and reasons they first started developing in online discussions to write their essays; however, Ian utilized the same exact reasons and order of arguments while Nate changed the order of his arguments and added a new reason.

The difference in argumentative strategies employed by the two writers demonstrates their ability to creatively use and tap into their diverse linguistic repertoires to accomplish demanding academic tasks for different purposes from their own perspective (Canagarajah, Citation2011; García, Johnson, & Seltzer, 2017). Ian and Nate were both able to successfully tackle the language demands of online discussions and persuasive essays through experimenting with a diverse array of discursive markers in the form of expressions of modality, negation, questioning, conjunctions, adverbials or reported speech. When engaging in online discussions, both were able to state their opinions twice in the form of original post and comments to each other’s posts, participating in a back and forth dialogue that provided the opportunity to make discursive choices to first position their arguments and then confront other peers’ opinions. In doing so, the two multilingual writers’ displayed complex linguistic choices and vocabulary (Jose & Abidin, Citation2016; Polat et al., Citation2013). In their persuasive essays, both writers were able to craft refined argumentative strategies to address, acknowledge, or refute counter opinions and different perspectives. In line with current research, the two multilingual writers’ seemed to have transferred argumentative skills first practiced in online discussions to their essays, a more conventional academic wiring practice (Nussbaum, Citation2012).

5. Pedagogical implications

The findings of this study point to important pedagogical implications for the use of online discussions in academic writing. As a collaborative space, online discussions afforded the two writers not only the opportunity to put forward their arguments but also to share and see their peers’ diverse opinions (Harasim, Citation2018). Following the example of this study, instructors can implement online discussions as pre-writing tasks to provide multilingual writers with a safe arena for trying out unfamiliar language forms and discourse while exposing them to other peers’ perspectives. Online discussions can be used to record multilingual writers’ linguistic choices, composition strategies, and rhetorical moves. This written record can be used as a springboard for multilingual writers to confront and argue new or different ideas in order to select the strongest positions when writing more linguistically demanding pieces, such as essays and research reports. As demonstrated in this study, sharing and arguing with an audience of peers in written form can yield positive results for argumentation in academic writing.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Clara V. Bauler

Dr. Clara V. Bauler is an assistant professor of TESOL/Bilingual Education at Adelphi University. She has a Ph.D. in Education with emphasis in Applied Linguistics and Cultural Perspectives and Comparative Education from the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research focuses on academic language development among bilingual learners, integration of TESOL principles and practices into content area instruction, and the use of web-based collaborative tools to support multilingual learners’ writing skills.

References

- Andresen, M. A. (2009). Asynchronous discussion forums: Success factors, outcomes, assessments, and limitations. Educational Technology & Society, 12(1), 249–19.

- Black, R. W. (2005). Access and affiliation: The literacy and composition practices of English language learners in an online fanfiction community. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 49(2), 118–128. doi:10.1598/JAAL.49.2.4

- Bloome, D., Carter, S. P., Christian, B. M., Otto, S., & Shuart-Faris, N. (2004). Discourse analysis and the study of classroom language and literacy events: A microethnographic perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Buell, M. Z. (2004). Code-switching and second language writing: How multiple codes are combined in a text. In C. Bazerman & P. Prior (Eds.), What writing does and how it does it: An introduction to analyzing texts and textual practices (pp. 97–122). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Canagarajah, A. S. (2006). Negotiating the local in English as a Lingua Franca. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 26, 197–218. doi:10.1017/S0267190506000109

- Canagarajah, A. S. (2007). Lingua Franca English, multilingual communities, and language acquisition. The Modern Language Journal, 91(Focus Issue), 923–939. doi:10.1111/modl.2007.91.issue-s1

- Canagarajah, A. S. (2009). Multilingual strategies of negotiating English: From conversation to writing. JAC, 29(1/2), 17–48.

- Canagarajah, A. S. (2011). Codemeshing in academic writing: Identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. The Modern Language Journal, 95(3), 401–417. doi:10.1111/modl.2011.95.issue-3

- Celce-Murcia, M., & Larsen-Freeman, D. (1999). The grammar book: An ESL/EFL teacher’s course. 2nd edn. USA: Heinle & Heinle.

- Charaudeau, P., & Maingueneau, D. (2004). Dicionário de análise do discurso. São Paulo: Contexto.

- Cheng, R. (2010). Computer-mediated scaffolding in L2 students‘ academic literacy development. CALICO Journal, 28(1), 74–98. doi:10.11139/cj.28.1

- Chun, D. M. (1994). Using computer networking to facilitate the acquisition of interactive competence. System, 22, 17–31. doi:10.1016/0346-251X(94)90037-X

- Chun, D. M. (2011). Computer-assisted language learning. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (Vol. 2, pp. 663–680). New York: Routledge.

- Cook, V. (2016). Second language learning and language teaching. 5th edn. London: Routledge.

- Ducrot, O. (1984). Le dire et le dit. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit.

- Ferris, D. R., & Hedgcock, J. S. (2014). Teaching L2 composition: Purpose, process, and practice. London: Routledge.

- Firth, A., & Wagner, J. (1997). On discourse, communication, and (some) fundamental concepts in SLA research. The Modern Language Journal, 81(3), 285–300. doi:10.1111/modl.1997.81.issue-3

- García, O., Johnson, S. I., & Seltzer, K. (2017). The translanguaging classroom: Leveraging student bilingualism for learning. Philadelphia, PA: Caslon.

- García, O., Sylvan, C. E., & Witt, D. (2011). Pedagogies and practices in multilingual classrooms: Singularities in pluralities. The Modern Language Journal, 95(3), 385–400. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01208.x

- Gee, J. P. (2004). Situated language and learning. London: Routledge.

- Goodson, I. F., Lankshear, C., Mangan, M., & Knobel, M. (2002). Cyber spaces/social spaces: Culture clash in computerized classrooms. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gottlieb, M., & Castro, M. (2017). Language power: Key uses for accessing content. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Halliday, M. A. K., & Hasan, R. (1976). Cohesion in English. London: Longman.

- Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. (2004). An introduction to functional grammar (3rd ed.). Great Britain: Arnold.

- Hanh, T. N., & Kellogg, G. (2005). Emergent identities in on-line discussions for second language learning. Canadian Modern Language Review, 62(1), 111–136. doi:10.3138/cmlr.62.1.111

- Harasim, L. (2012). Learning theory and online technologies. NY: Routledge.

- Harasim, L. (2018, October). OCL Theory. Retrieved from https://www.lindaharasim.com/online-collaborative-learning/ocl-theory/

- Hew, K. F., Cheung, W. S., & Ng, S. C. L. (2010). Student contribution in asynchronous online discussion: A review of the research and empirical exploration. Instructional Science, 38, 571–606. doi:10.1007/s11251-008-9087-0

- Hopewell, S., & Escamilla, K. (2014). Biliteracy development in immersion contexts. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 2(2), 181–195. doi:10.1075/jicb.2.2.02hop

- Hughes, J., Morrison, L., & Thompson, S. (2016). Who do you think you are? An examination of the off/online identities of adolescents using a social networking site. In M. Walrave, K. Ponnet, E. Vanderhoven, J. Haers, & B. Segaert (Eds.), Youth 2.0: Social media and adolescence: Connecting, sharing and empowering (pp. 3–19). Springer Publishing.

- Hyland, K. (2016). Teaching and researching writing. 3rd edn. London: Routledge.

- Jenkins, H. (2009). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st century. MA: The MIT Press.

- Jose, J., & Abidin, M. J. Z. (2016). A pedagogical perspective on promoting English as a Foreign Language writing through online forum discussions. English Language Teaching, 9(2), 84–101. doi:10.5539/elt.v9n2p84

- Koch, I. V. (2004). Argumentação e linguagem. São Paulo: Cortez Editora.

- Kramsch, C. (2009). The multilingual subject. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lam, W. S. E. (2000). Second language literacy and the design of the self: A case study of a teenager writing on the Internet. TESOL Quarterly, 34(3), 457–483. doi:10.2307/3587739

- Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2017). Researching new literacies: Addressing the challenges of initial research training. In C. Lankshear & M. Knobel (Eds.), Researching new literacies: Design, theory, and data in sociocultural investigation (pp. 1–16). NY: Peter Lang.

- Leonard, R. L. (2014). Multilingual writing as rhetorical attunement. College English, 76(3), 227–247.

- Lotherington, H., & Jenson, J. (2011). Teaching multimodal and digital literacy in L2 settings: New literacies, new basics, new pedagogies. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 31, 226–246. doi:10.1017/S0267190511000110

- Lu, M., & Horner, B. (2013). Translingual literacy, language difference, and matters of agency. College English, 75(6), 582–607.

- Marttunen, L., & Laurinen, M. (2011). Learning of argumentation skills in networked and face-to-face environments. Instructional Science, 29(2), 127–153. doi:10.1023/A:1003931514884

- Moje, E. B. (2009). A call for new research on new and multi-literacies. Research in the Teaching of English, 43(4), 348–362.

- Nussbaum, E. M. (2012). Argumentation and student-centered learning. In D. Jonassen & S. Land (Eds.), Theoretical foundations of learning environments (pp. 114–141). London: Routledge.

- Pennycook, A. (2010). Language as a local practice. London: Routledge.

- Polat, N., Mancilla, R., & Mahalingappa, L. (2013). Anonymity and motivation in asynchronous discussions and L2 vocabulary learning. Language Learning & Technology, 17(2), 57–74.

- Reaser, J., Adger, C. T., Wolfram, W., & Christian, D. (2017). Dialects at school: Educating linguistically diverse students. New York: Routledge.

- Shin, S. J. (2018). Bilingualism in schools and in society: Language, identity, and policy. London: Routledge.

- Thorne, S. L., Black, R. W., & Sykes, J. M. (2009). Second language use, socialization, and learning in Internet interest communities and online gaming. The Modern Language Journal, 93(Focus Issue), 802–821. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00974.x

- Warschauer, M. (1997). Computer-mediated collaborative learning: Theory and practice. Modern Language Journal, 81, 470–481. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1997.tb05514.x

- Wood, D., Bruner, J., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17, 89–100.

- Yang, S. J., & Yi, Y. (2017). Negotiating multiple identities through eTandem learning experiences. CALICO Journal, 34(1), 97–114. doi:10.1558/cj.29586

- Yi, Y. (2014). Possibilities and challenges of multimodal literacy practices in teaching and learning English as an additional language. Language and Linguistics Compass, 8(4), 158–169. doi:10.1111/lnc3.v8.4

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Zwiers, J., O’Hara, S., & Pritchard, R. (2014). Common core standards in diverse classrooms. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.